1. Introduction

Water management in Mexico is a pressing issue at the crossroads of environmental, social, and economic dynamics. This challenge is particularly acute in the Bajío region, a hub of agricultural and industrial activity that faces increasing pressure on its water resources. Guanajuato, as a key state within this region, exemplifies the broader struggles of balancing water allocation among competing sectors, addressing regional inequities, and ensuring sustainability in the context of climate change. These challenges highlight the need for an integrated approach to water governance that accounts for the socio-political dimensions shaping access and distribution.

Political ecology provides a robust framework for understanding the socio-political dimensions that highlight water management challenges in Guanajuato. This perspective transcends purely technical and hydrological approaches, focusing instead on the intersections of societal power dynamics, institutional arrangements, and economic priorities. Scholars such as Swyngedouw (2009) [

1] and Boelens et al. (2017) [

2] highlight how governance systems often prioritize the interests of dominant economic actors, such as agribusiness and manufacturing, while marginalizing small-scale stakeholders, rural communities, and environmental concerns.

In Guanajuato, these inequities are particularly evident in the unsustainable overexploitation of aquifers, where annual groundwater extraction exceeds natural recharge rates by more than 1000 million cubic meters, leading to severe declines in water tables, land subsidence, and arsenic and fluoride pollution [

3]. Efforts to regulate groundwater through mechanisms such as water markets, energy pricing, and Aquifer Management Councils have been undermined by entrenched power imbalances, which favor large water users and limit the participation of marginalized groups in decision-making processes [

2].

This systemic exclusion not only intensifies socio-economic disparities but also perpetuates the mismanagement of water resources. For example, policies aimed at improving irrigation efficiency have frequently prioritized subsidies for wealthier users while neglecting the needs of smaller farmers and indigenous communities [

4]. The political ecology lens underlines the need for the re-politicization of water governance in Guanajuato, emphasizing the integration of diverse stakeholder voices, the recognition of environmental justice, and the dismantling of inequitable institutional structures.

1.1. Purpose and Significance

This study examines how water governance in Guanajuato, Mexico, is shaped by institutional structures, socio-political dynamics, and power asymmetries, reinforcing systemic inequities in access and management. Using a political ecology framework, this research moves beyond conventional applications by integrating an empirical, multi-scalar analysis that connects governance fragmentation, stakeholder power imbalances, and environmental injustices with grounded, policy-oriented solutions. Through thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews and case study data, the study identifies governance failures while also examining local resistance strategies, participatory mechanisms, and institutional blind spots that perpetuate hydrosocial inequalities. Unlike previous studies that primarily apply political ecology as a diagnostic tool, this research advances its application by linking theoretical insights to actionable governance reforms, demonstrating how political ecology can inform tangible policy interventions. Guanajuato exemplifies governance challenges in Mexico’s semi-arid regions, offering a novel contribution by positioning local governance failures within broader hydrosocial transformations while proposing specific policy interventions on participatory decision-making, regulatory restructuring, and grassroots water management. By integrating critical theory with empirical stakeholder-driven analysis, this study strengthens the applicability of political ecology as a tool for governance reform, reinforcing its relevance for national and global water management debates.

1.2. Case Study Background: The State of Guanajuato

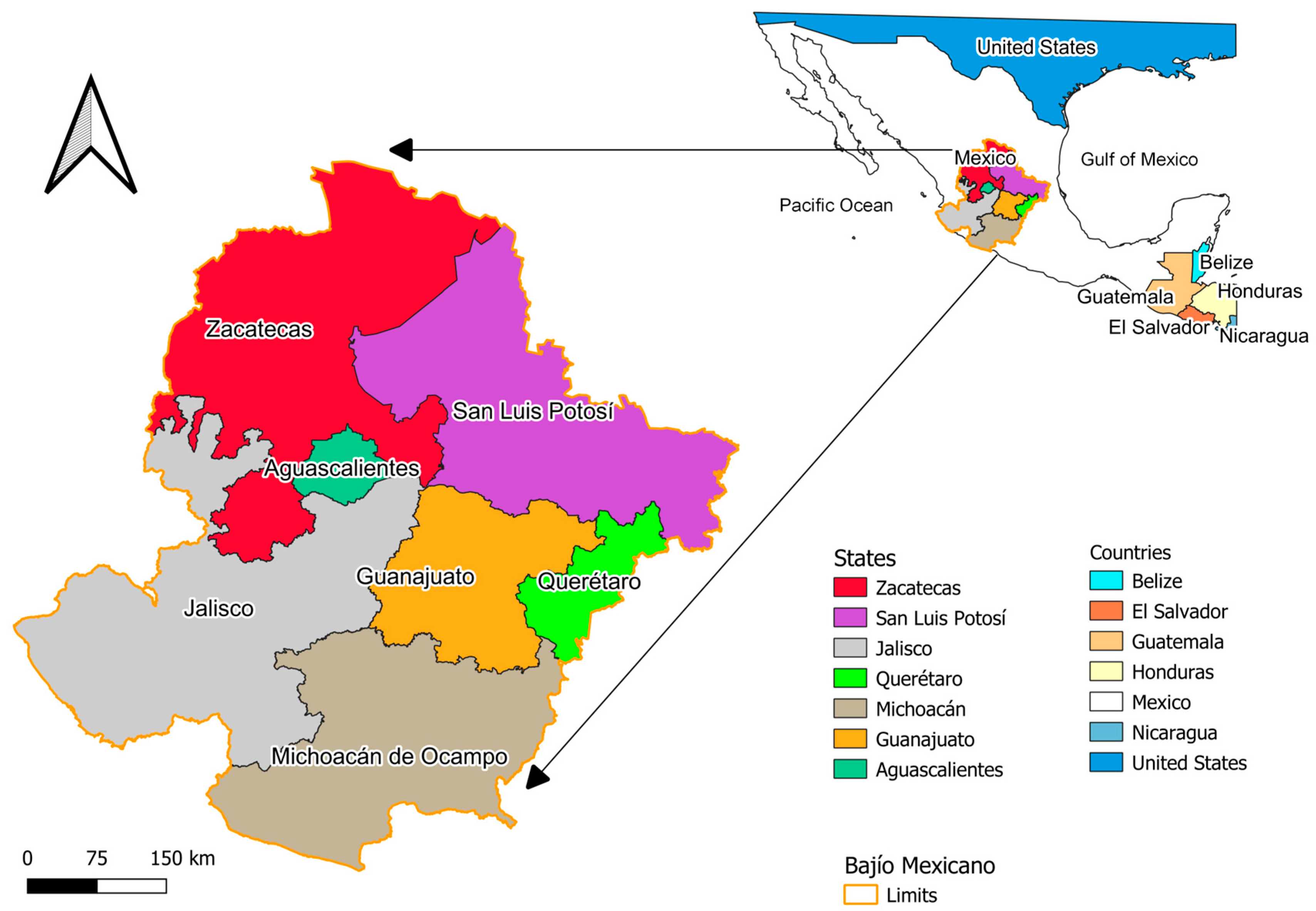

The state of Guanajuato was selected as the focal point of this study due to its strategic importance as a leading agricultural and industrial hub in Mexico’s Bajío region (

Figure 1). It exemplifies critical water management challenges, including severe groundwater depletion, escalating demand, and fragmented governance, which mirror broader national dynamics. Guanajuato’s unique socio-economic and environmental context provides a valuable lens to examine resource allocation and policymaking, offering insights directly aligned with the study’s objectives to investigate systemic inequities and governance challenges. As a microcosm of national challenges, this case highlights lessons and strategies that can inform water management reforms across Mexico, making it a compelling and illustrative focus for this study.

The State of Guanajuato: Contextual Overview

Guanajuato, situated in the central Bajío region of Mexico, embodies the complex challenges of water governance prevalent across the nation. Historically an agricultural and industrial powerhouse, the state’s rapid urbanization and economic expansion have intensified pressure on its water resources. With a population growing from 1.3 million in 1950 to over 6 million by 2020, cities such as León, Irapuato, Salamanca, and Celaya have become major urban centers, with rural areas continuing to experience severe water scarcity and socio-environmental marginalization [

5,

6]. Guanajuato contributes significantly to Mexico’s gross domestic product, ranking as the sixth-largest state economy; however, this economic growth has prioritized industrial and commercial water use over equitable distribution and sustainability [

7,

8].

The state’s semi-arid climate, with an average annual precipitation rate ranging between 450 mm and 500 mm, situates it within the upper limit of semi-arid regions based on FAO 2006 classifications [

9,

10,

11]. This fact places Guanajuato in a vulnerable hydrological position, contrasting sharply with wetter regions such as Tabasco and exacerbating pressures on already overexploited aquifers. Over 99% of domestic water supply and a substantial portion of agricultural and industrial demand depend on groundwater, leading to critical overextraction, declining water quality, and rising instances of saline intrusion and high fluoride concentrations, disproportionately affecting rural communities and creating serious public health issues [

5,

12,

13].

For example, the Río Turbio, one of the state’s most critical watercourses, is heavily polluted by untreated industrial and domestic wastewater, further diminishing water availability for human and ecological use [

6,

14,

15,

16]. Simultaneously, governance frameworks remain fragmented, characterized by overlapping institutional responsibilities and weak enforcement mechanisms that fail to effectively regulate water consumption and protect critical resources [

17,

18]. This institutional disarray exacerbates inequities, as rural and marginalized communities are systematically excluded from decision-making processes, which heavily favor urban and industrial priorities [

19,

20].

Efforts to address these governance challenges are further complicated by climate change, which threatens the reliability of key water infrastructure such as the Solís Dam, a critical water source for both urban and agricultural needs [

21]. There is an urgent need for adaptation measures, including integrated groundwater management, policy reform, and stakeholder inclusion in decision-making, to ensure the long-term resilience and equitable management of Guanajuato’s water systems [

6,

22].

The situation in Guanajuato exemplifies the intersection of socio-political, economic, and environmental pressures that define water governance challenges in semi-arid regions. This case offers valuable insights for addressing systemic inequities and fostering sustainable management practices, not only within Mexico but also in comparable water-stressed regions globally [

5,

6,

7].

1.3. Structure of the Study

This study is structured to provide a comprehensive analysis of water governance challenges in Guanajuato through the lens of political ecology. In the Introduction, the socio-political and environmental context is established, emphasizing governance fragmentation, aquifer overexploitation, and socio-economic disparities as key challenges shaping water management in the region. In the case study background section, an overview of Guanajuato’s water governance landscape is presented, outlining institutional, economic, and environmental factors contributing to resource mismanagement. The methodology integrates the theoretical framework, which expands on political ecology, defining its core principles and explaining how it identifies the systemic drivers of water inequities, power asymmetries, and governance failures. In this section, the results of expert interviews and thematic content analyses are also presented, structured around a coding framework to examine governance structures, stakeholder power relations, and socio-environmental conflicts. The interview process, participant distribution, and ethical considerations are explicitly detailed, ensuring transparency in data collection and analysis.

The findings and discussion illustrate how institutional weaknesses and governance asymmetries perpetuate water access disparities, favoring industrial and agribusiness sectors over marginalized communities. Additionally, the results of this study highlight the environmental consequences of governance failures, such as aquifer depletion, water contamination, and ineffective enforcement mechanisms. The discussion explicitly links empirical findings to political ecology concepts, reinforcing the theoretical and analytical contributions of the study. A dedicated recommendations section outlines policy and governance reforms, emphasizing the need for equitable water allocation, participatory decision-making, and financial support for grassroots water management initiatives. Lastly, in the Conclusion section, the study’s contributions are synthesized, linking regional governance challenges to broader discussions on water justice, sustainability, and hydrosocial governance.

2. Materials and Methods

A qualitative research design grounded in political ecology is employed in this study to examine water governance in Guanajuato. Our literature review, conducted using Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar, focused on political ecology, water governance, and socio-environmental conflicts, with peer-reviewed articles and policy reports selected based on relevance, empirical scope, and conceptual contribution. Key search terms included “political ecology of water”, “hydrosocial cycle”, “water governance Mexico”, and “institutional fragmentation water management”. This review helped inform the development of the interviews and case study analysis. Using 25 semi-structured interviews, a structured coding framework was applied to analyze governance failures, power asymmetries, and resistance strategies. Through content and comparative analysis, interview data were triangulated with policy documents and case study findings, offering a rigorous assessment of governance challenges and pathways to sustainability.

2.1. Theoretical Framework: Political Ecology

In this study, political ecology is adopted as the central analytical framework to critically examine the socio-political, economic, and institutional dimensions shaping water governance challenges in Guanajuato. Political ecology deconstructs dominant water governance paradigms by revealing how governance failures, power asymmetries, and socio-environmental injustices shape hydrosocial relations and resource mismanagement [

23,

24]. Rather than treating water crises as purely technical or hydrological issues, political ecology emphasizes that access, control, and conflicts over water are deeply embedded in historical, political, and economic struggles [

1,

25,

26,

27].

One of the core contributions of political ecology is its analysis of water conflicts as ecological distribution conflicts, in which environmental burdens and benefits are unevenly distributed across social groups, often following lines of economic and political power [

24,

28]. These conflicts are not simply about scarcity but about who has the power to access and manage water and who bears the socio-environmental costs of overexploitation and contamination. In Guanajuato, agribusiness and industrial expansion have restructured water governance, prioritizing economic productivity over environmental sustainability and equitable access [

29,

30]. This governance model has resulted in increasing restrictions for rural communities while enabling large-scale economic actors to monopolize groundwater resources [

31].

2.1.1. The Hydrosocial Cycle and Power Relations

A key concept in political ecology is the hydrosocial cycle, which challenges conventional hydrological approaches by framing water as a co-produced entity shaped by governance structures, economic imperatives, and cultural practices [

32]. Water is not merely a natural resource but a politically mediated element that reflects the interests and struggles of different actors [

1]. In Guanajuato, irrigation-intensive agribusiness and industrial users dictate water allocation, with smallholder farmers and rural communities facing reduced access and increasing scarcity [

33]. Institutional arrangements systematically exclude these marginalized groups from decision-making processes, reinforcing existing power imbalances in water governance [

25].

2.1.2. Water Conflicts as Ecological Distribution Conflicts

Rodríguez-Labajos and Martínez-Alier [

24] highlight water conflicts as paradigmatic cases of ecological distribution conflicts, where access, control, and environmental risks are unevenly distributed. These conflicts emerge due to competing demands between industrial, agricultural, and domestic users, often reflecting broader patterns of socio-environmental inequality. Guanajuato exemplifies this dynamic, where groundwater depletion and contamination result from industrial and agricultural overuse, disproportionately affecting small-scale farmers and rural populations. Privatization, water banking, and market-based allocation mechanisms have further exacerbated these conflicts, reinforcing a model that prioritizes economic efficiency over social equity [

25,

26].

The aforementioned authors [

24] provide a systematic classification of water conflicts, illustrating how disputes emerge at different stages of water use:

Extraction conflicts, where agribusiness and industrial users compete with local communities over groundwater access.

Transport and trade conflicts, where water infrastructure projects such as inter-basin transfers or hydroelectric dams generate displacement and social opposition.

Post-use contamination conflicts, where industries externalize environmental costs by polluting aquifers, rivers, and lakes, disproportionately affecting marginalized populations.

2.1.3. Resistance Movements and Alternative Governance Models

One of the key contributions of political ecology is its emphasis on social resistance and grassroots governance alternatives. Water conflicts are not only about scarcity but also about struggles for environmental justice, legal recognition, and participatory governance [

24]. Grassroots organizations, smallholder irrigation collectives, and environmental advocacy groups in Guanajuato have increasingly mobilized against corporate water grabs and extractive governance models [

23,

30]. These movements challenge neoliberal water policies, advocating instead for democratic governance, community-based water management, and legal recognition of water as a common good [

25].

2.1.4. Political Ecology as a Transformative Framework

Political ecology not only critiques governance failures but also serves as a transformative framework for rethinking water management in more just and sustainable ways. It calls for the dismantling of exclusionary governance structures, integrating ecological and social considerations into policymaking, and embedding environmental justice into water governance [

23,

24]. By linking local struggles to broader political and economic structures, it provides a framework for understanding how global water governance trends shape local hydrosocial relations [

25]. This approach ultimately balances socio-economic equity with ecological sustainability, fostering just and resilient water governance models that transcend Guanajuato’s case and offer insights for other semi-arid regions facing similar crises.

2.2. Expert Interviews

Semi-structured interviews with experts formed a central pillar of this research, offering valuable insights into the socio-political, economic, and environmental dimensions of water governance in Guanajuato. A total of 25 participants were engaged primarily in the last quarter of 2023 and the first two quarters of 2024, representing a diverse range of perspectives to ensure a well-rounded understanding of the challenges and opportunities in water management. Given the iterative nature of the interviews, where questions were revisited and refined based on emerging insights, the total number of interviews conducted exceeded 25. Participants included academic and research professionals, government officials, agricultural producers, community advocates, and local residents, reflecting the multiplicity of perspectives shaping the water governance landscape (

Table 1). However, the number of participants varied across categories due to availability constraints and the sensitive nature of the topic. While all interviewees initially agreed to participate voluntarily, some declined further engagement due to the critical nature of the governance issues discussed. Despite these variations, the sample ensured representation across key stakeholder groups. The higher representation of government officials reflects their central role in shaping water policies and institutional decision-making. The interview questions posed to the participants are provided in

Appendix A.

It is important to note that the sample size of 25 participants, while relatively small, was designed as an initial fieldwork effort to provide a focused and illustrative perspective on water governance dynamics in Guanajuato. This approach ensures the inclusion of diverse viewpoints, capturing insights from stakeholders who actively shape and are directly impacted by water management practices. In addition to addressing the primary objectives of the study, through this initial fieldwork, the aim was to establish relationships and build a foundation of trust with the participants, a critical aspect of qualitative research [

34,

35,

36]. Trust is essential for fostering open dialog and obtaining richer, more nuanced data [

37,

38]. This effort not only enhances the validity of the findings but also lays the groundwork for future, more extensive research collaborations.

The interviews followed an iterative process, characterized by the refinement and repetition of questions based on emerging insights [

39,

40]. This approach enabled a deeper exploration of key themes and ensured that the data captured accurately represented the complexities of the issues at hand. In this context, the iterative interviews were not merely a data collection tool but also an analytical method [

41,

42]. By revisiting participants with refined questions informed by earlier responses, it was possible to probe deeper into critical aspects such as power dynamics, institutional barriers, and stakeholder interactions. This repetition and adjustment allowed for the validation of the initial findings while uncovering nuanced dimensions of the phenomenon under study [

43,

44].

The iterative process was particularly valuable in understanding the interplay between governance structures and local realities. It facilitated a dynamic dialog with participants, ensuring that their experiences and perspectives were not only captured but also contextualized within the broader socio-political framework of water governance [

45]. As such, these interviews provided a rich foundation for analyzing systemic challenges and identifying actionable strategies to address water management issues in Guanajuato.

2.3. Interview Design and Process

The interviews were designed to explore five critical dimensions of water governance:

Governance Challenges: Examining institutional fragmentation and the gaps in policy enforcement.

Economic Pressures: Analyzing the competing demands of industrial and agricultural water use.

Social Equity: Identifying disparities in water access between urban and rural populations.

Environmental Sustainability: Understanding the consequences of aquifer depletion and pollution on ecosystems.

Community Resilience: Exploring community-driven initiatives to address water scarcity and promote equitable policy advocacy.

The interviews were conducted in a semi-structured format to allow flexibility while maintaining a focus on these critical themes. The conversations were recorded, transcribed, and anonymized to ensure ethical practices and protect participant confidentiality. This approach enabled open and meaningful discussions, providing valuable insights into the socio-political dynamics of water governance in Guanajuato.

2.4. Qualitative Data Analysis

To conduct a qualitative data analysis, a structured thematic approach was followed, directly informed by political ecology’s key analytical categories [

23,

24,

25]. Given the complexity of water governance in Guanajuato, a manual coding process was employed, facilitated by Microsoft Word and Excel, ensuring a systematic and transparent examination of interview data. To explicitly integrate political ecology into the analysis, thematic coding was guided by three core analytical dimensions, which structured the interpretation of governance structures, power relations, and socio-environmental conflicts (see

Table 2).

- ❖

Thematic Analysis and Coding Framework

Interview transcripts were manually coded, identifying recurring themes related to governance structures, socio-political disparities, and community resilience.

Coding was conducted in two phases as follows:

- ○

Initial coding: Identification of raw themes and patterns.

- ○

Categorization: Grouping of themes into broader political ecology categories (e.g., hydrosocial cycle, power asymmetries, and environmental justice).

The data were then organized in an Excel spreadsheet, allowing for structured classification and systematic comparison across interviews.

- ❖

Operationalizing Political Ecology in Data Analysis

To apply political ecology as an analytical tool, three key research dimensions structured the thematic analysis:

Governance Structures and Institutional Power Relations

- ○

How governance decisions are made, which actors hold decision-making authority, and how institutions enforce (or fail to enforce) regulations. Example: Identifying governance fragmentation and regulatory failures in interview responses from policymakers and water managers.

Power Asymmetries and Socio-Environmental Inequities

- ○

How water access is distributed unequally, who benefits from governance decisions, and who is excluded from decision-making processes. Example: Coding statements from smallholder farmers regarding restricted water access compared to agribusiness interests.

Environmental Justice and Resistance Strategies

- ○

How marginalized communities contest water governance decisions and what alternative governance models exist. Example: Identifying discourse around grassroots resistance movements and community-led water management initiatives.

These categories structured the coding framework, ensuring that political ecology was systematically applied rather than used as a general conceptual lens.

- ❖

Comparative Analysis and Triangulation

The coded interview data were cross-referenced with policy documents to validate governance patterns and identify points of convergence and contradiction. This triangulation method ensured the reliability of the findings and highlighted discrepancies between institutional policies and on-the-ground realities.

- ❖

Narrative Development and Pattern Identification

The final step involved identifying broader socio-environmental patterns and integrating perspectives from diverse actors (government officials, water managers, and community representatives). The findings were structured into a cohesive analytical narrative, illustrating how political ecology concepts manifest in Guanajuato’s water governance conflicts.

The coding framework used for thematic classification is detailed in

Table 2, demonstrating how political ecology’s analytical dimensions were systematically applied to the dataset.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

This study adhered to rigorous ethical research standards, ensuring the protection of participants’ rights, privacy, and informed consent. As there are no formal Institutional Review Board requirements within the affiliated institution, ethical guidelines were followed in accordance with international research standards for qualitative studies. All participants provided oral informed consent, which was recorded for documentation purposes. They were explicitly informed that their contributions would be analyzed qualitatively and used solely for academic research, with no personal or sensitive data disclosed. To ensure participant confidentiality, all interview data were fully anonymized, and no identifying information was included in the analysis [

46,

47,

48]. Furthermore, emphasis was placed on amplifying the voices of marginalized communities disproportionately affected by water scarcity, ensuring that the findings represent a diverse range of experiences and perspectives.

3. Results

The results are organized to align with the methodological framework of the study. First, the principles of political ecology are introduced to provide a theoretical foundation, providing an explanation of the socio-political dynamics shaping water governance in Guanajuato. Subsequently, findings from the interviews conducted with the study participants are presented, categorized into five critical dimensions: governance challenges, economic pressures, social equity, environmental sustainability, and community resilience. This structure ensures a logical flow, linking theoretical insights with empirical evidence to highlight both systemic issues and localized impacts.

3.1. Political Ecology and the Dynamics of Water Governance in Guanajuato

The political ecology framework emphasizes the interconnectedness of power, resource allocation, and environmental sustainability, situating governance failures within broader hydrosocial dynamics. By examining systemic inequalities, institutional fragmentation, and socio-environmental consequences, the study findings highlight how economic priorities often override equity and sustainability principles. Insights drawn from expert interviews across government, industry, agriculture, and community sectors demonstrate how these dynamics perpetuate resource disparities and environmental degradation, offering a deeper understanding of Guanajuato’s water management challenges.

3.1.1. Power Structures and Economic Priorities

The dominance of agribusiness and industrial actors emerged as a central theme in the region’s water governance challenges. These sectors, strengthened by their significant influence over resource allocation, often prioritize their economic interests at the expense of smaller agricultural producers and rural communities. As one state-level policymaker explained, “Water policies tend to favor the sectors that generate revenue, leaving smaller stakeholders struggling to secure even minimal access”. This power imbalance perpetuates inequities in resource distribution, marginalizing less powerful actors while favoring large-scale economic interests. Political ecology underscores how these disparities are deeply rooted in systemic governance structures that prioritize economic growth over equitable access.

3.1.2. Institutional Fragmentation and Regulatory Gaps

Institutional fragmentation poses a significant challenge to effective water governance in Guanajuato. Experts frequently identified overlapping responsibilities among municipal, state, and federal institutions as a primary obstacle. A senior government official remarked, “Institutional fragmentation allows for inconsistent application of policies”, highlighting the lack of coordination in critical areas such as groundwater regulation. Weak enforcement mechanisms exacerbate these issues, with unchecked groundwater extraction described as “unsustainable” by several participants. Political ecology situates these regulatory gaps within a broader context of governance failures, linking institutional weaknesses to resource mismanagement.

3.1.3. Socio-Political Inequalities in Resource Access

Disparities in water access between urban and rural areas further illustrate the socio-political inequalities embedded in Guanajuato’s governance framework. While urban centers receive priority in resource distribution due to their economic and political influence, rural communities face limited infrastructure and unreliable access. A community organizer emphasized, “Rural areas are not just under-resourced; they are systematically excluded from decision-making processes”. This exclusion perpetuates inequalities by denying rural populations the institutional support necessary to advocate for their needs. Political ecology reveals how these disparities reflect broader structural inequities that prioritize urban and industrial interests.

3.1.4. Environmental Consequences of Governance Failures

Environmental degradation in Guanajuato is closely tied to governance failures. Practices such as aquifer overexploitation and pollution from industrial and agricultural activities contribute to declining water quality and availability. The academic experts noted, “Aquifer depletion is not just a hydrological issue; it’s a governance problem rooted in the prioritization of short-term economic gains over sustainable practices”. These environmental impacts disproportionately affect marginalized rural communities, exacerbating socio-economic vulnerabilities and reflecting a broader failure to integrate environmental sustainability into governance structures.

3.1.5. Toward Equity in Governance

A consistent theme across the interviews was the need for adaptive and participatory governance reforms. Academics and government experts emphasized that addressing water inequities requires not only policy changes but also a fundamental rethinking of decision-making processes. As one policy analyst observed, “Addressing inequities requires not just policy reforms but a rethinking of how decisions are made”. Greater integration of marginalized voices and transparent decision-making processes were identified as critical to bridging the gap between urban and rural stakeholders. Political ecology highlights the transformative potential of participatory governance in promoting equity and sustainability.

3.2. The Case Study’s Significant Findings

Guanajuato offers a vivid illustration of complex water governance challenges where industrial growth, export agriculture, and urbanization strain resources amid governance challenges and environmental vulnerabilities. Expert interviews revealed the socio-political and environmental dynamics driving water scarcity and inequities, offering insights into broader national issues and the lived realities of affected communities.

3.2.1. Governance Challenges: Institutional Fragmentation and Policy Enforcement Gaps

A recurring issue across interviews was the fragmented governance structure of water management in Guanajuato. Participants described a “patchwork of overlapping responsibilities” where municipal, state, and federal authorities often work with cross-purposes, undermining effective policy enforcement. A municipal official noted the absence of coordination in enforcing water rights and addressing overuse, while an agribusiness representative admitted that lax oversight allowed companies to extract beyond legal limits. These gaps perpetuate resource mismanagement and exacerbate water scarcity, reflecting broader national governance issues. Participants highlighted the urgent need for streamlined institutional frameworks to ensure coherent and accountable decision-making.

3.2.2. Economic Pressures: Competing Demands of Industrial and Agricultural Water Use

Economic interests heavily influence water policy in Guanajuato, as stakeholders from agribusiness and industry leverage their economic power to secure favorable water allocations. Agribusinesses catering to export markets and expanding manufacturing sectors exert significant pressure on groundwater resources. Farmers and industrial leaders acknowledged that aquifer extraction rates far exceed natural recharge capacities, a trend a local water authority official referred to as “a race against time”. Policymakers admitted that economic contributions from these sectors often take precedence over social and environmental considerations, leading to decisions that prioritize short-term economic gains at the expense of long-term sustainability.

3.2.3. Social Equity: Disparities in Water Access Between Urban and Rural Populations

The interview answers revealed stark inequities in water access between urban centers and rural communities. Urban areas such as León benefit from relatively well-developed infrastructure; in comparison, rural villages often struggle with limited or unreliable water supplies. Community advocates described how rural agricultural productivity is hampered by competition from nearby industrial zones, which “always seem to get priority” in water allocation. This urban–rural divide exemplifies systemic inequities in resource distribution, where infrastructure investments and policy decisions disproportionately favor urban economic hubs, leaving marginalized rural communities vulnerable to water insecurity.

3.2.4. Environmental Sustainability: Aquifer Depletion and Pollution

Environmental degradation emerged as a significant concern in the interviews. Excessive groundwater extraction has led to aquifer depletion, while industrial discharges and pesticide run-off from intensive agriculture have severely contaminated local water sources. Environmental advocates referred to this pollution as “a slow poisoning”, impacting ecosystems and human health alike. Despite the existence of environmental regulations, weak enforcement has allowed these problems to persist. The cumulative effects of aquifer depletion and water pollution further exacerbate water pressures in the region, jeopardizing both environmental and human well-being.

3.2.5. Community Resilience: Local Adaptation and Advocacy Initiatives

Amidst these challenges, examples of community resilience and local adaptation stood out. Grassroots groups have implemented creative solutions to mitigate water scarcity, such as rainwater harvesting systems and local conservation initiatives. One community advocate emphasized the importance of “bottom-up solutions in the absence of top-down support”, illustrating how collective action can address water inequities. However, these initiatives remain isolated and underfunded, with limited institutional support to scale them effectively. Participants stressed the need for greater investment in community-driven approaches and the integration of local voices into policymaking processes to foster equitable and sustainable water management.

4. Discussion

Water governance challenges in Guanajuato are deeply connected with socio-political power dynamics, institutional fragmentation, and environmental degradation. The disproportionate influence of the industrial and agribusiness sectors has led to governance frameworks that systematically prioritize economic interests over equitable access and sustainability. These findings align with broader patterns observed in semi-arid regions globally, where hydrosocial power asymmetries and weak institutional frameworks exacerbate water access inequities and ecological vulnerabilities [

1,

18,

24,

25]. By systematically applying political ecology concepts in the analysis, the findings of this study demonstrate how governance structures, decision-making hierarchies, and institutional gaps shape the region’s water conflicts, reinforcing the structural nature of water mismanagement.

A critical insight of this study is the role of institutional fragmentation and governance asymmetries in perpetuating inefficiencies. Thematic coding of interviews and policy documents reveals how overlapping responsibilities among federal, state, and municipal institutions create regulatory blind spots, fostering elite capture of water resources and limiting community participation in decision-making. This fragmentation weakens the enforcement of water policies, particularly in regulating aquifer overexploitation, mirroring governance challenges observed in Chile and Brazil, where centralized decision-making often neglects regional disparities [

3,

7,

14,

28,

49]. Power asymmetries also manifest in the differential enforcement of regulations, where industrial and agribusiness actors benefit from lax oversight, while smallholder farmers and marginalized communities face restrictions and limited access. Strengthening institutional capacity and fostering multi-scalar governance approaches are essential for addressing these structural weaknesses and promoting sustainable water management practices.

The environmental consequences of these governance failures are profound, with overexploited aquifers, declining water quality, and pollution from industrial discharge serving as clear indicators of an unsustainable model. For instance, the case of Río Turbio illustrates how the lack of enforcement and weak governance mechanisms enable industrial pollution to persist, disproportionately affecting rural and marginalized communities [

15,

24]. Similarly, findings from other studies involving the Río Turbio Basin have been published, where fragmented governance and unchecked industrial expansion have exacerbated water insecurity and social conflicts, underscoring the urgent need for regulatory reform and integrated management strategies [

16]. Moreover, similar governance challenges in Guanajuato have been analyzed through the lens of complexity theory, emphasizing the interplay between institutional fragmentation, jurisdictional overlaps, and socio-environmental risks, highlighting the urgent need for adaptive, multi-scalar governance approaches [

50]. Addressing these issues therefore requires not only stricter regulatory enforcement but also a shift toward governance frameworks that integrate environmental justice principles. In this regard, lessons from participatory governance models in Brazil’s basin committees suggest that inclusive decision-making structures can help balance environmental, social, and economic priorities, offering a valuable pathway for reform [

6,

11,

23,

28].

The qualitative analytical approach employed in this study—grounded in political ecology—played a vital role in capturing nuanced socio-political realities. While the sample size was limited, the structured coding framework (

Table 2) enabled a systematic examination of governance failures, power asymmetries, and environmental justice dynamics. This approach revealed how governance asymmetries translate into tangible socio-environmental inequalities, disproportionately affecting marginalized communities and reinforcing historical patterns of exclusion. The identification of resistance strategies in the interview data further illustrates how affected communities mobilize against hydrosocial injustices, actively contesting extractive governance models through legal, institutional, and grassroots mechanisms [

4,

8,

25].

5. Recommendations

To address the structural governance challenges identified in this study, key policies and institutional reforms are necessary. Regulatory frameworks must be strengthened to ensure that water allocation prioritizes equitable access rather than favoring industrial consumption. Stricter enforcement mechanisms, greater transparency in decision-making, and participatory governance models are essential to integrating marginalized communities into water management processes.

Economic policies must also be reformed. Current water allocation policies disproportionately benefit industrial and agribusiness sectors, often at the expense of rural livelihoods and small-scale agriculture. Implementing economic incentives for sustainable water use in industry, such as tiered pricing structures and environmental accountability measures, could promote responsible consumption. Simultaneously, increased financial support for rural water management and smallholder agriculture is needed, ensuring that groundwater depletion and contamination do not further exacerbate socio-economic disparities.

Targeted funding for grassroots water management initiatives is critical to strengthening local adaptive capacities. Supporting community-led conservation strategies, decentralized water management models, and participatory decision-making frameworks would help in enhancing resilience in rural areas. Additionally, adopting equitable policy frameworks from international case studies can serve as a model for more inclusive water governance, integrating successful participatory and rights-based management approaches.

Lastly, a restructured approach to environmental justice is necessary, ensuring that legal and institutional mechanisms address socio-environmental disparities in water access. These reforms would enhance governance accountability, promote sustainability, and create a more equitable distribution of water resources in Guanajuato and other semi-arid regions.

6. Conclusions

The authors of future studies should develop these findings by further examining vulnerability, resilience, and adaptive governance mechanisms in response to climate change and socio-economic transformations. By applying a political ecology framework, through this study, it was possible to highlight the structural drivers of water inequities, demonstrating how fragmented governance, power asymmetries, and environmental degradation shape water access and management in Guanajuato. These patterns are not unique to the region but reflect broader governance challenges across Latin America and other water-stressed areas. The study’s findings emphasize the need for policy reforms that integrate environmental justice, equitable water allocation, and participatory governance models. By explicitly linking empirical data to theoretical debates on political ecology and hydrosocial governance, this study contributes to global water governance discourse, reinforcing the urgent need for transdisciplinary approaches to sustainability, governance, and water justice.