1. Introduction

In recent times, addressing food waste has emerged as a significant concern, as reducing it aligns with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly with SDG 12.3, which seeks to halve per capita global food waste at the retail and consumer levels by 2030, while also reducing food losses throughout production and supply chains, including post-harvest losses [

1]. Food waste (FW) can be referred to as “any food, and inedible parts of food, removed from the food supply chain to be recovered or disposed of (including composted, crops ploughed in/not harvested, anaerobic digestion, bio-energy production, co-generation, incineration, disposal to sewer, landfill or discarded to sea)” [

2] (p. 6). Each year, approximately 1.3 billion tons of food intended for human consumption are lost or wasted globally, which accounts for roughly one-third of the total production [

3] (p. 4). This inevitably results in the inefficient use of vast quantities of resources in food production, as well as the consequential emission of greenhouse gases due to FW or loss during production [

4]. In 2022, the European Union (EU) generated over 59 million tonnes of FW, meaning 132 kg of FW per inhabitant. Household FW accounted for about 54% of the total share, the processing and manufacturing industry accounted for 19% of the overall share, and the remaining share, slightly more than a quarter of the total FW, was derived from the primary production sector (contributing 8% to the total FW), restaurants and food services (contributing 11% to the total), and retail and other food distribution sectors (contributing 8% to the total). In Slovenia, during the same reference year, a total of 150,839 tonnes of FW was generated, with the restaurant and food sector contributing approximately 55,839 tonnes, representing around 37% of the overall waste [

5].

Although food loss and waste (FLW) are generated at several stages of the food supply chain (FSC), the hospitality and food service sector (HaFS) represents a critical intervention point due to its significant contribution to plate waste [

6]. Overall efforts to address FW have become increasingly important in the pursuit of sustainability, particularly within the food service sector. As consumer awareness of environmental issues grows, there is a growing interest in exploring attitudes toward innovative strategies to minimise FW [

7,

8,

9]. Despite the growing body of literature addressing FW, comprehensive and detailed studies exploring consumer behaviours, attitudes, and motivations in Slovenia, especially within the food service sector, are yet very few. The research conducted as part of the “Food is not Waste” project (sl. “Hrana Ni Odpadek”) represents one of the few in-depth studies in Slovenia that aims to understand the factors influencing consumers’ motivation to reduce food waste. This study primarily focused on household-level consumers’ motivations for food waste reduction and explored food service waste from the perspective of food service providers [

10], rather than the consumers in food services.

The “Food is not Waste” study found that 94% of respondents valued environmental protection but shifted responsibility for reducing food waste to the state and corporations. While personal norms and economic factors influenced behaviour, environmental awareness and social pressure were less impactful. The HoReCa sector reported a 15.4% food waste rate, mainly due to large portion sizes and unappealing dishes. However, practices like offering smaller portions or encouraging leftover take-home were rarely implemented. Food service providers focused on strategies like and employee education, but less on consumer engagement or donating food.

Other recent studies in Slovenia have explored various aspects of FW, including household FW, focusing on the factors driving food disposal at the household level [

11], FW from the perspective of food service providers, highlighting operational challenges in reducing waste but not focusing on consumer behaviour in restaurants [

12], or looking into sustainable consumer behaviours more generally [

13].

However, there remains a gap in understanding consumer attitudes and behaviours specifically within the food service context, where decisions around food waste are often influenced by a unique set of motivations, opportunities, and abilities, as highlighted in previous studies on consumer food waste behaviour at household level [

14,

15]. A lot of research offers some insights into the causes of FW and proposes preventative techniques based on consumer attitudes and behaviours [

16,

17,

18] but often overlooks the examination of customers’ attitudes and behavioural intents towards environmentally responsible practices in food services, despite the increasing popularity of “green” movements [

19]. Among these practices, taking leftovers home has gained particularly significant attention as a practical method for reducing FW. Some previous research has highlighted consumers’ motivations to take leftovers home are influenced by a combination of societal and personal factors. Societal motivations primarily include reducing FW and concern for the environment, while personal factors encompass sensory appeal, cost awareness, and the practicality of consuming leftovers for another meal to save time and money [

20,

21]. Nevertheless, the research gap highlights the importance of understanding the potential factors influencing consumer behaviour related to FW and understanding their willingness to practice FW reduction measures at the food services level. Another critical intervention point is the lack of attention to consumer FW in smaller or developing countries [

10]. Studies in Slovenia, for example, remain limited in scope, yet deserve attention given the potential to reduce FW in its hospitality sector.

This research aims to fill this gap by examining Slovenian consumers’ FW-related behaviours, as well as attitudes and willingness to engage in FW reduction practices within food service settings, providing valuable insights for reducing FW at the food service level. This study bridges the gap by focusing on Slovenian consumers’ behaviours and attitudes toward food waste in the food service context—an area that has not been extensively explored in the existing literature. Unlike the “Food is not Waste” project, which studied household-level motivation and food service waste from the organisational side, this study focuses specifically on consumer behaviour in food service settings, examining how motivation, opportunity, and ability influence consumers’ willingness to engage in food waste reduction strategies in the context of dining out.

Therefore, our present research interest is in describing the landscape of consumers’ habits, motivations and attitudes at the food services level in Slovenia. The objective of this study is to explore how Slovenian consumers perceive and engage with food waste reduction strategies when dining out, by examining the role of motivational, ability, and opportunity factors, together with socio-demographic characteristics. The study applies the Motivation–Opportunity–Ability (MOA) framework to analyse consumer attitudes toward three specific FW reduction strategies: (1) leftover handling (taking leftovers home), (2) portion size reduction, and (3) pre-ordering meals.

Accordingly, the study aims to address the following research questions:

RQ1: What are the main motivational, opportunity, ability, and socio-demographic factors influencing Slovenian consumers’ willingness to take leftovers home?

RQ2: How do motivational, ability, opportunity, and socio-demographic characteristics, including portion importance, affect consumer acceptance of portion size reduction?

RQ3: To what extent do motivation, opportunity, ability, and socio-demographic factors influence consumers’ acceptance of pre-ordering as a strategy to reduce food waste?

2. Conceptual Framework

Vittuari et al. (2023) [

22] outlined that the MOA framework considers food waste an unintended consequence of iterative decisions and behaviours driven both by internal (individual) and external (social and societal) factors. Initially designed for marketing research, the MOA framework was proposed in 2016 within the EU Refresh project to systematically analyse drivers of consumer food waste behaviour [

23,

24,

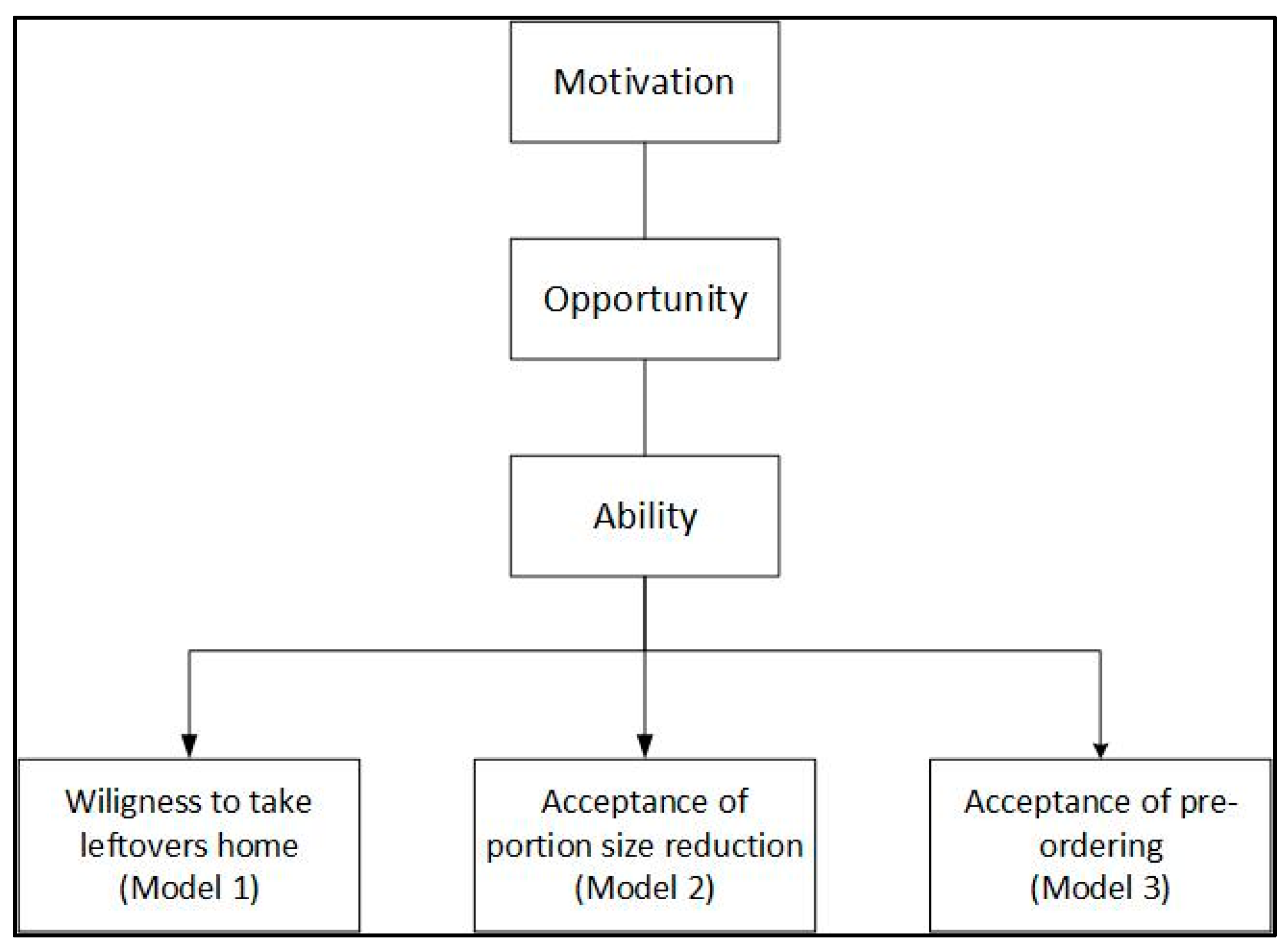

25]. The framework is based on three theoretical constructs—motivation, opportunity, and ability (

Figure 1). Motivation refers to what drives the individual to perform certain actions and is influenced by awareness of consequences, personal attitudes, and social norms. Ability is the knowledge, skills, and capacity to change behaviour, such as for example the capability of planning the purchase of food items, knowing how to prepare food, and storing techniques. Opportunity refers to the availability and accessibility of materials and resources to change behaviour such as time, technology, and infrastructure. This study focuses on the motivation component within this framework.

Motivation is driven by an individual’s awareness and attitude about food waste. Becoming aware of food waste refers to becoming aware of the problem of food waste and, therefore, the social, economic, and environmental impacts are often the focus. It is not uncommon for an individual to underestimate their role in food waste production. For example, according to a Eurobarometer report of 2014, 86% of survey respondents reported that they believed they wasted “relatively little” amounts of food in their household [

26] (p. 4) (The wording “relatively little” means no more than 15% of food bought). However, afore mentioned statistics in

Section 1 highlight that household FW in fact accounted for about 54% of the total food waste in the EU in 2022. How aware or problematic an individual deems food waste to be may affect their attitude toward the issue and play a role in their motivation to address it.

Motivation cannot be fully understood without also examining the role of social norms. Via a literature review, four main social norms specific to food waste were identified: sub-optimal food/undesirable food quality, good provider identity, portion size and food affluence, and associations between food waste behaviour and socio-economic status [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. They are broadly defined as:

Suboptimal Food: Not buying, utilising or eating food due to sensory deviations, such as appearance or taste.

Good Food Provider Identity: Desire to be a good parent or host and, therefore, emphasis is placed on the amount of food provided, often exceeding what is needed.

Portion Size and Affluence: Portion size is taken to indicate how much is considered socially acceptable to eat, without being considered excessive (although it might be excessive in reality).

Food Waste Behaviour and Socio-Economic Status: Associations that are made about one’s socio-economic status based on their actions regarding food purchase (e.g., if going to food banks might be considered poor for example), preparation, and consumption.

Its purpose was to gain a thorough understanding of consumer habits and motivations related to FW within the context of food services, as well as the causes and societal conventions that impact these patterns for consumers.

Disclosing the mechanisms and the driving forces behind behaviours that lead to the intended and unintended generation of food waste is essential to reach the desired outcomes in terms of food waste reduction and prevention. From 2010 onwards, a considerable amount of literature was written on what drives food waste, from complex socio-economic contexts, daily habits, or even the mere ability and opportunity to address it [

33,

34,

35]. From this literature, food waste is recognised as a complex result of multiple and interconnected behaviours taking place at different moments and stages of the food supply chain. Several theoretical and conceptual frameworks were developed to understand this complexity, including the MOA framework.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design and Methodology

The study referred to in this paper was conducted in June and July of 2023. The methodology for data collection in this study involved conducting an online survey via the online tool JotForm.

In the research, the MOA framework was applied to analyse Slovenian consumers’ attitudes and behaviours toward three FW reduction strategies:

Acceptance of taking leftovers home;

Acceptance of portion size reduction;

Acceptance of pre-ordering meals.

Figure 2 shows the conceptual framework of this study, which is based on the MOA model. It illustrates how consumer behaviour related to food waste reduction in restaurants is influenced by three main factors: motivation (e.g., ethical and environmental concerns), opportunity (e.g., availability of FW reduction options), and ability (e.g., knowledge and skills). These factors are used to explain three key behaviours analysed in this research: (1) willingness to take leftovers home (Model 1), (2) acceptance of portion size reduction (Model 2), and (3) acceptance of pre-ordering (Model 3). Each of these behaviours is treated as a separate dependent variable in the empirical analysis.

3.2. Questionnaire Development and Validation

The questionnaire was developed by the authors, drawing on a review of the relevant literature. Its design was further enriched through input from project partners as part of the EU-funded CHORIZO project, which financed and guided this study. The instrument covered four key themes: (1) food waste-related behaviours and dining habits, (2) leftover decisions, (3) attitudes toward pre-ordering, and (4) portion size perceptions. Additional questions were included to capture socio-demographic and economic characteristics.

The final instrument comprised 47 items, including Likert-scale questions (1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree), multiple-choice questions, and binary responses. The section on FW-related choices and behaviours focused on general dining habits and attitudes toward FW. The section on leftover decisions looked at motivations and barriers influencing the decision to take leftovers home, including ethical considerations, practical constraints, and social norms. The pre-ordering section explored respondents’ willingness to engage in pre-ordering practices under various conditions, providing insights into preferences for convenience and economic incentives. Similarly, the portion size sections investigated portion satisfaction, consumers’ attitudes toward portion size reduction as a strategy to minimise FW, and the balance between meal satisfaction and waste reduction. Additionally, the questionnaire included demographic and socioeconomic information (e.g., gender, income, education level), to better understand respondents’ behaviours and preferences.

To assess clarity and relevance, the questionnaire underwent an internal validation process within the research organisation. It was tested among a group of staff members who were not involved in the study and did not participate in the final survey. Their feedback informed minor refinements to the wording and structure of several questions, helping to improve the instrument’s face validity and readability prior to public launch.

It is important to note that, while the results reported in this paper are based on an anonymous online survey, the responses may reflect a social-desirability bias, which means that the answers were crafted to satisfy societal expectations or comply with perceived standards. While this is important to recognise, it is also an inherent issue in any research, and it is unlikely that such bias will be totally eliminated.

3.3. Sampling Strategy and Sample Size

A voluntary response sampling technique was employed. The survey was disseminated through multiple channels, including social media platforms, professional networks, and collaboration with Slovenian food, consumer, and sustainability organisations. To ensure the appropriateness of the respondents, inclusion criteria were defined as:

Participants who did not meet these criteria or submitted incomplete surveys (more than 90% missing data) were excluded.

The sample included participants from all major Slovenian regions, covering both urban and rural areas. The socio-demographic composition of the sample was deliberately broad to represent consumers across different social strata. Variables collected included the following:

The sample (

Table 1) reflects a diverse population in terms of age, education, and income, thereby enhancing the generalisability of the findings. Nevertheless, the use of voluntary sampling may limit full representativeness, which is acknowledged as a limitation. The sample of the study shows an even split between male (50.9%) and female (49.1%) respondents, indicating a balanced representation of gender in the study. The sample includes a small but significant proportion of the older generation (1936–1949), a significant proportion of the middle-aged demographics (1950–1979), the largest segment falls into the 1980–1989 birth group, and finally, 22.3% of the sample is made up of young respondents (1990–2005), demonstrating a diverse age range. A small percentage of respondents reported no formal education, indicating a well-educated sample. A notable percentage completed only primary education, whereas the majority completed at least secondary school. A considerable percentage has pursued higher education, with both undergraduate and postgraduate qualifications well represented, while a minor fraction falls into other education categories, demonstrating educational diversity. Looking at household income, it is clear that the minority falls into the lower income bracket, while the majority falls into the moderate-income range, indicating a middle-income sample. A smaller but considerable proportion of respondents fall into higher income categories. The majority of people rely on their employment income.

3.4. Data Preprocessing

The data preprocessing involved removing two cases where more than 90% of the variables had missing values, leaving a sample size of 802 for the final analysis. Subsequently, all variables were refactored into a numeric format to facilitate quantitative analysis; given the ordinal nature of the majority of variables, no additional processing was necessary. To gain insights into the distribution patterns of variables under scrutiny, frequency graphs were created using SPSS software (Version 29.0.1.1 (244)). These visual representations aided in examining patterns or trends in the data, allowing for a clearer understanding of the underlying distributions.

In accordance with the MOA framework, three composite scales were developed to operationalise the constructs of motivation, opportunity, and ability related to food waste reduction. All scale items were measured on 5-point Likert scales (1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree) and were combined using arithmetic means to form the scales.

The Motivation Scale consisted of four items assessing personal attitudes and motivations to prevent food waste (e.g., “It is good not to waste food,” and “Bringing food home saves money”). The scale demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.548).

The Opportunity Scale was composed of three items assessing perceptions of external conditions enabling food waste reduction, such as the availability of packaging for leftovers and portion size flexibility. However, the scale showed low reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.081), suggesting that the items may not consistently capture a single latent construct. The weak internal consistency may indicate that some items do not align well with the core concept of opportunity or that they do not reflect the intended dimension of the MOA framework effectively. Given the exploratory nature of this study, the Opportunity Scale was retained as is, and we acknowledge this as a limitation. This limitation is considered when interpreting the results.

The Ability Scale consisted of three items capturing consumers’ self-efficacy regarding portion control and leftover management (e.g., “I stop eating when I’m full even when I am eating something I love”). This scale showed acceptable reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.659).

The scales were subsequently used as independent variables in the regression models. An overview of the constructs and corresponding variables included in the regression models is provided in

Table 2.

3.5. Ethical Considerations

In order to adhere to ethical research practices, and to abide by the EU GDPR, participants in the survey were provided with a consent form providing:

Explanation of the main objectives of the survey;

Guarantee of data confidentiality and anonymity;

Reassurance of the voluntary nature of their participation.

To formalise their agreement, participants were required to anonymously affirm that they had read and understood the consent form. It was underscored that participation was entirely voluntary, with participants retaining the autonomy to withdraw at any point without the need for justification. They were also reassured that withdrawing from the study would bear no negative consequences and would not impact any of their rights.

4. Results

4.1. Dining Frequency and Its Relationship to FW

The frequency of dining out among Slovenian consumers varies considerably. More than half of respondents (52.6%) dine out only one to two times per month or less, suggesting that eating out is largely an occasional activity. About 19.0% report dining out weekly, while smaller groups visit restaurants more frequently, with 15.7% dining out three to four times a week, and 12.8% dining out more than five times per week.

It is crucial to clarify that when discussing FW in our results, we are particularly referring to plate waste, meaning uneaten leftovers remaining on plates.

As shown in

Table 3, most respondents (55.9%) report leaving less than a quarter of their plate as leftovers. A higher share of females (61.1%) fall into this category compared to males (50.9%). On the other hand, males are more likely to finish their meals completely, with 36.6% of male respondents reporting no leftovers, compared to 20.6% of females. Although there are differences by gender, the general pattern shows that the majority of diners leave small amounts of food uneaten. It is important to note that these answers are merely subjective assessments provided by the respondents.

When looking at FW behaviour through the lens of dining frequency, results show that infrequent diners may treat dining out as a special occasion and consequently overestimate their portion needs, leading to greater plate waste. This is supported by the results, showing that individuals who dine out less frequently (e.g., less than once a month) are more likely to leave larger portions of food uneaten, with 3.2% of this group leaving between a quarter and half a plate of food compared to the overall average of 1.8%. Conversely, frequent diners, who have a more regular presence in restaurants, demonstrate better habits around portion estimation and consumption. Notably, 50.8% of respondents dining out five to six times a week report finishing their meals completely, the highest proportion among all frequency groups.

4.2. Factors Influencing Food Choices

Before examining food waste-related behaviours, it is important to understand which factors primarily influence consumers when ordering meals. As shown in

Figure 3, taste emerged as the most decisive factor, with 53.2% of respondents rating it as “most important” and another 33.6% as “important”. Food appearance (75.1% combined “important” or “most important”) and menu variety (62.5%) were also relevant considerations. Portion size was rated as “most important” by 21.6% and as “important” by 32.2% of respondents, showing that while not the leading factor, it is still a notable aspect in dining decisions. Seasonal or periodic changes to menus were considered less influential.

Gender differences in these preferences reveal interesting trends. Men placed significantly greater importance on receiving larger portion sizes compared to women, and women placed greater importance on the seasonal or periodic changes in the menu compared to males. Similarly, when asked about reasons that would discourage a revisit to the restaurant, gender indicates a moderate influence on the reason. The results reveal a statistically significant association (p < 0.001). The strength of the association, measured by Phi = 0.214, indicates a moderate relationship between gender and the likelihood of being discouraged by small portion sizes. “I received portion sizes that are too small”, with men attributing greater significance to this factor. Specifically, 51.2% of men indicated they were “extremely likely” to be discouraged by small portion sizes, compared to 40.9% of women, demonstrating again that men place more significance on portion size compared to women.

4.3. FW-Related Behaviour

The survey reveals that consumer behaviour regarding finishing meals at food service establishments is shaped by both practical and personal factors. The most common reasons for leaving food uneaten were poor food quality and excessively large portions (

Figure 4). Specifically, 28.6% of respondents agreed that poor quality was a decisive factor, while 52.2% indicated it partly influenced their decision. Similarly, 22.7% fully agreed that large portions contributed to leftovers, with 54.7% partly agreeing. Other reasons, such as dieting, politeness, or social image, were generally less influential.

Conversely, several factors encouraged meal completion (

Figure 5). The strongest motivator was the belief that food waste is bad, with 64.2% of respondents at least partly agreeing that this influences them to finish their meals. Hunger also played an important role, followed by influences from cultural upbringing and the desire to obtain value for money. Social pressure was relatively unimportant, with only a minority citing it as a significant reason to finish their meals.

Cultural norms also play a significant role, as 10.2% agreed they were taught to finish everything on their plate, and 42.8% partially agreed. This suggests a connection between eating habits and cultural norms and cultural upbringing. Economic considerations also feature prominently, with 11% strongly agreeing that finishing their meal ensures they get their money’s worth and 30.6% partially agreeing with this as well. And lastly, social pressure is another factor. However, the majority of respondents do not consider social judgment a major motivator in their eating behaviour. Only 4.4% agreed that fear of judgment from others at the table impacts their decision, and 15.8% partially agreed with this factor.

4.4. Attitudes Toward FW Reduction Measures

4.4.1. Attitudes Toward Taking Leftovers Home

Our study looked into the attitudes and behaviours surrounding the act of taking leftover food home, among other objectives. The findings reveal diverse behaviours regarding requesting leftover food. Approximately 35.8% of respondents consistently opt to have their leftovers wrapped, showcasing a proactive stance toward FW reduction. Another significant portion, around 38.4%, does so only occasionally, indicating less consistent but still mindful behaviour. However, approximately 25.8% of respondents do not request leftover food to be wrapped.

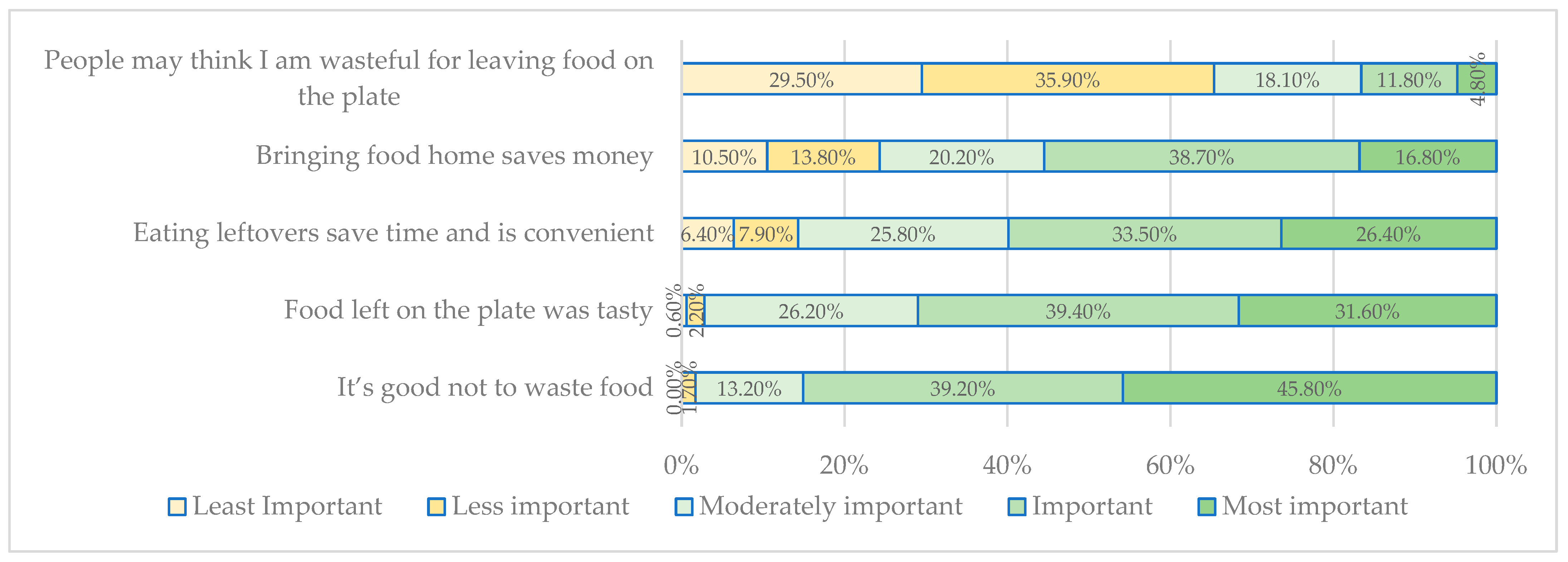

When exploring motivations (

Figure 6), the leading driver for taking leftovers home is the desire to reduce food waste, with 45.8% identifying it as the most important factor and 39.2% rating it as important. Taste and enjoyment also play a key role, with nearly 70% citing it as important or very important. Practical considerations, such as convenience and time-saving, were relevant for about 60% of respondents. While economic factors, like saving money, were less decisive, they still influenced a significant share of consumers. In contrast, social judgment—fearing negative perceptions for leaving food uneaten—had only a minor influence.

Respondents also reported various reasons for not taking leftovers home. The most common was poor food quality, reinforcing the importance of taste in consumer decisions. In addition, restaurant-imposed barriers (e.g., not offering leftover wrapping) and perceptions of limited economic value from saving leftovers were frequently mentioned. Some consumers also cited personal preferences, such as a preference for cooking at home or concerns about food safety when consuming leftovers.

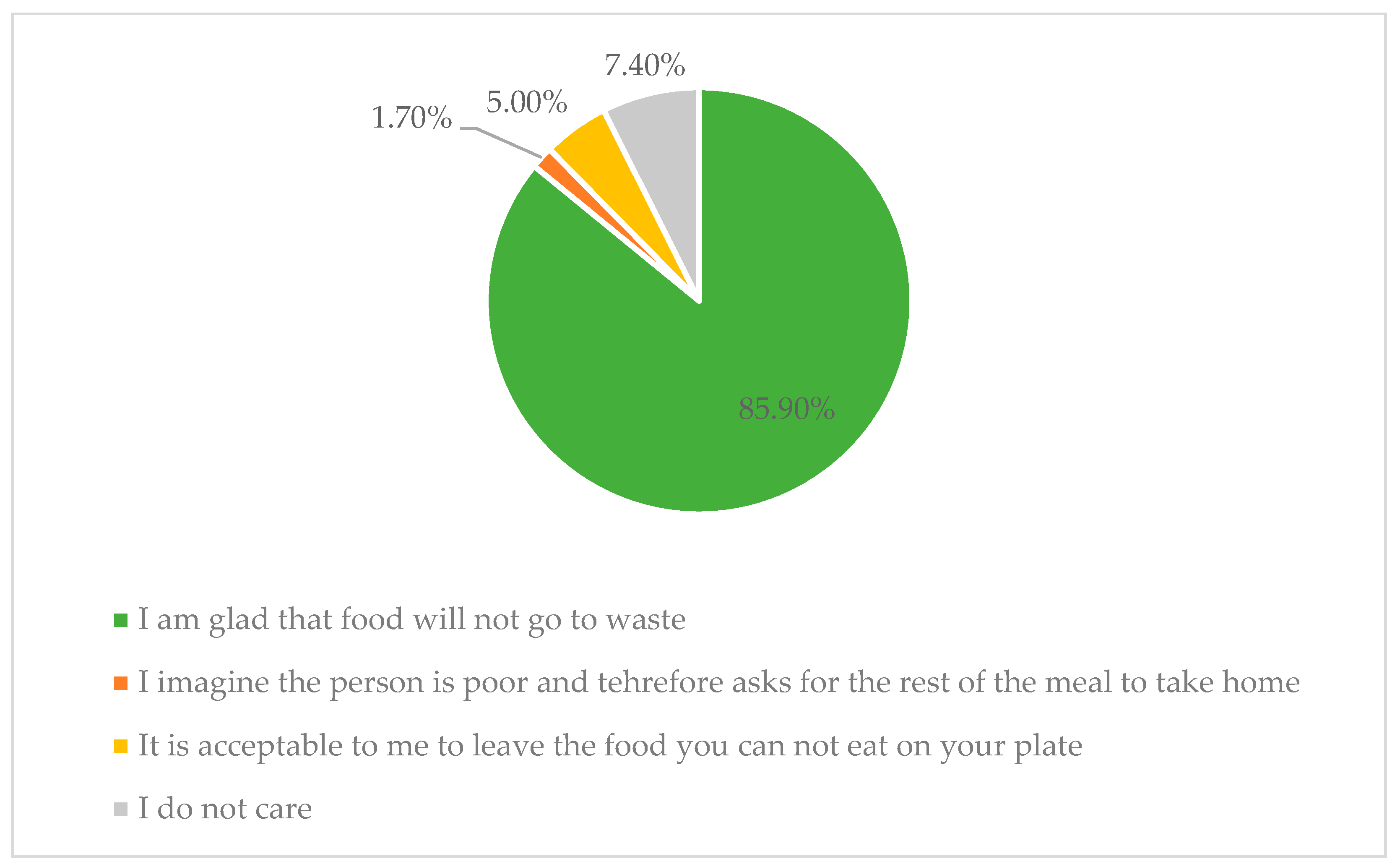

Importantly, the study also examined perceptions of others taking leftovers home (

Figure 7). The majority (85.9%) expressed positive attitudes, agreeing that they are glad when food does not go to waste. Only a small fraction associated taking leftovers home with poverty or social stigma.

An interesting but predictable correlation between attitudes regarding peers taking leftover food and the practice of requesting the leftover food to be wrapped can be observed. The results reveal a statistically significant association (p < 0.001). The strength of the association, measured by Phi = 0.380, indicates a moderate positive relationship between these variables. Respondents who expressed satisfaction with peers preventing FW (“I am glad that food will not go to waste”) were significantly more likely to request their own leftovers to be wrapped. Among those who consistently requested leftovers to be wrapped, 94.8% agreed with this sentiment, as did 92.2% of those who occasionally requested leftovers. In contrast, only 64.3% of respondents who never requested leftovers expressed the same sentiment. Conversely, respondents who associated taking leftovers with poverty or found it acceptable to leave food uneaten were less likely to request leftovers themselves. For example, 15.0% of respondents who did not request leftovers agreed with the statement “It is acceptable to me to leave the food you cannot eat on your plate”, compared to only 2.1% of those who consistently requested leftovers. Similarly, 16.4% of those who did not request leftovers expressed indifference (“I do not care”) compared to only 2.4% of those who consistently requested leftovers.

These findings suggest that positive attitudes toward FW prevention, such as being glad that food will not go to waste, are strongly associated with proactive leftover-wrapping behaviours. Meanwhile, negative or indifferent attitudes are linked to a lower likelihood of requesting leftovers to be wrapped. Furthermore, no significant differences were observed between genders or age groups regarding the willingness to request leftovers. Overall, the findings show that leftover-related decisions are driven primarily by a mix of motivational factors (FW aversion, taste, convenience) and opportunity factors (restaurant practices, portion sizes).

4.4.2. Attitudes Toward Portion Size Reduction

The survey revealed diverse attitudes toward portion size reduction as a strategy to minimise FW. Approximately 41.2% of respondents prioritise portion sizes for meal enjoyment, while 41.8% do not, indicating a nearly balanced distribution of preferences. Moreover, 42.4% of respondents reported being able to immediately discern if a portion is too large, reflecting a high level of awareness regarding portion sizes. Conversely, a smaller segment (15.5%) admitted they are unable to detect excessive portion sizes upfront, suggesting a lack of initial awareness or evaluation. These findings highlight varying perspectives that set the stage for evaluating the acceptability of portion size reduction as an FW minimisation measure (

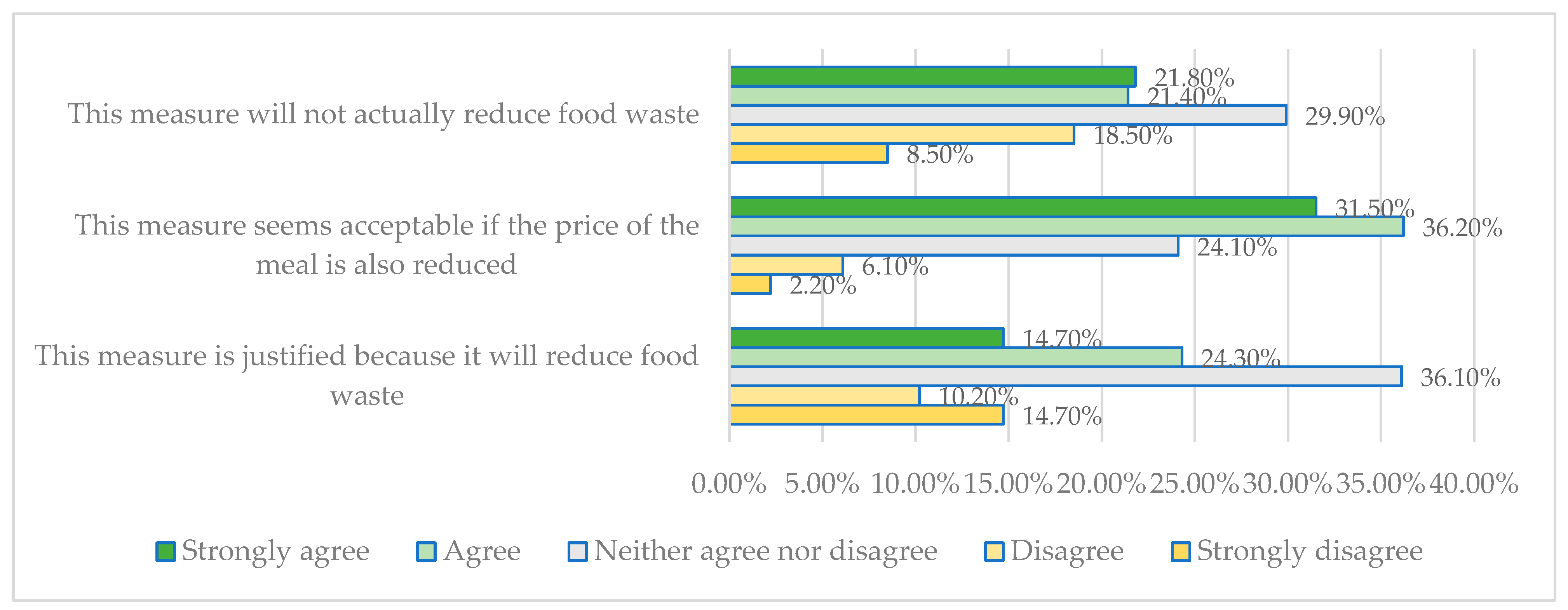

Figure 8). Respondents expressed mixed opinions on the justification and effectiveness of reducing portion sizes.

A combined 39% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “This measure is justified because it will reduce FW,” with 24.3% agreeing and 14.7% strongly agreeing. However, 24.9% disagreed or strongly disagreed with this proposition, demonstrating that a significant portion of the population questions its effectiveness. When asked whether the measure would actually reduce FW, 43.2% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “This measure will not actually reduce FW,” indicating scepticism about its efficacy. In contrast, 27% disagreed or strongly disagreed with the claim, suggesting confidence in the measure’s potential to reduce waste.

Looking more deeply into these results it becomes apparent that respondents who consider portion sizes important for meal enjoyment are less likely to agree that reducing portions is justified for reducing FW and vice versa. The results reveal a statistically significant association (p < 0.001). The strength of the association, measured by Phi = 0.639, indicates a strong positive relationship between these variables. Among those who strongly disagree that the measure is justified, 43.8% also strongly agree that portion sizes are important for their meal enjoyment. Conversely, among those who strongly agree that the measure is justified, only 18.0% strongly agree that portion sizes are important for enjoyment, highlighting an inverse relationship. Similarly, those who prioritise portion sizes for meal enjoyment tend to adopt a neutral or opposing stance on the justification of portion reduction. Of the respondents, 74.3% were uncertain (i.e., “neither agree nor disagree”) about the justification of this measure and also reported that portion size importance is “uncertain”. This pattern suggests that meal satisfaction derived from portion sizes is a key determinant in the perception of portion reduction measures.

The level of acceptance for portion size reduction appears to increase significantly when paired with a reduction in meal prices. A total of 67.7% of respondents found the proposal more acceptable when the cost of the meal was lowered, demonstrating a strong preference for balancing portion adjustments with economic value. However, 8.3% of participants still disagreed with the proposal even if prices were reduced, indicating resistance from a small segment of the population regardless of financial incentives.

4.4.3. Attitudes Toward Pre-Ordering

The concept of pre-ordering meals also emerged as a practical strategy to reduce FW and support sustainability efforts within the food services domain. In our study, respondents’ attitudes towards the acceptability of ordering meals in advance to minimise FW were explored among others. The results provide insights into the level of support and reservations among consumers regarding this approach.

We firstly asked about agreement with the following statement: “I would find it acceptable to order my meal at least 1 day before going to the restaurant if this would contribute to less FW”. Around 35.5% of respondents either disagree or completely disagree with this statement, indicating they have some reservations or doubts about the idea of ordering ahead. The majority, 43.5% of respondents, fall into the “I partly agree” category, indicating that they are open to the idea of ordering their meals in advance to reduce FW. However, they may have some conditions or reservations. Only a combined total of 21% of the participants either “totally agree” or “agree” with the idea of ordering meals in advance to reduce FW. A small percentage of respondents, 15%, agree with the concept, showing support for the idea of pre-ordering to reduce FW, viewing it as a positive step and are willing to make this change. However, only 6% of respondents are highly supportive of the idea, indicating a strong willingness to pre-order their meals to contribute to reducing FW.

To explore the circumstances under which consumers might be willing to pre-order their meals, the survey presented respondents with various scenarios (

Figure 9). A small price reduction, such as 10% cheaper than the usual price, garnered interest from 36.9% of respondents, indicating that while some consumers are motivated by modest discounts, the majority (63.1%) are not convinced by this offer alone. In contrast, a more substantial discount of 30% cheaper than the usual price proved to be a stronger motivator, with 52.5% of respondents indicating their willingness to pre-order under this condition. This demonstrates that larger price reductions can significantly enhance the appeal of pre-ordering meals, likely due to the perceived value of greater savings. The option to pre-order meals with a variety of different dishes available resulted in a nearly even split among respondents, with 50.7% willing and 49.3% unwilling to pre-order under this condition. This result implies that choice and variety on the menu are important to a substantial portion of customers, but they are not overwhelmingly preferred over the option to order on the spot. The strongest motivator for pre-ordering was the scenario where pre-ordering is made a requirement to reserve a table, with 69% of respondents expressing their willingness to pre-order under these terms. It appears that many people are willing to pre-order if it guarantees them a table at the restaurant. This may be due to the added convenience and assurance it provides in securing a dining spot.

These descriptive results, presented in

Section 4.4, reveal a complex picture of consumer food waste behaviour, highlighting that both external factors (e.g., portion sizes, food quality) and internal motivations (e.g., food waste aversion, upbringing) influence a leftover generation. The next section,

Section 4.5, extends this investigation by performing regression analysis to explore the key factors driving consumer behaviours outlined in

Section 4.4. Using the MOA framework, each behaviour is modelled to assess the role of socio-demographic variables, such as gender, age, and dining frequency, in shaping food waste reduction strategies.

4.5. Regression Analysis

This section delves deeper into the statistical analysis of how motivation, opportunity, and ability, in conjunction with socio-demographic factors, influence consumers’ willingness to adopt food waste reduction strategies. The results of three regression models are presented, each designed to examine Slovenian consumers’ behaviours concerning food waste reduction when dining out. The models explore three key behavioural aspects: (1) the willingness to take leftovers home, (2) the acceptance of portion size reduction, and (3) the acceptance of pre-ordering meals, all analysed through the lens of the MOA framework.

4.5.1. Overview of the Regression Models

In order to address the research questions formulated earlier and to apply the MOA framework, three separate regression models were estimated. Each model focuses on a specific food waste reduction behaviour and includes the MOA variables as well as socio-demographic controls (

Table 4).

Model 1—Leftover Decision

Objective: Explains consumers’ willingness to take leftovers home after eating at a restaurant.

Theoretical basis: Assumes that motivation, opportunity, and ability determine whether customers are likely to engage in this behaviour.

Model 2—Portion Size Reduction Acceptance

Objective: Explains consumer acceptance of smaller portion sizes as a food waste reduction strategy.

Theoretical basis: In addition to MOA variables, includes perceived importance of large portion sizes as a potential barrier.

Model 3—Pre-ordering Acceptance

Objective: Explains consumers’ acceptance of pre-ordering meals in advance to reduce FW, a less common but potentially effective strategy.

Theoretical basis: Tests the influence of MOA factors and demographics on acceptance of pre-ordering practices.

4.5.2. Results of Model 1: Willingness to Take Leftovers Home

The regression model examining consumers’ willingness to request leftover food to be wrapped (

Table 5) was statistically significant, F(6, 509) = 4.592,

p < 0.001, with an R

2 of 0.051 and an adjusted R

2 of 0.040, indicating a modest explanatory power. Among the predictors, Motivation emerged as the only significant variable (β = −0.197,

p < 0.001). Interestingly, the negative coefficient suggests that individuals with stronger motivation to reduce food waste may be more likely to adjust their food choices or portion expectations, thus reducing the need to request leftovers.

Other variables, including Opportunity, Ability, Gender, and Dining Frequency, were not significant predictors of this behaviour. Year of Birth showed a marginally significant positive effect (β = 0.086, p = 0.052), indicating a possible age-related trend, where older individuals may be slightly more inclined to request leftover food to be wrapped, though this effect was not statistically robust.

4.5.3. Results of Model 2: Acceptance of Portion Size Reduction

The regression model predicting acceptance of portion size reduction as a strategy to minimise FW (

Table 6) was statistically significant, F(7, 366) = 7.945,

p < 0.001, with an R

2 of 0.132 and an adjusted R

2 of 0.115. This indicates a moderate ability to explain the variance in consumer attitudes toward this measure.

The most influential predictor was the perceived importance of portion size for meal enjoyment, which had a strong and statistically significant negative effect (β = −0.287, p < 0.001). This suggests that consumers who place a high value on receiving larger portions are significantly less likely to support portion size reductions.

Additionally, Year of Birth was a significant positive predictor (β = 0.144, p = 0.004), indicating that older consumers are generally more open to portion size reduction compared to younger individuals. Other predictors—Motivation, Opportunity, Ability, Gender, and Dining Frequency—did not show significant effects in this model.

4.5.4. Results of Model 3: Acceptance of Pre-Ordering

The regression model exploring consumers’ acceptance of pre-ordering meals as an FW reduction strategy (

Table 7) was statistically significant, F(6, 509) = 5.440,

p < 0.001, with an R

2 of 0.060 and an adjusted R

2 of 0.049. While the explained variance is modest, the model revealed three significant predictors.

Motivation was positively associated with pre-ordering acceptance (β = 0.182, p < 0.001), indicating that individuals with stronger concern for food waste are more likely to support pre-ordering measures. Ability also had a positive effect (β = 0.093, p = 0.036), suggesting that consumers who are confident in their food planning and consumption habits are more open to pre-ordering.

In contrast, Opportunity had a significant negative influence (β = −0.138, p = 0.002). This finding suggests that when consumers perceive existing food waste reduction practices as sufficient, they may be less inclined to see pre-ordering as necessary or beneficial. Other variables—Gender, Year of Birth, and Dining Frequency—did not significantly predict acceptance of pre-ordering.

4.5.5. Comparative Summary of Regression Models

To synthesise the findings of the three regression models,

Table 8 provides a comparative overview of significant predictors identified in the study.

The comparative results highlight several important findings:

Motivation plays a complex role across behaviours. While it significantly reduces the likelihood of requesting leftovers to be wrapped (Model 1), it increases acceptance of pre-ordering meals to reduce food waste (Model 3). This suggests that highly motivated consumers may proactively avoid waste through portion control or planning, rather than relying on leftovers, and are more likely to support the measure of pre-ordering.

Perceived portion size importance was the strongest negative predictor in Model 2. Individuals who view large portions as essential to meal satisfaction are less supportive of portion size reductions, indicating a key attitudinal barrier to this strategy.

Ability to manage food waste was only a significant factor in Model 3. This implies that consumers’ confidence in handling food choices and quantities is particularly important when considering more structured interventions like pre-ordering.

Opportunity had a significant negative effect only in Model 3, suggesting that when consumers already perceive sufficient waste reduction options in restaurants, they may be less inclined to embrace additional strategies like pre-ordering.

Age (Year of Birth) showed a positive effect in Model 2 and a marginal effect in Model 1, indicating that older consumers tend to be more supportive of food waste reduction strategies, particularly portion control and leftover acceptance.

Gender and frequency of eating out did not significantly predict any of the three behaviours, implying these demographic factors may be less influential than psychological and attitudinal variables.

Overall, this shows that FW-related behaviour is multi-faceted, and the MOA components operate differently depending on the behaviour targeted.

5. Discussion

Efforts to address FW have become increasingly important in light of sustainability efforts such as the U.N. Sustainable Development Goals, and within the European Union, the EU Green Deal, Farm to Fork Strategy, and the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030, being a few examples. There is a growing social consciousness about the effects of food waste on the environment and the need to address it. Within the EU it is estimated that food waste accounts for at least 6% of its total emissions [

36] (p. 4). The food system plays a critical role in the battle to mitigate the effects of climate change. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimates that from “2010–2016 global food loss and waste equalled 8–10% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions” [

37] (p. 492). As consumer awareness of environmental issues grows, there is a growing interest in exploring attitudes toward innovative strategies to minimise FW.

This study offers new insights into the behavioural mechanisms of consumers underlying FW in the out-of-home sector, using the MOA framework as a theoretical lens. Rather than simply quantifying food waste, we examined key behavioural intentions linked to three specific consumer actions: taking leftovers home, accepting portion size reduction, and pre-ordering meals. The regression results show that these behaviours are influenced by distinct behavioural drivers, which has both theoretical and practical implications for food waste prevention strategies.

Our analysis shows that plate-level food waste is driven by a variety of factors, with the two most prominent being poor taste and food quality, and portion sizes that are too large. When meals fail to meet consumers’ expectations in terms of flavour or texture, they are more likely to be left uneaten. This aligns with the previous literature, which highlights how portion size norms reflect societal expectations around food abundance and consumption behaviour [

30,

31].

Respondents identified several personal motivations for finishing meals, including hunger, cultural upbringing (e.g., being taught not to waste food), and ethical or environmental concerns related to food waste. These findings underscore the interplay between personal values and social conditioning in shaping food-related decisions. Notably, social pressure played a relatively minor role, suggesting that internalised motivations may outweigh external influences when it comes to meal completion.

Attitudes toward reducing portion sizes for reducing FW were mixed among respondents. Our regression analysis confirmed that perceived importance of large portion sizes was the strongest negative predictor of willingness to accept portion reduction, suggesting this remains a major barrier to change. However, support for this measure is increased when it is combined with a reduction in meal prices, suggesting that economic incentives could sway opinions.

Interestingly, we observed that taking leftovers home after a meal was a relatively common practice among respondents. This behaviour was primarily motivated by ethical and environmental concerns, as well as personal satisfaction with the taste and quality of the meal. The practical benefits of consuming leftovers, such as the ease of having pre-prepared meals available for later use, also played a role, as did economic considerations, (e.g., saving money). However, external constraints, such as restaurant policies prohibiting or not offering leftover containers played a role in shaping respondents’ behaviour. While some restaurants provided wrapping (foil) or containers for the leftovers, others requested payment for the containers. Perhaps making it restaurant policy to automatically wrap any leftover food and then to give it to customers after their meal, might facilitate less food waste.

Usage of leftover food in the home environment, depends of course on food safety, how applicable it is to utilise the food, but the most prevalent motivation in the survey was if it was simply good food. It is possible, however, that within this domain a food-related social norm came into play—that of “suboptimal food/undesirable food quality”. This norm involves the acceptance or rejection of food based on its perceived quality, influencing decisions about consumption or disposal [

27,

28].

Support for pre-ordering meals to reduce food waste was more divided. While some individuals were receptive to the idea, a significant portion expressed reluctance, especially regarding the inconvenience of ordering meals in advance. Moreover, pre-ordering is also dependent on the type of food service being offered—such as a la carte or self-service (buffet). The benefit of having customers order in advance is that it facilitates more efficient meal planning and preparation. Effective planning and preparation ensure that the restaurant orders supply in a timely manner while preventing overstocking and reducing the likelihood of food expiring. Restaurants can avoid having excess ingredients, ensuring that items used are fresh, and reducing the likelihood of waste. Attitudes toward pre-ordering improved when coupled with incentives such as discounted prices or a wider variety of meal options. Notably, most respondents indicated that their attitudes toward pre-ordering would change if it guaranteed them a table in the restaurant, suggesting that convenience was a key factor in shaping their opinions. Thus, combining a substantial price discount, along with the convenience of knowing that a table will be automatically reserved, may help encourage pre-ordering for food institutions where this is possible (such as a la carte services), while also allowing for smaller portion sizes to be presented to customers.

From a theoretical standpoint, the study reinforces the value of the MOA framework in FW research. Motivation emerged as a consistent, though context-dependent, predictor across models. Notably, its negative association with taking leftovers suggests that highly motivated consumers may adopt proactive approaches to avoid waste—such as ordering appropriately or finishing meals—rather than relying on reactive behaviours like taking food home. Conversely, the positive link between motivation and pre-ordering acceptance supports the idea that pre-ordering may be perceived as a more intentional, planning-based strategy aligned with consumers’ ethical or environmental motivations. Ability, representing individuals’ confidence in managing food quantities and making responsible choices, was positively associated with acceptance of pre-ordering. This aligns with existing behavioural models that link self-efficacy to proactive decision-making. Meanwhile, Opportunity—conceptualised as perceived external support for waste-reducing behaviours—was only significant in the context of pre-ordering, and in a negative direction. This suggests that when consumers perceive that restaurants already provide ample opportunities to reduce waste, they may see pre-ordering as redundant.

These findings suggest that MOA components influence behaviours differently depending on the perceived structure, effort, and autonomy involved in the action, which contributes to a more nuanced understanding of this widely used theoretical model.

6. Concluding Remarks

Overall, by understanding consumer perspectives and preferences, food services can tailor their practices to align with sustainability goals while meeting customer needs and expectations. The findings suggest that portion size reductions could be implemented as a targeted FW mitigation strategy, taking into account individual preferences and attitudes toward pricing fairness. For instance, flexible pricing models and customisable portion sizes could address concerns about perceived value, increasing the likelihood of acceptance among consumers. To maximise impact, food services should not only have different portion options (small, regular, large), but also communicate the environmental and health benefits of smaller portions directly on menus and through staff interaction. From a policy perspective, public institutions and food sector stakeholders should consider integrating flexible portioning standards into public procurement guidelines, also in schools, hospitals, and public catering services. Policy can also encourage food services to adopt these measures through tax incentives or subsidies, especially for those offering variable portion sizes as part of their sustainability strategy.

Additionally, pre-ordering policies hold promise as a strategy for reducing FW. The results indicate that larger discounts and guaranteed table reservations are more attractive to consumers and can serve as a strong motivator for pre-ordering. While menu variety appeals to a significant portion of respondents, it is not a universally decisive factor. Food services can, therefore, benefit from implementing pre-order systems where diners commit to a meal in advance in exchange for a discount or added convenience. This not only improves inventory planning and reduces surplus but also enhances the dining experience through reduced waiting times and more personalised service. To support such innovations, public–private partnerships could invest in the development of digital platforms or tools that enable easy pre-ordering, especially in a la carte settings or urban catering environments.

Another important area is the handling of the leftovers. While many diners are open to taking uneaten food home, the practice is still underutilised due to social stigma, lack of packaging, or restrictive restaurant policies. To address this, food service providers should adopt a policy of automatically offering to pack leftovers, using environmentally friendly and safe packaging. This positions the restaurant as environmentally responsible and contributes to waste reduction without additional complexity.

To ensure long-term impact, these measures should be further supported at the policy level. National sustainability guidelines for the food service sector could incorporate standardised recommendations for leftover management, encouraging restaurants to proactively offer to package and normalise taking food home. Additionally, food establishments should be encouraged to track food waste regularly, identifying which dishes tend to result in higher plate waste and adjusting menu composition accordingly. Moreover, staff training programs should also integrate modules on food waste prevention, portion control, and sustainable customer engagement to build awareness at the operational level. Education policies for hospitality professionals can embed these principles as part of core curricula, ensuring long-term adoption of sustainable practices across the sector.

In conclusion, the findings highlight the multifaceted nature of consumer behaviours and attitudes toward FW in food service establishments. Effective strategies to minimise FW must balance ethical, economic, and convenience-driven considerations, while being rooted in both individual action and structural support. By addressing logistical barriers, offering financial incentives, and emphasising the importance of sustainability, food service providers can play a pivotal role in reducing FW and advancing sustainability goals.

7. Limitations and Future Studies

While this study addresses a significant research gap and contributes to the current literature on FW and consumer behaviour, it is not without limitations. First, the study relied on a single data collection method, an online survey administered via JotForm, which may limit the diversity and depth of the collected data. To further understand consumer attitudes and behaviours, future research should use a mixed-methods approach, such as combining surveys with qualitative techniques like focus groups or interviews. Second, more information was gathered via the questionnaire than was included in this paper. Additional data analysis could yield insightful information on other viewpoints, such as variations by demographic factors or contextual influences. Third, only Slovenian participants made up the study sample, which may restrict the generalisability of the findings to other cultural and geographical contexts. Cultural factors significantly influence dining behaviours and attitudes toward FW, as highlighted by Pelau et al. (2020) [

38]. To address this limitation, future research should examine similar issues in other cultural and national contexts to explore cross-cultural differences and enhance the global applicability of findings. Lastly, the study relied on self-reported data rather than direct measurements of real FW behaviour, which may introduce biases such as social desirability. Future research could validate self-reported findings using experimental or observational methodologies.