The Role of the Workplace Environment in Shaping Employees’ Well-Being

Abstract

1. Introduction

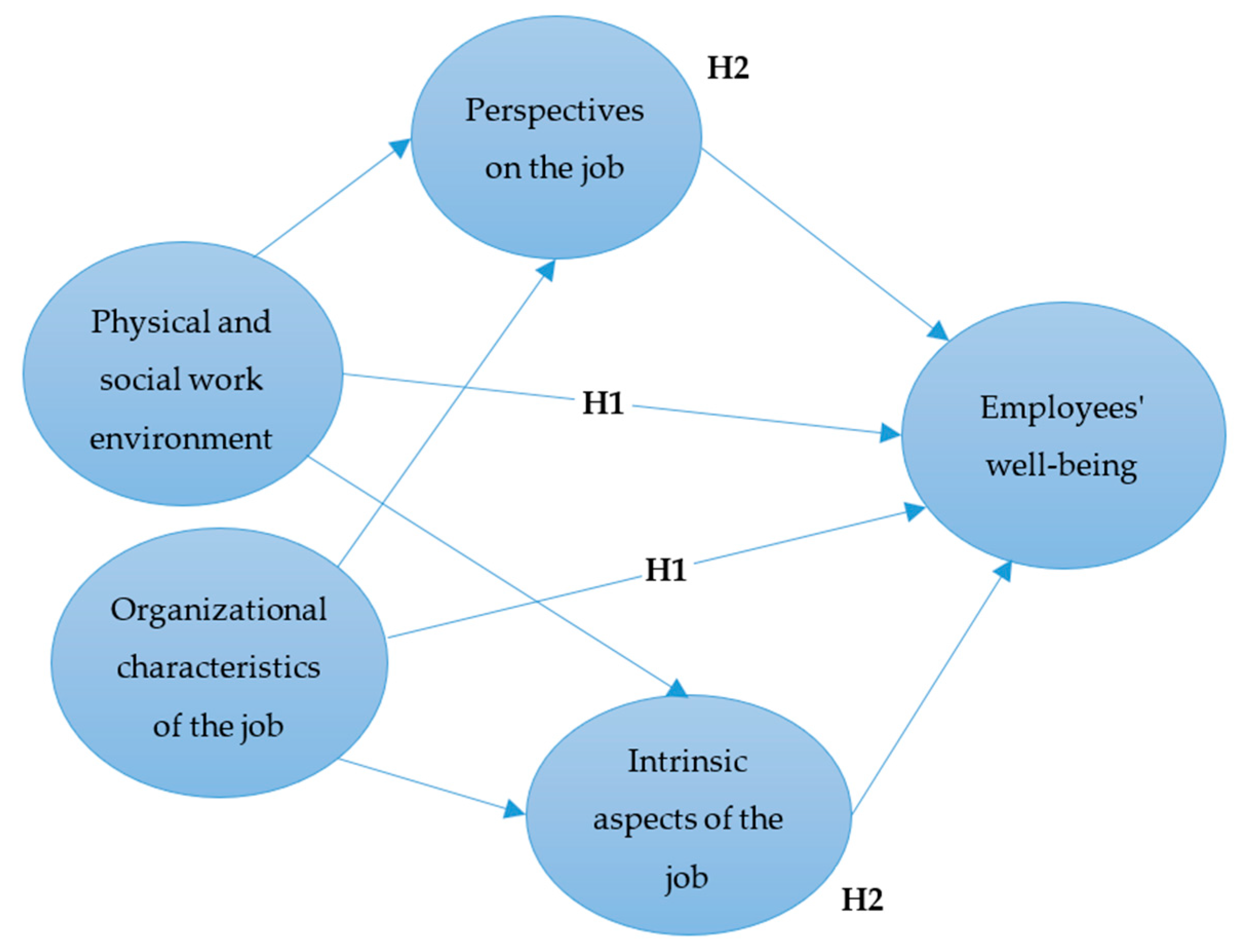

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Direct Influences of Work Environment and Organizational Characteristics on Employee Well-Being

2.2. Mediating Effects of Intrinsic Aspects and Perspectives of the Job

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Selected Variables

3.3. Research Methods

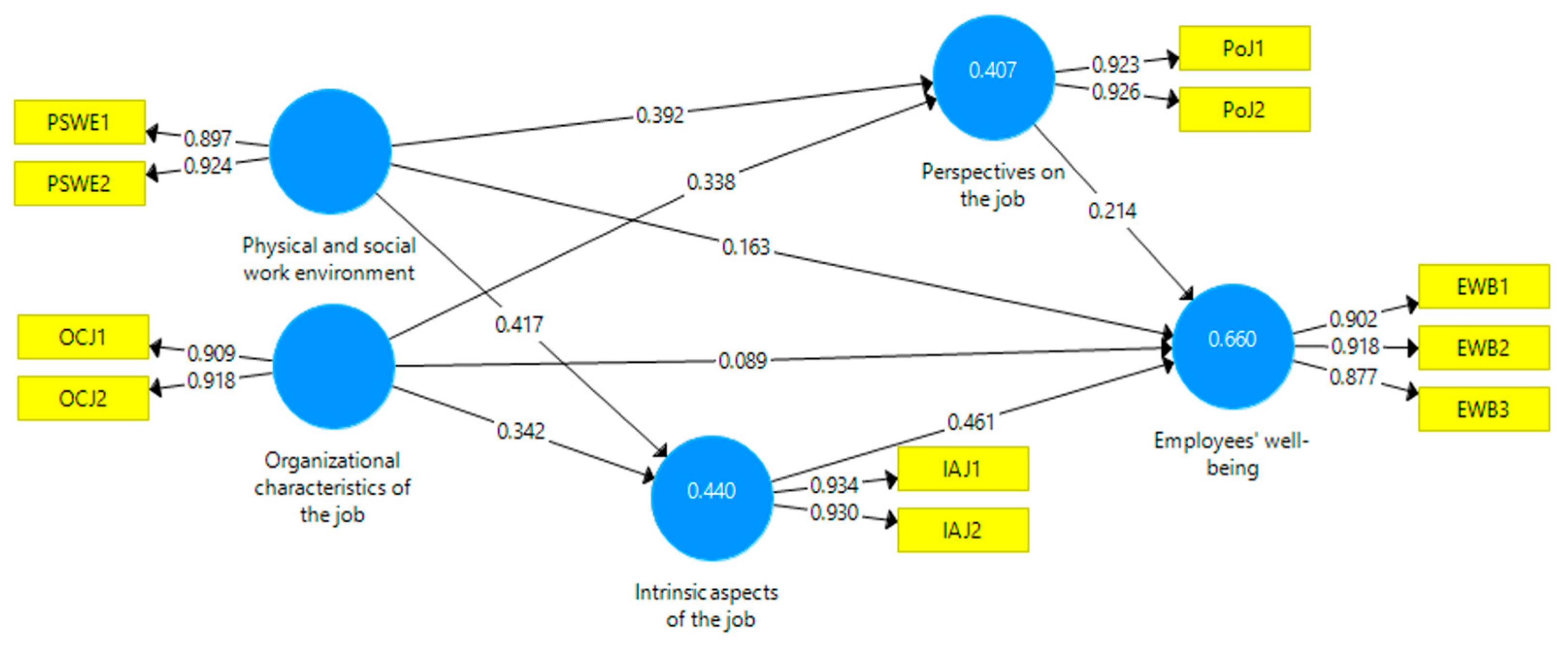

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical and Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Further Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | Items | |

|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic variables | Gender | |

| Age | ||

| Education | ||

| Work experience | ||

| Position held | ||

| Organization’s Sector | ||

| Physical and social work environment | PSWE1 | The working conditions in the organization I work for are good. |

| PSWE2 | The work relationships in the organization I work for are good. | |

| Organizational characteristics of the job | OCJ1 | Managers provide support, feedback and assistance, helping to resolve challenges. |

| OCJ2 | You can influence decisions that are important for your work. | |

| Intrinsic aspects of the job | IAJ1 | My organization motivates me to deliver the best performance at work. |

| IAJ2 | In exchange for my efforts, I receive the respect and recognition my work deserves. | |

| Perspectives of the job | PoJ1 | In exchange for the efforts I make, I have satisfactory promotion prospects. |

| PoJ2 | In my current job, I have the opportunity to develop my professional expertise. | |

| Employees’ well-being | EWB1 | Overall, I feel good physically and mentally. |

| EWB2 | I consider my work to be meaningful and purposeful. | |

| EWB3 | I am proud of the work I do. |

References

- Kossek, E.E.; Kalliath, T.; Kalliath, P. Achieving employee well-being in a changing work environment: An expert commentary on current scholarship. Int. J. Manpow. 2012, 33, 738–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhenjing, G.; Chupradit, S.; Ku, K.Y.Ș.; Nassani, A.A.; Haffar, M. Impact of Employees’ Workplace Environment on Employees’ Performance: A Multi-Mediation Model. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 890400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellini, D.; Barbieri, B.; Loi, M.; Mondo, M.; De Simone, S. The Restorative Quality of the Work Environments: The Moderation Effect of Environmental Resources between Job Demands and Mindfulness. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, J.D.; Van Hooff, M.L.M.; Guerts, S.A.E.; Kompier, M.A.J. Exercise to Reduce Work-Related Fatigue among Employees: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2017, 4, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaari, R.; Sarip, A.; Ramadhinda, S. A Study of the Influence of Physical Work Environments on Employee Performance. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2022, 12, 1734–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazlauskaite, R.; Martinaityte, L.; Lyubovnikova, J.; Augutyte-Kvedaravičienė, I. The Physical Office Work Environment and Employees’ Well-being: Current State of Research and Future Research Agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2022, 25, 413–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazanchi, S.; Sprinkle, T.A.; Masterson, S.S.; Tong, N. A Spatial Model of Work Relationships: The Relationship-Building and Relationship-Straining Effects of Workspace Design. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2018, 43, 590–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Duijnhoven, J.; Aarts, M.P.J.; Aries, M.B.C.; Rosemann, A.L.P.; Kort, H.S.M. Systematic Review on the Interaction between Office Light Conditions and Occupational Health: Elucidating Gaps and Methodological Issues. Indoor Built Environ. 2019, 28, 152–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrejiová, M.; Piñosová, M.; Králiková, R.; Dolník, B.; Liptai, P.; Dolníková, E. Analysis of the Impact of Selected Physical Environmental Factors on the Health of Employees: Creating a Classification Model Using a Decision Tree. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 5080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloch, R.M.; Maesano, C.N.; Christoffersen, J.; Mandin, C.; Csobod, E.; de Oliveira Fernandes, E.; Annesi-Maesano, I.; On Behalf of the SINPHONIE Consortium. Daylight and School Performance in European Schoolchildren. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Campanella, C.; Aristizabal, S.; Jamrozik, A.; Zhao, J.; Porter, P.; Ly, S.; Bauer, B.A. Impacts of Dynamic L.E.D. Lighting on the Well-Being and Experience of Office Occupants. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Kort, Y.; Smolders, K. Effects of dynamic lighting on office workers: First results of a field study with monthly alternating settings. Light. Res. Technol. 2010, 42, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukumura, Y.E.; Gray, J.M.; Lucas, G.M.; Becerik-Gerber, B.; Roll, S.C. Worker Perspectives on Incorporating Artificial Intelligence into Office Workspaces: Implications for the Future of Office Work. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunde, E.; Pedersen, T.; Mrdalj, J.; Thun, E.; Granli, J.; Harris, A.; Bjorvatn, B.; Waage, S.; Skene, D.J.; Pallesen, S. Alerting and Circadian Effects of Short-Wavelength vs. Long-Wavelength Narrow-Bandwidth Light during a Simulated Night Shift. Clocks Sleep 2020, 2, 502–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.-M.; Cheng, H.-L.; Huang, H.-Y.; Chen, C.-F. Exploring individuals’ subjective well-being and loyalty towards social network sites from the perspective of network externalities: The Facebook case. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2013, 33, 539–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, E.; Kim, H.; Uysal, M. Life satisfaction and support for tourism development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 50, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, O.; Payaud, M.; Merunka, D.; Valette-Florence, P. The impact of corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment: Exploring multiple mediation mechanisms. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, S.; Hossain, M.B.; Töth Naärne, E.Z.; Vasa, L. The Mediating Effect of Organizational and Coworkers Support on Employee Retention in International Non-Governmental Organizations in Gaza Strip. Decis. Mak. Appl. Manag. Eng. 2022, 5, 396–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayed, N.M.; Edeh, F.O.; Islam, K.M.A.; Nitsenko, V.; Dubovyk, T.; Doroshuk, H. An Investigation into the Effect of Knowledge Management on Employee Retention in the Telecom Sector. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criveanu, M.M. Investigating Digital Intensity and E-Commerce as Drivers for Sustainability and Economic Growth in the E.U. Countries. Electronics 2023, 12, 2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiukstis, A.; Kovaite, K.; Butvilas, T.; Sumakaris, P. Impact of Organisational Climate on Employees’ Well-being and Healthy Relationships at Work: A Case of Social Service Centres. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimbayana, T.A.K.; Erari, A.; Aisyah, S. The Influence of Competence, Cooperation and Organizational Climate on Employee Performance with Work Motivation as a Mediation Variable (Study on the Food and Agriculture Office Clump of Merauke Regency). Tech. Soc. Sci. J. 2022, 27, 556–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmani, F.; Sejdiu, S.; Jusufi, G. Organizational Climate and Job Satisfaction. Management 2022, 27, 361–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponting, S.S. Organizational Identity Change: Impacts on Hotel Leadership and Employees’ Well-being. Serv. Ind. J. 2019, 40, 6–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahtani, N.S.A.; Sulphey, M.M. A Study on How Psychological Capital, Social Capital, Workplace Well-being, and Employee Engagement Relate to Task Performance. SAGE Open 2022, 12, 21582440221095010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, E.; Bártolo, A.; Rodrigues, F.; Pereira, A.; Duarte, J.; Da Silva, C. Impact of Psychological Aggression at the Workplace on Employees’ Health: A Systematic Review of Personal Outcomes and Prevention Strategies. Psychol. Rep. 2021, 124, 929–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, S.F.; Wang, M.; Tang, M.; Saeed, A.; Iqbal, J. How Toxic Workplace Environment Affects the Employee Engagement: The Mediating Role of Organizational Support and Employees’ well-being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.L.; Rew, L. A systematic review of the literature: Workplace violence in the emergency department. J. Clin. Nurs. 2011, 20, 1072–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wech, B.A.; Howard, J.; Autrey, P. Workplace Bullying Model: A Qualitative Study on Bullying in Hospitals. Employ. Responsib. Rights J. 2020, 32, 73–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Rasool, S.F.; Ma, D. The Relationship between Workplace Violence and Innovative Work Behavior: The Mediating Roles of Employees’ Well-being. Healthcare 2020, 8, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitencourt, M.R.; Jacinto Alarcáo, A.C.; Silva, L.L.; De Carvalho Dutra, A.; Caruzzo, N.M.; Roszkowski, I.; Bitencourt, M.R.; Marques, V.D.; De Barros Carvalho, M.D. Predictors of Violence against Health Professionals during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Brazil: A Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhusal, A.; Adhikari, A.; Pradhan, P.M.S. Workplace Violence and Its Associated Factors among Health Care Workers of a Tertiary Hospital in Kathmandu, Nepal. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0288680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.-Q.; Pan, B.-C.; Sun, W.; Wu, H.; Wang, J.-N.; Wang, L. Anxiety Symptoms among Chinese Nurses and the Associated Factors: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Psychiatry 2012, 12, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernburg, M.; Vitzthum, K.; Groneberg, D.A.; Mache, S. Physicians’ Occupational Stress, Depressive Symptoms and Work Ability in Relation to Their Working Environment: A Cross-Sectional Study of Differences among Medical Residents with Various Specialties Working in German Hospitals. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Wei, Y.; Meng, X.; Li, J. The Mediation Effects of Coping Style on the Relationship between Social Support and Anxiety in Chinese Medical Staff during COVID-19. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, C.; Teodoro, M.; De Vita, A.; Giambô, F.; Mento, C.; Muscatello, M.R.A.; Alibrandi, A.; Italia, S.; Fenga, C. Factors Affecting Perceived Work Environment, Well-being, and Coping Styles: A Comparison between Physicians and Nurses during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaisier, I.; de Bruijn, J.; de Graaf, R.; ten Have, M.; Beekman, A.; Penninx, B. The contribution of working conditions and social support to the onset of depressive and anxiety disorders among male and female employees. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 64, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodin Danielsson, C.; Theorell, T. Office Employees’ Perception of Workspace Contribution: A Gender and Office Design Perspective. Environ. Behav. 2019, 51, 995–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronsson, G.; Theorell, T.; Grape, T.; Hammarstrom, A.; Hogstedt, C.; Marteinsdottir, I.; Skoog, I.; Tráskman-Bendz, L.; Hall, C. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and burnout symptoms. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, P.K.H.; Chen, X.; Lam, E.H.K.; Li, J.; Kahler, C.W.; Lau, J.T.F. The Moderating Role of Social Support on the Relationship Between Anxiety, Stigma, and Intention to Use Illicit Drugs Among HIV-Positive Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS Behav. 2020, 24, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.G. Do Organizational Socialization Tactics Influence Newcomer Embeddedness and Turnover? J. Manag. 2006, 32, 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, P.C.; Allen, D.G. Compensation, Benefits and Employee Turnover: HR Strategies for Retaining Top Talent. Compens. Benefits Rev. 2013, 45, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karacsony, P.; Päsztöovä, V.; Vinichenko, M.; Huszka, P. The Impact of the Multicultural Education on Students’ Attitudes in Business Higher Education Institutions. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romao, S.; Ribeiro, N.; Gomes, D.R.; Singh, S. The Impact of Leaders’ Coaching Skills on Employees’ Happiness and Turnover Intention. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yucel, I. Transformational Leadership and Turnover Intentions: The Mediating Role of Employee Performance during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinh, N.Q.; Hien, L.M.; Hung, D.Q. The Relationship between Transformational Leadership, Job Satisfaction and Employee Motivation in the Tourism Industry. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joel, O.O.; Moses, C.L.; Igbinoba, E.E.; Olokundun, M.A.; Salau, O.P.; Ojebola, O.; Adebayo, O.P. Bolstering the Moderating Effect of Supervisory Innovative Support on Organisational Learning and Employees’ Engagement. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmot, M.; Wilkinson, R.G. Health and the Psychosocial Environment at Work. In Social Determinants of Health, 2nd ed.; Marmot, M., Wilkinson, R.G., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourbonnais, R.; Brisson, C.; Moisan, J.; Vézina, M. Job strain and psychological distress in white-collar workers. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 1996, 22, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodin Danielsson, C.; Theorell, T. Office Design’s Impact on Psychosocial Work Environment and Emotional Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila-Gutiérrez, M.J.; de Miranda, S.S.F.; Aguayo-González, F. Occupational Safety and Health 5.0—A Model for Multilevel Strategic Deployment Aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals of Agenda 2030. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, S.L.; Green, C.R.; Marty, A. Meaningful Work, Job Resources, and Employee Engagement. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuck, B.; Hart, J.; Walker, K.; Keith, R. Work determinants of health: New directions for research and practice in human resource development. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2023, 34, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliday, B.; van der Laan, L.; Raineri, A. Prioritizing Work Health, Safety, and Well-being in Corporate Strategies: An Indicative Framework. Safety 2024, 10, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustard, C.; Lavis, J.; Ostry, A. New Evidence and Enhanced Understandings. In Healthier Societies from Analysis to Action; Heymann, J., Hertzman, C., Barer, M., Evans, R., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 173–201. [Google Scholar]

- Milczarek, M.; Schneider, E.; Rial González, E. OSH in Figures: Stress at Work-Facts and Figures; European Agency for Safety and Health at Work: Luxemburg, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rugulies, R. What is a psychosocial work environment? Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2019, 45, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swamy, D.R.; Nanjundeswaraswamy, T.S.; Rashmi, S. Quality of work life: Scale development and validation. Int. J. Caring Sci. 2015, 8, 281. [Google Scholar]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; LoBuglio, N.; Dutton, J.E.; Berg, J.M. Job crafting and cultivating positive meaning and identity in work. In Advances in Positive Organizational Psychology; Emerald Group Publishing Ltd.: Leeds, UK, 2013; pp. 281–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa Pacheco, P.; Coello-Montecel, D.; Tello, M. Psychological Empowerment and Job Performance: Examining Serial Mediation Effects of Self-Efficacy and Affective Commitment. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job Demands-Resources Theory: Taking Stock and Looking Forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wingerden, J.; Derks, D.; Bakker, A.B. The Impact of Personal Resources and Job Crafting Interventions on Work Engagement and Performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 56, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicke, T.; Stebner, F.; Linninger, C.; Kunter, M.; Leutner, D. A Longitudinal Study of Teachers’ Occupational Well-Being: Applying the Job Demands-Resources Model. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 262–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B. Job Crafting: Towards a New Model of Individual Job Redesign: Original Research. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2010, 36, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelencser, M.; Szabö-Szentgröti, G.; Komüves, Z.S.; Hollösy-Vadasz, G. The Holistic Model of Labour Retention: The Impact of Workplace Wellbeing Factors on Employee Retention. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, N.A.; Alarcon, G.M.; Bragg, C.B.; Hartman, M.J. A Meta-Analytic Examination of the Potential Correlates and Consequences of Workload. Work Stress 2015, 29, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koczy, L.T.; Susniene, D.; Purvinis, O.; Szombathelyi, M.K. A New Similarity Measure of Fuzzy Signatures with a Case Study Based on the Statistical Evaluation of Questionnaires Comparing the Influential Factors of Hungarian and Lithuanian Employee Engagement. Mathematics 2022, 10, 2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, D.; Pereira, A. Emotion Regulation and Job Satisfaction Levels of Employees Working in Family and Non-Family Firms. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kralikova, R.; Lumnitzer, E.; Dzurrovâ, L.; Yehorova, A. Analysis of the Impact of Working Environment Factors on Employee’s Health and Well-being; Workplace Lighting Design Evaluation and Improvement. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Suh, E.M.; Lucas, R.E.; Smith, H.L. Subjective Well-Being: Three Decades of Progress. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 276–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D.; Keyes, C.L.M. The Structure of Psychological Well-Being Revisited. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalliath, T.; Brough, P. Work-Life Balance: A Review of the Meaning of the Balance Construct. J. Manag. Organ. 2008, 14, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldham, G.R.; Fried, Y. Employee Reactions to Workplace Characteristics. J. Appl. Psychol. 1987, 72, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, J.R.; Oldham, G.R. Development of the Job Diagnostic Survey. J. Appl. Psychol. 1975, 60, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The Job Demands-Resources Model: State of the Art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Springer Science & Business Media: Boston, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; McCauley, C.; Rozin, P.; Schwartz, B. Jobs, Careers, and Callings: People’s Relations to Their Work. J. Res. Pers. 1997, 31, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Powell, G.N. When Work and Family Are Allies: A Theory of Work-Family Enrichment. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 72–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vianen, A.E.M. A Person-Environment Fit: A Review of Its Basic Tenets. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 75–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS 4. Monheim am Rhein, Germany: SmartPLS. Available online: https://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- Dash, G.; Paul, J. CB-SEM vs. PLS-SEM methods for research in social sciences and technology forecasting. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 173, 121092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garson, D. Partial Least Squares (PLS-SEM). Available online: https://www.smartpls.com/resources/ebook_on_pls-sem.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2024).

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Cheah, J.-H.; Ting, H.; Moisescu, O.I.; Radomir, L. Structural Model Robustness Checks in PLS-SEM. Tour. Econ. 2020, 26, 531–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaithilingam, S.; Ong, C.S.; Moisescu, O.I.; Nair, M.S. Robustness Checks in PLS-SEM: A Review of Recent Practices and Recommendations for Future Applications in Business Research. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 173, 114465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Ray, S. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sulistiawan, J.; Moslehpour, M.; Diana, F.; Lin, P.-K. Why and When Do Employees Hide Their Knowledge? Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, E.M.; Schmied, E.A.; Easterling, A.P.; Yablonsky, A.M.; Glickman, G.L. A Hybrid Effectiveness-Implementation Study of a Multi-Component Lighting Intervention for Hospital Shift Workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juslén, H.; Tenner, A. Mechanisms involved in enhancing human performance by changing the lighting in the industrial workplace. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2005, 35, 843–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istrate-Ofiţeru, A.-M.; Mogoantă, C.A.; Zorilă, G.-L.; Roşu, G.-C.; Drăguşin, R.C.; Berbecaru, E.-I.-A.; Zorilă, M.V.; Comănescu, C.M.; Mogoantă, S.-Ș.; Vaduva, C.-C.; et al. Clinical Characteristics and Local Histopathological Modulators of Endometriosis and Its Progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melinte-Popescu, A.-S.; Popa, R.-F.; Harabor, V.; Nechita, A.; Harabor, A.; Adam, A.-M.; Vasilache, I.-A.; Melinte-Popescu, M.; Vaduva, C.; Socolov, D. Managing Fetal Ovarian Cysts: Clinical Experience with a Rare Disorder. Medicina 2023, 59, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, D.R.; Ribeiro, N.; Santos, M.J. “Searching for Gold” with Sustainable Human Resources Management and Internal Communication: Evaluating the Mediating Role of Employer Attractiveness for Explaining Turnover Intention and Performance. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D. A Literature Review on Employee Retention with Focus on Recent Trends. Int. J. Sci. Res. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2019, 6, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stazyk, E.C.; Davis, R.S.; Liang, J. Probing the Links between Workforce Diversity, Goal Clarity, and Employee Job Satisfaction in Public Sector Organizations. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgeson, F.P.; Humphrey, S.E. The Work Design Questionnaire (WDQ): Developing and validating a comprehensive measure for assessing job design and the nature of work. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 1321–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binsaeed, R.H.; Yousaf, Z.; Grigorescu, A.; Condrea, E.; Nassani, A.A. Emotional Intelligence, Innovative Work Behavior, and Cultural Intelligence Reflection on Innovation Performance in the Healthcare Industry. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, U.; Fülöp, M.T.; Tiron-Tudor, A.; Topor, D.I.; Căpușneanu, S. Impact of Digitalization on Customers’ Well-Being in the Pandemic Period: Challenges and Opportunities for the Retail Industry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoko, O.; Ashkanasy, N. (Eds.) Organizational Behaviour & the Physical Environment, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Spector, P.E. Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Research and Practice, 8th ed.; John Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; 416p. [Google Scholar]

- Nyberg, A.; Bernin, P.; Theorell, T. The Impact of Leadership on the Health of Subordinates; National Institute of Working Life: Stockholm, Sweden, 2005; Available online: https://www.su.se/polopoly_fs/1.51750.1321891474!/P2456_AN.pdf (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- Baumann, A.; Muijen, M. (Eds.) Mental Health and Well-Being at the Workplace-Protection and Inclusion; WHO Regional Office for Europe and Wolfgang Gaebel, German Alliance for Mental Health: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2010; 60p. [Google Scholar]

- Nyberg, A.; Westerlund, H.; Magnusson Hanson, L.; Theorell, T. Managerial leadership is associated with self-reported sickness absence and sickness presenteeism among Swedish men and women. Scand. J. Public Health 2008, 36, 803–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab, A.; Diab, H.M.; Emam, D.H. How Does Organizational Climate Contribute to Job Satisfaction and Commitment of Agricultural Extension Personnel in New Valley Governorate, Egypt? Alex. Sci. Exch. J. 2021, 42, 749–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozsoy, T. The Effect of Innovative Organizational Climate on Employee Job Satisfaction. Mark. Manag. Innov. 2022, 2, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, H.O.; AL-Abrrow, H. Predicting Positive and Negative Behaviours at Work: Insights from Multi-Faceted Perceptions and Attitudes. Glob. Bus. Organ. Excell. 2022, 42, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rurkkhum, S. A bundle of human resource practices and employee resilience: The role of employees’ well-being. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2023, 16, 716–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Begum, M.; Van Eerd, D.; Smith, P.M.; Gignac, M.A.M. Organizational perspectives on how to successfully integrate health promotion activities into occupational health and safety. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 63, 270–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gender | Frequency | Position held | Frequency |

| male | 56.7% | managerial position | 13.6% |

| female | 43.3% | subordinate position | 86.4 |

| Age | Frequency | Work experience | Frequency |

| 18–30 years old | 14.1% | 0–10 years | 21.1% |

| 31–40 years old | 28.7% | 11–20 years | 33.2% |

| 41–50 years old | 30.8% | 21–30 years | 32.1% |

| 51–60 years old | 21.9% | 31–40 years | 11.5% |

| over 60 years old | 4.4% | over 40 years | 2.1% |

| Education | Frequency | Organization’s sector | |

| high school | 32.4% | agriculture | 12.5% |

| bachelor’s degree | 40.2% | industry | 18.0% |

| master’s degree | 22.5% | services | 56.4% |

| doctoral degree | 5.0% | technology and communications | 13.1% |

| Variables | References |

|---|---|

| Employees’ well-being | [70,71] |

| Physical and social work environment | [72,73] |

| Organizational characteristics of the job | [74,75] |

| Intrinsic aspects of the job | [76,77] |

| Perspectives of the job | [78,79] |

| Variable | Initial Communality | Extracted Communality |

|---|---|---|

| PSWE1 | 0.263 | 0.414 |

| PSWE2 | 0.382 | 0.590 |

| OCJ1 | 0.733 | 0.853 |

| OCJ2 | 0.735 | 0.838 |

| PoJ1 | 0.638 | 0.770 |

| PoJ2 | 0.637 | 0.671 |

| IAJ1 | 0.722 | 0.781 |

| IAJ2 | 0.656 | 0.797 |

| EWB1 | 0.671 | 0.727 |

| EWB2 | 0.703 | 0.845 |

| EWB3 | 0.618 | 0.667 |

| Alpha Cronbach | AVE | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original Sample | Standard Deviation | T Statistics | p Values | Original Sample | Standard Deviation | T Statistics | p Values | |

| Employees’ well-being | 0.881 | 0.017 | 51.079 | 0.000 | 0.809 | 0.022 | 36.309 | 0.000 |

| Intrinsic aspects of the job | 0.849 | 0.023 | 37.050 | 0.000 | 0.869 | 0.017 | 50.508 | 0.000 |

| Organizational characteristics of the job | 0.802 | 0.027 | 29.185 | 0.000 | 0.834 | 0.019 | 43.784 | 0.000 |

| Perspectives on the job | 0.83 | 0.026 | 32.383 | 0.000 | 0.854 | 0.019 | 46.137 | 0.000 |

| Physical and social work environment | 0.796 | 0.027 | 29.312 | 0.000 | 0.830 | 0.019 | 44.280 | 0.000 |

| Employees’ Well-Being | Intrinsic Aspects of the Job | Organizational Characteristics of the Job | Perspectives on the Job | Physical and Social Work Environment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employees’ well-being | 0.899 | ||||

| Intrinsic aspects of the job | 0.776 | 0.932 | |||

| Organizational characteristics of the job | 0.550 | 0.561 | 0.913 | ||

| Perspectives on the job | 0.718 | 0.786 | 0.544 | 0.924 | |

| Physical and social work environment | 0.607 | 0.596 | 0.525 | 0.570 | 0.911 |

| Employees’ Well-Being | Intrinsic Aspects of the Job | Organizational Characteristics of the Job | Perspectives on the Job | Physical and Social Work Environment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employees’ well-being | |||||

| Intrinsic aspects of the job | 0.847 | ||||

| Organizational characteristics of the job | 0.655 | 0.679 | |||

| Perspectives on the job | 0.839 | 0.835 | 0.667 | ||

| Physical and social work environment | 0.723 | 0.721 | 0.655 | 0.697 |

| VIF | |

|---|---|

| EWB1 | 2.575 |

| EWB2 | 2.930 |

| EWB3 | 2.176 |

| IAJ1 | 2.199 |

| IAJ2 | 2.199 |

| OCJ1 | 1.809 |

| OCJ2 | 1.809 |

| PSWE1 | 1.775 |

| PSWE2 | 1.775 |

| PoJ1 | 2.009 |

| PoJ2 | 2.009 |

| Original Sample | Standard Deviation | T Statistics | p Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employees’ well-being → EWB1 | 0.381 | 0.013 | 28.694 | 0.000 |

| Employees’ well-being → EWB2 | 0.370 | 0.012 | 32.021 | 0.000 |

| Employees’ well-being → EWB3 | 0.361 | 0.010 | 34.904 | 0.000 |

| Intrinsic aspects of the job → IAJ1 | 0.545 | 0.012 | 43.699 | 0.000 |

| Intrinsic aspects of the job → IAJ2 | 0.528 | 0.010 | 52.977 | 0.000 |

| Organizational characteristics of the job → OCJ1 | 0.535 | 0.021 | 25.417 | 0.000 |

| Organizational characteristics of the job → OCJ2 | 0.560 | 0.023 | 24.042 | 0.000 |

| Physical and social work environment → PSWE1 | 0.509 | 0.018 | 27.565 | 0.000 |

| Physical and social work environment → PSWE2 | 0.588 | 0.020 | 29.260 | 0.000 |

| Perspectives on the job → PoJ1 | 0.537 | 0.012 | 42.958 | 0.000 |

| Perspectives on the job → PoJ2 | 0.545 | 0.013 | 43.384 | 0.000 |

| Original Sample | Standard Deviation | T Statistics | p Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic aspects of the job → Employees’ well-being | 0.461 | 0.065 | 7.135 | 0.000 |

| Organizational characteristics of the job → Employees’ well-being | 0.089 | 0.042 | 2.152 | 0.032 |

| Organizational characteristics of the job → Intrinsic aspects of the job | 0.342 | 0.058 | 5.878 | 0.000 |

| Organizational characteristics of the job → Perspectives on the job | 0.338 | 0.051 | 6.580 | 0.000 |

| Perspectives on the job → Employees’ well-being | 0.214 | 0.057 | 3.775 | 0.000 |

| Physical and social work environment → Employees’ well-being | 0.163 | 0.055 | 2.962 | 0.003 |

| Physical and social work environment → Intrinsic aspects of the job | 0.417 | 0.063 | 6.612 | 0.000 |

| Physical and social work environment → Perspectives on the job | 0.392 | 0.062 | 6.378 | 0.000 |

| Original Sample | Standard Deviation | T Statistics | p Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational characteristics of the job → Perspectives on the job → Employees’ well-being | 0.072 | 0.023 | 3.155 | 0.002 |

| Organizational characteristics of the job → Intrinsic aspects of the job → Employees’ well-being | 0.158 | 0.035 | 4.500 | 0.000 |

| Physical and social work environment → Perspectives on the job → Employees’ well-being | 0.084 | 0.026 | 3.272 | 0.001 |

| Physical and social work environment → Intrinsic aspects of the job → Employees’ well-being | 0.192 | 0.038 | 4.994 | 0.000 |

| Original Sample | Standard Deviation | T Statistics | p Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational characteristics of the job → Employees’ well-being | 0.319 | 0.051 | 6.235 | 0.000 |

| Organizational characteristics of the job → Intrinsic aspects of the job | 0.342 | 0.058 | 5.878 | 0.000 |

| Organizational characteristics of the job → Perspectives on the job | 0.338 | 0.051 | 6.580 | 0.000 |

| Physical and social work environment → Employees’ well-being | 0.439 | 0.064 | 6.865 | 0.000 |

| Physical and social work environment → Intrinsic aspects of the job | 0.417 | 0.063 | 6.612 | 0.000 |

| Physical and social work environment → Perspectives on the job | 0.392 | 0.062 | 6.378 | 0.000 |

| Perspectives on the job → Employees’ well-being | 0.214 | 0.057 | 3.775 | 0.000 |

| Intrinsic aspects of the job → Employees’ well-being | 0.461 | 0.065 | 7.135 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dumitriu, S.; Bocean, C.G.; Vărzaru, A.A.; Al-Floarei, A.T.; Sperdea, N.M.; Popescu, F.L.; Băloi, I.-C. The Role of the Workplace Environment in Shaping Employees’ Well-Being. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2613. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062613

Dumitriu S, Bocean CG, Vărzaru AA, Al-Floarei AT, Sperdea NM, Popescu FL, Băloi I-C. The Role of the Workplace Environment in Shaping Employees’ Well-Being. Sustainability. 2025; 17(6):2613. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062613

Chicago/Turabian StyleDumitriu, Simona, Claudiu George Bocean, Anca Antoaneta Vărzaru, Andreea Teodora Al-Floarei, Natalița Maria Sperdea, Florentina Luminița Popescu, and Ionuț-Cosmin Băloi. 2025. "The Role of the Workplace Environment in Shaping Employees’ Well-Being" Sustainability 17, no. 6: 2613. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062613

APA StyleDumitriu, S., Bocean, C. G., Vărzaru, A. A., Al-Floarei, A. T., Sperdea, N. M., Popescu, F. L., & Băloi, I.-C. (2025). The Role of the Workplace Environment in Shaping Employees’ Well-Being. Sustainability, 17(6), 2613. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062613