A Study on the Relationship Between Rural E-Commerce Development and Farmers’ Income Growth

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Rural E-Commerce

2.2. Rural E-Commerce Development Models

2.3. Influencing Factors of Rural E-Commerce Development

2.4. The Relationship Between Rural E-Commerce and Farmer Income Growth

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Literature Research Method

3.2. Empirical Analysis Method

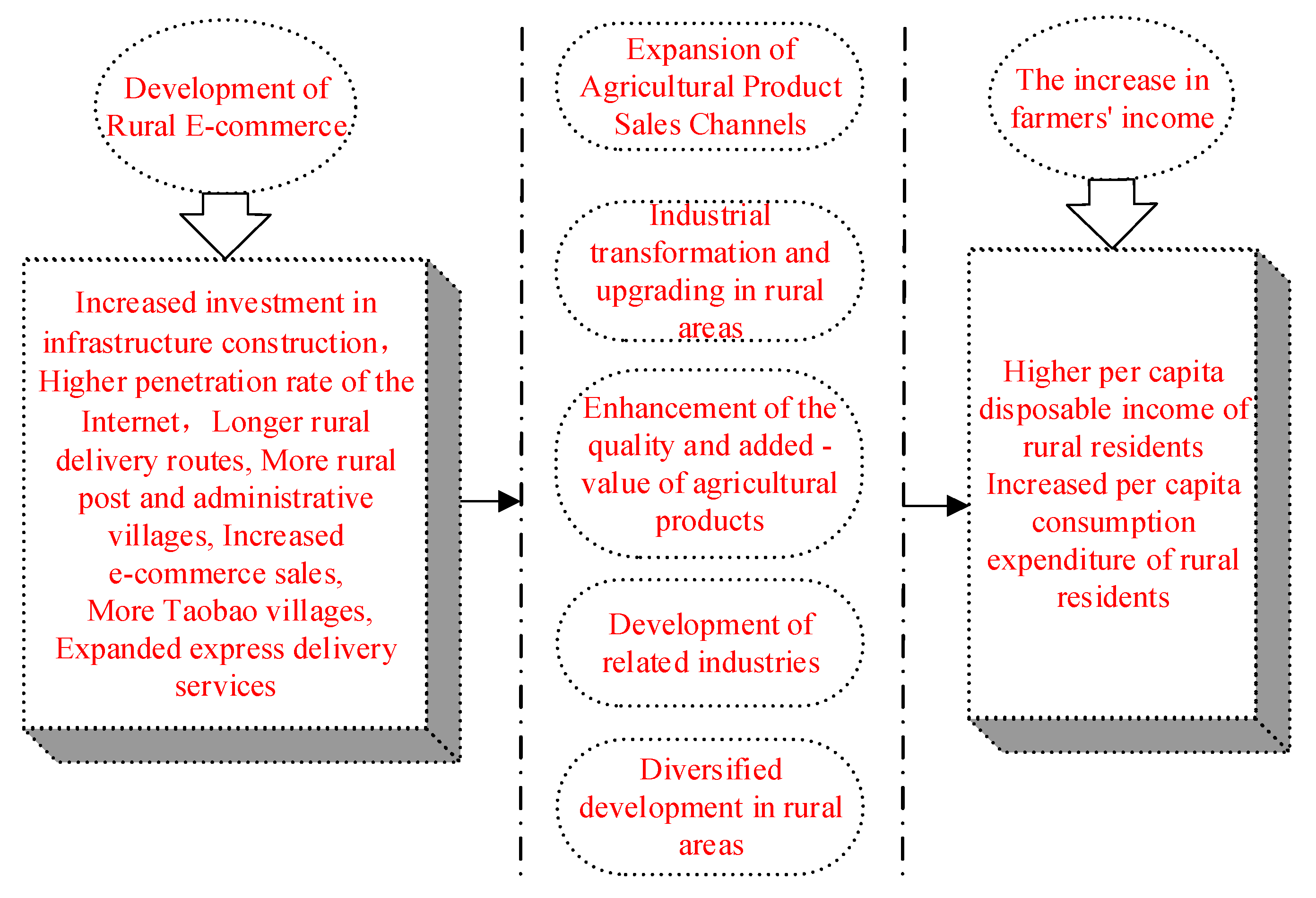

4. Analysis of the Influencing Mechanism and Research Hypotheses

5. Model Specification and Variable Definitions

5.1. Model Specification

5.2. Variable Definitions

6. Data Description and Descriptive Statistics

7. Empirical and Regression Result Analysis

7.1. Benchmark Regression Analysis

7.1.1. Harris–Tzavalis (HT) Unit Root Test (for Data Stationarity Test)

7.1.2. Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) Test for Multicollinearity

7.1.3. F-Test

7.1.4. Hausman Test

7.1.5. Fixed-Effect Regression Analysis

7.2. Heterogeneity Analysis

- (1)

- Effective leveraging of unique agricultural endowments (premium rice, soybeans, wild fungi, and mountain herbs) through specialized e-commerce platforms;

- (2)

- Emergence of complementary industries including cold-chain logistics, packaging services, live-stream commerce, and influencer-driven rural tourism.

- Targeted infrastructure investments improving last-mile connectivity and reducing rural–urban digital divides;

- Reverse migration of skilled labor enhancing local e-commerce capabilities;

- Innovative marketing paradigms (fieldside live-streaming, geo-tagged specialty products) overcoming traditional distribution bottlenecks.

- Declining marginal utility of additional platform penetration;

- Intensified competition eroding seller profit margins;

- Market saturation in high-value agricultural segments.

7.3. Robustness Analysis

7.3.1. Overall Robustness Analysis

7.3.2. Regional Robustness Analysis

8. Conclusions and Recommendations

8.1. Conclusions

8.1.1. Regional Disparities in Rural E-Commerce Development

8.1.2. Income Enhancement Effects of Rural E-Commerce

8.1.3. Regional Heterogeneity Mechanisms

8.2. Recommendations

8.2.1. Formulate Differentiated Policies for Rural E-Commerce Development

8.2.2. Innovate E-Commerce Application Scenarios

8.2.3. Promote Digital Empowerment of Rural E-Commerce Development Promptly

8.2.4. Build Rural E-Commerce Human Capital

9. Research Limitations and Future Prospects

9.1. Research Limitations

9.1.1. Data Collection and Processing

9.1.2. Selection of Evaluation Indicators

9.1.3. Empirical Analysis

9.2. Research Prospects

9.2.1. Expanding Data Dimensions

9.2.2. Optimizing Models and Indicator Systems

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- People’s Daily. Rural E-Commerce to Make Up for the Short Board of “Agriculture, Rural Area and Farmer” (Rolling News). Available online: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2017-01/19/content_5161094.htm (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Bai, Q.P. Building a solid foundation for digital rural development. Econ. Dly. 2024, 5, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y. China’s agricultural and rural economy maintains sound momentum in Q1. Rural Sci. Technol. 2024, 15, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.X. Research on the Development Level of Rural E-Commerce in China Based on Analytic Hierarchy and Systematic Clustering Method. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R. Digital economy empowers China’s rural revitalization: Current situations, problems and recommendations. Asian Agric. Res. 2021, 13, 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu, S.; Suzuki, A. The Impact of Rural e-Commerce Development on Rural Income and Urban-Rural Income Inequality in China: A Panel Data Analysis. 2021. Available online: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/315050/files/0-0_Paper_18545_handout_25_0.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Grandon, E.E.; Pearson, J.M. Electronic commerce adoption: An empirical study of small and medium US businesses. Inf. Manag. 2004, 42, 197–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, J.M.; Dumbre, G.M. Basic Concept of E-Commerce. Int. Res. J. Multidiscipl. Stud. 2017, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, V.; Malviya, B.; Arya, S. An Overview of Electronic Commerce (e-Commerce). J. Contemp. Issues Bus. Govt. 2021, 27, 666. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, S. Developing Rural E-commerce: Trends and Challenges. Mekong Institute. Briefing Paper, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- An, L.L. Research on the measurement of rural e-commerce development level and its influencing factors. Shanxi Agric. Econ. 2018, 63–64. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, F.; Li, J. Research on the Development Mechanism of Rural E-Commerce Based on Rooted Theory: A Co-Benefit-Oriented Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S.E.; Nieschwietz, R.J. A Web assurance services model of trust for B2C e-commerce. International. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2003, 4, 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, E. Types of B2B E-Business Model Commonly Used: An Empirical Study On Australian Agribusiness Firms. Australas. Agribus. Rev. 2005, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, W. A knowledge-based intelligent electronic commerce system for selling agricultural products. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2007, 57, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalali, A.A.; Okhovvat, M.R.; Okhovvat, M. A new applicable model of Iran rural e-commerce development. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 3, 1157–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, T.; Pedrosa, I.; Bernardino, J. Business Intelligence for E-commerce: Survey and Research Directions. In Recent Advances in Information Systems and Technologies; Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 22. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, M.; Grondys, K.; Hajiyev, N.; Zhukov, P. Improving the E-Commerce Business Model in a Sustainable Environment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, T.; Pick, J.B.; Sarkar, A. Japans prefectural digital divide: A multivariate and spatial analysis. Telecommun. Policy 2014, 38, 992–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahayu, R.; Day, J. Determinant factors of e-commerce adoption by SMEs in developing country: Evidence from Indonesia. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 195, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Vakharia, A.J.; Tan, Y.; Xu, Y. Marketplace, Reseller, or Hybrid: Strategic Analysis of an Emerging E-Commerce Model. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2018, 27, 1595–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, A.; Gupta, S. Challenges Assessment for the E-Commerce Industry in India: A Review (With Special Reference to Flipkart V/S Snapdeal). Glob. Inf. Manag. 2017, 25, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, J.A.; Londoño-Pineda, A.; Rodas, C. Sustainable logistics for e-commerce: A literature review and bibliometric analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zennaro, I.; Finco, S.; Calzavara, M.; Persona, A. Implementing E-commerce from logistic perspective: Literature review and methodological framework. Sustainability 2022, 14, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, N.; Chen, H. Comprehensive evaluation and obstacle factor analysis of high-quality development of rural E-commerce in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z. A Study on the Willingness and Factors Influencing the Digital Upgrade of Rural E-Commerce. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raoul, E.; Marianne, M. The Development of E-Commerce in Cameroon. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2020, 10, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popenkova, D.K.; Nikishin, A.F. Prospective directions of e-commerce development. J. Adv. Res. Law Econ. 2020, 11, 1337–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, R. The Digital Provide: Information (Technology), Market Performance, and Welfare in the South Indian Fisheries Sector. Quart. J. Econ. 2007, 122, 879–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, A. Information Technology and Rural Market Performance in Central India; University of Maryland: College Park, MD, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Aker, J.C. Information from Markets Near and Far: Mobile Phones and Agricultural Markets in Niger. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 2010, 2, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtois, P.; Subervie, J. Farmer Bargaining Power and Market Information Services. Am. Agric. Econ. 2015, 97, 953–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimamoto, D.; Yamada, H.; Gummert, M. Mobile phones and market information: Evidence from rural Cambodia. Food Policy 2015, 57, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaka, S.S. Impact of growing e-commerce on Indian farmers. Indian. J. Econ. Dev. 2017, 13, 596–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, M.H.; Alomari, M.A.; Latiff NA, A.; Alomari, M.S. Effect of e-commerce platforms towards increasing merchant’s income in Malaysia. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. (IJACSA) 2019, 10, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Ping, Y.; Chen, X.; Yang, H.; Liu, W.; Lu, W.; Yu, L.; Zhang, G. An online agricultural product transaction system. N. Z. J. Agric. Res. 2010, 50, 1045–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Ni, Y.; Zhu, F.; Han, J. Empirical Analysis on the Impact of Poverty Alleviation by Rural E-Commerce on Farmers’ Income. Asian J. Agric. Ext. Econ. Sociol. 2019, 32, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Zhu, J. Informality and rural industry: Rethinking the impacts of E-Commerce on rural development in China. Rural. Stud. 2020, 75, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Zhang, X.; Feng, M. Exploring the Income-Increasing Benefits of Rural E-Commerce in China: Implications for the Sustainable Development of Farmers. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; He, L.; Hu, Z. Impact of Rural E-Commerce on Farmers’ Income and Income Gap. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Min, S.; Ma, W.; Liu, T. The adoption and impact of E-commerce in rural China: Application of an endogenous switching regression model. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 83, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Li, J.; Feng, Z. Impact Factors of Rural E-commerce Products Diversification. Sci. J. Econ. Manag. Res. 2021, 3, 212–219. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Qin, J. Income effect of rural E-commerce: Empirical evidence from Taobao villages in China. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 96, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Luo, W. An empirical study on the coupling coordination and driving factors of rural revitalization and rural E-Commerce in the context of the digital economy: The case of Hunan province, China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhu, X.; Cao, H.; Huang, W. Research on the Paths of the Modern Agricultural Industrial System Promoting Income Increases and Prosperity for Farmers Based on the fsQCA Method. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, Y. Digital Economy, Rural E-Commerce Development, and Farmers’ Employment Quality. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszko-Wójtowicz, E.; Deep Sharma, G.; Dańska-Borsiak, B.; Grzelak, M.M. Innovation-driven e-commerce growth in the EU: An empirical study of the propensity for online purchases and sustainable consumption. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zeng, Y.; Ye, Z.; Guo, H. E-commerce development and urban-rural income gap: Evidence from Zhejiang Province, China. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2021, 100, 475–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Ding, X.; Cheng, P. Exploring the income impact of rural e-commerce comprehensive demonstration project and determinants of county selection. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Qiu, A.; Huang, Y. Impact of e-commerce development on rural income: Evidence from counties in revolutionary old areas of China. Econ. Labour Relat. Rev. 2024, 35, 345–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Wang, P. WeChat E-commerce, social connections, and smallholder agriculture sales performance: A survey of orange farmers in Hubei Province, China. Agriculture 2023, 13, 2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Fang, J.; Ye, J. Does E-Commerce Construction Boost Farmers’ Incomes? Evidence from China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q. Advanced Econometrics and Stata Applications; Higher Education Press: Beijing, China, 2014; pp. 250–271. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Yang, S. The road to common prosperity: Can the digital countryside construction increase household income? Sustainability 2023, 15, 4020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.C. Research on the impact of rural e-commerce development on the quality and efficiency improvement of rural residents’ income. J. Commer. Econ. 2022, 22, 149–152. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.H. Empirical Analysis of the Relationship between the Development of Rural E-commerce and the Income Increase of Rural Residents in China—Based on Panel Data of 11 Provinces and Cities in the Yangtze River Economic Belt. J. Commer. Econ. 2020, 4, 125–128. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, F.L. Research on the Income-Increasing Effect of Rural E-Commerce on Farmers’ Income. Ph.D. Thesis, Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.X. Research on the impact of e-commerce in China on the consumption structure and its spatial spillover effect. J. Commer. Econ. 2022, 4, 65–68. [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China. Division Method of the Eastern, Central, Western and Northeastern Regions. Available online: http://hnzdhd.stats.gov.cn/dcsj/tjbz/201706/t20170620_89983.html (accessed on 17 November 2024).

| Author (Year) | Research Objectives | Research Methods | Research Indicators | Research Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goyal (2008) [30] | Impact of Internet penetration on agricultural product prices | Market Research (India) | Speed of Information Dissemination, Selling Prices of Agricultural Products | Internet penetration accelerates information flow, enabling farmers to sell soybeans at higher prices. |

| Aker (2010) [31] | Relationship between mobile phone usage and farmers’ income | Empirical Study (a Survey of Farmers in Niger) | Market Information Access, Technology Adoption Rate, Productivity | Mobile phone usage enhances farmers’ access to market information, thereby boosting productivity and increasing income. |

| Courtois and Subervie (2015) [32] | Relationship between e-commerce platform usage and farmers’ income growth | Bargaining Model (Sub-Saharan Africa) | Bargaining Power, Selling Prices | Selling agricultural products through e-commerce platforms enhances farmers’ income. |

| M Hafiz Yusoff (2019) [35] | Association between e-commerce platform usage and income growth | Survey Research (1060 Respondents in Malaysia) | Platform Usage Frequency, Income Growth Rate | Rural e-commerce platform usage exhibits a significant positive correlation with income growth. |

| Qiu et al. (2024) [39] | Mechanisms of e-commerce-driven income growth and heterogeneous effects | Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) Regression and Mediation-Effect Model | Information Access, Operational Costs, Financial Support | E-commerce promotes income growth via three pathways—information access, cost reduction, and financial support—but its effects vary with education levels and regional disparities. |

| Guan et al. (2024) [40] | The impact of e-commerce development on farmers’ income | Quantile Regression Analysis | Income Levels, Gini Coefficient | E-commerce significantly boosts the income of low-income farmers. |

| Liu et al. (2021) [41] | Determinants of farmers’ e-commerce adoption and its impact on income | Endogenous Switching Regression (ESR) Analysis | Geographic Location (Distance to Towns), Adoption Decisions | Farmers located closer to towns benefit more from e-commerce, with geographic location emerging as a key determinant of income disparities among adopters. |

| Li and Qin (2022) [43] | The impact of ‘Taobao Villages’ on farmers’ income | Continuous Difference-in-Differences (DID) Analysis | Proportion of Taobao Villages, Growth Rate of Farmers’ Net Income | A 1% increase in the proportion of Taobao Villages leads to a 3.6% growth in farmers’ net income. |

| Li (2022) [4] | Analysis of rural e-commerce development levels and regional disparities | Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) and Cluster Analysis | Infrastructure, Talent, Digital Governance | China’s rural e-commerce exhibits a regional divide characterized by stronger development in southern and eastern regions compared to northern and western areas. |

| Li et al. (2025) [45] | The impact of modern agricultural industrial systems on farmers’ multidimensional income | Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) | Wage Income, Operating Income, Property Income | Farmers’ income is influenced by the combined effects of the length, breadth, and depth of agricultural industrial systems, necessitating multidimensional coordinated optimization. |

| System | Evaluation | Index Measurement Method | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rural e-commerce subsystem | Fixed Investment in E-commerce Services | Fixed asset investment in transportation, warehousing, and postal services across the society | CNY 100 million |

| Fixed Investment in E-commerce Industry | Fixed asset investment in information transmission, software, and information technology services across the society | CNY 100 million | |

| Internet Penetration Rate | Ratio of the number of rural netizens to the rural population | % | |

| Mobile Phone Ownership | Number of mobile phones per 100 rural households at year-end | unit | |

| Computer Ownership | Number of computers per 100 rural households at year-end | unit | |

| Rural Delivery Routes | Length of routes delivering to rural households on postal sections | km | |

| Proportion of Post-Serviced Administrative Villages | Ratio of administrative villages with postal service to all administrative villages | % | |

| Optical Fiber Cable Coverage | Length of optical fiber cable lines per square kilometer | km | |

| E-commerce Sales Volume | Total transaction value of goods and services sold via online orders | CNY 100 million | |

| Number of Taobao Villages | Number of villages where active online stores account for ≥10% of local households and annual e-commerce transactions reach CNY ≥10 million | unit | |

| Postal Service Volume | Monetary value of total services/products provided by postal departments | CNY 100 million | |

| Express Delivery Volume | Total quantity of express services handled by courier companies | 100 million units | |

| Farmers’ income increase subsystem | Per Capita Disposable Income of Rural Residents | Sum of income for final consumption and savings, measuring rural residents’ living standards and purchasing power | CNY |

| Per Capita Consumption Expenditure of Rural Residents | Total expenditure on rural residents’ personal and household living consumption, and collective consumption for individuals | CNY |

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ln_pinc | 403 | 9.4841 | 0.4431 | 8.3612 | 10.6687 |

| ln_pcc | 403 | 9.2792 | 0.4212 | 8.0539 | 10.3347 |

| ecsd | 403 | 0.1849 | 0.1166 | 0.0292 | 0.8304 |

| ln_ecsv | 403 | 7.4278 | 1.5907 | 2.1041 | 10.6536 |

| hrc | 403 | 7.7335 | 0.8147 | 3.8039 | 9.9552 |

| fe | 403 | 0.2888 | 0.2044 | 0.1050 | 1.3538 |

| ln_edv | 403 | 10.8915 | 0.4715 | 9.6818 | 12.2075 |

| ur | 403 | 0.5971 | 0.1292 | 0.2281 | 0.8983 |

| ppi | 403 | 1.3966 | 0.5213 | 0.2000 | 2.58000 |

| lvr | 403 | 1.5561 | 0.4717 | 0.6689 | 2.9975 |

| Variable | ln_pinc | ln_pcc | ecsd | ln_ecsv | hrc |

| Statistic | 0.5498 | 0.2913 | 0.2358 | −0.0437 | −0.0891 |

| p-Value | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Result | stable | stable | stable | stable | stable |

| Variable | fe | ln_edv | ur | ppi | lvr |

| Statistic | 0.1683 | 0.4085 | 0.3422 | 0.1193 | 0.2321 |

| p-Value | 0.0003 | 0.0062 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Result | stable | stable | stable | stable | stable |

| Variable | VIF | 1/VIF |

|---|---|---|

| ur | 8.14 | 0.122855 |

| ln_edv | 6.48 | 0.154287 |

| fe | 4.47 | 0.223580 |

| hrc | 3.87 | 0.258313 |

| lvr | 2.80 | 0.387754 |

| ecsd | 2.58 | 0.387754 |

| ppi | 1.90 | 0.526450 |

| Mean VIF | 4.32 |

| Fixed-effect (within) regression | Number of obs = 403 | |||||

| Group variable: year | Number of groups = 13 | |||||

| R-squared: | Obs per group: | |||||

| Within = 0.8513 | min = 31 | |||||

| Between = 0.9961 | avg = 31.0 | |||||

| Overall = 0.8925 | max = 31 | |||||

| F(7, 383) = 313.17 | ||||||

| corr(u_i, Xb) = 0.6160 | Prob > F = 0.0000 | |||||

| ln_pinc | Coefficient | Std. err. | t | p > |t| | [95% conf. interval] | |

| ecsd | 0.5616161 | 0.081709 | 6.87 | 0.000 | 0.4009616 | 0.7222705 |

| hrc | 0.0255134 | 0.0140599 | 1.81 | 0.070 | −0.0021309 | 0.0531577 |

| fe | 0.0317401 | 0.0605104 | 0.52 | 0.600 | −0.0872341 | 0.1507143 |

| ln_edv | 0.541813 | 0.0403838 | 13.42 | 0.000 | 0.4624114 | 0.6212146 |

| ur | 0.3790538 | 0.1431655 | 2.65 | 0.008 | 0.0975651 | 0.6605425 |

| ppi | 0.0058702 | 0.0017902 | 3.28 | 0.001 | 0.0023504 | 0.00939 |

| lvr | 0.0422408 | 0.0229421 | 1.84 | 0.066 | −0.0028675 | 0.0873491 |

| _cons | 2.923868 | 0.4107824 | 7.12 | 0.000 | 2.116197 | 3.731539 |

| sigma_u | 0.12013644 | |||||

| sigma_e | 0.11601267 | |||||

| rho | 0.51745724 (fraction of variance due to u_i) | |||||

| F-test that all u_i = 0: F(12, 383) = 10.79 | Prob > F = 0.0000 | |||||

| Hausman FE RE, Constant Sigmamore | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficients | ||||

| (b) | (B) | (b − B) | Sqrt (diag(V_b − V_B)) | |

| FE | RE | Difference | Std. Err. | |

| ecsd | 0.5616161 | 0.7273939 | −0.1657778 | 0.0206537 |

| hrc | 0.0255134 | 0.0384127 | −0.0128993 | 0.0017627 |

| fe | 0.0317401 | −0.045787 | 0.0775271 | 0.0099367 |

| ln_edv | 0.541813 | 0.8176957 | −0.2758827 | 0.0291442 |

| ur | 0.3790538 | −0.306655 | 0.6857088 | 0.0735395 |

| ppi | 0.0058702 | 0.0158202 | −0.00995 | 0.001059 |

| lvr | 0.0422408 | 0.1544903 | −0.1122495 | 0.0116456 |

| _cons | 2.923868 | −0.0503436 | 2.974212 | 0.3135371 |

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Variables | ln_pinc | ln_pinc |

| ecsd | 1.972 *** | 0.218 *** |

| (0.120) | (0.0487) | |

| hrc | 0.0541 *** | |

| (0.0151) | ||

| fe | 0.337 *** | |

| (0.0871) | ||

| ln_edv | 0.892 *** | |

| (0.0332) | ||

| ur | 0.865 *** | |

| (0.167) | ||

| ppi | 0.00508 * | |

| (0.00262) | ||

| lvr | 0.0792 *** | |

| (0.0144) | ||

| Constant | 9.120 *** | −1.479 *** |

| (0.0250) | (0.265) | |

| Observations | 403 | 403 |

| Number of id | 13 | 31 |

| R-squared | 0.409 | 0.984 |

| East | Middle | West | Northeast | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | ln_pinc | ln_pinc | ln_pinc | ln_pinc |

| ecsd | 0.0830 | 0.788 *** | 0.219 | 3.243 *** |

| (0.0518) | (0.231) | (0.246) | (0.302) | |

| hrc | 0.00429 | 0.0596 ** | 0.0102 | 0.0196 |

| (0.0169) | (0.0272) | (0.0225) | (0.0251) | |

| fe | 1.022 *** | 1.537 *** | 0.0102 | 0.446 *** |

| (0.151) | (0.316) | (0.115) | (0.136) | |

| ln_edv | 1.130 *** | 0.546 *** | 0.743 *** | 0.464 *** |

| (0.0325) | (0.0574) | (0.0698) | (0.0862) | |

| ur | 0.248 | 1.990 *** | 1.723 *** | 1.705 ** |

| (0.239) | (0.387) | (0.344) | (0.804) | |

| ppi | 0.0122 * | 0.0115 ** | 0.0111 *** | 0.00952 *** |

| (0.00719) | (0.00457) | (0.00423) | (0.00207) | |

| lvr | 0.153 *** | 0.0526 | 0.0448 *** | 0.115 *** |

| (0.0237) | (0.0437) | (0.0164) | (0.0326) | |

| Constant | 3.653 *** | 1.351 *** | 0.379 | 2.955 *** |

| (0.355) | (0.485) | (0.620) | (0.615) | |

| R-squared | 0.992 | 0.995 | 0.988 | 0.998 |

| Variables | Replace Explained Variable | Replace Explanatory Variables |

|---|---|---|

| ecsd | 0.315 *** | |

| (0.0638) | ||

| hrc | 0.0384 * | 0.0551 *** |

| (0.0198) | (0.0144) | |

| fe | 0.613 *** | 0.324 *** |

| (0.114) | (0.0825) | |

| ln_edv | 0.840 *** | 0.858 *** |

| (0.0435) | (0.0311) | |

| ur | 1.040 *** | 0.717 *** |

| (0.218) | (0.154) | |

| ppi | 0.00190 | 0.00732 *** |

| (0.00342) | (0.00252) | |

| ln_ecsv | 0.0459 *** | |

| (0.00600) | ||

| lvr | 0.110 *** | 0.0744 *** |

| (0.0188) | (0.0137) | |

| Constant | −1.180 *** | −1.341 *** |

| (0.347) | (0.235) | |

| Observations | 403 | 403 |

| R-squared | 0.973 | 0.985 |

| Number of id | 31 | 31 |

| Replace Explained Variable (ln_pcc) | Replace Explanatory Variables (ln_pinc) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | East | Middle | West | Northeast | East | Middle | West | Northeast |

| ecsd | 0.192 ** | 1.250 *** | 0.915 *** | 3.264 *** | ||||

| (0.0899) | (0.283) | (0.273) | (0.830) | |||||

| hrc | 0.0474 * | 0.0167 * | 0.0193 * | 0.0223 * | 0.0121 * | 0.0375 * | 0.0273 * | 0.0563 * |

| (0.0294) | (0.0334) | (0.0249) | (0.0692) | (0.0130) | (0.0293) | (0.0208) | (0.0576) | |

| fe | 1.657 *** | 1.199 *** | 0.197 * | 0.164 * | 0.679 *** | 0.625 ** | 0.0132 * | 0.645 ** |

| (0.263) | (0.387) | (0.127) | (0.373) | (0.119) | (0.309) | (0.104) | (0.305) | |

| ln_edv | 1.043 *** | 0.457 *** | 0.604 *** | 0.234 | 0.926 *** | 0.496 *** | 0.706 *** | 0.517 ** |

| (0.0563) | (0.0703) | (0.0773) | (0.237) | (0.0292) | (0.0708) | (0.0595) | (0.217) | |

| ur | 0.705 * | 0.785 * | 1.314 *** | 0.734 * | 0.570 *** | 1.312 *** | 1.602 *** | 1.868 *** |

| (0.415) | (0.474) | (0.381) | (2.213) | (0.186) | (0.394) | (0.313) | (1.638) | |

| ppi | 0.0412 *** | 0.00889 * | 0.00035 * | 0.00183 * | 0.0162 *** | 0.00456 | 0.00415 * | 0.00648 * |

| (0.0125) | (0.00560) | (0.00468) | (0.00570) | (0.00516) | (0.00512) | (0.00407) | (0.00484) | |

| lvr | 0.139 *** | 0.103 * | 0.0941 *** | 0.260 *** | 0.102 *** | 0.164 *** | 0.0291 * | 0.00842 |

| (0.0411) | (0.0535) | (0.0182) | (0.0899) | (0.0173) | (0.0371) | (0.0151) | (0.0722) | |

| ln_ecsv | 0.0780 *** | 0.0241 * | 0.0396 *** | 0.0111 * | ||||

| (0.00855) | (0.0123) | (0.00745) | (0.0172) | |||||

| Constant | −1.683 *** | 3.074 *** | 1.408 ** | 5.724 *** | −2.014 *** | 1.961 *** | 0.432 * | 0.711 * |

| (0.616) | (0.594) | (0.686) | (1.694) | (0.241) | (0.649) | (0.503) | (1.406) | |

| Observations | 130 | 78 | 156 | 39 | 130 | 78 | 156 | 39 |

| R-squared | 0.977 | 0.994 | 0.985 | 0.988 | 0.996 | 0.995 | 0.990 | 0.991 |

| Number of id | 10 | 6 | 12 | 3 | 10 | 6 | 12 | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, H.; Ding, M.; Kan, Y.; Dong, Q. A Study on the Relationship Between Rural E-Commerce Development and Farmers’ Income Growth. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3879. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17093879

Liu H, Ding M, Kan Y, Dong Q. A Study on the Relationship Between Rural E-Commerce Development and Farmers’ Income Growth. Sustainability. 2025; 17(9):3879. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17093879

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Hui, Meiqin Ding, Yujin Kan, and Qi Dong. 2025. "A Study on the Relationship Between Rural E-Commerce Development and Farmers’ Income Growth" Sustainability 17, no. 9: 3879. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17093879

APA StyleLiu, H., Ding, M., Kan, Y., & Dong, Q. (2025). A Study on the Relationship Between Rural E-Commerce Development and Farmers’ Income Growth. Sustainability, 17(9), 3879. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17093879