Abstract

Inclusive education has become a central issue in global educational reform, advancing the agenda for educational equity and social justice. However, despite significant theoretical and policy developments, research in this field remains fragmented, and no coherent framework currently exists. This study analyzes 3663 SSCI papers published between 2000 and 2024, using Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) topic modeling to identify 15 distinct research themes in inclusive education. By combining LDA with manual coding, four key research areas emerged: concept and connotation, macro needs and support, micro-level implementation, and implementation effects and challenges. These findings highlight the interconnections between policy, practice, and environmental factors shaping inclusive education. Based on these results, an integrated input–process–outcome–feedback (IPOF) framework is proposed to advance the understanding of inclusive education’s evolution, effectiveness, and implementation. This framework offers actionable insights for policymakers and educators, helping to promote inclusive education aligned with Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4) and advancing global educational equity.

1. Introduction

Inclusive education has become a central focus of global educational reform, driven by the advocacy for educational equity and social justice that began in the mid-20th century. By the 1980s, it evolved into a practical framework for dismantling barriers between general and special education, ensuring equal opportunities for all students [1]. This approach promotes resource equity, addresses diverse learning needs, and fosters social integration [2].

International frameworks like the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development further emphasize the critical role of inclusive education in advancing social justice and sustainable development. Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4) positions inclusive education as essential for lifelong learning and equal access [3], contributing not only to educational equity but also to cultural identity, social cohesion, and economic development [4].

Despite advancements in theory and policy, inclusive education lacks a systematic framework for analyzing its core issues and structures. The multidimensional nature of inclusive education—spanning policy, pedagogy, and culture—presents challenges for traditional qualitative methods, particularly in synthesizing large bodies of literature. Data-driven text mining techniques, such as Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA), offer a promising solution by uncovering latent themes from textual data and providing a structured approach to organizing knowledge [5].

By combining LDA with manual coding, this study enhances topic modeling, transforming keywords into higher-order themes and integrating data-driven insights with established theories. This hybrid approach refines thematic analysis and theoretical frameworks [6]. The study develops a novel analytical framework for inclusive education, strengthening the field’s methodological foundations and providing actionable insights for policymakers and practitioners. Using optimization techniques and evaluative metrics like perplexity and topic coherence ensures the rigor and reliability of its findings. Ultimately, this research aims to offer fresh perspectives on both theoretical and practical aspects of inclusive education, contributing to the broader goals of educational equity and social inclusion.

2. Literature Review

Inclusive education has advanced the global agenda for educational equity, providing both theoretical and practical guidance for the development and implementation of inclusive policies worldwide [7]. Research has expanded to areas such as teacher development, student growth, and home–school collaboration [8]. However, its implementation remains inconsistent. Developed countries often focus on creating resource-rich, technology-driven environments, while developing nations struggle with limited resources and rigid educational systems [9]. Moreover, some countries restrict inclusive education policies to specific groups, such as students with disabilities, overlooking the broader needs of diverse learners [10]. Many countries also face challenges in policy implementation due to unclear objectives and weak enforcement, limiting the effectiveness of inclusive measures [11].

As research on inclusive education has deepened, scholars have used retrospective studies to examine its conceptual evolution, policy frameworks, and practical pathways from multiple perspectives, generating various research methods and analytical approaches. Methodologically, these studies have primarily employed qualitative analyses, bibliometric techniques, and meta-analyses.

Qualitative analyses, through in-depth reviews of policy documents, case studies, and theoretical literature, have highlighted key theoretical foundations. For instance, Ainscow and Miles explored the influence of international policy documents on inclusive education, noting a shift from addressing special needs to embracing broader diversity and inclusion [12]. Booth and Ainscow introduced the “Index for Inclusion” a framework for analyzing organizational and cultural changes in schools [13]. However, the subjective nature of qualitative methods limits their ability to handle large-scale, heterogeneous data, affecting the replicability and generalizability of findings.

Bibliometric and knowledge-mapping techniques have also gained prominence, identifying research trends, knowledge structures, and scholarly networks. Messiou used knowledge mapping to show that research themes in inclusive education have expanded from focusing on specific learner groups to addressing broader issues of social inclusion and diversity [14]. Nilholm and Göransson found regional differences in research priorities, with European scholarship focusing on policy legitimacy and implementation, while North American research tends to emphasize theoretical development and practical guidance [15]. Erten and Savage identified regional disparities and policy-driven orientations in inclusive education research through bibliometric analysis [16]. While these methods are useful for identifying research trends and networks, their reliance on keywords and citation linkages limits their ability to uncover deeper semantic structures within texts, hindering a more comprehensive understanding of the field’s themes.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses, which focus on structured integration, offer a broader retrospective view of inclusive education. For example, Van Mieghem assessed the practical efficacy and impact of stakeholders—such as teachers and parents—in implementing inclusive education, emphasizing the critical role of teachers in its success [17]. However, these approaches often focus on a single theme and rely on limited data sources, making it challenging to manage large-scale, cross-disciplinary datasets and fully capture the complex, diverse thematic structure of inclusive education.

Currently, inclusive education research demonstrates methodological and thematic diversity, with retrospective analyses focusing primarily on policy, cultural, and theoretical dimensions. In the policy dimension, studies have reviewed the formulation and effectiveness of inclusive education policies. Artiles emphasized that the cultural responsiveness of policies is crucial for effective inclusive education, yet vague policy goals and a lack of actionable evaluation indicators limit their practical application and overall efficacy [18]. Research from the cultural perspective highlights the profound impact of sociocultural differences on inclusive education practice, particularly in how teachers and parents perceive and implement inclusion. Messiou pointed out that cultural backgrounds not only shape the logic of inclusive practice but also influence the barriers encountered during implementation; however, existing studies often center on specific cultural contexts and lack cross-cultural comparisons and systematic analyses [14]. From a theoretical standpoint, Slee employed a social justice framework to investigate how inclusive education redistributes resources and power to realize educational equity and to shape a more inclusive sociocultural milieu [7]. Although these perspectives provide significant theoretical and practical support, they also illustrate the thematic limitations and insufficient global-scale investigations in the field.

While these studies have expanded inclusive education research, their thematic scope is often narrow, limiting interactive analysis across perspectives. As Nilholm and Göransson demonstrated through bibliometric analysis, research hotspots in inclusive education are dispersed, and the interconnections between policy, culture, and theory remain underexplored [15]. Rapp further noted that, despite the growing diversity of research themes, there is a lack of structural focus on theme distribution and insufficient research into the multidimensional interrelations between thematic areas and disciplinary development [19].

Against this backdrop, this study integrates topic modeling techniques and human-assisted analysis to systematically identify research themes within inclusive education. This approach reduces the subjective biases inherent in data-driven models, enhances the practical relevance of the results, and offers a comprehensive view of inclusive education research from both theoretical and practical perspectives. The findings aim to provide scholars and policymakers with a broad academic overview, support knowledge innovation in inclusive education, and offer data-driven insights and theoretical guidance for its advancement and practical transformation.

To achieve these objectives, this study proposes the following research questions:

RQ1: What are the primary research themes within the field of inclusive education?

RQ2: How do these research themes reflect the core issues of inclusive education, as well as their significance in policy, theory, and practice?

RQ3: Are there intrinsic connections among different research themes, and how do they jointly constitute the overall knowledge structure of inclusive education?

3. Data Collection and Methodology

3.1. Data Sources and Screening

This study uses the Web of Science (WOS) database, a comprehensive and authoritative source of peer-reviewed academic literature, widely recognized for its representativeness in scholarly evaluation [20]. The search employed “inclusive education” as the exact query term, restricted to the Topic (TS) field to ensure that the full phrase, rather than the separate terms “inclusive” and “education”, was captured. This approach aimed to include all literature referencing inclusive education in titles, abstracts, or keywords, thereby minimizing the risk of overlooking relevant studies.

To ensure temporal relevance and policy alignment, this study focused on literature published between 2000 and 2024. Several considerations informed the selection of this timeframe:

- Rapid development of inclusive education research: Since the early 21st century, the volume of inclusive education literature has grown substantially. Using the year 2000 as a starting point enables us to capture key developments in the field.

- Alignment with policy milestones: in 2000, UNESCO’s Dakar Framework for Action explicitly identified inclusive education as a priority for educational development, providing a foundation for subsequent theoretical and practical studies.

- Contemporary relevance: selecting literature from the past 25 years ensures that the research captured is closely tied to current policies and practical applications.

The following eligibility criteria were applied to ensure the quality and relevance of the included literature. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) peer-reviewed journal articles; (2) publications categorized under “Education & Educational Research” and “Special Education” within the Web of Science (WOS) database; (3) articles published between 2000 and 2024; and (4) articles with available abstracts.

Exclusion criteria included the following: (1) records belonging to non-educational disciplines; (2) conference papers, book reviews, editorials, and other non-research publications; (3) duplicate records or those missing essential metadata; and (4) articles unrelated to inclusive education, as determined through manual screening of titles and abstracts.

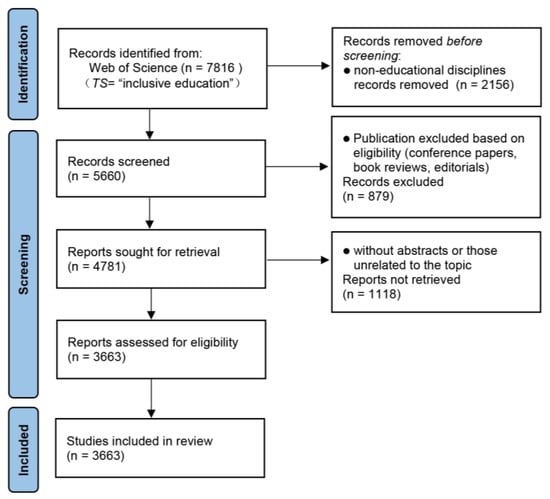

The initial search yielded 7816 records. A stepwise screening process was conducted to refine the dataset. First, discipline filtering was performed by excluding 2156 records that did not fall within the educational subject categories based on WOS classification. Second, we applied document-type filtering to remove 879 conference papers, book reviews, and editorials. Although such sources may provide early insights or theoretical perspectives, they typically lack the empirical rigor and structured abstracts required for LDA topic modeling. This focus on peer-reviewed journal articles aligns with common practices in social science research [21].

Subsequently, two reviewers independently screened the remaining 4781 records. Articles without abstracts or those unrelated to inclusive education were excluded, resulting in the removal of 1118 additional records. Discrepancies during screening were resolved through discussion until consensus was achieved. Ultimately, 3663 high-quality journal articles were retained for analysis. The detailed screening process is illustrated in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1), and the review was conducted in accordance with PRISMA 2020 guidelines (See Supplementary Materials).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

3.2. LDA Topic Modeling

Topic modeling is a powerful natural language processing technique for discovering latent themes in large textual datasets. Among various methods, Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) is one of the most widely used approaches. LDA applies Bayesian probabilistic modeling to create a three-layer semantic structure that links documents, topics, and terms [5]. Unlike traditional qualitative analyses, LDA minimizes subjective biases by using statistical methods, making it highly effective for large-scale, data-driven theme discovery.

In LDA, topics are treated as probability distributions over words, and documents are treated as mixtures of topics. By analyzing the frequency patterns of terms across documents, the algorithm identifies topics that capture underlying structures in the data. However, LDA is sensitive to preprocessing decisions such as stemming, stop-word removal, and lemmatization, which can influence the results. For example, removing common stop-words helps reduce noise, but improper stemming or lemmatization can lead to overgeneralization of terms. To mitigate these effects, we carefully applied word standardization techniques and validated the preprocessing steps through manual coding.

To determine the optimal number of topics (K), we rely on two key metrics: perplexity and coherence. Perplexity measures the model’s ability to predict unseen data, with lower values indicating better performance. Coherence evaluates the semantic relevance of the topics, with higher values indicating stronger topic quality. These metrics guide the selection of the best-fitting model for our data set.

3.3. Topic Identification and Clustering

To ensure the accuracy of the LDA modeling, we first pre-processed the collected literature data. This involved text cleaning, which removed stop words (e.g., “the”, “and”) and irrelevant characters (e.g., punctuation and numbers). Stemming and lemmatization were applied to standardize words, consolidating synonyms and various word forms into a unified representation. We also used the TF-IDF (Term Frequency–Inverse Document Frequency) to extract keywords that best represented the data’s thematic content.

After preprocessing, LDA modeling was conducted using Gensim [22]. The results were visualized using PyLDAvis [23], which provided interactive displays of topic distributions and keyword relationships. The optimal number of topics (K) was determined through iterative trials based on perplexity and coherence scores. For topic identification, two doctoral candidates specializing in education independently coded the high-weight keywords generated by LDA. Any discrepancies were resolved by consulting a third expert to reach a consensus. This manual coding process was crucial in compensating for potential misclassification by LDA, especially in cases where semantic nuances or lexical overlap might have caused the algorithm to group unrelated terms together under the same topic. The consensus process helped ensure consistency in theme labeling and thematic validity.

Based on visual mapping, keyword semantics, and manual coding, we identified thematic clusters, resulting in a clear framework of key research areas in inclusive education and their connections.

3.4. Detailed Analysis Workflow

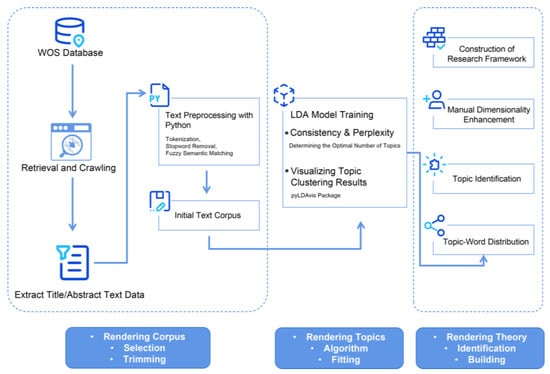

The analysis involved several stages: retrieving relevant literature from the WOS database, preprocessing the data, applying LDA topic modeling, visualizing topic clusters, deriving topic word distributions, and preliminarily identifying topics. Finally, manual coding and classification were used to develop a comprehensive research framework for inclusive education. As illustrated in Figure 2, the analytical process consists of three main components: the corpus, the topics, and their theoretical interpretations.

Figure 2.

Analysis workflow.

4. Result

4.1. Overview of the Dataset

4.1.1. Publication Trends

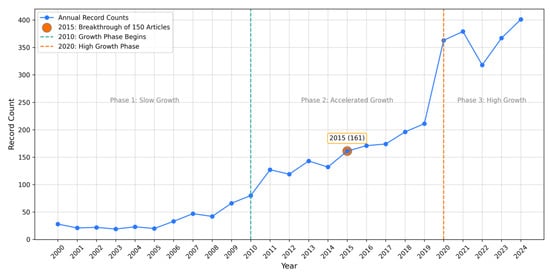

From 2000 to 2024, the volume of scholarly literature on inclusive education has grown markedly, reflecting its increasing prominence as a key issue in the field of education (Figure 3). The publication trajectory can be divided into three distinct phases:

Figure 3.

Trends in the number of publications from 2000 to 2024.

- Slow growth period (2000–2010): The average annual growth rate was 6.7%, with publications increasing from 28 in 2000 to 80 in 2010. Research during this phase was shaped by initiatives such as the Salamanca Statement and the Dakar Framework for Action, focusing on conceptual definitions, policy frameworks, and the theoretical foundations of inclusive education. Special educational needs interventions marked the initial systematic exploration of educational equity in practice.

- Accelerated development period (2011–2019): The annual growth rate increased to 14.2%, with publications surpassing 150 in 2015 and doubling by 2019, reaching 211 papers. This phase was heavily influenced by international policies, including the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and SDG 4, prompting deeper practical analyses. Key topics included teacher professional development, school environmental adaptations, and cross-cultural education, reflecting the growing complexity of inclusive education.

- High growth period (2020–2024): Research on inclusive education reached its peak, with 401 papers published in 2024—14 times the number in 2000. This surge can be attributed to the increased focus on educational equity following the COVID-19 pandemic and the widespread adoption of digital educational tools. Recent studies have concentrated on resource allocation, technology-assisted learning, and the outcomes of social inclusion, providing empirical support and theoretical guidance for innovations in inclusive education.

The expanding volume of literature underscores the ongoing focus on educational equity and social inclusion, forming a solid foundation for our data-driven analysis and highlighting the need for data-driven methods to identify core issues in the field.

4.1.2. Journal Distribution

Publications on inclusive education are spread across a diverse range of journals, including specialized journals dedicated to inclusive education, interdisciplinary outlets, and regionally focused journals. Statistical analysis reveals both a pronounced concentration and a certain degree of diversity in the distribution of publications.

The International Journal of Inclusive Education stands out as a flagship journal in this field, publishing 750 articles and accounting for 20.5% of the total dataset. This journal focuses on policies, theoretical frameworks, and practical pathways of inclusive education, serving as a critical platform for advancing scholarly discourse. The European Journal of Special Needs Education (192 articles, 5.3%) and the International Journal of Disability Development and Education (142 articles, 3.9%) follow closely, each emphasizing, respectively, educational support for students with special needs and region-specific research on inclusive education. Together, these three journals contribute 30% of the literature, underscoring the pivotal role of core journals in shaping the academic ecosystem of inclusive education.

Beyond these core outlets, interdisciplinary journals have played a key role in broadening the thematic scope of inclusive education research. Teaching and Teacher Education (115 articles, 3.1%) and Teachers College Record (39 articles, 1.1%) focus on the role of teachers in inclusive education and their professional development, offering valuable insights into the relationship between teacher education and inclusive pedagogy. Sustainability (97 articles, 2.7%) examines how inclusive education can promote social inclusion and educational equity within the framework of sustainable development goals. The participation of these journals reflects the field’s expanding horizons, connecting inclusive education to global policy agendas, social justice issues, and environmental sustainability.

In addition, several regionally oriented or thematically specialized journals have secured a place in inclusive education research. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities (73 articles, 2.0%) and Remedial and Special Education (46 articles, 1.3%) highlight supportive inclusion strategies for students with significant needs. The South African Journal of Education (43 articles, 1.2%) sheds light on the characteristics of implementing inclusive education within developing countries, such as South Africa. Meanwhile, Sport Education and Society (45 articles, 1.2%) underscores the field’s gradual extension into extracurricular activities and physical education, mirroring the increasing thematic diversity of inclusive education research.

Overall, the data indicate a high degree of concentration: the top 10 journals contribute 42.1% of all articles, providing a stable platform for academic exchange. At the same time, the involvement of interdisciplinary and regional journals demonstrates that inclusive education research is evolving into a multidisciplinary domain, attracting increasingly diverse scholarly attention.

4.1.3. Publication by Countries

Inclusive education research is globally dispersed but exhibits pronounced concentration and regional characteristics.

The United States (1034 articles, 28.2%), the United Kingdom (696 articles, 19.0%), and Australia (442 articles, 12.0%) lead the field, collectively accounting for 2172 articles—59.2% of the total. The U.S. stands as a central node in inclusive education research, offering broad coverage that spans from policy and legal guarantees to practical dimensions such as teacher training, individualized support, and technology-enhanced learning. This body of work also emphasizes the integration of special and general education systems, making the U.S. a major driving force in global inclusive education research. The U.K. follows, underscored by its influential policy framework for inclusive education and a scholarly emphasis on the profound impact of cultural diversity on inclusive practice. Australia’s focus lies in teacher education and community support, particularly by enhancing teachers’ capacity to deliver inclusive instruction—a practical orientation that strongly characterizes its contributions.

Beyond the English-speaking world, several European and Asia–Pacific nations make significant contributions.

Europe: Spain (250 articles, 6.8%) leads non-English-speaking countries in publication volume, focusing on educational equity and social inclusion policies. Northern European countries, such as Germany (145 articles, 4.0%), Sweden (114 articles, 3.1%), Norway (109 articles, 3.0%), and Finland (92 articles, 2.5%), benefit from high welfare systems, emphasizing educational equity in multilingual contexts and the role of inclusive education in broader social development. The Netherlands (74 articles, 2.0%) stands out for its research on technology-assisted instruction and educational psychology for students with special needs.

Asia–Pacific: China (171 articles, 4.7%) has shown sustained growth in recent years, with research focusing on policy implementation, support for students with disabilities, and resource allocation. New Zealand (69 articles, 1.9%) addresses the integration of Māori cultural perspectives into inclusive education, offering a localized viewpoint.

Africa: South Africa (155 articles, 4.2%) represents research from the African continent. Its focus lies in educational equity and inclusive education practice under resource-limited conditions, exploring how to advance inclusive education goals in complex economic and social contexts.

This geographical distribution reveals a global research landscape with distinct thematic priorities and contextual dynamics, reflecting the multifaceted nature of inclusive education as a field of inquiry.

It is important to note, however, that the dominance of English-speaking countries in the dataset may also reflect the historical and policy leadership of these countries in shaping global inclusive education agendas. Many of the foundational frameworks and international discourses originated or gained prominence through Western advocacy and institutions. Therefore, while some geographical imbalance is evident, it also mirrors the real-world trajectory of inclusive education as a globally exported policy ideal.

4.2. Topic Identification

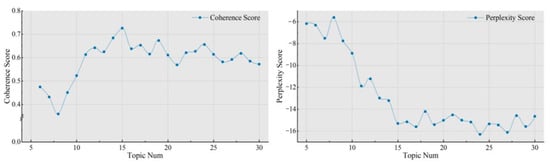

Before conducting the LDA topic analysis, the optimal number of topics (K) must be determined to ensure model accuracy. After importing the research data, Python (https://www.python.org/) code was used to calculate coherence and perplexity scores for models ranging from 5 to 30 topics, resulting in 25 candidate models. As shown in Figure 4, the coherence value peaks at K = 15. Although perplexity continues to decrease with an increasing number of topics, the rate of decline slows significantly after K = 15, showing only minor fluctuations. Therefore, this study adopts K = 15 as the optimal number of topics.

Figure 4.

Coherence score and perplexity score.

Based on the coherence and perplexity results, the number of topics was set to K = 15, with model parameters α = 50 and β = 0.01. The top 10 high-probability terms for each topic were extracted and arranged in descending order, serving as representative keywords to describe and label the respective topics.

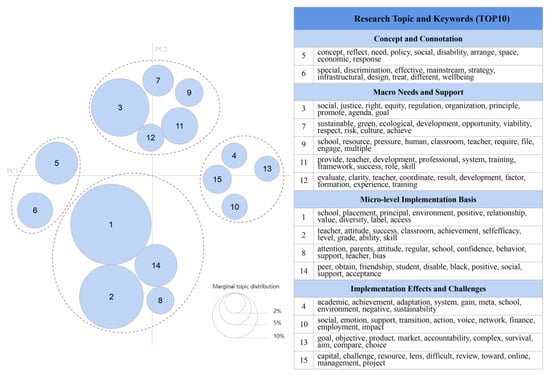

Two authors conducted an initial round of coding for the 15 topics, based on the probability distributions of topic terms, the distances between topics in the LDA topic map (Figure 5), and their understanding of inclusive education. A second round of coding was carried out by two doctoral candidates in education. Any discrepancies were resolved by consulting a third expert to reach a consensus. Although no formal statistical inter-coder reliability was calculated, coding disagreements were discussed and resolved through this consensus process, ensuring consistency and thematic validity. Ultimately, based on visual mapping distances, keyword semantics, and manual coding, five thematic clusters of research were identified.

Figure 5.

LDA theme modeling and research keywords.

Research Theme 1 includes Topics 5 and 6. Keywords such as “policy” and “strategy” relate to the background and implementation goals of inclusive education, while terms like “concept”, “special”, and “social” are associated with the conceptual underpinnings of inclusive education. Research Theme 2 encompasses Topics 3, 7, 9, 11, and 12. Keywords including “right”, “sustainable”, “resource”, “culture”, “development”, and “risk” reflect macro-level development needs and forms of support, encompassing educational rights, sustainable development, resource-efficient societies, cross-cultural considerations, and social risk factors. Research Theme 3 includes Topics 1, 2, 8, and 14. Its keywords—such as “school”, “teacher”, “parents”, “student”, “relationship”, “principal”, and “peer”—are more micro-level and practice-oriented, highlighting specific roles and systemic relationships. These elements are frequently identified in the literature as critical factors influencing inclusive education practices. Research Theme 4 includes Topics 4, 10, 13, and 15. Keywords such as “action”, “achievement”, “impact”, and “review” refer to the outcomes of inclusive education initiatives. Meanwhile, terms like “goal”, “voice”, and “challenge” indicate that some studies address the controversies and challenges facing the implementation of inclusive education.

4.3. Analysis of Identified Topics

4.3.1. Concept and Connotation

Since its proposal, inclusive education has remained a contentious term. Advocates argue that it represents an educational transformation grounded in rights and inclusivity [24]. Conversely, critics contend that it is merely a popular buzzword within the educational field, lacking substantive change [25]. Over the years, inclusion has become a significant concept in the field of special education, gradually replacing earlier terms such as “interaction” and “mainstreaming”. This shift aims to resist the stigmatization and labeling of difficulties and disabilities [26]. However, it is important to distinguish between the changing terminology and the actual transformation in educational practices. While the term “inclusion” has become more widely adopted, reflecting a more positive and comprehensive view of education for all students, true inclusion requires substantial changes in educational systems and practices. This includes adapting teaching methods, ensuring equitable resources, and fostering an inclusive environment where all students can thrive, rather than merely integrating students with special needs into general classrooms.

Inclusive education is characterized by both policy implications and dual practical and academic definitions. The UNCRPD explicitly calls for cultural, policy, and practice changes across all educational environments to accommodate diverse student needs. It emphasizes the elimination of segregation and barriers, advocating for personalized educational services tailored to individual students rather than expecting students to conform to existing education systems [27]. That said, it is important to distinguish between two interpretations of inclusive education. While personalized services are often framed as a solution, inclusive education is more broadly understood as a systemic transformation aimed at reshaping educational structures to accommodate the diversity of all learners. This transformation involves not only adapting individualized approaches but also rethinking curricula, teaching methodologies, and institutional policies to ensure that the education system itself is flexible and inclusive. Such systemic change challenges traditional pedagogical models and requires a critical re-examination of educational norms that have long prioritized uniformity over diversity. By focusing solely on individualized services, we risk reinforcing existing inequities and misconceptions, failing to address the deeper, systemic barriers to true inclusion.

Despite widespread support for inclusive education, significant challenges remain in its implementation. Some schools create special classrooms for students with learning difficulties, but these measures often result in spatial inclusion—placing students with disabilities in mainstream settings alongside their peers—without altering the underlying pedagogical practices [28]. Such an approach, often referred to as “fauxclusion” merely integrates students into physical spaces but fails to address the deeper systemic and educational changes required for genuine inclusion [29]. True inclusion involves more than just physical placement; it requires transforming teaching methods, curricula, and support systems to meet the diverse needs of all students, ensuring full participation in the learning process. International research reveals considerable variation in how inclusive education is defined and practiced across countries and regions. In some areas, it is viewed as a movement addressing the needs of all learners, while in others, it is seen as an optimized form of special education [18]. This ambiguity can marginalize specific groups and reinforce labels on individual differences [30], creating barriers to full participation. To address this complexity, Göransson and Nilholm propose a framework identifying four conceptual models of inclusive education [10]: (1) placement, focusing on students’ physical environment; (2) individualized specification, addressing the social and academic needs of specific students; (3) general individualization, accommodating the diverse needs of all students; and (4) community, emphasizing the development of inclusive educational communities. These models highlight the importance of creating a holistic and inclusive educational system that benefits all students, not just those with disabilities [14].

From policy to practice, the development of inclusive education reflects a transition in the educational field from emphasizing individual rights to advocating for social inclusion [31]. This evolution, responding to the needs of marginalized groups and the demand for systemic reform, has been explored through interdisciplinary research in psychology, pedagogy, and sociology. It aligns with the diverse teaching needs within schools and demonstrates a commitment to diversity and social equity in education [32].

Inclusive education has evolved from a policy concept to a widely adopted educational principle. It has transitioned from being a normative “ideal” to a “genuine” inclusive ecosystem, with its conceptual boundaries continuously expanding and becoming more tangible.

4.3.2. Macro Needs and Support

Education is widely recognized as a fundamental human right and serves as the “master key” for unlocking access to other rights and freedoms [33]. The right to education, particularly for children with disabilities, has been safeguarded directly or indirectly through numerous laws, regulations, and policy initiatives. At its core, the legal framework for inclusive education is rooted in the principle of equality, aiming to eliminate educational exclusion and ensure that every individual can exercise their right to education on the basis of equality and respect [34].

Beyond being a right, education is a critical instrument for driving societal progress. Inclusive education is increasingly regarded as a vital tool for building a humane and sustainable society [35]. It not only offers educational opportunities for individuals with diverse abilities but also fosters deeper transformations within educational ecosystems through diverse and inclusive learning environments [36]. To achieve sustainable development, especially during periods of crisis, it is essential to adopt educational models that integrate spiritual, cultural, and socio-economic dimensions. Inclusive education provides a viable pathway for advancing the cyclical development of education, society, and culture [37]. Its significance extends beyond addressing individual needs, as it leverages diversity and inclusivity to restore social stability and equilibrium [38].

However, the successful implementation of inclusive education requires robust resource allocation and institutional support. Resource shortages are often cited as a justification for denying educational services to students with special needs [39]. Unequal resource distribution not only diminishes the motivation of both teachers and students but also exacerbates educational exclusion. Studies suggest that when educational stakeholders are satisfied with the available resources and support, their attitudes toward inclusive education become significantly more positive [40]. By contrast, the high costs associated with traditional special schools are inconsistent with resource conservation and sustainable development, underscoring the need to optimize resource allocation within inclusive education frameworks.

At a macro level, a well-developed teacher training system and a scientifically grounded evaluation framework are crucial for advancing inclusive education. While teachers generally support inclusive education, they often doubt their ability to teach effectively in inclusive classrooms and are reluctant to include students with special needs [41]. A lack of confidence and competence in curriculum design and inclusive teaching methods further impedes the implementation of inclusive practices [42]. Approximately 47% of pre-service teachers and 66% of in-service teachers felt that current teacher education provided insufficient effective preparation [43]. This issue is pervasive across regions, as evidenced by the challenges faced by Scottish teachers who struggle to implement inclusive practices due to insufficient systematic training [44]. Comprehensive teacher training not only enhances instructional skills but also significantly improves teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education and boosts their self-efficacy [45].

Equally important is the development of a rational and effective evaluation system. Narrow or inappropriate performance metrics can undermine inclusive education practices [46]. Evaluation standards should avoid setting overly idealistic goals that may lead to frustration, while also preventing teachers from eschewing inclusive education practices due to pressure from evaluation systems [47]. An effective evaluation framework should not only assess educational outcomes but also provide positive reinforcement for teachers’ growth and self-efficacy, creating a supportive environment for sustainable inclusive education development.

4.3.3. Micro-Level Implementation Basis

The effective implementation of inclusive education relies on stakeholders’ recognition and support for the potential of all students [48]. Learning difficulties should not be perceived solely as individual issues but as the result of interactions between students and their learning environments [49]. LDA topic analysis highlights that the “micro-environment” comprises key elements such as school climate, teacher attitudes and professional competence, parental involvement, and peer support. These factors significantly influence students’ academic outcomes and behavior in the classroom. For example, negative behaviors such as aggression, anxiety, or disengagement often arise from unmet needs within the learning environment. A positive school climate and supportive teacher attitudes foster greater student engagement and reduce behavioral disruptions, while negative environments can reinforce disruptive behavior, hindering both academic and social development.

Inclusive schools must transition from merely addressing individual needs to constructing inclusive educational ecosystems that adapt proactively to students’ diverse needs, fostering both academic and social development [50]. These ecosystems are crucial for providing emotional and social support to students with behavioral difficulties, helping them thrive in an inclusive environment [51]. For instance, using positive reinforcement techniques and creating structured opportunities for social interaction can significantly help students with behavioral issues adapt to inclusive settings [52]. Principals play a pivotal role in shaping an inclusive climate by fostering teacher professional development, forming diverse teaching teams, and supporting the implementation of inclusive practices [52,53].

Teachers are pivotal to removing barriers to inclusion and implementing inclusive education principles. Professional development is essential for equipping teachers with the knowledge and skills necessary to manage diverse student behaviors and promote inclusive practices [54]. Nevertheless, significant gaps remain [55]. Teacher attitudes—shaped by cultural and demographic factors—can either facilitate or hinder policy implementation [56]. Positive attitudes help foster collaborative teaching, cultivate an inclusive culture, and encourage the adaptation of teaching practices [57]. Conversely, negative attitudes may limit policy effectiveness and weaken student learning outcomes [58]. Teachers’ ability to manage student behavior effectively is critical to the success of inclusive education. When teachers receive adequate training in behavior management and inclusive teaching strategies, they are better equipped to address students’ behavioral challenges and foster an inclusive classroom environment. Teachers’ self-efficacy plays a vital role in shaping their attitudes toward inclusion, and improving it can promote a more positive perspective on inclusive education [59]. To effectively realize inclusion, teachers require structured preparation and ongoing training that develop inclusive teaching skills, positive attitudes, and digital competence—essential for supporting diverse learners through accessible and differentiated instruction [60].

In inclusive education settings, negative behaviors from students or parents are often cited as significant barriers to effective instruction. Such behaviors not only disrupt classroom dynamics but also have profound impacts on the growth and development of all students [61]. Behavioral difficulties, however, are often the result of unmet needs within the learning environment. When schools create supportive environments focusing on social and emotional learning, students are more likely to demonstrate positive behaviors and engage meaningfully in the learning process. Parents and peers, as the most immediate and frequent social support groups for students, play a critical role in overcoming barriers between schools and families, as well as among students. Studies indicate that while some parents are more accepting of students with behavioral disorders, they may remain hesitant toward those with mental disabilities, often expressing concerns about the potential impact of inclusion on their own children’s academic performance [62].

For students without special educational needs, learning alongside peers with such needs has minimal adverse effects and may even yield benefits, such as enhanced social attitudes, greater acceptance of differences, improved social cognition, and heightened self-awareness [63]. Students in inclusive setting are more likely to be accepted by peers, establish better social relationships, experience reduced feelings of loneliness, and exhibit fewer behavioral problems [64]. These benefits help students build and maintain positive peer relationships while supporting their psychological development and learning capacity [65].

After controlling for other factors, students in inclusive schools demonstrate higher academic achievement compared to those in special schools [66]. Active parental and peer engagement improves school–family interactions, reduces social prejudice, enhances socio-emotional competencies, and positively influences school climate and teacher morale.

4.3.4. Implementation Effects and Challenges

Research has highlighted that while inclusive education may not always achieve its desired outcomes [67], its commitment to advancing educational equity and social justice is clear. From the perspective of educational equity, inclusive education ensures equal learning opportunities and serves as a vital pathway toward fairer learning outcomes [68]. A meta-analysis covering 80 years of research found that students in inclusive settings outperform their peers in segregated environments, both academically and socially [69]. Furthermore, integrating students with special educational needs (SENs) into general classrooms does not negatively affect the academic performance of typically developing peers. In fact, it often results in positive developmental outcomes for all students [70]. A systematic review of 280 studies across 25 countries further confirmed the positive impact of inclusive education on the academic performance of all students [71].

From the standpoint of social justice, inclusive education emphasizes the equitable distribution of educational resources and provides a foundation for long-term development in higher education, employment, and quality of life. Students in inclusive settings tend to develop stronger social skills and achieve higher levels of social integration in adulthood [72]. Compared to students in special schools, those educated inclusively are 76% more likely to obtain professional and academic qualifications, with half attaining economic independence by the age of 30 [73].

Despite these theoretical and practical advantages, the implementation of inclusive education faces significant challenges. First, “micro-politics” within school settings and the complex dynamics of social networks create barriers to the adoption of inclusive practices [74]. Inclusive education is often just one of many competing priorities in schools, which must also navigate pressures from narrowly defined achievement goals and accountability-driven cultures. Moreover, the increasing demand for market-oriented approaches to public education, driven by neoliberal ideologies, makes it harder for schools to prioritize inclusivity [13].

Resource scarcity remains a central challenge in the effective implementation of inclusive education. Many regions lack the necessary infrastructure to support SEN students, including specialized assistive technologies for students with hearing or visual impairments. Additionally, there is a shortage of qualified teachers, and existing staff face time constraints that limit the sustainability of inclusive practices. Research indicates that although students with complex special needs represent less than 0.8% of a school’s total enrollment, teachers and administrators must dedicate up to 60% of their efforts to address these students’ needs, further exacerbating the human resource shortage [75].

Supporting SEN students in general education classrooms, under current conditions, often involves adapting individual lessons or integrating additional support within a largely unchanged traditional system. However, this approach differs significantly from a fully inclusive education model, which requires systemic reform—including equitable resource distribution, adapted curricula, and professional development grounded in inclusive pedagogy. Inclusive education is not simply about adding support within the general system, but about transforming that system to meet the diverse needs of all learners.

At present, the scope of professional development programs is insufficient to meet these demands [76], and resource allocation models are not yet designed to sustain the structural changes required for inclusion. Clarifying this distinction between general education as it exists and the systemic nature of inclusive education is essential to guiding long-term reform. Whether current models can evolve to support such a transformation remains a critical issue for the future development of inclusive education.

4.4. Framework Construction

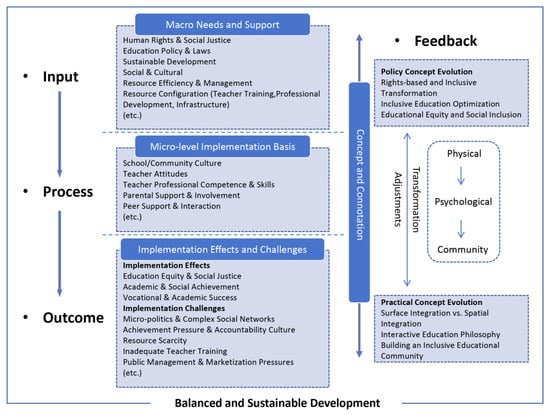

To address RQ3, we revisited the thematic content identified in previous sections. Drawing upon the input–process–outcome model proposed by Kyriazopoulou and Weber [77], this study constructs a multidimensional analytical framework (Figure 6). This model provides a systematic perspective on inclusive education by interweaving macro- and micro-level factors with feedback mechanisms, thereby offering theoretical support for understanding the implementation, effectiveness, and evolution of inclusive education.

Figure 6.

Conceptual framework for inclusive education research.

4.4.1. Input: Macro Needs and Support

The input dimension includes macro-level factors that drive the implementation of inclusive education and support educational practice. Human rights and social justice emphasize that every student, regardless of background or ability, is entitled to equal educational opportunities. Educational policies and legislation mandate structural reforms to promote inclusive approaches. SDG4 advocates for inclusive and equitable quality education, fostering balanced development across socioeconomic and environmental dimensions. Sociocultural factors play a key role by promoting mutual understanding and respect among students from diverse backgrounds. Finally, efficient resource management ensures the optimal allocation of funding, technology, instructional materials, and assistive devices, while teacher training, professional development, and infrastructure improvements are vital for effective implementation.

4.4.2. Process: Micro-Level Implementation Basis

The process dimension focuses on micro-level factors that determine the effectiveness of educational practice. School and community culture are crucial, as fostering an inclusive ethos promotes student interaction, mutual understanding, and a supportive learning environment for diverse needs. Teacher attitudes directly impact educational outcomes; an inclusive mindset and sensitivity to diverse learner needs are essential for success. Teacher expertise, enhanced through ongoing professional development, improves pedagogical strategies, particularly in addressing special educational needs and implementing differentiated instruction. Parental support and engagement are also vital for students’ academic and psychological development, while home–school cooperation boosts motivation and enhances outcomes. Finally, peer support, through mentoring, group activities, and cooperative learning, fosters students’ social competencies and emotional well-being.

It is important to recognize that macro-level inputs and micro-level practices are not isolated dimensions, but mutually reinforcing. Systemic issues such as funding shortages, insufficient training, or limited access to assistive technologies often constrain how inclusive strategies are implemented in classrooms. Even the most well-intentioned policies cannot succeed without corresponding support at the school level. Therefore, aligning high-level commitments with practical conditions is essential for the sustainable implementation of inclusive education.

4.4.3. Outcome: Implementation Effects and Challenges

The outcome dimension examines the effects and challenges of implementing inclusive education. Positive outcomes include educational equity and social justice, achieved by providing equal learning opportunities, eliminating barriers, and promoting social inclusion and fairness. Academic and social achievement are also key outcomes, with inclusive education improving students’ academic performance and social skills, particularly helping learners with special needs integrate and succeed in the long term. However, challenges remain. Micro-politics and complex social networks within schools can hinder inclusive practices. Achievement pressure and accountability cultures place additional burdens on institutions, while resource constraints, especially in specialized tools and teacher training, persist. Moreover, public management pressures and marketisation can limit the full development of inclusive education.

4.4.4. Feedback Mechanism: Concept Evolution and Feedback Loops

This study introduces a feedback mechanism to highlight the dynamic relationship between the evolution of inclusive education and its development. The model allows for interactive adjustments between policy and practice, keeping it adaptable. At the policy level, inclusive education has shifted from addressing special educational needs to embracing all learners, optimizing special education provisions, and pursuing broader goals of educational equity and social inclusion. At the practice level, it has evolved from physical integration in learning spaces to fostering interaction and a sense of community, ensuring that every student receives adequate support for holistic growth. The progression from “Physical” to “Psychological” to “Community” reflects a shift from passive compliance with policy mandates to active social commitment. These feedback loops enable educational systems to remain responsive to societal changes, sustaining equilibrium and the capacity to meet diverse learning needs.

5. Conclusions and Limitations

This study combines large-scale literature data with LDA topic modeling and manual coding to develop a comprehensive framework for inclusive education, based on the “input-process-outcome-feedback” (IPOF) cycle. The framework provides a theoretical understanding of inclusive education’s evolution, from policy formation to practical implementation. Methodologically, it offers a replicable, data-driven approach for structuring educational knowledge. From a practical standpoint, this study identifies critical bottlenecks in policy implementation and resource allocation, providing actionable insights for improving policy formulation and practice.

The findings contribute directly to advancing Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4), particularly in promoting inclusive, equitable, and quality education for all. By identifying key themes in inclusive education and proposing an actionable framework, this study offers policymakers and educators a robust tool for fostering inclusive educational practices that align with global sustainability objectives. The insights gained can help address the inequalities in education systems, ensuring that marginalized and vulnerable populations have access to quality education and lifelong learning opportunities.

Despite these contributions, this study has several limitations. First, LDA modeling could be enhanced by integrating more advanced natural language processing techniques, such as BERT or GPT models, to improve its semantic accuracy and topic coherence. Second, empirical validation through case studies, surveys, and experimental research is needed to confirm the robustness of the findings. Third, this study does not fully explore the influence of cultural contexts on inclusive education practices, suggesting the need for further cross-cultural comparative research.

Nonetheless, this study incorporates data from a range of non-English-speaking countries and Global South contexts, highlighting their unique contributions. While the dataset primarily reflects research from English-speaking countries, the inclusion of diverse regional perspectives enriches the IPOF framework. Due to technical and sample limitations, geographic bias is unavoidable, and the framework may reflect dominant paradigms from Anglophone contexts. However, it provides a balanced starting point for cross-contextual comparison and further adaptation to culturally distinct educational systems.

In conclusion, this study provides a systematic, data-driven framework for advancing the theory and practice of inclusive education, contributing to the broader goals of SDG 4. It lays the groundwork for refining inclusive education models and offers actionable recommendations for policymakers. Future research should prioritize empirical validation, particularly in low-resource or multilingual settings where inclusive education faces acute challenges. Testing the IPOF model in these contexts is essential to ensure its practical applicability and long-term global relevance.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su17093837/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Y. and T.W.; Methodology, C.Y. and T.W.; Software, C.Y.; Validation, Q.X.; Formal analysis, C.Y.; Investigation, Q.X.; Resources, Q.X.; Data curation, C.Y.; Writing—original draft, C.Y.; Writing—review and editing, T.W. and Q.X.; Visualization, C.Y.; Supervision, T.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gartner, A.; Lipsky, D.K. Beyond Special Education: Toward a Quality System for All Students. Harv. Educ. Rev. 1987, 57, 367–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorde, O.; Lapidot-Lefler, N. Sustainable Educational Infrastructure: Professional Learning Communities as Catalysts for Lasting Inclusive Practices and Human Well-Being. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Incheon Declaration: Education 2030: Towards Inclusive and Equitable Quality Education and Lifelong Learning for All—UNESCO Digital Library. 2016. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000233137 (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- UNESCO. A Guide for Ensuring Inclusion and Equity in Education—UNESCO Digital Library. 2016. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000248254 (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Blei, D.M.; Ng, A.Y.; Jordan, M.I. Latent Dirichlet Allocation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2003, 3, 993–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Hannigan, T.R.; Haans, R.F.J.; Vakili, K.; Tchalian, H.; Glaser, V.L.; Wang, M.S.; Kaplan, S.; Jennings, P.D. Topic Modeling in Management Research: Rendering New Theory from Textual Data. Annals 2019, 13, 586–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slee, R. The Irregular School: Exclusion, Schooling and Inclusive Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2011; ISBN 978-0-203-83156-4. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, S.; Singal, N. The Education for All and Inclusive Education Debate: Conflict, Contradiction or Opportunity? Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2010, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, I.; Woodcock, S. Inclusive Education Policies: Discourses of Difference, Diversity and Deficit. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2015, 19, 141–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göransson, K.; Nilholm, C. Conceptual Diversities and Empirical Shortcomings—A Critical Analysis of Research on Inclusive Education. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2014, 29, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ametepee, L.K.; Anastasiou, D. Special and Inclusive Education in Ghana: Status and Progress, Challenges and Implications. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2015, 41, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainscow, M.; Miles, S. Making Education for All Inclusive: Where Next? Prospects 2008, 38, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainscow, M.; Booth, T.; Dyson, A. Inclusion and the Standards Agenda: Negotiating Policy Pressures in England. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2006, 10, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messiou, K. Research in the Field of Inclusive Education: Time for a Rethink? Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2017, 21, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilholm, C.; Göransson, K. What Is Meant by Inclusion? An Analysis of European and North American Journal Articles with High Impact. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2017, 32, 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erten, O.; Savage, R.S. Moving Forward in Inclusive Education Research. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2012, 16, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Mieghem, A.; Verschueren, K.; Petry, K.; Struyf, E. An Analysis of Research on Inclusive Education: A Systematic Search and Meta Review. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2020, 24, 675–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artiles, A.J.; Kozleski, E.B.; Dorn, S.; Christensen, C. Chapter 3: Learning in Inclusive Education Research: Re-Mediating Theory and Methods with a Transformative Agenda. Rev. Res. Educ. 2006, 30, 65–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapp, A.C.; Corral-Granados, A. Understanding Inclusive Education—A Theoretical Contribution from System Theory and the Constructionist Perspective. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2021, 28, 423–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falagas, M.E.; Pitsouni, E.I.; Malietzis, G.A.; Pappas, G. Comparison of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar: Strengths and Weaknesses. FASEB J. 2008, 22, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornmann, L.; Daniel, H. What Do Citation Counts Measure? A Review of Studies on Citing Behavior. J. Doc. 2008, 64, 45–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Řehůřek, R.; Sojka, P. Software Framework for Topic Modelling with Large Corpora. In Proceedings of the LREC 2010 Workshop on New Challenges for NLP Frameworks, Valletta, Malta, 17–23 May 2010; ELRA: Paris, France, 2010; pp. 45–50. Available online: https://radimrehurek.com/gensim/ (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Sievert, C.; Shirley, K.E. LDAvis: A Method for Visualizing and Interpreting Topics. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Interactive Language Learning, Visualization, and Interfaces, Baltimore, MD, USA, 27 June 2014; pp. 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brantlinger, E. Using Ideology: Cases of Nonrecognition of the Politics of Research and Practice in Special Education. Rev. Educ. Res. 1997, 67, 425–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skidmore, D. Inclusion: The Dynamic of School Development: The Dynamic of School Development; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2004; ISBN 978-0-335-20481-6. [Google Scholar]

- Bines, H.; Lei, P. Disability and Education: The Longest Road to Inclusion. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2011, 31, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, A. UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Eur. J. Health Law 2007, 14, 273–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, L.M. Special Education for the Mildly Retarded—Is Much of It Justifiable? Except. Child. 1968, 35, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindqvist, G.; Nilholm, C.; Almqvist, L.; Wetso, G.-M. Different Agendas? The Views of Different Occupational Groups on Special Needs Education. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2011, 26, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florian, L. On the Necessary Co-Existence of Special and Inclusive Education. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2019, 23, 691–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qvortrup, A.; Qvortrup, L. Inclusion: Dimensions of Inclusion in Education. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2017, 22, 803–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.E.; Cosme, A.; Veiga, A. Inclusive Education Systems: The Struggle for Equity and the Promotion of Autonomy in Portugal. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfsteller, R.; Gregg, B. A Realistic Utopia? Critical Analyses of The Human Rights State in Theory and Deployment: Guest Editors’ Introduction. Int. J. Hum. Rights 2017, 21, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, K.; Caseau, D.; Stefanich, G.P. Teaching Students with Disabilities in Inclusive Science Classrooms: Survey Results. Sci. Ed. 1998, 82, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, M.; Chiu, B. Education for Sustainable Development as Peace Education. Peace Change 2009, 34, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhukova, O.; Platash, L.; Tymchuk, L. Inclusive Education as a Tool For Implementing the Sustainable Development Goals on the Basis of Humanization of Society. Probl. Ekorozw. 2022, 17, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shutaleva, A.; Martyushev, N.; Nikonova, Z.; Savchenko, I.; Kukartsev, V.; Tynchenko, V.; Tynchenko, Y. Sustainability of Inclusive Education in Schools and Higher Education: Teachers and Students with Special Educational Needs. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasianovych, H.; Budnyk, O. The Philosophical Foundations of the Researches of the Inclusive Education. J. Vasyl Stefanyk Precarpathian Natl. Univ. 2019, 6, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansour, T.; Bernhard, D. Special Needs Education and Inclusion in Germany and Sweden. Alter 2018, 12, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldan, J.; Schwab, S. Measuring Students’ and Teachers’ Perceptions of Resources in Inclusive Education—Validation of a Newly Developed Instrument. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2020, 24, 1326–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Martínez, Y.; Gárate-Vergara, F.; Marambio-Carrasco, C. Training and Support for Inclusive Practices: Transformation from Cooperation in Teaching and Learning. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İlik, Ş.; Sari, H. The Training Program for Individualized Education Programs (IEPs): Its Effect on How Inclusive Education Teachers Perceive Their Competencies in Devising IEPs. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 2017, 17, 1547–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Robinson, D. Effective Inclusive Teacher Education for Special Educational Needs and Disabilities: Some More Thoughts on the Way Forward. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 61, 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolfson, L.M.; Brady, K. An Investigation of Factors Impacting on Mainstream Teachers’ Beliefs about Teaching Students with Learning Difficulties. Educ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswald, M.; Swart, E. Addressing South African Pre-Service Teachers’ Sentiments, Attitudes and Concerns Regarding Inclusive Education. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2011, 58, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeskey, J.; Waldron, N.L. Professional Development and Inclusive Schools: Reflections on Effective Practice. Teach. Educ. 2002, 37, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquette, K.R.; Rieg, S.A. Stressors and Coping Strategies through the Lens of Early Childhood/Special Education Pre-Service Teachers. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2016, 57, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkas, M.S.; Simonsen, B.; Migdole, S.; Donovan, M.E.; Clemens, K.; Cicchese, V. Schoolwide Positive Behavior Support in an Alternative School Setting: An Evaluation of Fidelity, Outcomes, and Social Validity of Tier 1 Implementation. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 2012, 20, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddell, S. The Classification of Pupils at the Educational Margins in Scotland: Shifting Categories and Frameworks. In Disability Classification in Education; Florian, L., McLaughlin, M., Eds.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 109–128. [Google Scholar]

- Gibb, K.; Tunbridge, D.; Chua, A.; Frederickson, N. Pathways to Inclusion: Moving from Special School to Mainstream. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 2007, 23, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, J.; Pillay, H.; Tones, M.; Nickerson, J.; Carrington, S.; Ioelu, A. A Case for Rethinking Inclusive Education Policy Creation in Developing Countries. Comp. J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2016, 46, 906–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamran, M.; Siddiqui, S. Roots of Resilience: Uncovering the Secrets behind 25+ Years of Inclusive Education Sustainability. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, P.; Dyson, A.; Polat, F.; Hutcheson, G.; Gallannaugh, F. Inclusion and Achievement in Mainstream Schools. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2007, 22, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapidot-Lefler, N. Teacher Responsiveness in Inclusive Education: A Participatory Study of Pedagogical Practice, Well-Being, and Sustainability. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morningstar, M.E.; Benitez, D.T. Teacher Training Matters: The Results of a Multistate Survey of Secondary Special Educators Regarding Transition from School to Adulthood. Teach. Educ. Spec. Educ. 2013, 36, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avramidis, E.; Bayliss, P.; Burden, R. Student Teachers’ Attitudes towards the Inclusion of Children with Special Educational Needs in the Ordinary School. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2000, 16, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fluijt, D.; Bakker, C.; Struyf, E. Team-Reflection: The Missing Link in Co-Teaching Teams. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2016, 31, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guralnick, M.J. International Perspectives on Early Intervention: A Search for Common Ground. J. Early Interv. 2008, 30, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Denša, J.; Zurc, J. Perceptions of Stress Among Primary School Teachers Teaching Students with Special Educational Needs. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Jiménez, L.; Figueredo-Canosa, V.; Castellary López, M.; López Berlanga, M.C. Teachers’ Perceptions of the Use of ICTs in the Educational Response to Students with Disabilities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luiselli, J.K.; Putnam, R.F.; Handler, M.W.; Feinberg, A.B. Whole-school Positive Behaviour Support: Effects on Student Discipline Problems and Academic Performance. Educ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paseka, A.; Schwab, S. Parents’ Attitudes towards Inclusive Education and Their Perceptions of Inclusive Teaching Practices and Resources. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2019, 35, 254–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, J.; Persson, E. Students’ Perspectives on Raising Achievement through Inclusion in Essunga, Sweden. Educ. Rev. 2015, 68, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiener, J.; Tardif, C.Y. Social and Emotional Functioning of Children with Learning Disabilities: Does Special Education Placement Make a Difference? Learn. Disabil. Res. Pract. 2004, 19, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, S.F.N.; Alkin, M.C. Academic and Social Attainments of Children with Mental Retardation in General Education and Special Education Settings. Rem. Spec. Educ. 2000, 21, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myklebust, J.O. Diverging Paths in Upper Secondary Education: Competence Attainment among Students with Special Educational Needs. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2007, 11, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, P. Understanding Inclusive Education: Ideals and Reality. Scand. J. Disabil. Res. 2017, 19, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainscow, M. Promoting Inclusion and Equity in Education: Lessons from International Experiences. Nord. J. Stud. Educ. Policy 2020, 6, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh-Young, C.; Filler, J. A Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Placement on Academic and Social Skill Outcome Measures of Students with Disabilities. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2015, 47, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruijs, N.M.; Peetsma, T.T.D. Effects of Inclusion on Students with and without Special Educational Needs Reviewed. Educ. Res. Rev. 2009, 4, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hehir, T.; Grindal, T.; Freeman, B.; Lamoreau, R.; Borquaye, Y.; Burke, S. A Summary of the Evidence on Inclusive Education. Abt Associates; 2016. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED596134 (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Flexer, R.W.; Daviso, A.W.; Baer, R.M.; McMahan Queen, R.; Meindl, R.S. An Epidemiological Model of Transition and Postschool Outcomes. Career Dev. Except. Individ. 2011, 34, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myklebust, J.O.; Ove Båtevik, F. Economic Independence for Adolescents with Special Educational Needs. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2005, 20, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrington, S.; Robinson, R. Inclusive School Community: Why Is It so Complex? Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2006, 10, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, I.; Campos Pinto, P.; Pinto, T.J. Developing Inclusive Education in Portugal: Evidence and Challenges. Prospects 2020, 49, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella, C.S.C.; Forlin, C.; Lan, A.M. The Influence of an Inclusive Education Course on Attitude Change of Pre-service Secondary Teachers in Hong Kong. Asia-Pac. J. Teach. Edu. 2007, 35, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriazopoulou, M.; Weber, H. (Eds.) Development of a Set of Indicators for Inclusive Education in Europe; European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education: Odense, Denmark, 2009; ISBN 978-87-92387-48-6. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).