Abstract

Within the modern perspective of globalization, digitalization may be perceived as a key driver of technological development, a factor strongly affecting economic efficiency and the growth of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). However, this assumption still requires deeper empirical confirmation in developing nations whose economies depend on oil revenues. This paper investigates the causal and cointegration relationship between socioeconomic globalization, digitalization, and its impact on economic growth, using the kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) as a specific case of global economic transformation between 1990 and 2022. Using the Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) model with various estimation methods, including Ordinary Least Squares (OLS), Fully Modified Ordinary Least Squares (FMOLS), Dynamic Ordinary Least Squares (DOLS), and Canonical Cointegration Regression (CCR), we identified the most statistically significant factors contributing to economic growth. Our findings indicate that globalization has a negative and significant effect on GDP per capita at the 1 percent significance level. On the other hand, the results suggest that digitalization significantly contributes to economic growth in the short and long run. From these findings, this paper provides some key policy recommendations for improving the economic outlook of Saudi Arabia and other developing countries.

1. Introduction

In the modern globalized context, policymakers in both developing and developed industrial countries face many daunting challenges in terms of sustainable development with a particular focus on the multi-dimensional challenges of globalization of environmental, financial, technical, economic, and social dimensions within the global international system. In this context, this study aims to clarify the requirements of digital technology, digitization, or digital transformation, in its general sense, as addressed by many researchers, and its important role in achieving economic and social equality, thus enabling growth and sustainable development.

In this regard, Dąbrowska et al. (2022) [1] define digital transformation as “a socioeconomic change across individuals, organizations, ecosystems, and societies that are shaped by the adoption and utilization of digital technologies”.

While digitization is increasingly relevant, the economic literature has so far not been able to show how digitization actually aids in harnessing both economic and social globalization in the pursuit of developing nations toward accelerating their economic growth. This research, therefore, seeks to examine the impact of economic and social globalization on economic growth, linking such to the role that digitization plays in that regard. The present paper, based on empirical research data from the Saudi economy—a good representative example of a developing country that has passed significant structural changes and accelerated its economic and social growth during recent years—seeks to explore causality and cointegration among socioeconomic globalization, digitalization, and their joint impact on economic growth. Evidence will be derived from Saudi Arabia between 1990 and 2022.

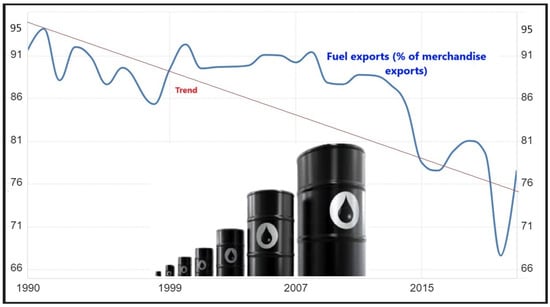

Saudi Arabia is endowed with abundant primary energy resources, including crude oil, coal, and natural gas. Notably, petroleum products account for approximately 90 percent of the country’s exports, with the oil industry contributing around 45 percent to the gross domestic product (GDP), (Mahalik et al., 2017) [2]. The industrial and manufacturing sectors collectively represent 52 percent of Saudi Arabia’s GDP. As depicted in Figure 1, the proportion of crude oil in total Saudi oil exports has decreased from 95 percent in 1990 to roughly 75 percent in 2022, highlighting a trend toward diversification that has become increasingly apparent over the past decade.

Figure 1.

A decline of fuel exports as a % of merchandise exports in Saudi Arabia (1990–2022). Source: Author’s elaboration of data from World Development Indicators (WDI), World Bank Database.

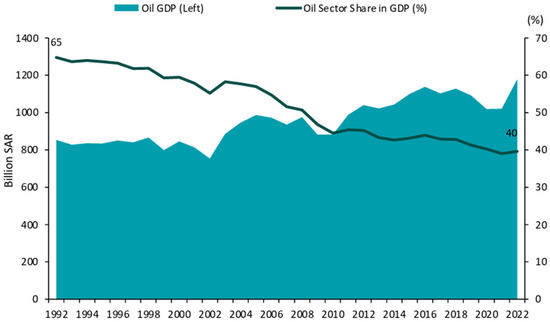

Figure 2 gives the trend of the oil sector’s contribution towards the Saudi economy: the blue area represents oil GDP while the black line refers to the share of oil sectors in overall GDP, presented as a percentage.

Figure 2.

The decline in the contribution of the oil sector to the Saudi economy. Source: The General Authority for Statistics, and estimates of the Ministry of Economy and Planning. Annual Report 2022.

The share of the oil sector in GDP has fallen consistently from above 65% in 1992 to around 40% in 2022, a reflection of sustained efforts at economic diversification. Despite fluctuations in oil GDP—its sharp contraction during the 2008–2009 global financial crisis and again during the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020—signs of recovery are there, but no significant long-term growth.

This declining share of oil in GDP indicates an expansion of non-oil sectors, which aligns with Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 strategy aimed at reducing dependence on oil revenues. Interestingly, in 2022, oil GDP experienced a sharp increase, likely due to rising oil prices and production levels; however, its overall share in GDP continued to decline, underscoring the country’s shift toward a more diversified economy.

Despite its resource wealth, Saudi Arabia has encountered economic challenges stemming from persistent declines in oil prices in recent decades, resulting in diminished oil revenues. To alleviate its dependency on the oil sector, the government has initiated strategies aimed at diversifying the economy, recognizing the essential role of the financial sector in fostering economic growth. These measures encompass the promotion of the banking sector, the enhancement of financial markets, and the development of the insurance sector. In alignment with this economic diversification strategy, the government has introduced Vision 2030, underscoring the significance of enhanced globalization. This global engagement not only facilitates financial development but also nurtures sustainable economic growth by bolstering the quality of the country’s economic development (Shahbaz et al., 2019) [3].

As a widespread phenomenon, globalization exerts a profound influence on global socioeconomic and political factors, facilitating the integration of economies through trade and foreign direct investment (FDI). However, the process of globalization is not devoid of challenges. In pursuit of globalization, multinational corporations may compromise environmental standards during the establishment of factories in host countries (Shahbaz et al., 2018) [4]. The structural changes in industries necessitated by globalization to meet international demand often require additional resources, posing risks of environmental degradation. Moreover, globalization, facilitated by trade liberalization, promotes the free exchange of goods among nations, leading to increased production and consumption of goods and energy (Shahbaz et al., 2015) [5].

The influx of foreign firms investing in host countries represents another dimension of globalization. Recent technological advancements and societal trends favoring digitalization have engendered significant global transformations. This paradigm shift necessitates substantial adjustments. The global economy has experienced considerable changes within the socioeconomic–educational system, especially in higher education. These transformations include alterations in educational standards, quality, decentralization, and the emergence of virtual and independent learning (Mohamed Hashim et al., 2022) [6]. The strategic focus has shifted toward students rather than being exclusively on technology and learning opportunities. The integration of digital devices and transformations has positively influenced the learning environment, yielding promising outcomes over time (Hanelt et al., 2021) [7].

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a comprehensive literature background. Section 3 presents the empirical studies and methodology adopted in this study. Section 4 highlights the test specification, proposed method, results discussion, and robustness of my method. Finally, Section 5 provides concluding remarks and suggestions for future research.

2. Literature Background

According to the Solow model (1956) [8], continuous improvement of living standards can only be achieved by technological progress. New growth theories represented by Sala-i-Martin and Barro (1995) [9] also underlined the contribution of technological progress in explaining economic growth. These new growth theories were developed on the basis of internalization of technological progress from the Solow growth model. Unlike the Solow model, which considered technology to be exogenous, emerging new growth models make an attempt at endogenizing technical change. Further, rates of modern technological change are supposed to impact economic growth, as well as life span, social stage, health and mortality, the extent of poverty, and literary rates, according to Grossman and Helpman (1995) [10]. For example, researchers such as Oliner and Sichel 1994 [11] claim that new technologies and the quality enhancement of existing goods are impulse factors of growth. The authors use the neoclassical framework and add information technology to the growth model. They prove that the growth rate of output is dependent not only on the stock of computing equipment but also on other factors such as capital, labor, and multifactor productivity. The utmost idea of digitization is built on utilizing ICT facilities for accessing materials globally for the betterment of society. In this present age, digitization is considered very key to environmental health and safety. Several organizations are busy digitizing their materials, as they can be used for educational purposes throughout a lifetime. In addition, the digitization of collections enhances institutional prestige by enabling users around the world to learn about the existence of institutional collections and access them remotely.

The contribution of ICT to globalization in the past three decades has attracted a great deal of interest from economists and researchers. Most have focused on the assessment of the impacts of globalization and the diffusion of ICT on economic growth in developed and developing economies. According to Arendt (2015) [12], most literature reviewed identified globalization and ICT as playing a vital role in bringing about economic prosperity in both contexts. The influences of globalization in the process of economic development are multi-dimensional for both developed and developing countries and have both positive and sometimes negative effects. In fact, gains from globalization are not evenly shared among countries, sectors, and individuals within the same country. This dual effect justifies the wide range of theoretical and empirical studies investigating globalization and its socioeconomic impacts. Several studies confirm that globalization plays a crucial role in the economy as a whole (Bhagwati, 2004 [13]; Grossman and Helpman, 1995 [10]; Crafts, 2004 [14]; Stiglitz, 2002, 2006 [15,16]; Dreher, 2006 [17]; Rahman, 2020 [18]; Shahbaz et al., 2019 [3], among others). Bhagwati (2004) [13], one of the world’s foremost economists, believes that globalization, if properly regulated, is on the whole one of the most powerful drivers of social benefit worldwide. His book, In Defense of Globalization, dispels doubts about aspects relating to the social impact due to economic globalization. The topics range from the implications for women’s rights and equality, poverty in the under-developed world, democracy, and whether dominant and/or indigenous culture can be sustained, to concern for the environment. As a response to accusations of globalization promoting cultural dominance, he states that internationalization is part of the solution, not part of the problem. However, Stiglitz (2002) [15] has argued that the impact of globalization is determined by a country’s readiness to exploit opportunities afforded by globalization for economic development. Bhagwati (2004) [13] goes even further to state that, under the right circumstances, globalization is indeed the most potent force for social good in the world today. He shows that globalization often solves many problems in poor countries by quickly reducing child labor and increasing literacy as prosperous parents send their children to school instead of to work. Furthermore, globalization advances women’s rights worldwide and proves that economic growth does not necessarily lead to more pollution if combined with appropriate environmental measures [13].

Stiglitz 2006 [16] demonstrates in his work, Making Globalization Work, how globalization goes beyond political interests as well as the sensitivity of one’s moral judgment to bring fairness and sustainability in the world economy. He has underlined that to realize all these, the real work required by all countries is to correctly understand and use globalization. Indeed, a number of influential studies claim that globalization can strongly spur economic growth if a threshold level of institutional quality, such as international openness, equal access to information in financial markets, and a favorable composition of capital inflows, is present in countries importing capital (Kose et al., 2009 [19]; Stiglitz, 2002 [15]; Wei, 2006 [20]; Daude and Stein, 2007 [21]; Uusitalo and Lavikka, 2021 [22]). The fact that these propositions have not been empirically validated by the seminal works mentioned above calls for an investigation into the role of QoG and FDI as significant determining factors in the impact of globalization on economic growth.

Among the international fraternity of economists, it is a well-accepted fact that increasing international trade leads to faster economic growth (Crafts, 2004 [14]; Dollar and Kraay, 2004 [23]). The underlying reasoning for this, however, depends on the variant of growth theory being considered. In particular, neoclassical growth theory maintains that openness enables a superior allocation of resources and thus facilitates growth. However, endogenous growth theory supports the view that openness may elicit growth in a number of ways, which include the process of technology diffusion, learning by doing, as well as through the exploitation of scale economies. Shahbaz et al. (2019) [3] confirm that the concept of globalization exists when economies are highly integrated and share social norms and political ideologies. Further, Dreher (2006) [17] maintains that globalization opens up economies and creates an avenue for growth and prosperity, hence the possible impact on national economic growth and development.

Hirst and Thompson (1996) [24] critically analyze globalization and its effects. They look at the economic, political, and social dimensions of globalization and question the consequences thereof on governance and the nation-state. The authors insist that globalization is not an overwhelming, inexorable force but a complex and contested process. They question the prevailing wisdom that globalization brings about the withering away of the nation-state and reiterate that the nation-state is still a powerful player in global affairs. Hirst and Thompson (1996) [24] argue that globalization should be conceptualized as a set of interrelated processes interacting with political and social structures at a number of levels. They emphasize the role of economic globalization in shaping the international economy, discussing the liberalization of trade and finance, the rise of multinational corporations, and the growth of global financial markets. They also talk about how technological changes, such as in ICT, impact the process of global economic integration. Hirst and Thompson (1996) [24] also voice their concerns over the process of globalization and its consequence: that it can lead to inequality within and between nations. They emphasize that global economic integration may intensify social and economic inequality, especially in developing countries. They show concern about democratic governance being eroded and power being concentrated in the hands of non-state actors like multinational corporations and international financial institutions.

What is more, the authors question the concept of the world without borders, standing up for the relevance of borders and national institutions. They contend that the nation-state remains a significant form of political authority and, as such, democratic governance and accountability must remain firmly embedded within the nation-state. Hirst and Thompson (1996) [24] support new forms of global governance to counter the problems caused by globalization; they again emphasize that democratic accountability, transparency, and social regulation will shape global economic processes. What they want is international institutions capable of acting effectively in global problems but, simultaneously, respectful of democratic principles. Overall, their view of globalization challenges the hegemonic discourses of an unstoppable and omnipresent process, stressing the complex and contradictory nature of globalization and asking for a differentiated approach to its implications for governance and societal well-being.

In fact, an increase in economic globalization may not result in economic development and growth for those countries that have limited economic opportunities. Such countries may not be able to benefit from globalization because of a lack of preconditions. Most researchers underline structural and socioeconomic factors that influence the relationship between globalization and economic development, especially economic growth. The general perception, therefore, of globalization and growth is that there is a positive effect provided there is enough quality in the structural and socioeconomic indicators across nations. Growth performances vary between nations due to the role of policy complementarities, which is crucial in enhancing economic growth. Policy integrations are required along with trade openness for boosts in economic growth to be effective, and hence both are a pre-requisite for such growth. In fact, financial liberalization also displays the higher sensitivity of output with regard to institutional quality improvement shown by Omoke and Opuala-Charles (2021) [25]. On the contrary, complementarities in country policy create a limit for designing growth strategies in countries resistant to reform and under unfavorable initial conditions, as was shown by Calderon and Fuentes (2006) [26]. On this note, Chang et al. (2013) [27] established that banking, governance, labor market, infrastructure, and trade reforms determine the nexus of globalization and growth nexus in developing countries. On a related thought, Gu and Dong (2011) [28] established that financial development and financial integration are the pre-conditions for financial globalization to be effective. The authors established that in the absence of any changes in the financial system, globalization results in volatile growth in countries. The foundational study by Samimi and Jenatabadi (2014) [29] suggests that economic globalization and a country’s structural characteristics are interdependent and complementary. In alignment with this perspective, Sirgy et al. (2004) [30] delve into the impact of globalization on life expectancy in developing countries, highlighting the pronounced challenges these nations face, particularly regarding health outcomes. Although a limited number of studies investigate the impact of globalization on human health (e.g., Sirgy et al. (2004) [30]), most of them highlight different ways in which globalization can affect middle-income countries (Shahbaz et al., 2018 [4]; (Audretsch et al., 2014 [31]). Evidence also shows that structural shifts are more favorable to growth in countries with more adaptable labor markets.

The World Bank, International Monetary Fund, World Trade Organization, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development have been the most important international institutions to widely advocate globalization, underlining its benefits to economic growth, global trade, and sustainable development for all countries.

The World Bank views globalization as a potent force for economic growth, poverty reduction, and rising living standards worldwide. It underlines the benefits that come with greater international trade, investment, and economic integration reflected in various publications, including the “World Development Report” by the World Bank (2020) [32], focusing on the role of globalization in promoting economic development and inclusive growth strategies.

Likewise, the IMF believes in globalization and promotes the contributions of globalization to world economic growth and development. The IMF works for policies that promote international trade, investment, and financial integration for stability in the economy. Various reports it publishes, such as the “World Economic Outlook” (IMF, 2021) [33], often discuss benefits from trade liberalization and macroeconomic stability in a globalized framework.

The approach by UNCTAD is underlined by the development dimension of globalization, inclusive and sustainable growth, with a particular emphasis on developing nations. Various reports, like their “Trade and Development Report” [34], present different pros and cons of globalization. They are committed to coherence in policies so that all might benefit and encompass fair trade and technology transfer, among other areas.

The WTO promotes the principles of open trade, market access, and nondiscrimination, hence pressing for the reduction of trade obstacles to make world trade easier. According to the WTO’s annual “World Trade Report” [35], it debates trade trends, the effect of trade policy, and the value of rules-based trade governance through challenges such as protectionism and the requirement to act globally.

Finally, the OECD views globalization as a driver of economic development, innovation, and productivity growth. It attaches great importance to open markets and international cooperation for the integration of economies. For example, various reports, such as “OECD Economic Outlook” [36], analyze the implications of globalization in many policy areas, including trade and the environment. They also discuss issues like income inequality and the need for inclusive growth policies.

Globalization, as stated by Robertson in 1992 [37], is more than the diffusion of global economic factors but a multifaceted process comprising economic, political, cultural, and social elements. He identifies technology as an enhancer of globalization. Indeed, he cites the improvements in transport and communication technologies. According to Robertson (2000) [37], globalization connotes the process of developing a consciousness of global connectivity and interdependence. Baldwin (2018) [38] assigns an extensive information technology role to globalization and discusses the implications for the world’s economy. As put by Baldwin (2016) [39], this phase of globalization—the second unbundling—has been quite unlike earlier phases: driven by advances in ICT and characterized by a fragmentation of service activities across borders. He also mentions labor market polarization and increasing income inequality as possible consequences. In summary, Baldwin 2016 [39] positions information technology as a driver of globalization, which rebuilds economic relationships. The relationship between digitalization and globalization is thus very complex and multifaceted, including both positive and negative impacts. While digitalization increases global connectedness and economic opportunities, it also leads to increased inequality and causes problems of governance. In the digitally connected global economy, Manyika et al. (2016) [40] discussed how the complexities of globalization have shifted to indicate that the network of global economic connections is growing in complexity, breadth, and depth, as well as the growing cross-border data flows that now bind the global economy with the same dependability as the traditional movement of manufactured goods.

Globalization and digitization are irresistible, interrelated processes reshaping the modern world. While globalization involves growing interconnectivity of economies, societies, and cultures across borders, digitization transforms information and processes into digital formats, making them interact faster and more extensively. Together, the two phenomena are mutually reinforcing. Digital technologies such as AI, cloud computing, and blockchain not only facilitate global trade and remote work but also enable companies of any size to participate in global markets. According to the World Economic Forum (2023) [41], digitization fuels globalization by enabling real-time communication, borderless information flow, and efficient global collaboration. On the other hand, globalization is also accelerating the advancement of digital technologies, as global competition drives digital innovation and investment in digital infrastructure, states the OECD (2022) [42]. While the enormous potential of such trends to transform industries and cultural exchange cannot be exaggerated, the challenge of the digital divide has to be addressed first so that no one will be left behind to participate in this interconnected world. Hart, J. (2010) [43] critically discusses arguments about how globalization is linked with digitalization. Sabbagh et al. (2012) [44] argue that digitization has the potential for dramatic economic, social, and political improvements.

Digitalization has significantly influenced Saudi Arabia’s socioeconomic landscape, driving economic growth, enhancing employment opportunities, and improving transparency (Neffati and Gouidar, 2019 [45]; Neffati and Jbir,2024 [46]). The education sector, in particular, has experienced significant advancements, with digital tools revolutionizing learning behaviors and improving accessibility. Moreover, the Vision 2030 initiative highlights the strategic importance of digitalization in diversifying Saudi Arabia’s economy, reducing oil dependency, and fostering innovation (Al-Sahli and Bardesi, 2024 [47]; Havrlant and Abdulelah, 2021 [48]). However, this relationship between digitalization and globalization also presents challenges. While digitalization promotes connectivity and economic opportunities, it raises concerns about inequality, data privacy, security, and governance. Different levels of digital access and literacy can make socioeconomic differences worse. To close these gaps and make sure everyone has an equal chance to participate in the digital economy, policies are needed (Khan, 2019 [49]; Hilbert,2016 [50] and Ragnedda and Muschert, 2013 [51]).

Research Gap

The relationship between digitalization and globalization is complex and multifaceted, with associated opportunities and challenges. Countries that manage to integrate digital technologies effectively can reap the benefits of globalization while minimizing its negative impacts, as demonstrated by the Saudi Arabian experience in leveraging digitalization for sustainable growth and development.

In brief, the Solow model of 1956 [8] became the starting point for theories of endogenous economic growth; it emphasized that the leading role in economic growth belongs to technological progress, and digitalization and information and communication technologies make great changes in social and economic aspects. Globalization is a phenomenon with complex, ambiguous effects—some of them positive and others negative—on economic development, which are spread very unevenly among regions and countries of the world.

The relationship between globalization and economic growth is complex, influenced by many factors, such as the quality of institutions, governmental structures, and foreign direct investment. Furthermore, there are diverse viewpoints on how globalization affects nation states and global governance, reflecting the multifaceted nature of this global phenomenon and its long-term consequences.

In the light of previous studies, we conclude that there are many areas that require further research, including the lack of empirical studies proving the validity of theoretical proposals on the roles of quality governance and FDI in shaping the impact of globalization on economic growth, especially in developing countries or specific industries. Perhaps the Saudi economy, which has undergone significant and accelerated transformations after the country’s accession to the World Trade Organization in 2005, is one of the examples worth studying. In addition, there is a need for further exploration of the long-term effects of digitization technology on economic growth, social structures and environmental sustainability. In addition, while the importance of digitization is being discussed, there is a need to further explore the long-term effects of digital transformations on economic growth, social structures, and environmental sustainability.

According to the theoretical and empirical review analysis, two main hypotheses will be verified:

Hypothesis 1.

Globalization has a positive impact on economic growth in the Saudi economy.

Hypothesis 2.

Digitalization has a positive effect on economic growth in the Saudi economy.

3. Empirical Studies and Methodology

The empirical studies have also been able to establish both the short-term and the long-term dynamic relationships among the study variables by applying the ARDL model. In various disciplines, the ARDL model has been applied in the investigation of the long-term relationships among variables. For example, Pesaran, Shin, and Smith (2001) [52] used the ARDL methodology to study the long-term relationship between inflation and money growth in the United States, something quite critical from a domestic perspective, where light was shed on the stability in this long-term relationship. Shahbaz et al. (2018) [4] utilized the ARDL approach to investigate the long-term effect of financial development on stock market performance in emerging economies and found that there is a positive and significant long-term relationship between the constructs. Further, Banday and Aneja (2019) [53], using the ARDL model, have also examined the long-term dynamics of energy consumption (EC) and economic growth as proxied by the GDP–CO2 emissions nexus in G7 countries. Their findings explained the long-term inter-relationships among the variables in detail. Furthermore, Shaari et al. (2023) [54] applied the ARDL model to analyze the long-term impact of FDI on trade in ASEAN countries and found positive and significant long-term causality from FDI to trade in the region. These studies further indicate the diverse usages of the ARDL model in empirical analysis.

On the other hand, the ARDL model is equally useful in studying the short-term dynamics of the variables. For instance, Kandil and Mirzaie (2021) [55] applied the ARDL framework to investigate the short-term effect of monetary policy on output for some Middle Eastern and North African countries. They emphasize how changes in interest rates and money supply influence fluctuations in output on a short-term basis. In a similar way, Bahmani-Oskooee and Ratha in 2007 [56] explored the short-term causal relationships of exchange rate volatility in trade flows in the United States and Canada. Their findings reflected how changes in exchange rates can affect the dynamics of trade flows in the short term. Chowdhury and Mavrotas (2006) [57] estimated the impact of fiscal policy on short-term economic growth for developing economies using an ARDL model. These authors considered the impact of government spending, taxation, and public debt on short-term growth patterns. Collectively, these examples illustrate the flexibility of the ARDL model in investigating short-term relationships across a wide range of subject areas.

From the above studies, this analysis relies on the ARDL model because there exist time series that are integrated with a different order. In fact, using the VAR model requires all series to be integrated in order 1, which is not the case with our series. The ARDL model developed by Pesaran and Shin (1998) [58] and further improved by Pesaran, Shin, and Smith (2001) [52], is particularly useful because it allows the inclusion of regression models with different integration orders, i.e., series I(0) and I(1). Moreover, it effectively captures both the short-term and long-term dynamic relationships among the study variables through the bounds cointegration test, hence enhancing the precision of the forecasts and informing government policy decisions. Therefore, this model fits perfectly with our hypotheses.

Prior to estimating the ARDL model equation through the OLS technique, we have to conduct the bounds cointegration test. Based on the findings, if our variables are cointegrated, we will extend our model by incorporating the long-run dynamic relationship through the CECM. In the event that the variables are not integrated, we would just specify the ARDL model. The general ARDL (p, q) model is given as follows:

is a vector, and the variables contained in the matrix ()′ may be integrated of order 0, I(0), or integrated of order 1, I(1).

γ is the constant; i = 1, …, k is the number of variables in the model.

δ and β are the coefficients of the variables.

p, q are the optimal orders of lags for the dependent and independent variables, respectively.

is the vector of error terms, also referred to as innovation or shocks.

3.1. The Empirical Model

To establish the right form of empirical model, we started with the traditional Cobb–Douglass production model, which uses only capital stock (K) and labor (L) to describe economic growth (Y), as follows:

We suppose the constant return to scale: , and we apply the logarithm,

We suppose that , production per capita, and , capital intensity.

So,

We apply log, then we have

The most popular metric of growth is production per capita (expressed as the ratio between the quantity produced and the number of workers required for its production, i.e., the term Y/L), which rises when capital intensity rises, as measured by an increase in the K/L ratio.

If we introduce the variables according to the object of our study, especially globalization variables (GI) and digital economic variable (DI), to Equation (1) and replace Yt by real gross domestic product per capita (GDPC), we obtain the general form of the estimated equation, as follows:

3.2. Variables and Database Sources

In this paper, we investigate the relationship between socioeconomic globalization, digitalization and economic growth. We validate this relationship using Equation (5) in the case of Saudi Arabia. The time series data used spans the period 1990 to 2022. Table 1 below provides a summary of the definitions for each variable, and the sources from which they were extracted.

Table 1.

Variable definitions and data sources.

Our study focusses on the KOF Globalization Index which measures the economic, social and political dimensions of globalization (Dreher (2006) [17]; Potrafke,2015 [60]). We use only the economic globalization index (EcGI) and social globalization index (SoGI) as calculated for all countries of the world. For Digitalization index (DI), we use as a proxy the Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) which is calculated referring to the study of Olczyk and Kuc-Czarnecka (2022) [61]. This index was chosen as a suitable variable that characterizes the development level of the digital economy. Olczyk and Kuc-Czarnecka (2022) [61] verify that DESI sub-indicators can be used to analyze the country’s digital transformation (Hilbert, 2016) [50].

In the light of the above discussion, the relationship between economic growth (GDPC), socioeconomic globalization and digitalization will be studied as shown in the following Equation (6):

GDPC; Gross Domestic Product per Capita

; Capital Intensity

; Globalization index

; Social Globalization Index

; Economic Globalization index

; Digital Economy and Society Index

; Error terms

In order to use and analyze our time series, we will first check their stationarity over time, which is a crucial step in the study of time series.

3.3. Specification Tests

3.3.1. Stationarity Test

A time series is considered stationary when all its marginal and joint distributions do not change over time, meaning it does not contain a unit root. Let us consider the following equation:

With : error term (i.i.d)

This series is considered stationary if ρ < 1. The null hypothesis and the alternative hypothesis for each of the series will be: H0: ρ = 1: the series contains a unit root. Ha: ρ < 1: the series does not contain any unit root. Several stationarity tests, such as the Phillips–Perron (PP) test, the Kwiatkowski, Phillips, Schmidt, and Shin (KPSS) test, and the Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test, can help us address these hypotheses. However, we will proceed with the Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test in Eviews (https://www.eviews.com/home.html).

Based on the estimation of unit root test (Table 2), all the studied variables are purely stationary into the first difference, or integrated at I(1). According to the result, we can perform the cointegration test and ARDL model to estimate the short- and long-term relationship. The ARDL model combines endogenous and exogenous variables.

Table 2.

Unit Root Tests (ADF).

As a necessary yet not sufficient condition, the ADF and PP tests are employed to identify unit root conditions. The results, presented in Table 2, indicate that all series exhibit non stationarity at the levels, (p-value > 0.05) but become stationary at first differences (I(1)) at a significance level of 0.05. Furthermore, the PP test results confirm that all selected variables can be classified under the I(1) process.

Building on the outcomes from Table 1, the next step involves proposing the Johansen rank with trace and maximum Eigenvalue test statistics to detect (Johansen, 1991) [62].

3.3.2. Cointegration Test

The strong co-integration phenomenon was developed by Engle and Granger in 1987 [63]. Indeed, a regression derived from non-stationary time series can yield misleading correlation results, commonly referred to as “spurious correlation”. Cointegration analysis allows us to distinguish regressions that have a plausible causal relationship.

Two non-stationary variables are said to be cointegrated if there is a long-term dynamic relationship between them. That is, if two variables are cointegrated of order I(1), their linear combination becomes I(0). Thus, even if they diverge in the short term, they eventually converge in the long term. One limitation of the Engle–Granger 1987 cointegration test is that it only applies to series integrated of order 1. Therefore, Pesaran and Shin (1998) [58] and Pesaran, Shin and Smith (2001) [52] developed the bounds cointegration test, which allows studying the short-term and long-term dynamic relationship of two variables integrated with different orders, for example, I(0) and I(1). In their respective studies, Mbarek et al. (2017, 2018) [64,65], Saidi and Mbarek (2016) [66], and Ngoma and Yang (2024) [67] utilize cointegration estimation to explore the dynamic relationships between key economic variables over the short and long term. These estimations are essential in detecting long-term equilibrium relationships amidst short-term fluctuations, allowing the authors to assess how different economic factors co-move and influence each other over time. For instance, Mbarek et al. (2017) [64] focus on the relationship between energy consumption and economic growth, while Saidi and Mbarek (2016) [66] investigate environmental quality’s impact on economic development.

Cointegration assumptions:

Ho: absence of cointegration relationship among the study variables.

Ha: There is one or more cointegration relationships among the study variables.

The co-integration results, as shown in Table 3, reveal the presence of two co-integration equations at the 0.05 significance level. This implies a significant long-term relationship between socioeconomic globalization, digitalization, and economic growth in Saudi Arabia. In the following phase, we will use the ARDL model, with support from FMOLS and DOLS, to investigate both the long- and short-term causal links between all variables (dependent and independent). While theoretically, running a VECM is possible when variables are co-integrated in the first-level to determine causality between them, it is not sufficient.

Table 3.

Johanson Cointegration Test.

4. Estimated Models

The estimated results of the OLS, FMOLS, DOLS, and CCR models are presented and reported in Table 4 by estimating the following models:

Table 4.

OLS, FMOLS, DOLS and CCR estimation methods.

All variables were defined in Section 3.2.

4.1. Estimation Results

The output of the OLS (Ordinary Least Squares), FMOLS (Fully Modified Least Squares), DOLS (Dynamic Least Squares), and CCR (Canonical Cointegration Regression) estimation methods is summarized in Table 4, which indicates that capital intensity has a strong and statistically significant impact on GDP per capita, with significance at the 1 percent level. This finding is always verified across the different models. Turning to globalization index, it has a negative and statistically significant effect at the 1 percent significance level on LNGDPC. A second model also shows that LNGDPC is negatively affected by SoGI at the same level of significance, as confirmed by both OLS and FMOLS estimates. Likewise, EcGI negatively affects LNGDPC, with a coefficient that is significant at a level of 1 percent. On the other hand, DESI positively influences LNGDPC, also at 1 percent significance level.

Estimation Methods: The table presents results from four estimation methods:

- − OLS (Ordinary Least Squares)

- − FMOLS (Fully Modified Ordinary Least Squares)

- − DOLS (Dynamic Ordinary Least Squares)

- − CCR (Canonical Cointegration Regression)

We looked at the results of four estimation methods—OLS, FMOLS, DOLS, and CCR—with LNGDPC as the dependent variable. For all four, lnKI showed a positive and statistically significant coefficient (ranging from 0.0143 to 0.0224). This means that for every 1% increase in investment in capital intensity, there is a corresponding 0.0143 to 0.0224 increase in GDP per capita. This shows how important lnKI is for driving economic growth. The overall Globalization Index (GI) shows a strong negative relationship with GDP per capita under both OLS and DOLS estimations (e.g., −0.0228 and −0.0460, respectively). This result is contrary to Hypothesis 1 which suggested that globalization has a positive impact on economic growth in the Saudi economy. This suggests that government spending that is not used efficiently or correctly may have a negative effect on the economy.

Moreover, negative and significant coefficients of SoGI and EcGI vary within the ranges −0.0151 and −0.0236 for SoGI, and −0.0149 and −0.0189 for EcGI in FMOLS, DOLS, and CCR estimations, suggesting some short-term costs or constraining effects of measures of governance. On the contrary, positive and significant DESI has always demonstrated its contribution within the range from 0.0143 to 0.0272 across all estimations, which justifies how digitalization could work for higher economic growth. These findings support Hypothesis 2, which supposes that digitalization has a positive effect on economic growth in the Saudi economy. This supports the idea that digitalization contributes to economic growth by enhancing productivity and innovation. In fact, production, as well as ICT technologies, must find sources of competitive advantage in advanced ICT solutions designed effectively and efficiently by modern organizations, which is becoming increasingly important given the increasing need to integrate market mechanisms in the knowledge-based economy in development (Neffati, 2012) [69]. The constant term is significant across all methods, reflecting the baseline GDP per capita when all independent variables are zero. In terms of the model’s performance, OLS explains 52 percent of the variance in GDP per capita (R2 = 0.52) but has a Durbin–Watson statistic showing potential positive autocorrelation in residuals (Durbin–Watson statistic = 0.865), while FMOLS (R2 = 0.69) and CCR (R2 = 0.63) handle endogeneity and serial correlation. With the inclusion of lags and leads in the independent variables, DOLS therefore had the highest explanatory power with an R2 of 0.79, making the model most robust to explain the relationships of the variables. Overall, it follows from the results that investment in knowledge infrastructure and digitalization positively affects economic growth, while inefficiencies in government spending and governance measures may pose significant challenges.

4.2. ARDL Model, ECM Regression, and Bounds Test

The results presented in the accompanying Table 5 show that this model is best fitted among those presented, with a log-likelihood value of 124.55 at Lag 4. The sequential modified LR test statistic is 45.219, adding support for the inclusion of this lag, hence, this lag is significantly better than Lag 3. Lag 4 also has the minimum FPE with a value of 1.22 × 10−6, as well as the lowest AIC, SC, and HQ. Results suggest that Lag 4 represents the most appropriate and parsimonious model in the sense that it best balances fit and complexity. Based on all these criteria, Lag 4 is chosen as the optimum lag length of the VAR model.

Table 5.

VAR lag order selection criteria.

The ARDL model reveals that previous values of the per capita GDP, investment, economic governance, social governance, and digital economy are highly impacting the current value in GDP per capita growth. The error correction term also showed a robust correction mechanism to long-term equilibrium, hence demonstrating the strength of the model for both short- and long-term relationships. Overall, the evidence suggests that factors of governance along with investment play an essential role in economic growth, while there is rapid adjustment to maintain the long-term stable process.

Table 6 shows the ARDL and ECM regression results where one can clearly note significant coefficients for different lagged variables in order to derive their impact on GDP growth. In addition, the calculated F-statistic 9.5942 is very high compared with the upper bound critical values for all conventional significance levels, therefore confirming that there exists a long-term equilibrium relationship among the variables. The computed t-statistic (−10.790) is far below the lower bound critical values, thus reinforcing that co-integration among the variables does exist. Results of the cointegration and bounds tests (Table 7) confirm a high probability of the existence of cointegration among the variables in the model, meaning that they have a long-term equilibrium relationship. The null hypothesis of no co-integration is rejected at every level of significance; therefore, these estimations give greater validity to the long-term estimations emanating from this model, which essentially posits that, at a very core level in terms of economic analysis, the variables are indeed intertwined.

Table 6.

ARDL and ECM regression (selected model: ARDL (3, 4, 4, 1, 4)).

Table 7.

Cointegration and bounds tests.

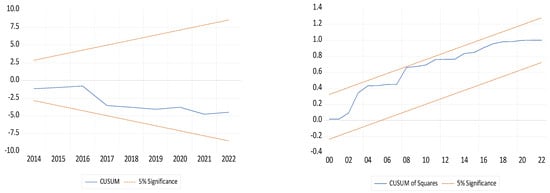

Based on the results of all the robustness tests given in Table 8 and CUSUM (Cumulative Sum Control Chart) and CUSUM of Squares in Figure 3, we can conclude that the ARDL estimated model is fitted and stable. Indeed, the Breusch–Godfrey serial correlation LM test for autocorrelation proves that the residuals obtained are free from serial correlation. The Obs *R-squared is 2.0216, and the p-value (0.2028) is greater than 0.05, meaning there is no serial correlation. Then, for the Jarque–Bera Test for Normality, the value is 1.9643, and a p-value of (0.3744) greater than 0.05 means a normal distribution. Finally, the Ramsey RESET Test for Specification 0.1944 (0.8276) is confirmed for Linear Data, and Functional Form.

Table 8.

ARDL model robustness check tests.

Figure 3.

CUSUM and CUSUM of Squares.

4.3. Discussion of Results

Given the significant interest the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia attaches to globalization, it is noteworthy that there exists a negative effect on GDP per capita. This result was contrary to Hypothesis 1, which supposed that globalization has a positive impact on economic growth. However, after the first lag, the effect becomes positive; look at Table 6. This means that the effect of globalization is not immediate; it needs time to have its effect. Many works have explained the negative impact of globalization and when it becomes positive. Bhagwati’s argument (2004) [13] elucidates the initial adverse effects of globalization, positing that a country’s readiness to capitalize on the benefits of the globalizing process determines the extent of the impact and the distributional effects. However, beyond a threshold of economic adjustment, globalization starts to have a positive impact on economic growth. Even though most transitional economies could not exploit the benefits arising out of globalization in the initial years, over time, they have received considerable remittances from workers abroad and dissemination of technology. Our findings resonate with Stiglitz’s (2002) [15] assertion that the intensive globalization process may not entirely surmount all social and economic challenges faced by diverse countries. Nevertheless, these economies have engaged in global markets, thereby exporting their goods and services. Therefore, many middle-income and transitional economies have been able to attain impressive growth using instruments of globalization: trade and financial integration. As inspired by comparative advantage, profound trade liberalization increases the competition between firms and nations, a situation further propelled by WTO provisions and technology. Previous empirical literature suggests that financial globalization does not necessarily result in more economic growth in developing countries. This was argued by Moshirian, 2008 [70], and was subsequently confirmed by Verhoeven and Ritzen, 2023 [71]. They also refer to numerous incidences in which foreign capital inflows have adversely affected economic growth under particular circumstances, a view which Prasad et al. (2007) [72] share when they propose that the Lucas Paradox has, if anything, become worse over time, although FDI capital flows do appear to be consistent with theoretical predictions.

5. Conclusions, Limitations and Research Perspectives

An analytical understanding of this nexus between socioeconomic globalization and digitalization plays a crucial role in the possible ways in which policymakers, enterprises, and civil society can start to address such emerging opportunities and challenges. Concretely, this involves developing an understanding of how digitalization works within global interconnection processes and devising strategies for more inclusive and sustainable development in a digital era. Most of the available literature refers to the fact that globalization has hit both developed and developing countries with several positive and negative impacts. However, the overall benefits from the process are rather unevenly distributed across nations, sectors, and individuals within the same country.

The findings, based on the estimation of the ARDL model, FMOLS, and DOLS, indicated the following:

- -

- Globalization indices (SoGI and EcGI) have a negative effect on LNGDPC at a 1% significance level, as confirmed by ARDL, FMOLS, DOLS, and OLS estimations. This suggests that globalization’s economic benefits are not evenly distributed and may present challenges for sustainable growth.

- -

- The Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) positively influences LNGDPC at a 1% significance level, highlighting the crucial role of digitalization in fostering economic development. This suggests that investments in digital infrastructure and technology can enhance economic productivity.

This implies that the challenges ahead are around enhancing productivity, with large-scale projects assuring revenue on a sustainable basis—a critical issue related to further economic growth and diversification. There must be initiatives for the nurturing of an environment for innovation support and investing in workforces, complementary to plans for economic diversification.

The present study has explored the limits and benefits of digital transformation and globalization, especially in terms of their impacts on developing nations like Saudi Arabia. With the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia so focused on globalization and digitalization, these factors are bound to bring a revolution to its economy. In addition, the available literature underlines that only robust national institutions and legal frameworks allow various countries to successfully exploit the benefits of globalization.

The results of this work proved that globalization and digitization both have positive impacts on economic growth in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia according to the ARDL estimation especially in lag 1 and lag 2 (see Table 6). However, these benefits are significantly shaped by the distinct attributes of its economy and the efficacy of its policies. As a result, the findings may not be readily applicable to other regions with distinct economic frameworks. Further inquiry is necessary to comprehend how certain technologies and digital advances might be utilized to enhance productivity and promote economic diversification in these nations. Moreover, research also needs to increasingly focus on sustainable development impacts of globalization and digitalization by understanding how these drivers of growth have brought inclusive development without accentuating the existing gaps. By understanding such constraints, future paths could be more accurately provided for scholars in assessing the complex dynamics facing globalization and digitization in most economic settings.

Funding

This research was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-RG23110).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Upon request to the corresponding author, the data will be made readily available.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ARDL | Autoregressive Distributed Lag |

| ASEAN | Association of Southeast Asian Nations |

| CUSUM | Cumulative Sum Control Chart |

| CCR | Canonical Cointegration Regression |

| DOLS | Dynamic Ordinary Least Squares |

| ECM | Error Correction Model |

| FMOLS | Fully Modified Ordinary Least Squares |

| OLS | Ordinary Least Squares |

| WTO | World Trade Organization |

References

- Dąbrowska, J.; Almpanopoulou, A.; Brem, A.; Chesbrough, H.; Cucino, V.; Di Minin, A.; Giones, F.; Hakala, H.; Marullo, C.; Mention, A.-L.; et al. Digital transformation, for better or worse: A critical multi-level research agenda. RD Manag. 2022, 52, 930–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahalik, M.K.; Babu, M.S.; Loganathan, N.; Shahbaz, M. Does financial development intensify energy consumption in Saudi Arabia? Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 75, 1022–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Mahalik, M.K.; Shahzad, S.J.H.; Hammoudeh, S. Testing the globalization-driven carbon emissions hypothesis: International evidence. Int. Econ. 2019, 158, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Nasir, M.A.; Roubaud, D. Environmental degradation in France: The effects of FDI, financial development, and energy innovations. Energy Econ. 2018, 74, 843–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Mallick, H.; Mahalik, M.K.; Loganathan, N. Does globalization impede environmental quality in India? Ecol. Indic. 2015, 52, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed Hashim, M.A.; Tlemsani, I.; Matthews, R. Higher education strategy in digital transformation. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 3171–3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanelt, A.; Bohnsack, R.; Marz, D.; Antunes Marante, C. A systematic review of the literature on digital transformation: Insights and implications for strategy and organizational change. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 58, 1159–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solow, R.M. A contribution to the theory of economic growth. Q. J. Econ. 1956, 70, 65–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala-i-Martin, X.X.; Barro, R.J. Technological Diffusion, Convergence, and Growth; Center Discussion Paper no. 735; Yale University, Economic Growth Center: New Haven, CT, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, G.M.; Helpman, E. Technology and trade. In Handbook of International Economics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1995; Volume 3, pp. 1279–1337. [Google Scholar]

- Oliner, S.D.; Sichel, D.E.; Triplett, J.E.; Gordon, R.J. Computers and output growth revisited: How big is the puzzle? Brook. Pap. Econ. Act. 1994, 25, 273–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, L. The digital economy, ICT and economic growth in the CEE countries. Olszt. Econ. J. 2015, 10, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagwati, J. Anti-globalization: Why? J. Policy Model. 2004, 26, 439–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crafts, N. Globalisation and economic growth: A historical perspective. World Econ. 2004, 27, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, J. Development policies in a world of globalization. In New International Trends for Economic Development Seminar; Brazilian Economic and Social Development Bank (BNDES): Rio Janeiro, Brazil, 2002; pp. 1–27. Available online: https://business.columbia.edu/sites/default/files-efs/pubfiles/1454/Stiglitz_DevelopmentPolicies.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Stiglitz, J.E. Making Globalization Work; W.W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dreher, A. Does globalization affect growth? Evidence from a new index of globalization. Appl. Econ. 2006, 38, 1091–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M. Environmental degradation: The role of electricity consumption, economic growth and globalisation. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 253, 109742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kose, M.A.; Prasad, E.; Rogoff, K.; Wei, S.J. Financial globalization: A reappraisal. IMF Staff Pap. 2009, 56, 384–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.J. Connecting two views on financial globalization: Can we make further progress? J. Jpn. Int. Econ. 2006, 20, 459–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daude, C.; Stein, E. The quality of institutions and foreign direct investment. Econ. Politics 2007, 19, 317–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uusitalo, P.; Lavikka, R. Technology transfer in the construction industry. J. Technol. Transf. 2021, 46, 1291–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollar, D.; Kraay, A. Trade, growth, and poverty. Econ. J. 2004, 114, F22–F49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirst, P.; Thompson, G. Globalisation Ten Frequently Asked Questions and Some Surprising Answers. Soundings 1996, 47–66. [Google Scholar]

- Omoke, P.C.; Opuala-Charles, S. Trade openness and economic growth nexus: Exploring the role of institutional quality in Nigeria. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2021, 9, 1868686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderon, C.; Fuentes, R. Complementarities between institutions and openness in economic development: Evidence for a panel of countries. Cuad. De Econ. 2006, 43, 49–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.P.; Berdiev, A.N.; Lee, C.C. Energy exports, globalization and economic growth: The case of South Caucasus. Econ. Model. 2013, 33, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Dong, B. A theory of financial liberalisation: Why are developing countries so reluctant? World Econ. 2011, 34, 1106–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samimi, P.; Jenatabadi, H.S. Globalization and economic growth: Empirical evidence on the role of complementarities. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M.J.; Lee, D.J.; Miller, C.; Littlefield, J.E. The impact of globalization on a country’s quality of life: Toward an integrated model. Soc. Indic. Res. 2004, 68, 251–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Lehmann, E.E.; Wright, M. Technology transfer in a global economy. J. Technol. Transf. 2014, 39, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. World Development Report: Trading for Development in the Age of Global Value Chains; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). World Economic Outlook. 2021. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2021/10/12/world-economic-outlook-october-2021 (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. Trade and Development Report; United Nations Conference on Trade and Development: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- World Trade Organization. World Trade Report, Economic Resilience and Trade; World Trade Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. Available online: https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/wtr21_e/00_wtr21_e.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Outlook, Annex 2. A. Assessing the Impact of FDI on Productivity and Innovation; FDI Qualities Policy Toolkit; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022; p. 81. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, R. Globalization: Social Theory and Global Culture; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, R. If this is Globalization 4.0, what were the other three? World Economic Forum, 22 December 2018. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2018/12/if-this-is-globalization-4-0-what-were-the-other-three (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Baldwin, R. The Great Convergence: Information Technology and the New Globalization; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Manyika, J.; Lund, S.; Bughin, J.; Woetzel, L.; Stamenov, K.; Dhingra, D. Digital Globalization: The New Era of Global Flows; McKinsey Global Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum. Advancing Digital Trade in a Fragmented World. Annual Report 2022–2023. Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Annual_Report_2022-23.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD Digital Economy Outlook 2022; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/digital/oecd-digital-economy-outlook-2022-ade8c7e2-en.htm (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Hart, J. Globalization and Digitalization. Academia.edu. 2010. Available online: https://hartj.pages.iu.edu/documents/globalization_digitalization.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Sabbagh, K.; Friedrich, R.; El-Darwiche, B.; Singh, M.; Ganediwalla, S.; Katz, R. Maximizing the impact of digitization. Glob. Inf. Technol. Rep. 2012, 2012, 121–133. [Google Scholar]

- Neffati, M.; Gouidar, A. Socioeconomic impacts of digitisation in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2019, 9, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neffati, M.; Jbir, R. The impact of digitalization and economic diversification on economic growth: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2024, 30, 1510–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sahli, S.; Bardesi, H. Digital Transformation Strategies Across Saudi Arabia. Digital Government Authority, Meta Study: 2024. Public Issue No.: 1.0. Available online: https://dga.gov.sa/sites/default/files/2024-10/Digital%20Transformation%20Strategies%20Across%20Saudi%20Arabia-%20V1.0.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2024).

- Havrlant, D.; Abdulelah, D. Economic Diversification Under Saudi Vision 2030; Discussion paper KS–2021-DP06; KAPSARK: Riad, Saudi Arabia, 2021; Available online: https://www.kapsarc.org/research/publications/economic-diversification-under-saudi-vision-2030/ (accessed on 23 January 2024).

- Khan, M. Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030: An Overview. Middle East Policy 2019, 26, 102–116. [Google Scholar]

- Hilbert, M. The Bad News is that the Digital Divide is Widening: The Good News is that the Internet Diffusion is Slowing. Telecommun. Policy 2016, 40, 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragnedda, M.; Muschert, G.W. The Digital Divide: The Internet and Social Inequality in International Perspective; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pesaran, M.H.; Shin, Y.; Smith, R.J. Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. J. Appl. Econom. 2001, 16, 289–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banday, U.J.; Aneja, R. Energy consumption, economic growth and CO2 emissions: Evidence from G7 countries. World J. Sci. Technol. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 16, 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaari, M.S.; Asbullah, M.H.; Abidin, N.Z.; Karim, Z.A.; Nangle, B. Determinants of foreign direct investment in ASEAN+ 3 Countries: The role of environmental degradation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandil, M.; Mirzaie, I.A. Macroeconomic policies and the Iranian economy in the era of sanctions. Middle East Dev. J. 2021, 13, 78–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmani-Oskooee, M.; Ratha, A. Exchange rate volatility and trade flows: A review article. J. Econ. Stud. 2007, 42, 1028–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, A.; Mavrotas, G. FDI and growth: What causes what? World Econ. 2006, 29, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H.; Shin, Y. An Autoregressive Distributed-Lag Modelling Approach to Cointegration Analysis. In Econometrics and Economic Theory in the 20th Century: The Ragnar Frisch Centennial Symposium; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998; Volume 31, pp. 371–413. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI). 2021. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/digital-economy-and-society-index-desi-2021 (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Potrafke, N. The evidence on globalization. World Econ. 2015, 38, 509–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olczyk, M.; Kuc-Czarnecka, M. Digital transformation and economic growth: DESI improvement and implementation. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2022, 28, 775–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, S. Estimation and hypothesis testing of cointegration vectors in Gaussian vector autoregressive models. Econometrica 1991, 59, 1551–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, R.F.; Granger, C.W.J. Co-Integration and Error Correction: Representation, Estimation, and Testing. Econometrica 1987, 55, 251–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbarek, M.B.; Nasreen, S.; Feki, R. The contribution of nuclear energy to economic growth in France: Short and long run. Qual. Quant. 2017, 51, 219–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbarek, M.B.; Saidi, K.; Feki, R. How effective are renewable energy in addition to economic growth and curbing CO2 emissions in the long run? A panel data analysis for four Mediterranean countries. J. Knowl. Econ. 2018, 9, 754–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidi, K.; Mbarek, M.B. Nuclear energy, renewable energy, CO2 emissions, and economic growth for nine developed countries: Evidence from panel Granger causality tests. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2016, 88, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoma, J.B.; Yang, L. Does economic performance matter for forest conversion in Congo Basin tropical forests? FMOLS-DOLS approaches. For. Policy Econ. 2024, 162, 103199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackinnon, J.G.; Haug, A.A.; Michelis, L. Numerical distribution functions of likelihood ratio tests for cointegration. J. Appl. Econom. 1999, 14, 563–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neffati, M. Ict, Informational Innovation and Knowledge-based Economy. Ann. Univ. Apulensis Ser. Oeconomica 2012, 14, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshirian, F. Globalisation, growth and institutions. J. Bank. Financ. 2008, 32, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoeven, L.; Ritzen, J. Globalisation and Trust in Europe between 2002 and 2018. Res. Glob. 2023, 7, 100142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, E.S.; Rogoff, K.; Wei, S.J.; Kose, M.A. Financial globalization, growth and volatility in developing countries. In Globalization and Poverty; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2007; pp. 457–516. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).