Abstract

Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) have a significant role in raising competences critical for addressing global sustainability challenges. However, a lack of sustainability awareness was observed among university students. This study examines students’ awareness of sustainability and pro-environmental behaviors within a higher education institution in Jordan. It explores the role of educational institutions in fostering sustainability awareness and encouraging pro-environmental behaviors by integrating sustainable development goals into their curricula. The study employs a quantitative methodology, comprising primary data collected through a designed survey. The survey was answered by 503 students from the University of Jordan. The research adopted a combination of statistical methods for the analysis of the survey results, including t-tests, one-way ANOVA, and Tukey’s post hoc test. A regression analysis of the survey results was performed to test the proposed hypotheses. The results reveal that while students have a moderate level of awareness, they display a high level of pro-environmental behavior. Furthermore, the study reveals that the inclusion of the 17 SDGs in the curriculum positively impacts students’ awareness and influences sustainable behaviors. The results also suggest that student behavior at the University of Jordan is impacted by gender, age, and academic year, while awareness remains consistent. The study concluded that the University of Jordan is geared to enhance the students’ understanding of SDGs and their pro-environmental behavior. The study recommends targeted curriculum enhancements to increase students’ awareness and drive behavioral changes. The importance of this study lies in the exploration of education for sustainability in higher education institutions within developing countries, where research on this topic is limited.

1. Introduction

Sustainable development is an evolving concept that can potentially drive changes in society’s behavior and institutions, aiming at achieving environmental as well as social and economic balance. In compliance with the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda requirements for Sustainable Development, which emphasizes a decade of intensified efforts to address the world’s most pressing challenges, the UN Secretary-General urged comprehensive mobilization at all levels to drive the implementation of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) globally [1].

Education is essential for realizing the SDGs, as noted by UNESCO. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development explicitly references education as an SDG (SDG #4: Quality Education), which is emphasized as a key factor in which the other 16 SDGs can be achieved, from poverty reduction to gender equality, and economic growth and health to environmental sustainability [2,3,4]. Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) are seen as effective agencies to integrate environmental, political, economic, and cultural knowledge for sustainability transitions [5,6,7,8,9,10]. In 2020, over 235 million students were pursuing higher education globally. According to UNESCO, the gross enrolment rate rose from 19% to 40% between 2000 and 2020 [4]. This growth presents a central opportunity to empower future generations to become change agents for sustainability in moving this agenda forward in a global context. In a study aimed at understanding the impact of students as sustainability agents of change, it was revealed that students can bridge partnerships between communities and universities in support of local climate action initiatives [11].

Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), highlighted in Target 4.7 of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), aims to equip learners with the competences, knowledge, skills, and values to advance sustainable development. This includes fostering global citizenship, cultural appreciation, and sustainable living practices [12]. ESD highlights a shift towards transformative, action-oriented learning approaches that integrate cross-disciplinary strategies in both formal and informal education settings [13,14].

By addressing cognitive, social-emotional, and behavioral dimensions, ESD aims to build the key competencies necessary for learners to effectively engage with all 17 SDGs and embrace impactful action toward a more sustainable tomorrow. Within this scope, it is essential to recognize that many key factors contribute significantly to students’ awareness and learning of sustainability, influencing their behavior and attitude toward sustainable practices. These factors include demographic aspects (i.e., age and gender), field of study, cultural influences, and university initiatives.

Developing a thorough understanding of sustainability, along with its relevance to professional decision-making, empowers students to make responsible and informed choices. However, a lack of sustainability knowledge and awareness was observed among university students in developed countries, where students across various disciplines showed limited knowledge and a lack of awareness of the SDGs [15,16,17,18,19]. These deficiencies impact students’ engagement with sustainability issues. The aforementioned observation is more pronounced in developing countries like Jordan, where research on sustainability education remains insufficient despite the pressing need for effective sustainability initiatives. Moreover, Jordan is dedicated to the principles of Agenda 2030, stressing the significant of inclusivity of all individuals. The government has outlined a comprehensive roadmap aimed at effectively implementing the agenda and achieving all Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). One of its fundamental emphases is to enhance awareness regarding the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Higher education institutions in Jordan are partners in the realization of these goals. Therefore, assessing the role of universities in incorporating SD into curricula and its practical implementation has become essential for fostering an efficient sustainable mindset and reaching the desired conclusions of educational and global initiatives [20]. This is crucial in developing countries, where more severe sustainability challenges such as poverty and climate vulnerability are common.

The current study was motivated by the limited academic research on the impact of embedding SDGs in the curriculum of higher education institutions in developing regions, where sustainability initiatives are critically needed. The study addresses this gap by surveying the current status quo regarding education for sustainability, particularly focusing on evaluating the integration of SDGs holistically in the curriculum of higher education institutions in Jordan. It also examines whether this integration impacts students’ sustainable awareness, and the corresponding behaviors, focusing on exploring this correlation from the perception of students. Furthermore, the influence of potential demographic and academic key factors such as gender, age, academic year, and field of study on the students’ sustainable behavior and awareness was evaluated to help incorporate sustainability concepts into the curriculum for all students when designing educational and awareness programs.

The study employs a quantitative methodology, comprising a survey of 503 students from the University of Jordan. The current research adopted a combination of statistical methods for the analysis of the survey results, including t-tests, one-way ANOVA, and Tukey’s post hoc test. A regression analysis of the survey results was performed to test the proposed hypotheses.

2. Literature Review

This section focuses on establishing the theoretical framework by outlining findings from previous studies. The aim is to evaluate how integrating Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) into curricula affects students’ awareness and pro-environmental behavior. Assessing the existing literature has helped in identifying gaps, highlighting the need for the current study. The literature review is organized into three main subsections: the role of higher education institutions (HEIs) in advancing education for sustainability, student awareness of sustainability and SGDs, and the pro-environmental behaviors among higher education students.

2.1. Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) and the Advancement of the SDGs

Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) serve as crucial catalysts in nurturing knowledge, skills, and values critical for addressing global sustainability challenges [21,22,23]. The policies, practices, and initiatives implemented by these institutions to advance sustainable development exemplify their contribution as agents in fostering environmental, social, and economic sustainability. The literature highlights the significant role of HEIs in raising awareness of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), at regional, national, and global levels. Cebriá and Junyent assert that the knowledge the students acquire during their university education is fundamental to promoting transformative change and achieving sustainable development [24]. Núñez et al. argued that sustainability knowledge positively impacted the development of sustainable competencies, emphasizing the need to integrate relevant SDGs into educational settings [25].

Bhowmik et al. pinpointed key opportunities through which universities can respond to the attainment of SDGs: teaching, research, operations and governance, and community engagement [26]. Argento et al. explored the impact of integrating sustainability into higher education, focusing on trans-disciplinary collaboration, institutional support, and alignment with SDGs [27]. It was concluded that institutional support and resources are emphasized in advancing sustainability education, and holistic strategies were called for to ensure the effective integration of sustainability into teaching, research, and societal engagement.

Many studies have emphasized how integrating SDGs into the curriculum captures HEIs’ allegiance to education for sustainable development [21,25,27,28,29,30]. According to Franco et al., the mapping of Higher Education curricula is vital to measure students’ knowledge of the topic [29]. A case study conducted by Kopnina, in which lectures on sustainable development were integrated into various courses across three HEIs in the Netherlands, concluded the prospective advantages of adjusting the curriculum to align with SDGs [30]. It stressed how students were able to develop critical and innovative competencies such as knowledge, skills, and attitudes around sustainable development and the SDGs. Filho et al. advocate for integrating sustainability, particularly the SDGs, into the university curriculum as a potential advantage in enriching the students’ community to be an agent of change [21]. In his study that surveyed 140 worldwide HEIs across 17 countries covering five continents, it was concluded that only 43% had made the strategic commitment to integrate SDGs into their curriculum. This indicates a significant opportunity to investigate the impact of SDGs’ integration of aligning educational programs with international sustainability objectives. On the other hand, Lozano et al., surveying 70 institutions worldwide, found that HEIs in Europe showed stronger interest in the integration of sustainable development compared to other regions of the world [31]. This could be attributed to many factors, including regional policies, funding opportunities, or an increased level of awareness of the matter within the European academic landscape.

While the integration of SDGs into the curriculum is key to raising students’ awareness, it is essential to bring about a paradigm shift that understands the implications of the entirety of SDGs as a framework for achieving sustainability [32,33,34]. In a study conducted to evaluate the alignment of HEIs to SDG achievements, covering 2655 HEIs in 2019 and 2020, SDG9, SDG17, and SDG 13 emerged as the most prominent SDGs in teaching [3]. Meanwhile, SDG4, “quality education”, was mentioned most frequently, according to a study conducted in Cyprus at Near East University, indicating a positive upward trend in knowledge of sustainability-related topics [35].

2.2. Student Awareness and Sustainability

Sustainability awareness in Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) has become increasingly important to SDGs’ achievement. Scholars argue for a need for pro-environmental education that adopts methodological strategies focused on impacting students’ knowledge, attitudes, skills and competencies [36,37,38]. The increase in knowledge can enhance the student’s awareness of their environmental impact, which also could explain the development of pro-environmental behaviors [39,40]. Jati et al. evaluated the level of awareness and knowledge of the SDGs among university students at Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta and concluded students’ knowledge is affected by the accessibility of information [41]. A case study conducted at the Universitat Politècnica de València, aimed at exploring knowledge of SDGs among students, found that while students had a general awareness of the SDGs, most of them lacked a comprehensive understanding of all 17 SDGs [17]. Similarly, a study investigated the level of awareness of SDGs among students in Saudi universities and concluded that Saudi students’ understanding of sustainability is at an initial level, requiring further effort to achieve the desired results [42].

Al-Zohbi and Pilotti, in a study conducted at a university in Saudi Arabia, found that while students may acknowledge the significance of addressing climate issues, they generally lack the knowledge or awareness of initiatives, frameworks, and opportunities related to sustainability [43]. This could hinder their capacity to positively contribute to building a more sustainable world. Overall, the critical remedies to address 21st century sustainable challenges, as described by Khahro and Javed, involve a transformational education system that rears knowledgeable, self-directed, and globally oriented individuals who have the capability and motivation to transform the world [44].

2.3. Pro-Environmental Behaviors Among Students

Pro-environmental knowledge plays a critical role in fostering pro-environmental behaviors among students, as a lack of understanding about environmental issues often hinders the adoption of sustainable practices. Research suggests that knowledge about sustainability significantly influences behavioral intentions, emphasizing the need for integrating environmental education into curricula. Cogut et al. conducted a study at the University of Michigan from 2012 to 2015 to investigate how knowledge promotes long-term effectiveness in sustainability [40]. The findings indicated a link between sustainability knowledge and enhanced sustainable behaviors, suggesting that raising students’ awareness promotes the HEIs’ purposes of enabling students to significantly contribute to the achievement of SDGs. By embedding sustainability themes across curricula and campus activities, as suggested by Hopkinson et al., institutions can empower students to act as agents of change, aligning their behaviors with the principles of sustainable development [45]. Heeren et al., on the other hand, stated that general sustainability knowledge poorly predicts one’s behavior, with perceived behavioral control (PBC) emerging as a stronger influence, suggesting that promoting sustainable behaviors should focus on addressing behavioral barriers and practical engagement rather than solely increasing knowledge [46]. Nonetheless, a general lack of sustainability awareness was detected among university students in Saudi Arabia, specifically in their ability to recognize recyclable and renewable materials and contribute to energy-saving and recycling efforts [18]. Therefore, to embark on the transformation potential of education in HEIs for sustainability, it is essential to adopt a holistic approach that recognizes four dimensions: knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes [12].

Many previous studies stressed the significance of education that encourages transformative learning experiences, a critical student-centered approach concerned with developing critical awareness that underlies shifts in behavior to guide life choices [47,48,49,50,51]. In other words, the ability to think, reflect, and engage with change. This can be viewed as “education about sustainability”, “education for sustainability”, and “education as sustainability” [51]. For example, sustainability learning has enhanced the learning experience, where contributions exceed knowledge and contribute towards student employability, professional development, and social responsibility [52,53].

Despite the growing literature emphasizing the importance of education for sustainability, in particular SDGs’ integration in higher education, previous studies have focused on developed countries [17,25,27,30,40]. This is consistent with the findings of a review study that assessed over 500 articles related to sustainable development in higher education, which concluded that only 8% were conducted in Asia [54]. This indicates a need for conducting research studies in underrepresented countries in the literature. Therefore, this study aims to provide an empirical investigation of the status quo of HEIs in developing countries, focusing on Jordan as a case study, where very few studies have been conducted to investigate university students’ sustainability awareness, sustainability behaviors, and the impact of SDGs’ curriculum integration into these variables.

Furthermore, the literature review shows that various studies have explicitly limited their examination to the level of knowledge and awareness of SDGs among university students [17,41,42,43]. Some explored the impact of knowledge on sustainable behaviors among students [40,46], while others focused on examining and evaluating aspects related to the integration of sustainability, and, by extension, the SDGs in higher education teaching programs [27,30,55]. However, the present study aims to extend the literature that examines these three variables that are crucial to the ESD model, sustainable knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors [25], while also exploring the impact of the integration of SDGs into higher education curricula. This will ultimately advance the discourse on ESD in HEIs. The current study focuses on exploring the topic from the perspective of students, which has been identified as a limitation in the literature [15,56].

Moreover, a comprehensive approach to exploring the status of ESD in HEIs requires an understanding of students’ sustainability awareness and behaviors across various disciplines. However, some previous studies [25,27,35] have focused their investigations on specific academic programs and within a limited number of environmental courses. Therefore, sustainability education remains restrained in particular disciplines, rather than being embedded throughout the curriculum. The present study aims to provide a holistic investigation across disciplines, while also taking into consideration the implications of some demographic and academic factors such as gender, age, and year of study. The latter has been highlighted in the literature as a limitation that should be addressed [25,27,42].

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Model and Hypothesis Development

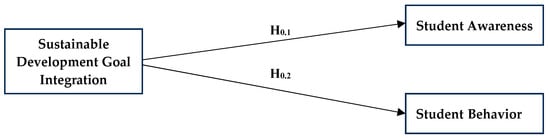

The objective of the current study is to explore the impact of integrating the sustainable development goals (SDGs) into the curriculum on Sustainability Awareness (SA) and Sustainability Behavior (SB). In order to identify the relationship between these constructs, the study has examined the existing literature, thus forming the conceptual framework for the hypothesis that integrating the SDGs into the curriculum has a detrimental influence on SA and SB.

The Environmental Education Theory (EET) emphasizes the importance of developing knowledge, attitudes, and values related to the environment [57]. Additionally, the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) suggests that an increase in environmental knowledge positively influences environmental concern [58]. Environmental concern is defined as “the degree to which people are aware of and support efforts to solve problems regarding the environment” [59]. Based on this foundation, the research proposes the following null hypothesis:

H1:

The integration of sustainable development into curricula does not significantly impact students’ awareness.

Recognizing that knowledge alone does not necessarily lead to behavioral change, we adopt the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [60]. TPB suggests that behavior is influenced by attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. This study presupposes that environmental education, and, by extension, the integration of SDGs into the curriculum, is a determinant for a behavioral change toward pro-environmental actions [61,62,63,64,65]. The research proposes the second null hypothesis:

H2:

The integration of sustainable development into curricula does not significantly impact the student’s behaviors.

By examining awareness and behavior separately, this study strengthens the theoretical foundation of sustainability education. It demonstrates that while SDG-based education can impact student awareness, an increase in awareness is not necessary to foster meaningful behavioral shifts unless curriculum content empowers students to act sustainably.

We argue that integrating SDGs into the curriculum affects (SA) and (SB) by introducing outstanding and developed curricula that will considerably enhance students’ awareness and pro-environmental behavior. Figure 1 below shows the conceptual model for this study.

Figure 1.

Research model.

3.2. Study Tool

The purpose of this study is to look at how University of Jordan student awareness as well as behavior are affected when the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are incorporated into the curriculum. The research adopted a five-point Likert scale, with responses ranging from 1 (strongly disapproving) to 5 (strongly approve), to achieve this goal for the current study. The questions from several published and peer-reviewed surveys were used to create the data-gathering tool. A survey consisting of twelve questions was used as the first variable to determine the respondent’s level of familiarity with topics related to sustainability. The student awareness measure and associated questions are shown in Table 1, which was adapted from [56]. Furthermore, the second tool was the student attitudes and behaviors scale, which was created to evaluate students’ behaviors and views following the goals of the study by utilizing the instruments used in earlier research since the scale had already taken on its final form and included nine questions derived from [42]. Table 2 describes measuring items for student behaviors. The last component was the Integration of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) into the curriculum scale, which the researchers developed and adapted from previous studies [56,66]. Several experts in the area reviewed the generated construct to ensure that it met the research goals; its final version includes 18 questions. Table 3 shows the measuring items and questions for the SDGs integration into the Curricula Scale.

Table 1.

Measurement items for the student awareness construct.

Table 2.

Measurement items for the student behaviors construct.

Table 3.

Measurement items for the Integration of SDGs into curricula.

3.3. Population and Sample

The study population is composed of all students at the University of Jordan enrolled in the ethics and human values course, who are divided into three categories: students from humanities schools, scientific schools, and medical and health science schools. To collect the study’s sample, the researcher employed a simple random sampling technique. The use of this type of sampling technique helps in the generalization of findings that are comparable (to a large extent) to those discovered when the entire population is included, while also giving equal opportunity for all population members to participate. The author used this method to collect a student response list from the university’s registration unit. The course includes 3000 students registered for the first semester of the academic year 2024/2025. As a result, the required sample to achieve the research aims was 341 students. To get the responses from the predicted population, the researcher utilized a quantitative survey constructed in Google Forms. During the first semester of the academic year 2024–2025, students who took this course provided the respondents. The sample reached 502 students. Before collecting the data, the researcher obtained ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board and the Vice Dean for Scientific Research Affairs at the University of Jordan (Approval Number: 297-2024), which shows that the researcher has given consent for this investigation. The sample was then successfully collected over the semester for one month, and the respondents to the questionnaire represented a diverse range of undergraduate and postgraduate degrees, academic years, as well as fields of study. The questionnaire was distributed to the estimated students via Moodle learning platforms by course staff members who interacted with them in the lectures. The researcher then shared the survey link in Google Forms format with other groups of lecturers, course organizers, and other colleagues, who then disseminated it to their students during their lectures. The time for collecting questionnaires began on 1 November 2024 and finished on 2 December 2024.

3.4. Data Analysis

Using SPSS software version 26, the data gathered for this investigation were tested. To assess the degree of significance, the researcher employed a range of descriptive and inferential methods. The study hypotheses and the impact of variables were tested using inferential techniques, including multiple regression and simple regression, and the collected data were evaluated using descriptive analysis (mean and standard deviation). Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for each variable to evaluate the reliability of the scale. The research used SPSS for many reasons; SPSS is an excellent choice for researchers and statistical analysts due to its ease of use and its simple graphical interface that does not require writing complex commands. It also provides a wide range of statistical analyses that cover all researchers’ needs, from simple descriptive statistics to advanced analyses such as analysis of variance and regression. In addition, SPSS is distinguished by its ability to handle data with high efficiency [67,68].

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Profile of Respondents

This study’s demographic variables were student school, age, gender, and level of education. Table 4 shows that the majority of respondents in this sample were female (66.5%), with only 33.5% being male. In terms of age, most of the respondents (84.3%) were in the 18–21 age range. The following categories were applied to the remaining sample: Ages 22 to 24: 10%; 25 to 28: 1.8%; 29 to 32: 1.8%; 33 and older: 2.2%. Regarding academic year, most of the respondents (68.9%) were in their first year of a bachelor’s degree, while the remaining respondents were distributed across the second, third, and fourth academic years, accounting for 4.6%, 11.4%, 0.9%, and 12.5% of the total, respectively, and 2.6% of the postgraduate student category. Amongst those surveyed, 60.8% were from humanities schools, 24.5% were from scientific schools, and 14.5% were from medical and health sciences schools.

Table 4.

Profile of participants (N = 502).

4.2. Validity and Reliability Results

Three types of validity were tested to ensure that the instruments have face, content, and concept validation. To maintain the research instrument’s face validity and achieve the study aims, the questionnaire was presented in both English and Arabic to several faculty members at the University of Jordan’s School of Prince Al Hussein Bin Abdullah II School of Political Science and International Studies, as well as to PhD holders and field practitioners familiar with the research topic. They reviewed and evaluated the questionnaire’s content and construction, and their feedback and views helped to enhance the instrument. To test the study instrument’s content validity, the researcher employed scales and items that had been previously developed and utilized by other scholars examining similar research topics.

Factor analysis is the most widely used method to test construct validity, since it defines the basic dimensions of the specified and specific components [69]. Thus, the purpose of the component analysis is to compress data such that correlations and patterns may be easily understood and judged [70]. To test the construct validity in this study, Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was performed, since the researchers sought to find which variables “go together” [71]. The study employed Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) due to the diverse target groups engaged. Translating the questionnaire could result in slight variations in how participants from different linguistic backgrounds interpret the questions. Thus, factor analysis was employed to reduce these variations by identifying common primary factors across various cultural contexts [72]. The researcher then conducted a pilot study, distributing the questionnaire to 25 students and assessing their answers for face validity. The pilot study’s data were sufficient to meet the study aims, and the instrument was deemed suitable for moving on with the sample survey [73].

Promax rotation was utilized to determine the number of variables needed for data analysis. Improving component correlations by raising the loadings to a power of four as part of the Promax procedure resulted in a more defined structure [74]. To perform EFA, three assumptions were made: each factor’s eigenvalues should be more than one, the sample was appropriate (Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure >0.5), and the criteria for item retained were set at a factor loading of 0.40 for each item [73,75]. The results show that the KMO test for all study variables is 0.929, which is above the proposed threshold [75,76]. Additionally, the variables showed statistically significant findings (p-value < 0.05) according to Bartlett’s test of sphericity, indicating suitable correlations for component analysis [73]. The suitability of the data for factor analysis is confirmed by two quality tests: the KMO and Bartlett’s sphericity test [77,78].

According to the findings of the EFA test for the dependent variables concerning the Student Awareness (SA) scale construct utilized in this study, all 12 items were retained without deletion because their factor loading was more than 0.40. Table 5 shows the findings for the (SA) scale and its items. In terms of the dependent variable concerning Student Behavior (SB), as indicated in Table 5, seven out of nine items have been retained, and two items (SB2 and SB7) were deleted because they had a factor loading below 0.40. The factor loading of 17 of the 18 items for the independent variable of integrating the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) into curricula was more than 0.40, while the factor loading of one item was less than 0.40. The results for variable factor loading are shown in Table 5. The rest of the dimensions and items can be classified as well-built and valid. In other words, the findings indicate that factor analysis is suitable for data evaluation in both scenarios. Additionally, all items had loadings greater than 0.4, and the eigenvalues for the resulting factors were greater than one in all constructs [79].

Table 5.

EFA results for the study variables and their construct.

A three-variable model that explains 54.443% of the total variation and falls within the 50–60% range for humanities studies was developed based on the aforementioned assumptions [75]. To understand dimensions, the pattern matrix is used to express the rotational factor loadings [80]. The calculated components match the dimensions used in this investigation, as presented in Table 5.

4.3. Research Reliability

The internal consistency test was performed to assess the dependability of the research constructs. The most widely used metric for assessing internal consistency in behavioral sciences is Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (Cronbach’s) [69]. Cronbach’s alpha computed values vary from one (showing great internal reliability) to zero (indicating no internal reliability) [81]. A previous study reveals that a minimum of 0.60 or higher is a good Cronbach’s alpha value [69,75]. The variables in this investigation are more trustworthy than is reasonable, according to the Cronbach’s alpha values determined in this work and shown in Table 6 [69]. This suggests that there is strong internal consistency in the research tool.

Table 6.

Cronbach’s alpha test for reliability.

4.4. Descriptive Statistics

The mean and standard deviation were calculated to evaluate the respondents’ directional tendencies and variances in each of the questionnaire’s items. To assess participants’ perceptions of each variable, the mean and standard deviation values were also calculated. As a gauge of central tendency, the mean provides a wide overview of the data [69]. It so gives a detailed account of how participants answered each item, dimensions, and variables. Standard deviation is a measure of variance that shows the data’s distribution [69]. A low standard deviation suggests the dataset is most likely close to the mean, and vice versa. A low standard deviation means that the mean is more stable than one with a high one [82].

A five-point Likert scale served as the basis for the criteria utilized in this study to classify each item, as shown below: (Highest and lowest points on the Likert scale)/number of levels utilized. The interpretation of the scores is as follows: 0.80 (1–1.80 means “very low”, 1.81–2.60 means “low”, 2.61–3.40 means “moderate”, 3.41–4.20 means “high”, and 4.21–5 means “very high”. As a result, the variables’ averages and standard deviations were determined and are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Mean values, standard deviations, and relative importance.

On the other hand, this study also examines the factors influencing student behavior and awareness by analyzing variations across gender, age, academic year, and area of study in the responses of the 502 students. The research adopted a combination of statistical methods, including t-tests, one-way ANOVA, and Tukey’s post hoc test. Gender differences were compared using the Independent Samples t-test, revealing substantial differences in behavior (t = −2.167, p = 0.031), with females (M = 4.210, SD = 0.573) scoring higher than males (M = 4.075, SD = 0.693), while awareness showed no considerable change (t = 0.646, p = 0.519) between males (M = 3.700, SD = 0.820) and females (M = 3.652, SD = 0.779).

One-way ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) was performed to explore age and academic year variances. Age significantly affected behavior (F = 3.577, p = 0.007), with students aged 33 and above (M = 4.649, SD = 0.483) demonstrating more positive behavior than those aged between 18 and 21 (M = 4.128, SD = 0.619, p = 0.044, per Tukey’s post hoc test), whereas awareness presented an inconsiderable difference (F = 0.133, p = 0.970).

Student behavior was significantly influenced by academic year (F = 3.256, p = 0.012), specifically amongst first- and third-year students (identified through Tukey’s test), while awareness differences were not substantial (F = 2.035, p = 0.088). On the other hand, ANOVA results for academic study-major yielded worthless differences on both behavior (F = 1.438, p = 0.238) and awareness (F = 1.496, p = 0.225).

Overall, the study used t-tests, one-way ANOVA, and Tukey’s post hoc tests to determine that behavior was significantly influenced by gender, age, and academic year, while awareness remained stable across all factors.

4.5. Hypothesis Testing

Testing hypotheses is the process of determining if a certain hypothesis is a plausible assertion [69]. To test hypotheses, one first checks the null hypothesis (H0), which is initially assumed to be true, and then examines it for the potential of rejection [69]. SPSS version 26 was used to conduct a simple regression analysis to evaluate the study hypotheses. The significance threshold must be less than 0.05 to reject the null hypothesis. Regarding the first hypothesis, as indicated in Table 8 below, the data demonstrate that R = 0.353, demonstrating a modest degree of impact between student awareness and the integration of SDGs in curricula. Plus, the integration of SDGs in the curriculum accounts for 12.5% of the variation in the dependent variable (student awareness), according to the R2 value of 0.125. Furthermore, hypothesis H0.1 is not supported due to (β value = 0.204, p < 0.05); therefore, the alternative hypothesis is supported.

Table 8.

The results of the hypothesis testing.

Concerning the second hypothesis, Table 8 shows that R = 0.453, which suggests a modest to moderate correlation between student behavior and the integration of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in the curriculum. Additionally, the integration of SDGs in the curriculum, according to the R2 value of 0.206, accounts for 20.6% of the variation in the dependent variable, which is student behavior. Rejecting the null hypothesis H0.2, which claimed that ISD does not significantly affect student behaviors, and adopting the alternative hypothesis, the results show that the independent variable positively influences the dependent variable (student behaviors) (β value = 0.218, p < 0.05). Therefore, the alternative hypothesis is supported.

Regarding the first model, as presented in Table 9, the results showed that academic level positively affects awareness (p = 0.006), which indicates that students at advanced levels have a higher perception of sustainable development issues. In contrast, gender (p = 0.964), age (p = 0.861), and specialization (p = 0.116) did not have a significant impact, showing that awareness of the SDGs is not significantly influenced by demographic characteristics. In addition, the multilinear tests confirmed that the model used is stable and free from problems with interference between variables (VIF < 10). Based on these findings, it is recommended to promote the integration of Sustainable Development Goals in school curricula, with a focus on raising awareness among students in the early school years, to ensure a deeper understanding of these important issues.

Table 9.

Hypothesis testing for the impact of SDG Integration on SA, including control variables.

For the second model, as presented in Table 10, the results also revealed that both gender and age had a moral effect, with older students showing more positive behavior towards sustainable development (B = 0.133, p < 0.001), while gender had an average effect, indicating differences in response to these issues between males and females (B = 0.182, p = 0.001). On the other hand, academic level or specialization did not have a significant impact on student behavior (p > 0.05), which indicates that student awareness and behavior toward sustainable development are not significantly influenced by their field of study or academic stage. These results emphasize the importance of promoting sustainability concepts in the curriculum for all students, considering age and gender differences in the design of educational and awareness programs, to ensure a greater impact in promoting sustainable behaviors within the university community. A summary of the research hypothesis is shown in Table 11.

Table 10.

Hypothesis testing for the impact of SDG Integration on SB, including control variables.

Table 11.

Summary of the hypothesis testing.

5. Discussion

The study investigates the significance of integrating SDGs into curricula on student sustainability awareness at the University of Jordan (UJ) and tests its impact on their attitudes and behavior. The results of a survey conducted showed the coverage of the 17 SDGs in curricula is high and positively impacts their attitudes toward sustainability and influences sustainable behaviors.

The study’s findings indicated that the majority of students at (UJ) are of the view that SDG-related knowledge is important for university students. Most of them agree with the notion (about 55.2%), and 22.9% strongly agree. The students’ recognition of the SDGs’ importance reflects their awareness of the SDGs and, therefore, indicates a level of exposure to SDG-related information. While this study did not focus on examining the sources of SDG information, it evaluated the integration of the 17 SDGs in the curricula, as the curriculum is considered the core source of SDG information among university students [15,16,25,27,28,83,84]. The study found that the coverage of the 17 SDGS in the curricula of study programs has a positive impact on student awareness of the SDGs. This aligns with previous studies that showed curriculum influences students’ sustainability awareness more than other sources, such as community and campus [85,86,87].

The study sample consists of students from three disciplines, humanities, sciences, and medical and health sciences, rather than sustainability-focused courses, indicating that student awareness encompasses not only environmental aspects but also social, economic, and political dimensions of sustainability. However, five SDGs, including quality education, poverty reduction, zero hunger, decent work and economic growth, and innovation have been covered to a great extent in the curricula across disciplines, while the remaining SDGs are less covered in their study courses. The researcher attributes this to the high response rate of 60.8% from Humanities Schools, where these topics are highly relevant.

Several case studies acknowledged the link between academic fields and the knowledge of SDGs, frequently highlighting the SDGs that are particularly relevant to their disciplines and presenting this connection as a challenge [21,27,86,88,89]. While this approach could facilitate the practical integration of SDGs in the curriculum by allowing particular disciplines to contribute considerably to particular goals, it hinders students from recognizing an overall understanding of the SDGs as a framework. Therefore, it is highly advised that the education curriculum should encompass each of the 17 SDGs, through pedagogical approaches that encourage a comprehensive understanding of sustainability, extending beyond the confines of individual disciplines. This is relevant to the present survey results that showed a moderate level of awareness among students at (UJ). A moderate level of awareness indicates that university students have a basic understanding of the importance of SDGs in HEIs and are familiar with some key national and global sustainable development policies, strategies, and initiatives. This also indicates that their level of familiarity with frameworks, institutional policies and opportunities related to sustainability, such as the UN 2030 Agenda and Jordan Vision 2025, is limited. This study concluded a need for prioritizing the process of systematizing intra- and inter-disciplinary SDG integration to broaden and deepen the students’ awareness of sustainability and their understanding of global issues [27,89,90,91]. An exemplary model for such an inter- and transdisciplinary framework can be found in the case of Swedish higher education institutions [27].

While increasing SDG knowledge through curricula at HEIs is central to student awareness of sustainability, it does not necessarily translate into sustainability behavior [92,93]. For example, Shittu argues that pro-environmental knowledge for sustainable development may not translate into pro-environmental behavior due to issues related to the expectations of a sustainable lifestyle and higher associated costs [93]. However, some studies suggest the integration of sustainability subjects in a variety of courses is a significant indicator of how the university impacts student behavior [94]. By indicating when students have good sustainability knowledge, their pro-environmental behaviors are affected positively.

Therefore, this study examines the impact of integrating SDGs in the curriculum on prompting successful behavioral change toward sustainability. The current study revealed that the coverage of SDGs in the curriculum had an impact on developing pro-environmental and socially responsible behaviors among students on campus. This is relevant to the present survey results that showed a high level of pro-environmental behaviors among students at (UJ). This indicates that there is an increasing awareness of the importance of various pro-environmental activities, such as printing only when needed, proper disposal of food waste, using reusable cups, turning off lights, and participating in sustainable environmental activities such as hygiene campaigns and tree planting. This result shows a tendency toward change in behavioral sustainability. The study also illustrates that students’ recognition of the importance of these sustainable practices has significantly increased their sense of accountability and ownership toward engaging in environmentally responsible behaviors, ranging from energy-saving measures to proper waste disposal and the use of reusable items. This suggests the positive impact of SDG integration into the curriculum on the tangible, eco-friendly behaviors of students in their daily lives. This outcome is in agreement with the findings of earlier studies, which revealed that students are more likely to adopt sustainable practices when they understand the effect of their actions on their immediate environment.

The study results found that SDG-based curricula have a stronger effect on behavioral change compared to awareness. This indicates that while SDG-based curricula provide students with environmental knowledge and attitude, they also encourage them to adopt eco-friendly behaviors. The author attributes the high pro-environmental behaviors compared to moderate level of awareness to external influences, particularly, institutional factors, in this context, university-driven sustainability initiatives and resources. For example, the University of Jordan shifted from paper-based documents to electronic formats. Also, the university started integrating solar energy into its campus, and many solid waste recycling initiatives were also introduced [95]. This is consistent with a study conducted at the University of Leeds, which revealed that the availability of bins across campus and their regular emptying were some of the crucial factors that influenced students’ environmental recycling behavior with regard to waste [96]. The high levels of pro-environmental behaviors compared to moderate levels of awareness could also be interpreted in the light of pro-environmental social influences, whereby individuals’ beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors concerning the environment are shaped by societal interaction and perceived norms [97,98], in the sense that students might feel compelled to engage in green behavior, regardless if their awareness is low, due to the increased sense of responsibility that arises from being part of an environmentally conscious community.

As for the moderate impact on awareness, this suggests that while SDG-based curricula successfully raise students’ knowledge and understanding, there are still some gaps in the depth of information or engagement required to fully understand sustainability challenges. A valid explanation for the moderate impact on awareness could also be that while SDG knowledge contributes to environmental awareness, an internal factor such as emotional engagement is the primary driver of environmental awareness and attitude [98]. In other words, while SDG-based curricula are important to the understanding of environmental issues, the emotional response, feeling concerned about the environmental issue and emotionally engaged in making change, is vital [99,100].

To further enhance students’ awareness and pro-environmental behavior, curriculum design should focus on the socio-ethical capacities of students, rather than a broad abstract knowledge. This means students should know how to apply the acquired knowledge to make a positive social impact to existing global sustainability challenges [101]. As sustainability is inter- and trans-disciplinary, the curriculum content should reflect the complexities of the topic by providing a balanced picture of its environmental, economic, and social aspects. Curriculum design should be coupled with an innovative pedagogical approach focused on enhancing students’ critical engagement with cross-disciplinary discussions using problem-solving skills, sustainability debates, and self-reflection [102].

Therefore, HEIs should invest in promoting SDG-related learning that goes beyond the traditional teaching method of SD, such as training opportunities, internships, or students’ collaborative projects focused on sustainability [17]. Some studies suggest implementing a participatory approach involving various stakeholders from society, to examine the educational systems and to contextualize the basic requirements for an SDG participatory- and action-oriented education system [103,104]. According to Cicmil et al., integrating education for sustainable development across a higher education institution is a multifaceted process that considers the curriculum content, as well as the structures, power, identity, and values [105]. Consequently, it demands a framework that combines formal measures and reporting, informal academic collaboration, and practical skills to maintain innovative pedagogical models [105], while, at the same time, negotiating the value of those propositions in relation to the institutional priorities.

It is important to recognize that higher education institutions (HEIs) may encounter challenges in implementing these advancements integrating education for sustainable development. These challenges include institutional resistance to change, financial constraints, and a lack of expert faculty members. Nonetheless, these barriers can be addressed through SD initiatives aimed at providing faculty members with development programs, collaborating with stakeholders and the community to secure funds dedicated to ESD, and aligning institutional goals with sustainability-focused accreditation requirements [106,107].

Furthermore, as reported in the results, the notable gender differences in behavior, where females demonstrate more positive behavior than males, can be attributed to the structured academic environment and societal expectations that encourage discipline and engagement among female students.

Meanwhile, the lack of significant gender differences in awareness suggests that both male and female students receive similar levels of information and exposure within the university’s curriculum. This result is consistent with other studies [108,109,110]. Scholars have argued that gender differences in awareness and knowledge of sustainability are complex and can be explained by either political ideology or environmental concern [111]. In a study conducted to compare the gender differences in activism and environmentally friendly behavior, it was revealed that women were more likely to express concerns about the environment, while they were less likely to engage in pro-environmental behaviors [112].

The impact of age on behavior aligns with the expectation that older students exhibit more responsible academic behavior compared to younger ones. This difference can be explained by the varying levels of formal and informal education that students receive in their first year compared to those in their fourth year [113]. However, awareness remains consistent across age groups, likely due to standardized curricula and shared educational resources. Nevertheless, age is considered a weak predictor of sustainability knowledge [114], as some studies have pointed out that younger individuals tend to express more concern for environmental issue and are more likely to engage in environmental behavior [114,115].

Differences in behavior were observed based on the academic year, particularly between first- and third-year students, and reflect increased academic experience and institutional adaptation. These differences may be explained by students’ varying levels, ages, or prior knowledge [83], whereas awareness remains steady across different levels of study. Lastly, the absence of significant differences in behavior and awareness based on discipline suggests that academic discipline does not play a major role in shaping these attributes, as students across faculties adhere to similar behavioral norms and have equal access to awareness-related materials.

Overall, these findings indicate that student behavior at the University of Jordan is shaped by gender, age, and academic experience, while awareness remains stable due to the university’s structured learning environment and consistent educational exposure. These discoveries underline the need to integrate sustainability concepts into university curricula for all students, considering demographic differences in developing awareness programs to maximize their success in adopting sustainable actions.

The researcher concluded that the University of Jordan is geared to enhance the students’ understanding of sustainable development goals and their pro-environmental behavior, which has been reflected in the study results. The University of Jordan has a clear policy dedicated toward integrating sustainability across its educational activities. In its Sustainability Policy for 2022–2027, the University of Jordan aims to align all its processes and practices with sustainable development goals. This policy provides the objectives and framework necessary to achieve the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs).

6. Conclusions, Limitations, and Lines of Research

6.1. Conclusions

The present study explored the integration of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) into academic curricula and examined their impact on students’ environmental awareness, attitudes, and behaviors. By focusing specifically on the University of Jordan, this research provides essential insights into the incorporation of SDGs in higher education and reveals a significant impact on sustainability awareness and behaviors among students. This research is contributing to the expanding research on education for sustainable development, particularly at higher education institutions (HEIs). A systematic survey approach was adopted, and SPSS software was used to conduct a detailed analysis of the survey results. The survey captured various population aspects, including gender, age, educational level, and student school, in which females comprised the majority of respondents (66.5%), while males made up 33.5%. The results also suggest that student behavior at the University of Jordan is impacted by gender, age, and academic year and discipline, while awareness remains consistent, highlighting the necessity to incorporate sustainability fundamentals into curricula and modify awareness programs based on demographic variances to enhance sustainable actions.

The findings show a positive association between the level of SDG coverage in academic programs and students’ attitudes toward sustainability, as well as their awareness of related global issues. While specific SDGs, such as poverty reduction and quality education, were notably emphasized across various disciplines, there is a need for a more comprehensive framework to integrate all 17 SDGs into the curricula. This can influence a better understanding of the totality of SDGs as a framework for sustainability, and thus students can comprehend the interconnectedness of sustainability issues. To enhance the impact of education on sustainability behaviors, it is essential for higher education institutions to prioritize a systematic integration of SDGs, addressing both disciplinary-specific and holistic sustainability education. This approach could empower students not only with knowledge but also with the capability to engage in sustainable practices.

6.2. Limitations and Future Lines of Research

This study has its limitations. First, there is a gender disparity in participation, as most respondents are female students. While the sample exhibits a gender bias, with 33.5% male and 66.5% female, the gender ratio difference in the survey respondents correlates to the ratio of the student population at the University of Jordan, which is 69% female to 31% male. The range of differences in response rates among genders is consistent with many previous studies that suggest females are more concerned about sustainability [116,117,118]. Second, the study did not examine the long-term effects of sustainability education, particularly how the curriculum influences students’ diverse practices and lifestyle choices. The overall goal was to provide an analysis based on the current status quo and in relation to certain pro-environmental behaviors on campus. This may overlook critical factors that influence sustainability-related behaviors. It is recommended to conduct longitudinal studies to examine the long-term effects of sustainability education and the lasting impact of curriculum interventions. Furthermore, future research could expand the investigation to explore the impact of academic disciplines as a factor shaping students’ engagement with sustainability issues.

Third, the research did not analyze the external sources of information about SDGs that students access outside the framework of the formal curriculum, which could significantly impact their awareness of sustainability-related issues. Thus, for future studies, it is recommended to include these factors, such as research activities, conferences, workshops, and initiatives, which can significantly influence student awareness and behavior in a practical sense. Finally, while the study aimed to evaluate students across different disciplines, it did not account for the varying emphasis on sustainability within each program, which could impact students’ awareness related to their specific disciplines.

Future research should continue to explore effective methods of fostering sustainable awareness and pro-environmental behavioral change and the ongoing challenges of implementing comprehensive sustainability education.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board and the Vice Dean for Scientific Research Affairs of the University of Jordan (Approval Number: 297-2024, 1 November 2024). The respondents’ consent was obtained to collect data, and anonymity was assured in the questionnaire.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- United Nations. The Sustainable-Development Goals Report; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Leicht, A. Issues and Trends in Education for Sustainable Development; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- De la Poza, E.; Merello, P.; Barberá, A.; Celani, A. Universities’ reporting on SDGs: Using the impact rankings to model and measure their contribution to sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Higher Education Global Data Report (Summary); A Contribution to the World Higher Education Conference; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- de Lange, D.E. How do universities make progress? Stakeholder-related mechanisms affecting adoption of sustainability in university curricula. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 118, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Liu, K.; Xue, B.; Fujita, T. Creating a “green university” in China: A case of Shenyang University. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 61, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, J.; Pena, M.; Tudor, T. Strategies for improving recycling at a higher education institution: A case study of the University of the West Indies, Cave Hill Campus, Barbados. Open Waste Manag. J. 2015, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Mallén, I.; Heras, M. What sustainability? higher education institutions’ pathways to reach the agenda 2030 goals. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heleta, S.; Bagus, T. Sustainable development goals and higher education: Leaving many behind. High. Educ. 2021, 81, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juma-Michilena, I.J.; Ruiz-Molina, M.E.; Gil-Saura, I.; Belda-Miquel, S. How to increase students’ motivation to engage in university initiatives towards environmental sustainability. J. Consum. Aff. 2023, 57, 1304–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budowle, R.; Krszjzaniek, E.; Taylor, C. Students as change agents for community–university sustainability transition partnerships. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieckmann, M. Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cottafava, D.; Cavaglià, G.; Corazza, L. Education of sustainable development goals through students’ active engagement: A transformative learning experience. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2019, 10, 521–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliorini, P.; Lieblein, G. Facilitating transformation and competence development in sustainable agriculture university education: An experiential and action oriented approach. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora-Polo, F.; Sánchez-Martín, J.; Corrales-Serrano, M.; Espejo-Antúnez, L. What do university students know about sustainable development goals? A realistic approach to the reception of this UN program amongst the youth population. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smaniotto, C.; Battistella, C.; Brunelli, L.; Ruscio, E.; Agodi, A.; Auxilia, F.; Baccolini, V.; Gelatti, U.; Odone, A.; Prato, R. Sustainable development goals and 2030 agenda: Awareness, knowledge and attitudes in nine Italian universities, 2019. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leiva-Brondo, M.; Lajara-Camilleri, N.; Vidal-Meló, A.; Atarés, A.; Lull, C. Spanish university students’ awareness and perception of sustainable development goals and sustainability literacy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaati, T.; El-Nakla, S.; El-Nakla, D. Level of sustainability awareness among university students in the eastern province of Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-González, E.; Jiménez-Fontana, R.; Azcárate, P. Education for sustainability and the sustainable development goals: Pre-service teachers’ perceptions and knowledge. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN). Accelerating Education for the SDGs in Universities: A Guide for Universities, Colleges, and Tertiary and Higher Education Institutions; SDSN: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Leal Filho, W.; Shiel, C.; Paço, A.; Mifsud, M.; Ávila, L.V.; Brandli, L.L.; Molthan-Hill, P.; Pace, P.; Azeiteiro, U.M.; Vargas, V.R. Sustainable Development Goals and sustainability teaching at universities: Falling behind or getting ahead of the pack? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawonde, A.; Togo, M. Implementation of SDGs at the university of South Africa. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2019, 20, 932–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedlacek, S. The role of universities in fostering sustainable development at the regional level. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 48, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebrián, G.; Junyent, M. Competencies in education for sustainable development: Exploring the student teachers’ views. Sustainability 2015, 7, 2768–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, M.E.; Siddiqui, M.K.; Abbas, A. Motivation, attitude, knowledge, and engagement towards the development of sustainability competencies among students of higher education: A predictive study. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmik, J.; Selim, S.; Huq, S. The Role of Universities in Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals, CSD-ULAB and ICCCAD Policy Brief; ULAB: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Argento, D.; Einarson, D.; Mårtensson, L.; Persson, C.; Wendin, K.; Westergren, A. Integrating sustainability in higher education: A Swedish case. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2020, 21, 1131–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefin, M.A.; Nabi, M.N.; Sadeque, S.; Gudimetla, P. Incorporating sustainability in engineering curriculum: A study of the Australian universities. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2021, 22, 576–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, I.; Saito, O.; Vaughter, P.; Whereat, J.; Kanie, N.; Takemoto, K. Higher education for sustainable development: Actioning the global goals in policy, curriculum and practice. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 1621–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopnina, H. Teaching sustainable development goals in The Netherlands: A critical approach. Environ. Educ. Res. 2018, 24, 1268–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R.; Ceulemans, K.; Alonso-Almeida, M.; Huisingh, D.; Lozano, F.J.; Waas, T.; Lambrechts, W.; Lukman, R.; Hugé, J. A review of commitment and implementation of sustainable development in higher education: Results from a worldwide survey. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 108, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mader, C.; Rammel, C. Brief for GSDR 2015 transforming higher education for sustainable development. UN Sustain. Dev. Knowl. Platf. 2015, 22, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Balsiger, J.; Förster, R.; Mader, C.; Nagel, U.; Sironi, H.; Wilhelm, S.; Zimmermann, A.B. Transformative learning and education for sustainable development. GAIA-Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2017, 26, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, E.; Ross, J.; Crawley, J.; Thompson, R. An Undergraduate Educational Model for Developing Sustainable Nursing Practice: A New Zealand Perspective; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 61, pp. 264–268. [Google Scholar]

- Akçay, K.; Altinay, F.; Altınay, Z.; Daglı, G.; Shadiev, R.; Altinay, M.; Adedoyin, O.B.; Okur, Z.G. Global Citizenship for the Students of Higher Education in the Realization of Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kickbusch, I.; Hanefeld, J. Role for academic institutions and think tanks in speeding progress on sustainable development goals. Bmj 2017, 358, j3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.; Kickbusch, I.; Taylor, P.; Abbasi, K. Accelerating Achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals; British Medical Journal Publishing Group: London, UK, 2016; Volume 352. [Google Scholar]

- Omisore, A.G.; Babarinde, G.M.; Bakare, D.P.; Asekun-Olarinmoye, E.O. Awareness and knowledge of the sustainable development goals in a University Community in Southwestern Nigeria. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 2017, 27, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Suárez, P.; Vega-Marcote, P.; Garcia Mira, R. Sustainable consumption: A teaching intervention in higher education. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2013, 15, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogut, G.; Webster, N.J.; Marans, R.W.; Callewaert, J. Links between sustainability-related awareness and behavior: The moderating role of engagement. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2019, 20, 1240–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jati, H.F.; Darsono, S.N.A.C.; Hermawan, D.T.; Yudhi, W.A.S.; Rahman, F.F. Awareness and knowledge assessment of sustainable development goals among university students. J. Ekon. Studi Pembang. 2019, 20, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abowardah, E.S.; Labib, W.; Aboelnagah, H.; Nurunnabi, M. Students’ Perception of Sustainable Development in Higher Education in Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zohbi, G.; Pilotti, M.A. Contradictions about sustainability: A case study of college students from Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khahro, S.H.; Javed, Y. Key challenges in 21st century learning: A way forward towards sustainable higher educational institutions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkinson, P.; Hughes, P.; Layer, G. Sustainable graduates: Linking formal, informal and campus curricula to embed education for sustainable development in the student learning experience. Environ. Educ. Res. 2008, 14, 435–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeren, A.J.; Singh, A.S.; Zwickle, A.; Koontz, T.M.; Slagle, K.M.; McCreery, A.C. Is sustainability knowledge half the battle? An examination of sustainability knowledge, attitudes, norms, and efficacy to understand sustainable behaviours. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2016, 17, 613–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon, R.R.; Moolenkamp, N. Sustainable IT services: Developing a strategy framework. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Manag. 2012, 9, 1250014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, S.; Russo, R.; Montoya, C. Environmental education and eco-literacy as tools of education for sustainable development. J. Sustain. Educ. 2013, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, J.D.; Burns, H.L. ‘Radically different learning’: Implementing sustainability pedagogy in a university peer mentor program. Teach. High. Educ. 2015, 20, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundiers, K.; Wiek, A. Educating students in real-world sustainability research: Vision and implementation. Innov. High. Educ. 2011, 36, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.; Barth, M.; Wiek, A.; von Wehrden, H. Drivers and Barriers of Implementing Sustainability Curricula in Higher Education--Assumptions and Evidence. High. Educ. Stud. 2021, 11, 42–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Shiel, C.; Paço, A. Implementing and operationalising integrative approaches to sustainability in higher education: The role of project-oriented learning. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 133, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrón-López, M.-J.; Velasco-Quintana, P.J.; Lavado-Anguera, S.; Espinosa-Elvira, M.d.C. Preparing sustainable engineers: A project-based learning experience in logistics with refugee camps. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunthonkanokpong, W.; Murphy, E. Sustainability awareness, attitudes and actions: A survey of pre-service teachers. Issues Educ. Res. 2019, 29, 562–582. [Google Scholar]

- Junyent, M.; de Ciurana, A.M.G. Education for sustainability in university studies: A model for reorienting the curriculum. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2008, 34, 763–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapungu, L.; Nhamo, G. Status quo of sustainable development goals localisation in Zimbabwean universities: Students perspectives and reflections. Sustain. Futures 2024, 7, 100147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breunig, M.; Murtell, J.; Russell, C. Students’ experiences with/in integrated environmental studies programs in Ontario. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2015, 15, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Liere, K.D.; Dunlap, R.E. Environmental concern: Does it make a difference how it’s measured? Environ. Behav. 1981, 13, 651–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Jones, R.E. Environmental concern: Conceptual and measurement issues. Handb. Environ. Sociol. 2002, 3, 482–524. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, H.K.; Ellinger, A.E.; Hadjimarcou, J.; Traichal, P.A. Consumer concern, knowledge, belief, and attitude toward renewable energy: An application of the reasoned action theory. Psychol. Mark. 2000, 17, 449–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klöckner, C.A. A comprehensive model of the psychology of environmental behaviour—A meta-analysis. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 1028–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.V.; Young, C.W.; Unsworth, K.L.; Robinson, C. Bringing habits and emotions into food waste behaviour. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 125, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhao, L.; Ma, S.; Shao, S.; Zhang, L. What influences an individual’s pro-environmental behavior? A literature review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 146, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massouati, L.; Abdelbaki, N. A review of the literature on factors that may influence entrepreneurial intention among university students. ESI Prepr. 2022, 9, 646. [Google Scholar]

- Maoela, M.A.; Chapungu, L.; Nhamo, G. Students’ awareness, knowledge and attitudes towards the sustainable development goals at the University of South Africa. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2024, 25, 455–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, G.A.; Barrett, K.C.; Leech, N.L.; Gloeckner, G.W. IBM SPSS for Introductory Statistics: Use and Interpretation; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, M.H.A.; Puteh, F. Quantitative data analysis: Choosing between SPSS, PLS, and AMOS in social science research. Int. Interdiscip. J. Sci. Res. 2017, 3, 14–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bougie, R.; Sekaran, U. Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yong, A.G.; Pearce, S. A beginner’s guide to factor analysis: Focusing on exploratory factor analysis. Tutor. Quant. Methods Psychol. 2013, 9, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masa’deh, R.E.; Muheisen, I.; Obeidat, B.; Bany Mohammad, A. The Impact of Supply Chain Integration on Operational Performance: An Empirical Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Almomani, L.M.; Sweis, R.; Obeidat, B.Y. The impact of talent management practices on employees’ job satisfaction. Int. J. Bus. Environ. 2022, 13, 259–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharf, F.; Nestler, S. A comparison of simple structure rotation criteria in temporal exploratory factor analysis for event-related potential data. Methodology 2019, 15, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R. Multivariate Data Analysis: Pearson College Division; Person: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Almomani, L.M.; Halalsheh, N.; Al-Dreabi, H.; Al-Hyari, L.; Al-Quraan, R. Self-directed learning skills and motivation during distance learning in the COVID-19 pandemic (case study: The university of Jordan). Heliyon 2023, 9, e20018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, B.D. The Sequential Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Procedure as an Alternative for Determining the Number of Factors in Common-Factor Analysis: A Monte Carlo Simulation; Oklahoma State University: Stillwater, OK, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, T. An Exploratory Factor Analysis and Reliability Analysis of the Student Online Learning Readiness (SOLR) Instrument; Purdue University: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babib, B.; Anderson, R.; Tatham, R. Multivariate data analysis. In Analysis; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, B.; Onsman, A.; Brown, T. Exploratory factor analysis: A five-step guide for novices. Australas. J. Paramed. 2010, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, E.; Bryman, A.; Harley, B. Business Research Methods; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cooksey, R.W.; Cooksey, R.W. Descriptive statistics for summarising data. In Illustrating Statistical Procedures: Finding Meaning in Quantitative Data; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 61–139. [Google Scholar]

- Michel, J.O.; Zwickle, A. The effect of information source on higher education students’ sustainability knowledge. Environ. Educ. Res. 2021, 27, 1080–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Yu, L.; Wu, H. Awareness of sustainable development goals among students from a Chinese senior high school. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nuaimi, S.R.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G. Sustainable consumption and education for sustainability in higher education. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcmillin, J.; Dyball, R. Developing a whole-of-university approach to educating for sustainability: Linking curriculum, research and sustainable campus operations. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 3, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desha, C.J.; Hargroves, K.; Smith, M.H. Addressing the time lag dilemma in curriculum renewal towards engineering education for sustainable development. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2009, 10, 184–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, H.; Nordén, B. Working with the divides: Two critical axes in development for transformative professional practices. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2017, 18, 666–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.; Mader, M.; Zimmermann, F.; Çabiri, K. Training sessions fostering transdisciplinary collaboration for sustainable development: Albania and Kosovo case studies. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2017, 18, 738–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, C.F.; Davim, J.P. Sustainability in the Modernization of Higher Education: Curricular Transformation and Sustainable Campus—A Literature Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasdemir, C.; Gazo, R. Integrating sustainability into higher education curriculum through a transdisciplinary perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 265, 121759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovais, D. Students’ sustainability consciousness with the three dimensions of sustainability: Does the locus of control play a role? Reg. Sustain. 2023, 4, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shittu, O. Emerging sustainability concerns and policy implications of urban household consumption: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 246, 119034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]