Enhancing Economic Sustainability by Markdown Money Supply Contracts in the Fashion Industry: China vs U.S.A.

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- What strategies do the fashion firms take for enhancing economic sustainability when they adopt MMP in their business?

- (2)

- How does cross-cultural perspectives affect MMP implementation for enhancing economic sustainability?

- (3)

- What are the managerial implications and insights based on a cross-cultural analysis between the East and the West?

- (4)

- What are the main challenges and future research directions for supply chain contracting in the fashion industry?

2. Literature Review

3. Cases Study

3.1. Methodology

3.2. Case 1—LC

3.2.1. Company Overview

3.2.2. Implementation of MMP

“We designed a new plan from the retailer every six months, which can vary from season to season, but only slightly. However, JC Penney required us to guarantee a margin by the end of the season. They may tell us at the beginning of the season that they wanted our product to net a 55% margin. So however we got there, either by markdown money or great sell through, it does not matter.”

“Willingly or unwillingly, we happily trade time for comfort. The most expensive elements of a slow time to market do not even appear on the cost sheets: the costs of markdowns” [41].

“We know what we have to achieve at the beginning of the season, so we can plan our product and the recommended quantity buys accordingly. We work closer and our relationship is more like a team. But still when the product sells and the retailer are making money, they love us! If our product does not sell, then there is not that much love.”

3.3. Case 2—LX

3.3.1. Company Overview

3.3.2. Implementation of MMP

“We try to help our retailers to sell quickly and reduce the inventory. We give them some support such as providing markdown money and even allow them to return. Our online platform in Taobao operates well, in which we can sell the items returned by our retailers. However, the business is getting more and more difficult in China, and we are now facing heavy pressure on inventory. So our management board is thinking to reform our distribution channel. Maybe in the future, we just allow quantity-restricted returns or even do not allow any.”

“Our retailers are sometimes introduced by good and reliable friends. As such, we are more confident to have them. However, we still have very strict requirement when we select the retailers in the specified location or region. We require our retailers who have experience in fashion retailing and healthy cash flow.”

4. Case Insights Summary

4.1. Summary of LC Case

4.2. Summary of LX Case

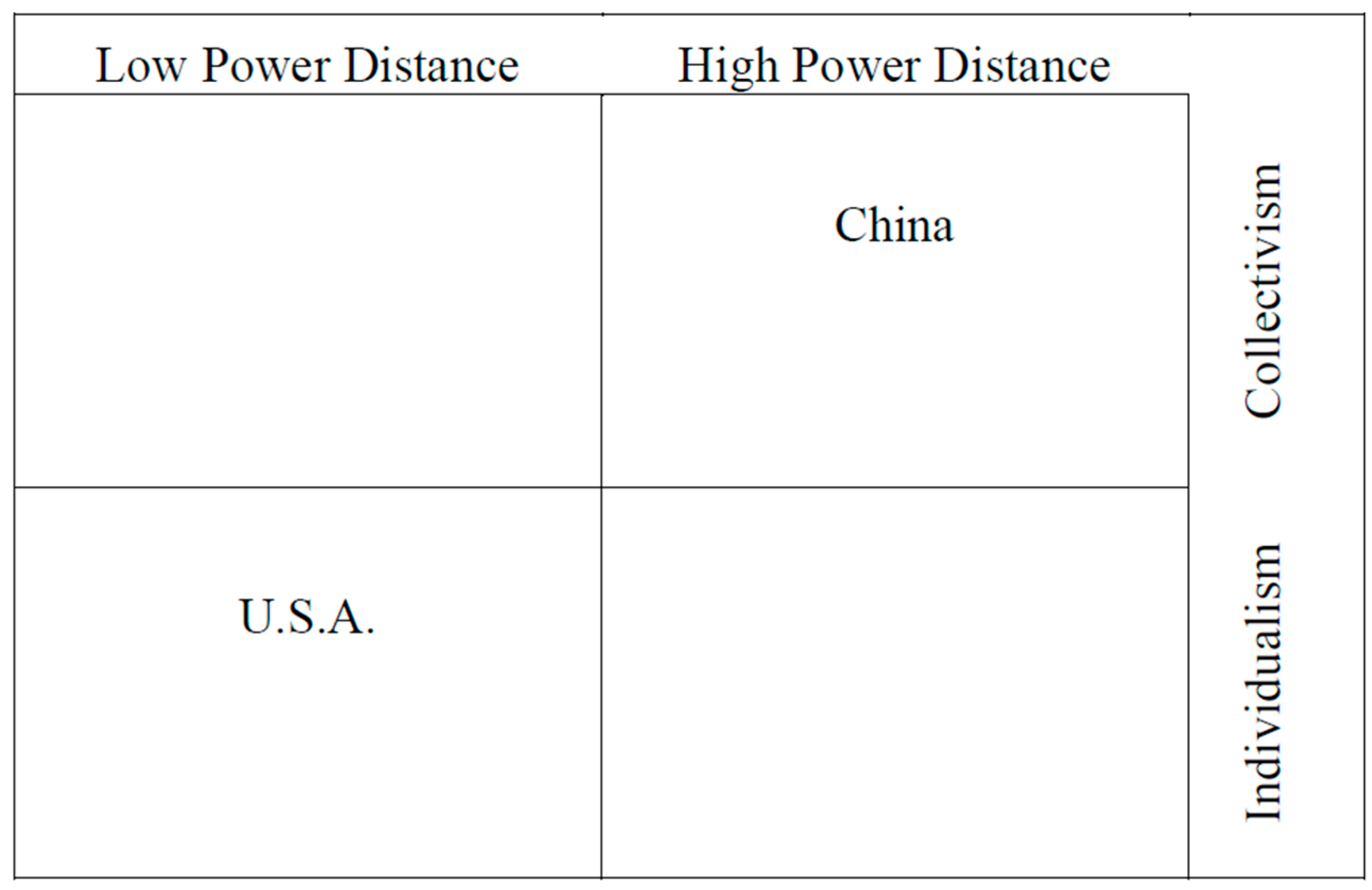

5. Implications

| China | U.S.A. |

|---|---|

| Chinese fashion companies with a stronger bargaining power are more willing to manage the supply chain. | American fashion companies with less strong bargaining power have to bargain with his retailers and show their sense of fairness. |

| Chinese fashion firms prefer dynamic contract. | American fashion firms believe that the formal contracts could ensure their own interests. |

| Chinese fashion firms hold a stronger leadership in supplier side. | American fashion firms hold a stronger leadership in retailer side. |

| Chinese fashion firms care more about guanxi. | American fashion firms pay more attention to contracts than their relationship with their partners. |

6. Conclusions, Future Research Opportunities and Limitations

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflict of Interests

Appendix: Interview Questions

- Could you please introduce your company?

- What kind of supply chain contracts are you adopting with your retail buyers and how?

- How would you evaluate the adopted supply chain contracts with your retailers?

- Have the adopted supply chain contracts helped to build up the good relationship with your retail buyers and how?

- Do you expect these adopted supply chain contracts be used in a longer- or shorter-term?

- How would you describe the relationship between you and your retail buyers?

- Who is responsible for managing this relationship and how?

References

- Choi, T.M.; Chiu, C.H.; To, K.M. A fast fashion safety-first inventory model. Text. Res. J. 2010, 81, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B. Sustainable fashion supply chain: lessons from H&M. Sustainability 2014, 6, 6236–6249. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, C.H.; Choi, T.M.; Tang, C.S. Price, rebate, and returns supply contracts for coordinating supply chains with price dependent demand. Prod. Op. Manag. 2011, 20, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozhon, T. First the markdown, then the showdown. New York Times 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, B.; Li, Q. Impacts of returning unsold products in retail outsourcing fashion supply chain: A sustainability analysis. Sustainability 2015, 7, 1172–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, T.M.; Li, D.; Yan, H.M. Mean-variance analysis of a single supplier and retailer supply chain under a returns policy. Eur. J. Op. Res. 2008, 184, 356–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasternack, B.A. Optimal pricing and returns policies for perishable commodities. Mark. Sci. 1985, 4, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, H.S.; Lau, A.H.L. Manufacturer’s pricing strategy and returns policy for a single-period commodity. Eur. J. Op. Res. 1999, 116, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausman, W.H.; Thorbeck, J.S. Fast fashion: Quantifying the benefits. In Innovative Quick Response Programs in Logistics and Supply Chain Management; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2010; pp. 315–329. [Google Scholar]

- Chargeback reform: Vendors hope probes level the playing field. Women’s Wear Daily 2005.

- Cachon, G. Supply chain coordination with contracts. In Handbooks in operations Research and Management Science: Supply Chain Management; de Kok, A.G., Graves, S.C., Eds.; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, B.; Choi, T.M.; Wang, Y.; Lo, K. The coordination of fashion supply chains with a risk averse supplier under the markdown money policy. Syst. Man Cybern. 2013, 43, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro, F.; Gallien, J. Clearance pricing optimization for a fast-fashion retailer. Op. Res. 2012, 60, 1404–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mersereau, A.J.; Zhang, D. Markdown pricing with unknown fraction of strategic customers. Manuf. Serv. Op. Manag. 2012, 14, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.; Aviv, Y.; Pazgal, A.; Tang, C.S. Optimal markdown pricing: Implications of inventory display formats in the presence of strategic customers. Manag. Sci. 2009, 55, 1391–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Chow, P.S.; Choi, T.M. Supply chain contracts in fashion department stores: Coordination and risk analysis. Math. Probl. Eng. 2014, 2014. Article 954235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagell, M.; Katz, J.P.; Sheu, C. The importance of national culture in operations management research. Int. J. Op. Prod. Manag. 2005, 25, 371–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Huo, B.; Flynn, B.B.; Yeung, J. The impact of power and relationship commitment on the integration between manufacturers and customers in a supply chain. J. Op. Manag. 2008, 26, 368–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, F.; Lamming, R. Cultural adaptation in Chinese-Western supply chain partnerships: Dyadic learning in an international context. Int. J. Op. Prod. Manag. 2013, 33, 528–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, T. J. Retailers expected to seek more markdown money this yule: Factors call it a bigger problem for vendors than the stock market or Asia. Daily News Record 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.X.; Webster, S. Markdown money contracts for perishable goods with clearance pricing. Eur. J. Op. Res. 2009, 196, 1113–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsay, A.A. Managing retail channel overstock: markdown money and return policy. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 457–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Rhee, B.D. Optimal guaranteed profit margins for both vendors and retailers in the fashion apparel industry. J. Retail. 2008, 84, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishan, H.; Kapuscinski, R.; Butz, D.A. Coordinating contracts for decentralized supply chains with retailer promotional effort. Manag. Sci. 2004, 50, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, T.; Jin, J. Coordination of a fashion apparel supply chain under lead-time-dependent demand uncertainty. Prod. Plan. Control 2011, 22, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, T.M. Game theoretic analysis of a multi-period fashion supply chain with a risk averse retailer. Int. J. Inventory Res. 2013, 2, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, P.S.; Wang, Y.; Choi, T.M.; Shen, B. An experimental study on the effects of minimum profit share on supply chains with markdown contract: Risk and profit analysis. Omega 2015, 57, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Zhao, D.; Xia, L. Game theoretic analysis of carbon emission abatement in fashion supply chains considering vertical incentives and channel structures. Sustainability 2015, 7, 4280–4309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, P.; Govindan, K.; Choi, T.M.; Rajendran, S. Supplier selection problems in fashion business operations with sustainability considerations. Sustainability 2015, 7, 1603–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zhao, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Choi, T.M. Cooperation or competition? Channel choice for a remanufacturing fashion supply chain with government subsidy. Sustainability 2015, 6, 7292–7310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, T.M. Carbon footprint tax on fashion supply chain systems. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2013, 68, 835–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metters, R.; Zhao, X.; Bendoly, E.; Jiang, B. The way that can be told of is not an unvarying way: Cultural impacts on operations management in Asia. J. Op. Manag. 2010, 28, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequence: International Differences in Work-Related Values; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, S.; Minjoon, J.; Yang, Z. Implementing supply chain information integration in China: The role of institutional forces and trust. J. Op. Manag. 2010, 28, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, P.; Liu, Y.; Yang, D. Learning trajectory in offshore OEM cooperation: Transaction value for local suppliers in the emerging economies. J. Op. Manag. 2010, 28, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Oliva, R.; Watson, N. Cross-functional alignment in supply chain planning: A case study of sales and operations planning. J. Op. Manag. 2011, 29, 434–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, L.; Bounds, W. Stores’ demands squeeze apparel companies. Wall Str. J. 1997, 230, B1–B3. [Google Scholar]

- Edelson, S. A business practice’s evolution. Women’s Wear Daily 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan, T.V.; Soni, H. Guaranteed profit margins: A demonstration of retail power. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1997, 14, 35–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckett, W. Industry insiders: Speed to market wins. Women’s Wear Daily 2006, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith, D.A.; Myers, M.B. The performance implications of strategic fit of relational norm governance strategies in global supply chain relationships. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2005, 36, 254–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasimhan, R.; Nair, A.; Griffith, D.A.; Arlbjørn, J.S.; Bendoly, E. Lock-in situations in supply chains: A social exchange theoretic study of sourcing arrangements in buyer–supplier relationships. J. Op. Manag. 2009, 27, 374–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.Y.; Clegg, S. Trust and decision making: are managers different in the People’s Republic of China and in Australia? Cross-Cult. Manag. 2002, 9, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, T.R.; Ruffle, B.J. Self-serving bias. J. Econ. Perspect. 1998, 12, 243–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.C.; Choi, T.M.; Au, R.; Hui, C.L. Individual tourists from the Chinese Mainland to Hong Kong: implications for tourism marketing in fashion. Tour. Econ. 2011, 17, 1287–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, T.M.; Liu, S.C.; Pang, K.M.; Chow, P.S. Shopping behavior of individual tourists from the Mainland China. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 811–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, A.V.; Schwarz, L.B.; Zenios, S.A. A principal-agent model for product specification and production. Manag. Sci. 2005, 51, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, P.; Clegg, J.; Wang, C. The impacts of FDI on the performance of Chinese manufacturing firms. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2002, 33, 637–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randolph, W.A.; Sashkin, M. Can organizational empowerment work in a multinational setting? Acad. Manag. Exec. 2002, 16, 102–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, G.J.; Zhou, N. The Relationship between Power and Dependence in Marketing Channels: A Chinese Perspective. Eur. J. Mark. 2004, 38, 675–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A. Managing with power: strategies for improving value appropriation from supply relationships. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2001, 37, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Zhang, F. Strategic customer behavior, commitment, and supply chain performance. Manag. Sci. 2008, 54, 1759–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, F.; Zhang, Z. Cross-cultural challenges when doing business in China. Singap. Manag. Rev. 2004, 26, 81–91. [Google Scholar]

- Ellram, L.M.; Cooper, M.C. Supply chain management, partnerships, and the shipper-third-party relationship. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 1990, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shen, B.; Choi, T.-M.; Lo, C.K.-Y. Enhancing Economic Sustainability by Markdown Money Supply Contracts in the Fashion Industry: China vs U.S.A. Sustainability 2016, 8, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8010031

Shen B, Choi T-M, Lo CK-Y. Enhancing Economic Sustainability by Markdown Money Supply Contracts in the Fashion Industry: China vs U.S.A. Sustainability. 2016; 8(1):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8010031

Chicago/Turabian StyleShen, Bin, Tsan-Ming Choi, and Chris Kwan-Yu Lo. 2016. "Enhancing Economic Sustainability by Markdown Money Supply Contracts in the Fashion Industry: China vs U.S.A." Sustainability 8, no. 1: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8010031

APA StyleShen, B., Choi, T.-M., & Lo, C. K.-Y. (2016). Enhancing Economic Sustainability by Markdown Money Supply Contracts in the Fashion Industry: China vs U.S.A. Sustainability, 8(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8010031