Abstract

This research examined the persuasive impact of social norms and financial incentive messaging for encouraging reusable bag use. In an online experiment with a nationally representative sample from the U.S. (n = 753), participants were randomly exposed to static or dynamic descriptive/injunctive norms, discounts/surcharges, combinations, or a control message. Intentions to bring reusable bags when grocery shopping, along with other key demographic and psychological variables, were assessed. ANCOVA results demonstrate the main effects of the messages. Planned contrasts revealed that injunctive norms elicited higher intentions than descriptive norms. Dynamic descriptive norms led to stronger intentions compared to static descriptive norms, with no difference shown between the two injunctive norm conditions. Notably, combining injunctive norms with either incentive boosted intentions beyond standalone messaging, supporting motivational complementarity. Norms overall outperformed incentives, but integrating social and economic appeals shows promise. The predicted superiority of experimental messages in promoting intentions, when compared to a generic pro-environmental appeal (control), was not supported. The findings advance an integrated behavior change approach highlighting normative information and incentives, shedding light on optimal messaging strategies amid pro-environmental interventions.

1. Introduction

The proliferation and widespread usage of plastic bags have posed a major threat to environmental sustainability. Approximately 5 trillion plastic bags are consumed worldwide each year, equating to almost 10 million bags used per minute [1]. The seeming benefits of cheap cost, convenience, and durability are outweighed by the massive amount of plastic pollution generated—around 300 million metric tons yearly, with only 9% recycled [2]. The overwhelming majority of plastic waste, laden with toxic chemicals like BPA, phthalates, and heavy metals, accumulates in landfills, ecosystems, and the ocean, posing significant threats to both human and wildlife health [3].

The harms that plastic bags impose demonstrate an urgent need for sustainable alternatives to protect ecological and public health, as well as address the issue of social and environmental justice [3,4]. As such, using a nationally representative sample from the U.S., this paper examines two viable strategies: social nudges, or social norms appeals, and economic levers, specifically financial incentives. Both interventions show promise for reducing plastic bag usage and promoting sustainable alternatives [5,6], yet may operate through distinct motivational pathways [7].

Incentives directly affect behaviors but can also undermine intrinsic motivation and attenuate the impact of persuasive messaging [8]; social norms, conversely, tap into people’s innate motivations for conformity and alignment with community expectations [9]. Consequently, incentives may successfully spur short-term behavioral change, but norm appeals may more profoundly transform and/or reinforce long-term attitudes and behaviors related to sustainability [6,10]. Given the scarcity of research and inconclusive findings in the existing literature, testing these approaches in parallel will elucidate both their standalone and synergistic effects on shifting behavioral outcomes.

Furthermore, limited experimental studies have tested different types of social norm appeals, static versus dynamic, in promoting reusable bags, especially alongside financial incentives. Static norms present established behavior prevalence and approval, while dynamic norms showcase growing social engagement and acceptance over time [11]. Static norm appeals provide a descriptive baseline, but dynamic norms highlighting positive momentum may be more motivational for not-yet-popular behaviors. Comparing these communication-based interventions, independently and jointly with incentives, can reveal their relative efficacy in driving durable change. The findings of this study will provide evidence to guide optimal messaging when leveraging norms and incentives and ultimately further long-term effective strategies for transitioning toward sustainable consumer practices.

1.1. Social Norms Appeals and Pro-Environmental Behaviors

1.1.1. Static Descriptive and Injunctive Norms

Social norms guide behaviors by revealing what is commonly done and socially approved/disapproved of in a given context [12]. Specifically, static descriptive norms convey the prevalence of a behavior within a group, indicating what is typical or normal, while injunctive norms assess whether a behavior meets social approval and/or deviates from social expectations by revealing standards of what behaviors people should or ought to perform [12].

Both norms facilitate collective cooperation, such as pro-environmental practices, while deterring selfish actions [13]. Static descriptive norms offer straightforward behavioral guidance by demonstrating common practices and showcasing what most people do to coordinate and cooperate. By simply following prevalent behaviors, individuals can effectively contribute to collective goals without analyzing complex group dynamics [14]. The heuristic information descriptive norms provide reveals optimal conduct as shown by others facing similar dilemmas, tapping into the wisdom of the crowd and steering cooperation through basic mimicry.

On the other hand, in situations where people must cooperate to achieve shared goals, such as environmental protection, static injunctive norms function through the threat of social disapproval and sanction, motivating individuals to act in the group’s interest, even at personal cost. Meanwhile, injunctive norms actively reward and validate actions demonstrating concern for collective well-being through social support and praise. In short, by leveraging prevalence, approval, disapproval, sanctions, and rewards, both descriptive and injunctive norms indicate cooperation as the more reputable and beneficial option over rational self-interest, making pro-environmental behaviors more susceptible to normative influence [15].

Consistent with this reasoning, the effects of static descriptive and injunctive norms were evident in studies on pro-environmental behaviors [16,17,18]. Specific to plastic avoidance, Borg et al. [19] examined the direct effects of both descriptive and injunctive norms on behavioral intentions to avoid single-use plastic with a random adult sample in Australia. Results show that while descriptive norms had stronger effects, both descriptive and injunctive norms are significantly related to behavioral intention to avoid using plastics (including plastic bags).

Moreover, a field study in the U.K. [16] tested the effects of normative messages (injunctive norms, personal norms, and a combination of both) with existing environmental messages, compared to environmental message-only conditions. The number of free plastic bags used by grocery shoppers was observed using a one-way between-subjects design. Injunctive norm messages included statements such as “Shoppers in this store believe that reusing shopping bags is a worthwhile way to help the environment. Please continue to reuse your bags” (p. 1837). Results reveal that shoppers exposed to injunctive, personal, or combined injunctive–personal norm messages used fewer free bags on average compared to environmental messages alone. Additionally, the effects of the combined messages did not significantly differ from the standalone normative messages.

In addition, the effectiveness of social norm appeals in changing resource consumption behaviors has been demonstrated in various other contexts [20,21,22,23]. Benedict and Hussein [24] examined water awareness campaigns in Jordan, analyzing how the Ministry of Water and Irrigation employed strategic messaging to shape citizens’ water conservation behaviors. Their study revealed how the government successfully created “responsible water citizens” (p. 1) by appealing to national responsibility and disseminating diverse awareness materials that connected personal water practices to broader societal benefits. While focused on water rather than plastic, their findings provide valuable insights into how well-designed awareness campaigns can transform social norms around resource usage through targeted messaging that aligns individual behaviors with collective goals. Overall, the empirical evidence underscores the potential of normative messages to promote sustainable behaviors among consumers.

Notably, to effectively guide behavior, static descriptive and injunctive norms should be made psychologically salient through situational cues rather than passively stored in memory, based on the Focus Theory of Normative Conduct [12]. Norms must be highlighted at the moment of action through timely messages embedded within the immediate context. This activation of relevant thoughts enhances normative influence, stemming from prominent accessibility to normative information rather than just general awareness [22].

This mechanism illustrates how norm appeals function by making social information available and salient when decisions occur. For instance, displaying reusable bag norm messages during grocery shopping activates shoppers’ perceptions of that norm when they choose their bags. While both norm types show promise, as reviewed above, few studies directly compared descriptive and injunctive appeals, especially in this context. Given the limited evidence, we proposed the following research question:

RQ1.

Which norm message exposure (static descriptive or injunctive) will lead to greater behavioral intentions of bringing reusable bags for grocery shopping?

1.1.2. Dynamic Descriptive and Injunctive Norms

As Rimal and Lapinski [25] conceptualized, norms evolve over time and contexts rather than remaining static. For plastic bags, the prevalent usage highlights the need for interventions catalyzing a normative shift from disposables toward sustainable alternatives such as reusables [6]. However, norms supporting anti-plastic behaviors remain unestablished and unclear among consumers, signaling room for substantial change [11]. As such, in addition to testing the effects of the static norm appeals discussed above, this study examines whether dynamic norms, which capture perceived changes in behaviors or social approval over time, can positively impact behavioral intentions despite prevailing disposable bag norms [26].

A dynamic descriptive norm reflects a growing prevalence of a behavior (e.g., “More and more people are bringing reusable bags for grocery shopping”), signaling change over time in what people do. In contrast, a dynamic injunctive norm captures a perceived change in what people approve of (e.g., “More and more people believe bringing reusable bags is the right thing to do”). This distinction parallels the well-established difference between static descriptive and injunctive norms [12], but with a temporal component added.

Despite being a relatively new concept, a handful of studies have illustrated the effects of dynamic descriptive norms on pro-environmental intentions. For example, Carfora et al. [27] conducted a one-month message intervention study through a chatbot to investigate the effectiveness of combining dynamic descriptive norm information (i.e., a growing number of people are acting pro-environmentally) with environmental information in messages aimed at reducing meat consumption. The results show that both types of messages, environmental information alone and environmental information combined with dynamic norm information, led to more positive attitudes towards reducing meat consumption and decreased meat consumption levels. Notably, these effects persisted even one month after the intervention ended.

In another study, Sparkman and Walton [11] conducted five experiments, including field studies, testing the effects of dynamic descriptive norms (i.e., changes in the prevalence of a behavior) and potential mediating processes across two contexts: meat consumption and water conservation. The field studies exposed participants to messages about the growing trend of reducing meat consumption and conserving water, which increased intentions and behaviors aligned with the trends. Additional experiments identified mediating mechanisms, showing dynamic descriptive norms as more influential when depicting increasing rather than stabilizing trends. The increasing trends heightened beliefs that more people would engage in that particular behavior, signaling its importance. Overall, the research concluded that dynamic norms highlighting growing prevalence can encourage pro-environmental transitions even when contrary static norms exist.

Similarly, Chung and Lapinski [5] tested the effectiveness of descriptive dynamic norm messages in two behavioral contexts (unplugging electronic devices and bringing reusable bags when grocery shopping). Using a 3 × 2 × 2 online experiment manipulating norm type (dynamic vs. low static vs. high static), group identity (low vs. high), and intention topics (bags vs. energy), they demonstrated that dynamic norms heightened perceptions of future behavior prevalence, which mediated normative effects on intentions. The 1-year and 5-year perceived future norm timespans affected bag versus energy intentions, respectively. A weak (but significant) moderating effect of group identity was found on the dynamic norm and behavioral intention relationship. Overall, the research provides additional evidence that descriptive dynamic norms can shift sustainable intentions, such as using reusable bags, through shaping perceptions of growing trends, though group identity may moderate the effects.

In contrast, dynamic injunctive norms remain underexamined, although emerging work, primarily in the context of health behaviors [28], supports their conceptual and practical relevance. The Canadian COVID-19 Experiences Project [29] offers rare empirical evidence by measuring individuals’ perceptions of how approval for vaccination changed over time among their close contacts. Results show that individuals who perceived growing approval among valued others were significantly more likely to transition from vaccine hesitancy to full vaccination. These findings suggest that dynamic injunctive norms, capturing changes in perceived social approval over time, can meaningfully influence health-related behavioral change, particularly in settings where behaviors are contested or evolving.

In the domain of environmental behaviors, although empirical research on dynamic injunctive norms remains scarce, there is a strong theoretical rationale to believe they may function similarly to dynamic descriptive norms. When individuals perceive that social approval for a behavior is increasing, they may feel both morally validated and socially supported in adopting that behavior, particularly in situations where existing behavioral norms (e.g., widespread plastic bag use) might otherwise discourage change. Just as dynamic descriptive norms convey that a behavior is gaining prevalence and social momentum, dynamic injunctive norms can signal a growing consensus about what should be done, reflecting a broader shift in collective values or expectations. This perceived rise in social approval may, in turn, reduce the psychological or social risks associated with breaking from established habits or norms.

Drawing upon both theoretical reasoning and emerging empirical insights, this study investigates how both dynamic descriptive and dynamic injunctive norms influence intentions to use reusable bags for grocery shopping, a behavior still challenged by the prevailing norm of plastic bag use. Prior research suggests that dynamic descriptive norms, which highlight a growing trend in behavior, can promote sustainable actions even when static norms signal low current adoption. Thus, we predict that dynamic descriptive norm messages emphasizing the increasing use of reusable bags will have a stronger positive impact on intentions than static descriptive messages, which may appear inconsistent with people’s everyday observations.

Meanwhile, we extend this line of inquiry by examining the persuasive potential of dynamic injunctive norms, which signal increasing social approval for a behavior over time. Although empirical evidence is scarce, theoretical perspectives suggest that perceived shifts in what others believe is “right” or “expected” may similarly drive intention formation, particularly when approval is seen as growing among personally relevant or important others (referent groups). By comparing the effects of dynamic descriptive versus dynamic injunctive norm messages, we aim to understand which type of normative change is more influential in shaping intentions (RQ2). Further, by testing whether a dynamic injunctive norm outperforms a static injunctive message, we assess whether perceptions of shifting social approval add persuasive value to injunctive appeals (RQ3). By testing both types of dynamic norms, this study aims to clarify their relative and distinct contributions to encouraging pro-environmental behavior in a context of weak or ambiguous normative support.

H1.

Compared to the static descriptive norm message, exposure to the dynamic descriptive norm message will lead to more behavioral intentions of bringing reusable bags among grocery shoppers.

RQ2.

Which dynamic norm message exposure (descriptive or injunctive) will lead to greater behavioral intentions of bringing reusable bags for grocery shopping?

RQ3.

Compared to the static injunctive norm message, will exposure to the dynamic injunctive norm message lead to more behavioral intentions of bringing reusable bags among grocery shoppers?

1.2. Financial Incentives and Pro-Environmental Behaviors

In addition to social norms, this study focuses on two financial incentives: discounts (for bringing a reusable bag) and surcharges (fees charged for using plastic bags). While a surcharge is typically seen as a financial disincentive, akin to a penalty designed to discourage undesired behavior, this study conceptualizes it as a form of incentive, aligning with previous research in this area [30]. In conjunction with discounts, both strategies operate as financial mechanisms to encourage the adoption of reusable bags among shoppers. Financial incentives have been widely adopted worldwide to deter plastic bag consumption, serving as an extrinsic motivator. Over 127 countries now implement some form of plastic bag charge [1], including point-of-sale fees per bag (surcharge), prepaid mandatory bag taxes, discounts, rebates, or subsidies for reusable bag use. Fee amounts vary greatly but often range from USD 0.10 to USD 0.25 per bag [31]. In the U.S., ordinances remain more localized to cities like San Francisco and Chicago, as only eight states currently have plastic bag bans or fee laws [32]. Generally, the U.S. lags behind many nations in utilizing financial incentives for reducing plastic bags, but momentum is building at the city and state levels as support grows for reducing plastic waste [33], presenting ample opportunity to further curb plastic waste with economic levers and social nudges.

The extant literature on financial incentives has shown a generally positive effect on reducing plastic bag use [34,35]. A field study in Argentina [7] examined the short and long-term impacts of a USD 0.025–USD 0.04 charge on single-use plastic bags by analyzing data before and after policy implementation, as well as from stores that adopted the charge later. About one month after the charge began, using one’s own bag increased significantly compared to stores without the fee. The increased use of reusable bags persisted over time and appeared in stores that implemented the charge subsequently. However, the study also found that own-bag use rose in areas without fees, implying additional factors that may further motivate change intrinsically.

Homonoff [36] compared the effects of a USD 0.05 plastic bag surcharge to a USD 0.05 reusable bag discount across grocery stores in Washington D.C., Montgomery County (MD), and northern Virginia. Using a mixed-methods approach, including surveys, observations, and transaction analysis, the study revealed that the surcharge significantly decreased disposable bag usage, while the reusable bag discount showed no notable impact compared to stores without incentives. Customers tended to use reusable bags more frequently with either surcharges or discounts than in stores with no incentives, but surcharges proved more effective. The study suggested that consumer responses were influenced by complex motivations, with loss aversion potentially contributing to the greater impact of surcharges over discounts. In summary, plastic bag fees were found to substantially alter behavior compared to reusable bag discounts.

Building upon established research supporting the use of incentives, particularly surcharges [37,38], in reducing plastic bag usage, the following hypothesis is proposed to replicate and extend prior findings, focusing on the effects of communication messages.

H2.

Exposure to a plastic bag surcharge message will lead to greater behavioral intentions of bringing reusable bags compared to a reusable bag discount message.

1.3. Social Norm Appeals and Financial Incentives

Lastly, a key element of this research involves assessing and comparing the persuasive efficacy of two widely used yet fundamentally distinct behavior change strategies: social norms appeals and financial incentives. While both have shown promise in encouraging pro-environmental behaviors, they operate through different psychological mechanisms: norms appeals leverage perceptions of behavioral prevalence and social expectation and approval, whereas incentives appeal to individual cost–benefit calculations. Despite their widespread use, there is surprisingly little empirical research directly comparing these approaches.

For instance, Pellerano et al. [39] examined the interplay between social norms and incentives but embedded incentives within norm-based messaging, leaving unclear how each strategy performs independently. As a result, important questions remain about their relative effectiveness in motivating consumers to shift from plastic to reusable bags. Understanding whether behavioral intentions are more strongly influenced by normative cues or financial motivators has direct implications for campaign design and policy development. To address this gap, we pose the following research question:

RQ4.

Which message exposure (norms vs. financial incentives) will lead to greater behavioral intentions of bringing reusable bags for grocery shopping?

In addition to evaluating their relative efficacy, exploring the potential synergies between social norms appeals and financial incentives holds both theoretical and practical significance in shaping pro-environmental intentions and behaviors. Findings will inform optimized integration of these motivators in developing strategic behavior change approaches amid undesirable plastic bagging norms. A particularly relevant and informative framework in this context is the Financial Incentives in Normative Systems (FINS) model, theorized by Lapinski et al. [10]. Grounded in theories of social norms and economic principles, the FINS model differentiates the influential mechanisms of descriptive norms from injunctive norms, providing insights into how monetary incentives interact with social norms and their enduring impact on pro-environmental behaviors, especially post-incentive cessation. Notably, both the FINS model and the existing literature primarily examine the interaction between financial incentives and static social norms, rather than dynamic norms. As an initial exploration in this field, we focused on testing the interactions between exposure to static norm messages and financial incentives for clarity and parsimony. This model not only explicates the intricate dynamics between economic motivations and social behaviors but also highlights their long-term implications for encouraging sustainable environmental practices.

A series of lab and field experiments [10,40] testing the FINS model show that (1) there is a short-term effect of financial incentives in promoting cooperative behaviors and (2) introducing and then withdrawing financial incentives can weaken descriptive norms and undermine subsequent behaviors, termed motivation crowding out. These findings are also supported by other studies. For example, Pellerano et al. [39] compared intrinsic (descriptive normative influence) and extrinsic incentive (economic-focused) messaging for reducing residential energy use in Ecuador using a field experiment. Some households received monthly normative feedback comparing their consumption to averages and similar households. Others received this along with financial incentive information. Results show that social norm-only messages reduced energy use versus no messages. However, combining norms and financial incentives was less effective than norms alone, suggesting that financial motivators may attenuate the impact of norm appeals in some environmental contexts, highlighting the need to explore these interactions.

In this study, a charge for using plastic bags serves as an extrinsic deterrent. However, there is a risk that this financial strategy may overshadow intrinsic motivations tied to environmental responsibility and social approval. Specifically, the surcharge might inadvertently justify the behavior of using plastic bags, thereby diminishing the influence of internal motivators to act pro-environmentally. In essence, the external incentive crowds out the intrinsic norm motivations, as individuals anchor on financial rewards over social outcomes.

Conversely, recent research suggests that surcharges can “leak” normative information and shape conformity. Lieberman et al. [30] found that a USD 0.10 bag surcharge increased perceived descriptive and injunctive norms and norm-related emotions compared to discounts, boosting reusable intentions. Serial mediation showed that the fee positively influenced norm perceptions, emotions, and mug use intentions. In a follow-up bag reuse study, the results demonstrate that the effects of surcharges may transfer to different locations where surcharge incentives were not in place. This indicates that fees can have a lasting normative impact through implied social cues, but individual differences moderate this influence. While not examining norm messaging explicitly, it provides initial evidence that combining incentives and norms may produce positive synergistic effects on pro-environmental intentions and behaviors, while more direct research is still needed in this area.

In a similar vein, FINS suggests that aligning incentives with social approval enhances the perception of behaviors as both prevalent and socially valued. This reinforcement, termed motivation crowding in [40], promotes sustained behavioral engagement even after incentives end. For instance, in their field experiment with Tibetan herders, Kerr et al. [40] framed a temporary payment for patrolling against wildlife poaching as validating traditional conservation values. This increased the perceived injunctive norms supporting such patrolling, which persisted post-payments.

In short, careful alignment of financial incentives with social motivations and norms, rather than relying on external regulations, potentially helps to avoid motivation crowding out and sustain behaviors over time. The crucial factor lies in highlighting behaviors as socially supported, extending beyond mere financial rewards. Given the mixed evidence on the synergic effects of social norm appeals and financial incentives, the following research question aims to scrutinize this issue:

RQ5.

Will integrated message exposure of social norms and financial incentives lead to stronger or weaker intentions of bringing reusable bags for grocery shopping compared to other standalone messages?

In summary, as reviewed above, extensive research demonstrates that social norms and financial incentives can independently and/or jointly encourage pro-environmental actions such as bringing reusable bags for grocery shopping [19]. These distinct mechanisms function via intrinsic and/or extrinsic motivations. Synthesizing the prior work, we predict that appealing to distinct motivational forces by showcasing social norms and financial incentive messages will increase reusable bag intentions relative to generic sustainability appeals alone (the control condition).

H3.

Both social norm messages and financial incentives will lead to a stronger intention of bringing reusable bags for grocery shopping, compared to the generic pro-environmental message.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

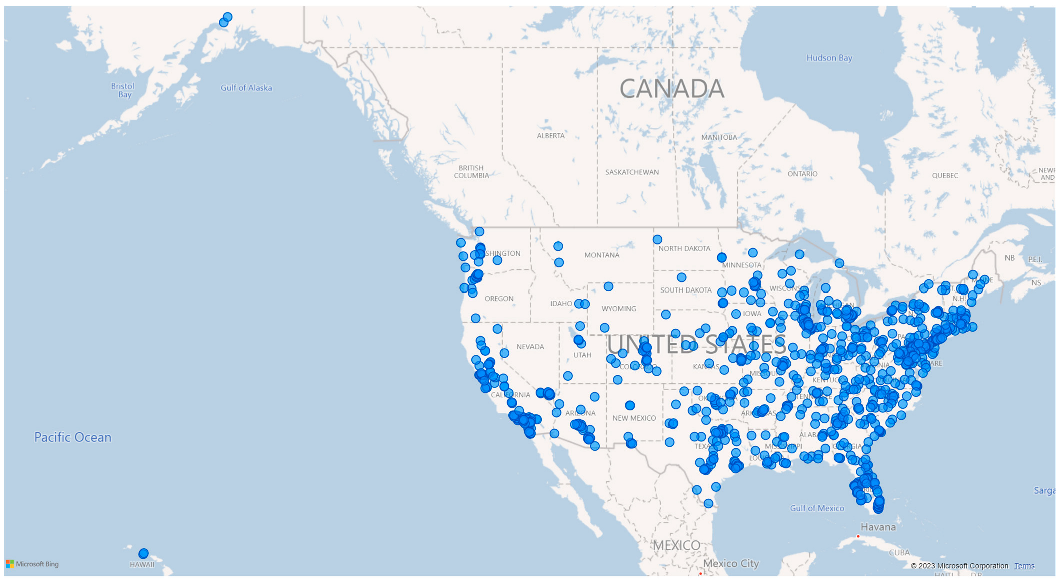

This study (n = 753) reported a subset of the data from a larger project. A nationally representative sample aligning with the most recent census data in the U.S. [41], including age groups, gender, race/ethnicity, and population density, was recruited through Qualtrics panels from all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the territory of Puerto Rico (see Appendix A for a map of data collection locations). To be eligible for this research, participants needed to be (1) 18 years or older and (2) shop for groceries in-store.

Participants, on average, were 49.34 years old (range: 18–93, SD = 18.27), with 52.7% females (census: 50.47%), 74.5% White/Caucasian (census: 75.5%), and 18.9% Hispanic/Latinos (census: 19.1%). Additional demographic data, including socioeconomic backgrounds, marital status, political ideologies, religious beliefs, and grocery shopping behaviors, are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and grocery shopping behaviors of participants.

The sample size was determined by a priori power analysis conducted using G*Power v3.1 [42], with the effect size f = 0.25 and the alpha value of 0.05 set based on meta-analyses on social norms messages [43] and research on dynamic norms [44] and financial incentives [30]. For 0.80 power, each experimental condition requires a sample size of 55 participants.

2.2. Research Design and Procedures

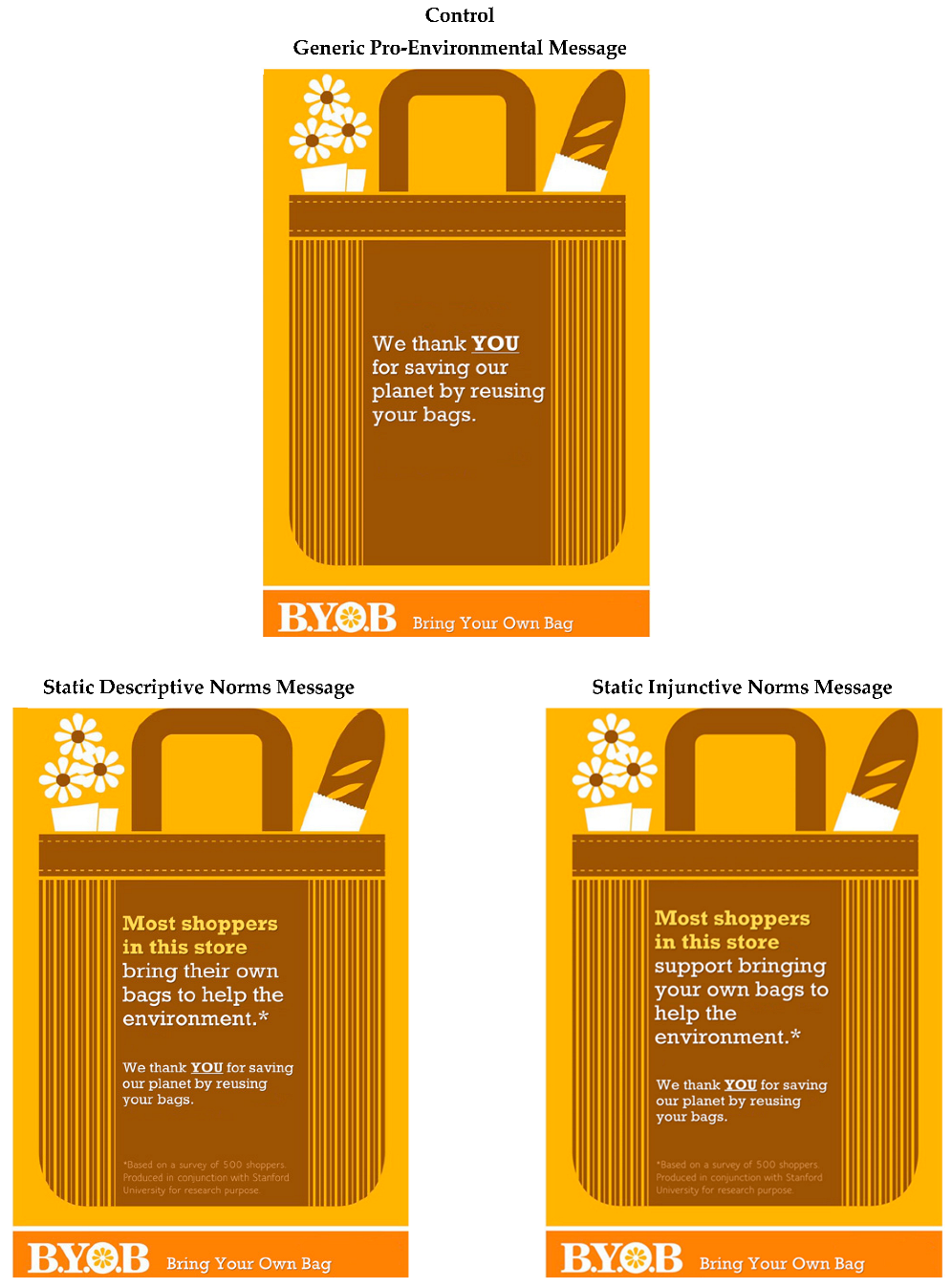

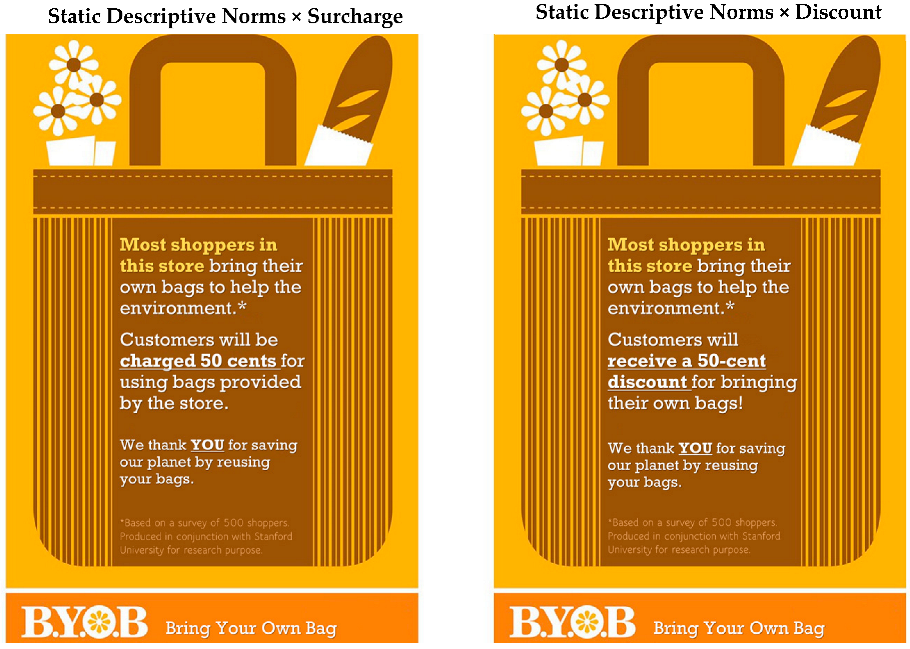

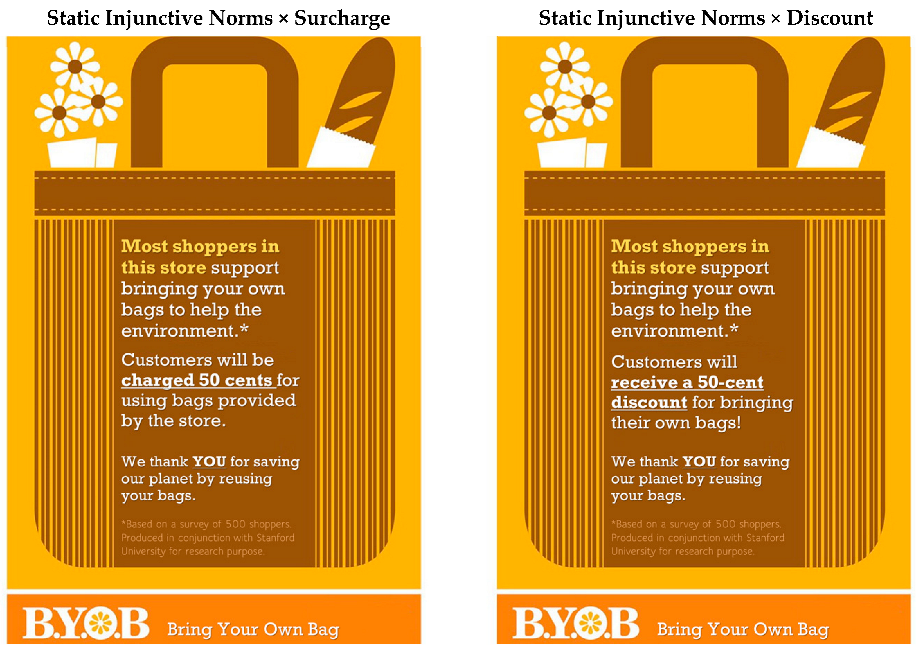

This study employed a between-subjects experimental design with 11 unique message conditions. These included six standalone messages featuring either a static norm (descriptive or injunctive), a dynamic norm (descriptive or injunctive), or a financial incentive (surcharge or discount); four messages that combined a static norm with a financial incentive; and one control condition featuring a general pro-environmental appeal. An institutional review board approved all research procedures.

Upon accessing the study through Qualtrics, participants first completed an informed consent form and answered screening questions to confirm eligibility. Eligible participants then provided basic demographic information (e.g., age, gender, race/ethnicity, and location of residence) and grocery shopping behaviors (e.g., preferred stores, shopping frequency, and shopping modalities). Participants also reported their typical use of different types of grocery bags (plastic, paper, box, reusable, or none), awareness of surcharges or discounts for store-provided bags, and environmental attitudes, including their concern about plastic pollution and attitudes toward using reusable bags.

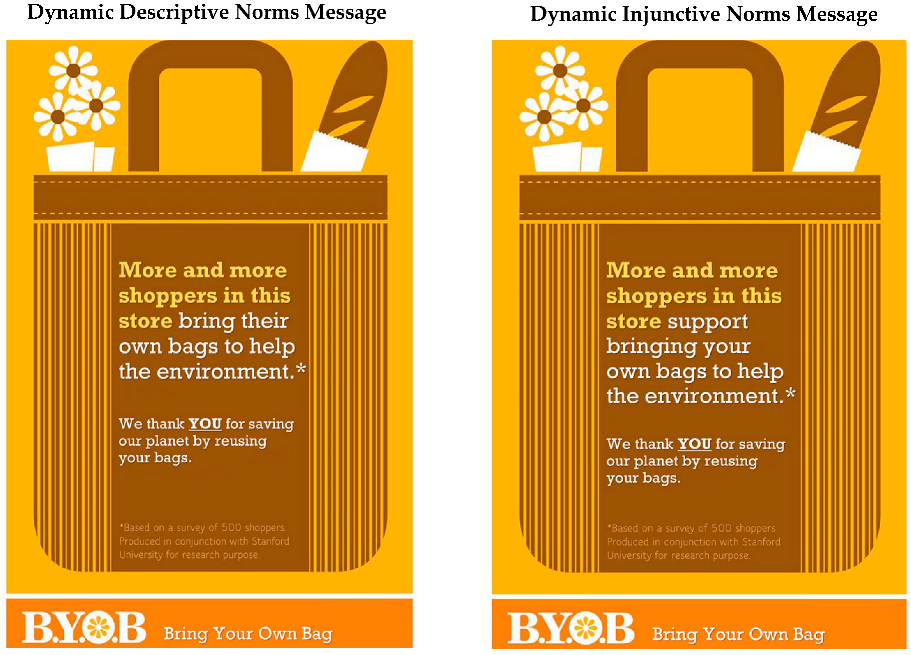

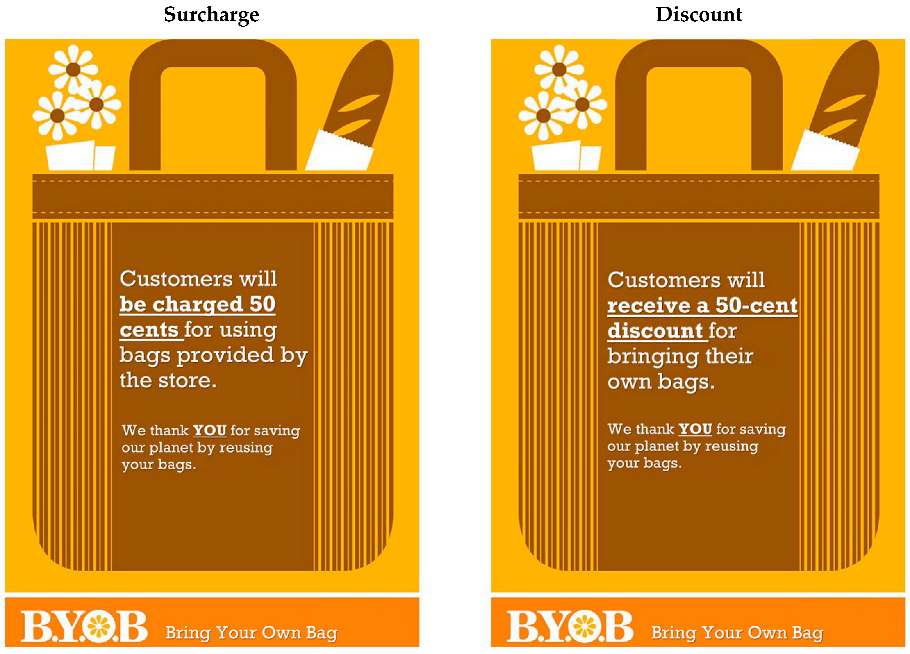

After completing these baseline measures, participants were randomly assigned to one of the eleven experimental conditions and viewed a one-minute video containing the assigned message stimulus (see screenshots in Appendix B; details provided below). Following exposure to the stimulus, participants answered questions regarding their behavioral intentions to bring reusable bags for future grocery shopping. Additional demographic information, such as education level, income, marital status, and political ideology, was collected at the end of the survey, prior to debriefing and study exit.

2.3. Message Stimuli

All message stimuli (see Appendix C) were developed and pilot-tested based on the existing literature and guidelines [43,45], and they were delivered through a one-minute video featuring a first-person view of entering a generic grocery store in the U.S. Since the presence of normative content was treated as an intrinsic message feature, and the primary aim of this study was to examine the effects of message stimuli in a simulated real-world context (i.e., a grocery store flyer), norm perceptions were not measured as a manipulation check in the main study. This aligns with O’Keefe’s [46] argument that when message variations are defined by their intrinsic features, manipulation checks are unnecessary and can be misleading if used merely to validate the manipulation. However, during the message development phase, all stimuli were pilot-tested to ensure they effectively conveyed normative content as intended. To prevent potential confounding variables, any store name or brand details were deliberately obscured. Participants were instructed to engage fully with the video, mentally placing themselves in a grocery store they frequently visited.

The video began with guiding the participants entering the grocery store, offering a glimpse of the store’s interior to immerse them in the shopping experience, as if they were in the store at that moment. Next, the video displayed the message, “As you walk into the store, you see this poster”, followed by the presentation of the specific message stimulus, which remained on screen for 30 s, ensuring participants had ample time to read its contents. Except for the message stimuli that varied across conditions, the poster’s design, including its tagline and the initiative slogan, “We thank YOU for saving our planet by reusing your own bags. B.Y.O.B Bring Your Own Bag”, remained consistent. This slogan also served as the control condition (a general pro-environmental appeal) in this experiment.

In the conditions with financial incentive messages, participants were informed that they would either receive a 50-cent discount for bringing their own bags (discount) or be charged 50 cents for using bags provided by the store (surcharge). The chosen amount was derived from the prevailing range of USD 0.03 to USD 0.5 for plastic bag charges or reusable bag discounts currently implemented across the U.S. [32]. For the purposes of this study, we deliberately opted for the upper end of the financial incentive spectrum to observe the potential maximum efficacy of this strategy.

Meanwhile, in the conditions with static social norm messages, participants were informed that most shoppers bring their own bags to help the environment (static descriptive norm), or most shoppers in this store support bringing their own bags to help the environment (static injunctive norms). In the dynamic social norm conditions, “most shoppers in this store” was replaced by “more and more shoppers in this store” to signify a dynamic trend toward this desirable behavior.

As suggested in the message creation guidelines from the National Social Norms Center [45], a critical aspect of designing effective social norm messages hinges on the availability of current and accurate information from a credible source pertaining to the intended audience’s adherence to the actual norm of the behavior—the prevalence and social approval of bringing one’s own bag for grocery shopping, in this study. Hence, for research purposes, we specified the source of the normative information as “Derived from a survey conducted among 500 shoppers in collaboration with Stanford University”. The selection of Stanford University as the information source was based on its esteemed reputation as one of the most trustworthy research institutions in the U.S. [47].

Recognizing the deceptions involved in the message stimuli, upon participants’ completion of the study, we provided them with a full written explanation of the study purpose, hypotheses/research questions being examined, procedures involving deception, and the rationale for using deceptive information. Participants were also offered an opportunity to withdraw their consent or responses from the study. The researchers’ contact information was provided for any additional inquiries or concerns.

2.4. Measures

Unless otherwise specified, all items were measured using 5-point Likert scales ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree), with higher scores reflecting a greater degree of the variable. Descriptive statistics, zero-order correlations, and scale reliabilities for all measures are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics, zero-order correlations, and reliabilities of measured variables.

The primary dependent variable was participants’ intention to bring their own reusable bags for grocery shopping. This was measured using a five-item scale adapted from Lapinski et al. [48]. A sample item reads, “I have it in my mind to start bringing my own bags for grocery shopping from now on”.

In addition to the main dependent variable, we also measured several variables as potential covariates based on the prior literature on grocery shopping behaviors and environmental decision-making.

Participants’ grocery shopping behaviors were assessed by asking about their primary responsibility for grocery shopping, preferred shopping modality (e.g., in-store vs. online), average number of store visits per week, and top three preferred stores. Participants also indicated whether their store choices were influenced by factors such as the availability of free bags or environmental branding. Awareness of available bag types (plastic, paper, box, or none) and knowledge of any associated surcharges or discounts were also measured.

Existing bag usage behaviors were assessed by asking participants to report their use of different bag types, including plastic bags, paper bags or boxes, reusable bags, and no bags, when shopping at their three most-visited grocery stores.

Environmental concern was measured with a four-item scale adapted from Schultz [49], assessing participants’ concerns about the environmental consequences of human actions for nature, society, themselves, and future generations.

Attitudes toward bringing reusable bags were assessed using a six-item scale adapted from Lapinski et al. [48], with one reverse-coded item removed due to low factor loading. A sample item included, “I think it is a good idea to bring my own reusable bags when shopping for groceries”.

Finally, participants’ demographic characteristics were collected, including age, gender, race/ethnicity, location of residence, household composition, educational attainment, household income, political affiliation and ideology, and religious beliefs.

3. Results

3.1. Random Assignment and Identification of Covariates

SPSS (v.29) and R programming language were used for statistical analyses in this study. To examine the success of the random assignment, a series of Chi-square analyses and one-way ANOVAs were conducted to ensure that participants did not differ substantially in their demographic background (e.g., gender, age, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, income, and household composition). The findings reveal no significant differences in any demographic attributes among the participants. Additionally, participants did not differ in their environmental concerns, attitudes toward bringing reusable bags, and existing bag usage behaviors across experimental conditions. Hence, random assignment was deemed successful.

To identify potential covariates substantially associated with the outcome variable in this study, behavioral intentions of bringing the reusable bags, a multiple regression analysis was conducted with behavioral intentions as the dependent variable; all demographic variables, grocery shopping and bag usage behaviors, attitudes toward bringing reusable bags, and environmental concerns were entered as predictors. Results (see Appendix D) show that age, prior reusable bag usage, environmental concerns, and attitudes emerged as significant predictors while controlling for other potential factors. Hence, these four variables were entered as covariates in the main analysis described below.

3.2. Test the Hypotheses and Answer Research Questions (RQs)

Prior to the main data analysis, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to validate the indicators measuring the latent constructs of behavioral intentions, attitudes, and environmental concerns. The three-factor CFA model yielded a satisfactory model fit, χ2 (87) = 574.65, χ2/df = 6.61, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.95, Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) = 0.94, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.07, 90% CI [0.07, 0.08], and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = 0.04.

To test the hypotheses and answer RQs, a one-way Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) was conducted with the message stimuli as the independent variable, behavioral intentions of bringing the reusable bags for grocery shopping as the dependent variable, and age, prior reusable bag usage, environmental concerns, and attitudes as the covariates. The assumptions for ANCOVA were first checked. The Q-Q Plot (residual plots) and Levene’s test for equality of variances (p = 0.72) showed the normality and homoscedasticity of the distribution. There was also no evidence of multicollinearity among the covariates. Hence, we proceed with the main analysis. The means and standard deviations for behavioral intentions across the stimuli are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Behavioral intentions of bringing reusable bags across message stimuli conditions.

The results indicate a significant main effect for the message stimuli on behavioral intentions, controlling for all the covariates, F(10, 739) = 4.42, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.03. Given that our hypotheses and research questions were theoretically grounded and designed to examine specific comparisons between message conditions, we employed a series of planned contrasts to directly test these a priori expectations (see Table 4 for detailed results). This analytic approach is particularly appropriate when comparisons are specified in advance based on prior theory and empirical evidence, as it allows for greater statistical power and more precise testing of theoretically meaningful effects. Moreover, unlike post hoc analyses, planned contrasts help minimize the inflation of Type I error by focusing only on the comparisons of substantive interest, rather than exploring all possible pairwise differences without theoretical justification.

Table 4.

Planned contrasts of message stimuli on behavioral intentions.

To answer RQ1, static descriptive norm (DN) and static injunctive norm (IN) messages were contrasted. The result indicates that participants exposed to the static IN message expressed significantly stronger intentions of bringing reusable bags compared to those exposed to the static DN message, t(739) = 2.15, p = 0.03, r = 0.08. For RQ2, dynamic DN and dynamic IN messages were contrasted. No significant difference was observed between exposure to the two dynamic norm conditions.

To test H1 and address RQ3, static DN was contrasted to dynamic DN, while static IN was contrasted to dynamic IN. Results show that exposure to the dynamic DN message predicted significantly higher intentions compared to exposure to the static DN message, t(739) = 1.96, p = 0.05, r = 0.07, with no significant difference yielded between the two IN messages. Hence, H1 was consistent with the data.

To test H2, the surcharge message was contrasted with the discount message condition. The results reveal no significant difference in behavioral intentions between these two financial incentive conditions. Hence, H2 was not supported by the data. To answer RQ4, both static and dynamic norm messages were contrasted with the financial incentive messages. The results show that exposure to both static norm messages, t(739) = 4.05, p < 0.001, r = 0.15, and dynamic norm messages, t(739) = 5.00, p < 0.001, r = 0.18, led to greater behavioral intentions compared to financial incentive messages. Specifically, exposure to either static norm message resulted in stronger behavioral intentions compared to exposure to the surcharge, t(739) = 3.57, p < 0.001, r = 0.13, and discount messages, t(739) = 3.10, p = 0.002, r = 0.11. Similarly, exposure to either dynamic norm message led to stronger behavioral intentions compared to exposure to the surcharge, t(739) = 4.33, p < 0.001, r = 0.16, and discount messages, t(739) = 3.83, p < 0.001, r = 0.14.

To answer RQ5, all integrated norm × financial incentive messages were contrasted with the rest of the message stimuli. The results show that the integrated messages led to stronger behavioral intentions compared to all other stimuli, including the control, norms messages, and financial incentives, t(739) = 2.28, p = 0.02, r = 0.08. Specifically, exposure to the integrated message stimuli between IN and either financial incentive led to stronger behavioral intentions compared to all other standalone message stimuli and DN × incentives, t(739) = 2.21, p = 0.03, r = 0.08, while exposure to the DN × incentives messages did not yield a significant difference compared to exposure to all other stimuli.

Lastly, to test H3, Dunnett post hoc analysis was conducted, comparing each of the experimental message stimuli to the control message, the generic pro-environmental appeal. The results show no significant difference between all message stimuli vs. the control message (i.e., they all predicted the same level of behavioral intentions as the control message did), except for the surcharge message (t = −2.84, p = 0.04), which led to significantly lower intentions of bringing the reusable bag compared to the control message. As such, the data were inconsistent with H3.

4. Discussion

By experimentally testing the effects of standalone and integrated message appeals with a nationally representative sample, this research makes important theoretical and practical contributions to knowledge on leveraging social norms and financial incentives to encourage pro-environmental behaviors. Findings shed light on the persuasive effects of tailored messaging strategies for shifting reusable bag adoption. Results demonstrate nuanced outcomes dependent on both content and combinations of normative and economic appeals. Critically, integrating social approval norms with financial incentives shows particular promise for enhancing sustainable consumption intentions, aligning with conceptual perspectives on the motivational complementarity [50]. However, contrasts between dynamic and static norms reveal that continued theoretical and empirical work is needed to fully decipher when and how highlighting changing trends motivates behaviors. Taken together, this investigation presents implications for optimal evidence-based communication strategies while raising additional questions ripe for further exploration.

For standalone social norm appeals, results show that the static injunctive norm message elicited greater intentions to use reusable bags than static descriptive norms, aligning with previous evidence on the motivational power of highlighting social approval. Specifically, this finding echoes De Groot et al. [16], which showed that simple injunctive norm messages emphasizing approval of sustainability behaviors increased reusable bag usage. The authors suggest that injunctive norms leverage individuals’ innate desires to garner positive appraisal through socially appropriate actions.

Moreover, by highlighting perceived expectations of moral conduct, injunctive norms can motivate even without extensive rationalization when behaviors are framed as reputationally and socially advantageous [51]. As choices like reusable bags often provide mixed individual costs and collective benefits, emphasizing social rewards through injunctive norms can tip decisions toward more sustainable outcomes. Our results reinforce this prior work by lending further support to the notion that even basic static appeals tapping into social approval motivations can positively shift environmental intentions and behaviors. This highlights the importance of understanding distinct pathways, like injunctive norms, as levers for change.

Another key finding was the dynamic descriptive norm’s superiority over the static prevalence appeal, consistent with our prediction. Although both messages conveyed favorable reusable bag norms, the static appeal may conflict with prevailing perceptions of high disposable bag usage. Such misalignment may have reduced its persuasive impact compared to the dynamic descriptive norm, which emphasized a growing trend of adoption. These findings contribute to the growing body of literature on dynamic descriptive norms messaging [11,27], particularly amid adverse prevailing norms. Our results further support the benefits of highlighting rising behavioral adoption and communicating positive momentum in the message rather than relying on static prevalence statistics, especially when prevailing norms conflict with recommended behaviors.

In contrast, the static and dynamic injunctive norms were found to be equivalently persuasive in this context. This finding is theoretically important. It may reflect the nature of injunctive norms as relatively stable moral beliefs, making temporal changes in social approval less immediately visible or salient compared to observable behavioral prevalence. As Lee and Liu [28] argue, dynamic shifts in injunctive norms likely require longer exposure and more direct evidence to be persuasive, given their abstract, future-oriented nature. Descriptive norms, on the other hand, may be more susceptible to dynamic framing, as behavioral prevalence is easier to quantify and track over time than moral approval. Incremental behavioral shifts may be more salient and persuasive when based on observable trends than when tied to relatively stable internalized norms of right and wrong [51]. Thus, dynamic framing may be more potent for descriptive than injunctive norms, especially in contexts where behaviors are deeply habitual or morally framed. Meanwhile, the hypothetical scenario used in this study may have limited participants’ engagement with the idea of normative change, whereas dynamic effects might be stronger in real-world contexts where people can witness change over time. These differing patterns suggest a need for further research to clarify under what conditions and for which types of norms dynamic framing is most effective.

Additionally, results reveal that pairing injunctive norm messaging with either financial incentive enhanced intentions to use reusable bags versus any standalone message, including the solitary injunctive norms appeal. This aligns with conceptual perspectives that combining messaging can activate distinct motivational processes with compounding effects [40,52]. Injunctive norms leverage intrinsic desires for social approval and appraisal, while incentives impose extrinsic costs/benefits [30]. Jointly highlighting social and material motivations may have simultaneously tapped these normative and economic drivers. Research on recycling and conservation behaviors also finds that appeals integrating norms and incentives outperform standalone approaches [53]. However, the lack of synergy for descriptive norms and incentives implies that interactive effects depend on message content. Incentives may implicitly reference injunctive expectations more directly than behavioral prevalence. The social signaling interpreted from economic motivators could vary across norm types [51]. More research is needed to clarify when and why integrated norm and incentive messages exhibit synergistic effects.

Lastly, our prediction of the superiority of social norms and financial incentive messages over the generic sustainability message was not evident in the data. The tailored appeals did not clearly outperform the basic pro-environmental prompt. This contrasts with some previous findings that norms elevated reusable bag usage over generic messaging [16], while aligning with recent findings suggesting that, particularly for well-publicized issues like reusable bag use, generic appeals may suffice to activate existing pro-environmental norms [28]. Several factors may explain this lack of superiority. The hypothetical scenario methodology may have limited motivational salience compared to real-world decision contexts where the behavior would be enacted. Additionally, the specific norm and incentive messages used may not have been sufficiently distinct or powerful to produce meaningful cognitive or emotional shifts beyond what was generated by the generic appeal. Message saturation may also be a factor, as reusable bags are a fairly prominent topic. Overcoming indifference requires tapping impactful motivations and avoiding message fatigue [54]. Overall, the lack of clear effects over a generic appeal demonstrates a need to continue strengthening message design and targeting influential mechanisms. Impactful communication requires resonating content and minimizing fatigue effects.

4.1. Implications

This research makes important theoretical contributions by revealing the nuanced effectiveness of social norms and financial incentive messaging for promoting a sustainable shift from plastic to reusable bags. Findings lend empirical support to the conceptual rationale that message appeals integrating intrinsic (e.g., social norms) and extrinsic (e.g., financial incentives) motivations can have synergistic effects by tapping complementary mechanisms [52]. However, the divergent outcomes between static and dynamic norm messaging point to the need for continued refinement of normative influence theories, particularly in specifying the conditions under which dynamic appeals foster motivation and the psychological pathways through which perceptions of norm change influence behavior.

Theoretically, this study reinforces the importance of distinguishing between static and dynamic framings of both descriptive and injunctive norms. While dynamic descriptive norms can stimulate perceptions of growing behavioral trends and motivate action, dynamic injunctive norms may require deeper integration into individuals’ future moral expectations to exert comparable influence [28]. Future studies should explore how perceptions of emerging social approval develop and how they can be leveraged more effectively.

Empirically, the study informs evidence-based messaging strategies for environmental behavior change. Although the observed effect sizes of message appeals were modest (r = 0.07–0.18), they are consistent with prior meta-analyses of behavior change interventions in environmental contexts [55,56]. Given the habitual and entrenched nature of consumer behaviors like bag usage, even small shifts can aggregate to a substantial societal impact when scaled across populations. Notably, message-based interventions typically produce gradual, incremental changes rather than large, immediate shifts, a pattern well documented in prior research on environmental and habitual behavior change [57].

In addition, while norm- and incentive-based appeals are often presumed to outperform generic sustainability messages, our results caution against such assumptions. Campaign designers should recognize that generic sustainability messages may remain effective in saturated issue domains. Tailored appeals may need to be notably stronger, more emotionally resonant, or highlight personal involvement and group identity processes to outperform general pro-environmental prompts. To maximize the effectiveness of tailored messaging efforts, future research and practice should prioritize rigorous pre-testing of message content and framing to ensure clarity, emotional resonance, and relevance. Additionally, enhancing message salience through vividness, immediacy, and personal relevance will be crucial for maximizing attention, cognitive processing, and behavioral impact in experimental and applied settings.

Moreover, integrating social approval norms with financial incentives shows particular promise for motivating collective participation, consistent with prior research [58]. Specifically, our findings suggest that focusing on social signaling, especially through social approval cues such as verbal appreciation from cashiers and smiley faces on flyers, posters, or self-checkout screens for using reusable bags, along with integrated norm and incentive appeals, holds the potential to reduce plastic bag dependence.

From a practical standpoint, communication professionals and campaign designers should pay close attention to the alignment between perceived and actual norms, especially when the goal is to shift behaviors that are not yet widely adopted. In such cases, emphasizing positive momentum and dynamic change, rather than static statistics, may be more effective in motivating individuals who might otherwise defer action due to perceived norm incongruence [59]. Messaging that portrays sustainable behaviors as increasingly common and socially valued can help bridge the intention–action gap, especially in transitional phases of public norm development.

4.2. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations that warrant opportunities for future research. First, the hypothetical scenario online experiment assessed intentions rather than actual behaviors, which may have reduced motivational salience compared to field studies. The intention–behavior gap is well documented in environmental psychology, where expressed intentions may fail to translate into actions due to habitual patterns, convenience factors, and contextual barriers [6]. Future research should extend these findings by collecting actual behavioral data through field experiments, such as displaying the messages in grocery stores and observing shoppers’ behaviors, to determine whether the effects observed in intentions manifest in measurable behavior change.

Second, while statistically significant, many of our observed message effects were modest in size. Although this pattern is consistent with prior meta-analytic findings, as discussed earlier, it suggests that stronger, more emotionally resonant, or identity-based interventions may be necessary to produce larger behavioral shifts. Future research should explore strategies to amplify intervention strength and salience to enhance practical significance.

Third, future research should explore additional psychological mediators and moderators to further understand the underlying mechanisms of normative and incentive-based message effects. Measuring constructs such as perceived descriptive and injunctive norms, efficacy beliefs, outcome expectations, emotional reactions, and perceived message credibility could reveal how different appeals shape cognitive and affective pathways toward behavior change. The unexpected finding that generic sustainability messages performed similarly to more tailored appeals highlights the importance of understanding how individuals cognitively and emotionally process normative and incentive cues. It is possible that generic messages triggered existing pro-environmental values or heuristics without requiring detailed elaboration, while tailored messages may not have been sufficiently novel or personally relevant to evoke stronger processing. Future studies should examine how factors such as message novelty, emotional arousal, identity relevance, and cognitive elaboration mediate the impact of different message types, particularly to understand when and why tailored appeals produce stronger effects than generic prompts.

Lastly, while our study controlled for some individual differences, it did not explicitly examine how cultural background, regional context, or group identity might moderate message effectiveness. Prior research suggests that normative messages can have differential effects depending on individual characteristics and cultural orientations [60]. Future research should investigate how variables such as national identity, cultural tightness–looseness, and political ideology moderate normative and incentive-based appeals, particularly for advancing more targeted and culturally responsive environmental communication strategies. In addition, testing systematic variations in message content and framing tailored to specific cultural and demographic contexts could uncover ways to enhance resonance while minimizing message fatigue or reactance. Different groups may respond differently to norm types, incentive levels, or framing styles [61,62,63], and targeting these characteristics more precisely could amplify persuasive effects.

Overall, these directions highlight important opportunities to refine and strengthen the effectiveness of normative and incentive-based appeals across diverse behavioral and cultural contexts.

5. Conclusions

This research examines how standalone and integrated social norms and financial incentive messaging can promote reusable bag usage among grocery shoppers. The findings reveal the effectiveness of communication-based strategies through conveying social approvals and expectations (i.e., static injunctive norms), as well as the positive momentum and growing engagement in the desired behavior (i.e., dynamic descriptive norms). It also shows that carefully integrating social and economic motivators holds promise for encouraging sustainable behavioral transitions, as tailored appeals highlighting both social expectations and surcharges outperformed standalone messages. These results provide an evidence-based model for reducing plastic bag usage through the selective use of social nudges and economic motivators, offering a roadmap for plastic reduction initiatives leveraging the power of social norms and financial incentives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, all three authors; methodology, all three authors; software, R.W.L.; validation, R.W.L. and J.Z.; formal analysis, R.W.L. and J.Z.; investigation, R.W.L.; resources, R.W.L. and T.A.F.; data curation, R.W.L.; writing—original draft preparation, all three authors; writing—review and editing, all three authors; visualization, R.W.L.; supervision, R.W.L.; funding acquisition, R.W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Social and Behavioral Sciences Research Institute (SBSRI) Faculty Small Grants at the University of Arizona.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Human Subjects Protection Program (HSPP) and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Arizona (protocol code FWA #00004218 on 8 August 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy restrictions associated with the funded research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Map of the Data Collection Locations

Appendix B. Screenshots of the Video Used in the Experiment

The automatic glass doors then opened, showing participants the interior of the store.

The video will zoom in to display the poster in a full-size format as below, and this enlarged version will remain on the participants’ screen for a duration of 30 s.

Appendix C. Message Stimuli

Appendix D. Results of Regression Analysis for Identifying Covariates

| 95.0% Confidence Interval for B | |||||||

| Unstandardized B | Standard Error | Standardized β | t | p | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |

| (Intercept) | 0.06 | 0.47 | 0.13 | 0.90 | −0.86 | 0.99 | |

| Age | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 2.18 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Gender | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.67 | 0.51 | −0.09 | 0.17 |

| Education | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.03 | −1.07 | 0.29 | −0.07 | 0.02 |

| White (1) | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.18 | 0.86 | −0.25 | 0.29 |

| Black (1) | −0.11 | 0.17 | −0.03 | −0.61 | 0.55 | −0.45 | 0.24 |

| Household Size | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | −0.09 | 0.93 | −0.05 | 0.05 |

| Income | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.32 | 0.75 | −0.03 | 0.05 |

| Single (1) | 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.96 | −0.44 | 0.46 |

| Married (1) | 0.04 | 0.22 | 0.02 | 0.17 | 0.86 | −0.40 | 0.48 |

| Separated/Divorced/Widowed (1) | −0.08 | 0.23 | −0.03 | −0.33 | 0.74 | −0.53 | 0.37 |

| Religious (1) | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 1.87 | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.25 |

| Republican | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.11 | 1.03 | 0.30 | −0.23 | 0.75 |

| Democrat | 0.30 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 1.18 | 0.24 | −0.20 | 0.80 |

| Independent | 0.29 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 1.16 | 0.25 | −0.20 | 0.78 |

| Liberal-Conservative | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.02 | −0.46 | 0.65 | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| Prior Plastic Bags Usage | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.03 | −0.61 | 0.54 | −0.00 | 0.00 |

| Prior Reusable Bags Usage | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 3.17 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Weekly Shop Trip | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.03 | −0.91 | 0.36 | −0.05 | 0.02 |

| Shop Responsibility | −0.08 | 0.06 | −0.04 | −1.35 | 0.18 | −0.20 | 0.04 |

| Shop Mode | −0.01 | 0.08 | 0.00 | −0.14 | 0.89 | −0.17 | 0.14 |

| Environmental Concerns | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 3.40 | <0.001 | 0.06 | 0.22 |

| Attitudes | 0.65 | 0.05 | 0.53 | 13.70 | <0.001 | 0.56 | 0.74 |

| adjusted R2 = 0.45, F(22, 696) = 27.24, p < 0. 001 | |||||||

References

- United Nations Environment Programme. Single-Use Plastics: A Roadmap for Sustainability; UNEP—UN Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme. NEGLECTED: Environmental Justice Impacts of Marine Litter and Plastic Pollution; UNEP—UN Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Khoaele, K.K.; Gbadeyan, O.J.; Chunilall, V.; Sithole, B. The devastation of waste plastic on the environmental and remediation processes: A critical review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleman, R.; Amjad, A.; Ismail, A.; Javed, S.; Ghafoor, U.; Fahad, S. Impact of plastic bags usage in food commodities: An irreversible loss to environment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 49483–49489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, M.; Lapinski, M.K. The effect of dynamic norms messages and group identity on pro-environmental behaviors. Commun. Res. 2024, 51, 439–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidbreder, L.M.; Bablok, I.; Drews, S.; Menzel, C. Tackling the plastic problem: A review on perceptions, behaviors, and interventions. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 668, 1077–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakovcevic, A.; Steg, L.; Mazzeo, N.; Caballero, R.; Franco, P.; Putrino, N.; Favara, J. Charges for plastic bags: Motivational and behavioral effects. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Koestner, R.; Ryan, R.M. A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 627–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Trost, M.R. Social influence: Social norms, conformity and compliance. In The Handbook of Social Psychology, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1998; Volume 1–2, pp. 151–192. [Google Scholar]

- Lapinski, M.K.; Kerr, J.M.; Zhao, J.; Shupp, R.S. Social norms, behavioral payment programs, and cooperative behaviors: Toward a theory of financial incentives in normative systems. Hum. Commun. Res. 2017, 43, 148–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparkman, G.; Walton, G.M. Dynamic norms promote sustainable behavior, even if it is counternormative. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 28, 1663–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Reno, R.R.; Kallgren, C.A. A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 58, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, J.I.M.; Bondy, K.; Schuitema, G. Listen to others or yourself? The role of personal norms on the effectiveness of social norm interventions to change pro-environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 78, 101688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparkman, G.; Howe, L.; Walton, G. How social norms are often a barrier to addressing climate change but can be part of the solution. Behav. Public Policy 2021, 5, 528–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amel, E.; Manning, C.; Scott, B.; Koger, S. Beyond the roots of human inaction: Fostering collective effort toward ecosystem conservation. Science 2017, 356, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, J.I.M.; Abrahamse, W.; Jones, K. Persuasive normative messages: The influence of injunctive and personal norms on using free plastic bags. Sustainability 2013, 5, 1829–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-Y. The moderating role of descriptive norms on construal-level fit: An examination in the context of “less plastic” campaigns. Environ. Commun. 2021, 15, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorigoni, A.; Bonini, N. Water bottles or tap water? A descriptive-social-norm based intervention to increase a pro-environmental behavior in a restaurant. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 86, 101971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, K.; Curtis, J.; Lindsay, J. Social norms and plastic avoidance: Testing the theory of normative social behaviour on an environmental behaviour. J. Consum. Behav. 2020, 19, 594–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, S.; Herberz, M.; Hahnel, U.J.J.; Brosch, T. The effectiveness of nudging: A meta-analysis of choice architecture interventions across behavioral domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2107346118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastini, K.; Kerschreiter, R.; Lachmann, M.; Ziegler, M.; Sawert, T. Encouraging individual contributions to net-zero organizations: Effects of behavioral policy interventions and social norms. J. Bus. Ethics 2024, 192, 543–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savari, M.; Damaneh, H.E.; Damaneh, H.E.; Cotton, M. Integrating the norm activation model and theory of planned behaviour to investigate farmer pro-environmental behavioural intention. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, J.M. Social norm interventions as a tool for pro-climate change. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2021, 42, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedict, S.; Hussein, H. An analysis of water awareness campaign messaging in the case of Jordan: Water conservation for state security. Water 2019, 11, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimal, R.N.; Lapinski, M.K. A re-explication of social norms, ten years later. Commun. Theory 2015, 25, 393–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparkman, G.; Walton, G.M. Witnessing change: Dynamic norms help resolve diverse barriers to personal change. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 82, 238–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfora, V.; Zeiske, N.; van der Werff, E.; Steg, L.; Catellani, P. Adding dynamic norm to environmental information in messages promoting the reduction of meat consumption. Environ. Commun. 2022, 16, 900–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Liu, J. Leveraging dynamic norm messages to promote counter-normative health behaviors: The moderating role of current and future injunctive norms, attitude and self-efficacy. Health Commun. 2023, 38, 1071–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, P.A.; Fong, G.T.; Hitchman, S.C.; Quah, A.C.K.; Agar, T.; Meng, G.; Ayaz, H.; Dore, B.P.; Sakib, M.N.; Hudson, A.; et al. Brain and behavior in health communication: The Canadian COVID-19 Experiences Project. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2022, 22, 100467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, A.; Duke, K.E.; Amir, O. How incentive framing can harness the power of social norms. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2019, 151, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, T.P. Reducing single-use plastic shopping bags in the USA. Waste Manag. 2017, 70, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Conference of State Legislatures. State Plastic and Paper Bag Legislation; National Conference of State Legislatures: Denver, CO, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, T.D.; Holmberg, K.; Stripple, J. Need a bag? A review of public policies on plastic carrier bags—Where, how and to what effect? Waste Manag. 2019, 87, 428–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poortinga, W.; Whitmarsh, L.; Suffolk, C. The introduction of a single-use carrier bag charge in Wales: Attitude change and behavioural spillover effects. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 36, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G.O.; Poortinga, W.; Sautkina, E. The Welsh single-use carrier bag charge and behavioural spillover. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 47, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homonoff, T.A. Can small incentives have large effects? The impact of taxes versus bonuses on disposable bag use. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 2018, 10, 177–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiola, B.A.; Visser, M.; Daniels, R.C. Addressing plastic bags consumption crises through store monetary and non-monetary interventions in South Africa. Front. Sustain. 2023, 3, 968886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y. How do tougher plastics ban policies modify people’s usage of plastic bags? A case study in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellerano, J.A.; Price, M.K.; Puller, S.L.; Sánchez, G.E. Do extrinsic incentives undermine social norms? Evidence from a field experiment in energy conservation. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2017, 67, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, J.M.; Lapinski, M.K.; Liu, R.W.; Zhao, J. Long-term effects of payments for environmental services: Combining insights from communication and economics. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Census Bureau. U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: United States; United States Census Bureau: Suitland-Silver Hill, MD, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, H. Sample size determination and power analysis using the G*Power software. J. Educ. Eval. Health Prof. 2021, 18, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, N.; Shulman, H.C.; McClaran, N. Changing norms: A meta-analytic integration of research on social norms appeals. Hum. Commun. Res. 2020, 46, 161–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrow, K.; Grolleau, G.; Ibanez, L. Social norms and pro-environmental behavior: A review of the evidence. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 140, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Social Norms Center. Social Norms Approach; National Social Norms Center: East Lansing, MI, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe, D.J. Message properties, mediating states, and manipulation checks: Claims, evidence, and data analysis in experimental persuasive message effects research. Commun. Theory 2003, 13, 251–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudaha, R. Americans’ Most Trusted Universities, and the Need to Bridge Gaps in Public Trust; Morning Consult: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lapinski, M.K.; Rimal, R.N.; DeVries, R.; Lee, E.L. The role of group orientation and descriptive norms on water conservation attitudes and behaviors. Health Commun. 2007, 22, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, P.W. The structure of environmental concern: Concern for self, other people, and the biosphere. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Bolderdijk, J.W.; Keizer, K.; Perlaviciute, G. An integrated framework for encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: The role of values, situational factors and goals. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, R.P.; Mortensen, C.R.; Cialdini, R.B. Bodies obliged and unbound: Differentiated response tendencies for injunctive and descriptive social norms. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 100, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guagnano, G.A.; Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T. Influences on attitude-behavior relationships: A natural experiment with curbside recycling. Environ. Behav. 1995, 27, 699–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoeli, E.; Hoffman, M.; Rand, D.G.; Nowak, M.A. Powering up with indirect reciprocity in a large-scale field experiment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 10424–10429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronrod, A.; Grinstein, A.; Wathieu, L. Go green! Should environmental messages be so assertive. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamse, W.; Steg, L. Social influence approaches to encourage resource conservation: A meta-analysis. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 1773–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisa, C.F.; Bélanger, J.J.; Schumpe, B.M.; Faller, D.G. Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials testing behavioural interventions to promote household action on climate change. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokhorst, A.M.; Werner, C.; Staats, H.; van Dijk, E.; Gale, J.L. Commitment and behavior change: A meta-analysis and critical review of commitment-making strategies in environmental research. Environ. Behav. 2013, 45, 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, H.; John, P.C.; Cotterill, S. The use of feedback to enhance environmental outcomes: A randomized controlled trial of a food waste scheme. Local Environ. 2011, 16, 637–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schorn, A. Why should I when no one else does? A review of social norm appeals to promote sustainable minority behavior. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1415529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melnyk, V.; Carrillat, F.A.; Melnyk, V. The influence of social norms on consumer behavior: A meta-analysis. J. Mark. 2022, 86, 98–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnyk, V.; Herpen Evan Fischer, A.R.H.; van Trijp, H.C.M. To think or not to think: The effect of cognitive deliberation on the influence of injunctive versus descriptive social norms. Psychol. Mark. 2011, 28, 709–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, C. Green nudges: Do they work? Are they ethical? Ecol. Econ. 2017, 132, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.R.; Louis, W.R.; Terry, D.J.; Greenaway, K.H.; Clarke, M.R.; Cheng, X. Congruent or conflicted? The impact of injunctive and descriptive norms on environmental intentions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]