1. Introduction

Global climate change remains one of the most pressing challenges confronting humanity, with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) warning that global temperatures have already risen by 1.2 °C since the Industrial Revolution, edging closer to the Paris Agreement’s 1.5 °C threshold. Against this backdrop, the 28th (COP28) and 29th (COP29) United Nations Climate Change Conferences emerged as pivotal milestones in accelerating global climate action. For the first time in nearly three decades of climate summits, the final agreement of COP28 explicitly called for a “just, orderly, and equitable transition away from fossil fuels” to align with the 1.5 °C goal of the Paris Agreement [

1]. This breakthrough, encapsulated in the UAE Consensus, recognized the urgent need to phase out coal, oil, and gas while accelerating the deployment of renewable energy. A key achievement was the commitment to triple global renewable energy capacity and double energy efficiency by 2030, supported by 130 nations [

2]. This ambitious target aims to drive a rapid shift toward clean energy systems, reducing reliance on fossil fuels and curbing greenhouse gas emissions. Next year, COP29 held in Azerbaijan in 2024 secured a historic consensus on post-2025 climate financing, establishing the Baku Climate Unity Pact to address the urgent funding gap for developing nations [

3]. Under this framework, developed countries committed to mobilizing at least

$300 billion annually by 2035 to support climate action in vulnerable regions. Additionally, a broader goal of

$1.3 trillion per year in total climate finance (public and private) by 2035 was set to scale renewable energy deployment, adaptation projects, and loss-and-damage initiatives. While these targets fall short of the

$4 trillion annual funding needed to limit warming to 1.5 °C, they represent the first concrete step toward aligning financial flows with climate science.

Renewable energy deployment has emerged as a cornerstone of climate mitigation strategies. According to the International Renewable Energy Agency, global renewable energy installed capacity surged by a record-breaking 530 gigawatts (GW) in 2024 [

4]. This growth propelled total green energy generation capacity to approximately 4400 GW, marking a significant increase from the 2023 figure of 3870 GW. Among the renewable energies, solar photovoltaics (PV) has become the most important one for supporting the energy transition. Thanks to the supportive policies, the cost of electricity from solar PV has decreased significantly in recent decades and global capacity has tripled from 2018 to 2023 [

5]. Between 2024 and 2030, solar PV is projected to account for 80% of the growth in global renewable energy capacity [

6]. This will be driven by the development of new large-scale solar power plants and a rise in rooftop solar installations by businesses and homeowners. By the end of this decade, solar PV is expected to become the dominant renewable energy source, surpassing both wind and hydropower.

China is poised to solidify its role as the global leader in renewable energy, with projections indicating that it will account for 60% of the global expansion in renewable capacity through 2030 [

6]. By this time, China is expected to contribute to the installation of every second megawatt of renewable energy capacity worldwide. This milestone comes after the country surpassed its 1200 GW target for solar PV and wind energy six years ahead of schedule. Since the cessation of feed-in tariffs in 2020, China’s cumulative solar PV capacity has nearly quadrupled, while its wind capacity has doubled. These advancements have been largely driven by cost competitiveness and robust policy support from both central and local governments in promoting large-scale and distributed solar PV solutions across all renewable technologies.

In the context of accelerating global energy transition within the lead by China, local government policies play a pivotal role in shaping renewable energy development landscapes. However, existing literature has primarily focused on national-level policy frameworks and large-scale utility projects, leaving a significant research gap in understanding the micro-processes of solar PV policy formulation and project management at the county level. Specifically, there is a lack of empirical studies analyzing how county-level governments design PV policies, implement regulatory mechanisms, and address challenges during project development. This gap is particularly critical given the increasing decentralization of energy governance, where county-level decisions directly influence market dynamics and community engagement.

Against this backdrop, this study aims to address three key research questions: (1) How do county-level governments design PV policies, and what factors influence their policy-making processes? (2) What regulatory mechanisms do county-level governments employ to implement PV policies, and how effective are these mechanisms in practice? (3) What challenges do county-level governments face during PV project development, and how do they respond to and overcome these challenges? By examining the policy process and project management practices in Lin’an District, Hangzhou, this research contributes to filling the identified gap by providing a nuanced understanding of county-level governance in renewable energy transitions, which can offer replicable insights for other regions navigating similar policy landscapes.

The contributions of this study are threefold. Theoretically, it deepens the understanding of local governance in authoritarian regimes by demonstrating how adaptive governance mechanisms—such as multi-stakeholder consultations, flexible policy design, and iterative adjustments—can operate within centralized political structures. Empirically, it provides one of the first detailed accounts of county-level PV policy formulation and implementation in China, based on comprehensive policy analysis and field interviews. Practically, it offers a replicable policy mix for promoting PV deployment—combining rooftop, industrial/commercial, and agrivoltaic models—that can inform both other regions in China and developing countries facing similar governance and market conditions.

This paper systematically examines the policy-making processes and governance mechanisms of China’s local governments in advancing renewable energy initiatives, structured as follows:

Section 1 introduces the global climate crisis and China’s renewable energy development, contextualizing the role of local innovation in achieving national renewable energy targets.

Section 2 conducts a literature review, synthesizing theoretical frameworks—including top-down governance, bottom-up implementation, participatory governance, and experimentation in hierarchy—to analyze authoritarian policy-making dynamics.

Section 3 outlines the mixed-methods approach, detailing case study design, data sources and policy analysis.

Section 4 begins with a review of key PV policies introduced during the 14th Five-Year Plan period, followed by a categorized summary and an analysis of policies across different administrative levels.

Section 5 examines the three phases of PV policy implementation in Lin’an, highlighting specific innovative practices.

Section 6 discusses the distinctive features of policy formulation and implementation in Lin’an, while also identifying existing challenges. Finally,

Section 7 concludes the study and calls for further research on authoritarian policy learning mechanisms. This structure ensures a rigorous progression from theoretical foundation to practical application, offering insights into China’s energy transition policies.

2. Literature Review

The governance of new energy policy, including renewable energy such as solar, wind, and bioenergy, has become a significant topic within academic and policy discussions worldwide. New energy policy operates in a complex landscape, influenced by various stakeholders at different levels of governance. Energy transition and climate change mitigation achievement can no longer be seen only through top-down activities from a national government. Local and regional governments have a crucial role in delivering public policies relevant to such endeavor [

7]. Therefore, the implementation of multilevel governance (MLG) has become a priority for fostering local and regional development more inclusively [

8].

In recent years, the concept of adaptive governance has emerged as a critical lens for understanding energy transitions. Adaptive governance emphasizes flexibility, iterative learning, and collaboration among diverse actors to navigate complex socio-ecological systems [

9,

10,

11]. Scholars argue that adaptive governance is particularly relevant for renewable energy systems, where rapid technological changes, market uncertainties, and ecological constraints demand continuous adjustment rather than rigid planning. Key elements include polycentric decision-making, stakeholder participation, feedback mechanisms, and the ability to revise policies in response to new knowledge or unexpected outcomes. Applied to the energy sector, adaptive governance has been proposed as a way to enhance resilience, legitimacy, and effectiveness in transitions [

12]. In authoritarian contexts such as China, adaptive governance takes on distinct forms: while ultimate authority remains centralized, local governments may engage in experimentation, stakeholder consultation, and pragmatic problem-solving to address implementation challenges. This hybrid practice allows local authorities to align with national targets while retaining flexibility to respond to local conditions.

A number of research have highlighted that China’s political system is not strictly top-down but de-centralized to some extent [

13,

14]. Given the country’s vast territory and diverse regional resources and conditions, uniform policies are often infeasible, thus granting local governments flexibility to adapt policies or adjust decision-making processes. This multi-level governance framework operates through the interactive dynamics of both top-down directives and bottom-up initiatives, enabling adaptive policy implementation that balances central mandates with local contextual needs. For example, China’s national low-carbon policy, though perceived as authoritarian, shows a mixed authoritarian-liberal dynamic in practice. While its top-down approach has driven the low-carbon transition, central government’s inability to fully control local actors has enabled de facto neoliberal environmentalism: local governments and energy firms operate with significant autonomy in managing energy use, despite overarching authoritarian rule [

15]. Despite the strong central government, the role of local authorities in mediating between top-down energy strategies and bottom-up developmental needs is equally crucial [

16]. In fact, Chinese higher authorities often strategically issue ambiguous directives and withhold details about policy goals from subordinates [

17]. This ambiguity plays a dual role as both a constraint and a facilitator of policy implementation, highlighting its dynamic and evolving function in balancing central control with local autonomy [

18]. Additionally, local governments engage in the selective implementation of environmental policies, as their focus is directed toward the central government’s stance on specific policies [

19]. This orientation arises because the design of the central reward/penalty system signals the relative priority of different policies, shaping local enforcement priorities.

In the context of Chinese politics, the concept of “fragmented authoritarianism” highlights the idea that, although the central government retains ultimate authority in determining policy direction, the implementation of policies is frequently influenced by intricate interactions among a range of bureaucratic actors. These include central ministries, local governments, and other institutional stakeholders, each of which plays a significant role in shaping the policy process [

20]. These actors frequently pursue their own interests, leading to bargaining, negotiation, and coordination challenges [

21]. As a result, policy outcomes tend to be inconsistent and adaptive rather than uniformly top-down while policy coordination among the different stakeholders is needed to improve [

22,

23]. The theory of fragmented authoritarianism thus provides a nuanced lens through which to understand the dynamic interplay between central authority and bureaucratic decentralization in China’s governance, revealing how informal practices and institutional fragmentation mediate state power. Mertha further found that the process itself has become increasingly pluralized: barriers to participation have diminished, particularly for certain actors—including previously marginalized officials, nongovernmental organizations, and social media [

24].

Scholars have also identified a model of policy-making in the Chinese government termed “experiment in hierarchy”, which is the China’s use of “pilot projects” (试点) [

25]. Central authorities, such as the State Council, grant selected administrative units’ temporary autonomy to test innovative policies—ranging from carbon trading mechanisms to rural land reforms or tech-enabled governance tools—within the overarching hierarchical framework [

26]. These experiments follow a structured cycle: central agencies first define broad objectives and select pilot regions, followed by subordinate governments tailoring specific measures using local knowledge to address regional disparities. A feedback loop ensures results are evaluated by higher authorities, with successful models scaled nationally and failed initiatives contained to mitigate systemic risks. This approach embodies a strategy of iterative learning, balancing national unity with adaptive flexibility. Such practices exemplify “strategic decentralization,” enhancing governance resilience in a large, diverse nation by allowing policies to evolve through localized experimentation rather than rigid, uniform edicts. This framework highlights how hierarchical systems can leverage controlled innovation to navigate complex challenges, demonstrating the reciprocal relationship between centralized coordination and decentralized adaptation in institutional learning [

27].

Since Xi Jinping became China’s paramount leader, observers have highlighted significant shifts in the Chinese political system: reconfigured central-local relations, tighter top-down governance, Xi’s consolidation as the “core leader,” a sweeping anti-corruption campaign, intensified ideological propaganda, stricter censorship, and grid-based community control [

28,

29,

30]. These changes evoke traditional governing traits once thought eclipsed during the reform era [

31]. Evidence also shows that the central government has re-centralized policymaking and enforcement powers over environmental governance by strengthening control through mechanisms such as the Central Environmental Inspection Team, which includes a rigorous inspection system and frequent inquiry meetings with local government leaders to realign central–local power relations in environmental enforcement [

32,

33].

To summarize, scholars have conducted extensive research on China’s political system, policymaking, and implementation processes, yet significant debates remain. While some scholars argue that China’s governance is undergoing a process of decentralization, others contend that central authority has been increasingly consolidated in recent years. Against this backdrop, China’s announcement of its dual carbon goals—peaking carbon emissions before 2030 and achieving carbon neutrality before 2060—has added new complexity to the debate. The adaptive governance perspective helps situate this debate: it suggests that despite authoritarian centralization, local governments retain spaces for flexible problem-solving, iterative adjustment, and stakeholder coordination. This allows for an energy governance model that is neither fully top-down nor bottom-up, but instead adaptive within hierarchical constraints. In particular, the central government’s emphasis on the development of renewable energy as a critical pathway to achieving dual carbon goals highlights both the role of top-level policy design and the challenges of multi-level implementation within a fragmented authoritarian system. The key questions, therefore, are: To what extent do local governments retain latitude in formulating renewable energy policies? What distinctive features characterize their adaptive practices? And has there been a trend toward greater centralization or continued adaptive experimentation in recent years?

3. Research Methodology and Data

This study employs a mixed-methods approach, combining policy document analysis and semi-structured interviews to examine the dynamics of local renewable energy policymaking in China. Policy analysis focuses on multi-level governance frameworks, including national guidelines, provincial regulations, municipal directives, and county-level implementation schemes. Policy documents were collected from official government websites, policy databases, and local archives, following three inclusion criteria:

Timeframe—issued between January 2021 and March 2025, corresponding to the 14th Five-Year Plan period.

Document type—strategic plans, implementation opinions, regulations, and technical guidelines related to PV policy.

Relevance—directly addressing PV development, renewable energy deployment, or associated governance mechanisms at national, provincial, municipal, or county level.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 30 key stakeholders between April 2023 and March 2025. These interviews were not a standardized questionnaire survey; rather, they were designed as semi-structured conversations to elicit process-focused accounts of how PV policies were interpreted, coordinated, and implemented in practice in Lin’an District. Interviewees included district-level officials (e.g., relevant bureaus engaged in PV planning and permitting), grid company personnel, PV project developers and investors, project/site managers, industry association representatives, and academic or professional experts with direct knowledge of local PV governance. An anonymized overview of respondent categories, organizational type (e.g., government or grid), role/position level, and interview timing is provided in

Appendix A Table A1.

The interview guide covered eight core themes: (1) policy goals and the main drivers behind PV promotion; (2) how responsibilities were allocated across bureaus and actors; (3) approval procedures and cross-departmental coordination; (4) grid connection requirements, constraints, and risk management; (5) market arrangements and delivery models (e.g., rooftop deployment, industrial/commercial PV, agrivoltaics where applicable); (6) information disclosure, engagement with communities/households, and routine dispute handling; (7) perceived outcomes and how costs and benefits were distributed among households, firms, and public agencies; and (8) implementation bottlenecks, unintended consequences, and subsequent adjustments. Example questions included: “Which agencies are involved at each step of project screening and approval at the district level?”, “What are the most common technical or administrative barriers to grid connection, and how are they resolved?”, and “How are household or community concerns addressed during implementation, and what changes have been made based on feedback?”

Interviewees were recruited using purposive sampling to ensure coverage of the main actor groups involved in Lin’an’s PV governance, followed by snowball referrals to identify additional informants with direct operational knowledge. Inclusion focused on respondents who had participated in PV policy formulation, permitting/coordination, grid connection, project development, construction, or operation and maintenance during the study period, and who could provide concrete descriptions of procedures, decisions, and cases. Because the goal was analytical coverage of key institutions and processes rather than statistical representativeness, we sought diversity across administrative and market-facing roles and mitigated potential selection bias by cross-checking accounts across actor groups and triangulating interview insights with policy documents and official statistics.

All interviews were conducted with informed consent. With permission, interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and anonymized by removing personal identifiers and using respondent codes in notes and analysis. In addition, quantitative indicators (e.g., installed capacity growth and official estimates related to emission reduction) from Lin’an government statistics were used for contextual triangulation rather than for statistical modelling, helping to validate and situate qualitative findings.

Qualitative analysis followed a thematic coding procedure supported by NVivo 12. First-level codes were generated inductively from the transcripts to capture broad themes (e.g., “policy drivers,” “governance mechanisms,” “market dynamics”). These were then refined into second-level codes that corresponded to more specific mechanisms observed in the case (e.g., under “governance mechanisms”: “PV task force coordination,” “expert database,” “dual acceptance system”). Coding was guided by an iteratively refined codebook, and interpretive consistency was strengthened through repeated comparison across transcripts and continuous cross-checking against policy texts. Representative anonymized quotations are used in the results section to illustrate core claims and improve transparency.

4. Policy Analysis

4.1. From Central-Level to City-Level-Upper-Level Energy Policymaking

China’s PV policymaking and implementation take place within a tiered administrative system. At the top, national authorities set overarching energy and climate objectives and issue sectoral guidance; provincial governments translate these priorities into regional plans and targets; and prefecture-level cities coordinate cross-departmental action. Much of the practical work, however—project screening, permitting, inter-agency coordination, and engagement with firms and communities—happens at the county level, including both counties and urban districts. Lin’an is an urban district under Hangzhou City in Zhejiang Province, and therefore sits at this county level in the governance chain. Below the district, township/street administrations and village/community organizations often support outreach and local coordination, while grid companies and developers shape what can be delivered through connection requirements, construction capacity, and technical standards.

We have summarized the most important solar PV-related policies issued by governments at different levels during the 14th Five-Year Plan period (2021–2025), as presented in

Appendix A Table A2. China’s renewable energy policies operate within a structured administrative framework that integrates central strategic planning with localized implementation, ensuring alignment between national goals—such as carbon peak by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060—and regional realities. At the central level, the process is led by key institutions like the State Council, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), and the National Energy Administration (NEA), alongside ministries such as Finance and Science and Technology. The State Council sets top-level objectives, such as embedding new energy development in the “14th Five-Year Plan” and defining renewable energy targets [

34]. The NDRC, as the macroeconomic planner, integrates new energy strategies into national economic blueprints, balancing energy security, industrial growth, and decarbonization.

Subordinate to the NDRC, the NEA specializes in granular energy sector management: drafting detailed plans for solar, wind, hydro, and nuclear energy; setting technical standards; approving major projects (e.g., large-scale solar power plants). Other central agencies play supporting roles: the Ministry of Finance administers subsidies for renewable energy projects, while the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology regulates manufacturing standards for renewable energy systems.

At the local level, provinces, municipalities, and counties adapt central policies to regional contexts through their Development and Reform Commissions (DRCs) and affiliated energy bureaus/divisions. Provincial-level energy bureaus (under provincial DRCs) translate national targets into regional plans—for example, defining solar installation quotas. Zhejiang Province, with the core positioning of “building a global highland for the photovoltaic industry,” aims to achieve the following goals by 2025: In terms of industrial scale, the output value of the photovoltaic industry will exceed CNY 250 billion (Chinese Currency), with production capacities for photovoltaic cells and modules reaching 90 GW and 110 GW, respectively, ranking among the top in China. For installed capacity, the province’s total photovoltaic power generation capacity will reach 27.5 million kilowatts, with distributed photovoltaic installations accounting for over 50%, achieving the “double wind and photovoltaic capacity” target two years ahead of schedule. In technological innovation, it plans to develop more than 30 standardized photovoltaic manufacturers listed in the national directory and 6–8 enterprises with annual revenues exceeding CNY 10 billion, promoting the industrialization of cutting-edge technologies such as perovskite, TOPCon, and HJT.

Municipal and county-level energy divisions (within local DRCs) serve as frontline executors, focusing on grassroots implementation. The solar policies in Hangzhou collectively aim to accelerate PV deployment in Hangzhou through planning, subsidies, streamlined services, and lifecycle management, aligning with carbon reduction goals and fostering regional renewable energy self-reliance. Furthermore, Hangzhou has been selected as a national carbon peak pilot city and is building on the city’s unique characteristics to drive its low-carbon transition. Leveraging its digital economy strengths, Hangzhou has established a “1 + N” dual carbon smart governance system, integrating carbon emission data through the “Energy Dual Carbon Smart Brain” to build a real-time monitoring and dynamic management platform covering industries, construction, transportation, and other key sectors.

4.2. County-Level Strategic Objectives and Implementation Pathways

Nestled in the northwestern mountainous region of Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province, Lin’an District is a dynamic hub of ecological innovation and economic growth. Covering 3118.72 square kilometers with a population of 652,000, it is renowned for its lush forests (81.93% coverage), two national nature reserves, and strategic role in advancing China’s dual carbon goals [

35].

Recent Chinese policies for the development of renewable energy are primarily centered around achieving low-carbon goals, or more specifically, the advocated ‘dual carbon’ targets. In July 2021, Lin’an District was recognized as one of the first provincial low-carbon pilot counties in Zhejiang Province. In order to attain these low-carbon development objectives, transitioning to renewable energy is a crucial pathway. At the same time, economic development remains one of the most important indicators for local governments. Given the significant reduction in the cost of PV technology in recent years, even though Lin’an’s solar resources are not as abundant as those in western China, the economic viability of investing in PV development has become increasingly favorable. By September 2022, the district incorporated an average of 1 kW of photovoltaic capacity per capita into its “14th Five-Year Plan” for PV power development, which is the province’s first district-level “14th Five-Year Plan” for photovoltaic power generation [

36]. The district aims to reach a population of 650,000 and achieve a total installed photovoltaic capacity of 650 MW by the end of 2025. It is projected that by 2025, photovoltaic generation will produce 650 million kWh, with the district’s total electricity consumption in 2022 being 4.87 billion kWh, representing approximately 13% of the total. Under the district’s planning assumptions, expanding PV at this scale would not only increase the share of clean electricity in the local power mix but also deliver tangible climate co-benefits by displacing a portion of grid electricity and thereby reducing associated carbon emissions. In this sense, the “1 kW per capita” target is framed as both an energy-transition measure and a practical pathway for local low-carbon development. To reach the goal, Lin’an has established a multi-solar development model based on three pillars: residential rooftop solar, industrial and commercial solar, and utility-scale ‘solar+’ power stations—each guided by distinct development rationales.

(1) Rooftop distributed PV aligns with both national policy imperatives (e.g., the Whole-County PV Pilot Program) and Zhejiang Province’s Common Prosperity Demonstration Zone objectives. By leveraging residential and public building rooftops, Lin’an increases rural income through PV-generated electricity revenue while advancing energy access. This model primarily operates on a leasing basis, where villagers or village collectives provide rooftop space for solar installations, attracting investors to fund the solar PV systems. Once the PV systems are grid-connected, the investors receive revenue from selling the generated electricity. In the initial phase, farmers incur no costs and, in return, receive an annual fixed rooftop leasing fee from the investors. The leasing fee varies depending on the amount of installed photovoltaic capacity. The annual unit income is calculated based on the number of solar panels installed, with each panel generating a rental income of approximately 20–50 yuan per year. For example, if a farmer’s rooftop installs 50 panels, and each panel generates a leasing income of 40 yuan annually, the farmer can earn an additional 2000 yuan per year.

(2) Utility-scale solar PV power plants capitalize on Lin’an’s abundant orchard and unused land resources. The district government prioritizes agrivoltaics projects, which combine solar panels with agricultural activities to maximize land productivity. Lin’an government has set 16 utility-scale solar power projects into the 14th Five-Year Plan, and the target installed capacity for these photovoltaic power stations has been set at 270 MW. This aligns with national land-use regulations, ensuring PV deployment does not encroach on arable land. These projects will gradually be connected to the grid and begin generating electricity in 2024 and 2025.

(3) Industrial and commercial PV responds to enterprises’ demand for cost savings. Lin’an’s above-national-average economic growth and dense industrial base (e.g., electronics, textiles) drive factory rooftop installations. Firms can reduce electricity costs by 15–20% through self-consumption of PV-generated power, incentivizing adoption without relying on subsidies.

These pillars reflect a contextual policy mix: rooftop PV addresses social equity, centralized projects optimize land use, and industrial PV supports economic competitiveness. As one official stated, “Each PV model solves a different problem—income inequality, land constraints, and energy costs—while contributing to our 650 MW target” (R3, District Development and Reform Bureau Official, 2024). Lin’an District’s mountainous terrain led to a strategic emphasis on agrivoltaics and rooftop PV, differing from flat regions’ large-scale ground-mounted solar farms. This flexibility allows counties to tailor policies to local strengths, such as leveraging existing industrial clusters or agricultural landscapes. By June 2025, the cumulative installed capacity had reached 710.6 MW, achieving more than 1 kW of photovoltaic capacity per capita. Overall, between 2021 and 2025, Lin’an’s installed PV capacity increased from less than 100 MW to 710.6 MW, accounting for approximately 13% of local electricity consumption (

Table 1).

5. Lin’an Practice

5.1. Policy Implementation Stages

Based on our investigation and research, we found that the development of photovoltaics in Lin’an during the 2021–2025 period can be divided into three distinct stages, each significantly influenced by the policies of higher-level governments, particularly the central government’s new regulations.

The first phase, spanning from 2021 to 2023, focused primarily on the development of rural rooftop PV systems. The government’s objective during this period was to leverage rooftop PV projects to increase the income of rural residents and promote common prosperity. This focus was driven by two key national policies. The first was the Whole-County PV Deployment Pilot Program, launched in 2021, which stipulated that, for pilot counties, no less than 20% of rural residential roofs should install PV panels, even though Lin’an District was not initially selected as a pilot county [

37]. The second was the “Thousands of Households, Thousands of Solar Panels Campaign,” which was explicitly outlined in the 14th Renewable Energy Plan. This initiative was aligned with the Rural Revitalization Strategy and aimed to deploy distributed PV systems on suitable rural rooftops or collective village lands, with the goal of establishing approximately 1000 PV demonstration villages. This included village-level collective ownership solar models and income-sharing leasing mechanisms for rural households.

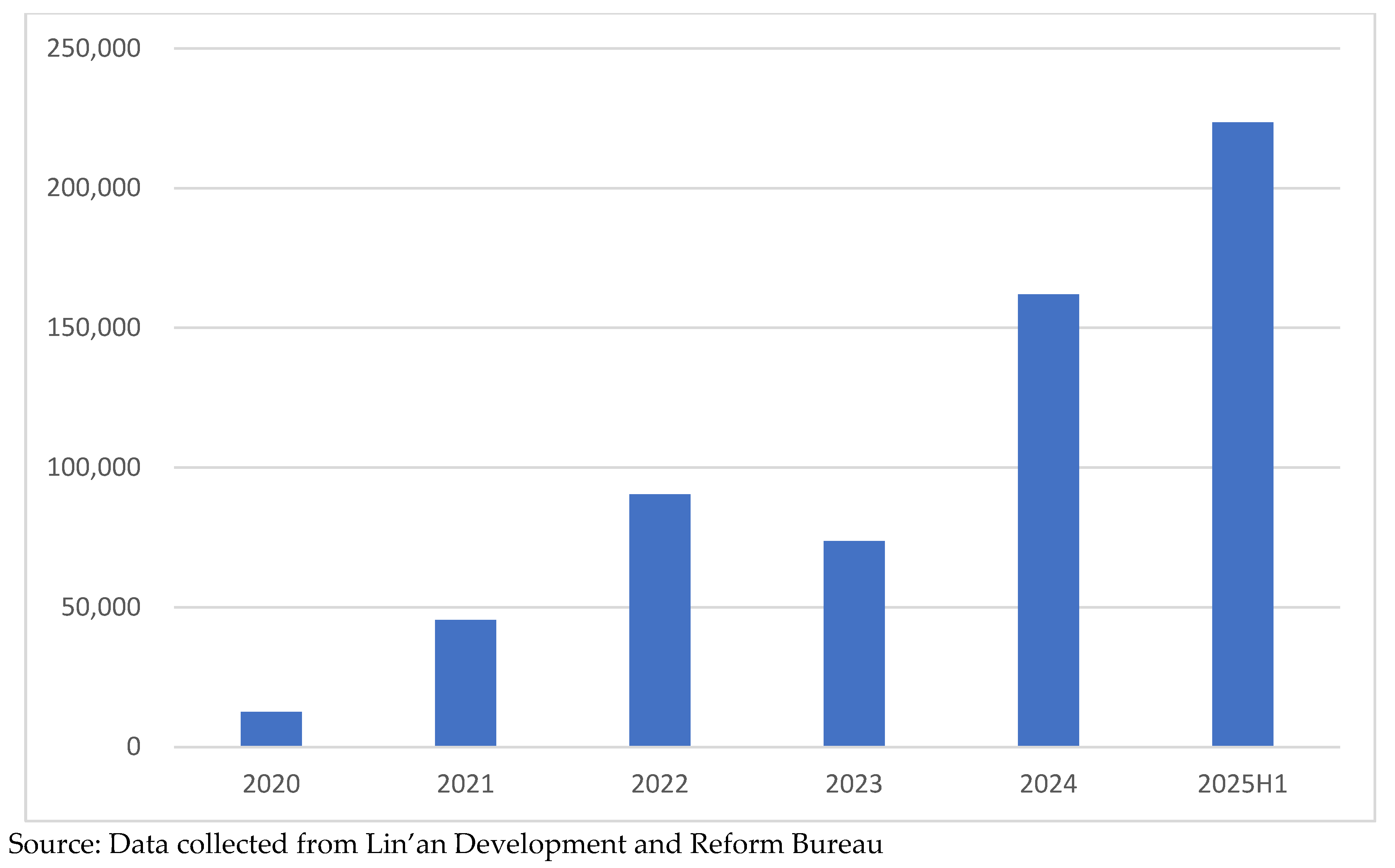

The second phase, from 2023 to 2024, saw the introduction of the National Notice on Supporting PV Industry Development and Regulating Land Use Management by the central government in 2023, which specifically outlined requirements for land use in photovoltaic power stations [

38]. The “Notice” calls for the exploration and research of advanced technologies and processes, the promotion of land-saving technologies and models, and the adoption of integrated utilization models that are suited to local conditions. It specifies the minimum height requirements for the lower edge of photovoltaic modules above planting soil or shrubs, as well as the spacing requirements for photovoltaic support structures. The notice encourages leaving gaps between photovoltaic panels and support structures. It also explores the possibility of installing photovoltaic arrays on existing buildings or structures located on agricultural land used for facilities. Additionally, the notice clarifies the output requirements for projects involving integrated land use. With the central government’s new regulations in place, Lin’an District quickly responded by accelerating the development plans for 16 utility-scale solar projects. Unlike rural distributed rooftop PV systems, which typically have installed capacities ranging from 10 to 20 kilowatts (kW), utility-scale solar projects—operating at the megawatt (MW) level—are critical in accelerating Lin’an’s progress toward its goal of 650 MW in installed capacity. These large-scale projects enable rapid capacity accumulation, complementing the more gradual contributions from smaller rooftop systems. In fact, as of this year 2024, the number of PV installation projects in Lin’an has reached over 2800, with the grid-connected installed capacity amounting to 162 MW—representing a 190% year-on-year growth in both indicators. Meanwhile, the cumulative installed PV capacity of Lin’an District has hit 480 MW.

The third phase, extending from 2024 to 2025 and beyond, was marked by the issuance of two critically important documents that have the potential to reshape the PV industry. The first document is the “Measures for the Development and Construction Management of Distributed Photovoltaic Power Generation”, which provides clear definitions for distributed photovoltaics, outlines industry management practices, specifies development processes, grid integration procedures, and operational models [

39]. The second document is the “Notice on Deepening the Marketization of Electricity Prices for New Energy and Promoting High-Quality Development of New Energy” (Development and Reform Price (2025) No. 136 [

40]). This document stipulates that, in principle, the electricity generated by new energy projects (wind and solar power) will all enter the electricity market, with the grid connection price determined through market transactions [

40]. New energy projects can either submit bid volumes for pricing or accept market-determined prices. Prior to this, the feed-in tariff for photovoltaic power was largely a fixed price, generally based on the desulfurized coal benchmark tariff in the region. However, with the shift to market-based trading, the price for PV projects will become uncertain, which in turn will make the revenue unpredictable. Both of these documents provide a transition period for the industry. The first document stipulates that distributed PV projects that are grid-connected before 1 May 2025 will still follow the original policy, with the new regulations only applying to projects connected after this date. The second document outlines that the electricity scale of existing new energy projects that are commissioned before 1 June 2025 will be adjusted in line with the current guaranteed power scale policies, while new incremental projects after 1 June 2025 will be subject to the new regulations. Following the release of these two documents, there was a surge in applications for grid connections, as developers rushed to complete photovoltaic projects before the policy changes took effect. By June 2025, Lin’an’s cumulative installed PV capacity had reached 710.6 MW, fulfilling its 2025 target six months ahead of schedule (

Figure 1).

5.2. Establishment of a PV Task Force and the Creation of a PV Construction Alliance

The district government has set up a special task force to coordinate all related work comprehensively. The task force, which aims to unify ideological understanding and form a joint operation mechanism, consists of departments such as the District Development and Reform Bureau, the Lin’an Branch of the Bureau of Planning and Natural Resources, the Ecological Environment Branch, the Water Resources and Hydropower Bureau, the Bureau of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, and the Lin’an Branch of the State Grid Power Supply Company. The office of the task force is located in the District Development and Reform Bureau, responsible for the daily office work (

Table 2).

The PV construction task force in Lin’an operates in a substantive, problem-solving manner. Through the “one-stop” reform that bundles forest-related approvals, water-related approvals, and environmental impact assessments, the task force reduces information silos across departments and streamlines administrative procedures. As one district-level bureau official noted, “The one-stop review has improved efficiency and shortened procedural review time, which benefits both the government and project delivery” (R3, District Development and Reform Bureau, 2025). Reflecting these process gains, interviewees reported an average reduction of more than 30% in the time from project approval to implementation and operation. In 2023, 26 new PV projects were added to the inventory, driving fixed-asset investment of CNY 1.514 billion.

Meanwhile, efforts have been made to guide enterprises to participate more fully in delivery. Through a competitive selection process, six PV enterprises with strong capacity, solid qualifications, and extensive experience were selected to form the Lin’an PV Industry Alliance and were included on a government-recommended list as the main force in PV construction. An alliance staff member explained the rationale behind this approach: “The firms selected for the PV alliance are established companies with a solid track record and extensive experience in PV construction and operations, which helps reduce project risks” (R18, Alliance staff, 2024). This selection-and-recommendation mechanism therefore functions not only as an implementation arrangement but also as a local risk-management tool in market participation.

5.3. Formation of a PV Expert Database and Implementation of a Dual Safety Check Acceptance System

To strengthen technical screening and reduce safety risks under rapid deployment, Lin’an established a local expert database with 83 experts currently listed. These experts are responsible for verification and safety acceptance for both newly built PV projects and installations from previous years. By the time of our fieldwork, acceptance had been completed for 20 newly built projects and verification for 163 existing projects. From the perspective of review integrity, one academic expert emphasized the value of independence: “A third-party expert pool helps assess projects from a more impartial and fairer standpoint and reduces project risks” (R22, Academic expert, 2024).

Building on this expert pool, Lin’an implemented a “dual acceptance” mechanism for newly installed PV projects before grid connection. Property owners and construction units are encouraged to organize self-acceptance, while industry association experts lead the pre-grid-connection acceptance, ensuring that projects can be connected only when both engineering acceptance and grid-connection acceptance are “double-qualified.” A grid connection management staff member described the system’s effect in practical terms: “The government’s dual-acceptance system is essentially a double safeguard, and it also pushes our grid acceptance to be more professional and more thorough” (R16, Grid connection management staff, 2024). By the end of 2023, Lin’an had formulated dual-acceptance standards covering six major items and 59 sub-items. Among the 163 verified PV projects, 155 rectification notices were issued, indicating a governance approach that couples rapid expansion with systematic quality correction.

6. Discussion

To delineate the underlying governance logic of Lin’an’s PV policies and their embeddedness within China’s hierarchical administrative system, this section engages two foundational theoretical frameworks: policy instrument typology and adaptive governance theory. The policy instrument framework serves to decode the combinatorial logic and functional value of Lin’an’s policy tools, while adaptive governance highlights the dynamic processes of coordination, learning, and institutional adjustment that occur within a centrally steered but locally adaptive governance structure. This theoretical anchoring not only contextualizes Lin’an’s practices within broader scholarly dialogues on policy adaptability and multilevel governance but also reveals the micro-processes of policy implementation in China’s decentralized authoritarian context.

6.1. Policy Instrument Combination and Functional Mechanisms in Lin’an’s PV Governance: A Policy Instrument Theory Perspective

Howlett categorizes policy instruments into three mutually exclusive yet complementary types—mandatory, mixed, and voluntary—based on the degree of state intervention and the autonomy afforded to non-state actors [

41]. Lin’an’s PV governance has evolved a “three-dimensional instrument portfolio” that adapts to the shifting demands of PV development (from distributed rural rooftops to utility-scale projects and market-oriented regulation). Each instrument type fulfills distinct governance functions, and their synergistic interaction constitutes the core of Lin’an’s policy effectiveness.

6.1.1. Mandatory Instruments: Institutionalizing Baseline Compliance and Risk Mitigation

Mandatory instruments, defined by their top-down, command-and-control nature, function as the “governance backbone” of Lin’an’s PV development, tasked with safeguarding regulatory compliance and mitigating systemic risks. Key measures include the “dual safety inspection and acceptance system,” “land use normatives,” and “enterprise qualification screening”—all of which impose non-negotiable standards for project initiation, implementation, and operation.

The dual safety inspection and acceptance system, encompassing engineering quality inspection and grid-connection eligibility verification, establishes a rigid quality threshold for PV projects. Prior to grid integration, third-party auditors assess structural stability (e.g., rooftop load-bearing capacity), electrical safety (e.g., wiring compliance), and operational readiness (e.g., inverter functionality). Since its formalization in 2022, this system has reduced the failure rate of Lin’an’s PV projects from 8.2% in 2022 to 1.9% in 2024, with no major safety incidents reported (R14, District-level grid technical staff, 2025). This outcome validates the theoretical proposition that mandatory instruments are critical for addressing “information asymmetry” and “moral hazard” in renewable energy projects, as they impose exogenous constraints on actors’ opportunistic behaviors [

41].

Land use normatives align Lin’an’s local practices with the central government’s “arable land protection red line”—a non-negotiable national policy objective. For the 16 utility-scale PV projects included in Lin’an’s 14th Five-Year Plan, these normatives ensured that no permanent farmland was occupied, thereby avoiding regulatory non-compliance risks that could lead to project suspension or central oversight penalties. From a theoretical standpoint, this underscores how mandatory instruments act as a “vertical policy bridge,” translating abstract central mandates into concrete local operational standards [

12].

6.1.2. Mixed Instruments: Aligning Market Incentives with Governance Objectives

Mixed instruments integrate market-oriented mechanisms with targeted state guidance to stimulate stakeholder participation without relying on direct fiscal subsidies. In Lin’an’s case, these instruments focus on optimizing the “economic viability” of PV projects for enterprises and rural households, thereby addressing the “participation gap” that often plagues renewable energy policies in developing contexts.

For industrial and commercial enterprises, the promotion of the “self-consumption with surplus grid feed-in” model constitutes a core mixed instrument. Lin’an’s dense industrial clusters generate sustained electricity demand, and on-site PV self-consumption allows enterprises to reduce dependence on grid-supplied power—thus lowering operational costs. Interview data from industrial stakeholders indicate that this model reduces overall electricity expenditures by 18–22% for participating firms (R17, PV company staff, 2024). This aligns with Howlett’s argument that mixed instruments excel at “incentive alignment”: by linking PV adoption to enterprises’ cost-saving objectives, the state avoids the inefficiencies of top-down mandates while still advancing renewable energy targets [

41].

For distributed rural rooftop projects, mixed instruments take the form of standardized contractual templates and streamlined grid-connection procedures. These measures reduce transaction costs for both investors (e.g., by clarifying rooftop leasing terms) and rural households (e.g., by specifying maintenance responsibilities), addressing the uncertainty barriers that previously discouraged small-scale project uptake. Notably, the standardization of contracts also mitigates disputes between households and investors by codifying rights and obligations in a transparent, locally legible format.

6.1.3. Voluntary Instruments: Facilitating Collaborative Governance and Efficiency Gains

Voluntary instruments rely on inter-actor collaboration and self-organization to reduce administrative friction, leveraging the expertise and resources of non-state actors to complement state capacity. In Lin’an, these instruments are embodied in the “PV Construction Alliance,” “Expert Database,” and “Interagency Task Force”—all of which institutionalize collaboration across government departments, enterprises, and technical experts.

The PV Construction Alliance, formed through a competitive selection process that prioritized technical capability, project experience, and compliance records, aggregates 6 core enterprises into a coordinated platform for procurement, construction, and operation and maintenance (O&M). It standardizes O&M practices, shortening response times for equipment failures from 48 h to 10 h (R3, District Development and Reform Bureau Official, 2024)—a critical improvement for rural projects where delayed maintenance can lead to significant revenue losses for households. Theoretically, this reflects Howlett’s emphasis on voluntary instruments as “efficiency enhancers”, by delegating operational tasks to capable non-state actors, the state reduces administrative burden while improving service quality [

41].

The interagency task force—comprising representatives from 7 key departments implements a “one-stop approval” process that integrates previously siloed administrative procedures. For instance, land compliance verification led by the Bureau of Planning and Natural Resources and grid-connection feasibility assessments led by State Grid are now conducted in parallel, rather than sequentially, reducing the total approval timeline. This directly addresses the “administrative fragmentation” that characterizes China’s governance system by institutionalizing cross-departmental information sharing and joint decision-making [

20].

6.1.4. Synergistic Coupling of Instruments: A Dynamic Governance Chain

Lin’an’s policy instrument portfolio is not a static collection of measures but a dynamically adaptive “governance chain” characterized by complementary interactions: mandatory instruments set non-negotiable baselines, mixed instruments activate market participation, and voluntary instruments enhance implementation efficiency. This synergy is most evident in the governance of utility-scale PV projects, where the three instrument types operate in sequence: A project first undergoes mandatory land use review to ensure compliance with central farmland protection rules—eliminating regulatory risks at the outset. It then adopts mixed instruments to improve economic viability, addressing the financial sustainability gap that often derails large-scale renewable energy projects. Finally, it joins the PV Construction Alliance (a voluntary instrument) to access standardized O&M services, ensuring long-term operational efficiency. This sequential integration has significantly improved project delivery: by 2024, the on-schedule grid-connection rate for utility-scale projects reached 98%, a marked increase from the 75% rate in 2022 (R16, Grid connection management staff, 2025).

From a theoretical perspective, this synergy validates Howlett’s contention that policy effectiveness depends not on individual instruments but on their “strategic combination” to address multi-faceted governance challenges [

42]. Moreover, it supplements existing scholarship by demonstrating how such instrument coupling operates at the county scale—a level of analysis often overlooked in studies of Chinese energy policy [

14].

6.2. Adaptive Governance in Lin’an’s PV Governance—Mechanisms of Flexibility, Collaboration, and Iterative Learning

As revealed in the previous analysis of the policy instrument portfolio for PV governance in Lin’an, through the three-dimensional synergy of “anchoring compliance baselines via mandatory policy instruments, stimulating market participation through mixed policy instruments, and enhancing collaboration efficiency with voluntary policy instruments”, the local government has established an operational foundation for addressing the complexities of PV governance. However, a further question arises: What governance objectives do the dynamic adjustment and combination of these policy instruments ultimately serve? This section adopts the lens of adaptive governance—a theoretical framework that emphasizes flexibility, multi-actor collaboration, and iterative learning in addressing complex socio-ecological and policy systems [

10,

11,

12]. Unlike frameworks focused on hierarchical conflict, adaptive governance highlights how local actors proactively adjust strategies, integrate diverse interests, and respond to feedback to achieve long-term policy goals. For Lin’an’s PV development, this framework illuminates three core adaptive processes: responding to top-down policy perturbations, reconciling cross-sectoral goal conflicts, and adapting to market expansion—each reflecting the local state’s capacity to balance central mandates with contextual specificity.

In authoritarian contexts like China, adaptive governance manifests as a “constrained flexibility”, while the central government sets overarching goals. Local governments retain room to innovate implementation pathways—provided they align with national red lines. Lin’an’s PV governance exemplifies this: it does not challenge central authority but instead adapts central policies to its mountainous terrain, rural–urban hybrid structure, and industrial characteristics. Below, we analyze how these adaptive attributes operate across three critical governance challenges.

6.2.1. Adaptive Responses to Central Policy Perturbations: Aligning National Mandates with Local Resources

A defining feature of adaptive governance is the ability to respond to “external perturbations”—such as shifts in central policy—without abandoning core local goals. For Lin’an, the 2023 central government-issued document on land use management represented a major perturbation. Lin’an’s 2025 PV capacity target relied heavily on utility-scale projects, which required significant land—but the district’s limited flat arable land risked making the target unattainable under the new rule. Lin’an’s adaptive response centered on contextual innovation of land-use models, leveraging its abundant non-arable resources (orchards) to create the “agrivoltaics model”—a practice that integrates PV installations with shade-tolerant agricultural production. This model addressed the central mandate while unlocking local land potential: PV modules were installed 1.5–2.0 m above the ground, allowing farming activities to continue beneath and avoiding ecological disruption. The model was not designed unilaterally by the government; instead, it was co-developed with agricultural operators (to ensure crop compatibility) and PV developers (to optimize module placement), reflecting polycentric collaboration. Moreover, this adaptation was not a one-time adjustment but part of a feedback loop: after initial pilot projects, Lin’an revised module height and crop selection based on farmer feedback and ecological monitoring—exemplifying iterative learning, a core tenet of adaptive governance [

10].

6.2.2. Adaptive Resolution of Cross-Sectoral Goal Conflicts: Collaborative Integration of Different Objectives

A key challenge in the adaptive governance of Lin’an’s PV projects lies in reconciling the divergent goal orientations and review criteria of core administrative departments—the Development and Reform Bureau (DRB), the Bureau of Natural Resources and Planning (BNRP), and the local branch of State Grid—whose historical practice of isolated, parallel reviews had long led to information silos, redundant work, and project delays. To address this, adaptive governance institutionalized regular joint review meetings, creating a platform for real-time information sharing and on-site conflict resolution that transformed fragmented administrative processes into collaborative efficiency. Each department’s review logic is deeply rooted in its unique mandate, resulting in clear distinctions: the DRB focuses on development alignment and investment efficiency; the BNRP, by contrast, prioritizes “land compliance and spatial order,” rejecting any project that encroaches on permanent basic farmland or ecological red lines, enforcing slope stability rules, and requiring efficient land use; State Grid, meanwhile, centers exclusively on “grid safety and compatibility,” reviewing technical parameters like inverter specifications and voltage levels, and verifying that regional grid capacity can absorb the project’s electricity.

This divergence in priorities, when paired with isolated reviews, gave rise to two critical problems: information asymmetry often led to “approval reversals,” where the DRB might greenlight a project for meeting capacity targets only for the BNRP to later reject it for land non-compliance, or State Grid to deny grid access due to technical mismatches—forcing developers to restart the application process and delaying projects. The joint review meetings established under adaptive governance resolved these issues by integrating core actions into a single session: using a shared digital platform, departments present their preliminary assessments simultaneously—for instance, during the review of a 50 MW agrivoltaics project, the DRB confirmed alignment with capacity targets, the BNRP flagged excessive land coverage, and State Grid requested additional energy storage, all in real time to avoid post-approval reversals.

By 2024, the impact of this adaptive mechanism was tangible: the number of PV projects delayed by interdepartmental conflicts dropped by 72% compared to 2022, and average review time was reduced by 61% (R2, District Development and Reform Bureau Official, 2024). This approach embodies the core strength of adaptive governance: instead of prioritizing one department’s mandate over others, it creates a space where divergent goals are reconciled through collaboration, turning administrative fragmentation into a driver of efficiency and offering a replicable model for resolving cross-sectoral tensions in PV governance across other regions.

6.2.3. Adaptive Regulation of Market Expansion: Balancing Order and Dynamism Through Dynamic Oversight

As PV markets grow, adaptive governance requires regulators to adjust oversight to new challenges without stifling innovation—a balance Lin’an achieved as its PV enterprise count expanded from 6 in 2021 to over 50 in 2024. The rapid influx led to emergent issues: substandard modules, false rental commitments to rural households, and inadequate post-installation maintenance. A rigid “one-size-fits-all” regulatory response risked discouraging small enterprises, while lax oversight would erode public trust.

Lin’an’s adaptive regulatory strategy centered on differentiated supervision and credit-based feedback loops, tailored to enterprise behavior and market conditions:

- 4.

Risk-based differentiation: Core enterprises in the PV Construction Alliance with proven compliance records received streamlined reviews, while new or high-risk enterprises underwent enhanced oversight, such as pre-construction module testing and quarterly maintenance audits. This avoided overburdening reliable actors while targeting risks—reflecting adaptive governance’s focus on “proportional intervention” [

10].

- 5.

Credit-driven feedback: Enterprise performance was formalized into a dynamic credit rating database, which determined eligibility for future projects. Poorly rated enterprises were suspended, while high-performing ones gained priority access to resources (e.g., rooftop contracts)—creating incentives for self-regulation.

- 6.

Iterative rule refinement: The government revised the credit criteria based on enterprise and household feedback to address unforeseen gaps (e.g., enterprises ignoring maintenance requests).

Notably, the strategy was not static: as the market matured, Lin’an further relaxed oversight for low-risk actors—demonstrating how adaptive governance scales back intervention as systems become more self-regulating [

11].

7. Conclusions

In conclusion, the policy planning process at the local level in China is a complex undertaking that involves setting specific quantitative targets. These targets are influenced by higher-level governmental policies, especially those from the central government [

43]. However, local governments also consider the unique circumstances of their respective regions and actively engage with local stakeholders to gather their input. Once the objectives are defined, local governments adopt a problem-oriented approach, continuously adjusting strategies and fine-tuning technical goals [

12]. Throughout this process, the government’s service capabilities and regulatory capacities are consistently enhanced [

44]. This alignment has enabled China to lead global renewable energy deployment—accounting for over 40% of worldwide solar and wind installations—by combining top-down mandates with bottom-up execution, ensuring that renewable energy policies drive both environmental sustainability and socioeconomic development across its vast territory.

The experience of China’s PV sector demonstrates that effective governance is a response to market-generated challenges rather than a static set of rules. While central oversight provides necessary macroeconomic coordination, the real engine of progress lies in local governments’ ability to translate policy visions into actionable solutions. As they confront the complexities of distributed energy integration—balancing technical innovation, market efficiency, and grid stability—local authorities are not merely executing orders but actively co-designing regulatory frameworks. This adaptive governance model not only addresses immediate sectoral challenges but also cultivates a broader administrative capability: the capacity to anticipate, respond, and innovate in the face of evolving market demands.

In essence, the enhancement of local governance in China is a story of pragmatic adaptation. By aligning policy implementation with market realities—especially in sectors like renewable energy that demand technical and institutional sophistication—local governments have proven themselves capable of transforming challenges into opportunities for capacity building. As China continues its transition toward a low-carbon economy, this governance agility will remain a critical asset, ensuring that policy objectives are met with both efficiency and foresight.

Our study also has several limitations that warrant attention. First, given that Lin’an’s economic development exceeds the national average and exhibits a relatively high level of market openness, the findings may not be fully generalizable to some underdeveloped regions in China, where socioeconomic conditions and institutional contexts differ significantly. Second, the developmental model observed in Lin’an is not without challenges, including tensions between market-driven approaches and governmental regulatory frameworks, as well as operational and maintenance issues that require ongoing management.

To address these gaps, future research should continue tracking the evolution of Lin’an’s model while expanding comparative analyses across diverse cities and regions with varying levels of economic development, regulatory environments, and institutional capacities. Such studies would enhance the external validity of our findings and shed light on how contextual factors shape policy implementation and sustainable development outcomes. Importantly, the experience of Lin’an offers valuable insights for rural areas in China and solar energy development in developing countries globally, contributing to both theoretical discussions on authoritarian policy-making frameworks and practical initiatives aimed at accelerating equitable and resilient global energy transitions.