Preparation of Alkali–Fe-Modified Biochar from Agricultural Waste for Remediation of Cadmium-Contaminated Soil and Water

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.2. Preparation and Modification of Biochar

2.2.1. Preparation of Raw Biochar

2.2.2. Preparation of Alkali–Iron-Modified Biochar

2.3. Characterization and Analysis

2.4. Adsorption Experiment

2.4.1. Adsorption Kinetics

2.4.2. Adsorption Isotherms

2.4.3. Adsorption Thermodynamics

2.5. Soil Incubation Experiment for Heavy Metal Remediation

2.6. Determination of Soil-Related Indexes

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of the Biochar

3.1.1. Basic Characteristics of Biochar

3.1.2. Microstructure of Biochar

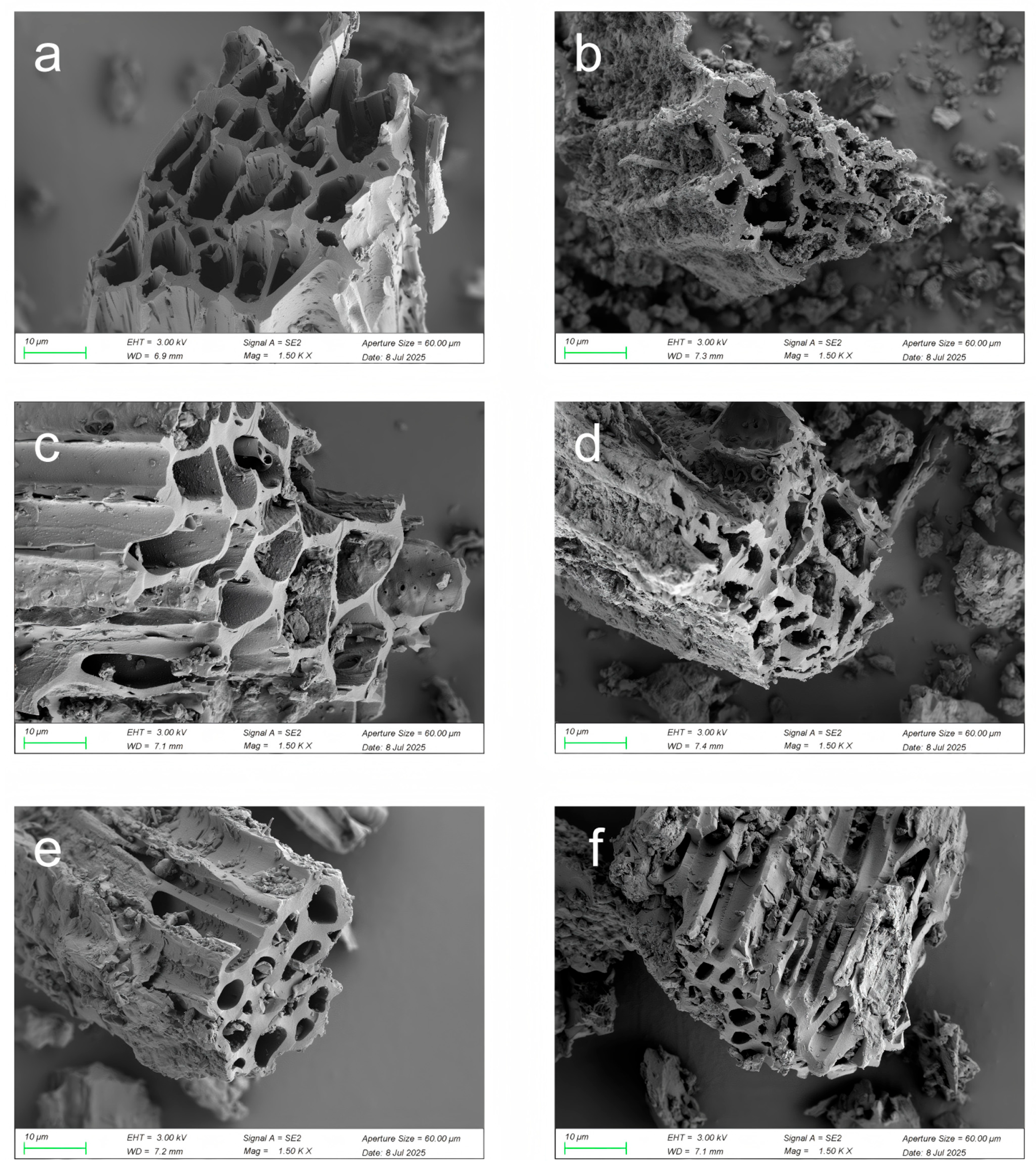

- Surface morphology analysis

- 2.

- Specific surface area and pore structure analysis

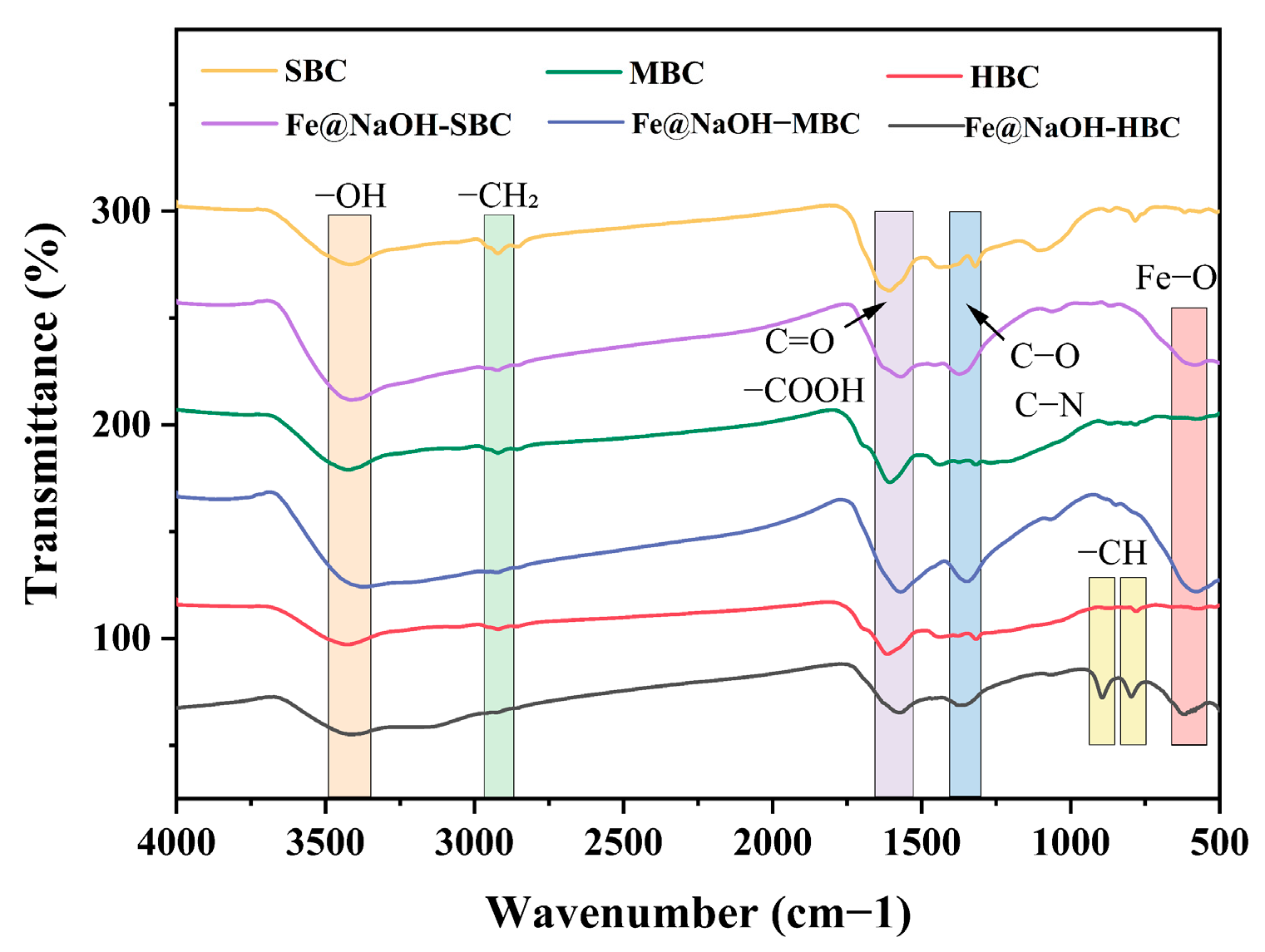

3.1.3. FTIR Analysis

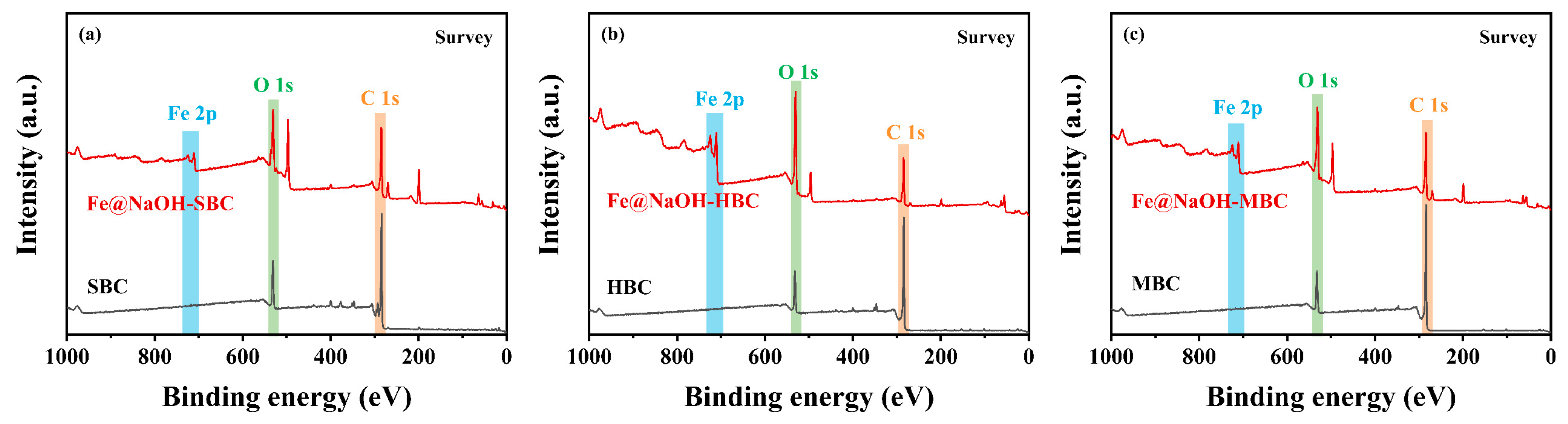

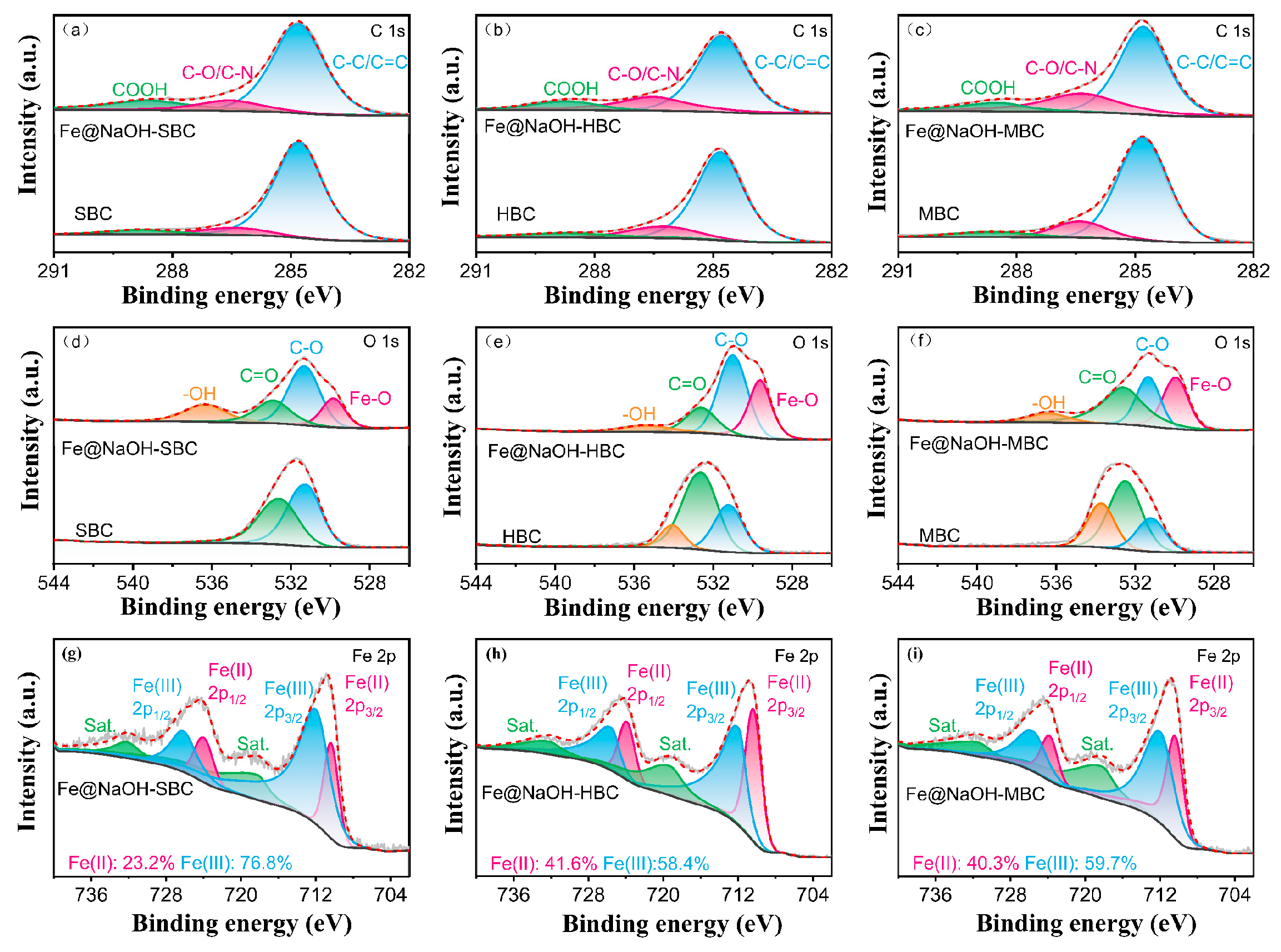

3.1.4. XPS Analysis

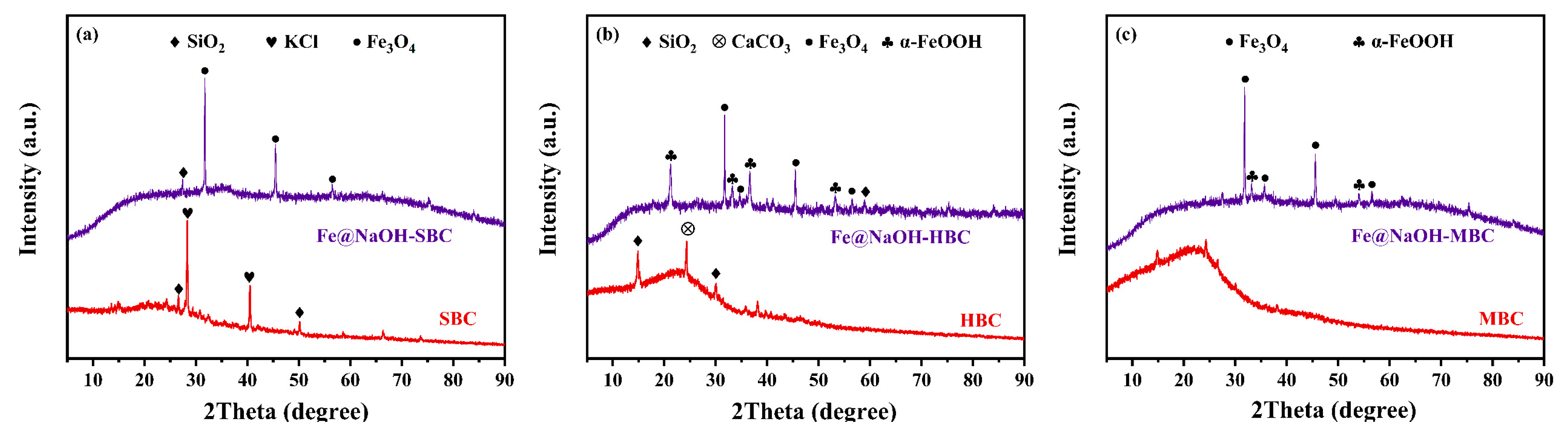

3.1.5. XRD Analysis

3.2. Adsorption of Cd(II) from Aqueous Solution

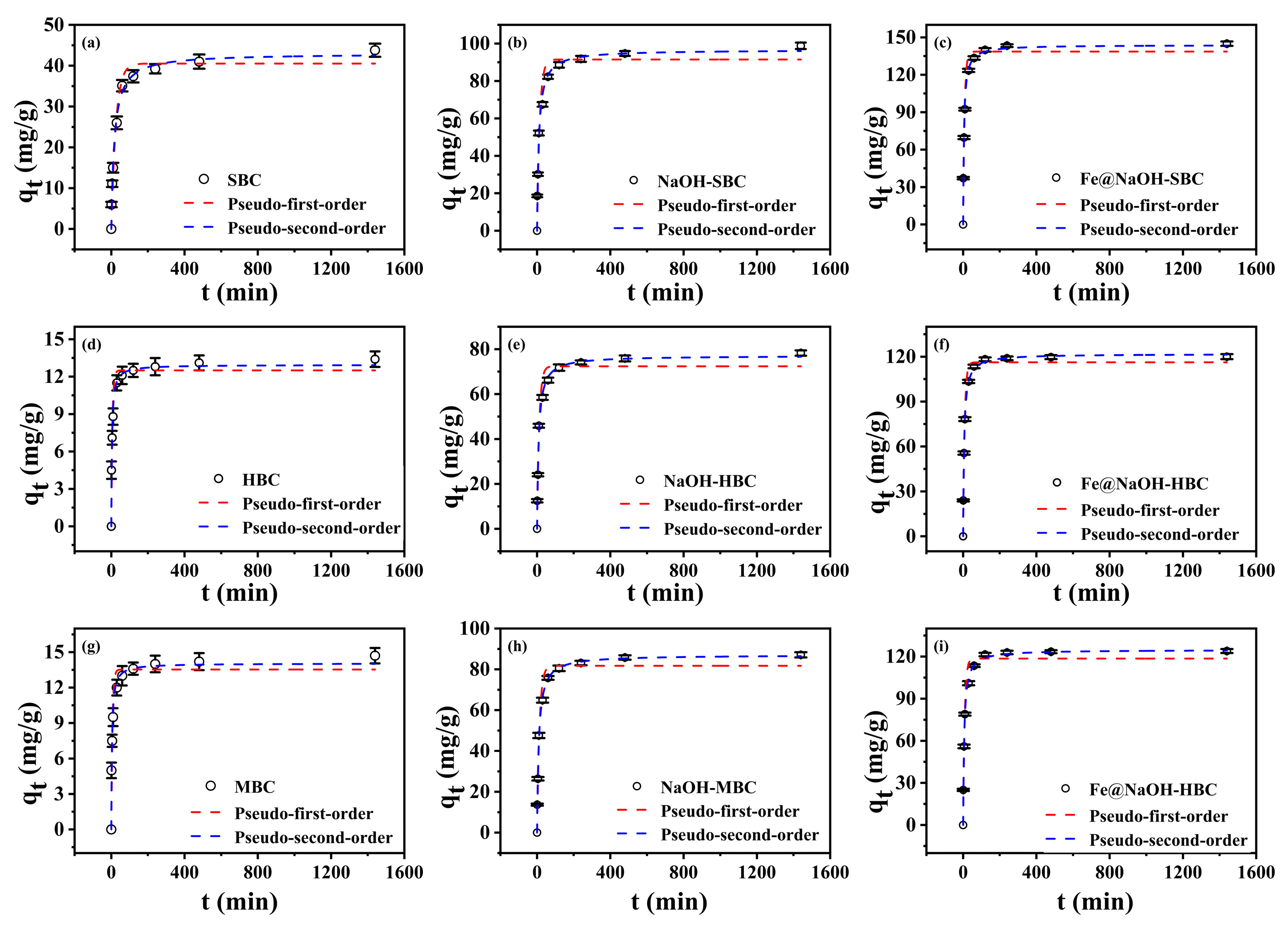

3.2.1. Adsorption Kinetics

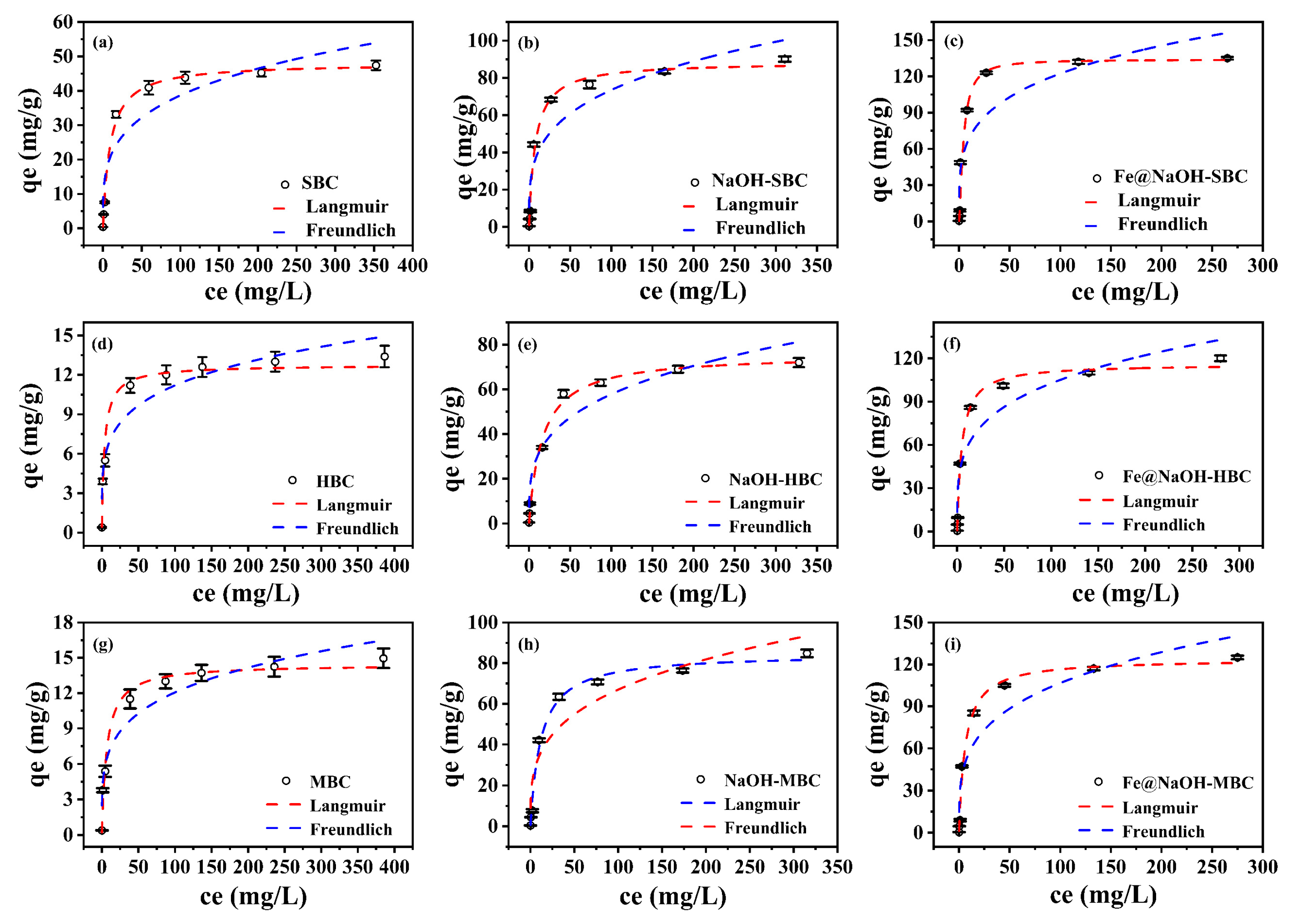

3.2.2. Adsorption Isotherms

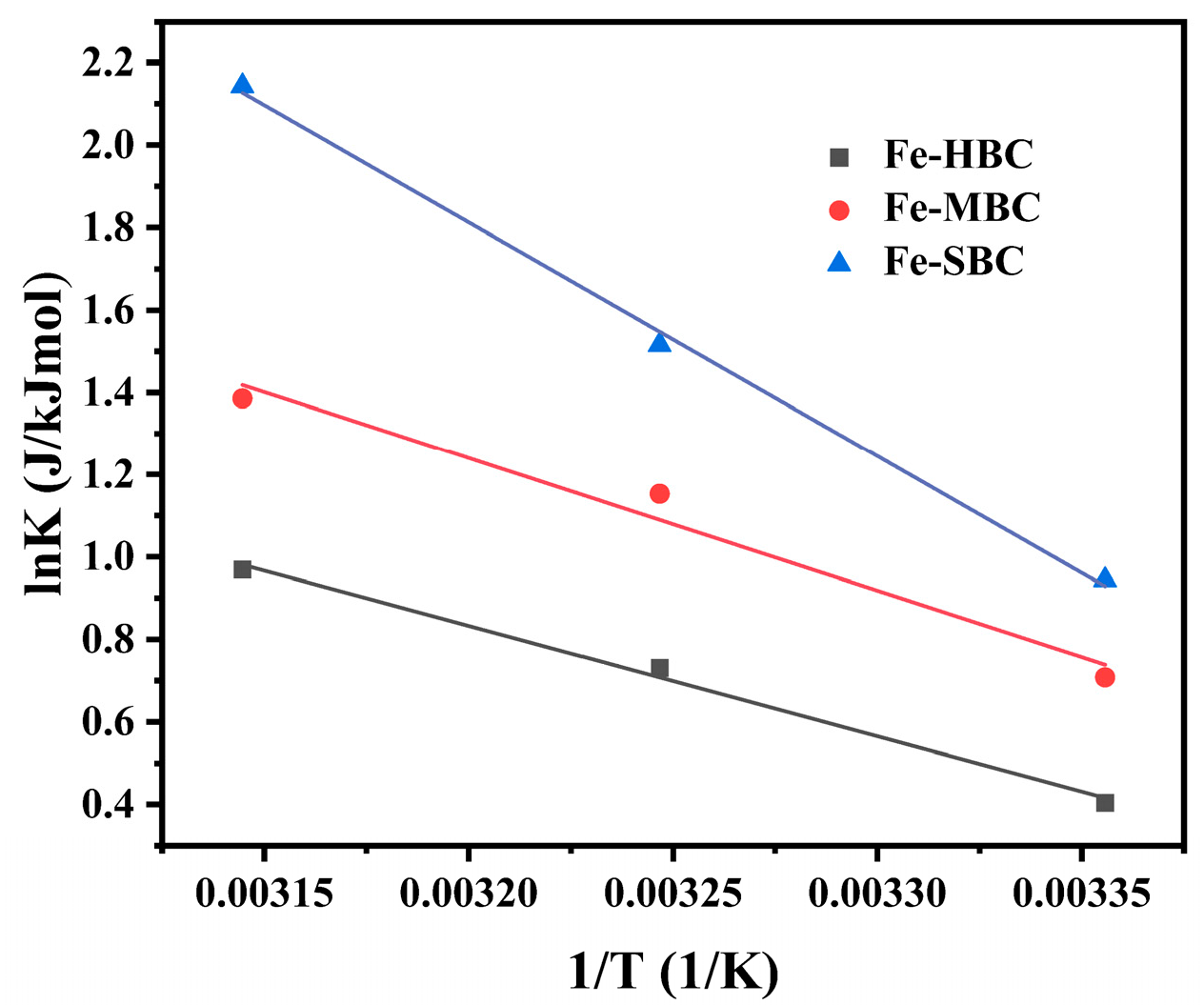

3.2.3. Adsorption Thermodynamics

3.3. Remediation of Cd(II) in Soil

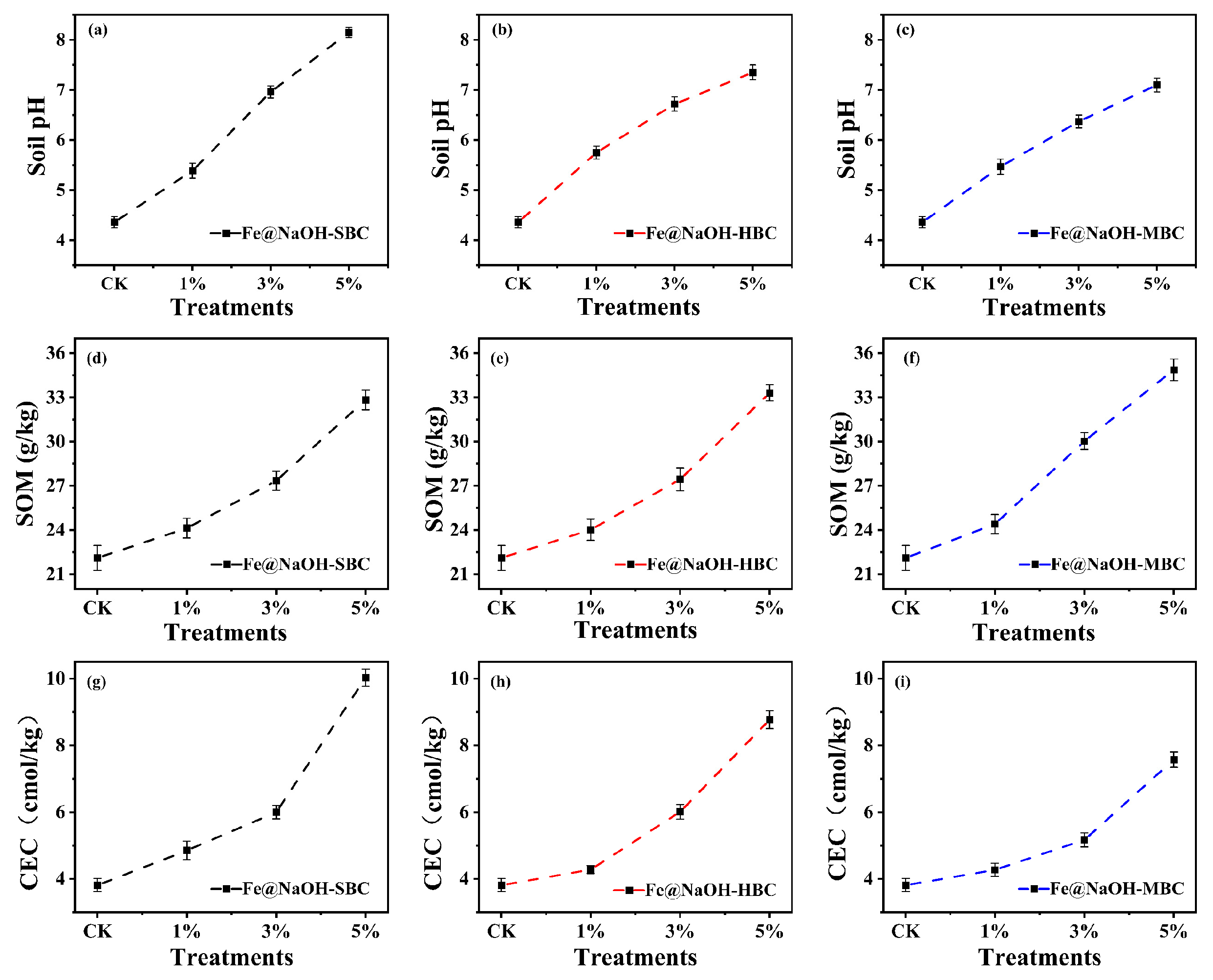

3.3.1. Effects of Alkali–Fe-Modified Biochar Application on Soil pH, SOM, and CEC

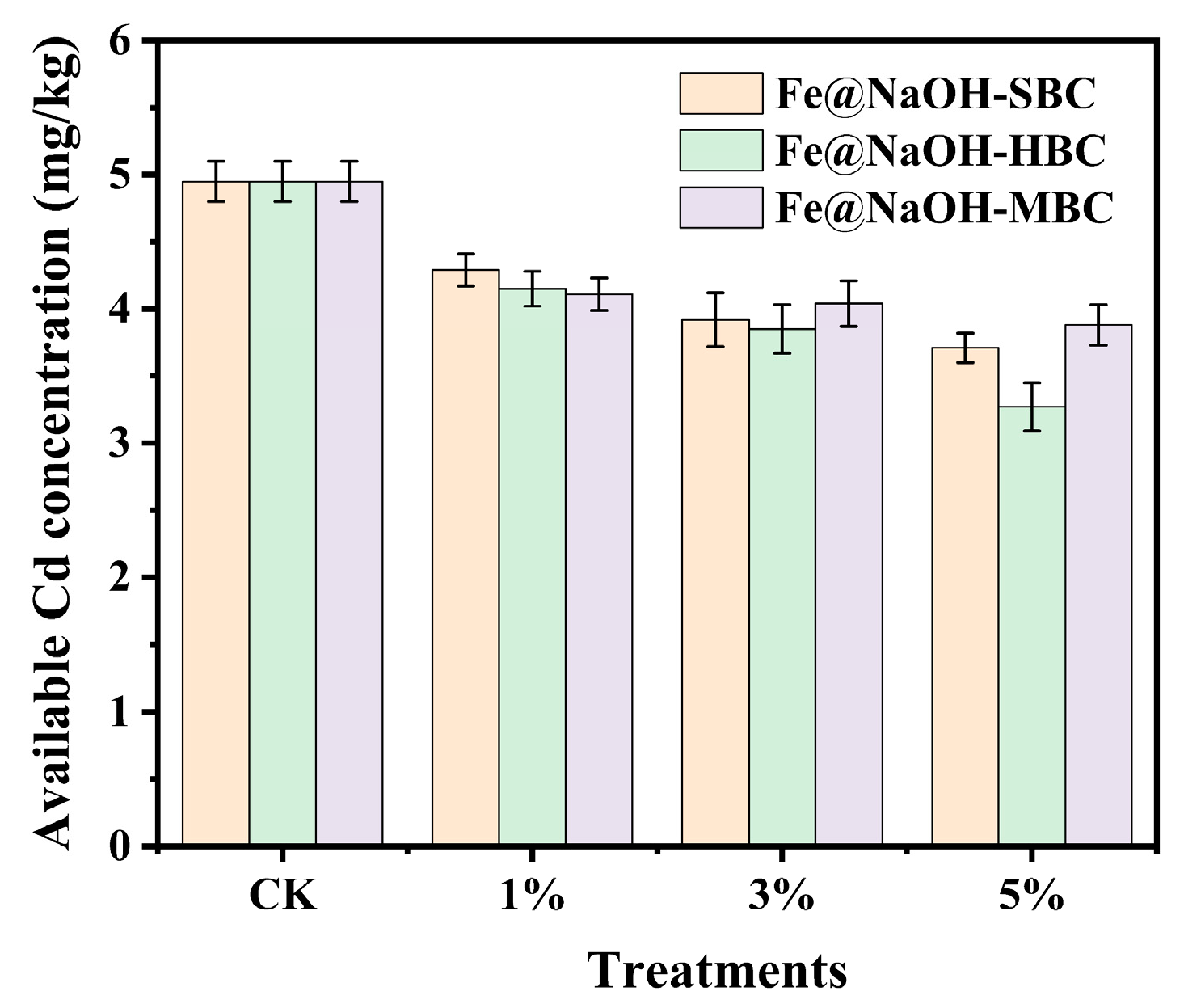

3.3.2. Effect of Applying Alkali–Fe-Modified Biochar on the Bioavailability of Heavy Metals in Soil

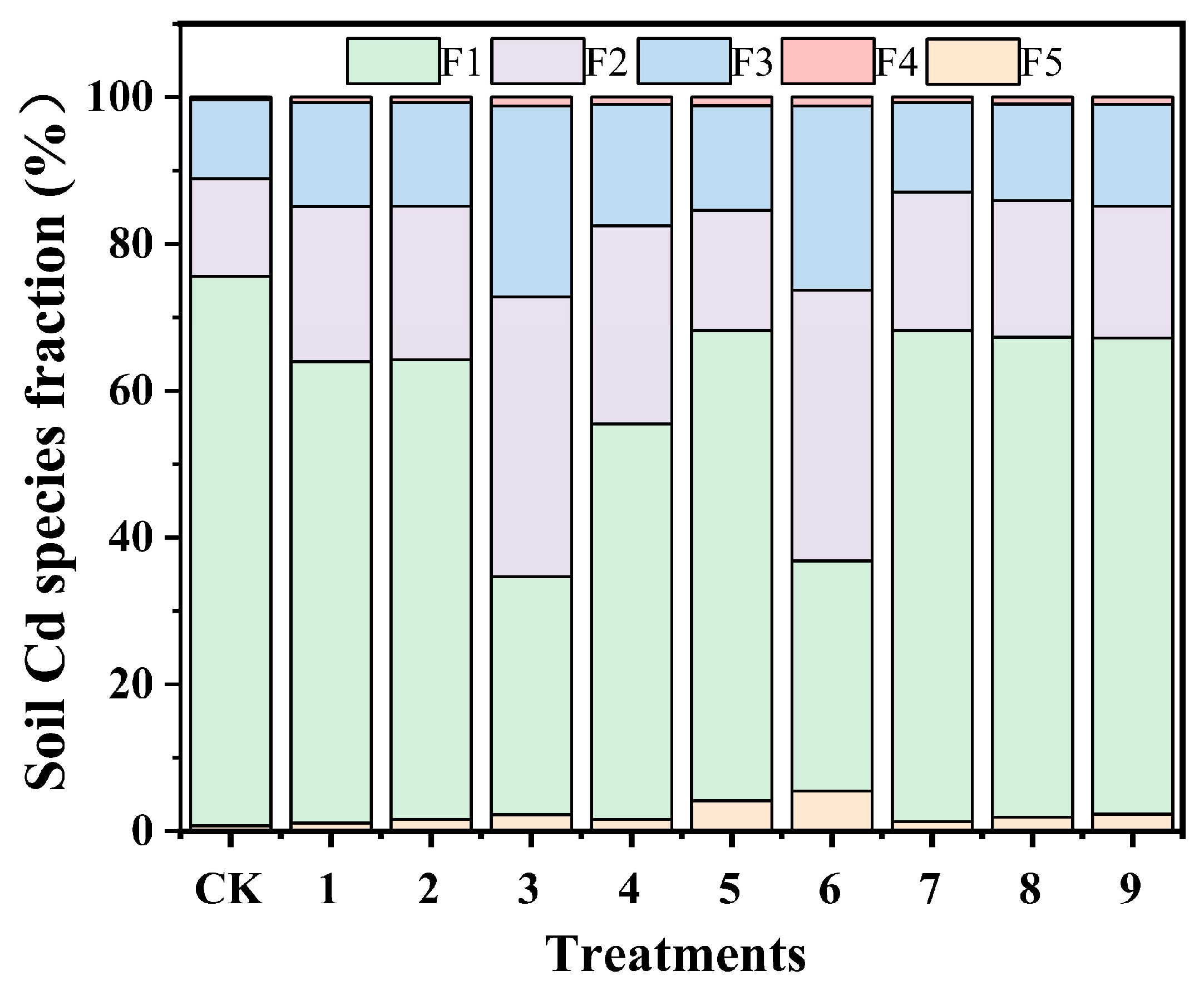

3.3.3. Effects of Alkali–Fe-Modified Biochar on the Distribution of Heavy Metal Speciation in Soil

3.3.4. Effects of Alkali–Fe-Modified Biochar on the Spinach Seed Germination Experiment

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmad, Z.; Gao, B.; Mosa, A.; Yu, Z.; Yin, Y.; Bashir, A.; Ghoveisi, H. Removal of Cu(II), Cd(II) and Pb(II) Ions from Aqueous Solutions by Biochar Derived from Potassium-Rich Biomass. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 180, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, G.; Li, J.; Ji, P.; Liu, Y. Potential of Removing Cd(II) and Pb(II) from Contaminated Water Using a Newly Modified Fly Ash. Chemosphere 2020, 242, 125148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, X.; Lou, Z.; Xiao, R.; Ren, Z.; Lv, X. Source Analysis and Source-Oriented Risk Assessment of Heavy Metal Pollution in Agricultural Soils of Different Cultivated Qualities. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 341, 130942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purkayastha, D.; Mishra, U.; Biswas, S. A Comprehensive Review on Cd(II) Removal from Aqueous Solution. J. Water Process Eng. 2014, 2, 105–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Li, X.; Lin, Z.; Su, X.; Tian, Y. The Removal of Cd by Sulfidated Nanoscale Zero-Valent Iron: The Structural, Chemical Bonding Evolution and the Reaction Kinetics. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 382, 122933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Lin, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Luo, J.; Wu, Y.; Ye, Z.; Huang, Y.; Li, F. Diffusive Gradient in Thin Films Combined with Machine Learning to Discern the Accumulation Characteristics and Driving Factors of Cd and Cu in Soil-Rice Systems. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 495, 138924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Chen, T.; Huang, Q.; Wang, J.; Lu, S.; Yan, J. Enhanced Adsorption for Pb(II) and Cd(II) of Magnetic Rice Husk Biochar by KMnO4 Modification. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 8902–8913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, Y.; Tang, L.; Sohail, M.I.; Cao, X.; Hussain, B.; Aziz, M.Z.; Usman, M.; He, Z.L.; Yang, X. An Explanation of Soil Amendments to Reduce Cadmium Phytoavailability and Transfer to Food Chain. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 660, 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Guo, J.; Huang, X.; Wang, W.; Sun, P.; Li, Y.; Han, J. Functionalized Biochar-Supported Magnetic MnFe2O4 Nanocomposite for the Removal of Pb(II) and Cd(II). RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leng, L.; Xiong, Q.; Yang, L.; Li, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, S.; Li, H.; Huang, H. An Overview on Engineering the Surface Area and Porosity of Biochar. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 763, 144204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.H.; Xie, Y.; Zhou, G.; Liu, J.; Liu, F.; Huang, H. The Effects of Short-Term, Long-Term, and Reapplication of Biochar on the Remediation of Heavy Metal-Contaminated Soil. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 248, 114316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Ou, Z.; Li, W.; Hu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, H.; Wang, J.; Li, Y. Cadmium(II) Adsorption by Recyclable Zeolite-Loaded Hydrogel: Extension to the Removal of Cadmium(II) from Contaminated Soil. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 445, 130532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, Y.J.; Ma, F.; Tankpa, V.; Bai, S.; Guo, X.; Wang, X. Mechanisms and Reutilization of Modified Biochar Used for Removal of Heavy Metals from Wastewater: A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 668, 1298–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, H.; Ma, S.; Xu, S.; Duan, R.; Cheng, G.; Zhao, P. Hierarchically Porous Magnetic Biochar as an Efficient Amendment for Cadmium in Water and Soil: Performance and Mechanism. Chemosphere 2021, 281, 130990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irshad, M.K.; Chen, C.; Noman, A.; Ibrahim, M.; Adeel, M.; Shang, J. Goethite-Modified Biochar Restricts the Mobility and Transfer of Cadmium in Soil-Rice System. Chemosphere 2020, 242, 125152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.Y.; Zhou, H.; Gu, J.F.; Huang, F.; Yang, W.J.; Wang, S.L.; Yuan, T.Y.; Liao, B.H. Effects of Nano-Fe3O4-Modified Biochar on Iron Plaque Formation and Cd Accumulation in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Environ. Pollut. 2020, 260, 113970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Chen, Y.L.; Weng, L.P.; Ma, J.; Khan, Z.H.; Cheng, D.; Li, Y.C. Watering Techniques and Zero-Valent Iron Biochar pH Effects on As and Cd Concentrations in Rice Rhizosphere Soils, Tissues and Yield. J. Environ. Sci. 2021, 100, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, X.M.; Li, C.Y.; Parikh, S.J. Simultaneous Removal of Arsenic, Cadmium, and Lead from Soil by Iron-Modified Magnetic Biochar. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 261, 114157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.S.; Zhao, M.Y.; Zhou, M.; Li, Y.C.; Wang, J.; Gao, B.; Sato, S.; Feng, K.; Yin, W.; Igalavithana, A.D.; et al. Biochar-Supported nZVI (nZVI/BC) for Contaminant Removal from Soil and Water: A Critical Review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 373, 820–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazoui, M.; Elkacmi, R.; Sylla, A.S.; Anter, N.; Dabali, S.; Boudouch, O. Innovative adsorbents and mechanisms for radionuclide removal from aqueous nuclear waste: A comprehensive review of materials, performance, and future perspectives. Total Environ. Eng. 2025, 5, 100042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Dong, X.; Da Silva, E.B.; De Oliveira, L.M.; Chen, Y.; Ma, L.Q. Mechanisms of Metal Sorption by Biochar: Biochar Characteristics and Modifications. Chemosphere 2017, 178, 466–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Kang, Y.; Duan, H.; Zhou, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, Y. Remediation of Cd(II) in Aqueous Systems by Alkali-Modified (Ca) Biochar and Quantitative Analysis of Its Mechanism. Arab. J. Chem. 2022, 15, 103750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; Ngo, H.H.; Guo, W.S.; Nghiem, L.D.; Hai, F.I.; Vigneswaran, S.; Nguyen, T.V. Competitive Adsorption of Metals on Cabbage Waste from Multi-Metal Solutions. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 160, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Cai, C.; Chi, H.; Reid, B.J.; Coulon, F.; Zhang, Y.; Hou, Y. Remediation of Cadmium and Lead Polluted Soil Using Thiol-Modified Biochar. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 388, 122037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HJ/T 166-2004; The Technical Specification for Soil Environmental Monitoring. Ministry of Ecology and Environment: Beijing, China.

- Tessier, A.P.; Campbell, P.G.C.; Bisson, M. Sequential Extraction Procedure for the Speciation of Particulate Trace Metals. Anal. Chem. 1979, 51, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Wabel, M.I.; Al-Omran, A.; El-Naggar, A.H.; Nadeem, M.; Usman, A.R. Pyrolysis temperature induced changes in characteristics and chemical composition of biochar poduced from conocarpus wastes. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 131, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Lee, S.S.; Dou, X.; Mohan, D.; Sung, J.K.; Yang, J.E.; Ok, Y.S. Effects of pyrolysis temperature on soybean stover- and peanut shell-derived biochar properties and TCE adsorption in water. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 118, 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Yu, W.; Liu, S.; Wu, J.; Huang, S.; Yang, J.; Gao, Y. Adsorption of Hexavalent Chromium Using Banana Pseudostem Biochar and Its Mechanism. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Z.; Gao, B.; Mosa, A.; Yu, Z.; Yin, Y.; Bashir, A.; Ghoveisi, H. Adsorption Properties and Mechanism of Suaeda Biochar and Modified Materials for Tetracycline. Environ. Res. 2023, 235, 116549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Li, J.; Wu, D.; Zhang, G.; Sun, Y.; Wang, A.; Sun, K. Construction of the Hierarchical Porous Biochar with an Ultrahigh Specific Surface Area for Application in High-Performance Lithium-Ion Capacitor Cathode. Biochar 2023, 5, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.T.; Nguyen, T.B.; Huang, C.P.; Chen, C.W.; Bui, X.T.; Dong, C.D. Alkaline Modified Biochar Derived from Spent Coffee Ground for Removal of Tetracycline from Aqueous Solutions. J. Water Process Eng. 2021, 40, 101908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, F.; McMillan, O.; Al-Tabbaa, A. Qualitative and Quantitative Characterisation of Adsorption Mechanisms of Lead on Four Biochar. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 609, 1401–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yang, J.; Deng, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, W. αFeOOH@HTC with abundant oxygen vacancy enhances the adsorption of As(III) in different phosphate environments. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 111776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yang, X.; Liu, L.; Ju, M.; Zheng, K. Adsorption Behavior of Selective Recognition Functionalized Biochar to Cd(II) in Wastewater. Materials 2018, 11, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Zhou, D.; Zhu, L. Transitional Adsorption and Partition of Nonpolar and Polar Aromatic Contaminants by Biochar of Pine Needles with Different Pyrolytic Temperatures. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 5137–5143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, I.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Peng, H. Glucose Enhanced the Oxidation Performance of Iron-Manganese Binary Oxides: Structure and Mechanism of Removing Tetracycline. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 573, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Luo, D.; Liu, L.; Huang, X.; Liu, Y.; Wei, L.; Xiao, T.; Wu, Q. Alkali/Fe-Modified Biochar for Cd-As Contamination in Water and Soil: Performance and Mechanism. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2023, 32, 103381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchimiya, M.; Lima, I.M.; Klasson, K.T.; Wartelle, L.H. Textural and Chemical Properties of Swine-Manure-Derived Biochar Pertinent to Its Potential Use as a Soil Amendment. Chemosphere 2012, 89, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.F.; Chen, Z.H.; Yang, F.L.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; He, Y. Adsorption Performance of Tetracycline by Manganese Ferrite-Modified Biochar. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 2023, 42, 1585–1596. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H.; Al-Abed, S.R.; Agarwal, S.; Dionysiou, D.D. Synthesis of Reactive Nano-Fe/Pd Bimetallic System-Impregnated Activated Carbon for the Simultaneous Adsorption and Dechlorination of PCBs. Chem. Mater. 2008, 20, 3649–3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Huang, D.; Liu, X.; Meng, J.; Tang, C.; Xu, J. Remediation of as(iii) and cd(ii) co-contamination and its mechanism in aqueous systems by a novel calcium-based magnetic biochar. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 348, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, M.; Yaqub, M.; Nawaz, H.; Latif, M.; Anjum, M.N.; Nawaz, A.; Shahzad, M.I.; Zia, M.A.; Javaid, A.; Mahmood, K. Influence of Graphene Oxide Contents on Mechanical Behavior of Polyurethane Composites Fabricated with Different Diisocyanates. Polymers 2021, 13, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhongrui, L.; Zhiyong, L. Optimization of Bucky paper-enhanced Multifunctional Thermoplastic Composites. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42423. [Google Scholar]

- Kopcsik, E.; Mucsi, Z.; Schiwert, R.; Vanyorek, L.; Viskolcz, B.; Nagy, M. Aromatic pi-complexation of 1,5-diisocyanonaphthalene with benzene derivatives. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, M.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, H.; Li, L.; Xu, F.; Jiang, H.; Chen, L. Hydroxyapatite modified sludge-based biochar for the adsorption of Cu2+ and Cd2+: Adsorption behavior and mechanisms. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 321, 124413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Kong, L.; Huang, S.; Liu, M.; Li, L. Synthesis of novel magnetic sulfur-doped Fe3O4 nanoparticles for efficient removal of Pb(II). Sci. China 2018, 61, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhou, B.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, W. Fe/S modified sludge-based biochar for tetracycline removal from water. Powder Technol. 2019, 364, 889–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.T.; Zhou, H.; Tang, S.F.; Zeng, P.; Gu, J.F.; Liao, B.H. Enhancing cd(ii)adsorption on rice straw biochar by modification of iron and manganese oxides. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 300, 118899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, Y.; Xu, X.; Xu, Z.; Liang, J.; Yu, Y.; Cao, X. Contribution of different iron species in the iron-biochar composites to sorption and degradation of two dyes with varying properties. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 389, 124471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Ye, C.; Li, F.Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Q. Studies on Adsorption of Nitrate from Modified Hydrophyte Biochar. China Environ. Sci. 2017, 37, 116–122. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, L.; Yu, J.; Pang, Y.; Zeng, G.; Deng, Y.; Wang, J.; Ren, X.; Ye, S.; Peng, B.; Feng, H. Sustainable efficient adsorbent: Alkali-acid modified magnetic biochar derived from sewage sludge for aqueous organic contaminant removal. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 336, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.-W.; Mao, L.; Hu, H.-L.; Gan, W.-J. Effect of Fe-bearing Modifying Agents on Adsorption Performance of Magnetic Straw-Derived Biochars for Cr(VI). Nonferrous Met. (Extr. Metall.) 2022, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Srinivasakannan, C.; Wang, X.; Wang, F.; Liu, X. Synthesis of Activated Carbon Fibers from Cotton by Microwave Induced H3PO4 Activation. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2017, 70, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazetta, A.L.; Pezoti, O.; Bedin, K.C.; Silva, T.L.; Paesano Junior, A.; Asefa, T.; Almeida, V.C. Magnetic Activated Carbon Derived from Biomass Waste by Concurrent Synthesis: Efficient Adsorbent for Toxic Dyes. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 1058–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, L.; Singh, J.S. Synthesis of Novel Biochar from Waste Plant Litter Biomass for the Removal of Arsenic (III and V) from Aqueous Solution: A Mechanism Characterization, Kinetics and Thermodynamics. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 248, 109235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaskin, J.W.; Steiner, C.; Harris, K.; Das, K.C.; Bibens, B. Effect of Low-Temperature Pyrolysis Conditions on Biochar for Agricultural Use. Trans. ASABE 2008, 51, 2061–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhou, C.; Zeng, H.; Wu, H.; Yang, L.; Deng, L.; Shi, Z. ZIF-8 assisted synthesis of magnetic core-shell Fe3O4@CuS nanoparticles for efficient sulfadiazine degradation via H2O2 activation: Performance and mechanism. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 594, 502–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Zhang, S.; Li, H.; Li, S.; Cheng, K.; Li, J.S.; Tsang, D.C. Com straw-derived biochar impregnated with α-FeOOH nanorods for highly effective copper removal. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 348, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Cao, X.; Ouyang, X.; Sohi, S.P.; Chen, J. Adsorption Kinetics of Magnetic Biochar Derived from Peanut Hull on Removal of Cr(VI) from Aqueous Solution: Effects of Production Conditions and Particle Size. Chemosphere 2016, 145, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Gao, M.; Deng, Y.; Khan, Z.H.; Liu, X.; Song, Z.; Qiu, W. Efficient Oxidation and Adsorption of As(II)and As(V) in Water Using a Fenton-like Reagent, (Ferrihydrite)-Loaded Biochar. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 715, 136957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I.; Nadeem, I.; Majid, A.; Shakil, M. Adsorption Mechanism of Palbociclib Anticancer Drug on Two Different Functionalized Nanotubes as a Drug Delivery Vehicle: A First Principle’s Study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 546, 149129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Zhang, W.; Hu, X.; He, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; Hu, G.; Li, Y.; Deng, X. Selective Adsorption Behavior and Mechanism for Cd(II) in Aqueous Solution with a Recoverable Magnetie-Surface Ion-Imprinted Polymer. Polymers 2023, 15, 2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- OuldM’hamed, M.; Khezami, L.; Alshammari, A.G.; Ould-Mame, S.M.; Ghiloufi, I.; Lemine, O.M. Removal of cadmium(II) ions from aqueous solution using Ni (15 wt.%)-doped α-Fe2O3 nanocrystals: Equilibrium, thermodynamic, and kinetic studies. Water Sci. Technol. J. Int. Assoc. Water Pollut. Res. 2015, 72, 608–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Xu, Y.; Huang, Q.; Sun, Y.; Liang, X.; Wang, L.; Qin, X.; Zhao, L. Adsorption characteristics and the removal mechanism of two novel Fe-Zn composite modified biochar for Cd(II) in water. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 333, 125078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ocon, J.D.; Tuan, T.N.; Yi, Y.; de Leon, R.L.; Lee, J.K.; Lee, J. Ultrafast and stable hydrogen generation from sodium borohydride in methanol and water over Fe–B nanoparticles. J. Power Sources 2013, 243, 444–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Guo, H.; Dai, P.; Zhang, J.; Wang, D.; Faheem, M.; Liu, Z.; Tao, M. Vinasse-derived magnetic porous Fe-biochar for synergistic adsorption and non-radical oxidation of bisphenol A: Mechanisms and applications. Environ. Res. 2026, 289, 123395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, F.; Chen, C.; Chen, X.M.; Liu, W.; Wen, X.; Hu, S.; Chen, Y. Effects of Wheat Straw Derived Biochar on Cadmium Availability in a Paddy Soil and Its Accumulation in Rice. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 257, 113592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Guo, D.; Mahar, A.; Wang, P.; Ma, F.; Shen, F.; Li, R.; Zhang, Z. Phytoextraction of Toxic Trace Elements by Sorghum bicolor Inoculated with Streptomyces pactum (Act12) in Contaminated Soils. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2017, 139, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, X.; Wu, Z.; Yu, J.; Cravotto, G.; Liu, X.; Li, Q.; Wang, J. Copyrolysis of Biomass, Bentonite, and Nutrients as a New Strategy for the Synthesis of Improved Biochar-Based Slow-Release Fertilizers. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 3181–3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.Z.; Li, X.W.; Gao, M.L.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, S.; Xie, Y.; Wang, Y. Effect of Fe–Mn–Ce Modified Biochar Composite on Microbial Diversity and Properties of Arsenic-Contaminated Paddy Soils. Chemosphere 2020, 250, 126249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Deng, R.; Wan, J.; Zeng, G.; Xue, W.; Wen, X.; Zhou, C.; Hu, L.; Liu, X.; Xu, P.; et al. Remediation of lead-contaminated sediment by biochar-supported nano-chlorapatite: Accompanied with the change of available phosphorus and organic matters. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 348, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdin, Y.; Usman, A.; Ok, Y.S.; Tsang, Y.F.; Al-Wabel, M. Competitive sorption and availability of coexisting heavy metals in mining-contaminated soil: Contrasting effects of mesquite and fishbone biochars. Environ. Res. 2020, 181, 108846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattnaik, B.K.; Behera, R.; Santra, S.C.; Choudhury, S.; Biswas, J.K.; Hossain, A.; Moulick, D. Potentials of Urban Waste Derived Biochar in Minimizing Heavy Metal Bioavailability: A Techno-Economic Review. iScience 2025, 28, 111915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, H.; Fang, Z.; Tsang, P.E.; Zheng, L.; Cheng, W.; Fang, J.; Zhao, D. Remediation of Hexavalent Chromium Contaminated Soil by Biochar-Supported Zero-Valent Iron Nanoparticles. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016, 318, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhong, B.; Shafi, M.; Ma, J.; Guo, J.; Wu, J.; Ye, Z.; Liu, D.; Jin, H. Effects of Biochar on Growth and Heavy Metals Accumulation of Moso Bamboo (Phyllostachys pubescens), Soil Physical Properties, and Heavy Metals Solubility in Soil. Chemosphere 2019, 219, 510–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morera, M.T.; Echeverría, J.C.; Mazkiarán, C.; Garrido, J.J. Isotherms and Sequential Extraction Procedures for Evaluating Sorption and Distribution of Heavy Metals in Soils. Environ. Pollut. 2001, 113, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Q.; Wu, J.; Wang, L.; Yang, G.; Zhang, X. Effect of Biochar on Heavy Metal Speciation of Paddy Soil. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2015, 226, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, S.; Shaaban, M.; Hussain, Q.; Iqbal, J.; Khan, K.S.; Husain, A.; Ahmed, N.; Mehmood, S.; Hu, H. Influence of Organic and Inorganic Passivators on Cd and Pb Stabilization and Microbial Biomass in a Contaminated Paddy Soil. J. Soils Sediments 2018, 18, 2948–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadi, L.N.; Tamadoni, A.; Siebecker, M.G.; Sricharoenvech, P.; Barreto, M.S.C.; Fischel, M.H.H.; Tappero, R.; Sparks, D.L. Hurricanes and turbulent floods threaten arsenic-contaminated coastal soils and vulnerable communities. Environ. Int. 2025, 200, 109479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, T.; Chen, X.; Yuan, R.; Pan, S.; Wang, Y.; Bian, R.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Joseph, S.; Li, L.; et al. Iron-modified biochars and their aging reduce soil cadmium mobility and inhibit rice cadmium uptake by promoting soil iron redox cycling. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ning, J.; Li, Q.; Li, L.; Bolan, N.S.; Singh, B.P.; Wang, H. Effects of iron and nitrogen-coupled cycles on cadmium availability in acidic paddy soil from Southern China. J. Soils Sediments 2023, 23, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchimiya, M.; Lima, I.M.; Klasson, K.T.; Chang, S.; Wartelle, L.H.; Rodgers, J.E. Contaminant Immobilization and Nutrient Release by Biochar Soil Amendment: Roles of Natural Organic Matter. Chemosphere 2010, 80, 935–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Biochar | N (%) | C (%) | H (%) | O (%) | H/C | O/C | (O + N)/C | Ash Content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBC | 2.304 | 52.493 | 3.814 | 20.939 | 0.865 | 0.299 | 0.337 | 26 |

| HBC | 1.517 | 62.802 | 4.022 | 22.510 | 0.763 | 0.269 | 0.290 | 10 |

| MBC | 1.120 | 68.264 | 4.086 | 21.921 | 0.713 | 0.241 | 0.255 | 7 |

| Biochar | BET Specific Area (m2/g) | Total Pore Volume (Adsorption) (cm3/g) 10−2 | BET Average Pore Size (Adsorption) (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SBC | 3.707 | 1.03 | 11.152 |

| Fe@NaOH-SBC | 67.096 | 5.22 | 3.115 |

| HBC | 2.703 | 0.56 | 8.274 |

| Fe@NaOH-HBC | 45.229 | 8.17 | 7.217 |

| MBC | 3.559 | 0.83 | 9.319 |

| Fe@NaOH-MBC | 67.369 | 5.57 | 3.307 |

| Model | Parameter | SBC | NaOH-SBC | Fe@NaOH-SBC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudo-first-order | qe,exp (mg/g) | 43.8 | 98.8 | 145.0 |

| qe,cal (mg/g) | 40.515 | 91.507 | 138.576 | |

| K1 (1/min) | 0.040 | 0.070 | 0.128 | |

| R2 | 0.9709 | 0.9521 | 0.9642 | |

| Pseudo-second-order | qe,cal (mg/g) | 43.004 | 96.661 | 143.880 |

| K2 (g/mg·min) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | |

| R2 | 0.9901 | 0.9863 | 0.9914 |

| Model | Parameter | HBC | NaOH-HBC | Fe@NaOH-HBC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudo-first-order | qe,exp (mg/g) | 13.4 | 78.3 | 120 |

| qe,cal (mg/g) | 12.504 | 72.364 | 116.243 | |

| K1 (1/min) | 0.161 | 0.853 | 0.121 | |

| R2 | 0.9333 | 0.9674 | 0.9827 | |

| Pseudo-second-order | qe,cal (mg/g) | 12.946 | 77.089 | 121.821 |

| K2 (g/mg·min) | 0.022 | 0.002 | 0.002 | |

| R2 | 0.9760 | 0.9903 | 0.9973 |

| Model | Parameter | MBC | NaOH-MBC | Fe@NaOH-MBC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudo-first-order | qe,exp (mg/g) | 14.7 | 87.1 | 124.0 |

| qe,cal (mg/g) | 13.532 | 81.747 | 118.603 | |

| K1 (1/min) | 0.157 | 0.076 | 0.116 | |

| R2 | 0.9203 | 0.9737 | 0.9718 | |

| Pseudo-second-order | qe,cal (mg/g) | 14.047 | 87.040 | 124.787 |

| K2 (g/mg·min) | 0.019 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| R2 | 0.9691 | 0.9937 | 0.9959 |

| Model | Parameter | SBC | NaOH-SBC | Fe@NaOH-SBC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Langmuir | qmax (mg/g) | 48.05 | 88.46 | 133.91 |

| KL (L/mg) | 0.107 | 0.131 | 0.116 | |

| R2 | 0.996 | 0.988 | 0.986 | |

| Freundlich | KF (L/mg) | 11.449 | 20.774 | 38.630 |

| 1/n | 0.264 | 0.274 | 0.250 | |

| R2 | 0.884 | 0.887 | 0.817 |

| Model | Parameter | HBC | NaOH-HBC | Fe@NaOH-HBC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Langmuir | qmax (mg/g) | 12.77 | 75.67 | 115.97 |

| KL (L/mg) | 0.306 | 0.061 | 0.208 | |

| R2 | 0.986 | 0.993 | 0.996 | |

| Freundlich | KF (L/mg) | 4.223 | 15.450 | 32.405 |

| 1/n | 0.212 | 0.287 | 0.250 | |

| R2 | 0.924 | 0.928 | 0.903 |

| Model | Parameter | MBC | NaOH-MBC | Fe@NaOH-MBC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Langmuir | qmax (mg/g) | 14.44 | 84.66 | 123.85 |

| KL (L/mg) | 0.145 | 0.084 | 0.158 | |

| R2 | 0.981 | 0.990 | 0.990 | |

| Freundlich | KF (L/mg) | 4.147 | 17.631 | 30.487 |

| 1/n | 0.232 | 0.290 | 0.272 | |

| R2 | 0.940 | 0.900 | 0.889 |

| T | Parameter | Fe-SBC | Fe-HBC | Fe-MBC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 298 | ln K (L/mol) | 0.944 | 0.405 | 0.708 |

| ΔG° (kJ/mol) | −2.34 | −1.005 | −1.755 | |

| 308 | ln K (L/mol) | 1.516 | 0.731 | 1.153 |

| ΔG° (kJ/mol) | −3.883 | −1.872 | −2.952 | |

| 318 | ln K (L/mol) | 2.143 | 0.969 | 1.386 |

| ΔG° (kJ/mol) | −5.665 | −2.563 | −3.665 | |

| 298–318 | ΔS° (kJ·(mol/K)) | 0.166 | 0.078 | 0.096 |

| ΔH° (kJ/mol) | 47.193 | 22.248 | 26.790 | |

| R2 | 0.998 | 0.995 | 0.975 |

| Treatments | Germination Time | Emergence Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Healthy soil | Day 5 | 90% |

| Cd-contaminated soil | Day 9 | 40% |

| Fe@NaOH-SBC 1% | Day 9 | 45% |

| Fe@NaOH-SBC 3% | Day 5 | 80% |

| Fe@NaOH-SBC 5% | Day 10 | 50% |

| Fe@NaOH-HBC 1% | Day 8 | 45% |

| Fe@NaOH-HBC 3% | Day 6 | 75% |

| Fe@NaOH-HBC 5% | Day 7 | 60% |

| Fe@NaOH-MBC 1% | Day 9 | 45% |

| Fe@NaOH-MBC 3% | Day 6 | 75% |

| Fe@NaOH-MBC 5% | Day 7 | 55% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, X.; Shan, D.; Xie, Y.; Li, J.; Ning, J.; Yi, G.; Chen, H.; Xiang, T. Preparation of Alkali–Fe-Modified Biochar from Agricultural Waste for Remediation of Cadmium-Contaminated Soil and Water. Sustainability 2026, 18, 373. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010373

Zhang X, Shan D, Xie Y, Li J, Ning J, Yi G, Chen H, Xiang T. Preparation of Alkali–Fe-Modified Biochar from Agricultural Waste for Remediation of Cadmium-Contaminated Soil and Water. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):373. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010373

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Xinyue, Dexin Shan, Yufu Xie, Jun Li, Jingyuan Ning, Guangli Yi, Huimin Chen, and Tingfen Xiang. 2026. "Preparation of Alkali–Fe-Modified Biochar from Agricultural Waste for Remediation of Cadmium-Contaminated Soil and Water" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 373. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010373

APA StyleZhang, X., Shan, D., Xie, Y., Li, J., Ning, J., Yi, G., Chen, H., & Xiang, T. (2026). Preparation of Alkali–Fe-Modified Biochar from Agricultural Waste for Remediation of Cadmium-Contaminated Soil and Water. Sustainability, 18(1), 373. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010373