Abstract

In the European Green Deal and Renovation Wave framework, cities should be more self-sufficient and sustainable, promoting investment in the regeneration and maintenance of the built and natural heritage. The New European Bauhaus reinforces this vision, promoting the value of beauty as a product of environmental harmony/sustainability and participation. Many cities are already working to improve infrastructure and public services, with the aim of creating better socio-economic and environmental conditions in urbanised areas. At the same time, they aim to increase and relocate attractiveness and competitiveness to less densified rural areas, and to reduce overcrowding problems in cities. The aim is to propose a virtuous model of circular regeneration, by identifying virtuous strategies of the regeneration of rural villages capable of aligning the transformation of the built environment with climate objectives, social cohesion and local economy strengthening, and the integration of historical and identity values. Rural villages in marginal areas are left behind places. They require new economic development strategies, grounded in a circular bio-economy model for reducing/avoiding spiraled down processes. The application of European evaluation criteria to the main topic literature background allowed for the construction of a virtuous practices observatory about regenerated rural villages, which is elaborated using registry, systemic, and analytical/analysis forms. From the ex-post evaluation analysis of the case studies, it was possible to identify a number of dimensions/clusters in which investment is being made today for the regeneration of rural villages. By reasoning on the investment clusters, it was possible to identify a circular regeneration model for rural villages, transferable to other realities in order to implement the broader vision of circular settlement development. The “Rural Village Regeneration Model” represents an operational tool for regional transformation, suitable for reactivating lost connections between rural villages and larger towns in functional areas, characterised by greater self-sufficiency and exploration of the potential of digital tools to improve services, connections, infrastructure, and cooperation.

1. Introduction

Considering the essential role of rural villages and communities both for the implementation of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals [1] and for alignment with the development perspectives enshrined in 2023 by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP28) [2], the regeneration of rural Europe is the key to safeguarding the diversity of the built environment continent. The economic, environmental, cultural, and social diversity that characterises rural Europe invests more than half of the population of the European Union and encompasses more than three-quarters of its territory [3]. Although urban centres and rural villages, with their populations, benefit from different goods, they need to be, however, complementary through the improvement of the relationships and partnerships that bind them. This as a condition is fundamental to be achieved in the coming years for the fulfilment of economic requirements, social and environmental instances, and performance of the built environment of the European Union [4]. In this challenge, the value of resources rooted in the historical and local production of rural villages and hamlets can offer a sustainable solution to mitigate the countryside exodus of citizens in search of better services and job offers. Regenerating, therefore, rural villages can represent the action from which to trigger widespread recovery, which is capable of making these places newly attractive to communities, thus affecting, on the one hand, improved access to services, and on the other hand, entrepreneurial opportunities in traditional rural sectors and new sectors of the local rooted economy [5]. Indeed, in a circular perspective, value chains can pose as engines of rural growth, providing jobs and livelihoods in villages to contribute to the quality of life of more than ten million European inhabitants that are not able to move elsewhere [6].

Aware of the role played by rooted rural production in defining landscapes and the importance of these activities as custodians of the rural territory [7] related to the protection of biodiversity, soil and water resources, and climate protection, the research builds an atlas of good practices of regeneration of rural villages.

Paper Objectives

The aim of the paper is to propose a virtuous model of circular regeneration for rural villages, by identifying virtuous strategies for the regeneration of rural villages capable of aligning the transformation of the built environment with climate objectives, thereby strengthening social cohesion, the local bio-economy, and the integration of historical and identity values.

To achieve this, different best practices of rural village regeneration have been analysed, through which it was possible to identify several dimensions/clusters in which investment is being made today for the regeneration of rural villages, in the perspective of a new circular bio-economy strategy in rural areas. Here, the localisation of activities can be stimulated for the production of bio-materials (such as bio-plastics resulting from the fermentation of products by agriculture, bio-plastics based on cellulose, protein, etc.), which are degradable materials that can substitute those of fossil origin.

The above-mentioned aspects are especially for the benefit of young people who are the subjects in the rural areas who suffer most from being ‘left behind’, despite the solemn and repeated promise of Agenda 2030 [1].

2. Methodology

The methodology follows a circular process [8] in which the output of one phase represents the input of the next and, at the same time, allows the entire process to be improved. The methodology consists of different phases: (a) Rural village regeneration in the European framework; (b) a virtuous practices observatory to elaborate a European regenerated rural villages atlas; (c) the registry, systemic, and analytical analysis forms of European rural villages; (d) identification of dimensions/clusters for the regeneration of rural villages from the perspective of the circular bio-economy to the main topic literature background; (e) a comparative analysis of rural regeneration case studies; (f) the analysis of the compass evaluation method as a tool that is capable of assessing and monitoring the impacts of rural village regeneration projects; (g) the realisation of a regeneration model for the European rural village with a community-based approach, transferable to cities and neighbourhoods to implement the broader vision of circular settlement development.

Furthermore, the evaluation of the recurring and dominant features in the mapping carried out makes it possible to elaborate a model of rural village regeneration. As the sample can be expanded through the replicability of the model, the latter is susceptible to continuous refinement according to the feedback principle (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Methodological flowchart.

3. Rural Village Regeneration in the European Framework

As the European rural regions comprise over 341 million hectares, constituting 83% of the total EU area, divided into 165.5 million ha of areas away from cities and 176.6 million ha of near-urban sites [7], the topic of rural village regeneration is the core of the European debate on the transformation of the built environment. Defined in 2005 by the Faro Convention, cultural heritage—including rural villages—is the set of resources inherited from the past, and the heritage community is the set of people who value that heritage [9]. Implemented in 2011 by UNESCO, cultural heritage is also considered, in its tangible and intangible components, as a key resource to improve the liveability of urban areas, which is able to foster economic growth and social cohesion in an evolving global context [10]. In 2018, the Agenda for Culture proposes to hold together within the regeneration process of rural villages both the value of local productions rooted in the territories, which have defined their appearance over the centuries and the value of the sharing of skills, which in combination, improve the quality of the choices to be made on the landscape [11]. As in the past, nowadays the rural village is recognised as having the ability to promote and support social, cultural, economic, profound and lasting changes.

The European Green Deal addresses the regeneration of rural villages through the promotion of the economic, environmental, technological, social and cultural prosperity of these areas, starting with the search for innovative, inclusive, and sustainable strategic actions to address the current and future challenges of rural communities [11]. The European Commission in the document “Vision about rural areas” claims that such strategic actions can be found by drawing on the identity and dynamism of rural areas by integrated regeneration methods and multi-sectoral approaches [12]. On the one hand, it is necessary to promote diversification and support entrepreneurship, investment, innovation and employment. On the other hand, such actions must be guided by principles based on the enhancement of rural identity to strengthen sustainability, social inclusion, and local development, as well as the resilience of rural communities and production rooted in the territory [1].

The Renovation Wave framework proposes that cities should be more self-sufficient and sustainable, promoting investment in the regeneration and maintenance of the built heritage [13]. In the case of rural villages, this means strengthening local value chains and production networks, identifying those opportunities linked to the circular economy that are based on new approaches to horizontal and vertical integration, fair and transparent, between the supply chain and the processing and distribution chain [14]. The support of European Union for investments in rural villages focuses primarily on bringing added value to society. On the one hand, in terms of the development of productivity rooted in the territorial tradition in a diversified and competitive way; and on the other hand, in terms of increasing services aimed at bridging the digital divide and developing the potential offered by the connectivity and digitalisation of rural villages with urban ones [5].

In this perspective, the Cork Declaration [15] proves to be more topical than ever, since as early as 2016, it aimed to inspire more flexible and targeted policies and initiatives to develop models, strategies, and tools for the regeneration of rural villages, in which the performance and empowerment of citizens through involvement can be improved. The document refers to the ecological transition and the revitalisation of rural villages that have emerged as central goals in international policies, aimed at protecting their cultural and landscape heritage. Various types of built heritage, reflecting their historical development over time, mark these rural villages. Despite their role as guardians of cultural and historical identities, rural villages are facing challenges like depopulation and insufficient service and infrastructure performance. Building on this theme, in 2017, the European Commission introduced the ’EU Action for Smart Villages’, which outlines sixteen key initiatives to promote innovation and sustainability in rural regeneration projects. These actions are designed to improve rural village life by encouraging smart governance, digitalisation, infrastructure upgrades, environmental sustainability, and community development. In response to these suggestions, the Smart Eco-Social Villages Pilot Project was launched to study best practices in rural regeneration projects that involve local communities in defining development strategies [16].

In line with international policies and initiatives, the ’Second Preparatory Action on Smart Rural Areas for the 21st Century’, commonly referred to as the “Smart Rural 27” project [17], was launched in 2020 to support the creation of smart villages across the European Union. This initiative aims to transform rural regions into sustainable and innovative growth models. As part of the project, a tool called the ‘Smart Rural 27 Geomapping Tool’ was developed, which provides an overview of the strategies adopted by the villages participating in the Smart Rural 27 project.

In 2021, the European Commission introduced the “New European Bauhaus (NEB)” [17], an international initiative that focuses on promoting solutions for the built environment that are sustainable, inclusive and visually attractive, while respecting the diversity of local cultures and regions. The NEB follows a community-based approach, aiming to provide tailor-made solutions that incorporate diverse and participatory perspectives into the rehabilitation and regeneration processes of both rural villages and urban centres.

The New European Bauhaus reinforces this vision, promoting the value of beauty as a product of participation and environmental sustainability [18]. The management of the rural territory starts from the actions of regeneration and conservation of the cultural heritage as a symbol of European custodianship of the great diversity of faunal and vegetal habitats and of the landscape attractions, that depend to a large extent on the productive activity rooted in the local tradition which have determined it over time. Rural villages play an essential role in the interface between citizens and the environment. The “intrinsic value” of the rural village landscape offers advantages for economic and cultural development that must be cultivated to protect the environment while preserving historical beauty, generating attractive capacity, and social inclusion [19,20]. In rural villages, the increasing pressure on natural resources needs to be mitigated to reverse the loss of diversity and ensure their maintenance and sustainable use for young and future generations. In this regard, the Local Governments for Sustainability (ICLEI) [21] supports the challenge of climate change, in both rural and urban areas, by researching strategies that encourage the participation of rural communities in the development processes of the circular bio-economy and the transformation of the built environment based on the use of biomaterials.

Also, the ARUP design studio is conducting a research project entitled ‘Regenerating European Villages: Towards a Vision for Smart Rural Areas in the Post-Pandemic Futures’ [22], which focuses on the analysis of a series of case studies with the aim of identifying the main success factors of rural village regeneration projects. The project provides a vision of European village regeneration based on five pillars: defining territorial strategies, strengthening sustainable development, investing in human capital, promoting innovation, and enhancing local heritage.

In order to develop the necessary skills in rural communities for these scenarios, the paper looks to European policies with guidelines focused on strengthening exchanges, networking and cooperation between industry, researchers, practitioners, civil society and public authorities. Rural villages can be a viable alternative to unsustainable urban areas, offering a better quality of life due to their proximity to nature and lower population density, thereby providing a refuge from the hectic urban lifestyle. They have a valuable cultural heritage and are often abandoned/underused, which can be an effective trigger for circuit regeneration processes [20]. Their reuse/regeneration contributes to the preservation of architectural heritage, as well as to the realisation of multifunctional spaces that promote economic growth and social cohesion in rural villages, without generating negative environmental impacts from new constructions. This vision implements the Next Generation EU programme in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, which redefines the framework of intervention priorities at the urban scale, focuses on experimental measures and pilot actions that regenerate quality to the built environment, and counteracts both ecological and economic poverty and depopulation [18].

4. A Virtuous Practices Observatory to Elaborate a European Regenerated Rural Villages Atlas

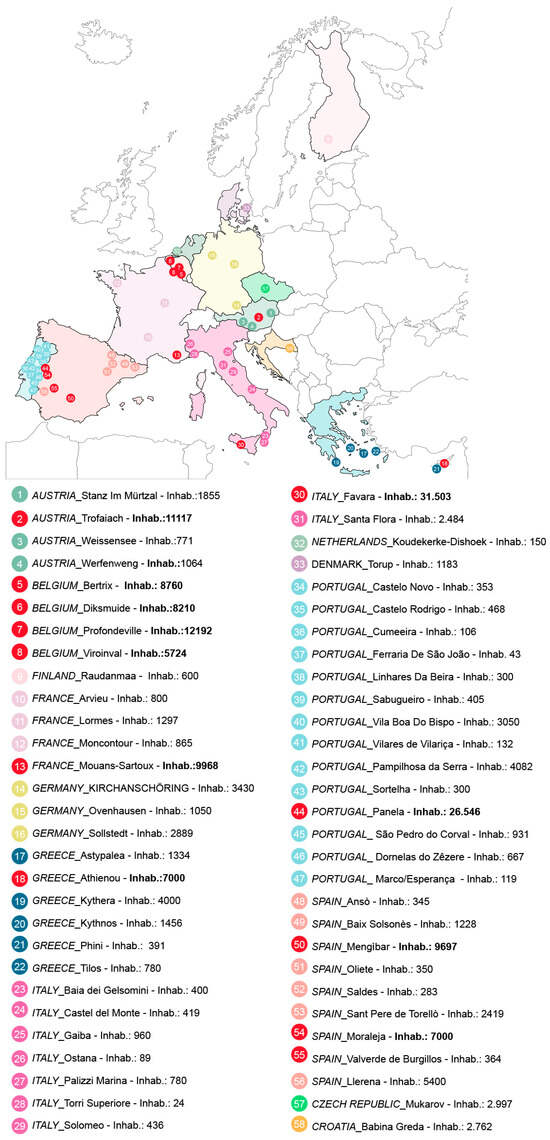

Compliance with the criteria as selection requirements allows us to identify an observatory of virtuous practices to develop a European regenerated rural villages atlas (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The Atlas of the European best regenerated rural villages.

The atlas specifically highlights 58 rural villages across different countries. Each village is marked with a numbered dot that corresponds to a list on the right-hand side, providing the village name, its location (country and region), and the population (“Ab.” stands for the number of inhabitants). These villages are likely part of a broader European initiative focused on revitalising rural areas, improving sustainability, and addressing the challenges of depopulation and infrastructure deficiencies.

The atlas illustrates a broad geographical spread of rural villages across Europe, ranging from Northern to Southern regions. The countries represented include Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Finland, Denmark, Czech Republic, Croatia, and the Netherlands.

Certain countries have more densely concentrated groups of villages, such as France, Spain, and Portugal, which show a large number of villages spread out across multiple regions, indicating significant involvement in rural development projects.

Austria is represented by four villages, all located in different regions. The populations of these villages range widely: Stanz im Mürztal in Styria has 1855 residents, while Trofaiach in the same region has a significantly larger population of 11,117, making it one of the largest villages shown on the map. Weissensee in Carinthia has a small population of 771, while Werfenweng near Salzburg has 1064 inhabitants. This diverse range suggests that the participation of Austria spans both larger and smaller rural communities.

The village of Stanz im Mürztal stands out for its pioneering approach to economic development and sustainability, particularly in the field of renewable energy and local economy stimulation. A key initiative is the Local Agenda 21, which aims to counteract the depopulation of mountain areas by fostering a sustainable energy community and increasing citizen awareness. One of the most innovative aspects is the exploration of a virtual local currency to stimulate the village economy.

The community participation plays a crucial role in the regeneration process of rural villages. The Local Agenda 21 has engaged approximately 80 active residents in developing a strategic framework for the village, with a strong focus on energy transition and sustainability. The village has also invested in social cohesion by creating new spaces and facilities for young people and the elderly, fostering intergenerational interaction and improving the overall quality of life.

On a material level, green building and energy-efficient renovations are key elements of the development of Stanz. Empty buildings in the town centre have been renovated following sustainable construction principles, making them more energy-efficient and environmentally friendly. In addition, the construction of a multifunctional centre has further enriched village life, offering affordable housing, a regional food and product shop, service facilities, and a new municipal administration building.

Belgium stands out with a cluster of villages concentrated in Wallonia, the southern, French-speaking region of the country. The largest village is Profondeville with 12,192 inhabitants, followed by Diksmuide with 8210 and Bertrix with 8760 residents. Smaller villages include Viroinval with 5724 and Virton with 5000. These villages likely play key roles in regional sustainability and rural revitalisation projects.

France has a significant presence on the map, with rural villages spread across different regions. The most populous is Mouans-Sartoux in Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur, with 9968 inhabitants. Other villages, such as Arvieu in Occitania and Lormes in Burgundy, have populations closer to 800 and 1297, respectively. Moncontour in Brittany has a smaller population of 865. The wide range of regions—from Burgundy to Occitania and Provence—demonstrates that the deep involvement of France in the project, likely focusing on diverse geographical and cultural challenges.

Germany features several villages, primarily located in Bavaria and Westphalia. The most populous village is Kirchanschöring in Bavaria, with 3430 residents, while the smallest village is Ovenhausen in North Rhine-Westphalia with only 1050 inhabitants. Sollstedt, in Thuringia, falls in between with a population of 2889. These villages could be involved in modernising rural infrastructure and enhancing environmental sustainability.

Greece has a unique representation with several islands featured, such as Astypalea in the Kalymnos region with 1334 inhabitants, and Kythera in Attica with 4000 inhabitants. These villages are not located on the mainland, indicating that the rural initiative also targets island communities. Phini in Cyprus with 391 inhabitants and Tilos in the Dodecanese with 780 inhabitants are small but significant participants in rural transformation efforts.

In particular, the island of Kythnos is one of the most interesting cases. Kythnos has a long history of adopting sustainable energy applications, beginning with installing Europe’s first wind farm in 1982, followed by various renewable energy and storage projects. In 2000, the island implemented a fully automated smart energy system powered by local wind and solar resources. Furthermore, in 2001, Kythnos hosted one of the first microgrid trials, providing invaluable knowledge to the scientific community and industry about how such systems function. Since 2015, the island has experienced a renewed focus on sustainability, serving as a living lab for clean energy under the WiseGRID project, which culminated in the large-scale launch of “Kythnos Smart Island” in 2019. This initiative integrates smart infrastructure management with economic development, establishing Kythnos as a model green destination.

Kythnos actively promotes community participation, economic diversification, and knowledge-sharing. The Kythnos Smart Island project serves as a development strategy for the island and as an inspiration for other remote and rural communities, transferring valuable insights for future smart and sustainable destinations. A strong emphasis is placed on collaboration with local entrepreneurs to ensure that the smart village strategy drives sustainable economic growth while extending the tourist season beyond summer. On a physical level, Kythnos is investing in the adaptive reuse of public buildings, infrastructure upgrades, and sustainable mobility. Existing port facilities and urban areas have undergone rehabilitation, ensuring they align with modern sustainability standards. The project also integrates comprehensive water resource management, reducing water production costs and distribution losses. The public lighting system has been restructured, enhancing visual comfort while minimising light pollution. Additionally, efforts are being made to decarbonise transportation sector in the island, adopting electric mobility solutions for both land and maritime transport.

Spain is one of the most densely represented countries on the map, with numerous villages located across different regions, including Catalonia, Aragon, and Andalusia. The largest village is Mengíbar in Andalusia with 9697 inhabitants, while smaller villages like Saldes in Catalonia with 283 inhabitants and Oliete in Aragon with 350 inhabitants demonstrate a broad range of participation. The geographic spread within Spain suggests an emphasis on tackling regional disparities in rural development, particularly in southern and northeastern areas, where depopulation and infrastructure development may be pressing issues.

Portugal also features a wide array of villages, mostly concentrated in the Centro and Norte regions. The smallest village is Ferraria de São João with just 43 residents, indicating an effort to sustain even the smallest rural communities. Other villages, like Castelo Rodrigo and Sabugueiro, have populations between 300 and 400. Vila Boa Do Bispo in the Norte region stands out with a population of 3050. The range of sizes shows that Portugal is focusing on revitalising a diverse set of rural areas.

There are two particularly virtuous practices in this country: Pampilhosa da Serra and Sortelha.

Pampilhosa da Serra stands out for its strong support for local entrepreneurship, thanks to the development of an Entrepreneurship Support Office, which facilitates business creation, promotes training and encourages sustainable economic development, with a focus on local agriculture and family businesses. This support is complemented by initiatives such as “Criar Vale la Pena” and funding tenders to attract private and public investment.

The village focuses on social cohesion and inclusion, implementing projects to reduce depopulation and create intergenerational communities. Programmes such as the “Banco do Tempo” promote volunteering and mutual support, while initiatives such as the “Municipal Senior Card” encourage the participation of the over 60s in cultural and sporting life. Strengthening local identity through community events and innovative educational programmes is central in this regeneration process. On the physical side, the municipality invests in heritage and sustainability, with interventions such as the recovery of abandoned houses “SOS—Casas Abandonadas e Habitação Apoiada”, the rehabilitation of the municipal market, and the promotion of sustainable tourism with the European project “Portas do Céu”. It is also improving access to services and infrastructure through Flexible Transport on Demand and the redevelopment of public spaces such as primary and secondary schools.

On the other hand, the village of Sortelha stands out for its strong commitment to economic and business development, with initiatives such as the “Competitive Rurality” strategy, which integrates agriculture, forestry, and livestock farming through innovation and sustainability, the “Sabugal Investe” programme that encourages the creation of new businesses, and the ENERTECH event serves as a platform for the promotion of innovative energy technologies. In addition, through the “Smart Work Centre”, co-funded with EU, Sortelha promotes smartworking and the attraction of digital professionals and start-ups, contributing to the economic diversification of the area. To promote social cohesion and inclusion, the municipality has also adopted measures like offering free transport and school materials, facilities for families in difficulty, support for the disabled, and initiatives for the elderly. Another strong point is the promotion of sustainability and local identity, with the “Circular Interna” project, which improves sustainable mobility through walking and cycling routes, and the “Classification and enhancement of trees of municipal interest” initiative, which protects the natural heritage.

On the physical side, Sortelha is focusing on enhancing its historical and environmental heritage. The restoration of the Alfaiates Castle and the project for the five Medieval Villages aim to preserve and promote tourism, while the restoration of the banks of the River Côa extends the bathing areas and improves the river infrastructure. In addition, the improvement of the tourist information system and the creation of an interactive platform is modernising the visitor reception, making Sortelha a more accessible and attractive tourist destination.

Italy has several smaller villages participating in the initiative, such as Baia dei Gelsomini in Calabria with 400 inhabitants and Castel del Monte in Abruzzo with 419 inhabitants. Ostana in Piedmont, with only 89 residents, is the smallest Italian village on the map, reflecting the inclusion of even the most depopulated areas in rural sustainability efforts.

Many of the villages shown have populations under 1000, such as Rautamaa in Finland (600), Ostana in Italy (89), and Cumeira in Portugal (106). This underscores the focus of the initiative on the most vulnerable, depopulated rural areas. A substantial number of villages fall within the 1000 to 5000 population range, including Kirchanschöring in Germany (3430), Astypalea in Greece (1334), and Bertrix in Belgium (8760). These villages likely have more developed infrastructures but still face rural-specific challenges. A few villages have populations exceeding 9000, such as Mouans-Sartoux in France (9968), Mengíbar in Spain (9697), and Trofaiach in Austria (11,117). These larger rural communities may serve as hubs for surrounding smaller villages, offering more advanced services and infrastructure.

This atlas returns the European rural revitalisation programs map, which aims to improve infrastructure, foster innovation, and encourage sustainable practices in rural areas. By showcasing a diverse range of village sizes and geographic locations, the initiative likely seeks to address unique local challenges such as depopulation, environmental sustainability, digital transformation, and community engagement.

The atlas offers a comprehensive overview of key rural villages across Europe that are part of sustainability and regeneration initiatives. The diversity in population size and geographic location highlights the wide-ranging efforts across the EU to foster rural development and create resilient, vibrant communities that can thrive in the face of modern challenges.

4.1. The Registry, Systemic, and Analytical Analysis Forms of European Rural Villages

For each of the villages identified on the atlas and classified as best practice based on their compliance with the aforementioned criteria, a collection of the registry, systemic, and analytical analysis forms have been prepared (Figure 3). Each practice is identify by its atlas number (identified in the Figure 2) in the right corner. The registry section oreturns the geolocation, number of inhabitants, and image reference. The systemic section returns the technological description of the built environment of the village through its perceptual-cultural, morphological-dimensional, and material-constructive qualities [23].

Figure 3.

Sample of registry, systemic, and analytical analysis forms of European rural villages.

The perceptual-cultural constraints are related to the preservation of the aesthetic values of the intervention site; to the respect of historical instances, recognisable in the stratifications of a documentary character that have succeeded one another over the centuries; to the preservation of the psychological and perceptual values of the built resource, recognised by all those who enjoy it, directly or indirectly [23]. Morphological-dimensional constraints are associated with the geometric configuration of the site and its built heritage to be respected in intervention strategies [24]. Material-constructive constraints are based on respecting the behaviour of materials and technologies on the site where the intervention is planned [25].

4.2. Identification of Dimensions/Clusters for the Regeneration of Rural Villages from the Perspective of the Circular Economy to the Main Topic Literature Background

Identifying good and best practices in Europe of rural village regeneration means focusing on those cases where there is a concomitance between the ability to renovate and valorise local cultural heritage through cooperation in local communities, and the ability to achieve energy self-sufficiency and ecological development in a circular perspective.

To explore the state of the art of rural village regeneration in Europe, it is also necessary to identify the selected best practices for an in-depth analysis of success and obstacle factors, assessing the different levels of circularity based on the current stage of development, potential, business model, and participatory approaches.

For this reason, from the analysis of good practices carried out in the previous paragraph, dimensions/clusters have been identified in which rural regeneration projects/investments are more oriented.

These dimensions/clusters can be summarised as follows: economic dimension, environmental dimension, social dimension, cultural dimension, governmental dimension, technological dimension, mobility dimension, livability dimension.

The analysis of the rural village regeneration projects shows that they are often able to better improve the ‘economic dimension’ by investing in strategic actions that incentivise the development of new activities capable of strengthening the local economy according to the principles of the circular economy. These initiatives usually generate income streams and consequently create new jobs. Many of the good practices have promoted innovative entrepreneurship actions and initiatives, facilitating the creation of start-ups, and have stimulated sustainable economic growth through public and private investments, adopting diversified economic strategies aligned with EU funding initiatives.

In particular, in the good practices analysed, the ‘environmental dimension’ is implemented through actions in line with the principles of the circular economy. This involves the use of renewable energy, energy-efficient systems, as well as the responsible use of natural resources and waste recycling. Conservation of biodiversity and sustainable management of water resources are key elements in building resilient communities. One aspect that should not be overlooked is the mitigation of hydrogeological hazards in rural villages, which are increasingly vulnerable to landslides and floods. Addressing these risks not only protects communities, but also helps ensure a liveable and sustainable environment for future generations.

Actions aimed at better maximising the ‘social dimension’ should focus on strategies to strengthen social inclusion, sense of belonging, and accessibility to cultural sites. This approach ensures that everyone can enjoy cultural and scenic heritage. Social cohesion is promoted through interactions between different cultural groups, which foster the creation of communities. Such initiatives help build inclusive and dynamic environments for all community members.

The set of actions aimed at better maximising the ‘cultural dimension’ are a key component in enhancing and protecting the local cultural heritage of historic villages, as well as their identity. Enhancement of local heritage and promotion of local identity are key to preserving traditions and history, strengthening the link between community and territory. It is necessary to prevent the loss of intangible values through the implementation of innovative strategies designed to redevelop the areas that characterise the living fabric of these villages. This approach will encourage an influx of tourists, capable of revitalising the local economy. The attractiveness of cultural sites and rural heritage positions villages as new tourist destinations, combining scenic beauty and cultural richness, thus transforming heritage into an active resource for the future. Community awareness of the value of cultural heritage promotes social cohesion and strengthens place identity, thus contributing to improved quality of life.

To better guarantee the ‘governance dimension’ it is necessary to base all regeneration projects on participatory and collaborative approaches capable of involving public and private actors and the local community. Strengthening public–private partnership and co-design processes are necessary actions to ensure sustainable regeneration. In addition, local community participation and stakeholder involvement ensure that projects meet the needs of the population, strengthening the link with the local area. Urban-rural cooperation promotes balanced development, while knowledge sharing and networking increase the adaptive capacity of villages. Local governance should facilitate these processes by supporting small farms to foster a sustainable local economy. Finally, promoting beauty values and community resilience is essential to enhance cultural heritage and address future challenges, making participatory governance a pillar for the development of strong and cohesive villages.

The regeneration of rural villages in a ‘technological dimension’ offers a significant opportunity to improve quality of life and enhance cultural heritage. Digital innovation enables the implementation of smart solutions that increased the availability of services and accessibility in rural villages. It is crucial to reduce the digital divide to ensure that all communities, including rural ones, can take advantage of new technologies, which requires investment in infrastructure and digital training. Adoption of digital solutions allows for more efficient management of resources, particularly with regard to digitisation of heritage, facilitating the implementation of circular regeneration projects. In addition, integrating cultural values with innovation enriches local identity, contributing to a more dynamic and attractive environment.

The ‘mobility dimension’ is considered of paramount importance in promoting slow mobility, improving spatial connections, and ensuring an efficient public transportation system. This ensures that such villages are more connected to urban and peri-urban areas.

Regarding the ’livability dimension’, improving public spaces and the visual quality of the landscape plays a key role in enhancing the well-being condition of residents. Creating inclusive environments promotes socialisation and enriches the quality of life.

Finally, redevelopment of public spaces should be the priority of any rural village regeneration project, as these areas are seen as the places, where opportunities for recreation and socialisation are intensified, where culture is promoted and collective identity and memory are strengthened.

In conclusion, the ‘facilities dimension’, covers actions that aim at the provision of services covering health, education and training, and social services.

These services are essential to individual and collective well-being, as they help improve quality of life, promote social inclusion, and provide opportunities for growth and development. In essence, this dimension focuses on ensuring that every individual has access to resources that support his or her physical, mental, and social well-being, creating a solid foundation for a more equitable and resilient society.

5. A Comparative Analysis of Rural Regeneration Case Studies

After having identified, in the previous section, the dimensions/clusters in which rural regeneration is invested, a new re-reading of the case studies was carried out with the aim of understanding which dimension/cluster each good practice is most focused on.

In this approach, a comparative analysis of the 58 rural case studies was carried out with the aim of identifying a circular model of rural regeneration transferable to different similar contexts (Table 1) (in the table the symbol • suggest that in the different projects that dimensions/clusters has been implemented).

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of rural regeneration case studies.

The rural regeneration projects examined in various European villages show a holistic approach that consistently incorporates economic, environmental, social, cultural, governmental, technological, mobility, and livability dimensions, identified in the previous paragraphs, and creates a sustainable and integrated development model. From an economic perspective, many initiatives aim to revitalise local economies through innovation and diversification. For example, Favara (Italy) transformed abandoned spaces into artistic attractions, stimulating tourism and creating new job opportunities.

Similarly, Ferraria De São João (Portugal) developed the ‘Aldeia Viva’ project to engage visitors in traditional activities, generating income and preserving local practices.

In Greece, the island of Kythera is focusing on the promotion of local agriculture, with an emphasis on the production of olive oil, honey, and aromatic and medicinal plants. This initiative not only supports the local economy, but also aims to retain young people on the island, counteracting depopulation.

The social dimension is evident in projects such as that of Mukarov (Czech Republic), which implemented digital services to improve civic participation and access to services for all age groups. Torup (Denmark) has adopted a community approach with its “Tools & Talents” app, promoting sharing and strengthening social ties.

Also, in Greece, the village of Phini has adopted a participatory approach, involving a wide range of local and regional stakeholders in the organisation of conferences and development initiatives.

With respect to the cultural dimension, many villages are enhancing their unique heritage. Kythera (Greece), with its project to restore traditional paths, and Valverde de Burguillos (Spain), with the preservation of its water-related heritage, demonstrate how local culture can be an engine of regeneration. Santa Flora (Italy), with its “Smart Village” project, integrates digital innovation and the preservation of historical and artistic heritage.

The environmental sustainability dimension is a recurring theme in almost all projects. Baia dei Gelsomini (Italy) has invested in solar energy and rainwater harvesting, while Astypalea (Greece) is switching to electric vehicles and renewable energy. Werfenweng (Austria) focuses on soft mobility and sustainable tourism, demonstrating how the environment can be at the centre of economic development.

In Italy, several communities are focusing their efforts on energy independence and sustainability. Palizzi Marina in Calabria (Italy) is developing an energy community based on renewable sources, with the aim of reducing energy costs for residents and small local farmers. Similarly, Gaiba (Italy) is implementing an energy community project to sell electricity at reduced prices to the most vulnerable households, as well as to improve the energy efficiency of public buildings. A particularly interesting example of regeneration is Torri Superiore (Italy), where an abandoned medieval village has been transformed into a sustainable eco-village. The project recovered 62 rooms, creating a mix of private and shared spaces, using local natural materials and sustainable construction techniques.

A remarkable example of circular economy comes from the island of Tilos (Greece), where the ‘Just Go Zero Tilos’ project has achieved an impressive 86% recycling rate. This innovative programme turns food waste into fertiliser, converts non-recyclable materials into energy, and promotes the creative reuse of used clothes, appliances, and furniture.

These projects demonstrate that successful rural regeneration projects require a multidimensional approach. Indeed, each initiative seeks to balance economic growth, social cohesion, cultural preservation, and environmental responsibility. The interconnection of these dimensions is manifested in projects such as Mouans-Sartoux (France), where the organic canteen initiative not only promotes health (social dimension), but also supports local agriculture (economic dimension), preserves traditions (cultural dimension), and reduces environmental impact (environmental dimension).

These projects demonstrate how rural regeneration can be approached holistically, combining economic innovation, social cohesion, and environmental responsibility. Through these initiatives, rural villages are not only improving the quality of life of their inhabitants, but are also creating sustainable models that could inspire other communities across Europe.

It is clear that in the case studies analysed, models were developed that not only revitalise villages, but above all create resilient and sustainable communities, which are ready to face future challenges by preserving their traditions over time.

5.1. Compass Evaluation Method to Assess the Impacts of the Rural Villages Regeneration Projects

Rural regeneration projects are increasingly integrating New European Bauhaus (NEB) principles into various approaches, promoting a sustainable, inclusive, and creative approach to local community development, as demonstrated in the projects that ICLEI is carrying out (cfr. Paragraph 2).

In this context, to assess the impacts of rural village regeneration projects and to monitor them, the European Commission launched in 2024 “The Compass Evaluation Method” [26].

This tool allows “to measure” the impact of projects in social, economic, and environmental terms through specific indicators, gathering meaningful data on how a project can affect the community, local welfare and the environment, providing a clear picture of its results. One of the key features of Compass is that it allows progress to be monitored in real time during project implementation. This means that potential problems or delays can be identified early, enabling rapid action to resolve them.

In particular, the Compass evaluation method focuses on three specific macro areas called “values”, which are as follows:

- -

- Sustainable: A project is sustainable when it minimises environmental impacts, that is, when it “prioritizes the needs of all forms of life and the planet, ensuring that human activity does not exceed planetary boundaries.” A project is sustainable when it reconnects with nature and has positive impacts on lifestyles, relationships, and the economy (nota).

- -

- Beautiful: A project is beautiful when its authors invest in collective sensitivity, intelligence, and competences to create a positive and enriching experience for people, beyond functionality. A beautiful project is attentive to its context and users, encourages mutual care, and can be a powerful driver for change [26].

- -

- Inclusive: A project is inclusive when it ensures accessibility (physical, cognitive, psychological, etc.) and affordability for all, regardless of gender, race or ethnic origin, religion or belief, ability, age, or sexual orientation. An inclusive project becomes exemplary and replicable, if it has the potential to break obsolete social models, create value and bring transformative benefits on a societal level, thus influencing worldviews, paradigms, and social behaviors [26].

Specifically, the Compass evaluation method uses a set of indicators that “measure” the effectiveness of a project with respect to each of the three macro areas (values). With respect to “Sustainable value,” there are indicators that assess environmental impact, i.e., reduction in natural resource use, improvement of biodiversity, reduction in pollution and carbon footprint.

With respect to “Beautiful value”, there are indicators that assess innovation and creativity, i.e., new solutions in design, innovative use of materials, and use of modern technologies to improve the livability of spaces. With respect to “Inclusive value”, there are indicators that assess social impact, i.e., the creation of inclusive spaces, the improvement of social cohesion, accessibility to different sectors of the population (people with disabilities, minorities, etc.), and the creation of opportunities for civic participation [26].

In this paragraph, in Table 2, the eight dimensions/clusters (Economic, Social, Cultural, Environmental, Governance, Technological, Infrastructure, Mobility, and Livability), identified in Section 4.2, have been associated with respect to the three “values” of the Compass assessment tool, with the aim of integrating this tool with respect to the dimensions/clusters in which rural village regeneration projects are being invested today (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Compass evaluation method to assess rural village regeneration projects.

6. Results

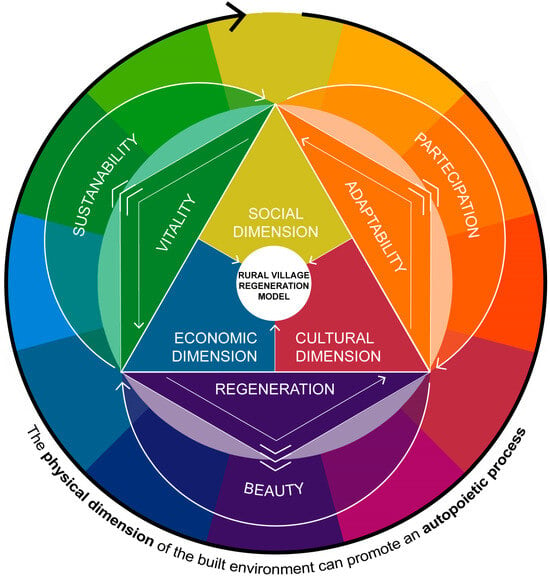

The outcomes of the elaborated sample is the ‘Rural Village Regeneration Model’ for the European rural village with a community-based approach, which is transferable to neighbourhoods in cities to implement the broader vision of circular settlement development.

The correspondence to common characteristics in each of the best practices examined through the different analyses and the alignment with the criteria has allowed us to trace dimensions that encompass virtuous actions of transformation of the built environment to be pursued.

The “Rural Village Regeneration Model” represents an operational tool for regional transformation, suitable for reactivating the lost connections between villages and larger cities in functional areas, characterised by greater self-sufficiency and exploring the potential of digital tools and bio-technology to improve services, connections, infrastructure, and cooperation.

The physical dimension of the built environment contributes to generate an autopoietic process in which the social, economic, and cultural dimensions can synergistically collaborate to identify an “ideal rural village”. The adaptability of the cultural dimension is closely linked to the participation of the social dimension in the processes of recovery and regeneration of the built environment. At the same time, such participation determines a vitality of the social dimension that has repercussions on the economic dimension, determining an extended and shared principle of sustainability. Finally, economic sustainability determines a regenerative push of the cultural dimension, determining a new form of shared beauty. In this circular arrangement, of biunivocal conditions, autopoiesis allows for the characterisation of the entire process of transformation of the tangible and intangible values of the built environment (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Rural Village Regeneration Model for the European rural village.

The ‘Rural Village Regeneration Model’ for the European rural village can be read according to three dimensions (Social, Economic, Cultural) contained in a fourth dimension which is the Physical. Each of the dimensions is structured into sub-components that describe the key factors for an appropriate regeneration process. The Social Dimension represents the heart of community regeneration, focusing on the well-being of the inhabitants and the active participation of local people, and in particular of the young population. The Economic Dimension represents the sustainability and economic growth of the rural village, referring to the viability and diversification of local production rooted in the area. The Cultural Dimension represents the preservation and promotion of the tangible and intangible heritage of rural village, as culture represents both a link to the past and an element of innovation and creativity for the future. Each dimension influences and shares the other through factors, respectively affecting themselves and the whole regeneration process. The ‘Rural Village Regeneration Model’ is based on a dynamic balance between the three dimensions Social, Economic, and Cultural that are intertwined, indicating that each cannot develop in isolation. The approach is holistic and each dimension is connected to the others through cyclical and dynamic processes, represented by the arrows within the model. Therefore, the Adaptivity of the Cultural Dimension and the Social Dimension, determines the Vitality of the latter dimension and of the Economic Dimension, which in turn, faces the Regeneration of itself and of the Economic Dimension, which by adapting itself retraces the circle. Respectively, Adaptivity refers to the ability of rural villageto respond flexibly and creatively to external changes, whether economic, social or environmental. This component emphasises the importance of being able to cope with new challenges, such as globalisation or climate change, without losing its identity. For a rural village, Adaptivity involves creating strategies that enable it to change its organisational structure, its social dynamics and its services, staying abreast of the times and keeping its identity alive. Vitality refers to the set of processes that serve to keep a rural village in fruition, ensuring that it is not abandoned or becomes stagnant. This concept refers to the ability of the rural village to generate economic opportunities that attract residents and visitors. To achieve this, it is necessary to develop local entrepreneurial activities that enhance their natural, craft, and cultural resources, promoting, for example, bio-economic productive activities, sustainable tourism activities, organic farming, and social enterprises. Economic vitality manifests itself in job creation, increased quality of life, and the attraction of new investment. Regeneration refers to the process of giving new life to existing traditions, spaces, and structures, adapting them to contemporary needs but without altering their identity. This concept implies an approach that is respectful towards the history and heritage of the rural village, but also innovative, capable of making traditions alive, and meaningful for new generations. Regeneration can include the recovery of ancient crafts, the promotion of cultural events, the restoration of monuments, and the use of public spaces for artistic or educational activities.

Adaptivity, Vitality, and Regeneration are connotative elements that are manifested in the relationship of different dimensions through respective factors of Participation, Sustainability, and Beauty. For example, social participation can stimulate new business ideas, increasing the economic vitality that allows the beauty of the rural village to be preserved, making it more attractive to tourists, and thus contributing to its cultural regeneration. The latter can, in turn, promote a greater sense of community, strengthening social participation.

In a circular perspective, then, Participation is manifested through the inclusion of inhabitants, and in particular of young ones in decisions concerning their local area. Strong participation means that people are not mere bystanders, but real protagonists of change. Through participatory processes (such as assemblies, forums, consultations), a sense of belonging and collective responsibility is stimulated [27,28,29]. The goal is to build a cohesive community that works together for the improvement of social and economic conditions in the rural village. Sustainability is manifested through the management of environmental resources and the ability to ensure long-term development without compromising the local ecosystem. This involves the responsible management of the natural, energy and productive resources, avoiding overexploitation and promoting a circular economy that reduces waste and negative environmental impacts in the rural village. A rural village that aims for sustainability promotes soil-friendly farming practices, encourages recycling, energy efficiency, and promotes a lifestyle that is in harmony with nature. Beauty manifests itself beyond aesthetics; it concerns the ability of the rural village to maintain and enhance its architectural and landscape features. Beauty is a key element not only in attracting visitors, but also in promoting pride of residents and improving their quality of life. In a regeneration process, beauty can be interpreted as attention to detail, respect for building traditions, rehabilitation of historic buildings, and preservation of landscape integrity. Beauty then becomes an engine of regeneration and a stimulus for attracting new economic and social opportunities. The whole process is developed in the context of an autopoietic one, involving the Physical Dimension of the Built Environment, that is, in the ability of the rural village to self-generate and maintain itself independently. This concept, borrowed from biology, refers to the ability of a system to regenerate itself and maintain its order structure independently. In the context of the rural village, this means that the built environment should be designed and managed in such a way that it continuously responds to the needs of the community, without having to depend solely on external resources. Autopoiesis, which implies energy self-sufficiency and resilience to external shocks, is grounded on the ability of built spaces to adapt to new social, economic, and environmental needs.

7. Discussion: The Innovative Advancement of the Rural Village Regeneration Model

Rural areas have been ‘left behind’ compared to the more dynamic urban metropolitan areas. In particular, the above-mentioned aspects means that young people have been ‘left behind’. The solemn promise repeated many times in Agenda 2030 not to leave “no one behind” has not been fulfilled. In substance, the attention has been focused on urban metropolitan areas. Here, there is an emphasis on the proposed development of rural areas based on the circular bio-economy model. Thus, the job perspective for young people is not only about leisure activities (of tourist reception-restaurants-bed and breakfast, etc.), but about the new opportunities resulting from the integration of the circular bio-economy, digital, and bio-technological innovations.

The “Rural Village Regeneration Model” towards taking care of young generations is grounded and inspired on nature organisation. It is a model characterised by symbiosis between people/inhabitants/community and with nature ecosystems. It suggests a circular agriculture organisation, in which all wastes are recycled/regenerated producing new resources/materials, and thus new jobs. In particular, the circular symbiotic ecosystem is shaped as a self-regenerative/autopoietic model. This autopoietic capacity mimics the self-organisational capacity of natural ecosystems, through which nature ecosystems adapt in time, remembering good and bad tentative adaptations and learning from them. This autopoietic capacity underlines that an organisation is achieved in nature through de-centralised models and self-management.

The above-mentioned model suggests the improvement of self-entrepreneurship, in particular of young inhabitants in villages, in agriculture, energy and recycled/regenerative productive sectors.

The “Rural Village Regeneration Model” advances current European policies by introducing a more dynamic and interconnected approach among the social, economic, and cultural dimensions, all “contained” within the physical dimension of the territory.

While the Urban Agenda focuses predominantly on urban governance, the “Rural Village Regeneration Model” emphasises the role of small towns and villages as key ac-tors in broader territorial regeneration. It suggests integrating urban and rural policies to foster a more cohesive and sustainable territorial balance. The Green Deal prioritises climate neutrality and ecological transition, but the “Rural Village Regeneration Model” advances this by integrating cultural and social dimensions. It ensures that sustainability measures do not lead to depopulation, but rather reinforce local identities and economies through sustainable tourism, renewable energy, and circular bio-economy initiatives. Traditionally focused on supporting farmers, the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) does not explicitly address the broader economic and social regeneration of rural areas. The model expands the scope of the CAP by fostering entrepreneurship in sustainable tourism, local craftsmanship, and social innovation, making agriculture a driver of holistic rural development [30]. While the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 and the United Nations 2030 Agenda focus on ecosystem protection, the “Rural Village Regeneration Model” advances them by integrating environmental sustainability with local economic and social resilience. It proposes practical applications such as energy-efficient renovations of historical buildings and agricultural practices that support biodiversity while boosting local economies. INTERREG facilitates cross-border cooperation, but the “Rural Village Regeneration Model” builds upon this by strengthening local village networks, creating economies not only of scales, but in particular economies coming from synergies and symbioses, and encouraging knowledge exchange between European rural communities to promote localised innovation [31]. Additionally, the Horizon Europe supports research and innovation, but the “Rural Village Regeneration Model” expands its application scope by emphasising the need for a multidisciplinary approach that merges technology, culture, and social development to create integrated solutions for rural revitalisation. In contrast to current policies that view participation primarily as a governance tool, the model considers it a catalyst for social and economic transformation. Active involvement in decision-making fosters a sense of belonging, encourages rural inhabitants to stay, and stimulates local capacity for self-generation. By adopting the “Rural Village Regeneration Model”, European institutions can ensure a holistic approach to rural regeneration, aligning with the strategies outlined in the European Urban Agenda, the European Green Deal, and EU territorial cohesion documents. This would strengthen the economic vitality, social cohesion, and cultural resilience of rural villages, ensuring balanced and sustainable development in the long term.

In particular, focusing on the European Network for Rural Development (ENRD) which provides a toolkit to assist policymakers and project managers in implementing high-speed networks in rural areas, addressing the digital divide and fostering economic opportunities [32], the research selected five main successful models to individuate how the ‘Rural Village Regeneration Model’ fills their lack. In contrast to the existing models, which focus on specific aspects of rural regeneration, this framework emphasises the interplay of multiple dimensions and their respective factors, forming a self-sustaining cycle of renewal.

The ‘Smart Villages’ model focuses primarily on leveraging digital technologies to enhance rural life [33]. While it provides essential tools for economic and social development, it lacks a structured integration with cultural and physical elements [34]. The “Rural Village Regeneration Model” advances this approach by embedding digital transformation within a broader framework that includes cultural preservation, economic sustainability, and participatory governance, ensuring that technology adoption aligns with the identity and heritage of the rural village rather than being an isolated intervention.

Integration of bio-technology innovation and digital innovations are proposed to meet young needs about first of all new jobs.

The ‘Heritage-Led Regeneration’ model [35], supported by the RURITAGE project [36], funded by the EU Horizon 2020 program, focuses on emphasising the preservation and promotion of tangible and intangible heritage. The model’s findings highlight that cultural heritage can drive economic vitality and social cohesion. However, its approach is primarily heritage-driven, which may not fully address the economic and social vitality required for long-term sustainability. The “Rural Village Regeneration Model” advances this by balancing heritage conservation with economic viability and social participation, ensuring that traditions evolve in ways that serve contemporary community needs rather than being solely preserved as static elements of the past.

The ‘Ecovillage’ model represents intentional communities designed to be socially, economically, and ecologically sustainable [37]. The Ecovillage model prioritises sus-tainability and ecological living, focusing on reducing the ecological footprint. While it offers a strong model for environmental consciousness, it often operates as self-contained communities rather than fully integrated rural settlements. The Rural Village Regeneration Model advances this by embedding sustainability within the broader economic, so-cial, and cultural dimensions, ensuring that ecological principles contribute to economic resilience and community vitality rather than functioning in isolation.

The ‘Rural’ model, supported by the RURALPLAN, addresses the challenges faced by shrinking rural areas, particularly in Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland [38]. By producing evidence on strategic planning, the project aims to develop innovative approach-es to rural regeneration. The model addresses the demographic decline in rural areas through strategic planning. However, its approach often remains reactive, responding to population shrinkage rather than proactively fostering self-sustaining regeneration. The “Rural Village Regeneration Model” advances this by emphasising adaptivity as a proactive component, enabling villages to anticipate and shape their future rather than merely responding to decline. By integrating economic, social, and cultural resilience, the “Rural Village Regeneration Model” ensures that rural villages remain attractive and functional even in the face of demographic challenges.

The “Community-Led” model [39] supports the grassroots efforts, such as those observed in the Greek village of Fourna, demonstrating the impact of community-led initiatives on rural regeneration. Local residents have successfully attracted new families to the village, revitalising the community and enhancing social participation. However, their effectiveness often depends on informal networks and individual leadership rather than structured governance models. The “Rural Village Regeneration Model” advances this by formalising participation through institutionalised decision-making processes. It ensures that local communities and in particular young people are active protagonists of change within a structured framework that guarantees long-term sustainability and social cohesion. Left behind areas are required to move beyond the mainstream economics that have led young generations to fall behind and spiral down. This requires new bio-economy circular models in development strategies. Specific indicators about quality of life perception and the health of young people are needed.

8. Conclusions

The ‘Rural Village Regeneration Model’ integrates the different dimensions of the built environment according to a holistic approach that can promote a balance between rural community development and land conservation. Through active participation of inhabitants, economic sustainability and cultural regeneration, the rural village becomes an active hub of sustainable innovation, capable of contributing to the achievement of European goals on ecological transition [40,41]. The European Urban Agenda aims to promote smart, sustainable, and inclusive cities. Integrating the “Rural Village Regeneration Model” into the rural context allows these goals to be extended to less urbanised and marginalised areas, ensuring that not only large cities but also small rural villages can actively participate in ecological transition processes. The economic dimension of the model promotes the responsible management of natural resources and encourages practices such as sustainable circular agriculture and the use of renewable energy. This helps reduce environmental impacts, making rural areas pillars in the fight against climate change. The social dimension of the model, with emphasis on participation and adaptability, aligns with the principles of social inclusion promoted by the European Urban Agenda, ensuring that rural communities and their young inhabitants are not marginalised but play a central role in decision-making and adaptation to environmental change. The enhancement of cultural heritage and the beauty of the landscape are not only elements of local identity, but also have become factors of sustainable tourism attractiveness, stimulating a local economy that respects the environment and offers opportunities for young people and innovative businesses [42,43,44].

Rural villages, often overlooked in traditional development plans, can instead be central to the ecological transition. Through a combination of sustainable agricultural practices, small-scale renewable energy production and judicious land management, these places become true laboratories of green innovation. The “Rural Village Regeneration Model” represented fosters a gradual but decisive transition to a circular and low-emission economy, with the rural village as the epicentre of change as the tool to support the development of a Rural Action Plan, aimed at enhancing the role of inland areas and villages in achieving European ecological goals. This vision ensures that rural villages also contribute decisively to the ecological transition, promoting sustainable, participatory, and resilient development that supports both the European Urban Agenda and the broader goals of the Green Deal. Rural villages and the communities that inhabit them thus become protagonists in a regeneration process that not only preserves their identity, but makes them vital centres of innovation and sustainability for the Europe of the future [43].

On these bases, a rural action plan should be developed that proposes a specific priority of actions in time and space.

A strategy of actions to form a Rural Action Plan is required to integrate these perspectives towards the European Urban Agenda, in order to enable inland areas and small rural villages that contribute to the overall ecological transition process.

It is important to emphasise that a Rural Action Plan should consider above all the inclusion of young people who today leave rural villages due to the lack of services necessary for their personal and professional growth. Therefore, policies for the regeneration of rural villages should be centered on young people and the future generations for whom the sustainability strategy was developed.

In this perspective, the assessment of the ‘Youth Progress Index (YPI)’ for defining such projects is fundamental, because it enables public institutions and civil society organisations to prioritise the most urgent needs of young people living in rural villages [44].

The “Youth Progress Index” is a tool that measures the well-being and perceived quality of life of young people by monitoring various aspects of their lives in various countries [44]. The index was created to provide an overview of the conditions in which young people live, assessing how well they are able to reach their full potential, from a series of indicators covering various aspects of their lives. One of the main aspects that is analysed is education. In fact, the YPI measures access to education and the quality of the education system, while also taking into consideration the learning opportunities that young people have available to them. Alongside education, employment and economic opportunities are another fundamental element. The index assesses not only employment opportunities for young people, but also youth unemployment and access to training and career opportunities.

Another important aspect that is considered is the health and well-being of young people, which includes both physical and mental health. In this context, access to health services and general factors affecting well-being are taken into account. In addition, the YPI measures young people’s level of social participation by looking at how involved they are in social and political activities, and how successful they are in participating in their community’s decisions to ensure effective inclusion in social dynamics. Finally, the index assesses the physical and psychological safety of young people, seeking to understand how protected they are from risks such as violence, abuse, or other threats to their safety.

These indicators, taken together, provide an overall view of a youth-centered development strategy and help identify areas where there may be gaps or difficulties so that actions can be taken to improve their living conditions.

Thus, the Youth Progress Index assessment can be useful in guiding rural regeneration projects, as it provides hard data and key indicators that enable a better understanding of young people’s needs, identify areas where action is needed, and design initiatives that promote their well-being, access to educational and employment opportunities, and their active participation in the social and economic life of rural communities.

In this perspective, the compass evaluation method (analysed in Section 5.1) should be supported and accompanied by a strong process of involving the affected population in rural village development projects, through the activation of real Living Labs. Therefore, the subjects participating in such initiatives should not only be the elderly who populate the villages but also the young people, in order to identify their needs and guide strategic choices, based on the “magic triangle” between environmental quality, people’s health, and plant health [45].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.C.; methodology, F.C., M.A. and L.F.G.; validation, G.M., M.A. and F.C.; formal analysis, F.C., M.A. and G.M.; investigation, F.C., M.A. and G.M.; resources, M.A.; data curation, F.C., M.A. and G.M.; writing—original draft preparation, F.C. and G.M.; writing—review and editing, F.C., M.A. and G.M.; visualization, G.M.; supervision, L.F.G.; funding acquisition, M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Italian Ministry of University and Research (MUR), in the context of the Projects of Relevant National Interest—National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PRIN PNRR). Project Title: Italian historic regeneration through circular ecological heritage communities. Grant Number B53D23029490001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; United Nations COP28: Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Empowering Citizens in Shaping Europe’s Energy Future; EU Publish: Brussels, Belgium, 2024; Available online: https://euagenda.eu/publications/empowering-citizens-to-shape-the-future-of-energy (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- European Parliament. Towards an Integrated Approach to Cultural Heritage for Europe; Representation: Chicago, IL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Adapting When the Climate Crisis Hits Close to Home. Available online: https://climate.ec.europa.eu/news-your-voice/news/adapting-when-climate-crisis-hits-close-home-2023-08-01_en (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- World Economic Forum: How 3 Cities Are Transforming to Adapt to Climate Change. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/07 (accessed on 12 February 2024).

- Local Governments for Sustainability (ICLEI). Bauhaus Euroace Villages for the Future. New European Bauhaus PampilhosaProject. 2023. Available online: https://iclei-europe.org/news/?Newly_signed_protocol (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- Ciampa, F. Processi ibridi: L”integrazione tecnologica come attante del progetto d”architettura. TECHNE 2021, 21, 249–255. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society (Faro Convention). 2005. Available online: www.conventions.coe.int (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- UNESCO. Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape, UNESCO World Heritage Centre, Resolution 36C/23, Annex, 2011. Available online: www.unesco.org (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- UCLG. Culture 21: Actions. Commitments on the Role of Culture in Sustainable Cities. 2015. Available online: www.agenda21culture.net/ (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Angrisano, M.; Nocca, F.; Scotto di Santolo, A. Multidimensional Evaluation Framework for Assessing Cultural Heritage Adaptive Reuse Projects: The Case of the Seminary in Sant’Agata de’Goti (Italy). Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Vision About Rural Areas. Available online: https://rural-vision.europa.eu/maps-data (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Growth Within: A Circular Economy Vision for a Competitive Europe; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Isle of Wight, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Cork 2.0 Declaration 2016, a Better Life in Rural Areas; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/enrd/sites/default/files/cork-declaration_en.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Huang, Y.; Li, E. Culture heritage utilization evaluation of historic villages: 10 cases in the Guangzhou and Foshan Area, Guangdong Province, China. J. Asian Arch. Build. Eng. 2023, 2994, 22–3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission: Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development; Ocsko, E. Preparatory Action—Smart Rural Areas in the 21st Century—Final Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2762/493890 (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: New European Bauhaus: Beautiful, Sustainable, Together (COM/2021/573 Final). 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM:2021:573:FIN (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Fusco Girard, L.; Vecco, M. The “Intrinsic Value” of Cultural Heritage as Driver for Circular Human-Centered Adaptive Reuse. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco Girard, L.; Nijkamp, P. Le valutazioni per lo Sviluppo Sostenibile della Città e del Territorio; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. EU Action for Smart Villages; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/enrd/ (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Arup. Rigenerare i Borghi Europei: Una Visione per Tornare nelle aree Rurali; Arup: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]