International and Domestic Sustainable Forest Management Policies: Distributive Effects on Power among State Agencies in Bangladesh

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Study Contexts

2.1. SFM Policy: Global and Domestic Context

2.2. Sustainable Forest Management in Bangladesh

3. Conceptual Framework

3.1. Bureaucratic Politics and Actor-Centered Power

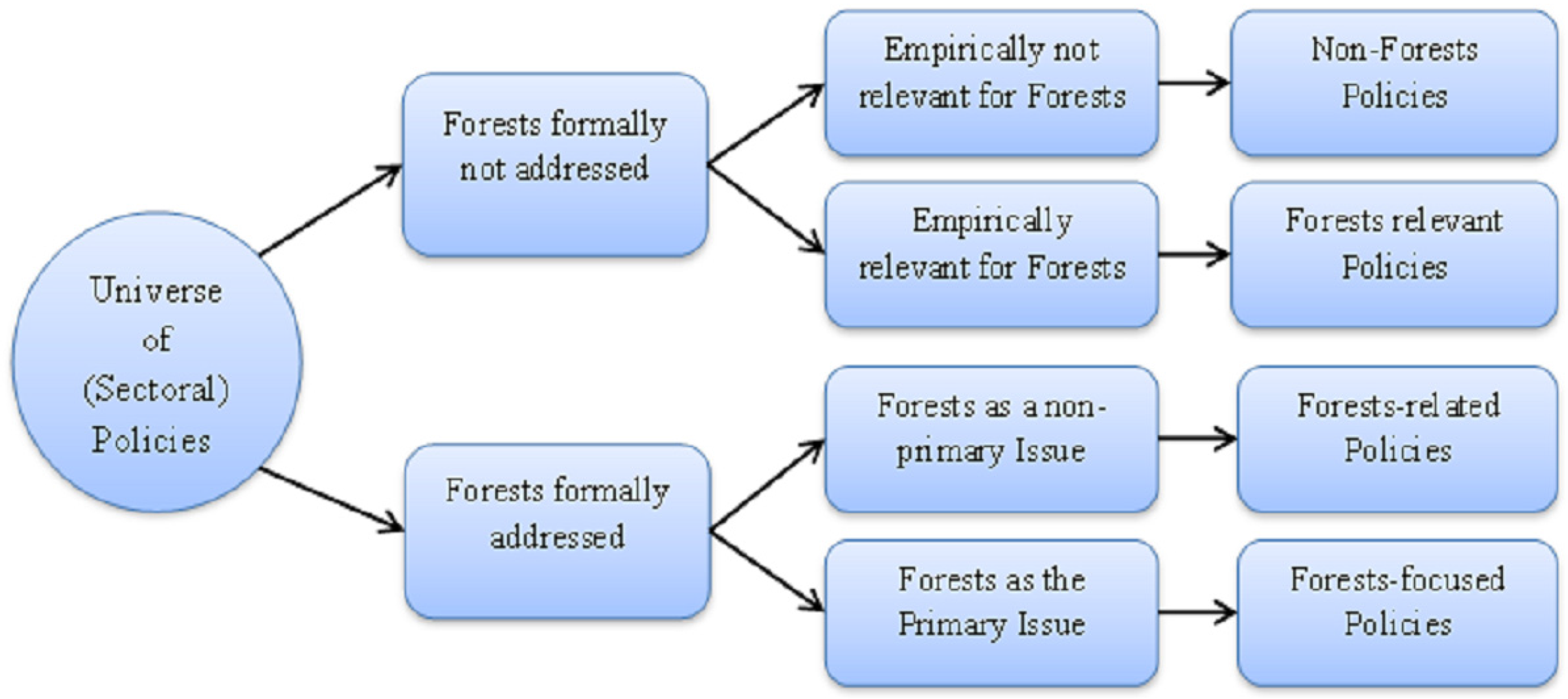

3.2. Policies and Policy Process

3.2.1. Definition of Policy and Project

3.2.2. Policy Process and Strategic Tasks

3.3. Propositions

- (1)

- Domestic bureaucracies, as well as foreign donor bureaucracies, may gain or lose power due to their assigned tasks resulting from the SFM policies.

- (2)

- Domestic policy assigns strategic tasks to these bureaucracies, which add specific power elements such as information, incentives, or coercion to a bureaucracy’s power.

- (3)

- The resulting power dynamics, as well as the different bureaucracies’ equipment with specific power elements, are important factors as these set the limits and directions in which domestic SFM policy will develop.

4. Methods

5. Results

5.1. SFM Policies and Their Strategic Tasks, 1992–2013

5.2. Distribution of Power Elements among Domestic Bureaucracies and Foreign Donors

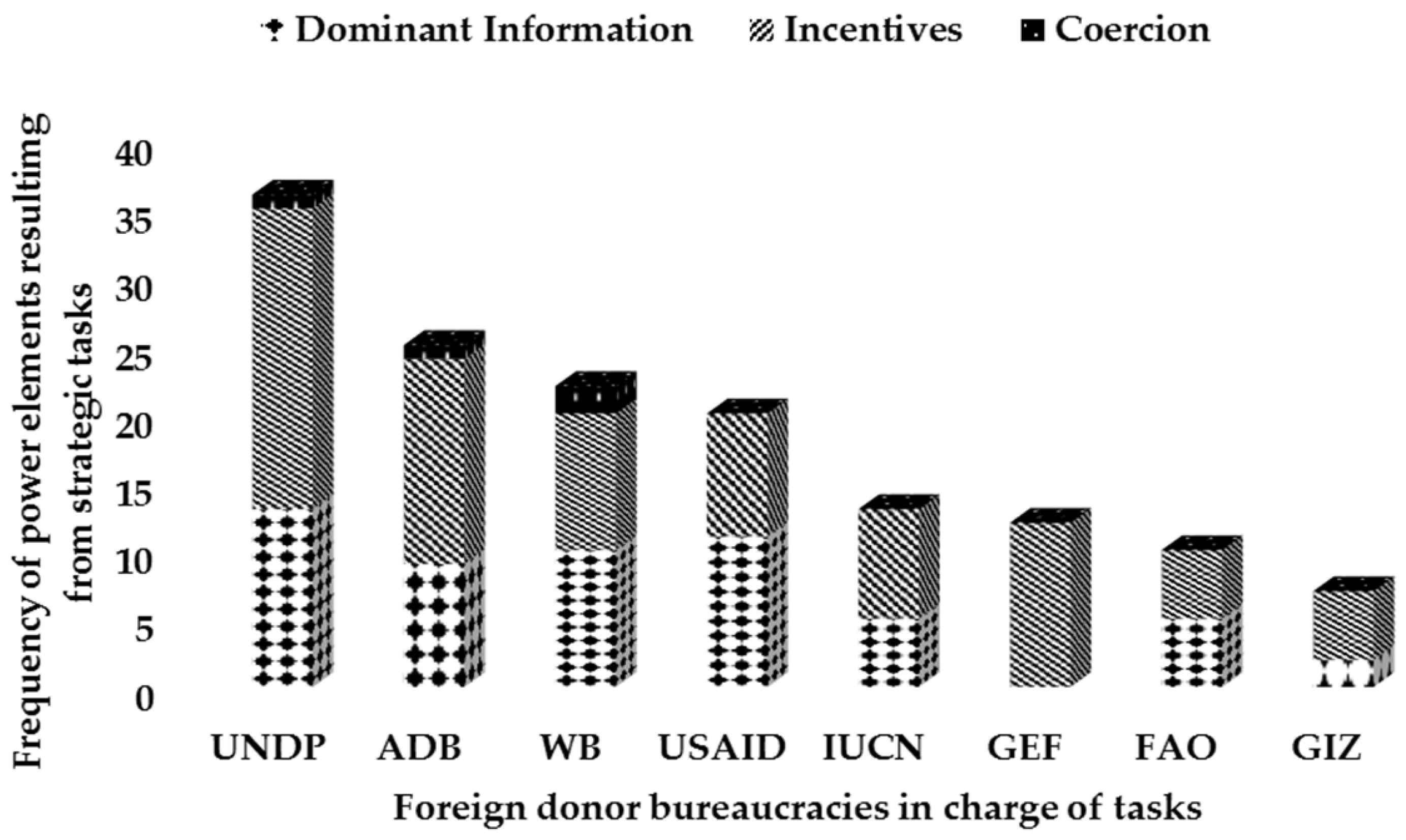

5.3. Sum of Power Elements by Domestic Bureaucracies and Foreign Donors in Charge of Tasks, 1992–2013

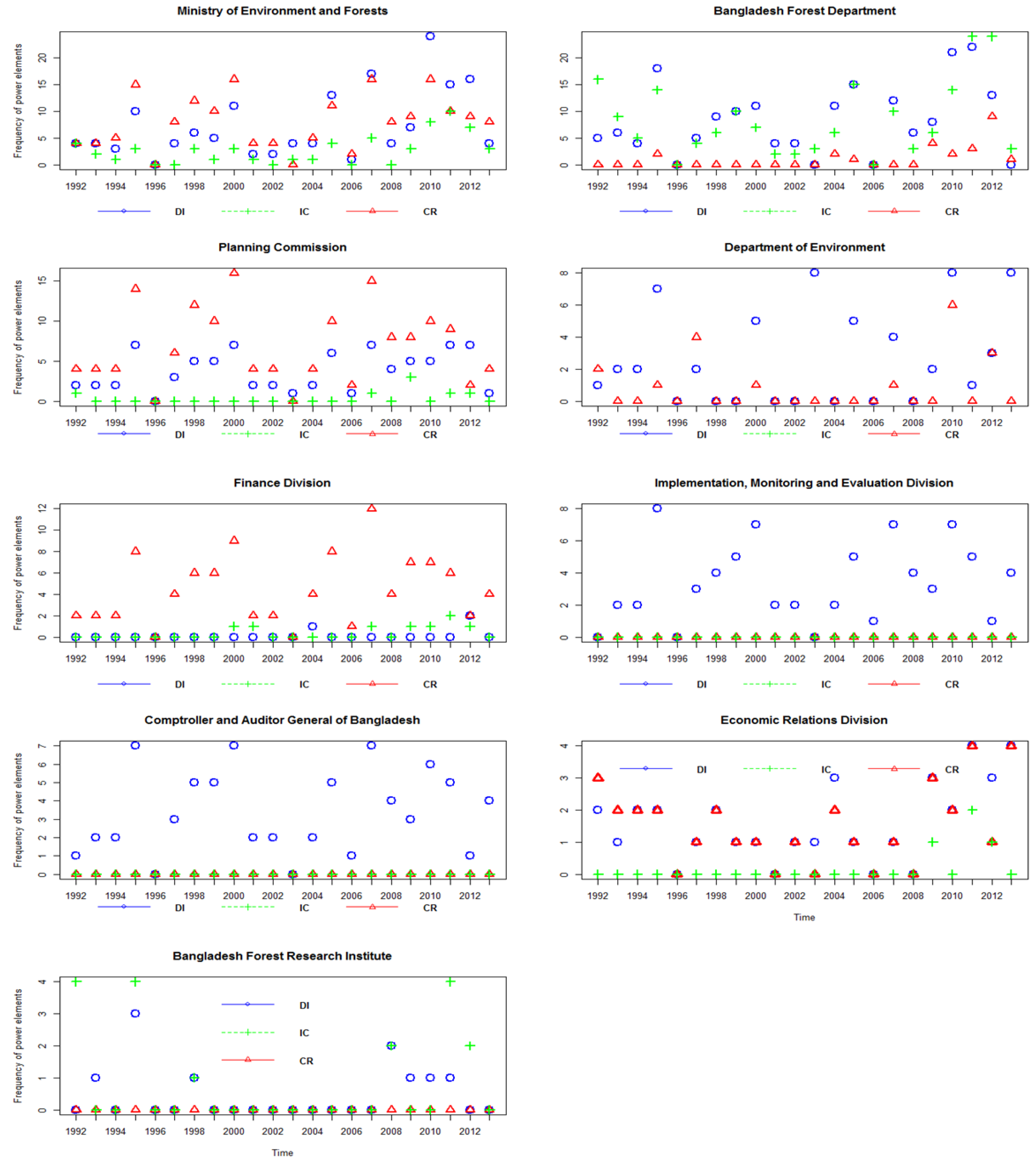

5.4. New Tasks Sorted by Power Elements over Time (1992–2013)

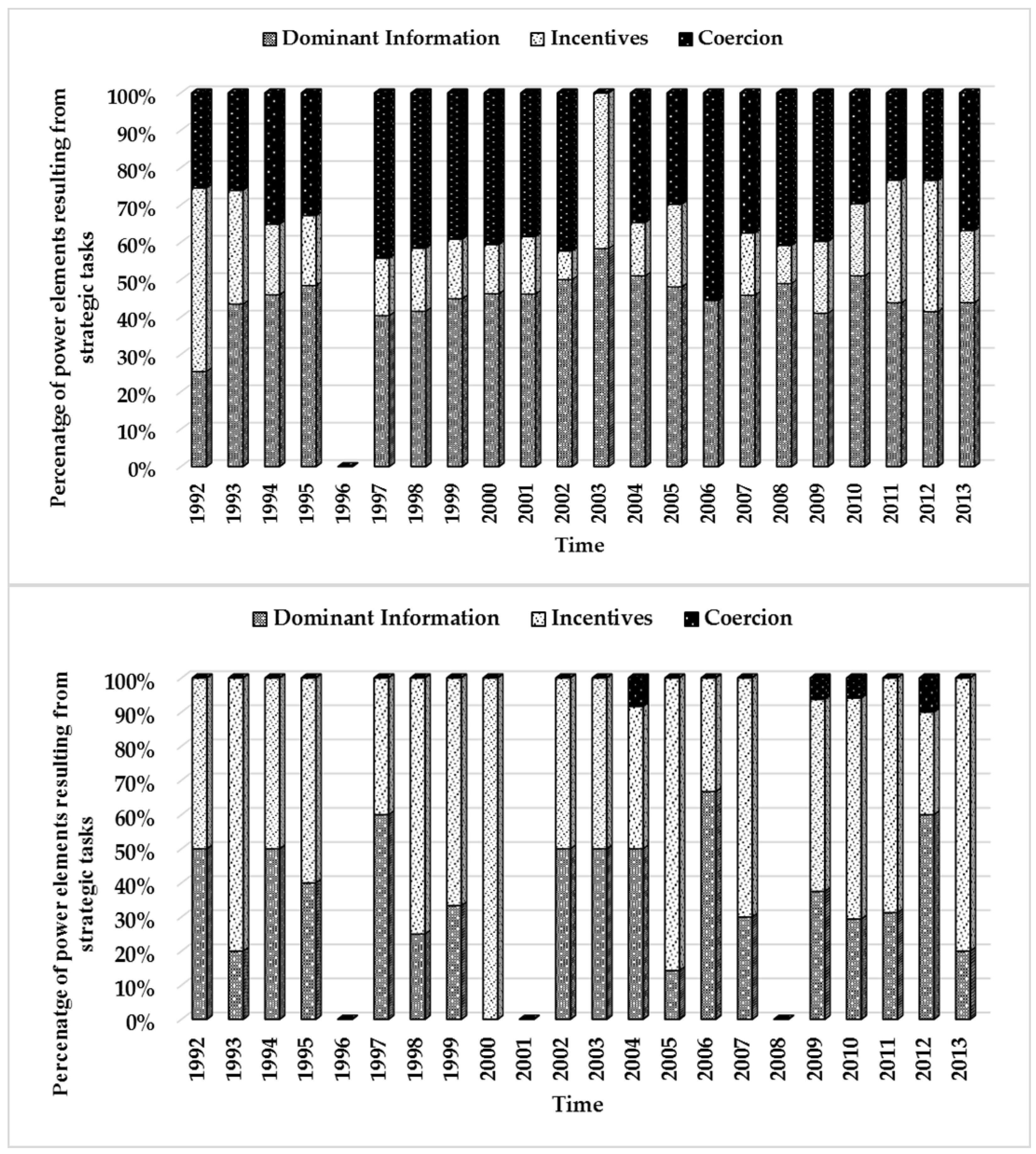

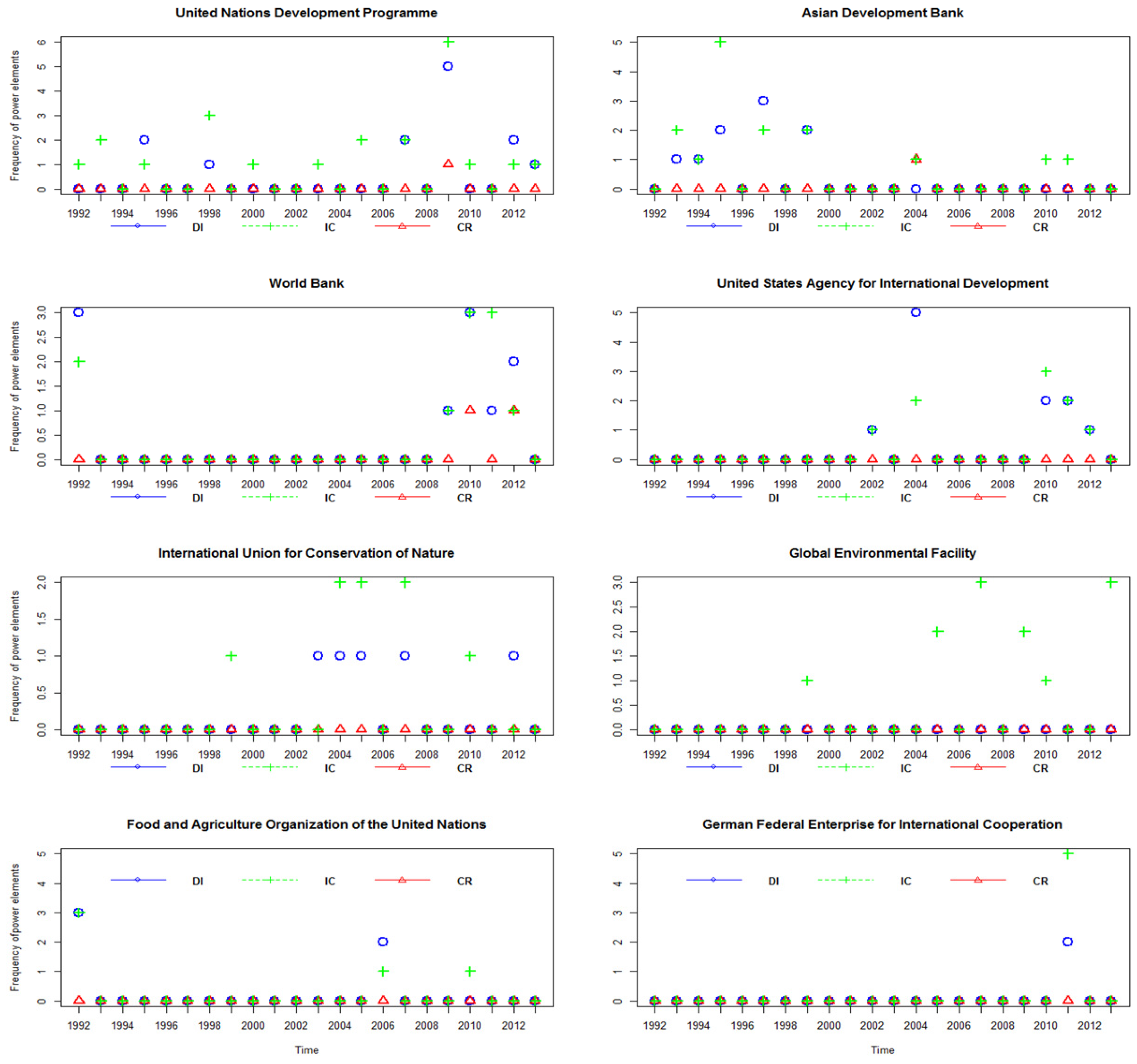

5.5. New Tasks Sorted by Power Elements and Distinguished into Competing Domestic and Foreign Donor Bureaucracies over Time: 1992–2013

6. Discussion and Conclusion

6.1. Significance of Power Elements in the Leading Bureaucracies

6.2. Power Dynamics among Domestic and Foreign Donor Bureaucracies

6.3. Power and Conflict of Interest among State Bureaucracies

6.4. Variation of Power Elements over Time, and Policy Mixes

6.5. Limits and Directions of SFM Policy by Power Distribution

6.6. Methodological Challenges and Applicability

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Policy | Start Year | Policy Cycle | Strategic Tasks | Power Elements | Bureaucracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resource Conservation through Community Reforestation and Forest Management in Chunati Wildlife Sanctuary, Chittagong | 2011 | Formulation | 1. Preparation of the project document | Dominant Information | BFD |

| 2. Approval of the project document | Coercion | MoEF, PC | |||

| 3. Approval of fund allocation | Coercion | FD, PC, MoEF, ERD | |||

| Implementation | 4. Financial and technical support for implementing this project | Incentives | GIZ | ||

| 5. Improve biodiversity conservation and management through people‘s participation | Dominant Information | BFD | |||

| 6. Habitat restoration of Asian Elephant | Incentives | BFD | |||

| 7. Provide advisory services and training for capacity building of key stakeholders | Incentives | MoEF, GIZ | |||

| Monitoring | 8. Monitoring and evaluation of project activities | Dominant Information | IMED, MoEF, BFD, GIZ, PC | ||

| 9. Audit of financial activities | Dominant Information | C & AG |

Appendix B

| Year | No. of Policies and Projects | No. of Strategic Tasks | Government Funded | Donor Funded |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 | 3 | 43 | 1 | 2 |

| 1993 | 3 | 30 | 1 | 2 |

| 1994 | 3 | 24 | 1 | 2 |

| 1995 | 8 | 69 | 5 | 3 |

| 1996 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1997 | 4 | 37 | 3 | 1 |

| 1998 | 6 | 44 | 4 | 2 |

| 1999 | 5 | 39 | 4 | 1 |

| 2000 | 9 | 67 | 8 | 1 |

| 2001 | 2 | 12 | 2 | 0 |

| 2002 | 2 | 14 | 1 | 1 |

| 2003 | 2 | 17 | 0 | 2 |

| 2004 | 3 | 41 | 0 | 3 |

| 2005 | 10 | 69 | 6 | 4 |

| 2006 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 1 |

| 2007 | 11 | 79 | 8 | 3 |

| 2008 | 4 | 25 | 4 | 0 |

| 2009 | 7 | 60 | 3 | 4 |

| 2010 | 14 | 113 | 9 | 5 |

| 2011 | 9 | 89 | 5 | 4 |

| 2012 | 8 | 88 | 5 | 3 |

| 2013 | 6 | 43 | 2 | 4 |

| Total | 121 | 1012 | 73 | 48 |

References

- Humphreys, D. Logjam: Deforestation and the Crisis of Global Governance; Earthscan: London, UK; Sterling Heights, MI, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys, D. Discourse as ideology: Neoliberalism and the limits of international forest policy. For. Policy Econ. 2009, 11, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, D. The evolving forests regime. Glob. Environ. Chang. 1999, 9, 251–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giessen, L. “Fragmentierung“ als Schlüsselfaktor des internationalen Waldregimes: Von einem mono-zu einem multi-disziplinären methodischen Rahmen für eine vertiefte Forstpolitikforschung. Allg. Forst Jagdztg. 2013, 184, 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Giessen, L. Reviewing the main characteristics of the international forest regime complex and partial explanation for its fragmentation. Int. For. Rev. 2013, 15, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jürging, J.; Giessen, L. Ein “Rechtsverbindliches Abkommen über die Wälder in Europa”: Stand und Perspektiven aus rechts-und umweltpolitikwissenschaftlicher Sicht. Nat. Recht 2013, 35, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, C.L.; Cashore, B.; Kanowski, P. Global Environmental Forest Policies: An International Comparison; Earthscan: London, UK, 2010; p. 384. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott, C.L.; Humphreys, D.; Wildburger, C.; Wood, P.; Marfo, E.; Pacheco, P.; Yasmi, Y. Mapping the core actors and issues defining international forest governance. In Embracing Complexity: Meeting the Challenges of International Forest Governance; Rayner, J., Buck, A., Katila, P., Eds.; IUFRO: Vienna, Austria, 2010; Volume 28, pp. 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Rayner, J.; Humphreys, D.; Welch, F.P.; Prabhu, R.; Verkooijen, P. Introduction. In Embracing Complexity: Meeting the Challenges of International Forest Governance; Rayner, J., Buck, A., Katila, P., Eds.; IUFRO: Vienna, Austria, 2010; Volume 28, pp. 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sahide, M.A.; Nurrochmat, D.R.; Giessen, L. The regime complex for tropical rainforest transformation: Analysing the relevance of multiple global and regional land use regimes in Indonesia. Land Use Policy 2015, 47, 408–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadath, N. Media as a Driver of Policy Change? The Example of Forest-Climate Policy in Bangladesh, 1st ed.; VVB Laufersweiler: Giessen, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Krott, M. Forest Policy Analysis; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Giessen, L.; Hubo, C.; Krott, M.; Kaufer, R. Steuerungspotentiale von Zielen und Instrumenten des Politiksektors Forstwirtschaft und deren möglicher Beitrag zu einer nachhaltigen Entwicklung ländlicher Regionen. Z. Umweltpolit. Umweltr. 2013, 36, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.S.; Bae, J.S.; Fisher, L.A.; Latifah, S.; Afifi, M.; Lee, S.M.; Kim, I.A. Indonesia’s Forest Management Units: Effective intermediaries in REDD+ implementation? For Policy Econ. 2016, 62, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, S.L.; Giessen, L. Dismantling comprehensive forest bureaucracies: Direct access, the World Bank, agricultural interests, and neoliberal administrative reform of forest policy in Argentina. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, A.; Giessen, L. Actor Positions on Primary and Secondary International Forest-related Issues Relevant in Indonesia. J. Sustain. Dev. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Sadath, M.N.; Giessen, L. Foreign donors driving policy change in recipient countries: Three decades of development aid influencing forest policy in Bangladesh. For. Policy Econ. 2016. accepted. [Google Scholar]

- Sadath, M.N.; Krott, M. Identifying policy change-analytical program analysis: An example of two decades of forest policy in Bangladesh. For. Policy Econ. 2012, 25, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization. Bangladesh Forestry Sector Outlook Study by Junaid Khan Chodhury and Abdullah Abraham Hossain; FAO: Bangkok, Thailand, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury, J.K. Sustainable forest management vis a-vis Bangladesh forestry. In Proceedings of the First Bangladesh Forestry Congress, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 19–21 April 2011; Bangladesh Forest Department, Ministry of Environment and Forests: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2011; pp. 405–415. [Google Scholar]

- Howlett, M.; Ramesh, M.; Perl, A. Studying Public Policy: Policy Cycles and Policy Subsystems, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; p. 336. [Google Scholar]

- Giessen, L.; Krott, M.; Möllmann, T. Increasing representation of states by utilitarian as compared to environmental bureaucracies in international forest and forest-environmental policy negotiations. For. Policy Econ. 2014, 38, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niskanen, W. Bureaucracy and Representative Government; Aldine Transaction: Chicago, IL, USA, 1971; p. 241. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, B.G. The Politics of Bureaucracy-An Introduction to Comparative Public Administration, 6th ed.; Routledge: Milton Park Abingdon, UK, 2010; p. 400. [Google Scholar]

- Prabowo, D.; Maryudi, A.; Imron, M.A. Enhancing the application of Krott et al.’s (2014) Actor-Centred Power (ACP): The importance of understanding the effect of changes in polity for the measurement of power dynamics over time. For. Policy Econ. 2016, 62, 184–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, A.; Giessen, L. Absolute and relative power gains among state agencies in forest-related land use politics: The Ministry of Forestry and its competitors in the REDD+ Programme and the One Map Policy in Indonesia. Land Use Policy 2015, 49, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubo, C.; Krott, M. Conflict camouflaging in public administration—A case study in nature conservation policy in Lower Saxony. For. Policy Econ. 2013, 33, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, D. Forest negotiations at the United Nations: Explaining cooperation and discord. For. Policy Econ. 2001, 3, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvoy, D.; Jones, M.; McKee, M.; Talberth, J. Incentivizing cooperative agreements for sustainable forest management: Experimental tests of alternative structures and institutional rules. For. Policy Econ. 2014, 44, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhou, M. Adapting sustainable forest management to climate policy uncertainty: A conceptual framework. For. Policy Econ. 2015, 59, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, J. Conclusions. In Embracing Complexity: Meeting the Challenges of International Forest Governance; Rayner, J., Buck, A., Katila, P., Eds.; IUFRO: Vienna, Austria, 2010; Volume 28, p. 172. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, S.; Cashore, B. Examination of the influences of global forest governance arrangements at the domestic level. In Embracing Complexity: Meeting the Challenges of International Forest Governance; Rayner, J., Buck, A., Katila, P., Eds.; IUFRO: Vienna, Austria, 2010; Volume 28, pp. 111–135. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, S.; Cashore, B. Complex global governance and domestic policies: Four pathways of influence. Int. Aff. 2012, 88, 585–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashore, B.; Galloway, G.; Cubbage, F.; Humphreys, D.; Katila, P.; Levin, K.; Maryudi, A.; McDermott, C.; McGinley, K.; Kengen, S.; et al. Ability of institutions to address new challenges. In Forests and Society—Responding to Global Drivers of Change; Merry, G., Katila, P., Galloway, G., Alfaro, R.I., Kanninen, M., Lobovikov, M., Varjo, J., Eds.; IUFRO (the International Union of Forest Research Organizations): Vienna, Austria, 2010; Volume 25, pp. 441–486. [Google Scholar]

- McGinley, K.; Alvarado, R.; Cubbage, F.; Diaz, D.; Donoso, P.J.; Jacovine, L.A.G.; de Silva, F.L.; MacIntyre, C.; Zalazar, E.M. Regulating the Sustainability of Forest Management in the Americas: Cross-Country Comparisons of Forest Legislation. Forests 2012, 3, 467–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations)/ITTO. Report of Expert Consultation on Criteria and Indicators for Sustainable Forest Management; Discussion Paper 2: Terms and Definitions Related to Criteria and Indicators for Sustainable Forest Management; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- ITTO (International Tropical Timber Organization). Uses and Impacts of Criteria & Indicators for Sustainable Forest Management at the Field/FMU Level and Other Operational Levels; International Tropical Timber Organization: Yokohama, Japan, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). Global Forest Resources Assessment 2010; FAO Forestry Paper 163; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wijewardana, D. Criteria and indicators for sustainable forest management: The road travelled and the way ahead. Ecol. Indic. 2008, 8, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Forum on Forests (UNFF). Report on the Fourth Session. In Proceedings of the Economic and Social Council, Official Records, USA, 6 June 2003 and 3–14 May 2004; Supplement No. 22. Publisher: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- BFD (Bangladesh Forest Department). Protected Areas of Bangladesh. Available online: http://www.bforest.gov.bd/index.php/protected-areas (accessed on 20 January 2015).

- MoEF (Ministry of Environment & Forests). Forest Law & Policy, Act. Available online: http://moef.portal.gov.bd/site/page/f87ea657-1f50-45c8-8fa8-084a066c9d71 (accessed on 20 January 2015).

- United Nations Forum on Forests (UNFF). Country report of Bangladesh: Voluntary National Report to the 9th, 10th, 11th Session of the UN Forum on Forests; Bangladesh Forest Department: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2010; Volume 2012, p. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.S.; Giessen, L. Mapping international forest-related issues and main actors’ positions in Bangladesh. Int. For. Rev. 2014, 16, 586–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, S.; Giessen, L. Identifying the main actors and their positions on international forest policy issues in Argentina. Bosque 2014, 35, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, B. Putting the National back into Forest-Related Policies: The International Forests Regime and National Policies in Brazil and Indonesia. Int. For. Rev. 2008, 10, 523–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization. Global Forest Resources Assessment Report-2010; Country Report-Bangladesh, FRA2010/017; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Kant, S. Bureaucracy and new management paradigms: Modeling foresters’ perceptions regarding community-based forest management in India. For. Policy Econ. 2005, 7, 651–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poffenberger, M. Communities and Forest Management in South Asia; IUCN: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sarker, P.K.; Rodrigo, R. A review of the Status and Trends of Forest Cover in Bangladesh and Philippines. In Proceedings of the 4th International DAAD Workshop on “The Ecological and Economic Challenges of Managing Forested Landscape in a Global Context” from 16.03, Bogor, Indonesia; Jakarta, Indonesia, 16–22 March 2014; Cuvillier Verlag: Gӧttingen, Germany, 2014; Volume 4, pp. 197–208. [Google Scholar]

- The Ministry of Environment & Forests. RIO+ 20 National Report on Sustainable Development; Ministry of Environment and Forests, Bangladesh Secretariat: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2012; p. 37. [Google Scholar]

- Giessen, L.; Krott, M. Forestry Joining Integrated Programmes? A question of willingness, ability and opportunities. Allg. Forst Jagdztg. 2009, 180, 94–100. [Google Scholar]

- Krott, M.; Hasanagas, N.D. Measuring bridges between sectors: Causative evaluation of cross-sectorality. For Policy Econ 2006, 8, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurenhammer, P.K. Development Cooperation Policy in Forestry from an Analytical Perspective; Springer Publications: Dordrecht, The Netherlands; Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sunam, R.K.; Paudel, N.S.; Paudel, G. Community forestry and the threat of recentralization in Nepal: Contesting the bureaucratic hegemony in policy process. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2013, 26, 1407–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutt, R.L.; Lund, J.F. What Role for Government? The Promotion of Civil Society through Forestry-Related Climate Change Interventions in Post-Conflict Nepal. Public Adm. Dev. 2014, 34, 406–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krott, M. Öffentliche Verwaltung im Umweltschutz. Ergebnisse Einer Behördenorientierten Policy-Analyse am Beispiel Waldschutz; W. Braumüller Verlag: Wien, Austria, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Allison, G. Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis; Little Brown and Company: Boston, MA, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, E. Wither the study of governmental politics in foreign policymaking? A symposium. Mershon Int. Stud. Rev. 1998, 42, 205–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, A. The life cycle of bureaus. In Inside Bureaucracy; Waveland Press: Long Grove, IL, USA, 1967; pp. 296–309. [Google Scholar]

- Halperin, M.H.; Clapp, P.A. Bureaucratic Politics and Foreign Policy, 2nd ed.; Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Krott, M.; Bader, A.; Schusser, C.; Devkota, R.; Maryudi, A.; Giessen, L.; Aurenhammer, H. Actor-centered power: The driving force in decentralized community based forest governance. For. Policy Econ. 2014, 49, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alston, M. Women and Climate Change in Bangladesh; Routledge: Abingdon, VA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Das Politische Feld: Zur Kritik der Politischen Vernunft [The Political Field: Contribution to the Coercionitique of Political Reason]; UVK-Verl: Konstanz, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, R.A. The concept of power. Behav. Sci. 1957, 2, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukes, S. Power: A Radical View; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, E.W. Locating international REDD+ power relations: Debating forests and trees in international climate negotiations. Geoforum 2015, 66, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzioni, A. Die Aktive Gesellschaft; Westdeutscher Verlag: Opladen, Germany, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Maryudi, A.; Citraningtyas, E.R.; Purwanto, R.H.; Sadono, R.; Suryanto, P.; Riyanto, S.; Siswoko, B.D. The emerging power of peasant farmers in the tenurial conflicts over the uses of state forestland in Central Java, Indonesia. For. Policy Econ. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schusser, C.; Krott, M.; Movuh, M.C.Y.; Logmani, J.; Devkota, R.R.; Maryudi, A.; Salla, M.; Bach, N.D. Powerful stakeholders as drivers of community forestry—Results of an international study. For Policy Econ. 2015, 58, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devkota, R.R. Interest and Power as Drivers of Community Forestry; Universitätsverlag Goettingen: Goettingen, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Maryudi, A. The Contesting Aspirations in the Forest-Actors Interests and Power in Community Forestry in Java, Indonesia; Universitätsverlag Goettingen: Goettingen, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Schusser, C. Who determines biodiversity? An analysis of actors’ power and interests in community forestry in Namibia. For. Policy Econ. 2013, 36, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schusser, C.; Krott, M.; Logmani, J. The Applicability of the German Community Forestry Model to Developing Countries. Forstarchiv 2013, 84, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Movuh, Y.M.C.; Schusser, C. Power, the hidden factor in development cooperation-an example of community forestry in Cameroon. Open J. For. 2012, 2, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maryudi, A.; Devkota, R.R.; Schusser, C.; Yufanyi, C.; Salla, M.; Aurenhammer, H.; Rotchanaphatharawit, R.; Krott, M. Back to basics: Considerations in evaluating the outcomes of community forestry. For. Policy Econ. 2012, 14, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, J.; Howlett, M. Introduction: Understanding integrated policy strategies and their evolution. Policy Soc. 2009, 28, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinschmit, D.; Edwards, P. Die paneuropäische Waldpolitik auf dem Weg zum Regime: Strukturierte Betrachtung der Verhandlung eines rechtlich bindenden Waldinstruments. Allg. Forst Jagdztg. 2013, 184, 38–47. [Google Scholar]

- Brukas, V.; Hjortso, C.N. A power analysis of international assistance to Lithuanian Forestry. Scand. J. For. Res. 2004, 19, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheba, A.; Mustalahti, I. Rethinking “expert” knowledge in community forest management in Tanzania. For. Policy Econ. 2015, 60, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Forest Policy (NFP). Ministry of Environment and Forests; Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 1994.

- Forestry Master Plan (FMP). Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. Main Plan—1993/2013; Asian Development Bank (TA No. 1355-BAN), UNDP/FAO BGD/88/025, Asian Development Bank: Manila, Philippines, 1993; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF). Project Progress Reporting Document of Sundarbans Protected Area Management Assistance Project; Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2014.

- Social Forestry Rules. Ministry of Environment and Forest; Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2004.

- Ministry of Environment and Forests. Project Progress Reporting Document of Resource Conservation through Community Reforestation and Forest Management in Chunati Wildlife Sanctuary, Chittagong Project; Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2014.

- UN-REDD programme. Bangladesh REDD+ Readiness Roadmap; UN-REDD Program (Draft 1.3); UN-REDD programme: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- GoB (Government of Bangladesh). Sixth Five Year Plan 2011–2015: Accelerating Growth and Reducing Poverty; General Economics Division, Planning Commission, Ministry of Planning; Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2011.

- Ministry of Environment and Forests. Project Progress Reporting Document of Bangobondhu Sheikh Mujib Safari Park, Cox’s Bazar Development Project; Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2014.

- World Bank. Staff Appraisal Report-Forest Resources Management Project, Bangladesh. 1992. Available online: http://www.documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/1992/05/736646/bangladesh-forest-resources-management-project (accessed on 23 June 2014).

- Asian Development Bank (ADB). Project Completion Report, Coastal Greenbelt Project in the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. PCR: BAN 25311. 2005. Available online: http://www.adb.org/projects/documents/coastal-greenbelt-project (accessed on 20 June 2014).

- Ministry of Environment and Forests. Project Progress Reporting Document of Afforestation in the Unclassified State Forests, Reserve Forests and Private Owned Forests of CHTs Project; Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2014.

- DPP (Development Project Proposal). Development Project Proposal of Strengthening Regional Cooperation for Wildlife Protection Project; Development Planning Unit, Ministry of Environment and Forests; Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2011.

- Planning Commission (PC). Annual Development Programme 2014–2015. Ministry of Planning, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. 2014. Available online: http://www.plancomm.gov.bd/upload/2014/adp_14_15/agri_ta.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Validation Report of Bangladesh: Sundarbans Biodiversity Conservation Project. 2008. Available online: http://www.adb.org/documents/bangladesh-sundarbans-biodiversity-conservation-project (accessed on 23 June 2014).

- Salam, M.A.; Noguchi, T. Evaluating capacity development for participatory forest management in Bangladesh’s Sal forests based on “4Rs” stakeholder analysis. For Policy Econ. 2006, 8, 785–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, L.M.; Vainio-Mattila, A. Participatory development and community-based conservation: Opportunities missed for lessons learned? Hum. Ecol. 2003, 31, 417–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Gibson, C.C. (Eds.) Communities and the Environment: Ethnicity, Gender, and the State in Community-Based Conservation; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2001; p. 224.

- Rahman, M.S.; Sarker, P.K.; Giessen, L. Which agencies gain power from biodiversity policies? Insights from twenty years of international and domestic forest-biodiversity initiatives in Bangladesh. Land Use Policy 2016. under review. [Google Scholar]

- Brockhaus, M.; Di Gregorio, M.; Mardiah, S. Governing the design of national REDD+: An analysis of the power of agency. For. Policy Econ. 2014, 49, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoke, D.; Pappi, F.U.; Broadbent, J.; Tsujinaka, Y. Comparing Policy Networks: Labor Politics in the U.S., Germany, and Japan; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996; Available online: http://www.dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139174497 (accessed on 30 March 2016).

- Kriesi, H.; Jegen, M. The Swiss energy policy elite: The actor constellation of a policy domain in transition. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 2001, 39, 251–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, K.K.; Kimihiko, H.; Takahiro, F.; Sato, N. Confronting people-oriented forest Management realities in Bangladesh: An Analysis of actors’ perspective. Int. J. Soc. For. 2011, 4, 153–179. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, S.; Cashore, B. Globalization, Four Paths of Internationalization and Domestic Policy Change: The Case of Eco Forestry in British Columbia, Canada. Can. J. Polit. Sci. Rev. Can. Sci. Polit. 2000, 33, 67–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahide, M.A.K.; Giessen, L. The fragmented land use administration in Indonesia-Analysing bureaucratic responsibilities influencing tropical rainforest transformation systems. Land Use Policy 2015, 43, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongolo, S. On the banality of forest governance fragmentation: Exploring “gecko politics” as a bureaucratic behavior in limited statehood. For. Policy Econ. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogl, K.; Nordbeck, R.; Kvarda, E. When international impulses hit home: The role of domestic policy subsystem configurations in explaining different types of sustainability strategies. For. Policy Econ. 2009, 11, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evart, V. Policy instrument: Typologies and theories. In Carrots, Sticks & Sermons Policy Instruments and Their Evaluation; Bemelmans-Videc, M.L., Rist, R.C., Vedung, E.O., Eds.; Transaction Publishers: New Brunswick, NJ, USA; London, UK, 1998; Volume 7, pp. 21–58. [Google Scholar]

- Aurenhammer, P.K. Network analysis and actor-centred approach—A critical review. For. Policy Econ. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Gibson, C.C. Enchantment and disenchantment: The role of community in natural resource conservation. World Dev. 1999, 27, 629–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackleton, S.; Campbell, B.; Wollenberg, E.; Edmunds, D. Devolution and community-based natural resource management: Creating space for local people to participate and benefit? Nat. Resour. Perspect. 2002, 76, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Faye, P. Choice and power: Resistance to technical domination in Senegal’s Forest Decentralization. For. Policy Econ. 2014, 60, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šálka, J.; Zuzana, D.; Zuzana, H. “Factors of political power—The example of forest owners associations in Slovakia”. For. Policy Econ. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaikie, P.; Springate-Baginski, O. Understanding the policy process. In Forests People and Power: The Political Ecology of Reform in South Asia; Springate-Baginski, O., Blaikie, P., Eds.; Eartscan: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Schusser, C.A.; Krott, M.; Devkota, R.; Maryudi, A.; Salla, M.A.; Yufanyi Movuh, M.C. Sequence design of quantitative and qualitative surveys for increasing efficiency in forest policy research. Allg. Forst Jagdztg. 2012, 183, 75–83. [Google Scholar]

| Element | Definition | Observable Facts | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coercion | Altering behavior by force | Physical action, threat for physical action or sources for physical action | Removal of forest user rights |

| (Dis-)incentives | Altering behavior by (dis-)advantage | Providing of, or threat with, sources of material or immaterial benefit or impairment | Financial support from donors to carry out forest management plan |

| Dominant information | Altering behavior by means of unverified information | Providing of, or threat with, sources of unverified information | Expert knowledge about how to conserve protected areas through co-management |

| Policy Cycle | Categories of Strategic Tasks Typically Found in Selected Policies | Examples of Power Features |

|---|---|---|

| Formulation | Preparation and further revision of a policy | The BFD prepared “National Forest Policy” in 1994 (NFP (National Forest Policy) 1994 [82]) |

| Initiation, guidance and/or coordination to policy preparation or revision | The MoEF initiated and provided guidance for preparation of the “Forestry Master Plan” in 1993 (Forestry Master Plan (FMP) 1993 [83]) | |

| Approval of funding, manpower | The Planning Commission, MoEF and Finance Division approved project document and fund for implementing the “Sundarbans Protected Area Management Assistance” project in 2005 (MoEF (Ministry of Environment and Forests) 2014 [84]) | |

| Approval of the policy | The MoEF and ADB approved the “Social Forestry Rules 2004” (Social Forestry Rules 2004 [85]) | |

| Implementation | Financial and technical assistance to implement a policy | GIZ provided financial and technical assistance to implement “Resource Conservation through Community Reforestation and Forest Management in Chunati Wildlife Sanctuary” project in 2011 (MoEF 2014 [86]) |

| Establishment of a REDD cell to deal with the REDD activities | The BFD established a REDD cell to perform all REDD relevant activities according to the “Bangladesh REDD+ Readiness Roadmap 2012” (Bangladesh REDD+ Readiness Roadmap 2012 [87]) | |

| Declaration and management of protected areas, ecological critical areas, eco-park, botanical garden, etc. | The MoEF and BFD is responsible for increasing the protected areas as stated in the National Forest Policy-1994 (NFP 1994 [82]) | |

| Coordination and collaboration at national, regional and international level | The National Sixth Five Year Plan-2011, stated the collaboration and coordination with global and regional partners by the MoEF, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Economic Relations Division (ERD) (GoB (Government of Bangladesh) 2011 [88]) | |

| Create awareness among national stakeholders | The BFD organized the National Forestry Congress-2011 as a response to the UN Assembly declaration, “2011 for creating awareness among stakeholders’’ (UN Forum on Forests (UNFF) 2012 [43]) | |

| Protect, recover and restore of forest biological resources through habitat management and afforestation | The BFD implemented “Establishment of Sheikh Mujib Safari Park, Gajipur project” for habitat conservation and development of forest and wildlife in 2010 (MoEF 2014 [89]) | |

| Carry out inventories, prepare and update management plan, and develop database for sustainable management of forest biodiversity | The BFD carried out inventories and prepared management plan of forest resources through “Forest Resources Management Project” in 1992 (World Bank 1992 [90]) | |

| Establish multipurpose plantation on roadside, beside railway lines and embankment plantation, homestead and institution plantation and trial foreshore plantation | The BFD implemented the planation activities through the ADB funded “Coastal Green Belt Project in 1995 (Asian Development Bank (ADB) 2005 [91]) | |

| Extraction of the infected Sundri (Heritiera Fomes) trees | The BFD extracted top dying infected Sundri trees from the infected areas and carried out enrichment plantation in the gaps created in the Sundarban Forests, 1995 (MoEF 2014 [92]) | |

| Monitoring and evaluation | Monitoring and Evaluation of project activities | The Implementation Monitoring and Evaluation Division (IMED), MoEF, BFD, World Bank, Planning Commission were responsible for monitoring and evaluating project activities of “Strengthening Regional Cooperation for Wildlife Protection Project” 2011 (DPP (Development Project Proposal) 2011 [93]) |

| Evaluation of policy tasks | The IMED ensures evaluation of policy tasks for “National Bio-safety Plan of Action ” project in 2013 (PC (Planning Commission) 2014 [94]) | |

| Audit of financial activities | The office of the Comptroller and Auditor General (C & AG) conduct audit of financial activities, for example, “Sundarbans Biodiversity Conservation Project” in 1999 (ADB 2008 [95]) |

| Identified Competent Bureaucracies | Total Tasks | Dominant Information | Incentives | Coercion | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No’s | Percentage (%) | No’s | Percentage (%) | No’s | Percentage (%) | ||

| Domestic Bureaucracies | |||||||

| Ministry of Environment & Forests (MoEF) | 396 | 160 | 23.49 | 60 | 18.24 | 176 | 35.27 |

| Bangladesh Forest Department (BFD) | 391 | 184 | 27.02 | 183 | 55.62 | 24 | 4.81 |

| Planning Commission (PC) | 240 | 83 | 12.19 | 7 | 2.13 | 150 | 30.06 |

| Department of Environment (DoE) | 126 | 58 | 8.52 | 50 | 15.20 | 18 | 3.61 |

| Finance Division (FD) | 109 | 3 | 0.44 | 8 | 2.43 | 98 | 19.64 |

| Implementation, Monitoring and Evaluation Division (IMED) | 74 | 74 | 10.87 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Office of the Comptroller and Auditor General (C & AG) | 74 | 74 | 10.87 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Economic Relations Division (ERD) | 72 | 35 | 5.14 | 4 | 1.22 | 33 | 6.61 |

| Bangladesh Forest Research Institute (BFRI) | 27 | 10 | 1.47 | 17 | 5.17 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Sub-total | 1509 | 681 | 100 | 329 | 100 | 499 | 100 |

| Foreign Donor Bureaucracies | |||||||

| United Nations Development Program (UNDP) | 36 | 13 | 23.64 | 22 | 25.58 | 1 | 25.00 |

| Asian Development Bank (ADB) | 25 | 9 | 16.36 | 15 | 17.44 | 1 | 25.00 |

| World Bank (WB) | 22 | 10 | 18.18 | 10 | 11.63 | 2 | 50.00 |

| United States Agency for International Development (USAID) | 20 | 11 | 20.00 | 9 | 10.47 | 0 | 0.00 |

| International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) | 13 | 5 | 9.09 | 8 | 9.30 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Global Environmental Facility (GEF) | 12 | 0 | 0.00 | 12 | 13.95 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) | 10 | 5 | 9.09 | 5 | 5.81 | 0 | 0.00 |

| German Federal Enterprise for International Cooperation (GIZ) | 7 | 2 | 3.64 | 5 | 5.81 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Sub-total | 145 | 55 | 100 | 86 | 100 | 4 | 100 |

| Total | 1654 | 736 | 44.50 | 415 | 25.09 | 503 | 30.41 |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giessen, L.; Sarker, P.K.; Rahman, M.S. International and Domestic Sustainable Forest Management Policies: Distributive Effects on Power among State Agencies in Bangladesh. Sustainability 2016, 8, 335. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8040335

Giessen L, Sarker PK, Rahman MS. International and Domestic Sustainable Forest Management Policies: Distributive Effects on Power among State Agencies in Bangladesh. Sustainability. 2016; 8(4):335. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8040335

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiessen, Lukas, Pradip Kumar Sarker, and Md Saifur Rahman. 2016. "International and Domestic Sustainable Forest Management Policies: Distributive Effects on Power among State Agencies in Bangladesh" Sustainability 8, no. 4: 335. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8040335

APA StyleGiessen, L., Sarker, P. K., & Rahman, M. S. (2016). International and Domestic Sustainable Forest Management Policies: Distributive Effects on Power among State Agencies in Bangladesh. Sustainability, 8(4), 335. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8040335