1. Introduction

Because of its unique properties and stability, cross-linked polyethylene (PEX) is used extensively for manufacture of pressure pipes, for installations of water-, chlorinated water- and steam-distribution systems, thermal equipment in industrial plants and households, and often for underfloor heating. PEX is also widely used to insulate electrical conductors, particularly for voltages ranging from 600 V to 35 kV. This work focuses on the recovery of waste cross-linked polyethylene (PEX) while reducing pollution and increasing recycling of this plastic waste. If the amount of PEX waste is effectively and meaningfully reduced, the production process will be more efficient, which will promote sustainable economic growth for the manufacturer. Sustainable PEX production and PEX waste recovery are interlinked concepts where waste is converted into valuable products, creating a more sustainable and circular economy in this regard.

The broad range of PEX applications inevitably results in significant amounts of production and installation waste that must be properly managed. Unfortunately, current disposal methods rely mainly on incineration and landfilling, which are inefficient and environmentally harmful. According to OECD statistics [

1], in 2019, worldwide, 49% of all plastic waste was landfilled, 19% was incinerated, 9% was recycled, and 22% was disposed of in an uncontrolled manner (simply thrown away). In EU member states, 37% of plastics were landfilled, 44% were incinerated, 14% were recycled, and 5% were disposed of in an uncontrolled manner. In non-OECD countries, the situation regarding uncontrolled disposal of plastic waste is even worse. Evidently, in most countries, management of waste plastic leads to significant reserves that provide an opportunity for the deployment of pyrolysis, because it reduces waste, minimizes environmental impact, and creates new economic opportunities.

PEX waste continues to be considerable. This is due to its advantages and wide range of applications. Industries in which PEX is used and from which its waste is derived are plumbing (flexible and rigid piping systems in homes and industries for hot and cold water), electrical insulation (widely used for insulating low, medium, and high voltage electrical cables), medical implants (orthopedic implants such as hip and knee replacements to reduce wear and tear), transportation (chemical transport, sewage pipes, and offshore oil applications), and consumer goods (baby play mats and protective foam padding). The key growth drivers are construction and infrastructure (increased demand for PEX pipes, radiant heating and cooling systems due to their flexibility, durability, and corrosion resistance); energy sector (the growing need for high-performance electrical cable insulation for efficient and safe energy transmission); new materials as an alternative to traditional materials like copper and PVC. Such widespread use results not only in high production, but also in large amounts of waste.

As described below, waste PEX can be effectively recycled by converting it into high-value products such as industrial oils, paraffin, and energy gas, which is possible using catalytic pyrolysis technology at temperatures up to 450 °C, which is not a particularly high temperature. It should be emphasized that waste PEX is not technological, which means that it cannot be directly returned to the production process because the quality requirements for PEX products are too high and could not be met if waste PEX were reused as a starting material. It must therefore be processed, preferably into products with high utility value.

So far, this waste material has been recommended to be practically processed using mechanical methods [

2], extrusion [

3,

4], chemical recycling [

5,

6], and forming after preheating [

7]. A major disadvantage of mechanical methods is their low efficiency. The practical application of the product is also unclear. In the case of PEX, this is significant because of the high demands on the product properties. The disadvantages of extrusion include the high acquisition and maintenance costs of equipment and the reduction in the density of the resulting product in comparison with the starting material. This can cause problems in the practical use of the products. An obvious drawback of chemical recycling is the use of methods that are difficult to implement in practice, for example, plasma degradation or reactions with supercritical water (a dense, highly aggressive gas), which consume large quantities of energy. The technical design of equipment is unclear and the use of these methods can be economically very risky. It is thus appropriate to consider a way of treating the PEX waste that is realistic and provides products with feasible applications. Finding such a processing method is difficult, because PEX is a very stable material. Pyrolysis complies with these criteria by converting a stable polymer into liquid and gaseous products suitable for use as fuels or chemical feedstocks, at relatively moderate temperatures and with the possibility of catalytic enhancement [

8].

Pyrolysis of polyolefin-based plastics, including PEX, produces hydrocarbon oils, waxes, BTX aromatics (benzene, toluene, xylene), and light aliphatic hydrocarbons. The product distribution depends on process conditions, particularly temperature. At 400–500 °C, the process mainly yields oils, waxes, and high-calorific gas, whereas above 700 °C, gaseous hydrocarbons (C

1–C

4) and BTX aromatics dominate, serving as feedstocks for numerous chemical syntheses [

8,

9]. Conventional thermal pyrolysis of polyethylene typically occurs at 500–700 °C without catalysts, producing a broad range of hydrocarbons. However, this approach is energy-intensive and offers limited control over product composition, restricting their direct use as fuels or chemical intermediates [

10]. The yield of light hydrocarbons and liquid oils increases with rising temperature (>600 °C), while the paraffins are mainly produced at a lower temperature around 400 °C.

In contrast, catalytic pyrolysis enables lower operating temperatures (typically 400–500 °C) and improved product selectivity. Acidic catalysts (e.g., zeolites HZSM-5, HUSY, FCC catalysts, metal oxides such as Al

2O

3, Fe

2O

3) enhance chain scission efficiency, promoting the formation of shorter hydrocarbons, aromatics, or hydrogen [

11]. Catalysts also increase the yield and quality of the liquid fraction. Pyrolysis oils contain higher concentrations of saturated and unsaturated hydrocarbons (C

5–C

24), and their physical properties (density, heating value) approach those of commercial diesel. Furthermore, catalysts reduce undesirable by-products such as carbonaceous residues and allow better control over aromatization and isomerization processes [

12,

13].

The aim of this study is to suggest a method for processing waste PEX through catalytic pyrolysis under precisely defined conditions using hematite (α-Fe

2O

3) as a catalyst. Hematite (α-Fe

2O

3) is a versatile and widely studied catalyst with applications in various fields, including combustion, environmental remediation, and energy conversion. Its catalytic properties result from its ability to facilitate chemical reactions, often by providing active sites for reactants to interact or by influencing reaction pathways [

11,

14,

15]. The large-scale pyrolysis process is designed to achieve a high yield of oil and energy-rich gas with high calorific value. At the same time, the efficiency of the process and its potential to reduce environmental pollution and increase PEX waste recycling are evaluated. The implementation of this technology supports the concept of a circular economy, where waste is converted into valuable products, thereby enhancing production sustainability and resource efficiency.

The novelty consists in the scale of the process. Typically, laboratory tests are performed with samples weighing in the range of milligrams or grams [

16,

17,

18]. The aim of our research was to verify the feasibility of large-scale PEX processing with several tens of kilograms of waste material, yielding a main product—oil of almost 73 wt.% at a process efficiency of 70%.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The processed waste consisted of colored cross-linked polyethylene (PEX) material in the form of small ovals and their parts, having an outer dimension of approx. 18.4–25.0 mm and a thickness ranging from 0.6 to 2.2 mm, which came mainly from the production of pressure pipes, hot water pipes, and cable insulation. The modification of input material on a large scale is difficult—it involves tens of kilograms—therefore, the material was pyrolyzed in its original state (as received). The waste contained very little water and ash, and had a high percentage of combustible matter. Proximate and organic elemental analysis and the higher and lower heating value of the processed material were conducted according to standards [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25] and are shown in

Table 1. The lower heating value (LHV) was calculated from the equation given in ČSN ISO 1928 [

25]. At the same time, these standards were used to characterize oil and solid carbonaceous residue (SCR). The oxygen content in both the input raw material and the products (oil and solid carbonaceous residue) was determined by calculation to 100%.

The hematite catalyst was applied in the form of a fine dispersion of α-Fe

2O

3 (Merck Life Science, Ltd., Darmstadt, Germany) particle size ≤ 110 nm (use based on [

26]).

2.2. Methods

Thirty-eight kilograms of waste PEX in oval forms with 2 wt.% (760 g) of catalysts was pyrolyzed in a fixed bed in a power-controlled electric furnace. (Note: with 2 wt.% of α-Fe

2O

3, the content of low hydrocarbons C

6–C

9 increased to 36 wt.% (see below) compared to 1 wt.%; therefore, 2 wt.% of catalyst was chosen for the large-scale experiment.) The furnace was preheated to a wall temperature of 114 °C, after which the waste PEX feedstock was introduced into the reactor. It was uniformly sprinkled throughout the entire volume with a fine dispersion of the catalyst. The mixture was then homogenized using an operational kneader. Subsequently, the batch was heated from 56 °C to 435 °C at a rate of 4 K min

−1 in the center of reactor and simultaneously 5.4 K min

−1 on the reactor wall. A heating rate of 5 K min

−1 was tested on a laboratory scale, at which a sufficient amount of oil was obtained, and we used this finding as a feasible parameter to use on a large scale [

18]. The 435 °C temperature was maintained for several hours until gas evolution was terminated. During pyrolysis, the released volatile products (raw gas) were cooled in a heat exchanger by a countercurrent flow of circulating cold water (6–8 °C) with flow rate of 160 L min

−1. The heat exchanger had a heat transfer area of 20 m

2 and thus provided sufficient cooling of the raw gas and produced oil. In this way, the pyrolysis oil and pyrolysis gas were separated and the outgoing gas was sampled and then burned using a gas flare (

Figure 1).

This study assumes that fillers do not interfere with the pyrolysis process.

The pyrolysis conditions were selected based on the laboratory experiments summarized in

Section 4, see below. The realistic heating rate of waste plastic mixtures under operating conditions is approximately 4 K min

−1. The final temperature should not exceed 500 °C so that heat consumption is not too high. The laboratory experiments were therefore carried out under conditions stated below (see

Section 4). Under operational conditions, a heating rate of 4 K min

−1 was achieved in the center of the reactor and simultaneously 5.4 K min

−1 on the reactor wall, with a final temperature of 435 °C, which was maintained for several hours until gas evolution was terminated.

The components of main product, the oil obtained, were determined on an HP 6890 gas chromatograph (Hewlett-Packard, Buffalo, NY, USA) with MSD 5975 mass detector (GC-MS) operating in an inert helium atmosphere with a flow rate of 93 cm3 min−1. A 30 m long DB XLB capillary column with a diameter of 0.25 mm was used. The initial column temperature was 50 °C; this temperature was maintained for the first minute. Heating was then controlled by a program at a rate of 10 K min−1 to a final temperature of 300 °C. The column was maintained at the final temperature for 6 min. Calibration curves based on the digital response of the instrument were used to determine the oil components. MSD ChemStation Data Analysis software, version D.01.00 was used to evaluate the GC-MS spectra.

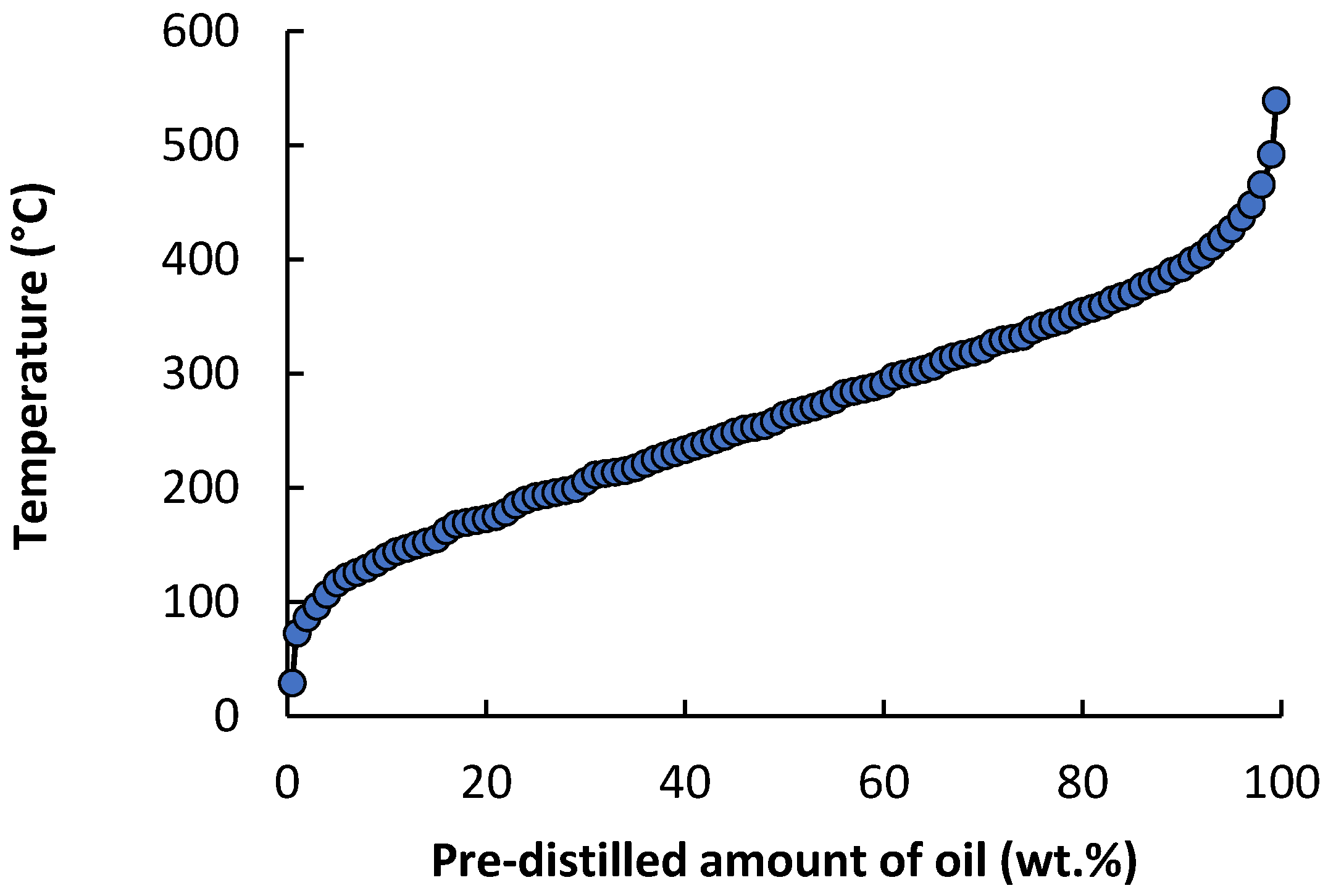

The distillation curve of the oil was determined by simulated distillation according to ASTM D2887 method [

27]. A Trace GC Ultra instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Milano, Italy) equipped with cryogenic cooling of the chromatographic oven, an automatic sample dispenser, and an FID detector was used to evaluate the distillation curve of the oil. A 1 µL sample was injected onto a Varian WCOT Ultimetal column (10 m × 0.53 mm i.d.; film thickness of 0.17 μm), which was placed in an oven heated linearly to 410 °C at a rate of 15 K min

−1. The helium carrier gas flow rate (5 mL min

−1) was constant throughout the heating period. The results obtained were evaluated using SimDisChrom software version 2.2.

The moisture content in the oil was analyzed using the Karl Fischer automatic titration method. The measurement was performed at least five times and the results were processed using specialized software connected to a volumetric titrator (Metrohm, Prague, Czech Republic).

The dynamic viscosity of the oils obtained was measured with a Haake Viscotester iQ rotational rheometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with a double-gap cylindrical geometry. After the temperature was stabilized at 20 or 40 °C, the measurement was performed at the shear rate of 1400 s

−1 and repeated three times. The density of the oils was determined using a Densito electronic densimeter (Mettler Toledo, Prague, Czech Republic) and the results were used to calculate kinematic viscosity. Kinematic viscosity (

) was calculated from dynamic viscosity (

) and oil density (ρ) using Equation (1).

Gas samples collected in 500 mL Tedlar bags were immediately analyzed using gas chromatography with both FID and TCD on two Agilent Technologies 6890N chromatographs (Agilent Technologies, Buffalo, NY, USA) with three 30 m × 0.32 mm capillary columns. The analysis of O2, N2, and CO was performed on an HP-MOLSIV capillary column (40 °C) with carrier gas He (5 cm3 min−1) using TCD; further, analysis of CH4 and C2–C5 hydrocarbons on a GS-Gaspro (60 °C) with carrier gas N2 (20 cm3 min−1) using FID, CO2 on a GS-Gaspro (40 °C) with carrier gas He (5 cm3 min−1) using TCD, and H2 on an HP-5 (40 °C) with carrier gas N2 (7 cm3 min−1) using TCD were performed.

Inorganic elements in solid carbonaceous residue were determined using a non-destructive X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analyzer (Spectro IQ, Kleve, Germany). The instrument has the following parameters: He atmosphere; palladium target material; target angle from the central ray, −90°; focal point, a 1 mm × 1 mm square; maximum anode dissipation of 50 W; and 10 cfm forced-air cooling. Sample preparation involved the pressed-pellet method, where 4.0 g of material with a particle size of 15–20 µm was mixed for 10 min with 0.9 g of Hoechst wax (Bedburg-Hau, Germany) as a binding additive. The mixture was then pressed at 80 kN. X-LabPro software version 5.1 automatically converted the elemental results.

To evaluate the efficiency of the conversion process, the efficiency of low-temperature pyrolysis was determined based on a comprehensive mass and energy balance. The calculation considered the energy of useful products obtained on one side and the energy of the input feedstock together with losses on the other (see

Section 3.1). Efficiency of the process (EPi, %) was then expressed as the ratio of the lower or higher heating value (LHV or HHV) of the useful products (oil and gas) to the LHV or HHV of the input waste PEX, including the heat required to raise the PEX to the decomposition temperature, ~420 °C. This heat demand (Q) was calculated using the specific heat capacity of PEX (c = 1.9 kJ kg

−1 K

−1) and the LHV or HHV of solid carbonaceous residue (SCR). SCR as a product with no or negligible utility value was considered as a loss. Using LHV, the efficiency EPLHV was then expressed by Equations (2) and (3):

using HHV as

No generative artificial intelligence was used in this paper.

4. Discussion

The reason for choosing α-Fe

2O

3 was that this catalyst is relatively inexpensive and readily available, according to laboratory-scale tests, and also quite effective. We tested various catalysts with different results (

Table 5). PEX can be thermally processed without a catalyst, but the resulting oil does not contain the highly desirable liquid C

5–C

9 hydrocarbons. Very good results were achieved with ruthenium, where the addition of 1 wt.% Ru led to a significant yield of these lower hydrocarbons (39 wt.% in oil,

Table 5), an overall high yield of liquid hydrocarbons (92 wt.% in oil,

Table 5), and a low yield of the less desirable C

18–C

35 solid hydrocarbons (8 wt.% in oil,

Table 5). However, a significant disadvantage is the high price of ruthenium. Good results were also achieved with FeTiO

3 (lower hydrocarbons C

6–C

9, 15 wt.% in oil,

Table 5) and overall high yield of liquid hydrocarbons of 82 wt.% in oil (

Table 5), which was effective (yield of oil 92 wt.%,

Table 5) and has the great advantage of being very inexpensive, as it is a waste product from titanium-white production. Waste PEX can therefore be processed together with this waste into products that are in high demand. The disadvantage is that it is not yet established as a catalyst. Furthermore, the well known and widely used FCC (fluid catalytic cracking catalyst) was tested. To achieve the required degree of cleavage in the PEX rigid structure, it was necessary to use 10 wt.% of catalyst. Unfortunately, its use led to a high proportion of undesirable hydrocarbons >C

35, which would probably cause difficulties in its practical use. Due to the high consumption and lower quality of oil, it was therefore no longer considered a suitable catalyst. Finally, α-Fe

2O

3 was tested. Laboratory pyrolysis with this catalyst gave a high oil yield and a good composition for practical use (

Table 5). However, an addition of 2 wt.% and a very fine grain size were required. Due to its availability and low cost, this catalyst was chosen for the large-scale test. The results of large-scale pyrolysis differed from the laboratory tests, indicating a lower oil yield and higher SCR yield. The composition of the obtained oil, however, was very favorable, as

Table 5 shows. For the reasons given above, further large-scale tests will focus on the use of the FeTiO

3 catalyst.

As mentioned, the process efficiency of 70% is assumed acceptable. It can probably be improved by an important process parameter, the residence time of volatile products in the reactor, which has a significant effect on the oil composition (the longer the residence time, the higher the proportion of liquid hydrocarbons compared to solid ones). In many cases, this parameter is difficult to quantify. In this case, the effect of residence time was tested in a comparative laboratory experiment, where 20 g of waste PEX with catalyst was heated at the specified heating rate (4 K min−1) to the final temperature of 470 °C (stationary conditions) and then again in the same way, but with a nitrogen flow rate of 100 cm3 min−1 (dynamic conditions). As a result, the residence time of volatiles in the pyrolysis zone with flowing nitrogen was much shorter than under stationary conditions. The content of liquid and solid hydrocarbons in the obtained oil was then compared. When pyrolyzed under stationary conditions, the oil (100%) contained a high proportion of liquid hydrocarbons, 92%, and few solid hydrocarbons (8%). Under dynamic conditions, the opposite was true, with a liquid hydrocarbon content of 11% and a solid hydrocarbon content of 89%, because the residence time of volatile products in the pyrolysis zone was too short and the cleavage of the rigid PEX structure was limited. This demonstrated that the large-scale pyrolysis conditions were adequately chosen, as high or at least acceptable yields of liquid aliphatic hydrocarbons were achieved. Further, this means that by reducing the residence time, higher process efficiency can be achieved because, as follows from above, with longer residence time, the oil has a high content of liquid hydrocarbons and few solid ones, but with shorter residence time this ratio changes in favor of solid hydrocarbons. This can be ensured by a lower heating rate of PEX material in the reactor. Reducing the heating rate from 4 to 3 K min−1 is quite feasible and can be considered as a further research task. Such a reduction would not significantly increase the total pyrolysis time or processing costs.

Another task is to reduce the ash content in the resulting SCR and also to reduce the iron content, which is more than 4%, practically 4.5% (

Table 4). In the past, several methods have been developed for coal washing, an industrial method in which coal is mixed with water and chemicals to separate impurities based on different densities. It is a process that removes impurities from coal by crushing and screening it, and then uses techniques such as gravity separation or froth flotation to separate the cleaner coal from heavier materials such as rocks, ash, and sulfur. Magnetic separation methods have also been developed, which use powerful magnets to remove iron impurities from coal. All of these methods can be used for mineral processing of carbonaceous materials, including SCR. These methods are both standardized and still under development [

42,

43], which is a positive fact for SCR cleaning. It is very likely that magnetic separation using strong and affordable NdFeB magnets would significantly reduce both Fe and ash content in SCR [

44].

5. Conclusions

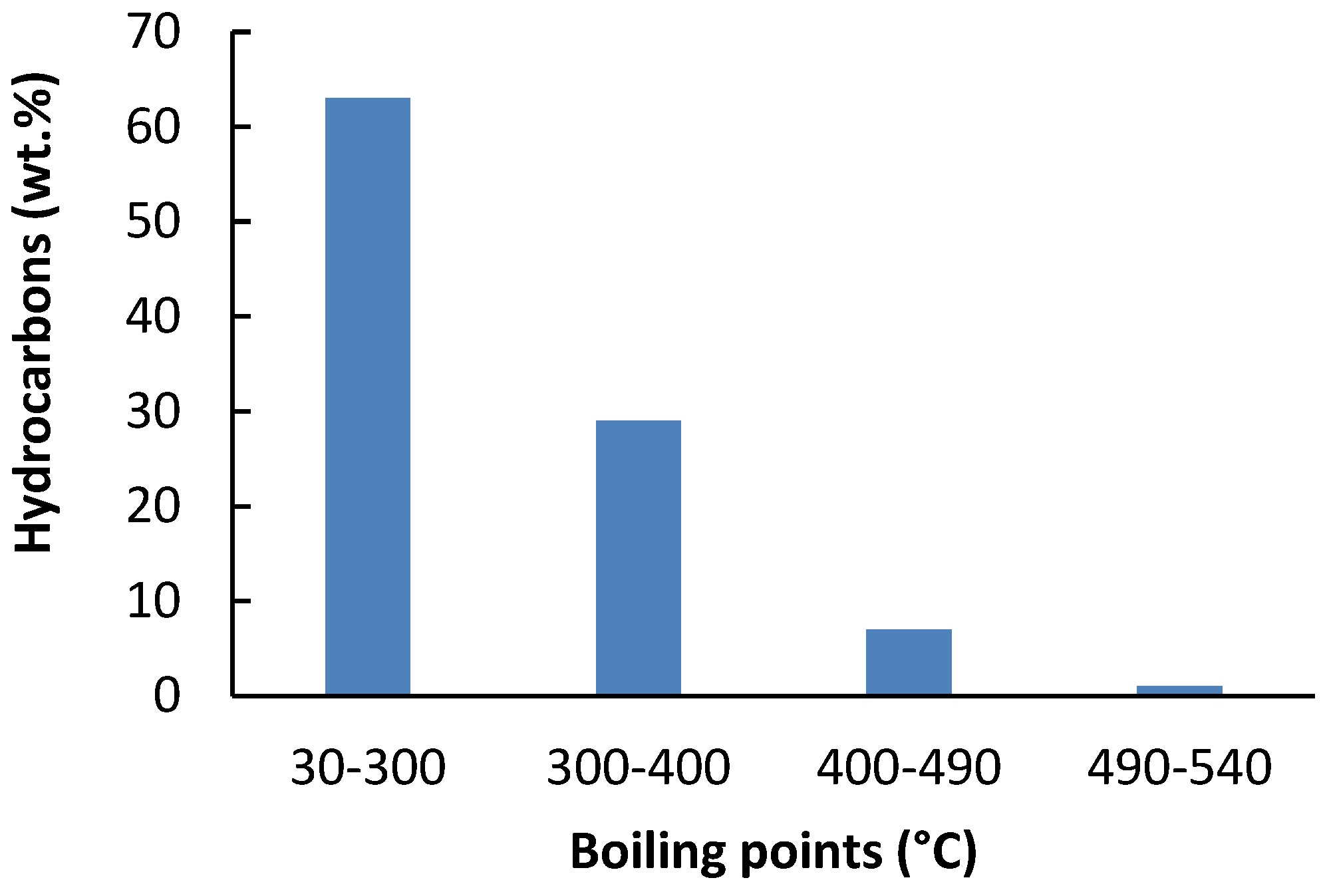

It was demonstrated that waste PEX can be efficiently processed by Fe2O3-catalyzed slow pyrolysis on a large scale, with achieving an overall process efficiency of 70%, which is acceptable given the non-technological character of this waste. The selected process conditions (temperature, heating rate, catalyst amount) used effectively converted PEX predominantly into liquid products with a high oil yield of almost 73 wt.%. The resulting oil consisted mainly of liquid hydrocarbons up to C17 (78 wt.%) together with nearly 20 wt.% of solid hydrocarbons C18–C28, confirming its broad applicability across various industries, such as petrochemicals, fuel manufacturing, and chemical production, and potentially as a feedstock for industrial lubricants and oils. Its very low sulfur content (0.03 wt.%) further supports its suitability as a low-emission fuel. In addition to the oil, gaseous and solid carbonaceous residues were produced in non-negligible amounts of 11.8 wt.% and 15.5 wt.%, respectively. The gas exhibited a high heating value of 51.7 MJ·m−3, and can be primarily used to for heating the pyrolysis unit, thereby reducing its operating costs, or potentially used in a gas engine under favorable conditions. The solid carbonaceous residues, however, appear more challenging due to their elevated sulfur content (0.6 wt.%). Their upgrading is likely feasible through conventional or newly developed mineral-removal methods.

In the subsequent research phase, the experimental program will be systematically enhanced to evaluated the influence of different catalyst additions (0.5 wt.% and 1 wt.%) on the yield, distribution, and chemical composition of the individual products. This approach will allow more reliable support for the presented results, refine knowledge of the catalytic mechanism, and further assess the efficiency and reproducibility of the overall pyrolysis process.