1. Introduction

Urbanisation, as a widespread global phenomenon, has precipitated numerous challenges related to environmental degradation and the declining quality of life in urban environments. Its intensification, closely linked with processes of industrialisation and globalisation, has significantly amplified ecological stressors, particularly in developing countries, where pollution increasingly jeopardises public health and long-term sustainability [

1]. The accelerated expansion of urban areas, especially over the past few decades, has contributed to spatial disparities, the depletion of natural resources, and growing pressure on existing infrastructure [

2]. In response, there is a growing and urgent demand for more extensive, high-quality UGS, due to their proven ability to reduce negative urban externalities such as air pollution, high temperatures, and noise. Pollution from industry, transport, and municipal services directly affects physical and mental health, reducing the urban quality of life and posing long-term risks to public well-being. Recent studies underline the potential of green infrastructure to mitigate urban heat island effects, reduce air pollution, and improve health-related outcomes, reaffirming their relevance for sustainable urban planning [

3].

UGS are defined as publicly accessible, purposefully planned vegetated areas within urban environments, including parks, public gardens, tree-lined streets, lawns, and recreational zones. They also offer recreational and experiential value, considered essential for psychological restoration and daily urban quality of life [

4]. These spaces perform multiple functions: ecological, social, aesthetic, and health-related. They are fundamental to improving the quality of life in urban settings. UGS contribute to the regulation of microclimatic conditions, the absorption of pollutants, the preservation of biodiversity, and the mitigation of the urban heat island effect [

5,

6]. As integral components of sustainable urban planning frameworks, they are increasingly regarded as strategic assets for enhancing climate resilience and mitigating the adverse impacts of climate change in densely built environments [

7]. Their contribution to mental well-being is also well documented as they help reduce psychological stress, promote physical activity, and foster social cohesion within urban populations [

8,

9].

In light of these recognised benefits, recent scholarly discourse increasingly positions UGS as critical components of sustainable urban development and public health strategies. However, persistent disparities in the distribution, quality, and accessibility of UGS remain evident, while their perception and valuation are shaped by a constellation of factors, including users’ sociodemographic profiles, levels of urbanisation, and the orientation of local planning policies [

10,

11]. Users evaluate UGS not only for their ecological functions but also through psychological, cultural, and social aspects, such as place identity, opportunities for gathering, and daily interaction [

12,

13]. At the same time, urban planning agendas are increasingly attuned to the imperative of equitable access and to the risks associated with green gentrification, which may undermine social inclusiveness and exacerbate disparities in the distribution of urban resources [

14]. Consequently, there is growing emphasis on integrative research approaches that capture ecological, social, economic, and cultural dimensions in exploring user perceptions and satisfaction. Empirical studies consistently affirm that the perceived quality, functionality, and role of UGS within local communities exert a measurable influence on user well-being and satisfaction levels [

15,

16]. In addition, gender-specific preferences and age-related differences in green space use, especially among older populations, shape satisfaction outcomes and should inform inclusive design practices [

17]. The shift to green urban policies and sustainable resource governance is now seen as essential, especially in cities facing growing climate, social, and economic pressures [

18], highlighting the importance of context-specific investigations that explore how UGS are perceived, experienced, and valued in distinct urban settings.

This study examines the role of ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) factors, which have gained importance in urban green space (UGS) management. Integrating ESG practices into urban planning improves the sustainability and inclusivity of UGS. ESG factors are essential for assessing how environmental, social, and governance practices influence UGS management, contributing to their preservation and development in line with sustainable urban goals. By focusing on these factors, UGS can preserve ecological integrity, promote social well-being, and enhance governance transparency [

19]. This is further supported by the emerging literature identifying ESG dimensions as risk-mitigating elements in long-term urban investment and governance strategies [

20].

This study builds on existing evidence to examine how residents of Novi Sad perceive, value, and engage with UGS. The city is experiencing rapid development and increasing ecological challenges. The research focuses on identifying the key economic, ecological, psychological, cultural, and social dimensions of UGS that users find most relevant and analysing the main predictors of overall user satisfaction.

As one of the fastest-growing and strategically positioned urban centres in Serbia and the wider region, Novi Sad provides a distinct context for examining the sustainability of urban green spaces (UGS). The city is characterised by rapid spatial development, infrastructural strain, and increasing pressure on natural resources. Despite the formal integration of green areas into urban plans, challenges persist, including unequal distribution, limited accessibility, and insufficient participatory governance. These conditions make Novi Sad a pertinent setting for exploring the multifaceted challenges of green space provision in medium-sized Southeast European cities. Emerging approaches to participatory democracy and digital tool integration in urban planning further support the call for inclusive, data-informed, and adaptive green infrastructure strategies [

21,

22].

While interest in UGS multifunctionality is increasing, there is still a lack of context-specific, integrated studies connecting user perceptions with ESG-oriented planning in Southeast European cities. This study addresses this gap by providing an empirical assessment of user satisfaction, expectations, and evaluations of UGS in Novi Sad while integrating ESG-related dimensions into the analytical framework [

4,

23].

Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) factors in the context of urban green space (UGS) management refer to an integrated assessment framework encompassing ecological dimensions (e.g., biodiversity, air quality, climate resilience), social aspects (e.g., equitable access, social cohesion, community engagement), and governance mechanisms (e.g., transparency, participatory planning, long-term management sustainability), aligned with contemporary ESG practices in natural resource governance [

19]. In this study, ESG principles are operationalised through the evaluation of user perceptions regarding the presence and relevance of these factors in the management of UGS in Novi Sad.

2. User Experience and Functionality in Urban Green Infrastructure

Contemporary research highlights the essential role of urban green infrastructure, commonly embodied by urban green spaces (UGS), in enhancing urban quality of life by addressing a range of ecological, social, psychological, economic, and cultural challenges [

24]. To effectively address external pressures such as climate change and urban pollution, the management of green infrastructure requires strategies that go beyond spatial preservation, incorporating functional and socio–cultural values [

25]. This approach demands a comprehensive understanding of key user preferences, including the importance of space, facilities, and natural elements that foster environmental benefits, stress reduction, and social interaction [

26]. UGS play a significant role in mitigating pollution, regulating temperatures, improving public health, and supporting the long-term sustainability of urban ecosystems. As integral components of urban planning, these spaces help counteract the adverse effects of urbanisation, such as the urban heat island effect, air pollution, and broader environmental degradation [

3]. Despite their importance, however, these spaces face challenges from urban expansion, real estate speculation, and fragmented institutional oversight, which limit their protection and growth, even when formally included in urban plans [

27].

Effective sustainability reporting allows companies to track their environmental and social impacts systematically, thereby contributing to the advancement and enhancement of UGS. Innovations in reporting methodologies enable the identification and implementation of ecological initiatives such as tree planting, park restoration, and the integration of green infrastructure. The adoption of agro-ecological practices in urban environments, including composting, afforestation, and the use of environmentally sustainable technologies, plays a crucial role in reducing the ecological footprint and improving environmental quality [

28]. Research confirms that managing sustainable business practices is vital for achieving broader sustainability goals, with innovative approaches to sustainability reporting becoming increasingly important. Improvements in ESG reporting methodologies are key to fostering transparent, accountable business models that actively contribute to sustainable urban development [

29]. These practices enhance transparency and support the integration of ecological and social considerations into business strategies, positively influencing urban green spaces and overall quality of life in cities [

30]. Within this framework, improved reporting mechanisms help manage UGS more efficiently, mitigate environmental impacts, and promote healthier, more liveable and resilient urban areas. Furthermore, the integration of ESG-related risk factors, particularly those related to carbon and environmental sustainability, provides a more comprehensive understanding of the financial and social impacts associated with business practices. Recent studies suggest that ESG factors, though not always directly priced into returns, play a significant role in asset pricing models and can guide investment strategies aimed at long-term sustainability [

20,

31].

Understanding user perceptions is crucial, as these can vary according to sociodemographic factors such as age, education, income, and residential context, whether urban or peri-urban. These factors significantly influence how individuals experience and value UGS [

11,

32]. Research also identifies gender-based difference, with women often placing greater importance on lighting, safety, playgrounds, and attractive surroundings, which are frequently tied to caregiving responsibilities and regular use of neighbourhood green spaces [

33]. Older individuals tend to prioritise tranquillity, safety, and accessibility, while younger populations emphasise recreational and sports facilities [

10,

34].

The social and communal functions of UGS lie in their capacity to facilitate everyday encounters, support both spontaneous and organized gatherings, strengthen collective identities, and foster a sense of belonging. In urban areas characterized by migration and social fragmentation, these spaces can play a pivotal role in integrating vulnerable groups and building trust among residents [

13,

35]. To fully realize these functions, research identifies key attributes that UGS should possess, such as accessibility, connectivity, diversity of activities, opportunities for social interaction, provision of amenities, safety, and aesthetic value. Together, these qualities enhance social cohesion and overall urban quality of life [

4]. Importantly, user satisfaction is not always correlated with quantitative factors such as surface area or the number of facilities. Instead, it is more influenced by perceived quality, maintenance standards, safety, accessibility, and the subjective experience of benefits [

16,

36]. Public green spaces have been shown to significantly improve life satisfaction among urban residents, and their thoughtful integration into urban planning can contribute meaningfully to individual well-being and collective quality of life [

37]. In this respect, the provision of adequate and inclusive green spaces should be a priority in efforts to create healthier and more equitable urban environments.

In addition to their ecological, social, and cultural roles, user satisfaction and visitation patterns are shaped by various interrelated factors. Among the most influential are physical accessibility, proximity to residential areas, the presence and quality of amenities, perceived safety, maintenance standards, and the variety of activities available in these spaces [

38]. Individuals are more likely to engage with spaces that offer walking paths, sports facilities, resting areas, playgrounds, and environments suited for cultural or educational use. However, it is not only the physical attributes that determine satisfaction; subjective perceptions of safety, comfort, and overall utility often play a more decisive role [

39]. Evidence suggests that green areas that are aesthetically appealing, functionally coherent, and consistently maintained contribute to increased social interaction, reduced psychological stress, and a stronger sense of local belonging. Well-designed and effectively managed public spaces are therefore considered essential for enhancing physical, emotional, and social well-being, further emphasizing their contribution to urban quality of life [

40,

41].

The frequency of use and level of satisfaction with green spaces depend not only on physical accessibility and the range of amenities, but also on the quality of infrastructure, maintenance standards, and the degree of participatory management. Contemporary studies show that environments with well-designed paths, benches, public lighting, sanitary facilities, and spaces for different age groups are perceived as more appealing [

39]. The maintenance of vegetation, cleanliness, and the integration of ecological features such as rainwater harvesting systems or composting facilities further enhance users’ perception of order and functionality. Active citizen involvement in the planning and use of green areas through consultation, educational programs, and community-based initiatives ensures their long-term sustainability and responsiveness to local needs. International research suggests that older adults especially value spaces that are both functionally accessible and aesthetically pleasing, allowing them to engage actively and enjoy the space visually, regardless of cultural or social background [

42]. Additionally, the creation of green infrastructure with an emphasis on climate resilience, such as tree planting, biodiversity preservation, and reducing urban heat island effects, plays a vital role in securing the ecological stability of urban environments over time [

38].

Assessing the relevance of green infrastructure increasingly involves a multidimensional perspective that accounts for its contribution to environmental sustainability and public health. A growing body of evidence indicates that exposure to natural urban environments has beneficial effects on psychological and physical well-being, including stress reduction, stimulation of physical activity, and therapeutic outcomes, particularly among individuals with chronic health conditions [

9,

15]. In addition, ecological functions such as microclimate regulation, pollutant filtration, and biodiversity preservation are widely recognised and valued by the public [

6,

43]. However, overall satisfaction is also closely linked to spatial accessibility, functional design, perceived safety, aesthetic experience, and the consistency of maintenance. People are more likely to engage with green areas that are well connected to urban infrastructure, adapted to diverse demographic profiles, and equipped with inclusive amenities [

38]. The presence of educational, cultural, and nature-based activities further enhances levels of engagement and encourages more frequent use. Safety-related aspects, including adequate lighting, routine upkeep, visible staff, and environmental cleanliness, are essential in shaping favourable perceptions and supporting prolonged use [

39]. Infrastructural elements such as walking paths, seating zones, playgrounds, and vegetated surroundings not only increase practical utility but also foster a sense of comfort and encourage social interaction, contributing to the overall appeal and long-term usability of green areas.

Multidimensional evaluations increasingly recognise the economic value of urban green infrastructure, including its role in enhancing property values, supporting tourism, and stimulating local economies through organised activities and community events [

44]. In parallel, green environments serve as cultural anchors, reflecting collective memory, symbolism, and shared identity [

12,

45]. Growing attention is also being directed towards toward the integration of digital innovation into sustainable urban management. The development of smart public parks illustrates how technology can promote physical activity, social inclusion, and preventive healthcare, especially among older adults. Smart features such as automated lighting, health-monitoring sensors, interactive fitness equipment, and real-time data collection have the potential to support active ageing and improve overall user experience [

46]. These advancements enhance inclusiveness by enabling older individuals to engage with green environments in meaningful ways, without requiring advanced digital literacy. Their successful implementation, however, relies on interdisciplinary cooperation and strong institutional commitment to the creation of adaptable and accessible public spaces. Digital transformation is increasingly acknowledged as a strategic driver of sustainability, not only in agriculture but also in urban planning, where it facilitates more responsive and efficient management of green systems [

47]. By integrating sensor-based monitoring, usage data, and participatory digital platforms, urban policies can better reflect actual community needs [

5]. Moreover, investment in public green areas is now widely recognised as a cost-effective public health strategy as access to well-designed green infrastructure has been shown to enhance population well-being and reduce healthcare expenditures over time [

48].

Contemporary urban waste management challenges, particularly related to solid waste generation and disposal, have intensified the need to embed green infrastructure within broader sustainable development strategies. Efficient municipal waste handling, especially through organic matter valorisation via composting and anaerobic digestion, is increasingly recognised as essential for building ecologically resilient cities [

49]. Evidence from cities like Nakuru and Mombasa in Kenya demonstrates the relevance of integrating green technologies and circular economy principles, including composting and recycling, into local systems. These practices reduce environmental pressure and strengthen the ecological functionality of open spaces, linking waste recovery directly with landscape regeneration and long-term urban sustainability [

50].

The integration of green infrastructure into circular economy strategies, particularly through composting and anaerobic digestion, plays a crucial role in reducing pollution and ensuring effective organic waste utilisation. By alleviating environmental pressures and supporting renewable resource flows, such approaches contribute directly to the sustainability of urban ecosystems. In addition to ecological benefits, circularity enhances economic resilience by creating jobs and encouraging new business models in the recycling and reuse sectors, strengthening local communities. It also supports more efficient resource use and waste minimisation through environmentally sound technologies and closed-loop systems [

51]. These practices form a foundation for enduring ecological and economic transformation in urban contexts. When recycling and reuse are integrated into urban planning, they generate inclusive growth by aligning environmental objectives with social and economic development [

52]. Systematic application of these principles helps address contemporary waste challenges by increasing resource efficiency and promoting sustainable urban systems [

23].

Evidence from agri-environmental policy research in Serbia highlights the value of agro-ecological measures in enhancing biodiversity and improving environmental quality. Such interventions can support the development of healthier urban landscapes while extending the application of ecological standards through nature-based infrastructure. Embedding these concepts within broader societal and economic agendas is critical for advancing responsible resource governance and safeguarding natural capital as a basis for future urban sustainability [

53]. Moreover, the deployment of photovoltaic systems for irrigation infrastructure in landscaped areas facilitates sustainable water management by reducing reliance on fossil fuels and lowering carbon emissions. The use of solar energy for powering pumps not only improves energy efficiency over time but also contributes to the overall environmental performance of green infrastructure [

54].

Accordingly, the recent literature advocates integrative and participatory approaches that align user preferences, sustainable resource management, and urban resilience to support more equitable and functional cities [

14,

55]. Although rapid urbanisation intensifies pressure on natural systems by causing habitat degradation and increasing greenhouse gas emissions, it also creates opportunities to implement innovative practices aligned with sustainable urban planning goals [

56]. Nevertheless, the planning and evaluation of green infrastructure remain complex and context-dependent, shaped by interconnected physical, institutional, psychological, transport, and socio–cultural factors [

38]. While the benefits of green spaces are well documented, less attention has been paid to how diverse user groups assess their functions, especially in mid-sized cities in Southeast Europe. This represents a significant gap in the literature, highlighting the need for empirical insights into user-specific experiences and contextual influences in cities undergoing rapid spatial and demographic change.

Against this background, the present study aims to examine the multidimensional perceptions of use, satisfaction, and functional value of green areas among residents of Novi Sad. As one of the fastest-developing urban centres in the region, the city faces growing pressures related to urban expansion, environmental sustainability, and quality of life. Understanding how users engage with, assess, and prioritise different attributes of green infrastructure can offer valuable insights for evidence-based urban planning and support the design of more inclusive and resilient public spaces.

3. Research Methodology

The empirical research was conducted from 1 October 2024 to 1 March 2025 in the city of Novi Sad. Data were collected through an anonymous survey targeting a sample of the population with diverse age, social, and economic characteristics. A total of 1400 questionnaires were distributed, and 1080 valid responses were included in the analysis, yielding a response rate of 74.29%.

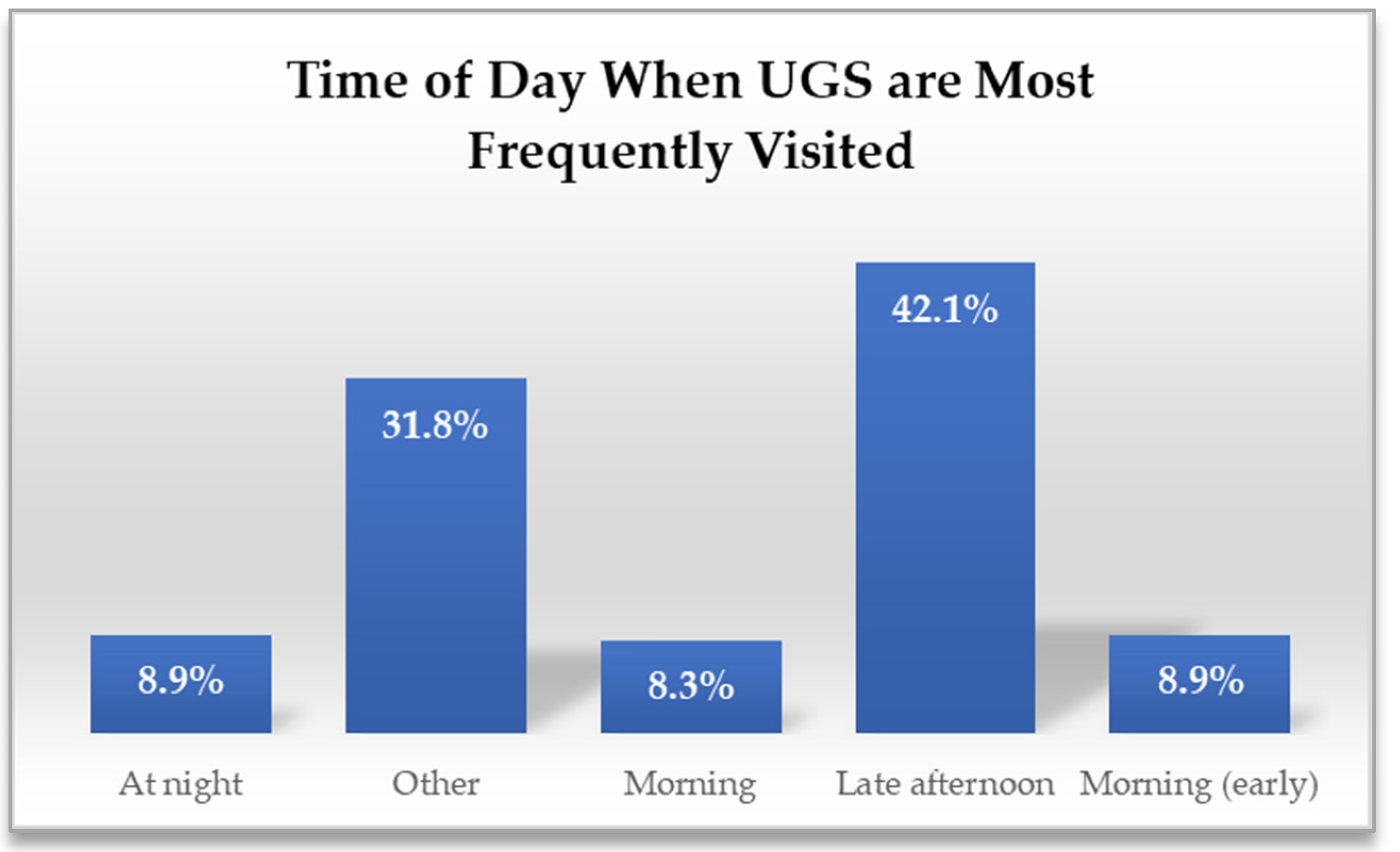

To ensure methodological comprehensiveness, a mixed-methods design was employed, combining structured quantitative data with qualitative insights derived from open-ended responses and contextual comments. The integration of both data types was achieved through triangulation, where qualitative observations were used to interpret statistical results, particularly in instances where unexpected or counterintuitive relationships were revealed through regression modelling. This approach enabled a more nuanced understanding of user experiences with urban green spaces and strengthened conclusion validity. To illustrate the research design and sequential analytical phases,

Figure 1 presents a flowchart outlining key steps, including hypothesis formulation, data collection, questionnaire structure, model diagnostics, and interpretation of results. This structure highlights how the triangulation of methods contributed to a more robust interpretation of the data and enhanced the explanatory depth of the research findings.

In order to enhance the representativeness of the findings, the sampling frame was aligned with recent census data, incorporating variations in gender, age, income levels, and household composition. Stratified sampling was applied to ensure sufficient diversity across user profiles. Special care was taken to include respondents with varying patterns of green space usage and motivations, thereby supporting more inclusive and context-sensitive subgroup analysis.

The survey instrument was designed to capture relevant sociodemographic information about respondents and their perceptions of various dimensions of urban green spaces (UGS). A Likert scale with five levels (1—strongly disagree, 5—strongly agree) was applied to all items. In total, 67 variables were included, grouped into 6 inter-related analytical areas: sociodemographic characteristics, perceptions of social and community functions of UGS, user satisfaction with UGS, evaluations of the role and significance of UGS, perceived benefits and values of UGS, and perceptions of the economic, ecological, psychological, and cultural functions of these spaces. In addition to these core dimensions, the survey also included items evaluating the perceived relevance of ESG factors for the management and long-term sustainability of UGS. ESG-related questions focused on how respondents perceive the integration of ecological sustainability, social equity, and transparent governance in UGS management. These factors are crucial for understanding how sustainable urban planning practices influence user satisfaction with UGS and their overall perception of urban green spaces as essential components of community well-being.

In order to examine the relationship between the functional aspects of urban green spaces (UGS) and user satisfaction, the following hypotheses were formulated:

H1: The economic–ecological functions of UGS have a statistically significant positive impact on overall user satisfaction.

H2: The psychological–cultural functions of UGS have a statistically significant impact on overall user satisfaction.

H3: The social and communal functions of UGS have a statistically significant positive impact on overall user satisfaction.

For the analysis of quantitative data, the IBM SPSS Statistics software version 26 was used. Descriptive statistics, Pearson’s chi-square test (χ

2), and stepwise multiple linear regression were applied. This method of regression allows for the sequential inclusion of only those predictors that have a statistically significant contribution to explaining the dependent variable. The effectiveness of this method in identifying relevant factors has been demonstrated in previous empirical analyses of complex systems [

57,

58]. The reliability of the measurement scales was tested by calculating the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, and all coefficients exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.70, confirming the internal consistency and methodological reliability of the scales used [

59].

The methodological framework applied in this study aligns with contemporary research that uses multiple regression analysis to examine user perceptions and behaviours in urban settings. Similar approaches are evident in the work of Li et al. [

60], who analysed the influence of urban green space characteristics on citizen visitation and satisfaction, as well as in Kothencz et al. [

8], where factors related to well-being and UGS perceptions were identified. Methodologically similar analyses, focusing on identifying multiple determinants of user behaviour toward ecological resources, were also employed by Vapa Tankosić et al. [

28] in their study on factors influencing the adoption of agro-ecological practices among farmers. These studies underscore the effectiveness of multiple regression in revealing complex relationships between variables and user behaviour, enabling precise modelling and a deeper understanding of urban green space dynamics. This approach offers a comprehensive framework for analysing complex systems and allows for the identification of patterns that inform both theoretical and practical applications in urban planning and sustainability. Model diagnostics, including multicollinearity tests (VIF) and 10-fold cross-validation, were conducted to ensure the robustness and generalisability of the regression models.

5. Discussion

The role of urban green spaces (UGS) in enhancing the quality of life in cities has been extensively studied, particularly in terms of their ecological, social, economic, and psychological functions. These studies frequently emphasise the significant impact of UGS on physical and mental well-being, their role in fostering social integration, preserving biodiversity, and alleviating the adverse effects of urban environments. Given the increasing emphasis on sustainable urban development, this research on user perceptions and functional assessments of UGS in Novi Sad offers valuable insights into the specific benefits and challenges associated with urban planning of these spaces.

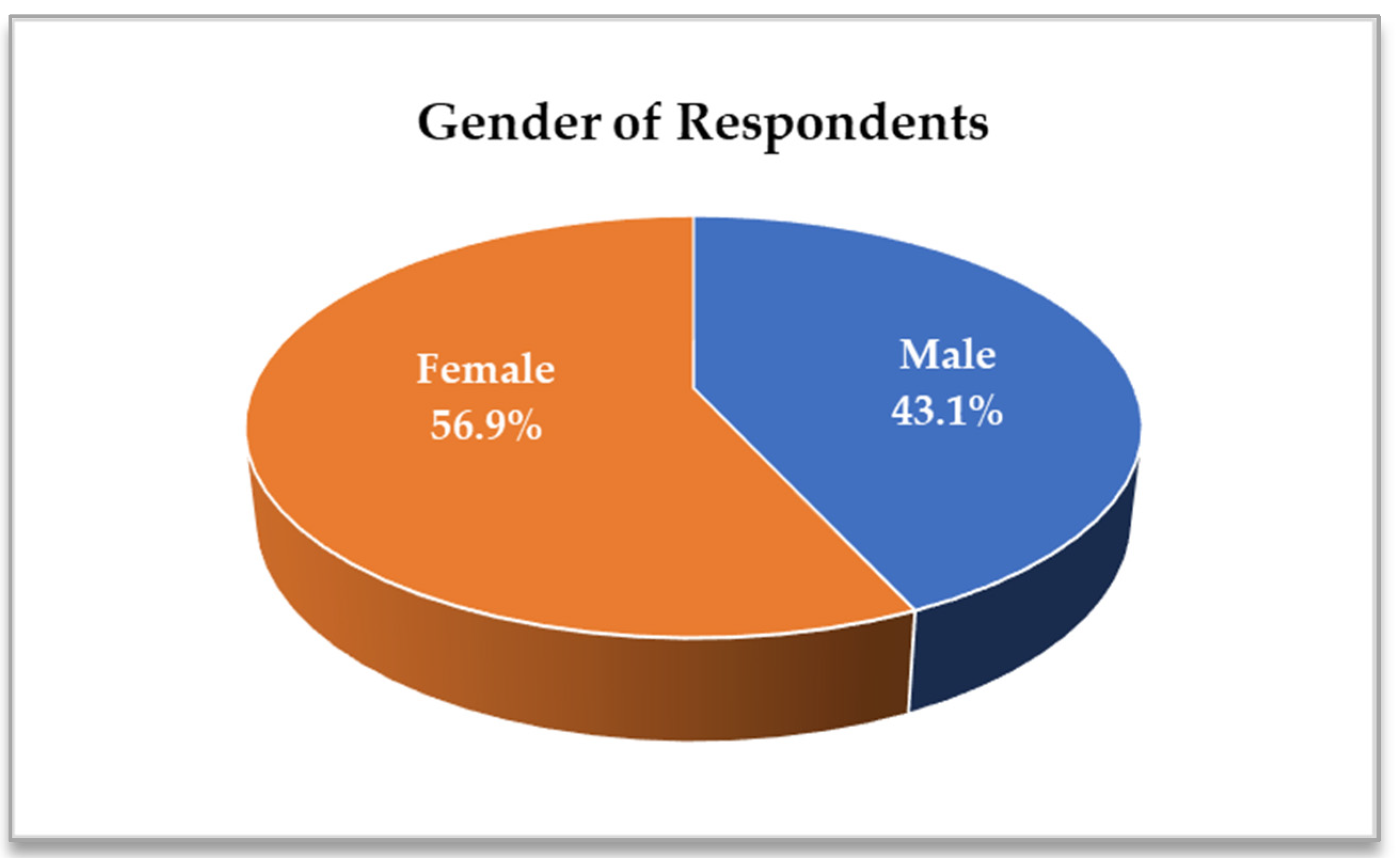

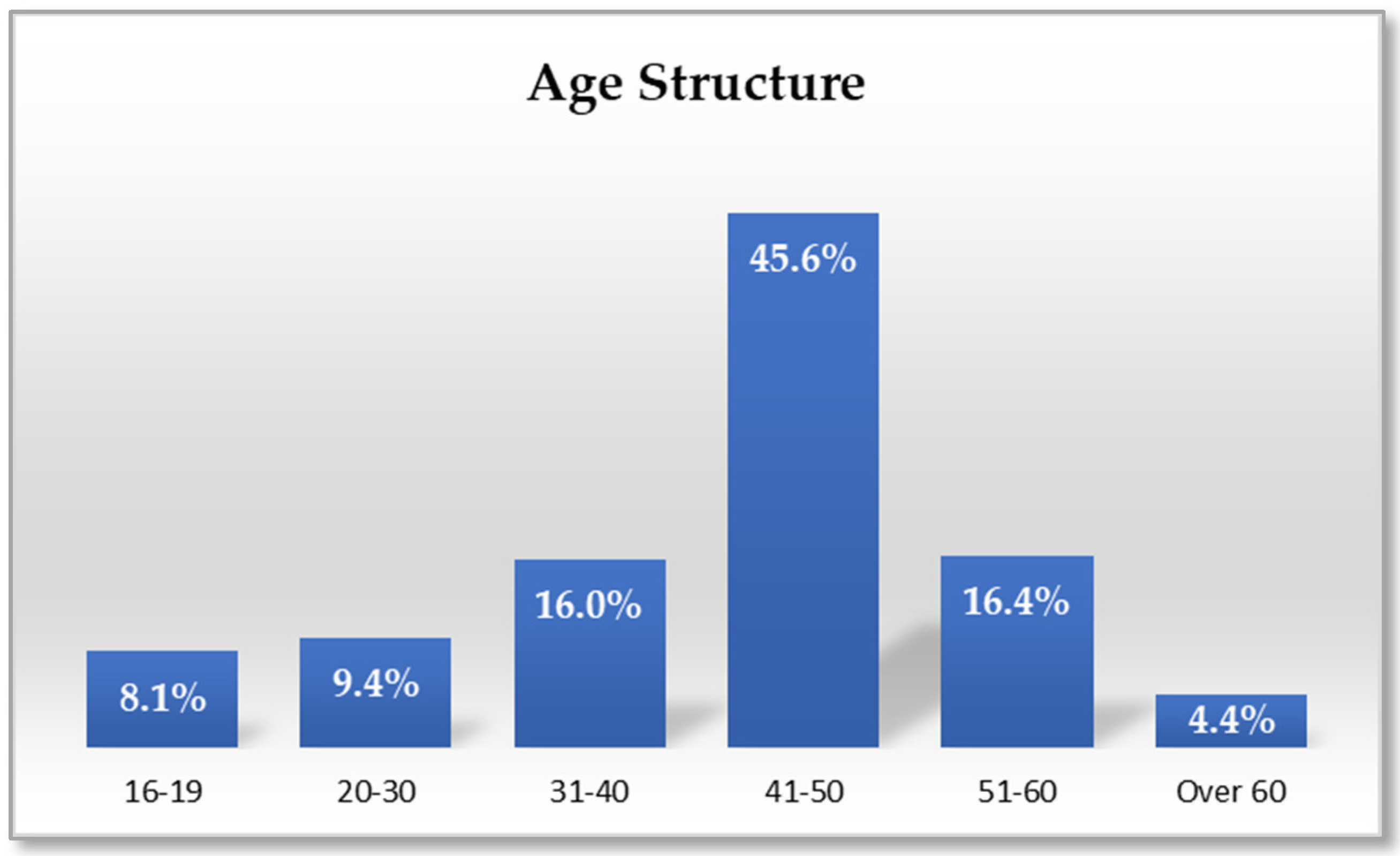

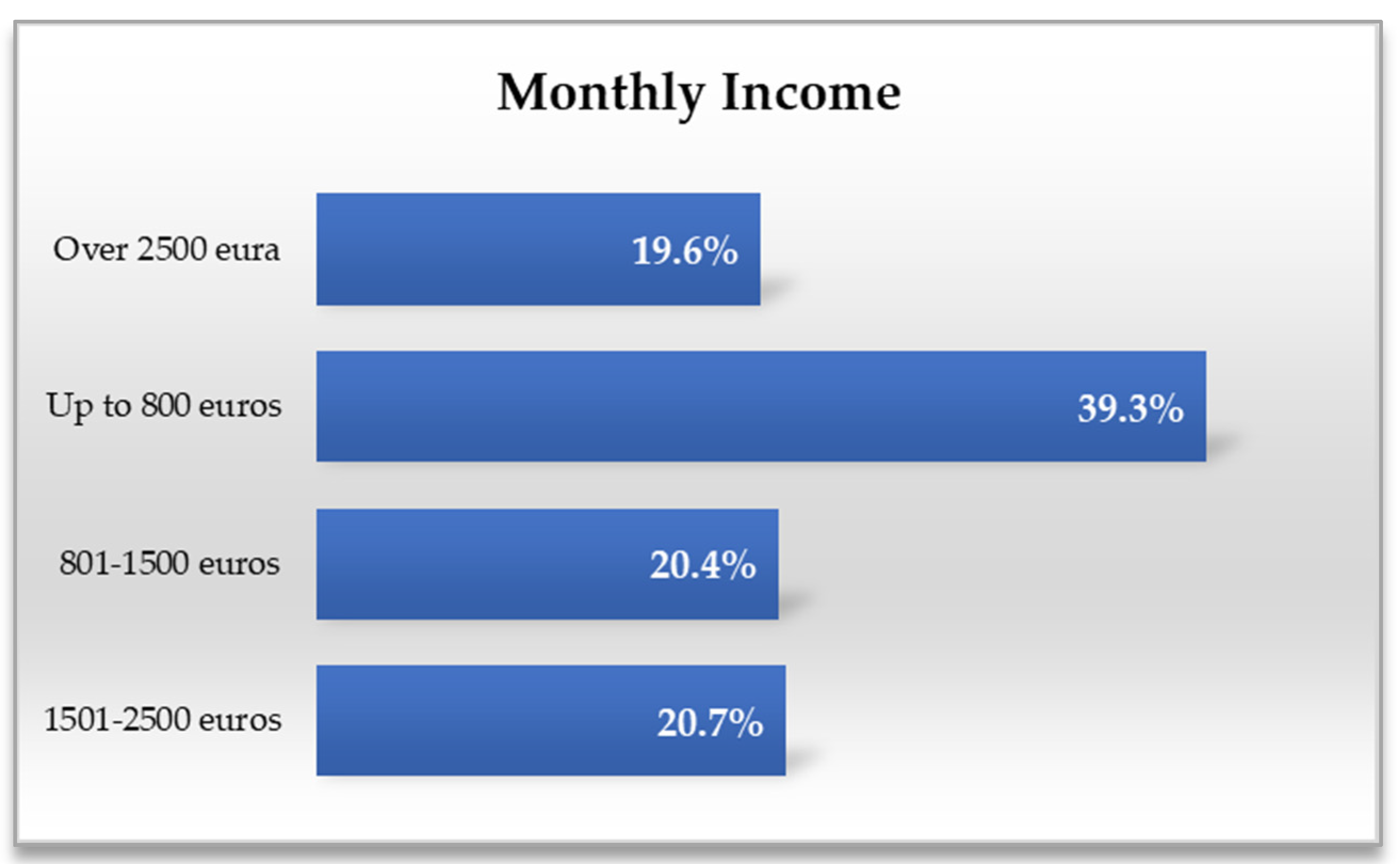

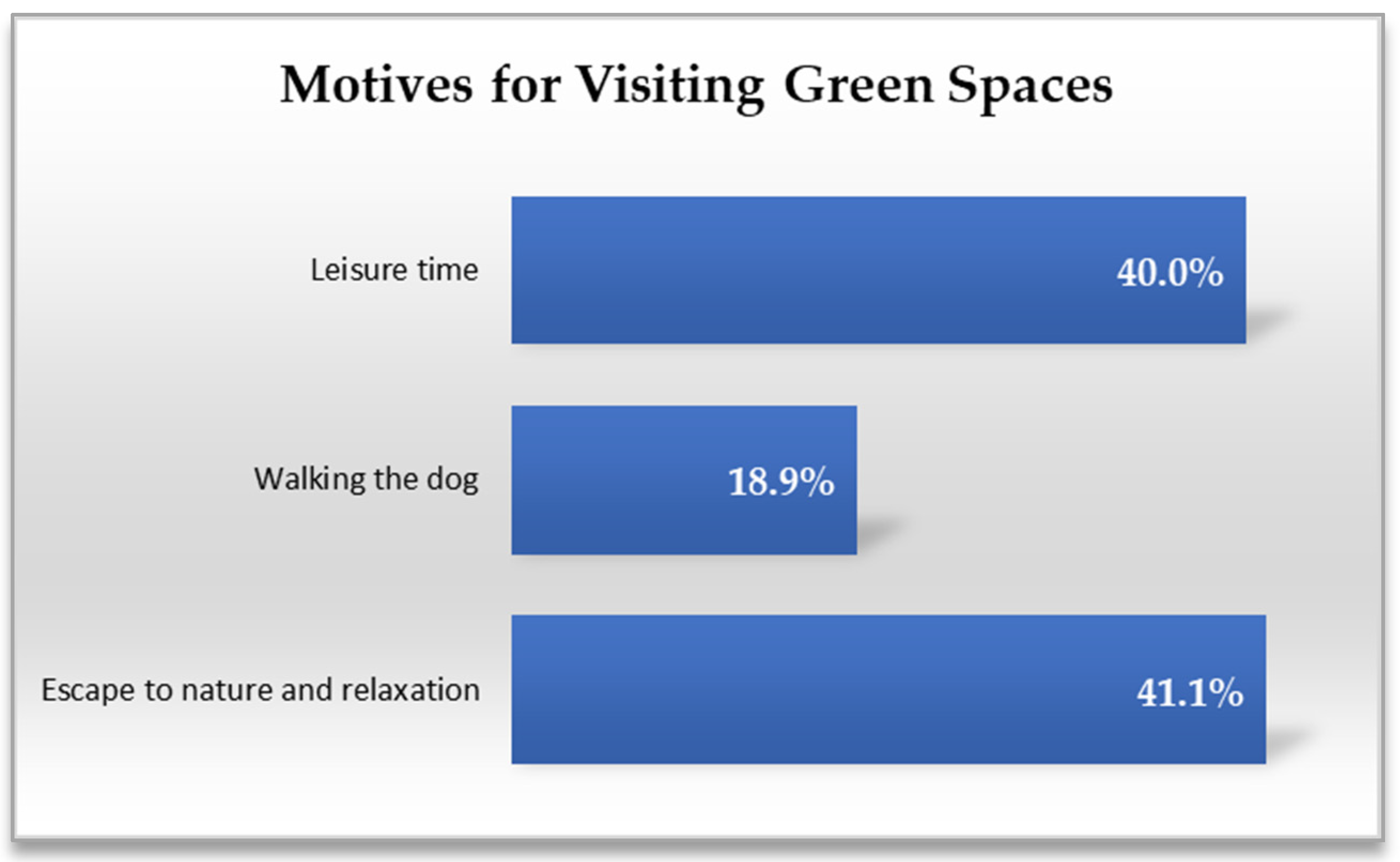

The results reveal that the majority of urban green space users in Novi Sad are women (56.9%), while men represent 43.1%. The age distribution of users reveals that they are predominantly middle-aged, with the largest proportion falling between 41 and 50 years old (45.6%), and those over 60 years old being the least represented (4.4%). Regarding monthly income, the highest number of respondents earn up to 800 euros (39.3%), while a smaller group earns more than 2500 euros (19.6%). These findings are consistent with previous studies suggesting that women are more frequent users of urban green spaces, likely due to their greater interest in health and social interactions [

45]. Additionally, older individuals and those with lower incomes tend to use green spaces less, highlighting the opportunity to improve the accessibility and inclusiveness of these spaces [

32].

The analysed perceptions of users regarding the social functions of urban green spaces indicate that UGS are recognised as spaces for social interactions, connecting individuals of various ages and cultures, and enhancing the quality of social relationships within urban environments. Furthermore, significant differences in perceptions between male and female respondents were identified, with men generally providing higher ratings. These findings highlight the role of UGS in fostering social cohesion, in line with research suggesting that green spaces are essential for strengthening social bonds and reducing social isolation [

66]. These findings are consistent with recent research by Xu et al., which confirms the role of UGS in fostering community belonging and bridging social differences in medium-sized European cities [

7]. The observed differences in perception between genders may reflect distinct needs and expectations, particularly regarding safety and privacy, which should be carefully considered when designing and adapting urban green spaces. These findings are in line with Gao et al., who identified clear gender-based distinctions in how older men and women perceive UGS in Macau, particularly in relation to children’s facilities, social activities, and landscape preferences [

17].

Users of UGS in Novi Sad express moderate satisfaction with various aspects. The highest satisfaction is observed regarding social and recreational facilities, while the lowest ratings are for safety, cleanliness, and infrastructure. Women and middle-aged individuals (41–50 years) report the highest satisfaction, while older users and those with lower incomes show lower satisfaction. These findings align with previous studies linking satisfaction to infrastructure quality, safety, and maintenance [

67]. Low satisfaction with cleanliness and safety highlights the need for increased investment in maintenance and security [

68]. Additionally, fostering partnerships between property owners and users in the upkeep and development of amenities may improve satisfaction, supporting earlier research on collaborative management [

69].

The functions of UGS in Novi Sad that received the highest ratings include stress reduction, improvement of microclimate, pollution reduction, and enhancement of overall health. These results align with previous studies highlighting the significant ecological and psychological benefits that UGS provide to users, such as reducing stress and improving mental health [

70]. Furthermore, UGS play a crucial role in supporting mental health, particularly among individuals living alone [

71]. Visitor numbers and traffic noise significantly influence user preferences for UGS, with similar preferences observed concerning psychological benefits. This indicates that targeted UGS design can address specific restorative needs of users [

72]. These findings reinforce the need for strategies that incorporate wider pathways, trees, and small urban forests, as well as the reduction of traffic noise, to optimise the psychological benefits for users. Recent studies by Ghavimi et al. also support the significance of integrating recreational and environmental values into green space design for increased user satisfaction and mental well-being [

4].

Users of UGS in Novi Sad rated the ecological and economic values of these spaces highly, including their impact on increasing property values in surrounding areas, reducing urban noise, and their cultural significance. These findings support theories that emphasise UGS as not only ecologically vital but also as having a significant economic and cultural impact on cities. The data suggest that green spaces can positively influence the real estate market and contribute to the creation of a city’s cultural identity [

73]. This confirms that investing in UGS can yield long-term economic benefits for the community. By strengthening cultural identity and economic vitality, UGS also directly contribute to the urban quality of life, particularly in rapidly developing urban centres. Similar conclusions have been reached in studies on the cultural ecosystem services of UGS, highlighting their importance for urban quality of life and public health, as well as their role in enhancing ecological awareness and fostering social cohesion. Urban green spaces, especially parks, play a critical role in improving social interaction and promoting social cohesion among visitors, further confirming the value of these spaces in modern urban communities [

74]. Moreover, UGS play an important role in social cohesion by encouraging positive social interactions that can contribute to better health outcomes through increased physical activity and social engagement [

66].

Novi Sad, often referred to as the “Serbian Athens”, is known for its vibrant cultural scene, including renowned events such as the EXIT Festival and Sterijino Pozorje, as well as cultural institutions like Matica Srpska and the Gallery of Matica Srpska. However, unlike some European cities where green spaces frequently serve as venues for organised cultural events, respondents in this study expressed expectations for more cultural activities to be hosted within UGS-NS. This perceived discrepancy between cultural expectations and actual usage may help explain the negative influence of psychological–cultural functions on overall satisfaction. A similar gap between expectation and experience was identified by Neuner et al., who noted that users often associate cultural functions with place identity, and when such associations are absent, satisfaction tends to decline [

69]. Further research could explore this divergence in more depth and assess its implications for cultural programming in urban green spaces.

The results of the regression analysis clearly indicate that the economic–ecological functions of UGS have a significant impact on overall user satisfaction, while psychological–cultural functions, although significant, exhibit a negative influence in some models. Given the strong correlation (R = 0.834) in Model 3, which incorporates socio–community functions, it can be concluded that these functions are crucial in shaping a positive user experience. These findings align with prior research that underscores the multifaceted role of urban green spaces, highlighting their significant contribution to social cohesion and mental health [

71].

The influence of socio–community functions in our study confirms that urban green spaces play a vital role in fostering social connections and reducing social isolation. This finding aligns with previous research indicating that green spaces can contribute to improved social integration and stress reduction [

66]. Although psychological–cultural functions had a negative impact in some instances, the results highlight that these aspects warrant further exploration, especially regarding user expectations and their specific needs. The apparent mismatch between expectations and user experiences, as revealed in the analysis, could explain the negative assessments in certain areas. This discrepancy likely reflects the insufficient presence or visibility of cultural infrastructure, programming, and activities in UGS-NS. While users may associate green spaces with opportunities for cultural engagement, such as public performances, exhibitions, or educational programming, the limited availability of such features in Novi Sad’s green areas might result in unmet expectations and, consequently, lower satisfaction scores for this functional dimension [

4,

69]. This underscores the need for future research to focus on the more precise design of green spaces that address the distinct social and psychological needs of users.

Through the regression model analysis and the contribution of each predictor, it is evident that an increase in socio–community functions can significantly enhance user satisfaction, aligning with studies confirming that social cohesion and interactions are key to improving health and quality of life [

73]. These findings carry significant implications for strategic urban planning and the effective implementation of green infrastructure, emphasising the need for a holistic approach that integrates economic, ecological, psychological, and social dimensions. Future research should further explore how specific characteristics of urban green spaces, such as size and vegetation type, may influence these dimensions, as well as how such spaces can be more effectively utilised to enhance environmental quality and promote social integration.

Considering the pivotal role of socio–community functions in shaping user satisfaction, it is crucial to emphasise that urban green space planning should prioritise designs that encourage social cohesion and foster positive social interactions. Future research should focus on the specific characteristics of urban green spaces that impact different demographic groups, as well as the long-term effects on mental health and social integration. Additionally, well-designed urban green spaces are a vital component of sustainable urban development as they help mitigate the adverse effects of urbanisation, such as pollution and climate change, while enhancing the overall quality of life in cities. Studies confirm the importance of urban green spaces for the real estate market, cultural identity, and their positive influence on social cohesion and mental health [

73,

74,

75]. These findings underscore that investments in urban green spaces can bring long-term economic and social benefits, highlighting the need for strategies focused on the sustainable management and planning of green spaces in urban areas. In this context, the integration of ESG factors is becoming increasingly important as it supports not only the ecological but also the social dimensions of user satisfaction and enhances the governance practices in urban green space management. These findings are in line with research by Sondou et al., which emphasises the importance of strengthening participatory governance in urban planning to improve trust, inclusiveness, and responsiveness to local needs [

21]. Incorporating ESG-related practices into urban planning frameworks ensures that green spaces are managed in a way that meets sustainability goals, fosters social inclusivity, and promotes long-term ecological health [

19,

29,

30]. This is further supported by recent research on the integration of digital tools and AI-powered systems in public and educational sectors, which shows their potential to enhance transparency, stakeholder engagement, and strategic decision-making processes [

76]. The integration of AI tools into different urban planning phases can further support public participation and streamline formal procedures, offering planners analytical, textual, and visual assistance, without replacing human decision-making, as emphasised by Othengrafen et al. [

22].

The findings of this study reaffirm the multidimensional value of UGS, especially their capacity to support sustainability, inclusivity, and public health objectives, with a particular emphasis on their socio–community, ecological, and psychological functions. By integrating comparative research insights and recognising the growing importance of participatory approaches and digital tools, this analysis offers a deeper understanding of user satisfaction in urban environments. The incorporation of ESG principles and AI-supported mechanisms into planning processes presents further opportunities to enhance governance quality, transparency, and social inclusiveness. These perspectives provide a strong foundation for the concluding considerations and recommendations aimed at fostering more sustainable and socially responsive urban green space management.

6. Conclusions

This study examined how the functional characteristics of urban green spaces (UGS) in Novi Sad influence user satisfaction, confirming their contribution to quality of life and sustainability. The analysis focused on the impacts of ecological, economic, psychological, and socio–community dimensions, underscoring the importance of a multidimensional approach to evaluating the sustainability of these spaces. The findings indicate that users highly value the ecological, economic, and social functions of UGS, particularly those related to stress reduction, improved microclimates, pollution mitigation, and enhanced social cohesion. These factors not only support improvements in physical and mental health but also significantly enhance the urban quality of life by shaping positive user experiences and fostering social interaction.

The increase in user satisfaction with UGS in Novi Sad reinforces the need to strategically integrate a broader range of functional characteristics into the planning and development of these spaces. Sustainable management and inclusive design of urban green spaces are essential for securing long-term ecological, social, and economic benefits. Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) factors are key to enhancing the planning, coordination, and maintenance of UGS as they enable better consideration of community needs and ecological responsibility.

Urban planners could prioritise targeted investments in safety infrastructure and cultural programming within UGS to address identified gaps in satisfaction, particularly among older and lower-income users. Additionally, participatory planning mechanisms and the strategic use of digital tools could support greater inclusiveness and responsiveness in green space governance. These findings provide actionable guidance for local authorities in aligning urban green space planning more closely with community priorities and long-term sustainability objectives.

Based on this research, it is recommended that urban planners and decision-makers continue to implement strategies that improve access to and usage of UGS, including reducing access barriers, improving infrastructure, and engaging the community in the maintenance and use of these spaces. Moreover, the integration of ESG factors in the strategic planning and management of UGS will further contribute to the sustainability and long-term well-being of urban communities.

Further research should focus on the specific characteristics of UGS that have the greatest impact on different demographic groups, as well as the long-term effects on mental health and social integration. Additionally, future studies can aid in better understanding and evaluating the various functional characteristics that contribute to the overall quality of life and sustainability of urban environments, with ESG factors playing a crucial role in enhancing the management of these spaces. This study has certain limitations. The findings are based on data collected from a single urban setting, Novi Sad, which may affect their applicability to cities with different socio–cultural, economic, or spatial characteristics. Moreover, the cross-sectional design does not allow for insights into seasonal or longitudinal changes in user perceptions. The governance component within the ESG framework was assessed through perceptual indicators, without direct evaluation of institutional performance. Future research should integrate user-centred insights with institutional and spatial assessments, employing longitudinal designs to more accurately capture the dynamic relationships between green space characteristics and user outcomes.