Abstract

Over the past two decades, walkability, accessibility, and urban street culture have become major study topics in several areas of contemporary urban research, including urban sustainability, urban economy, healthy cities, and the x-minute city. Due to a plethora of evidence that supports the benefits of an accessible and walkable neighborhood, many countries and cities have put in place urban reform agendas that prioritize accessibility and walkability and promote urban street culture. Saudi Arabia is among those countries, as evidenced by the goals established in Saudi Vision 2030. This study focuses on the City of Hail’s efforts to enhance the walkability of its neighborhoods and the city’s accessibility. This study looks at how the newly constructed pedestrian infrastructure matches people’s expectations and how it influences how people in Hail walk. This study also makes specific suggestions for improvement and identifies ways forward. This study employs a three-fold ‘post-occupancy evaluation’ methodology that includes qualitative interviews, quantitative surveys, and direct observation, focusing on how the community interacts with the new pedestrian streetscapes. This study recommends designing areas in the City of Hail with improved pedestrian rights-of-way, enhancing sidewalk design and continuity, creating pedestrian buffer zones, boosting shade and shelter, and increasing safety and security. The suggested design changes will have the added benefit of strengthening the sense of community of Hail residents while also promoting mixed-use development, which is generally recognized as a more ‘organic’, natural development path that also aligns with Saudi’s heritage architecture, returning Hail’s urban space to its roots. These findings are crucial for shaping city planning in the City of Hail and beyond by emphasizing inclusive strategies that create lively communities where walking is encouraged and enjoyed.

1. Introduction

In an era of rapid population growth and urban densification, the need for inclusive and sustainable urban development has never been more pressing. The concepts of accessibility and walkability in urban landscapes, which are foundational in cultivating vibrant, livable, and sustainable cities, are central to any urban planning effort [1]. Cities are intended to promote social cohesion, economic vitality, and environmental stewardship.

As used in this study, ‘accessibility’ refers to the degree to which residents can easily access vital services and activities, such as employment centers, educational institutions, healthcare providers, and recreational areas [2,3]. Accessibility is driven by cities’ layout, transportation networks, and land use patterns in cities. ‘Walkability’, on the other hand, refers to the extent to which city spaces are designed to be pedestrian-friendly [4]. This includes factors such as safety, comfort, and attractiveness of the pedestrian environment, which all play a role in determining whether people are inclined to walk for different reasons, such as commuting, leisure, or exercise. In addition, from a macro perspective, walkability is affected by the total length of pedestrian spaces in a city as well as the ‘nodes’ or intersections in the pedestrian environment, both of which, when increased, drive increases in the number of users, the frequency of use, and the intensity of use, driving a positive ‘network effect’. The more developed the pedestrian network, the more it is used in toto, and consequently, the higher the value of each section of the network and the overall network.

The interdependent connection between accessibility and walkability is crucial in determining the overall quality of life in an urban environment. Their interaction also significantly impacts the general public’s health, societal equity, and the environmental impact of metropolitan areas. Inaccessible and unwalkable cities can increase reliance on private vehicles, contributing to traffic congestion, air pollution, and sedentary lifestyles [5]. On the other hand, cities that prioritize accessibility and walkability can promote physical activity, social interaction, and a stronger sense of community. Additionally, accessible and walkable cities often have better access to amenities such as shops, parks, and public transportation, making them more inclusive and equitable for all residents.

In the setting of the City of Hail in Saudi Arabia, this study explores the ease of outdoor walking in the urban environment. The city’s stated goal is to blend the Hail’s infrastructure with the needs of pedestrians within the cultural context of the region. As a result, this study has two objectives: first, to assess how these newly constructed walking track areas are used through observation, and second, to understand how residents perceive and use these spaces, especially along the city-developed, busy urban walking tracks. Consistent with the 2030 Saudi Arabia Vision, this study seeks to integrate Hail City’s attractions and potential urban development with worldwide contemporary urban living standards.

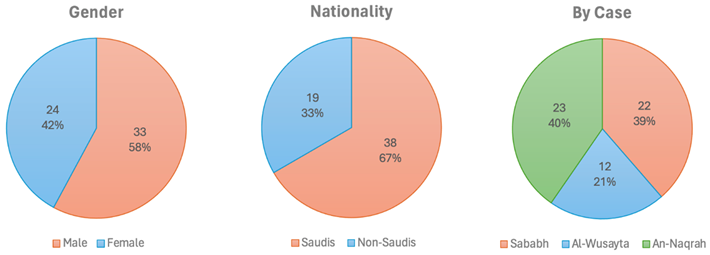

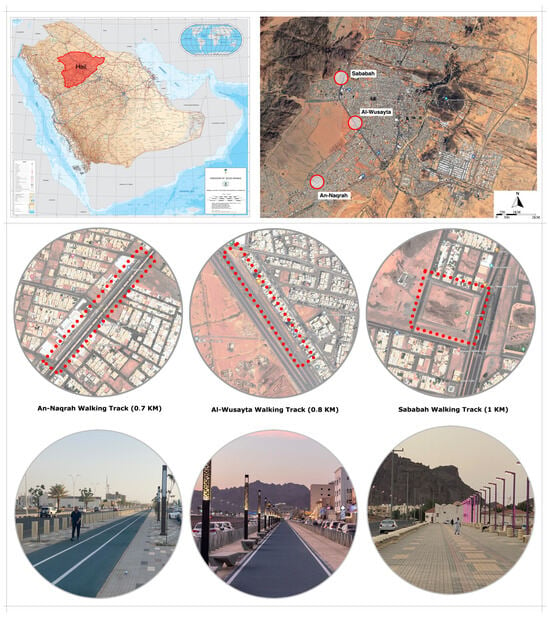

This study’s approach considers the streetscape’s physical layout and how users interact with it. It focuses on three neighborhoods: Sababah, Al-Wusayta, and An-Naqrah. The latter two neighborhoods were selected because they are two of the most recent developments within Hail, and both neighborhoods incorporate the Urban Design Department of Hail Municipality’s new approach to development. Sababah was chosen as it is one of the earlier developments in Hail, and it took a different approach, which will facilitate this study’s discussion and comparative analysis. This study evaluates each neighborhood based on ten carefully chosen urban characteristics that the literature suggests are pivotal. These criteria include aspects such as pedestrian pathways, the flow of foot traffic, sidewalk conditions, safety measures, accessibility features, and the visual appeal and practical design of urban structures. Each characteristic acts as a measure that assesses from various perspectives how easy it is to walk around the City of Hail based on resident preferences.

This study aims to assess the accessibility and walkability of Hail by examining pedestrian pathways in the Sababah, Al Wusayta, and An Naqrah neighborhoods. These areas, which showcase urban planning efforts by the Municipality of Hail, are being studied to evaluate how easily pedestrians can move around safely and comfortably. This study uses a mix of interviews, surveys, and direct observation to gather insights into how residents view and use these areas. This study’s primary goals are to highlight obstacles that hinder pedestrian flow, review accessibility features for people with disabilities, and suggest strategic enhancements to pedestrian infrastructure. Where the use of the term ‘accessibility’ here, relating to access to pedestrian facilities by people with disabilities, is different than the broader use of the word from an urban planning perspective defined earlier. This study aims to offer suggestions to city planners to develop more pedestrian-friendly neighborhoods in line with the focus on sustainable and enjoyable urban settings outlined in Saudi Vision 2030. By promoting initiatives that enhance walkability and accessibility, the aim is to establish an environment that is not only livable but also flourishing. With its investigation and analysis, this research sets the stage for future studies that can further uncover the intricacies of city landscapes, aiming for an optimal blend of tradition, practicality, and innovation in urban design.

2. A Literature Review

Cities are places of exchange, activity, communication, and collective and organized life. Concentration (density) and coexistence (commonality) are, thus, essential features of the city [6,7]. As complex entities [8,9], cities are made up of many different urban processes, one of which is daily urban mobility, which is directly related to human activity [10,11,12]. A typical daily routine includes various activities, making movement important in modern urban environments.

Walking is an important aspect of city life because it is the most essential mode of urban transportation in dense urban environments. It is free, allows for social interaction, and, thus, enables practices of encounter and exchange (economic, social, etc.) in public space. That is why infrastructure that ensures pedestrian accessibility to all citizens, including those with limited mobility, is critical for a city. Since the 1950s, the City of Hail has been transitioning from a traditional urban layout to a car-oriented built environment, limiting pedestrian movement due to heavy vehicular traffic [13]. This may be viewed as the City of Hail essentially transitioning from Ebenezer Howard’s ‘Garden City’ framework, where all parts of the city could be reached on foot within 15 min before the mass introduction of cars and trucks, to more of a Frank Lloyd Wright ‘Broadacre’ model where all parts of the city could be reached by car or truck within 15 min [14]. This shift may be attributed to the influence of rapid urbanization, the mass introduction of automobiles, and subsequent population growth within the city and in surrounding suburban areas. Due to the ‘single land use’ approach, which involves assigning a specific area to a particular activity (for example, one area is dedicated to housing; another is dedicated to businesses; a separate area is devoted to industrial use, a separate area for leisure activities, etc.), the City of Hail has been rendered by its urban design decidedly less walkable and less accessible. This urban design approach, which has become common worldwide during the past half-century, differs significantly from ‘mixed-use’ development, where various activities coexist in one area. Single land use planning aims to streamline land use management and infrastructure setup. This may result in challenges such as urban expansion, traffic congestion, and decreased social interaction due to the segregation of different land uses [15].

‘Streetscapes’ are streets’ visual and physical environments, encompassing elements such as sidewalks, street furniture, lighting, and landscaping. Well-designed streets contribute to urban spaces’ aesthetic appeal, safety, and usability [16]. ‘Walkability’ describes how conducive a location is to walking, considering elements like sidewalks, pedestrian crossings, and the proximity to amenities. A high level of walkability in a space has numerous benefits, including improved public health, reduced traffic congestion, and increased social interaction [17]. A socially and spatially healthy city is one in which inhabitants can walk safely and comfortably with various urban linkages. According to Speck’s research (2013) [18], ‘a walk must satisfy four main conditions: it must be useful, safe, comfortable, and interesting’. Comfort and safety conditions are addressed by walkability infrastructure, so these aspects are crucial when considering recreational and utilitarian walking.

2.1. The Relationship Between Accessibility and Walkability

The futuristic, planned urban area, ‘Neom’, in the far northern Red Sea province of ‘Tabuk’ in Saudi Arabia provides a helpful benchmark. ‘The Line’, a planned linear city of Neom, is intended to be car-free and ‘large enough to house nine million residents within walkable communities, with all basic services within a five-minute walking distance’ [19]. While many benchmarks may be set for ‘x-minute’ cities (5-minute, 10-minute, 15-minute, 20-minute being the most common), the benchmark for cities within the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is set: accessibility of all important services within 5 min is the goal. It should be noted that the ‘x-minute’ benchmark typically considers walking as well as cycling (and e-biking and e-scootering) [20]. As this study is focused on walkability but not cyclability, the consideration of bikes, e-bikes, and even e-scooters in the City of Hail will have to be part of a future study.

Mixed-use development is crucial in linking accessibility and walkability [21,22]. Mixed-use development promotes an environment where residents can access essential services and amenities, such as grocery stores, restaurants, and shops, in close proximity to their dwellings by incorporating different land uses within the same development, i.e., residential, commercial, and recreational spaces [23]. As discussed in Neom’s case, this proximity of essential services and amenities enabled by mixed-use development is necessary for enhancing walkability, as individuals are more inclined to walk to destinations that are easily accessible, satisfying Speck’s ‘useful’ requirement for a walk.

Walkable mixed-use neighborhoods substantially reduce car ownership and usage, decreasing greenhouse gas emissions and promoting more frequent neighborly interactions, enhancing social capital [1,24,25]. This type of urban neighborhood offers residents the chance to reside, work, and shop nearby, thereby decreasing their dependence on automobile transportation and promoting the sustainability of metropolitan areas [26].

According to previous studies, mixed-use development fundamentally impacted the social life and the walkability of cities. Urban morphologies that integrate dense and mixed-use elements have been observed to facilitate a greater number of city events and promote increased pedestrian activity [25,27,28]. This caters to daily needs and encourages participation in social gatherings. Therefore, several factors, including urban form, transportation infrastructure, land use patterns, and socioeconomic factors, are measured and analyzed as they influence the level of accessibility and walkability in urban areas (Table 1).

Table 1.

Key factors influencing the accessibility and walkability of an urban streetscape.

Regarding its pervasiveness worldwide, mixed-use development has been embraced as a paradigm shift in the field of urban planning [42,43]. Mixed-use development has been intentionally applied in many places worldwide due to its ability to meet the objectives of most modern societies: generating sustainable, livable, and dynamic urban environments by integrating residential, commercial, and cultural or recreational components into a unified development [44]. The urban form considerably impacts the functionality and attraction of mixed-use zones. Compact, well-connected urban forms with mixed-use developments improve walkability by decreasing distances between destinations and increasing the likelihood of a resident choosing walking or cycling [45]. By combining different functions within a single area, mixed-use development can reduce the need for long commutes and promote a sense of community. These integrated morphologies often bring economic benefits by attracting businesses and creating job opportunities, further enhancing the overall urban experience [46].

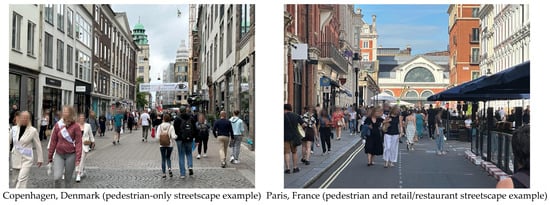

The empirical data from cities like Copenhagen and Paris, where measures to improve accessibility and walkability have been effectively put into practice, provide additional support for the underlying theoretical principles (Figure 1 provides two examples of ‘pedestrian zone’ streetscapes, where the entire space is dedicated to either pedestrian or pedestrian and outdoor retail/restaurant use) [47,48,49]. The connection between travel and urban design reveals that communities with dense development, varied land use, well-connected streets, easy access to destinations, and proximity to public transportation contribute to decreasing reliance on driving [50]. Thus, allocating resources to infrastructure that gives priority to cyclists and pedestrians, alongside urban planning that encourages the integration of different functions, compactness, and connectivity in urban areas, has been shown to greatly enhance the quality of urban life by creating cities that are easier to navigate on foot and more accessible [51,52,53]. Therefore, there is a general consensus among urban planners regarding the advantages of employing mixed-use development to enhance accessibility and walkability. These benefits encompass the environment and extend to social and economic aspects, fostering the growth of unified, thriving, and adaptable urban communities.

Figure 1.

Copenhagen and Paris ‘pedestrian zone’ streetscape examples.

2.2. Importance of Sustainable Urban Planning

In urban planning, sustainable accessibility is multidimensional, encompassing cross-sectoral planning approaches, intentional urban land-use densification, shifting transportation modalities toward walking and cycling, and ensuring proximity to daily activities [54]. These factors are critical because they help reduce residents’ reliance on private vehicles, improving urban environmental sustainability.

The importance of walkability in urban design is increasingly acknowledged as a vital factor that encourages physical activity. Although ample evidence supports the benefits of active (that is, walking, cycling, etc.) and public transportation for health, looking into the broader health implications of walkability is crucial [55,56]. The difficulties presented by the COVID-19 pandemic and environmental issues serve as examples of the growing consensus regarding the development of cities that are intelligent, adaptable, and resistant to disruption, which reinforces the focus on walkability [57,58].

Studies on walkability have diverged into separate yet interconnected areas, focusing on transportation and land utilization, urban well-being, and the creation of livable urban environments [3]. The correlation between walkability and health implies that improving pedestrian infrastructure can result in enduring health advantages, prompting a transition toward more sustainable and pedestrian-oriented urban settings [59]. Effective urban design guidelines and planning frameworks are critical for promoting mixed-use developments with improved streetscapes and walkability. Policies should emphasize pedestrian infrastructure, encourage mixed-use development, and integrate transportation planning with land-use objectives [60]. Evidence demonstrating that walkable cities foster social interaction, community engagement, and physical health supports this transition. Additionally, integrating technology and data-driven solutions in urban planning can further enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of pedestrian infrastructure, making it an integral part of future ‘smart cities’; one definition of the term ‘smart city’ is provided by the European Commission, ‘A smart city is a place where traditional networks and services (of an urban area) are made more efficient with the use of digital solutions for the benefit of its inhabitants and business’ [61].

The notion of urban walkability promotes the design of cities that can endure diverse pressures, a matter of growing significance as urban areas confront intricate socio-economic and environmental difficulties [62]. For example, Barcelona’s Superblocks Initiative has transformed the criteria for urban walkability by limiting vehicular traffic in some districts and converting specific streets into pedestrian-centric areas [63,64]. Hail may explore establishing small-scale pedestrian priority zones, especially in high-traffic areas, to enhance pedestrian mobility and safety. This method has led to increased safety, less noise pollution, and superior air quality.

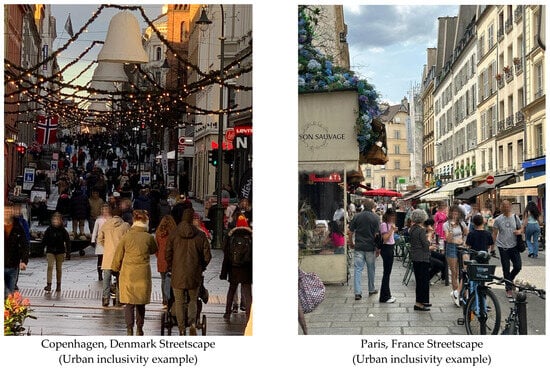

By prioritizing pedestrian infrastructure and walkability over vehicular transportation by creating dedicated or shared ‘pedestrian zones’, cities can create more inclusive and accessible spaces for all residents. This improves public health, reduces carbon emissions, and fosters community and social cohesion (Figure 2). Therefore, investing in pedestrian-friendly urban planning is crucial for building sustainable and livable cities facing complex urban challenges.

Figure 2.

Examples of European cities’ approach to the ‘pedestrian zone’ inclusive urban streetscape.

Another example is the reaction to excessive heat conditions; Melbourne has implemented urban cooling methods, including tree canopies, shade buildings, and reflecting pavement materials to combat the urban heat island effect [65,66]. This method directly tackles one of Hail’s primary challenges—insufficient shading—by illustrating how a cohesive strategy of natural and artificial shade solutions could enhance pedestrian comfort and render walking more appealing year-round.

Thus, the ramifications of walkability extend beyond physical well-being, influencing social interactions in public areas, economic aspects such as the desirability of business offerings and property values, and environmental concerns [48]. Hence, sustainable urban development is not merely an objective but an imperative, given the expanding urban population. The development and execution of strategies that advance sustainable urban development have been acknowledged as crucial since Local Agenda 21 of the Rio Earth Summit [67]. Furthermore, walkability is fundamental to sustainable urban planning and intersects with broader societal concerns such as public health, climate change, and social equity [68]. The concept’s cross-disciplinary relevance emphasizes its significance in pursuing sustainable urban development.

Overall, the implementation of sustainable urban planning, prioritizing accessibility and walkability, is crucial to the development of resilient, healthy, and habitable cities. The studies emphasize the necessity of comprehensive strategies incorporating cross-sectoral planning, advocating for sustainable transportation alternatives, and improving the pedestrian experience to accomplish wider public health, economic, and environmental goals.

3. Research Design and Methodology

The purpose of this study is to evaluate how well the role of walkability as a key urban characteristic is considered and linked to improving the City of Hail’s livability on two levels: (1) urban form and (2) user behavior and perception. Therefore, the Hail municipality developed three walking streetscapes in three separate neighborhoods in Hail City urban areas—Sababah, Al-Wusayta, and An-Naqrah—during the years 2023–2024 to meet the requirements of the ‘Saudi 2030 National Transformation Program’ and the ‘Quality of Life Program’ for Saudi Arabia’s cities [69]. As a result, this study selected these cases as representative of a recent urban development trend in the city to evaluate their walkability and the pedestrian activity they have attracted.

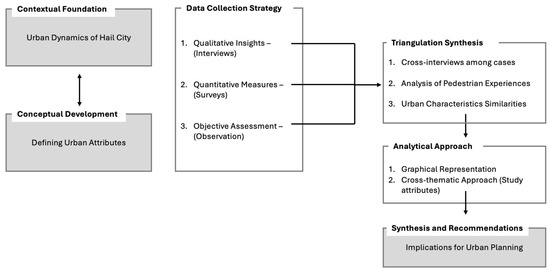

This study employs a multi-method framework based on the post-occupancy methodology, and both qualitative and quantitative methods are used to sample pedestrian streetscape activity and determine what influences pedestrian behavior, as shown in Figure 3. However, this study applies a triangulation strategy to ensure consistency and avoid potential contradictions between different data sources. This approach includes verifying the findings from the observational data, survey responses, and interview insights to look for patterns and resolve the inconsistencies. For example, suppose there are substantial discrepancies between the perceptions of respondents and the actual observational data (e.g., pedestrian flow rates). In that case, these inconsistencies are examined within the context of the broader urban environment, as well as other factors such as time, weather conditions, and the influence of society on pedestrian behavior. Additionally, the qualitative interview data were thematically coded and compared to the quantitative survey results to ascertain whether there were any perceptual biases in the responses. This meticulous methodological approach ensures that the results accurately reflect the qualitative experience of users and the quantitative measurement of pedestrian movement, thereby providing a comprehensive understanding of walkability in Hail.

Figure 3.

This study’s methodological framework.

3.1. This Study’s Context

The City of Hail, located in the central region of Saudi Arabia, stands out as a significant urban hub with rich historical, geographical, and socioeconomic aspects that shape its growth and future outlook. Figure 4 shows the location of the three selected neighborhoods within Hail. The city is surrounded by the Aja and Salma Mountain ranges and strategically positioned as the ‘gateway to the desert’. Hail has been a meeting point for pilgrims and traders moving through the Arabian Peninsula for centuries. This unique geographic location influences the city’s weather and natural beauty and plays a vital role in its cultural development and layout [70]. Situated at an elevation of 915 m (3002 feet) above sea level, Hail enjoys a moderate climate, providing an exceptional backdrop for urban expansion that blends nature’s charm with historical importance [71].

Figure 4.

Hail City and the three case study locations.

The population of Hail, recorded at 670,000 in the 2022 census, showcases a diverse and expanding community that adds vibrancy to urban life [72]. This demographic diversity, combined with the city’s topography, has impacted how Hail has grown over time regarding land use patterns, infrastructure development, and overall spatial organization. The city’s economic landscape thrives on the agriculture, industry, and services sectors—a multifaceted foundation that positions it as a key player in national growth initiatives.

Moreover, Hail’s involvement in Saudi Arabia’s efforts toward sustainable urban development, driven by initiatives such as the Future Saudi Cities Program, supports the national goal of promoting balanced regional progress [73]. This enhances its potential for urban strength and prosperity. Looking forward, the City of Hail is on the brink of significant urban and socioeconomic advancements, driven by careful planning and investments in infrastructure, education, and economic variety.

The execution of the Future Saudi Cities Program in Hail and the city’s commitment to achieving Saudi Vision 2030 goals demonstrate an approach to urban growth that emphasizes sustainability, connectivity, and preservation of cultural heritage [74]. As Hail faces the challenges and opportunities brought by urbanization and modernization, its upcoming cityscape is set to embody a fusion of tradition and innovation. This ensures that the city remains significant within the Kingdom’s framework of urban areas while bolstering its resilience against changing environmental and socioeconomic conditions.

3.2. Urban Attributes

This study employs ten urban attributes in its approach, which are supported by imagery and observation to ensure uniformity while comparing the three different cases (Table 2):

Table 2.

Study attributes and the indicators of each attribute.

- The attribute of ‘Right-of-Way’ determines the priority granted to pedestrians or cars, exerting an impact on the movement and safety of the vicinity;

- ‘Pedestrian Flow’ analyzes the movement of individuals on foot, considering the quantity, velocity, and ease of movement of pedestrian traffic;

- The attribute of ‘Sidewalk and Obstructions’ examines the state and width of the sidewalks, as well as any obstacles that may obstruct movement;

- The attribute of ‘Vehicle Traffic’ quantifies the influence of the movement and congestion of vehicles, as well as how it interacts with areas designated for pedestrians;

- The attribute of ‘Safety’ encompasses the comprehensive protection of the space considering the probability of accidents and the existence of safety measures;

- ‘Accessibility’ refers to the ease with which individuals with disabilities or other specific requirements can navigate a given space;

- The ‘Buffer Zone’ feature analyzes the intermediary regions between pedestrian and vehicular zones, encompassing landscaping or parking spaces;

- The concept of ‘Shading’ takes into account the presence of shade, which has an impact on the level of comfort experienced by users. The purpose of ‘Barrier Design’ is to assess the efficacy of physical structures in separating various areas or guiding the flow of movement;

- Finally, the attribute of ‘Maintenance and Cleanliness’ pertains to the maintenance, cleanliness, and condition of the place and its infrastructure.

Collectively, these attributes facilitate a methodical assessment of the walkability and accessibility of the three Hail case studies and serve as a standardized framework for evaluating various urban areas consistently and comparatively, which is especially beneficial in survey-based research [25].

3.3. Interviews

To understand how residents in the City of Hail perceive streetscapes and walkability, we interviewed a group of residents in each case. The goal was to explore their experiences and the perspectives that shape their preferences and decisions regarding walking. We used a structured interview format to allow participants to share their thoughts while ensuring that we covered all relevant topics and maintained a high level of consistency in questioning across the three cases. The interview followed the guide shown in Table 3. To obtain a comprehensive comprehension of the pedestrian experiences in Hail, the participants were deliberately selected to represent a variety of demographics, including age, gender, and mobility level.

Table 3.

This study’s interview questions, sampling count, and sampling distribution.

Nevertheless, due to the limited sample size in Al-Wusayta (n = 13), supplementary qualitative interviews were performed in the two case study areas, Sababah and An-Naqrah, to enhance the Al-Wusayta comparative analysis. This analytical approach was selected for two principal reasons: pedestrian experiences and actions in comparable urban environments might yield transferable insights, especially when examining common urban characteristics such as walkability, accessibility, and safety. Supplementary interviews at Sababah and An-Naqrah facilitated a more profound contextualization of Al-Wusayta’s difficulties within the wider urban landscape of Hail. Participants in these areas were explicitly requested to consider their views on Al-Wusayta’s walkability, either based on personal experience or comparative observations of neighboring localities. This cross-case validation guarantees a comprehensive and multifaceted study, mitigating bias linked to limited sample numbers in Al-Wusayta.

The interviews delved into individuals’ experiences with walking in the city, identified obstacles and factors that make walking more manageable or difficult, and gathered suggestions for enhancing pedestrian infrastructure. This approach sheds light on the cultural influences affecting walking habits, which is essential for developing strategies promoting walking and improving urban walkability.

This study’s questionnaires were created using an interview style and a survey approach. The interview format allowed participants to express their thoughts openly while ensuring all important topics were addressed. The design of these questionnaires included identifying urban factors that impact walkability based on the existing literature. The interviewees answered questions through speech during face-to-face interactions. The data collection methods included shorthand writing to take quick notes during interviews for immediate reference and written forms to ensure accuracy and for further analysis.

3.4. Survey

A survey was conducted in Hail to assess pedestrian activity and evaluate how easy it is to walk in the city (Table 4). This survey involved asking residents questions derived from the interview questions about how often they walk, the condition of tracks, their perceptions of safety, and their overall satisfaction with the pedestrian environment. Ranking systems were used to gather opinions and experiences from respondents using this study’s attributes as the main drivers for the questions. Local people’s views on walkability features were collected using a Likert scale design survey with participants using Google Forms. Although the total survey sample size (n = 673) is sufficient for a relatively robust statistical analysis, the Al-Wusayta (n = 13) sample is relatively small. To this end, the survey results in Al-Wusayta were interpreted together with the observational findings and compared with the larger datasets obtained in Sababah and An-Naqrah. This approach allowed for the incorporation of the responses and reduced the effects of the limitations in sample size on this study’s findings. A chi-square test was used to analyze correlations between categorical data (e.g., safety and place). In contrast, internal regression models were performed to determine the effect of urban characteristics, including shade, sidewalk continuity, and vehicle approach, on overall walkability satisfaction [75]. These statistical tests were performed to determine the strength and significance of relationships within the dataset so as not to rely solely on the percentage-based descriptive analysis found through the data.

Table 4.

This study’s survey attributes and proposed keyword descriptions.

These methods enabled participants to assess and rate elements of the pedestrian environment, offering a quantifiable means of evaluating the information gathered. By analyzing the data collected through these methods, researchers uncovered trends, preferences, and key factors influencing walkability in Hail. The ranking systems used in the surveys were based on this study’s attributes and provided keywords. These systems allowed respondents to rank the importance or satisfaction level of various attributes, which helped them understand the relative importance of different factors affecting walkability. This analysis complemented insights from interviews, creating a strong foundation for urban planning decisions focused on enhancing pedestrian accessibility and walkability.

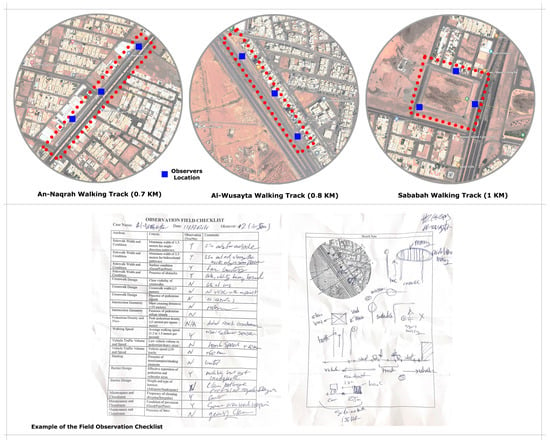

3.5. Observation

Naturalistic covert observations were performed to determine the walkability of the chosen neighborhoods in Hail City. They were purposely timed for peak pedestrian traffic (4–5 pm, after work, and 8–9 pm, after sunset, when the cool weather drives people out). Nevertheless, the researchers realize that these narrow time windows might not capture the whole picture of the dynamics of pedestrian usage during the rest of the day. Hence, to overcome this concern, the observational findings were cross-validated against the qualitative interviews and quantitative survey data to understand the observed patterns in light of broader community experiences.

The observation spots were strategically selected to ensure a clear view of the pedestrians with a maximum field of vision that covered as large an area as possible (Figure 5). The researchers recorded pedestrian traffic, sidewalk conditions, interactions between pedestrians and vehicles, and the availability and quality of amenities like shading, seating, and signage. This approach allowed the researchers to gather real-time data on how pedestrian infrastructure is used and identify factors influencing walking behavior.

Figure 5.

This study’s observers’ locations and checklist sample.

To avoid potential bias, the observational results were completed and validated by insights gathered from the qualitative interviews and quantitative surveys, thus providing a more holistic representation of pedestrian patterns at different times of the day. Also, checklists and mapping techniques were used to document what was observed, ensuring consistency across different locations and times. By combining data with subjective perceptions from interviews and surveys, we comprehensively understood the current status of walkability in Hail. This information helps pinpoint areas that need improvement and guides targeted efforts to enhance pedestrian environments.

Through observation, the geometric and quantitative aspects of pedestrian infrastructure were meticulously collected using a combination of mobile GPS trackers, digital cameras, pedestrian counts, speed sensors, and survey instruments (Table 5). The evaluation encompasses key parameters such as sidewalk width and condition, crosswalk design, intersection geometry, pedestrian density and flow, walking speed, and vehicle traffic volume and speed. Geometric data were mapped and analyzed using Google Earth Pro software (7.3.6.10201), while quantitative data underwent survey analysis to identify pedestrian experience. This integrated methodology aims to enrich the discussion and provide actionable insights and recommendations to enhance pedestrian safety, comfort, and accessibility, ultimately improving walkability in Hail.

Table 5.

Comprehensive evaluation of geometric and quantitative aspects for each attribute.

3.6. Statistical Analysis

To assess the walkability attributes across the three case studies, statistical analyses were performed on the survey data (n = 673) collected from residents in Al-Wusayta, Sababah, and An-Naqrah. The analysis followed a structured approach:

- Descriptive Statistics were used to summarize mean scores and standard deviations across all walkability attributes;

- Chi-square tests (χ2) were conducted to examine associations between categorical variables such as perceived safety, shading adequacy, and buffer zone effectiveness across the three cases;

- One-way ANOVA was used to determine whether statistically significant differences existed between the three case studies in terms of overall walkability ratings, pedestrian flow, and accessibility scores. Post-hoc Tukey’s HSD tests were applied where necessary to assess differences between individual pairs;

- Multiple Regression Analysis was performed to assess the impact of key urban walkability attributes (sidewalk continuity, shading, vehicle proximity, and pedestrian priority) on overall walkability satisfaction scores. Standardized beta coefficients (β), significance levels (p-values), and adjusted R2 values were reported to indicate the strength and explanatory power of the models.

4. Result: City of Hail Walkability Activity

4.1. The An-Naqrah Case

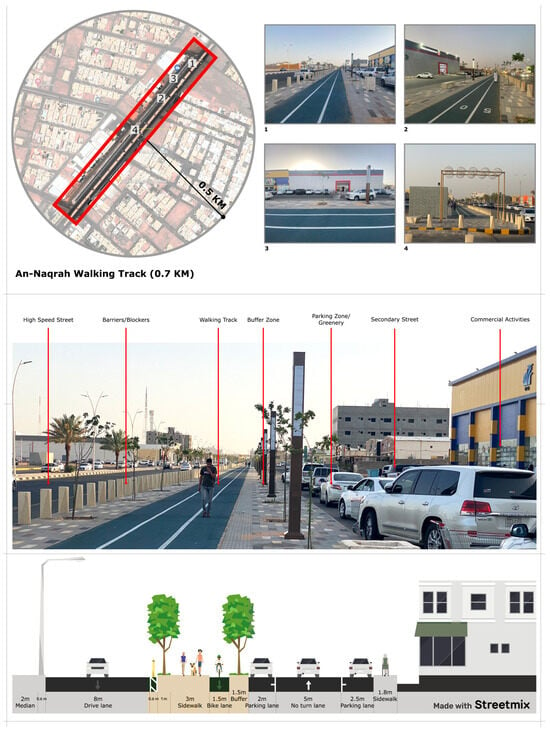

The An-Naqrah streetscape is located on one of the busiest roads in Hail City. This is evident from the lack of visible crosswalks and pedestrian signals at intersections, which poses a significant hazard to pedestrians. In the absence of these visual aids, drivers may lack awareness of pedestrian crossing points, thereby heightening the probability of accidents. This is particularly vital in areas where pedestrians are likely to cross in order to reach the walking path or continue their journey (Figure 6). Consequently, the existing pedestrian flow design needs to accommodate the anticipated pedestrian traffic patterns, posing a significant concern, especially in urban residential areas. Inadequate precautions in walkway design can lead to hazardous encounters between pedestrians and vehicles, as pedestrians are directed into the paths of oncoming traffic.

Figure 6.

An-Naqrah study observation.

Notable discrepancies in the pavement were observed, particularly at points where pedestrians and vehicles cross paths, leading to ambiguity and possible dangers. Uninterrupted and unambiguous routes are crucial for ensuring the safety of pedestrians, enabling them to move through urban areas without encountering unforeseen diversions or obstacles that could potentially put them at risk. Hence, the streetscape is situated in a predominantly inaccessible area, trapped between crowded roads, and the absence of amenities accommodating individuals with disabilities, such as tactile paving or ramped curbs, demonstrates a lack of consideration for inclusive design (Table 6). These features are essential to ensure the walking streetscape is accessible to individuals of all mobility levels.

Table 6.

An-Naqrah case observational attributes.

Hence, the proximity of the walking streetscape to vehicular traffic and parking areas, without a physical barrier, is cause for concern. In the event of a vehicle experiencing sudden acceleration or deviating from its intended path, pedestrians on the walking track would be exposed to danger, underscoring the necessity of implementing a dedicated barrier to serve as a protective buffer. Furthermore, at the intersections of the walking track and vehicular paths, the absence of conspicuous visual indicators, such as colored pavements or elevated crossings, does not effectively notify drivers of pedestrian areas, potentially resulting in pedestrian injury. Installation of pedestrian-initiated flashing crossing signals would also be helpful. These characteristics are crucial for enhancing the prominence of areas designated for pedestrians and encouraging vigilant driving habits. The proximity between the walking track and vehicle lanes is worrisome, as it offers pedestrians minimal protection. This suggests the necessity for a wider separation area or additional protective barriers.

The absence of shade and the presence of direct sunlight, with only a minimal amount of shade, made the streetscape uncomfortable or impractical to use in hot weather, thereby discouraging its utilization. Note that if the walking tracks were not separated from the built environment but integrated, built forms would provide a certain amount of natural shading for the walking spaces. Furthermore, the lack of consistency in the design of the barriers along the walking track implies that there may be a need to ensure uniform safety measures. Taller barriers are more effective than shorter ones in preventing vehicles from passing through, resulting in inconsistent safety zones along the track.

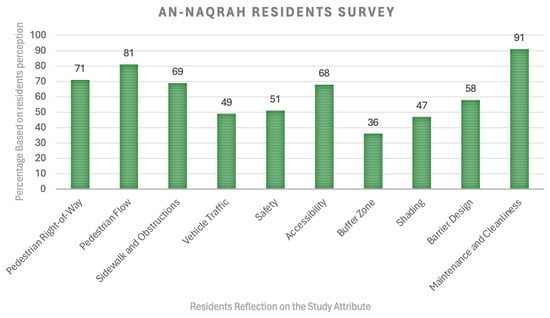

The survey poll in (Figure 7) for the An-Naqrah walking track revealed varied perceptions from residents regarding its walkability and amenities. A total of 71% of residents felt the pedestrian right-of-way was adequately addressed, and 81% were satisfied with the pedestrian flow. However, 69% were dissatisfied with sidewalk conditions and obstructions, suggesting some users encounter issues. Vehicle traffic was less positive, with 49% satisfied, suggesting potential conflicts between pedestrian zones and vehicular pathways. Safety was perceived positively by 51%, while accessibility was easy for 68% of residents. The buffer zone, which serves as a protective space between pedestrians and vehicles, only convinced 36% of respondents of its adequacy, indicating a need for improvement. The track also fell short in providing shade, with 47% of those surveyed satisfied, indicating a need for improvement. Barrier design only satisfied 58% of survey participants, suggesting potential improvements. Maintenance and cleanliness received high marks, with 91% of residents satisfied, indicating adequate upkeep and management of the space.

Figure 7.

Community perception of this study’s attributes related to the An-Naqrah streetscape.

In summary, the An-Naqrah walking track is well-received for its upkeep and the smooth flow of pedestrian traffic. However, the survey highlights attributes that could be enhanced, including improving safety measures, making buffer zones more effective, and providing better shading along the trail. By addressing these issues, user satisfaction could greatly improve, creating a more pleasant walking experience for all An-Naqrah residents.

Despite the presence of various safety and usability concerns for pedestrians, the An-Naqrah streetscape also exhibits several notable advantages. The walking track and adjacent bicycle lane are conspicuously delineated and precisely defined, which is commendable for fostering orderly utilization. The demarcation ensures that cyclists and pedestrians can utilize the area without impeding one another, bolstering safety for all individuals using the facility. In addition, implementing landscaping initiatives, such as the strategic placement of young trees along the streetscape, will eventually provide shade and enhance a pleasant and verdant urban setting. The dedication to creating and maintaining green areas is praiseworthy and will improve air purity while providing a more pleasant walking experience.

The track offers a generous expanse devoid of congestion, affording pedestrians abundant space to stroll at their preferred speed without experiencing any sense of confinement. The ample space is especially advantageous during busy periods or when implementing social distancing measures. The walking area exhibits a contemporary and aesthetically pleasing appearance. Employing diverse paving patterns and materials results in an aesthetically pleasing urban environment that entices residents and visitors to utilize the amenities for leisure and transportation.

While separated by parking and a secondary street, the proximity of the walking track to commercial amenities and services facilitates the seamless integration of exercise into individuals’ daily routines, such as walking to nearby shops or cafes. Installing light poles at regular intervals suggests that the area is adequately illuminated during nighttime, ensuring safety and enhancing its usability during evening hours. Significantly, the infrastructure is in excellent condition, exhibiting no apparent deterioration to the pavement or the benches. This signifies a degree of attentiveness and upkeep that enhances overall user satisfaction. Therefore, more integrated pedestrian infrastructure with retail shops and cafes would facilitate ‘window shopping’ and reviewing restaurant or café menus, which is precluded by separating pedestrians and cyclists from the shops and cafes in this streetscape. Perhaps discreet directories/displays could be added to the walking/cycling track to inform pedestrians and cyclists of the menus and wares of businesses on the other side of the parked cars and street, facilitating commerce and customer service.

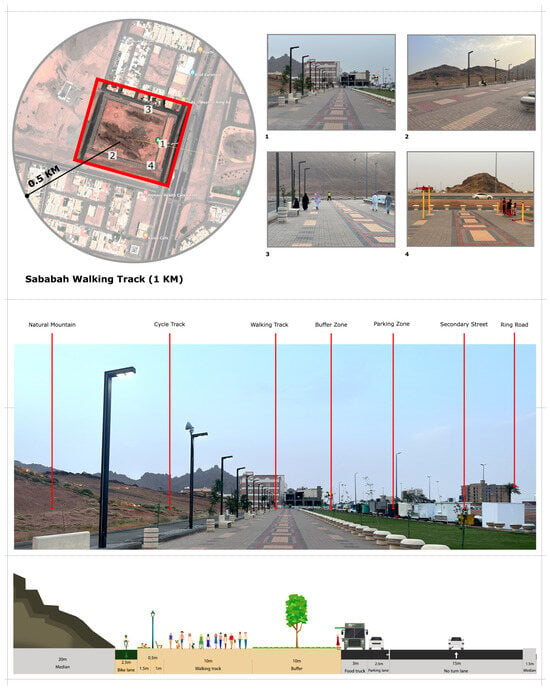

4.2. The Sababah Case

The design of the Sababah walking track is a good example of using natural resources in urban design. The site is integrated with a surrounding mountain formation, and the walking track circles around it, providing residents with a scenic view (Figure 8). However, during the site visits, it was observed that the Sababah walking track requires improvements to provide for pedestrian safety and convenience. Similar to the observations made on the An-Naqrah streetscape, the presence of clearly designated crosswalks and pedestrian signals at intersections is sorely lacking. Due to the four main roads surrounding the area, using symbols and signals is of utmost importance to ensure safe entry to and exit from the walking track for pedestrians, particularly when the only means of accessing the walking track is from the opposite side of the street. This is noteworthy because, while the walking track is situated near commercial establishments, which is convenient, its layout does not accommodate the organic movement of pedestrians. As a result, both pedestrians and the local commercial establishments fail to benefit from their proximity. Given the roads surrounding this walking track, better crossings and better signage may not be adequate for pedestrian and cyclist safety, and pedestrian and cyclist underpasses and/or overpasses may be needed. Therefore, in urban areas, it is imperative to ensure that pedestrian pathways are designed to safely direct individuals away from vehicular traffic rather than toward it, making it convenient for pedestrians to frequent the nearby local businesses.

Figure 8.

Sababah study observation.

The lack of a barrier between the walking track and parking areas nearby is disturbing, even though the residents asserted that the track is wide and ensures a safe distance between the traffic and the walking area. Similarly, gaps and inconsistencies at the intersections of sidewalks and vehicle access points lead to confusion and pose a significant safety risk. While that is the case, the residents asserted that the high linkage of track paths encourages less interference with the traffic intersection. As a result, they did not perceive it as a significant issue. This absence of safety and sudden interruptions among various urban elements may render accessibility to the pedestrian infrastructure hazardous—the deficiency in amenities such as tactile paving is used by visually impaired pedestrians. Ramps provide easy access for those who use a wheelchair and cyclists to ensure pedestrian safety and facilitate mobility (Table 7).

Table 7.

Sababah case observational attributes.

Despite landscaping efforts, the limited shade along the streetscape may discourage its use in hot weather. Ensuring the streetscape is comfortable and functional throughout the day while providing shaded areas is essential. However, it is necessary to enhance the buffer zone separating the streetscape from the vehicular lanes. Additionally, there is a need for uniformity in the design of barriers along the track, as the current varying heights result in inconsistent protection against vehicles and compromise safety. Nevertheless, the track’s general state indicates a strong dedication to cleanliness and maintenance.

Although there are valid safety and connectivity concerns for pedestrians, it is important to acknowledge the numerous positive aspects of the Sababah walking track and its surrounding environment. The facility’s location is aesthetically pleasing, with picturesque mountain views, creating a visually appealing environment that enhances the experience for individuals who walk or jog. In addition, efforts have been undertaken to incorporate vegetation and landscaping alongside the track, enhancing the area’s aesthetic appeal and providing potential shade as the trees reach maturity. Notably, the track’s flat and uninterrupted paths and spacious surfaces without any steps ensure accessibility for individuals using strollers, wheelchairs, or anyone with mobility challenges.

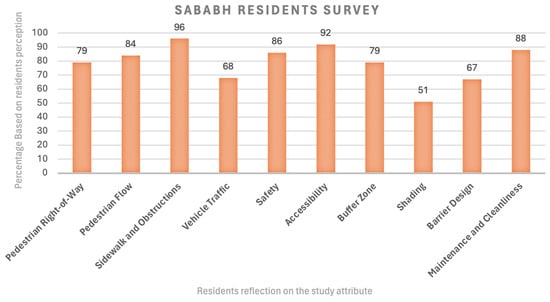

As a result, the survey on the Sababah walking track indicates that most residents are satisfied with its walkability and overall user experience (Figure 9). Most residents, 79%, feel that the pedestrian right-of-way is respected, while 84% have provided positive feedback on the pedestrian flow (Figure 9). Virtually all respondents (96%) believe that the sidewalks are clear from obstructions, ensuring a favorable walking experience. However, there is room for improvement in managing vehicle traffic, according to 68% of residents. Safety is perceived positively by 86% of respondents; accessibility receives a rating of 92%, and buffer zones are viewed favorably. On the other hand, shading stands out as an area that needs more attention. Residents show a preference for barrier design at 67%, and an overwhelming majority (88%) appreciate the maintenance and cleanliness efforts in place.

Figure 9.

Community perception of this study’s walkability attributes related to the Sababah walking track.

Recreational amenities, such as playgrounds, outdoor fitness equipment adjacent to the walking path, and seating areas, are conveniently located at multiple intervals along the track. These facilities provide opportunities for individuals to take a pause or appreciate the environment. The track exhibits ample width, allowing numerous pedestrians to stroll alongside or overtake each other without experiencing crowding, a particularly advantageous feature in a busy area. These urban features enhance the recreational appeal of the area, fostering a healthy way of life for individuals and creating a family-friendly environment.

Despite the varying designs of the barriers, their consistent presence along the track demonstrates a recognition of the importance of implementing protective measures to separate pedestrians from vehicular traffic. Additionally, the track is furnished with streetlights, indicating that the area is adequately illuminated during the evenings, ensuring the safety of users and extending the track’s operational period.

During weekends, the walking track functions as a central gathering place for the community, attracting individuals for physical activity and social engagement, thereby promoting community well-being and unity. The track and its immediate surroundings generally exhibit cleanliness and proper upkeep, demonstrating a dedication to ensuring a pleasant and sanitary setting for the public. Hence, these characteristics imply that the Sababah walking track is a valuable resource for the nearby community, providing a versatile area that fosters physical and mental health and social engagement in an enjoyable environment.

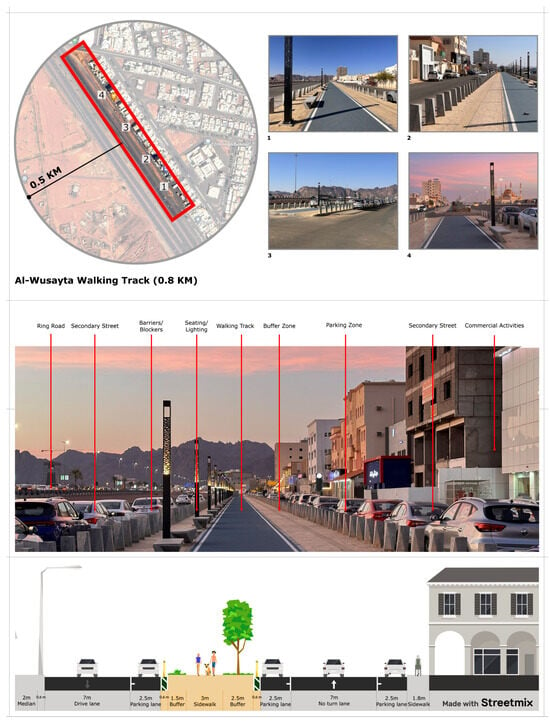

4.3. The Al-Wusayta Case

The urban streetscape of Al-Wusayta reflects a spatial organization that segregates pedestrian pathways from vehicular lanes through bollards and differentiated paving material and color (Figure 10). This design approach, in theory, promotes safety and order, but in practice, it falls short of accommodating the probable volume of foot traffic and the necessary sociological comforts for users as they are in proximity to heavy vehicular traffic. This was clear as transportation and access have been addressed with a clear bias toward vehicular movement, with a lack of evident provision for public transit limiting the streetscape’s sustainability profile. Implementing green spaces is a significant oversight, as urban greenery could reduce the area’s carbon footprint, soften the starkness of the hardscape, offer aesthetic appeal, and mitigate the urban heat island effect.

Figure 10.

The Al-Wusayta streetscape design.

The pedestrian track’s clear separation ensures pedestrian right-of-way. Yet, the absence of explicit signage or outlined rules to enforce this right-of-way could lead to potential conflicts, especially between high-speed roads and at busy intersections or points of interaction with vehicular traffic. The width of the track might accommodate the pedestrian flow comfortably under normal conditions; however, during peak hours or when cyclists are present, this could lead to congestion and possible safety risks if the space is meant to be shared. During an interview, when asked about the positive and negative aspects of this case’s streetscape, citizens appreciated the clarity between the walking path and the road; however, they indicated that it feels unsafe; the pathway is too narrow, and it is visually open to the street without any green belt obstructions. Another interviewee mentioned that the clean and orderly streetscape is a plus; it looks good and feels modern. However, the lack of safety and security for vehicles is a downside.

Sidewalk continuity is generally good and essential for uninterrupted pedestrian movement, but poles and utility boxes along the path can be hazardous. These obstructions interrupt the flow and pose significant risks to visually impaired pedestrians who rely on a clear path for safe navigation. Also, the proximity of the walking track to the vehicle lane, without a substantial physical barrier, raises safety concerns. Pedestrians could be at risk from careless vehicles, and the proximity can also be unsettling for walkers, as the close passage of vehicles can be intimidating and uncomfortable (Table 8).

Table 8.

Al-Wusayta case observational attributes.

A notable safety omission is a lack of marked crosswalks or traffic-calming measures at intersections. These are necessary for pedestrians to have clear guidance or protection when crossing, increasing the risk of accidents. This makes accessibility features seem lacking, with no tactile paving for the visually impaired, curb cuts for wheelchairs, or ramp access. This oversight excludes a significant portion of the population from using the track safely and comfortably, which is not in line with inclusive design principles. This aligns with users mentioning that they use it regularly for exercise but do not linger because there are no comfortable places to sit, rest, or enjoy the view, and the streetscape’s connectivity with the surrounding area is lacking.

It is noticed that the bollards are meant to provide a buffer zone; however, they do not provide separation from the roadway as their spacing and design may not be adequate for preventing accidents, particularly in the case of high-speed vehicle impacts. Thus, their inconsistent placement and potential to be a tripping hazard also detract from their effectiveness. This made the streetscape not very welcoming or interesting as it lacked basic urban features.

As observed in other cases, Al-Wusayta’s streetscape also lacks shade, which leads to uncomfortable conditions during hot weather, potentially deterring its use during certain times of the day and decreasing pedestrian traffic. Lastly, the maintenance and cleanliness of the track are commendable, reflecting a well-kept area that is inviting to users. Such maintenance must be sustained to ensure the track remains safe and usable in the long term.

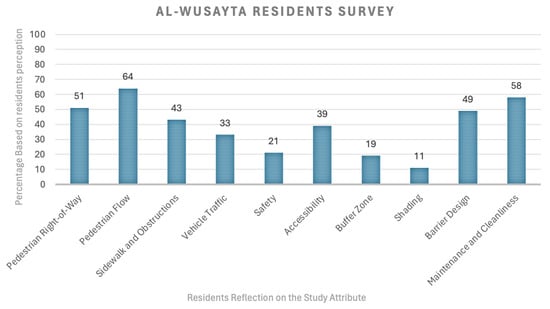

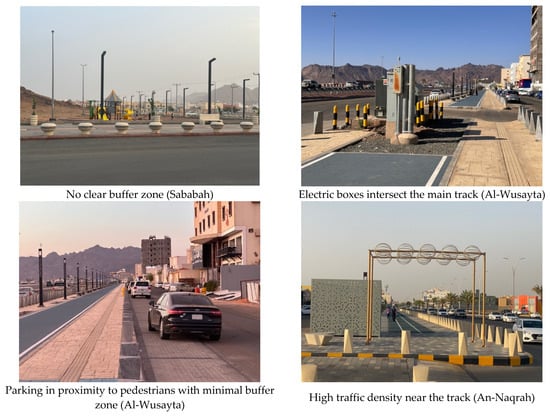

The survey results in (Figure 11) from the Al-Wusayta walking track reveal residents’ satisfaction with the current infrastructure. A total of 51% believe that the right-of-way is adequately maintained, while 64% report the track has a positive pedestrian flow. However, only 43% feel the track’s sidewalks are free of obstructions, indicating a need for better design of future infrastructure investments, as well as the need to redesign this track (e.g., the abrupt interruption of the track for electrical boxes as seen in (Figure 12) is an obstruction that could have been prevented by having the track go around the boxes rather than the current design). Only 33% of survey respondents are satisfied with vehicle traffic management, suggesting a conflict between pedestrian and vehicle spaces. Safety is a concern, with only 21% feeling that the track is safe. Accessibility is positive, but only 19% consider the buffer zone for pedestrian safety.

Figure 11.

Community perception of this study’s attributes of the Al-Wusayta walking track.

Figure 12.

Observed repetitive issues within this study’s cases.

The Al-Wusayta walking path, in conclusion, contains both positive and negative aspects. Although the number of people walking the track and its upkeep are generally fine, some attributes need serious attention, such as safety, managing vehicle traffic, designing barriers, and especially providing shade and buffer zones. While providing shade via Indigenous plants is possible, other options, such as ‘shade sails’, ‘porticos’, ‘pergolas’, etc., can provide shade immediately (rather than waiting for years for shade trees to grow) and do not require irrigation. This survey clearly shows that targeted improvements are necessary to make the walking path safer, more comfortable, and better overall. It is important to focus on safety measures, traffic control, and creating an environment to make the area more welcoming and inclusive for everyone in the community.

The qualitative data concerning Al-Wusayta were augmented by interviews carried out in the Sababah and An-Naqrah localities. This methodology facilitated cross-case insights, wherein respondents, including those acquainted with Al-Wusayta’s walkability conditions, offered indirect validation of its accessibility, pedestrian comfort, and urban safety. This comparison research revealed that although Al-Wusayta features distinct pedestrian routes, its absence of shaded spaces and inadequate buffer zones are significant restrictions affecting user comfort and safety perceptions.

Despite the challenges brought about by its design, the Al-Wusayta track is well-maintained and exhibits high cleanliness, contributing to an inviting atmosphere for pedestrians. Being near dense commercial venues, the sidewalk maintains consistent continuity, facilitating a seamless flow that promotes walking as a means of transportation. Bollards provide a level of segregation between pedestrians and vehicular traffic, thereby enhancing the perception of safety. The track’s width is ample, allowing for substantial pedestrian traffic, which is advantageous during peak periods. The clearly defined lanes ensure pedestrians have an unobstructed pathway, promoting order and discipline in the shared space. Significantly, the track offers a (mostly) continuous route that promotes physical exercise and can be regarded as a valuable resource for the community. It is important to consider the track’s overall design and well-maintained state to promote a pedestrian-friendly environment and positively contribute to urban living standards.

5. Discussion

While the three streetscapes studied each display an organized and well-intentioned design, the cases showcased a misunderstanding by the City of Hail of the concept of an urban streetscape (Figure 12). This claim is supported by the interviews of streetscape users and site observations conducted regarding each case. All cases exhibited a lack of placement and connectivity with the surrounding urban form, which led each streetscape to be isolated from the surrounding or proximate commercial land use activities. Thus, future design (or redesign) efforts will require a more pedestrian-centric approach emphasizing comfort, greenery area balance, and multi-modal connectivity options to evolve the space into a more sustainable and user-friendly urban environment.

An analysis of the three cases—Sababah, Al-Wusayta, and An-Naqrah—identifies many shared walkability constraints that limit pedestrian mobility in Hail City. A primary disadvantage is the lack of adequate shading, as all three locations lack trees and offer minimal to no constructed shade. This constraint is particularly problematic in warmer climates, as direct sunlight deters pedestrian activity at peak times. Consequently, while each example possesses unique spatial and urban characteristics that distinctly influence the pedestrian environment, these aspects vary in their impact on the pedestrian experience. A general lack of seating areas and the minimal integration of soft landscape elements were also noted. These concerns indicate an area for potential enhancement to support pedestrian use and environmental sustainability for the long term.

This study explored the relationship between urban planning and the pedestrian experience in Hail, Saudi Arabia. This study provides insights into the successes and obstacles encountered in creating a pedestrian-friendly streetscape. A key point of discussion is that while progress has been made in enhancing pedestrian access and walkability through urban projects, significant gaps must be addressed to achieve a fully pedestrian-centered urban design.

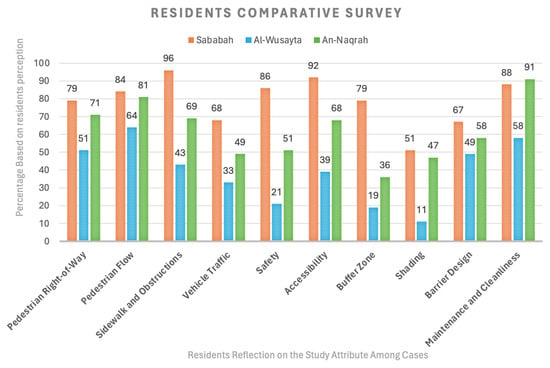

The comparison of the Sababah, Al-Wusayta, and An-Naqrah walking tracks highlights how locals perceive the strengths and weaknesses of each streetscape (Figure 13). The results indicate that the Sababah track is notable for its scenic views, while the Al-Wusayta path is appreciated for its accessibility and facilities. In contrast, feedback on the An-Naqrah track is mixed, with some residents mentioning its challenging terrain alongside the street and concerns about inadequate maintenance.

Figure 13.

Comparative community perception of this study’s attributes among this study’s cases.

To further validate these findings, statistical tests were performed to determine whether there was a statistically significant difference between walkability attributes and user satisfaction. A chi-square test was used to determine whether the perception of safety was a function of location, and a statistically significant association was found (p < 1.0). This indicates that the variations in the safety ratings across the different streetscapes are probably not due to chance. Furthermore, a multiple regression model was employed to determine the effect of various urban design factors (shading, sidewalk conditions, and vehicle proximity) on the overall walkability perception. The result showed that sidewalk continuity and buffer zone had the most significant positive effect.

The pedestrian movement in the Sababah streetscape stands out for its popularity in giving pedestrians the right of way and ensuring smooth pedestrian flow, indicating a well-designed infrastructure that values walkers. The An-Naqrah streetscape also performs well in this regard, though not as impressively as Sababah. The Al-Wusayta streetscape, despite its newer development, points to the need for a clearer separation between pedestrian and vehicle areas. For walkways and absence of blockages, Sababah excels, with the highest satisfaction rating for sidewalk conditions, signaling clear and obstruction-free paths for pedestrians. On the other hand, An-Naqrah has lower satisfaction levels, hinting at the user perception of some obstacles that could hinder pedestrian movement. In contrast, users of the Al-Wusayta streetscape face the most challenges, underscoring an urgent requirement for sidewalk design improvements.

Traffic management concerns vary among the three neighborhood walking tracks, with Al-Wusayta registering satisfaction. This could impact pedestrian safety and overall walking experience, highlighting the necessity for effective traffic control measures throughout all areas. Regarding security accessibility, users of the Al-Wusayta walking track express their perceptions of safety issues, potentially discouraging them from using the neighborhood track, especially during darker hours or when fewer people are present.

In contrast, the findings indicate that Sababah is the least congested and has the highest level of safety satisfaction among the three cases. Specifically, 86% of the survey participants expressed positive perceptions of the security of this area, compared to 51% in An-Naqrah and other areas. This may indicate that Sababah provides a relatively secure pedestrian environment; however, some concerns remain, including the absence of dedicated pedestrian crossings and physical barriers in certain locations. Therefore, it is possible to conclude that, despite the fact that Sababah is perceived as the most secure, there are still opportunities to improve the design to increase the level of pedestrian security.

In Sababah, accessibility is rated the highest, indicating that the track caters to a range of users, including those with disabilities. An-Naqrah’s lower rating suggests areas of that walking track where access could be improved. All locations have low scores regarding buffer zones and shading, with Al-Wusayta scoring the lowest. This indicates the need to separate pedestrian pathways and traffic to enhance safety and comfort. In Al-Wusayta, there is a lack of shading, emphasizing the need for additional measures to protect users against environmental elements. Regarding barrier design and maintenance, An-Naqrah leads in barrier design satisfaction, indicating that its barriers effectively contribute to safety and aesthetics. Sababah ranks highest in maintenance and cleanliness, showing its upkeep. However, there is room for improvement in both aspects of Al-Wusayta to enhance user satisfaction.

One significant finding is the need to integrate urban design initiatives and the fundamental principles driving walkability. Despite efforts to create pedestrian streetscapes, the analysis shows an attempt but a lack of actual integration with the surrounding urban environment. This disconnect not only separates pedestrian areas from essential commercial activities but also disrupts the natural flow of foot traffic, undermining the concept of walkability. The isolated nature of these streetscapes indicates an approach to city planning that treats pedestrian zones as separate entities rather than interconnected elements within the cityscape.

Additionally, inadequate provision of shade and seating areas, along with green spaces, adds to the challenge of establishing a pleasant and inviting environment for pedestrians. The extreme summer weather conditions in Hail make it crucial to have features that are more than for appearance; these important features should encourage people in larger numbers to walk greater distances by providing shade from the sun and spaces to relax and socialize. Not having these elements means missing out on making pedestrian areas more usable and attractive, especially when temperatures are high.

The debate brings up a challenge in how pedestrian paths are designed with safety and accessibility in mind. The instances observed show an issue of insufficient safety measures like clear crosswalks and pedestrian signals at intersections, putting pedestrians at risk of passing vehicles. Moreover, there is a lack of facilities for people with disabilities, such as tactile pathways, ramps, and proper barriers. This observation raises concerns about how inclusive the city’s design objectives and guidelines are, leaving many residents without adequate support.

To tackle these issues, this study proposes a shift toward a more comprehensive approach that focuses on pedestrians in urban planning. This method suggests blending pedestrian streets with the overall urban layout by prioritizing comfort, environmental sustainability, and different ways of traversing the city. This makes it easier for people to walk around smoothly and fosters a lively street atmosphere, which is crucial for the city’s social and economic well-being. Thus, a mixed-use development approach can improve walkability by creating vibrant urban spaces that blend living, working, and leisure areas. This approach can reduce the need for cars, encourage walking for tasks, and add vibrancy to city life. It follows trends emphasizing the value of proximity and easy access to make cities more pedestrian-friendly.

In summary, the discussion on improving street environments emphasizes the need for a sustainable urban planning approach in Hail. The research findings clarify that achieving walkability involves more than constructing sidewalks; it necessitates a fundamental change in city planning, prioritizing pedestrian comfort and safety, more tightly integrating walking infrastructure with the existing built environment, and driving higher environmental sustainability (Table 9). As Hail continues to grow, adopting these principles will be essential to transforming its landscape into a walkable and enjoyable environment for its residents.

Table 9.

Thematic Synthesis of Pedestrian Challenges in An-Naqrah, Sababah, and Al-Wusayta.

6. Findings and Implications

The statistical analysis conducted in this study provided a comprehensive assessment of walkability attributes across An-Naqrah, Sababah, and Al-Wusayta, offering valuable insights into the disparities in pedestrian experiences and urban design effectiveness. The chi-square tests revealed statistically significant differences in key pedestrian perceptions across the three neighborhoods. The safety perception variable exhibited a significant association with location (χ2(2, N = 673) = 8.91, p = 0.001, suggesting that residents in different neighborhoods experience safety conditions differently, likely due to variations in lighting, pedestrian infrastructure, and traffic separation measures. Similarly, shading adequacy differed significantly (χ2(2, N = 673) = 3.19, p = 0.005, highlighting the importance of shaded pedestrian pathways in promoting walkability in Hail’s extreme climate. The buffer zone effectiveness measure also showed a significant association (χ2(2, N = 673) = 7.16, p = 0.002, reinforcing the need for dedicated pedestrian protection from vehicular traffic across all case studies.

A One-way ANOVA also provided evidence of a significant overall statistical difference in walkability scores across the three neighborhoods (F(2, 670) = 0.99, p < 0.001. Tukey’s HSD tests as post hoc revealed that Sababah is a more walkable neighborhood than both Al-Wusayta and An-Naqrah. On the other hand, Al-Wusayta and An-Naqrah have problems with disjointed pedestrian networks, poor shading, and irregular right-of-way emphasis. Surprisingly, no statistically meaningful distinction was made between Al-Wusayta and An-Naqrah (p = 0.21), which implies that these two neighborhoods have comparable issues with regard to pedestrian infrastructure.

A multiple regression analysis was then performed to gain a further understanding of the relative impact of different urban design factors on walkability satisfaction. The model was significant (F(4, 668) = 26.98, p < 0.001, Adjusted R2 = 0.31; F(4, 668) = 26.98, p < 0.001), which means that 31% of the variance in walkability satisfaction can be attributed to the independent variables. These findings suggested that among the predictors, sidewalk continuity was the most important predictor of walkability satisfaction (β = 0.41, p < 0.001), which indicates that continuous and well-maintained sidewalks are important for improving pedestrian comfort. Shading adequacy was also found to be a critical factor (β = 0.29, p = 0.002), which is consistent with the previous literature that shows that providing shade along the pathways is crucial in increasing pedestrian movement in warm climates. A negative effect of vehicle proximity on walkability satisfaction was reported (β = −0.26, p = 0.005), which highlights the adverse impact of pedestrian–vehicle interactions on perceived safety and comfort. Furthermore, pedestrian right-of-way measures were also found to have a moderate positive effect (β = 0.21, p = 0.018), thus implying that urban areas that have well-defined pedestrian crossings and walkways increase the level of pedestrian confidence and usage.

These findings collectively support the relevance of integrated pedestrian infrastructure, shading provisions, and dedicated pedestrian zones in improving urban walkability. This study identifies specific recommendations for improvement in Al-Wusayta and An-Naqrah, including enhancing the density of shaded pathways, improving pedestrian right-of-way measures, and ensuring better sidewalk continuity. The results also match with the best international practices in walkability enhancement, which support the need for a systematic approach to urban design in Hail that emphasizes pedestrian-first policies, mixed-use development, and context-sensitive interventions to tackle climatic conditions.

As a result, this in-depth analysis and discussion about the City of Hail’s pedestrian streetscapes sheds light on the roles streets play in shaping urban areas and how they directly influence the success and quality of life in cities like Hail. This section examines the function of streets in urban development while highlighting their significant contributions to city prosperity and livability, as shown in Hail (Table 10).

Table 10.

Summary of this study’s key findings and urban planning implications.

The international examples can provide realistic ideas that may serve as a reference for enhancing pedestrian infrastructure in Hail. Barcelona’s superblocks focus on limiting automobile traffic, whereas Copenhagen exemplifies a long-term approach to pedestrianization. In addition, Melbourne’s urban cooling is directly relevant to Hail’s climatic constraints, and Paris’s universal design approach highlights accessibility as a key priority. By examining a range of factors, we consolidate insights on street connectivity challenges related to urban expansion, the need for adaptable street design, and approaches that can be employed to promote fair and sustainable urban development. Thus, by adapting these strategies to the socio-cultural and environmental conditions of the local area, Hail can create a more pedestrian-friendly urban environment consistent with Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030.

Based on the analysis of this study, this section suggests a roadmap for turning the mid-size City of Hail’s urban streets and other similar cities worldwide into spaces that enhance social, environmental, and economic well-being; a set of urban design principles needs to be revamped and considered:

- The Diverse Role of Streets in Public Life: Throughout history, streets have served as more than pathways for moving around; they play a crucial role in supporting economic endeavors, fostering social connections, and enriching the communal fabric. The shift from layouts in ancient cities to the intricate urban landscapes of today highlights the importance of recognizing streets as versatile public spaces. To embrace this versatility in Hail, it is essential to adopt a design approach that prioritizes pedestrian well-being, safety, and ease of access, creating public areas that promote economic vitality and social unity;

- Urban Sprawl and Connectivity Challenges: The widespread expansion of cities in the 20th century, characterized by urban sprawl and a heavy reliance on cars, has resulted in fragmented and low-density developments. This has posed challenges to maintaining connectivity between streets. In Hail, overcoming these obstacles includes improving street networks to link areas, encouraging various modes of transportation, and decreasing reliance on cars to address social exclusion and create more unified urban spaces;

- Adaptive Street Design for Contemporary Needs: The evolution of landscapes today calls for street configurations that can adapt to ongoing and upcoming environmental, societal, and economic issues. It underscores the importance of creating inclusive city areas catering to a wide range of individuals, including walkers, cyclists, and public transportation. Introducing layouts in Hail will enhance the well-being of its inhabitants, promote sustainable development, and bolster the city’s overall success;

- Equity and Social Inclusion Through Urban Design: The contrast in street connections between downtown districts and outlying regions mirrors and intensifies societal disparities. Addressing these gaps in Hail necessitates giving preference to enhancing zone infrastructure to guarantee fair access and promoting an inclusive urban growth strategy that caters to all community sectors;

- Policy Implications and Urban Governance for Street Development: To fully unlock the possibilities of the city’s streets, it is crucial to have well-designed urban policies and governance structures that align with the overall goals of urban development. Hail can greatly improve its development outcomes by identifying clear objectives, implementing more planning that supports its objectives, and involving the community in decision-making processes that cater to their needs and promote sustainable urban expansion;