Simultaneous Stabilization of Cu/Ni/Pb/As Contaminated Soil by a ZVI-BFS-CaO Composite System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.1.1. Experimental Soil and Physicochemical Properties

2.1.2. Heavy Metal and Acid Reagents

2.1.3. Heavy Metal Stabilization Materials and Basic Information

2.2. Liquid Phase Equilibrium Experiments

2.3. Soil Stabilization Experiments

2.3.1. Preparation of Contaminated Soil

2.3.2. Stabilization Procedures for Contaminated Soil

2.3.3. Determination of Leaching Concentration and Stabilization Rate

2.4. Long-Term Maintenance Evaluation Experiments

2.4.1. Wet–Dry Cycles Experiments

2.4.2. Freeze–Thaw Cycles Experiments

2.5. Characterization Methods

3. Results and Discussion

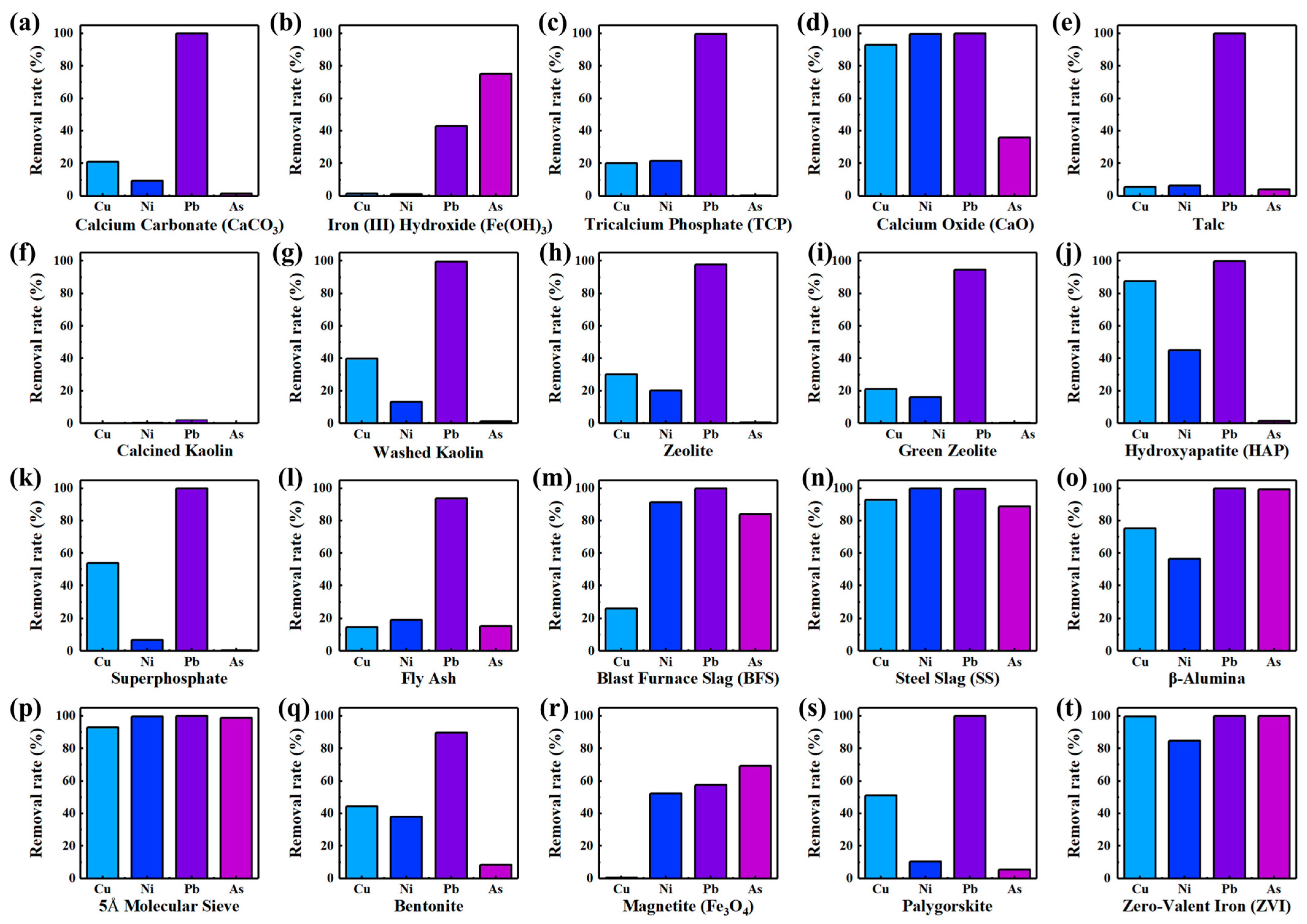

3.1. Liquid Phase Equilibrium Results

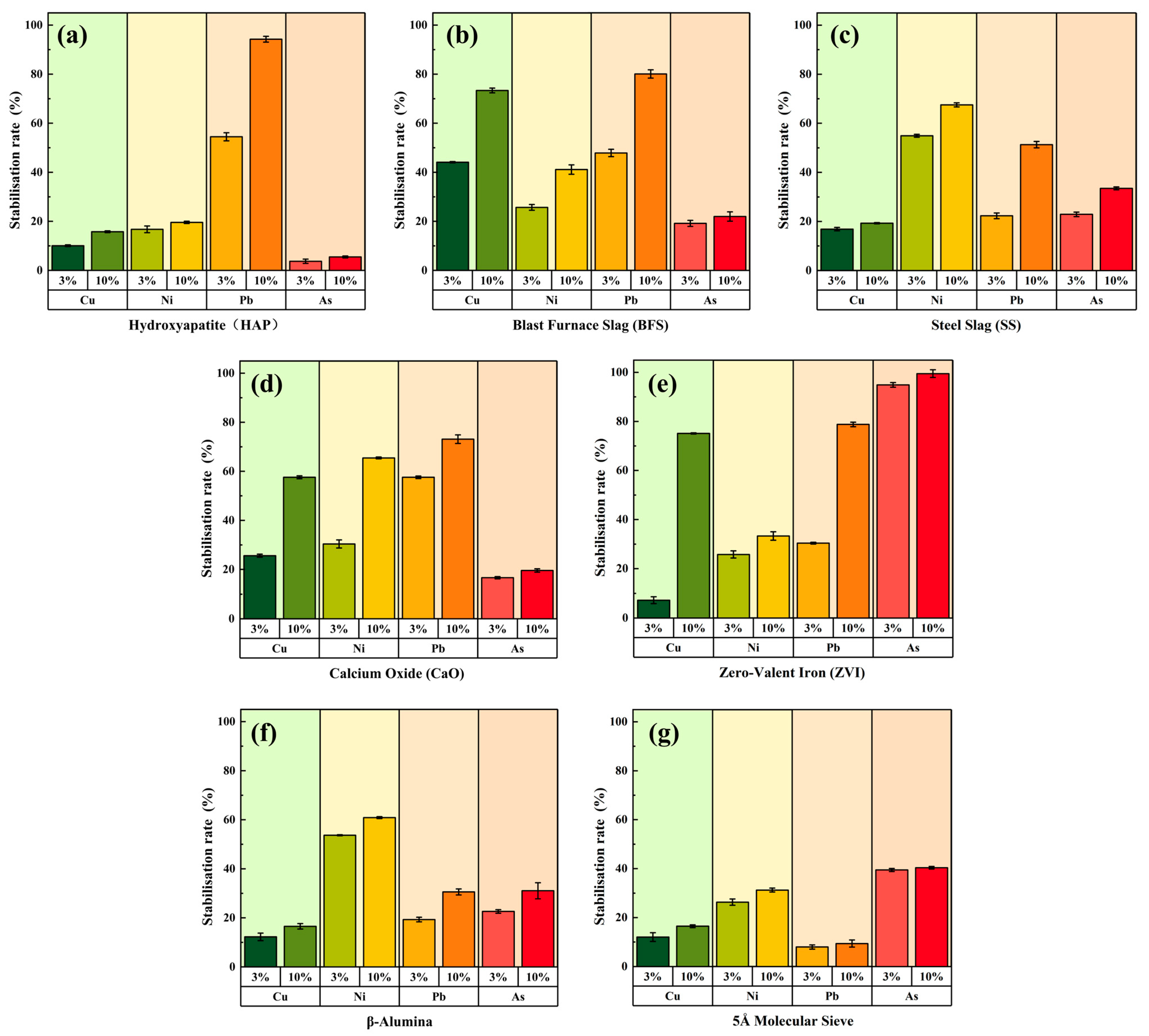

3.2. Effect of Single Stabilization Material on Soil Heavy Metal Stabilization

3.3. Stabilization of Heavy Metals in Soil by Composite Materials

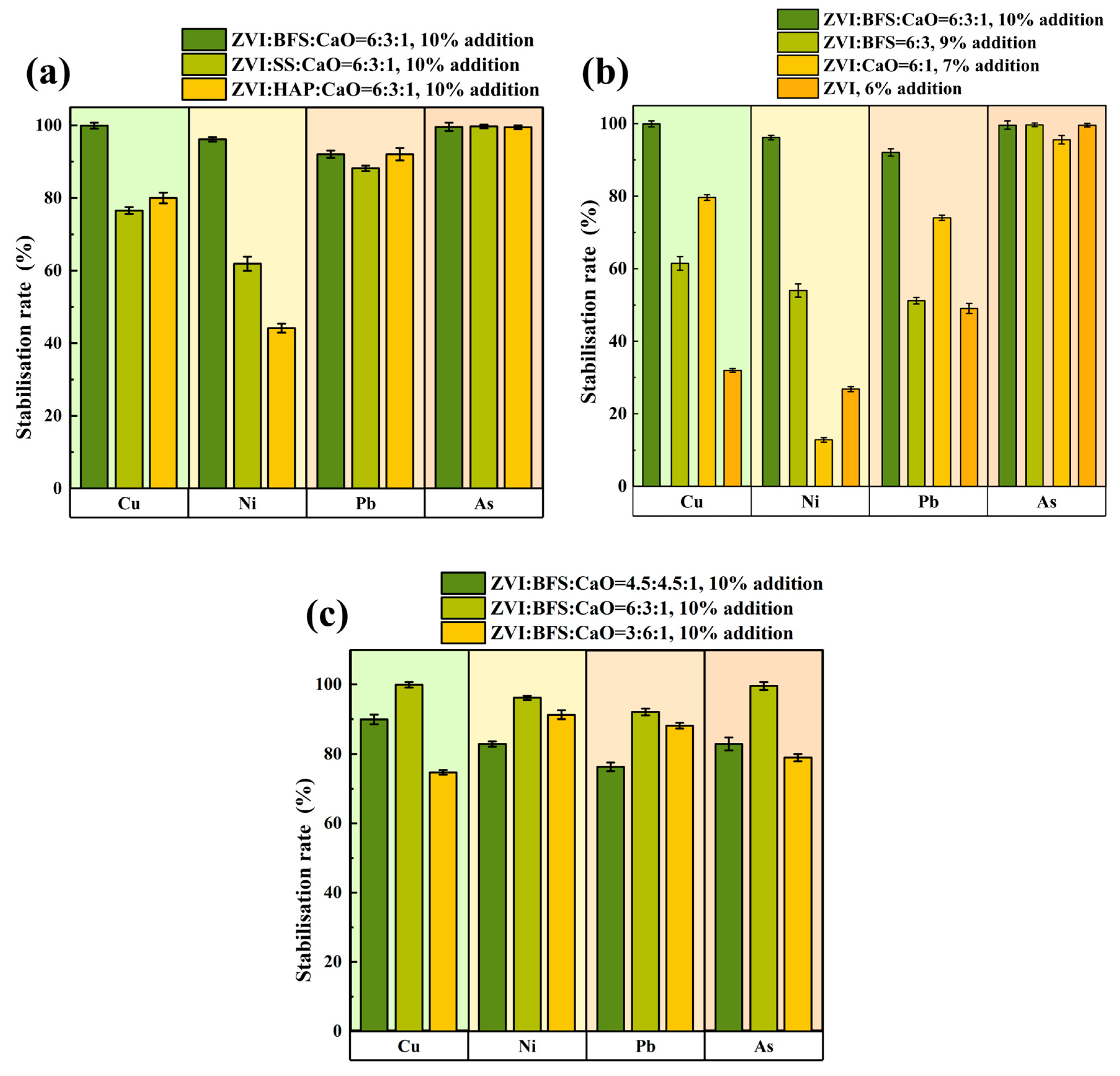

3.3.1. Stabilization Performance Affected by Composite Material Type

3.3.2. Stabilization Performance Affected by ZVI, BFS and CaO

3.3.3. Stabilization Performance Affected by Components’ Proportion

3.4. Potential Stabilization Mechanisms of Cu, Ni, Pb, and As

3.4.1. XRD Analysis

3.4.2. XPS Analysis

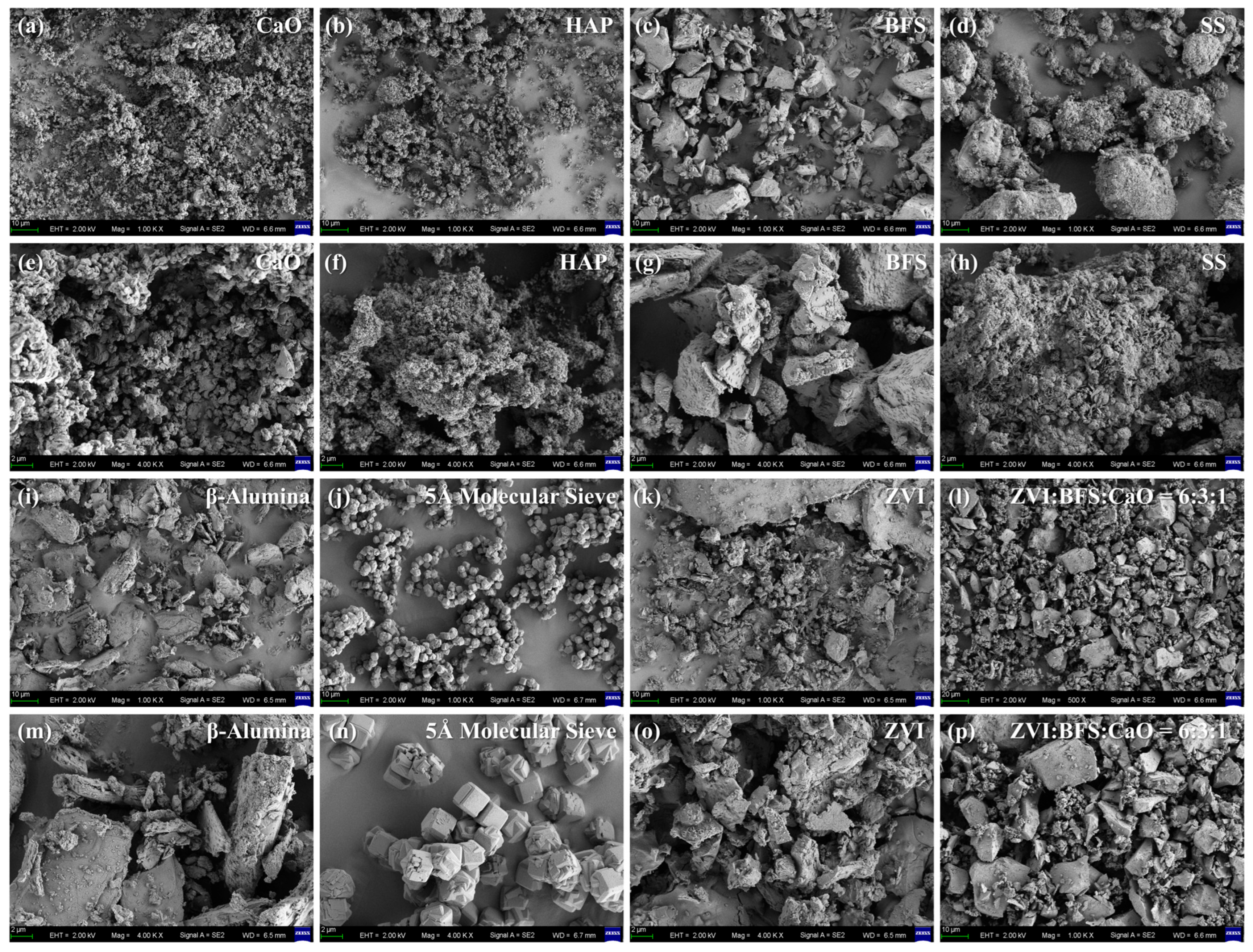

3.4.3. SEM-EDS Analysis

3.5. Long-Term Effectiveness Assessment

3.6. Limitations and Future Prospects

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BJH | Barrett–Joyner–Halenda |

| BET | Brunauer–Emmett–Teller |

| BFS | blast furnace slag |

| C-S-H | calcium silicate hydrate |

| EDS | energy dispersive spectroscopy |

| EXAFS | X-ray absorption fine structure |

| GGBS | ground granulated blast furnace slag |

| HAP | hydroxyapatite |

| ICP-MS | inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry |

| S/S | solidification/stabilization |

| SEM | scanning electron microscopy |

| SS | steel slag |

| TCP | tricalcium phosphate |

| XPS | X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| XRF | X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy |

| ZVI | zero-valent iron |

References

- Cui, W.; Li, X.; Duan, W.; Xie, M.; Dong, X. Heavy metal stabilization remediation in polluted soils with stabilizing materials: A review. Environ. Geochem. Health 2023, 45, 4127–4163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montaño-López, F.; Biswas, A. Are heavy metals in urban garden soils linked to vulnerable populations? A case study from Guelph, Canada. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, P.; Xu, D.; Yue, J.; Ma, Y.; Dong, S.; Feng, J. Recent advances in soil remediation technology for heavy metal contaminated sites: A critical review. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 156417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jia, S.; Liu, J. Solidification, remediation and long-term stability of heavy metal contaminated soil under the background of sustainable development. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasciucco, E.; Pasciucco, F.; Castagnoli, A.; Iannelli, R.; Pecorini, I. Removal of heavy metals from dredging marine sediments via electrokinetic hexagonal system: A pilot study in Italy. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, D.-M.; Fu, R.-B.; Wang, J.-X.; Shi, Y.-X.; Guo, X.-P. Chemical stabilization remediation for heavy metals in contaminated soils on the latest decade: Available stabilizing materials and associated evaluation methods—A critical review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 321, 128730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, S.; Annachhatre, A.P. A review on recent trends in solidification and stabilization techniques for heavy metal immobilization. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2023, 25, 733–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-eswed, B.I. Chemical evaluation of immobilization of wastes containing Pb, Cd, Cu and Zn in alkali-activated materials: A critical review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 104194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.K.; Wang, H.L.; He, L.Z.; Lu, K.P.; Sarmah, A.; Li, J.W.; Bolan, N.; Pei, J.C.; Huang, H.G. Using biochar for remediation of soils contaminated with heavy metals and organic pollutants. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 8472–8483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yang, C.; Zhao, M.; Yang, K.; Shen, R.; Zheng, Y. Immobilization potential of Cr(VI) in sodium hydroxide activated slag pastes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 321, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajorloo, M.; Ghodrat, M.; Scott, J.; Strezov, V. Heavy metals removal/stabilization from municipal solid waste incineration fly ash: A review and recent trends. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2022, 24, 1693–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meer, I.; Nazir, R. Removal techniques for heavy metals from fly ash. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2018, 20, 703–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Shi, T.; Ni, W.; Li, K.; Gao, W.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Y. The mechanism of hydrating and solidifying green mine fill materials using circulating fluidized bed fly ash-slag-based agent. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 415, 125625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Wei, T.; Li, S.; Lv, Y.; Miki, T.; Yang, L.; Nagasaka, T. Immobilization persistence of Cu, Cr, Pb, Zn ions by the addition of steel slag in acidic contaminated mine soil. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 412, 125176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Arif, A.; Munir, M.A.; Naz, M.Y.; Shukrullah, S.; Rahman, S.; Jalalah, M.; Almawgani, A.H.M. Statistically Analyzed Heavy Metal Removal Efficiency of Silica-Coated Cu0.50Mg0.50Fe2O4 Magnetic Adsorbent for Wastewater Treatment. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 47623–47634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, M.; Ma, Y. Influences of Biochar on Bioremediation/Phytoremediation Potential of Metal-Contaminated Soils. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 929730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirela, G.; Terzi, M.H.; Durgun, M.B. Heavy metal enrichments in rural environment soils, pollution dynamics, source identification, and the role of subsurface mineralizations. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 35858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tye, A.M.; Young, S.; Crout, N.M.J.; Zhang, H.; Preston, S.; Zhao, F.J.; McGrath, S.P. Speciation and solubility of Cu, Ni and Pb in contaminated soils. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2004, 55, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jing, J.; Li, Y.Y.; Zhang, Y.X.; Liu, Y.Z. Bioavailability and Speciation of Potentially Toxic Trace Metals in Limestone-Derived Soils in a Karst Region, Southwestern China. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2025, 236, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Yang, H.; Zhao, T. Multistage stabilization of Cd, Pb, Zn, Cu and As in contaminated soil by phosphorus-coated nZVI layered composite materials: Characteristics, process and mechanism. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 476, 134991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Fu, K.; Chen, S.; Zhou, Q.; Zhu, L.; Yao, J. Stabilization of Copper, Lead, and Zinc in Copper Smelting Slag Tailings by Sulfate-reducing Bacteria Using Typical Industrial By-product Gypsum as a Sulfur Source. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2025, 236, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NY/T 1377-2007; Determination of pH in Soil. Ministry of Agriculture: Beijing, China, 2007.

- Ciesielski, H.; Sterckeman, T. A comparison between three methods for the determination of cation exchange capacity and exchangeable cations in soils. Agronomie 1997, 17, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basta, N.T.; Ryan, J.A.; Chaney, R.L. Trace element chemistry in residual-treated soil: Key concepts and metal bioavailability. J. Environ. Qual. 2005, 34, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Yu, L.; Wang, T.; Wang, J.; Liu, T. Review of soil heavy metal pollution in China: Spatial distribution, primary sources, and remediation alternatives. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 181, 106261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xie, Z.; Li, J.; Xu, J.; Chen, Z.; Naidu, R. Assessment of toxicity of heavy metal contaminated soils by the toxicity characteristic leaching procedure. Environ. Geochem. Health 2006, 28, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Huang, X.; Wang, L. Stabilization Effect of Combined Stabilizing Agent on Heavy Metals in Hazardous Waste Incineration Fly Ash and Effect on Solidification Volume. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffar, F.H.; Othman, M.H.D.; Ismail, N.J.; Puteh, M.H.; Kurniawan, T.A.; Abu Bakar, S.; Abdullah, H. Hydroxyapatite-based materials for adsorption, and adsorptive membrane process for heavy metal removal from wastewater: Recent progress, bottleneck and opportunities. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2024, 164, 105668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Shen, X.; Qiu, S.; Zhang, L.; Ma, Y.; Liang, J. Clay-Based Materials for Heavy Metals Adsorption: Mechanisms, Advancements, and Future Prospects in Environmental Remediation. Crystals 2024, 14, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.K. A review on the adsorption of heavy metals by clay minerals, with special focus on the past decade. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 308, 438–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleraky, M.I.; Razek, T.M.A.; Hasani, I.W.; Fahim, Y.A. Adsorptive removal of lead, copper, and nickel using natural and activated Egyptian calcium bentonite clay. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Hu, J.; Zheng, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Lv, G.; Liao, L. Clay minerals and clay-based materials for heavy metals pollution control. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skoczko, I.; Szatyłowicz, E. Removal of heavy metal ions by filtration on activated alumina-assisted magnetic field. Desalination Water Treat. 2018, 117, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Qu, G.; Xu, R.; Liu, X.; Jin, C. Iron-based materials for immobilization of heavy metals in contaminated soils: A critical review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelbasir, S.M.; Khalek, M.A.A. From waste to waste: Iron blast furnace slag for heavy metal ions removal from aqueous system. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 57964–57979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, W.L.; Tang, K.; Chen, Y.Q.; Chen, Z.; Lan, Y.H.; Hong, Y.B.; Lan, W.G. Regulating the particle sizes of NaA molecular sieves toward enhanced heavy metal ion adsorption. New J. Chem. 2024, 48, 7863–7874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilardi, G.; Mpouras, T.; Dermatas, D.; Verdone, N.; Polydera, A.; Di Palma, L. Nanomaterials application for heavy metals recovery from polluted water: The combination of nano zero-valent iron and carbon nanotubes. Competitive adsorption non-linear modeling. Chemosphere 2018, 201, 716–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, R.; Liu, W.; Cheng, L.; Jiang, Q.; Zhang, Y. Exploratory of immobilization remediation of hydroxyapatite (HAP) on lead-contaminated soils. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 26674–26684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, D.-X.; Ren, C.; Wang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Li, W. Characterization of Lead Uptake by Nano-Sized Hydroxyapatite: A Molecular Scale Perspective. ACS Earth Space Chem. 2018, 2, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, A.; Ye, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, G. Micro/nanostructured hydroxyapatite structurally enhances the immobilization for Cu and Cd in contaminated soil. J. Soils Sediments 2016, 16, 2030–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Cao, W.; Dong, K.; Li, H.; Wang, D.; Xu, Y. Hydroxyapatite and its composite in heavy metal decontamination: Adsorption mechanisms, challenges, and future perspective. Chemosphere 2024, 352, 141367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, A.S.; Chavali, R.V.P. Solidification/stabilization of copper-contaminated soil using magnesia-activated blast furnace slag. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2023, 8, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Liu, S.; Liu, M. Solidification/stabilization of lead-contaminated soils by phosphogypsum slag-based cementitious materials. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 857, 159552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, J.; Liu, Y.; Yang, H.; Guan, X.; Sun, Y. Remediation of arsenic contaminated soil by sulfidated zero-valent iron. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2020, 15, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolan, N.; Kunhikrishnan, A.; Thangarajan, R.; Kumpiene, J.; Park, J.; Makino, T.; Kirkham, M.B.; Scheckel, K. Remediation of heavy metal(loid)s contaminated soils—To mobilize or to immobilize? J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 266, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Z.; Zhang, J.; Hou, D.; Tsang, D.C.W.; Ok, Y.S.; Alessi, D.S. Synthesis of MgO-coated corncob biochar and its application in lead stabilization in a soil washing residue. Environ. Int. 2019, 122, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Choppala, G.K.; Bolan, N.S.; Chung, J.W.; Chuasavathi, T. Biochar reduces the bioavailability and phytotoxicity of heavy metals. Plant Soil 2011, 348, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; He, Y.; Wu, Y.; Dian, B.; Zhang, J.; Li, T.; Jiang, M. Solidification/stabilization of soil heavy metals by alkaline industrial wastes: A critical review. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 312, 120094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.-S.; Du, Y.-J.; Zhou, A.; Zhang, M.; Li, J.-S.; Zhou, S.-J.; Xia, W.-Y. Geoenvironmental properties of industrially contaminated site soil solidified/stabilized with a sustainable by-product-based binder. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 765, 142778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Feng, P.; Shao, L.; Chen, C.; Liu, X.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, L.; Geng, G. Quantifying the immobilization mechanisms of heavy metals by Calcium Silicate Hydrate (C-S-H): The case of Cu2+. Cem. Concr. Res. 2024, 186, 107695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Zhao, N.; Song, Q.; Ling, H. Alkali synergistic sulfide-modified nZVI activation of persulfate for phenanthrene removal. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 109923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Liu, H.; Anang, E.; Li, C.; Fan, X. Enhanced As(III) sequestration using nanoscale zero-valent iron modified by combination of loading and sulfidation: Characterizations, performance, kinetics and mechanism. Water Sci. Technol. 2021, 83, 2886–2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarekegn, M.M.; Hiruy, A.M.; Dekebo, A.H. Nano zero valent iron (nZVI) particles for the removal of heavy metals (Cd2+, Cu2+ and Pb2+) from aqueous solutions. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 18539–18551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesinger, M.C. Advanced analysis of copper X-ray photoelectron spectra. Surf. Interface Anal. 2017, 49, 1325–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Lan, J.; Dong, Y.; Zhou, M.; Hou, H.; Huang, B.-T. Pollution control performance of solidified nickel-cobalt tailings on site: Bioavailability of heavy metals and microbial response. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 471, 134295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltier, E.; Lelie, D.v.d.; Sparks, D.L. Formation and Stability of Ni–Al Hydroxide Phases in Soils. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Wang, B. Chemical speciation, distribution, and leaching behaviors of heavy metals in alkali-activated converter steel slag-based stabilization/solidification of MSWI FA. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 417, 135209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhongping, Y.; Yao, W.; Xuyong, L.; Shupei, R.; Hui, X.; Jiazhuo, C. The effect of long-term freeze-thaw cycles on the stabilization of lead in compound solidified/stabilized lead-contaminated soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 37413–37423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, K.; Li, X.; Ren, S.; Li, P. The effects of long-term freezing–thawing on the strength properties and the chemical stability of compound solidified/stabilized lead-contaminated soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 38185–38201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Element/% | Na | Mg | Al | Si | S | K | Ca | Fe | Mn | Ti | P | Cr | Others |

| ZVI | 0.75 | 0.35 | 0.81 | 1.94 | 0.23 | 0.02 | 1.45 | 92.39 | 1.40 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.39 |

| BFS | 0.57 | 7.51 | 13.59 | 24.30 | 1.67 | 0.50 | 48.96 | 0.49 | 0.65 | 1.52 | 0.01 | ND | 0.23 |

| SS | 0.28 | 5.62 | 4.01 | 8.35 | 0.59 | 0.25 | 40.88 | 31.23 | 5.76 | 1.34 | 0.61 | 0.31 | 0.77 |

| Oxidation/% | Na2O | MgO | Al2O3 | SiO2 | SO3 | K2O | CaO | Fe2O3 | MnO | TiO2 | P2O5 | Cr2O3 | Others |

| ZVI | 0.80 | 0.46 | 1.20 | 3.23 | 0.44 | 0.02 | 1.53 | 90.36 | 1.27 | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.36 |

| BFS | 0.55 | 8.86 | 17.47 | 33.15 | 2.43 | 0.33 | 35.31 | 0.30 | 0.36 | 1.10 | 0.01 | ND | 0.13 |

| SS | 0.29 | 7.13 | 5.71 | 13.27 | 1.06 | 0.21 | 38.28 | 26.26 | 4.42 | 1.37 | 1.02 | 0.28 | 0.69 |

| Stabilization Materials | Specific Surface Area (m2/g) | Pore Volume(cm3/g) | Pore Size (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HAP | 53.732 | 0.242 | 17.980 |

| BFS | 2.098 | 0.004 | 7.652 |

| SS | 3.452 | 0.016 | 18.280 |

| CaO | 4.060 | 0.023 | 22.998 |

| β-Alumina | 89.494 | 0.116 | 5.172 |

| ZVI | 7.108 | 0.009 | 5.135 |

| 5 Å Molecular Sieve | 91.273 | 0.064 | 2.804 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Luo, R.; Zhao, N.; Jia, Z.; Wu, S.; Chen, X.; Li, Z.; Ju, F.; Luo, Y.; Li, H. Simultaneous Stabilization of Cu/Ni/Pb/As Contaminated Soil by a ZVI-BFS-CaO Composite System. Sustainability 2026, 18, 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010342

Luo R, Zhao N, Jia Z, Wu S, Chen X, Li Z, Ju F, Luo Y, Li H. Simultaneous Stabilization of Cu/Ni/Pb/As Contaminated Soil by a ZVI-BFS-CaO Composite System. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):342. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010342

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuo, Runlai, Nan Zhao, Zhengmiao Jia, Sihan Wu, Xing Chen, Zhongyuan Li, Feng Ju, Yongming Luo, and Hui Li. 2026. "Simultaneous Stabilization of Cu/Ni/Pb/As Contaminated Soil by a ZVI-BFS-CaO Composite System" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010342

APA StyleLuo, R., Zhao, N., Jia, Z., Wu, S., Chen, X., Li, Z., Ju, F., Luo, Y., & Li, H. (2026). Simultaneous Stabilization of Cu/Ni/Pb/As Contaminated Soil by a ZVI-BFS-CaO Composite System. Sustainability, 18(1), 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010342