1. Introduction

Although national development policy models are well developed, regional aspects have mostly been treated as derivatives of national policies—typically through location theory—with insufficient contribution from regional systems analysis.

National development policies are naturally oriented toward urban and metropolitan factors, whereas rural or remote regions (generally with smaller populations) are often treated as marginal to the development process. Recent technological advances, which have driven innovation-led and geographically concentrated growth [

1], pose significant challenges to the economic and social sustainability of non-metropolitan regions. Initially, theoretical and empirical research relied on location theories to explain the spatial distribution of economic activity. A subsequent step considered regional systems (RS) or regional innovation systems (RIS) as elements in achieving spatial balance.

This article develops a model that integrates locational and regional-system approaches and introduces an explicit preliminary step focused on practical implementation. The approach may be viewed as an adaptation of the widely used national computable general equilibrium (CGE) framework to regional specificities. Whereas standard CGE models emphasize economy-wide consistency through interlinked markets and equilibrium conditions, they typically abstract from spatial heterogeneity and localized development mechanisms. The present model therefore incorporates equations that capture regional-system dynamics and the effects of locational factors, and treats as key dependent variables a set of alternative objectives to be pursued through regional development. Regarding the locational approach, the debate over the spatial distribution of economic activity remains unresolved, with no final consensus yet achieved. Krugman [

2] framed the issue in terms of centripetal forces, which attract certain types of activities to metropolitan cores, and centrifugal forces, which push some activities toward peripheral or rural locations. Globalization, technological change, and improved communications can strengthen centrifugal forces and disperse production [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Return to scale is also recently questioned [

7]. A recent review of spatial economics shows that better digital connectivity allows certain peripheral regions to enter knowledge-intensive niches despite their distance from core cities [

8]. Other empirical work, however, finds the resulting dispersion modest [

9]. Classic studies likewise reach no consensus on regional convergence versus divergence [

10,

11,

12,

13].

Policy assessment at the national level typically relies on computable general-equilibrium (CGE) models. These models specify quantitative links among macroeconomic variables, but they treat regions as largely passive recipients of centrally determined policies. National objectives—GDP growth, employment, consumption, public expenditure, and investment—while regions are folded into the national model as passive responders to centrally determined policies. As a result, the model’s objective function is optimized at the national level, which does not necessarily coincide with regional welfare. Although region-related variables (e.g., investment incentives) can be included, the internal dynamics of regional systems are generally absent.

Recent scholarship calls for regions to be recognized as active agents in development and for closer coordination between national and regional strategies [

14]. Furthermore, the region is expected to be proactive in the process of its own development planning, rejecting the approach of centrally regional planning by the national level [

15].

The growing centrality of innovation as a driver of growth—and its uneven spatial impacts [

16,

17] has fueled interest in regional-system (RS) and regional-innovation-system (RIS) frameworks [

18,

19,

20,

21]. Regional systems are analyzed in terms of specific local factors, including organizations and firms’ activities [

22] as well as natural environment as an actor [

23], although there is yet no methodology for regional sustainability assessment [

24]. Recent OECD work on place-based policy likewise stresses that territorial context is critical for competitiveness and resilience, advocating multilevel strategies that mobilize local assets [

25]. Yet key issues remain unresolved, including how to define a region [

26] or identify entrepreneurs and inventors [

27].

The objective of this study is to devise a model for the practical evaluation of alternative policy measures to support sustainable social and economic development in a region. Although there is still no consensus about the structure and functioning of a regional system (RS), the concept of the existence of a RS and of its importance in the process of economic development is widely acknowledged. This article seeks to contribute to the advance of this concept in two ways.

First, it aspires to make a first step in the conversion of the theoretical RS concept into practical implementation by outlining a regional-level general-equilibrium model that embodies this perspective and supports regional policymaking. Such a regional economic development (RED) model is expected to accommodate different versions of regional systems.

Second, we add an important element that was not explicitly included in analyses of regional systems in the literature, the distinction between the optimization of the economy of the region and the optimization of the welfare of the resident population of the region.

Furthermore, both regional economic growth and population well-being should be considered from the perspective of social and regional sustainability. The various dimensions of sustainability—social, economic, and environmental—should be incorporated into a regional model, even though they cannot always be evaluated in precise quantitative terms. Regional growth may be driven by inward investment that generates substantial benefits for external stakeholders while simultaneously degrading local natural assets, effects that can often only be assessed approximately. Conversely, residents’ welfare may increase when commuting or remote-work opportunities in other regions are expanded through improved transport or digital infrastructure, yet such gains may again involve economic costs and environmental pressures.

The RED model rests on two core assumptions: (1) the region functions as an economic system with its own endogenous variables, and (2) reciprocal interactions link the region to other regions and to the national economy. Estimated for a specific territory, the model provides a decision-support tool for public regional policy. Its simulation capabilities allow policymakers to test alternative strategies ex ante, identify feasible targets and the policy mixes needed to reach them, and avoid costly irreversible mistakes.

Some quantitative sustainability variables are included in the model, such as quality of life as a function of increasing local income, and environmental quality as a function of lower air pollution levels resulting from the provision of employment opportunities outside the region (alongside the environmental impacts of transport investments). Other sustainability variables pose substantially greater difficulties for model inclusion because of the complexity of their quantitative measurement, such as the long-term benefits of environmental preservation measures.

Despite the many difficulties involved in modeling and empirically estimating all relevant factors, this article seeks to offer an instrument for bridging the gap between CGE models that treat regions as derivatives of national policy and models that focus on the internal development processes of regions. The Regional Economic Development (RED) model represents an initial step toward a fully fledged ‘regional CGE’ framework. It operationalizes an endogenous view of regional growth, avoiding the common practice of treating regions as exogenous appendages of the national economy—a particularly complex task given that any regional model must coexist with an overarching national economic framework.

We assume that such an endogenous view of regional growth can actually be integrated into a broader regional or national context and lead to a more effective development policy. The methodology will therefore first be the design of a set of equations based the suggested concept, followed by an analysis of this model with the prevailing models, and finally checking the results of the first steps in the partial implementation of this model.

2. Main Features of a Regional Economic Development (RED) Model

The RED model is proposed as an analytical alternative to both standard regional CGE implementations and RIS system-dynamics models. Regional CGE frameworks, typically based on SAM/IO structures and implemented through platforms such as REMI or GEMPACK, ensure economy-wide consistency but treat innovation and locational development forces in a largely exogenous manner. In contrast, RIS system-dynamics models provide rich representations of knowledge and learning processes but operate with limited macroeconomic closure. The RED model bridges these approaches by combining structural economic coherence with an explicit representation of endogenous locational and regional development mechanisms.

Unlike multi-regional input–output models, which are limited to descriptive flow accounting, and spatial CGE models, which emphasize price-mediated adjustments across regions, the RED model is explicitly development-oriented and embeds endogenous locational and structural transformation mechanisms. The RED framework also differs fundamentally from sustainability accounting systems—such as environmental–economic accounts and environmentally extended input–output models—which are designed primarily for monitoring resource use and environmental footprints. While these systems provide essential descriptive information on sustainability performance, they operate with fixed technologies and lack endogenous behavioral and structural adjustment mechanisms. In contrast, the RED model treats sustainability as a development constraint and as a policy objective within a fully articulated regional adjustment process.

The RED model combines the Regional System approach with location theory, adapting the CGE framework to a region rather than a nation. This adaptation requires at least three important reconsiderations.

First, the variables generally included in a CGE model (such as national growth, investment, and the supply and demand for labor) do not cover relevant factors at the regional level—such as local infrastructure and local human capital—which are typically addressed in Regional Systems (RS) analysis.

Second, the dimension of inter-regional relationships, which is not regularly considered in CGE models, is a major factor in the Regional Economic Development (RED) model. This includes variables such as distances between regions, access to labor from other regions, commuting, internal migration, and similar factors.

Third, the distinction between endogenous and exogenous variables in location theory does not necessarily align with the distinction made in Regional Systems. For example, the labor supply in a region is considered an exogenous variable in location theory, influencing the region’s attractiveness for economic activities, whereas in RS frameworks it is considered endogenous—shaped by labor demand in adjacent regions and by commuting or migration trends.

The main features of the Regional Economic Development (RED) model are described below, followed by the structure of the model and its main relevant equations.

a.

Endogenous private capital investment. The RED model treats private capital investment as an endogenous variable. Investment is a function of the expected rate of return, which itself depends on regional factors such as infrastructure, service availability, labor-force supply, and distance to markets. Capital-incentive policies (an exogenous variable) artificially raise the rate of return and can temporarily boost investment [

28]; however, once incentives expire, the effect often dissipates.

b.

Public infrastructure as a proactive policy instrument. National policy typically treats investment in physical infrastructure (roads, railways, utilities, etc.) as endogenous—a response to revealed regional demand. The RED model instead treats public infrastructure spending as (at least partly) exogenous: a deliberate, place-based stimulus for regional growth. Whereas the traditional approach provides infrastructure mostly after activity has expanded or is expected to expand, the regional approach invests in advance to trigger new activity. The efficacy of such investment has been widely debated [

29,

30,

31,

32].

c.

Human-capital investment as proactive policy. Public spending on education and skills is likewise primarily considered in the RED model as exogenous—a policy lever for raising productivity, employment, and income [

33]. Evidence from ten German lagging regions shows that targeted human-capital programs are now indispensable for translating structural funds into productivity gains [

5].

d. Dual demand channels. Regional development depends on both local and external demand for goods and services. The share of each that is supplied regionally is shaped by product characteristics, population size, distance to other markets, and the region’s competitive advantage.

e. Distinguishing “domestic” and “regional” product. Analogous to the GDP–GNP distinction, the domestic product is defined here as the output produced within the region (using local and imported factors—in-commuting workers and external capital investments), whereas the regional product is defined as the output generated by regional factors, regardless of where production occurs (by local resident population working in the region or out-commuting to other regions). The domestic product measures activity inside the region; the regional product proxies the welfare of its residents. The gap between the two reveals the degree of integration and dependence vis-à-vis other regions—an overlooked but crucial feature of the RED model.

f.

Endogenous productive structure. The sectoral composition of the domestic product (agriculture, industry, services) is endogenous, driven by factor availability and demand conditions, and it feeds back into income, employment, and growth. A detailed model should also capture firm size, location, and technology [

34].

3. Basic Structure of the RED Model: Four Blocks of Equations, Four Types of Variables

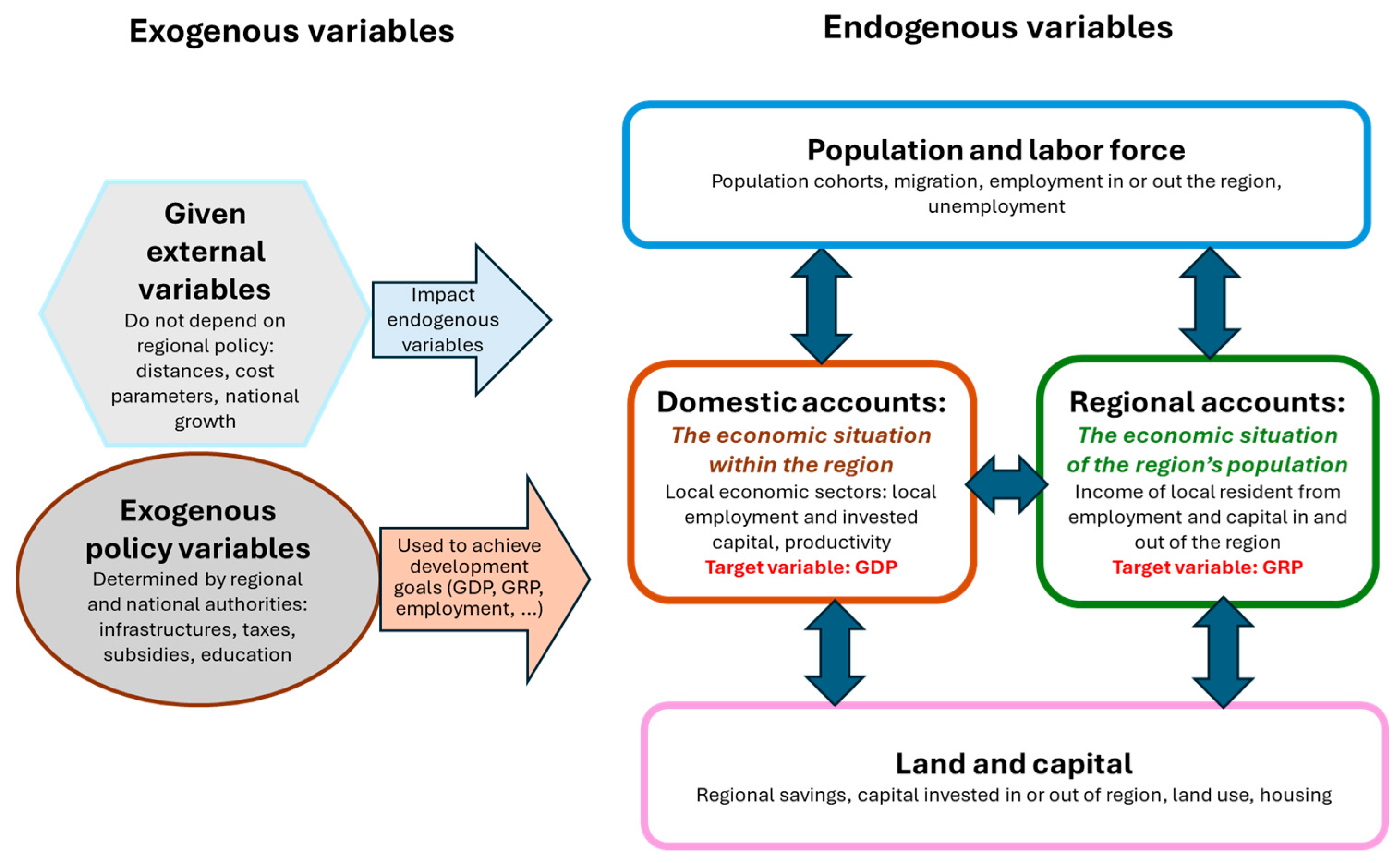

The RED model consists of a system of equations that expresses quantitatively the relations between the main factors (variables) in the region. The role of the system of equations is to enable simulations of policy changes and evaluations of their influence on the economy of the region. Consequently, the model would facilitate the optimization of a given development objective, while evaluating the implications on other objectives and on the regional economic structure. The basic structure of the model is illustrated in general terms in

Figure 1, and later in more detail in

Figure 2.

3.1. Four Types of Variables

All the variables of the system of equations can be classified into four main groups, two of which include exogenous variables, and the other two include endogenous variables. Exogenous variables are determined outside the model or set by policymakers; they influence the endogenous variables but are not themselves affected by them. Endogenous variables, by contrast, are determined within the system as functions of the model’s equations and the values of the exogenous variables.

3.1.1. Externally Given Variables (Exogenous)

These are exogenous variables—though the concept of ‘exogeneity’ is often debated—at both the national and regional levels. These variables are provided to the system and cannot be altered by policy, but they influence the economic development of the region. At the national level, such variables may include economic growth rates, inflation, exchange rates, taxes rates and regulations, demand elasticities, etc. At the regional level, those can be variables in the fields of fertility and mortality rates, distances, propensities to consume and save, and income elasticities of demand for various products. Such variables effectively define the regional context and may exert a substantial influence on the outcomes of the model. For example, a remote region may justify the adoption of incentives for local economic development, whereas a region located at a shorter distance from major centers may justify a policy focused on encouraging commuting. These variables are considered fixed constraints and define the boundaries of regional policy capabilities.

3.1.2. Policy Variables (Exogenous)

This second group of exogenous variables includes those whose values can be externally determined by policymakers, either at the national or regional level. Each set of values selected by policymakers represents a different policy intervention. Examples include regional taxes and regulations (as opposed to national taxes, which are assumed to be fixed from the region’s perspective), land allocation policies, and regional public expenditures on infrastructure or education and training.

3.1.3. Target Variables (Endogenous)

Endogenous variables are divided into two groups: target variables and economic structure variables. Target variables represent the final objectives to be achieved by the intervention in the regional economy. These include basically two alternatives: growth of the economy of the region as represented by the regional GDP, or growth of the welfare of the population of the region, as represented by the regional GRP. Other measures may be reduction in unemployment, per capita income growth, levels of regional economic integration and dependence, and possibly demographic growth (as influenced by internal migration balances). The selection of targets depends on specific regional conditions. Conflicts or complementarities may arise between targets—though this issue is beyond the scope of this article.

3.1.4. Economic Structure Variables (Endogenous)

This final group of endogenous variables describes how adopted policies affect key characteristics of regional development. One such area is the economic structure shaped by regional policy. However, the relationship can also be bidirectional: prevailing structures may influence investment attractiveness. This group includes variables such as the employment distribution across sectors (agriculture, industry, services), capital intensity, and skill levels. It also encompasses physical changes in the region-land use, housing density, and open space allocation.

A strong interrelationship exists between structural and target variables. Different development objectives often correspond with specific structural outcomes. For example, policies aimed at minimizing unemployment may increase the share of labor-intensive industrial activities.

3.2. Four Blocks of Equations

The four types of variables described above are interconnected through equations that fall into two categories. The first includes identities—for example, unemployment equals the labor force minus employment, or disposable income equals gross income minus taxes plus transfer payments. The second category includes behavioral equations, which model the response of one variable to changes in others. Examples include production functions or demand equations. This paper does not offer separate empirical estimates for these coefficients; instead, it relies on established values from economic theory, such as production coefficients, input-output ratios, demand elasticities, demographic rates, tested through a process of calibration.

The model equations are organized into four major blocks, represented by the four rectangles in

Figure 1. All four blocks include all endogenous variables, and each contains equations representing the relationships among the relevant endogenous variables, as well as their dependence on exogenous variables shown on the left side of

Figure 1. Two blocks pertain primarily to production factor determination. These are based on widely recognized standard production functions, such as the Cobb–Douglas function, in which output is determined by labor input and capital. One represents labor force and population (upper rectangle in

Figure 1). The equations in this block (detailed in the following section) describe how variables such as population cohorts, labor force employment inside or outside the region, and unemployment depend on other endogenous and exogenous variables—such as migration, labor demand within and outside the region, and related factors. The second block represents land and capital (lower rectangle) and covers land use, housing, regional capital, and similar elements.

The other two blocks (the two middle rectangles) concern output generation: one handles the ‘domestic accounts,’ while the other addresses ‘regional accounts.’ This distinction parallels the national accounting distinction between Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and Gross National Product (GNP).

The domestic accounts block includes variables related to economic activity within the region, generated using labor force and capital investments originating both within the region and from other regions. It is influenced by population demand and production factor supply (from the labor and population block and the land and capital block), as well as by exogenous factors such as distances, national growth (external variables), and subsidies or education (policy variables). It also reflects factors such as income earned by employed labor force imported from outside the region, capital inflows, and policy-induced public spending on infrastructure, education, and taxation. While all these are considered as variables that define the structure of the local economy, the last and most important is the target variable: the gross domestic product (GDP), as a measure of the economic level of the region.

The regional accounts block includes variables related to sustainability and to the social welfare of the local population resulting from the local labor force working and investing within and outside the region. This is indicated by the major target variable—the gross regional product (GRP)—and is heavily influenced by endogenous variables such as local availability of employment and exogenous variables such distances. Naturally, the GRP also influences other endogenous factors. For instance, employment outcomes affect regional unemployment rates and influence migration, thereby shaping population dynamics. Disposable income impacts regional savings and thus the local capital stock, while also influencing housing standards and land use. Moreover, higher income boosts local demand, which then feeds back into domestic economic activity.

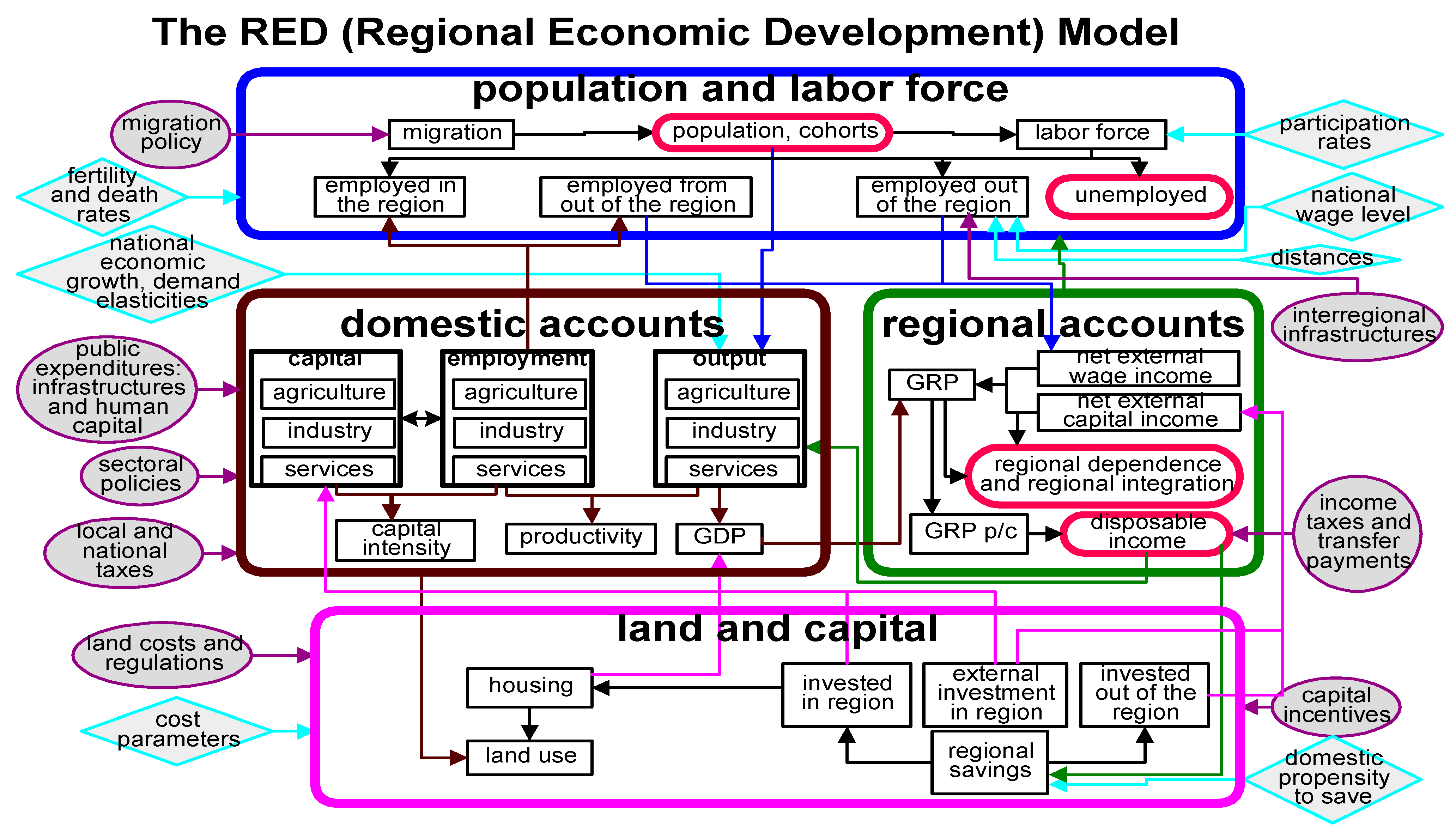

4. Main Model Functions

The following simplified scheme describes the general structure of the model. The four blocks are represented by the four major rectangles in the scheme. Each rectangle contains the main relevant endogenous variables. The endogenous variables that are considered as target variables are represented by round corners bold small rectangles, while the other endogenous variables are represented by regular small rectangles. The exogenous variables are located outside the block rectangles. Elliptic forms represent those exogenous variables that are considered as policy variables. Diamond forms represent those that are considered as externally given exogenous variables. Some of the main relationships between the variables are indicated by arrows. The functions will be presented in four groups, following the four blocks of the model. We shall restrict ourselves here to a few main functions as an illustration.

Some of the equations are identities—for example, total labor force equals the sum of employed workers inside and outside the region plus the unemployed labor force. Other equations are based on widely accepted rules, such as production functions such as the commonly used Cobb–Douglas function. However, the coefficients of such functions differ between countries and regions and should be evaluated for each specific region through a process suggested later. Some behavioral functions describe how a variable is expected to respond to given values of other variables. For example, the employment level of workers commuting from the region to other regions may depend on the availability of relevant jobs elsewhere, the quality of transportation infrastructure between regions, and wage differentials. Here again, the coefficients of such an equation differ between regions and should be evaluated separately in each specific region, following the same process mentioned above.

4.1. Population and Labor Force

4.1.1. Population

The

population that is expected at a given time in the future (p

t) is a function of expected net migration each year (m

1…. m

t), and of birth and death rates at each age cohort. The following function represents a schematic illustration of the determination of population at time t.

where b

t and d

t are the expected numbers of births and deaths at year t.

Each year, population is a function of the population the year before, with the addition of net migration, and with the addition of natural growth. pt, pt−1 and mt are separately defined for each cohort, and the final population is the sum of all the population in all age cohorts.

Migration, in net values, is a function of migration policy, which can be formulated in terms of settling new immigrants in a certain region, or in terms of incentive policies such as direct subsidies to migrants for housing, tax deductions, etc. Migration can also be a function of the economic structure and of the economic conditions in the region in relation to other regions, in terms of unemployment and the level of disposable income:

where

mt is the number of net migrants at year t,

ut is unemployment gap between the region and the nation at year t, is the increase (or decrease) of the unemployment gap between year t − 1 and year t, and is the coefficient of influence of unemployment gap (expected to be negative).

dit is the gap of average disposable income at year t, is the increase in the gap in disposable income, and is the coefficient of influence of the income gap (expected to be positive).

St is the level of subsidies to migrants and αS is the coefficient of influence of subsidies (expected to be positive).

Again, this is a simplified presentation of the determination of the net number of migrants. In fact, migration at year t may be a function of unemployment and disposable income not only at year t but it can equally be a function of lagged values of those variables. It may also be a function of expected future values of those variables. In addition, we can expect to have two different functions, one for the incoming migrants and one for those who leave the region. The variables that influence each flow of migration may be different. The variable of migration can also be disintegrated into age cohorts, assuming that the coefficients of influence are different for various age groups.

4.1.2. Labor Force

Labor force is estimated as a function of the expected population at each age cohort, multiplied by the relevant participation rates. Again, it is assumed here that labor force participation rates are given as exogenous, but they may be assumed as endogenous, as they may be influenced by the demand in the region or by other factors such as education, or family income.

The resident labor force in the region at time t, lf

t, can be divided into the following groups:

: local labor force working in the region at time t.

: local labor force working outside the region at time t.

: unemployed labor force at time t.

The number of

resident labor force employed in the region,

, and in parallel, the number of

resident labor force working outside the region,

, are estimated as a function of the supply of employment, as determined later in the block of “domestic accounts”, and of the access to alternative employment in other regions. Access is evaluated in terms of communication infrastructures and of relevant supply of employment in other regions (weighted by distances):

where

is the supply of employment in the region, as defined by

total labor force working in the region, and will be determined at a later stage, in the presentation of the domestic accounts,

represents the supply of employment outside the region. A higher supply would lead to more employment of regional labor force outside the region (positive ), while it would lead to less employment of local labor force within the region (negative ). The supply of employment can be a weighted variable, including the influence of employment supply at different distances from the region.

represents the communication infrastructures that link the region with other regions. Again, is expected to be positive and is expected to be negative.

is the wage level ratio between the region and outside the region. Wages are considered here as exogenous, and it is assumed that there is no equal wage equilibrium between regions. is expected to be negative and is expected to be positive.

Finally, the coefficient is expected to be positive (more supply of employment in the region leads to more local labor force working within the region), while is expected to be negative (a higher supply of local employment decreases the demand for outside employment).

External labor force working in the region is defined as the difference between the total supply of employment within the region and the number of resident labor force employed in the region:

This implies that priority is given to local labor force for local employment (assuming other things equal), and that all demand for labor in the region that is not met by local labor force will be supplied by external workers.

The number of

unemployed is calculated as equal to the difference between labor force and the sum of resident labor force employed in the region and those employed out of the region:

4.2. Land and Capital

4.2.1. Capital

Just like the production factor labor, production factor capital is analyzed in terms of local capital (of resident population) that may be invested within the region or outside of the region, and in terms of capital invested in the region, by local investors or by external investors (All capital investments and all savings are defined in net terms, after depreciation). External investments in the region may be from private sources or from public sources. It is assumed that most of the public investments are for public infrastructures and therefore are considered as exogenous.

Regional savings (

) at any year n (n = 1… t) are a function of

disposable income of the population in the region (

) as will be determined later, and of the exogenous domestic average propensity to save (APS):

Accumulated regional savings from year 1 to year t can therefore be formulated as:

Total capital stock in the business sector that is required for the regional economic growth will be determined in the next block of equations, relating to domestic accounts. Total capital stock accumulated in each economic branch b at time t, defined later as

, can be provided by local savings or by external sources. The share of capital stocks originating from local savings as compared with the share of capital stocks from external sources is exogenously defined for each separate economic branch. Therefore:

where

represents the

capital stock from regional sources in economic branch b at time t, LSI

b is the exogenous local share of investments in branch b (b = 1… 32), and

is the capital investment in branch b at time t. It is expected that the share of regional investment would be relatively low in capital intensive industrial branches, and higher in economic activities that are initiated by local demand such as small-scale industries, local consumer services and housing.

Total capital stock invested within the region by local population in time t can therefore be formulated as:

Capital stocks invested out of the region by the local population (sometimes described as regional leakages) are defined as the difference between regional savings and regional savings invested in the region:

External business sector capital investment in each economic branch (from outside the region) in the region can be defined as:

and

total external business sector capital investment in the region:

Concluding the issue of capital investments in the region:

Business capital investment in the region (kt) is divided between investments from regional sources () and investments from external sources ().

The dependence of the region upon external investments is measured by the ratio .

The

total capital investments in the region (tk

t) include both business capital and public capital. If we assume that all infrastructures (INF

t) and human capital investments (HK

t) are made by the public sector:

4.2.2. Land

Land use is a function of growth of demand for housing (and for a lower housing density) and for economic activities. This is determined in a set of functions that will not be detailed here. Some are behavioral and describe the demand for higher housing standards as a function of income growth. Others are identities that determine land use as a function of exogenous policy variables regarding the building density: land costs and regulations about the allocation of land for specific uses (including open areas) and about the limits regarding the ratio between built area and land area. Open space is calculated as the difference between total land and land uses.

Changing the various policy variables regarding building densities may influence the changing proportions between the built area and the open space, or the proportions between land uses for housing and for economic purposes. A decrease in the open space area implies the need to allocate more municipal land to cities, or alternatively to devise policy parameters that would enable the conservation of open land. Those may be an increase in building densities in housing or in economic activity, a decrease in public allocation of urban services, or a decrease in incentives for migration to the region or for the attraction of economic activity (therefore increasing the dependence of local labor force on employment outside the region).

4.3. Domestic Accounts

The domestic accounts equations relate, as described above, to the economic activity that takes place within the region. The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of the region is equal to the product of economic activities within the region and of the value of dwellings (we consider here the product of the public sector as any other economic activity).

4.3.1. Output

The product, or output of the region is given for the base year. This model has no intention of evaluating a theoretical future equilibrium based on demand and supply factors, independently of the prevailing situation. The prevailing product in the various economic branches is assumed as a given present equilibrium, and the model focuses on expected changes in this equilibrium. In terms of output, projected growth rates are evaluated in terms of factors that influence the demand side, and factors that influence the supply side. At this first stage, the evaluation of growth rates of output should be considered as a measure of potentials, indicating the ability of each economic branch to grow in the region.

Output is divided in this model in two parts: output for regional market demand and output for external demand. Regional demand depends mainly upon regional changes in population and income. External demand is theoretically infinite, since the regional economy has access to all national and international markets. In practical terms, we assume the prevailing equilibrium is a measure of present revealed advantage of each branch in the external markets. Potential growth of output for external markets may therefore be a function of an increasing regional competitive advantage, as well as an increase in national demand.

Therefore,

output growth in each economic branch is estimated as a function of the expected regional and national growth in population and in disposable income, and as a function of expected changing competitiveness. Output growth in each branch may also be influenced by growth in other branches with which it has backward or forward linkages. The coefficients of each of those variables differ for each of the economic branches, expressing specific demand elasticities, the influence of distances, etc. For example, the growth of

agricultural output is mainly a function of national demand, and is mostly determined by national policy. Growth of

industrial output is also heavily determined by national parameters, but is also influenced by regional demand. The coefficients of regional demand (responding to changes in population and in disposable income) also differ between the various industrial branches. Food manufacturing may respond to changes in population (at the regional and at the national levels), but with a quite low coefficient for the income elasticity of demand, while high-tech industries may react with a higher sensitivity to income changes.

Services output is mostly a function of regional demand, again with differing coefficients for the different branches of services. Commercial services are expected to have a relatively high coefficient for growth in population and income within the region, while financial services respond mainly to growth in other economic branches (Guldmann and Wand [

35] have developed and empirically applied a model for the simulation of urban population and service employment distributions, as adaptation of the Garin–Lowry model).

Output growth in the region is estimated for each economic branch: 2 in agriculture, 20 in manufacturing industries, and 10 in services, a total of 32 economic branches. Total output is defined as the aggregate output of all branches, at any time t:

The total output of each economic branch is divided between the regional market and the external market. It is assumed that the proportions between the markets are known for the present, for each branch:

where

is total output of branch b at base year,

is the output for the regional market, and

is the output for external markets.

is the share of output of economic branch b which is sold to the local market (within the region) at the base year:

and at year t:

The annual growth rate of output of each branch b for regional demand

is estimated as a function of expected regional changes in population and in income, and as a function of output growth in other branches:

and represent the elasticities of demand for the output of branch b in relation to changes in population and in relation to changes in per capita disposable income.

and are the rate of growth of population and of income per capita in the region.

is the growth rate of output in branch b, and is a coefficient of influence of growth of one branch upon another (actually an input-output type of coefficient). For simplicity purposes, it is assumed that there is no reciprocity of influences between branches: financial and business services depend upon industrial activity (and not vice versa), food processing depends upon agricultural activity, building depends upon all other activities.

Expected regional demand in time t is therefore:

As to the external market:

where

is the annual growth rate of external demand for the output of branch b,

and are the rates of growth of population and disposable income for the nation.

expresses a competitiveness variable that represents the ability of each economic branch to increase its ability to compete on national and international market, as a result of a higher economic efficiency. This variable is estimated as a function of two elements of policy: one is improvements in the business environment such as increase in infrastructure intensity, human capital, incentives to capital, diminution of income taxes. The other is a direct incentive to specific economic branches:

where

is a policy variable representing the annual growth of public infrastructures per worker.

is a second policy variable representing the annual growth of human capital per worker.

is a third policy variable representing the annual growth in the rate of capital incentives, which may take the form of tax exemptions on capital investments, capital grants, etc. It should be indicated that this variable should take the value of 0 in the long term: a continuous increase in capital incentives is not rational. Moreover, existing regional capital incentives should be gradually eliminated after the region has reached the ability to compete with other regions.

is a fourth policy variable representing the average annual rate of diminution of income taxes.

coefficients represent the expected impact of each of those policy variables on the level of competitiveness of the region. The estimation of such parameters is quite complex and requires additional both theoretical and empirical elaboration. In the application of this model, approximate subjective evaluations have been used.

All those policy variables are implemented on a regional basis, and therefore are expected to affect all economic branches equally. However, the assumption made in this model may be altered and different coefficients can be attributed to the different branches.

is a branch specific policy variable and indicates specific public support to each economic branch. This variable has the value of 1 if no such support is provided, and a value higher than 1 when a specific branch is supported. It can be, for example, through a decision by government as a consumer to purchase goods from specific firms in the region. It can also be through a decision to support a given economic branch b indirectly or directly, for example, by the allocation of funds for research and development in certain activities, by special finance programs, by reaching international trade agreements for certain products, or by the promotion of specific economic projects.

The expected output potential for external markets of branch b in time t is therefore:

Summarizing the output equation, we can say that the regional output can grow in the future as a consequence of endogenous changes and of policy measures. Endogenously induced growth may be a result of:

- a.

Population growth in the region, and the resulting increase in demand, mainly in economic branches which are more sensitive to population (such as many personal services).

- b.

Growth of disposable income per capita, and the resulting increase in demand, mainly of locally produced products or services, with higher income elasticities of demand (such as education services, health services, financial services).

- c.

National or international growth of demand (through population or economic growth), affecting mostly those branches which are based on markets which are external to the region.

Policy measures that may lead to growth of output in the region may be:

- a.

Increasing competitiveness through the improvement of infrastructures, human capital, and through the diminution of taxes on capital and labor.

- b.

Promotion of specific economic branches by government, through specific support in finance, research and development, etc.

4.3.2. Production Function

On the supply side, output is estimated as a Cobb–Douglas type of production function, including as production factors:

capital and labor (endogenous variables, k and l) as well as public expenditures on infrastructures and human capital (exogenous policy variables, INF and HK):

The coefficients of this extended production function are based upon estimations made on the basis of Israeli data, by Bregman, Fuss and Regev [

36]. A major assumption is implied in this function: the coefficients of the production function (α, β, γ, δ) are the same in all economic branches. This of course is not necessarily true, and they should be changed whenever specific industry coefficients are available.

In terms of growth rates of output and of production factors, the equation can be written as:

Another assumption that is not necessarily acceptable is the independence between capital intensity and public investments in physical infrastructures and in human capital. In this model, we assume that public inputs in the region do lead to an increase in capital intensity in terms of the capital/output ratio:

where

is the rate of growth of the capital/output ratio,

is the rate of growth of infrastructures per worker, and

is the rate of growth of human capital per worker.

and

are coefficients of influence of infrastructure and human capital per worker on the capital/output ratio.

Given policy measures of increasing public expenditures on physical infrastructures and on human capital, growth of workers needed to achieve the regional output can be calculated. A few indicators can further be derived:

Capital intensity growth as defined by the ratio between capital and labor force:

This can be calculated for each economic branch, as stated above, and for the whole regional economy. The ratio for the whole regional economy can change as a result of capital intensity in each economic branch, and as a result of changes in the relative weight of the various economic branches.

Labor productivity growth is also defined as an identity, as the increase in the ratio between output and employment:

Again, this ratio is calculated for each economic branch and for the whole regional economy, and it can change as a result of a higher capital intensity, or as a result of higher public investments in infrastructures and human capital.

Capital productivity growth is defined in the same terms:

Finally, total factor productivity (tfp) is defined as the weighted average of capital productivity and labor productivity changes, using the weights of the relative coefficients in the production function:

4.3.3. GDP

GDP,

the gross domestic product, is defined as an identity, as the sum of the value added by the various economic branches (including the branches of public services) and the estimated annual value of ownership of dwellings (as usually conducted for the calculation of the gross domestic product at the national level). The value of ownership of dwellings is a function of population growth and of the increase in housing quality resulting from an increase in income. GDP and GDP per capita at year t can therefore be defined as:

where dw

t is the value of ownership of dwellings at time t, p

t is the population in the region, and (gdpc)

t in the GDP per capita in the region.

4.4. Regional Accounts

As explained above, the regional accounts provide a picture of the socio-economic situation of the population in the region, based both on domestic economic activity and from income of domestic production factors (labor and capital) outside the region. The activity of the local labor force outside its place of residence depends on endogenous variables such as the availability of employment within the region, and on exogenous variables such as distances, demand from other regions (external variables), and public investments in inter-regional infrastructure and education (policy variables). Such functions are complex and depend heavily on specific regional and national conditions. Here, we focus on defining the relevant derivatives of the regional accounts.

4.4.1. Regional Product and Income

The gross regional product (

GRP) is therefore calculated as an identity, as the sum of GDP and of the net external income (as a parallel to the gross national product, GNP).

then represents the gross regional product per capita.

is the gross regional product at year t, is the net external income from labor () and from capital (). Net external income from labor (or from capital) is defined as the difference between the income of labor from the region working outside the region (or of capital invested outside the region) and the income of external workers who come to work in the region (or of external capital invested in the region).

Disposable income (

), and the derived

disposable income per capita (

) are also defined as identities, and are calculated by the subtraction of income taxes and the addition of transfer payments (exogenous policy variables) to GRP:

where

is the rate of income tax at year t, and

is the amount of transfer payments at year t. Both

are considered exogenous policy variables. Transfer payments could also be defined as endogenously dependent of income, using the rate of payments as an exogenous parameter.

Disposable income can be considered as a direct indicator of the average economic welfare of the population in the region. It is important to denote that this variable, which may be influenced by income from external sources (production factors employed out of the region), may have an important effect on the domestic economic activity through increasing demand for local product. Disposable income, as well as other regional accounts measures, may also affect the population and labor force block, through the attraction of migrants from specific age groups.

4.4.2. Regional Dependence and Integration

Regional dependence and regional integration can be measured in terms of labor, in terms of capital or in terms of total income from labor and capital.

Regional dependence is therefore defined by three ratios:

is the regional dependence in labor, and is equal to the difference between labor force from the region occupied outside the region () and external labor force working in the region (), divided by total employed labor force (). A value of zero means a balance between employment supply within the region and the number of employed workers who reside in the region. A negative value indicates the existence of an employment dependence of the region upon employment supply in other regions, and a positive value indicates employment centrality of the region in relation to its vicinity.

is the regional dependence in capital investment and is calculated the same way as the regional dependence in labor.

represents the regional income dependence and expresses a combined function of labor and capital dependence. It is equal to the net external income from labor and from capital , divided by the gross regional product. A negative value indicates the existence of economic dependence of the region upon the economy of other regions. High negative values may represent regions which are very highly “housing oriented”, with high levels of commuting to work outside the region. A positive value indicates the existence of economic centrality of the region. This is the case for metropolitan regions, which provide employment and investment opportunities to other surrounding regions. Regional dependence could also be measured by another indicator: the ratio between GRP and GDP.

Regional integration is a measure of the level of economic relationship between the region and other regions. It is defined as the ratio between the total inter-regional flows of labor, capital and total income (external wage and capital income added to wage and capital income paid in the region to workers and capital from out of the region) and GRP:

represents the regional integration indicator for labor, represents the regional integration indicator for capital, and represents the regional integration indicator for income. Any value of zero indicates a completely isolated regional economy, and in this case the regional dependence indicator is naturally also zero. A high number indicates a high level of regional economic integration. High integration may be combined with high levels of dependence or of centrality or with a balanced structure.

To ensure that sustainability considerations are formally embedded within the core structure of the model, the land, capital, and accounts blocks can be augmented by explicit environmental state and pressure variables. Environmental state variables—such as natural land capacity, resource availability, or ecological carrying capacity—enter the land block as constraints on the feasible scale and spatial pattern of regional development. Environmental pressure variables—such as energy use, emissions intensity, or material throughput—are linked to production activity and capital accumulation within the capital block. Correspondingly, the regional accounting framework may be extended to record the associated environmental flows alongside standard economic transactions. This formulation ensures that environmental objectives, which are already specified at the level of policy levers and targets, are treated endogenously within the regional adjustment mechanism rather than as purely external constraints.

5. Using the RED Model

5.1. Empirical Challenge

The practical implementation of CGEs at the national level is challenging, and their parameters are often not easily evaluated. The structure of the RED model is even more complex than that of a standard CGE, presenting an even greater challenge. The model devised here should therefore be considered a detailed framework for evaluating alternative policy measures aimed at regional development. To turn it into a practical policy tool, two pre-conditions must be met: (i) all coefficients must be evaluated, and (ii) baseline values for every variable must be known for each region being analyzed. Only under these circumstances can we run forward-looking simulations by adjusting exogenous (policy-controlled) variables. These differ naturally and are specific to each region.

Yet many baseline values are not available, and behavioral parameters—production elasticities, demand curves, migration responses—are rarely available at the regional scale. While identities pose no difficulty, rigorous econometric estimation is often impossible because regional time-series or disaggregated cross-sectional data do not always exist.

A pragmatic, three-step solution has proved workable in several Israeli regions:

** Proxy estimation **—Populate the model with coefficients drawn from the literature (production-function parameters, input-output tables, demand elasticities) and with national statistics (cost shares, fertility and mortality rates), supplemented by planners’ informed judgements.

** Calibration **—Iteratively adjust those coefficients so that the model reproduces recent observed outcomes—e.g., adapt national fertility coefficients to match the region’s actual birth and death counts.

** Selective simplification **—Where neither data nor proxies suffice, drop or merge equations, at the cost of a lower accuracy level.

5.2. Simulations and Iterations

Given p policy variables, t target variables, and s structural variables, with (t + s) endogenous equations, assigning a value vector to the * p * policy variables yields a unique solution for the entire system—hence, a distinct policy scenario. Policymakers then may compare outcomes across scenarios, weighing progress toward targets against structural side-effects.

To highlight the practical decision-support implications of the RED framework, we present in the next table a compact benchmark comparison with national CGE models and region-as-satellite approaches. The

Table 1 focuses on policy decision criteria, identification of winners and losers, and the speed with which policy-relevant insights can be obtained. The comparison illustrates that RED constitutes a distinct place-based policy framework rather than a simple regional disaggregation of national models.

5.3. Guidelines for the Iterative Process

Each run produces three result vectors—policy, targets, structure—prompting a new round of adjustments. Key considerations include:

5.3.1. Target Variables

There may be a possible conflict between the different targets: a policy to promote the achievement of one of the targets may imply a constraint in the achievement of another target. A first case may be that a rapid increase in disposable income cannot be achieved if the target of decreasing regional unemployment dependence is given a high priority: Increasing domestic product may be seriously constrained by a shortage of necessary physical infrastructures and consequently require heavy investment in infrastructures. Therefore a rapid increase in income per capita could be achieved by increasing the dependence on external employment.

A second and parallel case could be a situation where the vicinity of the region may offer a wide variety of employment opportunities. Therefore a most efficient policy would be the improvement of roads and public transportation to outside the region, thus increasing the employment dependency of the region.

A third case is the possible conflict between achieving a low level of unemployment and a high level of income per capita or a high level of employment independence. Increasing the number of workers in the region may require a policy of subsidies to labor-intensive activities, generally involving a lower level of labor income, and a parallel lower level of production technology. Increasing the number of workers may also be inconsistent with a target of providing most of the employment within the region: Less unemployment would then mean more dependence on external employment.

5.3.2. Economic Structure Variables

Each scenario of economic policy leads to the achievement of given development targets through the induction of changes in the regional demographic, physical and economic structures. Even in the case the analysis of policy variables and of target variables leads to acceptable results, the implications upon regional structures may be unacceptable or not feasible. Here are a few questions that could be asked in the evaluation process.

- a.

What are the expected changes in the regional economic structure, in terms of distribution of employment between the various economic branches? Is the relative weight of industrial employment too high in terms of ecological implications? Does the distribution of expected employment provide appropriate levels of skills and of wages? Does the whole economic structure provide a basis for long term endogenous growth?

- b.

Is the rate of growth of labor productivity feasible? Setting the targets results in the determination of the growth of both the product and the employment, and consequently the growth of product per worker (labor productivity). If the labor productivity growth in the region, which is necessary in order to enable the achievement of the development targets, is too high, targets should be reevaluated. If it is too low, the target of economic growth may have been too modest.

Practical testing of this model as a whole is quite challenging. Some tentative applications made by a few public institutions, using partial available data, have led to interesting results. A project of rural industrialization in the Northeast of Brazil analyzed the potential of local regional development as an alternative to the dependence on activities of external investors, exploiting local workers for mostly external benefits [

37,

38]. The partial use of the RED model enabled the analysis of potential local entrepreneurships oriented to local and external consumers, such as new or improved agricultural processes, or small or medium enterprises. The model also identified the trade-off between alternative public policies, leading to the optimization of employment against the optimization of income in the area. In the case of Israel, the model permitted an evaluation of alternative policies for the development of peripheral regions, within the context of the national trend of innovation-led economic growth [

39]. Instead of the “colonialist” type of development in peripheral regions based on investments by national business leaders, options of locally based innovation initiatives were analyzed, based on local resources and on local as well as national markets and investments. Similar RED-inspired principles have also been applied in work on innovation and entrepreneurship for sustainable development in Ethiopia [

40].

6. Conclusions

The RED model responds to the growing need to move beyond nationally aggregated CGE frameworks toward an explicitly regional, endogenous view of development, particularly in innovation-driven and spatially unequal economies.

Structured in four interlinked blocks, the RED model enables policymakers to simulate how alternative policy packages affect regional economic performance, population dynamics, spatial structure, and welfare outcomes before implementation.

The model explicitly differentiates between maximizing regional economic output and maximizing the welfare of resident populations—an essential distinction for peripheral regions with significant inter-regional commuting and external capital ownership.

RED allows direct comparison of contrasting strategies, such as capital incentives for external investors versus long-term public investment in local human capital, highlighting differences in distributional effects, sustainability, and long-run welfare.

Policies that improve access between peripheral regions and metropolitan cores (transport, digital infrastructure) can raise welfare and employment but may also intensify internal inequality and selective out-migration—effects that RED is designed to make explicit.

The model supports simultaneous evaluation of economic growth, social change, and sustainability objectives, enabling policymakers to assess long-term trade-offs rather than pursue single-target optimization.

RED is not a ready-made software package; it requires region-specific calibration of parameters and careful interpretation of results, especially given data limitations, aggregation constraints, and the current partial specification of sustainability targets.

Owing to its modular architecture, the RED framework can be progressively extended with refined behavioral equations, richer inter-regional dynamics, ecological constraints, and resilience indicators, offering a scalable pathway from place-based policy rhetoric to operational, evidence-driven regional strategy.