The Impact of Technology Transfer on Green Total Factor Energy Efficiency: Evidence from the Establishment of National Technology Transfer Centers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Influencing Factors of GTFEE

2.2. The Effect of Technology Transfer

2.3. Impact of Technology Transfer on GTFEE

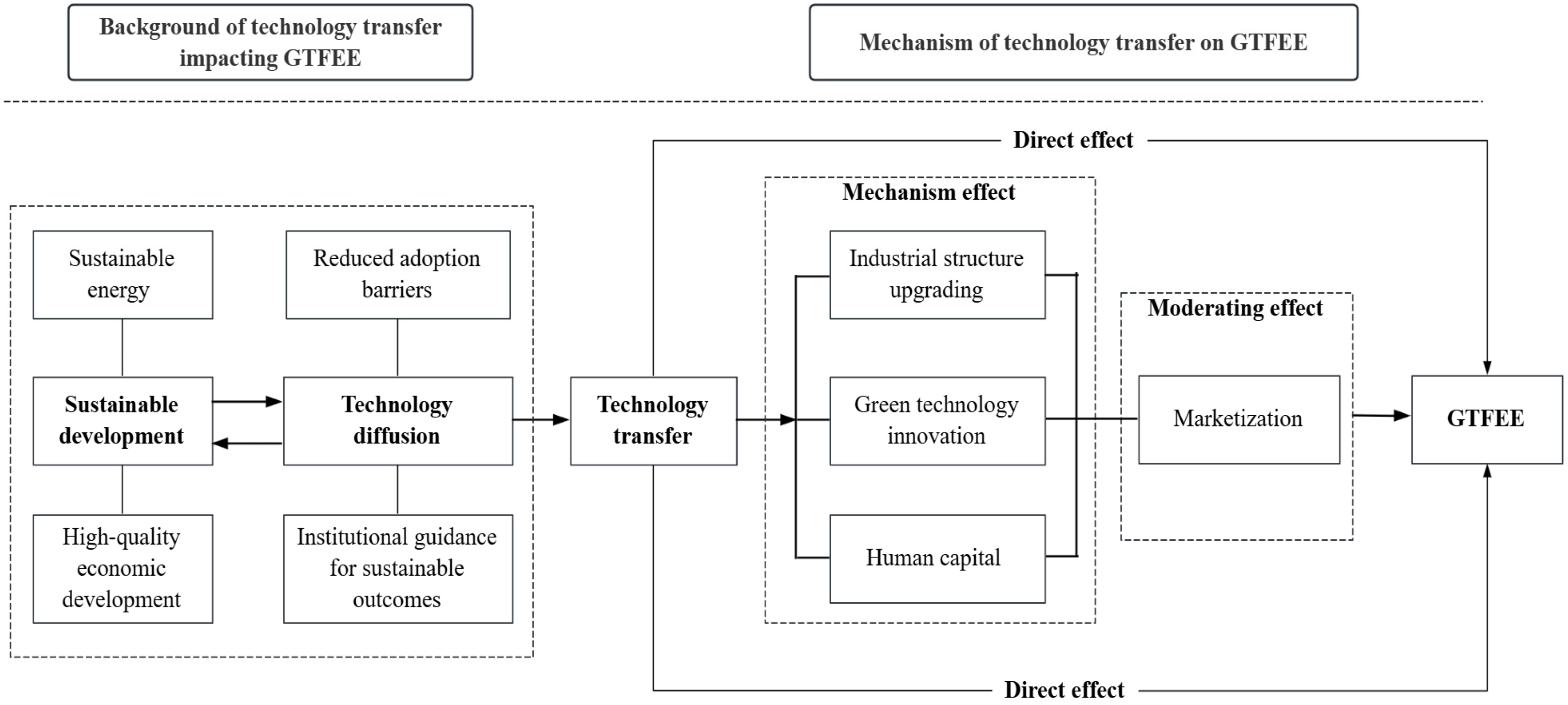

3. Policy Background and Research Hypotheses

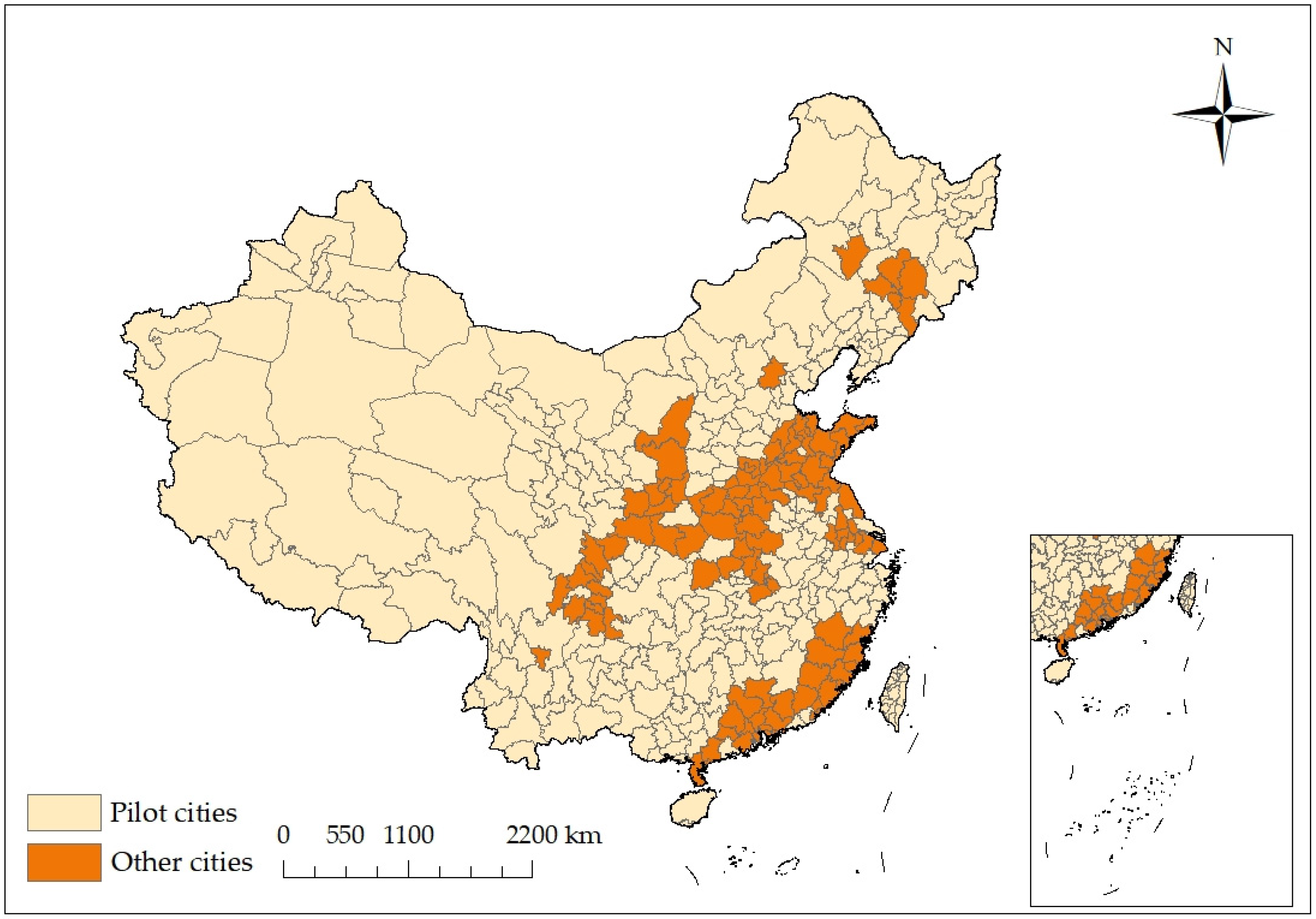

3.1. Background of the NTTCs

3.2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

3.2.1. Technology Transfer and GTFEE

3.2.2. Analysis of Moderating Effects

4. Research Design

4.1. Data Sources and Processing

4.2. Model Construction

4.3. Variable Definitions

4.3.1. GTFEE

4.3.2. Technology Transfer

4.3.3. Control Variables

4.3.4. Mechanism Variables

5. Empirical Analysis

5.1. Benchmark Regression: The Impact of Technology Transfer on GTFEE

5.2. Validity Test of the DID Model

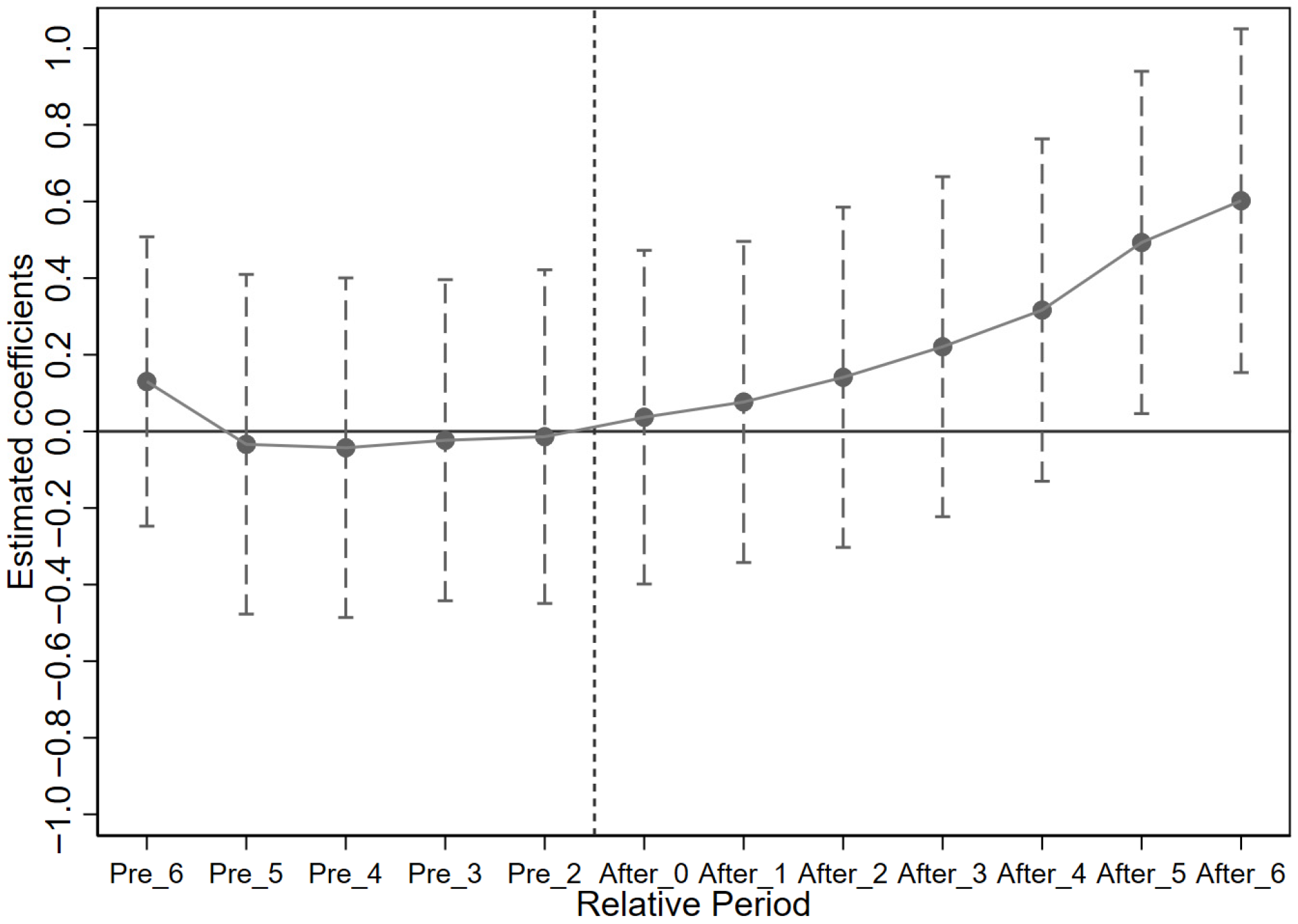

5.2.1. Parallel Trend Test

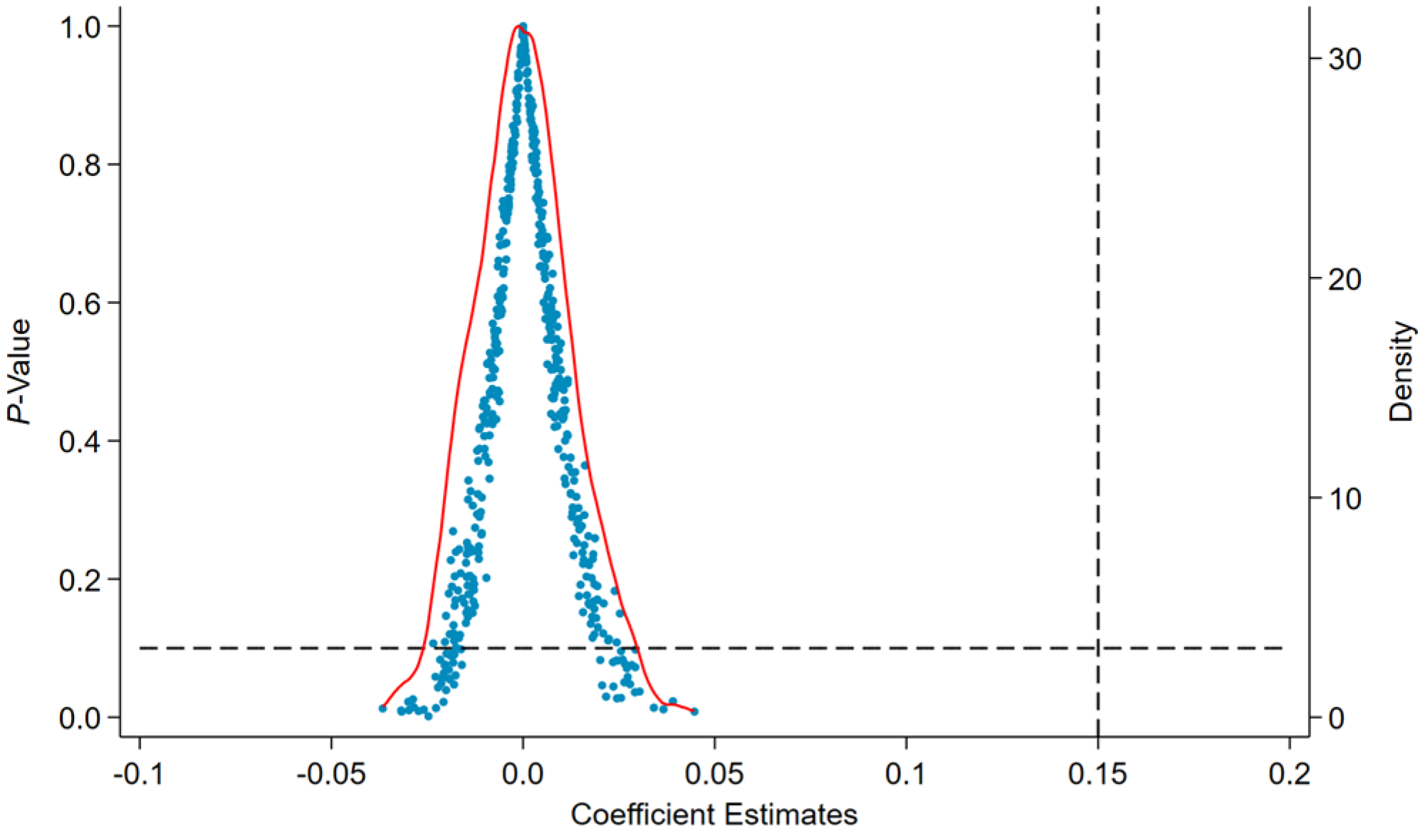

5.2.2. Placebo Test

5.2.3. Heterogeneous Treatment Effect Tests

5.3. Robustness Tests

5.3.1. PSM-DID and Entropy Balancing Method

5.3.2. Mean-Year Joint Fixed Effects

5.3.3. Data Trimming Procedure

5.3.4. Alternative Core Variable Specification

5.3.5. Policy Exogeneity Test

5.3.6. Excluding Other Policy Interferences

5.4. Mechanism Analysis

5.5. Moderating Effects Analysis

6. Further Analysis: Heterogeneity Analysis

6.1. Heterogeneity: Digital Economics

6.2. Heterogeneity: Intellectual Property Protection

6.3. Heterogeneity: Resource Endowment

6.4. Heterogeneity: Urban Network Centrality

7. Conclusions and Policy Implications

7.1. Conclusions

7.2. Theoretical Contributions

7.3. Policy Value

8. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shao, J.; Wang, L. Can new-type urbanization improve the green total factor energy efficiency? Evidence from China. Energy 2023, 262, 125499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Gao, D.; Li, Y. Impacts of market-based environmental regulation on green total factor energy efficiency in China. China World Econ. 2023, 31, 92–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Liao, N.; Lin, K. Can China’s industrial sector achieve energy conservation and emission reduction goals dominated by energy efficiency enhancement? A multi-objective optimization approach. Energy Policy 2021, 149, 112108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcagnini, G.; Favaretto, I. Models of university technology transfer: Analyses and policies. J. Technol. Transf. 2016, 41, 655–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M.; Takegami, S.; Yin, J. Lessons learned about technology transfer. Technovation 2001, 21, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Zhang, Y.J.; Qiang, W. Does technological innovation benefit energy firms’ environmental performance? The moderating effect of government subsidies and media coverage. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 180, 121728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Wu, H.; Jiang, M.; Yang, J. From transfer to transformation: How national technology transfer centers drive digital innovation. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2024, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Huang, Y.; Wang, L. Impact of national technology transfer markets on entrepreneurship in China. China World Econ. 2025, 33, 76–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Zhang, C.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Ning, L. Technology transfer systems and modes of national research institutes: Evidence from the Chinese academy of sciences. Res. Policy 2022, 51, 104471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Wang, W.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, J. How does digital economy affect green total factor productivity? Evidence from China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 857, 159428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ma, D. Financial agglomeration, technological innovation, and green total factor energy efficiency. Alex. Eng. J. 2021, 60, 4085–4095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Kong, Q.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L. Examining the effect of low-carbon City trial on green total factor energy efficiency in China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, G.; Chen, G.; Yang, K.; Yin, W.; Tian, L. How does green fiscal expenditure promote green total factor energy efficiency? Evidence from Chinese 254 cities. Appl. Energy 2024, 353, 122098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Weng, S.; Zhu, M. “Booster” or “Obstacle”: How does industrial digitalization impact marine green total factor energy efficiency. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 519, 145998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Liang, W.; Lee, C.C. Urban broadband infrastructure and green total-factor energy efficiency in China. Util. Policy 2022, 79, 101414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.Y.; Wang, K.L.; Miao, Z. The impact of digital technology innovation on green total-factor energy efficiency in China: Does economic development matter? Energy Policy 2024, 194, 114342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sun, Z. Does the synergy between fintech and green finance lead to the enhancement of urban green total factor energy efficiency? Empirical evidence from China. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 382, 125366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Ding, D.; Sun, C. Does innovative city policy improve green total factor energy efficiency? Evidence from China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Gai, Z.; Wu, H. How do resource misallocation and government corruption affect green total factor energy efficiency? Evidence from China. Energy Policy 2020, 143, 111562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Wang, C. Does industrial relocation affect green total factor energy efficiency? Evidence from China’s high energy-consuming industries. Energy 2024, 289, 130002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.N. Comparing North-South technology transfer and South-South technology transfer: The technology transfer impact of Ethiopian Wind Farms. Energy Policy 2018, 116, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, F.; Hong, J.; Ho, B.; Fang, T. Technology Transfer Channels and Innovation Efficiency: Empirical Evidence From Chinese Manufacturing Industries. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2020, 69, 2426–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasar, M.; Paul, C.J.M. Foreign technology transfer and productivity: Evidence from a matched sample. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 2008, 26, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M.; Rolfo, S. Technology transfer analysis in the Italian National Research Council. Technovation 2002, 22, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, V.; Schultz, K.; Funkhouser, E. International low carbon technology transfer: Do intellectual property regimes matter? Glob. Environ. Change 2014, 24, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, T.; von Staden, P.; Kwon, K.S. Sustainable Economic Growth and the Adaptability of a National System of Innovation. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lin, B. Understanding the green total factor energy efficiency gap between regional manufacturing—Insight from infrastructure development. Energy 2021, 237, 121553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Qi, S. Has the pilot carbon trading policy improved China’s green total factor energy efficiency? Energy Econ. 2022, 114, 106268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Wang, L. Impact of Digital Economy on Agricultural Green Total Factor Productivity: Evidence from the Quasi-Natural Experiment of the “Broadband China” Strategy. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1607567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltoniemi, M. Reviewing industry life-cycle theory: Avenues for future research. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2011, 13, 349–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, G.; Wang, Z.; Jiao, X.; Wang, C. The spatio-temporal characteristics of intercity green technology innovation transfer and its air pollution reduction effect in China. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 178, 113934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temel, S.; Dabić, M.; Ar, I.M.; Howells, J.; Mert, A.; Yesilay, R.B. Exploring the relationship between university innovation intermediaries and patenting performance. Technol. Soc. 2021, 66, 101665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisetti, C.; Mancinelli, S.; Mazzanti, M.; Zoli, M. Financial barriers and environmental innovations: Evidence from EU manufacturing firms. Clim. Policy 2017, 17, S131–S147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libecap, G.D. Addressing global environmental externalities: Transaction costs considerations. J. Econ. Lit. 2014, 52, 424–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E.; Hameri, A.P.; Vuola, O. A framework of industrial knowledge spillovers in big-science centers. Res. Policy 2004, 33, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Sun, Z.; Shi, R.; Zhao, M. Smart city and green development: Empirical evidence from the perspective of green technological innovation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 191, 122507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangudhla, T.; Yong, L.; Tong, J.J.J.; Ahakwa, I.; Appiah-Twum, F. Achieving net zero in Africa: Can crowdfunding propel green technological innovation and renewable energy adoption? J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 380, 125037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.C.; Zhao, Y.N. Heterogeneity analysis of factors influencing CO2 emissions: The role of human capital, urbanization, and FDI. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 185, 113644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Sui, F.; Huang, X. Green technology transfer for firms in a multi-layer network perspective: The dual impact of knowledge resources and regional environment. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2025, 39, 104291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, A.A.C.; Queirós, A.S.S. Economic growth, human capital and structural change: A dynamic panel data analysis. Res. Policy 2016, 45, 1636–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Wang, Q.; Long, X.; Yan, Z.; Salman, M.; Wu, C. Green innovation and SO2 emissions: Dynamic threshold effect of human capital. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 499–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, P.; Pan, Z.; Zeng, X.; Zhu, Y. Who takes the lead: Synergistic emission reduction effects of proactive government and efficient market in atmospheric pollution mitigation. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 371, 123001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; He, X.; Xu, L. Market or government: Who plays a decisive role in R&D resource allocation? China Financ. Rev. Int. 2019, 9, 110–136. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Sun, M. How does financial accessibility affect the resource allocation of enterprises? Micro-evidence from the financial geographical structure of investment-oriented enterprises. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 84, 107820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Li, C.; Xiong, X. Innovation and environmental total factor productivity in China: The moderating roles of economic policy uncertainty and marketization process. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 9558–9581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, C.; Xia, Y.; Liu, Q.; Hou, B. Deregulation and green innovation: Does cultural reform pilot project matter. Econ. Anal. Policy 2023, 78, 84–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Zhang, W.; Liu, X.; Muhammad, A.; Li, Z.; Işık, C. Climate policy uncertainty and green total factor energy efficiency: Does the green finance matter? Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2025, 104, 104293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.L.; Kao, C.H. Efficient energy-saving targets for APEC economies. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.L.; Hu, L.P.; Fan, G. China Provincial Marketization Index Report (2021); Social Sciences Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, W.; Li, L.; Huang, Y. Industrial collaborative agglomeration, marketization, and green innovation: Evidence from China’s provincial panel data. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Huang, C. Analysis of Emission Reduction Effects of Carbon Trading: Market Mechanism or Government Intervention? Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 33, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.M.; Jiang, F. From financing to innovation: How green bond issuance promotes corporate green innovation in China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 86, 108462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Zeng, B. Urban Technology Transfer, Spatial Spillover Effects, and Carbon Emissions in China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.Y. Can low-carbon technology transfer accelerate energy efficiency convergence. Energy 2025, 333, 137365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaway, B.; Sant’Anna, P.H.C. Difference-in-Differences with multiple time periods. J. Econom. 2021, 225, 200–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.; Levine, R.; Levkov, A. Big Bad Banks? The Winners and Losers from Bank Deregulation in the United States. J. Financ. 2010, 65, 1637–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Xue, Y.; Wu, H.; Irfan, M.; Hao, Y. How does telecommunications infrastructure affect eco-efficiency? Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in China. Technol. Soc. 2022, 69, 101963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yang, X.; Meng, Y.; Ran, Q.; Liu, Z. Does the construction of national eco-industrial demonstration parks improve green total factor productivity? Evidence from prefecture-level cities in China. Sustainability 2021, 14, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Qi, X.; Xu, M.; Su, J.; Wang, Z. Digital finance, industrial structure upgrading, and energy efficiency in China: A provincial-level empirical analysis. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Fan, Z.; Yao, D. The impact of industrial robot on green total factor energy efficiency under the “resource curse” perspective: Evidence from cities in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 385, 125641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prokop, V.; Gerstlberger, W.; Zapletal, D.; Gyamfi, S. Do we need human capital heterogeneity for energy efficiency and innovativeness? Insights from European catching-up territories. Energy Policy 2023, 177, 113565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhong, M.; Dong, Y. Digital economy and risk response: How the digital economy affects urban resilience. Cities 2024, 155, 105397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Q.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, L.; Chiu, Y.-H. How does the regional digital innovation ecosystem lead to high energy efficiency? An exploratory study based on fsQCA. Renew. Energy 2025, 253, 123602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Ren, G. Digitalization and firms’ innovation efficiency: Do corporate social responsibility and irresponsibility matter? J. Technol. Transf. 2025, 50, 856–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, S.; Lee, J.; Osgood, I.; Park, S. Rapidly innovating firms: Patent lifecycle and support for trade and IP enforcement. Rev. Int. Polit. Econ. 2025, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Du, M.; Wang, D. Is there heterogeneity and moderating effect of carbon trading pilot in promoting total factor productivity? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 4290–4309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Si, R.; Wang, Y.; Cao, M.; Wen, H. Does green technology innovation promote green economic growth?–Examining regional heterogeneity between resource-based and non-resource-based cities. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 94, 103406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Liang, J. Impact of transportation hubs on urban economic resilience: Evidence from national comprehensive transportation hub cities. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2026, 203, 104751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GTFEE | 4760 | 0.3228 | 0.1333 | 0.0213 | 1.1770 |

| Tech | 4760 | 0.2840 | 0.4065 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 |

| POP | 4760 | 5.8732 | 0.6926 | 3.1267 | 8.0747 |

| FDI | 4760 | 9.6692 | 2.2127 | 0.0000 | 14.941 |

| GOV | 4760 | 0.0192 | 0.0347 | 0.0000 | 0.9362 |

| URBAN | 4760 | 2.9092 | 2.0176 | 0.3161 | 33.0820 |

| TI | 4760 | 0.5330 | 0.1714 | 0.1151 | 3.0144 |

| MK | 4760 | 11.161 | 3.0773 | 3.0371 | 21.265 |

| IS | 4760 | 0.4560 | 0.1106 | 0.0000 | 0.8564 |

| GTIF | 4760 | 0.0851 | 0.2249 | 0.0000 | 4.3657 |

| GTIS | 4760 | 0.3915 | 0.7160 | 0.0000 | 8.3532 |

| HC | 4760 | 0.0020 | 0.0026 | 0.0000 | 0.0327 |

| Variable | GTFEE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Tech | 0.0899 *** (0.0046) | 0.0127 *** (0.0045) | 0.0447 *** (0.0047) | 0.0124 *** (0.0045) |

| Constant | 0.3041 *** (0.0021) | 0.2212 *** (0.0048) | −0.1112 *** (0.0184) | 0.0603 (0.0667) |

| Controls | NO | NO | YES | YES |

| Year FE | NO | YES | NO | YES |

| City FE | NO | YES | NO | YES |

| N | 4760 | 4760 | 4760 | 4760 |

| R2 | 0.0751 | 0.2652 | 0.2055 | 0.2755 |

| Bacon Decompose | Estimation Coefficient | Weight |

|---|---|---|

| Time-varying processing group | −0.0102 | 0.0811 |

| Never vs. time-varying | 0.0147 | 0.9012 |

| Within | 0.0024 | 0.0177 |

| Variable | PSM-DID | Entropy Balancing |

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| Tech | 0.0138 ** (0.0066) | 0.0375 *** (0.0048) |

| Constant | 0.0197 (0.0506) | 0.0634 *** (0.0186) |

| Controls | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES |

| City FE | YES | YES |

| N | 2255 | 2255 |

| R2 | 0.2769 | 0.1952 |

| Variable | Mean-Year Joint Fixed | Trim 1% | Trim 5% | Variable Replacement | Exogeneity Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Tech | 0.0127 *** (0.0045) | 0.0105 ** (0.0044) | 0.0086 *** (0.0027) | 0.1460 *** (0.0119) | |

| GTFEE | 0.3497 (0.6674) | ||||

| Constant | 0.2212 *** (0.0048) | 0.1081 (0.0700) | 0.0718 (0.0522) | 0.1664 ** (0.0659) | −7.4611 *** (1.1124) |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| City FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 4760 | 4760 | 4760 | 4760 | 3612 |

| R2 | 0.2652 | 0.2871 | 0.4032 | 0.2981 | 0.1200 |

| Variable | Low-carbon City Pilot Policy | Smart City Pilot Policy | Carbon Trading City Pilot Policy |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Tech | 0.0125 *** (0.0045) | 0.0123 *** (0.0045) | 0.0157 *** (0.0048) |

| Constant | 0.0583 (0.0669) | 0.0573 (0.0668) | 0.0548 (0.0667) |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES |

| City FE | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 4760 | 4760 | 4760 |

| R2 | 0.2755 | 0.2756 | 0.2762 |

| Variable | IS | GTIF | GTIS | HC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Tech | 0.0064 ** (0.0025) | 0.0535 *** (0.0077) | 0.2197 *** (0.0225) | 0.0004 *** (0.0000) |

| Constant | 0.4660 *** (0.0370) | −1.9879 *** (0.1135) | −6.9184 *** (0.3325) | −0.0002 (0.0006) |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| City FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 4760 | 4760 | 4760 | 4760 |

| R2 | 0.5106 | 0.3083 | 0.5139 | 0.1976 |

| Transmission Channels | Direct Effect | IS Effect | GTIF Effect | GTIS Effect | HC Effect | Total Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute contribution | 0.0124 | 0.0005 | 0.0081 | 0.0085 | 0.0036 | 0.0331 |

| Relative contribution | 37.46% | 1.51% | 24.47% | 25.68% | 10.88% | 100% |

| Variable | GTFEE | IS | GTIF | GTIS | HC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Tech | −0.0107 * (0.0056) | 0.0131 *** (0.0031) | 0.0086 (0.0096) | −0.0113 (0.0277) | 0.0002 *** (0.0000) |

| MK | −0.0156 *** (0.0023) | −0.0005 (0.0013) | −0.0209 *** (0.0040) | −0.0413 *** (0.0115) | −0.0000 * (0.0000) |

| Tech × MK | 0.0106 *** (0.0016) | −0.0031 *** (0.0009) | 0.0206 *** (0.0027) | 0.1060 *** (0.0077) | 0.0001 *** (0.0000) |

| Constant | 0.0768 (0.0664) | 0.4612 *** (0.0370) | −1.9559 *** (0.1128) | −6.7537 *** (0.3258) | −0.0000 (0.0005) |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| City FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| N | 4760 | 4760 | 4760 | 4760 | 4760 |

| R2 | 0.2829 | 0.5119 | 0.3175 | 0.5338 | 0.2060 |

| Indicators | Calculation Method | Data Source | Weight | Attribute |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internet penetration rate | Number of internet users per 100 people | China Urban Statistical Yearbook | 0.1986 | positive |

| Staffing situation | Percentage of computer service and software personnel | China Urban Statistical Yearbook | 0.2062 | positive |

| Output situation | Per capita total telecommunications business volume | China Urban Statistical Yearbook | 0.2012 | positive |

| Mobile phone penetration rate | Number of mobile phone subscribers per 100 people | China Urban Statistical Yearbook | 0.1962 | positive |

| Digital inclusive finance | Digital inclusive finance index | Jointly developed by the digital finance research center at Peking University and Ant Financial Group | 0.1978 | positive |

| Variable | Digital Economy | IP Protection |

| (1) | (2) | |

| Tech | 0.0092 ** (0.0046) | 0.0092 ** (0.0046) |

| DIG | −0.0724 ** (0.0289) | |

| IP | 0.0091 * (0.0049) | |

| Tech × DIG | 0.1081 *** (0.0258) | |

| Tech × IP | 0.0222 ** (0.0087) | |

| Constant | 0.1286 * (0.0683) | 0.0716 (0.0669) |

| Controls | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES |

| City FE | YES | YES |

| N | 4760 | 4760 |

| R2 | 0.2793 | 0.2775 |

| Variable | Resource-Based Cities | Nonresource-Based Cities |

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| Tech | 0.0018 (0.0062) | 0.0129 ** (0.0062) |

| Constant | 0.0159 (0.0629) | 0.0965 (0.0879) |

| Controls | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES |

| City FE | YES | YES |

| N | 1921 | 2839 |

| R2 | 0.2342 | 0.3175 |

| Variable | Transport Hub Cities | Nontransport Hub Cities |

|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | |

| Tech | 0.0898 *** (0.0191) | 0.0036 (0.0046) |

| Constant | 0.4185 ** (0.1779) | 0.2280 *** (0.0845) |

| Controls | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES |

| City FE | YES | YES |

| N | 323 | 4437 |

| R2 | 0.6221 | 0.2571 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wu, S.; Chen, D.; Tang, T. The Impact of Technology Transfer on Green Total Factor Energy Efficiency: Evidence from the Establishment of National Technology Transfer Centers. Sustainability 2026, 18, 751. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020751

Wu S, Chen D, Tang T. The Impact of Technology Transfer on Green Total Factor Energy Efficiency: Evidence from the Establishment of National Technology Transfer Centers. Sustainability. 2026; 18(2):751. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020751

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Suting, Danni Chen, and Tianwei Tang. 2026. "The Impact of Technology Transfer on Green Total Factor Energy Efficiency: Evidence from the Establishment of National Technology Transfer Centers" Sustainability 18, no. 2: 751. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020751

APA StyleWu, S., Chen, D., & Tang, T. (2026). The Impact of Technology Transfer on Green Total Factor Energy Efficiency: Evidence from the Establishment of National Technology Transfer Centers. Sustainability, 18(2), 751. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020751