Sustainable Heritage Planning for Urban Mass Tourism and Rural Abandonment: An Integrated Approach to the Safranbolu–Amasra Eco-Cultural Route

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Data collection and analysis,

- Development of the eco-cultural route proposal,

- Stakeholder participation to ensure inclusivity and viability,

- Overall assessment and policy recommendations.

- Geographic Information System (GIS): It facilitates data collection for 84 sites through crowdsourcing field studies, with sites’ data being analyzed according to five indicators and ratings being assigned to each site’s indicators.

- Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP): The 5 indicators used in GIS analysis are weighted through surveys using the Saaty scale (1–9) to identify tourist preferences in the field.

- Clustering: Based on the normalized ratings for each site’s 5 indicators obtained from GIS and the indicator weights obtained from AHP, the sites are clustered using Self-organizing Map (SOM), which is a neural network algorithm. According to their similar characteristics, site potential levels (high, medium, and low) are then determined.

- SWOT Analysis: A comprehensive analysis of internal and external factors regarding the proposed eco-cultural route with stakeholders, and data (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) are obtained to develop strategies.

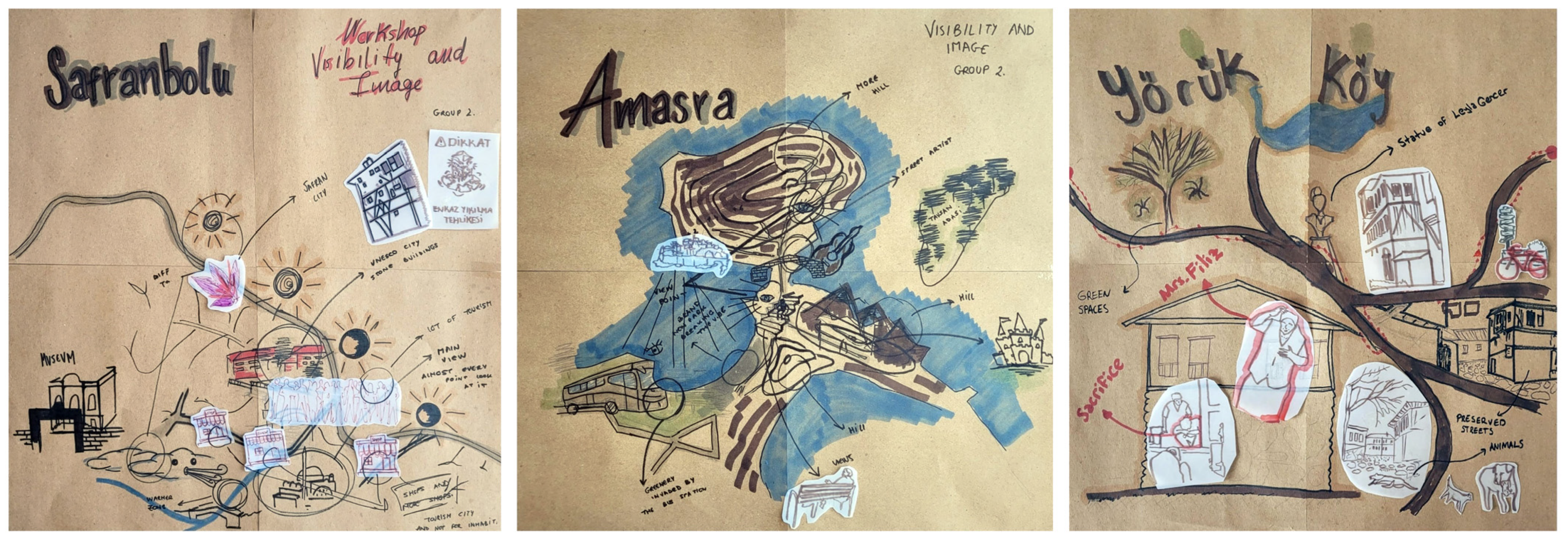

- Charrette: The data obtained through GIS, AHP, clustering, interviews, and SWOT analysis are evaluated using multidisciplinary workshops, the potential impacts of the eco-cultural route are discussed, and key strategies for planning are developed.

2.1. Data Collection

2.1.1. Documents of Historical Travelers

2.1.2. Field Study

2.1.3. Stakeholders

2.2. Data Analysis

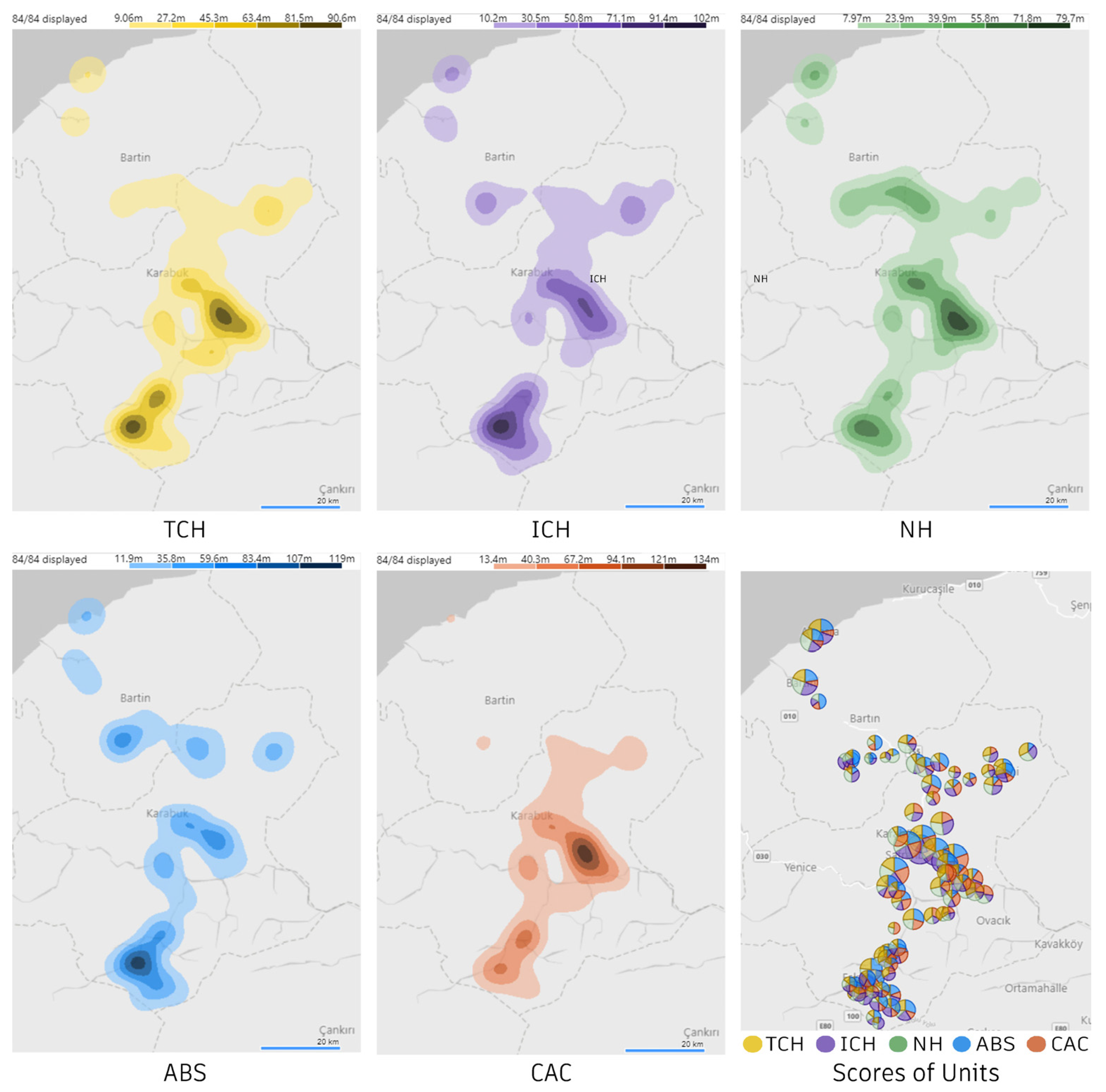

2.2.1. Data Management and Spatial Mapping at GIS

- Tangible Cultural Heritage (TCH): This indicator evaluates architectural and archaeological assets within the examined sites and their immediate surroundings. The assessment criteria include the presence of archaeological sites (AS) and urban sites (US), the integrity of heritage elements, and the number of monumental structures. Data from the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism database [46] and observations from fieldwork were used to inform this evaluation;

- Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH): This indicator encompasses belief and celebration rituals, traditional games, music, literature, cuisine, artisanal crafts, production methods, and trade culture. The identification of ICH relied not only on printed sources but also heavily on interviews conducted with local residents. The applicability and current influence of heritage elements were key criteria for determining appropriate parameters. Additionally, ICH provides valuable insights into the social dynamics and cultural activities present at each site;

- Natural Heritage (NH): This indicator evaluates Natural Sites (NS), Wildlife Development Areas (WDA), Nature Parks (NP), Registered Caves (RC), potential conservation areas, and sustainable habitats. The identification of NS, WDA, NP, and RC, which are designated according to national legislation, was based on data from the Ministry of Environment, Urbanization, and Climate Change and the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry [47,58]. Potential conservation areas and sustainable habitats were assessed through consultations with experts. Urban areas lacking nature conservation zones and habitats degraded by activities such as mining or quarrying were assigned a rating of “0”;

- Accessibility to Basic Services (ABS): Three key services were identified as significantly contributing to the assessment of the examined sites: sale of basic goods (SBG), indicating the availability of essential items such as food, healthcare products, and hygiene goods; settings for social interaction (SSI), referring to spaces that facilitate social engagement, such as museums, exhibition halls, traditional coffee houses, and village meeting rooms; and accessibility to public transport (APT), defined by the presence of public transportation access points within 3 km of the site. For each of these services—SBG, SSI, and APT—1 point was added to the overall rating.

- Connectivity with Attraction Centers (CAC): CAC measures the connectivity of sites to existing tourist destinations and major population centers. The identified attraction centers within the study area include Safranbolu, Amasra, Yörük, Hadrianoupolis, Karabük, and Bartın. To determine the appropriate parameter for each site, the average distance to the three nearest attraction centers was calculated. Ratings were assigned based on 15 km intervals, as shown in Table 1.

2.2.2. Multi-Criteria Decision-Making with AHP

- The AHP-based route assessment consists of two main stages: (1) identification of indicators and parameters, and (2) weighting of indicators according to tourist preferences.

- The AHP indicators must be consistent with the indicators used in site analysis to ensure the connection between site characteristics and tourist preferences. Identification of indicators and parameters was based on a combination of literature review, context, and expert evaluations (Table 1).

- A type of survey was presented to tourists, created using the Saaty scale (1–9) [59], based on the comparisons of the 5 indicators (TCH, ICH, NH, ABS, CAC) with each other. As a result of comparing the indicators in pairs, a decision matrix was created according to tourist preferences in the region, and indicator weights were determined (Section 4.2).

2.2.3. Clustering

2.2.4. SWOT Analysis

2.3. Charrettes

3. Research Area

3.1. Historical Background

3.2. Heritage, Conservation and Tourism

3.2.1. Urban Areas

3.2.2. Rural Areas

3.2.3. Regional Tourism Experiences

3.2.4. Participatory Planning Experience

4. Results

4.1. GIS Application

4.1.1. Spatial Mapping

4.1.2. Rating of Sites

4.2. AHP Application

4.3. Clustering Results

4.4. Proposal for the Eco-Cultural Route

- Group A: Routes accessible by public transportation, offering the highest level of comfort.

- Group B: Routes suitable for wheeled eco-vehicles, providing a moderate level of comfort, higher than Groups C and D.

- Group C: Routes consisting primarily of unpaved or deteriorated roads, generally unsuitable for eco-vehicles.

- Group D: Routes where the use of vehicles is not recommended, designed specifically for trekking. These paths offer scenic vistas and natural landscapes, enhancing the traveler’s experience.

4.5. SWOT Analysis

4.5.1. Strengths

4.5.2. Weaknesses

4.5.3. Opportunities

4.5.4. Threats

4.6. Charrettes

- Integration of Cultural and Natural Heritage Sites: Establishing eco-cultural routes that link cultural and natural heritage areas to promote comprehensive and diverse visitor experiences.

- Community Participation: Developing mechanisms that facilitate the active and effective involvement of local communities in regional and local planning processes while ensuring transparency as a core principle for institutional practice.

- Regulation of Transportation: Differentiating between motor vehicle roads, eco-friendly transport routes, and pedestrian pathways to mitigate traffic congestion and carbon emissions while promoting walkable environments.

- Accessibility: Implementing inclusive principles and infrastructure to create a barrier-free environment, ensuring accessibility for all individuals.

- Enhancement of Infrastructure: Expanding and improving critical infrastructure and public services to better accommodate the needs and expectations of both locals and tourists. Most notably, prioritizing nature-based solutions and resilience for the climate crisis, including the rehabilitation of green corridors and coastal ecotonal areas, is vital.

- Advancement of Conservation and Promotion Efforts: Developing innovative and robust methods for the protection and presentation of heritage sites to ensure their preservation while fostering collaboration with various stakeholders.

5. Discussion

5.1. Heritage Dimension

5.2. Tourism Dimension

5.3. Methodological Reflection

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

- The existing tourism dynamics support the potential success of the route. According to 2024 statistics, approximately 2,600,000 people (including daily visitors) visit Safranbolu annually [103], while Amasra receives around 2,500,000 visitors (including daily visitors) annually [104]. These figures can be associated with the potential demand for the final product. However, beyond the quantity of tourists, their expectations, socio-economic status, and diversity are crucial for the proper functioning of the route. At the international level, Amasra’s heavy reliance on cruise tourism—particularly with a large proportion of Russian tourists—and Safranbolu’s dependency on visitors mainly from China, Taiwan, and Thailand contribute to a limited tourist profile. This lack of diversity increases the vulnerability of the tourism sector in both destinations.

- Among the high-potential sites, the following are recommended as priorities during the initial implementation phase to support the development of surrounding areas: (1) Safranbolu, Amasra, and the nearby sites (Yazıköy, Bulak, Kirkille, and Gömü), (2) the sites located together in the Soğanlı Stream Valley, featuring archaeological heritage and traditional architecture (Hacılarobası, Ilbarıt, Karakoyunlu, Bürnük, Hocaoğlu K., Çavuşlar, Bağlıca, and Sallar), and (3) the two provincial centers, Karabük and Bartın.

- Many successful examples have recognized the “cultural route” as a method for preserving and maintaining cultural heritage. However, numerous initiatives have failed due to prioritizing high revenue generation in the short and medium term [105]. Therefore, in the initial stages of implementation, the eco-cultural route must be subsidized by international, national, and local non-profit organizations. Moreover, for long-term economic sustainability, it is essential to gradually increase the financial contributions of cooperatives (including producers and businesses), local community associations, and private sponsors to the central budget.

- Ensuring income diversification is crucial for sustainable development and socio-economic resilience. Tourism revenues alone may not be sufficient to achieve sustainability in sensitive areas that require protection. In this case, “multiple-use management” is recommended [106]. Therefore, developing multiple uses (such as agriculture, livestock, and crafts) that align with the identities of the sites is important. Such regional planning requires interdisciplinary efforts.

- To highlight cultural heritage, we recommend removing structures that damage tangible cultural heritage and disrupt the skyline. Sites that have not yet been protected at the building scale should be urgently safeguarded, and restoration and infrastructure work should be carried out. In this regard, sites such as Amasra Castle and the Yenişehir in Karabük (industrial heritage) should be prioritized. In line with the eco-cultural route context, particularly in rural areas, abandoned caravanserais, hammams, historical bazaars, and mansions should be restored and repurposed for tourism and other services.

- The expansion of the ecological conservation cases exemplified within the research area is crucial for the preservation of natural heritage, particularly through increased local awareness. Interventions that promote eco-social transition—such as erosion and flood prevention, protection of endemic species, and restoration of habitat diversity—should be adopted and implemented by regional and local authorities. Mining, quarry activities, and unplanned construction should be prevented within the area, and restoration projects for natural areas should be carried out.

- The proposed route prioritizes roads that require minimal intervention to reduce environmental impact and address geographic and economic challenges. Alternatives exist for less suitable roads. However, improving public transportation and adapting roads for eco-friendly vehicles is essential. In particular, access to İmanlar, Derecami, and Karapınar should be enhanced. To reduce conflicts among different user groups, roads should also be separated based on user types, and appropriate safety measures should be implemented.

- Especially in sensitive areas where natural and cultural heritage intersect, initiatives that integrate social structures with heritage must be consciously sustained over the long term to ensure success [107]. In the regional dynamics, the efforts that began in the 1970s in Safranbolu and the Yörük village only started to yield positive results toward the 2000s. Therefore, to minimize the potential negative impacts of interventions on the local population and heritage sites (such as degradation, gentrification, migration, unplanned construction, the complete abandonment of traditional production methods), planning must be extended over the long term and periodically reviewed.

- Seven main stages, which must be carried out in coordination, are proposed to ensure the successful implementation of the project: (1) establishing the central budget with contributions from non-profit organizations, (2) conducting awareness-raising activities and developing protection and restoration activities for heritage sites, as well as regulatory activities for tourism areas, (3) implementing measures to enhance road safety and accessibility while supporting ecological transportation methods, (4) supporting the return of the local population and increasing local production through social and economic incentives, (5) developing tourism, production, and infrastructure facilities with an approach that aligns with the characteristics of the sites and the theme of the route, (6) encouraging participation in networks that support ecotourism and conducting promotional activities, and (7) gradually increasing the contributions of cooperatives, local community associations, and sponsors to the central budget, ensuring economic sustainability.

- The study area consists of sub-regions with distinct characteristics. To develop a sustainable conservation and tourism approach, including eco-cultural routes, it is essential to adopt a holistic planning process that considers these unique attributes and encourages collaboration. These efforts, similarly to past experiences in the region, will drive responsible and robust policy implementation as well as future systemic impacts. In Safranbolu, steps can be taken to enhance the sustainability of tourism activities by prioritizing conservation and educational efforts while also integrating natural heritage areas into planning. In Amasra, which has advantages in tourism diversity and potential activities, ecological solutions should include supporting alternative tourism, reducing coastal tourism pressure, mitigating seasonality effects, and focusing on the sustainability of cultural and natural heritage. For rural areas, projects should promote local tourism products through sustainable certification programs and business networks, emphasizing circular and ecological approaches. Considering both regional and global crises, the proposed strategy is expected to be implemented with truly participatory, sustainable, fair, and circular economy practices.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

| ID | District | Site | TCH Rating (Norm.) | ICH Rating (Norm.) | NH Rating (Norm.) | ABS Rating (Norm.) | CAC Rating (Norm.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Eflani | 3 (1.89) | 2 (1.60) | 0 (0.00) | 3 (2.17) | 1 (0.80) | |

| 2 | Konak | 2 (1.26) | 1 (0.80) | 1 (0.81) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.80) | |

| 3 | Bedil | 2 (1.26) | 2 (1.60) | 1 (0.81) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.80) | |

| 4 | Eflani | Çelebiler | 2 (1.26) | 2 (1.60) | 1 (0.81) | 3 (2.17) | 1 (0.80) |

| 5 | Esencik | 3 (1.89) | 2 (1.60) | 2 (1.63) | 1 (0.72) | 0 (0.00) | |

| 6 | Kocacık | 1 (0.63) | 1 (0.80) | 1 (0.81) | 1 (0.72) | 1 (0.80) | |

| 7 | Ulugeçit | 2 (1.26) | 2 (1.60) | 2 (1.63) | 1 (0.72) | 1 (0.80) | |

| 8 | Eskipazar | 1 (0.63) | 2 (1.60) | 0 (0.00) | 3 (2.17) | 1 (0.80) | |

| 9 | Arslanlar | 0 (0.00) | 2 (1.60) | 1 (0.81) | 3 (2.17) | 1 (0.80) | |

| 10 | Bayındır | 1 (0.63) | 2 (1.60) | 1 (0.81) | 3 (2.17) | 1 (0.80) | |

| 11 | Beytarla | 1 (0.63) | 2 (1.60) | 1 (0.81) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.80) | |

| 12 | Çekişler | 3 (1.89) | 2 (1.60) | 1 (0.81) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.80) | |

| 13 | Hadrianoupolis | 3 (1.89) | 1 (0.80) | 1 (0.81) | 2 (1.45) | 1 (0.80) | |

| 14 | Bulduk | 1 (0.63) | 2 (1.60) | 1 (0.81) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | |

| 15 | Büyükyayalar | 1 (0.63) | 1 (0.80) | 1 (0.81) | 2 (1.45) | 1 (0.80) | |

| 16 | Çaylı | 1 (0.63) | 1 (0.80) | 1 (0.81) | 2 (1.45) | 1 (0.80) | |

| 17 | Deresemail | 1 (0.63) | 1 (0.80) | 1 (0.81) | 1 (0.72) | 1 (0.80) | |

| 18 | Soplan | 1 (0.63) | 1 (0.80) | 1 (0.81) | 3 (2.17) | 0 (0.00) | |

| 19 | Kadılar | 1 (0.63) | 2 (1.60) | 1 (0.81) | 3 (2.17) | 1 (0.80) | |

| 20 | Eskipazar | Hamamlı | 3 (1.89) | 2 (1.60) | 1 (0.81) | 3 (2.17) | 1 (0.80) |

| 21 | Hanköy | 2 (1.26) | 2 (1.60) | 1 (0.81) | 2 (1.45) | 2 (1.60) | |

| 22 | İmanlar | 2 (1.26) | 2 (1.60) | 3 (2.44) | 2 (1.45) | 1 (0.80) | |

| 23 | Karahasanlar | 3 (1.89) | 1 (0.80) | 1 (0.81) | 1 (0.72) | 2 (1.60) | |

| 24 | Aşağısaray | 3 (1.89) | 2 (1.60) | 1 (0.81) | 1 (0.72) | 2 (1.60) | |

| 25 | Kıranköy | 3 (1.89) | 2 (1.60) | 1 (0.81) | 3 (2.17) | 2 (1.60) | |

| 26 | Tepeköy | 1 (0.63) | 1 (0.80) | 1 (0.81) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.80) | |

| 27 | Yeniköy | 1 (0.63) | 1 (0.80) | 1 (0.81) | 2 (1.45) | 1 (0.80) | |

| 28 | Ozan | 2 (1.26) | 2 (1.60) | 1 (0.81) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.80) | |

| 29 | Yürük (Üçevler) | 2 (1.26) | 1 (0.80) | 1 (0.81) | 3 (2.17) | 2 (1.60) | |

| 30 | Yazıkavak | 2 (1.26) | 2 (1.60) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.80) | |

| 31 | Kıncılar | 2 (1.26) | 1 (0.80) | 1 (0.81) | 3 (2.17) | 1 (0.80) | |

| 32 | Yorgalar | 2 (1.26) | 1 (0.80) | 1 (0.81) | 3 (2.17) | 1 (0.80) | |

| 33 | Karabük | 3 (1.89) | 3 (2.40) | 3 (2.44) | 3 (2.17) | 3 (2.40) | |

| 34 | Macar Çiftliği | 1 (0.63) | 1 (0.80) | 1 (0.81) | 2 (1.45) | 2 (1.60) | |

| 35 | Bulak | 3 (1.89) | 3 (2.40) | 2 (1.63) | 3 (2.17) | 3 (2.40) | |

| 36 | Mencinis Cave | 1 (0.63) | 0 (0.00) | 3 (2.44) | 2 (1.45) | 3 (2.40) | |

| 37 | Bürnük | 3 (1.89) | 1 (0.80) | 2 (1.63) | 1 (0.72) | 2 (1.60) | |

| 38 | Dayıslar | 1 (0.63) | 1 (0.80) | 1 (0.81) | 2 (1.45) | 2 (1.60) | |

| 39 | Karabük | Cildikısık | 3 (1.89) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (1.63) | 3 (2.17) | 2 (1.60) |

| 40 | Davutlar | 3 (1.89) | 1 (0.80) | 1 (0.81) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.80) | |

| 41 | Aktaş | 2 (1.26) | 1 (0.80) | 1 (0.81) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.80) | |

| 42 | Kayı | 1 (0.63) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.81) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (1.60) | |

| 43 | Ödemiş | 3 (1.89) | 1 (0.80) | 1 (0.81) | 3 (2.17) | 3 (2.40) | |

| 44 | Üçbaş | 3 (1.89) | 1 (0.80) | 1 (0.81) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (1.60) | |

| 45 | Zopran | 3 (1.89) | 1 (0.80) | 1 (0.81) | 2 (1.45) | 2 (1.60) | |

| 46 | Ovacık | Hocaoğlu Köp. | 1 (0.63) | 1 (0.80) | 2 (1.63) | 1 (0.72) | 2 (1.60) |

| 47 | Karakoyunlu | 3 (1.89) | 1 (0.80) | 2 (1.63) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (1.60) | |

| 48 | Safranbolu | 3 (1.89) | 3 (2.40) | 3 (2.44) | 3 (2.17) | 3 (2.40) | |

| 49 | Sabuncular | 1 (0.63) | 1 (0.80) | 1 (0.81) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (1.60) | |

| 50 | Bağcığaz | 1 (0.63) | 1 (0.80) | 1 (0.81) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.80) | |

| 51 | Çavuşlar | 3 (1.89) | 2 (1.60) | 2 (1.63) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (1.60) | |

| 52 | Çerçen | 2 (1.26) | 2 (1.60) | 1 (0.81) | 1 (0.72) | 3 (2.40) | |

| 53 | Delifazlıoğlu | 2 (1.26) | 1 (0.80) | 3 (2.44) | 2 (1.45) | 1 (0.80) | |

| 54 | Hacılarobası | 3 (1.89) | 2 (1.60) | 2 (1.63) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (1.60) | |

| 55 | Sallar | 3 (1.89) | 1 (0.80) | 2 (1.63) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (1.60) | |

| 56 | İnceçay | 2 (1.26) | 1 (0.80) | 1 (0.81) | 3 (2.17) | 2 (1.60) | |

| 57 | Karapınar | 3 (1.89) | 3 (2.40) | 3 (2.44) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (1.60) | |

| 58 | Kirkille | 3 (1.89) | 2 (1.60) | 3 (2.44) | 3 (2.17) | 3 (2.40) | |

| 59 | Çevrikköprü | 1 (0.63) | 3 (2.40) | 1 (0.81) | 3 (2.17) | 3 (2.40) | |

| 60 | Safranbolu | Kuzyakahacılar | 2 (1.26) | 1 (0.80) | 1 (0.81) | 0 (0.00) | 3 (2.40) |

| 61 | Kuzyakaöte | 3 (1.89) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.81) | 0 (0.00) | 3 (2.40) | |

| 62 | Dursanlı | 1 (0.63) | 1 (0.80) | 3 (2.44) | 3 (2.17) | 1 (0.80) | |

| 63 | Ovacuma | 1 (0.63) | 2 (1.60) | 1 (0.81) | 3 (2.17) | 1 (0.80) | |

| 64 | Osmansökü | 1 (0.63) | 2 (1.60) | 1 (0.81) | 1 (0.72) | 2 (1.60) | |

| 65 | Sat | 2 (1.26) | 1 (0.80) | 1 (0.81) | 3 (2.17) | 3 (2.40) | |

| 66 | Tayyip | 2 (1.26) | 1 (0.80) | 3 (2.44) | 1 (0.72) | 1 (0.80) | |

| 67 | Ilbarıt (Üçbölük) | 3 (1.89) | 2 (1.60) | 2 (1.63) | 1 (0.72) | 2 (1.60) | |

| 68 | Bağlıca | 1 (0.63) | 1 (0.80) | 2 (1.63) | 1 (0.72) | 2 (1.60) | |

| 69 | Yazıköy | 3 (1.89) | 3 (2.40) | 2 (1.63) | 3 (2.17) | 3 (2.40) | |

| 70 | Yörük | 3 (1.89) | 3 (2.40) | 3 (2.44) | 3 (2.17) | 3 (2.40) | |

| 71 | Susunduk | 3 (1.89) | 2 (1.60) | 1 (0.81) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (1.60) | |

| 72 | Bartın | Bartın | 3 (1.89) | 3 (2.40) | 3 (2.44) | 3 (2.17) | 1 (0.80) |

| 73 | Muratbey | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.80) | 1 (0.81) | 3 (2.17) | 1 (0.80) | |

| 74 | Amasra | Amasra | 3 (1.89) | 3 (2.40) | 3 (2.44) | 3 (2.17) | 1 (0.80) |

| 75 | Gömü | 2 (1.26) | 2 (1.60) | 3 (2.44) | 3 (2.17) | 1 (0.80) | |

| 76 | Sarnıç | 1 (0.63) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.81) | 3 (2.17) | 1 (0.80) | |

| 77 | Üçpınar | 1 (0.63) | 1 (0.80) | 1 (0.81) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | |

| 78 | Akviren | 1 (0.63) | 1 (0.80) | 1 (0.81) | 1 (0.72) | 0 (0.00) | |

| 79 | Bayraktar | 1 (0.63) | 1 (0.80) | 1 (0.81) | 3 (2.17) | 0 (0.00) | |

| 80 | Ulus | Ürkütler | 1 (0.63) | 1 (0.80) | 1 (0.81) | 3 (2.17) | 1 (0.80) |

| 81 | Kumluca | 0 (0.00) | 2 (1.60) | 1 (0.81) | 3 (2.17) | 1 (0.80) | |

| 82 | Derecami | 1 (0.63) | 2 (1.60) | 2 (1.63) | 1 (0.72) | 0 (0.00) | |

| 83 | Cumadüzü | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.81) | 1 (0.72) | 0 (0.00) | |

| 84 | Merkepören | 1 (0.63) | 0 (0.00) | 3 (2.44) | 1 (0.72) | 0 (0.00) | |

| TOTAL | 159 (100.00) | 125 (100.00) | 123 (100.00) | 138 (100.00) | 125 (100.00) |

References

- What Is Ecotourism? Available online: https://ecotourism.org/what-is-ecotourism/ (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Kocovic, M.; Djukic, V.; Vićentijević, D. Making heritage more valuable and sustainable trough intersectoral networking. In Cultural Management Education in Risk Societies-Towards a Paradigm and Policy Shift?! ENCATC, Ed.; Demos: Valencia, Spain, 2016; pp. 117–134. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Chen, X.; Liu, T. Linear Cultural Heritage Eco-Cultural Spatial System: A Case Study of the Great Tea Route in Shanxi. Front. Archit. Res. 2025, in press. [CrossRef]

- Lukoseviciute, G.; Henriques, C.N.; Pereira, L.N.; Panagopoulos, T. Participatory Development and Management of Eco-Cultural Trails in Sustainable Tourism Destinations. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2024, 47, 100779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Shen, Z.; Teng, X.; Mao, Q. Cultural Routes as Cultural Tourism Products for Heritage Conservation and Regional Development: A Systematic Review. Heritage 2024, 7, 2399–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trakala, G.; Tsiroukis, A.; Martinis, A. Eco-Cultural Development of a Restored Lake Environment: The Case Study of Lake Karla (Thessaly, Greece). Land 2023, 12, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zheng, X. A Cultural Route Perspective on Rural Revitalization of Traditional Villages: A Case Study from Chishui, China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Heritage Committee. Routes as a Part of Our Cultural Heritage; UNESCO: Madrid, Spain, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. The ICOMOS Charter on Cultural Routes. In Proceedings of the 16th General Assembly of ICOMOS, Québec, QC, Canada,, 4 October 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Arizmendi, A.; Amaranggana, A.; Cano, B.; Holder, A.; Cholakova, E.; Zungi, M.; Gomez, J.; Ilin, D. (Eds.) Global Report on Caultural Routes and Itineraries; World Tourism Organization (UNWTO): Madrid, Spain, 2015; Volume 12, pp. 39–66. [Google Scholar]

- “Cultural Routes of the Council of Europe” Certification. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/cultural-routes/certification1 (accessed on 9 October 2024).

- Rudan, E.; Madžar, D.; Zubović, V. New Challenges to Managing Cultural Routes: The Visitor Perspective. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandrgoc, S.; Dunaway, D. The History of Route 66. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago de Compostela Pilgrim Routes. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/cultural-routes/the-santiago-de-compostela-pilgrim-routes (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- The Stevenson Trail. Available online: https://www.cevennes-tourisme.fr/en/i-discover/walks-and-hikes-in-the-cevennes/the-gr/stevensons-path/ (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- Dodds, R.; Butler, R. The Phenomena of Overtourism: A Review. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2019, 5, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanini, S. Tourism Pressures and Depopulation in Cannaregio: Effects of Mass Tourism on Venetian Cultural Heritage. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 7, 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imon, S.S. Cultural Heritage Management under Tourism Pressure. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2017, 9, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantinato, E. The Impact of (Mass) Tourism on Coastal Dune Pollination Networks. Biol. Conserv. 2019, 236, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate Change. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/topic/climate-change (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- Apostolopoulos, N.; Makris, I.; Apostolopoulos, S.; Dimitrakopoulos, P. Resilience of Rural Micro-Businesses in an Adverse Entrepreneurial Environment: Adapting to the Energy Crisis. J. Enterprising Communities 2024, 18, 1023–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban Population (% of Total Population)—World. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.URB.TOTL.IN.ZS?contextual=default (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- Population (% of Total Population)—Turkiye. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.URB.TOTL.IN.ZS?contextual=default&locations=TR (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- Güler, K.; Kâhya, Y. Developing an Approach for Conservation of Abandoned Rural Settlements in Turkey. A/Z ITU J. Fac. Archit. 2019, 16, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekici, S.C.; Özçakır, Ö.; Bilgin Altinöz, A.G. Sustainability of Historic Rural Settlements Based on Participatory Conservation Approach: Kemer Village in Turkey. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 14, 497–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global and Regional Tourism Performance. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/tourism-data/global-and-regional-tourism-performance (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Acar, A.; Oğuz, U.K. Stakeholders Opinion Regarding Sustainable Heritage Tourism: The Case of Safranbolu. In Tourism in Contemporary Cities; International Tourism Studies Association (ITSA): Greenwich, UK, 2016; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Turkish National Commission for UNESCO. Türkiye’nin Dünya Miras Alanları Koruma ve Yönetimde Güncel Durum; UNESCO: Ankara, Türkiye, 2009; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Turkish National Commission for UNESCO. UNESCO World Heritage in Türkiye; UNESCO: Ankara, Türkiye, 2023; p. 249. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, Ş.S. Before and After World Heritage Decision in 1994, Safranbolu Settlement, Urban and Architectural Transformation. Master’s Thesis, Yıldız Teknik University, Istanbul, Turkey, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Şahin Körmeçli, P. Understanding the Historic Center by Using Network Analysis with Mental Mapping Method: The Case Study of Amasra, Turkey. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarı Nayim, Y. Evaluations on the Development of Sustainable Tourism in Amasra’s Urban Landscape. Bartin Orman Fak. Derg. 2014, 16, 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım, B. Conservation Problems of the Ancient Harbour Town of Amasra and Suggestions for Its Revitalization. Master’s Thesis, Karabük University, Karabük, Turkey, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Aslan, S.; Kiper, P. Urban Identity and Memory Problems: The Evaluation of Opportunities and Threats in Case Study of Amasra. İdealkent 2016, 7, 881–905. [Google Scholar]

- Özköse, A. Safranbolu Köylerinin Yöresel Mimarisi, 1st ed.; YEM Yayın: Istanbul, Türkiye, 2022; pp. 202–205. [Google Scholar]

- Batı Karadeniz Kalkınma Ajansı (BAKKA). Batı Karadeniz Turizm Master Planı Zonguldak, Karabük, Bartın. 2020, pp. 30–34+69. Available online: https://bakkakutuphane.org/upload/dokumandosya/tr81-turizm-master-plani-db.pdf?v=671bb4d809ed0 (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- Ruiz-Jaramillo, J.; García-Pulido, L.J.; Montiel-Vega, L.; Muñoz-Gonzalez, C.M.; Joyanes-Diaz, M.D. The Potential of Defensive Architectural Heritage as a Resource for Proposing Cultural Itineraries. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 13, 288–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Q.; Hong, X.; Ke, W.; Zhang, L.; Sun, G.; Gong, Y. Kohonen Self-Organizing Map Based Route Planning: A Revisit. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Prague, Czech Republic, 27 September 2021; pp. 7969–7976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, D. Silk Roads or Steppe Roads? The Silk Roads in World History. J. World Hist. 2000, 11, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çınar, H.; Bulut, M.; Yiğit, İ. Tarihi İpek Yolu’nun Kuzey Anadolu Güzergâhı. In Medeniyetler Güzergahı İpek Yolu’nun Yeniden Doğuşu; Bulut, M., Ed.; İstanbul Sebahattin Zaim Üniversitesi Yayınları: İstanbul, Türkiye, 2018; p. 129. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth, W.F. Travels and Researches in Asia Minor; John, W. Parker, West Stand: London, UK, 1842; pp. 53–73. [Google Scholar]

- Mordtmann, A.D. Anatolien, Skizzen Und Reisebriefe Aus Kleinasien: 1850–1859; Babinger, F., Ed.; Orienbuchhandlung Heinz Lafaire: Hannover, Germany, 1925; pp. 223–284. [Google Scholar]

- Diest, W.V.; Anton, M. Neue Forschungen Im Nordwestlichen Kleinasien; Justus Perthes: Gotha, Germany, 1895; pp. 63–77. [Google Scholar]

- Leonhard, R. Paphlagonia Reisen Und Forschungen Im Nördlichen Kleinasie; Dietrich Reimer (Ernst Vohsen): Berlin, Germany, 1915; pp. 137–149. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, H.C. Washed by Four Seas; T. Fisher Unwin: London, UK, 1908; pp. 253–283. [Google Scholar]

- Sit Alanları. Available online: https://korumakurullari.ktb.gov.tr/TR-245828/sit-alanlari.html (accessed on 4 November 2024).

- Sit Alanları Yönetim Sistemi. Available online: https://says.csb.gov.tr/citizen (accessed on 9 October 2024).

- Byrd, E.T. Stakeholders in Sustainable Tourism Development and Their Roles: Applying Stakeholder Theory to Sustainable Tourism Development. Tour. Rev. 2007, 62, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Torre, M.; MacLean, M.G.H.; Mason, R.; Myers, D. Heritage Values in Site Management; Getty Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Heyik, M.A.; Özer, D.G.; Romero-Martínez, J.M.; Abarca-Alvarez, F.J. Reclaiming Site Analysis from Co-Sensing to Co-Ideation: A Collective Cartography Strategy and Tactical Trajectories. Int. J. Archit. Comput. 2024, 22, 238–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siguencia, L.O.; Gomez-Ullate, M.; Kamara, A. Cultural Management and Tourism in European Cultural Routes: From Theory to Practice; Publishing House of the Research and Innovation in Education Institute: Czestochowa, Poland, 2016; pp. 101–102. [Google Scholar]

- Della Spina, L.; Giorno, C. Cultural Landscapes: A Multi-stakeholder Methodological Approach to Support Widespread and Shared Tourism Development Strategies. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppich, R.; Ostergren, G.; Werden, L. Geographic Information Systems and the State of Databases as They Relate to Historic Resources. In Proceedings of the ICOMOS 16th General Assembly and International Scientific Symposium, Quebec, QC, Canada, 29 September–4 October 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.H. Urban Planning and Design Strategy Based on ArcGIS and Application Method. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Energy Resources and Sustainable Development (ICERSD 2020), Harbin, China, 25 December 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Fulcrum Field Data Collection Platform. Available online: https://www.fulcrumapp.com/platform/ (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Chen, H.; Chen, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, D. Research on Greenway Route Selection of Traditional Villages Based on GIS: A Case Study of Xingtai County, China. J. Geogr. Inf. Syst. 2022, 14, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Bauer, T. Evaluating Natural Attractions for Toursm. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 422–438. [Google Scholar]

- Doğa Turizmi Web Uygulaması. Available online: https://ekotaban.tarimorman.gov.tr/ (accessed on 9 October 2024).

- Saaty, T.L. Decision Making with the Analytic Hierarchy Process. Int. J. Serv. Sci. 2008, 1, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diti, I.; Torreggiani, D.; Tassinari, P. Rural Landscape and Cultural Routes: A Multicriteria Spatial Classification Method Tested on an Italian Case Study. J. Agric. Eng. 2015, 46, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Duarte-Duarte, J.B.; Talero-Sarmiento, L.H.; Rodríguez-Padilla, D.C. Methodological Proposal for the Identification of Tourist Routes in a Particular Region through Clustering Techniques. Heliyon 2021, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Man, S.; Zhu, X.; Zhao, H.; Yan, T. Sustainable Protection Strategies for Traditional Villages Based on a Socio-Ecological Systems Spatial Pattern Evaluation: A Case Study from Jinjiang River Basin in China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, H.; Kohonen, T. Self-Organizing Semantic Maps. Biol. Cybern. 1989, 61, 241–254. [Google Scholar]

- Dammag, B.Q.D.; Jian, D.; Dammag, A.Q. Cultural Heritage Sites Risk Assessment and Management Using a Hybridized Technique Based on GIS and SWOT-AHP in the Ancient City of Ibb, Cultural Heritage Sites Risk Assessment and Management Using a Hybridized. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2024, 88, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lami, I.M.; Mecca, B. Assessing Social Sustainability for Achieving Sustainable Architecture. Sustainability 2021, 13, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Mao, Z.; Zhang, W. Design Charrette as Methodology for Post-Disaster Participatory Reconstruction: Observations from a Case Study in Fukushima, Japan. Sustainability 2015, 7, 6593–6609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılavuz, B.N.; Çelikbaş, E. Paphlagonia Hadrianoupolis’i. Tar. Kültür Ve Sanat Araştırmaları Derg. 2013, 2, 159–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crow, J.; Hill, S. The Byzantine Fortifications of Amastris in Paphlagonia. Anatol. Stud. 1995, 45, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelebi, E. Günümüz Tiirkçesiyle Evliya Çelebi Seyahatnamesi: Bursa-Bolu-Trabzon-Erzurum-Azerbaycan-Kafkasya-Kırım-Girit 2. Cilt 1. Kitap, 2nd ed.; Dağlı, Y., Kahraman, S.A., Eds.; Yapı Kredi Yayınları: İstanbul, Türkiye, 2008; pp. 85–86. [Google Scholar]

- Günay, R. Türk Ev Geleneği ve Safranbolu Evleri; YEM Yayin: İstanbul, Türkiye, 1998; pp. 95–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kalyoncu, H.; Tunçözgür, Ü. Mübadele ve Safranbolu; Karabük Valiliği Yayınları: Ankara, Türkiye, 2012; pp. 51–53. [Google Scholar]

- Trading Posts and Fortifications on Genoese Trade Routes from the Mediterranean to the Black Sea. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/6468 (accessed on 21 October 2024).

- Orman Varlığımız Artarak %73 Oldu. Available online: http://www.karabuk.gov.tr/orman-varligimiz-artarak-73-oldu (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Türkiş, S. Vegetation Characteristics of Eğriova and Kavaklı Forests: Yenice Hotspots. In Practicability of the EU Natura2000 Concept in the Forested Areas of Turkey; Güngöroğlu, C., Ed.; Turkey Foresters’ Association: Ankara, Türkiye, 2018; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Best Tourism Villages Upgrade Programme. Available online: https://tourism-villages.unwto.org/en/upgrade/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Maden, M. (Karabük, Türkiye). Personal photo archive. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2024–2028 Batı Karadeniz Bölge Planı. Available online: https://www.bakka.gov.tr/haber/bakka-2024-2028-bolge-plani-taslagi-icin-paydas-goruslerini-aliyor/1415 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- EarthExplorer. Available online: https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/ (accessed on 13 September 2023).

- İndirilebilir Veriler & Dosyalar. Available online: https://www.harita.gov.tr/urunler/indirilebilir-veriler-dosyalar/13 (accessed on 13 September 2023).

- OpenStreetMap Data for This Region: Turkey. Available online: https://download.geofabrik.de/europe/turkey.html (accessed on 13 September 2023).

- Habermas, J. On Social Identity. TELOS 1974, 1974, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sennett, R. Artesanía, Tecnología y Nuevas Formas de Trabajo: Hemos Perdido El Arte de Hacer Ciudades (Entrevista de Magda Anglès); Katz Editores: Barcelona, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Blandford, C. Management Plans for UK World Heritage Sites: Evolution, Lessons and Good Practice. Landsc. Res. 2006, 31, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, E. A Proposal for an Administrative Structure for Cultural Heritage Management in Turkey. Ph.D. Thesis, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sokka, S.; Badia, F.; Kangas, A.; Donato, F. Governance of Cultural Heritage: Towards Participatory Approaches. Eur. J. Cult. Manag. Policy 2021, 11, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, D.; Crabtree, J.R.; Wiesinger, G.; Dax, T.; Stamou, N.; Fleury, P.; Gutierrez Lazpita, J.; Gibon, A. Agricultural Abandonment in Mountain Areas of Europe: Environmental Consequences and Policy Response. J. Environ. Manag. 2000, 59, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Song, W.; Zhai, L. Land Abandonment under Rural Restructuring in China Explained from a Cost-Benefit Perspective. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serres, M. The Natural Contract, Studies in Literature and Science, 10th ed.; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Giménez, T.V. De La Justicia Climática a La Justicia Ecológica: Los Derechos de La Naturaleza. Rev. Catalana Dret Ambient. 2020, 11, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, D.H.; Meadows, D.L.; Randers, J.; Behrens, W. Los Límites Del Crecimiento; MIT-Club de Roma: Winterthur, Switzerland, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. Writing on Cities; Kofman, E., Lebas, E., Eds.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Avar, A.A.; Cive, Y.Ö. Rethinking Planning and Nature Conservation through Degrowth/ Post-Growth Debates. Futures 2024, 161, 103416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Martínez, J.M.; Romero-Padilla, Y. ¿Por Qué Desurbanizar, Desconstruir y Renaturalizar?: Justificaciones Para Iniciar La Transición Ecosocial En Los Litorales Turísticos. Ciudad. Y Territ. Estud. Territ. 2024, 56, 1133–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faganel, A.; Trnavčevič, A. Sustainable Natural and Cultural Heritage Tourism in Protected Areas: Case Study. Ann. Za Istrske Mediter. Stud.-Ser. Hist. Sociol. 2012, 22, 589–600. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.W.; Syah, A.M. Economic and Environmental Impacts of Mass Tourism on Regional Tourism Destinations in Indınesia. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2018, 5, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Hernández, M.; de la Calle-Vaquero, M.; Yubero, C. Cultural Heritage and Urban Tourism: Historic City Centres under Pressure. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D.B. Organic, Incremental and Induced Paths to Sustainable Mass Tourism Convergence. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1030–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, H.; Picazo, P.; Moreno Gil, S. The Pathway to Sustainability in a Mass Tourism Destination: The Case of Lanzarote. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, P. A Clear Path towards Sustainable Mass Tourism? Rejoinder to the Paper ‘Organic, Incremental and Induced Paths to Sustainable Mass Tourism Convergence’ by David, B. Weaver. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1038–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, J.M.; Suárez-Vega, R.; Santana-Jiménez, Y. The Inter-Relationship between Rural and Mass Tourism: The Case of Catalonia, Spain. Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Cultural Tourism: A Review of Recent Research and Trends. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 36, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinhans, R.J.; Falco, E. Digital Participation in Urban Planning: A Promising Tool or Technocratic Obstacle to Citizen Engagement? In Teaching, Learning & Researching Spatial Planning; TU Delft OPEN Publishing: Delft, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 70–81. [Google Scholar]

- Karabük Provincial Directorate of Culture and Tourism. (Karabük, Türkiye). Internal presentation. 2025.

- Bartın Provincial Directorate of Culture and Tourism. (Bartın, Türkiye). Internal presentation. 2025.

- Gaweł, Ł. Szlaki Dziedzictwa Kulturowego; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego: Krakow, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, B.; Grimwade, G. Balancing Use and Preservation in Cultural Heritage Management. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2007, 3, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Summer Academy. Developing Sustainable Rural Tourism; Prisma: Athens, Greece, 2003. [Google Scholar]

| Indicators | Parameters | Rating |

|---|---|---|

| Tangible Cultural Heritage (TCH) | Values forming a fabric or presence of a protected site or multiple monuments | 3 |

| Values forming a group or presence of a monument | 2 | |

| Preservation of some examples of values | 1 | |

| Authenticity is vastly degraded, or value is not detected | 0 | |

| Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) | The value creates regional attractiveness | 3 |

| The value creates local attractiveness | 2 | |

| The value only exists in memory | 1 | |

| Not enabling to identify value (due to abandonment, etc.) | 0 | |

| Natural Heritage (NH) | Presence of protected site/area/registered cave | 3 |

| Presence of a potential protected site/area/registered cave | 2 | |

| The presence of sustained natural habitat | 1 | |

| Irreversible degradation of natural values | 0 | |

| Accessibility to Basic Services (ABS) | Three of the specified basic services can be provided | 3 |

| Two of the specified basic services can be provided | 2 | |

| One of the specified basic services can be provided | 1 | |

| Lack of specified basic services | 0 | |

| Connectivity with Attraction Centers (CAC) | Avg. of 0–15 km from the 3 nearest specified centers | 3 |

| Avg. of 15.1–30 km from the 3 nearest specified centers | 2 | |

| Avg. of 30.1–45 km from the 3 nearest specified centers | 1 | |

| An average of at least 45 km | 0 |

| Indicators | TCH | ICH | NH | ABS | CAC | Weighting | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tangible Cultural Heritage | 1.00 | 1.73 | 0.87 | 2.23 | 1.27 | 0.25 | 2 |

| Intangible Cultural Heritage | 0.58 | 1.00 | 0.43 | 1.08 | 0.72 | 0.14 | 5 |

| Natural Heritage | 1.15 | 2.35 | 1.00 | 1.82 | 1.76 | 0.29 | 1 |

| Accessibility to Basic Services | 0.45 | 0.93 | 0.55 | 1.00 | 0.85 | 0.14 | 4 |

| Connectivity with Attraction Centers | 0.79 | 1.38 | 0.57 | 1.17 | 1.00 | 0.18 | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Karataş, E.; Özköse, A.; Heyik, M.A. Sustainable Heritage Planning for Urban Mass Tourism and Rural Abandonment: An Integrated Approach to the Safranbolu–Amasra Eco-Cultural Route. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3157. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073157

Karataş E, Özköse A, Heyik MA. Sustainable Heritage Planning for Urban Mass Tourism and Rural Abandonment: An Integrated Approach to the Safranbolu–Amasra Eco-Cultural Route. Sustainability. 2025; 17(7):3157. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073157

Chicago/Turabian StyleKarataş, Emre, Aysun Özköse, and Muhammet Ali Heyik. 2025. "Sustainable Heritage Planning for Urban Mass Tourism and Rural Abandonment: An Integrated Approach to the Safranbolu–Amasra Eco-Cultural Route" Sustainability 17, no. 7: 3157. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073157

APA StyleKarataş, E., Özköse, A., & Heyik, M. A. (2025). Sustainable Heritage Planning for Urban Mass Tourism and Rural Abandonment: An Integrated Approach to the Safranbolu–Amasra Eco-Cultural Route. Sustainability, 17(7), 3157. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073157