1. Introduction

The UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were designed to offer an ambitious roadmap with which to address a wide range of globally pressing social, economic, and environmental threats and challenges. For each SDG, different world regions confront their unique issues and challenges and showcase different types of solutions and levels of progress. Although the SDGs offer a shared language and a standard set of indicators for measuring development, the current level of progress reveals no one-size-fits-all model of success. Different countries and communities face their own sets of challenges, priorities, and circumstances that are unique to them, which influence the progress they make toward the SDGs. Each country and community must develop unique strategies and solutions considering their specific challenges and circumstances; therefore, the SDGs need to be implemented in a manner that reflects and responds to the needs and capacities of specific localities.

Although some progress has been achieved, more work still needs to be carried out to reach the SDGs by 2030. According to the Sustainable Development Report 2024, “on average, only 16 percent of the SDG targets are on track to be met globally by 2030, with the remaining 84 percent showing limited progress or a reversal of progress” [

1]. Furthermore, research has indicated that approximately 65% of SDG targets are directly tied to the responsibilities of local and regional governments [

2], underlining the “urgent need to accelerate SDG localization to improve policy coherence and integration” [

3]. Achieving such goals requires efforts beyond simply aligning national and local policies with them; there is a need to foster incentives for innovation, partnerships, and co-designed solutions that reflect each locality’s unique challenges and opportunities [

4]. Unless the goals and strategies are localized, the endorsement of global principles and a cosmopolitan approach risk losing sight of national variations and contextual parameters. Disregarding or ignoring the dynamics of local communities, indigenous knowledge and local culture risks policy failures and missing the target for Agenda 2030. Countries are required to customize and launch their own versions of sustainable development paths; in other words, the SDGs endorsed by national governments in the global arena need to be implemented at the local level, aligned with context-specific considerations. While the rationale for SDG localization is clear, the concept itself remains ambiguous and lacks a universally agreed-upon understanding.

The extant literature offers ample evidence of several approaches to defining the concept of localization. For instance, the UN views localization as “the process of defining; implementing; and monitoring strategies at the local level for achieving global, national and subnational sustainable goals and targets” [

5]. The official approach treats localization as “adapting and customizing the SDGs and translating them into local development plans and strategies that fit the needs, context, and priorities of a particular region or locality, in coherence with national frameworks” [

3]. Localization is also understood as the role that regional and local governments play in implementing the SDGs to emphasize the importance of sub-national contexts in setting goals and targets; this determines the means of the implementation, monitoring, and measurement of the progress made to achieve Agenda 2030 [

6].

Existing research on SDG localization has examined various dimensions, such as governance frameworks [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11], financing mechanisms [

12,

13,

14], and stakeholder engagement [

15,

16,

17], but often in a fragmented manner. Studies tend to focus on isolated aspects of localization, rather than providing a comprehensive framework for understanding how the SDGs are translated into actionable local policies. The diversity characterizing the many approaches to the localization of the SDGs resembles the analogy of “the blind men and the elephant”, where differing aspects of localization are studied. Yet, a sound analytical picture of the instruments, processes, actors, and strategies utilized in these approaches is still limited.

Despite the growing body of literature on SDG localization, there remains a scarcity of comparative studies that examine how localization efforts differ in various localities. This gap limits our understanding of how contextual factors, such as governance structures, financial resources, and institutional capacities, influence the effectiveness of SDG implementation. Additionally, there is no clear consensus on the most effective localization mechanisms, as existing studies often present fragmented approaches without systematically evaluating their broader applicability. Furthermore, the methodological approaches employed in this field predominantly rely on qualitative case studies, which, while valuable for in-depth analysis, often lack the comparative rigor needed to identify overarching trends and best practices. The absence of large-scale, cross-regional studies incorporating both qualitative and quantitative methods constrains efforts to derive generalizable insights that could inform more effective and adaptable localization strategies.

This study addresses these gaps by providing a structured analysis of SDG localization, connecting fragmented insights, and proposing a holistic framework that integrates diverse approaches. By investigating mechanisms, themes, and cases in the literature, the study aims to offer a comprehensive understanding of the localization process, highlighting key challenges and opportunities. The importance of the study lies in that it offers a sound record and appraisal of the state of knowledge on the localization of the SDGs to provide an informed interpretation of research findings.

In this study, we analyzed localization as a policy transfer mechanism for sustainable development across global, regional, national, and local levels. Using both qualitative and quantitative techniques, we followed an innovative approach to a systematic literature review through employing the data analysis software MAXQDA Analytics Pro 2020. This approach helped us to investigate the patterns and themes addressed by the growing literature on the localization of Sustainable Development Goals.

Our findings contribute to ongoing debates by offering a structured analysis of SDG localization, bridging gaps in existing research, and proposing a holistic framework that integrates diverse approaches. This study advances the debate on SDG localization through addressing these aspects, offering a more integrated perspective that can inform both academic research and policy implementation.

The study is structured as follows: First, in the methodology section, we clarify our mixed methodology and the selection of the samples. A qualitative literature review follows the methodology section to present the latest perspectives on the localization of SDGs. In the analysis section, we present the results of our quantitative analysis of the patterns, trends, and themes of localization. These results pinpoint three major clusters of findings: (i) the state-of-the-art (i.e., the dominant trends in the literature on the localization of SDGs); (ii) the mapping of the SDGs covered in the research on localization; and (iii) a deep dive into the localization of the SDGs in terms of actors, tools, strategies, and mechanisms.

2. Materials and Methods

This study adopted a mixed method analysis of the literature on the “localization of SDGs”. To conduct a comprehensive and rigorous synthesis of the available studies on “the localization of the SDGs”, qualitative and quantitative approaches were employed to conduct a systematic literature review. In doing so, the Web of Science database was used to collect the publications selected for the review. Being one of the most reputable citation indexing platforms, Web of Science (WoS) is a multi-disciplinary research database maintained by Clarivate Analytics; it provides access to high-quality scholarly literature across various academic fields. Web of Science (WoS) was chosen for its strong interdisciplinary coverage and its strict indexing criteria, ensuring that only high-quality, peer-reviewed research is included. This aligns with our study’s objective of conducting a systematic analysis grounded in rigor and reliability. WoS provides a curated collection that enhances the consistency and comparability of our dataset. Given the scope and aims of our study, the depth and interdisciplinary nature of WoS serve as a suitable foundation for our comprehensive review of SDG localization. Although the exclusive use of WoS may introduce a bias by excluding studies indexed in other databases, we mitigated this limitation through stringent inclusion criteria and systematic screening processes to ensure the reliability and relevance of the selected studies. This approach allowed us to focus on high-quality, peer-reviewed articles directly relevant to our research questions, ensuring a rigorous and focused analysis of the SDG localization literature.

According to Harden and Gough [

18], systematic reviews are replicable and transparent tools for reviewing the literature to address specific research questions, where explicit criteria for including or excluding existing research can be used.

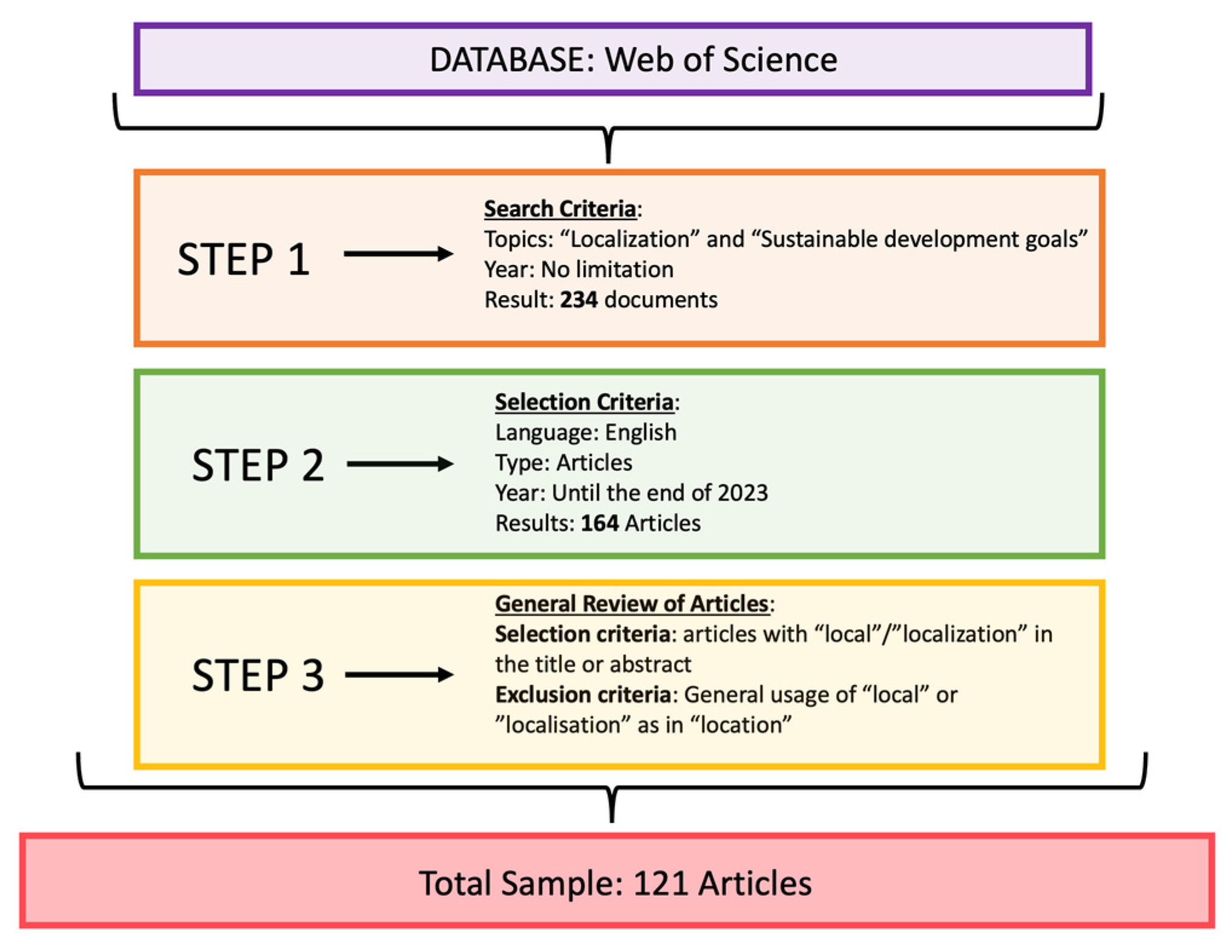

As a first step in our systematic review, we searched for relevant articles covering the topics of “Localization” and “Sustainable Development Goals” without any publication year restriction. This initial search resulted in identifying 234 documents. The results were further filtered to only include English-language publications (227 results) and “articles” as the document type, resulting in 184 hits. The sample was finally restricted to the end of 2023 as the publication year, resulting in 164 articles. Next, all the results were qualitatively screened with the following inclusion criteria: The title and/or the abstract should have the words “local”/“localization”. The articles that use “localization” in general (as in “location”) or out-of-context terms were excluded. The final list consists of 121 articles in total.

Figure 1 summarizes the steps followed in the sample selection process.

After identifying the articles, all 121 articles were downloaded for further analysis using the MAXQDA software (the full list of these 121 articles is available in

Appendix A and List of References). MAXQDA is a tool that allows researchers to conduct mixed-method analyses. The documents imported to MAXQDA can be “coded” qualitatively and/or quantitatively, depending on the purpose of the research. The coding process helps to identify key themes, patterns, or concepts within the data. MAXQDA provides further statistical information on data, such as the code frequencies, relative coverage of selected concepts/topics/arguments, and the relationship between codes. In this study, the texts in the published articles constituted the dataset. The analysis section of the paper offers a detailed description of the steps involved in our analytical examination of the data. The analysis included three major dimensions in the literature on localization and the SDGs: (a) the overall patterns; (b) the mapping of the SDGs regarding the topics addressed; and (c) an X-ray study of the “localization” concept.

In the SDG mapping, the coding process was based on a keyword search for each of the SDGs. Over the last few years, several institutions—especially higher education institutions—have created databases of keywords for each SDG. Some examples are the University of Toronto SDG Keywords, Daftar keywords for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Monash University and SDSN Australia Database, Elsevier SDG Keywords, and University of Auckland SDG Keywords Mapping.

Our analysis used the University of Auckland SDG Keywords Mapping [

19] as it provides one of the most comprehensive collections with a clearly disclosed methodology (for further information and the keyword database, please visit Weiwei Wang, Weihao Kang, Jingwen Mu. Mapping research to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs),

https://www.sdgmapping.auckland.ac.nz (accessed on 19 February 2023)). As the developers of this database clarify, text-mining techniques and methods were utilized to generate collections of keywords associated with the SDGs from Elsevier’s Scopus database. Their search query for the database incorporated Elsevier’s SDG search query; it was supplemented with additional search terms obtained from documentation provided by the Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN) and the United Nations (UN) [

19]. They followed a data-mining exercise, examining the abstracts of research articles, identifying keywords, and manually reviewing high-ranking keywords to ensure their relevance to the selected SDG.

One limitation of the University of Auckland database is that it covers only 16 SDGs, thus missing SDG 17. This limitation is not unique to this database’s SDG Keyword Mapping, and interestingly, many other databases only cover 16 SDGs. To address this limitation, we complemented the existing database with keywords for SDG 17 obtained from the work of Monash University and SDSN Australia (The final list is too comprehensive to be added to this paper; however, Excel lists of the keywords are available in the database webpages:

https://ap-unsdsn.org/regional-initiatives/universities-sdgs/, accessed 15 February 2023.). In

Table 1, the total number of keywords we used for each SDG by combining the two mentioned databases is summarized. We noted that the distribution of keywords was not equal across the SDGs. However, as the results of our analysis indicated, we did not detect any biased coverage in favor of the SDGs with more keywords.

The steps followed in the analysis and the presentation of our results are discussed in the following sections.

3. Qualitative Literature Review

Can “localization” support the process of Agenda 2030? Numerous studies have highlighted the limitations and challenges associated with the full implementation of localization, particularly in developing countries, due to organizational capacities and the lack of internal capabilities to foster them [

20,

21,

22].

Several studies have focused on the role of local governments in the localization process, shedding light on the dynamics at the local and urban levels [

23,

24,

25,

26]. In the era of Agenda 2030, there is a growing need to reconsider urban challenges and gather updated evidence; these strategies require a collaborative approach among stakeholders in multi-stakeholder partnerships to develop livable urban spaces. Therefore, up-to-date evidence is urgently needed to inform effective strategies and interventions. In this framework, ElMassaha and Mohieldin [

24] noted the policy space for digital transformation, which has the potential to greatly impact SDG localization and attainment.

The successful integration of SDG localization depends on several factors, including the presence of suitable structures and effective leadership and co-ordination. Flexibility, organizational learning, and timing are also critical in achieving successful SDG integration. However, implementing the SDGs within management systems and budget allocations and motivating stakeholders across different levels and divisions presents challenges to this integrated approach. To illustrate this, Krantz and Gustafsson [

21] showed that the SDG framework allows municipalities to comprehensively evaluate and assess their organizations from a sustainability systems perspective. Despite such an opportunity for evaluation and assessment, various challenges persist, such as the inherent complexity of integrating sustainability, the importance of political support, the need for sufficient capacity and inclusivity, and the management of ongoing efforts and policies across sectors. Key individuals with authority and influence can act as driving forces in overcoming these challenges and facilitating progress.

Novovic [

22] argued that the Agenda 2030 framework places national governments and local actors at the forefront, entrusting them with the responsibility of leading the agenda-setting and decision-making processes necessary to achieve the SDGs. Additionally, localizing the SDGs involves aligning policies, utilizing indicators and statistics, and raising awareness among diverse stakeholders, including civil society and parliamentarians. To illustrate this using an example from Tanzania, Jönsson and Bexell [

20] revealed the challenges associated with localization. These challenges primarily revolve around co-ordination issues, limited data availability, funding shortages, and a lack of widespread awareness. The obstacles faced in localizing the SDGs appear to be linked to inadequate co-ordination, resulting in parallel processes, ambiguity in assigning responsibilities, and a high turnover of personnel in public administration. Furthermore, both human and material resources are deficient.

Another subject area in which the concept of localization has been studied extensively is development aid. Commitment to localization at the national and global levels has been extensively examined in various studies exploring debate in the development aid sector [

12,

14,

20,

27]. These studies address crucial questions about the potential of the SDGs to address structural problems in development aid policies and practices, such as accountability and coherence deficits, unequal power relations, and depoliticization. One approach to addressing these structural problems is identifying opportunities for subnational interventions to achieve multiple targets and indicators by creating integrated key performance indicators [

28]. For example, Belda-Miquel, Boni, and Calabuig [

14] reported the tensions arising from adopting the SDGs; and underlined that connecting global development and sustainability issues may promote coherence but can also obscure the specific role of aid and aid policies.

Bringing in perspectives from a developed country context offers additional dynamics for localization. Lanshina et al. [

29], who examined high-performing countries’ experiences in implementing the SDGs’ localization, shed light on this developed country context, identified based on the SDG Index compiled by the SDSN Australia Database and Bertelsmann Stiftung. The authors concluded that, even within this select group of countries, there are significant variations in the journey towards sustainable development and SDG execution. Some nations embraced national sustainable development strategies as early as the 1990s, whereas others did so in the early 2000s. Moreover, these countries are at different stages of SDG implementation in their strategic documents, ranging from a lack of localization to the localization of all 17 goals. Despite these disparities, all the countries examined have established mechanisms for coordinating SDG implementation, primarily through inter-ministerial groups comprising representatives from different ministries. The study reveals that time is an important factor in localization. Regarding the SDG Index, the leaders have embraced sustainable development principles for an extended period, typically exceeding 15 years, and have developed coordinating mechanisms for SDG implementation under executive branch agencies. However, it is worth noting that not all of them have integrated the SDGs into their national sustainable development strategies, and not all have adjusted their strategies following the adoption of Agenda 2030, as exemplified by Scandinavian countries [

29].

Another aspect is underlined by Suri, Miraglia, and Ferrannini [

27], who emphasized the value of the voluntary review process as a tool for localizing SDGs, particularly in cities. According to their findings, this approach enables cities to progress on their specific local priorities in a participatory, inclusive, and transparent manner, potentially accelerating SDG localization significantly. It is suggested that the voluntary review process can promote the use of innovative data and customized measurement frameworks at the local level, providing a more accurate understanding of progress. It can also foster multi-stakeholder awareness, commitment, and partnerships to collectively work towards achieving the global goals. However, it is important to acknowledge that structured frameworks for coordinating and aligning policies for voluntary reviews at multiple levels are currently lacking, and only a few successful and innovative examples can be identified in this regard.

Fox and Macleod [

25] emphasized the importance of embedding the SDGs into local policymaking, which requires a process of translation facilitated by embedded advocacy and university–city partnerships. The SDGs have demonstrated their ability to convene local actors, foster international city networks, and allow cities to showcase their global ambitions and progressive identities by embracing a globally endorsed policy agenda. Developing new SDG monitoring methods and frameworks is crucial to fully embrace the growing trend of subnational engagement in global policy.

Localization involves tailoring sustainable development strategies to the local level, enabling governments to effectively address specific needs and circumstances. This approach combines the advantages of decentralization and centralization in governance without compromising the benefits of either. It facilitates the alignment of local communities with national policies and promotes national security while improving public service delivery through transparency and accountability, which are advantages of decentralization. Delgado-Baena [

23] also supports this approach, highlighting that local governments, with their organizational culture and structure, play a key role in establishing public policies linked to Agenda 2030. Local authorities perceive the SDGs as an opportunity to transform themselves, recognizing that localization requires a commitment to public innovation, openness, collaboration, transversality, and interconnectedness among entities. Localization can foster widespread ownership of the SDGs across all levels of society and represents a practical method for achieving the SDGs and Agenda 2030. To successfully localize the SDGs, local governments need to engage in effective planning, ensuring that budget allocations align with the priorities of local communities.

The alignment of societal awareness and cultural attitudes towards sustainability is another focus area identified for successfully localizing the SDGs [

30]. In relation to attitude formation and local cultural characteristics, the integration of Social Innovation (SI) and Scenarios Thinking (ST) emerges as a valuable mechanism that empowers citizens, including young people and decision-makers, to develop cohesive plans, policies, and programs for achieving the SDGs [

31]. Liu, Bai, and Chen provided a concrete case study to illustrate the effective promotion of sustainable preservation and utilization of terrestrial ecosystems worldwide [

32]. This case study offers a quantitative assessment of the implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 15 (SDG 15) across all administrative levels, with a particular focus on the grassroots level. The results indicate that challenges remain regarding the relationship between the goal and its indicators in terms of capturing local variations.

As the qualitative literature review reveals, scholars have made some efforts to examine and understand the various dimensions of localization. However, these efforts often address only isolated aspects of the concept. To provide a comprehensive perspective on the localization of SDGs, the following section presents a quantitative analysis that aims to integrate these fragmented insights. This approach offers a holistic view, enhancing our understanding of the effective processes involved in SDG localization.

4. Results: Patterns, Trends, and Themes of Localization

This section presents the results of the analytical analysis of the literature on the localization of SDGs. The aim is to reveal major themes, patterns, and mechanisms for the localization of SDGs.

4.1. The State of the Art

Our sample for analysis consists of 121 articles.

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of the articles per year. The Sustainable Development Goals, our focus of concern, were launched in 2015. Although we did not have a year restriction in the selection phase, we did not expect to obtain many hits before 2015. We still included pre-2015 articles (four articles) since they addressed issues such as a sustainable future [

33], food systems [

34], value-based indicators of the SDGs [

35], and localization of climate action [

36], which are highly relevant topics in terms of the SDGs. Since 2019, there has been an increase in interest in the localization of the SDGs in the literature, with a peak in 2023. This surge reflects a growing scholarly interest in the practical implementation of the SDGs at the local level, coinciding with increased global efforts to achieve Agenda 2030.

The initial steps of our analysis aimed to have a descriptive outlook on the state of the literature on SDG localization. As the word cloud designed for the most frequently used words in the titles of the 121 articles illustrates (

Figure 3), there is a mix of case studies (i.e., Tanzania, Botswana, Africa, or China), issue areas (i.e., climate, food, urban development, and indicators), and processes and action items (i.e., assessment, implementation, measuring, and planning). This variety suggests the broad scope of SDG localization research, encompassing diverse geographical contexts (e.g., Tanzania, Botswana, Africa, and China), thematic areas (e.g., climate, food, urban development, and indicators), and practical approaches (e.g., assessment, implementation, measuring, and planning); reflecting the complex and multi-faceted nature of the topic and its investigation in the current literature.

Our analysis disclosed that 79% of the articles used case studies. Indeed, the fact that case studies dominate the literature is important; it underlines the importance of local circumstances, dynamics, and requirements for the different settings investigated. Once we classified all the case studies utilized in the articles, we discovered that the literature provides different levels of analysis (see

Table 2). Some articles (33%) examined country-level case studies regarding specific countries, including, but not limited to, Malaysia, Germany, Sweden, Finland, India, and Canada. China, in particular, accounts for the largest share regarding the number of case studies implemented. Other articles focused on Africa as a region. Along with Africa, the European Union was another region investigated at the regional level. The sub-country level cases (12%) mainly addressed provinces in the selected countries.

City-level analyses emerged as representing the second highest (20%) number of articles in the sample, exploring the city-level efforts of localization in cities, including Buenos Aires, Cape Town, Bratislava, and Madrid. Last, but not least, some studies examined more specific micro-level cases, such as particular aid projects [

13,

37] and practices in national parks [

38,

39] or companies [

40]. Overall, with the exception of Jordan [

41], we did not detect any case studies from the Middle East in the sample.

This distribution underscores the importance of national policies in promoting sustainable development while recognizing the crucial role of cities as key sites for SDG implementation. However, the relatively few regional and micro-level analyses (6% and 7%, respectively) suggest a need to explore SDG localization in varied settings to fully understand the specific dynamics of different contexts. Furthermore, the lack of case studies from the Middle East indicates a potential geographical bias in the existing research.

4.2. SDG Mapping

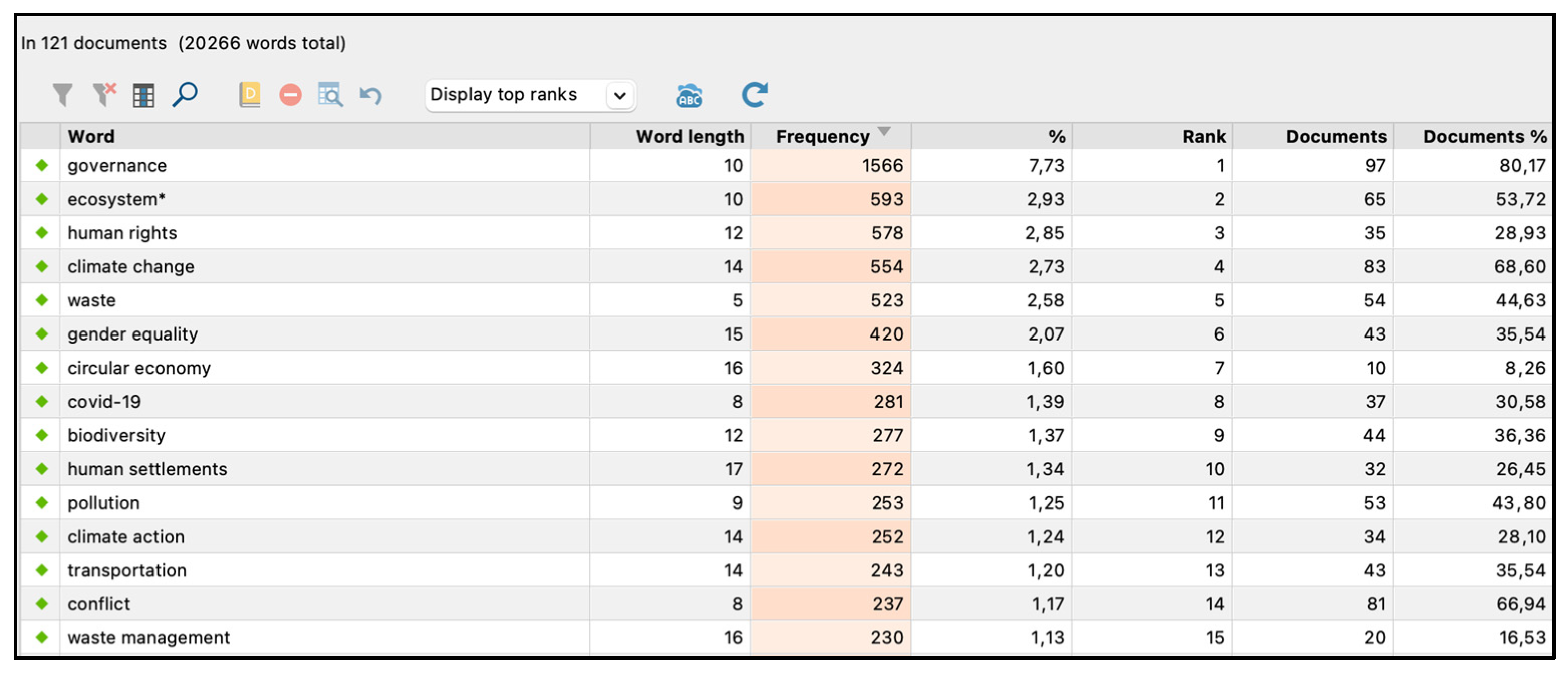

As part of our analysis, we created a mapping involving two major spheres: the coverage of the SDGs and the examination of localization as addressed in the state of the art. As was stated in the methodology section above, our SDG mapping was based on the selected keywords database. We imported all 2368 keywords, classified for each SDG, into MAXQDA for a quantitative analysis. In 121 documents, a total of 20,266 words/word combinations were hit for the SDG keywords. As the word cloud created for the word frequencies of these keywords displays (

Figure 4), there is a very significant emphasis on “governance” (79% of the articles addressed “governance”).

A closer look at the sampled articles’ most frequently used SDG keywords reveals that some concepts have reoccurred multiple times.

Figure 5 demonstrates the top 15 SDG keywords most frequently used in the articles in our sample. The column “frequency” represents the number of hits, and the last column, “Document %”, represents the percentage of documents in our sample that used the keyword. As per the document percentages, “governance” is at the top of the list, followed by “climate change” (68.6% of the articles), “conflict” (66.9 % of the articles), and “ecosystem(s)” (53.7 % of the articles).

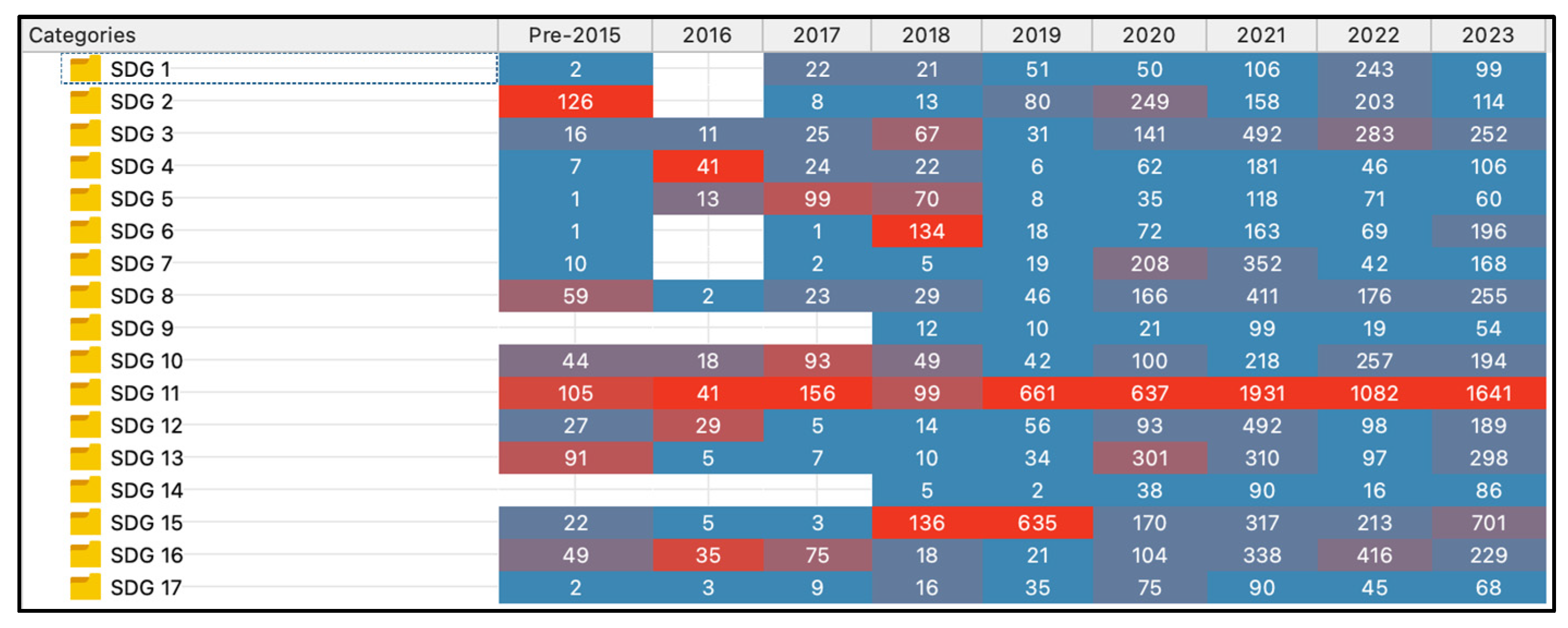

Using the MAXQDA MaxDictio functions, we created an “SDG Dictionary”, which assigns each categorized keyword to the relevant SDG (see

Table 1 on page 6). For this exercise, we determined the aggregate keyword frequencies, which revealed the coverage and relative weight of the SDGs in the literature across the years. Considering our analysis, “reference” to an SDG means the following: (a) an actual usage of the label, such as “SDG 4” and “SDG 10” and/or (b) the keywords that correspond to the issue areas to be covered by each SDG, their targets, and indicators. In the latter condition, the article does not necessarily have to use the exact SDG label; rather, as per the keyword collections, the theme that pertains to the SDG matters. In line with our sample selection criteria (topic: “localization” and “sustainable development goals”), it is not surprising that all 121 articles cover at least one SDG.

Table 3 lists the ranking of the SDGs, indicating that SDG 11 on Sustainable Cities and Communities (Making cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable), SDG 16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions), and SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) are the top 3 SDGs covered by the greatest number of articles in our sample. This high focus on urban development, governance, and economic growth is not mirrored in the coverage of other SDGs, such as SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure), SDG 14 (Life Below Water), or SDG 5 (Gender Equality), which receive significantly less attention, highlighting a potential need to diversify the research efforts.

In order to create a complete mapping of the SDGs, we used the category matrix browser feature of MAXQDA. We created the following heatmaps (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7), showing the articles clustered by years compared to 17 SDGs. The numbers in the table represent the number of times the keywords assigned to each SDG were used and thus coded. The intensity of the red color in the heatmaps increases with the number of hits.

Figure 6 illustrates the peak coverage year of each SDG in our sampled articles. As the heatmap indicates, there is a significant overall concentration in 2021 since it marks the most cited year for most SDGs, except a few.

Figure 7 demonstrates which SDGs are covered the most in a given year. To illustrate, in 2023, SDG 11 and its constituents are the themes that are most addressed. In fact, SDG 11 appears to consistently dominate the research agenda, focusing on the localization of the SDGs over the years. SDG 6, and SDG 15 also emerge among the most frequently used SDGs.

4.3. Understanding Localization

Following the SDG mapping, the next step in our analysis was to understand the concept of localization, specifically the key focus areas, patterns, and priorities addressed in the literature. We wanted to understand the elements that were associated with the localization of SDGs. To this end, we conducted a quantitative MAXQDA inquiry beyond the SDG keywords. First, we identified the most cited word combinations (with two to three words) throughout the articles in the sample, which amounted to 280,827 in total. Next, we filtered the word combinations, which included “local”, resulting in 4420 hits. These filtered combinations were reviewed qualitatively and coded manually in clusters. The word “localization” and the usage of “local level” (as in the local, national, and global levels) were excluded because all articles, by their nature, would include them in large quantities according to the selection criteria of the articles for our sample. Instead, we included word combinations that point out the mechanisms, processes, tools, or actors regarding localization. This exercise resulted in 4144 coded segments (i.e., sentences that include word combinations with “local”) and 206 codes (i.e., 206 different word combinations with “local”).

Table 4 displays only the top 20 word combinations ranked by the number of documents referring to them (left section); this is compared to the top 20 word combinations ranked by the highest relative weight among the coded sentences in the articles (right section).

As

Table 4 indicates, around 68% of the articles referred to “local governments” in their research, followed by “local communities” (57% of the articles). Changing the focus of analysis from the number of articles to the number of coded segments reveals a different set and ranking of word combinations. Suppose we check the relative weight of these selected combinations within the overall coded segments. In that case, it is possible to conclude that local governments were not only addressed by a majority of the selected articles but that the concept also dominated the overall coded segments on local elements; out of 4144 coded segments from the articles, 1467 included the term “local governments”.

This confirms that existing research significantly focuses on the role of local governing bodies and that their role is central to SDG localization. The frequency of “local communities”, “local context”, and “local action” reinforces the fact that localization is a process that requires local knowledge and participation. The presence of phrases such as “local economic development”, “local food systems”, and “local climate policy/action” further emphasizes the specific areas that are the most studied in the current literature.

In the following step, we clustered these codes under bigger themes to obtain meaningful insights from this exhaustive list of word combinations containing the “local” label. For the clusters, we identified five major categories (localization elements) that shaped the localization of the Sustainable Development Goals. These are the following: actors, contextual elements, mechanisms, tools, and topics.

Table 5 demonstrates the distribution of these five categories across the articles in the sample.

According to our results, around 98% of the articles covered at least one element of the categories identified for localization. While each category could constitute a separate research focus on its own, for the purposes of this study, we provide a general overview of the results. The category of “Actors” stands for all the stakeholders who were studied or cited while discussing the localization of a selected SDG. Under this category, we identified more than 63 types of stakeholders, with “local governments” being the most-cited stakeholder mentioned in 68% of the articles, followed by “local communities” (57%) and “local authorities” (33%).

It is important to note that, for these subcategories, the rankings are presented for statistical purposes and, eventually, rather than their ranking scores, what matters more is the wide and different array of stakeholders who are (or can be) involved in localization processes or can initiate and lead the transfer and implementation of the global SDG agenda at the local level. These stakeholders include, but are not limited to, local people or residents, local civil society, NGOs or businesses, local educational institutions such as universities, or academics (a full list of the findings is presented in

Appendix B for all categories).

The second category, “Contextual Elements”, references local characteristics and context-dependent elements that impact localization. Our results indicate that 80% of the articles mentioned at least one element in this category; 40.5% of the articles refer to “local context”, followed by “local needs and priorities” (20.7%). Local challenges, problems, and struggles fall within this category. Key factors impacting stakeholders’ perspectives are also among the contextual elements. To illustrate the values, aspects such as interests, culture, social dynamics, narratives, and even local traditions have a role in localizing the global sustainable development agenda.

Another category relates to the mechanisms that drive localization. The elements included in this category are associated with process-based factors, such as planning, building partnerships, reporting, monitoring, adaptation, co-production, or policymaking. A total of 66.9% of the articles mentioned at least one of these localization mechanisms. Along with mechanisms, our analysis also revealed tools that support these localization mechanisms. Another 66.9% of the articles also refer to local resources and tools that can be used for localization. Some of these local elements are local climate policies, legislations, local interventions, and local innovations.

In 31.4% of the articles, we detected specific issue-based references to different local elements. This signals some specific areas of concern to be addressed while localizing the SDGs. We labeled this category “Topics”, where some issue areas were specifically used with the label “local”, signaling a potential role in localization. Some of these include local food systems, local energy, local job market and labor force, local public health, local natural habitat, and local markets.

Appendix B lists all 206 word combinations for further reference.

As the last step in our analysis, we wanted to understand the emphasis given to each localization element in our sample. To this end, we investigated the relative weight of each code within the overall coded segments in the articles. As

Figure 8 illustrates, references to local actors significantly dominated 61.29% of the overall content in the articles in our sample. This revealed the key role that actors and stakeholders play in the localization of the SDGs.

5. Discussion

As research on SDG localization continues to grow, one can argue that, along with efforts to localize the SDGs and accelerate sustainable development, there is also an increasing trend to understand localization as a distinct phenomenon. The efforts made to localize the sustainable development goals have heightened, especially with the 2019 Seville Commitment, which called for local governments to play a greater role in achieving sustainable development and emphasized local action in the path to fulfilling the Agenda 2030 [

42]. This is also reflected in scholarly research since scholars have increasingly examined the complexities of SDG localization, revealing a trend in SDG localization research since 2019, peaking in 2023, which reflects the growing urgency of translating global goals into actionable local policies.

Myriad challenges that hinder the effective local implementation of the SDGs have been identified in the available literature on sustainable development and localization [

43,

44,

45]. Prominent examples of these challenges include the following:

Establishing an awareness and understanding of the SDGs within the local community and among stakeholders [

46,

47].

Developing the necessary capacity of educators and policymakers to incorporate the SDGs into school curricula and develop strategies effectively [

48].

Insufficiency of financial and human resources, which can greatly impede the implementation of SDG education and localization endeavors [

49].

Lacking or inefficient co-ordination or collaboration within the community and among stakeholders [

8,

50].

Designing rigorous tools and mechanisms for monitoring and assessing progress in SDG localization [

51].

Addressing these challenges and advancing the localization of the SDGs require a holistic approach that involves raising awareness, engaging the community and stakeholders, building local capacity, and developing relevant sustainable development policies to ensure that localization is a transformative policy mechanism rather than a conceptual exercise.

The findings underscore the critical role of local governance in implementation of the SDGs. Effective localization relies on robust institutional structures and well-defined policy frameworks. While the causal relationships between specific characteristics of local governance and the effectiveness of SDG localization policies, along with examples of best and worst practices, require further investigation, our analysis signals the need for strong institutional capacity-building, policy coherence, and adaptive frameworks. Strengthening local governance through localized indicators, integrated monitoring, and flexible policy mechanisms is essential. However, these efforts should complement rather than overshadow grassroots initiatives, which remain crucial for inclusive and context-sensitive sustainability actions.

Equally important is the need to promote collaboration among key players, i.e., governmental organizations, civil society, the private sector, and the broader community. Our results revealed that of all the elements associated with the local level, “actors” was the most frequently stated category. Our interpretation is that the focus on actors indicates that local actors and stakeholders play a pivotal role in translating global SDG frameworks into actionable policies. Agency, particularly at the community level, is central to successful localization.

The inclusion of local people and local stakeholders is important for customizing localization in line with content and ensuring ownership of the sustainable development measures for long-term engagement and adaptability. However, the analysis reveals that local actors beyond governments, such as local businesses, local civil society, local unions, local suppliers, local education institutions, and local residents, are recognized but less frequently analyzed; this limits insights into multi-stakeholder collaboration.

A people-centered approach that fosters collaboration among governments, civil society, the private sector, and local communities can create synergies that enhance localization efforts and ensure their successful implementation.

Multi-stakeholder engagement and co-creation in localization can benefit from further research on social innovation and decision-making processes. García-Flores and Martos [

52] found that there is a strong connection between sustainable development and social innovation; the latter plays a pivotal role in advancing social and environmental goals on a global scale. Social innovation serves as a catalyst for developing processes and methodologies that drive more effective and inclusive social outcomes. This dynamic and participatory approach fosters transformative change, enhancing the impact of sustainability initiatives [

52].

Engaging stakeholders and empowering them to play a role in developing sustainability goals may also provide further opportunities for localization. Involving stakeholders such as community leaders, non-government organizations, and local businesses in the decision-making process fosters a sense of ownership, ensures cultural relevance, integrates local knowledge, and encourages innovation, all of which are essential for effective localization efforts. Multi-stakeholder involvement, however, circles back to the challenge and need for capacity building through investments in education for sustainable development, learning platforms, and peer-to-peer best practice-sharing networks [

3,

53]. Given the role of agency in the localization process, it is crucial to ensure that actors are aware of their fundamental role and feel empowered to get involved.

This also connects to the need for more practical research on the tools, processes, and strategies for effective implementation. It is noteworthy that, while local “context”, “mechanisms”, and “tools” are frequently mentioned across the analyzed articles (

Table 5), their prominence diminishes when examining the depth of discussions on localization (

Figure 8). The significant reduction in their share within the coded segments (mechanisms: 11.87%; tools: 11%) suggests that, although the importance of local adaptation is widely acknowledged, substantive engagement with specific localization strategies remains limited. Concrete tools such as local SDG platforms, public policies, or co-design interventions remain underexplored. Moreover, the notably low representation of “topics” (2.7%) within the coded segments indicates that issue-specific analyses are scarce in the literature despite general recognition of the need for contextualized approaches.

According to our results, the emphasis on governance and local governments in the literature is combined with high coverage of SDG 11 on sustainable cities and communities, and local governance at the city level seems to lead localization efforts. We can conclude that cities emerge as critical policy spaces where the global agenda on sustainability translates into local practices. Cities can provide an important playground for multi-stakeholder engagement, enabling innovative governance models that bridge global ambitions with local realities.

The results also reveal disproportionate SDG coverage; SDG 11 leads in terms of attention, others, for example, SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure: 39.67%), SDG 14 (Life Below Water: 33.88%), and SDG 5 (Gender Equality: 46.28%) receive less focus (

Table 3). We suggest that the disparities in SDG coverage stem from gaps in localization studies rather than indicating that the less-represented SDGs are inherently less relevant for localization. These disparities can be due to several factors. First, the lower representation of certain SDGs may reflect gaps in research priorities rather than their actual relevance for localization. The disproportionate focus on SDG 11 suggests that some SDGs may be overlooked due to a combination of data availability, funding priorities, and institutional incentives, making them harder to investigate.

Second, SDG 11 is inherently linked to local governance structures, making it a natural focal point for localization studies. Cities and municipalities often play a direct role in implementing sustainability policies, whereas SDGs related to other issue areas may require coordination across different governance levels. Third, the underrepresentation of some SDGs could also indicate a lack of political and financial incentives for their local implementation. Localization requires significant resources, and governments may prioritize SDGs that align with existing development plans and strategies. All these factors need further investigation and require empirical validation through future research. Exploring these aspects in greater depth could provide valuable insights into the underlying reasons for SDG coverage disparities and inform more holistic localization strategies. If certain SDGs are consistently under-addressed, critical aspects of sustainability, such as gender equality or ecosystem preservation, may be neglected in local initiatives.

The limited attention given to certain SDGs underscores the necessity for deeper exploration and targeted research in these areas and underlines the need to balance sustainable development’s economic, social, and environmental aspects. To address these imbalances, future research should explore the localization of underrepresented SDGs. Highlighting the interconnectedness of SDGs in research calls and funding programs can encourage research on underexplored SDGs. Expanding the scope of studies can ensure a more comprehensive and effective approach to understand and implement the localization of SDGs.

6. Conclusions

The progress of the SDGs requires strong interactions between local and global actors in such a way that the global agenda, SDG discourse, and sustainable development efforts can diffuse to the local level with tangible policy outcomes. The discussion on localization significantly concentrates on the roles of local state authorities and highlights the importance of localized indicators, reporting systems, and local implementation. Although this transfer sounds like an automatic procedure, there is still limited awareness and emphasis on the mechanisms that trigger effective localization. Opportunities for localizing the SDGs need to be viewed from a holistic standpoint that involves education and national development strategies; this requires giving equal weight to economic, environmental, and social fields.

Through integrating and analyzing fragmented insights, this study (a) enhances the holistic understanding of the processes involved in SDG localization, (b) identifies key elements shaping localization (including actors, contextual factors, mechanisms, tools, and topics), (c) offers valuable insights into research trends and patterns, and (d) reveals critical gaps in the geographic- and SDG-specific scopes of existing research.

The findings presented in this paper reveal some key lessons that inform and complement the discussion. Case studies are crucial in terms of illustrating good SDG practices. Although localization can be unique for each case as per its very nature, sharing experiences, analysis, and stories can be instrumental in identifying the lessons learned for better practices. The articles selected in our systematic review significantly addressed case studies. However, while some cases were extensively studied (e.g., China), others were missing or largely under-studied (as in the case of the Middle East). Conducting additional case studies to identify local factors contributing to progress in regions that suffer from climate change, social or economic difficulties, and human security challenges at the water, energy, and food nexus is important to reveal the key dynamics involved in localization. There is a need in the literature for more case studies from under-represented regions, such as the Middle East and North Africa, in order to capture a more comprehensive understanding of dynamic and diverse governance contexts.

While this study provides a comprehensive synthesis of the literature on the localization of the SDGs, some methodological limitations warrant acknowledgment. The exclusive reliance on the Web of Science and English-language publications may have restricted the scope of our review, potentially excluding pertinent research available in other languages or alternative databases. We mitigated this limitation through stringent inclusion criteria and systematic screening processes to ensure the reliability and relevance of the selected studies. Additionally, our study did not apply any exclusion criteria based on regional scope, ensuring that non-English-speaking regions were represented in the analysis of overall patterns, as evidenced by the diversity and breadth of case studies included. Future research would still benefit from expanding the literature search to encompass multiple databases and non-English sources, thereby enhancing the comprehensiveness of the review. Studies published in other languages (e.g., Arabic, Spanish, French, Chinese) could provide additional perspectives on SDG localization, particularly concerning local contexts and governance models.

In addition to academic publications, gray literature, including NGO reports, government documents, and policy briefs, could offer valuable insights into the practical implementation of SDG localization. These sources often contain detailed case studies, program evaluations, and policy recommendations that can complement the findings of this research.

Additionally, our quantitative analysis leveraged keyword mapping to generate a strategic, data-driven overview. For a deeper investigation, incorporating qualitative methodologies—such as interviews or focus group discussions—would also provide a more nuanced understanding of localization processes and further refine the identification of latent patterns in mechanisms, tools, and strategies. In this regard, future research can highly benefit from our findings for further in-depth examinations of the gaps, such as underexplored SDGs, cases, and local components presented in previous sections.

Last, but not least, aligning the SDGs with local circumstances and priorities is more than merely a technical procedure. Progress can be achieved through a shared vision enriched with local components. In this regard, our analysis detected a limited emphasis on the local context, including culture, indigenous knowledge, local heritage, local values, and the role of education in paving the way for targeting social, cognitive, and behavioral change in favor of sustainable development. The discussion would benefit from a deeper examination of how local factors—including culture, values, and traditions—influence the process of SDG localization. Future research is needed to delve into these areas and explore the relevance of contextualized factors and their impact on sustainable development in depth.