1. Introduction

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is an increasingly important element of corporate strategy. Defined as a business strategy that focuses on a company’s responsibilities to society, CSR has moved beyond its original philanthropy roots to incorporate discretionary investments in community building and business sustainability with links to organizational performance. As such, CSR encompasses initiatives such as mitigating climate change [

1], adopting renewable energy [

2], promoting gender equality, and reducing global poverty. These efforts also increase organizational resilience [

3] and performance [

4]. CSR is now a core element of corporate strategy, reflecting its crucial role in addressing societal and environmental responsibilities [

1] in the private sector [

5,

6].

While CSR has a rich history, sustainability is a recent term linked with how corporations interact with society and how the environment impacts corporations. Officially defined by the United Nations Brundtland Commission (1987) as meeting present needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs [

1], sustainability is a relevant initiative as corporations integrate CSR into their basic principles [

7]. Hence, reporting on sustainability is a key component of CSR activities and involves measuring, disclosing, and being accountable for a business’s economic, social, and environmental impacts [

3]. It aids firms in tracking their progress toward CSR goals and communicating their performance to stakeholders [

4].

Most recently, corporate disclosures associated with CSR, including sustainability, have taken center stage [

8,

9], driven by a growing awareness of the importance of disclosure about companies’ CSR strategies [

10] and regulatory frameworks in some locations (e.g., India, the European Union, the United States) that are mandating such disclosures. Disclosures about CSR are becoming integrated into CSR strategies as a driving force emphasizing economic, environmental, and social factors [

11]. Companies disclose their CSR activities through various labels [

12] like sustainability reporting, impact reporting, CSR reporting, ESG reporting, etc. The inconsistency in nomenclature is problematic, because there has been a tendency to treat these distinct concepts as isomorphic, yet that has not always been true. CSR is grounded in firms’ philanthropic interactions with society, ESG has historically been focused on financial risks facing companies on material sustainability issues, and impact is a general term that essentially means to have a strong effect. Using these terms as synonyms for sustainability leads to confusion because of the range of interpretations they naturally evoke. This communication gap has implications for stakeholder trust, transparency, and long-term engagement.

Although CSR and CSR-associated reporting have attracted increasing scholarly attention, there remains a gap in understanding the strategic communication mechanisms underlying CSR disclosures. Few studies have explored how communication strategies influence CSR effectiveness over time, and correspondingly scant research attention has integrated communication theory with CSR evolution in the context of digital transformation. This study addresses these gaps by conducting a bibliometric analysis in the context of CSR and CSR-associated reporting in the era of sustainability. The link between these constructs requires a prudent understanding of fundamentals, trends, and patterns, which are explored in this paper. Specifically, the study sought to (1) identify the foundational concepts that underpin CSR and CSR communications, (2) analyze thematic clusters revealing the current focus and intellectual structure of CSR and sustainability communication research, (3) explore how the thematic structures within CSR sustainability communication literature evolved thematically over time, (4) pinpoint the dominant and emerging research themes in CSR and sustainability communication literature, and (5) identify gaps in the current literature that present opportunities for future research in sustainability disclosures. This research aims to contribute not only to the academic intersection of CSR, communication theory, and sustainability but also in offering insights for firms seeking to enhance the effectiveness and transparency of their CSR disclosures in this steadfast digital and accountability-focused environment. In addition, this study introduces a new theoretical framework that offers explanatory insights into the changing nature of CSR communication.

Our paper is structured as follows. In the next section, we provide a thematic review of research on CSR and sustainability, including disclosures associated with this critical strategic activity. We then describe our systematic literature review research methodology, which utilized bibliometric analysis. Following an overview of the results, the paper closes with a discussion on CSR disclosure indicator metrics and the importance of this research to both the academic and practitioner communities.

2. Understanding CSR and Its Evolution

CSR is crucial for businesses because it drives consumer choice and is integral to business operations. CSR originated in the late 1800s from concepts about philanthropy by firms or the tycoons who ran them to address improved working conditions, laying the foundation for responsible corporations [

13]. However, it was not until American economist Howard Bowen’s 1953 book

Social Responsibilities of the Businessman that the phrase “corporate social responsibility” was used. In this work, Ref. [

14] acknowledged companies’ enormous influence over society and the concrete effects of their decisions. As a result, he contended, businesspeople must support laws that advance the welfare of society.

During the 1960s to 1980s, CSR expanded its scope to focus on broader corporate responsibilities beyond philanthropy. This resulted from an effort to mitigate the growing frequency of social protests brought about by corporate scandals and wrongdoings highlighting socially irresponsible behavior. This body of research is exemplified by the work of [

15]. The outcome of that literature review was to identify different stakeholders involved in CSR initiatives. This trend expanded through the 1990s as scholars further elucidated different social responsibilities or duties for CSR implementation. For example, Ref. [

16] proposed the CSR pyramid, which categorizes four key societal responsibilities for corporations to consider when adopting CSR: economic, legal, ethical, and charitable tasks. The stakeholder approach reinforced the principle that businesses must prioritize stakeholders’ interests, needs, and expectations in their CSR strategies [

17].

The start of the new millennium marked a significant turning point in CSR through the inclusion of sustainable development. Embracing “sustainability” [

15], this stage acknowledged that sustainability is becoming critical in business operations by going far beyond a business corporation and its stakeholders to include the global responsibilities of governments, international and community organizations, and global citizens [

15]. Sustainability refers to the capacity to maintain and support initiatives over the long-term, ensuring lasting impact. Incorporating sustainability concepts into CSR has become imperative for organizations, given the pressures they face to address global challenges like resource depletion and climate change [

8].

In response to global environmental challenges, corporations are adopting sustainability initiatives to minimize their ecological footprint. Environmental sustainability has thus emerged as a cornerstone of CSR, reflecting an understanding of the connection between firm operations and the health of the world [

11].

Correspondingly, CSR has evolved from primarily philanthropic and compliance-forced approaches (CSR 1.0) to a more strategic and transformative model (CSR 3.0). This new approach emphasizes co-creation with stakeholders, systemic thinking, and regenerative value creation [

18]. This transformation highlights a deeper integration of sustainability into corporate strategies, positioning responsibility as a core component for long-term value, rather than a secondary consideration [

19]. The Triple Bottom Line (TBL) framework [

20] supports this idea by promoting a balance between social equity (people), environmental stewardship (planet), and economic profitability (profit). Furthermore, the rise of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) metrics reflects a shift from narrative-driven corporate social responsibility to standardized disclosure-focused indicators [

21], aligning corporate accountability with market expectations. Together, CSR 3.0, TBL, and ESG have been instrumental in offering a bridge between sustainability and CSR. Today, sustainability is central to corporate performance and strategy.

Integrating sustainability into CSR expands the CSR concept to explicitly consider organizational effectiveness and profitability. Ref. [

2], for example, posited that adopting sustainable practices that minimize waste production, support renewable energy sources, and reduce carbon emissions can not only improve the environment but also reduce costs and improve a firm’s reputation [

9]. Similarly, today’s CSR now includes a broader commitment to social impacts [

22] by actively contributing to community and societal well-being. The awareness that responsible corporate sustainability practices go hand in hand with long-term profitability is therefore another important transition in the evolution of CSR [

23].

Companies have progressively recognized CSR as an inherent element of their core values and identity, rather than a secondary or optional activity [

24]. This shift in perspective is prompted not just by a sense of moral obligation but also by the knowledge that corporations are inextricably linked to the communities in which they operate. As a result, incorporating CSR into core principles is a strategic requirement for retaining relevance and resilience in a quickly changing environment [

13]. Sustainability initiatives, which include fair labor practices, transparent governance frameworks, and ethical sourcing, are now a cornerstone of CSR [

25]. This includes ensuring that business operations comply with justice, honesty, and accountability values.

In sum, the CSR concept has matured significantly over the decades. As a critical organizational activity, it has expanded beyond its charity origins, becoming a complete framework encompassing sustainable business practices, environmental stewardship, and a dedication to making a positive societal impact, including conceptions of organizational success [

22]. Embedding sustainability strategies into CSR aims to simultaneously improve society and enhance organizational performance.

3. Public Disclosures as a Component of CSR

Corresponding to the integration of sustainability into CSR, reporting about CSR has gained significant momentum in the business world. Before practices shifted towards increasingly standardized CSR reports, firms published standalone documents that were different from what we see today (e.g.,

Nike Corporate Responsibility Report 1998;

Coca-Cola Annual Report 2004). Early reports highlighted corporate practices on human rights, labor conditions, and environmental protection. CSR highlights were described in annual reports to increase transparency regarding their social and environmental effects [

26]. However, early CSR reports often lacked consistency and comparability, leading to concerns that such reports were little more than marketing and branding initiatives [

27]. In response, new reporting structures and regulations are rapidly emerging, such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and the Climate Change Disclosure Project (Carbon Disclosure Project), providing standardized frameworks for reporting on CSR and sustainability performance.

Much of the impetus for these changes is because of a growing focus on “double materiality”. Companies not only analyze how sustainability issues affect them (i.e., materiality) but also how the firm’s actions impact society and the environment. In response, various reporting frameworks have been created to guide what companies should share about social and environmental issues. For example, the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) offers global guidelines for sustainability reporting. These standards are optional, but can be adopted through national and local policies attempting to standardize what information is communicated to stakeholders. Nations like Brazil, Australia, Canada, Japan, Brunei, and members of ASEAN, for example, adopted global frameworks in their reporting requirements.

One striking example of this development is the European Union’s Non-Financial Reporting Directive requiring large public companies to report on their social and environmental impact. China is also implementing stricter policies. Starting in 2026, companies on major Chinese stock indexes and those listed both in China and overseas must report their ESG data, as required by the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC). In the U.S., the SEC created climate disclosure rules, but their implementation is unlikely in the near term because of political and ideological opposition from legislators.

Overall, global standards are increasingly shaping how companies report on CSR and sustainability. These rules help investors make better decisions, improve transparency, and encourage companies to act more sustainably. Digital innovations (e.g., big data, AI, blockchain, etc.) are also reshaping CSR communications, particularly in the context of digital sustainability [

2,

28]. As a result, CSR is becoming more formal, shaped by laws, company policies, and social expectations. Research on CSR and sustainability reporting has focused largely on frameworks and emerging trends related to stakeholder interests [

29].

Just as scholarly attention is focused in developments in CSR and reporting, companies have increasingly sought to implement CSR strategies that engage directly with stakeholders. Advancements in CSR reporting stem from growing consumer demand for transparency, investor awareness of ESG risks and opportunities, and government-mandated reporting requirements. Firms are thus responding to mandatory and voluntary reporting regimes emerging in many nations along with pressure from key constituencies.

In sum, just as CSR has matured to integrate social and environmental sustainability initiatives, so too has reporting about these important activities. CSR and sustainability reporting is evolving in exciting new directions. This affords us the opportunity to explore research on how this important topic has evolved and to identify trends in promising future avenues of inquiry. Research in this domain will help bridge gaps in the field and contribute to broader discussions on sustainability, governance, and social impact.

5. Methodology

We used a systematic literature review [

30] and bibliometric analysis [

31,

32] to examine the evolution of CSR reporting within a sustainability context. Our purpose was not just to describe the status of a research domain, but to shed light on patterns that can guide future research [

33,

34]. We retrieved data from Scopus and Web of Science. They were chosen for their comprehensive coverage of scientific literature and robust analytical tools. Understanding the distinctions between their indexing scopes (Web of Science emphasizes high-impact journals versus Scopus’s broad coverage of conference proceedings), we utilized these complementary sources to increase representativeness and reduce thematic skew [

35].

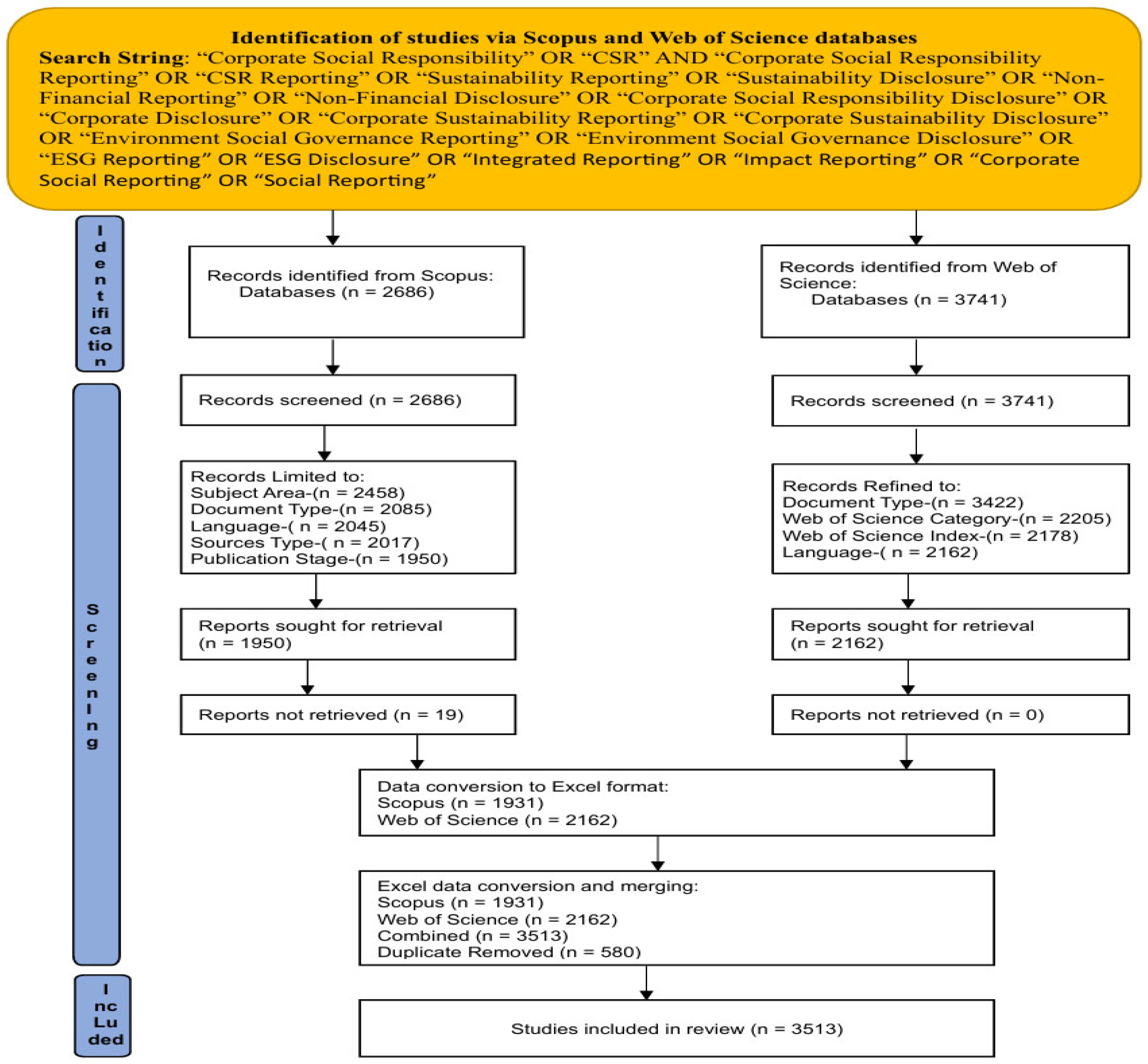

To avoid bias and capture diverse terminology related to CSR reporting and disclosure, we conducted a prior terminology test and later employed a broad search strategy, focusing on prevalent terms in the literature. We used Boolean operators (“AND” and “OR”) to refine the search within the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) framework. Our search identified documents in Scopus and Web of Science published from 1984 to 2024. The first year, 1984, was chosen because the inaugural paper about CSR and CSR disclosures was published that year.

We searched for documents on Scopus based on article titles, abstracts, and keywords, identifying 2686 documents, and applied filters to narrow our sample of published articles in this field. We filtered documents by subject area, including business, management, accounting, social science, economics, econometrics, and finance, reducing the sample to 2458 records. Secondly, we limited the document type to articles and review articles, narrowing our documents to 2085. Thirdly, we limited the language to English, further reducing our sample to 2041 documents. We also limited the source type to journals, which reduced the sample to 2017 documents, and publication stage to final to ensure we eliminated unpublished research, reducing our sample by 67 documents. As a result, we exported 1950 documents. Similarly, we searched the Web of Science for documents in all fields, identifying 3741 documents. We applied filters and refined by document type for articles and review articles, which reduced our sample to 3422 documents. Next, we applied the Web of Science category filter, refining research to business, management, business finance, social science, economics, and multidisciplinary sciences, reducing the sample to 2205 documents. We also limited the Web of Science Index to Social Science Citation Index and Science Index Expanded journals, further reducing the sample to 2178 documents. Lastly, we refined the language to English, reducing the sample to 2162 documents. These 2162 documents were exported.

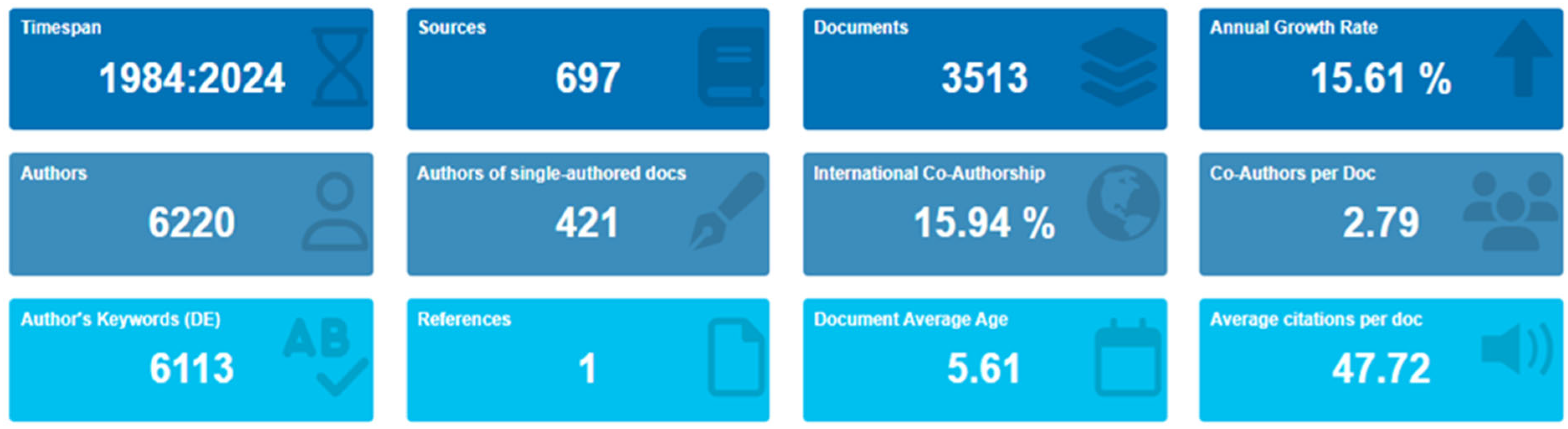

To alleviate bias in literature coverage between Scopus and Web of Science, files were merged using Biblioshiny R-Package version 4.3.1 for deduplication and data consolidation using conversion, merging, and save-file codes (conversion and merge: Combine<-MergeDbsources= (filename, filename, remove.duplicates = True; save newfile; Write.xlsx (combined, file= “new filename”)). Our conversion process to Excel files resulted in 1931 papers from Scopus, excluding 19 documents with missing information, and 2162 papers from Web of Science. The combination of Scopus and Web of Science resulted in 4093 documents in total. Removing 580 duplicates resulted in our final sample consisting of 3513 papers that were exported for analysis. This large sample allowed us to trace patterns and the evolution of various trends, themes, and intellectual structures, and to identify research gaps [

33] in CSR and CSR communication literature.

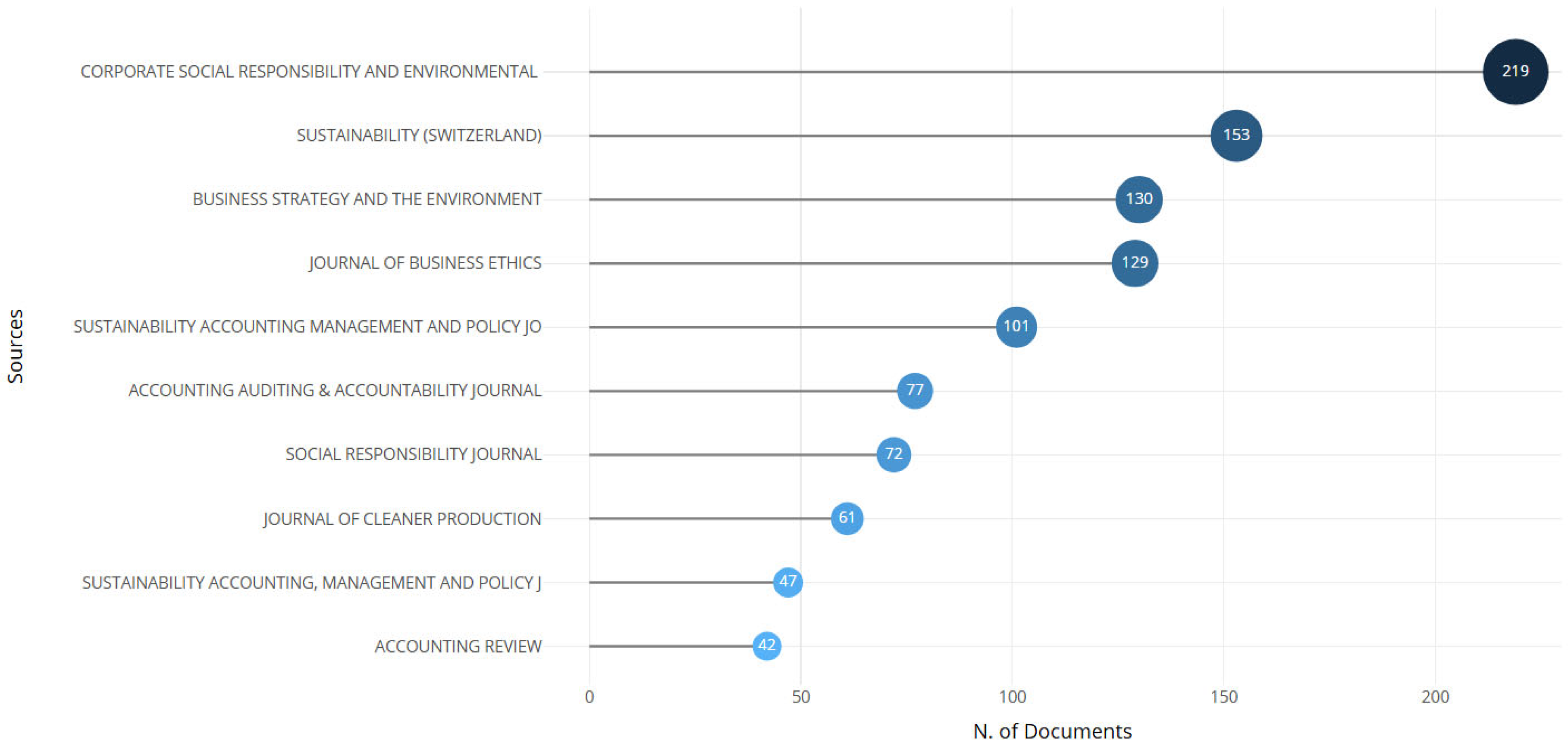

To ensure the academic rigor of the sample, we assessed the distribution of articles across journal quality tiers. Approximately 73% of the publications in our sample are from journals rated 3 stars and above in the ABS Academic Journal Guide, and high-impact journals constituted most of our core sample. Representative journals included

Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management,

Sustainability (Switzerland),

Business Strategy and the Environment,

Journal of Business Ethics,

Sustainability Accounting,

Management and Policy Journal, etc.

Figure 1 below identifies the rank ordering of the top ten journals represented in our sample.

We relied on Excel and the Biblioshiny R-Package [

34] for analysis because they streamline the Bibliometrix analysis, making it easier and more accessible for researchers and non-coders to navigate.

Figure 2 illustrates the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram, outlining the data extraction process and ensuring quality control.

7. Discussion

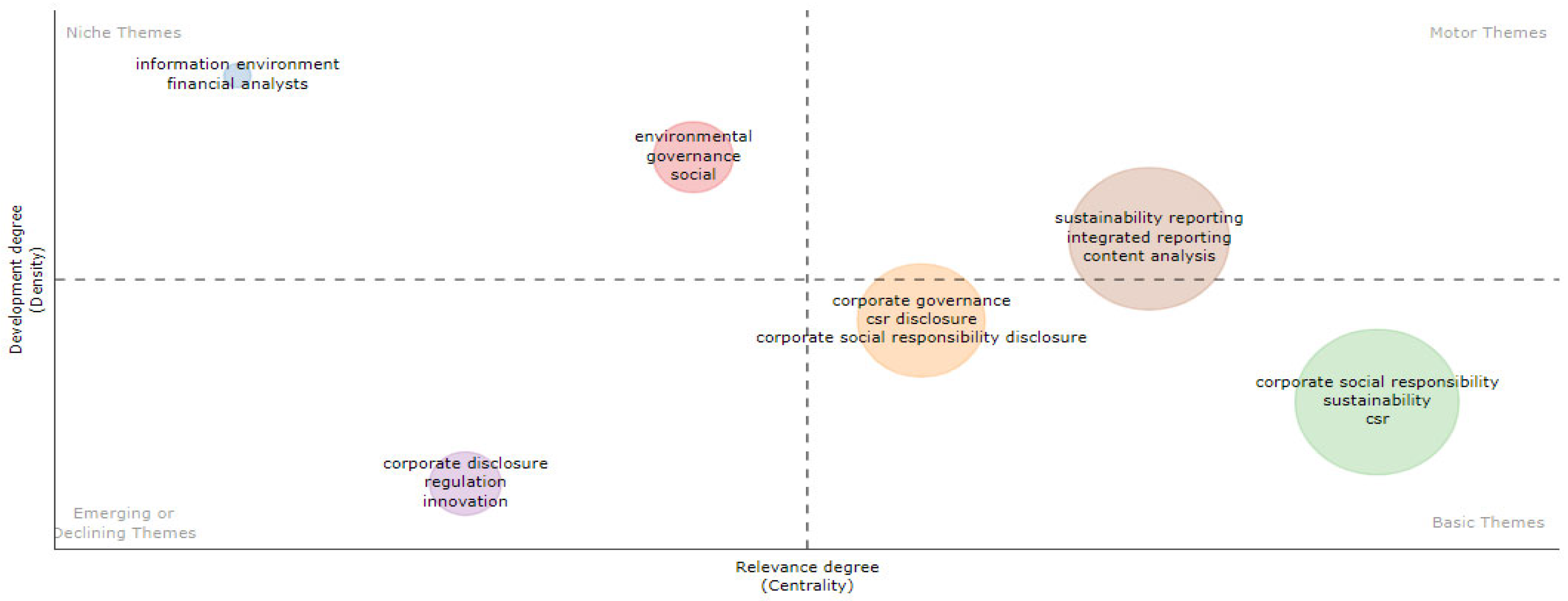

Our study exposes several interesting trends in the dynamic literature on CSR and CSR disclosure. In this final section, we discuss the results of the thematic map and evolution. Our discussion includes opportunities for future research and implications for CSR professionals. We have focused our discussion on the research questions presented at the beginning of our paper.

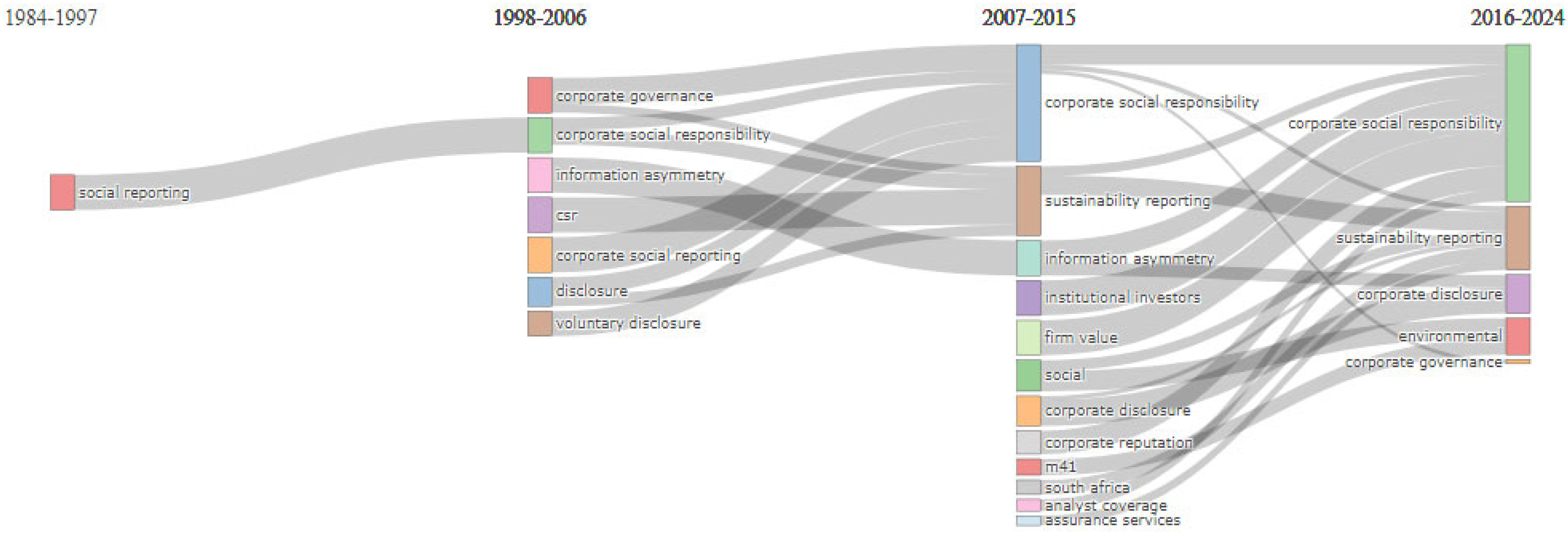

Our bibliometric thematic analysis and review of literature on CSR and CSR communications revealed 3513 publications from 1984 to 2024 written by 6220 authors from 697 different sources, exhibiting an annual growth rate of over 15%. In this study, we defined foundational concepts as trend topics that help create the theoretical and strategic framework that have shaped the practice of CSR and communications over time. The concepts noted are quality of life, social indicators, stakeholder analysis, triple bottom line, risk management, corporate image, legitimacy theory, corporate communications, annual reports, assurance, stakeholders theory, social accounting, environmental reporting, financial reporting, corporate social reporting, GRI, integrated reporting, sustainability, financial performance, sustainability reporting, disclosure, SDGs, firm value, non-financial reporting, ESG disclosure, ESG, corporate social responsibility disclosure, machine learning, and corporate social responsibility assurance.

This trend exhibited that CSR communication was rooted in philanthropic narratives, but evolved towards sustainability reporting, ESG metrics, and stakeholder engagement, reflecting a shift from a normative to a strategic framework. Also, recent literature further reveals that the COVID-19 pandemic acted as a catalyst for a profound transformation in CSR practices, driving firms to align more closely with the SDGs. Ref. [

68] highlights a notable increase in consumer scrutiny of CSR disclosures, with CEO communications becoming pivotal for maintaining stakeholder trust during crises. In parallel, social and environmental priorities, particularly climate change and health equity, have gained prominence within corporate strategies. Ref. [

69] underscore the elevated importance of the social dimension in ESG metrics, advocating for a comprehensive redesign of the CSR framework to meet evolving societal expectations. Ref. [

70] further observes a decisive shift toward inclusive, SDG-integrated practices that reflect corporations’ broader accountability to global challenges. It is clear to us that this research stream is complex and is rapidly developing. Just as businesses have embraced sustainable practices within CSR, research has followed suit. We expect the trend to continue because of heightened global environmental awareness and the resulting societal push for businesses to adopt sustainable practices.

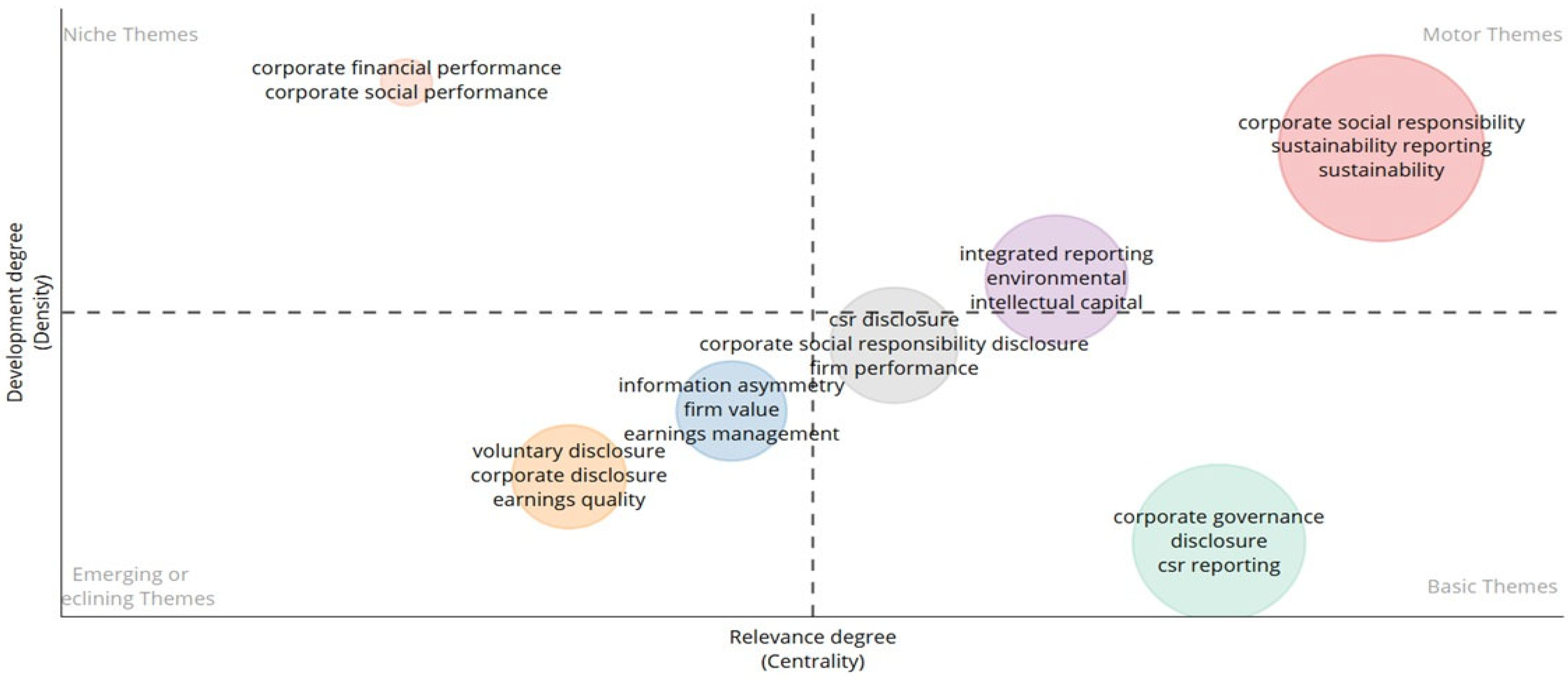

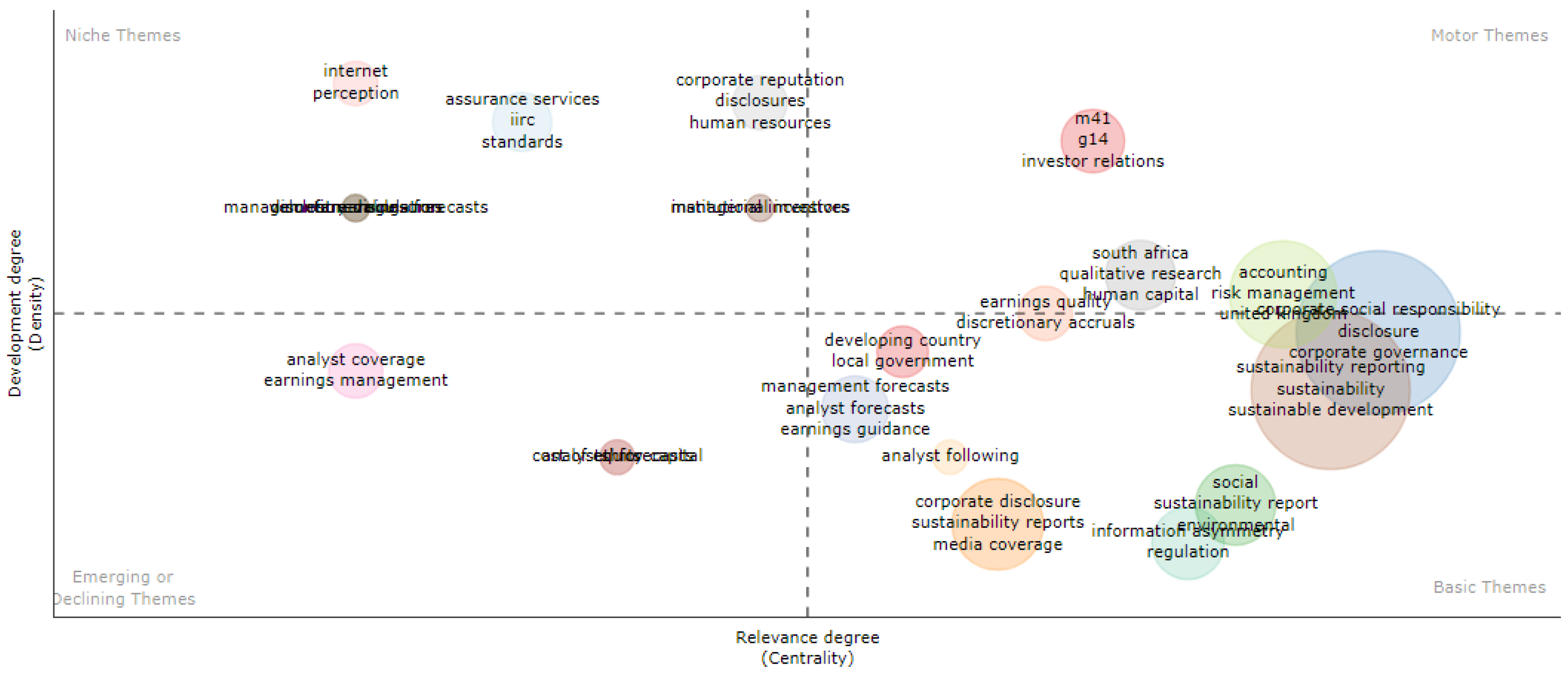

Our analysis included a detailed review of the prevailing themes that are prevalent in CSR and disclosure research. While we cannot offer prescriptions about how CSR and disclosure impact firm strategy and performance, as that was outside the scope of our research, we can review patterns in research themes determined by keyword usage. Evolving themes are indicative of changes in firm behaviors associated with CSR and disclosure. For example, our data suggest that CSR initiatives, communicated in conjunction with sustainability metrics, are viewed as an opportunity for firms to enhance societal and environmental impact and concurrently to improve their overall performance and reputation. To be clear, our data do not allow us to make causal statements; however, it is evident to us that scholars are increasingly exploring connections among CSR, disclosure, governance practices, and firm outcomes such as performance and reputation. This is highly suggestive that the links are present and scholars are responding by exploring nuances and patterns.

Our data also suggest that research is rapidly moving not just toward increased disclosure, but with a focus on communication transparency. For example, we detected an increased research focus on the inclusion of CSR activities in integrated reporting. This is possibly an institutional response by executives to move away from publishing standalone CSR reports and instead embed CSR into their annual reports. Unified, integrated reporting is not only efficient because it streamlines the reporting process, but it also helps ensure effectiveness through consistency in the messages that are being communicated and ultimately how stakeholders view CSR activity [

71]. That is, integrating CSR disclosure into integrated reports results in a clearer and more transparent view of firm operations (for example, Unilever’s integrated reporting practices). Following suit, academic research is likewise exploring integrated reporting.

Without interpretation, our results could be perceived as random trends. To help make sense of these important developments and to foster an understanding of the strategic implications of the seven thematic clusters identified in our research, we propose an analytical typology, depicted in

Table 1, that is based on two interpretive dimensions: stakeholder orientation (internal vs. external) and maturity level (low vs. high). This typology provides detailed analytical insights of CSR communication strategies and their alignment with broader corporate goals and stakeholder expectations. It also provides a valuable lens to understand how integrated reporting developed from its inception to ongoing maturation in corporate reporting practices. Below, we present the four quadrants and reporting examples, or topics, they include.

The first quadrant represents early-stage CSR efforts focused on internal stakeholders like employees and management. Disclosures at this stage are mainly about meeting compliance requirements and covering operational issues such as employee well-being, safety, and training. These efforts are often reactive and not yet aligned with broader sustainability goals. This stage reflects early CSR models based on corporate philanthropy and employee-related responsibilities, influenced by agency theory and basic risk management.

- 2.

Low Maturity (External Focus): Philanthropy and Community Engagement (Cluster B)

CSR disclosures in the second quadrant are outward facing, but remain low in strategic integration. Companies typically report on charitable contributions, community development projects, and ad hoc initiatives aimed at enhancing their reputation or responding to social expectations. These actions are often symbolic rather than systemic, reflecting a focus on legitimacy rather than embedding sustainability into core operations. Theoretical underpinnings include legitimacy theory and image theory, which suggest that businesses seek a social license to operate through visible though frequently superficial activities.

- 3.

High Maturity (Internal Focus): Integrated CSR Strategy (Cluster C)

The third quadrant suggests a shift toward the strategic internal integration of CSR. Organizations begin embedding sustainability principles into their operations through ESG-aligned systems, employee-led innovation, environmentally friendly production, and ethics-driven leadership. Disclosures in this quadrant reflect a proactive CSR approach focused on value creation and competitive advantage, rather than simple compliance. This stage aligns with the resource-based view (RBV) and stakeholder theory, highlighting the development of internal capabilities to support long-term sustainable performance.

- 4.

High Maturity (External Focus): ESG Risk Management and Ethics Disclosure (Cluster D)

In the fourth quadrant, disclosures are both strategic and outward facing, appearing to indicate a high level of CSR maturity. Companies provide comprehensive reporting on ESG risks, long-term societal impacts, and ethical performance. The disclosures in this cluster serve as accountability tools for investors, NGOs, and the wider public. There is a clear alignment with institutional theory and the triple-bottom-line approach, as firms pursue legitimacy, resilience, and strategic positioning within global sustainability landscapes.

This quadrant-based progression underscores the evolving nature of CSR, demonstrating how firms gradually transition from reactive, compliance-driven practices to strategically embedded sustainability efforts. The framework, grounded in an analytical typology of CSR disclosure metrics, merges conceptual clarity with practical applicability, offering a structured perspective for tracing the trajectory of organizations’ CSR disclosures. It illustrates how disclosure maturity and stakeholder orientation intersect to shape the depth and credibility of CSR communication. By categorizing disclosure patterns in this way, the analysis moves beyond treating CSR disclosures as uniform, revealing instead a progression from symbolic gestures to strategic actions and from isolated initiatives to integrated systems contingent on stakeholder expectations and organizational commitment.

This study contributes to the literature by linking the results of our bibliometric analysis to established organizational theories. The four strategic disclosure clusters identified in

Table 1 are not merely descriptive; they reflect deeper patterns that align with theoretical frameworks. Practices in cluster A (foundational disclosure) align with agency theory, which suggests that corporate motivations are often driven by control mechanisms embedded in regulatory frameworks. In this context, disclosure serves to mitigate risk through compliance. The emphasis on internal operations and employee development in this cluster indicates a lower level of maturity, given the limited scope of influence and the relative clarity of internal versus external activities. Cluster B (philanthropy and community engagement) reflects elements of legitimacy and image theories, where firms seek public approval by conforming to societal norms and expectations, particularly within communities adjacent to their operations. For instance, localized philanthropy is often used to demonstrate corporate citizenship. Reporting such actions can be instrumental in securing support for future expansion. Cluster C (integrated CSR strategy) is indicative of externally oriented organizational theories, including the resource-based view and stakeholder theory. Practices in this cluster demonstrate the strategic use of disclosure across the value chain to build stakeholder trust and achieve competitive advantage. Finally, cluster D (ESG risk management and ethical disclosure) represents highly mature practices that draw on institutional theory and signaling theory. These disclosures aim to build legitimacy through alignment with widely accepted external frameworks, such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Similarly, firms may report ESG ratings issued by independent organizations to reinforce their commitment to responsible practices and enhance perceived trustworthiness. Thus, a key academic contribution of the model presented in

Table 1 is the application of well-established organizational theories to explain the patterns and shifts observed in our data: from predominantly symbolic CSR reports prior to 2006 to more structured, stakeholder-focused ESG reporting in recent years. This evolution reflects increasing pressure from institutions, markets, and society, as well as the growing need for companies to signal their credibility and long-term value. By grounding these developments in theory, our study moves beyond a descriptive account of trends to offer explanatory insights into the changing nature of CSR communication.

Our findings also have practical significance for executives who are actively involved with developing integrated reporting. As with many aspects of sustainability, professionals in the field are increasingly becoming more strategic in their outlooks and practices associated with integrated reporting. Fortunately, a number of resources provide guidance in the form of prescriptions, or roadmaps, that executives can draw on for best practices about frameworks (i.e., what to measure, such as the United Nations’ SDGs) and standards (i.e., how to measure, including metrics such as the GRI). For example, many consulting companies have developed expertise in helping firms create materiality assessment programs that engage stakeholders in identifying critical sustainability issues. Further, SASB, under the responsibility of the IFRS Foundation, identifies industry-specific disclosure topics and standards for reporting. Thus, while the landscape associated with integrated reporting is complex, there is an increasing array of resources available to assist practitioners with developing comprehensive integrated reports.

We also recognize that engaging with stakeholders about material sustainability issues is likely to reveal differentiated expectations among them. Customers may prioritize data about product safety issues, investors might demand the company’s ESG ratings, employees may value data about the firm’s inclusion programs, and communities might seek information about environmental practices. Managing different priorities across stakeholders is an important leadership skill. Thus, while prescriptive guidelines abound regarding collecting stakeholder input, managing these differentiated expectations is also an important element to consider when crafting integrated corporate communications about CSR and sustainability.

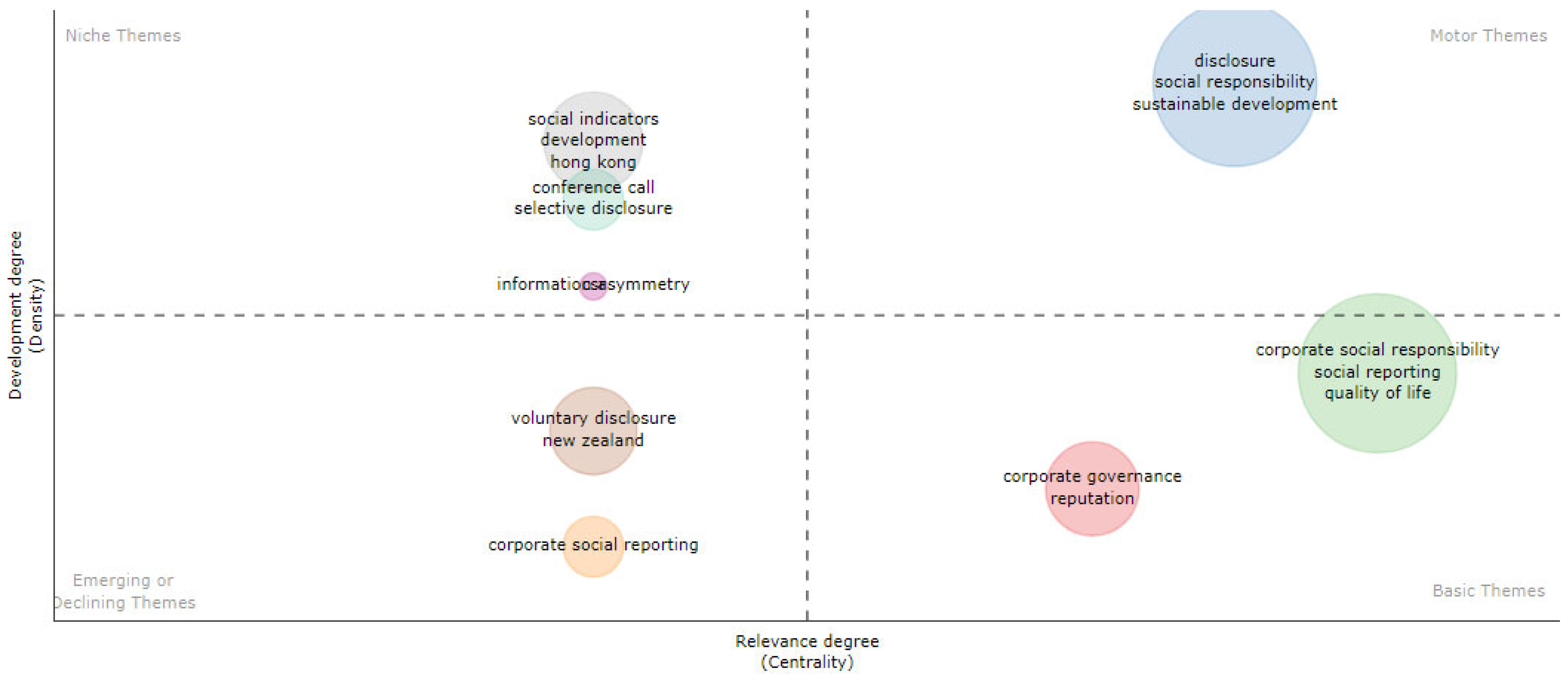

The thematic evolution map afforded us the opportunity to observe how rapidly the research appears to be maturing. As reported, just one theme predominated in the first time frame we reviewed (1984 to 1987). That number increased substantially such that by 2007 to 2015, we detected 12 clusters. These included conventional themes such as CSR and sustainability reporting. However, other niche themes included “analyst coverage,” “assurance services,” and “institutional investors.” In the last stage (2016 to 2024), however, the number of clusters was reduced to just five, representing a more concentrated range of mainstream themes, such as corporate disclosure, corporate governance, and sustainability reporting, in addition to CSR. In essence, examining research spanning four decades allowed us to observe stages of a research stream life cycle, including birth, growth, and maturation phases. Does this imply CSR and disclosure research is headed for decline? While that is beyond the focus of this study, we anticipate that practitioners doing the hard work in CSR and building increased transparency in disclosure will be largely responsible for the next frontier in academic research. The sustainability and CSR spaces are moving quickly due to heightened awareness of complex social and environmental challenges. As firms find tools allowing them to use their resources and capabilities to address these issues, we fully expect researchers to follow suit, seeking to identify significant patterns of relationships that will in turn inform the work of sustainability professionals.

While the number of themes had consolidated by the final phase of our research, that same phase (2016–2024) marked the period with the highest number of publications. We believe interpreting why this happened can be accomplished by examining key activities and events playing out in society. We expect one reason for increased interest in CSR and disclosure to be the introduction of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The 17 goals span a time frame from 2015 to 2030. The framework has become widely recognized as a gold standard by governments, NGOs, educational institutions, and companies alike. Just as sustainability professionals have tapped into the SDG framework to operationalize their CSR and sustainability platforms, overall research interest in this field has rapidly expanded.

Beyond pan-governmental work by the United Nations, public policy within nations has and will continue to impact the work of CSR professionals and their communications. For example, India’s CSR Mandate, reporting requirements in the European Union, and similar advancements in China and the United States will shape how companies report CSR initiatives and present new opportunities for academic research.

Growth in scholarly attention could also be attributable to the prevalence of practicing sustainability professionals to link ESG into CSR and sustainability. Both in the financial sector and the political environment, attention to ESG is expanding. Firms increasingly recognize the material impacts of ESG factors on long-term viability and have directed strategies to mitigate risks associated with environmental, social, and governance factors [

72]. Dating back to the United Nations Global Compact’s publication of

Who Cares Wins in 2004, ESG has become mainstream in CSR work and firm disclosures. Correspondingly, themes associated with ESG and its components are of heightened research interest among academics, and we expect this trend to continue.

Last, developments associated with CSR are geared toward a wide range of exciting new developments, including biomimicry and the circular economy, sustainable finance (both corporate and personal), and responsible innovations. This maturation in themes reflects a shift from basic concepts of social reporting to more complex, integrated, and strategic approaches. This highlights the growing recognition of CSR as a critical component of business success and sustainability in the modern world and the need for comprehensive reporting frameworks.

Many of the insights for this research question have been addressed relative to the thematic evolution just discussed. An additional noteworthy theme we observed focused on the intersection between transparency and its value to stakeholders and the temptation for some firms to greenwash. Indeed, academic research included in our sample explored issues such as how firms enhance “earnings quality”, that is, how they use messaging strategies to manipulate stakeholders’ interpretations of CSR activities and their effects. While disclosure is especially apparent in the research we reviewed, we also detected niche research on the harmful impacts of nefarious disclosures.

Likewise, an emerging theme we detected was associated with strategies aimed at mitigating information asymmetry to enhance firm value. Central to the agency theory literature, some executives have strategically used information to benefit themselves personally. Temptations also exist within CSR and CSR disclosure practices. Executives may engage in opportunistic behavior by portraying their firms as highly ethical, often through the promotion of awards and recognitions, while underlying sustainability challenges remain unaddressed. For instance, a fashion company might highlight its use of sustainably sourced materials, but omit discussion of human rights issues within its supply chain. Similarly, a beverage company may emphasize efforts to reduce single-use plastics while avoiding conversations about the health impacts of its products.

Heightened attention by scholars on transparency issues like these provide reaffirmation that in contrast to earnings management, greater transparency and disclosure lead to better financial reporting, reduced risks, and stronger firm valuation. We anticipate that information asymmetry, disclosure, and firm value will remain stakeholders’ fundamental and forward-looking concerns within corporate activities and will simultaneously be reflected in future academic research. Further, we expect how corporates are engaging in CSR activities at the potential detriment of investors and the resulting need for the use of integrative reporting frameworks to be emerging areas of attention.

The current research on CSR and CSR communication is centered on CSR, sustainability, environment, sustainability reporting, integrated reporting, ESG disclosure, and machine learning, indicating the ongoing relevance of research and practice. Based on trends in sustainability and CSR practice, we anticipate that CSR and CSR communications will evidence greater integration with technology, enhanced stakeholder engagement, a shift to a more preventive approach to material risks such as corruption in developing economies, and a strong focus on addressing global challenges such as climate change, social equity, and human rights. For example, exciting new research is evolving about different opportunities to integrate carbon mitigation into core business strategy, shifting CSR from a peripheral concern to a strategic imperative. Innovations such as regenerative agriculture [

73], embedded CSR communication [

74], digital reporting [

75], stakeholder-centric multi-channel engagement [

76], and data-driven ESG frameworks [

77] are reshaping the landscape. Cultural and institutional context [

74] and theory-driven insights [

78] further strengthen this transformation. CSR communication today is not about what is reported, but “how” and “why,” emphasizing purpose, transparency, and stakeholder value. This evolution suggests that firms, especially in the container-packing food industry, will increasingly disclose sustainable supply chain practices, such as no-till farming. Ultimately. CSR reporting is transitioning from compliance to strategic storytelling anchored in values, driven by data, and designed to create lasting social and environmental impact.

Firms are becoming more proactive and innovative in their communications, leveraging new technologies and approaches to meet the evolving expectations of stakeholders, regulators, and investors. Likewise, we anticipate that academic research will follow suit. However, it is important to note that while we focused on business in the broad sense, considerable opportunities lie in future research that is tailored to specific industries, businesses, and cultural contexts [

8]. This will advance the field from a coarse understanding of CSR and CSR communication toward more fine-grained applications.

Our final implication for both CSR practitioners and academic researchers is associated with one of our research limitations identified below. Our thematic analysis required us to identify key terms for content analysis. The need to put order and simplification on research streams could have resulted in unwittingly missing important terms. Correspondingly, the nomenclature associated with CSR in the professional world is becoming complex and nuanced at best and fuzzy or ambiguous at worst. Whereas professionals once focused efforts on CSR, their roles now touch on CSR, sustainability, ESG, impact, and corporate citizenship. Are these terms the same? If they are distinct, how? When one firm produces an impact report, another an ESG report, another a sustainability report, and another a CSR report, are they disclosing the same types of information to their stakeholders? How the shakeout in terminology will unfold is uncertain, but if the goal is increased transparency in disclosures associated with CSR, the hope is that professionals and academics will coalesce on common terms.