Abstract

Energy transition is expected to make an important contribution to sustainable development. Although it is argued that landscape design could foster energy transition, there is scant empirical research on how practitioners approach this new challenge. The research question central to this study is: To what extent and how is renewable energy science incorporated in regional landscape design? To address this knowledge gap, a case study of a regional landscape design competition in the Netherlands, held from 2010–2012, is presented. Its focus was on integral, strategic landscape transformation with energy transition as a major theme. Content analysis of the 36 competition entries was supplemented and triangulated with a survey among the entrants, observation of the process and a study of the competition documents and website. Results indicated insufficient use of key-strategies elaborated by renewable energy science. If landscape design wants to adopt a supportive role towards energy transition, a well-informed and evidence-based approach is highly recommended. Nevertheless, promising strategies for addressing the complex process of ensuring sustainable energy transition also emerged. They include the careful cultivation of public support by developing inclusive and bottom-up processes, and balancing energy-conscious interventions with other land uses and interests.

1. Introduction

Sustainable energy transition—the shift from a fossil-fuel based energy system to one based on renewable sources—is motivated by environmental, (socio-)economic and geopolitical factors [1,2,3]. In the coming decades, the transition to renewable energy is expected to make an important contribution to the process of sustainable development [3,4].

Historically, much of the world’s energy is provided by the (natural) environment and, in turn, its exploitation often had a considerable impact on the landscape [5,6,7]. Because of this reciprocal relationship, Ghosn [8], Bloemers, et al. [9], Stremke and van den Dobbelsteen [10], Ivančić [11], Radzi [12] and van Hoorn and Matthijsen [13], amongst others, argue that energy transition represents a challenge for those involved in planning and design. From the mid-1990s, landscape architects world-wide have been involved in studying the visual impact of wind parks [14] and developing strategies for siting wind turbines in the landscape [15,16]. More recently, however, a more strategic approach to energy transition has emerged that includes fostering a sustainable realization of energy transition goals from a spatial perspective [17,18,19]. To this end, academics working in the field of landscape architecture developed spatial design concepts and principles, based on insights derived from renewable energy science, thermodynamics, systems science, and ecology [20,21,22]. The process of implementing the envisaged strategic approach would begin with surveying and mapping potential energy saving and generation resources in a selected environment using, for example, Energy Potential Mapping methodologies and GIS [1,23,24]. In addition this approach to energy-conscious planning and design would involve making spatially explicit scenarios and envisioning (long-term) interventions [1,25,26,27].

The relevance of knowledge and theory as the basis for planning and design is addressed in notions such as “knowledge-based design” [28], “evidence-based practice” [29], “evidence-based landscape architecture” [30], and “evidence-based design” [31,32]. To enhance the development of landscape architecture as an academic discipline and to provide a bases for evidence-based practice Meijering, et al. [33] and Deming and Swaffield [31] emphasize the importance of a shared and focused research agenda in landscape architecture. In the context of energy transition, the departure point for evidence-based landscape design practice can be found in renewable energy science, and the studies referred to above that translate fundamental insights into spatial design concepts, principles and procedures for energy-conscious design. That evidence-based approaches are appropriate in the context of energy transition assignments was illustrated by Twidell and Weir [3] (p. 2) who concluded that “Failure to understand the distinctive scientific principles will almost certainly lead to poor engineering and uneconomic operation”. Although landscape design operates at larger levels of scale than individual technical installations, it can be argued that insights from renewable energy science will enhance effective energy-conscious planning and designing. Given the importance and availability of insights, it is surprising that there is a lack of empirical research into whether and how practitioners in landscape design take up the challenge of energy transition. Our research question, therefore, is: To what extent and how is renewable energy science incorporated in regional landscape design? To answer this question we studied the results of the Ninth Eo Wijers Regional Landscape Design Competition (The Ninth Eo Wijers Competition), because it focused on integral, strategic landscape transformations and energy transition as a major theme. Other landscape design competitions that referred to energy transition, tended to focus on smaller levels of scale and/or land art (for instance [34,35,36]). It was decided to focus on a design competition instead of (implemented) design projects for two reasons. First, studying the products of an ideas competition allowed to focus on the designer’s intentions given that designs, compared to implemented projects, are less influenced by practical, financial and political factors [37]. Moreover, studying competition entries made it possible to compare designs, because each team was working on the same assignment set by the competition and subject to the same social context and time frame [38].

The structure of this paper is as follows. Section 2 contains a description of The Ninth Eo Wijers Competition. In Section 3, key-strategies from renewable energy science crucial for energy-conscious planning and design are elaborated within a theoretical framework. Research materials and methods are described in Section 4. In Section 5 there is a detailed discussion of results of this study. The conclusions are summarized in Section 6.

2. The Ninth Eo Wijers Regional Landscape Design Competition

Since 1985, the Eo Wijers Foundation has been promoting Dutch regional landscape design, mainly by organizing a prestigious competition every two to three years [39]. After the seventh competition in 2004, the structure of the competition was changed to some extent. A preparatory phase designed to encourage joint learning and debate among potential competition regions was added. At the end of this phase, the competition region is selected. An implementation phase was also added to the ideas competition and the Foundation committed itself to supporting the implementation of prize-winning ideas [40].

At the beginning of the Ninth competition, the Eo Wijers Foundation identified the themes of energy transition, population decline and spatial quality as being of urgent national relevance [41]. The Veenkoloniën (“Peat Colonies”) region was selected as competition region because the themes of energy transition and population decline were most apparent there.

The Veenkoloniën in the North of the Netherlands covers some 800 km2 and is an area where peat used to be extracted (Figure 1). The Foundation developed the competition brief in cooperation with a body of regional representatives, known as the “Agenda voor de Veenkoloniën”. This is a partnership between the Provinces of Drenthe and Groningen, eight municipalities and two water boards that aims to increase the socio-economic capacity of the region. In the final competition brief, the Foundation’s initial themes were merged with input from the region and included four issues: “population decline”, “energy”, “agriculture” and “water management” [41]. The Foundation’s spatial quality theme was regarded an overarching theme and was, therefore, taken up as one of the seven criteria to be considered by the jury. The instruction detailing the competition requirements with regard to energy is presented in Box 1.

Figure 1.

Location of the competition region Veenkoloniën within The Netherlands.

Box 1. Specific competition instruction relating to the theme energy for the Ninth Eo Wijers Competition ([1] (p. 21); translated from Dutch).

“Alternative energy sources can reduce dependence on fossil fuels. Bio-, solar, geothermal and wind energy have potential. The national government wants to realize 400 MW extra wind energy capacity in Northeast Netherland. Also the regional authorities want to encourage reliable and affordable energy provision with low emissions of greenhouse gases. Therefore, make the most of the opportunities for renewable energy generation and distribution, inter alia by providing adequate spatial possibilities. Also saving energy, the careful use of subterranean resources for energy provision, the storage of CO2, green gas, natural gas and energy infrastructure are important. What do these mean for regional spatial development? The central notion in the ‘Grounds for Change’ philosophy is that our society must adjust to contemporary landscapes, which emerge through the use of, for example, wind power, and a more intensive use of subterranean resources. This process meets resistance in society and therefore demands careful selection and development of landscape sites and the involvement of the population.”

In general, the competition entries should contain plans and designs relevant to local, regional and supra-regional levels. Because public support was highly valued, the regional representatives facilitated interaction between those taking part in the competition and local stakeholders. Two informative meetings were held and competitors were strongly recommended to collect local field data. Moreover, competitors were challenged not only to make spatially explicit designs, but also to rethink current planning processes by developing process-oriented proposals. Because of the complex and integrative nature of the assignment, the Eo Wijers Foundation suggested competitors form multi-disciplinary teams that would consist of landscape designers and planners, experts from the social and natural sciences as well as local experts [41].

The competition phase was launched in June 2011. The submission deadline was 6 January 2012 [41]. By then, 36 contributions had been submitted by 204 entrants. By 22 March 2012, the winners were announced during a special award ceremony that received considerable national attention.

3. Theoretical Framework

In this section, we present the theoretical framework that was developed on the basis of the literature. This framework provided the basis for a coding scheme and this will be referred to later in the section dealing with methods. This framework was central to the subsequent analysis of competitors’ entries and focuses on key-strategies for energy transition as identified by renewable energy experts. These were strategies that were relevant for energy-conscious landscape planning and design and that were readily available at the time of the competition. Four key-strategies are addressed in the following subsections: reductions in energy demand (3.1), diversity of energy supply (3.2), reduction of fossil fuel emissions (3.3), and consideration of the energy system components (3.4).

3.1. Reductions in Energy Demand

The first strategy in energy transition aims at increasing energy efficiency [3,42,43]. This is because determining the demand for energy is the starting point for organizing energy supply; when demand falls, less energy has to be provided. Energy efficiency—providing the same services with a reduced amount of energy—can be achieved by energy saving practices and by ensuring a better match between energy supply and demand. Most measures are beyond the influence of the spatial domain, for example, stimulating energy use at times of excess supply by offering reduced prices. Yet, efficiency can also be realized in the built environment. For example by improving the insulation and heat recovery capacity of buildings. This is already being applied and has considerable potential. On a larger scale, the spatial organization of the built environment can also be adapted to facilitate residual heat exchange between industry and housing, for example [22,44].

3.2. Diversity of Supply

The second strategy in energy transition focuses on increasing the use of renewable energy sources in meeting energy needs [42]. (Regional) energy supply is made up of electricity, heat and (transport) fuels, all of which are—in theory—interchangeable. At present, when focusing on the Dutch situation, a limited variety of conventional fuels such as crude oil, natural gas, coal and nuclear energy meet almost the whole energy demand [45]. However, when moving towards renewable energy sources, a more diverse mix of sources and conversion technologies will be needed. This is because, for example, there is a limit to the availability of sources of renewable energy in space and time, and their potential for generation, conversion, distribution and storage [2,3]. Moving towards renewable energy sources will affect the amount of space needed to satisfy energy demand, and conversion technologies such as wind turbines, which are bound to windy locations, will change the landscape [1,7]. This is why landscape designers have been involved in the siting and design of renewable energy technologies. Following a more strategic approach, landscape designers could support the mapping of renewable and residual energy potentials, that could well be the starting point for organizing renewable energy provision in a given region [3,23,24].

3.3. Reduction of Fossil Fuel Emissions

A third strategy in energy transition focuses on achieving a reduction in fossil fuel emissions [3,42]. The transition to other forms of energy in the past has taken time and the current transition to sustainable energy should be seen in this context [45]. In the meantime, fossil fuels will not be abandoned overnight. When fossil fuel use is unavoidable, negative effects on the environment should be reduced as far as possible, for example through Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) techniques [43,45].

3.4. Consideration of the Energy System Components

In this paper, the term energy system refers to the interconnected whole of energy sources (areas where local energy supply exceeds the consumption) and sinks (where local energy consumption exceeds the supply) as well as the technologies associated with converting, distributing and storing energy [3]. Energy distribution is about getting energy to the right place; energy storage is about ensuring there is sufficient energy available for anticipated needs [3].

Since energy transition requires a changed approach to energy sources and conversion technologies, the infrastructure for distribution and storage must be adapted accordingly [2,3,46]. This will affect land use and landscape image [3,13,47], given that implementation will have a direct impact on the landscape. The utilization of geothermal energy, for example, involves specific pumps, pipes and associated installations for energy distribution. Moreover, due to fluctuations in supply of renewable sources, such as wind, solar and tidal energy, storage capacity may have to be increased. As with renewable energy sources and conversion technologies, surveying and environmental mapping can guide the location of potential energy storage and distribution infrastructure. In this way, for example, empty salt caverns and artificial lakes in the Netherlands were identified as potential options for storing biogas and kinetic energy [23].

4. Materials and Methods

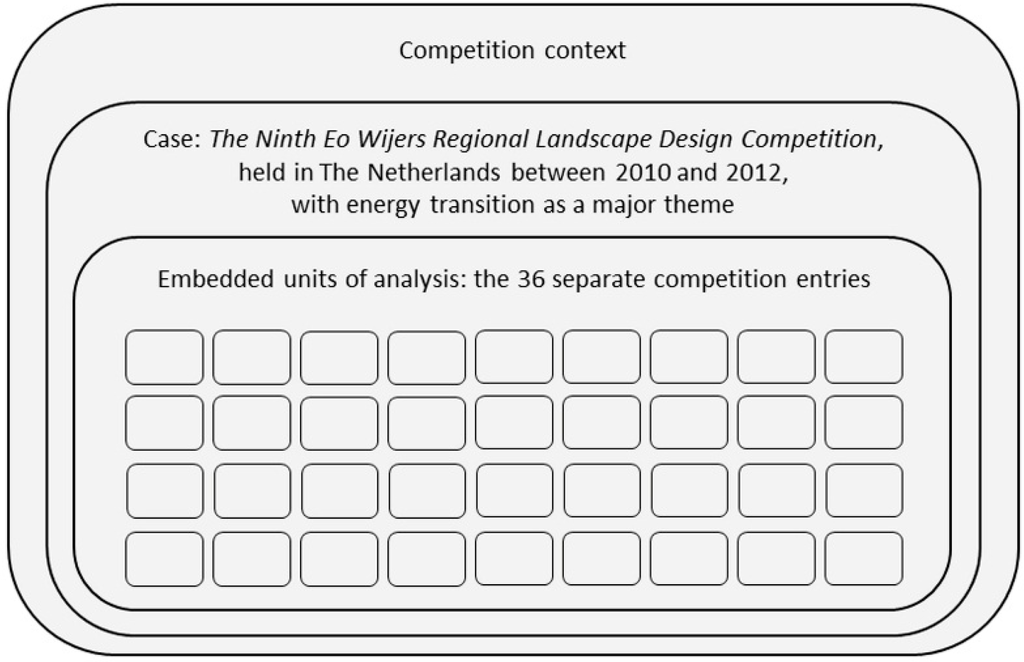

The research presented in this paper followed the general guidelines for case study research outlined by Yin [48]; The Ninth Eo Wijers Competition was analyzed in context and a variety of data and methods were used. The study has a single-case design, in which the competition entries are considered embedded units of analysis [48] (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The single-case design with 36 embedded units of analysis (based on Yin [48] (p. 46)).

4.1. Content Analysis of the 36 Competition Entries

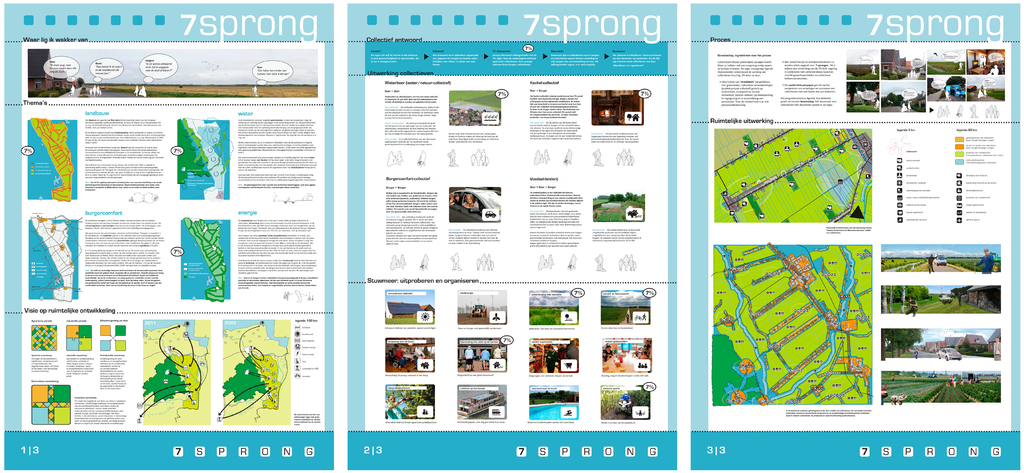

The 36 competition entries submitted form the empirical basis of this study. The Foundation made the original competition entries available to us digitally and in hard copy. Each entry consisted of at least three A0-sized posters and an essay of about 1500 words. An example of the posters submitted by the competitors is presented in Figure 3. All entries can be accessed online, at http://www.veenkolonien.nl/83-eo-wijers.html (in Dutch).

Evaluating designs is a reflective activity, and involves several interpretive steps including sorting out, analysis and comparison which lead to a deeper understanding of the diverse aspects of the design process and its results [38]. In analyzing the competition entries we adopted a qualitative content analysis procedure using a combination of predetermined and emerging codes [49]. Coding was executed manually. Results were gathered and clustered in an Excel spreadsheet for (comparative) analysis. The text and the visual data from the entries—plans and designs, schemes, graphs, sections, ‘bird’s eye’ perspectives, and artist impressions—were analyzed using the same procedure and coding scheme. This was possible because the focus was on exploring the content of the data, and not on how words and images were used to solicit a particular effect (see also [50]).

The predetermined codes were drawn from renewable energy science and the competition brief itself. The codes derived from renewable energy science addressed the four key-strategies for realizing energy transition (see the theoretical framework discussed in Section 3). Dimensions and indicators were defined in order to operationalize these strategies. For the diversity of supply strategy, amongst others, the following dimensions were defined:

- (1)

- Catering for the regional energy demand using at least two options derived from electricity, heat, and (transport) fuels;

- (2)

- Making use of at least one renewable energy source and/or conversion technology;

- (3)

- Making use of more than one kind of renewable energy source and/or conversion technology and in this way acknowledging the need for a diversified energy mix.

Indicators were used to establish the presence of these dimensions and the presence of key-strategies for energy transition in the competition entries. These refer to the codes in the coding scheme, for example “electricity”, “heat” and “(transport) fuels” for the first dimension referred to above, and various kinds of renewable energy sources and technologies for the second and the third dimension.

Figure 3.

The three A-0 sized posters that accompanied the entry “7Sprong”. Reproduced with permission of the authors: Frank Stroeken, Jan Maurits van Linge, Sander van den Helm, Jannemarie de Jonge, Rianne Knoot and Ruth Dobbelsteen (from [51] published by Eo Wijers-stichting, 2012).

The competition brief, as has been explained in Section 2, suggested entrants create spatially explicit designs at three levels of scale but that they should also rethink the planning procedures currently being used in the area. In addition, the integrative nature of the assignment and the suggestion to work in multidisciplinary teams played an important role in this competition. Therefore, we also chose to incorporate these strategies in this study. In order to analyze the nature of the proposals, we coded whether an entry focused on process-oriented proposals and/or spatially explicit designs. To examine the integration of energy-conscious interventions with other (competition) themes and interests, we coded indicators for population decline, agriculture and water management and spatial quality. A number of codes also emerged here that referred to land use, for example. Table 1 in Section 5.1 provides an overview of the strategies and the dimensions we used.

4.2. Study of the Competition Context and Triangulation of Data and Methods

In addition to the content analysis of competition entries, three other sources of data were used. This was done to enable the triangulation of results and to establish the context in which the competition entries were created and judged. First, the competition process was observed by the lead author of this paper, who attended the meetings organized by the Foundation, and followed the judging process. The third author of this paper was in fact a member of the professional jury. In this way, the outcomes of the content analysis and the opinion of the jury could be compared. Second, a survey was held to gain insight into the background of those who had entered the competition, their opinion about the theme of energy transition in relation to landscape design, and the sources and reference projects they had used in developing their entry. The survey was posted online directly after the award ceremony and remained online for three weeks. The 242 people who had initially signed up for the competition were invited to take part in the survey. In total some 126 people responded, 100 of whom had actually participated in the competition. This represented 33 out of the total of 36 participating teams. Prior to being submitted, the survey had been tested by four colleague researchers. Third, in order to build up a complete image of the competition process as a whole, the Foundation’s written records and online resources including its website (www.eowijers.nl) the competition brief [41] and the jury report [51], were also taken into account.

4.3. Research Quality and Limitations

Although analyzing an individual case has limitations as far as the generalization of results is concerned, we argue that this study—because of its uniqueness and its empirical character—provides new insights into the (potential) contribution that landscape design can make to energy transition. In addition to the triangulation of data sources and methods such as those described above, the content analysis has been cross-checked by the authors themselves and reviewed with two members of the Foundation. Even so the limitations of single case study methods should be borne in mind when assessing the implications of the conclusion.

5. Results and Discussion

In this section, the findings of the study are presented and discussed. In Sub-section 5.1, the results of the content analysis are explained and in Sub-section 5.2 the judging process and outcomes are described. Sub-section 5.3 deals with the results of the survey.

5.1. The Competition Entries

We now present the results of a content analysis of the 36 competition entries. For an overview, see Table 1. In Sub-subsection 5.1.1, Sub-subsection 5.1.2, Sub-subsection 5.1.3 and Sub-subsection 5.1.4 the results are described of analyzing the extent to which key-strategies derived from renewable energy science were present in the entries. Sub-subsection 5.1.5 shows the extent to which the entries contained spatially explicit designs and/or process-oriented proposals and 5.1.6 deals with the extent to which energy-conscious interventions were integrated with other (competition) themes and objectives.

Table 1.

Overview of results of a content analysis of competition entries.

| Origin | Strategy | Dimension Present in the Entries | % of the Entries |

|---|---|---|---|

| Renewable energy science | Reductions in energy demand | Proposals for improving energy efficiency, e.g., by energy saving measures | 31% |

| Reference to goals for energy efficiency and/or renewable energy generation in specific, quantitative terms | 8% | ||

| Diversity of supply | Catering for the regional energy demand using at least two options derived from electricity, heat, and (transport) fuels | 78% | |

| Making use of at least one renewable energy source and/or conversion technology | 97% | ||

| Making use of more than one kind of renewable energy source and/or conversion technology and in this way acknowledging the need for a diversified energy mix | 86% | ||

| Calculations indicating the contribution of proposed energy-conscious interventions | 14% | ||

| Reduction of fossil fuel emissions | Proposals for the use of CCS (Carbon Capture and Storage) and/or alternative solutions for reducing fossil fuel emissions | 19% | |

| Consideration of the energy system components | Proposals for at least two of the following: energy generation, energy distribution, and energy storage | 58% | |

| Proposals for energy generation, energy distribution and energy storage that acknowledging the fact that energy-conscious interventions should be seen as components of a larger energy system | 25% | ||

| The competition brief | The nature of proposals | Process-oriented proposals for realizing energy-conscious designs and plans | 89% |

| Spatially explicit designs for locating, planning and/or designing energy-conscious interventions | 58% | ||

| Integration with other (competition) themes and interests | Combinations of energy-conscious interventions and other (competition) themes that show energy transition from an integrative landscape design perspective | 89% | |

| Extent to which entries document the motivations for energy-conscious interventions | 97% |

5.1.1. Reductions in Energy Demand

In 31% of the entries energy efficiency measures were proposed and these ranged from car-pooling to installing insulation (see Table 1). Next an assessment was made as to whether the entrants had defined the goals for energy efficiency and/or renewable energy generation in specific, quantitative terms that they wanted to achieve with their proposals. Only 8% of the teams had done so (see Table 1). Two of these teams specified the targets for regional energy self-sufficiency for the years 2025 and 2040 respectively. A third team quantified the regional energy demand and expressed the goal of regional energy self-sufficiency, but did not specify a specific time period.

Taken together, these results indicated that the strategy of reducing the energy demand was only applied by one third of the teams, although a diverse palette of interventions was proposed. Hardly any team mentioned explicit targets for energy efficiency and/or renewable energy generation as a starting point for purposefully matching energy demand with supply. Strikingly, none of the entrants took the 400 MW of wind energy that the national government wants to realize in the North of the Netherlands into their proposed design, even though this was part of the competition brief.

5.1.2. Diversity of Supply

Regarding the strategy to diversify energy supplies, 78% of the entries proposed the provision of multiple forms of energy, namely electricity, heat and fuels (see Table 1). Almost all entries, 97%, proposed at least one renewable energy technology to meet regional energy demand (see Table 1). Eighty-six percent of the entries (see Table 1) proposed more than one renewable energy technology. Table 2 provides an overview of renewable energy sources and technologies proposed. Biomass (from landscape maintenance and/or energy crops; excluding biomass waste streams) was proposed most frequently, in 75% of the entries (see Table 2) and the specific rural and agricultural character of the region was often given as the reason for proposing this source. Onshore wind energy came in at second place and was proposed in 64% of the entries (see Table 2). The fierce opposition to onshore wind turbines was explicitly mentioned by entrants as one of the reasons for looking into alternative renewable sources and technologies. On average, between three and four different renewable sources and technologies were proposed per entry. Therefore, although biomass and onshore wind turbines were proposed relatively frequently a number of other sources and technologies capable of meeting regional energy demand were also taken into account. In Figure 4 it can be seen how one of the entrants envisioned a landscape in which a variety of renewable energy sources and technologies were integrated. Only 14% of the teams explained their energy-conscious interventions by quantifying the expected contribution of their proposals in, for example, joule or kWh (see Table 1).

Case results show that it can be concluded that the entrants were well aware of the concept of diversity of supply and the technologies available for renewable energy generation. It could also be concluded that they showed an understanding of the fact that different forms of energy (electricity, heat and fuels) needed to be catered for [2,3,43]. In this particular competition, the regional landscape and local social conditions clearly played a role in the choice of renewable energy resources and technologies. Some teams explained their proposals regarding energy transition in quantitative terms, but this did not lead to a purposeful and efficient matching of energy demand and supply, as is common in energy planning [3].

Table 2.

Renewable energy sources and conversion technologies proposed.

| Renewable Energy Sources and Conversion Technologies | % of the Entries |

|---|---|

| Biomass (excluding biomass waste streams) | 75% |

| Wind energy: onshore wind turbines | 64% |

| Solar energy: photovoltaic cells | 50% |

| Biomass waste streams | 47% |

| Residual heat | 36% |

| Heat and cold storage | 19% |

| Solar energy: solar collectors | 17% |

| Geothermal energy: heat | 17% |

| Combined heat and power | 17% |

| Geothermal energy: electricity | 6% |

| Other | 36% |

Figure 4.

“Verborgen kracht—Veenkoloniën 3.0”: An example of a design visualizing diverse renewable energy generation via solar, wind and biomass in the Veenkoloniën. Reproduced with the permission of the author Tim Snippert (from [51] published by Eo Wijers-stichting, 2012).

5.1.3. Reduction of Fossil-Fuel Emissions

With regard to this strategy, 19% of the entries (see Table 1) proposed to reduce emissions from remaining fossil fuels. None of the teams proposed CCS techniques as they have been developed for coal-fired power plants for example. Instead, five of the entries focused on the re-use of CO2 in greenhouses and/or for algae production. Two other entries proposed to (re)create peat lands or swamps to support CO2 sequestration in a natural way.

With regard to this strategy, we can conclude that only a few of the teams felt the need to reduce emissions by curtailing the use of fossil fuels by applying technical or natural solutions.

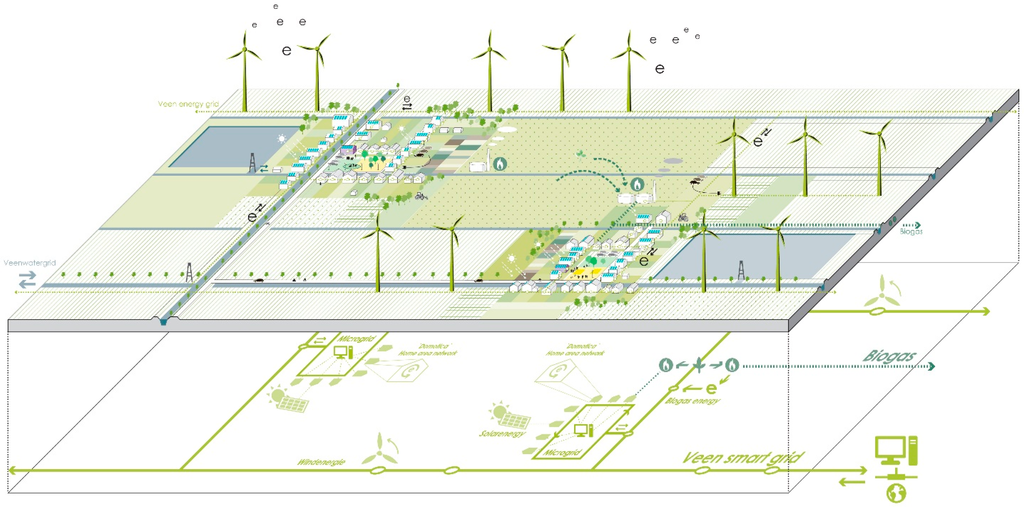

5.1.4. Consideration of the Energy System Components

Two or more components of energy systems—energy generation, energy distribution and energy storage—were proposed in 58% of the entries (see Table 1). Only nine of these entries—25% of the total number of entries—addressed all three components of energy systems as defined in the literature (see Table 1). Figure 5 gives an example drawn from an entry that addressed the components of energy generation, energy distribution and energy storage in a design model that can be scaled up to regional level.

Figure 5.

Veennet: an example of a schematic visualization of an energy system including the components of renewable energy generation, energy distribution and energy storage. Reproduced with permission from the authors Boris Hocks, Han Dijk, Emile Revier, Iris Wijn, Justina Muliuolyte, Dion van Dijk, Machiel Bakx and Michiel Brouwer (from [51] published by Eo Wijers-stichting, 2012.

Findings in respect of this strategy indicate that understanding and optimizing the energy system was a challenge and we found this surprising. Renewable energy may be a relatively new subject but landscape designers are used to approaching the landscape as system [28] and to working on solutions by going back and forth between interrelated levels of scale [52]. For these reasons, we had expected more entries to develop systemic approaches that addressed all three components of the energy system.

5.1.5. The Nature of Proposals: Spatially Explicit and/or Process-Oriented

Because the competition brief stressed the need to develop alternative, bottom-up, and inclusive planning processes, the entries were studied to determine whether they contained spatially explicit designs and/or process-oriented proposals relating to energy-conscious interventions. The number of process-oriented proposals at 89% outnumbered the 58% of spatially explicit designs. However, both process orientated proposals and spatially explicit designs were included in 53% of the entries.

Spatially explicit designs indicated, for example, the location and design of renewable energy technologies and how these could be integrated into the Veenkoloniën landscape. Process proposals, for example, included ideas for involving farmers in developing a bio-based economy and stimulating local cooperative car sharing. Sixty nine percent of the entrants used inputs from the region to develop new process proposals. Innovative strategies for stimulating interaction with local people and to harvest their input for making plans and designs included the use of social media. This has been discussed in de Waal, et al. [53].

From this analysis it became clear that it was not the spatially explicit designs that were central in this competition, which one would expect in a landscape design ideas competition, but process-oriented proposals. This is an interesting finding in the light of the cyclical governance model for (energy) transitions discussed by Loorbach, et al. [54]. Here (spatially explicit) envisioning is seen as one of many activity sets in transition processes. The other sets in this model are agenda building and networking, experimenting and diffusion, and monitoring, evaluating and adaptation. Each process-oriented proposal in the competition addressed at least some of these. In the Ninth Eo Wijers Competition, the competition brief—with its focus on process-oriented proposals—and the way the competition’s preparatory and implementation phases were organized, emphasized joint agenda building, networking, and the diffusion of results. It can, therefore, be concluded, that the scope of the concept of regional landscape design in relation to energy transition was significantly widened in the context of this competition.

5.1.6. Integration of Energy Transition Interventions with Other Competition Themes and Interests

As discussed in Section 2, the competition presented an integrated assignment which addressed not only the theme of energy transition, but also drew attention to factors such as population decline, agriculture and water management. We therefore decided to list which themes or land uses the entrants integrated with energy transition. In total, 89% of the teams responded to the call for integrated solutions. Table 3 specifies the combinations that were created.

Table 3.

Integration of energy-conscious interventions with other competition themes and land uses.

| Combinations with Other Competition Themes and Land Uses | % of the Entries |

|---|---|

| Agriculture | 72% |

| Water | 44% |

| Nature | 22% |

| Habitation | 22% |

| Industry | 19% |

| Recreation | 17% |

| Amenities (shopping, nightlife etc.) | 11% |

| Education and Research | 8% |

| Welfare (healthcare, childcare etc.) | 8% |

| Infrastructure | 6% |

Interestingly, connections were also made beyond the themes outlined in the competition brief and included nature development, habitation, industries and infrastructure. Figure 6 illustrates how one competition entry visualized the integration of renewable energy generation with agricultural production, health care, and education in a new type of farmyard structure.

Figure 6.

Two visualizations that show how renewable energy generation and agricultural production, habitation and welfare were combined on a new type of farmyard from the competition entry ‘Wat weet een boer van saffraan’. Reproduced with permission of the authors Richard Colombijn, Claire Oude Aarninkhof, Renzo Veenstra and Arjan Boekel (from [51] published by Eo Wijers-stichting, 2012.

In addition, we listed the motivations given by the entrants for energy transition that were relevant to energy-conscious interventions. Besides ‘direct’ motivations for energy transition—such as improving sustainability and ensuring a secure and affordable supply—more indirect motivations were also provided. For example, stimulating the regional economy by renewable energy generation was put forward as a motivation in 55% of the entries while 47% stressed that energy-conscious interventions should be carefully integrated with landscape image and regional identity (see Table 4). Here it is shown that difficulties arise when a new type of land use—such as a renewable energy provision—has to be integrated within the existing spatial order because in pursuit of sustainability the interests involved at different levels of scale may come into conflict with each other (see also [55,56]). The entrants showed however, on the positive side, how energy transition gave rise to exploring win-win strategies, for example, by introducing energy crops as a new agricultural product, or establishing a cooperative wind turbine venture as a way of promoting a sense of community. In total, only one team failed to provide a motivation for energy-conscious interventions (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Motivations energy-conscious interventions.

| Motivations and Interests | % of the Entries |

|---|---|

| Stimulating regional economy | 55% |

| Maintaining or improving landscape quality | 47% |

| Sustainability | 36% |

| Energy independence | 19% |

| Raising awareness about energy transition | 6% |

| Security of supply | 3% |

| Affordability of supply | 3% |

| Public acceptance of renewable energy technologies | 3% |

| Turning the region into a testing ground | 3% |

From this analysis, it became clear that the teams approached the theme of energy transition in a highly integrative way, as required by the competition brief. This is important, because it was found that interventions to promote sustainability sometimes have unintended aversive effects. As Stremke [18], elaborated in his article “Sustainable energy landscape: Implementing energy transition in the physical realm” adopting an integrative perspective that goes beyond the mere implementation of renewable energy technologies, and addressing sustainable, technical, economical and socio-cultural criteria in energy-conscious landscape design, would have a definite and positive impact on sustainable development.

5.2. The Judging Process and Outcomes

On 22 March 2012, the Eo Wijers Foundation was ready to award the prizes. There was a first, second and third prize, three honorable mentions and two young professional awards. The winners were selected according to a process of blind review. The jury consisted of professional and regional representatives. The regional jury had 11 members drawn from the civil sector, for example, residents, entrepreneurs and aldermen. The professional jury consisted of eight members whose expertise was directly related to the competition’s themes: population decline, energy transition, agriculture and water management [51].

The jury praised the entrants in general for the way they had approached the complex issues in the Veenkoloniën. However, it was also felt that only a third of the entrants had considered the placement of wind turbines in the area as a regional design challenge. None of the entries explicitly addressed the 400 MW of wind energy that, according to the competition brief, was needed in the North of the Netherlands. Neither did they present a clear vision of the regional energy supply when moving to renewable energy sources. During the award ceremony the chairperson explained it as follows [57]: “In the opinion of the jury, an evaluation of the landscape’s capacity for holding wind turbines required detailed argumentation. If the entrants assumed this capacity to be low or reduced—an effective alternative for wind energy should have been proposed.”—a conclusion that coincides with our own and which has been presented here.

5.3. Survey among the Competition Entrants

The background of competition entrants was analyzed by means of a survey. Each team consisted of an average of five to six persons. The largest team had 12 members. Only one entry came from a person working alone. The disciplinary backgrounds of the entrants varied and included, for example, landscape architecture, urban design, planning, architecture, history, energy consultancy, management, economics, industrial engineering and communication. Most teams followed the instruction of the competition brief and were—to varying degrees—multi-disciplinary in composition. The age distribution was varied. Seven percent of entrants were younger than 26 years; 34% were between 26 years and 35 years, 29% were between 36 years and 45 years. In addition 16% of entrants were between 46 years and 55 years and 13% were older than 55 years.

Moreover, because the content analysis and the jury’s evaluation of results suggested that the entrants approach to the application of the key-strategies that have emerged from renewable energy science was mixed and sometimes poor, we asked entrants to give us their opinion on energy transition as this related to landscape design. Seventy-two entrants answered our questions. The results were as follows:

- The respondents were positive about the potential contribution landscape design could make to energy transition (38% responded “yes, to large extent”; 54% responded ‘yes, to some extent’; seven percent responded ‘no’ and one percent responded “I do not know”);

- More than half the respondents believed that energy transition provides an opportunity to enhance spatial quality in the Netherlands (22% fully agreed; 35% partly agreed, 25% did not agree or disagree, 10% partly disagreed, 3% percent fully disagreed and 5% percent did not know).

These results indicated that, regardless of how energy transition was dealt with in the entries, the majority of entrants agreed with the organizing Foundation that it is an important element in regional landscape design. At least half of the entrants recognized the potential for enhancing spatial quality when working on energy transition.

In addition we asked entrants to list between one to three reference projects and one to three (written) sources of information on energy transition that they used in compiling their entry. These questions were answered by the teams involved rather than by individuals and were classified according to type. From the 33 teams that answered the survey, only 17 teams listed reference projects (43 in total) and 13 teams listed information sources (23 in total). The 23 information sources referred to by the entrants showed a wide degree of variety and very little overlap (see Table 5). Only one source was mentioned by four teams. This was Energielandschappen: De 3de generatie.Over regionale kansen op het raakvlak van energie en ruimte by Noorman and de Roo from 2011—a Dutch book on energy transition from a planning and design perspective [58].

Thirty-one of the 43 reference projects referred to specific, unique projects, such as the well-known Danish energy neutral island of Samsø, or the Dutch island of Texel. The remaining 12 reference projects were rather either unspecific or not unique; for example “wind energy in Germany” and “cooperatives that were already providing solar and wind energy”.

Table 5.

Types of information sources about energy transition listed by the teams.

| Types of Information Sources | Counts | Different Documents |

|---|---|---|

| Report by engineering or design firm | 6 | 6 |

| Book aimed at a professional audience | 6 | 3 |

| Input by expert | 3 | 3 |

| Research report | 3 | 3 |

| Opinion article | 1 | 1 |

| Policy report | 1 | 1 |

| Report by NGO | 1 | 1 |

| Scientific literature | 1 | 1 |

| Symposia | 1 | 1 |

| Totals | 23 | 20 |

As it seemed from this part of the survey, the teams had consulted very few (scientific) documents and no standard sources on renewable energy science had been referred to. Rather, the teams had tended to focus on reference projects. When combining these findings with the analysis of competition entries and the jury’s judgment, we must conclude that the underutilization of information on renewable energy science led—in the context of this regional design competition—to a less than optimal application of basic strategies for realizing energy transition.

6. Conclusions

The information that has been analyzed in this paper is derived from a regional landscape design competition that focused on renewable energy in the context of integral and strategic landscape transformation. Although it is argued that landscape design could foster energy transition from a spatial perspective, there is scant empirical research on how practitioners approach this new challenge. The research question addressed in this study, therefore, centres on the extent to which renewable energy science was incorporated into regional landscape design and how this was done.

Four key-strategies for energy transition were derived from renewable energy science: reductions in energy demand; diversity of energy supply; reduction of fossil fuel emissions and consideration of energy system components. By conducting a content analysis of the competition entries from the perspective of these key-strategies, we identified serious flaws in their application. All but one team, 97% of the entries, worked on renewable energy generation, and diversity of supply was addressed by 78% of the entries. Often regional landscape qualities and socio-economic conditions were the starting point for selecting renewable energy sources and technologies. However, just one third of the teams addressed strategies aimed at reducing energy demand. Only 19% of the teams addressed the problem of reducing fossil fuel emissions, and a mere 25% suggested solutions to the systemic problems of energy generation, energy distribution and energy storage. These figures suggested that, although informative literature was readily available at the time of the competition, the application of the four key-strategies that could be derived from renewable energy science was mixed and sometimes extremely poor. The competition jury had also commented negatively on the way in which energy transition had been dealt with by competition entrants. Based on these two sources, we concluded that there was a considerable gap between theory and practice.

A survey among entrants, however, showed that the respondents believed that energy transition is indeed a theme for regional landscape design, as the Eo Wijers Foundation competition brief suggested. In addition, more than half the respondents believed that energy transition provides an opportunity to enhance spatial quality in the Netherlands. Despite these opinions, the survey revealed little evidence that entrants had consulted the relevant literature on the subject. This might be the reason for the rather mixed and poor application of the key-strategies that can be derived from renewable energy science. These findings lead us to stress the importance of evidence-based approaches to landscape design, in terms of enhancing its development as a socially relevant academic discipline and one that has important implications for sustainable energy transitions.

Notwithstanding the hesitant application of renewable energy science, the competition in itself emphasized the role of landscape design in effective, sustainable energy transition. In fact, the competition brief included two strategies that were rewardingly elaborated by the entrants. These were the integration of energy-conscious interventions with other (competition) themes and interests, and the nature of proposals regarding energy transition. In terms of the latter, it appeared that spatially explicit designs, which can be seen as a more traditional product of landscape designers, were included in 58% of the entries. However, 89% of the entries directly referred to the importance of a process-oriented approach, and 53% of the entries included both. The main benefit of widening the scope of landscape design in this way was that it focused attention on the importance of public support and the development of inclusive and bottom-up processes, a development that is in line with recent insights into transition theory. A side effect was that competition entrants were confronted with the relatively new subject of energy transition, in combination with the assignment to create both spatially explicit and process-oriented proposals. We would recommend further research into the relationship between landscape design and transition theory—especially in relation to how transition goals can be realized by spatially explicit envisioning and inclusive, bottom-up planning processes. Fierce public resistance to the implementation of some renewable energy technologies at the local level and consequent delays in realizing energy transition goals, might be addressed by further research in this area.

Finally, we conclude that our study has shown that more attention should be given to an integrative approach to energy transition in regional landscape design as was emphasized by this competition. An integral approach seems to be one of the most important contributions of landscape design when energy transition is being considered in specific areas. A careful consideration of other land uses and interests including environmental impact and the implications for socio-economic and cultural aspects must be addressed in the complex task of facilitating sustainable energy transition.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Eo Wijers Foundation and competition entrants for their cooperation and making available competition materials. We are grateful to Adrie van ’t Veer for his help with Figure 1, and to Edo Gies, Annet Kempenaar, Marjo van Lierop and Jurian Meijering for their help in constructing the survey. Finally, we would like to thank the anonymous referees for their useful comments on the paper.

Author Contributions

Each author contributed to the research in terms of conception, research design, cross-checking data analysis and co-writing the paper. Renée M. de Waal was primarily responsible for data collection, analysis and writing of the paper. All five authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sijmons, D.; Hugtenburg, J.; Feddes, F.; van Hoorn, A. Landscape and Energy, Designing Transition; NAi010 Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tester, J.W.; Drake, E.M.; Driscoll, M.J.; Golay, M.W.; Peters, W.A. Sustainable Energy: Choosing among Options; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Twidell, J.; Weir, A.D. Renewable Energy Resources, 2nd ed.; Taylor & Francis: Oxon, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Brundtland, G.H. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: “Our Common Future”; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Leenaers, H.; Camarasa, M. De Bosatlas van de Energie; Noordhoff Uitgevers: Groningen, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mulder, K. The technological landscape. In Landscape and Energy: Designing Transition; Sijmons, D., Hugtenburg, J., Feddes, F., van Hoorn, A., Eds.; NAi Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 368–380. [Google Scholar]

- Pasqualetti, M.J. Reading the changing energy landscape. In Sustainable Energy Landscapes. Designing, Planning and Development; Stremke, S., van den Dobbelsteen, A., Eds.; CRC Press (Taylor & Francis Group): Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013; pp. 11–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosn, R. New Geographies 2: Landscapes of Energy; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bloemers, T.; Daniels, S.; Fairclough, G.; Pedroli, B.; Stiles, R. Landscape in a Changing World; ESF and COST: Strassbourg, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Stremke, S.; van den Dobbelsteen, A. Sustainable Energy Landscapes; Designing, Planning and Development; CRC Press (Taylor & Francis Group): Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ivančić, A. Energyscapes; Editorial Gustavo Gili: Barcelona, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Radzi, A. 100% Renewable champions: International case studies. In 100% Renewable. Energy Autonomy in Action; Droege, P., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 93–166. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoorn, A.; Matthijsen, J. De Ruimtelijke Impact van Hernieuwbare Energie: een Verkenning; Planbureau voor de Leefomgeving: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 1099. [Google Scholar]

- Mogen, E.A.H. The role of the landscape architect in the wind farm site selection process and best practices. In Conference of CELA and ISOMUL on Landscape Legacy: Landscape Architecture and Planning between Art and Science; Carsjens, G.J., Ed.; Wageningen University: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Schöbel, S. Windenergie und Landschaftsästhetik: Zur Landschaftsgerechten Anordnung von Windfarmen; Jovis: Berlin, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schöne, M.B. Windturbines in het Landschap. Nieuw Plaatsingsbeleid op Basis van Landschapsbeleving Gewenst voor de Jongste Generatie Windturbines; Alterra: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wächter, P.; Ornetzeder, M.; Rohracher, H.; Schreuer, A.; Knoflacher, M. Towards a sustainable spatial organization of the energy system: Backcasting experiences from Austria. Sustainability 2012, 4, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stremke, S. Sustainable energy landscape: Implementing energy transition in the physical realm. In Encyclopedia of Environmental Management; Jørgensen, S.E., Ed.; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2015; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- De Waal, R.M.; Stremke, S. Energy transition: Missed opportunities and emerging challenges for landscape planning and designing. Sustainability 2014, 6, 4386–4415. [Google Scholar]

- Stremke, S.; van den Dobbelsteen, A.; Koh, J. Exergy landscapes: Exploration of second-law thinking towards sustainable landscape design. Int. J. Exergy 2011, 8, 148–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stremke, S.; Koh, J. Ecological concepts and strategies with relevance to energy-conscious spatial planning and design. Environ. Plan. B: Plan. Des. 2010, 37, 518–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stremke, S.; Koh, J. Integration of ecological and thermodynamic concepts in the design of sustainable energy landscapes. Landsc. J. 2011, 30, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Dobbelsteen, A.; Broersma, S.; Fremouw, M. Energy potential mapping and heat mapping: Prerequisite for energy-conscious planning and design. In Sustainable Energy Landscapes. Designing, Planning and Development; Stremke, S., van den Dobbelsteen, A., Eds.; CRC Press (Taylor & Francis Group): Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013; pp. 71–94. [Google Scholar]

- Grêt-Regamey, A.; Wissen Hayek, U. Multicriteria decision analysis for the planning and design of sustainable energy landscapes. In Sustainable Energy Landscapes. Designing, Planning and Development; Stremke, S., van den Dobbelsteen, A., Eds.; CRC Press (Taylor & Francis): Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stremke, S.; Koh, J.; Neven, K.; Boekel, A. Integrated visions (part II): Envisioning sustainable energy landscapes. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2012, 20, 609–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thün, G.; Velikov, K. Conduit urbanism: Rethinking infrastructural ecologies in the great lakes megaregion, North America. In Sustainable Energy Landscapes. Designing, Planning and Development; Stremke, S., van den Dobbelsteen, A., Eds.; CRC Press (Taylor & Francis Group): Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013; pp. 261–284. [Google Scholar]

- Stremke, S.; van Kann, F.; Koh, J. Integrated visions (part I): Methodological framework for long-term regional design. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2012, 20, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motloch, J.L. Introduction to Landscape Design; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Krizek, K.; Forysth, A.; Slotterback, C.S. Is there a role for evidence-based practice in urban planning and policy? Plan. Theory Pract. 2009, 10, 459–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.D.; Corry, R.C. Evidence-based landscape architecture: The maturing of a profession. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 100, 327–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deming, E.M.; Swaffield, S. Landscape Architecture Research: Inquiry, Strategy, Design; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lenzholzer, S.; Brown, R.D. Climate-responsive landscape architecture design education. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 61, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijering, J.V.; Tobi, H.; van den Brink, A.; Morris, F.; Bruns, D. Exploring research priorities in landscape architecture: An international Delphi study. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 137, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, C.; Monoian, E.; Ferry, R. Regenerative Infrastructures: Freshkills Park NYC; Prestel Verlag: Munich, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ozgun, K.; Weir, I.; Cushing, D. Optimal electricity distribution framework for public space: Assessing renewable energy proposals for Freshkills Park, New York City. Sustainability 2015, 7, 3753–3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monoian, E.; Ferry, R. New Energies, Copenhagen; Prestel Verlag: Munich, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Brinkhuijsen, M. Landscape 1:1: A Study of Designs for Leisure in the Dutch Countryside; Wageningen University: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vroom, M.J. Lexicon van de Tuin- en Landschapsarchitectuur; Blauwdruk: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Eo Wijers-Stichting. Eo Wijers-Stichting Doelstelling. Available online: http://www.eowijers.nl/?page_id=1053 (accessed on 7 August 2014).

- De Jonge, J. Een Kwart Eeuw Eo Wijers-Stichting: Ontwerpprijsvraag als Katalysator voor Gebiedsontwikkeling; Habiforum: Gouda, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Eo Wijers-stichting. Eo Wijers-Prijsvraag 2011–2012: Nieuwe Energie voor de Veenkoloniën, op zoek naar Regionale Comfortzones. Brochure voor de Ideeënfase over Krimp, Energietransitie en Ruimtelijke Kwaliteit; Eo Wijers-stichting: Deventer, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lysen, E.H. Trias Energica: Solar Energy Strategies for Developing Countries, Proceedings of the Eurosun Conference Freiburg. Freiburg, Germany, 16–19 September 1996.

- MacKay, D.J.C. Sustainable Energy—Without the Hot Air; UIT Cambridge Ltd.: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tillie, N.; van den Dobbelsteen, A.; Doepel, D.; Joubert, M.; de Jager, W.; Mayenburg, D. Towards CO2 neutral urban planning: Presenting the Rotterdam energy approach and planning (REAP). J. Green Build. 2009, 4, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PBL; ECN. Naar een Schone Economie in 2050: Routes Verkend; Planbureau voor de Leefomgeving and Energy Research Centre of the Netherlands: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Laughton, M. Variable renewables and the grid: An overview. In Renewable Electricity and the Grid; Boyle, G., Ed.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2009; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoorn, A.; Tennekes, J.; van den Wijngaart, R. Quickscan Energie en Ruimte. In Raakvlakken Tussen Energiebeleid en Ruimtelijke Ordening; Planbureau voor de Leefomgeving: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study: Research, Design and Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative & Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, G. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Eo Wijers-Stichting. Eo Wijers-Prijsvraag 2011–2012: Nieuwe Energie voor de Veenkoloniën, op zoek naar Regionale Comfortzones; Jury Report; Eo Wijers-Stichting: Deventer, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- De Zwart, B. A triptich of expertise. The design competition as an instrument to unite assignment, design and commissioner. In Designing for a Region; Meijsmans, N., Ed.; SUN Academia: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- De Waal, R.; Kempenaar, A.; van Lammeren, R.; Stremke, S. Application of social media in a regional design competition: A case study in the Netherlands. In Digital Landscape Architecture 2013; Buhmann, E., Pietsch, M., Ervin, S.M., Eds.; Wichmann Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2013; pp. 186–200. [Google Scholar]

- Loorbach, D.; van der Brugge, R.; Taanman, M. Governance in the energy transition: Practice of transition management in the Netherlands. Int. J. Environ. Technol. Manag. 2008, 9, 294–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olwig, K.R. The earth is not a globe: Landscape versus the ‘globalist’ agenda. Landsc. Res. 2011, 36, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Horst, D.; Vermeylen, S. Local rights to landscape in the global moral economy of carbon. Landsc. Res. 2011, 36, 455–470. [Google Scholar]

- Feddes, Y. Juryverslag Eo Wijers-Prijsvraag; Eo Wijers-Stichting: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Noorman, K.J.; de Roo, G. Energielandschappen: De 3de generatie. Over Regionale Kansen op het Raakvlak van Energie en Ruimte; Provincie Drenthe: Koekange, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).