The Effects of Carbon Emission Rights Trading Pilot Policy on Corporate Green Innovation: Evidence from PSM-DID and Policy Insights

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Foundation

2.1. Environmental Policies and Corporate Green Innovation

2.2. Carbon Emission Rights Trading (CERT) and Corporate Outcomes

2.3. Theoretical Foundation

3. Hypotheses Development, Data Processing, and Model Specification

3.1. Hypotheses Development

3.2. Data Processing and Model Specification

3.2.1. Sample Selection and Data Sources

3.2.2. Selection of the Experimental Group

3.2.3. Definition and Construction of Variables

3.2.4. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Test

3.2.5. Bias and Endogeneity Mitigation

3.2.6. Model Specification

4. Empirical Results and Analysis

4.1. Analysis of Empirical Results

4.1.1. Baseline Regression Results

4.1.2. Analysis of Enterprise Heterogeneity in Pilot Regions

4.1.3. Impact on Innovation Quality

4.2. Robustness Test

4.2.1. Persistence and Time-Lag Effects of Policy Impact

4.2.2. Sensitivity to Control Variables

4.2.3. Placebo Test: Counterfactual Policy Timing

4.2.4. Placebo-on-Treatment Test

4.2.5. Staggered Difference-in-Differences Analysis

5. Conclusions

5.1. Carbon Trading Pilots and Corporate Green Innovation: Core Findings

5.2. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Variable | GrP_IU (1) | GrP_I (2) | GrP_U (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| L1.plc_3y | 0.048 * (2.81) ** | 0.072 * (6.33) ** | 0.029 * (1.72) * |

| L1.time_3y | 0.124 *** (2.85) | −0.021 (−0.74) | 0.132 *** (3.12) |

| L1.Carbon_treated | 0.038 (1.52) | 0.055 ** (2.31) | 0.022 (0.89) |

| L1.LnAge | 0.368 *** (5.98) | 0.296 *** (7.20) | 0.230 *** (3.92) |

| L1.LnAst | 0.119 *** (11.48) | 0.046 *** (6.65) | 0.105 *** (10.71) |

| L1.FA_r | 0.169 *** (3.18) | 0.065 * (1.83) | 0.163 *** (3.22) |

| L1.Rev_g | −0.027 *** (−3.35) | −0.021 *** (−3.96) | −0.021 *** (−2.68) |

| L1.Lvg | −0.028 (−0.65) | 0.015 (0.53) | −0.017 (−0.40) |

| L1.C_r | −0.041 (−0.71) | −0.030 (−0.79) | 0.004 (0.07) |

| L1.Q_r | −0.001 (−0.31) | 0.003 (1.30) | −0.002 (−0.59) |

| L1.ROA | 0.075 (0.82) | −0.085 (−1.38) | 0.148 * (1.69) |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | −3.342 *** (−12.90) | −1.646 *** (−9.49) | −2.784 *** (−11.22) |

| N | 12,847 | 12,847 | 12,847 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.112 | 0.074 | 0.080 |

Appendix A.2

| Variable | Sample | Treated Mean | Control Mean | % Bias | % Reduction in Bias | t-Test p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LnAge | Unmatched | 2.658 | 2.619 | 9.2 | 0.031 | |

| Matched | 2.658 | 2.652 | 1.4 | 84.8 | 0.712 | |

| LnAst | Unmatched | 22.215 | 21.798 | 31.8 | 0.000 | |

| Matched | 22.215 | 22.194 | 1.6 | 95.0 | 0.743 | |

| FA_r | Unmatched | 0.252 | 0.234 | 10.2 | 0.012 | |

| Matched | 0.252 | 0.249 | 1.7 | 83.3 | 0.769 | |

| Rev_g | Unmatched | 0.207 | 0.212 | −0.9 | 0.854 | |

| Matched | 0.207 | 0.209 | −0.4 | 55.6 | 0.931 | |

| Lvg | Unmatched | 0.461 | 0.454 | 3.1 | 0.355 | |

| Matched | 0.461 | 0.459 | 0.9 | 71.0 | 0.866 | |

| C_r | Unmatched | 0.173 | 0.178 | −3.4 | 0.422 | |

| Matched | 0.173 | 0.172 | 0.7 | 79.4 | 0.906 | |

| Q_r | Unmatched | 1.892 | 1.896 | −0.2 | 0.978 | |

| Matched | 1.892 | 1.887 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.983 | |

| ROA | Unmatched | 0.042 | 0.041 | 1.6 | 0.665 | |

| Matched | 0.042 | 0.042 | −0.1 | 93.8 | 0.991 |

Appendix A.3

| (a) | |||

| Green Total Patents GrP_IU (1) | Green Invention Patents GrP_I (2) | Green Utility Model Patents GrP_U (3) | |

| L1.plc | 0.172 *** (5.875) | 0.184 *** (9.056) | 0.135 *** (4.728) |

| L1.time | 0.254 *** (3.748) | −0.076 (−1.615) | 0.278 *** (4.218) |

| L1.LnAge | 0.270 *** (2.705) | 0.420 *** (6.076) | 0.085 (0.873) |

| L1.LnAst | 0.205 *** (11.471) | 0.075 *** (6.057) | 0.185 *** (10.622) |

| L1.FA_r | 0.129 (1.466) | 0.026 (0.430) | 0.160 * (1.879) |

| L1.Rev_g | −0.040 ** (−2.562) | −0.031 *** (−2.868) | −0.034 ** (−2.254) |

| L1.Lvg | 0.003 (0.035) | −0.002 (−0.043) | 0.023 (0.296) |

| L1.C_r | −0.113 (−1.099) | −0.022 (−0.305) | −0.072 (−0.717) |

| L1.Q_r | −0.000 (−0.023) | 0.004 (0.726) | −0.001 (−0.144) |

| L1.ROA | 0.211 (1.334) | −0.102 (−0.923) | 0.308 ** (1.998) |

| Year Fixed | Y | Y | Y |

| Industry Fixed | Y | Y | Y |

| Constant | −4.802 *** (−11.078) | −2.497 *** (−8.295) | −4.010 *** (−9.516) |

| N | 7781 | 7781 | 7781 |

| F-Statistic | 81.613 | 48.758 | 57.115 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.172 | 0.110 | 0.127 |

| (b) | |||

| Green Total Patents GrP_IU (1) | Green Invention Patents GrP_I (2) | Green Utility Model Patents GrP_U (3) | |

| L1.plc | 0.039 (1.304) | 0.044 *** (2.624) | 0.019 (0.679) |

| L1.time | 0.115 (1.357) | 0.041 (0.873) | 0.090 (1.166) |

| L1.LnAge | 0.004 (0.033) | −0.052 (−0.717) | 0.032 (0.272) |

| L1.LnAst | 0.014 (0.941) | 0.010 (1.136) | −0.002 (−0.112) |

| L1.FA_r | 0.001 (0.006) | 0.047 (0.905) | −0.060 (−0.716) |

| L1.Rev_g | 0.004 (0.308) | 0.002 (0.346) | 0.003 (0.328) |

| L1.Lvg | −0.073 (−0.954) | −0.000 (−0.003) | −0.021 (−0.296) |

| L1.C_r | −0.231* (−1.944) | −0.090 (−1.352) | −0.156 (−1.440) |

| L1.Q_r | 0.016 (1.438) | 0.011* (1.772) | 0.008 (0.818) |

| L1.ROA | −0.163 (−0.896) | −0.099 (−0.977) | −0.098 (−0.591) |

| Year Fixed | Y | Y | Y |

| Industry Fixed | Y | Y | Y |

| Constant | −0.225 (−0.456) | −0.075 (−0.273) | 0.022 (0.049) |

| N | 1682 | 1682 | 1682 |

| F-Statistic | 3.607 | 2.557 | 2.408 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.040 | 0.029 | 0.027 |

References

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Global Warming of 1.5 °C: IPCC Special Report on Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5 °C Above Pre-Industrial Levels in Context of Strengthening Response to Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coase, R.H. The problem of social cost. In Classic Papers in Natural Resource Economics; Gopalakrishnan, C., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1960; pp. 87–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yu, Z. Factors affecting carbon emission trading price: Evidence from China. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2019, 55, 3433–3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.L.; Patra, P.K.; Chevallier, F.; Maksyutov, S.; Law, R.M.; Ziehn, T.; van der Laan-Luijkx, I.T.; Peters, W.; Ganshin, A.; Zhuravlev, R.; et al. Top–Down Assessment of the Asian Carbon Budget Since the Mid 1990s. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.S.; Boivie, S.; Stern, I.; Porac, J. Inventor CEO involvement and firm exploitative and exploratory innovation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2024, 45, 2227–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Qu, S.; Peng, Z.; Ji, Y.; Boamah, V. The impact of green finance on carbon productivity: The mediating effects of the quantity and quality of green innovation. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrour, M.H.; Arouri, M.; Rao, S. Linking climate risk to credit risk: Evidence from sectorial analysis. J. Altern. Invest. 2024, 27, 118–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Liao, H.; Tan, H. Can carbon trading policy boost upgrading and optimization of industrial structure? An empirical study based on data from China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, B.; Li, N.; Gao, Q.; Li, G. Market incentives, carbon quota allocation and carbon emission reduction: Evidence from China’s carbon trading pilot policy. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 319, 115650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, G.; Feng, C. Innovation-driven policy and firm investment. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 61, 105001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Zhou, S. China’s carbon emission trading pilot policy and China’s export technical sophistication: Based on DID analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 14035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, A.; Hyman, B.; Martin, L.; Nataraj, S. When Do Firms Go Green? Comparing Price Incentives with Command and Control Regulations in India; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, N.; Haščič, I.; Popp, D. Renewable energy policies and technological innovation: Evidence based on patent counts. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2010, 45, 133–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Karplus, V.J.; Cassisa, C.; Zhang, X. Emissions trading in China: Progress and prospects. Energy Policy 2014, 75, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Dai, S.; Zeng, G. Research on the effects of command-and-control and market-oriented policy tools on China’s energy conservation and emissions reduction innovation. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ. 2018, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Wang, M.; Li, M. Low-carbon policy and industrial structure upgrading: Based on the perspective of strategic interaction among local governments. Energy Policy 2023, 183, 113794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Shao, C.; Wang, F.; Dong, R. Evaluation of green and low-carbon development level of Chinese provinces based on sustainable development goals. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Luo, T.; Gao, J. The effect of emission trading policy on carbon emission reduction: Evidence from an integrated study of pilot regions in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 265, 121843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Wang, Q.; Li, H.; Fan, H.; Qian, Y.; Klemeš, J.J. Review of recent progress of emission trading policy in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 349, 131480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munnings, C.; Morgenstern, R.D.; Wang, Z.; Liu, X. Assessing the design of three carbon trading pilot programs in China. Energy Policy 2016, 96, 688–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Li, J.; Gao, F.; Zhang, S. Examining the impact of market segmentation on carbon emission intensity in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.-G.; Chen, H.; Hu, S.; Zhou, Y. The impact of carbon quota allocation and low-carbon technology innovation on carbon market effectiveness: A system dynamics analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 96424–96440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, L.; Sun, Z.; Ma, D. Can carbon emission trading improve corporate sustainability? An analysis of green path and value transformation effect of pilot policy. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2025, 27, 1505–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veith, S.; Werner, J.R.; Zimmermann, J. Capital market response to emission rights returns: Evidence from the European power sector. Energy Econ. 2009, 31, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberndorfer, U. EU emission allowances and the stock market: Evidence from the electricity industry. Ecol. Econ. 2009, 68, 1116–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Foggia, G.; Beccarello, M.; Arrigo, U. Assessment of the European emissions trading system’s impact on sustainable development. Sustainability 2024, 16, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.-J.; Hu, Y.-J.; Tang, B.-J.; Qu, S. Price drivers in the carbon emissions trading scheme: Evidence from Chinese emissions trading scheme pilots. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Xu, Y. Do different types of carbon mitigation regulations have heterogeneous effects on innovation quality? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 43168–43182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.-M.; Fan, Y.; Zhu, L.; Eichhammer, W. Modeling the emission trading scheme from an agent-based perspective: System dynamics emerging from firms’ coordination among abatement options. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 286, 1113–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhou, S.; Wang, S.; Ye, C.; Wu, T. The impact of carbon emissions trading pilot policy on industrial structure upgrading. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Xing, R.; Hanaoka, T.; Kanamori, Y.; Masui, T. Impact of energy efficient technologies on residential CO2 emissions: A comparison of Korea and China. Energy Procedia 2017, 111, 689–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhao, Z. Corporate internal control, financial mismatch mitigation and innovation performance. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0278633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.; Lin, P.; Song, F.M.; Li, C. Managerial incentives, CEO characteristics and corporate innovation in China’s private sector. J. Comp. Econ. 2011, 39, 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornaggia, J.; Mao, Y.; Tian, X.; Wolfe, B. Does banking competition affect innovation? J. Financ. Econ. 2015, 115, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Cheng, W.; Gao, Y. The impact of privatization of state-owned enterprises on innovation in China: A tale of privatization degree. Technovation 2022, 118, 102587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, T.W.; He, W.; He, Z.-L.; Lu, J. Patent regime shift and firm innovation: Evidence from the second amendment to China’s patent law. In Academy of Management Proceedings; Academy of Management: Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 2014; Volume 2014, p. 14174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, M.; Duflo, E.; Mullainathan, S. How much should we trust differences-in-differences estimates? Q. J. Econ. 2004, 119, 249–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.-X.; Cao, C.-S.; Wang, J.-M. Spatial impact of industrial agglomeration and environmental regulation on environmental pollution—Evidence from pollution-intensive industries in China. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 2022, 15, 1525–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Qin, Y.; Xiao, D.; Li, R.; Zhang, H. The impact of industrial land mismatch on carbon emissions in resource-based cities under environmental regulatory constraints—Evidence from China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 56860–56872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Li, Y. Carbon finance and carbon market in China: Progress and challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 214, 536–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. Carbon emission reduction effects of heterogeneous environmental regulation: Evidence from the firm level. Ecol. Chem. Eng. S 2024, 31, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Duan, L.; Cao, Y.; Wen, S. Green Credit Policy and Corporate Climate Risk Exposure. Energy Econ. 2024, 133, 107509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Faure, M.G.; Feng, S. Localization vs globalization of carbon emissions trading system (ETS) rules: How will China’s national ETS rules evolve? Clim. Policy 2025, 25, 996–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.K.; Monteleone, G.; Braccio, G.; Anyanwu, C.N.; Aneke, N.N. A comprehensive review of green energy technologies: Towards sustainable clean energy transition and global net-zero carbon emissions. Processes 2024, 13, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Type | Variable Name | Variable Symbol | Definition and Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Explained Variable | Green Total Patents | GrP_IU | Natural logarithm of the number of granted green patents (invention and utility model patents) of listed companies plus 1 |

| Green Invention Patents | GrP_I | Natural logarithm of the number of granted green invention patents of listed companies plus 1 | |

| Green Utility Model Patents | GrP_U | Natural logarithm of the number of granted green utility model patents of listed companies plus 1 | |

| R&D Expense Ratio | RD_r | R&D Expense/Total Revenue | |

| Explanatory Variable | Direct treatment indicator | Carbon_treated | 1 if the firm is registered in a CERT pilot region (Beijing/Tianjin/Shanghai/Chongqing/Guangdong/Hubei/Shenzhen) and explicitly subject to carbon quota management (verified by local pilot documents or corporate annual reports); 0 otherwise |

| Carbon Emission Pilot Provinces and Cities | Carbon | 1 if the listed company is registered in Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, Chongqing, Guangdong, Hubei, Shenzhen; 0 otherwise | |

| Carbon Emission Pilot Policy Announcement Time | time | 0 for 2007–2011, 1 for 2012–2016 | |

| Interaction Term | plc | Carbon_treated × time | |

| Control Variable | Firm Age | LnAge | Natural logarithm of the number of years since the firm’s establishment |

| Firm Size | LnAst | Natural logarithm of total assets | |

| Net Fixed Assets Ratio | FA_r | Net Fixed Assets/Total Assets | |

| Revenue Growth Rate | Rev_g | Year-on-year growth rate of operating revenue | |

| Asset-Liability Ratio | Lvg | Total Liabilities/Total Assets | |

| Cash Asset Ratio | C_r | Balance of Cash and Cash Equivalents at the End/Total Assets | |

| Quick Ratio | Q_r | (Current Assets − Inventory)/Current Liabilities | |

| Return on Assets | ROA | Net Profit/Average Balance of Total Assets | |

| Year | year | Fixed year | |

| Industry | Industry | Fixed industry |

| Variable Symbol | Observations | Mean | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Median | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GrP_IU | 19,451 | 0.408 | 0.798 | 0 | 0 | 3.611 |

| GrP_I | 19,451 | 0.144 | 0.431 | 0 | 0 | 2.398 |

| GrP_U | 19,451 | 0.339 | 0.720 | 0 | 0 | 3.296 |

| RD_r | 10,117 | 4.288 | 4.188 | 0.03 | 3.43 | 25.31 |

| Carbon | 19,451 | 0.374 | 0.484 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| LnAge | 19,451 | 2.628 | 0.422 | 1.225 | 2.709 | 3.336 |

| LnAst | 19,448 | 21.908 | 1.307 | 19.103 | 21.755 | 25.818 |

| FA_ratio | 19,448 | 0.239 | 0.176 | 0.002 | 0.202 | 0.75 |

| Rev_g | 18,418 | 0.21 | 0.563 | −0.612 | 0.113 | 3.866 |

| Lvg | 19,448 | 0.456 | 0.227 | 0.049 | 0.451 | 1.145 |

| C_r | 19,447 | 0.177 | 0.148 | 0.007 | 0.131 | 0.683 |

| Q_r | 19,449 | 1.895 | 2.634 | 0.127 | 1.027 | 15.944 |

| ROA | 18,469 | 0.041 | 0.062 | −0.212 | 0.037 | 0.232 |

| Control Group | Experimental Group | Difference | DID | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before Adjustment (1) | After Adjustment (2) | Before Adjustment (3) | After Adjustment (4) | (5) = (2) − (1) | (6) = (4) − (3) | (7) = (6) − (5) | |

| Green Total Patents | 0.165 | 0.475 | 0.303 | 0.680 | 0.310 *** (21.83) | 0.377 *** (20.46) | 0.067 *** (2.88) |

| Green Invention Patents | 0.039 | 0.155 | 0.085 | 0.301 | 0.116 *** (15.14) | 0.216 *** (21.66) | 0.100 *** (7.91) |

| Green Utility Model Patents | 0.139 | 0.394 | 0.266 | 0.554 | 0.255 *** (19.77) | 0.288 *** (17.21) | 0.033 (1.56) |

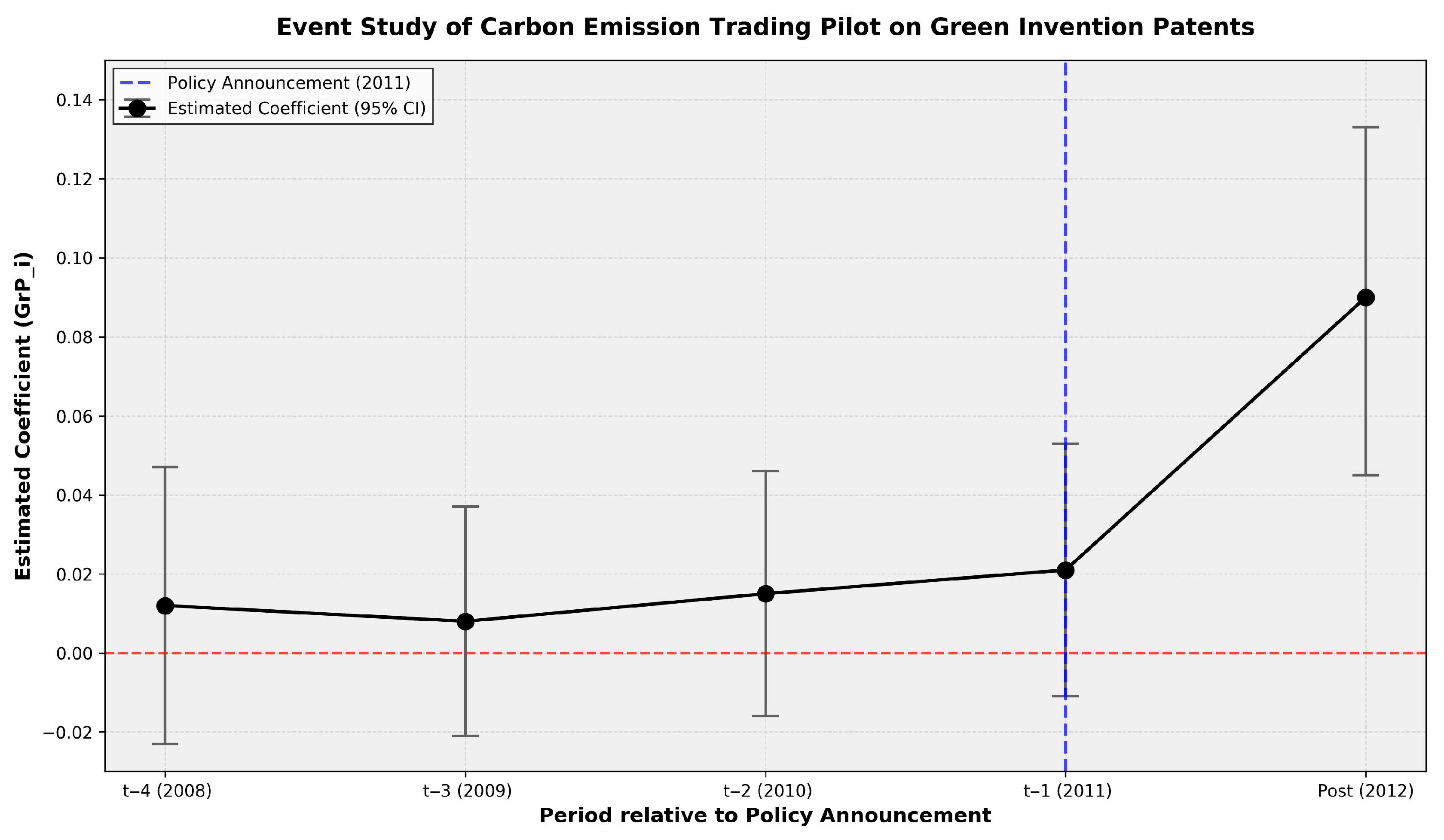

| Period (Relative to 2011 Policy) | Coefficient (GrP_I) | Std. Error | p-Value | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| t − 4 (2008) | 0.012 | 0.018 | 0.503 | (−0.023, 0.047) |

| t − 3 (2009) | 0.008 | 0.015 | 0.587 | (−0.021, 0.037) |

| t − 2 (2010) | 0.015 | 0.016 | 0.341 | (−0.016, 0.046) |

| t − 1 (2011) | 0.021 | 0.017 | 0.225 | (−0.012, 0.054) |

| Post-policy (t + 1, 2012) | 0.089 *** | 0.023 | 0.000 | (0.044, 0.134) |

| Controls | Yes | - | - | - |

| Year Fixed Effects | Yes | - | - | - |

| Industry Fixed Effects | Yes | - | - | - |

| N | 16,184 | - | - | - |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.076 | - | - | - |

| Green Total Patents GrP_IU (1) | Green Invention Patents GrP_I (2) | Green Utility Model Patents GrP_U (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| L1.plc | 0.058 *** (3.465) | 0.089 *** (7.893) | 0.036 ** (2.251) |

| L1.time | 0.117 *** (2.822) | −0.024 (−0.859) | 0.119 *** (3.006) |

| L1.LnAge | 0.372 *** (6.067) | 0.299 *** (7.291) | 0.232 *** (3.960) |

| L1.LnAst | 0.126 *** (12.239) | 0.047 *** (6.856) | 0.112 *** (11.448) |

| L1.FA_r | 0.172 *** (3.243) | 0.068 * (1.920) | 0.167 *** (3.301) |

| L1.Rev_g | −0.026 *** (−3.329) | −0.020 *** (−3.798) | −0.020 *** (−2.670) |

| L1.Lvg | −0.030 (−0.695) | 0.014 (0.496) | −0.018 (−0.437) |

| L1.C_r | −0.043 (−0.744) | −0.031 (−0.813) | 0.005 (0.100) |

| L1.Q_r | −0.001 (−0.308) | 0.003 (1.295) | −0.002 (−0.595) |

| L1.ROA | 0.078 (0.853) | −0.083 (−1.346) | 0.153 * (1.748) |

| Year Fixed | Y | Y | Y |

| Industry Fixed | Y | Y | Y |

| Constant | −3.365 *** (−12.985) | −1.660 *** (−9.574) | −2.806 *** (−11.324) |

| N | 16,184 | 16,184 | 16,184 |

| F-Statistic | 108.687 | 67.172 | 73.507 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.117 | 0.076 | 0.082 |

| Green Total Patents GrP_IU (1) | Green Invention Patents GrP_I (2) | Green Utility Model Patents GrP_U (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| L1.plc | 0.044 (0.957) | 0.077 ** (2.365) | 0.008 (0.197) |

| L1.time | 0.090 (0.893) | −0.106 (−1.469) | 0.174 * (1.827) |

| L1.LnAge | 0.549 *** (3.745) | 0.515 *** (4.916) | 0.276 ** (2.002) |

| L1.LnAst | 0.139 *** (5.361) | 0.076 *** (4.075) | 0.107 *** (4.373) |

| L1.FA_r | 0.177 (1.327) | 0.079 (0.836) | 0.174 (1.395) |

| L1.Rev_g | −0.038 ** (−2.000) | −0.019 (−1.426) | −0.025 (−1.439) |

| L1.Lvg | −0.156 (−1.397) | −0.102 (−1.273) | −0.096 (−0.910) |

| L1.C_r | −0.175 (−1.248) | −0.035 (−0.346) | −0.124 (−0.942) |

| L1.Q_r | 0.016 (1.559) | 0.008 (1.119) | 0.016 * (1.676) |

| L1.ROA | −0.179 (−0.800) | −0.244 (−1.534) | −0.061 (−0.290) |

| Year Fixed | Y | Y | Y |

| Industry Fixed | Y | Y | Y |

| Constant | −3.975 *** (−6.265) | −2.717 *** (−5.996) | −2.726 *** (−4.577) |

| N | 4420 | 4420 | 4420 |

| F-Statistic | 25.471 | 17.217 | 16.834 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.134 | 0.095 | 0.093 |

| Green Total Patents | Green Invention Patents | Green Utility Model Patents | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quota-Managed Firms in Eastern Pilot Regions (1) | Quota-Managed Firms in Central-Western Pilot Regions (2) | Quota-Managed Firms in Eastern Pilot Regions (3) | Quota-Managed Firms in Central-Western Pilot Regions (4) | Quota-Managed Firms in Eastern Pilot Regions (5) | Quota-Managed Firms in Central-Western Pilot Regions (6) | |

| L1.plc | 0.036 (0.607) | 0.005 (0.065) | 0.048 (1.153) | 0.113 ** (1.988) | 0.022 (0.401) | −0.069 (−0.949) |

| L1.time | 0.048 (0.405) | 0.520 ** (2.235) | −0.089 (−1.049) | −0.050 (−0.292) | 0.121 (1.083) | 0.549 ** (2.532) |

| L1.LnAge | 0.628 *** (3.863) | −0.163 (−0.419) | 0.521 *** (4.520) | 0.397 (1.390) | 0.333 ** (2.175) | −0.270 (−0.742) |

| L1.LnAst | 0.121 *** (3.666) | 0.197 *** (4.510) | 0.072 *** (3.089) | 0.092 *** (2.890) | 0.091 *** (2.927) | 0.153 *** (3.771) |

| L1.FA_r | 0.308 * (1.804) | 0.011 (0.052) | 0.185 (1.530) | −0.037 (−0.240) | 0.294 * (1.826) | −0.008 (−0.039) |

| L1.Rev_g | −0.013 (−0.529) | −0.081 *** (−2.647) | −0.007 (−0.435) | −0.035 (−1.571) | −0.005 (−0.210) | −0.066 ** (−2.288) |

| L1.Lvg | −0.273 * (−1.938) | 0.063 (0.330) | −0.195 * (−1.952) | 0.070 (0.504) | −0.161 (−1.214) | 0.010 (0.058) |

| L1.C_r | −0.282 * (−1.710) | 0.007 (0.026) | −0.096 (−0.816) | 0.076 (0.379) | −0.212 (−1.363) | 0.044 (0.172) |

| L1.Q_r | 0.020 * (1.656) | 0.006 (0.318) | 0.005 (0.613) | 0.018 (1.309) | 0.022 ** (2.005) | −0.003 (−0.166) |

| L1.ROA | −0.505 * (−1.861) | 0.576 (1.370) | −0.467 ** (−2.426) | 0.199 (0.646) | −0.271 (−1.061) | 0.411 (1.047) |

| Year Fixed | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Industry Fixed | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Constant | −3.641 *** (−4.757) | −3.793 *** (−2.967) | −2.578 *** (−4.749) | −2.994 *** (−3.197) | −2.451 *** (−3.401) | −2.585 ** (−2.168) |

| N | 3260 | 1160 | 3260 | 1160 | 3260 | 1160 |

| F-Statistic | 18.489 | 8.649 | 13.431 | 5.082 | 11.905 | 6.257 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.129 | 0.180 | 0.097 | 0.114 | 0.087 | 0.137 |

| Green Total Patents | Green Invention Patents | Green Utility Model Patents | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-Tech Quota-Managed Firms (1) | Non-High-Tech Quota-Managed Firms (2) | High-Tech Quota-Managed Firms (3) | Non-High-Tech Quota-Managed Firms (4) | High-Tech Quota-Managed Firms (5) | Non-High-Tech Quota-Managed Firms (6) | |

| L1.plc | 0.052 (0.675) | 0.057 (1.026) | 0.070 (1.198) | 0.093 ** (2.455) | 0.015 (0.201) | 0.023 (0.459) |

| L1.time | 0.409 ** (2.279) | −0.038 (−0.318) | 0.141 (1.052) | −0.223 *** (−2.712) | 0.416 ** (2.431) | 0.093 (0.844) |

| L1.LnAge | 0.273 (1.106) | 0.634 *** (3.523) | 0.402 ** (2.178) | 0.539 *** (4.388) | 0.009 (0.040) | 0.349 ** (2.107) |

| L1.LnAst | 0.171 *** (3.484) | 0.110 *** (3.687) | 0.077 ** (2.109) | 0.066 *** (3.224) | 0.153 *** (3.279) | 0.072 *** (2.597) |

| L1.FA_r | 0.041 (0.161) | 0.233 (1.549) | −0.014 (−0.075) | 0.129 (1.254) | 0.071 (0.290) | 0.208 (1.503) |

| L1.Rev_g | −0.040 (−1.110) | −0.034 (−1.615) | −0.020 (−0.725) | −0.016 (−1.133) | −0.019 (−0.533) | −0.027 (−1.379) |

| L1.Lvg | −0.214 (−1.037) | −0.111 (−0.857) | −0.183 (−1.184) | −0.040 (−0.454) | −0.175 (−0.890) | −0.049 (−0.409) |

| L1.C_r | −0.156 (−0.680) | −0.204 (−1.159) | −0.009 (−0.053) | −0.043 (−0.354) | −0.092 (−0.420) | −0.178 (−1.098) |

| L1.Q_r | 0.008 (0.569) | 0.024 * (1.649) | −0.001 (−0.073) | 0.021 ** (2.098) | 0.013 (0.947) | 0.016 (1.226) |

| L1.ROA | −0.280 (−0.651) | −0.084 (−0.333) | −0.248 (−0.770) | −0.228 (−1.319) | −0.429 (−1.047) | 0.166 (0.715) |

| Year Fixed | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Industry Fixed | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Constant | −3.816 *** (−3.340) | −3.728 *** (−4.930) | −2.406 *** (−2.817) | −2.667 *** (−5.165) | −2.942 *** (−2.702) | −2.271 *** (−3.267) |

| N | 1842 | 2578 | 1842 | 2578 | 1842 | 2578 |

| F-Statistic | 14.932 | 11.663 | 8.833 | 9.335 | 11.622 | 7.043 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.182 | 0.108 | 0.116 | 0.088 | 0.147 | 0.068 |

| Green Total Patents | Green Invention Patents | Green Utility Model Patents | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mature Quota-Managed Firms (1) | Growing Quota-Managed Firms (2) | Mature Quota-Managed Firms (3) | Growing Quota-Managed Firms (4) | Mature Quota-Managed Firms (5) | Growing Quota-Managed Firms (6) | |

| L1.plc | 0.017 (0.349) | 0.182 (1.310) | 0.071 ** (2.107) | 0.090 (0.868) | −0.017 (−0.369) | 0.133 (0.997) |

| L1.time | 0.174 (1.161) | 0.168 (0.347) | 0.054 (0.514) | 0.175 (0.481) | 0.171 (1.225) | 0.211 (0.453) |

| L1.LnAge | 0.447 * (1.686) | 0.327 (0.760) | 0.192 (1.028) | 0.372 (1.151) | 0.344 (1.393) | 0.047 (0.114) |

| L1.LnAst | 0.129 *** (4.921) | 0.234 ** (2.082) | 0.072 *** (3.884) | 0.102 (1.214) | 0.098 *** (3.989) | 0.189 * (1.748) |

| L1.FA_r | 0.182 (1.327) | −0.014 (−0.029) | 0.093 (0.964) | −0.025 (−0.069) | 0.164 (1.282) | 0.068 (0.146) |

| L1.Rev_g | −0.031 (−1.604) | −0.109 (−1.430) | −0.019 (−1.448) | −0.011 (−0.195) | −0.019 (−1.069) | −0.087 (−1.193) |

| L1.Lvg | −0.171 (−1.480) | 0.072 (0.168) | −0.101 (−1.240) | 0.027 (0.083) | −0.110 (−1.024) | 0.011 (0.028) |

| L1.C_r | −0.191 (−1.253) | −0.262 (−0.724) | −0.061 (−0.568) | 0.033 (0.122) | −0.172 (−1.210) | −0.054 (−0.155) |

| L1.Q_r | 0.015 (1.198) | 0.017 (0.911) | 0.012 (1.272) | 0.004 (0.298) | 0.013 (1.109) | 0.015 (0.871) |

| L1.ROA | −0.041 (−0.179) | −1.444 * (−1.764) | −0.212 (−1.318) | −0.496 (−0.807) | 0.059 (0.279) | −1.142 (−1.449) |

| Year Fixed | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Industry Fixed | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Constant | −3.631 *** (−4.310) | −5.166 ** (−2.211) | −1.933 *** (−3.253) | −2.873 (−1.637) | −2.767 *** (−3.526) | −3.787 * (−1.684) |

| N | 3548 | 872 | 3548 | 872 | 3548 | 872 |

| F-Statistic | 19.883 | 6.612 | 11.571 | 5.438 | 14.513 | 3.866 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.128 | 0.188 | 0.079 | 0.160 | 0.097 | 0.119 |

| Variable | (1) Full Sample (MI-Imputed RD_r) | (2) Restricted Sample (Complete R&D Data Only) |

|---|---|---|

| L1.plc | 0.021 (p = 0.183) | 0.035 (p = 0.101) |

| L1.time | 0.089 (p = 0.215) | 0.102 (p = 0.187) |

| L1.LnAge | 0.215 *** (p = 0.001) | 0.239 *** (p = 0.000) |

| L1.LnAst | 0.047 *** (p = 0.000) | 0.051 *** (p = 0.000) |

| Controls | Yes | Yes |

| Year Fixed | Yes | Yes |

| Industry Fixed | Yes | Yes |

| N | 19,451 | 10,117 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.068 | 0.082 |

| Lag 2 Period | Lag 3 Period | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GrP_IU (1) | GrP_I (2) | GrP_U (3) | GrP_IU (4) | GrP_I (5) | GrP_U (6) | |

| L2.plc | 0.048 *** (2.623) | 0.065 *** (5.043) | 0.033 * (1.863) | - | - | - |

| L3.plc | - | - | - | 0.038 * (1.832) | 0.031 ** (2.128) | 0.032 (1.588) |

| L2.time | 0.147 *** (3.318) | 0.001 (0.026) | 0.127 *** (2.956) | - | - | - |

| L3.time | - | - | - | 0.189 *** (4.034) | 0.069 ** (2.058) | 0.129 *** (2.826) |

| L2.LnAge | 0.364 *** (4.898) | 0.295 *** (5.625) | 0.253 *** (3.519) | - | - | - |

| L3.LnAge | - | - | - | 0.258 *** (2.839) | 0.200 *** (3.080) | 0.209 ** (2.368) |

| L2.LnAst | 0.102 *** (8.448) | 0.059 *** (6.891) | 0.088 *** (7.525) | - | - | - |

| L3.LnAst | - | - | - | 0.062 *** (4.496) | 0.055 *** (5.560) | 0.048 *** (3.578) |

| L2.FA_r | 0.141 ** (2.351) | 0.102 ** (2.422) | 0.128 ** (2.215) | - | - | - |

| L3.FA_r | - | - | - | 0.120 * (1.798) | 0.148 *** (3.088) | 0.069 (1.055) |

| L2.Rev_g | −0.005 (−0.517) | −0.009 (−1.421) | −0.005 (−0.565) | - | - | - |

| L3.Rev_g | - | - | - | −0.016 * (−1.745) | −0.013 * (−1.909) | −0.013 (−1.448) |

| L2.Lvg | −0.006 (−0.119) | 0.012 (0.354) | −0.006 (−0.114) | - | - | - |

| L3.Lvg | - | - | - | −0.003 (−0.054) | 0.025 (0.607) | −0.022 (−0.400) |

| L2.C_r | 0.071 (1.071) | 0.035 (0.744) | 0.079 (1.234) | - | - | - |

| L3.C_r | - | - | - | 0.076 (1.017) | 0.123 ** (2.289) | 0.028 (0.380) |

| L2.Q_r | −0.010 ** (−2.216) | 0.001 (0.315) | −0.010 ** (−2.369) | - | - | - |

| L3.Q_r | - | - | - | −0.013 ** (−2.549) | −0.004 (−1.055) | −0.011 ** (−2.197) |

| L2.ROA | 0.135 (1.393) | −0.036 (−0.523) | 0.203 ** (2.165) | - | - | - |

| L3.ROA | - | - | - | 0.165 (1.592) | 0.072 (0.968) | 0.138 (1.363) |

| Year Fixed | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Industry Fixed | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Constant | −2.811 *** (−9.165) | −1.894 *** (−8.775) | −2.292 *** (−7.721) | −1.640 *** (−4.593) | −1.621 *** (−6.333) | −1.237 *** (−3.564) |

| N | 13,953 | 13,953 | 13,953 | 11,722 | 11,722 | 11,722 |

| F-Statistic | 75.527 | 47.803 | 50.130 | 46.781 | 30.342 | 29.997 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.094 | 0.061 | 0.064 | 0.069 | 0.046 | 0.045 |

| Green Total Patents GrP_IU (1) | Green Invention Patents GrP_I (2) | Green Utility Model Patents GrP_U (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| L1.plc | 0.052 *** (3.112) | 0.086 *** (7.682) | 0.031 * (1.927) |

| L1.time | 0.173 *** (4.239) | 0.001 (0.022) | 0.167 *** (4.288) |

| L1.LnAge | 0.359 *** (5.841) | 0.295 *** (7.173) | 0.220 *** (3.755) |

| L1.LnRev | 0.098 *** (10.913) | 0.033 *** (5.450) | 0.090 *** (10.449) |

| L1.FA_r | 0.109 ** (2.058) | 0.044 (1.249) | 0.111 ** (2.207) |

| L1.Rev_g | −0.036 *** (−4.381) | −0.022 *** (−4.132) | −0.029 *** (−3.739) |

| L1.Lvg | −0.019 (−0.441) | 0.018 (0.627) | −0.007 (−0.165) |

| L1.C_r | −0.042 (−0.752) | −0.026 (−0.684) | 0.002 (0.043) |

| L1.Current_r | −0.002 (−0.531) | 0.002 (0.845) | −0.002 (−0.611) |

| L1.ROA | −0.018 (−0.196) | −0.113 * (−1.816) | 0.732 (0.732) |

| Year Fixed | Y | Y | Y |

| Industry Fixed | Y | Y | Y |

| Constant | −2.676 *** (−11.561) | −1.321 *** (−8.532) | −2.234*** (−10.094) |

| N | 16,178 | 16,178 | 16,178 |

| F-Statistic | 106.802 | 66.007 | 72.229 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.115 | 0.075 | 0.081 |

| Variables | Green Total Patents (GrP_IU) | Green Invention Patents (GrP_I) | Green Utility Model Patents (GrP_U) |

|---|---|---|---|

| L1.Treat × Post_Staggered | 0.042 (1.25) | 0.082 ** (2.41) | 0.025 (0.88) |

| L1.Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 16,184 | 16,184 | 16,184 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.118 | 0.078 | 0.081 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jiang, H.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Z. The Effects of Carbon Emission Rights Trading Pilot Policy on Corporate Green Innovation: Evidence from PSM-DID and Policy Insights. Sustainability 2026, 18, 1207. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031207

Jiang H, Liu Z, Chen Z. The Effects of Carbon Emission Rights Trading Pilot Policy on Corporate Green Innovation: Evidence from PSM-DID and Policy Insights. Sustainability. 2026; 18(3):1207. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031207

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Huilu, Zhixi Liu, and Zhenlin Chen. 2026. "The Effects of Carbon Emission Rights Trading Pilot Policy on Corporate Green Innovation: Evidence from PSM-DID and Policy Insights" Sustainability 18, no. 3: 1207. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031207

APA StyleJiang, H., Liu, Z., & Chen, Z. (2026). The Effects of Carbon Emission Rights Trading Pilot Policy on Corporate Green Innovation: Evidence from PSM-DID and Policy Insights. Sustainability, 18(3), 1207. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031207