2.1. Rural Community Resilience

The concept of “resilience” originated in physics and mathematics, referring to a system’s capacity to withstand external disturbances. Since then, its conceptual scope has broadened considerably across multiple disciplines. In contemporary research, resilience commonly refers to the capacity of a system or community to anticipate, absorb, adapt to, and recover from both acute shocks and chronic stresses [

18,

19,

20]. Given the multifaceted nature of rural communities, the concept encompasses multiple levels—from the community as a whole to households and individual residents [

21,

22]. This inherent complexity is reflected in the diverse conceptualizations of “rural community resilience” found throughout the literature. Some studies define resilience as a community’s ability to maintain structural and functional stability when confronted with disturbances [

23]. Other scholars emphasize its adaptive and dynamic nature, defining resilience as the community’s capacity to withstand disturbances while pursuing sustainable development [

24]. Still others highlight human agency, underscoring the proactive roles of individuals and groups in coping with change [

25]. Despite these differing emphases, most definitions converge on the view that resilience reflects a community’s capacity to cope with both internal and external disturbances [

17,

26,

27]. This capacity can generally be summarized into three dimensions: (1) resistance, the ability to maintain basic social structure and functions and avoid collapse during a disturbance; (2) recovery, the ability to restore social functions to pre-shock or acceptable levels after a disturbance; and (3) adaptation, the ability to adjust and reorganize in anticipation of or in response to future challenges and changing conditions [

28]. Rural community resilience is multidimensional and closely linked to the resilience of social, economic, built, and ecological systems [

29]. Building on this foundation, Norris proposed a widely cited framework, identifying four interrelated dimensions of resilience: social capital, economic development, information and communication, and community competence [

19].

International research likewise highlights that rural resilience depends strongly on internal social processes. Steiner and Atterton demonstrate that local social networks can enhance a community’s capacity for self-organization under long-term pressures [

30]. Skerratt finds that community autonomy plays a critical role in sustaining rural communities’ adaptive capacity [

31]. Wilson further argues that social capital and local agency shape the pathways through which communities respond to external challenges [

22]. Together, these insights provide valuable comparative perspectives for understanding rural resilience in China.

Building on this foundation, the above review indicates that existing research offers a solid, multidimensional basis for understanding rural resilience. However, to address the gap regarding how individual psychological processes shape collective resilience [

17], this study adopts a micro-level analytical perspective. The study seeks to translate the abstract concept of resilience into indicators that residents can directly perceive and evaluate. Drawing on the social-capital dimension of resilience frameworks [

32,

33], this study focuses on internalized psychological and social factors—namely cultural identity and place attachment—that are vital for fostering community resilience. The overarching goal is to clarify how these psychological factors contribute to the construction of community resilience.

2.2. Rural Public Spaces and Environmental Perception

Rural public spaces, as key material environments that evoke the psychological and social dynamics discussed above, play a particularly significant role in contemporary China. With the advancement of urbanization and the deepening of the rural revitalization strategy, both the structural forms of rural public spaces and the socio-cultural systems they embody are undergoing profound and complex transformations [

34].

As essential sites of daily life—characterized by openness and accessibility [

33]—rural public spaces fulfill multiple social, functional, and cultural roles, including residence, circulation, work, and social interaction [

35]. In rural contexts, typical public spaces—such as ancestral halls, village squares, and open grounds beneath ancient trees—extend far beyond their functional purposes. These spaces often serve as cultural domains that preserve local memory, strengthen social interaction, and anchor collective identity.

In the Chinese rural context, these socio-spatial characteristics take on an even more distinctive expression. Rural communities have long functioned as “acquaintance societies,” where everyday interactions are embedded in long-standing kinship and neighborhood ties. Accordingly, public spaces such as ancestral halls or clan squares simultaneously serve as ritual venues, community deliberation sites, and repositories of customary norms [

36]. This tight integration of social relations, cultural practices, and spatial settings shapes residents’ perceptions and emotional connections to these environments, forming attachment mechanisms that differ markedly from those found in urban or Western contexts.

Building on this socio-cultural foundation, rural public spaces become crucial arenas through which environmental perception is transformed into cultural identity and place-based emotional bonds.

Figure 1 illustrates the key physical elements that characterize these spaces. In essence, these spaces serve as cultural domains and emotional hubs that foster social relationships, preserve collective memory, transmit local knowledge, and reinforce community sentiments [

36,

37]. Due to their multifunctional nature, high-quality public spaces significantly enhance residents’ physical and psychological well-being, strengthen social cohesion, and improve overall quality of life [

38].

Through these functions, public spaces constitute an essential material basis for rural community resilience. To better understand these processes, this study introduces the concept of environmental perception. Rooted in cognitive behaviors such as the recollection of spatial images [

35], environmental perception serves as a crucial bridge between objective physical settings and residents’ subjective experiences.

Accordingly, this study divides residents’ environmental perception of public spaces into three dimensions:

- (1)

Outdoor spatial elements, referring to functionality, accessibility, safety, aesthetics, and the physical quality of environments such as streets and courtyards;

- (2)

Supporting facilities, encompassing the completeness and satisfaction of commercial, recreational, landscape, and service amenities;

- (3)

Social elements, involving residents’ experiences with healthcare, culture, public services, transportation convenience, and overall sense of security [

39].

Together, these dimensions capture residents’ holistic evaluations of public spaces across physical, functional, and social dimensions. While individual dimensions may appear conventional, their collective perception acts as the crucial initial input into a unique psychological pathway within rural China, distinguishing it from general satisfaction models. Environmental perception is closely linked to residents’ satisfaction and well-being. Numerous studies show that high-quality spatial environments elicit positive psychological and emotional responses, which in turn enhance physical and mental health and foster more frequent, higher-quality social interactions [

40]. For example, Tan Lingqian et al. found that stronger perceptions of natural features in neighborhood green spaces are positively associated with residents’ subjective satisfaction and happiness [

41]. Moreover, environmental perception is inherently multidimensional and integrative [

42], encompassing not only visual contact with nature but also the overall experiences of spatial accessibility, facility completeness, and social atmosphere. These multidimensional perceptions collectively shape residents’ evaluations of public spaces, stimulate psychological and social dynamics, and ultimately enhance community resilience.

2.3. The Mediating Role of Place Attachment and Cultural Identity

Rural public spaces support community resilience both directly and indirectly through socio-psychological mechanisms such as cultural identity and place attachment. Place attachment (PA) refers to the emotional and cognitive bonds that connect individuals to specific places. Its theoretical roots lie in Yi-Fu Tuan’s Topophilia and Proshansky’s Place Identity, which emphasize emotional bonding and self-identification in human–environment relationships [

43,

44]. However, classical frameworks often overlook collective dimensions and the role of public spaces in shaping shared emotional connections, and they typically conceptualize attachment as static rather than dynamic.

Recent anthropological studies highlight the social and experiential dimensions of place, showing how shared practices and lived experiences shape collective emotional bonds. Feld and Basso demonstrate that a “sense of place” emerges through culturally embedded practices and storytelling [

45]. Pink notes that everyday routines and embodied interactions continuously reconstruct place attachments [

46], while Riley argues that rural identities are shaped by intergenerational memory and locally grounded narratives [

47]. These insights extend classical frameworks by emphasizing that attachment is culturally situated, dynamic, and socially constructed.

Building on these perspectives, later scholars developed integrative frameworks that capture the complexity of place attachment. Altman and Low’s person–place model emphasizes functional, social, and symbolic interactions, suggesting that attachment emerges from both individual needs and community-constructed meanings [

48]. Scannell and Gifford’s person–process–place (PPP) model conceptualizes attachment as a systemic process linking people, physical settings, and psychological mechanisms [

49]. Lewicka further underscores its relational and dynamic nature, showing how social interaction, memory-making, and spatial practice continuously reshape attachment [

50,

51]. Multidimensional models by Raymond et al. and Kyle and Vaske [

52] introduce factors such as social bonding and nature connectedness, offering more comprehensive empirical approaches.

Drawing on these developments, this study adopts the two-dimensional framework of Williams et al. [

53], which balances emotional and functional aspects of attachment. Place identity and place dependence are used as complementary dimensions to analyze residents’ affective and functional connections to rural public spaces, and to examine how spatial experiences transform into psychological attachment and ultimately contribute to community resilience.

Place identity refers to the emotional bonds and symbolic meanings individuals attribute to a place—such as viewing a village as “home” or recognizing public spaces as repositories of personal memories and collective identity. It forms dynamically through social interaction and memory construction, encompassing both environmental influences and the internalization of local culture [

54,

55]. Place dependence reflects functional ties [

56], indicating how well spaces meet residents’ needs for leisure, social interaction, and daily use, and evolves through accumulated spatial experiences [

57,

58].

Cultural identity refers to individuals’ psychological sense of belonging to the symbols, values, and practices of a cultural group [

59]. According to social identity theory [

60], this identification stems from basic needs for self-esteem and belonging. Cultural identity develops through socialization, as participation in collective practices leads individuals to internalize cultural norms and traditions [

61]. Fei Xiaotong’s notion of “cultural consciousness” localizes this idea by emphasizing the unity of rational understanding and emotional recognition of cultural values [

62].

More recent perspectives—such as Hall’s concept of identity fluidity and Jenkins’s social-constructionist view—stress that cultural identity is dynamic and continually reshaped through interaction and differentiation [

63,

64].

In rural settings, cultural identity is reflected in residents’ cognitive understanding, emotional attachment, and behavioral orientations toward local traditions and historical culture. Following established research frameworks [

65], it can be analyzed across three dimensions: (1) cognitive understanding of local traditions through interaction; (2) emotional attachment and pride in local culture; and (3) behavioral participation and willingness to transmit local cultural practices.

Within this framework, cultural identity serves as a catalyst for the formation and strengthening of place attachment. From the perspective of identity theory, individuals have an inherent motivation to maintain self-continuity and self-esteem, as well as to seek belonging and uniqueness. Rural public spaces (such as ancestral halls and opera stages) act as primary carriers of local cultural symbols [

66]. Through participation in cultural activities such as rituals and festivals, residents internalize external cultural norms and collective identity into their self-concept.

Identity Process Theory suggests that cultural identity precedes emotional and functional bonds to place, as individuals anchor their self-concept in cultural categories before forming place-based attachments [

67]. Similarly, Social Identity Theory posits that identification with a group provides the cognitive basis for subsequent emotional and behavioral relations with physical settings [

68]. Cultural geography and anthropology further show that rural public spaces operate as “symbolic spaces” where collective memory and cultural meaning are spatially embodied [

69,

70]. Once individuals identify with a cultural community, its associated physical environments become symbols of belonging, thereby reinforcing place attachment. These symbolic spaces also strengthen functional connections (place dependence) [

71], and empirical studies demonstrate that cultural identity enhances place dependence by enriching perceived place meaning and functional fit [

72,

73].

Thus, cultural identification triggers a sequential mechanism—identity consolidation → emotional bonding → functional reliance—that forms the core of the cultural-identity-to-place-attachment pathway.

In related research, place attachment and cultural identity are commonly examined as mediating variables [

74]. In this study, their mediating roles unfold as follows: positive environmental perceptions strengthen cultural identity, which in turn enhances place attachment, forming a chain-mediation process. Cultural identity reinforces place attachment, consistent with findings that identity-based meanings are internalized before being expressed as emotional attachment to place [

50,

75,

76]. Strengthened identity further promotes social cohesion, neighborly support, and participation in collective activities [

77]. These pro-social behaviors—driven by shared identity and emotional connection—form a resilient foundation that enables communities to organize responses, maintain social functions, and recover effectively from external shocks [

78].

2.4. Theoretical Framework and Research Hypotheses

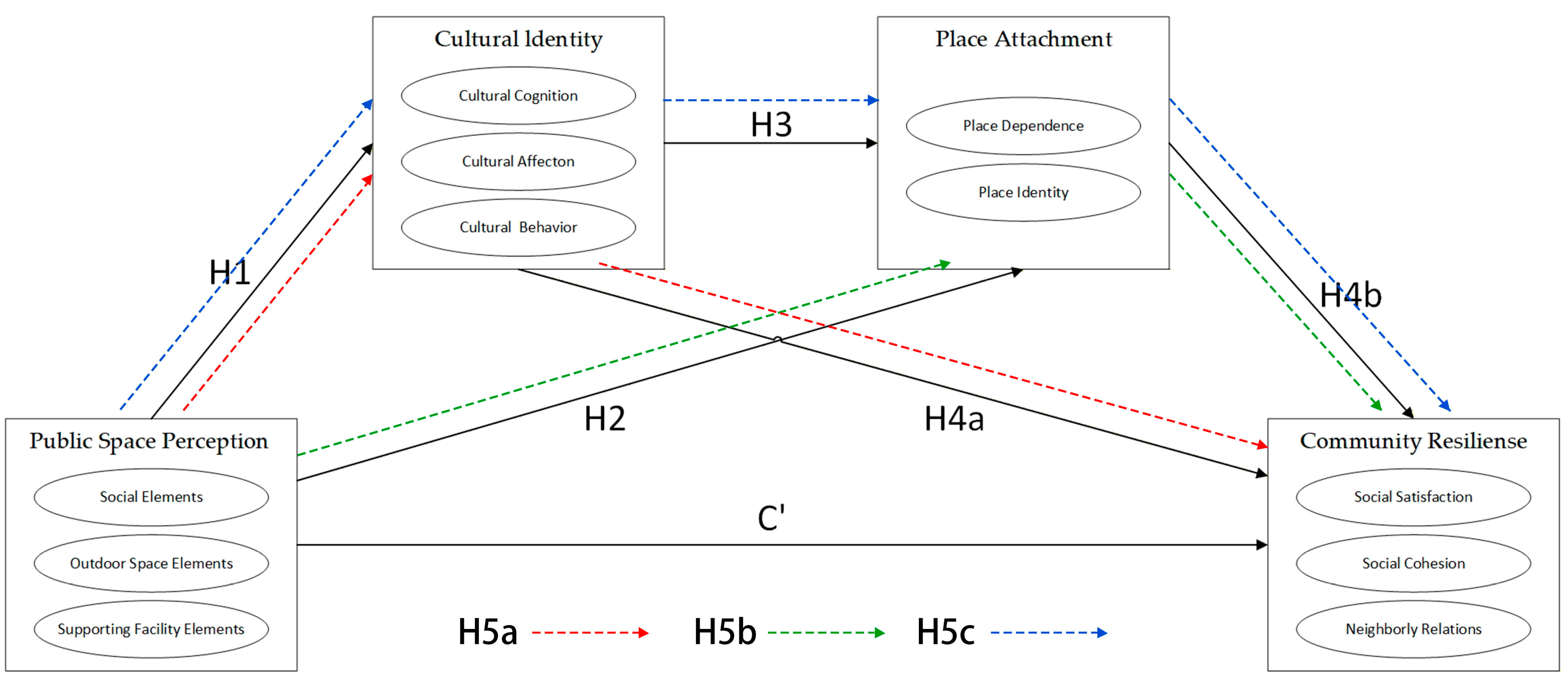

Building upon the preceding discussion, this study develops a conceptual framework of “environmental perception → psychological identity → community resilience” (

Figure 2). The model identifies environmental perception of rural public spaces as the independent variable, residents’ cultural identity and place attachment as the core mediating variables, and community resilience as the dependent variable.

Accordingly, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1. Environmental Perception of Public Spaces positively influences cultural identity.

H2. Environmental Perception of Public Spaces positively influences place attachment.

H3. Cultural identity has a significant positive effect on place attachment.

H4a. Residents’ cultural identity has a significant positive effect on community resilience.

H4b. Residents’ place attachment has a significant positive effect on community resilience.

H5a. Cultural identity mediates the relationship between environmental perception of rural public spaces and community resilience.

H5b. Place attachment mediates the relationship between environmental perception of rural public spaces and community resilience.

H5c. Cultural identity and place attachment have a chain mediating effect between environmental perception of rural public spaces and community resilience.