Perspectives on Cultural and Sustainable Rural Tourism in a Smart Region: The Case Study of Marmilla in Sardinia (Italy)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Sustainable Rural Tourism in Italy: Some Reference Data

| Typologies of agritourism farms | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | Difference 2003–2013 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute Number (Abs.) | % | ||||||||||||

| Accommodation | |||||||||||||

| - Firms | 10,767 | 11,575 | 12,593 | 13,854 | 14,822 | 15,334 | 15,681 | 16,504 | 16,759 | 16,906 | 17,102 | 6335 | 58.8 |

| - Number of beds | 130,195 | 140,685 | 150,856 | 167,087 | 179,985 | 189,013 | 193,480 | 206,145 | 210,747 | 217,946 | 224,933 | 94,738 | 72.8 |

| - Picnic areas | 4540 | 5386 | 5826 | 6935 | 7055 | 7320 | 7785 | 8759 | 9113 | 8363 | 8180 | 3640 | 80.2 |

| Food & beverage | |||||||||||||

| - Firms | 6193 | 6833 | 7201 | 7898 | 8516 | 8928 | 9335 | 9914 | 10,033 | 10,144 | 10,514 | 4321 | 69.8 |

| - Seating capacity | 249,342 | 266,654 | 277,866 | 298,003 | 322,145 | 337,385 | 365,943 | 385,470 | 385,075 | 397,175 | 406,957 | 157,615 | 63.2 |

| Tasting | |||||||||||||

| - Firms | 2426 | 2737 | 2542 | 2664 | 3224 | 3304 | 3400 | 3836 | 3876 | 3449 | 3588 | 1162 | 47.9 |

| Other Activities | |||||||||||||

| - Firms | 7436 | 8240 | 8755 | 9643 | 9715 | 10,354 | 10,583 | 11,421 | 11,785 | 11,982 | 12,096 | 4660 | 62.7 |

| of which | |||||||||||||

| - Horse Riding | 1364 | 1494 | 1478 | 1557 | 1559 | 1615 | 1548 | 1638 | 1662 | 1489 | 1230 | −134 | -9.8 |

| - Escursionism | 2452 | 2692 | 2981 | 3131 | 2879 | 3140 | 3071 | 3190 | 3233 | 3324 | 3124 | 672 | 27.4 |

| - Naturalistic Obs. | 224 | 265 | 575 | 517 | 558 | 607 | 623 | 784 | 891 | 932 | 972 | 748 | 333.9 |

| - Trekking | 1350 | 1463 | 1426 | 1465 | 1629 | 1657 | 1674 | 1950 | 1949 | 1821 | 1717 | 367 | 27.2 |

| - Mountain Bike | 2101 | 2422 | 2258 | 2311 | 2347 | 2398 | 2309 | 2800 | 2794 | 2785 | 2851 | 750 | 35.7 |

| - Educational Farms | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 752 | 1122 | 1251 | 1176 | 1176 | - |

| - Courses | 693 | 812 | 942 | 1025 | 1256 | 1407 | 974 | 1967 | 1878 | 2009 | 1770 | 1077 | 155.4 |

| - Sports | 2927 | 3006 | 3474 | 3682 | 3758 | 4203 | 4168 | 4152 | 4141 | 5058 | 5088 | 2161 | 73.8 |

| - Various | 3786 | 4003 | 4288 | 5043 | 5395 | 5616 | 5994 | 6312 | 6737 | 4917 | 6033 | 2247 | 59.4 |

| Agritourism Farms | |||||||||||||

| - Total Firms | 13,019 | 14,017 | 15,327 | 16,765 | 17,720 | 18,480 | 19,019 | 19,973 | 20,413 | 20,474 | 20,897 | 7878 | 60.5 |

| Regions Geographical distributions | Food & beverages | Tasting | Other Activities | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 2013 | Difference | 2012 | 2013 | Difference | 2012 | 2013 | Difference | ||||

| Abs. | % | Abs. | % | Abs. | % | |||||||

| Piedmont | 753 | 790 | 37 | 4.9 | 589 | 616 | 27 | 4.6 | 902 | 925 | 23 | 2.5 |

| Aosta Valley | 45 | 36 | −9 | −20.0 | 35 | 9 | −26 | −74.3 | 10 | 9 | −1 | −10.0 |

| Lombardy | 1019 | 1060 | 41 | 4.0 | 116 | 144 | 28 | 24.1 | 673 | 722 | 49 | 7.3 |

| Trentino-Alto Adige | 577 | 625 | 48 | 8.3 | 100 | 108 | 8 | 8.0 | 1311 | 1348 | 37 | 2.8 |

| Bolzano-Bozen | 430 | 470 | 40 | 9.3 | - | - | - | - | 1255 | 1,292 | 37 | 2.9 |

| Trento | 147 | 155 | 8 | 5.4 | 100 | 108 | 8 | 8.0 | 56 | 56 | - | - |

| Veneto | 756 | 782 | 26 | 3.4 | 601 | 641 | 40 | 6.7 | 511 | 524 | 13 | 2.5 |

| Friuli-Venezia Giulia | 447 | 454 | 7 | 1.6 | 10 | 13 | 3 | 30.0 | 229 | 240 | 11 | 4.8 |

| Liguria | 281 | 353 | 72 | 25.6 | - | 40 | 40 | - | 336 | 287 | −49 | −14.6 |

| Emilia-Romagna | 797 | 834 | 37 | 4.6 | - | - | - | - | 874 | 739 | −135 | −15.4 |

| Tuscany | 1131 | 1232 | 101 | 8.9 | 577 | 515 | −62 | −10.7 | 2925 | 3141 | 216 | 7.4 |

| Umbria | 405 | 409 | 4 | 1.0 | 227 | 237 | 10 | 4.4 | 1108 | 1120 | 12 | 1.1 |

| Marche | 414 | 447 | 33 | 8.0 | 380 | 420 | 40 | 10.5 | 306 | 234 | −72 | −23.5 |

| Lazio | 551 | 596 | 45 | 8.2 | 133 | 162 | 29 | 21.8 | 552 | 571 | 19 | 3.4 |

| Abruzzo | 436 | 410 | −26 | −6.0 | 73 | 56 | −17 | −23.3 | 467 | 377 | −90 | −19.3 |

| Molise | 86 | 86 | - | - | 50 | 50 | - | - | 54 | 54 | - | - |

| Campania | 352 | 396 | 44 | 12.5 | 136 | 151 | 15 | 11.0 | 287 | 330 | 43 | 15.0 |

| Puglia | 271 | 222 | −49 | −18.1 | 146 | 138 | −8 | −5.5 | 231 | 303 | 72 | 31.2 |

| Basilicata | 98 | 78 | −20 | −20.4 | 40 | 20 | −20 | −50.0 | 104 | 54 | −50 | −48.1 |

| Calabria | 569 | 542 | −27 | −4.7 | 50 | 49 | −1 | −2.0 | 503 | 472 | −31 | −6.2 |

| Sicily | 473 | 493 | 20 | 4.2 | 186 | 219 | 33 | 17.7 | 514 | 550 | 36 | 7.0 |

| Sardinia | 683 | 669 | −14 | −2.0 | - | - | - | - | 85 | 96 | 11 | 12.9 |

| ITALY | 10,144 | 10,514 | 370 | 3.6 | 3449 | 3588 | 139 | 4.0 | 11,982 | 12,096 | 114 | 1.0 |

| Northern Italy | 4675 | 4934 | 307 | 6.6 | 1451 | 1571 | 128 | 8.8 | 4846 | 4794 | −15 | −0.3 |

| Central Italy | 2501 | 2684 | 183 | 7.3 | 1317 | 1334 | 17 | 1.3 | 4891 | 5066 | 175 | 3.6 |

| Mezzogiorno | 2968 | 2896 | −27 | −0.9 | 681 | 683 | 31 | 4.6 | 2245 | 2236 | 10 | 0.4 |

| South Italy | 1812 | 1734 | −78 | −4.3 | 495 | 464 | −31 | −6.3 | 1646 | 1590 | −56 | −3.4 |

| Islands | 1156 | 1162 | 6 | 0.5 | 186 | 219 | 33 | 17.7 | 599 | 646 | 47 | 7.8 |

| Regions Geographical distributions | 2012 | 2013 | Difference | Regions Geographical distributions | 2012 | 2013 | Difference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abs. | % | Abs. | % | ||||||

| Piedmont | 1164 | 1220 | 56 | 4.8 | Umbria | 1262 | 1280 | 18 | 1.4 |

| Aosta Valley | 54 | 53 | −1 | −1.9 | Marche | 788 | 880 | 92 | 11.7 |

| Lombardy | 1415 | 1521 | 106 | 7.5 | Lazio | 841 | 884 | 43 | 5.1 |

| Trentino-Alto Adige | 3391 | 3506 | 115 | 3.4 | Abruzzo | 774 | 653 | −121 | −15.6 |

| Bolzano-Bozen | 2996 | 3098 | 102 | 3.4 | Molise | 104 | 104 | - | - |

| Trento | 395 | 408 | 13 | 3.3 | Campania | 407 | 458 | 51 | 12.5 |

| Veneto | 1376 | 1449 | 73 | 5.3 | Puglia | 355 | 353 | −2 | −0.6 |

| Friuli-Venezia Giulia | 588 | 614 | 26 | 4.4 | Basilicata | 145 | 112 | −33 | −22.8 |

| Liguria | 543 | 567 | 24 | 4.4 | Calabria | 610 | 577 | −33 | −5.4 |

| Emilia-Romagna | 1036 | 1106 | 70 | 6.8 | Sicily | 602 | 633 | 31 | 5.1 |

| Tuscany | 4185 | 4108 | −77 | −1.8 | Sardinia | 834 | 819 | −15 | −1.8 |

| ITALY | 20,474 | 20,897 | 423 | 2.1 | Mezzogiorno | 3831 | 3709 | −79 | −2.1 |

| Northern Italy | 9567 | 10,036 | 584 | 6.1 | South Italy | 2395 | 2257 | −138 | −5.8 |

| Central Italy | 7076 | 7152 | 76 | 1.1 | Islands | 1436 | 1452 | 16 | 1.1 |

3. Governance and Management of Marmilla’s Place-Based Heritage from a Sustainability Perspective

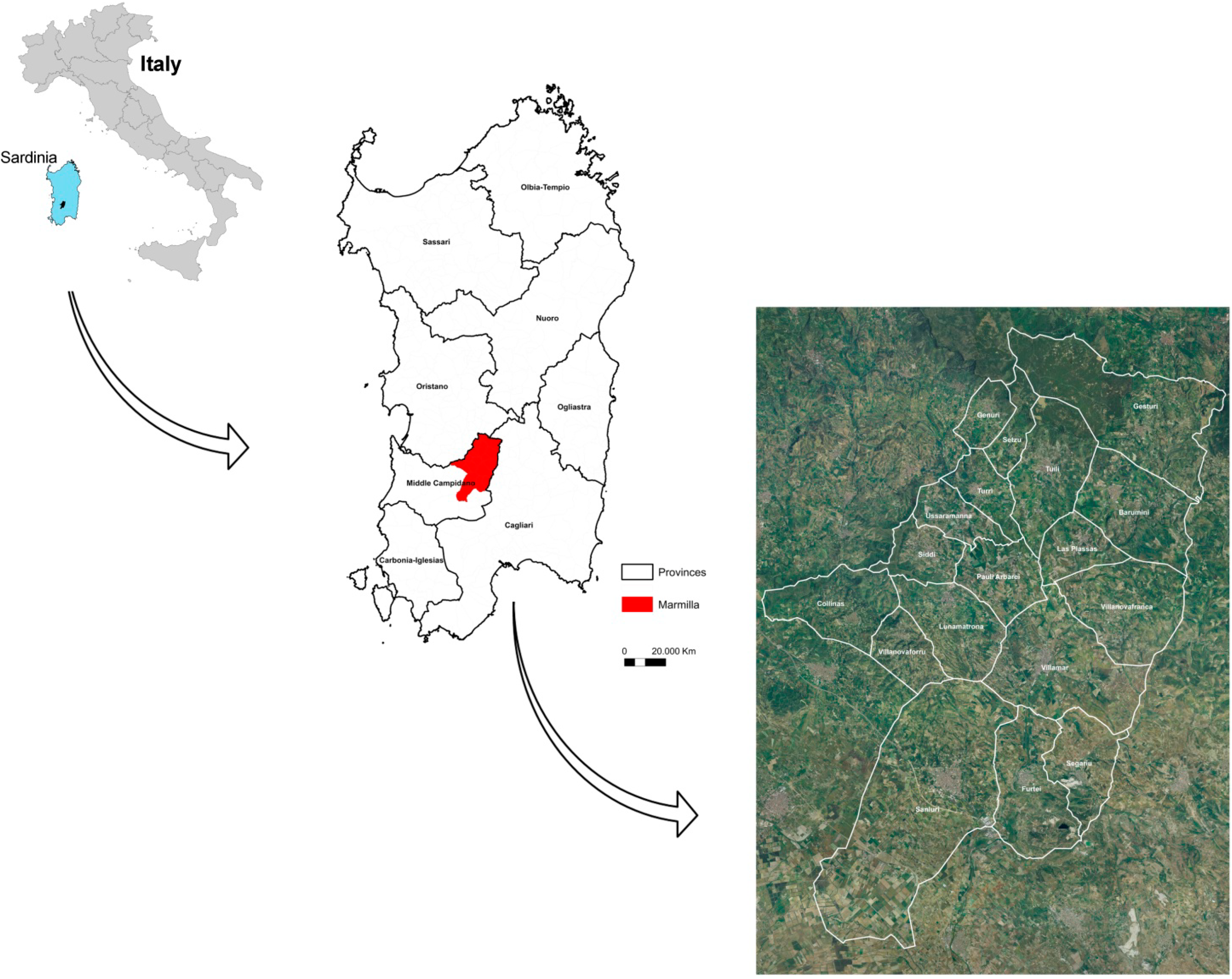

3.1. Case Study of Marmilla

| Geographical distributions | Area (km square) | Population density (2014) | Population 2014 (inhabitants) | Aging index 2014 | Disposable Income Per capita 2013 (Income—Taxes [fiscal levy]) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barumini | 26.57 | 48.78 | 1296 | 261.4 | € 11,986.00 |

| Collinas | 20.79 | 41.41 | 861 | 292.9 | € 12,507.00 |

| Furtei | 26.12 | 64.20 | 1677 | 204.8 | € 11,117.00 |

| Genuri | 7.55 | 45.03 | 340 | 463.6 | € 12,855.00 |

| Gesturi | 46.87 | 27.29 | 1279 | 319.4 | € 10,596.00 |

| Las Plassas | 11.14 | 22.08 | 246 | 255.6 | € 10,596.00 |

| Lunamatrona | 20.57 | 85.03 | 1749 | 277.7 | € 13,028.00 |

| Pauli Arbarei | 15.12 | 42.72 | 646 | 247.7 | € 11,465.00 |

| Sanluri | 83.78 | 101.81 | 8530 | 174.5 | € 14,418.00 |

| Segariu | 16.69 | 74.18 | 1238 | 206.9 | € 10,596.00 |

| Setzu | 7.82 | 19.31 | 151 | 273.7 | € 14,071.00 |

| Siddi | 11.02 | 61.43 | 677 | 321.2 | € 11,291.00 |

| Tuili | 24.5 | 42.86 | 1050 | 375.5 | € 11,986.00 |

| Turri | 9.64 | 46.37 | 447 | 442.1 | € 11,986.00 |

| Ussaramanna | 9.75 | 57.23 | 558 | 305.0 | € 13,376.00 |

| Villamar | 38.64 | 72.93 | 2818 | 174.0 | € 11,465.00 |

| Villanovaforru | 10.97 | 59.16 | 649 | 272.3 | € 11,986.00 |

| Villanovafranca | 27.46 | 51.24 | 1407 | 283.1 | € 10,944.00 |

| Marmilla | 415 | 61.73 | 25,619 | 226.5 | € 12,014.94 |

| Sardinia | 24,090 | 69.07 | 1,663,859 | 174.4 | € 13,871.00 |

| Italy | 301,338 | 201.71 | 60,782,668 | 154.1 | € 17,038.20 |

| Geographical distributions | 1861 | 1871 | 1881 | 1901 | 1911 | 1921 | 1931 | 1936 | 1951 | 1961 | 1971 | 1981 | 1991 | 2001 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barumini | 1214 | 1187 | 1221 | 1118 | 1179 | 1335 | 1445 | 1431 | 1685 | 1729 | 1647 | 1516 | 1423 | 1413 | 1310 |

| Collinas | 976 | 1012 | 1072 | 1033 | 1088 | 1065 | 1040 | 1091 | 1206 | 1213 | 1129 | 1145 | 1076 | 1014 | 885 |

| Furtei | 1030 | 915 | 981 | 1057 | 1118 | 1179 | 1280 | 1422 | 1728 | 1846 | 1788 | 1830 | 1729 | 1723 | 1674 |

| Genuri | 359 | 400 | 434 | 383 | 440 | 446 | 535 | 575 | 654 | 706 | 567 | 518 | 444 | 386 | 345 |

| Gesturi | 1660 | 1457 | 1430 | 1431 | 1507 | 1455 | 1643 | 1709 | 1827 | 1801 | 1567 | 1515 | 1438 | 1430 | 1280 |

| Las Plassas | 486 | 459 | 429 | 397 | 454 | 500 | 587 | 502 | 566 | 632 | 379 | 298 | 291 | 269 | 257 |

| Lunamatrona | 968 | 1018 | 1104 | 1148 | 1299 | 1278 | 1467 | 1640 | 1948 | 2017 | 1850 | 1896 | 1896 | 1858 | 1783 |

| Pauli Arbarei | 433 | 424 | 409 | 401 | 477 | 530 | 656 | 676 | 801 | 797 | 787 | 778 | 692 | 720 | 651 |

| Sanluri | 4199 | 4177 | 4177 | 4403 | 4593 | 4786 | 5449 | 5721 | 7555 | 7595 | 7402 | 8305 | 7912 | 8519 | 8460 |

| Segariu | 700 | 588 | 647 | 661 | 732 | 750 | 899 | 989 | 1308 | 1441 | 1409 | 1432 | 1320 | 1358 | 1277 |

| Setzu | 302 | 330 | 276 | 240 | 292 | 267 | 304 | 325 | 278 | 278 | 223 | 223 | 184 | 166 | 144 |

| Siddi | 608 | 615 | 603 | 636 | 631 | 802 | 869 | 871 | 987 | 1121 | 990 | 903 | 869 | 799 | 696 |

| Tuili | 1334 | 1286 | 1242 | 1320 | 1330 | 1302 | 1478 | 1613 | 1713 | 1591 | 1348 | 1347 | 1263 | 1185 | 1062 |

| Turri | 454 | 488 | 511 | 503 | 490 | 487 | 575 | 602 | 729 | 734 | 633 | 597 | 572 | 533 | 442 |

| Ussaramanna | 623 | 640 | 609 | 586 | 677 | 730 | 790 | 863 | 920 | 963 | 835 | 714 | 656 | 611 | 556 |

| Villamar | 1948 | 1825 | 1903 | 2047 | 2250 | 2220 | 2675 | 2876 | 3301 | 3369 | 3057 | 3196 | 3147 | 2960 | 2872 |

| Villanovaforru | 506 | 517 | 593 | 615 | 655 | 709 | 741 | 770 | 905 | 931 | 846 | 789 | 733 | 700 | 681 |

| Villanovafranca | 1356 | 1166 | 1121 | 1189 | 1286 | 1369 | 1577 | 1633 | 2055 | 2117 | 1759 | 1871 | 1621 | 1491 | 1433 |

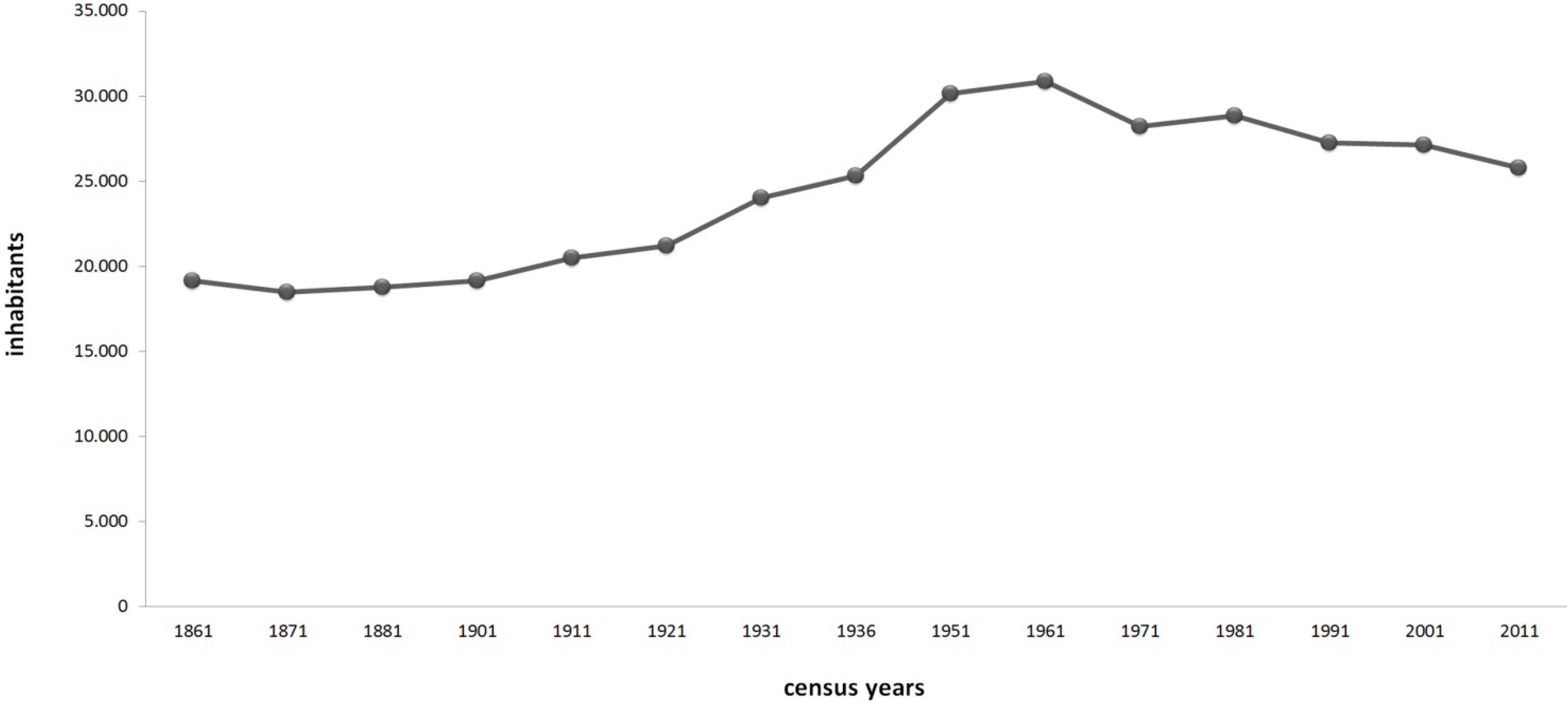

| Marmilla | 19,156 | 18,504 | 18,762 | 19,168 | 20,498 | 21,210 | 24,010 | 25,309 | 30,166 | 30,881 | 28,216 | 28,873 | 27,266 | 27,135 | 25,808 |

| Sardinia | 609,015 | 636,413 | 680,450 | 795,793 | 868,181 | 885,467 | 983,760 | 1,034,206 | 1,276,023 | 1,419,362 | 1,473,800 | 1,594,175 | 1.648,248 | 1,631,880 | 1,639,362 |

3.2. Development of the Tourism Sector in Marmilla

| Protection and Cultural Landscape | Development of Sustainable Tourism |

|---|---|

| ENVIRONMENTAL SUSTAINABILITY; | LOCAL ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT; |

| Preservation of landscapes, habitats, and ecosystems; | Encouraging the development of local firms and businesses; |

| Promotion of the use of renewable resources; | Encouraging the formation of employment aimed at sustainability of the tourism sector; |

| Introduction or improvement of environmental management systems; | Encouraging public and private partnerships; |

| Protection of the main territorial vocations | Promoting the construction or renovation of buildings for rural tourism, sustainable in the long term, despite changing political mandates |

| ECONOMIC SUSTAINABILITY; | SUSTAINABLE ENVIRONMENTAL DEVELOPMENT; |

| Development of landscape quality recognized by international bodies (UNESCO, etc.); | Encouraging initiatives dedicated to diversification of tourism and to the redistribution of tourist flows; |

| Development of a market for local goods and sustainable services; | Protecting and promoting the cultural and historical heritage; |

| Encouraging investments in innovative, environmentally friendly technologies | Encouraging the demand for and the achievement of environmental certification in the tourism sector |

| SOCIAL SUSTAINABILITY; | SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT; |

| Triggering processes of awareness of local tangible and intangible goods; | Developing the integration between different policy sectors; |

| Activating processes to raise awareness of the topic of sustainable development, protection, and enhancement of cultural heritage and public spaces; | Construction of participatory practices aimed at promoting the latest information technology tools for tourism purposes; |

| Improving the participatory practices; | Developing a place-based approach in which the local community is integrated with tourists; |

| Improving the network of relationships between various stakeholders | Promoting opportunities that induce residents to identify unique regional elements |

4. Tourism and New Media, a Possible Combination in Rural Contexts?

- (1)

- There is an overarching need to promote sustainable tourism across Marmilla, and not only in the main polarity (for instance what today includes the Nuraghe of Barumini), by highlighting the region’s rural and cultural aspects and creating an integrated quality. These aspects include local museums, exhibitions, cultural events, and the interrelation of individual museums associated with rural structures, and interactive educational farms and/or guided tours as part of ongoing rural processes—such as harvesting grain and saffron.

- (2)

- A second required action is developing the skills needed to begin proper planning and programming for rural tourism, through a centralized control, in which experts do not have local interests and are capable of supporting the often fragmentary and conflicting dynamics typical of rural areas. This can be achieved by involving experts who are external to the region.

- (3)

- Next, it will be necessary to enhance local places’ competitiveness (for example, by returning to traditional ways of promoting eco-museums, permanent, temporary, or itinerant events, exhibitions, and installations) and entrepreneurial tourism (through prizes or incentives to operators and companies that are distinguished by the quality offered, or through actions that stimulate an increase in the number of beds offered, while basing projects on ethical and sustainable development models).

- (4)

- A fourth action will involve integrating agricultural activities with services that are compatible with tourism activities, by proposing shop windows that display local products.

- (5)

- The visibility of local attractiveness should be unified, by creating a place-based promotion of the entire region of Marmilla (from the establishment of a centralized structure that encourages the formation of networks of rural enterprises, to joint agreement on a unique logo for the area and/or for place-based marketing).

- (6)

- Demand loyalty should be strengthened, through a series of actions aimed at enhancing internal communications among municipalities, and external communications between Marmilla and the rest of the world (for example, launching marketing actions on specific segments; promoting new tourism packages; conducting surveys to understand visitors’ motivations for coming, enhancing the interest and attractiveness of new offers; improving web marketing actions; promoting seasonal offers; and encouraging the movement of visitors from established attractions to previously unknown places of interest).

- (7)

- Finally, a commitment to sustainability should be used as the parameter for planning tourism in the area. On this point, it is essential that common goals and partnerships among the parties involved be identified, to foster understanding and to periodically update the processes, strategies, and planning associated with tourism development.

5. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References and Notes

- McCannell, D. The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari, C.; Adamo, G.E. Autenticità e risorse locali come attrattive turistiche: Il caso della Calabria. Sinergie 2012, 66, 79–113. [Google Scholar]

- Stamboulis, Y.; Skayannis, P. Innovation strategies and technology for experience-based tourism. Tour. Manag. 2003, 24, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turco, A. Turismo e Territorialità. Modelli di analisi, strategie comunicative, politiche pubbliche; Unicopli: Milano, Italy, 2012. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Hall, D.R.; Roberts, L.; Mitchell, M. New Directions in Rural Tourism; Ashgate: Hants, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Long, P.; Lane, B. Rural tourism development. In Trends in Outdoor Recreation, Leisure and Tourism; Gartner, W.C., Lime, D.W., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2000; pp. 299–308. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Community action in the field of tourism. Commission communication to the Council. Bulletin of the European Communities, Supplement 4/86, p. 10. Available online: http://aei.pitt.edu/5410/ (accessed on 21 February 2015).

- This concept resumes the sustainable development process, in which current needs are satisfied without compromising the needs of future generations (Brundtland Commission. World Commission on Environment and Development Sustainability; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987).

- Simonicca, A. Antropologia del turismo, strategie di ricerca e contesti etnografici; La Nuova Italia Scientifica: Roma, Italy, 1997; pp. 169–173. [Google Scholar]

- Daugstad, K. Negotiating landscape in rural tourism. Ann. Tourism Res. 2008, 35, 402–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barke, M. Rural tourism in Spain. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2004, 6, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, H. The right to the city. In Writings on Cities; Kofman, E., Lebas, E., Eds.; Blackwell: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995; pp. 63–184. [Google Scholar]

- Corner, S.; Swarbrooke, J. International Cases in Tourism Management; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cawley, M.; Gillmor, A.D. Integrated rural tourism: Concept and practice. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 316–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, D. Active regions–shaping rural futures: A model for new rural development in Germany. In Coherence of Agricultural and Rural Development Policies; Diakosavvas, D., Ed.; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2006; pp. 333–352. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L. Online rural destination images: Tourism and rurality. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2014, 3, 227–240. [Google Scholar]

- Balestrieri, A.D. Il turismo rurale nello sviluppo territoriale integrato della Toscana; Irpet: Firenze, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Giffinger, R.; Fertner, C.; Kramar, H.; Kalasek, R.; Pichler-Milanović, N.; Meijers, E. Smart Cities: Ranking of European Medium-Sized Cities; Vienna University of Technology: Vienna, Austria, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Garau, C. Smart paths for advanced management of cultural heritage. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2014, 1, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A. Introduction to Neogeography; O’Reilly: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Goodchild, M.F. Twenty years of progress: GIScience in 2010. J. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2010, 1, 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Su, K.; Li, J.; Fu, H. Smart city and the applications. In Proceedings of 2011 International Conference on Electronics, Communications and Control, Zhejiang, China, 9–11 September 2011; pp. 1028–1031.

- Basile, F. Una breve analisi congiunturale del Mezzogiorno nel contesto internazionale e riflessioni preliminari sul settore turistico. In Turismo e territorio: l'impatto economico e territoriale del turismo in Campania; Bencardino, F., Ed.; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2010; pp. 15–36. [Google Scholar]

- Piano strategico per lo sviluppo del turismo in Italia. p. 10. Available online: http://www.agenziademanio.it/export/download/demanio/agenzia/5_Piano_strategico_del_Turismo_2020.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2015).

- Angeloni, S. Cultural tourism and well-being of the local population in Italy. Theor. Empir. Res. Urban Manag. 2013, 8, 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Musarò, P. Responsible tourism as an agent of sustainable and socially-conscious development: Reflections from the Italian case. Recerca: revista de pensament i anàlisi 2014, 15, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciarelli, S.; Della Corte, V. Il comportamento del turista in condizioni di forte incertezza decisionale. Sinergie rivista di studi e ricerche 2011, 66, 137–152. [Google Scholar]

- Paniccia, P.; Vannini, I. Da impresa agricola a agriturismo: un percorso nell'ottica della sostenibilità. In Le imprese nel rilancio competitivo del Made e Service in Italy: settori a confront; Ciappei, C., Padroni, G., Eds.; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2012; pp. 59–71. [Google Scholar]

- Piano strategico per lo sviluppo del turismo in Italia. pp. 5, 30, 47. Available online: http://www.agenziademanio.it/export/download/demanio/agenzia/5_Piano_strategico_del_Turismo_2020.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2015).

- Santamato, V.R. Turismo e territorio: un rapporto complesso. In Esperienze e casi di turismo sostenibile; Messina, S., Santamato, V.R., Eds.; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Istat. Le aziende agrituristiche in Italia 2013. Rapporto aggiornato al 10 ottobre 2014. Available online: http://www.istat.it/it/archivio/133966 (accessed on 21 February 2015).

- The ISTAT surveys consider only those farms that are treated as such, according to different regional standards. This means that these surveys do not consider those structures that provide the same services but are not incorporated because they are not considered as such by the regional laws.

- Papotti, D. Marketing territoriale e marketing turistico per la promozione dell’immagine dei luoghi. Rivista Geografica Italiana 2006, 113, 285–306. [Google Scholar]

- Go, F.; Della Lucia, M.; Trunfio, M.; Martini, U. Governing sustainable tourism: European networked rural villages. In Rural Cooperation in Europe: In Search of the “Relational Rurals”; Kasabov, E., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Chennai, India, 2014; p. 163. [Google Scholar]

- Puggioni, G.; Atzeni, F. I comuni sardi a rischio di estinzione. In Comuni in estinzione. Gli scenari dello spopolamento in Sardegna; Progetto IDMS—2013; Regione Autonoma Della Sardegna: Cagliari, Italy, 2013; pp. 15–45. [Google Scholar]

- Elaborations made by the author on Demoistat Data (2014).

- Barumini, Collinas, Furtei, Genuri, Gesturi, Las Plassas, Lunamatrona, Pauli Arbarei, Sanluri, Segariu, Setzu, Siddi, Tuili, Turri, Ussaramanna, Villamar, Villanovaforru, and Villanovafranca.

- Bonifazi, C.; Heins, F. Le dinamiche dei processi di urbanizzazione in Italia e il dualismo Nord-Sud: un’analisi di lungo periodo. Rivista economica del Mezzogiorno 2001, 15, 713–748. [Google Scholar]

- Calza, B.P.; Cortese, C.; Violante, A. Interconnessioni tra sviluppo economico e demografico nel declino urbano: il caso di Genova. Argomenti 2010, 29, 105–131. [Google Scholar]

- Dematteis, G. Montagna e aree interne nelle politiche di coesione territoriale italiane ed europee. Territorio 2013, 66, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Author’s elaborations on census data from 1861 to 2011. In La popolazione dei comuni sardi dal 1688 al 1991; Angioni, D.; Loi, S.; Puggioni, G. (Eds.) Cuec: Cagliari, Italy, 1997.

- Author’s elaborations on Data DEMO-ISTAT 2014 and on Urbistat’s Data. Available online: http://www.urbistat.it (accessed on 21 November 2014).

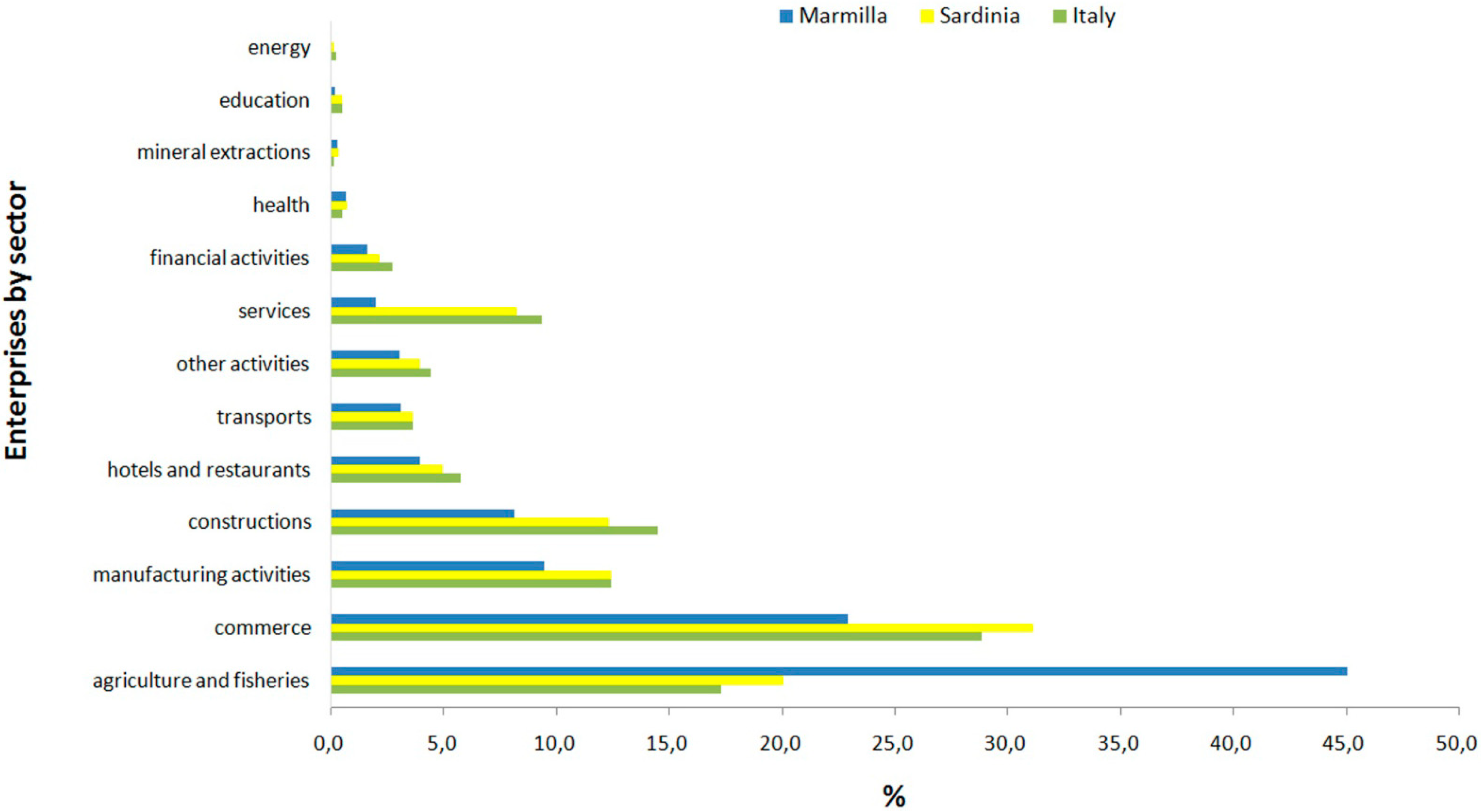

- Author’s elaborations on Urbistat’s Data. Available online: http://www.urbistat.it (accessed on 5 March 2015).

- For example, the Touristic Consortium of Genna Maria in the municipality of Villanovaforru was the first such association. This story begins in 1969, but was only legally recognized in 1982 because of the lack of agreement among the different municipalities. The Consortium, that later changed its name to Sa Corona Arrubia, then had members from other municipalities. Today there are about twenty members, and almost the same number of museums, as well as thirty-two archaeological areas, and a park’s environmental interest. Today Sa Corona Arrubia is having difficulties, although numerous other Consortia (the Consortium of Two Jars; the Consortium of the Natural Park of Monte Arci; and the Consortium Sa Perda e’Iddocca) have joined it over time. All these Consortia are directed and oriented by , and the interprovincial Local Action Groups (LAG) of the Union of Communities of Marmilla, development agencies; the interprovincial Local Action Groups (LAG) of Marmilla Borgioli C., Deligia M.G., Sa Corona Arrùbia—Consorzio Turistico della Marmilla. Available online: http://sistemimuseali.sns.it/content.php?idSC=103&el=9&c=106&ids=3&o=sistemiCulturali_dataInizioInterna#ds1 (accessed on 11 May 2015).

- Sirena, P. Museo Sa Corona Arrubia Museo Naturalistico del Territorio G. Pusceddu. Available online: http://www.sacoronarrubia.it/ (accessed on 4 February 2015).

- In 2005 the World Tourism Organization (WTO), used the “three pillars” to describe sustainable tourism: “sustainability principles refer to the environmental, economic and socio-cultural aspects of tourism development, and a suitable balance must be established between these three dimensions to guarantee its long-term sustainability”. Making Tourism More Sustainable: A Guide for Policy Makers; United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP): Madrid, Spain, 2005; pp. 11–12.

- Fons, M.V.S.; Fierro, J.A.M.; y Patiño, M.M. Rural tourism: A sustainable alternative. Appl. Energ. 2011, 88, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rural Development Programme (RDP) 2014–2020. Available online: http://www.regione.sardegna.it/speciali/programmasvilupporurale/2014-2020/psr-2014-2020 (accessed on 8 May 2015).

- Regional Development Plan (RDP) 2014–2019. Available online: http://www.regione.sardegna.it/j/v/66?s=1&v=9&c=27&c1=1207&id=44429 (accessed on 8 May 2015).

- Belij, М.; Veljković, Ј.; Pavlović, S. Role of local community in tourism development: Case study village Zabrega. Glasnik Srpskog geografskog drustva 2014, 94, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.C.; Allan, W. Tourism and Innovation; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- “The structural dimension (network ties, configuration and stability) reveals non-hierarchical and dense ties […]. Community members’ relationships are direct, informal, and long-term. There social ties feed and consolidate a strong sense of belonging to the place where these communities live and work and are the base on which inter-member economic ties and knowledge sharing are developed”. Go, F.; Della Lucia, M.; Trunfio, M.; Martini, U. Governing Sustainable Tourism: European Networked Rural Villages. In Rural Cooperation in Europe: In Search of the ‘Relational Rurals’; Kasabov, E., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2014; pp. 173–174. [Google Scholar]

- “From a cognitive dimensional perspective, social capital suffers from the fragmentation inherent in the heterogeneity of local stakeholders and sectorial diversification. Diversity of aims, interests, and competence renders the establishment of a critical mass for group decision-making among the local stakeholders difficult. [...] Information and education could help increase the awareness that networked knowledge sharing facilities inclusive economic institution-building and the emergence of a virtuous cycle of value-adding processes”. Go, F.; Della Lucia, M.; Trunfio, M.; Martini, U. Governing Sustainable Tourism: European Networked Rural Villages. In Rural Cooperation in Europe: In Search of the ‘Relational Rurals’; Kasabov, E., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2014; p. 175. [Google Scholar]

- “The relational dimension of social capital focuses on the character of connections, which serve to reinforce not only an organisation’s internal logic, but also (external) trustworthy relations”. Go, F.; Della Lucia, M.; Trunfio, M.; Martini, U. Governing Sustainable Tourism: European Networked Rural Villages. In Rural Cooperation in Europe: In Search of the ‘Relational Rurals’; Kasabov, E., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2014; p. 176. [Google Scholar]

- Nasser, N. Planning for urban heritage places: Reconciling conservation, tourism, and sustainable development. J. Plan. Lit. 2003, 17, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D.B. Tourism and the elusive paradigm of sustainable development. In A Companion to Tourism; Lew, A.A., Hall, C.M., Williams, A.M., Eds.; Backwell: Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 510–524. [Google Scholar]

- Law, R.; Leung, R.; Buhalis, D. Information technology applications in hospitality and tourism: A review of publications from 2005 to 2007. J. Travel Tour. Market. 2009, 26, 599–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garau, C.; Ilardi, E. The “Non-Places” Meet the “Places:” Virtual Tours on Smartphones for the Enhancement of Cultural Heritage. J. Urban Tech. 2014, 21, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garau, C. From Territory to Smartphone: Smart Fruition of Cultural Heritage for Dynamic Tourism Development. Plan. Pract. Res. 2014, 29, 238–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- According to Porrello, cultural planning enhances the totality of cultural, environmental, and naturalistic goods by taking strategic actions that are in line with the economic and social sustainability of the local context under study. Porrello, A. L’arte Difficile del Cultural Planning; Grafiche Veneziane: Venice, Italy, 2006; Available online: http://www.iuav.it/Ateneo1/docenti/pianificaz/docenti-st/Antonino-P/materiali-/Cultural_Planning.pdf (accessed on 11 March 2015).

- Below are some examples. Available online: http://www.turismo.intoscana.it/site/it/itinerario/Sei-un-turista-rurale/ and http://www.iAGRITURISMO.it. This last link in particular allows users to view the portal of Italian Farms in i-mode, with any type of mobile phone. Here too, the Tuscany region ranks high in the number of farmhouses present.

- Mistretta, P. Beni Culturali e sistema territorio. ArcheoArte 2012, 1, 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Mureddu, D.; Murru, G. Alla scoperta dei monumenti della Marmilla: Archeologia, arte, architettura; CRES: Cagliari, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lilliu, G. La civiltà dei Sardi dal paleolitico all’età dei nuraghi, (Vol. 98); Nuova Eri: Torino, Italy, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Atzeni, C. (Ed.) I manuali delle colline e degli altipiani centro-meridionali; Tipografia del Genio Civile: Roma, Italy, 2009.

- Atzeni, C.; Sanna, A. (Eds.) Architettura in terra cruda; Tipografia del Genio Civile: Roma, Italy, 2009.

- Purpura, A.; Ruggieri, G. Il distretto turistico: Caratteristiche e modelli organizzativi. In I distretti turistici: Strumento di sviluppo dei territori. L’esperienza nella regione Sicilia Milano; Cusimano, G., Parroco, A.M., Purpura, A., Eds.; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 2014; pp. 19–41. [Google Scholar]

- McAreavey, R.; McDonagh, J. Sustainable rural tourism: Lessons for rural development. Sociologia ruralis 2011, 51, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garau, C. Perspectives on Cultural and Sustainable Rural Tourism in a Smart Region: The Case Study of Marmilla in Sardinia (Italy). Sustainability 2015, 7, 6412-6434. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7066412

Garau C. Perspectives on Cultural and Sustainable Rural Tourism in a Smart Region: The Case Study of Marmilla in Sardinia (Italy). Sustainability. 2015; 7(6):6412-6434. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7066412

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarau, Chiara. 2015. "Perspectives on Cultural and Sustainable Rural Tourism in a Smart Region: The Case Study of Marmilla in Sardinia (Italy)" Sustainability 7, no. 6: 6412-6434. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7066412

APA StyleGarau, C. (2015). Perspectives on Cultural and Sustainable Rural Tourism in a Smart Region: The Case Study of Marmilla in Sardinia (Italy). Sustainability, 7(6), 6412-6434. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7066412