Abstract

This study aimed to identify patterns of sustainability engagement based on circular economy (CE) strategy implementation, CE-oriented collaborative relationships, and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance, as well as to investigate whether these dimensions predict corporate reputation. Data were collected through a survey of 235 upper-level managers in the Brazilian agribusiness sector. A two-step analytical approach was applied, with cluster analysis identifying groups exhibiting distinct patterns regarding sustainability engagement (“Very Sustainable” and “Low-Sustainable”), followed by logistic regression, which singled out six key predictors among 28 variables, namely avoiding non-sustainable materials, repurposing by-products, fostering a shared CE vision, adhering to ethical guidelines, ensuring financial transparency, and fair labor practices. The final model achieved 83.4% accuracy, underscoring how an integrated approach to sustainability enhances corporate reputation. Considering its theoretical contributions, this study extends the NRBV and RV theories by demonstrating that CE strategies, CE-oriented collaborative relationships, and ESG performance strengthen pollution prevention initiatives, sustainable product development efforts, and trust among partners, among other achievements, thereby enhancing firms’ reputation and sustainable performance. Methodologically, the study integrates cluster analysis and predictive modeling to assess sustainability’s impact on reputation. From a managerial perspective, findings emphasize that corporate reputation benefits from circularity, governance integrity, and stakeholder engagement. However, the cross-sectional design, industry-specific sample, and reliance on self-reported data limit generalizability. Future research should adopt longitudinal and cross-industry approaches, examining regulatory shifts, technological advances, and evolving stakeholder demands in the sustainability–reputation nexus while incorporating external data sources to assess variations across institutional and cultural settings.

1. Introduction

The circular economy (CE) represents a transformative economic paradigm that seeks to replace the traditional ‘end-of-life’ concept by prioritizing the reduction, reuse, recycling, and recovery of materials throughout production, distribution, and consumption processes [1]. The concept positions circularity as a pathway to progressively decouple economic growth from natural resource depletion and environmental degradation [2,3].

As firms progress along the maturity spectrum of circularity, they must develop and implement structured sustainability strategies that extend beyond isolated initiatives, encompassing broader organizational, inter-organizational, and governance-based efforts. In this regard, three interrelated dimensions may be taken in accordance with corporate sustainability engagement: (i) CE strategies implementation focuses on resource efficiency, waste minimization, and closed-loop production models, strengthening a firm’s ability to reduce environmental impact and create circular value; (ii) CE-oriented collaborative relationships emphasize the role of stakeholder engagement in operationalizing sustainability, as partnerships among supply chain actors, regulatory agencies, and industry consortia facilitate knowledge sharing and resource alignment; and (iii) ESG performance serves as a governance framework, ensuring that sustainability initiatives are embedded in corporate decision-making, reinforcing transparency, ethical compliance, and long-term commitment to sustainability initiatives and practices.

CE strategy implementation refers to the adoption of circularity-driven practices that enhance resource efficiency, extend product lifecycles, and reduce environmental impact. Potting et al. [4] classify these strategies based on their degree of circularity. These strategies range from smarter product use and manufacturing to lifetime extension and material recovery [4]. Higher circularity levels, such as product sharing and reuse, generally lead to greater environmental benefits by keeping materials within the product chain for longer periods, thereby reducing the need for new resource extraction and minimizing waste. Prioritizing circular strategies that maximize material retention and minimize environmental impact remains key to achieving sustainable and regenerative systems in the supply chain [4].

Previous studies have found that collaboration is essential in the implementation of CE business models and in addressing environmental challenges [5,6,7]. The formation and nurturing of collaborative relationships between a wide array of stakeholders, such as industrial and service companies, consumers, public administration and regulatory bodies, and logistics service providers, amongst others, is an essential condition for circular economy achievements [8,9,10,11]. Effective collaboration across the supply chain is essential for fully implementing CE strategies. These strategies were defined and discussed in a seminal work by Potting et al. [4] who stated that “several circularity strategies exist to reduce the consumption of natural resources and materials, and minimize the production of waste. They can be ordered for priority according to their levels of circularity: Recover; Recycle; Repurpose; Remanufacture; Refurbish; Repair; Re-use; Reduce; Rethink; and Refuse” [4].

ESG metrics and performance may be of much value in ensuring that sustainability initiatives are institutionalized within corporate decision-making, reinforcing transparency, ethical responsibility, and regulatory compliance. Strong ESG performance has been associated with enhanced investor confidence, reputational resilience, and reduced exposure to sustainability-related risks, particularly in industries with high environmental impact, such as agribusiness supply chains. The integration of ESG metrics into corporate governance allows firms to demonstrate accountability while aligning their sustainability strategies with long-term value creation.

Corporate reputation has increasingly been linked to sustainability engagement. Firms known for their social and environmental responsibility, core components of a strong reputation, tend to garner higher trust from consumers and stakeholders, thus enhancing their competitive advantages [12,13]. This dynamic reinforces the importance of circular economy initiatives, as practices such as material reuse and recycling not only reduce environmental impacts but also foster positive perceptions of the firm, solidifying its reputation [14]. Furthermore, collaborative strategies within supply chains, such as the co-creation of sustainable solutions, have a direct impact on organizational credibility, increasing market acceptance [15].

This study is a quantitative and descriptive survey research aimed at evaluating the impact of CE strategy implementation, CE-oriented collaborative relationships, and ESG performance on firm reputation. Additionally, it seeks to identify the most relevant variables among the evaluated measurement items in explaining the response variable, corporate reputation, within our sample. The research focuses on the agribusiness sector in Brazil, one of the world’s largest producers and exporters of agricultural commodities. This context is particularly relevant given Brazil’s crucial role in ensuring food security, meeting the growing demand for sustainable agricultural practices, and positioning itself as a global leader in food production.

Agribusiness involves a wide range of activities, from farming and food processing to distribution and waste management, all of which demand substantial resources and generate significant waste. Although the sector has been extensively examined—covering areas such as supply chain management, sustainable agriculture, and environmental sustainability—it still faces cross-border challenges related to resource scarcity, effective waste management, and broader ecological concerns [16]. Accordingly, there is increasing interest in applying CE concepts in agribusiness; however, further investigation is required to better understand the factors influencing adoption and the firm-level practices that facilitate successful implementation [17,18,19]. Considering the arguments presented above, we formulate two research questions guiding our study:

- RQ1: How is the agri-food industry characterized in terms of the implementation of circular economy strategies, CE-oriented collaborative relationships, and ESG performance?

- RQ2: Considering circular economy strategies, CE-oriented collaborative relationships, ESG performance, and firm size, which specific factors are the strongest predictors of corporate reputation in agri-food firms?

Data were collected through an electronic survey administered to 235 upper-level professionals primarily associated with the agricultural and agribusiness sectors. Most respondents held executive positions, reflecting a leadership-oriented sample, including CEOs, General Directors, and Superintendents, as well as Operations, Logistics, and Supply Chain Directors/Managers, and Sales Directors/Managers. To answer the two research questions, we employed cluster analysis to segment firms based on their implementation of circular economy strategies, CE-oriented collaborative relationships, and ESG performance (RQ1). Subsequently, logistic regression was applied to identify which specific items within these three dimensions, together with firm size, most effectively predicted corporate reputation (RQ2).

This study draws on the Relational View (RV) and the Natural-Resources-Based View (NRBV) as complementary theoretical lenses. The RV posits that inter-organizational interactions constitute one of the most critical resources for firms, enabling them to enhance performance and secure competitive advantages [20,21]. By emphasizing collaboration and alliance formation, the RV aligns with circular economy perspectives that demand coordinated efforts throughout supply chains. Meanwhile, the NRBV highlights how effective engagement with the natural environment can serve as a unique source of competitive advantage [22]. This view broadens the RV by underscoring the ecological dimension within which inter-firm collaborations unfold. Together, these theories suggest that strong sustainability engagement—encompassing both collaborative capacity and responsible resource management—can bolster firms’ reputations.

By bridging these theoretical perspectives, the present study addresses five key gaps, which are summarized as follows. First, there is a need for integrated assessments that simultaneously examine circular economy (CE) strategies, collaborative stakeholder relationships, and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance rather than treating them as isolated constructs. Second, despite corporate reputation being a critical intangible asset closely linked to market performance and stakeholder trust, studies rarely isolate how specific sustainability dimensions directly influence reputation. Third, there have been calls for more research identifying key predictors of corporate reputation; thus, our study provides a quantifiable framework to assess the sustainability factors most directly affecting reputation. Fourth, methodological challenges remain in effectively segmenting firms according to their sustainability engagement levels and subsequently identifying the specific practices that shape reputation. Lastly, despite its substantial potential for circularity and notable environmental footprint, the agro-industrial sector remains largely understudied regarding empirical research on CE strategies and ESG-driven reputational outcomes.

By addressing these gaps, this study provides a structured, data-driven perspective on CE strategies and CE-oriented collaborative relationships. The findings offer insights that may support both academic discussions and practical applications in sustainability strategies.

This article is organized into the following sections. Section 2 presents the literature review, examining the Natural-Resource-Based View (NRBV) and the Relational View (RV) in the sustainability research field, along with circular economy (CE) strategies, CE-oriented collaborative relationships, ESG performance, and their impacts on corporate reputation. Section 3 outlines the research model and methodology, while Section 4 summarizes the main results. In Section 5, we discuss the findings and their theoretical and managerial implications. Finally, Section 6 provides the study’s key limitations and offers suggestions for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The NRBV and RV Theories and the Sustainability Research Area

The NRBV theory posits that firms will obtain competitive advantages when they are able to engage with the natural environment [19]. Under this theory, firms need to focus on efficiently using their resources and developing sustainable solutions to the challenging problems the world currently faces [20]. The theory is structured into three main components: pollution prevention, product stewardship, and sustainable development, which has recently been decomposed into cleaner technologies and social concerns (base of the pyramid) [21,22]. From the perspective of NRBV, the implementation of CE strategies and ESG practices can be considered strategic capabilities that support companies in improving their pollution prevention systems throughout the life cycle of their products. By optimizing the use of resources and operational efficiency, companies improve their financial and environmental performance.

When a firm does not possess the resources and capabilities it needs to develop competitive advantages, it needs to complement its own resources with the resources from other partners [22,23]. Hence, the ability to develop collaborative relationships with partners is a distinguishable asset that companies must pursue. A clear engagement with sustainable initiatives can then be supported by a company’s own resources and capabilities but can be complemented through collaboration with other companies. In this context, the RV theory arises. It states that firms can have access to critical resources through inter-organizational interactions [24] in order to increase their performance. In this context, these relation-specific assets are critical sources of competitive advantages [25]. Together, the RV and the NRBV theories consider that a company’s engagement with the natural environment and society, supported by collaborative relationships, can improve firms’ sustainable performance. Thus, the dimensions of the NRBV theory are complemented by an ESG perspective to present an inclusive approach to promoting sustainability within the circular economy paradigm [26].

Previous research on circular economy and ESG practices has extended the NRBV and RV theories. Aryee and Kanda analyzed the effects of circular economy practices on firm performance [27]. Pan et al. [28] corroborate this view by reporting that CE practices based on eliminating waste and pollution positively affect firms’ sustainable performance. Magnano et al. [29] found that organizational capabilities and stakeholder pressure influence the relationship between circular economy and firm performance. Yin et al. [30] confirmed the benefits CE practices have to firms’ commercial and ecological sustainability but also emphasized that these effects can be higher depending on the industry type and country where the company is located. This finding emphasizes the need for more studies on CE strategies in the agri-food industry of emerging markets.

There has been research whose findings can be analyzed under the lens of the RV theory. Marty and Ruel [31] revealed that collaboration among supply chain partners enhances firms’ performance, and promotes sustainability, innovation, and trust. Sudusinghe and Seuring [32] found that information, risk and responsibility sharing, incentives, and joint product design are collaborative practices required for a successful CE implementation. Previous studies have also confirmed that these collaboration practices improve firms’ sustainable performance [33,34,35].

2.2. CE Strategies and CE-Oriented Collaborative Relationships

The circular economy (CE) is a concept encompassing multiple levels of analysis—micro (products, companies, consumers), meso (eco-industrial parks), and macro (cities, regions, nations) [1]. It seeks to harmonize environmental quality, economic prosperity, and social equity in line with sustainable development principles, benefiting both current and future generations. By emphasizing restorative and regenerative systems, CE aims to keep products, components, and materials at their highest utility and value, thereby contributing to sustainable development [1].

As noted by Bag et al. [36], the transformative potential of the circular economy may evolve due to institutional pressures—such as coercive, normative, and mimetic forces—that shape organizational adoption of CE practices. Additionally, consumer behavior significantly influences the transition to CE, as it demands shifts toward purchasing functionality over ownership [3].

CE strategies foster cleaner production, optimize resource use, and minimize waste, generating value in technical and biological cycles. To support these outcomes, systemic thinking, eco-design (e.g., design for recycling (DfR), design for environment (DfE), design for disassembly (DfD), and design for remanufacturing or reuse (DfR)), among other initiatives, play a pivotal role in reducing environmental impacts and enhancing resource efficiency across industries [37].

Dynamic capabilities are critical for the successful adoption of the circular economy model because they facilitate the integration and reconfiguration of resources to meet shifting environmental and market demands [38]. Developing CE business models requires a dual focus on product- and process-oriented practices, both underpinned by dynamic capabilities. Product-focused practices involve designing goods that are biodegradable, reusable, or recyclable, ensuring alignment with CE principles and extending materials’ lifecycles. Meanwhile, process-focused practices prioritize establishing closed-loop production and consumption systems, necessitating stakeholder collaboration to manage resource flows effectively and reduce waste [5].

In the context of agribusiness, integrating product- and process-oriented practices can lead to transformative innovations that align with circular economy principles. For instance, product-focused innovations might involve designing biodegradable agricultural inputs, such as compostable packaging or reusable containers for seed and fertilizer distribution. Concurrently, process-oriented innovations could emphasize closed-loop systems, such as nutrient recovery from organic waste or water recycling in irrigation. By bridging these two dimensions, agribusinesses can establish sustainable value chains that enhance resource efficiency, reduce environmental impacts, and contribute to the broader objectives of regenerative agriculture.

Agribusiness, due to its resource-intensive nature, plays a central role in implementing CE strategies. The sector is directly linked to the production of food and other essential goods, amplifying its relevance in the context of global food security and sustainability. Transitioning to a circular model in this sector involves an integrated approach to reducing waste, optimizing resource use, and implementing regenerative practices that promote economic, environmental, and social sustainability [7].

Practices such as nutrient recovery from organic waste, packaging reuse, and efficient water and energy use are central elements of CE in agribusiness. Beyond reducing environmental impacts, these practices create opportunities for economic value through product diversification and innovation. For instance, environmental innovation—encompassing eco-friendly products and processes—positively affects reputation by signaling a firm’s commitment to sustainability [14].

In Brazil, the agribusiness sector plays a crucial role in adopting sustainable practices, given the country’s position as one of the largest exporters of agricultural commodities. Brazilian firms have the opportunity to lead the global transition to a circular economy, particularly by leveraging their capacity for innovation and their presence in international markets, meeting the growing demand for sustainable products.

The importance of collaborative relationships in various performance dimensions of firms and supply networks has long been recognized in the academic literature, with seminal contributions exploring the density and dynamics of these relationships [24,39,40]. Observing the current shift from linear to circular supply chain models, it becomes clear that research focusing on the role of collaboration in driving performance will remain a central theme in this transition.

Developing and implementing products and processes aligned with circular supply chain principles pose significant challenges. In this context, collaboration among stakeholders is crucial for both product-oriented and process-oriented practices. Product-focused efforts include designing biodegradable, reusable, or recyclable goods to ensure compliance with CE principles. Meanwhile, process-focused practices involve establishing closed-loop production and consumption systems, inherently requiring collaboration among various organizations and stakeholders [5].

In circular-oriented innovations, collaboration is pivotal for tackling systemic sustainability challenges. Early, meaningful stakeholder partnerships are essential for integrating knowledge across value networks, enabling experimentation, and scaling circular economy solutions [41,42]. However, effective collaboration hinges on a shared vision, mutual enthusiasm, and credibility—critical factors for navigating the complexities inherent in circular innovation. Key motivators for such partnerships include competitive advantages, market expansion, and innovation capacity, complemented by goals like ecological responsibility and the broader pursuit of sustainability. Nevertheless, significant barriers remain, such as trust deficits, cultural differences, and misaligned incentives, which can undermine CE integration [41,43].

Collaboration is critical for the implementation of circular economy-oriented innovations. This context requires new configurations within value networks to address the dispersion of necessary resources, knowledge, and infrastructure among diverse actors [41,44]. Undoubtedly, this is a systemic innovation, which demands a more radical and collaborative approach, requiring both internal and external competencies to overcome the knowledge–implementation gap in circular economy strategies. For instance, systemic innovations are characterized by longer implementation timelines and the need for explorative knowledge, in contrast to incremental innovations that involve fewer complementary innovations and rely on trusted partners.

To manage the complexity of these systemic efforts, portfolio approaches and open innovation frameworks are crucial [45]. These approaches balance the degrees of openness in collaborative projects and evolve agreements to scale participation and align business models across stakeholders, further solidifying the foundation for effective circular economy transitions [41].

2.3. Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Performance

Early contributions to the ESG–financial performance debate, grounded in neoclassical theory, argued that environmental or social responsibility activities exceeding legal requirements would incur extra costs and thus reduce firm value [46]. This perspective initially posited a uniformly negative link between ESG initiatives and financial outcomes. However, more recent studies have demonstrated that socially responsible behavior can positively impact both performance and firm value [46]. In parallel, the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment popularized the ESG concept, advising investors to include ESG scores in their decisions. As a result, management consulting firms and investors broadly employ ESG metrics as a core indicator of corporate responsibility, combining environmental performance (e.g., resource efficiency, emission control), social performance (e.g., human rights, product responsibility), and governance standards (e.g., board structure, shareholder rights) into an integrated assessment [47].

Over time, the stakeholder perspective has reinforced the view that ESG management may positively affect firm value by strengthening trust and commitment among both internal and external stakeholders [48]. Companies that diligently integrate ESG principles tend to reduce conflicts with employees, customers, and communities, thereby lowering the likelihood of failure or default [49]. This approach aligns with the ESG disclosure rationale, which holds that proactive disclosure of ESG-related information can enhance social recognition and capital, ultimately boosting enterprise value [49]. High ESG performance often leads to governmental and public approval, fostering consumer confidence and attracting investors. Consequently, firms excelling in ESG dimensions commonly achieve robust profitability, effective risk management, and higher valuation levels [50]. Thus, adopting CE strategies emerges as a natural extension of ESG commitments, particularly for companies pursuing sustainable development and stakeholder alignment.

The implementation of CE strategies has yielded significant benefits for organizational performance [51]. When grounded in ESG principles, sustainable CE models can further boost overall ESG performance [52]. Moreover, CE initiatives positively influence companies’ financial outcomes, supported by governance mechanisms such as board composition, risk management, and internal audits, which strengthen the connection between CE and corporate performance [53]. In parallel, global challenges like resource depletion and escalating environmental disasters have prompted nations to adopt targeted measures—such as the Sustainable Development Goals and climate action plans—underlining CE’s role in curbing harmful practices and reinforcing ESG indicators [52]. By emphasizing regenerative production and responsible consumption, CE strategies closely align with ESG objectives, particularly by reducing environmental footprints and cultivating long-term profitability.

Notwithstanding the increasingly positive consensus on ESG’s value-enhancing potential, certain studies grounded in neoclassical assumptions suggest that additional expenses linked to ESG investments may not be sufficiently offset by their benefits, leading to inconsistencies in the empirical findings on ESG’s direct impact on firm performance [48]. Even so, the prevailing viewpoint holds that ESG-aligned firms are more likely to gain investor confidence, competitive advantages, and operational efficiency [50]. As ESG disclosures become more standardized through national stock exchange mandates and evolving global regulations, the ESG–performance relationship may become clearer, offering further insights into best practices for businesses aiming at sustainable and profitable growth [48].

2.4. Corporate Reputation

Corporate reputation is a critical intangible asset that shapes how stakeholders perceive a firm’s commitment to sustainable practices. According to Carter et al. [13], a strong sustainability reputation significantly influences consumer behavior, particularly when firms demonstrate clear environmental and social responsibility. Such reputation fosters consumer trust and purchase intentions, especially in competitive markets offering products with comparable sustainability credentials. Moreover, reputation enhances a firm’s capacity to leverage ESG initiatives effectively, bolstering customer loyalty and satisfaction while strengthening its market-leading position [13,54].

Firms that adopt proactive environmental strategies, such as cleaner production and eco-innovation, often experience substantial reputation benefits as these actions align with stakeholder expectations of corporate responsibility [14]. Similarly, transparency in environmental disclosures plays a pivotal role in constructing a positive reputation. As Castro [12] highlights, symbolic environmental actions can harm corporate reputation, whereas substantive efforts improve it, emphasizing the importance of credibility and consistency in corporate behavior. Barbosa and Pumpín [55] corroborate this line of thought by reporting that agri-food firms’ reputation is enhanced by water footprint management initiatives.

Reputation also intersects with collaborative efforts and CE strategies. By facilitating the operationalization of CE principles, supply chain collaborations simultaneously bolster a firm’s reputational standing. Early, meaningful partnerships focused on innovation and shared value creation positively shape stakeholder perceptions, cultivating trust and long-term engagement [15,56]. Additionally, CE strategies such as reuse, recycling, and remanufacturing help build a green corporate image, a vital element in establishing legitimacy and trust among stakeholders [57].

The role of reputation extends to mitigating risks associated with sustainability initiatives. Negative events, such as scandals related to unsustainable practices, can severely damage a firm’s reputation, reducing consumer trust and eroding financial performance [54]. Conversely, firms with robust reputations are better positioned to recover from such events, leveraging their established credibility to rebuild stakeholder confidence. Reputation acts as both a safeguard and a strategic driver, enabling firms to navigate the complexities of sustainability while achieving competitive advantages.

In summary, sustainability engagement may play a fundamental role in shaping corporate reputation, as firms that actively commit to environmental responsibility, transparent communication, and stakeholder collaboration tend to strengthen their public image and credibility. By integrating substantive sustainability initiatives, companies may enhance stakeholder trust, reinforce legitimacy, and establish a positive market perception. Over time, this sustained engagement with sustainability principles can mitigate reputational risks and position firms as industry leaders, fostering long-term competitiveness and financial resilience in an increasingly sustainability-driven business environment [12,13,14].

3. Materials and Methods

This section details the methodological approach adopted in this study. First, we describe the sample characteristics and data collection process. Then, we outline the measurement items used in both clustering and regression analysis. Finally, we present the data analysis techniques applied, including cluster analysis for firm segmentation and logistic regression for assessing the impact of sustainability engagement dimensions on corporate reputation.

3.1. Sample

The sample for this study was drawn from a population of agribusiness companies participating in the Global Agribusiness Academy program conducted by Fundação Dom Cabral (FDC), ranked among the top 10 business schools worldwide by the Financial Times in 2024 (https://www.fdc.org.br/en/ranking-and-accreditations, accessed on 23 March 2025). The database includes managers, coordinators, supervisors, directors, board members, CEOs, and presidents from various sectors, such as agriculture, livestock, agri-food machinery and equipment manufacturing, and food production across Brazil. In total, the population comprised 4287 respondents.

Participants were invited to take part in the study via email, and follow-up emails were sent to those who did not respond initially. After four attempts, we obtained 235 responses, which represent approximately 5.48% of the eligible population. The margin of error was calculated using a 95% confidence level and an expected proportion of 0.5, resulting in an estimated margin of error of 6.39%.

The majority of the sample was composed of Operations, Logistics, and Supply Chain Directors/Managers (38.3%), followed by CEOs, General Directors, and Superintendents (36.6%). Additionally, Commercial and Sales Directors/Managers represented 10.6% of respondents, while Financial Directors/Managers accounted for 6.0%. Other positions, such as Sustainability Directors, Administrative Advisors, Environmental Coordinators, and IT Managers, accounted for smaller percentages.

Most respondents had significant tenure in their companies, with 62.55% having worked for more than five years, while 20.00% had between three and five years of experience. A smaller portion had been in the company for one to three years (14.89%), and only 2.55% had joined within the last year. Regarding company size, the majority (58.97%) worked in organizations with 101 to 400 employees, followed by 34.62% in companies with more than 400 employees. A smaller share (6.41%) was employed in businesses with up to 100 employees. This profile suggests that the sample primarily consists of experienced professionals from medium to large enterprises.

Respondents were engaged in various activities and sectors within the agribusiness industry. The largest segment (39.90%) worked in crop production, followed by 28.35% in animal production and related industries. Additionally, 20.21% were involved in support activities and services, while 11.55% focused on fruit production. This distribution reflects a diverse sample, with a strong presence in both plant- and animal-based agribusiness.

3.2. Measurement Items

This study compiled a list of 37 measurement items. Of these, 27 items were employed in the first phase of the analysis, which involved cluster analysis to segment firms according to their sustainability engagement across three key dimensions: CE strategies (10 items), CE-oriented collaborative relationships (6 items), and ESG performance (11 items). In the second phase, logistic regression was conducted using these 27 sustainability-related items, along with an additional 6 items related specifically to corporate reputation as the response variable. The remaining four measurement items—company size, industry sector, position held, and length of employment—were used solely to characterize the respondents and their respective companies.

Table 1 presents the definitions of the constructs assessed in this study.

Table 1.

Latent variables definition.

All model measurements were assessed using a 4-point Likert scale, with response options: 1 (Strongly Disagree), 2 (Partially Disagree), 3 (Partially Agree), and 4 (Strongly Agree). A complete description of all the measurement items in the research model can be found in Appendix A.

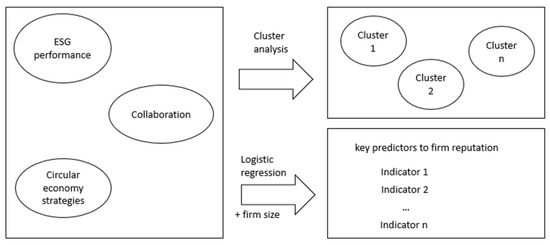

3.3. Data Analysis Techniques

This study employed cluster analysis and logistic regression to achieve its core objectives. Cluster analysis is a data analysis technique that organizes data into groups based on their similarities [64] to facilitate decision-making [65] that has been used in several studies aimed at carrying out the segmentation of a set of items (firms, customers, others) [66,67,68,69]. The logistic regression technique estimates the relationship between one dependent variable and one or more independent (predictor) variables [70,71]. This technique provides a powerful interpretation of datasets and has been applied in previous studies to describe phenomena in several areas [72,73,74,75].

The first step involved segmenting firms based on 27 measurement items related to CE strategies adoption, CE-oriented collaborative relationships, and ESG performance. In the second step, logistic regression was applied with corporate reputation as the response variable.

This two-step empirical approach distinguishes the study by allowing a more structured examination of how sustainability dimensions influence corporate reputation. It first provides a nuanced understanding of variations in firms’ CE strategies implementation, collaborative stakeholder engagement, and ESG performance before evaluating their collective impact on reputation.

Cluster analysis was employed as an unsupervised learning technique. The analysis utilized the NbClust package in R (version 4.3.1), which provided a comprehensive set of 30 indices (e.g., the Elbow Method, Silhouette Width, and Gap Statistics) to determine the optimal number of clusters. The differences between the identified clusters were tested statistically using Cramér’s V [76]. Cramér’s V, derived from the Chi-Square test, measures the strength of association between two categorical variables, ranging from 0 (no association) to 1 (strong association). Unlike ANOVA, which analyzes differences in means for continuous variables, Cramér’s V is particularly suited for categorical data, making it ideal for this study. Here, it was used to verify the robustness of the cluster segmentation by assessing the strength of associations between firm groupings and their differences in the implementation of CE strategies, collaborative relationships, and ESG performance.

In the second stage, logistic regression was employed to identify the measurement items that most significantly influence corporate reputation. Given the complexity of the analysis involving 28 potential predictors (the 27 items previously used in the cluster analysis plus the additional variable—company size), a preliminary variable selection was conducted using two machine learning algorithms: Boruta and Lasso. Logistic regression was then applied to these selected variables due to its interpretability, and further refinement of the model was performed using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC).

To validate the model, we employed a 70/30 cross-validation approach, where the data were split into two sets: 70% for training and 30% for testing. The training dataset was used to fit the model, while the testing dataset was reserved for performance evaluation. This method ensured that the model was evaluated on unseen data, providing a robust measure of its generalization ability. We assessed performance using several metrics. The model’s accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity were measured using a confusion matrix. We also examined deviance residuals to identify outliers and used the Generalized Variance Inflation Factor (GVIF) to assess multicollinearity. Additionally, the model’s discriminative ability was confirmed through Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis and the Area Under the Curve (AUC).

Figure 1 presents a summary of this study’s research model and methodology. The research model is composed of the constructs of ESG performance, circular-oriented collaboration, and circular economy strategies. The cluster method is applied in this set of data to determine the existing clusters. The logistic regression uses the data of the research model and the firm’s size to determine the set of indicators that better explain the firm’s reputation.

Figure 1.

Research model and methodology.

4. Results

4.1. The Clustering Process

NbClust delivers a data-driven recommendation by evaluating multiple combinations of cluster numbers, distance measures, and clustering methods, ensuring the reliable segmentation of firms into the optimal clustering scheme [77].

Among the indices evaluated, 10 supported two clusters as the optimal solution, while another 10 suggested three clusters. A smaller number of indices pointed to six, seven, or eight clusters as alternative solutions. The D index, a graphical method that detects the optimal number of clusters by identifying an inflection point (“knee”) in the second differences plot, confirmed that the two clusters provided the most distinct segmentation, reinforcing the selection of this solution.

Based on these results, the sample was segmented into two clusters: “Very Sustainable” firms, characterized by a strong commitment to sustainability, and “Low-Sustainable” firms, with lower engagement levels. Firms in the “Very Sustainable” cluster exhibited a more significant effort in implementing circular economy (CE) strategies, actively restructuring their supply chain relationships to enhance collaboration and adaptability. Their engagement in these redesigned networks facilitated stronger partnerships and resource-sharing mechanisms, reinforcing the transition towards circular business models. Additionally, these firms demonstrated superior performance across key ESG metrics, such as environmental impact reduction, ethical governance practices, and social responsibility initiatives. Together, these dimensions reflect a comprehensive sustainability corporate engagement, where firms not only adopt circular practices but also integrate them into broader strategic and relational frameworks, amplifying their long-term sustainability impact.

4.1.1. Clustering and Circular Economy Strategies

Table 2 presents the percentage distribution of responses from the two clusters—Very Sustainable and Low-Sustainable—regarding circular economy strategies. The results highlight distinct patterns in sustainability-oriented actions, illustrating how firms integrate circular economy principles into their operations.

Table 2.

Circular economy strategies: participants responses per cluster (%).

The results reveal a clear gap between the two clusters in their adoption of circular economy strategies. Firms in the Very Sustainable cluster consistently reported greater adherence to CE practices than those in the Low-Sustainable cluster. A particularly notable difference emerged in equipment repair and restoration (Cramér’s V: 0.72 and 0.69, respectively), where Very Sustainable firms showed a significantly stronger commitment to extending product lifespan before replacement. Similar disparities were found in waste minimization efforts (Cramér’s V: 0.68) and avoidance of non-sustainable materials (Cramér’s V: 0.63), reinforcing the segmentation between the two groups.

Additionally, firms in the Very Sustainable cluster demonstrated a more proactive stance on repurposing materials and using recycled inputs (Cramér’s V: 0.58 and 0.53, respectively), whereas Low-Sustainable firms showed significantly lower engagement in these practices. These findings confirm that companies with a stronger commitment to sustainability consistently implement more advanced circular economy strategies, validating the clustering approach.

4.1.2. Clustering and Circular Economy-Oriented Collaborative Relationships

Table 3 presents the distribution of responses for the CE-oriented collaborative relationships construct, comparing the Very Sustainable and Low-Sustainable clusters. The analysis highlights key differences in how these firms engage in collaborative activities, including knowledge sharing, joint decision-making, and formal contractual agreements. These findings offer deeper insights into the role of collaboration in enabling circular economy adoption and strengthening the alignment among supply chain partners.

Table 3.

CE-oriented collaborative relationships. Participants responses per cluster (%).

The results indicate significant differences between the two clusters in their approach to CE-oriented collaborative relationships. Firms in the Very Sustainable cluster reported a stronger commitment to knowledge sharing, governance structures, and joint decision-making, reinforcing their alignment with circular economy principles.

One of the most pronounced gaps emerged in the shared understanding of circular economy concepts (Cramér’s V: 0.72), where a majority of Low-Sustainable firms disagreed with having a common purpose, while Very Sustainable firms largely agreed. Similarly, data-sharing practices were notably stronger in the Very Sustainable cluster (Cramér’s V: 0.57), with none of the Low-Sustainable firms fully endorsing this practice.

Joint planning and contractual agreements also exhibited clear contrasts (Cramér’s V: 0.55 and 0.49, respectively), with Very Sustainable firms showing greater integration of circular economy principles into their partnerships. The presence of shared governance structures further distinguished the clusters (Cramér’s V: 0.55), as Very Sustainable firms were significantly more likely to value these mechanisms.

Finally, collaborative relationships for material innovation had one of the strongest associations with sustainability perception (Cramér’s V: 0.72). While most Low-Sustainable firms expressed disagreement, the vast majority of Very Sustainable firms acknowledged the importance of these partnerships.

Considering these findings as a whole, it may be suggested that firms with a stronger commitment to sustainability are also more actively engaged in collaborative efforts that facilitate circular economy implementation.

4.1.3. Clustering and Environment, Social, and Governance Performance

Table 4 presents the distribution of responses for ESG performance, comparing the Very Sustainable and Low-Sustainable clusters. The analysis highlights key differences in corporate sustainability initiatives, illustrating how firms integrate environmental, social, and governance practices into their operations and align them with circular economy principles.

Table 4.

ESG performance. Participants’ responses per cluster (%).

The results reveal consistent differences between the two clusters in ESG performance, reinforcing the segmentation based on sustainability engagement. The most pronounced disparities appeared in carbon emissions reduction (Cramér’s V: 0.71) and the prioritization of sustainable materials (Cramér’s V: 0.78), where Very Sustainable firms demonstrated a significantly stronger commitment than Low-Sustainable firms. Similarly, waste management optimization (Cramér’s V: 0.76) and the establishment of environmental targets (Cramér’s V: 0.62) further differentiated the two clusters.

On the social dimension, firms in the Very Sustainable cluster were more engaged in community development initiatives (Cramér’s V: 0.63) and employee well-being and safety (Cramér’s V: 0.60), with a gap in their commitment to fair labor practices and anti-discrimination policies (Cramér’s V: 0.52).

Regarding governance practices, the strongest contrasts emerged in stakeholder engagement (Cramér’s V: 0.52), ethical guidelines adherence (Cramér’s V: 0.51), and financial transparency (Cramér’s V: 0.62). In each case, Very Sustainable firms exhibited stronger alignment with responsible business practices, while Low-Sustainable firms showed weaker adherence.

Overall, the findings highlight the strong relationship between sustainability commitment and superior ESG performance, reinforcing the role of responsible corporate practices in circular economy adoption

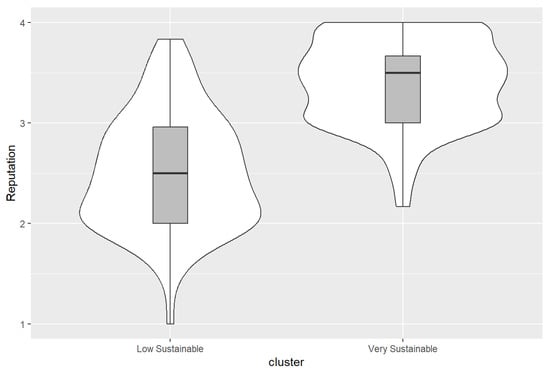

4.2. Corporate Reputation in “Low-Sustainable” and “Very Sustainable” Clusters

The results indicate a significant difference in reputation scores between the two identified clusters (Figure 2). The “Very Sustainable” cluster obtained a higher mean reputation score (M = 3.40, SD = 0.429), suggesting that firms in this group are perceived as reputable and consistent in maintaining trust and quality standards. The relatively low standard deviation indicates that reputation perceptions are stable among companies in this cluster. The one-sample t-test further supports these findings, revealing a significant mean difference (t = 97.992, p < 0.001) from zero, with a 95% confidence interval between 3.33 and 3.47.

Figure 2.

Values of reputation score by cluster.

Conversely, the “Low-Sustainable” cluster reported a substantially lower mean reputation score (M = 2.51, SD = 0.568), indicating a weaker perceived reputation. The higher standard deviation suggests greater variability in stakeholder perceptions within this group, potentially reflecting inconsistencies in trustworthiness, product quality, or social responsibility efforts. The observed gap between the two clusters highlights the critical role of corporate reputation in differentiating sustainable companies from those struggling with market perception.

4.3. Logistic Regression Model

Given the complexity of running a logistic regression model with 28 independent variables—27 measurement items related to circular economy strategies, CE-oriented collaborative relationships, and ESG performance, plus one measurement item for firm size—a structured approach was employed to construct the model. It is crucial to reduce the number of independent variables in a dataset with 235 respondents and 28 predictors to prevent overfitting, improve model interpretability, reduce multicollinearity, and enhance computational efficiency. A complex model with too many variables may capture noise instead of true patterns, which can lead to poor generalizability. Moreover, having fewer variables makes the model easier to understand and more reliable by mitigating issues such as multicollinearity, where predictors are highly correlated, leading to distorted results. In addition, a simpler model is computationally less demanding and tends to perform better on new data.

The process begins with data preparation, in which random seeds are used to execute routines multiple times. For each iteration, the data were divided into training and testing sets. Variable selection was performed using the Boruta algorithm on the training data, followed by Lasso for secondary selection. Model fitting involved iteratively refining the logistic regression model based on the AIC, and various statistics such as Nagelkerke R-squared were calculated. The model was evaluated using predictions from the test data, and performance metrics such as accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity were calculated using a confusion matrix.

In the logistic regression analysis, the response variable was the rounded average reputation score, which was converted into integer values (1, 2, 3, or 4). Two classes of reputation were defined: “Low to Medium” (values 1, 2, or 3) and “High” (value 4). This measure was based on respondents’ assessments of the company using a scale from 1 (Totally disagree) to 4 (Totally agree) across statements related to reputation, including reliability, product quality, legal compliance, employee integrity, and social responsibility.

4.3.1. Descriptive Statistics of the Logistic Regression Model

Analysis of the 500 logistic regression models created using the proposed method yielded an accuracy of 0.7857 (95% CI 0.6713–0.8748), with sensitivity and specificity values of 0.6800 and 0.8444, respectively. Adjusting the cut-off point resulted in a slightly higher accuracy of 0.8143 (95% CI 0.703–0.8972), with sensitivity and specificity values of 0.8000 and 0.8222, respectively. The improvement in accuracy was evaluated for statistical significance, and the observed increase was statistically significant, reinforcing the model’s validity.

The final logistic regression model included as significant predictors the measurement items CIR1, CIR8, COL1, ESGG1, ESGG2, and ESGS3. The results, detailed in Table 5, demonstrate the robustness of the method across different iterations.

Table 5.

Data robustness.

As shown in Table 5, the logistic regression analysis identified six key predictors of corporate reputation, underscoring the strategic influence of circular economy (CE) practices, collaborative relationships, and ESG performance. Specifically, avoiding non-sustainable materials (CIR1) and repurposing materials or by-products (CIR8) emerged as critical CE-related predictors, reinforcing the role of resource efficiency in enhancing corporate reputation. Likewise, establishing a shared vision for CE with supply chain partners (COL1) was a strong predictor, indicating that stakeholder alignment on sustainability goals enhances corporate credibility. From an ESG perspective, ethical compliance (ESGG1) and financial transparency (ESGG2) were positively linked to reputation, highlighting governance’s role in building stakeholder trust. Finally, commitment to fair labor practices and non-discrimination (ESGS3) was another key determinant, reinforcing the significance of social responsibility in shaping corporate image.

4.3.2. Model Validation and Performance

The model validation process revealed no significant outliers or multicollinearity issues, as indicated by the GVIF values. The confusion matrix demonstrated an accuracy of 0.8213 (95% CI 0.7662–0.8681), with sensitivity and specificity values of 0.7619 and 0.8543, respectively. Adjusting the cut-off point resulted in a slightly higher accuracy of 0.834 (95% CI 0.7802–0.8792), with sensitivity and specificity values of 0.8095 and 0.8477, respectively. Nagelkerke’s R-squared was 0.491, indicating a moderate explanatory power of the model for the observed variance in the dependent variable.

Finally, the ROC curve analysis confirmed the model’s strong discriminative power, illustrating the trade-off between sensitivity and specificity across different classification thresholds. The AUC (Area Under the Curve) value of 0.9083 indicates a high level of accuracy, demonstrating the model’s ability to effectively distinguish between firms based on corporate reputation. To refine the classification, the optimal decision threshold was identified at 0.4320 balancing sensitivity and specificity. This threshold ensures that the model maximizes correct classifications while minimizing false positives and false negatives. These results reinforce the robustness of the model and its applicability in assessing corporate reputation based on sustainability engagement.

5. Discussion

The results obtained through cluster analysis and logistic regression provide significant insights into the relationship between CE strategies, CE-oriented collaborative relationships, ESG performance, and corporate reputation. The cluster analysis revealed distinct groups of firms (“Low-Sustainable” and “Very Sustainable”) based on the intensity of their sustainability engagement, demonstrating that companies with a strong implementation of CE strategies, CE-oriented collaborative relationships designed to promote circular economy principles and support strategy implementation, and a high ESG performance consistently reported higher reputational scores.

When comparing the two clusters, a notable difference in the implementation of CE strategies was observed. Firms in the “Very Sustainable” cluster demonstrated a significantly stronger commitment to reducing natural resource consumption, extending product life cycles, and minimizing waste. This finding aligns with the literature, which emphasizes the importance of CE strategies in decoupling economic growth from environmental degradation [2,3]. Potting et al. [4] described different circularity strategies prioritized according to their levels of circularity. The study’s results indicate that firms in the ’Very Sustainable’ cluster adopt these strategies more comprehensively, suggesting that this proactive approach may contribute to greater resource efficiency, reduced environmental impact, and stronger stakeholder engagement. In turn, these factors could enhance their competitive positioning while also positively influencing their corporate reputation by signaling a firm commitment to sustainability.

Furthermore, the findings revealed that CE-oriented collaborative relationships play a crucial role in implementing sustainable practices. Firms in the “Very Sustainable” cluster exhibited a greater tendency to share knowledge, data, and information with partners, as well as to participate in joint planning and decision-making processes. Such collaboration is essential to overcoming the challenges inherent in transitioning to circular supply chain models, as highlighted by Arroyabe et al. [5]. These scholars argue that collaborative relationships facilitate innovation, risk-sharing, and value creation across the supply chain, ultimately driving the adoption of circular economy practices [11,56].

ESG performance also emerged as a key factor differentiating the two clusters. Firms in the “Very Sustainable” cluster exhibited a significantly stronger commitment to carbon emissions reduction, prioritization of sustainable materials, optimization of waste management practices, and promotion of community development. These results support the view that integrating ESG factors into corporate operations can enhance reputation, attract investors, and foster long-term resilience [58,59,78].

Santolin et al. [58] and Fatimah et al. [52] argue that the environmental pillar of ESG closely aligns with CE principles, as both prioritize reducing carbon footprints, optimizing resource utilization, and mitigating environmental harm. Additionally, the social and governance dimensions of ESG can facilitate CE implementation by promoting responsible supply chain management, ethical labor practices, and regulatory compliance.

Logistic regression analysis revealed that specific measurement items related to CE strategies, CE-oriented collaborative relationships, and ESG performance were significant predictors of corporate reputation: avoiding the use of non-sustainable materials (CIR1); repurposing materials or by-products (CIR8); sharing a common understanding of CE concepts with partners (COL1); reducing carbon emissions (ESGG1); prioritizing the use of sustainable and ecological materials (ESGS3); and incorporating diverse perspectives in decision-making processes (ESGG2). These findings highlight the importance of a holistic approach to sustainability engagement, integrating CE strategies, CE-oriented collaborative relationships, and ESG performance to build a strong corporate reputation.

Our study extends previous research that reported that CSR initiatives indirectly contribute to firms’ reputation [55]. Previous research has also affirmed that firms can improve their reputation through ESG practices [79] due to a positive relationship between ESG performance and firms’ reputation [80]. Hence, ESG practices are of great importance to building corporate reputation and financial performance. Previous research emphasized the crucial role of CE practices as strategic assets that enhance a firm’s performance [81]. Companies invest in CE and ESG initiatives to achieve competitive advantage and increase their reputations [82] due to CE’s potential for cost savings and revenue generation [18]. Therefore, our study confirms the positive effects of CE strategies on firm reputation-building and extends previous research by identifying specific CE strategies that mostly contribute to an increase in firms’ reputation.

Lambooy [83] stated that firms must be concerned about ESG and reputation because of social demands. Thus, agri-food firms need to align their practices with these societal values to enhance their reputation [18]. Researchers also reported that several firms have adopted practices concerned with the governance of sustainable initiatives within CSR initiatives [84] to be closely aligned with societal demands and manage their ESG and reputational risks [85]. It has also been reported that firms must use their own resources and collaborate with other partners to acquire new capabilities to increase their reputation and deal with social and environmental issues [86]. This study extends previous research by identifying ESG factors that have a strong effect on agri-food firms’ reputations. Moreover, this study answers calls for more studies on the effect of CE practices on different aspects of firms’ performance in developing countries. Researchers also state that knowledge of the effects of circular economy practices on firm performance remains fragmented [27]. Thus, our study contributes by showing that some CE practices have significant effects on firms’ reputations, which can be considered a facet of firms’ performance.

These findings also underscore the multidimensional nature of corporate reputation, demonstrating that CE strategies, collaborative engagement, and strong ESG practices collectively contribute to firms’ reputation. The identification of CIR1 and CIR8 as significant predictors reinforces the notion that material efficiency and circularity enhance corporate image, aligning with prior literature that emphasizes waste reduction as a key reputational driver. Additionally, the importance of COL1 suggests that firms that actively engage their supply chain partners in sustainability efforts are perceived as more reliable and forward-thinking, highlighting the role of strategic collaboration in reputation-building.

From an ESG perspective, the predictive power of ethical compliance (ESGG1) and financial transparency (ESGG2) reflects the growing demand for integrity and accountability in corporate operations. Companies that maintain strong governance mechanisms and ensure compliance with ethical and financial standards are more likely to gain stakeholder confidence and long-term loyalty. Similarly, ESGS3 confirms the impact of social responsibility on corporate perception, reinforcing that firms that prioritize fair labor practices and workplace equity strengthen their brand value.

Finally, corporate reputation analysis revealed a significant difference between the two clusters, with the “Very Sustainable” cluster achieving a substantially higher average reputation score than the “Low-Sustainable” cluster. This suggests that firms that adopt CE practices, cultivate collaborative relationships, and demonstrate strong ESG performance are perceived as more trustworthy, responsible, and valuable by stakeholders. These findings align with the literature, which highlights reputation as a bridge between sustainability practices, stakeholder engagement, and organizational success. Carter et al. [13] and Castro [12] argue that firms with a strong sustainability reputation are more likely to attract customers, investors, and employees, providing them with a competitive edge in the market.

5.1. Theoretical and Methodological Contributions

This study reinforces the argument that sustainability engagement should be analyzed as an integrated construct rather than as separate dimensions. While previous research has often examined CE strategies, collaborative relationships, and ESG performance in isolation [1,10], our findings indicate that these components may be deeply interdependent, influencing both internal corporate operations and external perceptions of reputation. The empirical validation of a unified sustainability model strengthens the notion that companies adopting a holistic sustainability approach may enhance stakeholder trust and legitimacy [16,17,44].

Additionally, this research expands discussions on corporate reputation as a function of sustainability strategies [15,16]. Prior studies have primarily emphasized the reputational benefits of isolated ESG practices or collaborative relationships. In contrast, this study suggests that corporate reputation might be significantly shaped by the degree of alignment between CE strategies, partnerships, and ESG commitments. By identifying key predictors—such as avoiding non-sustainable materials, repurposing by-products, fostering shared visions with partners, ensuring fair labor practices, and maintaining financial transparency—this study provides a quantifiable framework for assessing the sustainability factors that most directly influence corporate reputation.

From a methodological standpoint, this study contributes to the integration of cluster analysis and logistic regression in sustainability research. The two-step empirical approach not only segments firms based on their sustainability engagement levels but also offers predictive insights into which sustainability elements may exert the strongest influence on corporate reputation. This methodological advancement establishes a replicable framework for future studies examining the multidimensional impacts of sustainability adoption across industries.

This study extends the NRBV theory by showing that the development of CE strategies supported by CE-oriented collaborations and ESG practices supports an increase in firms’ reputation. Although these antecedents are associated with all dimensions of the NRBV theory, this study has a unique and more specific contribution to the development of the capabilities related to pollution prevention and product stewardship, which are related to initiatives focused on the reduction in the contamination of the environment and the development of new products following sustainable-related guidelines in order to fulfill stakeholders’ needs [21,22]. This study contributes to the NRBV theory, corroborating that adopting CE strategies influences the achievement of a greater reputation.

This study also extends the RV theory, which posits that governance mechanisms influence the willingness of firms to engage in collaborative relationships [24,87]. These mechanisms protect firms, making them more inclined to engage in these relationships due to the belief that their partners are trustworthy. Our study includes ESG initiatives within the Sustainable Engagement construct, establishing guidelines that increase firms’ trust in relationships with other partners. Aligned with this theory, our study showed that CE-oriented collaborative relationships have a positive effect on firms’ reputations. Our study extends the RV theory by considering CE-oriented collaboration as a firm’s asset [88] as well as the adoption of CE strategies and ESG practices. This study corroborates the RV theory by showing that CE-oriented collaborations, supported by ESG practices and CE strategies, contribute to the achievement of a firm’s reputation. From a theoretical perspective, this study contributes to the Relational View and NRBV theories by demonstrating that collaborating firms achieve higher sustainable performance, which can be a source of competitive advantage. Finally, from a firm’s perspective, the findings of this research may reinforce the strategic importance of a collaborative relationship approach in the supply chain, leveraging sustainable performance.

5.2. Practical Implications

The findings of this study provide valuable insights for corporate leaders, sustainability officers, and policymakers seeking to align sustainability strategies with reputational benefits. As organizations increasingly transition toward circular economy models and move away from linear production systems, the results offer empirical evidence on how firms may strategically enhance their corporate reputation through sustainability engagement.

One of the most significant managerial implications is that sustainability engagement should not be viewed as a compliance-driven obligation but rather as a strategic investment with long-term reputational and financial advantages. Firms that proactively implement circular economy strategies, foster CE-oriented collaborative relationships, and uphold high ESG performance standards may gain greater stakeholder trust. This, in turn, might translate into stronger customer loyalty, improved investor confidence, and enhanced brand credibility. Conversely, growing regulatory and consumer pressure for sustainability means that companies failing to adopt an integrated approach—encompassing CE strategies, collaborative relationships, and ESG—might face reputational damage and declining market competitiveness.

Furthermore, this study underscores the critical role of stakeholder collaboration in maximizing the impact of sustainability initiatives. Companies that align their sustainability objectives with those of their supply chain partners—developing joint sustainability targets, fostering shared visions, and maintaining transparent governance structures—are more likely to achieve long-term sustainability success. This suggests that firms should move beyond fragmented sustainability efforts and actively engage in multi-stakeholder collaborations, including industry consortia, supplier partnerships, and cross-sector initiatives. Such collaborative models not only strengthen corporate reputation but also create shared value across the supply chain, reinforcing the long-term viability of sustainability-driven business models. This study extends prior research indicating that inter-organizational collaboration positively affects agri-food firms’ sustainable performance [63,64].

A predictive model of corporate reputation reveals that firms committed to a multidimensional approach to sustainability engagement are more likely to be perceived favorably by stakeholders. The findings suggest that corporate reputation is not shaped by isolated sustainability efforts but rather by the synergistic alignment of multiple dimensions, including sustainable material sourcing, circular repurposing of by-products, fostering a shared vision with partners, adherence to ethical labor standards, financial transparency, and strong governance mechanisms.

This reinforces the idea that reputation is not merely an outcome of compliance-driven sustainability actions, but a reflection of how deeply embedded sustainability principles are within corporate strategy. Companies that are truly engaged in sustainability initiatives tend to develop stronger reputational advantages. This study also responds to calls for assessing the differences in sustainability outcomes between firms that adopt ESG standards and those that do not [89].

From a regulatory standpoint, this study suggests that policymakers should focus not only on enforcing compliance but also on creating incentives for companies to develop holistic sustainability engagement initiatives. Instead of isolated regulations targeting specific CE or ESG practices, governments, and international bodies might benefit from encouraging integrated sustainability efforts that reward companies for long-term commitments. By shifting the focus from compliance to proactive engagement, regulators may accelerate corporate sustainability adoption while simultaneously enhancing the reputational advantages associated with sustainable business models.

Finally, communication and transparency play a pivotal role in ensuring that sustainability efforts translate into reputational gains. Expanding on the direct results of our study, we propose that firms actively disclosing their sustainability strategies, ESG performance, and circular economy commitments—through detailed sustainability reports, third-party certifications, and industry rankings—may be more likely to gain credibility and stakeholder trust. However, transparency alone is not sufficient. Companies must also ensure that their sustainability commitments are authentic, consistently implemented, and aligned with core business strategies. Cases of greenwashing—where firms exaggerate or misrepresent their sustainability initiatives—can severely backfire, leading to stakeholder skepticism and reputational damage. Thus, sustainability reporting should be rigorous, data-driven, and independently verified to build legitimacy and stakeholder confidence.

6. Conclusions

Based on the analyses conducted and the discussions presented, this study provides valuable insights into the interconnectedness of CE strategies, CE-oriented collaborative relationships, ESG performance, and corporate reputation. The findings indicate that firms that demonstrate stronger sustainability engagement—through resource efficiency, collaborative alignment with supply chain partners, ethical governance, and social responsibility—tend to enhance their corporate perception. The ability to repurpose materials, maintain financial transparency, adhere to ethical labor standards, and foster shared sustainability objectives across the value chain also contributes to strengthening stakeholder trust and reinforcing corporate credibility. These elements collectively emphasize that sustainability is not merely a strategic initiative but a foundational pillar for long-term reputational success.

These findings are particularly relevant to Brazilian agribusiness, a sector of strategic importance to the national economy, which directly manages vast natural resources while facing significant socio-environmental challenges. Beyond regulatory compliance, agribusiness firms may benefit from incorporating circular economy principles and ESG commitments as core elements of their operations and governance. Investing in practices such as by-product recovery, efficient input usage (e.g., water and fertilizers), and the adoption of clean technologies across the supply chain may enhance operational resilience, address growing global demands for sustainable products, and strengthen corporate reputation among stakeholders. Moreover, forging collaborative partnerships with suppliers, local communities, and regulatory agencies could foster regenerative solutions and drive socio-economic development in the regions where these firms operate. Aligned with governance and transparency measures discussed earlier, these initiatives not only enhance public trust but also help organizations navigate rapidly evolving market and regulatory pressures, reinforcing the strategic value of sustainability-driven transformations.

The cluster analysis revealed two distinct groups of firms: a “Very Sustainable” cluster, characterized by high engagement in CE strategies, collaborative stakeholder relationships, and ESG performance, and a “Low-Sustainable” cluster, which demonstrated significantly lower adherence to these practices. The stark contrast between these groups underscores the importance of an integrated approach to sustainability, where firms that actively pursue sustainability initiatives tend to cultivate a stronger corporate image. These findings also highlight the reputational risks for companies that fail to engage in sustainability practices, as they may face increasing scrutiny from stakeholders, investors, and regulatory bodies.

In light of pressing environmental and social challenges, transitioning from linear to circular economic models has become imperative. This shift requires companies to rethink supply chain processes, resource management, and stakeholder relationships, while also strengthening governance structures and fostering strategic partnerships across the value chain. Additionally, embracing sustainability as a core business strategy may empower firms to position themselves as leaders in the transition toward more equitable, transparent, and regenerative business models.

Limitations to the Study and Future Research Directions

It is important to recognize certain limitations that may affect the interpretation and generalizability of this study’s findings. First, the study relies on cross-sectional data, which capture firm behavior at a single point in time. This limits our ability to comprehensively assess the relationships between sustainability engagement and corporate reputation. Future research could employ longitudinal studies to track changes over time and better understand how sustainability engagement transformations affect reputation in the long run.

Second, the sample is limited to firms within the Brazilian agribusiness sector, which, while relevant due to its high environmental impact, restricts the external validity of the findings. The degree to which the identified relationships hold in other industries or geographic regions remains an open question. Comparative studies across different economic sectors and institutional environments could help determine the extent to which these findings apply to other contexts.

Third, the study relies on self-reported data from executives and managers, which may introduce common method bias or social desirability effects. Although statistical tests were conducted to mitigate such concerns, future research could incorporate triangulation methods, such as combining survey data with secondary data sources (e.g., sustainability reports, financial disclosures, ESG ratings) to enhance robustness.

Fourth, the cluster analysis and logistic regression models provide a structured analytical approach, but they do not account for possible moderating or mediating effects between CE strategies, collaboration, and ESG performance. Future research could explore structural equation modeling (SEM) or hierarchical models to uncover deeper interdependencies among these constructs.

Finally, the study does not fully consider external shocks or dynamic factors, such as changes in regulatory frameworks, technological innovations, or market pressures, which may alter the relationship between sustainability engagement and corporate reputation over time. Future research could integrate scenario analysis or agent-based modeling to simulate the potential evolution of these relationships under different conditions.

Building upon the limitations outlined above, we propose several promising avenues for future research:

- Longitudinal studies on sustainability and reputation dynamics: Future research should track firms over time to assess how sustained engagement with CE strategies, ESG commitments, and collaborative relationships translates into reputational benefits in the long run;

- Cross-industry and cross-country comparative analyses: Investigating how sustainability engagement influences corporate reputation in different industries and regulatory environments could provide deeper insights into institutional contingencies and cultural variations in sustainability adoption;

- Expanding methodological approaches: Employing structural equation modeling (SEM) could help clarify the causal pathways between sustainability engagement dimensions and corporate reputation, while experimental or quasi-experimental designs could test specific interventions;

- Exploring stakeholder perceptions and investor reactions: Future studies could incorporate consumer sentiment analysis, social media analytics, or investor behavior modeling to understand how external stakeholders perceive and react to firms’ sustainability initiatives;

- Examining the role of digitalization and AI in sustainability engagement: With the rise in data-driven sustainability metrics, blockchain for supply chain transparency, and AI-driven ESG assessments, future research could explore how digital transformation enhances or constrains sustainability-driven reputation-building;

- Investigating resilience and adaptation mechanisms: Given the increasing environmental uncertainties, studying how firms use CE strategies and ESG mechanisms as tools for risk mitigation and resilience building could further advance the understanding of sustainability as a long-term competitive strategy.