1. Introduction

In recent years, offshore wind energy has evolved from a promising alternative to one of the pillars of the global energy transition. Installed capacity, which was modest around 2010, reached 64.3 GW in 2022 [

1]. This figure is expected to double by the end of 2025, surpassing 130 GW and consolidating offshore generation as a key component in global decarbonization strategies [

1].

This rapid expansion of the offshore wind industry has not occurred in isolation but reflects broader global energy and technological transitions. Such growth has been supported by ambitious international frameworks, most notably the 2015 Paris Agreement, which reaffirmed the global commitment to accelerate renewable energy deployment as consistent with international climate frameworks such as the Paris Agreement [

2,

3]. Nearly all major economies have since raised their renewable energy targets, positioning offshore wind as a key driver of net-zero strategies. Global projections indicate that roughly 2000 GW of offshore wind may be required by 2050 to align with Paris targets [

4]; this implies a leap from current installed capacity on the order of tens of gigawatts. These policy-driven ambitions have been reinforced by the growing recognition that offshore wind energy development must be guided by sustainability frameworks that integrate environmental, economic, and social dimensions throughout the project lifecycle, in line with life-cycle assessment principles [

3].

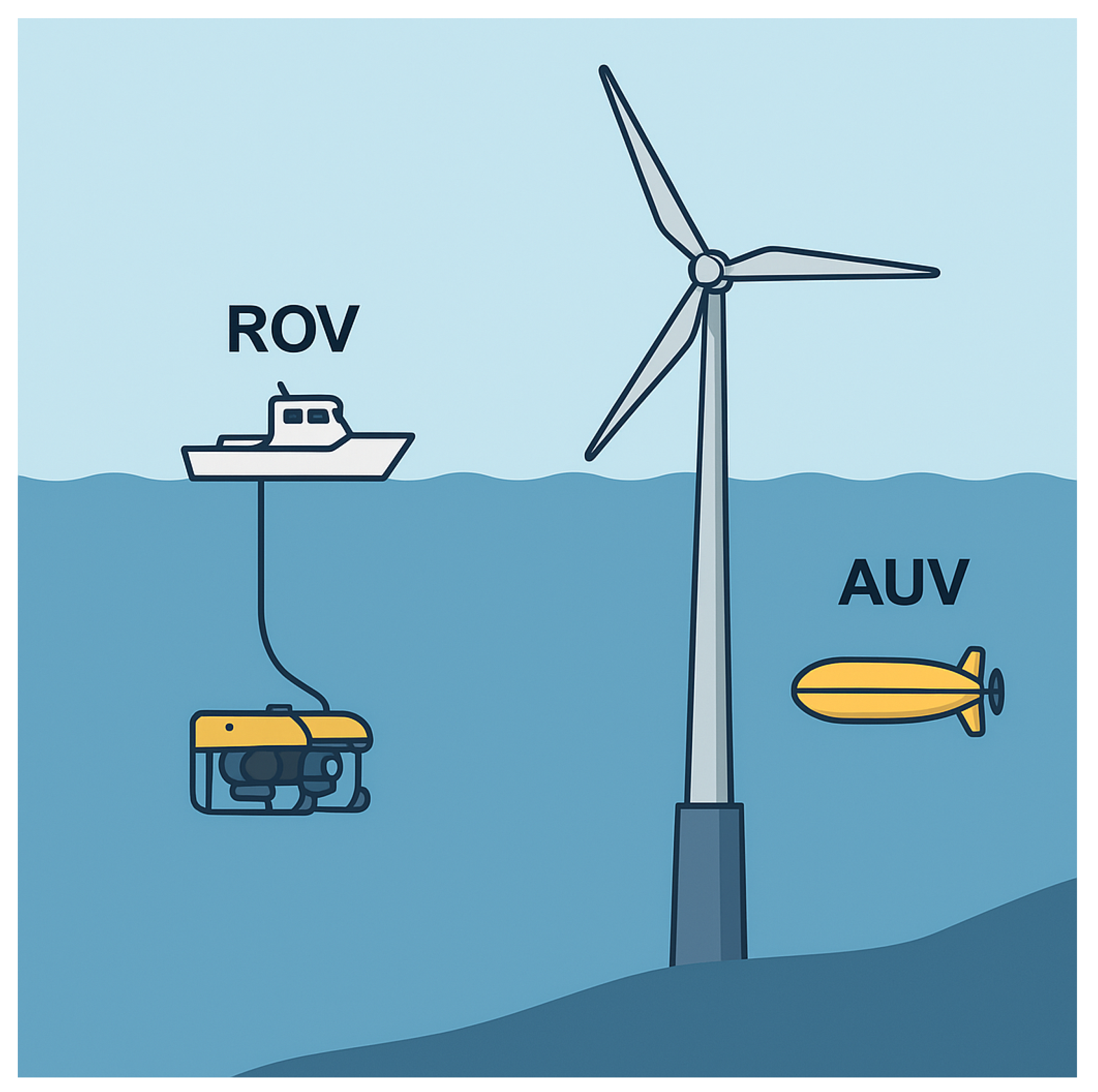

The rapid policy-driven growth of offshore renewables has been paralleled by significant technological progress in marine robotics. The evolution of underwater vehicles spans more than six decades: the first autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV), the Special Purpose Underwater Research Vehicle, was developed in 1957 at the University of Washington’s Applied Physics Laboratory [

5]. During the 1960s and 1970s, military and industrial applications drove the rapid development of tethered systems, giving rise to the first remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) used for deep-sea recovery and offshore inspection tasks [

6]. Over time, innovations in propulsion, control systems, and sensors transformed these early “flying eyeballs” into sophisticated robotic platforms capable of precise manipulation, high-resolution imaging, and autonomous navigation. Today, ROVs and AUVs represent mature technologies employed across scientific, commercial, and offshore industrial sectors, reflecting growing interest in renewable-energy applications [

5].

This growth has been led by a group of pioneering countries. China stands out as the largest offshore market, with more than 37 GW installed in 2023 [

7], surpassing the traditional European leader, the United Kingdom (14.7 GW in 2023 [

8]). The United States, still in an early stage, has made remarkable progress. The South Fork Wind Farm (132 MW) was commissioned in March 2024, totaling about 0.174 GW of offshore capacity by March 2025. Although still below 0.2 GW, federal initiatives such as the approval of the 704 MW Revolution Wind project highlight the goal of reaching 30 GW by 2030 [

9,

10]. In Europe, Denmark, which inaugurated the world’s first offshore wind farm in 1991, has reached 2.65 GW of offshore capacity, with wind power now accounting for 59.3% of its electricity mix [

11]. Altogether, these cases illustrate not only the global demand for clean energy but also the establishment of robust industrial supply chains and innovation hubs dedicated to offshore technologies.

As offshore wind farms expand in scale, number, and depth, their operation and maintenance (O&M) have become increasingly complex [

12]. Within the broader context of the energy transition, O&M phases, traditionally labor-intensive, are being progressively automated through robotic and digitalised solutions, which play an essential role in reducing labor costs and improving efficiency [

12]. This shift is part of a broader trend toward predictive and data-driven maintenance paradigms, supported by emerging practices such as structural health monitoring (SHM) that leverage multisource heterogeneous data [

13]. Recent reviews highlight the pivotal role of automation, artificial intelligence, and robotics in reshaping offshore wind O&M, setting the stage for smarter and more resilient maintenance strategies [

14].

To overcome these limitations, autonomous and semi-autonomous underwater systems have emerged as critical tools, enabling continuous inspection, condition monitoring, and predictive maintenance while minimizing human exposure and vessel dependency [

15,

16]. These advancements collectively enhance safety, reduce operational costs, and expand weather windows, thereby lowering the levelized cost of energy (LCOE) and improving the overall sustainability of offshore operations [

16,

17]. Given these converging technological and policy developments, it becomes essential to understand how ROVs and AUVs enable safer and more sustainable operations with improved efficiency.

The present review aims to provide a comprehensive and sustainability-oriented assessment of recent advances, operational challenges, and future directions in the use of underwater robotic systems for offshore wind operation and maintenance. Building on a systematic approach grounded in the PRISMA protocol, it synthesizes recent high-impact literature to map how ROVs and AUVs contribute to safer, more efficient, and environmentally responsible offshore operations.

The methodological procedures adopted in this study follow a transparent and replicable PRISMA-based framework, encompassing the definition of search strings, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and multistage filtering to ensure the reliability of the selected corpus. The technological overview presents the classification, architecture, and functionalities of underwater vehicles, establishing the conceptual foundation for subsequent analyses. Applications in offshore wind farms are then explored, focusing on inspection, maintenance, environmental monitoring, and collaborative multi-robot operations that integrate aerial, surface, and subsea platforms.

Subsequent sections expand on the integration of artificial intelligence and digital-twin systems, examining how these tools enhance predictive maintenance, decision-making autonomy, and structural health monitoring. The sustainability dimension is also addressed, analyzing how underwater robotics supports environmental, economic, and social objectives consistent with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The discussion consolidates the main operational challenges, reliability issues, and research gaps that still constrain large-scale deployment, leading to a final synthesis of lessons learned and future research directions.

Beyond technical synthesis, this review offers a cross-domain perspective connecting robotics, digitalization, and sustainability, an approach not yet consolidated in previous reviews. By integrating AI-driven autonomy, digital-twin supervision, and ESG-oriented evaluation, it establishes a unified framework to assess how underwater robotic systems contribute to a safer, smarter, and more sustainable offshore energy transition.

2. PRISMA-Based Methodology Literature Review

This review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) framework to ensure transparency, reproducibility, and methodological rigor in the selection and analysis of the scientific literature. This study focused on peer-reviewed works addressing the use of remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), and autonomous surface vehicles (ASVs) in the operation and maintenance (O&M) of offshore wind farms.

2.1. Search Strategy and Data Sources

The systematic search was conducted exclusively in Scopus, chosen for its broad indexing of multidisciplinary engineering journals, including IEEE, Elsevier, and MDPI. Scopus provides unified coverage across robotics, ocean engineering, and renewable-energy domains, avoiding redundancy among multiple databases.

A complementary exploratory search was performed in Google Scholar to identify the contextual and historical materials used in the Introduction, though only Scopus-indexed studies were retained for systematic analysis. The search string applied was as follows

("ROV" OR "Remotely Operated Vehicle" OR "AUV" OR

"Autonomous Underwater Vehicle" OR "Autonomous Vessels")

AND ("offshore wind" OR "floating wind" OR "offshore maintenance")

Bibliographic retrieval and preprocessing were supported by

Publish or Perish (PoP) [

18] and Python-based scripts in

Google Colaboratory [

19], which performed deduplication, metadata normalization, and keyword tagging. The initial corpus comprised 88 articles published between 2016 and 2025, a decade corresponding to the commercial expansion of offshore wind farms and the parallel evolution of subsea robotics for inspection and maintenance tasks. The Scopus database search and retrieval process were completed in June 2025, ensuring the inclusion of the most recent Scopus-indexed publications prior to manuscript preparation

2.2. Methodological Framework

The methodological framework ensured transparency and consistency with PRISMA through four structured stages:

(1) Database Identification: The search and retrieval process used the defined Boolean string on Scopus, targeting works on subsea robotics and offshore O&M. Scopus was selected for its integrated coverage of engineering and renewable-energy journals, minimizing duplication across platforms.

(2) Data Cleaning and Preprocessing: Duplicates and off-topic entries were automatically identified and removed using Publish or Perish (v8) and Python-based routines. Data normalization harmonized author names, keywords, and journal titles, yielding a unified metadata structure for consistent filtering.

(3) Screening and Eligibility: Titles, abstracts, and keywords were reviewed manually following predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Only peer-reviewed journal articles written in English (2016–2025) were retained. Excluded works included those unrelated to offshore wind, lacking experimental validation, or addressing robotics in non-energy contexts. Screening emphasized thematic convergence with offshore wind, subsea robotics (ROV, AUV, and ASV), and sustainability-oriented O&M.

(4) Qualitative Synthesis: From the screened dataset, 23 core studies were included in the final analytical corpus, selected for methodological rigor, clarity of validation, and relevance to O&M lifecycles. Citation frequency and publisher impact were considered secondary relevance indicators. This synthesis was qualitative, prioritizing interpretive and methodological depth rather than quantitative aggregation, in line with the diversity of research designs encountered.

This staged process ensured methodological transparency and minimized selection bias while preserving the validity and reproducibility of the systematic review.

2.3. Screening and Selection

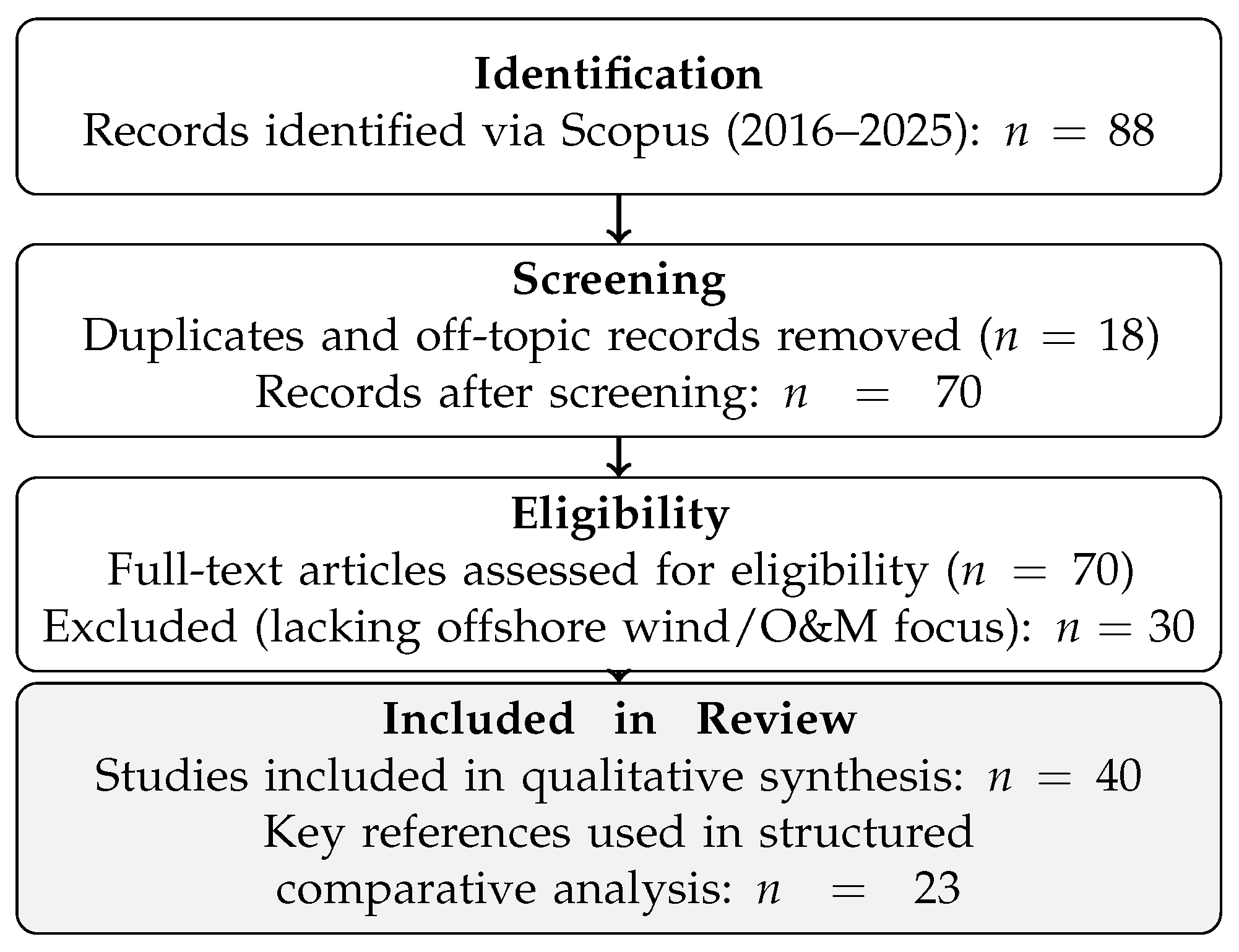

After automated and manual filtering, the staged reduction followed the PRISMA flow shown in

Figure 1.

From 88 initial Scopus records, 18 were removed as duplicates or off-topic, 30 were excluded during abstract or full-text screening, and 40 remained for qualitative synthesis. Among these, 23 were identified as core analytical studies forming the structured comparative analysis corpus, while additional contextual references complemented the technological and historical background, totaling 50 references across the manuscript.

Two classification-oriented studies [

20,

21] were consulted to define the baseline taxonomy of subsea vehicles (inspection, intervention, and hybrid ROVs). These were used for conceptual support only and were not part of the systematic corpus.

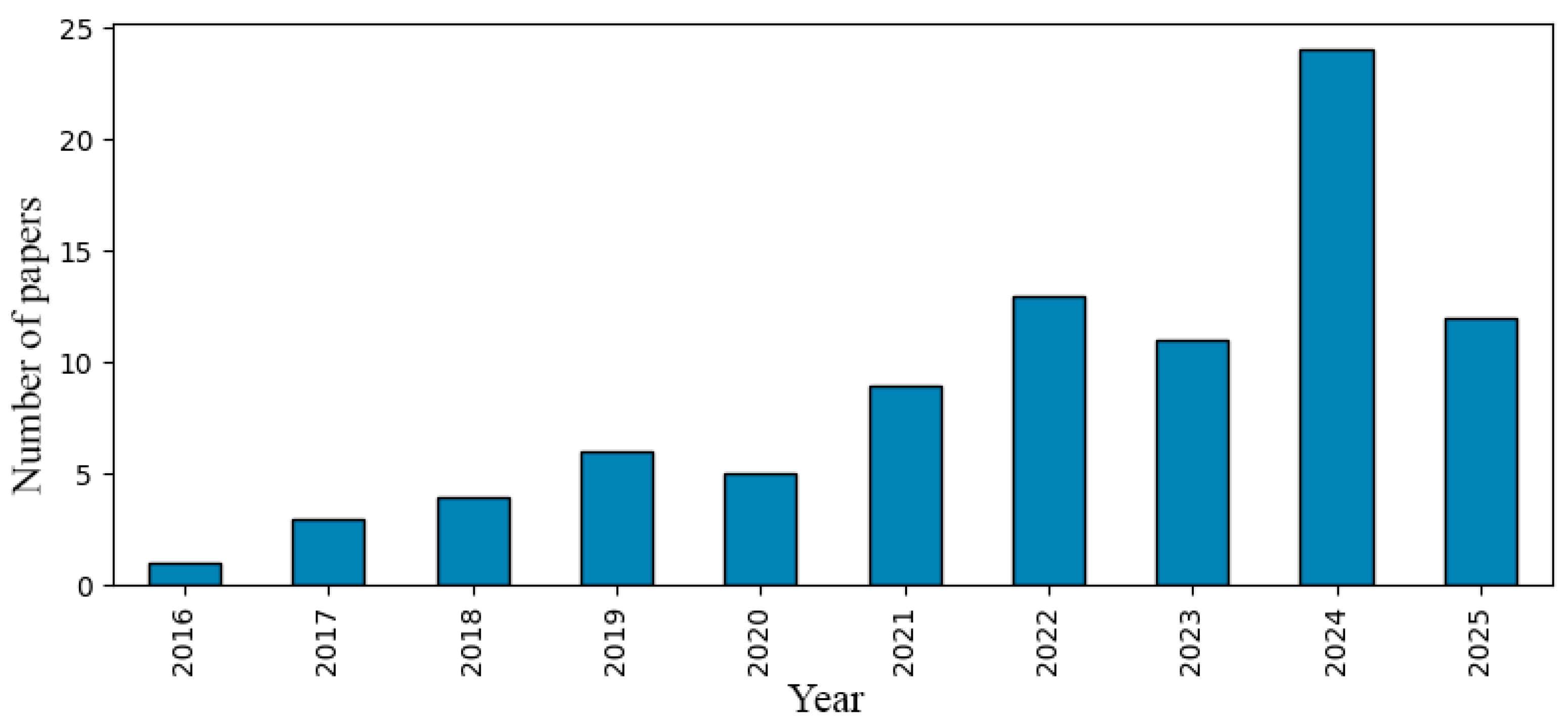

Figure 2 illustrates the yearly distribution of the initial corpus before filtering, showing a sharp growth in publications from 2022 onward. This trend confirms the inclusion of recent and high-impact studies from leading publishers in offshore robotics and renewable energy O&M.

2.4. PRISMA Flow Description

The selection pathway summarized in

Figure 1 demonstrates a transparent and replicable process aligned with the PRISMA protocol, reinforcing the methodological consistency of the review.

4. Applications in Offshore Wind Energy

This section synthesizes how ROVs and AUVs are employed across inspection, maintenance, monitoring, and collaborative tasks within offshore wind farms. It consolidates examples from

Section 3 into four operational domains: (i) inspection and maintenance, (ii) environmental monitoring, (iii) multi-robot and logistical coordination, and (iv) technological challenges and lessons learned. Subsequent

Section 5 and

Section 6 build on these applications to discuss integration with AI, digital twins, and sustainability frameworks.

4.1. Inspection and Maintenance

Performing inspections and maintenance in offshore wind turbines involves technical challenges aggravated by harsh marine environments. In this context, ROVs and AUVs have emerged as strategic tools for ensuring structural integrity and enabling subsea interventions without deploying human personnel.

Inspection activities include foundation analysis, subsea cable monitoring, and corrosion detection in metallic components. ROVs are widely applied for visual inspection of monopiles and spar buoys, structures exposed to cyclic loading from waves and currents [

29]. Beyond visual imaging, acoustic sensors and MBES allow seabed mapping and detection of internal anomalies, while ultrasonic thickness sensors and corrosion probes provide quantitative data on material degradation [

24,

27]. An illustrative case is the FLOW-CAM platform, which integrates real-time imaging with onboard processing to estimate residual life of inspected components, thus supporting predictive maintenance strategies [

23,

36].

Maintenance operations range from routine procedures such as biofouling removal to more complex interventions, including sacrificial anode replacement, cable repair, and structural reinforcement. ROVs and AUVs are increasingly deployed in both fixed and floating offshore wind turbines (FOWTs), reflecting growing technological maturity and the demand for safer, more efficient, and cost-effective solutions [

23,

29]. Recent prototypes demonstrate robust manipulators and intuitive human–machine interfaces capable of executing precision interventions under variable currents and low visibility [

31]. Intervention AUVs have also shown the capability to perform autonomous light repairs, indicating an ongoing transition toward fully automated subsea maintenance [

26].

Reliability is a critical factor in offshore robotic operations, where harsh marine environments often cause unplanned downtime and equipment degradation. Field studies demonstrate that robotic and semi-autonomous systems enhance operational safety and continuity by automating inspection and maintenance tasks in hazardous conditions [

37]. Although standardized indicators such as mean time between failures (MTBF) and mean time to repair (MTTR) are still seldom reported for offshore platforms, recent trials indicate improved availability and fault tolerance through predictive control, digital-twin supervision, and resident “garage” concepts [

38,

39]. Together, these advances mark a shift from reactive to condition-based maintenance, strengthening long-term reliability and safety in offshore wind operations.

Operational control strategies and their integration with digital twins are further explored in

Section 5, where the focus shifts from physical interventions to autonomous perception, decision-making, and predictive analytics.

To enhance comparability across distinct O&M domains,

Table 2 summarizes a subset of representative studies illustrating how different robotic platforms contribute to offshore wind inspection, maintenance, and environmental monitoring. A comprehensive cross-reference of all 23 studies included in the PRISMA corpus is presented later in this paper.

To consolidate the findings derived from the PRISMA corpus, a quantitative synthesis was performed to categorize the reviewed studies by their principal application domains and vehicle types. The resulting distribution is presented in

Table 3, which summarizes the thematic composition of the corpus across inspection, maintenance, environmental monitoring, AI integration, and multi-robot collaboration domains.

Among the 23 studies retained, 39% focus primarily on inspection, 22% on maintenance and cleaning operations, 13% on AI or digital-twin integration, and 9% on collaborative hybrid operations. ROVs remain the dominant platform (57%), followed by AUVs (30%) and hybrid multi-robot systems (13%). Studies published after 2022 exhibit a growing emphasis on autonomy, resident operations, and multi-robot collaboration, reflecting a maturation from purely inspection-oriented tasks to integrated O&M solutions.

4.2. Environmental Monitoring

In offshore wind farm operations, environmental monitoring plays a strategic role that goes beyond structural safety. It is an essential part of ongoing efforts to understand and mitigate the impacts of installations on marine ecosystems. Systematic observation of environmental conditions and biodiversity supports more informed decision-making, ensuring that operation and maintenance (O&M) activities proceed in line with sustainability principles. In this context, ROVs, AUVs, UAVs, and USVs have increasingly been deployed as mobile data collection platforms, enabling real-time environmental assessments.

Subsea structures such as monopiles, spar buoys, and scour protections modify the surrounding marine environment, often functioning as artificial reefs that enhance local biodiversity. Studies indicate that, when properly planned, these modifications may generate positive ecological effects [

22]. To document these changes, ROVs and AUVs are used in periodic surveys that record both the presence and distribution of organisms. Recent work has demonstrated automated vision-based techniques for detecting and assessing key structural elements, such as sacrificial anodes, which contribute to long-term ecosystem and asset monitoring [

27].

Environmental monitoring also plays a preventive role during subsea interventions. Vessel movement, robotic deployment, or cable handling can generate acoustic disturbances that affect fish and marine mammals sensitive to noise. To address this, AI-driven methods are increasingly applied to process acoustic and visual data in real time, detecting abnormal behavior and anticipating risks. Complementary approaches, such as acoustic modeling with side-scan sonars, allow the identification of critical areas and the redirection of operations to reduce ecological impact [

22,

24].

Another growing development is the integration of digital twins with robotic platforms. Continuously updated with structural and environmental data, these models enable predictive simulations and dynamic adjustments to O&M planning. As emphasized by Berker et al. [

36], synchronization between onboard and cloud-based digital twins allows the early detection of ecological risks, such as seabed shifts or variations in marine fauna, enabling real-time adaptation of maintenance operations.

Combining environmental sensors with robotic platforms has enabled more holistic monitoring strategies. Multisensor configurations, which integrate acoustic sensors, high-resolution cameras, and physicochemical probes into a single system, provide a 360-degree perspective of offshore environments. These datasets not only support structural integrity assessments but also facilitate long-term ecological monitoring. Historical data collected by these platforms allows temporal comparisons and the detection of progressive changes, whether natural or related to human activity [

40]. Innovations such as robust docking under low visibility and autonomous docking success evaluation further enhance the scalability of long-term monitoring solutions [

34].

Ultimately, robotic technologies in offshore environmental monitoring strengthen the ability to reconcile operational efficiency with ecological responsibility. By integrating embedded sensors, advanced analytics, and digital models, these systems support a more nuanced and adaptive approach to O&M. This alignment ensures both structural reliability and reduced ecological footprint, directly supporting the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Specifically, robotic monitoring fosters clean energy expansion (SDG 7), safeguards marine biodiversity (SDG 14), and contributes to climate action. For instance, Khalid et al. [

38] note that deploying autonomous surface vessels (ASVs/USVs) for inspection and logistics can reduce dependence on crewed transfer vessels and service vessels, thereby lowering operational costs and the emissions associated with repeated manned trips offshore, although no quantitative CO

2 estimate is provided.

In this perspective, subsea vehicles evolve from operational tools into strategic enablers of an energy transition model that respects ecological boundaries while maintaining the innovation and scale required for global decarbonization.

4.3. Emerging Trends and Future Directions

In recent years, subsea robotics applied to the operation and maintenance of offshore wind farms has undergone rapid and transformative changes. Emerging technologies are beginning to reshape the way inspections and interventions are conducted, paving the way for increasingly autonomous and adaptive operations in challenging marine environments.

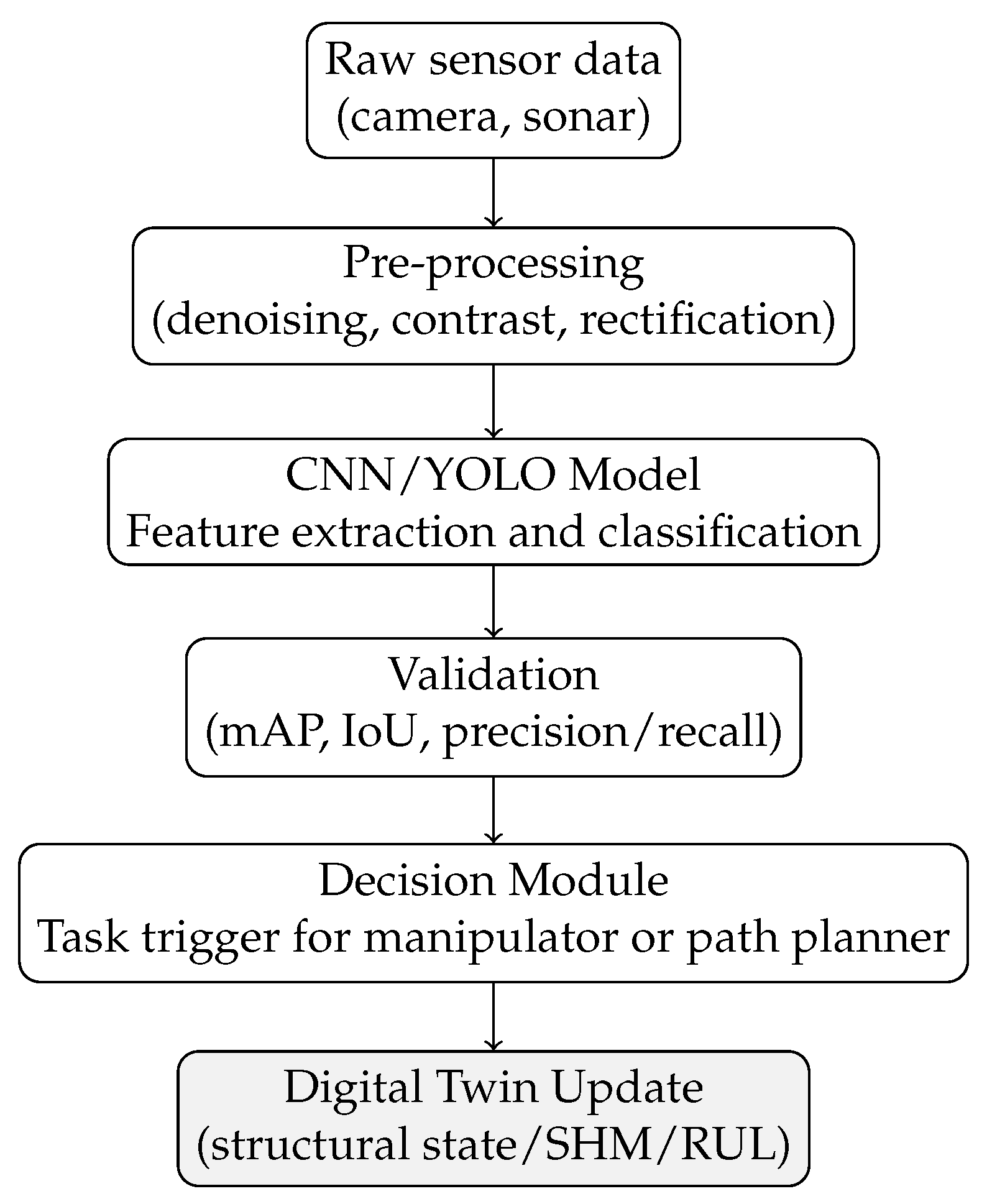

AI has progressed beyond simple automated visual analysis. Advanced deep-learning methods, such as YOLOv12 [

41], are now shifting from centralized processing to distributed edge-computing approaches onboard the vehicles, reducing latency and enabling local decision-making in remote missions. AI is also expanding into more complex and delicate tasks, including autonomous maintenance tasks (e.g., anode replacement) and direct intervention in structural components, missions that were previously impossible without human presence [

26].

Although the concept of digital twins has already been explored, current developments emphasize deeper and more interactive applications, with virtual models running directly on subsea vehicles. This hybrid connection between cloud-based models and embedded hardware enables real-time decision-making. As a result, offshore wind turbines may experience significant reductions in operational expenditure (OPEX) and an extension of asset lifetimes, ultimately improving return on investment in Capital Expenditure (CAPEX) [

36].

Multi-robot architectures have already proven their operational value, but current research focuses on overcoming persistent challenges such as the standardization of communication protocols (e.g., ROS-Marine), improved robustness against cyber threats, and the deployment of advanced collaborative methods including distributed Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) and adaptive task allocation algorithms. These efforts aim to enhance cross-platform interoperability among UAV, USV, ROV, and AUV systems, enabling scalable and safe multi-robot operations [

35,

37].

Energy capacity remains a fundamental constraint for long-duration subsea missions. Both ROVs and, in particular, intervention AUVs face endurance limits imposed by onboard battery power, which can become insufficient when operating high-demand tools or performing extended tasks. Recent studies highlight that this limitation is one of the principal barriers to fully autonomous maintenance operations, with some authors even deeming “onboard battery power infeasible” for certain cleaning and intervention applications [

26]. To address this challenge, resident or “garage” concepts such as subsea docking and recharging stations have been proposed and tested to allow vehicles to replenish energy and continue operations without frequent surface retrievals [

24,

26].

From a sustainability perspective, the current emphasis lies in quantifying the environmental benefits of robotic operations. International initiatives highlight that replacing conventional crewed vessels with unmanned surface vehicles (USVs) can significantly reduce fuel consumption and associated CO

2 emissions, directly supporting ESG goals and SDGs [

38]. Such metrics strengthen the sector’s ability to demonstrate its concrete contribution to SDG 13 (Climate Action), complementing the recognized roles in SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) and SDG 14 (Life Below Water) [

39].

4.4. Multi-Robot Collaboration and Logistical Integration

Multi-robot collaboration has become a cornerstone of next-generation offshore maintenance, linking aerial, surface, and subsea robotic systems into cohesive and adaptive networks. This subsection analyzes how UAVs, USVs, ROVs, and AUVs cooperate through shared control frameworks, logistics optimization, and distributed autonomy to increase operational safety and efficiency.

Recent frameworks emphasize cooperative architectures supported by intelligent control and real-time data exchange. Zhang et al. [

40] propose a hierarchical system where UAVs conduct aerial surveys, USVs act as communication and logistics hubs, and ROVs/AUVs execute subsea operations (

Figure 4).

The architecture relies on an autonomous middleware that allocates tasks dynamically, adapting mission plans to environmental changes in current, wind, and visibility. Such coordination enhances system resilience and precision, marking a shift toward more intelligent and flexible offshore inspection paradigms.

Foster et al. [

35] reinforce this concept with a multi-robot framework tailored for offshore wind farms. In this setup, UAVs carry out visual inspections of turbines, USVs provide surface support and positioning, while ROVs perform subsea interventions. Managed by autonomous systems, this division of labor enhances agility, reduces turbine downtime, and improves logistical and energy efficiency. The key advantage of multi-robot systems lies in their ability to combine autonomy with cooperation: each platform contributes its specialty while maintaining synchronized responses to environmental changes in real time. Nordin et al. [

42] further highlight how autonomous control systems for manipulators and sensors enhance this coordination, enabling tighter synchronization across robotic teams and reducing the degree of human intervention required for complex subsea operations. Their study demonstrates that cooperative control and sensor fusion architectures can substantially improve mission safety and task accuracy under dynamic offshore conditions. Hu et al. [

43] extend this logic with mixed-integer and adaptive search algorithms to coordinate AUV fleets, achieving substantial reductions in total inspection duration and operational cost.

Maintaining reliable trajectories under dynamic sea states remains a critical challenge. Santos et al. [

44] integrate IMU data from turbine platforms into ROV controllers to stabilize trajectories in floating wind conditions, while Zhang et al. [

40] demonstrate equivalent robustness in aerial inspections using multi-sensor adaptive path planning. This convergence of control strategies across domains underlines the potential of unified autonomy frameworks for aerial and underwater agents.

Reducing OPEX and emissions increasingly depends on optimizing vessel logistics. Deng et al. [

39] demonstrate that deploying ROVs from small offshore service vessels (OSVs) via a single-point mooring system (SPMS) can safely replace large dynamic-positioning ships, yielding measurable economic and environmental benefits. Ren et al. [

45] confirm that SPMS minimizes relative motion between vessel and structure, while Khalid et al. [

38] emphasize that autonomous robotics reduce the need for frequent crew-transfer missions, aligning O&M practices with global decarbonization targets.

Distributed robotic cooperation and optimized logistics form the operational backbone of sustainable offshore maintenance, linking the physical layer of robotic activity with the digital intelligence of AI and twin-enabled decision support for fully autonomous O&M.

4.5. Operational Challenges and Lessons Learned

Carrying out subsea inspection and maintenance in offshore wind farms imposes technical demands far beyond those encountered in conventional marine environments. Instability of the sea state, limited visibility, and the interaction with large-scale structures create scenarios in which ROVs and AUVs face significant constraints in navigation, perception, and control. Overcoming these barriers is a prerequisite for safe and efficient deployment.

Low visibility remains one of the most persistent problems in subsea missions, particularly in highly sedimented or naturally turbid waters. Even high-resolution optical sensors lose effectiveness under these conditions. As a result, imaging sonars and multibeam echosounders (MBESs) have become essential tools, enabling reliable mapping and defect detection in opaque environments [

24,

28]. Sensor-fusion strategies that combine acoustic, optical, and inertial data are critical to maintaining robustness in visually restricted conditions [

28].

The constant motion of vessels and floating wind turbines introduces another operational challenge. During deployment, recovery, or close-proximity maneuvers, oscillations can compromise safety or damage equipment. Predictive and disturbance-rejection control approaches help mitigate these effects by anticipating current and wave disturbances, enabling smoother operations [

46]. Inertial measurement units (IMUs), integrated with sonar-based navigation, further enhance fine-grained positioning and stability under dynamic hydrodynamic conditions [

24].

For ROVs, the umbilical cable is both indispensable and restrictive. It supplies power and ensures real-time communication but limits horizontal mobility and may become a liability under rough seas. Strategic deployment points and optimized tether-management systems can reduce these constraints [

39]. In contrast, AUVs eliminate the tether but remain constrained by onboard energy capacity, which continues to limit endurance. Subsea docking stations (“garages”) have therefore been developed to enable recharging and data transfer between missions, extending autonomous operation windows [

24].

Deep-water or high-energy environments introduce additional complexity due to fluid–structure interactions among the vehicle, tether, and support vessel. Wave-induced loads can destabilize positioning and reduce availability. Modeling and simulation tools allow evaluation of these couplings and the optimization of safe weather windows [

30]. Field studies also show that placing tether connectors at greater depths reduces wave-motion interference, improving operational continuity [

39].

Recent analyses further emphasize that subsea environments impose unique challenges to perception and localization because of current irregularities, metallic interference, and acoustic noise near turbine structures. These disturbances often degrade sonar mapping and sensor synchronization. While

Section 5 details AI-driven and digital-twin-based mitigation strategies, at the operational level, the lessons learned point to the need for standardized calibration routines, adaptive filtering, and redundancy in navigation sensors to ensure mission reliability under extreme marine dynamics.

6. Sustainability and SDG Alignment

The deployment of ROVs and AUVs in offshore wind operation and maintenance (O&M) contributes not only to technical efficiency but also to sustainability across the economic, environmental, and social pillars. This section consolidates these contributions under the ESG framework (Environmental, Social, and Governance) and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy), SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure), SDG 13 (Climate Action), and SDG 14 (Life Below Water).

Replacing large, crewed service vessels with autonomous or semi-autonomous systems directly reduces OPEX and the levelized cost of energy (LCOE) [

38,

39].

Recent analyses indicate that the transition to robotic inspection and maintenance allows shorter vessel time, lower fuel consumption, and fewer offshore transfers, producing cost savings of up to 30% in typical O&M campaigns [

38]. These improvements align with SDG 9 by fostering innovation and industrial efficiency, while also supporting SDG 7 by improving the economic viability of renewable energy generation.

ROVs and AUVs further enable predictive maintenance through AI and digital-twin integration [

36], reducing unscheduled downtime and extending asset lifetime. Such practices strengthen the financial sustainability of offshore projects by minimizing risk exposure and improving return on capital expenditure (CAPEX).

6.1. Environmental Performance and Climate Action

From an environmental perspective, the substitution of traditional vessel-intensive operations with autonomous robotics significantly reduces fuel use and associated CO

2 emissions [

39].

Deng et al. [

39] demonstrate that deploying ROVs from smaller offshore service vessels (OSVs) through a single-point mooring system (SPMS) reduces both fuel consumption and the carbon footprint, offering a direct contribution to SDG 13 (Climate Action).

ROVs and AUVs are also instrumental in environmental monitoring. By collecting continuous biodiversity and water-quality data, they support adaptive management strategies and ecosystem-based assessments [

22].

This capability ensures that offshore wind expansion remains compatible with marine conservation goals (SDG 14, Life Below Water). Furthermore, resident or “garage” systems [

34] minimize vessel travel frequency, reducing acoustic pollution and disturbance to marine fauna.

Digital twins complement these practices by tracking cumulative environmental impacts through time [

36]. When integrated with real-time robotic data, DTs can facilitate transparent ESG reporting and support compliance with environmental standard regulations, reinforcing the governance dimension of sustainability.

6.2. Social and Safety Dimensions

The social dimension of sustainability is equally relevant.

Autonomous and remotely operated systems substantially reduce the need for divers and on-site personnel, mitigating exposure to high-risk marine conditions and lowering accident rates [

37]. This contributes to SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) through safer labor conditions and higher-quality employment.

The shift from physical to digital operations also promotes workforce upskilling. Technicians increasingly transition toward competencies in robotics control, AI-based data analysis, and remote mission supervision rather than manual offshore work.

This transition encourages the creation of specialized, knowledge-based employment within the offshore renewable sector, supporting SDG 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 9.

6.3. Governance, Reporting, and ESG Integration

In addition to technical and environmental gains, the use of robotic and digital systems strengthens governance by enabling standardized, auditable data flows. Through digital twins and AI-based analytics, operators can quantify maintenance efficiency, energy use, and emissions reduction, core indicators in ESG reports. Integrating these data streams into corporate sustainability frameworks improves transparency, facilitates benchmarking among operators, and supports alignment with global frameworks.

6.4. Integrated Sustainability Outlook

Overall, the integration of ROVs, AUVs, and digital-twin systems represents a technological evolution consistent with the environmental and social imperatives of the energy transition.

By merging operational efficiency with ecological stewardship and worker safety, autonomous subsea systems establish a direct link between innovation (SDG 9), clean energy production (SDG 7), climate action (SDG 13), and marine protection (SDG 14). These synergies illustrate how offshore robotics serve as both an enabler and a validator of sustainability in the global offshore wind industry.

Table 4 consolidates all studies retained after the full-text screening described in

Section 2. Each reference is categorized according to its primary technological focus, analytical section within this manuscript, and main contribution to offshore wind O&M. This comprehensive synthesis closes the systematic component of this review and precedes the broader discussion in

Section 7.

7. Discussion

The systematic synthesis of the twenty-three studies retained through the PRISMA protocol reveals a rapidly evolving landscape in offshore wind operation and maintenance (O&M), where robotic autonomy, artificial intelligence, and digital twin integration are redefining industrial practices. While individual studies demonstrate notable advances in control, sensing, and mission design, the cross-domain analysis indicates persistent barriers to large-scale and sustainable deployment, particularly regarding interoperability, reliability, and long-term validation.

Across the corpus, three converging insights can be drawn. First, autonomous systems do not replace human expertise but rather redistribute it, shifting operational focus toward supervision, data interpretation, and mission-level decision-making. Mixed human–robot configurations, as discussed in [

35,

42], are reported to enhance safety and operational continuity by reducing direct human exposure and distributing workload across robotic teams. Most studies, however, present qualitative evidence or conceptual analyses rather than standardized safety or efficiency benchmarks, indicating that these benefits, while promising, remain to be quantitatively validated under real offshore O&M conditions. Second, the value of multi-platform coordination is evident. Combined architectures enhance spatial coverage and inspection speed, yet interoperability remains limited by ad hoc middleware and proprietary communication standards [

40,

43]. Third, the integration of AI-based perception with digital-twin simulation has emerged as a foundation for predictive maintenance and decision support in offshore renewables [

36]. Validation datasets remain scarce, and few studies provide uncertainty quantification or standardized performance metrics.

Despite the solid progress in automation and perception, several research gaps remain critical. Data scarcity continues to limit the generalization of AI models, which are often trained on simulated or site-specific datasets lacking cross-environment validation under variable turbidity, illumination, and hydrodynamic conditions. Energy autonomy also constrains resident AUVs and long-endurance ROV missions, as battery technology and subsea recharging infrastructures remain at the experimental stage [

34]. Interoperability across heterogeneous platforms is still constrained by communication challenges and environmental limitations that are often overlooked in experimental prototypes [

35]. At the fleet-planning level, cooperative optimization approaches improve coordination efficiency but continue to rely on simplified assumptions about communication and energy constraints rather than standardized middleware implementations [

24,

43]. Even more concerning is the lack of standardized reliability benchmarks and verified long-term performance data. Although recent reviews summarize operational failures and incident trends in subsea systems [

37], quantitative reliability statistics remain scarce across the literature. Socio-environmental evaluation also remains underexplored: while diver safety and emission reductions are well documented, potential acoustic impacts, seabed disturbances, and end-of-life material recycling have received limited attention.

When viewed through the lens of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the reviewed literature demonstrates clear alignments between technological innovation and sustainability objectives. Under SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy), robotic inspection and predictive maintenance directly reduce O&M costs and downtime, lowering the levelized cost of energy (LCOE). Under SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure), advances in mechatronics, AI, and DT integration strengthen industrial resilience and promote innovation in digital offshore infrastructure. SDG 13 (Climate Action) is addressed through the replacement of large crewed service vessels with autonomous units, reducing CO2 and NOx emissions across maintenance cycles. Finally, SDG 14 (Life Below Water) benefits from the expansion of resident robotic monitoring and biodiversity mapping, which enhance ecosystem understanding while minimizing diver interference with marine fauna. Collectively, these synergies position subsea robotics not only as a technological enabler but also as a direct contributor to climate and ocean sustainability.

Looking ahead, several research directions emerge from the gaps and future perspectives identified across this review [

34,

35,

37,

40,

42]. Priority efforts should focus on explainable and adaptive AI capable of real-time learning in dynamic marine environments; persistent energy autonomy through inductive charging and renewable-powered docking [

34,

42]; and standardized interoperability supported by open communication protocols and shared simulation environments [

35,

40]. Equally important is the establishment of harmonized reliability benchmarks aligned with ISO and DNV standards to enable certified, industry-ready offshore robotic systems. These directions define a coherent roadmap for the next five years of research and technological maturation in offshore robotic O&M.

8. Conclusions

The reviewed literature confirms that robotic systems are rapidly transforming offshore wind operation and maintenance (O&M) through enhanced autonomy, perception, and sustainability integration. ROVs and AUVs now form the backbone of digital offshore infrastructure, improving safety, reducing environmental impact, and enabling predictive maintenance. Despite these technological advances, several open challenges persist that hinder full-scale industrial deployment and long-term sustainability assessment.

A consistent pattern across the reviewed corpus reveals three central research gaps: (i) Most developments remain validated only in laboratory or short-term pilot settings; (ii) Data interoperability across UAV, USV, ROV, and AUV platforms is still fragmented; (iii) The absence of standardized reliability indicators and fault-classification protocols prevents objective benchmarking and certification. These limitations restrict reproducibility and delay the consolidation of best practices for autonomous O&M systems. Building on these findings, future research should prioritize long-term offshore trials, open communication frameworks, and harmonized reliability benchmarks aligned with ISO and DNV standards to enable certified, industry-ready robotic solutions.

In summary, ROVs and AUVs have transitioned from supportive inspection tools to central components of an integrated, digital, and sustainable offshore ecosystem. Their fusion with AI-driven analytics, digital-twin frameworks, and cooperative robotic networks marks the onset of a new operational paradigm characterized by autonomy, resilience, and environmental accountability. By reducing human exposure to hostile environments, lowering logistical dependence on large vessels, and enabling continuous inspection and predictive maintenance, these technologies contribute directly to safer and more efficient operations. Beyond technical innovation, subsea robotics also reinforces the environmental and social commitments of the offshore wind sector, supporting lower carbon footprints, biodiversity monitoring, and safer working conditions. Altogether, these advances point toward an offshore energy sector that is more autonomous, distributed, and environmentally responsible and sustainable pillar of the future energy mix.