Are Green Taxes a Good Way to Help Solve State Budget Deficits?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Economic Literature on Externalities and the “Double Dividend”

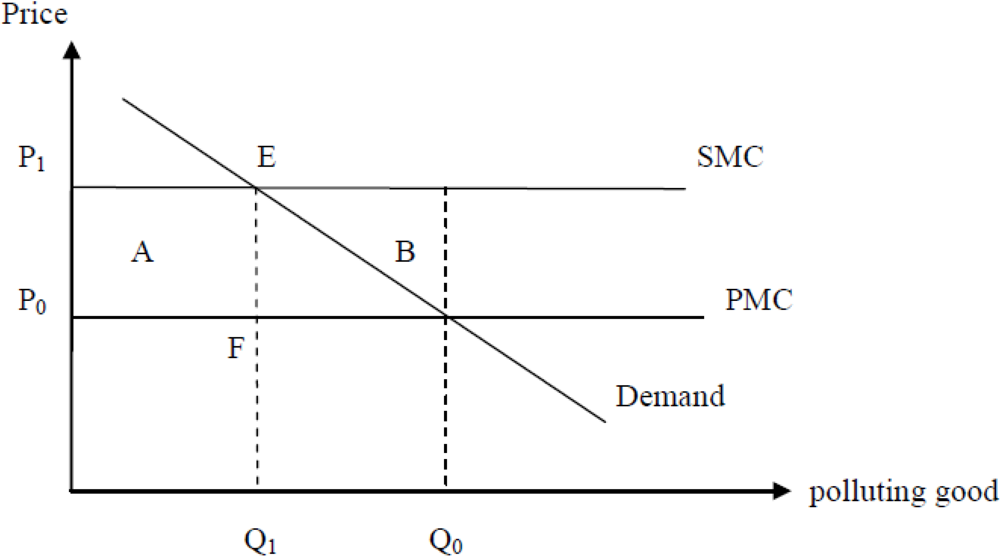

2.1. Internalizing Externalities

2.2. The Double Dividend from Environmental Taxes

3. Basic Model for Double Dividend of Environmental Taxes and the Effect of Tax Bases

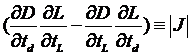

3.1. Decomposition of the Effects of Environmental Taxes

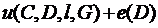

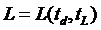

, where the labor productivity

, where the labor productivity  is constant. Based on their assumption that

is constant. Based on their assumption that  is constant through time, we further modify the model such that the labor productivity is normalized to unity. Thus, we write the production possibilities as:

is constant through time, we further modify the model such that the labor productivity is normalized to unity. Thus, we write the production possibilities as: (1)

(1) in Equation (1) can be viewed as the efficiency units of labor. The purpose of this modification is just to simplify the calculations below and represent the results in a more succinct way. It does not affect the basic conclusions.

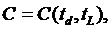

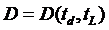

in Equation (1) can be viewed as the efficiency units of labor. The purpose of this modification is just to simplify the calculations below and represent the results in a more succinct way. It does not affect the basic conclusions. and

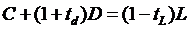

and  , respectively. The government’s budget constraint is thus given by:

, respectively. The government’s budget constraint is thus given by: (2)

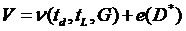

(2) ). The time endowment is

). The time endowment is  . The utility function of the representative consumer is given by

. The utility function of the representative consumer is given by (3)

(3) is quasi-concave and continuous. The separability assumption embodied in Equation (3) simplifies the analysis but is not essential for the basic results. Environmental quality is a decreasing function of the aggregate consumption of the dirty good.

is quasi-concave and continuous. The separability assumption embodied in Equation (3) simplifies the analysis but is not essential for the basic results. Environmental quality is a decreasing function of the aggregate consumption of the dirty good.  represents the disutility from pollution, where

represents the disutility from pollution, where  . Note that when the consumer make decisions, he takes

. Note that when the consumer make decisions, he takes  in the disutility part as exogenously given, as he does not consider the negative external effect of his dirty consumption on the quality of the environment. Under the perfect competition assumption, the equilibrium wage rate equals the marginal product of labor and thus it is also equal to one. In addition, the prices of the commodities equal their marginal costs, which are normalized to unity, as noted above. Thus, the budget constraint of the consumer is given by

in the disutility part as exogenously given, as he does not consider the negative external effect of his dirty consumption on the quality of the environment. Under the perfect competition assumption, the equilibrium wage rate equals the marginal product of labor and thus it is also equal to one. In addition, the prices of the commodities equal their marginal costs, which are normalized to unity, as noted above. Thus, the budget constraint of the consumer is given by (4)

(4)

and

and  (5)

(5) (6)

(6) and

and  (7)

(7) is the marginal utility of income.

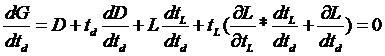

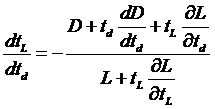

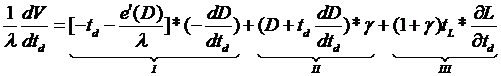

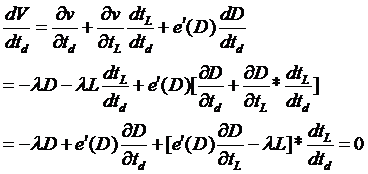

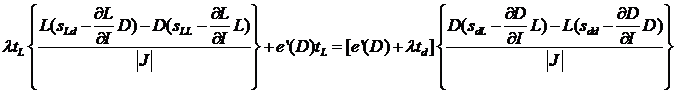

is the marginal utility of income. and setting the resulting expression equal to zero (since the change in the environmental tax is assumed to be revenue-neutral) yields:

and setting the resulting expression equal to zero (since the change in the environmental tax is assumed to be revenue-neutral) yields: (8)

(8) (9)

(9) (10)

(10) (11)

(11) ). The numerator is the loss of welfare (or the increase in the efficiency cost) from the marginal increase in the labor income tax rate (tax rate times the marginal reduction in labor supply). Most empirical studies of labor supply find that the uncompensated elasticity is positive, e.g., Hausman [24], implying that the numerator is positive in general. Assuming the labor tax rate is not high enough to be on the downward-sloping part of its Laffer curve, the denominator is positive. While

). The numerator is the loss of welfare (or the increase in the efficiency cost) from the marginal increase in the labor income tax rate (tax rate times the marginal reduction in labor supply). Most empirical studies of labor supply find that the uncompensated elasticity is positive, e.g., Hausman [24], implying that the numerator is positive in general. Assuming the labor tax rate is not high enough to be on the downward-sloping part of its Laffer curve, the denominator is positive. While  is generally positive, we cannot determine whether it is bigger or smaller than one, which depends on the magnitude of the elasticity of the labor supply.

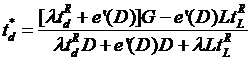

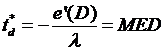

is generally positive, we cannot determine whether it is bigger or smaller than one, which depends on the magnitude of the elasticity of the labor supply. (12)

(12) (13)

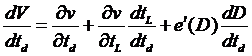

(13) and its marginal social cost

and its marginal social cost  , multiplied by the reduction in dirty goods consumption. Part II is the “revenue recycling effect”. When the total revenue from the environmental tax (

, multiplied by the reduction in dirty goods consumption. Part II is the “revenue recycling effect”. When the total revenue from the environmental tax (  ) is used to reduce the distortionary tax on labor income, the total reduction in the efficiency cost is the change in total revenue from the environmental tax times the marginal excess burden (or marginal efficiency cost) of one additional dollar of revenue from the labor income tax. The remaining part III is the “tax interaction effect” (or interdependency effect). It contains two terms. The first term,

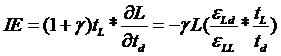

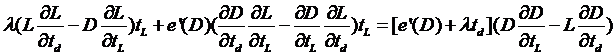

) is used to reduce the distortionary tax on labor income, the total reduction in the efficiency cost is the change in total revenue from the environmental tax times the marginal excess burden (or marginal efficiency cost) of one additional dollar of revenue from the labor income tax. The remaining part III is the “tax interaction effect” (or interdependency effect). It contains two terms. The first term,  , shows the negative effect of the environmental tax on labor supply. The environmental tax increases the cost of production and leads to general increase in the goods prices, which reduces the real wage and discourages labor supply. The second term

, shows the negative effect of the environmental tax on labor supply. The environmental tax increases the cost of production and leads to general increase in the goods prices, which reduces the real wage and discourages labor supply. The second term  is the marginal efficiency cost of labor tax revenue times the reduction of labor tax revenue. These two terms imply that when there are pre-existing distortions in the tax system, the interaction between environmental taxes and labor income taxes is another source of additional excess burden, i.e., the environmental tax tends to exacerbate pre-existing tax distortions.

is the marginal efficiency cost of labor tax revenue times the reduction of labor tax revenue. These two terms imply that when there are pre-existing distortions in the tax system, the interaction between environmental taxes and labor income taxes is another source of additional excess burden, i.e., the environmental tax tends to exacerbate pre-existing tax distortions.3.2. Optimal Level of Environmental Tax

(14)

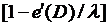

(14) is negative. In general, the sum of the first two terms can be expected to dominate the last term when

is negative. In general, the sum of the first two terms can be expected to dominate the last term when  is very small (e.g., when

is very small (e.g., when  ), implying that the total welfare gain is positive, i.e., a marginal increase in the environmental tax from zero is welfare improving.

), implying that the total welfare gain is positive, i.e., a marginal increase in the environmental tax from zero is welfare improving. becomes large enough, the consumption of dirty goods will be reduced below the efficient level, implying that a further marginal increase in

becomes large enough, the consumption of dirty goods will be reduced below the efficient level, implying that a further marginal increase in  would reduce total welfare, i.e., term I in Equation (13) would become negative. Moreover, if the tax rate

would reduce total welfare, i.e., term I in Equation (13) would become negative. Moreover, if the tax rate  is sufficiently large, it will lie on the downward-sloping part of the Laffer curve of the environmental tax. In this case, an increase in the tax rate

is sufficiently large, it will lie on the downward-sloping part of the Laffer curve of the environmental tax. In this case, an increase in the tax rate  would reduce the total revenue from the environmental tax, thereby making the revenue-recycling effect (term II) negative. Since the third term is always negative, when the tax rate is already large enough, a marginal increase in

would reduce the total revenue from the environmental tax, thereby making the revenue-recycling effect (term II) negative. Since the third term is always negative, when the tax rate is already large enough, a marginal increase in  will unambiguously reduce total welfare.

will unambiguously reduce total welfare. (15)

(15) and

and  are the corresponding tax rates on labor income and dirty commodity, respectively, that would be optimal if the only objective were to raise revenue, i.e., in the absence of the pollution externality. Substituting the government budget constraint (Equation (2)) into Equation (15) and solving for the optimal tax rate for the dirty good yields:

are the corresponding tax rates on labor income and dirty commodity, respectively, that would be optimal if the only objective were to raise revenue, i.e., in the absence of the pollution externality. Substituting the government budget constraint (Equation (2)) into Equation (15) and solving for the optimal tax rate for the dirty good yields: (16)

(16) equal to zero in Equation (15), which implies that in this case:

equal to zero in Equation (15), which implies that in this case: (17)

(17)3.3. The Effect of the Relative Size of Tax Bases and the Corresponding Tax Revenues

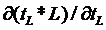

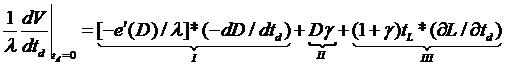

(18)

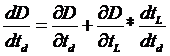

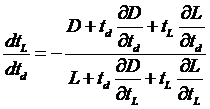

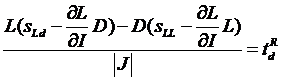

(18) on the total revenue from taxation of the dirty good. The second term shows the feedback effect of the corresponding change in

on the total revenue from taxation of the dirty good. The second term shows the feedback effect of the corresponding change in  on the consumption of the dirty good. It implies that the reduction in

on the consumption of the dirty good. It implies that the reduction in  (due to the introduction of the environmental tax) makes the opportunity cost of leisure increase; consumers will thus decrease their demand for leisure and increase their demand for the dirty good. According to Parry [22], this feedback effect is relatively small as long as the percentage change in

(due to the introduction of the environmental tax) makes the opportunity cost of leisure increase; consumers will thus decrease their demand for leisure and increase their demand for the dirty good. According to Parry [22], this feedback effect is relatively small as long as the percentage change in  is small and can thus be ignored. Equation (10) implies that the change in

is small and can thus be ignored. Equation (10) implies that the change in  is small when the tax base of the dirty good is relatively small, and thus the proportionate change in

is small when the tax base of the dirty good is relatively small, and thus the proportionate change in  is small. Following the argument by Parry [22], we also ignore this feedback effect here and in addition treat

is small. Following the argument by Parry [22], we also ignore this feedback effect here and in addition treat  as a constant. Then Equation (18) can be simplified as:

as a constant. Then Equation (18) can be simplified as: (19)

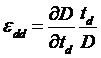

(19) is the uncompensated elasticity of demand for the dirty good with respect to the tax rates

is the uncompensated elasticity of demand for the dirty good with respect to the tax rates  .

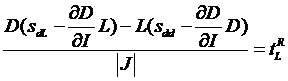

. (20)

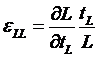

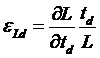

(20) and

and  are the uncompensated elasticities of labor supply with respect to the tax rates

are the uncompensated elasticities of labor supply with respect to the tax rates  and

and  , respectively.

, respectively. (21)

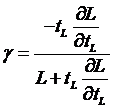

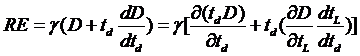

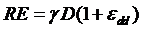

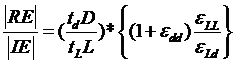

(21) ), the smaller

), the smaller  will be, i.e., the more likely it will be that the revenue recycling effect RE is less than the interaction effect IE, implying that a double dividend does not exist.

will be, i.e., the more likely it will be that the revenue recycling effect RE is less than the interaction effect IE, implying that a double dividend does not exist.4. Using Environmental Taxes to Raise Revenue: The Case of Connecticut

4.1. Carbon Tax

| Fuel types | CO2 emission (%) | Increase in fuel price | Tax revenue (million dollars) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without behavioral response | With behavioral response | |||

| Coal | 11.29 | $26/short ton | 56.2 | 48.4 |

| Crude oil | 65.35 | $5.85/barrel | 325.3 | 322.8 |

| Natural gas | 23.36 | $0.68/mcf | 116.3 | 115.2 |

| Total | 497.8 | 486.4 | ||

4.2. Gas-Guzzler Taxes

| Mpg | U.S. | Hartford |

|---|---|---|

| Less than 18 | 16.90% | 12.50% |

| 18 to 21 | 22.35% | 18.06% |

| 21 to 25 | 36.68% | 30.40% |

| Above 25 | 32.96% | 39.04% |

| Mpg | Estimated Total Sales |

|---|---|

| Less than 18 | 32551 |

| 18 to 21 | 47003 |

| 21 to 25 | 79143 |

| More than 25 | 101621 |

| Mpg | Tax 1 | Tax 2 | Tax 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Less than 18 | $100 | $100 | $2500 |

| 18 to 21 | $100 | $100 | $1500 |

| 21 to 25 | 0 | $100 | $500 |

| More than 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Estimated revenue (million dollars) | 7.96 | 15.87 | 191.45 |

4.3. Comparison of Environmental and Other Taxes

| Tax | Tax Revenue |

|---|---|

| Personal income tax | 6,585.85 |

| Sales and use taxes | 3,205.43 |

| Carbon tax (without behavioral response) | 497.8 |

| Carbon tax (with behavioral response) | 486.4 |

| Gas-guzzler: Tax 1 | 8.0 |

| Gas-guzzler: Tax 2 | 15.9 |

| Gas-guzzler: Tax 3 | 191.5 |

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Connecticut FY2012–FY2013 Biennium Governor’s Budget; Connecticut Office of Policy and Management: Hartford, CT, USA. Available online: http://www.ct.gov/opm/cwp/view.asp?a= 2958&q=473908 (accessed on 28 December 2011).

- Summary of Tax Provisions Contained in 2011 Conn. Pub. Acts 6; Connecticut Department of Revenue Services: Hartford, CT, USA. Available online: http://www.ct.gov/drs/cwp/ view.asp?A=1514&Q=480936 (accessed on 28 December 2011).

- Ekins, P. European environmental taxes and charges: Recent experience, issues and trends. Ecolog. Econ. 1999, 31, 39–62. [Google Scholar]

- Sterner, T.; Köhlin, G. Environmental taxes in Europe. Public Finan. Manag. 2003, 3, 117–142. [Google Scholar]

- Oates, W.E. Pollution Charges as a Source of Public Revenues. In Economic Progress and Environmental Concerns; Giersch, H., Ed.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 1993; pp. 135–152. [Google Scholar]

- Nordhaus, W.D. Carbon taxes to move toward fiscal sustainability. Econ. Voice 2010, 7, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Executive Summary: Effectiveness and Efficiency Reports (Submitted to the 82nd Texas Legislature); Texas Legislative Budget Board: Austin, TX, USA, 2011; p. 65.

- Franchot, P. Consolidated Revenue Report 2010; Comptroller of Maryland: Annapolis, MA, USA. Available online: http://www.marylandtaxes.com/finances/revenue/detailed.asp (accessed on 5 March 2011).

- Actions & Proposals to Balance the FY 2011 Budget: Misc Taxes & Fees & Other Revenue Measures; The National Conference of State Legislatures, Survey of State Legislative Fiscal Offices: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. Available online: http://www.ncsl.org/?tabid=19656 (accessed on 1 February 2011).

- Kay, J.A. The deadweight loss from a tax system. J. Public Econ. 1980, 13, 111–119. [Google Scholar]

- Baumol, W.J.; Oates, W.E. The Theory of Environmental Policy, 2nd ed; Cambridge University: Cambridge, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Fullerton, D.; Leicester, A.; Smith, S. Environmental Taxes. In Dimensions of Tax Design; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Oates, W.E. Green taxes: Can we protect the environment and improve the tax system at the same time? Southern Econ. J. 1995, 61, 915–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosquet, B. Environmental tax reform: Does it work? A survey of the empirical evidence. Ecol. Econ. 2000, 34, 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ekins, P.; Barker, T. Carbon taxes and carbon emissions trading. J. Econ. Surv. 2001, 15, 325–376. [Google Scholar]

- Goulder, L.H. Environmental taxation and the double dividend: A reader’s guide. Int. Tax Public Finan. 1995, 2, 157–183. [Google Scholar]

- Shackleton, R.; Shelby, M.; Cristofaro, A.; Brinner, R.; Yanchar, J.; Goulder, L.H.; Jacobsen, M.; Wilcoxen, P.J.; Pauly, P.; Kaufmann, R. The Efficiency Value of Carbon Tax Revenues. In Energy Modeling Forum; Terman Engineering Center, Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Tullock, G. Excess benefit. Water Resour. Res. 1967, 3, 643–644. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, D. The role of carbon taxes in adjusting to global warming. Econ. J. 1991, 101, 938–948. [Google Scholar]

- Bovenberg, A.L.; de Mooij, R.A. Environmental levies and distortionary taxation. Am. Econ. Rev. 1994, 84, 1085–1089. [Google Scholar]

- Goulder, L.H. Effects of carbon taxes in an economy with prior distortions: An intertemporal general equilibrium analysis. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 1995, 29, 271–297. [Google Scholar]

- Parry, I.W.H. Pollution taxes and revenue recycling. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 1995, 29, S64–S77. [Google Scholar]

- Parry, I.W.H. Tax Deductible Spending, Environmental Policy, and the “Double Dividend” Hypothesis; Discussion Paper 99-24. Resources for the future: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hausman, J.A. Taxes and Labor Supply. In Handbook of Public Economics; Auerbach, A.J., Feldstein, M.S., Eds.; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1985; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Nordhaus, W.D. Optimal greenhouse-gas reductions and tax policy in the ‘DICE’ model. Am. Econ. Rev. 1993, 83, 313–317. [Google Scholar]

- Bento, A.M.; Jacobsen, M. Ricardian rents, environmental policy and the ‘double-dividend’ hypothesis. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2007, 53, 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Bayindir-Upmann, T. On the double dividend under imperfect competition. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2004, 28, 169–194. [Google Scholar]

- Anger, N.; Böhringer, C.; Löschel, A. Paying the piper and calling the tune? A meta-regression analysis of the double-dividend hypothesis. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 1495–1502. [Google Scholar]

- Patuelli, R.; Nijkamp, P.; Pels, E. Environmental tax reform and the double dividend: A meta-analytical performance assessment. Ecol. Econ. 2005, 55, 564–583. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgenson, D.W.; Wilcoxen, P.J. Reducing U.S. carbon emissions: An econometric general equilibrium assessment. Resour. Energy Econ. 1993, 15, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackleton, R.; Shelby, M.; Cristofaro, A.; Brinner, R.; Yanchar, J.; Goulder, L.H.; Jacobsen, M.; Wilcoxen, P.J.; Pauly, P. The Efficiency Value of Carbon Tax Revenues; Draft manuscipt. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washinton, DC, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, A.; Larsen, B. Carbon Taxes, the Greenhouse Effect and Developing Countries; World Bank Policy Research Working Paper Series No. 957. World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ekins, P.; Summerton, P.; Thoung, C.; Lee, D. A major environmental tax reform for the UK: Results for the economy, employment and the environment. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2011, 50, 447–474. [Google Scholar]

- Lutz, C.; Meyer, B. Environmental tax reform in the European Union: Impact on CO2 emissions and the economy. Z. Energiewirtsch. 2010, 34, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Moe, T. Norwegian Climate Policies 1990–2010: Principles, Policy Instruments and Political Economy Aspects; CICERO Policy Note 2010:03. Center for International Climate and Environmental Research (CICERO): Blindern, Norway, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Schöb, R. The Double Dividend Hypothesis of Environmental Taxes: A Survey; CESifo Working Paper Series No. 946. Freie University, Center for Economic Studies and Ifo Institute for Economic Research: Berlin, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Goulder, L.H. Do the Costs of a Carbon Tax Vanish when Interactions with Other Taxes Are Accounted for?; Working Paper No.4061. U.S. National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Bovenberg, A.L.; Goulder, L.H. Optimal environmental taxation in the presence of other taxes: General equilibrium analyses. Am. Econ. Rev. 1996, 86, 985–1000. [Google Scholar]

- Agliardi, E.; Sereno, L. The effects of environmental taxes and quotas on the optimal timing of emission reductions under Choquet-Brownian uncertainty. Econ. Model. 2011, 28, 2793–2802. [Google Scholar]

- Coria, J. Taxes, permits, and the diffusions of a new technology. Resour. Energy Econ. 2009, 31, 249–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero, J.P. Permits, standards, and technology innovation. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2002, 44, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero, J.P. Market structure and environmental innovation. J. Appl. Econ. 2002, 5, 293–325. [Google Scholar]

- van Soest, D. The impact of environmental policy instruments on the timing of adoption of energy-saving technologies. Resour. Energy Econ. 2005, 27, 235–247. [Google Scholar]

- Parry, I.W.H.; Williams, R.C., III; Goulder, L.H. When Can Carbon Abatement Policies Increase Welfare? The Fundamental Role of Distorted Factor Markets; Discussion Paper 97-18-REV. Resources for the future: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Miline, J.E. Carbon taxes in the United States: The context for the future. Vt. J. Environ. Law 2008, 10, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Notes to State Motor Fuel Excise and Other Taxes; American Petroleum Institute (API): Washington, DC, USA, 2011. Available online: http://www.atssa.com/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=ObyHMjyVo0A%3D&tabid=211 (accessed on 1 June 2011).

- Parry, I.W.H.; Small, K.A. Does Britain or the United States have the right gasoline tax? Am. Econ. Rev. 2005, 95, 1276–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate Action Plan Tax. Boulder, CO, USA. Available online: http://www.bouldercolorado.gov/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=7698&Itemid=2844 (accessed on 22 December 2011).

- Rules and Regulations, Regulation 3, Schedule T: Greenhouse Gas Fee. Bay Area Air Quality Management District: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2011. Available online: http://www.baaqmd.gov/?sc_itemid=D39A3015-453E-4A0D-9C76-6F7F4DA5AED5 (accessed on 1 March 2011).

- McGowan, E. Maryland County Carbon Tax Law Could Set Example for Rest of Country. InsideClimate News: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2011. Available online: http://insideclimatenews.org/news/20100525/maryland-county-carbon-tax-law-could-set-example-rest-country (accessed on 30 May 2011).

- Welcome. Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative: New York, NY, USA. Available online: http://www.rggi.org/ (accessed on 7 May 2012).

- CO2 Auctions, Tracking & Offsets: Auction Results, “Table: Cumulative Auction Results (Organized by State)”; Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative: New York, NY, USA. Available online: http://www.rggi.org/market/co2_auctions/results (accessed on 7 May 2012).

- RGGI Benefits. Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative: New York, NY, USA. Available online: http://www.rggi.org/rggi_benefits (accessed on 7 May 2012).

- Western Climate Initiative. Available online: http://www.westernclimateinitiative.org/ (accessed on 7 May 2012).

- Segerson, K.; Zhou, R. Green Taxes as a Potential Revenue Source for Connecticut; Connecticut Fund for the Environment: New Haven, CT, USA, 2011.

- Metcalf, G.E. A Green Employment Tax Swap: Using a Carbon Tax to Finance Payroll Tax Relief; World Resources Institute & The Brookings Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bovenberg, A.L.; Goulder, L.H. Neutralizing the Adverse Industry Impacts of CO2 Abatement Policies: What Does It Cost? In Distributional and Behavioral Effects of Environmental Policy; Carraro, C., Metcalf, G.E., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gas Guzzler Tax: Program Overview; Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Transportation and Air quality: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. Available online: http://www.epa.gov/fueleconomy/guzzler/420f11033.htm (accessed on 20 December 2011).

- Vehicles Subject to the Gas Guzzler Tax for Model Year 2009; Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Transportation and Air Quality, Compliance and Innovative Strategies Division: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. Available online: http://www.epa.gov/fueleconomy/guzzler/index.htm (accessed on 5 February 2011).

- Langer, T. Vehicle Efficiency Incentives: An Update on Feebates for States; Report Number T051. American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- American Fact Finder; U.S. Census Bureau: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. Available online: http://factfinder.census.gov/home/saff/main.html?_lang=en (accessed on 5 February 2011).

- Liu, Y.Z. Personnal communication, University of Texas at Austin: Austin, TX, USA, 18 March 2011.

- Jensen, P. Watered-Down State ‘Gas Guzzler’ Law Could Be a Money Loser: Penalty for Poor-Mileage Cars Won’t Raise Any Revenues for Two Years. The Baltimore Sun: Baltimore, MD, 1992. Available online: http://articles.baltimoresun.com/1992-04-22/news/1992113144_1_gas-guzzler-rebate-new-car (accessed on 5 February 2011).

- Sorrell, S.; Dimitropoulos, J.; Sommerville, M. Empirical estimates of the direct rebound effect: A review. Energ. Pol. 2009, 37, 1356–1371. [Google Scholar]

- Annual Report Fiscal Year 2009–2010; Connecticut Department of Revenue Services: Hartford, CT, USA.

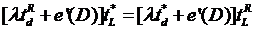

Appendix A. Derivation of Equation (15)

(A.1)

(A.1) (A.2)

(A.2) (A.3)

(A.3) and using the Slutzky decomposition, Equation (A.3) can we written as:

and using the Slutzky decomposition, Equation (A.3) can we written as: (A.4)

(A.4) (A.5)

(A.5) (A.6)

(A.6)© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, R.; Segerson, K. Are Green Taxes a Good Way to Help Solve State Budget Deficits? Sustainability 2012, 4, 1329-1353. https://doi.org/10.3390/su4061329

Zhou R, Segerson K. Are Green Taxes a Good Way to Help Solve State Budget Deficits? Sustainability. 2012; 4(6):1329-1353. https://doi.org/10.3390/su4061329

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Rong, and Kathleen Segerson. 2012. "Are Green Taxes a Good Way to Help Solve State Budget Deficits?" Sustainability 4, no. 6: 1329-1353. https://doi.org/10.3390/su4061329

APA StyleZhou, R., & Segerson, K. (2012). Are Green Taxes a Good Way to Help Solve State Budget Deficits? Sustainability, 4(6), 1329-1353. https://doi.org/10.3390/su4061329