1. Introduction: SDGs between Universality and Diversity

After more than 20 years of work and research on sustainable development (SD) policies, strategies and procedural approaches in general, the importance of governance for SD is uncontested. While not entirely new in light of the global challenge of moving towards SD, the Post 2015 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) will pose particular challenges on the governance aspects of their implementation. For the first time in history, Heads of States will adopt [

1] at the United Nations (UN) level

universally applicable goals and targets for all aspects of SD, in contrast to the sectoral goals and targets under global conventions such as the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), as a set of goals succeeding the Millennium Development Goals that expire in 2015. While the SDGs as proposed by the UN Open Working Group [

2] are qualitative expressions and also the sub-goals (or “targets” [

3]) are predominantly qualitative, the latter all have a desired direction, which mostly comes with a target year or timeline (mostly 2030). Some sub-goals/targets are quantified. As the political and academic debates have shown, and even more revealing when it comes to indicators for measuring progress, the more things become concrete, the more the challenge arises between, on the one hand, universally applicable goals and (quantified) targets, and, on the other hand, the need for diversification at the levels of implementation. This challenge materializes predominantly at national level, but also subnational [

4].

That different levels of administration should develop their own, specific approach to translate globally agreed policies and targets was already identified in 1992 and enshrined as Principle 7—“Common but Differentiated Responsibility (CBDR)”—in the Rio Declaration [

5]. However, this Principle has become somewhat a stalling argument, caught in the focus on financing—as can also be observed in the UN negotiations on Means of Implementation—and in general in a North–South dichotomy, while the world is facing an “explosion of complexity” [

6] (p. 1). Indeed, the world is different than in 1992—be it only because of the evolvement of “emerging economies” and “newly industrialized countries” and their rising middle-classes. Moreover, the world is interconnected through information and communication technology, and social media have emerged as powerful means to induce change.

An overall proxy for CBDR has been suggested by Kitzes

et al. [

7] in the context of sustainable consumption and production (SCP) as “shrink and share”, which is a translation of the concept of contraction (of their footprint) and convergence (into the sustainable quadrant of the HDI/Footprint matrix) [

8]. It points to the responsibility of developed countries beyond providing financial means, namely working in their own realm on their ecological footprint. On the flip side the issue of population growth cannot be neglected [

9], neither can the fact that some middle-income countries have a higher total footprint or greenhouse gas emission levels than Western countries, though not (yet) per capita [

10]. The aim of contraction and convergence would be to achieve a higher Human Development Index (HDI), for example, with only modestly increasing the footprint [

11]. Differentiated development trajectories would mean that all countries aim to reach “sustainable human development”, as UNDP depicted it in its Human Development Report 2013 [

12] (p. 35). Paragraph 247 of the Rio+20 Outcome document [

13] touches upon the concept of CBDR, but it does not follow the North–South divide and with that enables a finer differentiation between countries, namely according to their capacities [

14] (p. 5).

What about governance—the way the global goals will be translated at national and other levels? In this article, this question is addressed as follows.

Section 2 defines SDG governance and suggests a guiding principle.

Section 3 discusses characteristics of sustainable development governance and reflects which role the concept of metagovernance might play for designing and managing SDG governance frameworks. It is illustrated for a number of SDG sub-goals what applying the guiding principle in combination with metagovernance thinking could bring about (

Section 5). In

Section 6, a step-by-step approach to implementing the SDGs will be suggested.

Section 7 provides a summary and outlook.

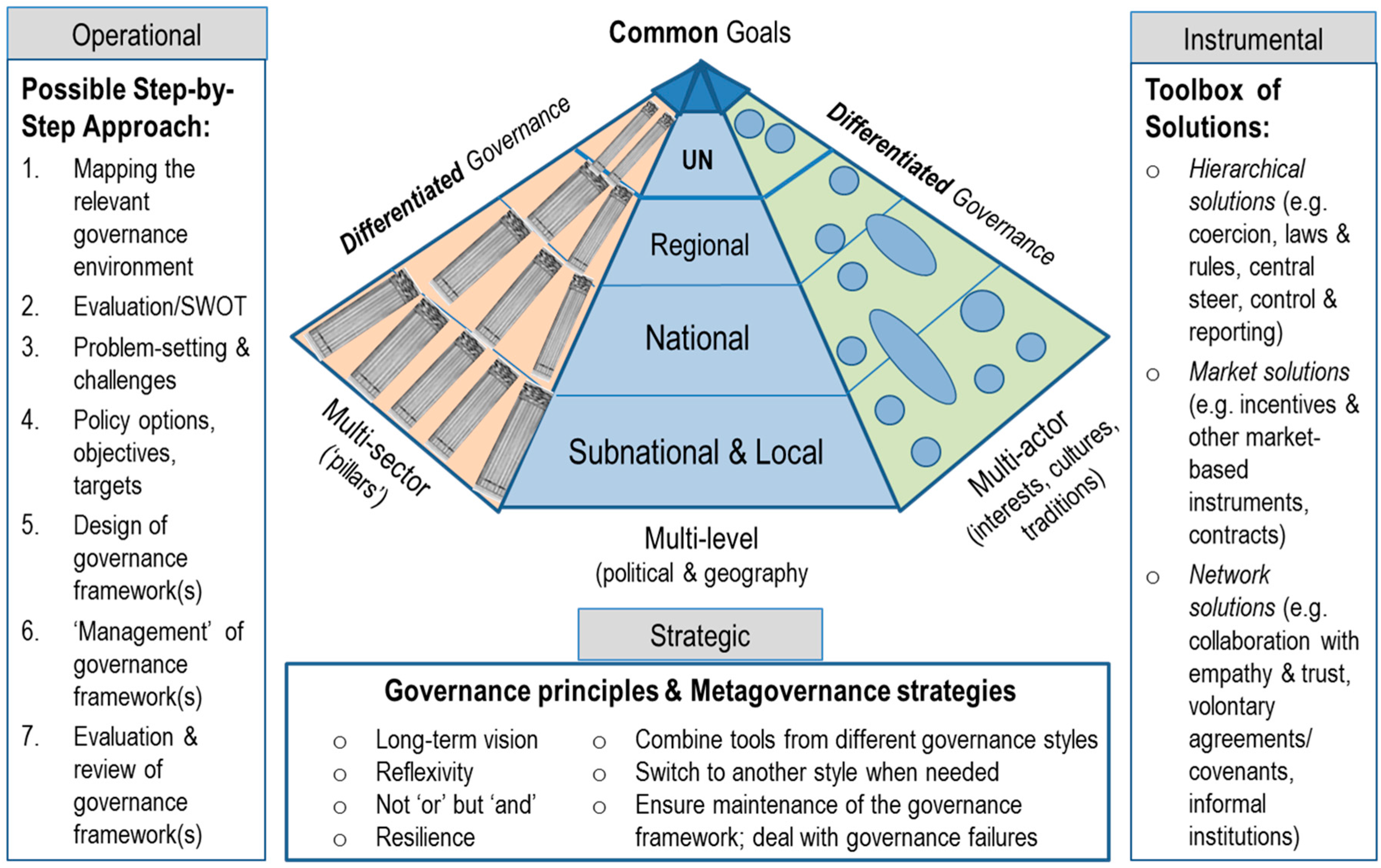

Figure 1 summarizes the article in one graphic overview, which may be used as a reference “mind map” during the setting up and management of governance frameworks for the implementation of the SDGs.

Figure 1.

Common but Differentiated Governance for the Sustainable Development Goals: A “mind map” (own composition).

Figure 1.

Common but Differentiated Governance for the Sustainable Development Goals: A “mind map” (own composition).

2. The Principle of “Common But Differentiated Governance” (CBDG)

Based on the set of SDGs and targets to be adopted in September 2015 at the UN Summit on the post-2015 development agenda in New York, nation states will not only need to define specified targets and (sub-)timelines reflecting their situation, but they also need to design corresponding processes for implementation. There is a need for “mindful approaches and means to get from A to B, whether it is called a plan, strategy, roadmap, action plan or transition pathway” [

15] (p. 143). “Mindful” is used here in the connotation of combining ongoing scrutiny of existing expectations, bringing in new experiences, the willingness and capability to make sense of unprecedented events, dealing with context and improve foresight [

16] (pp. 41ff).

Implementation of the SDGs requires systemic thinking:

comprehensive approaches (taking into account all relevant aspects) and, in addition, a

holistic view. The latter implies trying to keep in mind the importance of the whole and the interdependence of its parts, both horizontally and vertically (downstream as well as upstream). Horizontal coordination is essential because progress in one goal area could generate positive spillover effects in others, which may not be recognized in the absence of such coordination [

17].

As already identified in Agenda 21 [

18] and further elaborated, researched and underpinned ever since, developing and implementing of SD policies (

i.e., including goals and targets) takes place in a multi-sector, multi-level and multi-actor setting. Other key elements to take into account are [

19] (p. 536), [

15] (pp. 143–145), [

20] (pp. 17–19):

The knowledge dimension, including the quality of the science-policy interface;

Reflexivity (social systems change as result of interactions with their environment, be it consciously or not); and

The time dimension, including intergenerational justice, and in particular bringing in the long-term perspective in predominantly short-term mechanisms of politics and economy.

All these are dimensions of governance that will need to be considered and tackled in future “mindful approaches” for implementing the SDGs.

In this article we define the term

governance broadly, in order to cover all governance styles and definitions of specific governance approaches and excluding none of them. A broad definition that emphasizes the relational dimension of governance is “Governance is the totality of interactions, in which government, other public bodies, private sector and civil society participate, aiming at solving societal problems or creating societal opportunities” [

21] (p. 11). Another broad definition adds the normative dimension: Governance is “a collection of normative insights into the organization of influence, steering, power, checks and balances in human societies” [

22] (p. 9).

Governance styles can be defined as “the processes of decision-making and implementation, including the manner in which the organizations involved relate to each other” [

23]. Three ideal-typical (in Weberian sense) [

24] governance styles are usually distinguished: hierarchical, network and market governance—and variations [

21,

25,

26,

27,

28]. They seem to reflect the three main “ways of life” distinguished in cultural theory: “hierarchism”, “egalitarism” and “autonomism” [

21] (pp. 57–61), [

29].

A

governance framework can be defined as “the totality of instruments, procedures, processes and role division among actors designed to tackle a group of societal problems” [

30] (p. 886).

Every country has a different “starting point” and preference for a governance style (combination), due to constitutional settings, traditions, culture, political practice, geography and resulting environmental, social and economic circumstances. Empirical research on governance for SD suggests, however, that countries (or entities at other levels) get only as far as it gets with the one same approach or governance style, and along the way they take up other styles of governance (e.g., [

31]). This already points to an approach to governance that will be discussed in this article: metagovernance or the art to design and manage diversified combinations of governance styles, also denoted as “the governance of governance” [

32] (p. 106).

While it is clear that there will be common goals which are universally applicable, including universal principles such as rule of law, the above leads to the conclusion that the ways to achieve the SDGs need to be differentiated because universal governance recipes alone are not going to work. In order to put this insight to the forefront, it seems useful to introduce for the implementation of the SDGs the guiding principle of “Common But Differentiated Governance” (CBDG). What might be “common” has been itself subject of the OWG and other groups that have elaborated sets of SDGs, alongside with the discussion whether there should be a stand-alone goal on governance, or whether it should be integrated in the individual thematic goals. As a result of this discussion, the SDGs include both types of goals. The agreed governance-related goals and sub-goals hence represent the “common”, which has to be translated in a “differentiated” way when implementing the thematic goals. Within the (proposed) two stand-alone governance-related SDGs 16 and 17, the following Sub-goals are among the most relevant for the institutional, instrumental and procedural aspects of governance (

Table 1).

Table 1.

Examples of governance sub-goals in the SDGs (Open Working Group, July 2014 [

2]).

Table 1.

Examples of governance sub-goals in the SDGs (Open Working Group, July 2014 [2]).

| Goal 16, and herein especially “build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels”: |

| 16.3 | promote the rule of law (…) and ensure equal access to justice for all |

| 16.6 | develop effective, accountable and transparent institutions at all levels |

| 16.7 | ensure responsive, inclusive, participatory and representative decision-making at all levels |

| 16.10 | ensure public access to information (…) |

| Goal 17, on “Means of Implementation”: |

| 17.9 | capacity building (…) |

| 17.14 | enhance policy coherence for SD |

| 17.16 | enhance global partnerships (…) Complemented by multi-stakeholder partnerships (…) |

| 17.17 | encourage (…) Public, public-private and civil society partnerships (…) |

| 17.18 | enhance capacity building (…) to increase the availability of (…) data |

Among the thematic goals 1–15, the sub-goals referring to governance aspects, or financial or other means of implementation (MoI), are indicated by letters a., b. and c. Examples include: Mobilization of resources to implement programs (1.a.), expand capacity-building support for various technologies (6.a.), strengthen the participation of local communities (6.b.), strengthening development planning (11.a.), implementing integrated policies and plans (11.b.), strengthen scientific and technological capacities (12.a.), implement tools to monitor SD impacts (12.b.), and raising capacities for planning and management (13.b.).

Together with the other governance/finance/MoI goals, each country needs to find or further develop its tailor-made way for implementing the SDGs. A SWOT [

33] analysis to take stock of the existing governance framework will be a first essential step. This is not something new: “Taking context as the starting point” is a widely acknowledge principle for addressing international conflict and fragility [

34] (p. 32). The next step is setting up a process that is credible for national actors as well as in a supra-national context is the next step. These steps should include assessing the political and administrative setting with “SD lenses” (the governance of SD),

i.e., identifying the dispositions in terms of governance styles, the direction along which to move and the missing elements to fill in. Developing thematic SD targets for a country should build on a stock-taking of existing goals and targets in sectoral and overarching plans. Monitoring and reporting should be part of the governance design and enable staying on track. In

Section 6, a comprehensive step-by-step approach to CBDG for SDGs will be proposed.

4. CBDG in Practice: A Metagovernance Approach to Design Governance Frameworks

Governance for the SDGs poses the challenge how to combine different governance approaches successfully “on the ground” into tailor-made,

i.e., “differentiated” mixtures that are reflexive and dynamic and at the same contribute to common, universal goals. The challenge is also how to connect the “global” and the “local” levels [

52]. The “State of the Environment 2015” report of the European Environment Agency defines the transition to diversified governance as one of 11 global megatrends that are relevant for environmental sustainability [

53]. Overall, there seems to be convergence around the insight that not one recipe for a specific governance style will bring success, and that sustainable development is a case in point.

4.1. Metagovernance: Definition and Discussion

Section 3 introduced that

metagovernance might be a useful concept to deliver differentiated governance for the SDGs. Its basic idea is that it is possible to develop situationally appropriate combinations of contrasting and even mutually undermining styles of governance. A broad definition is: “Metagovernance is a means by which to produce some degree of coordinated governance, by designing and managing sound combinations of hierarchical, market and network governance, to achieve the best possible outcomes from the viewpoint of those responsible for the performance of public-sector organizations: public managers as ‘metagovernors’” [

21] (p. 68). The need for such a concept was, among others, formulated by Davis and Rhodes [

54] (p. 25) when they argued that “the trick will not be to manage contracts or steer networks but to mix the three systems effectively when they conflict with and undermine one another”. As mentioned in

Section 2, academic literature of the last two decades often mentions three “ideal-typical” governance styles (hierarchy, network, and market) as providing the building blocks of governance frameworks. Indeed, it has been argued that all distinguished governance approaches are combinations of the ideal-types [

21]. Hierarchical governance is often considered “old-style” governance, whereas network and market governance have been referred to as “new modes of governance” [

55].

The three governance styles differ across more than 35 dimensions (see, e.g., [

21], pp. 45–50 and 329–350 for a review of such differences based on extensive literature review). This means that for each of these dimensions, there are in principle three “modes” (or mode combinations) of action. Examples include the roles of government in society (hierarchy: ruler, network: partner, or market: service provider); affinity with problem types (crisis, complex problem, or routine issue); mode of control (authority, trust, or price); strategy type (planning, learning or entrepreneurial); type of relations (dependent, interdependent, or independent); communication modes (informing, having dialogues, or marketing); communicative interaction (telling, arguing, or bargaining); and preferred instruments (legislation, covenant, or contract). At least one of these dimensions is an ethical one: the three styles differ with regard to “relational values”,

i.e., how other people’s values are valued [

22]. Hegemony and separatism are values that can be associated with hierarchical governance, pluralism and tolerance with network governance and indifference with market governance [

44].

Preferences for one of the governance styles (across most of the dimensions) are not uncommon among politicians and policy makers, but also not among academics. This may go back to their academic discipline (e.g., law, economics, business administration, or political science), and may be culturally influenced. Many political scientists in consensus-style democracies like The Netherlands and Denmark, for instance, are advocates of network governance. Arguments in favor of one style are often supported with empirical evidence based on case studies of policy issues for which this governance style indeed may be plausible. For example, cases of crisis governance will usually show that networking is essential but the core is well-designed command and control patterns, whereas in local neighborhood projects with wicked and complex challenges network governance is most likely dominating the mix.

Scholars have argued that metagovernance may imply a return to state-centered governance. Bell and Hindmoor [

56] argue that states have not lost their hierarchical power but adopted also a broader range of government strategies to deal with non-state actors, while remaining in the driving seat. This “state-centric relational approach” enables them to work together with networks and markets while securing governmental influence. The ability of governments to choose a governance style (mixture) has, however, its limitations, for example because of the need to keep sufficient public support [

57]. Whitehead [

58] (p. 13) observed that while metagovernance arrangements may increase steering and accountability of governments, they may at the same time be “choking and constraining the flexibilities” of decentralized networks.

Other scholars maintain the opposite: metagovernance may weaken hierarchy. According to Davies [

59] (p. 4), several influential strands of metagovernance thinking all pay insufficient attention to hierarchy, and especially about what he holds as a central feature of hierarchy, namely coercion.

It is essential to note that metagovernance is not a governance style in itself: it is about combining governance styles into frameworks that deliver. There are basically two approaches to metagovernance: a broader one which seems necessary for SDG implementation at (sub)national level, considering the huge variety of challenges, circumstances, cultures and traditions among countries, and a narrower one. The first is

metagovernance of all governance styles (e.g., [

21,

30]). It has a wider analytical lens and a richer set of “tools” than the second approach,

metagovernance of one single style—usually network governance—as advocated by, e.g., Sørensen and Torfing [

60] for specific situations where networks are prevailing. These two approaches have been named second and first order metagovernance, respectively [

61].

Metagovernance has gained quite some popularity: Between 2004 and 2015, the number of publications per year in which metagovernance was mentioned increased with a factor 6.5; related concepts such as adaptive governance which are close to the metagovernance concept showed an even stronger raise in popularity (factor 50) [

62]. However, the approach is in practice probably more widely applied than these numbers illustrate. A comparison of five case studies on successful public-sector policy projects showed that the responsible managers used it although they had never heard of the term [

21].

4.2. Key Characteristics

Metagovernance is about combining bottom-up and top-down in productive ways; it suggests that seemingly contradictory approaches may be reconciled; it accepts Beck’s “second modernity” (see

Section 3). It aims to make network governance, market governance and hierarchical governance work together in a particular way for a particular situation and allows for different governance at different levels. By mapping the needs and by supporting solutions towards context-specific sustainability, this may contribute to reducing the vagueness of the SD concept and the complexity of its implementation [

63]. It helps managing plurality with the aim to induce more coherence [

64]. It is sensitive to different administrative cultures, and to values, traditions and norms in a country, which could stimulate the emergence of successful governance [

38]. It suggests to abstain from selecting one main governance style

a priori, but to develop instead tailor-made combinations of styles that are determined

after having analyzed the “governance environment”. In states or administrations like the European Commission with a general preference for hierarchical measures (supported by a large percentage of lawyers among their staff), this stimulates to look beyond legislation as the only answer to societal challenges. The European Commission’s First Vice-President Frans Timmermans formulated the need for a different approach as follows:

“I challenge that, if there is a problem, we create a law to solve that problem. I am not sure that the modern and sustainable economy is best served with the premise that for every problem there should be a legal solution. That’s the only thing I challenge. I don’t challenge the goals” [

65]. The Commission’s recent proposal on “Better Regulation” [

66] states that “Better regulation is not about ‘more’ or ‘less’ EU legislation; nor is it about deregulating or deprioritizing certain policy areas or compromising the values that we hold dear: social and environmental protection, and fundamental rights including health—to name just a few examples. Better regulation is about making sure we actually deliver on the ambitious policy goals we have set ourselves”. The “Better Regulation” package (of over 500 pages) includes an extensive “Better Regulation Toolbox” covering four categories of policy instruments: “Hard”, legally binding rules; “soft” regulation; education and information; economic instruments. It remains to be seen how well it will succeed to mix in other than legal tools, while keeping regulations that are important for SD and that work.

For countries with a hierarchical tradition, metagovernance triggers opening up to network and market types of governance instruments, while acknowledging that this would redefine existing power relations. For consensus democracies, it suggests that rules and structure might make consent better implementable, and for market-oriented nations that states need to establish guard rails and that cooperation might help when competition does not do the trick. For a country-specific SDG implementation governments might consider establishing support bodies/networks that help designing, reviewing and evaluating specific governance approaches as well as improving policy coherence: different SDG targets should not undermine each other or counteract within a goal area and between goals. This requires integration so that environment, social and economic aspects come together in each area rather than being treated as separate pillars. A nexus approach might be useful. Examples of such bodies are Sustainable Development Councils mirroring the multi-sector, -level and -actor situation. They have been successful supporters and watchdogs of such processes in a number of countries.

4.3. How Does A “Metagovernor” Know What Is the “Right” Thing to Do?

It may be argued that metagovernance is a technocratic, hyper-rational approach to governance. How can a metagovernor know what is the best solution to a challenge, and doesn’t metagovernance make things unnecessarily complex? An answer to the first question is that he or she does not know what is “right”, because the idea that there are right and wrong answers “out there” is in contrast with the concept itself. The challenge is not about the choice between hierarchical, network and market governance in order to determine the right style, but about choosing the situationally best role for the government, taking into account the characteristics of all three governance styles [

67] (p. 52).

A metagovernor (

i.e., someone who takes up some leadership role in governance analysis, design and/or management; [

21,

68]), therefore tries to take a wider perspective on problem setting, possible solutions, and the choice of institutions, instruments, processes and actor roles than a governance leader who works from a fixed set of assumptions on these topics. This does not mean that metagovernors can be completely “neutral”: we all have our values and believe that they are “right”. Although it therefore seems a difficult job, for some managers this seems to come natural (see the five case studies in [

21]). Whatever they call their approach (metagovernance, common sense) they are all sensitive for situational aspects and are able to put their own preference for a governance style into perspective. They need to be able to think beyond the governance style that is preferential in their national culture and traditions, and beyond a dominant governance style fashion. They will meet resistance—and that is one of the reasons why they may fail: metagovernance failure exists and therefore Jessop [

32] suggests that metagovernors would benefit from having a dose of “self-reflexive irony” (see also

Section 6).

As regards the second question—does not metagovernance add another layer of complexity to governance—the counter argument could be that not applying a metagovernance approach makes things complex. A policy-maker who analyses and designs all governance issues from a network perspective might consider observed hierarchical processes and structures as disturbing “externalities”. Taking the wider metagovernance view implies acknowledging of hierarchy as one of the governance styles, with its own pros and cons, as useful for one’s “governance toolbox”.

4.4. Multi-Level Metagovernance

Implementing the SDGs is a multi-level governance challenge, and the challenges and circumstances are different at all levels. If governance frameworks at one level are not well linked to those on other levels, the result may be total failure. Therefore, it is essential to create multi-level governance frameworks. The European Union has been characterized as such a major supranational instance of multi-level metagovernance governing a wide range of complex and interrelated problems [

69]. However, its practice is not flawless, for example regarding the rather inflexible governance frameworks for its Cohesion Policy funding programs. Fixed frameworks ignore the different realities at different levels of administration. It may well be that at local level network governance works best, while at subnational level setting legal frameworks constitute the main rationale. From other areas there are also examples for the other way around: e.g., city mayors introducing a change in a top-down way—like in the City of London on congestion tax, or in the Brazilian city of Curitiba on public transport, and then such initiatives are supported by incentives (like subsidies) from a higher level. Therefore, the metagovernance rule “there is not a one-size-fits-all solution” also applies to multi-level governance. A recent study in Estonia on empowerment of the local level by the EU’s multi-level Cohesion Policy framework (EU, national, local) also shows that metagovernance is needed at all levels to bring about the desired results. While the policy framework foresees multi-level collaborative governance with co-managing of funds, it turned out that contrary to what was expected, Cohesion Policy had not led to any significant redistribution of policy control. Long-standing power dependencies in the domestic governance system with a hierarchical tradition have remained characteristic [

70].

While this article focuses on the governance for implementing the SDGs at sub-global levels, its recommendations are also valid for the overall architecture of a multi-level and—tiered review process, including peer reviews, as currently being discussed (see e.g., comprehensive proposal by Beisheim [

71]) and to be decided in September 2015. This also includes considerations for the future role of the UN High Level Political Forum for Sustainable Development (HLPF) [

72].

4.5. Metagovernance and Systemic Change

It is contested in how far the SDGs will trigger deep systemic changes, with some considering the Pope’s 2015 encyclical as a stronger call [

73]. Clearly weak seems the unquestioned (and not differentiated) SDG for economic growth. Systemic changes would entail, for example, measuring economic and societal progress beyond GDP and the transition from fossil to renewable energy. Preliminary analysis of the Dutch Environmental Assessment Agency PBL concludes that some goals can indeed only be achieved in the Netherlands with fundamental changes in policy and approach [

74]. Other goals and targets will be achievable with incremental change within existing systemic conditions and paradigms. In general, the “easier” roads towards sustainability are about optimizing existing pathways, and innovative solutions within such frameworks are important, because not all existing (sub)systems are unsustainable.

In terms of governance styles, systemic transitions often require hierarchical interventions. Recent examples are the German energy transition (“Energiewende”) initiated by the German Chancellor in 2011 and the Clean Power Plan as proposed by the President of the USA in August 2015. The “Energiewende” process has featured some metagovernance elements: It started with a government initiative establishing a dedicated Commission, which organized stakeholder and citizens’ consultations. The Commission’s conclusions were adopted by the German government with legal provisions and an action program, and the subsequent phases saw ample investment in creating public support.

The Netherlands pioneered in making systemic change the core of their environmental governance in the 4th National Environmental Policy Plan (NEP) of 2001 [

19] (p. 524), with some successes in tackled subsystems (e.g., greenhouse horticulture changed from high energy consumption to energy neutrality or net energy production; water management changed its paradigm from fighting

against water (building higher dikes) towards working

with water, which has resulted in a complete reorientation of investments in the water sector). Government incentives resulted in a new research focus and innovation in practice. Typical for the Netherlands’ history of network governance, these transitions were not driven by legislation. The weak use of hierarchical governance is likely one of the reasons why the energy transition towards renewables, which was also part of the 4th NEP in 2001, has still not materialized. Together with the struggles of the German “Energiewende” after passing dedicated pieces of legislation, it points to the challenges in energy politics, characterized by powerful vested interests (see also the short discussion on the energy SDG in

Section 5).

In any case, systemic changes require out-of-the-box thinking for which a metagovernance approach could be useful. This also applies to the easier roads of optimizing pathways within existing systems.

4.6. Metagovernance in the Private Sector

Metagovernance shares a multi-actor view with the “beyond cockpit” approach proposed by Hajer

et al. [

40]: governments and intergovernmental organizations, and businesses, cities and civil society need to play their role. This role may be cooperation, but also self-governance, co-decision, or, at the other end of the spectrum, being a sounding board for top-down policy, depending on the situation. One main difference is that Hajer

et al. combine desired governance characteristics with policy principles, in particular planetary boundaries, safe and just operating space, the energetic society and green competition, which they consider as prerequisites.

Metagovernance is not a government-only approach and hence business actors or civil society organizations might also take this multi-perspective approach; in every organization there may be “metagovernors” [

44]. Derkx and Glasbergen [

64] have shown how ambitious companies used a metagovernance approach in setting voluntary product standards, in an attempt to improve the existing networking. Interestingly, the outcome of the cases studied was not the lowest common denominator, but very strict reference standards. The approach had a strong trust-building dimension with positive effects on future collaborations. For those involved in public (meta)governance to implement the SDGs it would be recommendable to establish linkages with such front-running companies and to further stimulate this type of capacity building among all stakeholders. This might, for example, facilitate public–private partnership building.

4.7. Costs of Governance Failures and Benefits of Metagovernance

Institutions “entrusted with creating a sustainable future cannot afford to have a weak governance structure” [

72] (p.14). “Cannot afford” on the one hand has a normative, ethical dimension (we cannot afford failure because of our responsibility for next generations). On the other hand, there is a relevant financial dimension. It seems plausible that applying metagovernance requires somewhat more human resources than applying a standard or simplified governance framework, but the return on investment in terms of cost-savings may be huge. A metagovernance-inspired framework does not reject any measures up-front, for example. Therefore, measures can be selected that are close enough to existing values and traditions and different enough to bring about change, which seems a good predictor of broad acceptance of measures as well as prevention of costs caused by resistance and legal procedures. Such a framework implies built-in reflections also about long-term impacts. The long-term benefits of preventing lock-ins in unsustainable technological investments may be enormous. The reflexive governance attitude also promotes awareness of the costs of non-action in case scientific evidence is abundant [

75]. To conclude: differentiated and “mindful” governance frameworks can let the SDGs offer good value for money. Moreover, one could imagine that when developing countries deliver substantially on the SDGs, this could have a positive impact on the political debates on development aid in donor countries. A classical problem that could be addressed at the political level is the distributional effect: the costs of appropriate governance are usually on the government side (“taxpayers’ money”), while the costs of governance failure are economic, social and/or environmental.

4.8. Applicability and Strategies

There are different fields of application of metagovernance:

analyzing an existing situation, and

designing and

managing new governance frameworks. The use of an analytical metagovernance lens resulted in the UNDP/UNEP Poverty and Environment Initiative Program in Tajikistan in better understanding particular governance failures, and generated suggestions for policy change, for example [

76]. It also made clear why cases of policy preparation for soil protection in England, The Netherlands and Germany used quite different governance tools [

21]. The same case study research concluded that public managers of successful policy programs used three metagovernance strategies during design and management of policies:

Combining different governance approaches into arrangements of institutions, instruments, processes and actor constellations which are compatible enough with existing values and traditions to be accepted and at the same time different enough to push/pull/nudge towards change;

Switching from one to another dominant governance style, for example when a complex and contested topic for which a network approach was designed turns into a disaster and suddenly command and control (hierarchy) is needed; and

Maintenance of a chosen approach by, for example, protecting it against perverse/undermining influences in the governance environment. Maintenance complements the combining and switching strategies.

5. Building Governance Frameworks for Selected SDGs

The following examples illustrate how elements from different governance “families” might be mindfully mingled into tailored approaches for some of the governance-related SDG targets (proposed version of July 2014) [

2]. We only present possibilities, no prescriptions. The essence of metagovernance is the perspective that there is no one-size-fits-all to governance, and therefore a detailed prescription is impossible: the proof of the pudding is in the eating. The first five targets relate to the “stand-alone” governance Goals 16 and 17; subsequently we take energy as example of a thematic SDG.

5.1. Accountability (Goal 16.6)

Lack of accountability hampers any serious efforts in international environmental governance [

77] and this also applies to the broader SD governance agenda. The point is that each governance style has weaknesses on accountability, but they are different. In a low-trust hierarchical context, transparency may be considered as a threat, as it may lead to exposure of failures. In a network context it may be impossible to single out who is to be held accountable for failures: how to hold actors into account for outcomes that are a result of collaboration of various actors collaborating in opaque processes [

78]? In a market approach, accountability mechanisms may risk focusing too much on price over quality. A metagovernance approach would consider such weaknesses and suggest building institutions that are able to tackle all of these. Dedicated bodies/networks could help preventing or mitigating governance failures. While governments are likely to take the leading role, also other actors might do. Where feasible in the national context, it is recommended to include civil society, business as well as research bodies as partners. In a number of countries, national/sub-national Sustainable Development Councils or Commissions have taken up a monitoring role, which enables them to hold governments to account for progress. Accountability is the flipside of responsibility. Where responsibility is going to be shared between state and non-state actors, accountability rules and procedures may need to be adjusted to cover the whole picture.

5.2. Rule of Law and Access to Justice (Goal 16.3)

Rule of law and access to justice are principles that require a certain quality of hierarchical governance. Its instruments include regulation, standards, and sanctions to ensure that individuals, companies and also administrations can be held accountable, e.g., for damaging common goods. A powerful example is the recent ruling of a Dutch court, ordering the state to reduce CO

2 emissions by 25% within five years to protect its citizens from climate change in the world’s first climate liability suit [

79]. A metagovernance view on SD-relevant law enforcement could lead to choices about who is involved (

i.e., elements of network governance: see for example the trend to involve citizens and NGOs in data collection on environmental crimes). In addition, market governance thinking would make sanctions more costly than the profits of trespassing. There is also experience that voluntary agreements (network governance) work better when a regulatory “stick” is standing in the corner. Ways to achieve justice outside of courts are alternative conflict resolution mechanisms like mediation and mutual gains approach. They are typically cheaper and faster than court cases, and often come up with better solutions and/or identify “win-win” (“mutual gains” [

80]). Conflict resolution could, for example, result in broadening the negotiation agendas (portfolio approaches rather than single instrument approaches, see [

81].

5.3. Partnerships (Goal 17.16, 17.17)

Partnerships are a soft form of institutions in terms of their structural and juridical dimension, but can be very powerful. They are therefore a valuable component in the SDG set, and are seen central in the vision of the European Commission [

82]. Building partnerships is a mechanism typical for network governance. It helps crossing all sorts of boundaries (administrative, legislative, geographical, and cultural) when solving SD problems requires this, while at the same time it may leave existing (formal) institutions in place. It is a good example of the “and-and” approach. On substance, partnerships are hotbeds of innovative solutions, as they are based on trust among parties with contrasting interests and ideas. In the EU, the Covenant of Mayors on climate change has become an influential partnership. The practice of twinning between administrative entities for capacity building and training is a successful example for partnerships between existing EU members and accession countries.

Similarly, countries could team up across the globe and set up peer processes on SDG implementation, to learn from each other and eventually organize peer reviews of progress. This might take the form of expert type of peer reviews, as practiced between OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries, or more stakeholder-based peer reviews, as some countries with a functioning SD strategy have performed, like The Netherlands [

83] and Germany [

84]. In both cases a (independent) national SD Council coordinated the peer review process. Depending on the organizational set-up this could include “external” (

i.e., non-governmental) peers.

To overcome potential weaknesses of partnerships such as unclear democratic legitimation, opaqueness and inefficiency, a metagovernance approach would add, for example, from hierarchical governance rules on accountability, in- or exclusion of participants and transparency, and from market governance measures to promote cost-effectiveness and efficiency. There are also various lighter versions of partnerships in terms of (formal) commitment, like alliances, coalitions and (internet) communities.

5.4. Participation (Goal 16.7)

Participation is a central theme in many SDG governance proposals, but not all participation is supportive to achieving (SDG) goals. A metagovernance approach helps reducing typical participation “potholes” such as dominance of one group over others, never-ending discussions, lack of accountability and lack of ownership. Solutions could include being highly transparent about roles, rights and responsibilities of participants and managing of expectations (e.g., does the respective participation entail information, collaboration or co-decision?), having procedures in place to balance vocal minorities and silent majorities, setting rules for inclusion and exclusion of actors, as well as organizing how to codify agreement (e.g., the “Green Deals” in The Netherlands: a series of covenants between government and market parties [

85] (p. 5)). In a rather strongly hierarchically steered country, experimenting with co-decision might not be a realistic starting point but it might work to gradually step up on the “participation ladder” while building capacity and trust, as experience of the UNEP-UNDP Poverty and Environment Programme has shown in a number of developing countries. Participation can be strengthened by adding elements of competition (

i.e., market governance) in the governance mix, for example by introducing awards. In the European Union, the annual Green Capital Award has proven to be a huge incentive for not only the winners but also the other finalists, and their commitment is being kept high with the establishment of an EU network of finalists and winners.

5.5. Capacity Building (Goal 17.18)

Capacity building is about creating the framework conditions for what needs to be done. In the proposed SDGs several Sub-goals refer to capacity building, be it in governmental organizations at all levels, in civil society or the business sector. There is, for example, no participation without the capacity of the participants to engage in providing solutions and of governments to engage with other actors. The CBDG principle and the metagovernance lens could result in better tailored training, skills development and capability of all relevant actors to support the implementation of the SDGs.

Where capacity building is directed at increasing empowerment and ownership “on the ground”, at local level, a metagovernance lens points at possible resistance at central level. Hierarchical policy makers might need to be convinced, and training programs might be useful to this end, that losing some direct steering power does not necessarily imply losing leadership: “to give up dominance at the personal level, putting respect in place of superiority, becoming a convener, and provider of occasions, a facilitator and catalyst, a consultant and supporter” (…) brings “many satisfactions and non-material rewards” [

86] (p. 14).

5.6. Energy Policy (Goal 7)

As explained above, also the thematic SDGs have governance-related targets (listed by letters a.–c. under the respective Goals). For the energy Goal the governance-related targets are: (7.a) enhance international cooperation and (7.b) expand infrastructure and upgrade technology. Experience with energy policy shows that it is a case where a metagovernance approach would be particularly useful, to achieve the necessary differentiation. Nilsson

et al. [

87] (p. 4144) state that SDG energy development priorities may range from ensuring universal access to energy services and securing economic growth potential (e.g., low-income countries) to decoupling growth from energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions (middle-income and emerging economies) or decarbonizing energy sectors and reaching new levels of efficiency performance (high-income countries).

As regards Goal 7.1 on universal access to energy, it is probably relevant that energy production in many countries has turned from (local) public service to private enterprises, followed by scaling up into huge and powerful power companies, which are almost monopolies. As a counter reaction, and in order to speed up the transition to renewable energy, local initiatives have fought to decentralize energy production and making renewable energy again part of the “commons”. What can be observed in some countries is a governance transition from state/local via market steering (followed by market failures), back to local network initiatives steered and owned by local authorities and/or citizens. In other countries, energy production has been privatized to monopolist firms from the onset.

This is of course a simplification of a very complex policy arena with strong vested interests and power play. A metagovernance view on energy policy could address the potential benefits and costs of each of these approaches instead of letting one (exclusively) dominate. Indeed, sustainable energy programs in Croatia and Mongolia, where market, network and hierarchical mechanisms were combined, have been analyzed as successful [

63].

7. Summary and Outlook

7.1. Establish “Common But Differentiated Governance” as Guiding Principle

The SDGs are universally applicable and will therefore be implemented by all states, combined with roles for the regional and subnational level. To give some steer to this complex challenge, this article recommends introducing a general guiding principle for the implementation of the SDGs—the principle of “Common But Differentiated Governance” (CBDG). CBDG would ensure good linkage between the “common” Goals and “differentiated” implementation, with the latter taking into account different national realities, capacities and levels of development and respecting national policies and priorities. Applying the “common but differentiated” thinking to governance might also help overcoming the dichotomy between developed and developing countries that has evolved as connotation for CBDR (“Common But Differentiated Responsibilities”).

7.2. Take World Views, Values and Traditions into Account

SDG implementation and the governance thereof is not a technical exercise, run by “value-neutral” experts. Not only politicians and policy makers, but also academics may advocate one governance style above others, which might even come with an engrained conviction. It is therefore important to understand the worldviews, values and traditions of those who are involved in or would gain or lose from SDG implementation. Underlying values that are drivers for certain solutions and may block other solutions should be made explicit. For the SDGs, governance frameworks are needed, and they need to be transparent about their normative assumptions with regard to problem-definition and problem-solving. This may result in “exposing” hidden preferences or long-standing assumptions about how certain issues should be tackled, which could lead to heated debates. However, without such “reality checks”, failures such as getting locked-in in unsustainable technologies may make SDG implementation also financially unsustainable.

7.3. Use Metagovernance to “Engineer” CBDG

Metagovernance is proposed as concept for developing governance frameworks for implementation of the SDGs, because this approach for designing and managing governance frameworks explicitly takes into account different challenges, realities and capacities. Looking with a metagovernance bird’s eye perspective at processes of development cooperation and sustainable development, shifts in preferences for governance styles can already be recognized. However, these have been sequential shifts over time, typically each accompanied and followed by reflections on the pros and cons of the respective approach, often looking for the Holy Grail, and ended in some convergence (“and” instead of “or”). The point of metagovernance is (a) the recognition of the strength and weaknesses of each style; (b) taking this into account from the onset in the process of (c) mindfully combining ideas and arrangements from different approaches. It is grounded in existing cultures and traditions, but facilitates a transformative agenda. This approach also suggests that copying standardized recipes (“best practices”) could result in governance failure, whereas learning from each other (and considering translating successful practices from elsewhere) could lead to success.

7.4. Apply Key Governance Principles

To support transitions towards SD, reflexivity, flexibility and long-term thinking need to be applied as governance principles, and the multi-sector, multi-level and multi-actor situations of each specific case are to be considered. On each relevant administrative or geographical level, governance design should begin with stock-taking of the governance environment, taking into account the specificities of each nation/region/city, i.e., analyzing the existing governance arrangements including what has worked historically and where are the gaps and obstacles. Trying to force a “purist” form of network governance might weaken itself in cases where the hierarchical segment of the governance system is in principle willing to constructively engage on an issue. Governments need to work on improving horizontal coordination (between government departments) and vertical coordination (the linkages between vertical levels), as well as on improving communication with citizens and invigorating understanding, ownership and engagement.

7.5. Metagovernance Is Not a Return to State-Centered Governance

While some convergence towards diversity in the academic debate on governance can be observed, there are also scholars who promote that SDG governance should build on network and market governance, and for whom metagovernance implies a return to undesired state-centered governance. Using the metagovernance concept to combine different governance styles into successful SDG governance frameworks implies to be open to a possibly strong role of the state. However, metagovernance as defined in this article is not pro-state—just as it is not anti-state either.

7.6. Step-by-Step Approach

A simple step-by-step approach may guide metagovernance and CBDG for the SDGs, starting with mapping the governance environment, conducting a SWOT analysis and defining the challenges, defining policy options and on this basis designing a governance framework, with provisions to “manage” it in the course of time, and ending with a review.

7.7. Establish Support Bodies, Partnerships and Peer Review Processes

It is recommendable to establish support bodies/networks that help designing, reviewing and evaluating the governance frameworks for SDG implementation. Such bodies are also meant to take an integrated view of environmental, social and economic aspects, and with that also support policy coherence. Sustainable Development Councils mirroring the multi-sector, -level and -actor situation have been successful supporters and watchdogs of transition processes in a number of countries.

Governments could also team up with others in partnerships for the SDG implementation across all the steps introduced, and set up peer review processes on SDG implementation. This might take the form of expert type of peer reviews, as practiced between OECD countries, or more stakeholder-based peer reviews, as some countries with a functioning SD strategy have performed, like The Netherlands and Germany. In both these cases a (independent) national SD Council coordinated the peer review process.

7.8. Costs of Governance Failures and Benefits of CBDG

Differentiated and “mindful” governance frameworks may let the SDGs offer good value for money. Applying metagovernance requires somewhat more human resources than standard or simplified governance, but the return on investment in terms of cost-savings may be huge. As a metagovernance-inspired framework does not reject any measures up-front, it is possible to select measures that are broadly accepted, which prevents costs caused by resistance and legal procedures. Such a framework implies built-in reflections also about long-term impacts. The long-term benefits of preventing lock-ins in unsustainable technological investments may be enormous. In the case of development cooperation, it is instrumental that taking such a direction is supported by donor countries.

All in all, it seems worthwhile to introduce CBDG as guiding principle for the implementation of the universal Post-2015 SDGs. Developing situationally appropriate and overall cost-effective governance frameworks is no rocket science, and a metagovernance approach may be quite helpful in preventing and mitigating typical governance failures. Furthermore, yes, metagovernance failures also exist (Jessop), but this is not a reason not to engage.

7.9. CBDG in the Future UN Multi-Level Review Process

This article focuses on the governance for implementing the SDGs on sub-global levels, and therefore rather on the “differentiated” than on the “common” part. It supports the national (and potentially the regional, sub-national and local) level in designing an appropriate metagovernance framework, which might inspire and feed into the designing of the future UN multi-level review process as complex challenge currently underway. The review of the governance framework, as part of Means of Implementation, should in any case be included in the future review cycles for the SDG implementation. SDG (meta)governance should be developed, managed and maintained at all levels of administration, because institutions “entrusted with creating a sustainable future cannot afford to have a weak governance structure” [

72] (p. 14)—that is, if the ambition is really to implement the SDGs within this generation.