Abstract

Environmental degradation remains an increasingly urgent challenge, leading to focused debates at the Rio+20 conference (2012) on how to operationalise sustainability. This conference’s central theme was the green economy and the role of institutions in driving the transition to a more sustainable model. Today, concepts such as the green economy, circular economy, bioeconomy, and circular bioeconomy (CBE) are integral to institutional efforts towards sustainable development. The CBE has significant potential as a driver of sustainability. This article examines the challenges, opportunities, and governance structures that the Andalusian (Southern Spain) public administration is implementing in the context of the CBE. The findings are based on qualitative methods, with a comprehensive literature review, semi-structured interviews, and workshops with different stakeholders from the quadruple helix model, conducted as part of the ROBIN project and other related projects. The results systematises the main weaknesses and strengths collected during the fieldwork in terms of the tools of governance. The conclusions highlight the need to develop this model and outline the actions needed to develop the CBE further.

1. Introduction

The introduction of the concept of sustainability into the political agenda in 1992 resolved the false dichotomy between development and the environment. It is now widely accepted that development must be sustainable. The challenge is to improve and innovate the way we produce and consume food, products, and materials within healthy ecosystems. Nevertheless, environmental degradation remains an increasingly urgent challenge, leading to focused debates at the Rio+20 conference (2012) on how to operationalise sustainability. The green economy (GE) and the role of institutions in driving the transition to a more sustainable model were central themes at this conference [1].

Today, concepts such as the GE, circular economy (CE), bioeconomy (BE), and circular bioeconomy (CBE) are integral to institutional efforts towards sustainable development. The role of public policies is key in this transition. Thus, the European Union is already committed to this approach [2]. However, this transition suffers a knowledge gap in governance [2,3]. More specifically, public policies and governance involve a multiscale approach. This may require significant re-examination of the current models, and thus, lead to a new paradigm of sustainable development governance [4,5]. However, which specific governance mechanisms can governments use to address this challenge?

This paper focuses on identifying the challenges, opportunities, and governance structures that the regional government of Andalusia (Southern Spain) is implementing in the context of the CBE. Andalusia was the first region in Spain to approve a circular bioeconomy strategy in 2018 [6]. The identification was based on semi-structured interviews and workshops with stakeholders in the context of several European projects, mainly ROBIN [7], but also REINWASTE and POWER4BIO [8,9].

The ROBIN project Deploying circular bioeconomies at regional level with a territorial approach! (Horizon Europe, 2022–2025) aims to empower Europe’s regions to adapt their governance models and structures by promoting governance and social innovation and considering different actors and territorial contexts. It is planned to study the state of the art and encourage MARCS (Multi-Actor Regional Constellations) to advance circular bioeconomy governance in European regions.

The European POWER4BIO project Empowering regional stakeholders for realising the full potential of European BIOeconomy (Horizon 2020. 2018–2021) aims to increase the capacity of regional and local policy makers and stakeholders to drive the transition towards the bioeconomy in Europe by providing them with the necessary tools, instruments and guidance to develop and implement sustainable regional bioeconomy strategies. It also included a comprehensive learning program to boost intra- and interregional mutual learning, ensuring knowledge exchange across sectors for the joint development of sustainable bioeconomy value chains.

The REINWASTE project Remanufacture the food supply chain by testing innovative solutions for zero inorganic waste (INTERREG MED. MED Transnational Cooperation Programme. M2-Module 2-TESTING. 2018–2021) aims to encourage, through case studies and successful pilot actions, the food supply chain (both in the primary and food processing sectors) to incorporate innovative technological products (Best Available Solutions) to reduce or eliminate inorganic waste.

This study focuses on three main research questions (RQs) to address gaps in CBE governance:

RQ1: As CBE involves transdisciplinary factors… What is the role of regional and territorial coordination?

RQ2: As CBE is an innovative approach… What is the role of knowledge, communication and co-creation processes?

RQ3: What is the governance model that best suits the promotion and development of the CBE?

The conceptual framework of this paper clarifies the relationship between sustainability, GE, CE, BE, and CBE, as well as presenting different types of governance. After the sections on methods and findings, the discussion focuses on the challenges of CBE governance and the role of public policies in fostering an economic model based on biological principles and processes to replace fossil-based raw materials with bio-based materials, principles, and processes towards a CBE model [4].

2. Background

2.1. Sustainability: Green Economy, Circular Economy, Bioeconomy and Circular Bioeconomy

At the end of the first decade of the 21st century, there was a context consisting of a series of economic and environmental crises [10]. In this context, the UN General Assembly called for Rio+20 to focus on two themes: a green economy to foster sustainable development and poverty eradication, and the institutional framework for sustainable development [11]. From 1992 to 2012, the concept of sustainability was included in political agendas, but in a motivational sense to align common efforts. However, the improvements did not address the critical challenges over the past twenty years. Sustainability was a broad umbrella concept and needed more specific mechanisms to be implemented and to address global challenges.

The green economy was a pragmatic choice for building consensus in Rio+20 and promoting rapid action during a crisis [4]. GE advocates that ecological processes occurring in natural and semi-natural systems can be leveraged to the benefit of human beings, promoting low-carbon energy and without compromising the sustainability of these ecosystems [10,12]. In addition, GE can be thought of as a low carbon, resource-efficient, and socially inclusive concept [13]. However, the limitations of GE include its strong focus on technological and market-based solutions for green growth, which are considered insufficient to address current sustainability issues and are sometimes identified as co-creators of the problems [14].

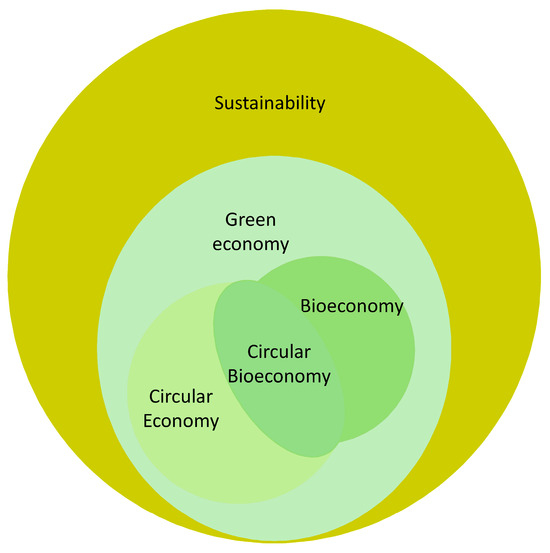

The green economy encompasses several related concepts (Figure 1) and there are clear synergies between them, in particular between the bioeconomy and the circular economy.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework placing CBE within a sustainability approach.

The circular economy (also known as zero waste economy) is an economic concept integrated in sustainable development to produce goods and services while reducing consumption and waste of raw materials, water, and energy sources. CE principles (reuse, repair, and recycle) contribute to improving and innovating in methods needed to reach sustainability [10,15]. CE includes rethinking product/service design to reduce the material and energy needed for production; long-term maintenance and repair; sharing; reuse; recycling; reclassification of waste into inorganic and biological components; and renewability of energy sources [14]). The European Commission defines the circular economy as an economy “where the value of products, materials, and resources is maintained in the economy for as long as possible, and the generation of waste minimised, [it] is an essential contribution to the EU’s efforts to develop a sustainable, low-carbon, resource-efficient, and competitive economy” [16].

CE strategies should explicitly propose strategic and systematic approaches in order to bring all stakeholders together to achieve policy coherence. Consequently, it is essential for all CE actors to establish closer connections with multi-perspective policy processes and intergovernmental discussions, and to be organised around a common vision of a sustainable CE system [2].

At the same time, the number of BE definitions has been growing with the increasing interest of many countries, organizations, and scholars [17]. These definitions can be classified into three approaches. The first places biotechnology at the centre of BE, supported by the private sector and organisations such as the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). The second approach, also known as biomass BE, is based on the transformation of organic material from biological resources into goods. Therefore, it encompasses more sectors than biotech, such as energy, agriculture, fisheries, forestry, and chemistry, and is currently dominant in the EU [1,12,18,19]. Rojas et al. (2024) [18] provide a complete conceptual and historical review focused on these concepts.

The third definition emerges from an ecological and economic perspective. It is based on the limits of the natural environment anchored in a given territory, and agroecological practices would be included in this approach [12]. Thus, the Global Bioeconomy Summit 2015 defined BE as “the knowledge-based production and utilization of biological resources, innovative biological processes, and principles to sustainably provide goods and services across all economic sectors [20]. The dominant BE discourse embraces “efficiency” as a sustainability paradigm, but elements of consistency and sufficiency are also increasingly entering the debate as the early hype cycle levels off [21].

In this context, BE provides solutions to current global challenges, highlighting that (1) it guarantees food safety, (2) reduces water stress, (3) sustainably manages natural resources to avoid their overuse, (4) decreases dependence on fossil fuels and boost renewable energy, (5) generates green jobs, and (6) maintains productivity, and competitiveness [15].

Policy and academic literature have recently suggested that BE can benefit from broader sustainability considerations. According to the Council Conclusions of 22 March 2024, the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), focusing on a farmer-centred common agricultural policy post-2027 towards a competitive, crisis-proof, sustainable, farmer-friendly, and knowledge-based future EU agriculture, highlights the role of the CBE in supporting the green transition of the agricultural sector, and recognises the importance of the CAP in this respect [22]. The EU updated BE Strategy [23] states that ‘circularity is a quintessential element of the European Commission’s vision for an EU Bioeconomy’. The CBE is a ‘circular economic model based on producing and using renewable biomass resources and their sustainable and efficient transformation into bioproducts, bioenergy and services for society’ [24].

Therefore, the CBE involves elements common to the above concepts, such as improving resource use and eco-efficiency, reducing the carbon footprint, reducing the demand for fossil carbon, and promoting waste recovery [18].

2.2. Governance and Bioeconomy

Governance is the process by which societies adapt their rules to new challenges [4]. Governance is ‘the exercise of economic, political and administrative authority to manage a country’s affairs at all levels’, which ‘comprises mechanisms, processes, and institutions through which citizens and groups articulate their interests, exercise their legal rights, meet their obligations and mediate their differences’ [4].

For the OECD, governance is “the use of political authority and exercise of control in a society in relation to the management of its resources for social and economic development” which “encompasses the role of public authorities in establishing the environment in which economic operators function and in determining the distribution of benefits as well as the nature of the relationship between the ruler and the ruled” [25].

In general terms, “governance” encompasses systems of control and regulation, involving state intervention and rules governing private actors’ interactions, such as markets, associations, and actor networks, like clusters. This includes three dimensions at the regional level of governance: (i) a substantial dimension, determining governance rules; (ii) a procedural dimension, describing how rules are developed; and (iii) a structural dimension, outlining rulemaking institutions, implementation, enforcement, and conflict resolution mechanisms [26,27].

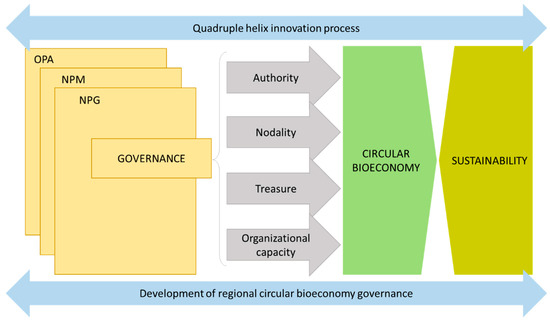

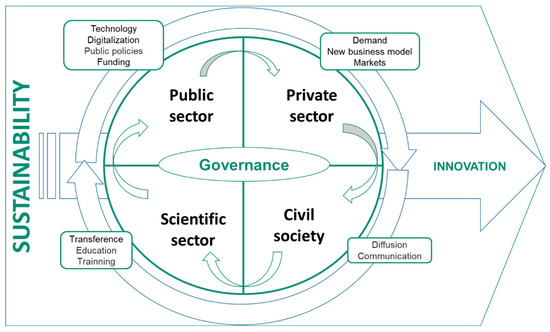

There are three main reform movements that have received the most attention in public administration scholarship: Orthodox Public Administration (OPA), New Public Management (NPM), and New Public Governance (NPG) [28,29,30,31] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Conceptual framework of governance for regional sustainable CBE. Source: Authors’ contribution.

The OPA paradigm had always conceived public policies as the systematic combinations of political decisions, taken by the majority of political representatives within public arenas, with their subsequent implementation by bureaucratic administrations using direct provisions, rules, and input-based tools [29]. OPA began to be criticised over time, particularly for its inefficiency. NPM is based on competition, an open market, and the outsourcing of public services through a wide range of incentive mechanisms. NPM ideas and practices boomed in the 1980s and 1990s, driven by the sharp rise in neoliberalist practices throughout western societies. At some points, NPM represented such an extreme shift toward neoliberalist deregulation that certain advocates even began to question whether public policy should be allowed to have any effect on public management. NPG arose from the assumption that NPM had failed to address urgent issues in contemporary society. NPG is predicated on a worldview that society is in a state of pluralism and should be governed with this reality in mind [30,31]. The diversification of NPM defines the most recent phase of public management reform. In this phase, starting from about the year 2000, policymakers increasingly tried to address the efficiency and effectiveness tension by integrating the NPM approach to change with politically and socially oriented reform. Post-NPM programs became more participative and collaborative [28].

Under the NPG paradigm, both scholars and policymakers have stressed that engaging with stakeholders and citizens in policymaking, by enabling citizens to play a legitimate proactive role as collaborators and creators rather than as passive users or consumers, can lead to more consistent, sustainable, and appropriate policies [29,32].

Collaborative governance arrangements comprised of multiple state and non-state actors have grown in their importance when addressing socio-environmental development challenges. Understanding which actors are involved, what resources they bring into the collaborative network, and how they engage with one another are central to understanding the potential for networks to effectively solve the problem at hand [33]. These collaborative networks can be considered as a co-evolution or an innovation process in a multi-stakeholder setting. The triple and quadruple helix innovation models [34,35] develop this multistakeholder approach.

Hood’s tools proposal argues that, for any policy problem, the government has four basic tools (Figure 2). Firstly, authority entails the legitimate legal or official power to command or prohibit. Secondly, nodality or communication is the property of being at the centre of social and information networks. In the twenty-first century, nodality—embedded in social and information networks—is bestowed on any internet user as a “peer-to-peer” network, providing ordinary citizens with unprecedented capacity to receive, share, and disseminate information across their own large scale. To lose nodality is for government to cede power, and even the very idea of what it means to be a state [36,37]. Thirdly, treasure is the possession of money or fungible chattels that may be exchanged. Finally, organizational capacity refers to the deployment of people, skills, land, buildings, and technology [36,38,39].

Work based on participatory approaches in the field of CBE, using the territorial approach and including all actors in the quadruple helix—public sector, private sector, academia, and scientists, as well as civil society—is necessary for the CBE model to succeed. This involves leveraging the challenges and opportunities while mitigating the weaknesses identified by stakeholders. Furthermore, there is a scarcity of work analyzing CBE according to governance and its tools within the theoretical framework presented in the Section 2. Therefore, we contribute to identifying the role of governance structures in the transition towards a CBE model in the region.

Additionally, the methodological approach of this study, based on stakeholders’ perceptions, provides a comprehensive view of the challenges and strategies from a practical and applied perspective.

3. Methods

3.1. Case Study

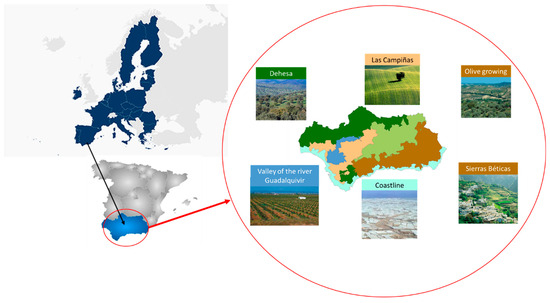

Andalusia’s surface area is 87,597 km2, representing 17% of the Spanish area, and 2% of the EU-27 area. It has around 8,500,000 inhabitants (17.9% of total inhabitants of Spain), of which 1,995,165 are in rural areas. Andalusia has a population density (97 people per km2) which is slightly higher than the Spanish average (94 people per km2) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Ecosystems in the region of Andalusia and its location in Spain and Europe.

Therefore, agricultural activities are the main source of employment in half of the Andalusian municipalities, with fruit and vegetable production predominant in the area. These agricultural products, mainly from horticulture, are typically produced following intensive practices in greenhouses. There are extensive vineyards, and citrus and berry farms. Thus, agriculture is a key economic, environmental, and social sector in the region. Data show that Andalusia is a global leader in the olive sector. The region boasts more than 1.5 million hectares of crop, which generates more than 24% of the value of Andalusia’s agricultural production and 80% of Spain’s olive oil production. Andalusia’s agricultural diversity is due to its varied orography, which includes areas of “Dehesa”, countryside, olive groves, the Bajo Guadalquivir, coastline, the Sierras Beticas, among others (Figure 3).

Andalusia’s abundance of biomass resources is attributable to the region’s agricultural activity and topography. The diversity of its farming and ecosystems (see Figure 3) has resulted in a substantial biomass resource base, predominantly originating from the agricultural and fisheries sectors. In total, Andalusia generates around 7.5 million tons of biomass per year from agriculture, of which more than 2.6 million tons come from olive groves. In addition, 5.5 million tons are generated from livestock farming and 6.8 million tons of biomass resources from agro-industry [24].

Andalusia also opted for this innovative approach and developed its own Andalusian Circular Bioeconomy Strategy, approved in 2018, becoming one of the first European regions to adopt a strategy in this field. This strategy focuses on the least developed sectors and activities of the bioeconomy, which therefore require greater institutional support through the implementation of specific measures and actions to facilitate their take-off and consolidation in the medium to long term. The main action areas of the bioeconomy strategy are within diverse sectors such as agriculture, utilization of available feedstock, sustainable production, innovation and research in the process and management of biomass producers, infrastructure and logistics management, cooperation between stakeholders, etc.

During this bioeconomy transition process in the Andalusian region, the private, public, academic, and applied sectors, as well as consumers and the public, play a key role in its development.

3.2. Data Collection

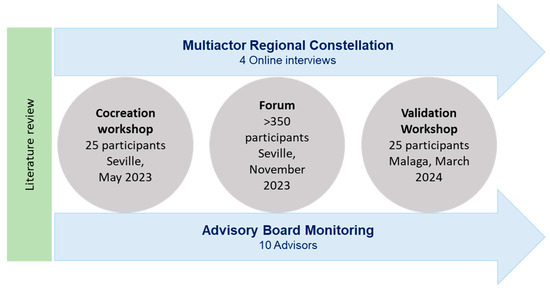

To analyse the CBE governance challenges and the role of public policies in fostering an economic model based on biological principles, after a literature review (paradigms and governance tools), data collection was implemented within the framework of the ROBIN project and other related projects and activities in Andalusia in four stages (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Methodological framework to identify and implement a sustainable Circular Bioeconomy governance model in Andalusia.

Firstly, four members from the ROBIN Multiactor Regional Constellation (MARC) members in Andalusia were interviewed online (March 2023). MARC is constituted in the context of the ROBIN project and comprises quadruple-helix stakeholders from local government, the business community, academic institutions, primary biomass producers, and civil society. ROBIN project MARC members are active in co-creating and informing the development of regional governance structures in the ROBIN regions. Two of the interviewers fall under the business community category, one works in an academic institution and an R&D and innovation agency, and another member works at a private cooperative.

The topics addressed during the interviews were (1) use of available feedstock and better management and exploitation of all biological resources; (2) promotion of business development based on biomass; (3) Research and Innovation Development regarding biomass; (4) new policy frameworks and the establishment of funding schemes; (5) strengthening of existing policy frameworks for the bioeconomy; (6) awareness raising/information sharing focused on the bioeconomy.

Secondly, a Co-creation Workshop (May 2023) was held with 25 participants engaging MARCs and other relevant regional stakeholders in the co-creation of specific governance models and practices that overcome barriers and seize opportunities for the CBE in Andalusia.

The workshop comprises the following sessions: Session 1: validation and prioritization of key barriers, potentialities, and opportunities to be pursued on bioeconomy in the region; Session 2: definition of improvement areas for current governance model(s) and co-creation of new one(s).

Thirdly, as an activity in the Circular Bioeconomy of the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, Water and Rural Development (CAPADR) of the Andalusian Regional Government, a Circular Bioeconomy Forum (November 2023) was organised by the General Secretariat for Agriculture, Livestock and Food of the CAPADR, in collaboration with the Joint Research Centre (JRC) of the European Commission in Seville and the Andalusian Institute for Research and Training in Agriculture, Fisheries, Food and Organic Production (IFAPA), with the participation of representatives of these institutions, as well as other administrations at European, national, regional, and Central American level. The event was attended by 26 speakers from different fields at European, national, regional, and Central American level, with the participation of more than 350 people, both in person and online. Additional information about this Forum and results can be found on the website of Foro de Economía Circular [40]. The Forum was structured around an introductory keynote speech on the status and prospects of the bioeconomy in the European Union, followed by four round tables: Policies and Strategies, Success Stories, Value Chain and Governance (this last one is the focus of this paper).

The panel focused on understanding the vision and experiences at the level of Spanish regions, from the perspective of Public Administration, regarding policies, plans, and strategies in the field of circular bioeconomy implemented at the regional level. To this end, the following aspects were discussed: main challenges and obstacles, ways to enhance the bioeconomy (platforms, nodes, etc.), cooperation and collaboration actions among stakeholders, communication, awareness, and sensitization actions, etc. Based on these sessions, conclusions and reflections were elaborated and mailed to the participants for feedback in order to develop the final report.

Fourthly, a Multitool Validation Workshop (March 2024) was performed involving 17 MARC and 8 regional experts. This workshop focused on identifying key elements to develop an awareness raising plan, strengthening the regional governance model and the implementation of potential new communication activities (Figure 4).

Finally, during the development of the ROBIN project, an Advisory Board, composed by 10 experts in bioeconomy, validated the information collected in the previous stages. The Advisory Board members bring their knowledge of the needs and problems currently faced by their stakeholders, and provide meaningful feedback on the ideas, pilot actions and results of the ROBIN project.

To systematise all these results, the information was analysed and structured according to a Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats (SWOT) strategy framework.

4. Results

This section presents the main opportunities, challenges, and governance structure for the CBE in Andalusia, according to the four tools highlighted by Hood [36,38], based on the quadruple helix stakeholders and experts involved.

4.1. Authority

In July 2016, the Regional Government of Andalusia decided to launch the Andalusian Circular Bioeconomy Strategy (ACBS) to contribute to the sustainable growth and competitiveness of the region. The ACBS was developed by the Regional Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, Water, and Rural Development and approved by the Andalusian Government in 2018. The bioeconomy in Andalusia is well advanced. The ACBS is being updated. In addition to the ACBS, in Andalusia there are legislation and sectoral strategies that contribute to its development, such as the Circular Economy Law (3/2023 of Marc 30, LECA) [40], the First Andalusian Strategy for the Olive Sector (pending approval), the First Strategic Plan for Fruits and Vegetables, etc., which include specific measures and actions that are closely aligned and in line with the ACBS.

The ACBS focuses on the development of activities among three segments of the bioeconomy value chain: biomass production, technical processing, and consumer markets. Table 1 summarises the main strengths in developing a circular bioeconomy strategy (Table 1).

Table 1.

Main strengths in developing a circular bioeconomy strategy.

According to the stakeholders, authority, institutional support, and commitment to the environment and the territory are present in Andalusia. This entails regulatory provisions and planning tools in the field of environment and sustainability. Policy and planning tools related to CBE have been developed, along with cross-cutting policies to promote and support the CBE. In fact, stakeholders recognise that, in addition to the Andalusian Circular Bioeconomy Strategy (EABC), Andalusia has approved legislation such as the Circular Economy Law, the First Andalusian Strategy for the Olive Sector and the First Strategic Plan for Fruits and Vegetables, which include specific measures and actions that are closely aligned and consistent with the EABC. Furthermore, the EABC is also in line with other documents currently being prepared, such as the First Andalusian Strategy for the Agri-food Industry, the First Andalusian Strategy for Rural Development, and the First Andalusian Strategy for Extensive Livestock Farming.

Other Spanish regions with some progress in the CBE include Catalonia, Madrid, the Basque Country and Castilla and León, all of which have public-private cooperation structures.

Catalonia has developed the Bioeconomy Strategy of Catalonia 2030 (EBC20230), the Smart Specialisation Strategy of Catalonia (RIS3), the National Industrial Pact 2022–2025 and the Food Strategy of Catalonia 2024–2028 as models for the governance of the bioeconomy. The region has the Bioeconomy Hub of Catalonia (BIOHUBCAT). BIOHUBCAT connects and promotes public and private infrastructures, capacities, and services to facilitate the overcoming of barriers to implementing circular bioeconomy projects. At the same time, it also promotes initiatives to fill identified gaps in innovation services. BIOHUBCAT is also the one-stop shop dedicated to facilitating the generation of economic value from renewable organic resources in Catalonia, as a place where companies and entrepreneurs can find the solutions they need to develop their business model.

The Community of Madrid is in the process of developing a Circular Economy Strategy. A section dedicated to agricultural waste management is being prepared, including composting and plastics management, extensive livestock farming, manure and slurry management. The theoretical structure for public–private cooperation would be based on a territorial cluster/hub, which would include a standing committee and an expert committee.

The Basque Government in 2015 also approved the Klima 2050 (Climate Change Strategy for the Basque Country) as well as the Energy Strategy 2030 in July 2016, assuming the principle of shared responsibility that governs international policies on emissions reduction and energy transition policies. The bioeconomy is seen as an opportunity to transform certain sectors (forestry, wood, chemicals, construction, etc.), including new generation of materials, products and new business models that value the use of biological resources in the territory. It will also have a bioeconomy hub from 2023.

The region of Castilla and León has the Circular Economy Strategy 2021–2030 and the Smart Specialisation Strategy of Castilla y León (RIS3) for the development of its bioeconomy. Castilla and León is a pilot region of the European Circular Cities and Regions Initiative (CCRI), which aims to implement systemic circular economy solutions at local and regional level.

Additionally, the quadruple helix members who were consulted remarked on normative changes in European and/or national legislation to favour, stimulate, and even force the achievement of full re-use of by-products on production lines. Some changes in legislation can harden the requirements to recover or manage biomass resources. Additionally, bureaucratic burdens and excessive administrative procedures are important obstacles to entrepreneurship. Among other limitations, stakeholders highlight the following weaknesses and threats to the development of a circular bioeconomy at territorial level (Table 2).

Table 2.

Weakness and threats to the development of a circular bioeconomy at territorial level.

In addition, they highlighted that the relative disconnection between the business structure and the Andalusian knowledge system slows innovation. There is a lack of facilitating schemes to create alliances between companies, agrifood value chains, and research bodies in the field of the CBE. Furthermore, there are difficulties in defining strategies related to the CBE in the medium- and long-term in successive research programmes, with reference to a complete alignment with the national and European R&D+i policies. These difficulties limit the long term efforts and R&D+i activities in achieving sustainability. Rigid governance models in public R&D+i institutions hinder the development of the CBE.

These barriers mean difficulties in the implementation and development of projects in the territory and a lack of patents and real applications of research on CBE.

4.2. Nodality/Communication

Experts consider that there is an unawareness of what CBE is and what it represents to a great part of society. In Andalusia, there is information on the potential biomass available in the region. There are initiatives related to the CBE and publicly known by society, a fact that can be an advantage in making this society aware of its advantages and importance. This region has also cases of success that can be showcased to society as an example of the advantages of the CBE. The experts also confirmed the progressive dissemination of the new model represented by the CBE in the different centres of the Regional Ministries of Andalusia.

In this context, highlighting some examples of CBE success stories in Andalusia can be mentioned. The Operative Group Project OleoValoriza’s Circular Agro-Innovation: Integral Valorisation of Waste for a Sustainable Oil Sector envisaged the circular economy as its axis of action through the recycling and recovery of pond sludge (“alperujo”) via a composting process. The Circular Economy Observatory HORT OBSERV TIC is another initiative dedicated to promoting the adoption and growth of the circular economy in the fruit and vegetable sector. Its main objective is to collect and disseminate relevant and updated information on companies and organisations that implement sustainable and circular practices in their operations. Furthermore, it can be outlined that the ROBIN project has been honoured with the prestigious Spanish National Biocircularity Award in the Public–Private Cooperation category at the BioCircular Summit held in Madrid (February 2025), an important recognition for the collective efforts of all ROBIN’s partners, highlighting the successful and impactful collaboration between public and private sectors. This partnership has significantly contributed to advancing sustainable bio-circular business models, strengthening the project’s vital role in ecological transition. However, there is clear agreement among interviewers that there is a lack of clarity in the diffusion of the CBE concept, which hinders its understanding among the different stakeholders. Additionally, there are not enough training and skills, networking, cooperation, etc. in the CBE, to foster/boost new innovative actions. Political commitment in all areas to the bioeconomy and the circular economy favours the organisation of events and forums where contacts are established.

4.3. Treasure

During the workshops, stakeholders reported a growing interest in sustainable investment at regional, national, and European levels, and Andalusia is involved in projects related to the CBE at these levels. European Structural Funds (principally the ERDF and EAFRD) and European Investment Funds finance actions to stimulate and promote the CBE. At the national level, it is possible to fund projects through the Spanish Ministry for Economy and Business and linked entities (CDTI, INIA). Furthermore, there is a positive evolution of foreign investment in the region; however, stakeholders reported the poor involvement of the private sector in R&D+i funding. Stakeholders also mentioned possible synergies with other public funding lines available (national or European funding, such as European Investment Bank or Structural Funds) and the possibility of creating intermediate credit lines (a combination of regional public resources with others at the national or European level).

However, the lack of inter-administrative coordination and cooperation limits project funding due to the incompatibility between funds (divided by competencies). Additionally, experts highlighted the poor flexibility of existing funding instruments for Technology-based Businesses that do not consider the life cycle of business projects.

Some other weaknesses and threats mentioned during the workshops were that the R&D+i system is not very efficient in attracting and retaining human capital within the Science, Technology, and Business System, because there is growing international competence in resources, talent, technology, and attraction of R&D+i investment.

Additionally, there are restrictions on access to traditional credit instruments (loans and credits). This means a risk to R&D public sector sustainability in the current situation due to a lack of alternatives to direct financing. In conclusion, there is a shortage of alternative funding and credit options, besides problems with access to funding by the private sector, especially SMEs.

Finally, a critical point mentioned is that sustainability and the bioeconomy are focused on long-term challenges; however, R&D+i activities to identify, design and validate good governance models and practices are designed for the short-term.

4.4. Organizational Capacity

Complementary to the competencies of the Regional Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, Water and Rural Development of Andalusia, several departments are involved in the bioeconomy field. There are also working groups and clusters that include different fields related to the bioeconomy: agriculture, fisheries, forestry, R&D+i, industry, academia, environment, etc. In Andalusia, no research centre is specifically devoted to the bioeconomy or CBE. However, a large number of technology, research, and innovation centres focus their activities on one of the areas related to the bioeconomy. The technological dimension and the development of the Andalusian public sector allow it to act as a demand generator, a promoter of public procurement for innovative solutions and a driving force for companies.

Besides these previous opportunities and the potential organizational capacity of Andalusia, stakeholders mentioned inter-administrative cooperation and coordination, in addition to the general aim of involving all actors within the fourfold approach: knowledge centres, administrations, companies, and citizens. In addition, it is necessary to develop new relationships and collaboration methods and formulas for the development of innovative projects between the institutions and the companies associated with the CBE in Andalusia.

All these administrative bodies, public and private organizations work in a region with a high potential for the generation and availability of biomass resources: (1) high production capacity of biomass resources from agriculture, livestock production, agri-food, forest, and fishing sector; (2) excellent regional weather conditions for the production of biomass, although the effects of climate change can reduce this; (3) availability of other sources of biomass resources of interest that can be recovered, such as sludge from sewage systems and bio-waste produced at local level; (4) progressive optimization in the management of biomass resources generated by the agricultural and agri-food sectors due to the extensive experience that exists concerning its use in bioenergetics; (5) infrastructure and logistics management of biomass resources; (6) development of markets for bioproducts and bioenergy.

The stakeholders highlighted the experience of the Andalusian Campus of International Excellence in Agri-Food [41] (ceiA3), and research and technology transfer groups in the sectors of interest for the CBE show a strong organizational capacity. The ceiA3 is the result of the integration of the Universities of Almería, Cádiz, Huelva and Jaén, under the leadership of the University of Córdoba. These five institutions, with a strong scientific track record, contribute their expertise in the agri-food sector for the benefit of society and the productive fabric, with the aim of promoting the development of the sector and meeting the agri-food challenges of the 21st century.

In addition to these universities that constitute the ceiA3, public research centres, such as the CSIC (Higher Council for Scientific Research) and the IFAPA (Institute for Agricultural and Fisheries Research and Training), place a strong emphasis on the improvement of training and alignment with the European Higher Education Area. In this context, the consortium manages highly specialised training network courses every year. Among these, the Inter-University Master’s in Circular Bioeconomy and Sustainability, led by the Universities of Córdoba and Almería, stands out. These campuses and groups are adapting to the European priorities proposed for industrial issues, some directly related to the CBE. Furthermore, in Andalusia, there is a network of research and training centres and infrastructures on agriculture and agri-food processing, as well as technological parks related to sectors with great potential for the CBE.

The territorial actors recognised that Andalusia has a critical mass of scientific–technical staff in the field of the CBE and the knowledge, experience, human capital, technological capacity, and innovation dimensions related to the CBE, as well as of leading companies. All of this is reinforced by important driving poles for productive innovation with implications for the CBE (agri-food industry, chemical sector, renewable energies). Additionally, an important agro-industrial business fabric has the capacity to participate in bio-based processes that also have experience in certain technological developments aimed at the efficient use of resources. Furthermore, the biotechnological ecosystem favours the transformation and recovery of the biomass resources of Andalusia, including bio-industries and biorefineries on a small scale in the Andalusian rural area, and technologies for the production and use of biogas from biomass resources.

Andalusia is promoting a change in its energy system based on savings, energy efficiency and taking advantage of the region’s enormous renewable resource potential, culminating in a new carbon-neutral energy model by 2050. The different energy plans approved in the Autonomous Community have been advancing along this path of decarbonization and self-sufficiency of the energy system, intensifying the use of renewable energies, extending the culture and improvement of energy efficiency, promoting local actions and collective energy management, betting on innovation, and supporting companies and entities in their projects. The Andalusia Energy Strategy 2030, in accordance with the Andalusia Energy Guidelines for the 2030 horizon, continues to encourage the region to move towards an energy model focused on renewable energies, maximizing the energy use of the resources available in our region, increasing the welfare of people, creating jobs, and boosting economic growth and the generation of energy.

Thus, an important energy infrastructure has been developed in Andalusia, including the following: biofuel production and pellet manufacturing plants, electricity generation facilities using renewable energies, and oil refineries as energy transformation industries. Furthermore, there are 21 biogas production facilities in Andalusia with a total capacity of 33.4 MW (Mega Watts), of which 27.4 MW are connected to the grid and 6.0 MW use the biogas generated for self-consumption. Andalusia leads the biomass power generation sector in Spain, with 17 facilities totalling 274.0 MW, thanks to the significant potential provided by olive grove cultivation and its associated industries. Of particular note is the energy generated from primary forest biomass.

Other strengths in terms of organizational capacity are the importance of sectors such as organic farming, integrated production, animal feed, etc., and the potential for the production of fertilisers and other products of major added value from biomass resources (sludge from sewage systems, bio-waste produced at the local level).

To strengthen these actors, some bodies have created synergies and social communication networks with science that can disseminate the benefits of CBE to society, as mentioned below. However, the experts identified room for improvement in the exploitation of synergies between the different agents within the science, technology, and business system. They also considered that there is limited knowledge of the characteristics of a great variety of biomass resources with potential as raw materials in order to produce innovative bio-products, besides deficient management of the by-products derived from livestock production, and insufficient management of forest resources.

According to the experts, some challenges in terms of organizational capacity are (1) the weaknesses in the promotion of the products and services that shape the Andalusian productive system and, among them, those derived from activities associated with the CBE; (2) a poor number of spin-off or start-up knowledge-based companies within the CBE, compared to the size of the Andalusian system; (3) insufficient adjustment of the training offer to the needs and specificities of the professional staff working in the agricultural, food-processing, environmental, forest, and fishing sectors related to the CBE; (4) limited number of companies that use the public R&D+i system compared to its size; (5) existence of barriers to the mobility between the R&D+i staff in the public and private sectors.

In terms of logistics, the seasonal variation of biomass resources and the insufficient storage infrastructure network are also a challenge. There is also a lack of technological developments specifically adapted to every type of biological resource and industrial process, as well as volatile transport costs for certain flows of low-density biomass resources.

From the market point of view, the existence of a consolidated market for biofuels was reported. The existence of a demand already established for particular bioproducts (plant debris for composting or manure for organic amendments) can boost the demand for others. Andalusia has experience in the sustainable chemistry sector, concerning both the bioproducts that can be obtained and their current and/or potential markets, as it has been selected as a demonstrator region.

However, there is limited knowledge of alternative uses of different raw materials and their introduction in different value chains in the field of CBE and new business models and market opportunities. There is also a lack of detailed analyses concerning the potential applications of by-products and available waste of biological origin, as well as companies potentially interested in them.

5. Discussion

According to Dietz (2018), the first problem in implementing CBE is the lack of adaptation of existing institutional frameworks to the specific needs of the bioeconomy [4]. Given this, the chances are high that existing institutions are poorly aligned with the institutional demands of a rapidly developing and innovative bioeconomy. Andalusia is currently working on an action plan to update the actions of the Andalusian Circular Bioeconomy Strategy in the 2025–2030 horizon, focused on the agri-food value chain. This action plan addresses this challenge.

Rules, procedural, and structural dimensions embody the three dimensions at the regional level of governance [26,27]. The Section 4 shows a positive regulatory framework; however, it is necessary to update some previous rules to achieve better integration of complementary rules and necessary procedures, as Dietz et al., (2023) [42] state. In terms of structural dimensions, implementing these innovative and transversal strategies requires special structures but, above all, guarantees the integration of existing structures. In Andalusia, the ACBS is an instrument to align the legal framework necessary to boost the transition. However, in terms of authority, the findings section shows several challenges to address in the coming years, the tackling of which would contribute to implementing a suitable CBE model.

From the point of view of the property of being at the centre of social and information networks (nodality), there is still a long way to go for the regional government in performing a key role in communication. Currently, it has high potential (information, success cases, commitment); however, CBE is a complex and new concept, and additional effort is necessary to include it in the social vocabulary in order to bring the bioeconomy closer to society and stakeholders.

There are opportunities to fund the implementation of CBE, but these are not enough to support its potential development. This is why the CBE plan can gather all the stakeholders and lines of action to be aligned towards a common objective. The coordination of economic efforts allows more ambition in the implementation of new projects.

In this context, NGP emerges as a governance model that allows the articulation of different stakeholders to deal with the CBE. Adaptation of rules, procedures, and structures, as well as the coordination of funding, demand new governance models that engage with stakeholders and citizens in policymaking, by enabling citizens and companies to play a legitimate proactive role as collaborators and creators [29,32]. To achieve this implication, communication and nodality work as key links (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Collaborative and cooperative model among territorial stakeholders in developing a sustainable CBE governance model.

As in Dietz (2018), political support measures can aim at increasing the competitiveness of bio-based products through subsidies, thereby creating markets for the bioeconomy that do not independently develop within the economy [4]. Political support measures such as the creation of favourable legal frameworks, state-supported training of the labour force, or the promotion of industry clusters are all intended to make it more attractive for companies to invest in the bioeconomy. Finally, states can promote bio-based transformation at a societal level through deliberate political campaigns to increase the legitimacy and acceptance of the bioeconomy. Misinformation, including limited knowledge about the properties of bio-based products, or the idea of a conceptual reduction of the bioeconomy, can undermine consumer confidence. Dietz et al. (2023) [42] also highlight this point: “knowledge and capacity gaps thus present another challenge to bio-based transformation”.

There are strong organisational, funding, regulatory, and communication resources driving a transition to a CBE model, but all these resources need to be articulated to achieve the desired objectives. Andalusia has a strong organisational capacity. This organisational capacity also supports the idea of a CBE action plan.

In this context, the Regional Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, Water, and Rural Development of Andalusia is working on the development of an EABC Action Plan withing a 2025–2030 framework, focusing on the agri-food value chain. Actions and measures to be reviewed and updated include: (i) the promotion of cooperation and collaboration between key stakeholders, the creation of dedicated clusters to support the key stakeholders, (ii) the clarification of a regulatory and legal framework to take advantage of European, national, and regional funding mechanisms, (iii) the creation of good habits and practices of production based on CBE, (iv) the establishment of some standards to obtain high-quality certified products, (v) the promotion of mechanisms to optimise production costs, (vi) the development of new business models, and (vii) the provision of human resources and emerging new professions.

In terms of limitations and potential future research, the structure and theoretical approach proposed in the article are applicable to any context. However, the circular bioeconomy is closely linked to the territory, stakeholders, and natural resources of each region, so conclusions and proposals must be adapted to each region.

While the study provides a valuable analysis of the circular bioeconomy and its governance in Andalusia (Spain), we mention below some limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings and applying the conclusions in other contexts:

Representativeness bias and participant selection: The sample of stakeholders may not fully reflect the diversity of actors involved in the CBE and governance in Andalusia. Additionally, there may be a bias in the selection of participants and their availability to participate in events.

Geographical limitation: The findings of this study are centred on Andalusia, which may hinder their generalization to other regions with different geographical frameworks, sectors, value chains, regulatory, socioeconomic, and environmental frameworks. These differences may limit the applicability of the results at the national or international level.

Subjectivity of opinions: Since the study is based on stakeholder perceptions, the results may be influenced by individual or sectoral interests, affecting the objectivity of the study. Differences in the level of knowledge and experience of the interviewees may generate variability in the responses.

Dynamism of the regulatory and economic framework: The governance of the bioeconomy is an evolving field, so the results may become outdated due to regulatory changes or new political strategies at regional, national, and European levels, which may affect the viability of the recommendations.

Methodological scope: The study is based on qualitative methods (interviews, workshops, etc.), which may make it difficult to quantitatively measure the impact of the policies or strategies analyzed.

Despite the aforementioned limitations, throughout the development of the study, we have tried to consider and minimise their possible biases.

As potential future research that contributes to validating and consolidating these findings, monitoring the application of the NGP approach over a longer period than used in this study to identify its long-term socioeconomic and environmental impact in the regions (sustainability approach) could be beneficial. This allows us to assess the degree of satisfaction and alignment of the strategies and governance models with the efforts and interests of the multiple actors involved in the CBE. This question will need to be resolved in the coming years. Additionally, as a complement to this study, it could also be useful to quantify the opinions of stakeholders in Andalusia through structured surveys to design more concrete and specific policies in the field of CBE and identify key development indicators of CBE at the regional level. Another possible line of future research would be the replication of the methodological framework designed in this study through the public–private collaborative framework and territorial approach in order to advance the green transition through the principles of circular bioeconomy at the territorial level in other regions. This allows identifying similarities and differences based on the opinions of other quadruple helix stakeholders from other regions and, consequently, developing greater reflections on which to base CBE policies at the supra-regional level and promote territorial collaboration between regions.

6. Conclusions

The promotion of interregional cooperation facilitates progress in the implementation of the regional CBE within territories (RQ1). Furthermore, collaboration and integration of all key actors are essential to advance regional governance models that develop and implement the CBE to achieve sustainability. Through this collaborative approach, the deployment of co-creation actions and the exchange of good practices and support tools are essential for the success of the CBE model (RQ2). Through this cooperation, knowledge, experience, and resources are shared, strengthening the capacity to address common challenges and exploit the specific opportunities of each regional context (RQ2).

On the other hand, dissemination, communication, and awareness-raising regarding CBE are essential to achieve widespread adoption of this model, especially within civil society. Involving citizens in this process not only promotes a better understanding of the model, but also active support from the demand side, which is essential for the transformation of production systems and a more efficient and sustainable use of resources (RQ2).

Additional types of knowledge (such as “experiential knowledge”) complementing scientific knowledge may need to be integrated to form a knowledge database explicitly dedicated to sustainability. With the establishment of NPG, co-production has acquired the status of a leading practice in reformulating public service delivery. Among the many issues addressed, circularity challenges appear to be one of the policy areas in which such tools can achieve the most satisfactory results [29,43,44]. The CBE implies an NPG model, due to the need to involve different actors with different profiles, and therefore governance must enable nodality and communication strategies, treasure to support the involvement of the stakeholders, and authority to create policies and regulatory frameworks that facilitate involvement and interaction (RQ3).

In conclusion, CBE governance plays a key role and a way to coordinate the cooperation and actions between regional actors, funding entities [42], and European regions, together with the promotion of communication and awareness-raising, in supporting the transition towards the CBE and a more sustainable model.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization S.S.G. and J.L.C.; methodology S.S.G., J.L.C. and M.C., software S.S.G., E.O. and M.A.; validation, S.S.G., M.C., C.C., C.P.-L., M.G., C.R., R.D.-S., E.O., M.A. and J.L.C.; formal analysis, S.S.G., M.C., C.C., E.O. and M.A.; investigation, S.S.G., M.C., C.C., C.P.-L., M.G., C.R., R.D.-S., E.O., M.A. and J.L.C.; resources, M.C., S.S.G. and M.G.; data curation, S.S.G., J.L.C., M.C. and M.G.; writing J.L.C., S.S.G., E.O., M.A. and C.C.; original draft preparation, S.S.G., J.L.C., M.A., E.O. and M.C.; writing—review and editing, S.S.G., J.L.C., M.A., E.O., M.C., C.P.-L., M.G., C.R. and R.D.-S.; visualization, S.S.G. and J.L.C.; supervision, S.S.G., J.L.C. and M.C.; project administration M.G., C.R., R.D.-S., M.C. and S.S.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research funded by the European Commission through Grant Agreement no. 101060504, under the Horizon Europe Programme.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived due to the nature of the study, which did not concern or expose any personal information.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

This article has been developed based on the results and under the conceptual approach of the ROBIN project (Deploying circular BIOecoNomies at Regional level with a territorial approach).

Conflicts of Interest

Authors María García, Carmen Ronchel and Rafael Dueñas-Sánchez were employed by the company TRAGSATEC. Authors Esther Ortiz and Milagros Argüelles were employed by the company Technology Corporation of Andalusia. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- European Union (EU). A Sustainable Bioeconomy for Europe Strengthening the Connection Between Economy, Society and the Environment: Updated Bioeconomy Strategy. 2018. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/edace3e3-e189-11e8-b690-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- Padilla-Rivera, A.; Russo-Garrido, S.; Merveille, N. Addressing the social aspects of a circular economy: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Braun, J.; Birner, R. Designing global governance for agricultural development and food and nutrition security. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2017, 21, 265–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.; Börner, J.; Förster, J.J.; Von Braun, J. Governance of the bioeconomy: A global comparative study of national bioeconomy strategies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allain, S.; Ruault, J.F.; Moraine, M.; Madelrieux, S. The ‘bioeconomics vs. bioeconomy’ debate: Beyond criticism, advancing research fronts. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2022, 42, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junta de Andalucía. Estrategia Andaluza de Bioeconomía Circular. 2018. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/organismos/agriculturapescaaguaydesarrollorural/areas/politica-agraria-comun/desarrollo-rural/paginas/estrategia-andaluza-bioeconomia.html (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- ROBIN. Deploying Circular Bioeconomies at Regional Level with a Territorial Approach. European Union Within the Framework of the Horizon Europe Programme. 2025. Available online: https://robin-project.eu/ (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- REINWASTE. Remanufacture the Food Supply Chain by Testing Innovative Solutions for Zero Inorganic Waste. 2021. Available online: https://reinwaste.interreg-med.eu/ (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- POWER4BIO. POWER4BIO—emPOWERing Regional Stakeholders for Realising the Full Potential of European BIOeconomy. European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme. 2021. Available online: https://power4bio.eu/ (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Ferraz, D.; Pyka, A. Circular economy, bioeconomy, and sustainable development goals: A systematic literature review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bina, O. The green economy and sustainable development: An uneasy balance? Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2013, 31, 1023–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardung, M.; Cingiz, K.; Costenoble, O.; Delahaye, R.; Heijman, W.; Lovrić, M.; van Leeuwen, M.; M’barek, R.; van Meijl, H.; Piotrowski, S.; et al. Development of the circular bioeconomy: Drivers and indicators. Sustainability 2021, 13, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. Towards a Green Economy: Pathways to Sustainable Development and Poverty Eradication—A Synthesis for Policy Makers; Sustainable Development; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- D’amato, D.; Korhonen, J. Integrating the green economy, circular economy and bioeconomy in a strategic sustainability framework. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 188, 107143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad-Segura, E.; Batlles-delaFuente, A.; González-Zamar, M.D.; Belmonte-Ureña, L.J. Implications for sustainability of the joint application of bioeconomy and circular economy: A worldwide trend study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Closing the Loop—An EU Action Plan for the Circular Economy; Communication From the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wohlgemuth, R.; Twardowski, T.; Aguilar, A. Bioeconomy moving forward step by step—A global journey. New Biotechnol. 2021, 61, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Serrano, F.; Garcia-Garcia, G.; Parra-López, C.; Sayadi-Gmada, S. Sustainability, circular economy and bioeconomy: A conceptual review and integration into the notion of sustainable circular bioeconomy. New Medit 2024, 2, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayadi, S.; Cátedra, M.; Capote, C.; Parra, C.; Garcia, G.; Argüelles, M.; Ortiz, E. Análisis estratégico de la implantación de la bioeconomía circular en Andalucía a través del análisis DAFO. C3-BIOECONOMY 2023, 4, 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BioÖkonomieRat. Global Bioeconomy Summit Communiqué Global Bioeconomy Summit 2018 Innovation in the Global Bioeconomy for Sustainable and Inclusive Transformation and Wellbeing. 2018. Available online: https://gbs2018.com/fileadmin/gbs2018/GBS_2018_Report_web.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2021).

- Stark, S.; Biber-Freudenberger, L.; Dietz, T.; Escobar, N.; Förster, J.J.; Henderson, J.; Laibach, N.; Börner, J. Sustainability implications of transformation pathways for the bioeconomy. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 29, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU. Council Conclusions on a Farmer-Focused Post-2027 Common Agricultural Policy: Towards a Competitive, Crisis-Proof, Sustainable, Farmer-Friendly and Knowledge-Based Future EU Agriculture. Special Committee on Agriculture of 16 September 2024. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/mpo/2024/9/special-committee-on-agriculture-sca-(346250)/ (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- EU. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions; The European Green Deal. 2019. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:b828d165-1c22-11ea-8c1f-01aa75ed71a1.0002.02/DOC_1&format=PDF (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Junta de Andalucía. Ley 3/2023, de 30 de Marzo, de Economía Circular de Andalucía. 2023. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/boja/2023/67/BOJA23-067-00055-6439-01_00281478.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- OECD. DAC Orientations on Participatory Development and Good Governance. OCDE/GD(93)191. 1993. Available online: https://one.oecd.org/document/OCDE/GD(93)191/en/pdf (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Skondras, A.; Nastis, S.A.; Skalidi, I.; Theofilou, A.; Bakousi, A.; Mone, T.; Tsifodimou, Z.E.; Gaffey, J.; Ludgate, R.; O’connor, T.; et al. Governance Strategies for Sustainable Circular Bioeconomy Development in Europe: Insights and Typologies. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, P.; Horton, B.P. Re-defining sustainability: Living in harmony with life on Earth. One Earth 2019, 1, 86–94. [Google Scholar]

- Ingrams, A.; Piotrowski, S.; Berliner, D. Learning from our mistakes: Public management reform and the hope of open government. Perspect. Public Manag. Gov. 2020, 3, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuomo, F. Urban living lab: An experimental co-production tool to foster the circular economy. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, S.; Zaman, A. Regional cooperation in waste management: Examining Australia’s experience with inter-municipal cooperative partnerships. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, S. Theoretical approaches to measuring governance: Public administration. In Handbook on Measuring Governance; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2024; pp. 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkama, P.; Kettunen, P.; Torsteinsen, H. Organizational innovations of municipal Waste management in Finland and Norway. In Proceedings of the GSRD International Conference, Kyoto, Japan, 28 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rudnick, J.; Niles, M.; Lubell, M.; Cramer, L. A comparative analysis of governance and leadership in agricultural development policy networks. World Dev. 2019, 117, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzkowitz, H.; Leydesdorff, L. The Triple Helix–University-industry-government relations: A laboratory for knowledge based economic development. EASST Rev. 1995, 14, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Carayannis, E.G.; Campbell, D.F. ‘Mode 3’and ’Quadruple Helix’: Toward a 21st century fractal innovation ecosystem. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2009, 46, 201–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margetts, H.; John, P. How rediscovering nodality can improve democratic governance in a digital world. Public Adm. 2023, 102, 969–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuehnhanss, C.R. Nudges and nodality tools: New developments in old instruments. In Routledge Handbook of Policy Design; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 227–242. [Google Scholar]

- Hood, C.C. The Tools of Government; MacMillan: London, UK, 1983; p. 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vught Van, F.; De Boer, H. Governance models and policy instruments. In The Palgrave International Handbook of Higher Education Policy and Governance; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 2015; pp. 38–56. [Google Scholar]

- Junta de Andalucía. Foro de Bioeconomía Circular, Organizado por la Consejería de Agricultura, Pesca, Agua y Desarrollo Rural; en Colaboración con Centro Común de Investigación (JRC, Joint Research Centre) de la Comisión Europea en Sevilla y el Instituto Andaluz de Investigación y Formación Agraria, Pesquera, Alimentaria y de la Producción Ecológica (IFAPA). 2023. Available online: https://www.bioeconomiaandalucia.es/foro-de-bioeconomia-circular/ (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- Andalusian Campus of International Excellence in Agri-Food and Research. Available online: http://www.ceia3.es/ (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Dietz, T.; Rubi, K.; Deciancio, M.; Boldt, C.; Börner, J. Towards effective national and international governance for a sustainable bioeconomy: A global expert perspective. EFB Bioeconomy J. 2023, 3, 100058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogner, K.; Dahlke, J. Born to transform? German bioeconomy policy and research projects for transformations towards sustainability. Ecol. Econ. 2022, 195, 107366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotarauta, M.; Hansen, T. A competence set for sustainable urban development: Framing a research agenda. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2024, 11, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).