Development of Eco-Schemes as an Important Environmental Measure in Areas Facing Natural or Other Specific Constraints Under the Common Agriculture Policy 2023–2027: Evidence from Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Background

2.1. The Importance of ANCs in the EU: Theoretical Approach

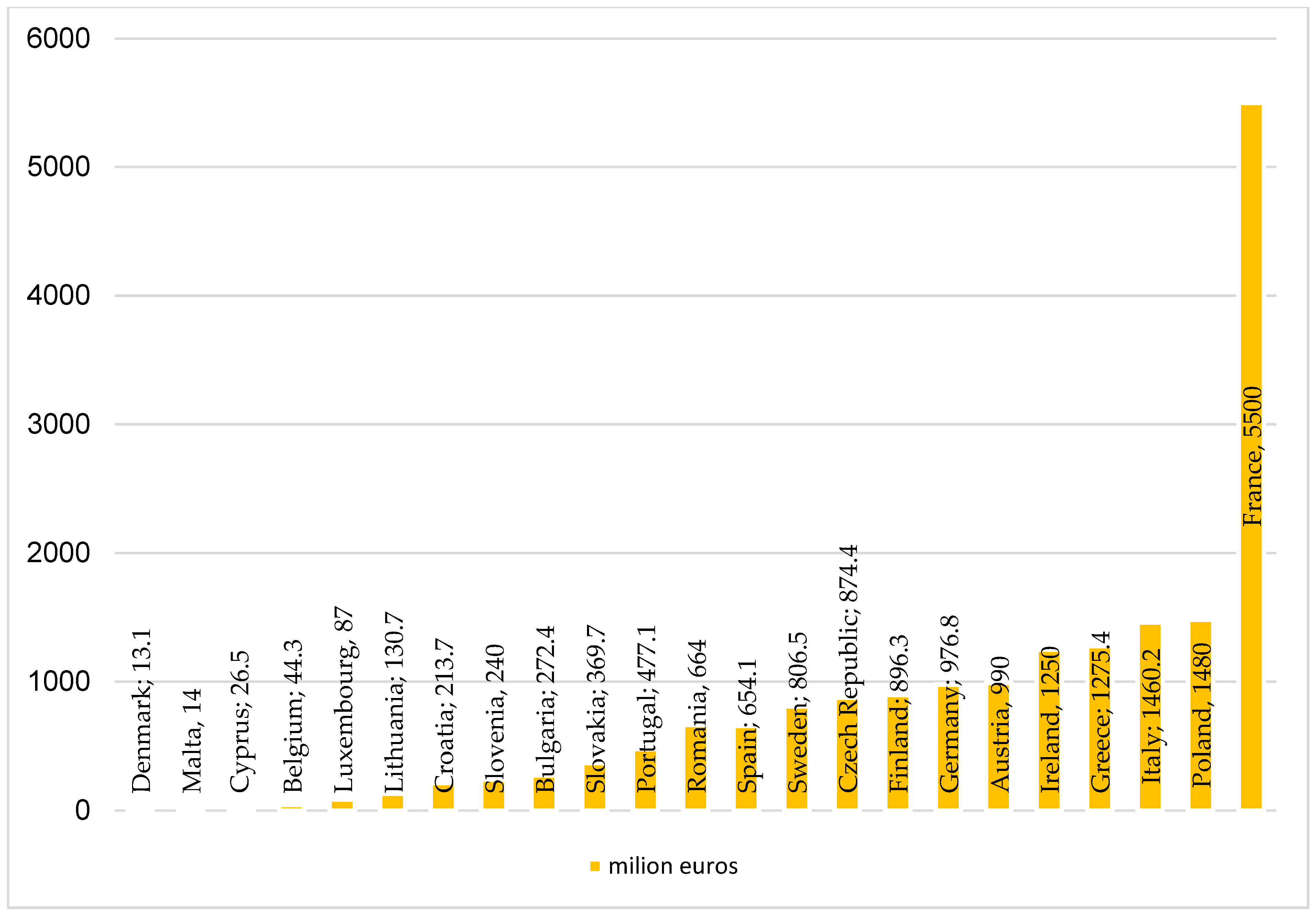

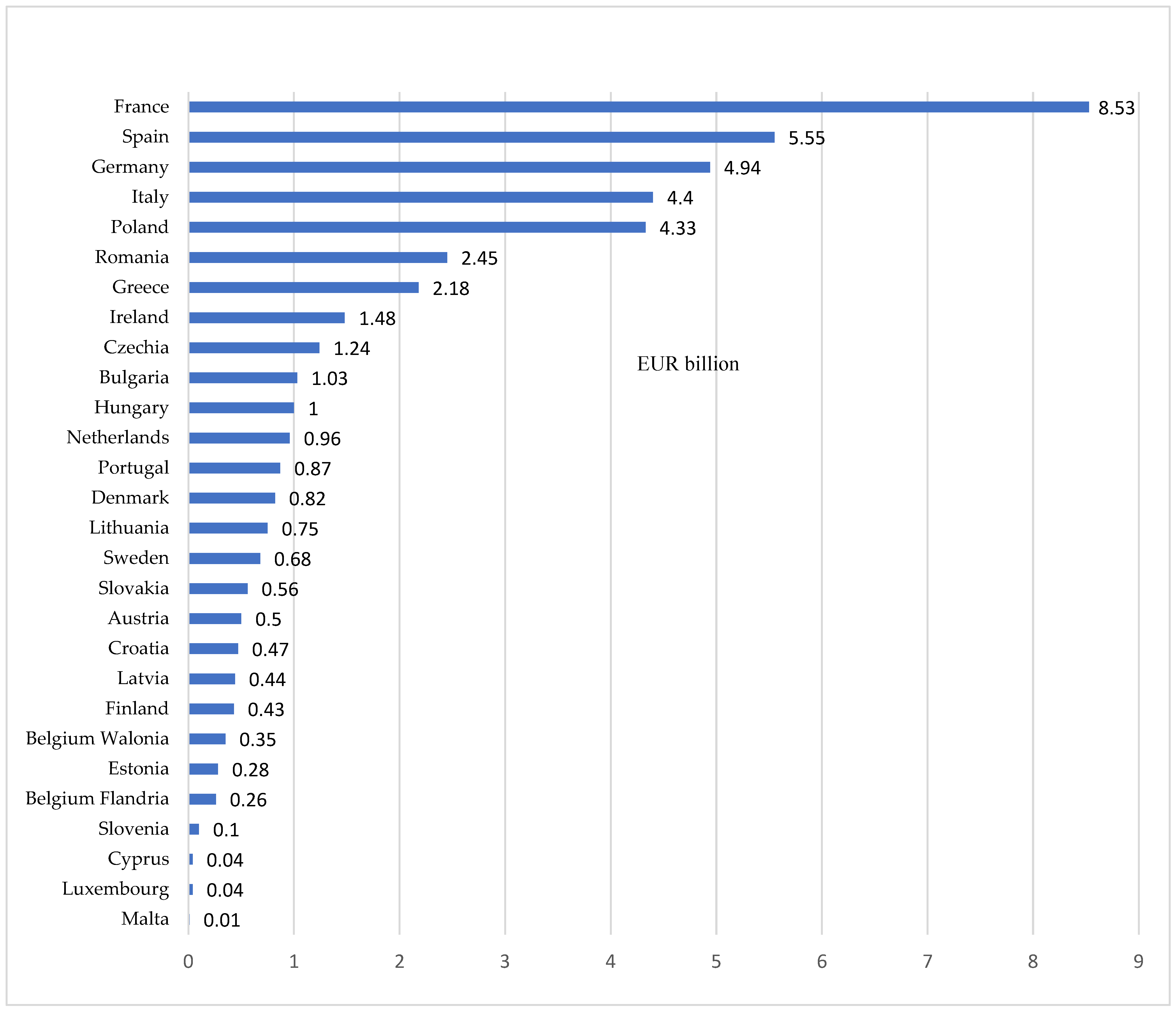

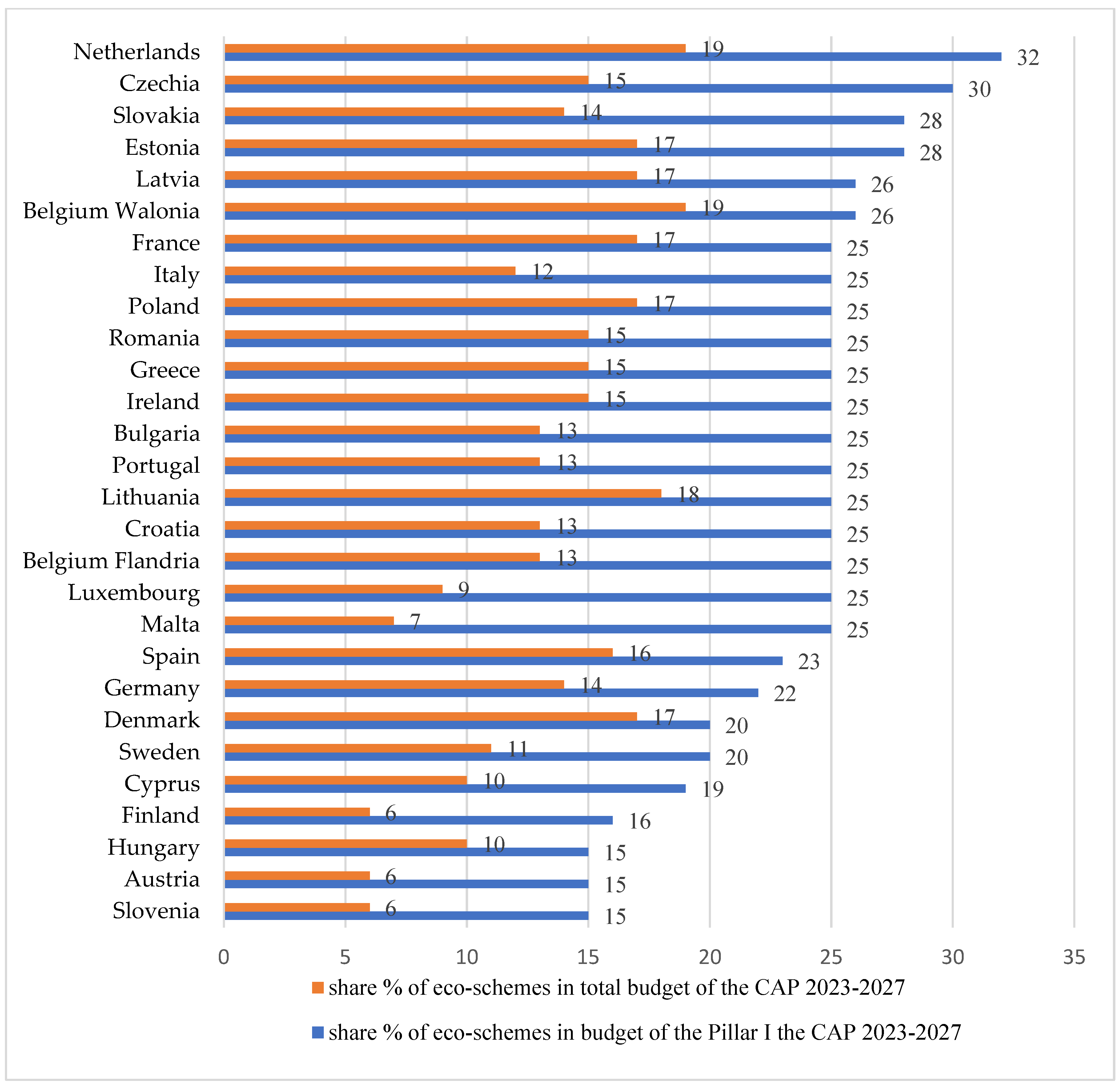

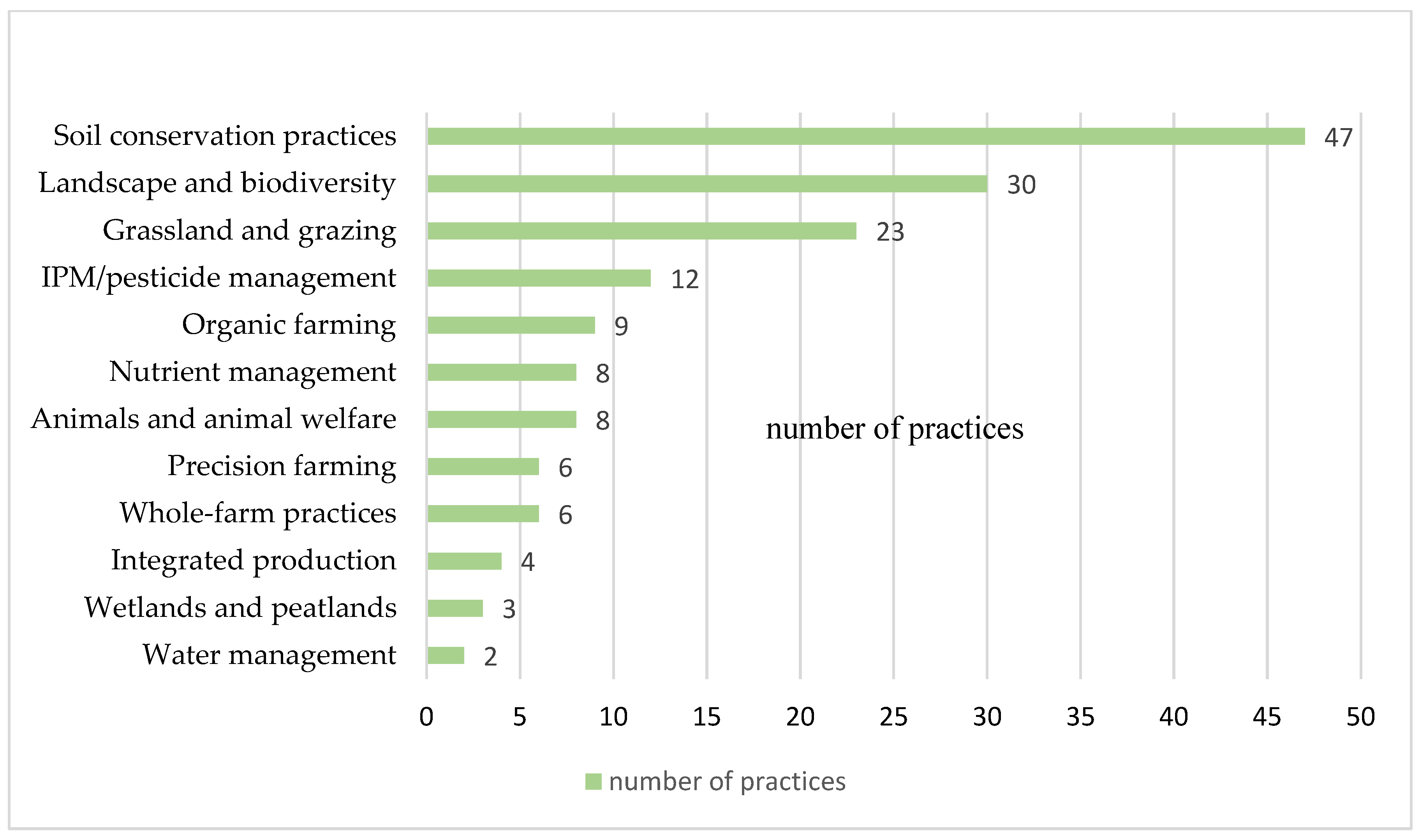

2.2. Eco-Schemes as an Important Environmental Measure Under the CAP 2023–2027

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Methodsc

4. Results

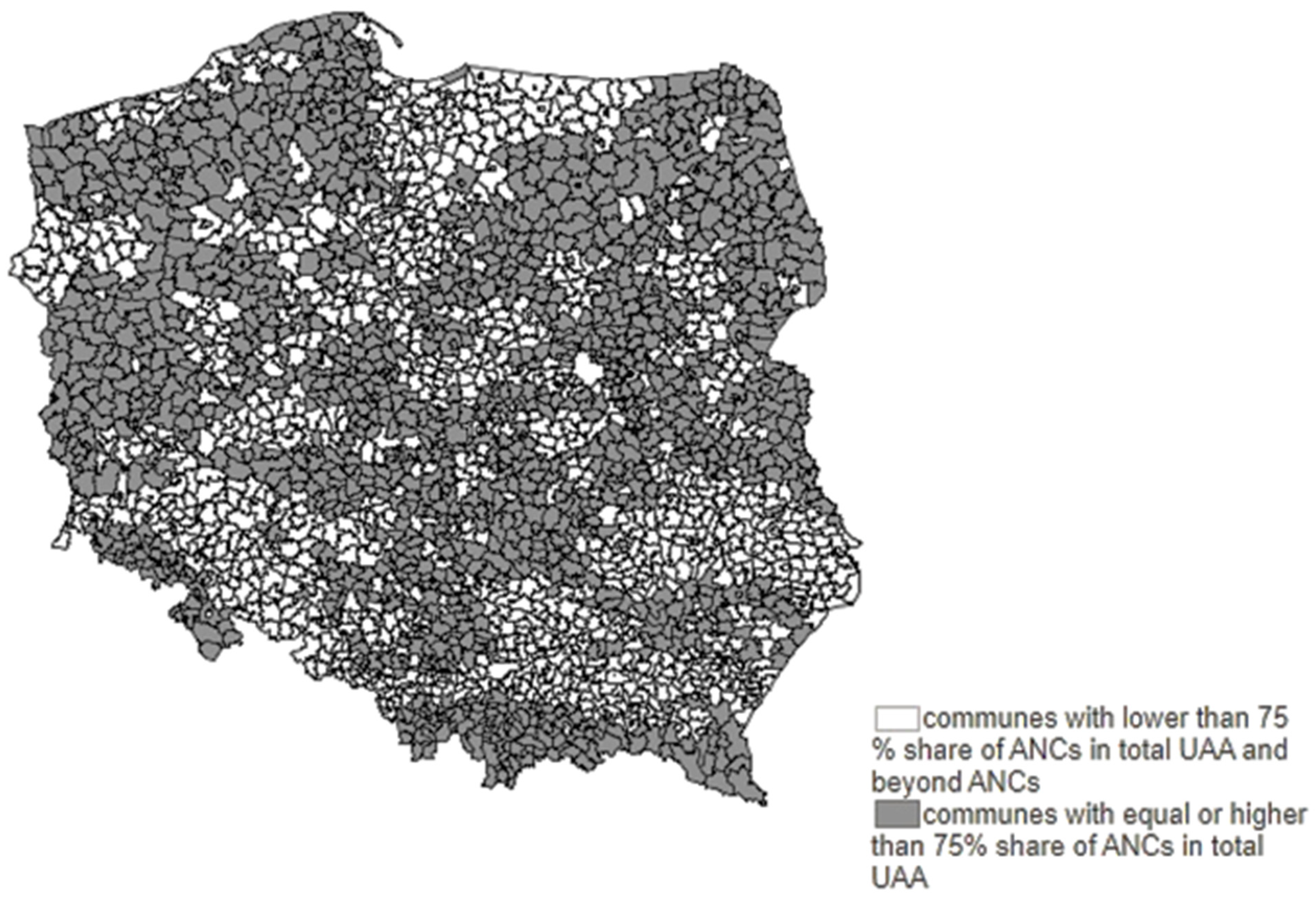

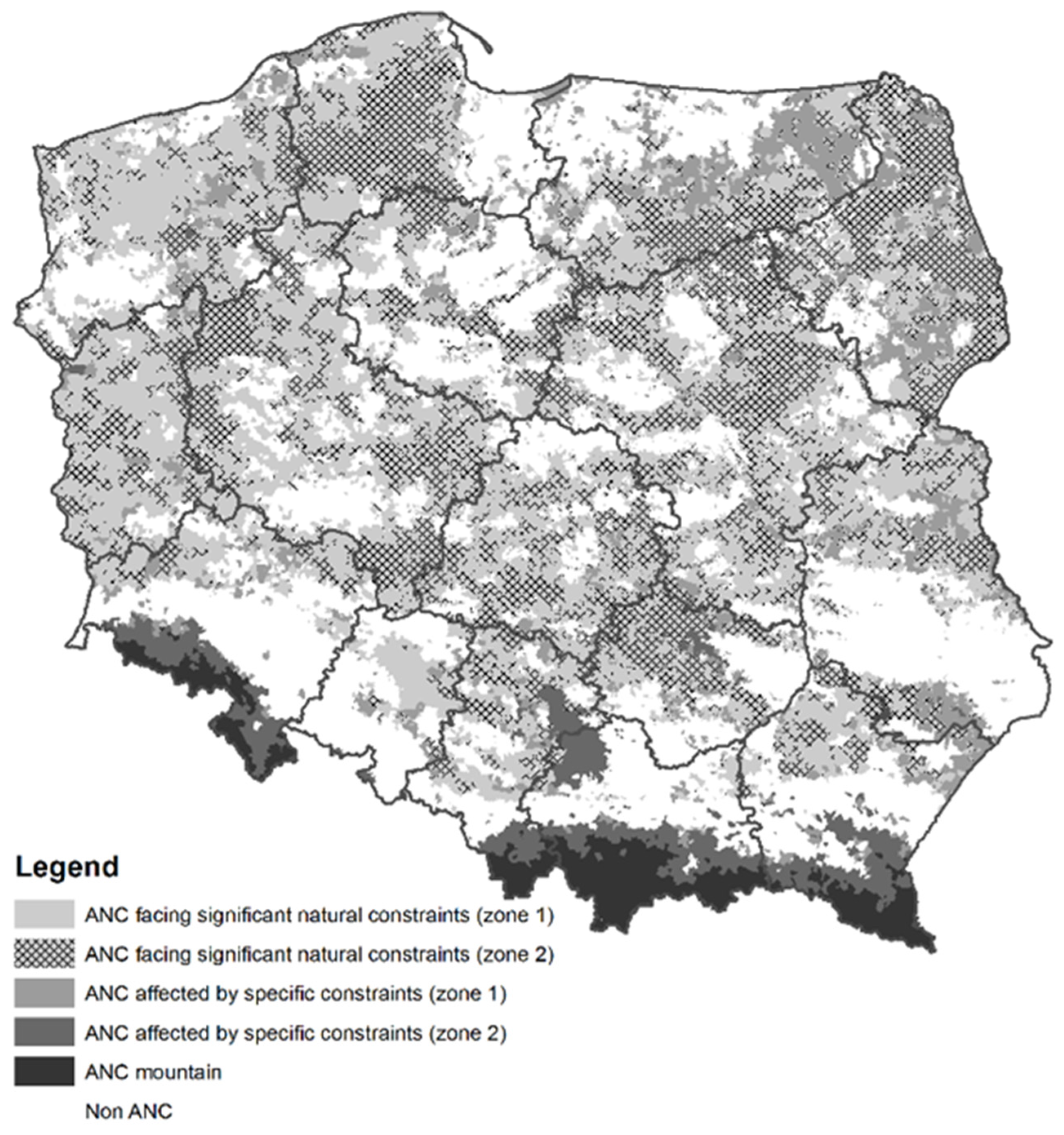

4.1. State of ANCs in Poland

4.2. State of Agriculture in Poland, Including ANCs Areas and the Role of Eco-Schemes

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. The European Green Deal. COM(2019) 640 Final. 2019. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2019%3A640%3AFIN (accessed on 2 June 2024).

- The State of the World’s Land and Water Resources for Food and Agriculture 2021. Main Report. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Rome. 2022. Available online: https://www.fao.org/land-water/solaw2021/en/ (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- European Commisssion (2021). Communication from The Commission to the European Parliament, The European Council, The Council, The European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, EU Soil Strategy for 2030. Reaping the Benefits of Healthy Soils for People, Food, Nature and Climate. COM(2021) 699 Final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A52021DC0699 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- European Commission. Mapping and Assessment of Ecosystems and their Services: An EU Ecosystem Assessment. JRC Science for Policy Report. 2020. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/afac1162-0f58-11eb-bc07-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 8 December 2024).

- European Environment Agency. The European Environment-State and Outlook 2020. Knowledge for Transition to a Sustainable Europe. 2019. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/soer/2020 (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- European Court of Auditors. Combating Desertification in the EU: A Growing Threat in Need of More Action. 2018. Available online: https://www.eca.europa.eu/en/publications?did=48393 (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Arias-Navarro, C.; Baritz, R.; Jones, A. The State of Soils in Europe. Publications Office of the European Union. 2024. JRC137600. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/1f96158b-901f-11ef-a130-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Van der Zanden, E.; Verburg, P.H.; Schulp, C.J.E.; Verkerk, P.J. Trade-offs of European agricultural abandonment. Land Use Policy 2017, 62, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EEA 2019 Land and soils in Europe. EEA Signals. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0264837716314417 (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Zgłobicki, W.; Karczmarczuk, K.; Baran-Zgłobicka, B. Intensity and Driving Forces of Land Abandonment in Eastern Poland. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission (EC). CAP Context Indicators—2021 Update. 2021. Available online: https://agridata.ec.europa.eu/extensions/DataPortal/context_indicators.html (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Zimmermann, A.; Britz, W. European farm participation in agri-environmental measures. Land Use Policy 2016, 50, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieliński, M.; Jadczyszyn, J. Importance and challenges for agriculture from High Nature Value farmlands (HNVf) in Poland in the context of the provision of public goods under the European Green Deal. Econ. Environ. Econ. Environ. 2022, 3, 194–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarolli, P.; Straffelini, E. Agriculture in Hilly and Mountainous Landscapes: Threats, Monitoring and Sustainable Management. Geogr. Sustain. 2020, 1, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, T.; Baldock, D.; Rayment, M.; Kuhmonen, T.; Terluin, I.; Swales, V.; Poux, X.; Zakeossian, D.; Farmer, M. An Evaluation of the Less Favoured Area Measure in the 25 Member States of the European Union; Institute for European Environmental Policy: Brussels, Belgium, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cagliero, R.; Vassallo, M.; Pierangeli, F.; Pupo D’Andrea, M.R.; Monteleone, A.; Camaioni, B.; Tarangioli, S. The Common Agricultural Policy 2023–2027: How Member States Implement the New Delivery Model? Ital. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2023, 78, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament 2023. European Parliamentary Research Service. Guide to EU Funding 2023 edition. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_STU(2023)747110 (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- European Commission. Approved 28 CAP Strategic Plans (2023–2027). 2023. Available online: https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/document/download/7b3a0485-c335-4e1b-a53a-9fe3733ca48f_en?filename=approved-28-cap-strategic-plans-2023-27.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Official Journal of the European Union. Regulation (EU) 2021/2115 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 2 December 2021 Establishing Rules on Support for Strategic Plans to be Drawn up by Member States Under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP Strategic Plans) and Financed by the European Agricultural Guarantee Fund (EAGF) and by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) and Repealing Regulations (EU) No 1305/2013 and (EU) No 1307/2013. 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32021R2115 (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Feindt, P.; Grohmann, P.; Hager, A. The CAP post-2020 reform and the EU budget process. In EU Policymaking at a Crossroads. Negotiating the 2021–2027 Budget; Munch, S., Heinelt, H., Eds.; Edward Edgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Diaz, F.J.; Belmonte-Urena, L.J.; Alvarez-Rodriguez, J.F.; Cachao-Ferre, F. The Role of Sustainability and Circural Economy in Europe’s Common Agricultural Policy. In Environmentally Sustainable Production. Research for Sustainable Development; Valls Martinez, M.A., Santos-Jaen, J.M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. List of Potential Agricultural Practices that Eco-Schemes Could Support; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Latacz-Lohmann, U.; Termansen, M.; Nguyen, C. The New Eco-Schemes: Navigating a Narrow Fairway, EuroChoices; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; Volume 21, pp. 4–10. ISSN 1746-692X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pe’er, G.; Bonn, A.; Bruelheide, H.; Dieker, P.; Eisenhauer, N.; Feindt, P.; Hagedorn, G.; Hansurgens, B.; Herzon, I.; Lomba, A.; et al. Action needed for the EU Common Agricultural Policy to address sustainability challenges. People Nat. 2020, 2, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pe’er, G.; Finn, J.A.; Diaz, M.; Brikenstock, M.; Lakner, S.; Röder, N. How can the European Common Agricultural Policy helphalt biodiversity loss? Recommendations by over 300 experts. Conserv. Lett. 2022, 15, e12901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlavsa, T.; Spicka, J.; Stolbova, M.; Hlouskova, Z. Statistical analysis of economic viability of farms operating in Czech areas facing natural constraints. Agric. Econ. 2020, 66, 193–202. [Google Scholar]

- Communication from The Commission to the European Parliament, The European Council, The Council, The European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030. Bringing Nature Back into our Lives. COM (2020) 380 Final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A52020DC0380 (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Communication from The Commission to the European Parliament, The European Council, The Council, The European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. A Farm to Fork Strategy for a Fair, Healthy and Environmentally-Friendly Food System. COM (2020) 381 Final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A52020DC0381 (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Forging a Climate—Resilient Europe_the New EU Strategy on Adaptation to Climate Change, COM (2021) 82 Final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2021%3A82%3AFIN (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Papić, R. Rural development policy on areas with natural constraints in the Republic of Serbia. Ekon. Poljopr. 2022, 69, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clough, Y.; Kirchweger, S.; Kantelhardt, J. Field sizes and the future of farmland biodiversity in European landscapes. 2020. Available online: https://conbio.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/conl.12752 (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- Kazakova-Mateva, Y. Effects of Less Favoured Areas support in territories with natural constraints. Trakia J. Sci. 2017, 15, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plieninger, T.; Gaertner, M.; Hui, C.; Huntsinger, L. Does land abandonment decrease species richness and abundance of plants and animals in Mediterranean pastures, arable lands and permanent croplands? Environ. Evid. 2013, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoate, C.; Baldi, A.; Beja, P.; Boatman, N.D.; Herzon, I.; van Doorn, A.; de Snoo, G.R.; Rakosy, L.; Ramwell, C. Ecological impacts of early 21st century agricultural change in Europe—A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 91, 22–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redlichova, E.; Blažková, I.; Chmelíková, G.; Vinohradský, K. Links between farm size, location and productivity of farms in the Czech Republic. Eur. Countrys. 2023, 15, 508–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieliński, M.; Jadczyszyn, J.; Sobierajewska, J. Predispositions and challenges of agriculture from areas particularly facing natural or other specific constraints in Poland in the context of providing environmental public goods under EU policy. Agric. Econ. 2023, 69, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wąs, A.; Malak-Rawlikowska, A.; Zavalloni, M.; Viaggi, D.; Kobus, P.; Sulewski, P. In search of factors determining the participation of farmers in agri-environmental schemes—Does only money matter in Poland? Land Use Policy 2021, 101, 105190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission (EC). Areas with Natural Constraints. Overview and Socio-Economic and Environmental Features of Farming in ANC Areas Based on FADN Data. 2023. Available online: https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/document/download/586ba067-4ce9-4afe-8139-719253ed0f45_en?filename=analytical-brief-1-anc-brief_en.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Meredith, S.; Hart, K. CAP 2021–2027: Using the Eco-Scheme to Maximise Environmental and Climate Benefits. 2019. Available online: https://www.organicseurope.bio/content/uploads/2020/06/ifoam_eu_eco-scheme_report_final.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Lampkin, N.; Stolze, M.; Meredith, S.; de Porras, M.; Haller, L.; Mészáros, D. Using Eco-Schemes in the New CAP: A Guide for Managing Authorities. 2020. Available online: https://www.organicseurope.bio/content/uploads/2020/06/ifoam-eco-schemes-web_compressed-1.pdf?dd (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- Pilvere, I.; Nipers, A.; Pilvere, A. Evaluation of the European Green Deal Policy in the Context of Agricultural Support Payments in Latvia. Agriculture 2022, 12, 2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donham, J.; Wezel, A.; Migliorini, P. Improving Eco-Schemes in the Lighnt of Agroecology. AE4EU. 2022. Available online: https://www.agroecology-europe.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Improving-eco-schemes-in-the-light-of-agroecology-Policy-Brief-Feb-2022-AE4EU.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Tataridas, A.; Kanatas, P.; Chatzigeorgiou, A.; Zannopoulos, S.; Travlos, I. Sustainable Crop and Weed Management in the Era of the EU Green Deal: A Survival Guide. Agronomy 2022, 12, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarvia, F.; Xausa, E.; De Petris, S.; Cantamessa, G.; Borgogno-Mondino, E.A. Possible Role of Copernicus Sentinel-2 Data to Support Common Agricultural Policy Controls in Agriculture. Agronomy 2021, 11, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieliński, M.; Koza, P.; Łopatka, A. Agriculture from Areas Facing Natural or Other Specific Constraints (ANCs) in Poland, Its Characteristics, Directions of Changes and Challenges in the Context of the European Green Deal. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Józwiak, W.; Sobierajewska, J.; Zieliński, M.; Ziętara, W. The Level of Labour Profitability and Development Opportunities of Farms in Poland. Probl. Agric. Econ. 2019, 2, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieliński, M.; Gołebiewska, B.; Adamski, M.; Sobierajewska, J.; Tyburski, J. Adaptation of eco-schemes to Polish agriculture in the first year of the EU CAP 2023–2027. Econ. Environ. 2024, 89, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://eu-cap-network.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/publications/2024-01/report-1-tg-ecoschemes.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Weber, T.M. Eco-schemes—First Year of Implementation in Austria and First Experiences. 2023. Available online: https://cld.pt/dl/download/2bc028bf-20e0-4a95-87a1-51afbfc96107/23jun06CI-RegimesEcol%C3%B3gicos_nos_EstadosMembros/Eco-schemes_LKO_%C3%81ustria-Thomas%20Weber.pdf?download=true (accessed on 29 December 2024).

- Panagos, P.; Borrelli, P.; Poesen, J.; Ballabio, C.; Lugato, E.; Meusburger, K.; Montanarella, L.; Alewell, C. A new assessment of soil loss from water erosion in Europe. Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 54, 438–447. [Google Scholar]

- Cerdà, A.; Rodrigo-Comino, J.; Novara, A.; Brevik, E.C.; Vaezi, A.R.; Pulido, M.; Giménez-Morera, A.; Keesstra, S.D. Long-term effects of precipitation-induced agricultural land abandonment on soil erosion in the western Mediterranean basin. Prog. Phys. Geogr. Earth Environ. 2018, 42, 202–219. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, D.; Kar, S.K.; Chattopadhyay, A.; Shikha, A.; Rakshit, A.; Tripathi, V.K.; Dubey, P.K.; Abhilash, P.C. Sustainable low input agriculture: A viable climate smart option for increasing food production in a warming world. Ecol. Ind. 2020, 115, 106412. [Google Scholar]

- Pijl, A.; Reuter, L.E.H.; Quarella, E.; Vogel, T.A.; Tarolli, P. GIS-based soil erosion modelling in different viticulture practices on steep slopes. Catena 2020, 193, 104604. [Google Scholar]

- Schütte, E.; Plaas, J.A.; Gómez, G.G. Cost-effectiveness of erosion control with cover crops in European vineyards considering environmental costs. Environ. Dev. 2020, 35, 100521. [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke, E.; Kramm, N. High Nature Value (HNV) farming and the management of upland diversity. A review. Eur. Countrys. 2012, 2, 116–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, M.; Concepción, E.D. Enhancing the effectiveness of CAP greening as a conservation tool: A call for regional targeting with landscape constraints. Curr. Landsc. Ecol. Rep. 2016, 1, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatto, P.; Mozzato, D.; Defrancesco, E. Analysis of the role of factors influencing farmers‘ decision to continue agri-environmental programmes from a temporal perspective. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 92, 237–244. [Google Scholar]

- Tyllianakis, E.; Martin-Ortega, J. Agri-environmental programmes for biodiversity and conservation: Why we are still not “hitting the right buttons”. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duer, I. Agri-environmental programmes as an instrument for environmental resources protection in the Common Agricultural Policy of the European Union. Studies & Reports IUNG-PIB. Available online: https://bc.iung.pl/server/api/core/bitstreams/86fe31ca-f698-4f3b-a677-379a2c19cc49/content (accessed on 29 December 2024).

- Hadyńska, A.; Hadyński, J. Directions and prospects for the development of agri-environmental programmes in the EU, Annals of the Polish Association of Agricultural and Agribusiness Economists 2005. Available online: https://bazekon.uek.krakow.pl/rekord/101464031 (accessed on 29 December 2024).

- Kruszyński, M. Pro-environmental measures as an instrument of the Common Agricultural Policy of the European Union. Agric. Advis. Issues 2023, 4, 26–39. [Google Scholar]

- Lovec, M.; Šumrada, T.; Erjavec, E. New CAP Delivery Model, Old Issues. Intereconomics 2020, 55, 112–119. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, A.; Lopez-Bao, V.J. EU Agricultural Policy Still Not Green. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 990. [Google Scholar]

- Pe’er, G.; Zinngrebe, Y.; Moreira, F.; Sirami, C.; Schindler, S.; Müller, R.; Bontzorlos, V.; Clough, D.; Bezak, P.; Lakner, S.A. Greener Path for the EU Common Agricultural Policy. Science 2019, 365, 449–451. [Google Scholar]

- Scown, M.; Brady, M.V.; Nicholas, A.K. Billions in Misspent EU Agricultural Subsidies Could Support the Sustainable Development Goals. One Earth 2020, 3, 137–150. [Google Scholar]

- Galli, F.; Prosperi, P.; Favilli, E.; D’Amico, S.; Bartolini, F.; Brunori, G. How Can Policy Processes Remove Barriers to Sustainable Food Systems in Europe? Contributing to a Policy Framework for Agri-Food Transitions. Food Policy 2020, 96, 101871. [Google Scholar]

- Kugelberg, S.; Bartolini, F.; Kanter, R.D.; Milford, B.A.; Pira, K.; Sanz-Cobena, A.; Leip, A. Implications of a Food System Approach for Policy Agenda Setting Design. Glob. Food Secur. 2021, 28, 100451. [Google Scholar]

- Recanati, F.; Maughan, C.; Pedrotti, M.; Dembska, K.; Antonelli, M. Assessing the Role of CAP for more Sustainable and Healthier Food Systems in Europe: A Literature Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 653, 908–919. [Google Scholar]

- Bonfiglio, A.; Arzeni, A.; Bodini, A. Assessing the eco-efficiency of farms in rural areas. Agric. Syst. V 2017, 151, 114–125. [Google Scholar]

- Picazo-Tadeo, A.; Beltrán-Esteve, M.; Gómez-Limón, J. Evaluation of ecological effectiveness using directional distance functions. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2012, 220, 798–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadanakis, Y.; Bennett, R.; Park, J.; Areal, F. Evaluating the sustainable intensification of arable farms. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 150, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czyżewski, B.; Trojanek, R.; Dzikuć, M.; Czyżewski, A. Cost-effectiveness of the common agricultural policy and environmental policy in country districts: Spatial spillovers effects of pollution, bio-uniformity and green schemes in Poland. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 138254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Chen, X.; Jiao, Y. Sustainable Agriculture: Theories, Methods, Practices and Policies. Agriculture 2024, 14, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, S.; Zolotnytska, Y. Sustainability of agriculture and rural areas in regional terms. Econ. Environ. 2024, 89, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinowska, B.; Bórawski, P.; Bełdycka-Bórawska, A.; Klepacki, B.; Perkowska, A.; Rokicki, T. Sustainable Development of Agriculture in Member States of the European Union. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guth, M.; Smędzik-Ambroży, K.; Czyżewski, B.; Stępień, S. The Economic Sustainability of Farms under Common Agricultural Policy in the European Union Countries. Agriculture 2020, 10, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hloušková, Z.; Lekešová, M.; Prajerová, A.; Doucha, T. Assessing the Economic Viability of Agricultural Holdings with the Inclusion of Opportunity Costs. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragosta, M.; Daniele, G.; Imbrenda, V.; Coluzzi, R.; D’Emilio, M.; Lanfredi, M.; Matarazzo, N. Land Transformations in Irpinia (Southern Italy): A Tale on the Socio-Economic Dynamics Acting in a Marginal Area of the Mediterranean Europe. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soulis, K.X.; Kalivas, D.P.; Apostolopoulos, C. Delimitation of Agricultural Areas with Natural Constraints in Greece: Assessment of the Dryness Climatic Criterion Using Geostatistics. Agronomy 2018, 8, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klima, K.; Kliszcz, A.; Puła, J.; Lepiarczyk, A. Yield and Profitability of Crop Production in Mountain Less Favoured Areas. Agronomy 2020, 10, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The State of Soils in Europe. Fully Evidenced, Spatially Organised Assessment of the Pressures Driving Soil Degradation. 2024. European Comission, Eu-ropean Environmental Agency. Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC137600 (accessed on 3 January 2025).

| ANCs with Natural Constraints | ANCs with Specific Constraints | Mountain ANCs | Total Share of ANCs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EU-27 | 33.5% | 8.1% | 17.0% | 58.6% |

| Malta | 0.0% | 100.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% |

| Luxembourg | 85.8% | 14.2% | 0.0% | 100.0% |

| Finland | 46.0% | 0.9% | 52.7% | 99.6% |

| Latvia | 88.8% | 4.1% | 0.0% | 92.9% |

| Portugal | 60.7% | 3.8% | 25.5% | 90.0% |

| Spain | 52.9% | 3.0% | 30.6% | 86.5% |

| Ireland | 68.5% | 8.4% | 0.0% | 76.9% |

| Slovenia | 8.3% | 12.1% | 55.8% | 76.2% |

| Cyprus | 63.8% | 3.8% | 6.5% | 74.1% |

| Greece | 22.4% | 4.1% | 44.2% | 70.7% |

| Austria | 5.7% | 8.0% | 49.6% | 63.3% |

| Slovakia | 29.0% | 8.4% | 25.4% | 62.8% |

| Italy | 26.5% | 1.8% | 31.6% | 59.9% |

| Poland | 47.0% | 10.0% | 1.7% | 58.7% |

| EU-27 | 33.5% | 8.1% | 17.0% | 58.6% |

| Czech Republic | 35.3% | 6.5% | 14.7% | 56.5% |

| France | 15.0% | 22.5% | 16.4% | 53.9% |

| Romania | 33.6% | 1.4% | 15.1% | 50.1% |

| Sweden | 37.2% | 1.3% | 10.7% | 49.2% |

| Germany | 32.2% | 7.0% | 3.5% | 42.7% |

| Croatia | 34.7% | 3.5% | 3.1% | 41.3% |

| Estonia | 35.6% | 5.3% | 0.0% | 40.9% |

| Lithuania | 30.5% | 2.7% | 0.0% | 33.2% |

| Bulgaria | 5.5% | 0.5% | 19.2% | 25.2% |

| Belgium | 13.6% | 9.8% | 0.0% | 23.4% |

| The Netherlands | 0.0% | 11.9% | 0.0% | 11.9% |

| Hungary | 0.0% | 9.1% | 0.0% | 9.1% |

| Denmark | 0.0% | 2.5% | 0.0% | 2.5% |

| Eco-Scheme/Practice Within an Eco-Scheme | |

|---|---|

| 1. Carbon farming and nutrient management | 1.1. Extensive permanent grassland with livestock 1.2. Winter catch crops/intercrops 1.3. Fertilization plans (basic variant) 1.4. Fertilization plans (liming variant) 1.5. Diversified sowing structure 1.6. Mixing solid manure on arable land within 12 h of application 1.7. Using liquid manure with methods other than splashing 1.8. Reduced tillage systems 1.9. Mixing straw with soil |

| 2. Areas with melliferous plants | |

| 3. Water retention on permanent grassland | |

| 4. Integrated plant production | |

| 5. Biological plant protection | |

| Specification | All Communes | Included Communes with a High Share of ANCs |

|---|---|---|

| The number of agricultural holdings, including participating holdings (thousand): | 1234.3 | 613.2 |

| - in eco-schemes (thous.) | 428.3 | 187.7 |

| UAA area (thousand ha), including UAA area of participating holdings: | 14,096.1 | 6670.1 |

| - in eco-schemes (thousand ha) | 8897.9 | 3495.0 |

| Specification | UAA Under Eco-Schemes in Communes with High Share of ANCs (ha) | Share in Total UAA of Eco-Scheme (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

Eco-Schemes: Eco-Scheme (1). Carbon Farming and Nutrient Management: | ||

| 1.1. Extensive permanent grassland with livestock | 111,282.3 | 71.8 |

| 1.2. Winter catch crops/intercrops | 490,629.2 | 52.9 |

| 1.3. Fertilization plans (basic variant) | 410,696.4 | 36.6 |

| 1.4. Fertilization plans (liming variant) | 59,521.5 | 49.2 |

| 1.5. Diversified sowing structure | 718,410.7 | 51.1 |

| 1.6. Mixing solid manure on arable land within 12 h of application | 392,091.5 | 54.6 |

| 1.7. Application of liquidmanurewith methods other than splashing | 326,369.9 | 54.4 |

| 1.8. Reduced tillage systems | 648,294.6 | 31.7 |

| 1.9. Mixing straw with soil | 627,663.7 | 32.7 |

| Eco-scheme (2). Areas with melliferous plants | 7339.6 | 63.6 |

| Eco-scheme (3). Water retention on the permanent grassland | 76,094.2 | 79.3 |

| Eco-scheme (4). Integrated plant production | 39,959.3 | 37.7 |

| Eco-scheme (5). Biological plant protection | 6049.7 | 24.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zieliński, M.; Józwiak, W.; Żak, A.; Rokicki, T. Development of Eco-Schemes as an Important Environmental Measure in Areas Facing Natural or Other Specific Constraints Under the Common Agriculture Policy 2023–2027: Evidence from Poland. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2781. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062781

Zieliński M, Józwiak W, Żak A, Rokicki T. Development of Eco-Schemes as an Important Environmental Measure in Areas Facing Natural or Other Specific Constraints Under the Common Agriculture Policy 2023–2027: Evidence from Poland. Sustainability. 2025; 17(6):2781. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062781

Chicago/Turabian StyleZieliński, Marek, Wojciech Józwiak, Agata Żak, and Tomasz Rokicki. 2025. "Development of Eco-Schemes as an Important Environmental Measure in Areas Facing Natural or Other Specific Constraints Under the Common Agriculture Policy 2023–2027: Evidence from Poland" Sustainability 17, no. 6: 2781. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062781

APA StyleZieliński, M., Józwiak, W., Żak, A., & Rokicki, T. (2025). Development of Eco-Schemes as an Important Environmental Measure in Areas Facing Natural or Other Specific Constraints Under the Common Agriculture Policy 2023–2027: Evidence from Poland. Sustainability, 17(6), 2781. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062781