Abstract

The pursuit of sustainable protein is underway. This debate is often framed as a choice between two competing agrifood futures: the “no cow” and “clean cow” perspectives. The former comes from alternative protein advocates, while the latter aims to support practices, discourses, and livelihoods associated with regenerative ranching. The findings presented reveal greater nuance than what this simplistic dichotomy suggests. This paper utilizes data collected from fifty-eight individuals in California and Colorado (USA). Participants in the sample were identified by their attendance at various events focused on sustainability in protein production and includes a subsample of regenerative farmers who self-identified as persons of color, disabled or differently abled, and/or part of the LGBTQIA+ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer/Questioning, Intersex, Asexual) community. The sample features a range of viewpoints associated with regenerative livestock and non-livestock protein production. The data support arguments aligned with “clean cow” framings, as determined by the anticipated scope of sustainable protein transformations. However, the paper cautions against solely relying on this frame without further interrogating its contours. It particularly notes that the values of specific “clean cow” actors and networks mirror key aspects of “no cow” perspectives. These similarities are especially evident among upstream actors like investors, corporate interests, and government sponsors. For these individuals and networks, the “no” versus “clean” distinction—despite suggesting radically different agrifood futures—overshadows underlying shared concerns that align with core elements of the status quo. A case is also made for greater reflexivity and, thus, inclusivity as we think about who is included in these debates, as the data tell us that this shapes how we frame what is at stake.

1. Introduction

Animal agriculture has come under increased scrutiny, especially since 2006, when the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) released a report titled Livestock’s Long Shadow [1]. This report concluded that meat, dairy, and egg production accounted for roughly 18 percent of greenhouse emissions globally. Since then, peer-reviewed estimates indicate animal agriculture is responsible for between 11 and 20 percent of the world’s annual greenhouse gas emissions [2,3,4]. Diets that are based heavily on animal proteins, particularly beef and processed meats, have been criticized by health professionals for their links to higher morbidity and mortality rates [5,6]. Factoring intensive animal agriculture’s association with air and water pollution, zoonotic disease, and drug resistance [7,8] into this “long shadow”, the groundwork is laid for claims about how we are living in the age of Apocalypse Cow [9].

Animal agriculture is facing unprecedented market conditions, which some in the sector equate to an “existential threat” [10]. Survey data indicate that consumers are increasingly concerned about the impacts of livestock, which is influencing meat consumption [11]. Consumers are also becoming more comfortable with preparing and eating alternative proteins, including meat cultured in labs [12,13]. One recent study conducted by Purdue University found that among individuals unwilling to consume chicken, cow, and pig, approximately 46 percent, 26 percent, and 22 percent expressed a willingness to try cultivated versions of these meats, respectively [14]. It is also noteworthy that alternative protein companies are nearing price parity with some of their products [15].

In addition to pressures from both supply and demand, efforts aim for the “strategic devaluation” of animal agriculture [16]. Strategic devaluation involves intentional collective action designed to undermine the value produced by a legacy industry, including via disinvestment activism and raising the cost of doing business for specific sectors through political measures—consider how climate change-related policies have affected the coal industry. For example, in 2021, Berkeley, CA, became the first city in the US to urge its state’s public employees’ retirement system to divest from industrial animal agriculture. At the time of the resolution’s passage, the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) had invested approximately USD 680 million in companies such as JBS and Tyson [17]. Additionally, several universities in the US, UK, and Europe have moved to “divest” from animal agriculture by broadening their non-animal-based protein offerings or becoming entirely meat-free [18,19].

Proponents of animal agriculture argue that anti-livestock critiques represent an example of throwing the baby out with the bathwater—meaning they discard something valuable while trying to eliminate something undesirable. They, therefore, push against what they view as a simplistic “bad animal” narrative [20]. This viewpoint is famously captured in a saying popular among advocates of regenerative agriculture, “It’s not the cow, it’s the how” [21,22]. This group presents compelling scientific evidence to support their argument, leading them to a conclusion that starkly contrasts with those advocating for the de-animalization of our food systems. According to this vision of a “clean cow future” [23], livestock must be included in the agrifood equation if we hope to step back from the ecological cliff, with bovines playing a crucial role.

Leveraging data from fifty-eight individuals committed to sustainable protein transitions, including a group of small-scale regenerative farmers with non-normative identities, I examine the “no cow” and “clean cow” framings by analyzing the type and scope of change assumed. The data suggest a diversity of concerns within and across this simplistic dichotomous framing, prompting me to consider the positionalities involved. The argument ultimately favors “clean cow” framings, as determined by the scope of the social change imagined. However, there is notable heterogeneity within these “clean” framings, which I highlight to explain why support for this frame should be conditional. The data presented indicate the need for caution before embracing sustainable protein framings from upstream actors, whether of the “no” or “clean” variety, i.e., from those closely tied to corporate interests, government sponsors, and regulating bodies. The differences suggested by the dichotomous “no versus clean” framing obscure shared concerns across these networks, which, if not adequately addressed, risk perpetuating inequities and injustices in sustainable protein futures dominated by “clean cow” frames.

In the next section, I outline the sustainable protein debate, at least as conventionally conceived, which is a valuable exercise for those new to the topic. This is followed by a section introducing and reviewing frame theory, which I leverage in the Findings Section. The Discussion and Conclusion Section focuses on integrating theory and data as I elaborate on the abovementioned argument from the perspective of next steps, both in terms of activism and social mobilization but also future research.

2. Setting the Stage: Landscape Conditions

The alternative protein industry raised $1.6 billion in global investments in 2023, with an additional $299 million raised in the first quarter of 2024 [24]. These investments are recorded across three protein platforms: plant-based, fermented, and cultivated. The reader may refer to Table 1. While this amount is notably less than the $5.1 billion raised in 2021, a record year of investment for the industry [24], market conditions remain favorable. One forecast for alternative protein anticipates global growth of this industry at 9.9 percent between 2024 and 2029 [25].

Table 1.

Plant-based, fermented, and cultivated alternative proteins briefly explained.

Meat consumption continues to rise globally. A recent analysis revealed that per capita global consumption has reached 34 kg, an increase from 29.6 kg in 2000, though significant variability exists within this global average [26]. In this analysis, the most notable increases in consumption occurred in countries below the 2000 world average figure of 29.6 kg per capita, such as Russia, Vietnam, and Peru. More modest gains were observed in South American countries (Brazil, Argentina, Chile, and Colombia), where meat consumption was significantly above average in 2000 and remains so today. Meanwhile, six countries have experienced declines in total meat consumption since 2000, with the most significant decreases seen in New Zealand (from 86.7 kg per capita in 2000 to 75.2 kg per capita in 2019) and Paraguay (from 53.5 kg per capita in 2000 to 39.5 kg per capita in 2019) [26].

“It’s not the cow, it’s the how” is a well-known phrase among those aiming to revitalize the image of animal agriculture, including its larger-scale practices. While this group criticizes intensive livestock production, they believe extensive and rotational grazing has the potential to be scaled up [27]. According to this community, bovines (e.g., cows) and/or other large herbivores are regarded as “keystone species” that have thrived for countless generations, particularly in the U.S.—the bison, which once numbered in the tens of millions in the early 1800s, serves as a famous example. They cite ancestral grazing as a key reason the world’s richest soils are found in certain areas [22]. Commonly referred to as “regenerative” (including regenerative management, ranching, farming, etc.), research highlights how these practices, which combine ancestral wisdom and modern science [23], contribute to restoring soil health, enhancing biodiversity, improving water quality, and sequestering carbon [28,29,30]. Table 2 briefly overviews several key concepts and principles in regenerative ranching.

Table 2.

Some key principles in regenerative ranching.

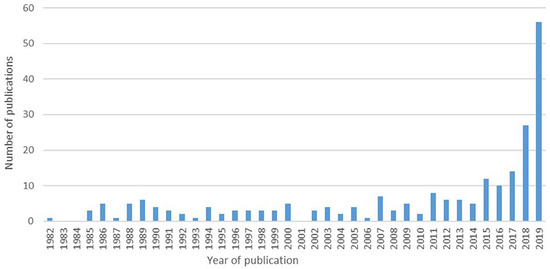

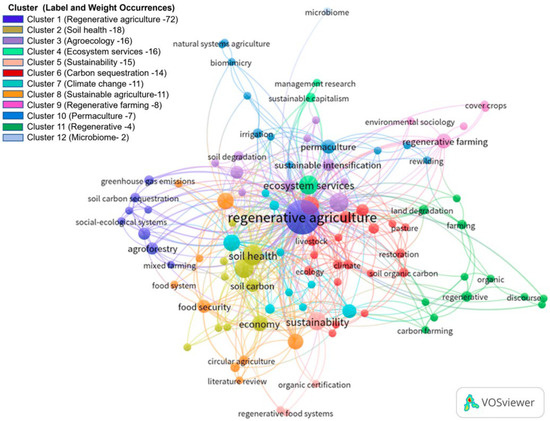

Refer to Figure 1 for evidence of the growing focus on regenerative farming practices in the peer-reviewed literature. This figure is based on a systematic review of research on “regenerative agriculture” published between 1982 and 2019 [36]. Additionally, we can examine these texts. Figure 2 is the result of a bibliographic analysis conducted with VOS Viewer, analyzing 240 peer-reviewed articles on “regenerative agriculture” [37]. This image organizes 103 keywords into 12 distinct clusters based on their co-occurrence. Although the clusters may be difficult to distinguish in grayscale, what is important here is the presence of the keywords and the identified clusters. Indeed, considering the present and absent keywords sets the stage for an analysis when reviewing the study’s findings.

Figure 1.

“Number of research articles that used the term “regenerative agriculture”, from 1982–2019” (Open Access article/image: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/sustainable-food-systems/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2020.577723/full?ref=rewildingmag.com) (accessed on 15 February 2025).

Figure 2.

“Co-occurrence density visualization of keywords from 240 papers on regenerative agriculture” (Open Access article/image: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/15/22/15941) (accessed on 15 February 2025).

3. Framing Transitions

Frame theory originated over fifty years ago [38,39] and continues to be widely applied, particularly in agrifood [40,41] and sustainability studies [42,43]. The concept of “framing” arises from the understanding that individuals are sense-making beings. In this process, we highlight specific signals that resonate with our identity, social networks, social location, positionality, and other related factors, implying that other elements may be minimized or even entirely concealed. As Entman [44] (p. 52) states, “to frame is to select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating context, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation for the item described”.

Frame theory is particularly valuable for understanding why social change and collective mobilizations manifest in certain forms [45]. Issue framing underpins all transitions and helps us comprehend the various perspectives, competing evaluations of trade-offs, and differing views of what exists and what ought to be. By employing frames, actors can highlight and ultimately preserve, protect, and enhance the phenomena that matter to them. Thus, frames are considered to have diagnostic, prognostic, or action functions, which relate to how issues and their causes are interpreted, how and at whose expense and benefit they are anticipated to develop over time, and how they can be resolved, respectively [45].

Scale framing often constitutes a part of framing [46]. Scales are described as “the spatial, temporal, quantitative, or analytical dimensions used to measure and study any phenomenon” [47] (p. 218). Examples of scale framing include emphasizing global emissions when discussing climate change or highlighting the advantages of local food compared to Big Food. The latter example combines two scale frames: administrative (e.g., local/global) and operational (e.g., big/small). As Van Lieshout and colleagues [46] (p. 1) note, “It makes a difference in terms of actors, interests, and interdependencies whether problems are addressed at one scale level or another”, further stating that scale framing can also “legitimize the inclusion and exclusion of actors and arguments in policy processes”.

As mentioned in the earlier discussion of the “action function”, framing also affects the scope of change envisioned. Others have reinterpreted this insight through the weak/strong sustainability analytical framework [42,48]. As Huttunen et al. [42] (p. 2) explain:

“Weak sustainability maintains the possibility to solve environmental crisis within the current economic structures by creating win-win solutions accommodating economic and environmental sustainability. Strong sustainability demands more radical change: transforming current production and consumption systems. In transitions studies, a similar distinction has been proposed between sustainability transitions and transformations in transitions studies”.

Having set the stage both contextually and conceptually, I now turn to my research project, providing an overview of the methods used.

4. Methods: Data Collection, Coding, and Analysis

Data collection for this paper occurred from December 2022 to December 2024, during a period of significant economic turbulence (e.g., rising interest rates and energy prices) impacting the agri-tech sector [49]. The project commenced with semi-structured interviews of participants involved in regenerative ranching (e.g., researchers, VCs, practitioners, industry advocates) or the agri-tech alternative protein sector (entrepreneurs, VCs, sector observers, researchers, etc.). Respondents were identified through snowball sampling techniques and were initially recruited from personal networks and attending various sustainability-focused protein and livestock events in Colorado and California. This two-state focus primarily stems from convenience, given my extensive connections in agriculture, food, and agrifood tech in both locations. It is also important to note that California and Colorado are hubs of regenerative livestock farming and agrifood tech venture capital (VC) investment [50]. Overall, thirty-six individuals from this group were interviewed: 18 advocates of regenerative ranching and 18 participants in the alternative protein sector. The interviews concentrated on understanding the narratives, frames, values, and concerns associated with respondents’ views on “sustainable protein”. Enrollment was discontinued when theoretical saturation was reached, a practice applied in grounded theory to indicate when the emergence of themes, concepts, and connections across those concepts effectively comes to a standstill [51]. Each respondent determined the location of their interview to ensure that the site was convenient and comfortable for them. If respondents chose a public setting (like a café), steps were taken to ensure a private room could be reserved to maintain privacy.

While snowball sampling is used widely in the social sciences, researchers must be aware of its tendency to exclude. Snowball samples risk taking on the qualities (demographic characteristics, values, beliefs, etc.) of those initially recruited [51]. While the sample referenced in the prior paragraph (n = 36) was developed using multiple “snowballs” to avoid network homogeneity, it lacked the heterogeneity I am used to seeing at food system-related events that lean into the values of inclusivity and diversity. For instance, the sample was predominately white and well educated, and was solidly middle-class. (While I did not ask about individuals’ wealth or income, those interviewed in this initial sample were major landowners, investors, engineers, paid lobbyists, or agri-tech executives.) Moreover, a significant finding had come into focus even before reaching theoretical saturation, namely, that the “no/clean” distinct masks specific shared values across the sample of those thirty-six respondents. I had thus begun to look for ways to unpack these frames beyond whether someone had connections with, for instance, regenerative ranching or Silicon Valley. This led me to consider recruiting from networks with very different positionalities.

In line with grounded research methods [51], the decision was made to expand recruitment protocols to explore these previously untheorized tensions and relationships by examining positionalities beyond the “no/clean” dichotomy. This included recruiting from regenerative farming networks that considered sustainability—and presumably sustainable protein—through a lens of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). Earlier, I mentioned recruiting from “various sustainability-focused protein and livestock events in Colorado and California”. It became clear that while these events were visible and well attended, they seemed less inclined to engage with the concerns of food justice activists who prioritize issues related to food and land access, anti-racism, and food system fairness and tackle issues through collective mobilization (food/land cooperatives, activism, etc.) rather than relying solely on market- or innovation-based solutions. Consequently, I reached out to regenerative and agroecological farming networks with a significant percentage of individuals who self-identified as persons of color, disabled or differently abled, and/or members of the LGBTQIA+ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer/Questioning, Intersex, Asexual) community. Many individuals from these networks were also first-generation farmers. By leveraging connections with the organizers of the 2023 Colorado Food Summit, who provided travel grants and other resources to subsidize participation in hopes of creating a diverse and inclusive event, I was able to connect with these networks, identify potential participants, and initiate new “snowballs”.

Twenty-two individuals were recruited to participate in focus groups during the two-day 2023 Colorado Food Summit. These focus groups engaged participants in discussing their values and concerns about regenerative ranching and agroecological farming. Each focus group lasted approximately 90 min. These sessions allowed me to build rapport with participants, which later enabled me to interview each individually via virtual media platforms. The individual interviews also lasted, on average, for 90 min. Qualitative researchers investigating historically marginalized groups are increasingly incorporating methodological techniques to build rapport, enhance recruitment and trust, improve data validity, and establish long-term connections [52], as opposed to viewing interview encounters as one-offs—a principle known to breed distrust among these groups toward researchers [53,54,55]. This reflects a broader shift in critical research methods, as the field is influenced by anticolonial and indigenous methodologies [53,54] and participatory and community-based research techniques [55].

I facilitated three focus groups to accommodate respondents’ schedules. Given the number of individuals in each focus group and the assurance that the event would last about 90 min, there was only time to ask a couple of questions. It should be remembered that these events not only aimed to collect data but also sought to build rapport to encourage participation in a later personal interview. Focus groups began with participants introducing themselves and describing their farming operations, followed by a discussion of their views on sustainable proteins. In the remaining time, focus group participants reflected on what “sustainability” means to them and how this definition shapes their views on protein production and consumption.

Table 3 presents the interview protocol utilized for all semi-structured interviews. The listed questions serve as entry points—hence, the semi-structured designation. With nearly thirty years of experience conducting qualitative interviews, I drew upon that training to ask follow-up questions that explored themes, concepts, and connections as they emerged during the interview process.

Table 3.

Semi-structured interview protocol.

All respondents were also asked to “provide in no particular order five keywords that come to mind when thinking about sustainable protein and the practices and processes that support and explain it”. I then suggested that respondents could “talk through a concept, principle, practice, or ideal if they found it too constraining to identify the ‘right’ word first”. Before sharing their terms, respondents were informed that they would be allowed to explain their choices in case some felt compelled to state only self-explanatory terms. Allowing participants to clarify their word choice proved especially beneficial when I later standardized terms, particularly when the same meaning was associated with different labels. Only keywords with a frequency of two or more were inputted into word cloud-generating software to enhance the image’s readability. DePaolo and Wilkinson [56] (p. 39) observe that “the effectiveness of the word cloud is theoretically grounded in the learning model”, highlighting the value of visualization tools to communicate ideas and concepts and thus convey meaning. While less well suited for making explanatory conclusions, these images can be “useful as a starting point or [as a] screening tool for large amounts of text data, whether related to assessment or not” [56] (p. 39).

To further sensitize myself to the data, I attended several events related to the alternative protein industry, including two pitch nights, two demo days, and four conferences. I also observed several regenerative ranching events, including five field demonstrations and three conferences. I took extensive field notes at each event. Finally, I reviewed over one hundred marketing and technical reports on protein and livestock production.

All interviews were recorded, and the recordings were reviewed immediately after each session, as were the notes taken from the practices described in the previous paragraph. This approach generated further notes about concepts identified and relationships between concepts, a method known as “open coding” [57]. After collecting the data, I transitioned to “focused coding” [57], which involved curating and reorganizing themes, concepts, and relationships into meta-themes while deeply engaging with the relevant literature—a process supported by the qualitative analysis software NVivo 14. This coding process resulted in the data being organized into four groups: (1) farmers/ranchers (clean cow); (2) lobbyists, federal sponsors, and VCs (clean cow); (3) engineers, scientists, and lab technicians (no cow); and (4) lobbyists, corporate executives, and VCs (no cow). Table 4 provides demographic information for these four groups, as identifying them is essential for constructing a conceptual argument later. Two reviewers had questions about the table’s inclusion of gender and sexual orientation. One asked whether respondents found this query “puzzling”, given the research’s focus on protein transitions. The consent forms described the study as “sociological” and focused on studying social and cultural variables. This might explain why respondents appeared comfortable sharing, even when confronted with questions that might seem personal and only tangentially related to protein transitions, e.g., race/ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation. The other reviewer asked if I could spend more time discussing these variables. The survey did not directly investigate how or if, for instance, gender or sexual orientation relates to sustainable protein frames, so I do not feel comfortable extending the findings to such topics. Yet, I believe that asking inclusive questions about gender and sexual orientation contributes to building trust and rapport with participants, especially among historically marginalized groups, as these demographic questions help to “normalize” historically non-normative identities [54,55].

Table 4.

Demographic information for four conceptually relevant groups, n = 58.

5. Word Clouds: Diversity Within and Across the “No” vs. “Clean” Debate

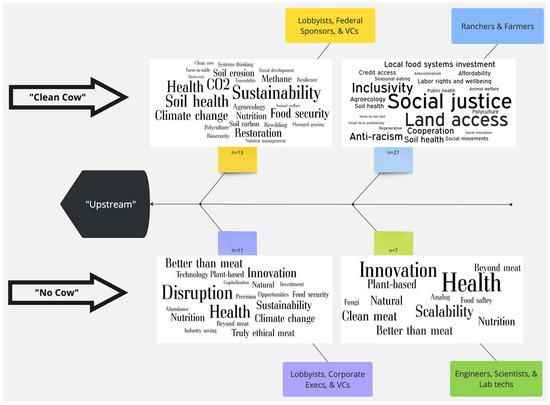

I begin by reviewing the word clouds generated from the earlier exercise. Figure 3 illustrates these images; each word’s size reflects its frequency of mention. Those associated with so-called “clean cow” networks appear above the line, indicated on the left by the term “upstream”, while those representing “no cow” actors fall below it. Terms are further categorized according to the roles outlined in Table 4. Those unfamiliar with the downstream/upstream terminology refer to the two ends of a value chain [58].

Figure 3.

Word clouds for varied positions across ‘no’ and ‘clean’ cow networks.

The image creates the impression that terms above the line differ significantly from those below it. First, consider the terms used by upstream actors involved in regenerative ranching networks, which encompass concepts related to air (e.g., “CO2”, “methane”, “climate change”), landscapes (e.g., “restoration”, “managed grazing”, “rewilding”, “biodiversity”), and soils (e.g., “soil erosion”, “soil health”, “soil carbon”). This group also claimed to prioritize what could be considered holistic thinking, as indicated by terms like “systems thinking”, “polyculture”, and “agroecology”. Additionally, terms related to well-being were frequently expressed, such as “food security”, “health”, “nutrition”, and “rural development”.

Conversely, upstream actors promoting alternative proteins conveyed distinctly different beliefs, concerns, and values. Their narratives were influenced by techno-optimistic, if not outright utopian, visions, as evident in terms like “innovation”, “technology”, “disruption”, “capitalization”, “better than meat”, “beyond meat”, and “opportunities”. Interestingly, this techno-optimism sometimes rooted itself in the non-technological—specifically, in the “natural”. The significance of this co-occurrence reflects the aim of earlier GMO (genetically modified organism) advocacy, namely, to prevent these foods from being viewed as “unnatural” [59]. Guthman and Biltekoff [60] (p. 1583) note something similar in their analysis of alternative proteins within the context of the “imperatives of Silicon Valley innovation”. At one point in their article, they emphasize a type of ontological politics characterized by “promissory narratives”, which they argue “are critical to convincing funders, consumers, regulators, and broader publics of the food-ness of stuff otherwise seen as non-food or acceptable as meat, given contradictory regulatory and cultural understandings of what meat is” [60] (p. 1584). The concept of promissory narrative also aids in clarifying terms like “beyond meat”, “better than meat”, and “truly ethical meat”—to quote an executive, “Our meat is very much meat, but without the baggage that comes with animal-based protein” (Alternative Protein [AP], upstream #13).

Without undermining these differences, upstream actors across the clean/no divide also used terms that indicated shared concerns. However, emphasizing these shared frameworks requires us to rethink our approach to word clouds. Word clouds are typically investigative tools that focus on presences, namely, the words mentioned and their frequency. Nevertheless, these data visualization tools also highlight absences, especially when multiple images are involved. Now, I concentrate on the word cloud created by “ranchers and farmers”, acknowledging that this group drew primarily from regenerative livestock networks composed of historically marginalized individuals.

Unlike the other generated images, the “ranchers and farmers” cloud features words that connect to the most frequently mentioned term: social justice. While I will discuss this further in the next section, the words in the image also express a need for systemic change. While other word clouds subtly incorporate humans and social issues in the background (as indicated by terms like “agroecology”, “systems thinking”, “health”, and “sustainability”), ranchers and farmers explicitly recognized social justice (i.e., “social justice”) and strategies to achieve it (e.g., “anti-racism”, “social movements”, “anticolonialism”) during the word cloud exercise. The reasons for this will be clarified shortly.

Unfortunately, we must be cautious when interpreting word cloud data in isolation. While they can help make higher-level observations [56], word clouds are most effective when combined with contextual data. The following section incorporates these data into the analysis.

6. Competing Frames

This section explores two themes. Each theme reveals presences and absences in the word clouds while highlighting pertinent beliefs, values, and concerns. The section enriches elements already presented by the word clouds while significantly deepening the analysis. These themes clarify why the competing sustainable protein frameworks do not cleanly separate across the no/clean divide, highlighting notable divergences within clean cow networks.

6.1. “Government” Frames: Individual or More-Than-Individual Liberties

Respondents were unable to agree on the role of government and regulation while articulating their vision for sustainable agrifood futures. One commented that “I think that most people you interview will say government regulation is locking out the type of change they hope to see in our food system” (AP #12). This comment came from a food scientist working on cultured meat during the early stages of fieldwork. Their critique, to be clear, was not that food regulators should overlook issues of food safety. Rather, their concern focused on labeling, where “the government interferes by telling us we can’t label meat ‘meat’ or milk ‘milk’”. They later expressed frustration, envisioning a scenario: “Christ, can you imagine what it would do to consumer and investor confidence if we’re suddenly told we have to use a term like ‘cultured meat-like product’ on our packaging?”

On 30 January 2024, the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives introduced the Fair and Accurate Ingredient Representation (FAIR) on Labels Act of 2024. As of early 2025, FAIR remains stalled in the committee stage and aims to establish comprehensive new labeling requirements for alternative products in ways that benefit the livestock and dairy industries [60]. Additionally, several state-level bills are challenging these self-identified “disruptors”. For instance, a bill introduced in Florida in November 2023 prohibits the manufacturing, sale, and distribution of cell-cultured meat in the state [61]. Among all respondents, serious concerns arise about “government capture by the livestock industry, which, let’s not forget, is a multibillion-dollar-a-year industry” (Regenerative Rancher [RR] #3). JBS, the world’s largest meat processing company, reported revenue surpassing USD 142.52 billion in 2024 [62]. Respondents cited instances of this regulatory (i.e., government) capture [63], emphasizing the significant support given to intensive livestock-related industries through subsidies, along with the underfunding of agencies responsible for their regulation, such as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA).

Ranchers and farmers described this capture while discussing how one-size-fits-all regulatory policies “regulate” differently depending on the size of the operation in question. As one explained, “Regulations at face value are supposed to reign in ‘Big Livestock’, making sure they don’t get too big and to make sure the market remains competitive. But what they actually do is help lock in their market dominance” (RR#11).

This quote highlights a well-known critique of government regulation by supporters of local food and smaller-scale agriculture [64,65,66]. Food safety rules and environmental regulations that aim to be scale-neutral—treating all farms equally—are far from equitable because they ignore the costs these policies impose on smaller food producers. For instance, due to structural changes in the meat processing industry, many ranchers and poultry farmers must transport their animals to distant USDA-approved facilities for slaughter and processing. This cost is more manageable for larger producers who benefit from transportation economies of scale. Additionally, concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) are typically located near processing plants due to the recognition that transporting animals can lead to weight loss and death. In summary, the core of these critiques regarding regulatory capture from respondents centers on how the government directly prevents individuals, individual farms, and ranches, as well as tech firms and start-ups, from reaching their potential by implementing policies that, in practice (if not in name), favor the intensive livestock status quo.

Extensive literature examines how government regulation benefits and harms various actors within agrifood systems [63,67,68]. I raise this topic not to revisit familiar ground but to introduce a parallel set of concerns that can be illuminated through a series of questions. What are the fundamental assumptions driving this apprehension regarding government intervention? Intervening on what?

We can address these questions by examining the following representative quotes from upstream actors in the “no” and “clean” cow networks.

Quote 1: “We need to unleash the entrepreneurial spirit and not stifle it with arbitrary rules and regulations” (AP, upstream #6).

Quote 2: “Is it too much to ask, to sell directly to consumers and not have these onerous barriers standing in my way that make it harder for me to do what the JBSs [JBS Foods] of the world can do, which is sell meat” (RR, upstream #2).

Quote 3: “This isn’t a radical notion but based on Jeffersonian [Thomas Jefferson] agrarianism: land ownership and access, economic independence, and individual rights and freedoms” (RR, upstream #14).

Quote 4: “I’m not saying I want the government to prop up cultured meat. Being a realist, I know that isn’t happening. […] Just give us room to operate in the market. Treat us the same as any other market actor” (AP, upstream #13).

I want to assign a name to something that connects these quotes and then elaborate on it: privilege. This privilege allows certain social groups to experience freedom in go-it-alone entrepreneurialism and Jeffersonian agrarianism. For instance, as mentioned in Quote 2, upstream actors in the clean cow camp highlighted farm-to-fork and direct-to-consumer arrangements in their discussions about sustainable protein futures. These strategies were essential for helping to “wrest food systems from the tight grip of corporations” (RR, upstream #2). But what about the even tighter grip that market-based agrifood imaginaries held on those interviewed?

Upstream actors connected to regenerative ranching networks often discussed issues, such as supply and demand as a price-setting mechanism, consumer choice as a form of activism, and the significance of individual land ownership, all without questioning the reasoning behind these concepts. To reference a well-known quote often attributed to philosopher Fredric Jameson, I suspect that upstream clean cow respondents would find it easier to envision the end of the world than the end of capitalism. After all, frameworks involving “market-based social change” are, by definition, transitional rather than transformative—those who control the former need not be concerned about the extent of the latter [69,70,71].

This observation highlights the differences in how regenerative farmers and ranchers discuss the government compared to other groups, undoubtedly linked to their historically marginalized positions. The following quote comes from Ned, an African American farmer who supplies a food cooperative in the greater Denver area.

“It’s a total hustle for those wanting to sell direct-to-consumer. If you want to farm on a smaller scale, you better be ready to carve out thirty-four hours in a 24-h day. […] You are responsible for marketing, which means spending too much time accommodating consumers who will only buy from you if it’s convenient, like Saturday mornings. […] And somehow, you must find a way to compete against competitors who sell produce that is mostly identical to yours. […] Oh, and you’ll never make enough to pay others, so you need to do all this by yourself—plus grow the food. [...] That still doesn’t always pay the bills. So, you try to find time to do other stuff to generate revenue, like agritourism or catering” (RR #22).

Notably, this comment followed Ned’s statement that “we need to rethink the role of government when discussing the type of change needed to make food systems sustainable and just”. His argument, echoed by others in this group, can be summarized by referencing the commonly used treadmill metaphor in critical scholarship to illustrate how markets prioritize efficiency, scale, and profit maximization [72]. If the treadmill is “spinning” at an unsustainable pace, indicated by market hyper-competitiveness that favors those with resources, “does it matter”, quoting Ned again, “to make changes at the margins, like having food cottage laws, when the system itself is broken?” The Colorado Cottage Foods Act, enacted in 2012, permits individuals within the state to sell specific non-potentially hazardous foods directly to consumers without a license or inspection.

I began this subsection by emphasizing that respondents could not agree on the role of government and regulation. Despite this difference, there was substantial consensus on the necessity of freeing the individual. In other words, there was disagreement about whether the government undermined individual liberties or, in certain situations, could enhance them. However, all respondents, except for marginalized regenerative farmers and ranchers, firmly believed that individual liberties—a fundamental aspect of Jeffersonian agrarianism [73] and entrepreneurialism [74]—were intrinsic elements of their respective sustainable protein frameworks.

This contrasts with what I heard during focus groups and interviews among those with non-normative identities. They presented a competing political ontology. Specifically, they were skeptical of the idea of an “autonomous subject”, which has long been a core principle in Western philosophy, political theory, and economics (i.e., homo economicus) [75]. Instead of viewing it as a brute fact, many in this group believed this framing was a historical, European (read: white) fiction.

The representative quotes below illustrate this alternative political ontology, which I term autonomy-as-interdependence. Additionally, it is important to note how specific terms from their word cloud, like “anti-racism” and “anticolonialism”, echo throughout these statements.

One person remarked that “I wish I was in a position where I could flourish by being left alone. […] Here’s the thing: being a queer Black man, that’s not how it is for me. I’m not normal. I’m an anomaly and, for some, an abomination. […] Those who tout the need to protect individual liberties don’t realize the privilege that goes into thinking that. If I had to go it alone, I’d get devoured” (RR #32).

Another person commented as follows: “‘Oh, we’ve got to save the family farm!’ There’s this idea out there that we need to protect farm independence, ignoring how this construct is rooted in historical racism and colonialism. Hello, Jefferson was a slave owner! […] Not everyone is lucky enough to inherit land or have good credit or the means to develop good credit. […] Fuck ‘independence’. We’re stronger together” (RR #30).

6.2. “Change” Frames: Transition or Transformation

This brings me to the second theme, which relates to how respondents framed “change”. At one level, the types of agrifood futures described could not be more different. One is based not only on animal agriculture but also on land use, where animals are managed extensively, contrasting with the intensive model employed in conventional livestock production systems. Alternatively, the “no cow” frame emphasizes the de-animalification of protein production. Interestingly, this dichotomy serves as a frame, highlighting certain elements to enhance contrasts while similarities remain in the background. Including marginalized farmers and ranchers helped reveal otherwise masked shared concerns, as they discussed a distinctly different kind of change that needs to occur.

Prioritizing “the collective” over “the individual” as the unit for situating action expanded the possibilities and probabilities perceived by farmers and ranchers, as illustrated by the following quote regarding property rights. Additionally, let us reflect on the scope of the change described in the following:

“We lack imagination and will when we talk about the role of government, like all the energy directed at debating subsidies and the commodities targeted. […] Yes, we need to involve the government because we need to change the rules of the game profoundly and ‘the government’ is those rules. […] The very idea of private property needs to be revisited. Think of how we could transform community food systems if we shared things collectively rather than needing to own every darn thing, big or small things—everything—individually”. (RR #20)

Evidence of transformational (as opposed to transitional) change within the “ranchers and farmers” group can also be discerned from their word cloud, which features terms like “seasonal eating”, “nose-to-tail diet”, and “social innovation”. One participant described the latter as “prioritizing the creation of new ways of living together that ultimately take us beyond systems that rely on locking people into debt and that reward hyper-competitiveness” (RR #21). Although it may seem that upstream actors in the regenerative sample also pursued transformational change, as indicated by the frequency of terms in the word cloud such as “health”, “sustainability”, and “food security”, the qualitative data present a different narrative. The metric or quantitative focus of these concepts, as described in the following quotes, undermines claims about systemic change [76,77].

On respondent remarked that “We’re leading the charge, creating the next generation of carbon cowboys—ranchers who know how to restore soil health by building soil structure and locking away CO2, who produce optimal feed conversion ratios, and who run profitable operations” (RR, upstream #10).

Another commented that “The protein from regenerative land management is healthier, and I have the data to provide it, in terms of good and bad fats, amino acid profiles, its micronutrients. It’s just better” (RR, upstream #14).

A closer inspection of these terms reveals the presence of epistemic politics through the subtle creation of blind spots. Much of the sustainable protein debate, along with the frames employed, particularly by upstream actors, exemplifies apolitical ecologies [78]. For instance, references to CO2 and greenhouse gases dominate many of these discussions—note how clean cow ranchers are frequently labeled “carbon cowboys” in the literature [79]. Similarly, the frames of “health” and “nutrition” pertain to quantifiable properties, i.e., the ideology of nutritionism [80]. In other words, sustainable protein frames often fetishize narrow features—such as greenhouse gases, metrics of soil health, or micro/macronutrients. It is difficult to envision transformative “change” when relying on metrics established by the (problematic) status quo.

In arguing that upstream actors in the “no” and “clean” camps share concerns, I do not intend to diminish their differences. For instance, what would happen to the ranching livelihoods and rural communities erased by the “no cow” narrative? As advocates of regenerative ranching frequently informed me, a “clean cow future” would revitalize those family farms, ranches, and communities (RR, upstream #8). This was stated by a lobbyist. However, in these instances, respondents permit terms like “revitalize” (or, for that matter, “health”, “sustainability”, or “rural development”) to do much of the work, primarily by emphasizing some aspects while downplaying others, which is typical of empty signifiers [81]. Systems can be revitalized without undergoing substantial change. Yet, significant change is what we need, according to the farmers and ranchers interviewed—a kind of change that entails reimagining the political economy, biased cultural constructs (such as autonomy-as-autonomy versus autonomy-as-interdependence), and laws that institutionalize inequities (e.g., the codification of private property).

7. Discussion and Conclusions

The previous sections illustrate the significant stakes involved in discussions about sustainable protein futures, extending beyond those implied by the clean/no dichotomy. We need to explore the underlying frames more thoroughly, including how these frames vary within the networks. This exploration highlights differences where they are expected, particularly regarding the competing perspectives on whether protein systems and agriculture should undergo de-animalization. Additionally, the data emphasize another point of contention between frames that uphold Western, liberal, and capitalistic ontologies, which advocate for concepts like individual autonomy, freedom, and responsibility, and those grounded in more-than-individual and diverse economies. The former focus on transitions, while the latter support futures achievable only through transformations [82,83].

Transition-oriented frames exhibit all the characteristics of a “merely movement”. The term “merely movement” originates from Nancy Fraser’s [84] discussion on climate politics and her critique of how environmental struggles are often perceived as “merely environmental” due to their failure to connect with issues such as class struggles, anti-racism, and hegemonic power. As Fraser [84] (p. 96) states:

“[Environmental struggle] must connect its ecological diagnosis to other vital concerns—including livelihood insecurity and denial of labor rights; public disinvestment from social reproduction and chronic undervaluation of care work; ethno-racial-imperial oppression and gender and sex domination; dispossession, expulsion and exclusion of migrants; militarization, political authoritarianism and police brutality”.

How can we escape the “petty reform incrementalism” [85] (p. 468) that dominates transition-oriented sustainable protein frameworks? We can do this by avoiding merely local, agrarian, urban, environmental, carbon, consumer, and similar movements and engaging with struggles that reflect the concerns of social bodies characterized by non-normative positionalities. It is also accomplished by refraining from immediately asking about market mechanisms—i.e., merely market-based social change. Historically marginalized groups, such as those recruited initially through focus groups, often lack buyer power, which is one reason they have remained marginalized in a society that prioritizes market-based social change. Transitions to more-than-merely sustainable protein require social innovations, not just (merely) technical ones.

One immediate social innovation could involve finding ways to normalize greater reflexivity and, thus, inclusivity in spaces where sustainable protein transitions are discussed and debated. Recall that I adjusted my initial research sampling techniques due to the exclusion of certain groups from these spaces. I knew from experience that smaller-scale regenerative farmers care about sustainable protein transitions just as much as large-scale ranchers and those from the agri-tech sector. Their absence from the high-profile events I had been sampling was significant. Therefore, I adjusted my recruitment protocol to include these otherwise marginalized perspectives. The importance of having these voices contribute to the data cannot be overstated, as they remind us that who is included in these debates shapes the framing of what is at stake. Had I excluded these voices, I would have perpetuated an error of omission, a mistake I worry is common in many of the “mainstream” sustainable protein discussions.

I now reflect on what I would have done differently, though I realize that some of these “research limitations” stem from “limited research resources”. I could have been more intentional about ensuring an inclusive sample. This would have included diverse socio-economic positionalities and sample sets for each of the identified alternative protein categories, namely, plant-based, fermented, and cultivated. As presented, the data combine these different categories, discourses, and practices under the same “no cow” frame. An opportunity is missed to understand how networks, values, and beliefs vary within alternative protein networks. This study also overlooked respondents’ identities as protein consumers. It would be interesting to investigate whether the highlighted downstream frames align with upstream frames, recognizing that food consumption and procurement are closely tied to other identities, such as being a “good mother” [71] or “caring parent” [86].

Additionally, anti-speciesist and animal welfare values motivate some to oppose and act against the production of animal-based proteins [87,88]. Previous research has connected racial and species justice, viewing both as interconnected [89,90]. These perspectives did not emerge as themes during the coding process. This does not imply they lack relevance in these debates. In hindsight, I should have included a section in the interview protocol that explicitly addressed these values. Furthermore, I could have been more intentional with my recruitment by ensuring I included “snowballs” that connected with individuals who prioritize these values.

Finally, a reviewer’s comment reminds me that the paper is silent about specific topics that would interest many readers. These gaps say less about limitations per se—after all, no paper can cover everything—but hint at the other vital questions that underpin our quest to transform agrifood systems. For instance, readers will be disappointed if they seek clarity on the role of these two frameworks (“no” versus “clean”) in global food security or if they hope to find insights into policy mechanisms that support affordable, equitable, and inclusive protein transitions. However, given what we know about the importance of place and situatedness in agriculture [91], I am unsure whether such topics should be addressed in the limited space of a research article. Context matters when discussing global food security and sustainable protein [91], so it is significant whose voices and concerns are prioritized in these discussions. I hope readers view these limitations and blind spots productively as scholars studying sustainable protein transitions seek new research questions to explore.

In conclusion, this paper explores competing sustainable protein discourses and the values and associations upon which they are built. The literature on socio-technical change provides valuable insights on implementing sector-level “just transitions”—such as energy [92], agrifood [42], automation in agriculture [93], and electric vehicles [94]. What we risk overlooking in these discussions are the deeper background assumptions. These assumptions are so ingrained in our collective psyche, discourses, and practices that they rarely emerge in studies examining sustainable protein transformations.

It is difficult to overstate the importance of including non-normative positionalities from regenerative and agroecological networks in this study’s sample. Insights from these perspectives create contrasts, highlighting elements that might go unnoticed. The findings remind us to consider what is at stake in these debates while recognizing that the contributors to the competing frameworks shape what those futures celebrate, understanding that these framings extend far beyond the narrow “no” vs. “clean” dichotomy. The findings also serve as a call to ensure that these debates are not dominated by those closest to the purse strings, such as VCs and individuals with corporate and government ties, whose “upstream-ness” implies the presence of background assumptions and concerns that other positionalities actively struggle against.

Funding

The research was supported by multiple sources: the Swedish Research Council–FORMAS [grant number 2023-01818], the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture [grant number NIFA-COL00725USDA], and the CSU Office of Engagement and Extension.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Colorado State University (protocol code 2279 and 6 May 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- FAO. Livestock’s Long Shadow; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2006; Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/a0701e/a0701e00.htm (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Breakthrough Institute. Livestock’s Global Carbon Footprint; Breakthrough Institute: Oakland, CA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.datawrapper.de/_/VMdRe/ (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Cheng, M.; McCarl, B.; Fei, C. Climate change and livestock production: A literature review. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Pathways Towards Lower Emissions; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2023; Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/cc9029en (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Gu, X.; Drouin-Chartier, J.P.; Sacks, F.M.; Hu, F.B.; Rosner, B.; Willett, W.C. Red meat intake and risk of type 2 diabetes in a prospective cohort study of United States females and males. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 118, 1153–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, J.; Alexander, P.; Taillie, L.S.; Jaacks, L.M. Estimated effects of reductions in processed meat consumption and unprocessed red meat consumption on occurrences of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, colorectal cancer, and mortality in the USA: A microsimulation study. Lancet Planet. Health 2024, 8, e441–e451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escarcha, J.F.; Lassa, J.A.; Zander, K.K. Livestock under climate change: A systematic review of impacts and adaptation. Climate 2018, 6, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; He, X.; Feng, Y.; Wang, W.; Chen, H.; Gong, M.; Liu, D.; Clarke, J.L.; van Eerde, A. Pollution by antibiotics and antimicrobial resistance in livestock and poultry manure in China, and countermeasures. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauvain, P. Apocalypse Cow: How Meat Killed the Planet. Channel 4, January 8th, UK. 2020. Available online: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt11652038/ (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Roy, E. Fake Chews? New Zealand MP Fears ‘Existential Threat’ of Synthetic Burgers, The Guardian, 4 July 2018. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jul/05/new-zealand-fake-burger-existential-threat-red-meat (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Liu, J.; Chriki, S.; Kombolo, M.; Santinello, M.; Pflanzer, S.B.; Hocquette, É.; Ellies-Oury, M.P.; Hocquette, J.F. Consumer perception of the challenges facing livestock production and meat consumption. Meat Sci. 2023, 200, 109144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryant, C.; Barnett, J. Consumer acceptance of cultured meat: An updated review (2018–2020). Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rombach, M.; Dean, D.; Vriesekoop, F.; de Koning, W.; Aguiar, L.K.; Anderson, M.; Mongondry, P.; Oppong-Gyamfi, M.; Urbano, B.; Luciano, C.A.G.; et al. Is cultured meat a promising consumer alternative? Exploring key factors determining consumer’s willingness to try, buy and pay a premium for cultured meat. Appetite 2022, 179, 106307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppes, S. Survey Tallies Consumer Attitudes Toward Lab-Grown Meat Alternatives; Purdue University Press: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.purdue.edu/newsroom/2024/Q2/survey-tallies-consumer-attitudes-toward-lab-grown-meat-alternatives/ (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Lehnis, M. Breaking Barriers: Cultivated Meat Company Achieves Price Parity, Making Sustainable Eating Accessible. Forbes. 19 December 2023. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/mariannelehnis/2023/12/19/breaking-barriers-cultivated-meat-company-achieves-price-parity-making-sustainable-eating-accessible/ (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Knuth, S. Green devaluation: Disruption, divestment, and decommodification for a green economy. Capital. Nat. Social. 2017, 28, 98–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gor, N. Berkeley Urges CalPERS to Divest from Industrial Animal Protein, Factory Farming Companies. Berkeleyside. 30 April 2021. Available online: https://www.berkeleyside.org/2021/04/30/opinion-berkeley-urges-calpers-to-divest-from-industrial-animal-protein-factory-farming-companies (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Elton, C. Scottish University Takes Meat off the Menu as Student Union Votes to Go 100% Vegan. Euronews. 29 November 2023. Available online: https://www.euronews.com/green/2022/11/29/scottish-university-takes-meat-off-the-menu-as-student-union-votes-to-go-100-vegan (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Oltermann, P. Berlin’s University Canteens Go Almost Meat-Free as Students Prioritise Climate. The Guardian. 31 August 2021. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/aug/31/berlins-university-canteens-go-almost-meat-free-as-students-prioritise-climate (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Hedberg, R.C. Bad animals, techno-fixes, and the environmental narratives of alternative protein. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1160458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkham, P. “It’s Not the Cow, It’s the How”: Why a Long-Time Vegetarian Became Beef’s Biggest Champion. The Guardian. 30 August 2021. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/food/2021/aug/30/its-not-the-cow-its-the-how-why-a-long-time-vegetarian-became-beefs-biggest-champion (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Rodgers, D.; Wolf, R. Sacred Cow: The Case for (Better) Meat: Why Well-Raised Meat Is Good for You and Good for the Planet; BenBella Books: Dallas, TX, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cusworth, G.; Lorimer, J.; Brice, J.; Garnett, T. Green rebranding: Regenerative agriculture, future-pasts, and the naturalisation of livestock. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2022, 47, 1009–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Good Food Institute. A Deeper Dive into Alternative Protein Investments in 2022: The Case for Optimism; Good Food Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; Available online: https://gfi.org/blog/alternative-protein-investments-update-and-outlook (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Markets and Markets. Market Research Report. Markets and Markets. June 2024. Available online: https://www.marketsandmarkets.com/Market-Reports/alternative-protein-market-233726079.html (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Whitton, C.; Bogueva, D.; Marinova, D.; Phillips, C.J. Are we approaching peak meat consumption? Analysis of meat consumption from 2000 to 2019 in 35 countries and its relationship to gross domestic product. Animals 2021, 11, 3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratton, C.; Strauser, J.; Jordan, N.; Jackson, R.D. Agroecological innovation to scale livestock agriculture for positive economic, environmental, and social outcomes. Environ. Res. Food Syst. 2024, 1, 013001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, C.D. How Biodiversity-Friendly is regenerative grazing? Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 9, 816374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spratt, E.; Jordan, J.; Winsten, J.; Huff, P.; Van Schaik, C.; Jewett, J.G.; Filbert, M.; Luhman, J.; Meier, E.; Paine, L. Accelerating regenerative grazing to tackle farm, environmental, and societal challenges in the upper Midwest. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2021, 76, 15A–23A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voisin, R.; Horwitz, P.; Godrich, S.; Sambell, R.; Cullerton, K.; Devine, A. What goes in and what comes out: A scoping review of regenerative agricultural practices. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 48, 124–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J.; Cain, M.; Pierrehumbert, R.; Allen, M. Demonstrating GWP*: A means of reporting warming-equivalent emissions that captures the contrasting impacts of short-and long-lived climate pollutants. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 044023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitloehner, F. The Bogus Burger Blame. 2021. Available online: https://clear.ucdavis.edu/blog/bogus-burger-blame (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Meinshausen, M.; Nicholls, Z. GWP* is a model, not a metric. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 041002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werth, S. The Biogenic Carbon Cycle and Cattle. CLEAR Center; University of California-Davis: Davis, CA, USA, 19 February 2020; Available online: https://clear.ucdavis.edu/explainers/biogenic-carbon-cycle-and-cattle (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Kelliher, F.; Clark, H. Methane emissions from bison—An historic herd estimate for the North American Great Plains. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2010, 150, 473–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, P.; Civita, N.; Frankel-Goldwater, L.; Bartel, K.; Johns, C. What is regenerative agriculture? A review of scholar and practitioner definitions based on processes and outcomes. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 577723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, S.L.; Thomas, D.T.; Anderson, J.P.; Chen, C.; Macdonald, B.C. Global Application of Regenerative Agriculture: A Review of Definitions and Assessment Approaches. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateson, G. Steps to an Ecology of Mind; Ballantine Books: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, E. Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Rust, N.A.; Jarvis, R.M.; Reed, M.S.; Cooper, J. Framing of sustainable agricultural practices by the farming press and its effect on adoption. Agric. Hum. Values 2021, 38, 753–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slätmo, E.; Fischer, K.; Röös, E. The framing of sustainability in sustainability assessment frameworks for agriculture. Sociol. Rural. 2017, 57, 378–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huttunen, S.; Tykkyläinen, R.; Kaljonen, M.; Kortetmäki, T.; Paloviita, A. Framing just transition: The case of sustainable food system transition in Finland. Environ. Policy Gov. 2024, 34, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, S.A. Just transition? Strategic framing and the challenges facing coal dependent communities. Environ. Plan. C Politics Space 2019, 37, 298–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entman, R.M. Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J. Commun. 1993, 43, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benford, R.D.; Snow, D.A. Framing processes and social movements: An overview and assessment. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2000, 26, 611–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Lieshout, M.; Dewulf, A.; Aarts, N.; Termeer, C. Do scale frames matter? Scale frame mismatches in the decision making process of a “mega farm” in a small Dutch village. Ecol. Soc. 2011, 16, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C.C.; Ostrom, E.; Ahn, T.K. The concept of scale and the human dimensions of global change: A survey. Ecol. Econ. 2000, 32, 217–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumeyer, E. Weak Versus Strong Sustainability: Exploring the Limits of Two Opposing Paradigms; Edward Elgar: Worcestershire, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Guthman, J.; Fairbairn, M. Speculating on collapse: Unrealized socioecological fixes of agri-food tech. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2024, 56, 2055–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marston, J. Data Snapshot: Almost Half of All AgriFoodTech VC Investment in the US Goes to California Startups. AFN. 12 April 2023. Available online: https://agfundernews.com/data-snapshot-almost-half-of-all-agrifoodtech-vc-investment-in-the-us-goes-to-california-startups (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Glaser, B.; Strauss, A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy-Macfoy, M. ‘It’s important for the students to meet someone like you.’ How perceptions of the researcher can affect gaining access, building rapport and securing cooperation in school-based research. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2013, 16, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A.G. Ethics, activism and the anti-colonial: Social movement research as resistance. Soc. Mov. Stud. 2012, 11, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, M.A.; Straka, S.; Rowe, G. Working across contexts: Practical considerations of doing Indigenist/anti-colonial research. Qual. Inq. 2017, 23, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeuw, S.D.; Cameron, E.S.; Greenwood, M.L. Participatory and community-based research, Indigenous geographies, and the spaces of friendship: A critical engagement. Can. Geogr. Géog. Can. 2012, 56, 180–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePaolo, C.A.; Wilkinson, K. Get your head into the clouds: Using word clouds for analyzing qualitative assessment data. TechTrends 2014, 58, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Newton, J.D.; Newton, F.J.; Rep, S. Evaluating social marketing’s upstream metaphor: Does it capture the flows of behavioural influence between ‘upstream’ and ‘downstream’ actors? J. Mark. Manag. 2016, 32, 1103–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schurman, R. Fighting “Frankenfoods”: Industry opportunity structures and the efficacy of the anti-biotech movement in Western Europe. Soc. Probl. 2004, 51, 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthman, J.; Biltekoff, C. Magical disruption? Alternative protein and the promise of de-materialization. Environ. Plan. E Nat. Space 2021, 4, 1583–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaulkin, S.; van Laack, R. Traditional Meat Industry’s Beef with Alternative Protein Continues with the FAIR on Labels Act. FDA Law Blog. 6 March 2024. Available online: https://www.thefdalawblog.com/2024/03/traditional-meat-industrys-beef-with-alternative-protein-continues-with-the-fair-on-labels-act/ (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- JBS. Revenue 2024. Available online: https://companiesmarketcap.com/jbs/revenue/ (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Lacy-Nichols, J.; Williams, O. “Part of the Solution”: Food Corporation Strategies for Regulatory Capture and Legitimacy. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2021, 10, 845–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolan, M. No One Eats Alone: Food as a Social Enterprise; Island Press: Washington DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Linnekin, B. Biting the Hands that Feed Us: How Fewer, Smarter Laws Would Make Our Food System More Sustainable; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Weil, S. Big-ag exceptionalism: Ending the special protection of the agricultural industry. Drexel Law Rev. 2017, 10, 183. [Google Scholar]

- Hüesker, F.; Lepenies, R. Why does pesticide pollution in water persist? Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 128, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandin, P.; Munthe, C.; Edvardsson Björnberg, K. Technology neutrality in European regulation of GMOs. Ethics Policy Environ. 2022, 25, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolan, M. Practicing social change during COVID-19: Ethical food consumption and activism pre-and post-outbreak. Appetite 2021, 163, 105206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinrichs, C. Transitions to sustainability: A change in thinking about food systems change? Agric. Hum. Values 2014, 31, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huddart Kennedy, E.; Parkins, J.R.; Johnston, J. Food activists, consumer strategies, and the democratic imagination: Insights from eat-local movements. J. Consum. Cult. 2018, 18, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnaiberg, A.; Pellow, D.; Weinberg, A. The treadmill of production and the environmental state. In The Environmental State Under Pressure; Mol, A.P.J., Buttel, F.H., Eds.; Elsevier North-Holland: London, UK, 2002; pp. 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Dalecki, M.G.; Coughenour, C.M. Agrarianism in American society. Rural Sociol. 1992, 57, 48–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Moriano, J.A.; Jaén, I. Individualism and entrepreneurship: Does the pattern depend on the social context? Int. Small Bus. J. 2016, 34, 760–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colebrook, C. Feminism and autonomy: The crisis of the self-authoring subject. Body Soc. 1997, 3, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupton, D. Quantifying the body: Monitoring and measuring health in the age of mHealth technologies. Crit. Public Health 2013, 23, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mau, S. The Metric Society: On the Quantification of the Social; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, P. Political Ecology: A Critical Introduction; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Schramski, S.; Neto, C. “Carbon Cowboys” Chasing Emissions Offsets in the Amazon Keep Forest-Dwelling Communities in the Dark. Inside Climate News. 28 November 2023. Available online: https://insideclimatenews.org/news/28112023/carbon-cowboys-keep-amazon-communities-dark/ (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Scrinis, G. Nutritionism: The Science and Politics of Dietary Advice; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, M. Sustainability as ideological praxis: The acting out of planning’s master-signifier. City 2010, 14, 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölscher, K.; Wittmayer, J.M.; Loorbach, D. Transition versus transformation: What’s the difference? Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2018, 27, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loorbach, D.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Avelino, F. Sustainability transitions research: Transforming science and practice for societal change. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2017, 42, 599–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, N. Climates of capital: For a trans-environmental eco-socialism. New Left Rev. 2021, 127, 94–127. [Google Scholar]

- Borras, S.M., Jr. Contemporary agrarian, rural and rural–urban movements and alliances. J. Agrar. Change 2023, 23, 453–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolan, M. COVID-19’s impact on Gendered Household Food Practices: Eating and feeding as expressions of competencies, moralities, and mobilities. Sociol. Q. 2022, 63, 449–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirier, N. Alternative animal products: Protection rhetoric or protection racket? J. Crit. Anim. Stud. 2021, 18, 27–54. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, R.C.; Sanbonmatsu, J. Veganism and Capitalism. In The Plant-Based and Vegan Handbook: Psychological and Multidisciplinary Perspectives; Athanassakis, Y., Larue, R., O’Donohue, W., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 109–128. [Google Scholar]

- Leitinger, L. Farmed nonhuman animals in newspapers and Aphro-ism. Anim. Ethics Rev. 2021, 1, 64–73. [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro-Rodrigues, L. Connecting racial and species justice: Towards an Afrocentric animal advocacy. Philos. Soc. Crit. 2022, 48, 1075–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGreevy, S.R.; Rupprecht, C.D.; Niles, D.; Wiek, A.; Carolan, M.; Kallis, G.; Kantamaturapoj, K.; Mangnus, A.; Jehlička, P.; Taherzadeh, O.; et al. Sustainable agrifood systems for a post-growth world. Nat. Sustain. 2022, 5, 1011–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, D.; Heffron, R. Just transition: Integrating climate, energy and environmental justice. Energy Policy 2018, 119, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubert, P.M.; Gardin, B.; Huber, É.; Schiavo, M.; Alliot, C. Designing just transition pathways: A methodological framework to estimate the impact of future scenarios on employment in the French dairy sector. Agriculture 2021, 11, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouhana, F.; Zhu, J.; Chacon-Hurtado, D.; Hertel, S.; Bagtzoglou, A.C. Ensuring a Just Transition: The Electric Vehicle Revolution from a Human Rights Perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 462, 142667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).