Improving Stewardship of Marine Resources: Linking Strategy to Opportunity

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Institutional Entrepreneurship

3. Study Design

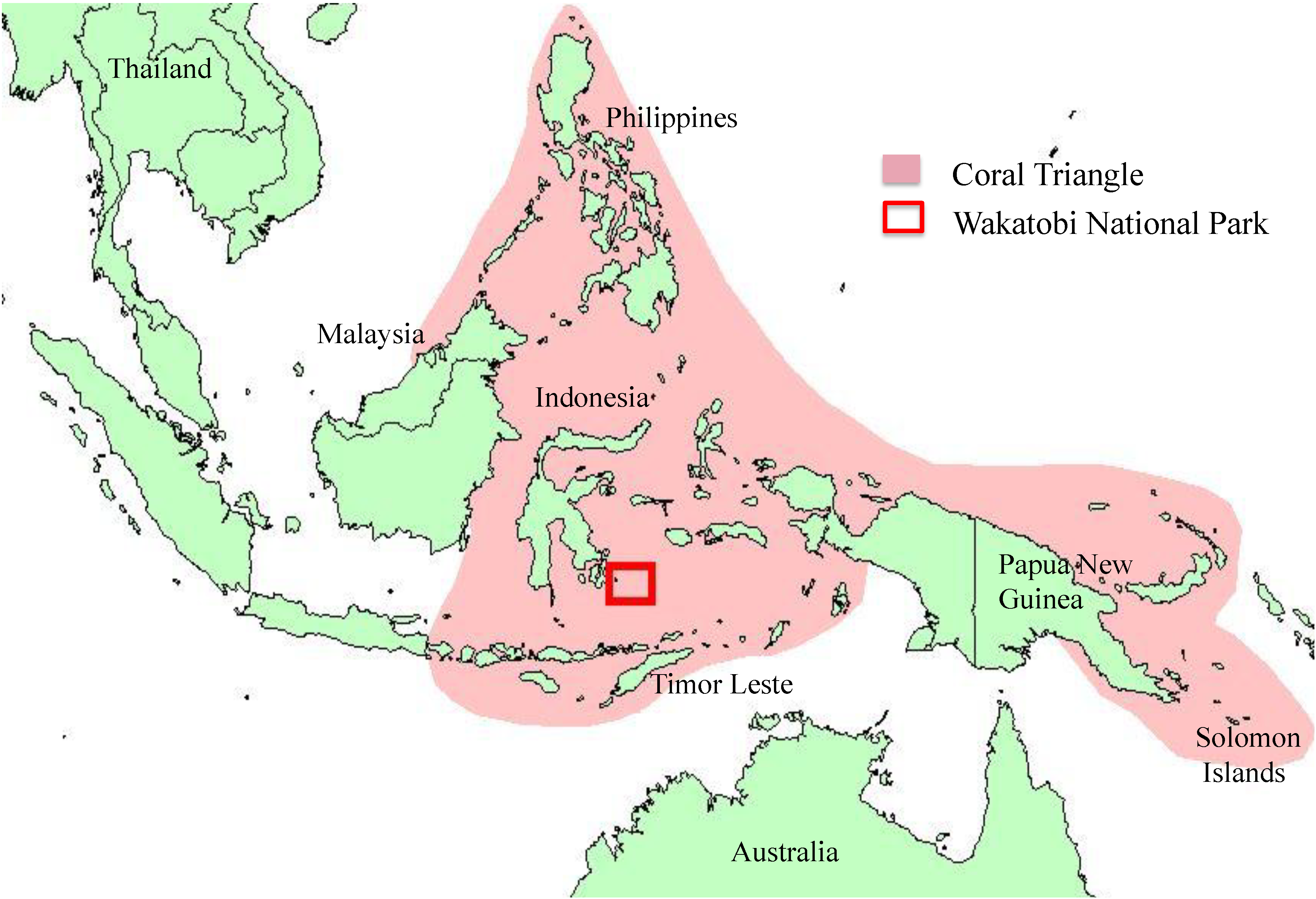

3.1. Research Site and Governance Context

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Analysis

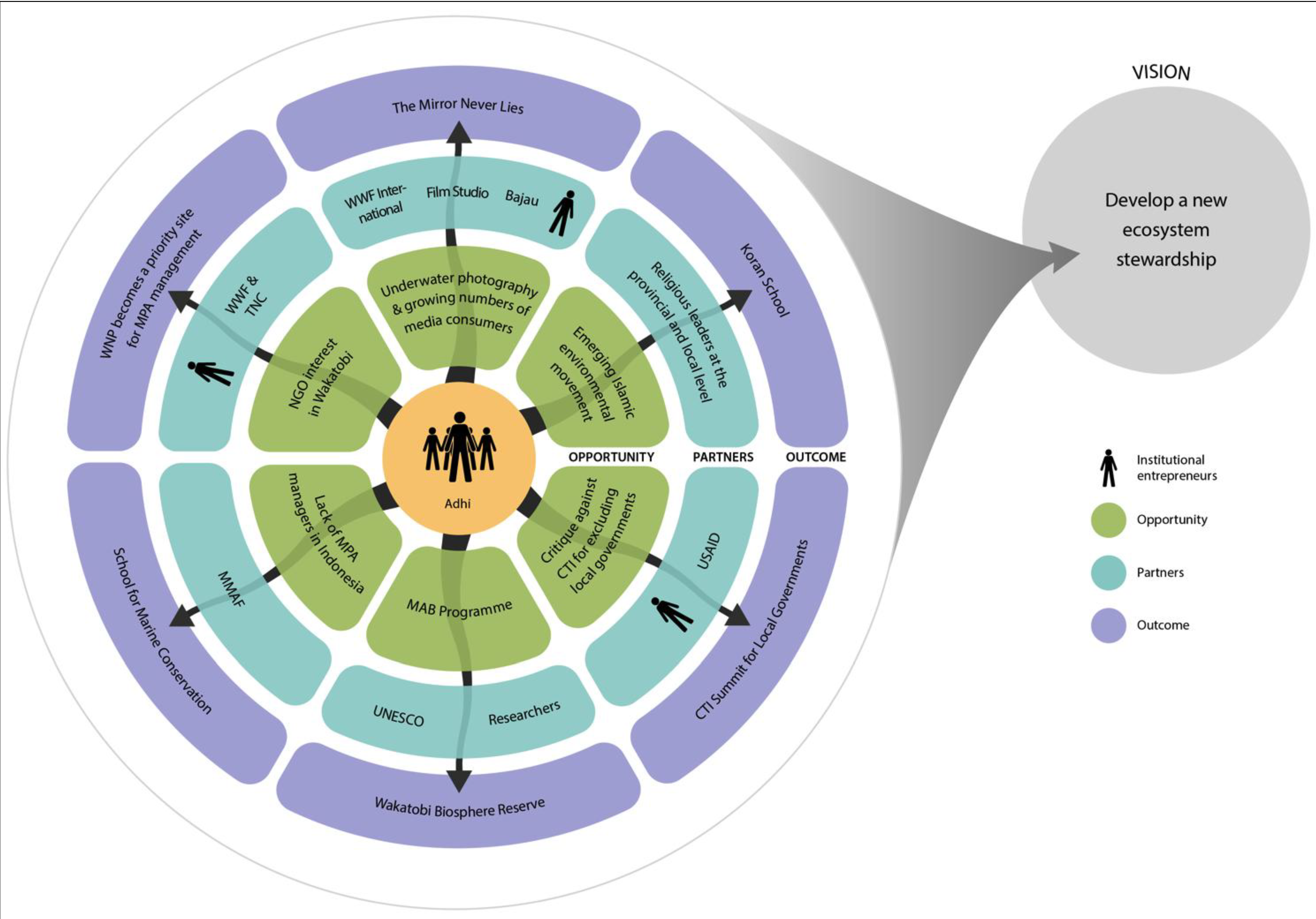

| Vision: Develop a new ecosystem stewardship of the WNP by (1) fostering cultural change, (2) institutionalizing MPA management, and (3) transforming Wakatobi into a high-end tourist destination | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Opportunity | Outcome | District level strategies to reach outcome | Anticipated medium/long term impact |

| NGO interest in the establishment of MPAs in the Coral Triangle | WNP becomes a priority site for MPA management and a key site for the CTI | Informal pact with NGOs to build and market the WNP as a popular marine national park and dive site; Cooperate with NGOs on monitoring/patrolling; Co-production of “The Mirror Never Lies” | Better enforcement of park regulations; Promote marine-based tourism |

| Need for new MPA managers in Indonesia | The establishment of the “School for Marine Conservation” | Cooperative agreement with MMAF to start the school; Lease land to MMAF; Construction of the school building | Support to park management; Provide information to and put pressure on future local policy makers and politician; Promote cultural change among district government authorities and communities |

| UNESCO MAB Program | The creation of the “Wakatobi Biosphere Reserve” | Cooperate with researchers who provide ecological and socio-economic data and help preparing the application; Use existing ecological data by NGOs; Submit application to UNESCO | A new platform for park management where different actors can cooperate; Put pressure on the district government to prioritize marine governance; Help institutionalize MPA management; Attract researchers; Improve collaboration with central government; Support future fundraising |

| Critique against CTI for excluding district governments from the CTI planning and implementation process | The organizing of the “CTI Summit for Local Governments” | Step 1: Pilot a conference on coastal management for Indonesian district leaders; Cooperate with MMAF which provides funds Step 2: Enroll key person in USAID; Cooperate with USAID on a proposal for a Coral Triangle Summit; Key person gets it endorsed and helps with planning and logistics; Issue invitations to the guests | Influence regional policy; Attract future funding for park management; Create strategic alliances with other district governments to support knowledge exchange and learning |

| Emerging Islamic environmental movement | The creation of a new Koran school | Support and encouragement to local religious leaders to take an interest in marine resource management | Change in mental models hindering sustainable use of marine resources; Strengthen emotional attachment to marine resources among local communities |

| Underwater photography and increasing number of media consumers in Indonesia | The co-production of the “The Mirror Never Lies” | Sell the idea of a movie to WWF; WWF facilitates fundraising, helps to contact an Indonesian Film Studio and provides funds; Enroll a Bajau village where the movie can be filmed and where actors can be casted; District government acts as executive producer and sponsors the production; Organize an environmental film festival to promote the movie and raise marine issues; Show the movie at various international film festivals | Use as education material in schools; Raise awareness of marine degradation/conservation among local communities; Create a new partnership between the district government and the Bajau; Promote marine-based tourism |

4. Results: Linking Strategy to Opportunity

4.1. A regional Marine Conservation Portfolio

“When Adhi assumed his position we made an informal agreement with him that together we would make WNP the third most popular marine national park and tenth most popular dive site in Indonesia”.

4.2. Lack of MPA Managers in Indonesia

“We cannot entrust politicians to maintain the ecology. We have to encourage academics to come here to continuously remind us about the importance of our ecology. Leadership will change every 5 years, if not reelected for a second mandate period. There are no guarantees that future politicians will prioritize the marine environment. With the help of the new school we are better enabled to look at things from a long-term perspective and never forget about conservation”.

4.3. US donor Support to the Coral Triangle Initiative (CTI)

“Alone we don’t have enough power, or financial resources, to manage and protect Wakatobi’s marine resources from external threats. The CTI is a political unit that can be linked up with to mobilize such resources. As a pivotal part the CTI more people will pay attention and we need all [the] allies we can get”.

“During the dive Adhi promised himself that the situation would never become as severe [in the Wakatobi] as in the Philippines. The Philippine reefs were depleted and the coral cover was bad. We therefore decided to invite representatives of other local governments to Wakatobi to discuss the situation of coral reefs and come up with a charter on how to preserve them”.

4.4. The Man and the Biosphere Program

“Internally he is quite active. He goes to his staff with the data we provide him with to show them what is happening. With Adhi we don’t need to push the argument very hard because he recognizes that Wakatobi’s future depends on the marine environment”.

4.5. Greening Islam

“A reading of, for example, Moses can help us to understand that the sea is the center of everything and that all life depends upon it, and by using religious symbols we can build protective value for the WNP. People need to take pride in local ecosystem in order to preserve them”.

4.6. Media and Underwater Photography

“Even cosmopolitan urbanites will be hard-pressed not to fall for this exotic gem. Glossily shot in pristine marine locations, every frame is a feast for the eyes. […] this film will be remembered for the breathtaking underwater cinematography that shows the sea teeming with wonders like a parallel universe” [67].

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Appendix

| 1 | Coral Triangle Initiative Secretariat, Jakarta, Indonesia |

| 2 | The Nature Conservancy (TNC), US (Skype) |

| 3 | Wakatobi Regency Government |

| 4 | WWF, Wakatobi |

| 5 | Researcher, Wollongong University, Australia |

| 6 | TNC, Australia |

| 7 | Researcher, James Cook University, Australia |

| 8 | WWF, Jakarta |

| 9 | Regency government, Wakatobi |

| 10 | Regency government, Wakatobi |

| 11 | Researcher, Essex University, Wakatobi |

| 12 | Regency government, Wakatobi |

| 13 | Regency government, Wakatobi |

| 14 | Regency government, Wakatobi |

| 15 | TNC, Bali, Indonesia |

| 16 | TNC, Jakarta |

| 17 | WWF Wakatobi |

| 18 | Tourism operator |

| 19 | Local NGO, Wakatobi |

| 20 | Local NGO Jakarta/consultant USAID |

| 21 | USAID, Jakarta |

| 22 | Central government Indonesia, Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries, Jakarta |

| 23 | Central government Indonesia, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Jakarta |

| 24 | WWF Indonesia, Jakarta |

| 25 | Central government Indonesia, Directorate General Marine, Coasts and Small Islands/Researcher, Jakarta. |

| 26 | WWF, Wakatobi |

| 27 | WWF, Malayisa (Skype) |

| 28 | Wakatobi Regency government, Wakatobi |

| 29 | Highschool student, Wakatobi (ambassador at Sail Wakatobi) |

| 30 | Tourism operator, Wakatobi |

| 31 | Central government Indonesia, Department of Marine Affairs and Fisheries/ Coral Triangle Initiative Secretariat, Jakarta |

| 32 | Central government Indonesia, The Agency of Development Assistance Planning, Jakarta |

| 33 | Asian Development Bank (ADB), Jakarta |

| 34 | ADB, Manila, the Philippines |

| 35 | ADB, Manila |

| 36 | ADB, Jakarta |

| 37 | ADB, Jakarta |

| 38 | Central government the Philippines, Sulu-Celebes Sea Sustainable Fisheries Management, Quezon City, the Philippines |

| 39 | Conservation International, Quezon City |

| 40 | Regency government, Wakatobi |

| 41 | Researcher, Southeast Asian Regional Center for Graduate Study and Research in Agriculture, Los Banos, the Philippines |

| 42 | WorldFish, Los Banos |

| 43 | WWF, Quezon City |

| 44 | Researcher, Marine Science Institute, Quezon City |

| 45 | Regency government, Wakatobi |

| 46 | WWF, Quezon City |

| 47 | US Coral Triangle Initiative Support Partnership, Bangkok, Thailand |

| 48 | United Nations Development Programme, Bangkok |

| 49 | USAID, Bangkok |

| 50 | US Coral Triangle Initiative Support Partnership, Bangkok |

| Background information |

| Location |

| Date |

| Name |

| Title |

| Gender |

| Nationality |

| Thematic areas to be covered |

| -Describe present conservation strategies and concrete activities in the WNP |

| -Impression of park management |

| -Management barriers |

| -Main actors involved in management/governance of the WNP |

| -Relations between different actors |

| -Impression of the present leadership |

| -The role of key individuals (who are they) |

| -Visions for change |

| -Key individuals’ strategies |

| -Links between key individuals, organizations and networks |

| -Major drivers for change in the past and now |

| -Opportunities for change |

| -The role of regional conservation initiatives/activities |

| -Zooming out: The WNP in a broader context |

- Film recording of The Mirror Never Lies, Wakatobi

- UNESCO Man and the Biosphere Meeting, Wakatobi

- Planning meeting for the Coral Triangle Initiative Local Government Summit, Jakarta

- Fish auction, Wanci, Wakatobi, including five interviews with resident individuals working in the market:

- Retailer

- Fisher

- Fisher

- Bajau family

- Fisher

- Diving excursion, Wakatobi

- Diving excursion, Wakatobi

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baker, A.C.; Glynn, P.W.; Riegl, B. Climate change and coral reef bleaching: An ecological assessment of long-term impacts, recovery trends and future outlook. Estuar. Coast. Shelf. Sci. 2008, 80, 435–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, S.C.; Jeffress-Williams, S.; Boesch, D.F. Wicked Challenges at Land’s End: Managing Coastal Vulnerability under Climate Change. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2012, 37, 51–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, T.P. Confronting the global decline of coral reefs. In Loss of Coastal Ecosystems; Duarte, C., Ed.; BBVA Foundation: Madrid, Spain, 2009; pp. 140–166. [Google Scholar]

- Scheffer, M.; Westley, F. Local basis if rigidity: Locks in cells, Minds, and Society. Ecol. Soc. 2007, 12, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson, P.; Gunderson, L.H.; Carpenter, S.R.; Ryan, P.; Lebel, L.; Folke, C.; Holling, C.S. Shooting the rapids: Navigating transitions to adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2006, 11, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Meijerink, S.; Huitema, D. Policy entrepreneurs and change strategies: Lessons from sixteen case studies of water transitions around the globe. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Huitema, D.; Meijerink, S. Realizing water transitions: The role of policy entrepreneurs in water policy change. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, F.; Olsson, P. Institutional entrepreneurs, global networks, and the emergence of international institutions for ecosystem-based management: The Coral Triangle Initiative. Mar. Pol. 2013, 38, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battilana, J.; Leca, B.; Boxenbaum, E. How Actors Change Institutions: Towards a Theory of Institutional Entrepreneurship. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2009, 3, 65–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westley, F.R.; Tjornbo, O.; Schultz, L.; Olsson, P.; Folke, C.; Crona, B.; Bodin, Ö. A theory of transformative agency in linked social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Veron, J.E.N.; Devantier, L.M.; Turak, E.; Green, A.L.; Kininmonth, S.; Stafford-Smith, M.; Peterson, N. Delineating the Coral Triangle. Galaxea J. Cor. Reef Stud. 2009, 11, 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Coral Triangle Initiative Secretariat (CTI Secretariat). Regional Action Plan of Action; Interim Regional CTI Secretariat: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, L.; Reytar, K.; Spalding, M.; Perry, A. Reefs at Risk Revisited in the Coral Triangle; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; p. 72. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, P. Interest and agency in institutional theory. In Institutional Patterns and Organizations: Culture and Environment; Zuker, L.G., Ed.; Ballinger Pub. Co.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1988; pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Garud, R.; Karnoe, P. Distributed agency and interactive emergence. In Innovating Strategy Process; Floyd, S.W., Roos, J., Jacobs, C.D., Kellermanns, F., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 88–96. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, T.; Olsson, P.; Folke, C.; Johansson, K. Trust-building, knowledge generation and organizational innovations: the role of a bridging organization for adaptive co-management of a wetland landscape around Kristianstad, Sweden. Hum. Ecol. 2006, 34, 573–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westley, F.; Olsson, P.; Folke, C.; Homer-Dixon, T.; Vredenburg, H.; Loorbach, D.; Thompson, J.; Nilsson, M.; Lambin, E.; Sendzimir, J.; et al. Tipping Toward Sustainability: Emerging Pathways of Transformation. Ambio 2011, 40, 762–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin, F.S., III; Carpenter, S.R.; Kofinas, G.P.; Folke, C.; Abel, N.; Clark, W.C.; Olsson, P.; Smith-Stafford, D.M.; Walker, B.; Young, O.R.; et al. Ecosystem stewardship: Sustainability strategies for a rapidly changing planet. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2010, 25, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, P.; Folke, C.; Hahn, T. Social-ecological transformation for ecosystem management: The development of adaptive co-management of a wetland landscape in southern Sweden. Ecol. Soc. 2004, 9. Article 2. [Google Scholar]

- Bodin, Ö.; Crona, B.J. Management of natural resources at the community level: Exploring the role of social capital and leadership in a rural fishing community. World Dev. 2008, 36, 2763–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, R.; Westley, F.R.; Carpenter, S.R. Navigating the back loop: fostering social innovation and transformation in ecosystem management. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, D.L.; Scully, M. The institutional entrepreneur as modern prince: The strategic face of power in contested fields. Organ. Stud. 2007, 28, 971–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- True, J.L.; Jones, B.D.; Baumgartner, F.R. Punctuated Equilibrium Theory: Explaining stability and Change in Public Policy Making. In Theories of the Policy Process; Sabatier, P., Ed.; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1999; pp. 97–115. [Google Scholar]

- Dorado, S. Institutional entrepreneurship, partaking, and convening. Organ. Stud. 2005, 26, 385–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley, J.; Baker, D.; Koliba, C.; Matteson, R.; Mills, R.; Pittman, J. Opening the policy window for ecological economics: Katrina as a focusing event. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 63, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, P.; Folke, C.; Hughes, T. Navigating the transition to ecosystem-based management of the Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 9489–9494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, S.; Hardy, C.; Lawrence, T. Institutional entrepreneurship in emerging fields: HIV/AIDS treatment advocacy in Canada. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 657–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhl-Bien, M. Relational Leadership Theory: Exploring the Social Processes of Leadership and Organizing. Leader. Q. 2006, 17, 654–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhl-Bien, M.; Russ, M.; McKelvey, B. Complexity Leadership Theory: Shifting Leadership from the Industrial Age to the Knowledge Era. Leader. Q. 2007, 18, 298–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, B.B.; Plowman, D.A. The leadership of emergence: A complex systems leadership theory of emergence at successive organizational levels. Leader. Q. 2009, 20, 617–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, B.B.; Uhl-Bien, M.; Russ, M.; Seers, A.; Orton, D.J.; Schreiber, C. Complexity leadership theory: An interactive perspective on leading in complex adaptive systems. Leader. Q. 2006, 8, 2–12. [Google Scholar]

- Clifton, J. Science, funding and participation: Key issues for marine protected area networks and the Coral Triangle Initiative. Environ. Conservat. 2009, 36, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, L.; Green, A.; Tanzer, J.; White, A. Biophysical Principles for Designing Resilient Networks of Marine Protected Areas to Integrate Fisheries, Biodiversity and Climate Change Objectives in the Coral Triangle; The Nature Conservancy: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Von Heland, F.; Clifton, J. Whose threat counts? Conservation narratives in the Wakatobi National Park. Conservat. Soc. 2014, in press. [Google Scholar]

- The Nature Conservancy (TNC). Annual Report; The Nature Conservancy: Arlington, MA, USA, 2009. Available online: http://www.nature.org/about-us/our-accountability/annual-report/index.htm (accessed on 1 November 2013).

- Clifton, J.; Unsworth, R.K.F.; Smith, D.J. Marine Research and Conservation in the Coral Triangle: The Wakatobi National Park; Nova: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wijonarno, A. Perspective: When NGOs Invest Long-term in an MPA’s Management. MPA News. Int. News Anal. Mar. Protected Area. 2012, 14, 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, G.B.; Mitchell, B.; Wiltshire, A.; Manan, A.; Wismer, S. Community participation in marine protected area management: Wakatobi National Park, Sulawesi, Indonesia. Coast. Manag. 2001, 29, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, M. Folk taxonomy of reef fish and the value of participatory monitoring in Wakatobi National Park, Southeast Sulawesi, Indonesia. Trad. Mar. Resour. Manag. Know. Info. B. 2005, 18, 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen, L. Marine resource dependence, resource use patterns and identification of economic performance criteria within a small island community: Kaledupa, Indonesia. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Essex, Essex, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pilgrim, S.; Cullen, L.; Smith, D.; Pretty, J. Hidden harvest or hidden revenue: Local resource use in a remote region of Southeast Sulawesi, Indonesia. Indian J. Trad. Know. 2007, 6, 150–159. [Google Scholar]

- Unsworth, R.K.F.; Smith, D.J.; Powell, A.; Hukon, F. The ecology of Indo-Pacific grouper (Serranidae) species and the effects of a small scale no take area on grouper assemblage, abundance and size frequency distribution. Mar. Biol. 2007, 1152, 243–254. [Google Scholar]

- Haapkylä, J.; Unsworth, R.K.F.; Seymour, A.S.; Melbourne-Thomas, J.; Flavell, M.; Willis, L.B.; Smith, D.J. Spatio-temporal coral disease dynamics in the Wakatobi Marine National Park, South-East Sulawesi, Indonesia. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 2009, 87, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifton, J. Compensation, conservation, and communities: An analysis of direct payments initiatives within an Indonesian marine protected area. Environ. Conservat. 2013, 40, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitrani, F.; Hofman, B.; Kaiser, K. Unity in Diversity? The Creation of New Local Governments in a Decentralising Indonesia. B. Indo. Econ. Stud. 2005, 41, 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, C.R. Mixed outcomes: The impact of regional autonomy and decentralization on indigenous ethnic minorities in Indonesia. Dev. Change 2007, 38, 711–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WWF/TNC. Rapid Ecological Assessment Wakatobi National Park; Worldwide Fund for Nature: Bali, Indonesia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Green, S.; Meneses, B.T.; Christine, P.; White, A.T.; Kilarski, S. MPA Networks in the Coral Triangle: Development and Lessons; The Coral Triangle Support Partnership: Cebu, Philippines, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- McMellor, S.; Smith, D. Coral reefs of the Wakatobi: Abundance and biodiversity. In Marine Conservation and Research in the Coral Triangle: The Wakatobi National Park; Clifton, J., Unsworth, K.F., Smith, D., Eds.; Nova: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 18–32. [Google Scholar]

- Clifton, J. Refocusing conservation through a cultural lens: Improving governance in the Wakatobi National Park, Indonesia. Mar. Pol. 2013, 41, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaynor, J.L. Flexible fishing: Gender and the new spatial division of labor in eastern Indonesia’s rural littoral. Radical Hist. Rev. 2010, 107, 74–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acciaioli, G. ‘Archipelagic culture’ as an exclusionary government discourse in Indonesia. Asia Pac. J. Anthropol. 2001, 2, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holstein, J.; Gubrium, J. The Active Interview: Qualitative Research Methods Series; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Alvesson, M. Beyond Now-Positivists, Romantics and Localists—A Reflexive Approach to Interviews in Organizational Research; Institute of Economic Research Working Paper Series; Lund University: Lund, Sweden, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, S.; Brinkmann, S. Interviews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, N.; Stern, L.W.; Anderson, J.C. Conducting interorganizational research using key informants. Acad. Manag. J. 1993, 36, 1633–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, H.R. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches; AltaMira Press: Lanham, MD, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Green, A.; White, A.; Tanzer, J. Integrating Fisheries, Biodiversity, and Climate Change Objectives into Marine Protected Area Network Design in the Coral Triangle; The Coral Triangle Support Partnership: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Manila Bulletin. Coral Triangle Privatization Plan Opposed. Available online: http://www.mb.com.ph/articles/358659/coral-triangle-privatization-plan-opposed (accessed on 7 December 2012).

- USCTISP (US Coral Triangle Support Partnership). Activity Report: CTI Mayors’ Roundtable; US Coral Triangle Initiative Support Program; USCTISP: Bangkok, Thailand, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Biosphere Reserves—Learning Sites for Sustainable Development. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/natural-sciences/environment/ecological-sciences/biosphere-reserves/ (accessed on 21 March 2013).

- UNESCO. 20 new Biosphere Reserves added to UNESCO’s Man and the Biosphere (MAB) Program. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/media-services/single-view/news/20_new_biosphere_reserves_added_to_unescos_man_and_the_biosphere_mab_program (accessed on 21 March 2013).

- Hill, H.; Resosudarmo, B.P.; Vidyattana, Y. Indonesia’s changing economic geography. B. Indo. Econ. Stud. 2008, 44, 407–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veen, R.T. Poverty and the environment. Available online: http://www.ifees.org.uk (accessed on 31 March 2013).

- Shomali, M. Aspects of Environmental Ethics: An Islamic Perspective. Available online: http://www.thinkingfaith.org/articles/20081111_1.htm (accessed on 15 July 2014).

- Nasr, H.S. Man and Nature. The Spiritual Crisis of Modern Man; ABC International Group, INC: Chicago, IL, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M. The Mirror Never Lies: Busan Film Review: Hollywood Reporter. Available online: http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/review/mirror-never-lies-film-review-245620 (accessed on 9 May 2014).

- Geertz, C. The Interpretation of Cultures; Fontana Press: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport, A. Ritual and Religion in the Making of Humanity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Clifton, J.; Majors, C. Culture, Conservation, and Conflict: Perspectives on Marine Protection among the Bajau of Southeast Asia. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2012, 25, 716–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westley, F. Bob Geldof and Live Aid: The Affective Side of Global Social Innovation. Hum. Rel. 1991, 4, 1011–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, R. Who is the World? Reflections on Music and Politics Twenty Years after Live Aid. J. Pop. Music Stud. 2005, 17, 324–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchant, C. Radical Ecology: The Search for a Livable World; Routledge: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- AtKisson, A. The Sustainability Transformation: How to Accelerate Positive Change in Challenging Times; Earthscan: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Christie, P. Marine protected areas as biological successes and social failures in southeast Asia. In Aquatic Protected Areas as Fisheries Management Tools: American Fisheries Society Symposium 42; Shipley, J.B., Ed.; American Fisheries Society: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004; pp. 155–164. [Google Scholar]

- Suddaby, R.; Greenwood, R. Rhetorical strategies of legitimacy. Admin. Sci. Q. 2005, 50, 35–67. [Google Scholar]

- Antadze, N.; Westley, F. Funding Social Innovation: How Do We Know What to Grow. Philanthropist 2010, 23, 343–356. [Google Scholar]

- Westley, F. The devil in the dynamics: Adaptive management on the front lines. In Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems; Gunderson, L., Holling, C.S., Eds.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; pp. 333–360. [Google Scholar]

- Mansuri, G.; Rao, V. Evaluating Community Driven Development: A Review of the Evidence; The World Bank Development Research Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Clifton, J. Evaluating contrasting approaches to marine ecotourism: “Dive tourism” and “research tourism” in the Wakatobi Marine National Park, Indonesia. In Contesting the Foreshore: Tourism, Society and Politics on the Coast; Boissevain, J., Selwyn, T., Eds.; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 151–168. [Google Scholar]

- Ellerman, D. Should development agencies have official views? Dev. Pract. 2002, 12, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernstson, H.; Sörlin, S. Weaving Protective Stories: Connective Practices to Articulate Holistic Values in the Stockholm National Urban Park. Environ. Plan. A 2009, 41, 1460–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platteau, J.-P. Monitoring Elite Capture in Community-Driven Development. Dev. Change 2004, 35, 223–246. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory of Mass Communication. Media Psychol. 2001, 3, 265–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drath, W. The Deep Blue Sea: Rethinking the Source of Leadership; Jossey-Bass and Center for Creative Leadership: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ernstson, H. Transformative collective action: A network approach to transfor-mative change in ecosystem-based management. In Social Networks and Natural Resource Management: Uncovering the Social Fabric of Environmental Governance; Bodin, Ö., Prell, C., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 255–287. [Google Scholar]

- Breulin, R.; Regis, H.A. Putting the Ninth Ward on the Map: Race, Place, and Transformation in Desire, New Orleans. Am. Anthropol. 2006, 108, 744–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifton, J. Prospects for Co-management in Indonesia’s Marine Protected Areas. Mar. Pol. 2003, 27, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferse, S.C.A.; Costa, M.M.; Manez, S.K.; Adhuri, D.S.; Glaser, M. Allies, not aliens: Increasing the role of local communities in marine protected area implementation. Environ. Conservat. 2010, 37, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosius, P. Analyses and Interventions: Anthropological Engagements with Environmentalism. Curr. Anthropol. 1991, 40, 277–310. [Google Scholar]

- Kortschak, I. Invisible people. Poverty and empowerment in Indonesia; Indonesia’s National Program for Community Development: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Von Heland, F.; Clifton, J.; Olsson, P. Improving Stewardship of Marine Resources: Linking Strategy to Opportunity. Sustainability 2014, 6, 4470-4496. https://doi.org/10.3390/su6074470

Von Heland F, Clifton J, Olsson P. Improving Stewardship of Marine Resources: Linking Strategy to Opportunity. Sustainability. 2014; 6(7):4470-4496. https://doi.org/10.3390/su6074470

Chicago/Turabian StyleVon Heland, Franciska, Julian Clifton, and Per Olsson. 2014. "Improving Stewardship of Marine Resources: Linking Strategy to Opportunity" Sustainability 6, no. 7: 4470-4496. https://doi.org/10.3390/su6074470

APA StyleVon Heland, F., Clifton, J., & Olsson, P. (2014). Improving Stewardship of Marine Resources: Linking Strategy to Opportunity. Sustainability, 6(7), 4470-4496. https://doi.org/10.3390/su6074470