Abstract

This study explores community-driven projects, participatory governance, and adaptive urban policies to enhance social resilience and sustainability in urban environments. By combining a comprehensive literature review, a questionnaire survey, and practical recommendations, it underscores the importance of socioeconomic equality, cultural heritage preservation, and inclusive growth. Through both qualitative and quantitative analyses that incorporate a broad review of scientific literature and a focused survey within Lithuania, this study identifies key strategies for strengthening urban resilience. It highlights the critical role of community engagement in urban planning and the preservation of heritage as a means to maintain local identity and foster civic participation. These elements collectively contribute to more resilient, inclusive, and sustainable urban spaces.

1. Introduction

This research paper explores key aspects of social resilience in urban neighborhoods, with a focus on understanding the complex interplay between the built environment, cultural heritage, civic engagement, and community empowerment. As urban areas face increasing challenges due to rapid change, globalization, uncertainty, ecological challenges, and social inequalities, fostering resilient communities has become a central concern in urban studies. The increasing number of research and publications on the topic of social resilience justifies the relevance of this topic. Social resilience is increasingly recognized as an essential component of urban resilience, reflecting the ability of urban communities and neighborhoods to adapt, reorganize, and transform in response to various shocks and stresses [1]. The term “resilience” primarily originates from natural sciences and refers to the ability of systems to cope with shocks or major changes in external circumstances. Thus, resilience, as applied to society, including urban communities and neighborhoods, is clearly different from other strategies associated with social responses to environmental challenges [2]. According to Keck and Sakdapolrak [2], the concept of resilience has progressively developed from its initial focus on the enduring functionality of ecological systems amidst continuous change to an emphasis on interconnected social–ecological systems and human adaptation within nature, culminating in its latest refinement, which addresses the critical issue of social transformation in response to global challenges [2].

The research paper consists of the following:

- -

- Literature review, focusing on potentials and barriers to social resilience in neighborhoods, the built environment and heritage aspects for local identity, community empowerment tools, and aspects on strengthening social resilience in urban neighborhoods.

- -

- Questionnaire survey study, focusing on social, environmental, heritage, economical, and resilience aspects of the urban neighborhood.

- -

- Proposed steps and actions. It is a theoretical conceptualization and formulation of the suggested directions of steps/actions for solving identified issues related to the social resilience of communities in urban neighborhoods.

Existing studies demonstrate that socioeconomic equality, inclusive growth, and cultural heritage preservation significantly enhance social resilience by fostering collective identity, community empowerment, and active civic participation, thus strengthening the capacity of communities to respond effectively to external disturbances [3,4]. By preserving heritage assets and nurturing local identities, urban communities not only maintain historical continuity but also promote social cohesion, a critical element in mitigating vulnerability and enhancing adaptive capacities [3]. Furthermore, inclusive urban policies and participatory governance frameworks enable communities, especially at the neighborhood scale, to actively engage in shaping sustainable futures, thus bridging local empowerment with broader urban resilience objectives [1].

This research aims to explore how community resilience can be fostered through the integration of heritage values, participatory mechanisms, and adaptive urban policies. The study focuses on Lithuania to examine how these global themes appear in a specific socio-political and cultural context. The Lithuanian case offers insights into emerging models of governance, contested heritage, and evolving civic agency, with relevance to other countries navigating similar structural and cultural shifts.

The empirical part of this research is situated within the Lithuanian context, a country characterized by its abundant urban built heritage and undergoing dynamic socioeconomic transitions typical of Central and Eastern Europe. Exploring social resilience in Lithuania provides valuable insights into how urban neighborhoods navigate the complexities of heritage preservation, community participation, and policy adaptation under ongoing societal transformations.

The following research questions guide this research:

- How do adaptive policies, participatory governance, and heritage conservation initiatives interact to enhance community resilience in urban settings?

- What roles do heritage elements play in strengthening community identity and social cohesion within urban neighborhoods?

- What are the barriers and facilitators to effective community participation in urban resilience initiatives?

This research addresses several gaps identified in the current context:

- Integration of cultural heritage: while individual studies have focused on the role of heritage in urban resilience, there is a lack of comprehensive research integrating heritage with modern urban policy and community participation.

- Participatory governance: existing research often overlooks how participatory governance can be effectively implemented to enhance community resilience, particularly in diverse urban settings.

- Socioeconomic inequalities: there is a need to explore how adaptive urban policies can address socioeconomic inequalities within the framework of urban resilience.

2. Methodology

This section outlines the methodological approach used in this study, which is supported by established theoretical frameworks that guide the exploration of urban resilience, cultural heritage, and participatory governance. The methodology is designed to ensure data collection, analysis, and interpretation that align with the objectives of contributing new insights to the literature.

- Outline of theoretical frameworks

Urban resilience theory: This study is grounded in the theory of urban resilience, which views cities as complex adaptive systems that can absorb, recover, and prepare for future stresses. Key authors like Folke et al. [5] and Meerow et al. [1] provide foundational insights that frame our understanding of resilience as a multi-dimensional and dynamic process.

Cultural heritage and identity theory: drawing on the works of [6,7], this study integrates the theory of heritage as a social and cultural process that contributes to the identity, cohesion, and resilience of urban communities.

Participatory governance framework: inspired by the principles outlined by Arnstein [8] on citizen participation and recent developments by Innes and Booher [9], this study examines how participatory governance can be effectively implemented to enhance civic engagement and urban resilience.

Methodological approach applied in this study:

- Literature review: an extensive review of the existing literature to map the current knowledge landscape, identify gaps, and define the scope of how heritage and governance contribute to urban resilience.

- Empirical research design through a quantitative survey: Distributed among residents to assess perceptions of community identity, engagement in governance, and attitudes towards urban resilience initiatives, Lithuania was selected as a case study due to its unique urban development trajectory, European integration, and increasing attention to heritage-led planning. The country’s evolving planning and participation systems offer a valuable lens through which to examine tensions and synergies between policy, identity, and grassroots engagement.

2.1. Literature Review

The literature review is based on qualitative and quantitative data, including both systematic and unsystematic literature reviews. The literature for the review was accumulated from scientific literature databases, such as Web of Science, Scopus, Google Scholar and from available Internet search engines. A quantitative literature review was performed based on Web of Science database search results. A graphical analysis of bibliometric data was performed using the VOSviewer (2024) software. The graphical bibliometric analysis presented in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4 provides insights into current thematic clusters and research gaps and visualizes how the literature on neighborhood resilience, heritage, civic engagement, and community empowerment is structured, highlighting opportunities for greater interdisciplinary integration. Understanding these research clusters helps clarify the current state of research and guides the identification of strategies to enhance social resilience in urban neighborhoods.

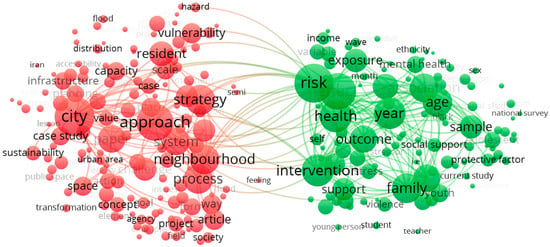

Figure 1.

Thematic clusters in the neighborhood resilience literature indicating the separation between spatial and socio-demographic research dimensions. Graph created using the VOSviewer (2024) software.

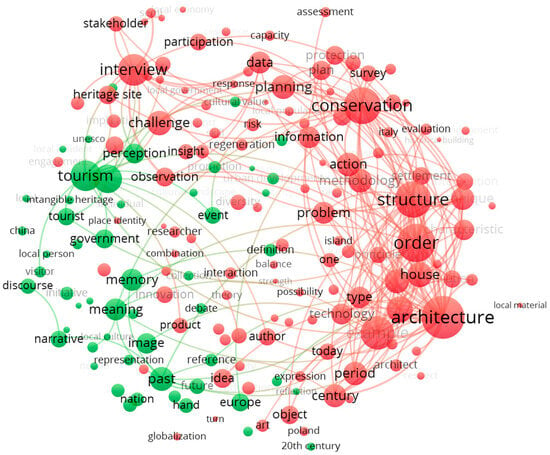

Figure 2.

Integrated thematic clusters illustrating connections between architectural, social-participatory, and theoretical approaches to heritage and local identity in the literature. Graph created using the VOSviewer (2024) software.

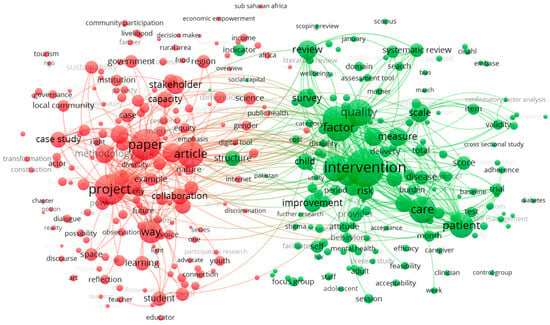

Figure 3.

Main research clusters in the community empowerment literature, highlighting distinct social-spatial and healthcare-oriented research areas. Graph created using the VOSviewer (2024) software.

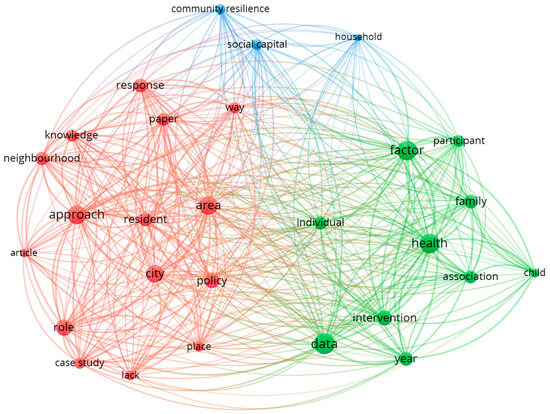

Figure 4.

Integrated interdisciplinary clusters of spatial and theoretical concepts, as well as socio-demographic factors emerging in the literature on social resilience in neighborhoods. Graph created using the VOSviewer (2024) software.

The following topics were analyzed in the literature review:

- Potentials and barriers to social resilience in neighborhoods.

- The built environment and heritage aspects for local identity and civic engagement.

- Community empowerment tools.

- Strengthening social resilience in urban neighborhoods.

2.2. Questionaries’ Survey

The research focuses on Lithuania as a case study. Lithuania offers a convincing context for examining the intersections of heritage preservation, participatory planning, and urban resilience. The country’s cities, particularly in the context of European integration and evolving governance structures, reflect many of the tensions faced by transitional urban systems, including contested narratives of identity, underdeveloped civic participation mechanisms, and challenges in integrating historic urban elements with contemporary development. This makes Lithuania a valuable case for deriving insights relevant to other regions experiencing similar transitions.

The research ethics commission of Kaunas University of Technology, Lithuania, assessed and approved the application submitted by prof Lina Šeduikytė to perform an online survey on social resilience in urban neighborhoods across Europe. Approval document Nr. M6-2024-10 (28 May 2024).

The questionaries survey was performed in Lithuania in the period of June–September 2024. The online survey was anonymous; in all cases, answers were analyzed only in summary form. Neither the individual responses nor the results of data analysis allowed for the identification of any participant.

The questionnaire was distributed via Google Forms, a widely used online platform that enables anonymous and secure data collection. Google Forms does not collect identifying metadata unless actively enabled by the researcher, which was not the case in this study. Respondents were informed of the anonymous nature of the survey before participation. The platform’s built-in data privacy protections, combined with the researchers’ decision to avoid collecting personally identifiable information, ensured full compliance with data protection principles. These technical features influenced the study design by supporting ethical standards related to confidentiality, voluntary participation, and the secure storage of responses.

The structure of the questionnaire was based on the conceptual understanding that local identity and social resilience are influenced by residents’ perceptions of cultural heritage, inclusiveness, and diversity. Research on place attachment and cultural sustainability suggests that the recognition of heritage values contributes to a sense of belonging and shared memory, which are foundational to community resilience [10,11]. Similarly, inclusive and diverse neighborhoods are more likely to foster adaptive capacity and mutual support networks, especially during crises or transitions [1,12]. Accordingly, the questionnaire included sections aimed at capturing how residents perceive symbolic and material heritage features, whether they feel their communities are inclusive and welcoming, and how these perceptions relate to broader feelings of empowerment and trust in urban systems.

The questionnaire included a dedicated section on community empowerment tools aimed at understanding how residents evaluate their opportunities to participate in neighborhood planning and how they perceive their own roles in shaping urban resilience. This approach reflects the view that community resilience is not only built through physical infrastructure or institutional policies but also through the empowerment of local actors to contribute meaningfully to governance processes [13,14]. Survey items asked residents to identify whether they see themselves as observers, partners, leaders, or passive consumers in planning processes and to assess the responsiveness of formal decision-making structures to their inputs. These indicators offer insights into both the capacity and readiness of communities to participate in building resilience. Measuring these subjective roles and perceptions is essential for identifying barriers to empowerment and for informing more inclusive and effective participatory models at the neighborhood level [15,16].

2.3. Data Analysis

The Python programming language with a Jupyter Notebook v. 7.3.3. environment, Matplotlib v. 3.10.0, NumPy v. 2.2.1, Statsmodels v. 0.14.4, Pandas v.2.2.3, and other libraries were used for results analyses and chat plotting.

The results of closed questions are presented in percentage expression; the results of the open questions are presented in numbers, as several options were possible.

The survey included both closed-ended and open-ended questions. No inferential statistical procedures were applied, as the aim was to identify general patterns in perceptions, values, and engagement behaviors.

Open-ended responses were analyzed using a qualitative thematic approach. All textual responses were read manually by the lead researcher and grouped into themes through inductive coding, allowing recurring ideas and narratives to emerge from the data. This process followed the principles of thematic analysis, as outlined in [17]. Themes were reviewed and refined to ensure internal coherence and conceptual clarity. The frequencies of theme occurrence were occasionally used to indicate which topics were most salient across responses, but this was performed for illustrative purposes only and not as a quantitative measure of significance.

All qualitative data were treated in accordance with ethical guidelines. Responses were anonymous, and no quotations or identifiers that could potentially reveal participants’ identities were used. The decision to thematically group open-text responses was made to preserve the richness of qualitative feedback while maintaining respondent confidentiality and analytical clarity.

Inclusion Criteria:

- Participants must be residents of the urban neighborhoods under study for at least one year to ensure that they have sufficient exposure to local dynamics.

- Participants must be aged 18 and above.

- Studies included in the literature review must be peer-reviewed articles published within the last 20 years, ensuring current relevance and scientific rigor.

- Studies must explicitly address at least one of the following: urban resilience, cultural heritage, or participatory governance.

Exclusion Criteria:

- Studies or data older than 20 years, unless they are seminal works in the field.

- Non-English language sources, unless significant and pertinent information is available and translatable.

- Participants under the age of 18 or those who have lived in the area for less than one year, to maintain a focused and experienced respondent base.

- Studies that focus solely on rural resilience without applicability to urban contexts.

3. Literature Review

This literature analysis section reviews and synthesizes existing research in order to contextualize the links and interactions between social resilience, built heritage, civic engagement, and community empowerment within urban neighborhoods. The literature review is organized into four thematic subsections—potentials and barriers to social resilience in neighborhoods, the built environment and heritage aspects for local identity and civic engagement, community empowerment tools, and strengthening social resilience in urban neighborhoods—to systematically address key dimensions of social resilience in urban neighborhoods. First of all, the review explores potentials and barriers to social resilience at the neighborhood scale, providing a foundation for understanding resilience-building dynamics. Subsequently, it addresses the significance of the built environment and cultural heritage as crucial elements shaping local identity and fostering civic participation. Finally, it focuses on the available community empowerment tools and strategic interventions that strengthen social resilience, highlighting their effectiveness and limitations in enhancing sustainable urban development.

3.1. Potentials and Barriers to Social Resilience in Neighborhoods

The concept of social resilience in neighborhoods refers to the capacity of communities to adapt, recover, and thrive amid external shocks, such as economic changes or environmental disasters. According to Barr and Devine-Wright [17], community resilience includes both prevention and response components that aim to strengthen communities’ ability to withstand shocks from the outside world. In this sense, resilience may include interventions for adaptation (a type of reactionism) and mitigation (prevention), but it is also an active, community-based, internally motivated, and comprehensive strategy that should, in principle, offer more defense against external shocks [17]. In order to understand the state of research and the relevance of the topic, quantitative and qualitative analyses of the literature were performed. The quantitative review of the literature on the topic of social resilience in neighborhoods was carried out in the Web of Science’s scientific literature database. The search using the keyword combination “social resilience in neighborhoods” provided 1281 search results. The graphical analysis is presented in Figure 1. Meanwhile, the search using the keywords “social resilience” provided 58,206 results. This demonstrates the substantial interest of the research community in social resilience. However, the presence of a particular urban, spatial context significantly limits the search results. The results of the search “social resilience in neighborhoods” are distributed in the period between 1996 and the present day. The trend of growth in the number of publications is evident, especially from 2018. For comparison, it is possible to note that in the period between 1996 and 2006, less than ten publications were published per year. Meanwhile, in 2019, 107 publications were published; in 2020, 138 were published; in 2021, 172 were published; in 2022, 153 were published; in 2023, 167 were published; and in 2024, 118 publications were published. The majority of publications—1162—are journal articles. The following research areas have the highest number of publications on social resilience in neighborhoods: Environmental Sciences and Ecology (272 publications); Psychology (211); Public Environmental and Occupational Health (194); Urban Studies (162); Science, Technology, and Other Topics (125); and Social Work (100). The most relevant journals in research on social resilience of neighborhoods are Sustainability, the International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, and the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. The distribution of search results according to their relevance to UN sustainable development goals is the following: goal 03 Good Health And Well-Being: 509 publications, goal 13 Climate Action: 278, goal 11 Sustainable Cities And Communities: 217, goal 10 Reduced Inequality: 42, goal 16 Peace And Justice Strong Institutions: 37, goal 04 Quality Education: 29, goal 15 Life On Land: 29, goal 01 No Poverty: 26, goal 05 Gender Equality: 26, goal 02 Zero Hunger: 23, goal 06 Clean Water And Sanitation: 14, goal 09 Industry Innovation And Infrastructure: 13, goal 07 Affordable And Clean Energy: 11, goal 12 Responsible Consumption And Production: 8, goal 08 Decent Work And Economic Growth: 1, and goal 14 Life Below Water: 1 publication. The most cited publication in the field of research on social resilience of neighborhoods is by Bratman et al. [18] on nature’s influence on mental health from the ecosystem’s services perspective. The literature review revealed the growing interest in social resilience in neighborhoods and the importance of environmental and ecological components in it. The fact that the research area of Urban Studies is the fourth according to the number of publications as well as the high number of publications relevant to the 11th UN sustainable development goal demonstrates an important role of Urban Studies in the research of social resilience in neighborhoods. This importance may even increase in the future with the growing importance of various trends of sustainable urbanism. According to T. Larimian et al. [19], the resilience of urban neighborhoods plays a critical role in the overall resilience of cities and populations in highly urbanized countries or regions. Figure 1 presents a graphical analysis using the VOSviewer (2024) software of the terms generated from the bibliometric results of a search in the Web of Science’s scientific literature database using the keyword combination “social resilience in neighborhoods.” The graph illustrates two distinct clusters of term usage: one centered on spatial concepts, such as city, space, and infrastructure (red color), and the other on social–demographic terms (green color). The existence of such separated clusters of terms may demonstrate the need for a closer integration of the spatial dimension, including urban environments and neighborhoods, into social resilience research.

The qualitative analysis of selected literature sources has demonstrated that potentials for fostering social resilience lie in strengthening social networks, encouraging civic engagement, and ensuring inclusive urban policies that promote equity and participation [20]. Social participation plays a crucial role in building resilience, as it fosters a sense of belonging, mutual support, and shared responsibility [21,22]. Barriers to social resilience often include socioeconomic inequalities, spatial segregation, and insufficient access to resources [23] or decision-making processes [20]. Democratic development in urban communities can enhance resilience by creating spaces for collective decision-making, ensuring that marginalized voices are heard, and promoting transparency. Bottom-up participatory activities, participatory urban planning that applies various accessible tools, and practices like workshops, online platforms, and the gamification of participatory practices can be very important tools for strengthening social resilience [22,23]. Combined together with data analysis, simulations and modeling the results of participatory practices can not only empower communities but also contribute to the practices of urban planning with data-based and community-driven proposals [21]. Achieving urban sustainability requires a balance between ecological, economic, and social dimensions [24]. According to Lozano [25], to achieve societal sustainability, we must regard it as a comprehensive, ongoing, and interconnected phenomenon encompassing economic, environmental, and social dimensions, with each decision bearing consequences for all elements both presently and in the future. Thus, resilient communities should be better equipped to handle long-term urban challenges, and environmental sustainability-oriented interventions must become an integral part of place-making and resilient community development. The potential of nature-based solutions for urban regeneration must be considered in this context as well [26].

Nature-based solutions have been recognized as strategies that address a wide range of urban challenges, including climate resilience, green space management, health and well-being, social cohesion, and participatory governance [26]. While often discussed in ecological or infrastructural terms, many of these challenges, such as place regeneration, social justice, and inclusiveness, are fundamentally social in nature. These dimensions align closely with this study’s objectives, particularly the investigation of how community-based values, cultural identity, and participatory tools contribute to urban resilience at the neighborhood scale. By highlighting the societal functions of nature-based solutions, this framework provides additional justification for analyzing resident perceptions of inclusiveness, governance, and cultural meaning as key elements of neighborhood resilience.

3.2. The Built Environment and Heritage Aspects for Local Identity and Civic Engagement

It is acknowledged that the built environment and cultural heritage play a significant role in shaping local identity and fostering civic engagement. In order to understand the present-day state of research on this topic, quantitative and qualitative analyses of the literature were performed. The quantitative review of the literature on the topic of the role of built heritage in fostering local identity and civic engagement in neighborhoods was carried out in the Web of Science’s scientific literature database. The search using the keyword combination “built heritage and civic engagement” provided 24 search results. Meanwhile, the search using the keywords “built heritage and local identity” provided 614 results. The graphical analysis is presented in Figure 2. This demonstrates the higher interest in the role of heritage in local identity development and preservation compared to the role of built heritage in fostering civic engagement. The results of the search “built heritage and local identity” are distributed in the period between 1994 and the present day. The trend of slight growth in the number of publications is visible, especially from 2018; however, the number of publications per year does not exceed one hundred. For example, in 2018, 41 publications were published; in 2019, 69 were published; in 2020, 59 were published; in 2021, 69 were published, in 2022, 74 were published; in 2023, 67 were published; and in 2024, 28 publications were published up to this day. The majority of publications—462—are journal articles. The following research areas have the highest number of publications on built heritage and local identity: Environmental Sciences and Ecology: 106 publications; Architecture: 101; Arts, Humanities, and Other Topics; 87; Science, Technology, and Other Topics: 86; and Social Sciences and Other Topics: 86 publications. Meanwhile, the research area of Urban Studies has 38 publications. The most relevant journals in research on built heritage and local identity are Sustainability and the International Journal of Heritage studies. The distribution of search results according to their relevance to UN sustainable development goals is the following: goal 11 Sustainable Cities And Communities: 214 publications, goal 15 Life On Land: 43, goal 13 Climate Action: 38, goal 09 Industry Innovation And Infrastructure: 26, goal 04 Quality Education: 25, goal 12 Responsible Consumption And Production: 16, goal 02 Zero Hunger: 11, goal 05 Gender Equality: 11, goal 01 No Poverty: 9, goal 03 Good Health And Well-Being: 9, goal 10 Reduced Inequality: 9, goal 16 Peace And Justice Strong Institutions: 7, goal 08 Decent Work And Economic Growth: 2, goal 14 Life Below Water: 2, goal 06 Clean Water And Sanitation: 1, and goal 07 Affordable And Clean Energy: 1 publication. The most cited publication in the field of research on built heritage and local identity is by Bessière [27] on the role of local food and cuisine in local development and tourism. The second most cited publication deals with the topics of globalization, global events, and their influence on local identity [28]. Meanwhile, the results of the search “built heritage and civic engagement” are distributed in the period between 1999 and the present day with up to five papers published per year. The distribution of this search results according to their relevance to UN sustainable development goals is the following: goal 11 Sustainable Cities And Communities: nine publications, goal 04 Quality Education: two, goal 05 Gender Equality: two, goal 12 Responsible Consumption And Production: two, goal 03 Good Health And Well-Being: one, goal 10 Reduced Inequality: one, goal 13 Climate Action: one, and goal 15 Life On Land: one publication. The most cited paper in this research area is from community psychology; however, the second most cited paper is directly related with the topic of this review, namely participation and the adaptive reuse of cultural heritage [29]. Figure 2 presents the graphical analysis using the VOSviewer (2024) software of the use of terms generated from the bibliometric results of search in the Web of Science’s scientific literature database using the keyword combination ‘built heritage and local identity’. The graph demonstrates the close integration of two main clusters of the use of terms centered around architecture, social actors in urban space and participation (red color), and general terms related with heritage theory, interpretation, etc. (green color), highlighting strong connections between architectural, social-participatory, and theoretical perspectives on the role of heritage in local identity.

Numerous researchers have analyzed the role of cultural heritage in the context of sustainable development, including the social and cultural dimensions of sustainability. For example, Tweed and Sutherland [30] examined the degree to which the developing idea of sustainability embraces built heritage and the ways in which it helps to meet both societal and personal requirements. They made a distinction between the social (cultural) dimension, which includes cultural identity and the passing on of cultural capital to future generations; the economic dimension, which includes urban regeneration, tourism, and the ensuing positive economic impact; and the environmental dimension, which primarily focuses on the effects of pollution on buildings. Meanwhile, Murzyn-Kupisz and Działek [31] note that both physical and intangible cultural heritage have a positive influence on communities and society in many ways, including serving as gathering spots and community centers, places for social integration and inclusion, sources of identity and local uniqueness, and the driving force behind shared initiatives and activities by volunteers and organizations. The increasingly popular concept of the historic urban landscape (HUL) can be applied in order to better understand and meaningfully employ the interconnections between the historic environment and society, as the historic urban landscape, according to its definition, includes not only tangible components but, among others, also social and cultural practices and values, economic processes, and the intangible dimensions of heritage as related to local distinctiveness and identity [32,33]. The physical landscape of a community, including its architecture, public spaces, and historical landmarks, contributes to a shared sense of place and belonging among residents. Concepts like place attachment and sense of belonging represent the emotional connections that people or groups form with a built, or typically biophysical, environment. Affective bonds are important factors that determine people’s sense of place, which in turn affects place-related behavior and emplacement processes that bind people and place together. They are tied to both functional dependency and emotional connection [19]. Heritage elements, such as monuments, traditional buildings, and culturally significant sites, serve as touchstones for collective memory, reinforcing continuity with the past and anchoring local identity. These intangible phenomena induced by heritage–society interactions can be related to the phenomenon of the spirit of place (genius loci). M. Vecco [34] had analyzed the spirit of place phenomenon as undoubtedly linked with heritage in the context of sustainability. When people feel a connection to the built environment and their community’s history, they are more likely to engage in civic activities, such as participating in local governance or community initiatives, for example, those related to heritage preservation. The preservation of cultural heritage can also act as a catalyst for civic pride, inspiring residents to take an active role in protecting and enhancing their neighborhoods, for example, through low-cost bottom-up heritage actualization initiatives [35]. Recent research highlights that preserving cultural heritage, both built and intangible, can strengthen community resilience by reinforcing shared identity, social cohesion, and local knowledge [36]. Active community participation in heritage preservation is shown to foster social capital, a sense of ownership and pride, which in turn boosts collective solidarity and the capacity to recover from crises [37]. Studies also note that traditional cultural knowledge provides adaptive capacity, and communities draw on inherited practices and memories to detect hazards early, adapt to change, and improve disaster preparedness [36]. Emerging frameworks for heritage-led resilience advocate integrating preservation with adaptive reuse and inclusive governance, leveraging a sense of place and cultural continuity as catalysts for community engagement and learning in the face of disruptions [38]. However, threats to heritage, such as gentrification or neglect, can weaken local identity and disengage residents. In urban development, integrating both contemporary and historical elements thoughtfully can promote a sense of continuity, respect for heritage, and deeper civic involvement and community resilience. This connection between the built environment, heritage, and civic engagement and resilience is essential for fostering sustainable and cohesive urban communities. Rypkema [39] has identified the key characteristics of successful communities, such as a feeling of community and ownership, a sense of location and identity, etc. He asserts that these characteristics can be produced and reinforced by built heritage: historic buildings and environments provide a feeling of continuity, ownership, and responsibility, as well as a sense of identity and distinction.

3.3. Community Empowerment Tools

As Sager [40] argues, neoliberal policy trends have increasingly transformed urban areas into arenas for elite consumption and market-driven growth. This shift has led to the dominance of private developers in urban planning processes, often sidelining public-sector leadership and grassroots input. These dynamics are particularly relevant to our study, as they frame the structural challenges communities face in seeking meaningful participation in heritage-related and neighborhood-level planning. In such environments, cultural and social values may be subordinated to commercial interests, weakening the mechanisms through which local identity and resilience are cultivated. By examining how residents perceive their own roles and opportunities for influence within these systems, our study responds to this imbalance and explores avenues for re-centering civic voice in urban governance.

Brenner et al. [41] argues that the fragmentation of the city and the rise in uniform cityscapes are distinctly different and in line with a corporate vision as the outcome of all these processes. In this context, the dimension of social and cultural sustainability and the empowerment of communities for bottom-up actions and place-making become increasingly important. In order to understand the present-day state of research on the topic of community empowerment and the tools applied to achieve it, quantitative and qualitative analyses of the literature were performed.

The quantitative review of the literature on the topic of community empowerment tools was carried out in the Web of Science’s scientific literature database. The search using the keyword combination “community empowerment tools” provided 1520 search results. The graphical analysis is presented in Figure 3. The results are distributed in the period from 1992 to the present day. The trend of growth in the number of publications is evident, especially from 2019. For comparison, it is possible to note that in the period between 1992 and 2004, less than ten publications were published per year. Meanwhile, in 2019, 132 publications were published; in 2020, 132 were published; in 2021, 154 were published; in 2022, 177 were published; in 2022, 177 were published; in 2023, 177 were published; and in 2024, 109 publications were published. The majority of publications—1245—are journal articles. The following research areas have the highest number of publications on community empowerment tools: Public Environmental and Occupational Health (303 publications), Environmental Sciences and Ecology (138 publications), Healthcare Science Services (133 publications), Social Sciences and Other Topics (122 publications), and Educational Research (120 publications). The most relevant journals in research on the social resilience of neighborhoods are Sustainability, PLOS One, and Health Promotion International. The distribution of search results according to their relevance to UN sustainable development goals is the following: goal 03 Good Health And Well-Being: 703 publications, goal 04 Quality Education: 181, goal 01 No Poverty: 104, goal 11 Sustainable Cities And Communities: 96, goal 15 Life On Land: 71, goal 05 Gender Equality: 60, goal 10 Reduced Inequality: 51, goal 13 Climate Action: 43, goal 02 Zero Hunger: 42, goal 16 Peace And Justice Strong Institutions: 28, goal 09 Industry Innovation And Infrastructure: 27, goal 14 Life Below Water: 21, goal 07 Affordable And Clean Energy: 17, goal 06 Clean Water And Sanitation: 16, goal 12 Responsible Consumption And Production: 7, and goal 08 Decent Work And Economic Growth: 2. The most cited publication in the field of research on the social resilience of neighborhoods is from the field of medicine. However, the second most cited publication is directly related to the topic under analysis and focuses on stakeholders’ participation in environmental management [42].

It is acknowledged that community involvement is crucial to the long-term viability of urban environments and neighborhoods [43]. As Li and Hunter [43] note, though actual procedures are required for effective involvement and participation, community involvement was more frequently treated as a philosophical construct. It is critical to clarify what is meant by “community” and how it can participate in decision-making and have place-making authority. To begin with, a community is a geographically localized, mutually supporting social unit in which individuals identify as belonging to the community. A community’s common identity and interpersonal interactions can play a significant role in influencing decision-making. According to [43], the community can be broadly defined as a collection of stakeholder groups that share interests, such as local residents, businesses, government agencies, and pertinent institutions like universities and research non-profits. Figure 3 presents the graphical analysis using the VOSviewer (2024) software of the use of terms generated from the bibliometric results of search in the Web of Science’s scientific literature database using the keyword combination ‘community empowerment tools’. The graph demonstrates two main distinct clusters of the use of terms: one centered around general social, political, methodological, and spatial concepts and more relevant to social resilience in neighborhoods (red color) and the other around health-related terms (green color). This demonstrates the relevance and dominance of healthcare topics in community empowerment research. However, it is important to note that closer integration of healthcare research with factors of spatial environment is crucial in the context of community empowerment.

Different fields have given different definitions of empowerment. Interpretations of community empowerment, according to Laverack and Wallerstein [44], depend on whether the concept is understood as a process or an outcome and whether it exists as an interpersonal phenomenon, a broad socio-political context, or an interaction of change at multiple levels. They also stress the significance of examining the many organizational dimensions of community empowerment and how these affect the concept’s efficacy and application in any program (such as public health, historical preservation, or urban planning). Nine organizational domains of influence on community empowerment within a program context were identified by Laverack and Wallerstein [44]: (i) participation; (ii) leadership; (iii) problem assessment; (iv) organizational structures; (v) the mobilization of resources; (vi) connections with others; (vii) “asking why”; (viii) program management; and (ix) the role of external agents. Ahmad and Abu Talib [45] support that community participation in developmental processes promotes social influence on developmental actors and is regarded as a means of enhancing local communities’ capacity. According to [45], communities are deemed empowered if they have the ability and resources to address unmet needs, participate in decision-making processes, and have access to timely and clear information.

Community empowerment tools are mechanisms that enable residents to influence and actively participate in the physical transformation of their local environment, including infrastructure and public space development. By examining how different empowerment approaches facilitate community-driven urban transformations, it is possible to obtain essential insights into practical strategies that promote inclusive governance and local capacity-building, which are central to fostering resilient and sustainable communities. These tools often include participatory planning processes, where community members are directly involved in decision-making related to urban design, infrastructure projects, and neighborhood revitalization efforts. One key aspect is providing communities with the resources, knowledge, and platforms to voice their needs and preferences, thereby ensuring that physical changes reflect local priorities. Empowerment is a constant and continuing process rather than a static, one-time event [45]. Empowerment tools like participatory budgeting, citizen advisory councils, digital platforms [46], participatory mapping activities [47], interactive online maps [21], etc., for community feedback can foster greater transparency and accountability in urban development. Empowering communities also involves building capacity through education and training, thereby equipping residents with the skills to engage effectively in these processes. When communities have control over aspects of their environment, they are more likely to advocate for sustainable, inclusive, and context-sensitive urban transformations. Ultimately, these tools promote a sense of ownership and agency, leading to more resilient and vibrant neighborhoods.

3.4. Strengthening Social Resilience in Urban Neighborhoods

Over recent decades, significant paradigm shifts have rapidly surpassed countries’ ability to effectively address growing societal pressures and uncertainties. Populations have faced challenges such as economic instability, the escalating climate crisis, environmental extremes, urbanization, migration surges, and the swift pace of technological advancements. Amid these pressures, societies across the globe have experienced increased polarization and fragmentation. Gaps in generational perspectives, income, and education continue to widen, while political and ideological polarization, along with the rise in extremism, has concurrently intensified [48]. In this context, reviewing existing strategies and challenges associated with strengthening social resilience in urban neighborhoods highlights the significance of adaptive policies, civic engagement, and inclusive practices as essential mechanisms for achieving sustainable and resilient urban communities.

A quantitative review of the literature on the topic of social resilience in neighborhoods under conditions of uncertainty was carried out on the Web of Science’s scientific literature database. The search using the keyword combination “social resilience in neighborhoods under uncertainty” provided three search results only. The combination of keywords refined to “strengthening social resilience in neighborhoods” provided 81 results. The graphical analysis is presented in Figure 4. The results of the search “strengthening social resilience in neighborhoods” are distributed in the period between 1998 and the present day. A slight increase in the number of publications is visible from 2021. The majority of publications—75—are journal articles. The following research areas have the highest number of publications on strengthening social resilience in neighborhoods: Environmental Sciences and Ecology (12 publications); Public Environmental and Occupational Health (12 publications); Science, Technology, and Other Topics (12 publications); and Water Resources (12 publications). The most relevant journals in research on strengthening the social resilience of neighborhoods are the International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction and Sustainability. The distribution search results according to their relevance to UN sustainable development goals is the following: goal 03 Good Health And Well-Being: 26 publications, goal 13 Climate Action: 19, goal 11 Sustainable Cities And Communities: 12, goal 16 Peace And Justice Strong Institutions: 5, goal 05 Gender Equality: 4, goal 10 Reduced Inequality: 3, goal 02 Zero Hunger: 2, goal 07 Affordable And Clean Energy: 2, goal 01 No Poverty: 1, and goal 09 Industry Innovation And Infrastructure: 1 publication. The most cited publications in the field of research on strengthening the social resilience of neighborhoods are focused on racism [49] and urban resilience [50].

Researchers underline the specific context in which the challenges of social resilience must be addressed. The world of today is fragile, anxious, nonlinear, and incomprehensible, as described by Mahadevan [51] in the BANI environment (Brittle, Anxious, Nonlinear, and Incomprehensible). The previous VUCA (Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, and Ambiguous) paradigm is being replaced by this new era, which emphasizes the necessity of a new management and leadership style. For example, the recent pandemic has raised additional questions and challenges in the field of strengthening social resilience [52]. The ability of social entities—whether they are people, organizations, or communities—to withstand, assimilate, manage, and adapt to a variety of environmental and social risks is the focus of all definitions of social resilience [2]. Existing research highlights the importance of fostering strong social connections and networks [53], community solidarity [54], and inclusive governance [55] to enhance resilience. Figure 4 demonstrates the graphical analysis using the VOSviewer (2024) software of the use of terms generated from the bibliometric results of search in the Web of Science’s scientific literature database using the keyword combination ‘strengthening social resilience in neighborhoods’. The graph demonstrates the close integration of three clusters of the use of terms centered around spatial concepts, such as place and city (red color), theory-based research concepts (blue color), and social–demographic terms (green color), suggesting that a balanced interdisciplinary approach is currently emerging in studies focusing on strengthening social resilience in urban neighborhoods.

However, there is a notable gap in understanding how to systematically build these capacities in urban contexts that are continually evolving. One challenge lies in addressing socioeconomic inequalities [56], which often undermine collective resilience efforts by disproportionately affecting vulnerable populations. Additionally, research is still developing around strategies to sustain long-term resilience in the face of rapid urbanization, gentrification, and climate change [57]. More studies are needed to explore how urban policies, participatory frameworks, and infrastructure investments can be designed to not only respond to crises but also proactively build resilience in ways that are adaptable to ongoing changes and uncertainty. This highlights the need for a more dynamic and flexible approach to resilience building in urban neighborhoods. The research gap identified after the literature analysis reveals the lack of systematic approaches that integrate adaptive urban policies, participatory governance, and community-driven initiatives specifically adapted to urban neighborhoods. Addressing this gap is directly aligned with the research aim of understanding how these dimensions collectively benefit social resilience and sustainability at the neighborhood scale.

4. Questionaries’ Survey Results

The results presented in this section reflect the findings of a national level case study conducted in Lithuania. While the broader research project was designed with a pan-European scope, the data analyzed here were collected solely from Lithuanian respondents during the first phase of the study. As such, the findings offer insights into resilience, heritage perception, and participatory governance within the specific social, institutional, and planning contexts of Lithuania. At the next step, broader European research is planned.

4.1. Profiles of the Respondents

Ninety respondents from Lithuania participated in the survey. The subsequent phase involves analyzing an international survey using the same questionnaire to examine and compare the profiles of various European countries.

The survey results presented in Table 1 provide a detailed demographic and socioeconomic profile of the respondents. The majority of the participants are young, with 34.4% falling within the 18–24 age range, followed by a significant segment in the 45–54 age group, comprising 27.8%. The gender distribution shows a predominant female participation rate of 65.6%, compared to 34.4% for male respondents.

Table 1.

Profiles of the respondents.

Educationally, the respondents display a high level of academic achievement, with 32.2% holding a master’s degree and 26.7% having a doctorate (Ph.D.).

Professionally, 40% of respondents identify as students, which aligns with the younger demographic profile, while 15.6% work as practicing architects or urban planners, and another 15.6% fall into the ‘Other’ category, suggesting a variety of occupations. Community members and developers/investors make up 23.3% and 4.4% of the respondents, respectively.

In terms of living arrangements, the vast majority of respondents (72.2%) reside in cities, with fewer living in suburbs (15.6%) and villages (12.2%). Regarding their residences, 56.7% own a house, 28.9% live in owned flats, and 12.2% are in rented flats.

Overall, these results depict a young, highly educated cohort predominantly living in urban settings, engaged in a variety of professional roles, and with a significant involvement in community and development activities.

4.2. The Built Environment and Heritage Aspects for Local Identity and Civic Engagement

The survey results reveal a subtle understanding of the accessibility and environmental quality of neighborhoods, as well as residents’ involvement in sustainability, perceptions of cultural heritage, inclusivity, and the presence of significant cultural symbols.

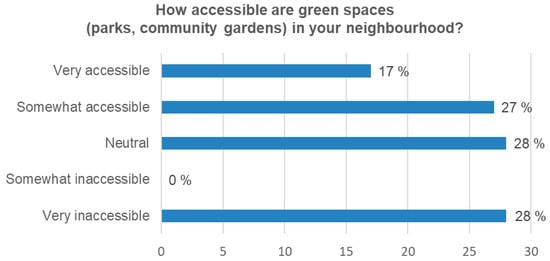

The findings indicate a varied perception of the built environment, with accessibility to green spaces being a crucial component of social and ecological resilience and is seen as moderately positive. While 55% of respondents rated access to green spaces as either “very accessible” or “somewhat accessible”, nearly a third (28%) remained neutral, and 17% reported it as inaccessible (Figure 5). This deviation points to potential spatial inequalities or an unbalanced distribution of green facilities within urban neighborhoods. Such gaps can directly impact residents’ well-being and the opportunities for community interactions, which are foundational to civic cohesion and resilience-building. The neutral responses also suggest a possible normalization of limited access. Residents may not perceive bordering availability as problematic due to adjusted expectations or a lack of alternatives.

Figure 5.

Accessibility of green spaces.

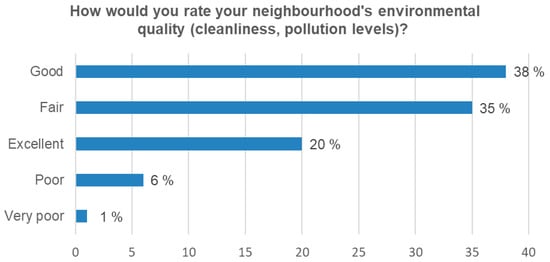

The environmental quality of neighborhoods is generally rated positively (Figure 6), with 38% of respondents considering it good and 35% rating it as fair. A smaller percentage (20%) of respondents rate it as excellent, while only a few find it poor (6%) or very poor (1%).

Figure 6.

Neighborhoods’ environmental quality.

Respondents were asked to answer a question: “Are you involved in any sustainable practices (e.g., recycling, composting, urban gardening) in your neighbourhood?”. The results show that a majority (37.8%) of participants are actively involved, with an additional 33.3% somewhat involved. Notably, even among those not currently participating, 16.7% expressed interest, while only 12.2% indicated no interest. These findings suggest a generally positive orientation toward sustainable living, which may reflect both environmental values and a willingness to engage in collective action. While this form of engagement often occurs at the individual or household level, it reflects a broader readiness for participation and a potential foundation for community-led resilience initiatives, particularly in contexts where formal participatory mechanisms are limited or underutilized.

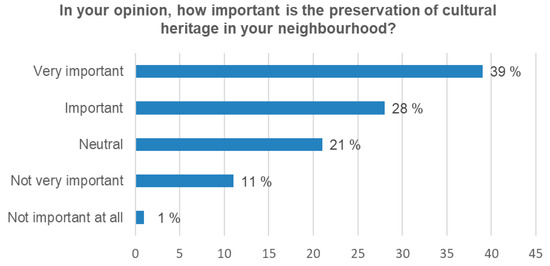

The recognition of cultural heritage as important or very important by 67% (Figure 7) of respondents confirms its perceived value as a key component of community identity. However, as later data show, this strong valuation does not translate into corresponding civic engagement or preservation activity. This gap highlights a latent appreciation of heritage that remains inactivated through limited meaningful involvement opportunities. The findings suggest that current governance models may be failing to channel emotional and cultural attachment into practical co-management or adaptive reuse projects, a concern echoed in the literature on historic urban landscapes and the need for participatory heritage governance.

Figure 7.

Importance of preservation of cultural heritage.

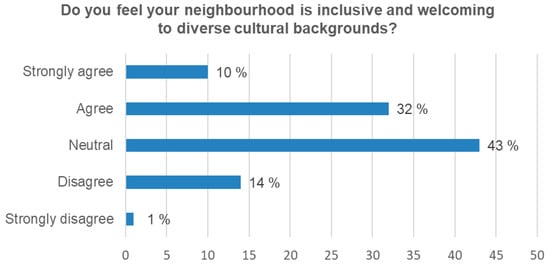

Responses show a moderately positive perception of inclusivity, with 42% agreeing and 10% strongly agreeing that their neighborhood is welcoming to diverse cultures (Figure 8). However, 43% remain neutral, and a small percentage disagree (14%) or strongly disagree (1%).

Figure 8.

Inclusivity and diversity of cultural backgrounds in neighborhoods.

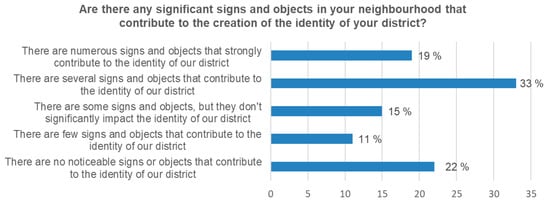

The fact that over half of the respondents recognize meaningful local symbols, such as parks, architectural elements, and sculptures, confirms the presence of physical objects that serve as identity markers within neighborhoods. However, the 22% who report no noticeable signs of local identity point to potential spatial or cultural marginalization (Figure 9). This contrast raises critical questions about the visibility, accessibility, and inclusivity of symbolic heritage: who defines what is “significant,” and whose stories are represented? Bridging this gap requires more participatory processes in defining and narrating heritage, especially in diverse or post-industrial contexts where traditional landmarks may be contested or underutilized.

Figure 9.

Significant signs and objects contributing to neighborhood identity.

Respondents who indicated that specific features contribute to their neighborhood’s identity were invited to answer an open-ended question about the objects that they consider most meaningful. The responses provide insights into the tangible and symbolic elements that shape local identity in the Lithuanian context.

The most frequently mentioned objects include the following:

- Parks, which were referenced 10 times.

- Buildings, which were referenced 6 times.

- Wooden architecture, which were referenced 3 times.

- Sculptures, which were referenced 3 times.

- Heritage, which were referenced 3 times.

- Fortresses, which were referenced 3 times.

These findings highlight the importance of both natural and built elements in forming a sense of place and shared identity. Parks and wooden architecture, in particular, represent a connection to the local history and landscape, while references to sculptures and fortresses suggest that symbolic landmarks and cultural memory play a vital role in residents’ perceptions of belonging. This supports the study’s aim to assess how heritage and identity function as components of neighborhood resilience and community engagement.

4.3. Community Empowerment Tools

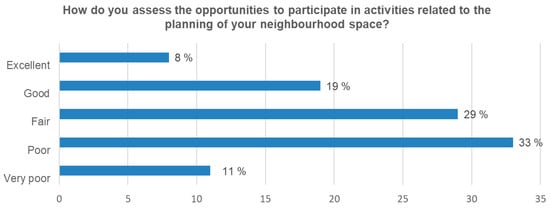

The survey results reveal a significant perceived shortage in participatory opportunities, with nearly half of the respondents (44%) rating their ability to engage in neighborhood planning as poor or very poor (Figure 10). This perception is critical, given that civic engagement and bottom-up planning are widely recognized as pillars of community resilience. The relatively low percentage of respondents who rated opportunities as excellent (8%) suggests that even among the most civically optimistic, access to meaningful participation is rare. These findings reflect a potential disconnect between institutional rhetoric and practical accessibility, echoing critiques in the literature that tokenistic participation often replaces genuine empowerment.

Figure 10.

Opportunities to participate in neighborhood planning.

Respondents were asked to answer the following question: “Do you participate in activities related to the planning of your neighbourhood space?”. Only 16.7% of respondents actively participate in activities related to neighborhood planning, indicating a significant gap between the availability of participatory opportunities and actual engagement.

The low engagement rate (16.7%) in neighborhood planning activities, despite respondents’ high educational attainment and recognition of cultural heritage (67% rating it as important or very important), indicates a structural disconnect. This suggests that factors beyond individual willingness, such as ineffective communication channels, a lack of inclusive mechanisms, or institutional barriers, may inhibit community involvement.

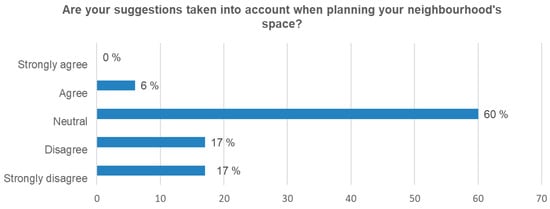

Most respondents feel neutral if their suggestions are taken into account (60%), with 17% disagreeing and 17% strongly disagreeing that their ideas are considered during planning (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Suggestions of respondents considered during the planning of neighborhood spaces.

The municipality was perceived as the most active stakeholder in neighborhood planning (45% strongly agreed), while civil society and the business sector were seen as significantly less engaged (Table 2). This stakeholder imbalance reveals a top-down governance structure, where institutional actors dominate the urban agenda, while public and private actors remain marginal. Such an arrangement may limit the diversity of perspectives in planning processes and reduce opportunities for community-led initiatives. Furthermore, if the municipality is seen as the sole actor, failures in responsiveness or transparency could compound frustration and deepen civic disengagement, particularly in underrepresented or marginalized communities.

Table 2.

Entities engaged in the planning of neighborhood spaces.

4.4. Strengthening Social Resilience in Urban Neighborhoods

Survey responses reveal that civil society is perceived as the most significant contributor to residents’ satisfaction with their neighborhood, followed by the municipality and the business sector (Table 3). Notably, civil society garnered the highest number of “agree” responses (49), compared to the municipality (38) and the business sector (21). This suggests that community-based organizations and informal civic actors play a key role in promoting social resilience through everyday interactions, localized support, and public initiatives. However, the predominance of neutral responses signals a persistent uncertainty or indifference about the actual impact of these entities. These neutral perceptions may reflect a lack of visibility or communication regarding their contributions or suggest that efforts are fragmented or inconsistently experienced across neighborhoods.

Table 3.

Entities contributing to the level of satisfaction with life at participants’ current place of residence.

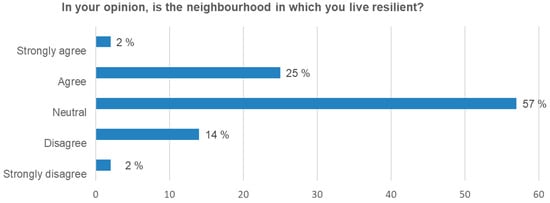

Respondents’ perspectives on neighborhood resilience further emphasize this uncertainty. A majority (57%) responded neutrally when asked about their neighborhood’s resilience (Figure 12), while only 2% strongly agreed, and another 2% strongly disagreed. Such widespread neutrality indicates a lack of clarity or confidence in local adaptive capacity. This could stem from a limited public understanding of what “resilience” entails at the neighborhood scale or from the absence of visible, participatory initiatives that would otherwise signal resilience in action. The data may also reflect a perception that resilience is a top-down construct largely handled by institutions rather than co-produced with the community.

Figure 12.

Resilience of neighborhood.

These results underline a disconnect between formal participatory mechanisms and perceived outcomes. While the roles of institutional and civil society actors are acknowledged, their tangible impact on community satisfaction and empowerment appears limited. This finding aligns with broader concerns in Urban Studies that participation without perceived influence leads to apathy or disengagement. To strengthen social resilience, planning processes must be reframed to not only include diverse actors but also demonstrate responsiveness to public input. Co-creating resilience strategies with residents through transparent communication, shared decision-making, and inclusive feedback loops would help shift perceptions from neutrality to trust and from passive observation to active stewardship.

5. Discussion

This section synthesizes findings from the literature review and the empirical case study in Lithuania to reflect on how urban resilience, cultural heritage, and participatory governance interact in shaping neighborhood-level sustainability. The Lithuanian case, while specific, offers transferable lessons for other contexts where governance reforms, heritage contestation, and civic engagement are actively evolving.

To guide this interpretation, the discussion is structured around three thematic dimensions that correspond to the research questions introduced earlier:

- (1)

- Adaptive policy frameworks and their ability to support long-term resilience;

- (2)

- Participatory governance tools and the extent to which they enable meaningful civic engagement;

- (3)

- Community identity and heritage values as foundations for localized resilience.

Each of the following subsections addresses one of these dimensions by linking the empirical findings with theoretical insights from the literature, allowing for a critical reflection on the implications of the Lithuanian case study for resilience building in similar urban contexts.

5.1. Potentials and Barriers to Social Resilience in Neighborhoods

This topic addresses Research Question 1 by exploring how adaptive policy frameworks function in practice. In the Lithuanian context, municipalities frequently approach resilience through the lens of infrastructure and environmental planning, particularly green spaces. While such strategies align with international sustainability goals, survey responses indicate that many residents perceive themselves as having limited inclusion in local decision-making processes. This suggests a disconnect between formal resilience strategies and their responsiveness to community realities.

Adaptive governance in this context must extend beyond static plans to incorporate flexible, participatory mechanisms that evolve in response to community needs. Barriers, including limited communication, procedural opacity, and a lack of institutional responsiveness, hinder the ability of policy frameworks to fully support long-term, socially rooted resilience.

The literature identifies key steps to overcome barriers to social resilience in neighborhoods: strengthening social networks, promoting inclusive urban policies, enhancing civic engagement, investing in quality infrastructure and public spaces, fostering collaboration, education, and addressing inequalities and segregation. Strengthening social networks through community events, neighborhood associations, workshops, and online platforms enhances communication and collaboration [21,22], supporting collective well-being and place-making during crises [21]. Survey data support this, showing that respondents value green spaces and cultural heritage preservation, which enhance connections and contribute to stronger neighborhood identities.

Inclusive urban policies that ensure spatial justice and equitable access to resources and decision-making [58,59] are vital for reducing inequalities and fostering stable, cohesive communities. Respondents’ feedback highlights concerns about limited participatory opportunities, with 50% perceiving their suggestions as ignored or inadequately addressed. This emphasizes the need for transparent and inclusive urban governance that prioritizes marginalized voices.

Civic engagement, through forums, workshops, participatory budgeting, and volunteer programs, builds ownership and responsibility among residents, enhancing neighborhood resilience [21,22]. However, survey results indicate that only 16.7% actively engage in such activities, signaling a critical gap in the practical implementation of engagement initiatives.

Access to essential services like education, healthcare, transportation, and housing reduces inequalities and creates supportive environments. Survey respondents rated their neighborhood’s environmental quality positively, though 28% noted accessibility issues with green spaces, reinforcing the need for equitable urban planning. High-quality public spaces, such as parks and plazas, encourage social interaction and resilience, contributing to biophilic and climate-adaptive neighborhoods [60].

Education and capacity-building initiatives, including conflict resolution, leadership, and heritage preservation, empower residents to contribute to community well-being. Survey insights reflect a need for better integration of educational programs into urban strategies to ensure that residents are equipped to actively participate in planning processes. Collaboration among governments, organizations, and residents fosters co-creation, transparency, and accountability in urban governance, factors essential for sustainable development [21,22,61]. Addressing spatial and socioeconomic segregation through diverse, mixed-use urban planning is critical for fostering social cohesion and reducing the adverse effects of segregation, as evidenced by survey findings highlighting disparities in participatory mechanisms and access to resources.

5.2. Community Empowerment Tools

This topic directly relates to Research Question 2, which focuses on participatory governance tools and their impact on civic engagement. The findings show that while institutional mechanisms for participation exist, their perceived effectiveness is mixed. Many respondents view themselves as active contributors, organizers, advisors, or supporters, but they also report feeling marginalized in formal decision-making processes.

Empowerment in this setting arises not only from structured participation but also from informal, public initiatives that reflect community agency. These findings support the argument that building resilient communities requires more than top-down inclusion. It necessitates recognition and support of everyday civic practices and networks.

The analysis of the literature suggests several steps for community empowerment in urban planning, including participatory planning frameworks, participatory budgeting, digital platforms for community input, public workshops, and forums. Participatory planning frameworks, as formal processes, enable residents to contribute to decisions on urban planning and infrastructure [62]. These frameworks foster a sense of ownership and empowerment by ensuring that community voices are considered in environmental changes. Survey data align with this, indicating limited participation opportunities, which highlights the need for inclusive frameworks.

Participatory budgeting grants residents direct control over allocating public funds for local projects [63]. This process enhances transparency and accountability while allowing communities to prioritize improvements. Survey findings suggest a demand for greater transparency in public spending, which participatory budgeting could address.

Digital platforms for community input make engagement more accessible by enabling feedback, voting on proposals, and idea sharing [9]. These tools simplify participation and expand opportunities for residents to shape their environment. Respondents expressed interest in more accessible and transparent participatory mechanisms, which digital platforms can support.

Community workshops and forums encourage discussions about upcoming projects and foster collaboration between residents and authorities. Such meetings build transparency and accountability, aligning with respondents’ feedback that highlights the importance of stronger community–local authority collaboration.

Education and capacity-building programs equip residents with skills in urban planning, design, and advocacy, enabling meaningful engagement in development discussions. Survey insights show a need for such programs to empower residents in participatory processes. Community advisory councils, representing diverse groups, ensure local needs are addressed and promote inclusivity [64]. Strengthening these councils aligns with the survey’s call for more inclusive decision-making.

Partnerships with NGOs, community groups, and urban experts provide technical support and resources for bottom-up initiatives. These partnerships bridge gaps between community needs and government resources, enabling sustainable development. Equitable participation remains critical, thereby ensuring that marginalized groups are included in decision-making. Survey responses emphasize this need for inclusivity to achieve fair and sustainable development outcomes.

5.3. The Built Environment and Heritage Aspects for Local Identity and Civic Engagement

This topic addresses Research Question 3. This subsection examines the role of cultural heritage and the built environment in shaping neighborhood identity and resilience. Respondents frequently mentioned parks, wooden architecture, sculptures, and other symbolic features as integral to their sense of place. These elements serve not only as physical assets but also as emotional anchors, reinforcing a sense of continuity and belonging.

Such attachments illustrate how resilience is deeply embedded in localized cultural and historical contexts. The recognition of heritage values in planning processes can thus strengthen not just the esthetic or functional qualities of urban space but also civic engagement and identity-based investment in the community.

Promoting heritage conservation is essential to addressing challenges related to the built environment and heritage. Implementing policies to protect historical landmarks and traditional architecture ensures that these elements remain integral to the community and preserve local identity [39,65]. Survey findings reinforce this, with respondents emphasizing the significance of cultural heritage in fostering neighborhood identity.

Community involvement in urban planning is another key step. Including residents in decision-making fosters ownership and pride [39,65], aligning with survey data indicating limited engagement opportunities, where only 16.7% of respondents actively participate.

Educational programs, workshops, and exhibitions can deepen appreciation for heritage, fostering pride and responsibility for preservation. Survey insights suggest that these programs should address barriers such as accessibility and inclusivity to engage all community members. Events like community-driven festivals and heritage days strengthen civic engagement through shared cultural experiences.

Designing accessible public spaces that reflect local history and culture is crucial. Creating plazas, parks, and cultural centers fosters social interaction and a sense of belonging. The adaptive reuse of heritage buildings can balance preservation with modern needs, contributing to community identity and resilience [66]. Survey responses highlight the importance of underused historic buildings as community assets.

Collaboration between governments, heritage bodies, and community organizations is vital for sustainable heritage preservation. These partnerships ensure that both local identity remains a priority and community needs are integrated into development projects [67]. Such collaborative approaches align with respondents’ desires for transparent, inclusive urban governance and culturally sensitive development.

5.4. Strengthening Social Resilience in Urban Neighborhoods

This final subsection integrates insights from all three research questions to reflect on how community-level resilience can be cultivated in urban neighborhoods. The Lithuanian case demonstrates that resilience is not merely a technical or managerial issue; it is a socially constructed process that depends on policy flexibility, meaningful participation, and deep-rooted place attachment.

Together, these findings point to a layered model of resilience, where institutional frameworks provide structure; community empowerment drives engagement; and cultural identity offers cohesion and continuity. Strengthening urban resilience, therefore, requires a balance between governance systems and lived experiences rooted in local values.

To strengthen social resilience in urban neighborhoods, adaptive urban policies are essential. These policies must be flexible and responsive to emerging crises, such as economic downturns or climate-related events, thereby ensuring that communities can adapt effectively to changing circumstances. Investing in resilient infrastructure, such as multifunctional public spaces and green infrastructure, can help neighborhoods withstand environmental and social stressors. Programs like urban gardening also positively impact social sustainability by fostering community interaction and environmental adaptation [68].

Participatory governance plays a critical role in resilience building [55]. Mechanisms that enable residents to participate in decision-making ensure that diverse perspectives are included, leading to effective and inclusive solutions. Survey results highlight the need for greater resident engagement, with many respondents indicating limited opportunities for meaningful participation.

Addressing inequalities through equitable urban planning strengthens collective resilience by improving access to resources, housing, and services for marginalized groups. Survey data underscore the importance of inclusivity, with respondents emphasizing the need for better access to resources and decision-making processes.

Collaboration among stakeholders, including governments, local organizations, academic institutions, and the private sector, fosters coordinated approaches to resilience. Partnerships pool resources and expertise, enabling sustainable and effective solutions to urban challenges. Survey insights reveal a need for stronger collaboration to address residents’ concerns.

Fostering social capital through trust, solidarity, and mutual aid is vital for social resilience [53]. Community centers, associations, and social events can strengthen bonds and enhance social cohesion. Survey respondents value community initiatives that build connections and mutual support.

Community education and awareness are also crucial. Training and resources that empower residents with knowledge of resilience-building strategies enable them to contribute actively to their community’s preparedness and adaptability. Survey data indicate a demand for educational initiatives to enhance local resilience efforts.

Supporting local economic development through cooperatives, entrepreneurship programs, and heritage-related activities improves financial stability and reduces vulnerability to economic shocks [39,65]. Economic diversification and community-driven initiatives can create more resilient neighborhoods, a sentiment echoed by respondents, highlighting the importance of economic opportunities within their communities.

6. Conclusions