Unpacking Key Systems Towards a Sustainable Education Ecosystem

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Can systems thinking be employed to represent dynamic interdependence within the education ecosystem?

- What principal characteristics and relationships define the identified education-related systems from an extensive literature analysis?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Education as a Dynamic Ecosystem

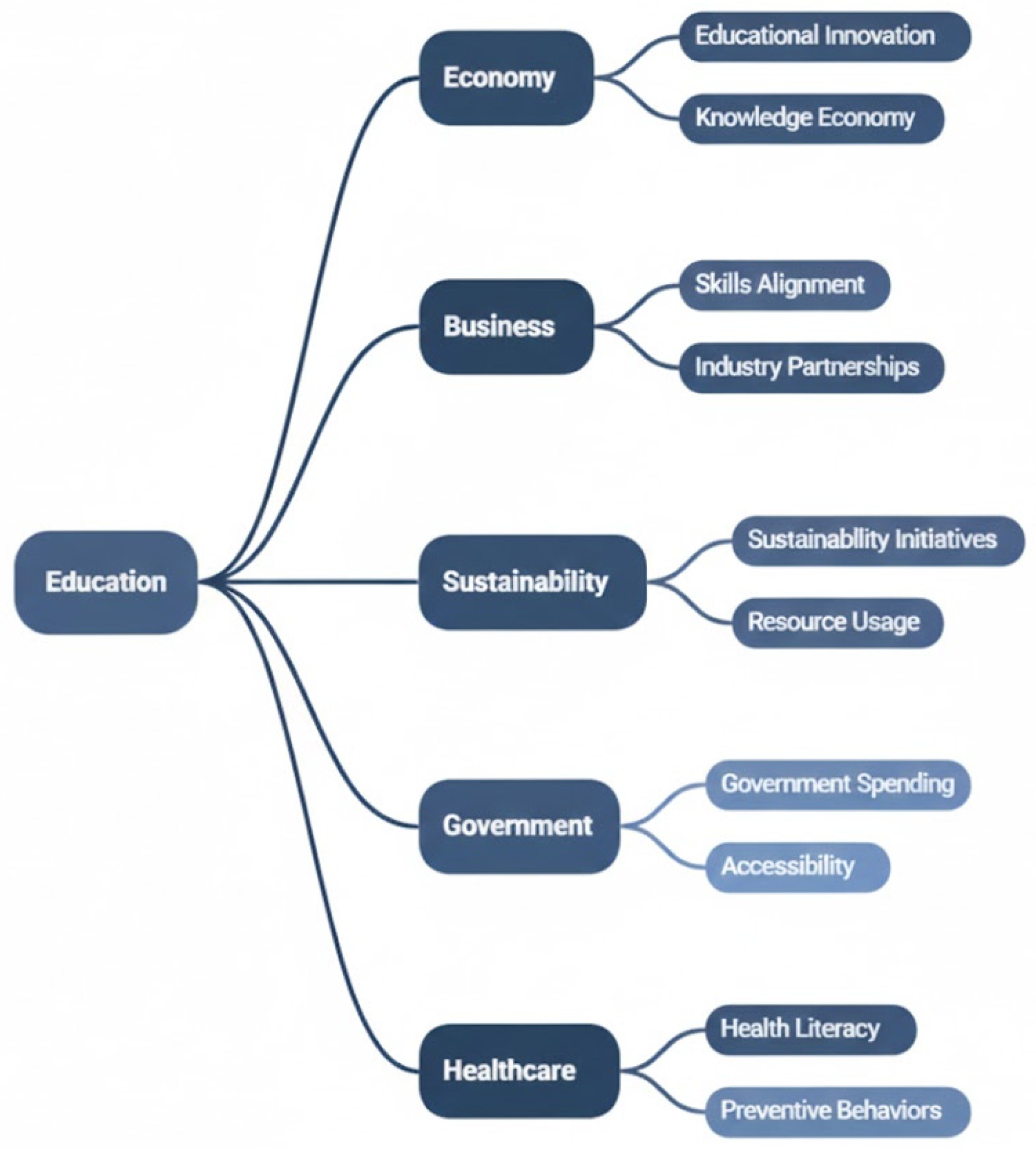

2.2. Education Systems and External Factors

2.3. Methodological Approaches for Understanding the Education Ecosystem

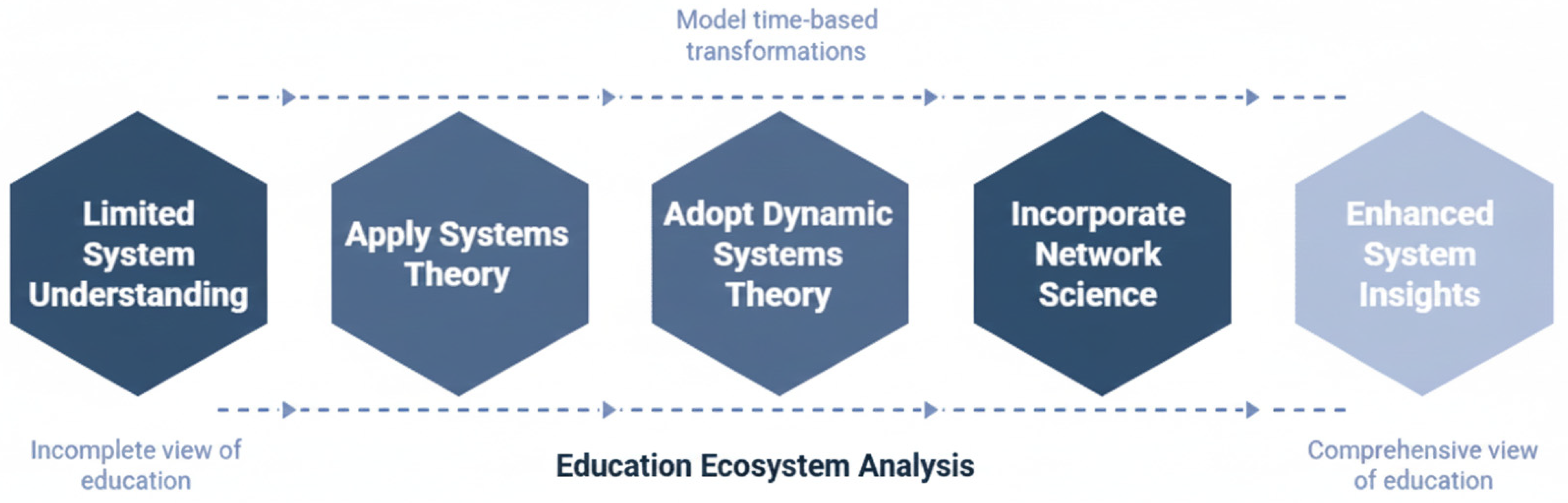

3. Theoretical Grounding

- Systems Theory; defining system components, boundaries, and interdependencies;

- Dynamic Systems Theory; modelling transformation, stability, and non-linear dynamics through semantic similarity patterns;

- Network Science; representing the ecosystem as a graph of weighted connections generated from Word2Vec similarity outputs.

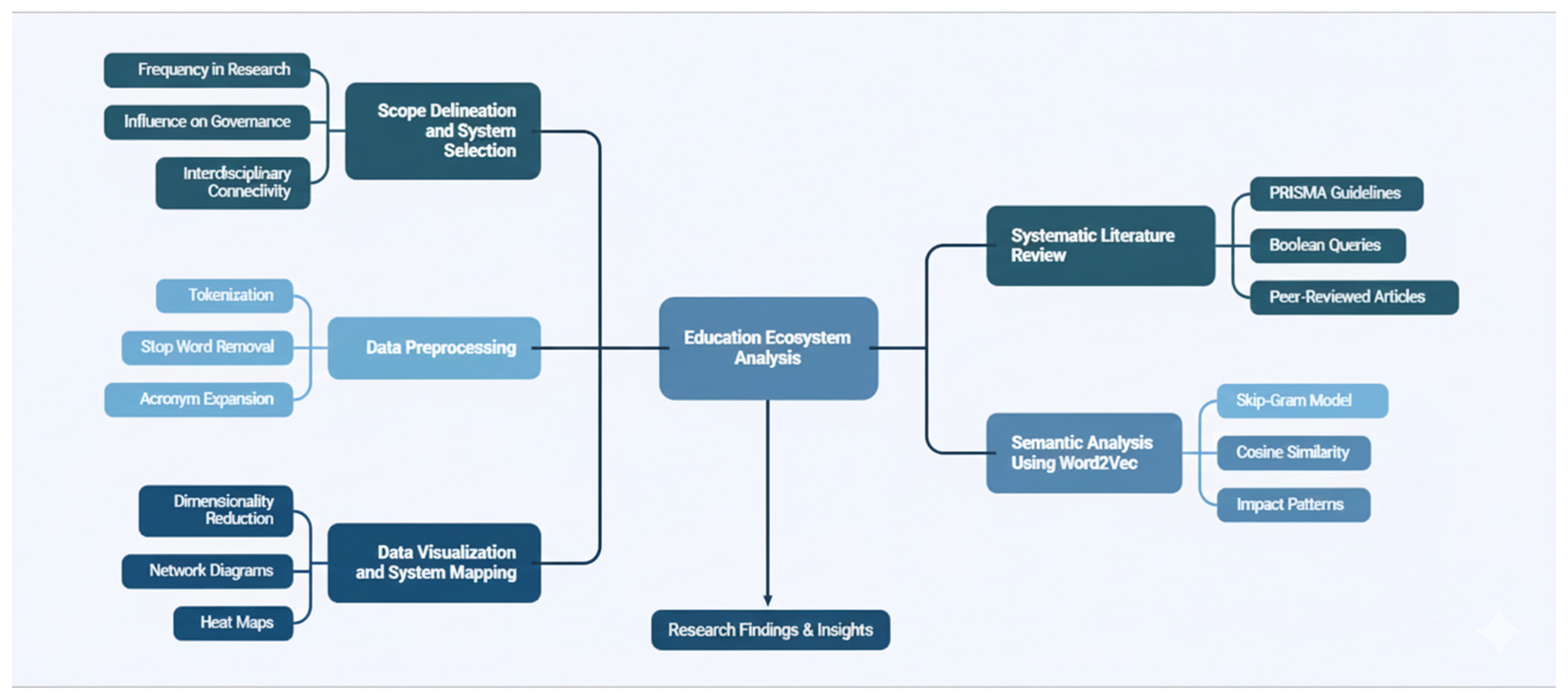

4. Methodology

- Step 1: Scope Delineation and System Selection

- Step 2: Systematic Literature Review (SLR)

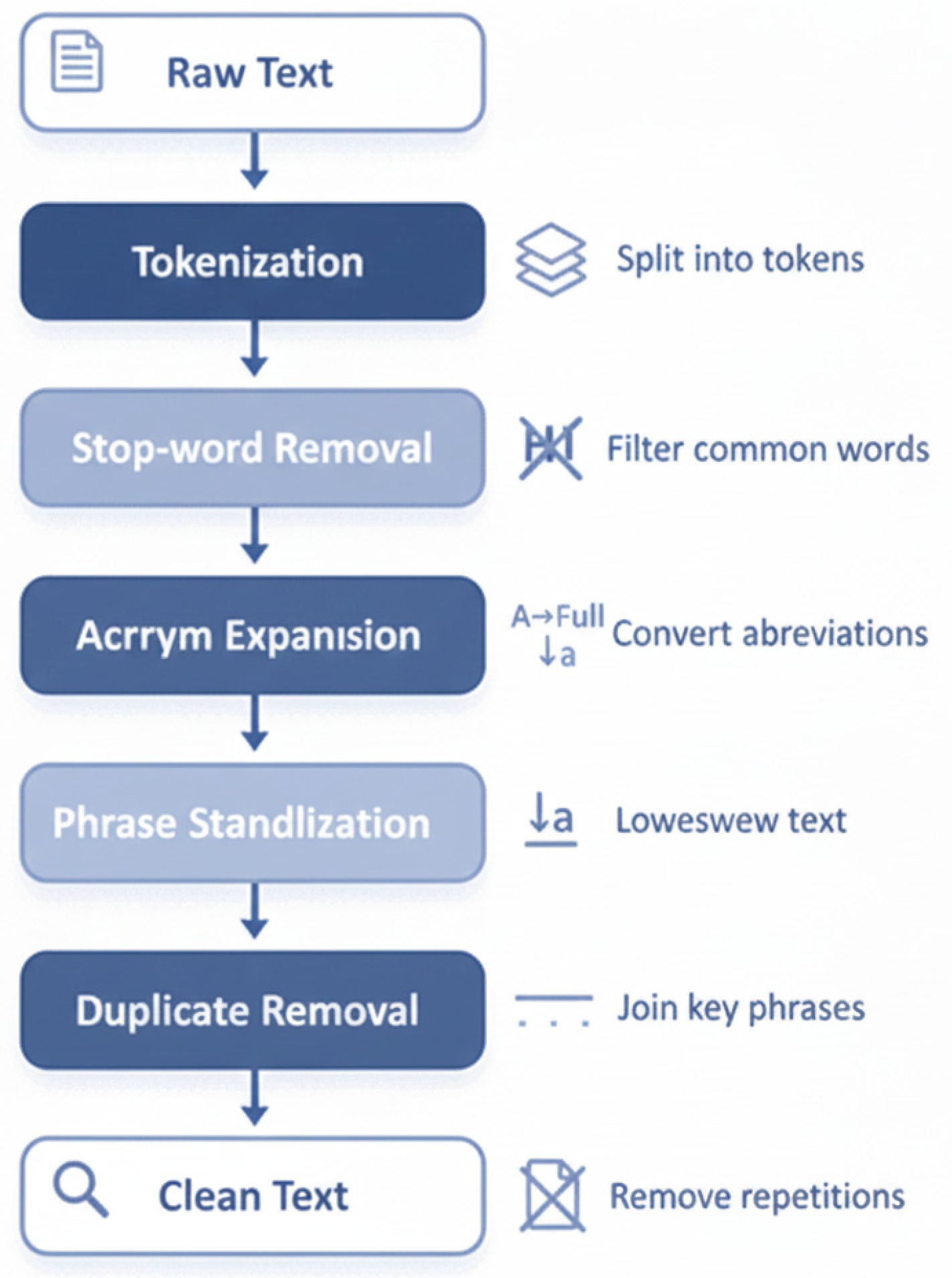

- Step 3: Data Preprocessing

- Step 4: Semantic Analysis Using Word2Vec

- Step 5: Data Visualization and System Mapping

5. Results

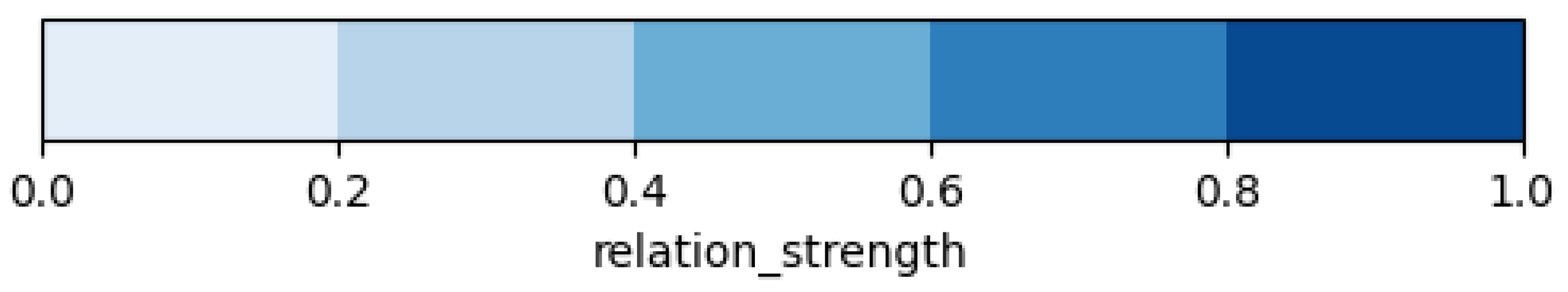

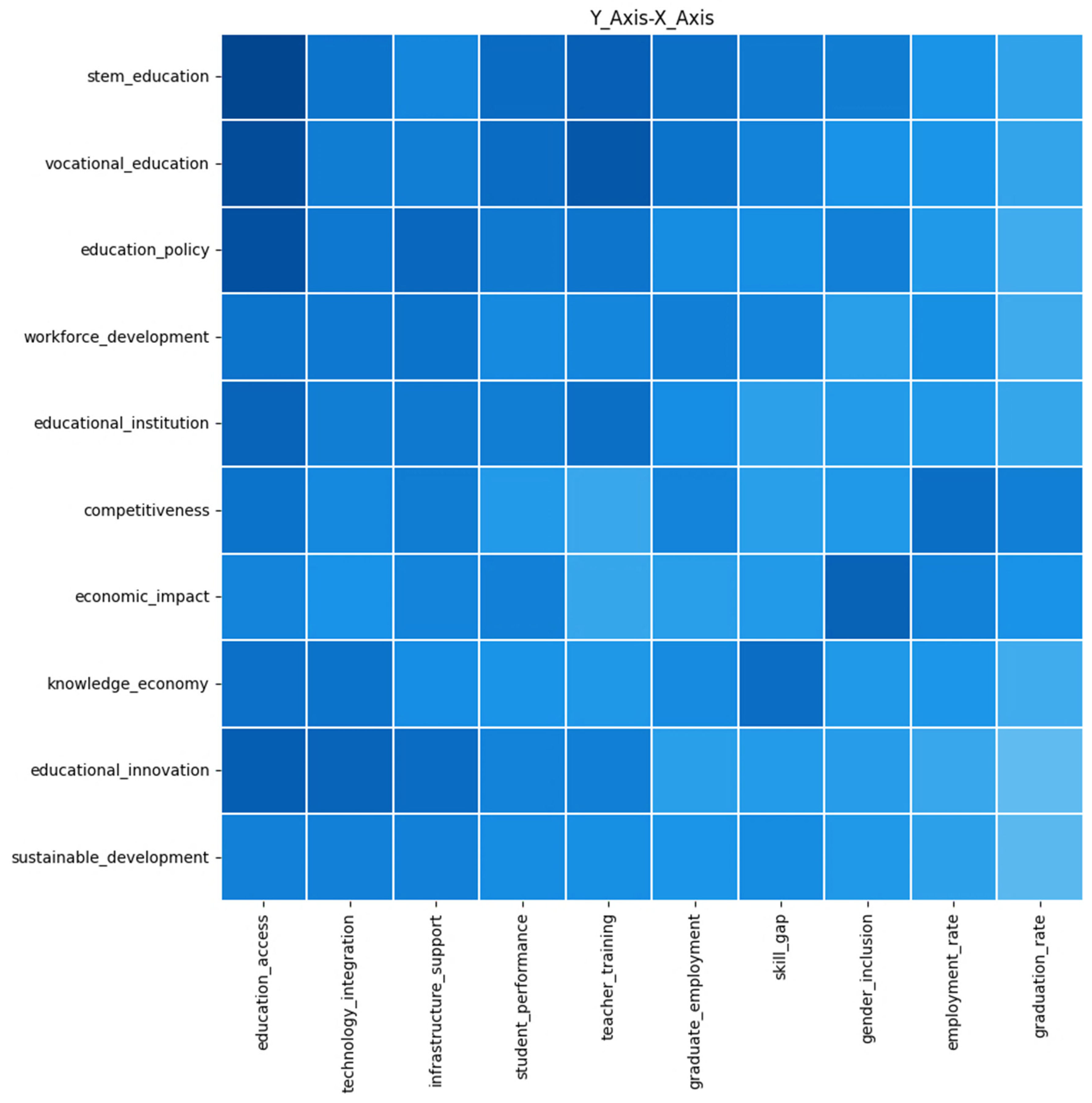

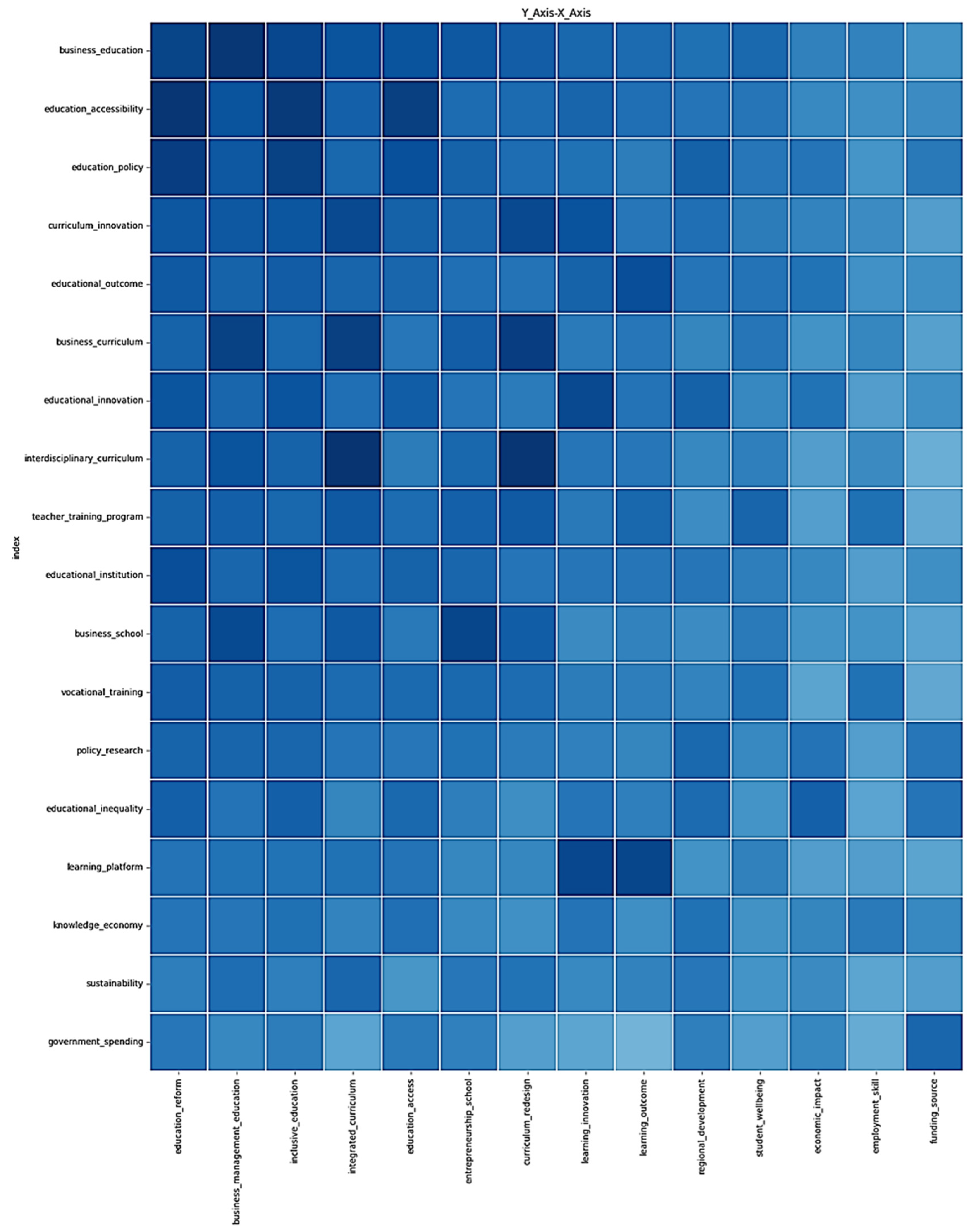

5.1. Heatmap Analysis and Interpretation

5.2. The Holistic Ecosystem vs. The Economy System of Education

- From Business: industry partnership, student engagement, and research output.

- From Economy: economic growth, employment rates, investment in education, knowledge economy indicators.

- From Government: policy support, government spending, and educational outcomes.

- From Healthcare: mental health support, healthcare infrastructure, and access equity.

- From Sustainability: sustainability education, curriculum revision, and sustainability research.

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

8. Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ramírez-Montoya, M.S. Analysis of open education in Latin America in the framework of UNESCO’s new recommendations. Rev. Interuniv. Form. Profr. 2022, 98, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Montoya, M.-S. MOOCs and OER: Developments and Contributions for Open Education and Open Science. In Lecture Notes in Educational Technology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honorato-Errázuriz, J.; Ramírez-Montoya, M.S. Intervention model to promote reading in basic education: Contributions to public policies. In ACM International Conference Proceeding Series; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazyliuk, A.; Khomenko, V.; Ilchenko, V. World Experience of Investing and Human Capital Development. In Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.; Loader, R. Is academic selection in Northern Ireland a barrier to social cohesion? Res. Pap. Educ. 2022, 39, 420–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, H.; Williamson, J.; Siebert, C. Exploring Perceptions Related to Teacher Retention Issues in Rural Western United States. Aust. Int. J. Rural. Educ. 2022, 32, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, Y. Individualized and Innovation-Centered General Education in a Chinese STEM University. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.L.; Cerdeira, L.; Machado-Taylor, M.L.; Alves, H. Technological skills in higher education—Different needs and different uses. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osovsky, O.; Chernetsova, E.; Kirzhaeva, V.; Maslova, E. Education-for-myself and education-for-the other: The right to freedom of education and mikhail Bakhtin’s experience. Dialogic. Pedagog. 2020, 8, SF71–SF79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuno, C.B.; Hein, S.; Frankel, L.; Kim, H.J. Children’s schooling status: Household and individual factors associated with school enrollment, non-enrollment and dropping out among Ugandan children. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 2021, 2, 100033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krafft, C.; Sieverding, M.; Berri, N.; Keo, C.; Sharpless, M. Education Interrupted: Enrollment, Attainment, and Dropout of Syrian Refugees in Jordan. J. Dev. Stud. 2022, 58, 1874–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, D.; Cabrera, L. What Is Systems Thinking? In Learning, Design, and Technology: An International Compendium of Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1495–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, P.; Stanton, N.A.; Walker, G.H.; Hulme, A.; Goode, N.; Thompson, J.; Read, G.J. Handbook of Systems Thinking Methods, 1st ed.; CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 2023; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Koopmans, M. Education is a Complex Dynamical System: Challenges for Research. J. Exp. Educ. 2020, 88, 358–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strokosch, K.; Osborne, S.P. Co-experience, co-production and co-governance: An ecosystem approach to the analysis of value creation. Policy Polit. 2020, 48, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, J.; Goodman, J. Parental socioeconomic status, child health, and human capital. In The Economics of Education: A Comprehensive Overview; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2020; pp. 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Sobrinho, R.A.; Zilly, A.; Silva, R.M.M.D.; Arcoverde, M.A.M.; Deschutter, E.J.; Palha, P.F.; Bernardi, A.S. Coping with COVID-19 in an international border region: Health and economy. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2021, 29, e3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilgiler Eğitimi Araştırmaları Dergisi, S.; Sukmayadi, V.; Yahya, A.H. Indonesian Education Landscape and the 21st Century Challenges. J. Soc. Stud. Educ. Res. 2020, 2, 219–234. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow, W.D. Primary-Secondary Transition—Building Hopes and Diminishing Fears Through Drama. Front. Educ. 2021, 5, 546243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovar Reaños, M.A. Fuel for poverty: A model for the relationship between income and fuel poverty. Evidence from Irish microdata. Energy Policy 2021, 156, 112444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postiglione, G.; Tang, M. International experience in TVET-industry cooperation for China’s poorest province. Int. J. Train. Res. 2019, 17, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampoltshammer, T.J.; Albrecht, V.; Raith, C. Teaching digital sustainability in higher educationfrom a transdisciplinary perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callender, C.; Dougherty, K.J. Student choice in higher education-reducing or reproducing social inequalities? Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panasenko, K.E.; Voloshina, L.N.; Shinkareva, L.V.; Galimskaya, O.G. Socialization-individualization of preschool children with speech disorders in motor activity. J. Med. Chem. Sci. 2021, 4, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, E.V.; Nagata, S.; Hall, C.; Akimoto, S.; Barber, L.; Sawae, Y. Developing a Socially-Just Research Agenda for Inclusive Physical Education in Japan. Quest 2023, 75, 361–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servant-Miklos, V.; Noordegraaf-Eelens, L. Toward social-transformative education: An ontological critique of self-directed learning. Crit. Stud. Educ. 2021, 62, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavyalova, E.; Alsufyev, A.; Krakovetskaya, I.; Lijun, W.; Li, J. Personnel development in Chinese innovation-active companies. Foresight STI Gov. 2018, 12, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalapati, N.; Chalapati, S. Building a skilled workforce: Public discourses on vocational education in Thailand. Int. J. Res. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2020, 7, 67–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, K. Integrating Young People into the Workforce: England’s Twenty-First Century Solutions. Societies 2022, 12, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, K. Artificial intelligence and healthcare professional education: Superhuman resources for health? Postgrad Med. J. 2020, 96, 121–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quennerstedt, M. Healthying physical education—On the possibility of learning health. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2019, 24, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, H.; Wang, H.; Liu, X. Effect of health education on healthcare-seeking behavior of migrant workers in China. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruin, S.; Stibbe, G. Health-oriented ‘Bildung’ or an obligation to a healthy lifestyle? A critical analysis of current PE curricula in Germany. Curric. J. 2021, 32, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-García, C.; López-Medina, I.M.; Sanz-Martos, S.; Álvarez-Nieto, C. Planetary health: Education for sustainable healthcare. Educ. Medica. 2021, 22, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonaro, A.; Kuzelka, J.A.M.B.; Piccinini, F. A new digital divide threatening resilience: Exploring the need for educational, firm-based, and societal investments in ICT human capital. J. E-Learn. Knowl. Soc. 2022, 18, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froehlich, D.E.; Van Waes, S.; Schäfer, H. Linking Quantitative and Qualitative Network Approaches: A Review of Mixed Methods Social Network Analysis in Education Research. Rev. Res. Educ. 2020, 44, 244–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriani, E.; Priskananda, A.A.; Budiraharjo, M. A Cultural-Historical Activity Theory (CHAT) Analysis on Educational Psychology Class: The Challenges in Delivering a Fully Online Classroom Environment. J. Foreign Lang. Teach. Learn. 2022, 7, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaremych, H.E.; Preacher, K.J.; Hedeker, D. Centering Categorical Predictors in Multilevel Models: Best Practices and Interpretation. Psychol. Methods 2021, 28, 613–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Droogenbroeck, F.; Spruyt, B.; Quittre, V.; Lafontaine, D. Does the School Context Really Matter for Teacher Burnout? Review of Existing Multilevel Teacher Burnout Research and Results from the Teaching and Learning International Survey 2018 in the Flemish- and French-Speaking Communities of Belgium. Educ. Res. 2021, 50, 290–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vulic, J.; Jacobson, M.J.; Levin, J.A. Exploring Education as a Complex System: Computational Educational Research with Multi-Level Agent-Based Modeling. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Inverno, G.; Smet, M.; De Witte, K. Impact evaluation in a multi-input multi-output setting: Evidence on the effect of additional resources for schools. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2021, 290, 1111–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieshaber, S.; Hunkin, E. Complexifying quality: Educator examples. Front. Educ. 2023, 8, 1161107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, N.U.I.; Dayarathna, V.L.; Nagahi, M.; Jaradat, R. Systems thinking: A review and bibliometric analysis. Systems 2020, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaaban, Y.; Al-Thani, H.; Du, X. A systems-thinking approach to evaluating a university professional development programme. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2023, 50, 296–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dughi, T.; Rad, D.; Runcan, R.; Chiș, R.; Vancu, G.; Maier, R.; Costin, A.; Rad, G.; Chiș, S.; Uleanya, C.; et al. A Network Analysis-Driven Sequential Mediation Analysis of Students’ Perceived Classroom Comfort and Perceived Faculty Support on the Relationship between Teachers’ Cognitive Presence and Students’ Grit—A Holistic Learning Approach. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikolov, T.; Chen, K.; Corrado, G.; Dean, J. Efficient Estimation of Word Representations in Vector Space. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1301.3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWaters, J.; Kotla, B. Using an open-ended socio-technical design challenge for entrepreneurship education in a first-year engineering course. Front. Educ. 2023, 8, 1198161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, R.; Hadžikadić, M. Complex Adaptive Systems, Systems Thinking, and Agent-Based Modeling. In Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 3, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M.A.; Ritala, P. A complex adaptive systems agenda for ecosystem research methodology. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 148, 119739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, C.; Asamoah, L. Education and sustainability: Reinvigorating adult education’s role in transformation, justice and development. Int. J. Lifelong Educ. 2016, 35, 590–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnveden, G.; Schneider, A. Sustainable Development in Higher Education—What Sustainability Skills Do Industry Need? Sustainability 2023, 15, 4044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincon, E.; Rodriguez-Guidonet, I.; Andrade-Pino, P.; Monfort-Vinuesa, C. Mixed Reality in Undergraduate Mental Health Education: A Systematic Review. Electronics 2023, 12, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zilioli, S.; Balzarini, R.N.; Zoppolat, G.; Slatcher, R.B. Education, Financial Stress, and Trajectory of Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 10, 662–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| System | Search String |

|---|---|

| Business & Education | (“education” AND “business systems” OR “corporate education models”) |

| Economy & Education | (“education” AND “economic factors” OR “education and economy”) |

| Government & Education | (“education governance systems” OR “policy in education”) |

| Healthcare & Education | (“health and education” OR “school health programs”) |

| Sustainability & Education | (“sustainable education systems” OR “education sustainability models”) |

| Component | Description |

|---|---|

| Database | Scopus |

| Timeframe | 2014–2024 |

| Total Records Retrieved | 271,950 |

| Final Included Articles | 5742 |

| Total Extracted Text | 32.4 million words |

| Final Token Count (after cleaning) | 22.1 million |

| System | Highest-Performing Indicators (Values) | Lowest-Performing (Values) | Brief Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Business & Education | Curriculum development—Sustainable development (0.87); Entrepreneurship education—Student engagement (0.81); Active learning—Student engagement (0.83) | Accreditation—Sustainability (0.518); Accreditation—Economic development (0.516) | Strong student–industry integration and employability focus; accreditation remains compliance-driven rather than developmental. |

| Government & Education | Education policy—Policy implementation (0.93); Funding sources—Resource availability (0.76); Educational outcomes—Student performance (0.81) | Accessibility—Student engagement (0.44); Inclusivity—Enrollment (0.45) | Effective at policy rollout and funding efficiency but benefits are uneven, widening access and equity gaps. |

| Healthcare & Education | Healthcare access equity (0.987); Mental health campaigns (0.912); Healthcare infrastructure (0.967) | Cognitive development—Screening (0.375); Immunization—Staff training (0.312) | Strong healthcare access and mental health support, but early interventions and staff training are insufficient. |

| Sustainability & Education | Sustainability research—Research initiatives (0.926); Sustainability literacy—Stakeholder engagement (0.816); Sustainability courses—Curriculum revision (0.872) | Awareness campaigns—Collaborative projects (0.616); Industry partnership (0.607) | Strong sustainability integration into academic programs; outreach and industry collaboration are weaker. |

| Economy & Education (expanded in Section 6) | - | - | This system is analysed separately due to its centrality to the study. |

| Index | Employment Rate | Educational Access | Skill Gap | Graduation Rate | Student Performance | Technology Integration | Graduate Employment | Infrastructure Support | Gender Inclusion | Teacher Training |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| educational innovation | 0.57 | 0.82 | 0.62 | 0.47 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.77 | 0.61 | 0.71 |

| educational institution | 0.62 | 0.8 | 0.59 | 0.57 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.66 | 0.72 | 0.62 | 0.76 |

| knowledge economy | 0.64 | 0.76 | 0.77 | 0.54 | 0.64 | 0.75 | 0.67 | 0.66 | 0.63 | 0.63 |

| education policy | 0.62 | 0.88 | 0.66 | 0.54 | 0.72 | 0.73 | 0.67 | 0.79 | 0.71 | 0.74 |

| economic impact | 0.7 | 0.69 | 0.62 | 0.65 | 0.71 | 0.65 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.81 | 0.57 |

| sustainable development | 0.59 | 0.71 | 0.67 | 0.48 | 0.66 | 0.7 | 0.64 | 0.7 | 0.62 | 0.66 |

| stem education | 0.64 | 0.92 | 0.72 | 0.58 | 0.77 | 0.74 | 0.76 | 0.69 | 0.72 | 0.81 |

| workforce development | 0.66 | 0.74 | 0.7 | 0.55 | 0.67 | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.75 | 0.6 | 0.69 |

| competitiveness | 0.76 | 0.75 | 0.6 | 0.71 | 0.62 | 0.68 | 0.7 | 0.72 | 0.62 | 0.57 |

| vocational education | 0.64 | 0.89 | 0.7 | 0.57 | 0.77 | 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.71 | 0.65 | 0.85 |

| System | Variable | Value | Cross-Cutting Variables |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education & Business | Student Engagement | 0.814 | All |

| Research Output | 0.765 | ||

| Industry Partnership | 0.800 | ||

| Government & Education | Government Spending | 0.809 | Policy Support |

| Educational Outcome | 0.823 | ||

| Policy Support | 0.947 | ||

| Healthcare | Healthcare Access Equity | 0.987 | Student Engagement |

| Mental Health Support | 0.912 | ||

| Healthcare Infrastructure | 0.967 | ||

| Sustainability | Sustainability Education | 0.860 | Student Engagement, Curriculum Revision, Research Output, Policy Support |

| Curriculum Revision | 0.872 | ||

| Sustainability Research | 0.926 |

| Index | Education Reform | Learning Innovation | Business Management Education | Entrepreneurship School | Integrated Curriculum | Economic Impact | Funding Source | Learning Outcome | Educational Access | Curriculum Redesign | Employment Skill | Inclusive Education | Student Wellbeing | Regional Development |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| education policy | 0.94 | 0.75 | 0.85 | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.74 | 0.72 | 0.70 | 0.88 | 0.77 | 0.61 | 0.94 | 0.72 | 0.81 |

| educational innovation | 0.86 | 0.90 | 0.79 | 0.74 | 0.76 | 0.74 | 0.63 | 0.74 | 0.82 | 0.71 | 0.58 | 0.87 | 0.67 | 0.81 |

| educational institution | 0.89 | 0.73 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.77 | 0.67 | 0.63 | 0.73 | 0.80 | 0.74 | 0.58 | 0.86 | 0.70 | 0.73 |

| business education | 0.93 | 0.79 | 0.97 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 0.69 | 0.62 | 0.77 | 0.86 | 0.83 | 0.69 | 0.91 | 0.78 | 0.75 |

| business school | 0.80 | 0.65 | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.84 | 0.62 | 0.55 | 0.69 | 0.72 | 0.82 | 0.62 | 0.76 | 0.72 | 0.65 |

| business curriculum | 0.80 | 0.72 | 0.93 | 0.83 | 0.94 | 0.62 | 0.56 | 0.73 | 0.72 | 0.94 | 0.67 | 0.79 | 0.73 | 0.67 |

| government spending | 0.72 | 0.54 | 0.67 | 0.70 | 0.55 | 0.67 | 0.79 | 0.48 | 0.72 | 0.57 | 0.52 | 0.71 | 0.57 | 0.70 |

| knowledge economy | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.73 | 0.66 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.66 | 0.64 | 0.76 | 0.63 | 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.62 | 0.75 |

| educational outcome | 0.84 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.76 | 0.80 | 0.74 | 0.64 | 0.89 | 0.79 | 0.74 | 0.63 | 0.83 | 0.74 | 0.74 |

| teacher training program | 0.81 | 0.72 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.84 | 0.57 | 0.53 | 0.79 | 0.77 | 0.84 | 0.75 | 0.79 | 0.80 | 0.64 |

| Learning platform | 0.74 | 0.91 | 0.74 | 0.67 | 0.75 | 0.58 | 0.55 | 0.92 | 0.74 | 0.67 | 0.58 | 0.75 | 0.69 | 0.62 |

| educational inequality | 0.82 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.70 | 0.68 | 0.81 | 0.74 | 0.70 | 0.78 | 0.64 | 0.55 | 0.81 | 0.62 | 0.78 |

| policy research | 0.80 | 0.69 | 0.80 | 0.75 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.72 | 0.67 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.57 | 0.79 | 0.66 | 0.78 |

| interdisciplinary curriculum | 0.80 | 0.73 | 0.86 | 0.79 | 0.98 | 0.58 | 0.50 | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.98 | 0.65 | 0.80 | 0.70 | 0.67 |

| curriculum innovation | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.85 | 0.80 | 0.90 | 0.68 | 0.57 | 0.72 | 0.81 | 0.91 | 0.65 | 0.85 | 0.71 | 0.76 |

| education accessibility | 0.97 | 0.79 | 0.86 | 0.77 | 0.81 | 0.66 | 0.65 | 0.76 | 0.94 | 0.77 | 0.63 | 0.96 | 0.73 | 0.74 |

| sustainability | 0.70 | 0.66 | 0.76 | 0.73 | 0.79 | 0.65 | 0.58 | 0.69 | 0.61 | 0.74 | 0.54 | 0.70 | 0.62 | 0.73 |

| vocational training | 0.82 | 0.71 | 0.81 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.55 | 0.53 | 0.70 | 0.78 | 0.77 | 0.75 | 0.80 | 0.74 | 0.68 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gamede, N.; Munsamy, M.; Telukdarie, A. Unpacking Key Systems Towards a Sustainable Education Ecosystem. Sustainability 2026, 18, 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010282

Gamede N, Munsamy M, Telukdarie A. Unpacking Key Systems Towards a Sustainable Education Ecosystem. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):282. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010282

Chicago/Turabian StyleGamede, Noluthando, Megashnee Munsamy, and Arnesh Telukdarie. 2026. "Unpacking Key Systems Towards a Sustainable Education Ecosystem" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010282

APA StyleGamede, N., Munsamy, M., & Telukdarie, A. (2026). Unpacking Key Systems Towards a Sustainable Education Ecosystem. Sustainability, 18(1), 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010282