The Joint Effects of Firm’s Globalization and ESG Rating on Financial Performance: Evidence from Food Industry in Taiwan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Theoretical Foundation

2.2. The Impact of Internationalization on Firm Performance

2.3. ESG and Firm’s Performance

2.4. Testable Hypotheses

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Sample

3.2. Empirical Model

4. Empirical Results and Analysis

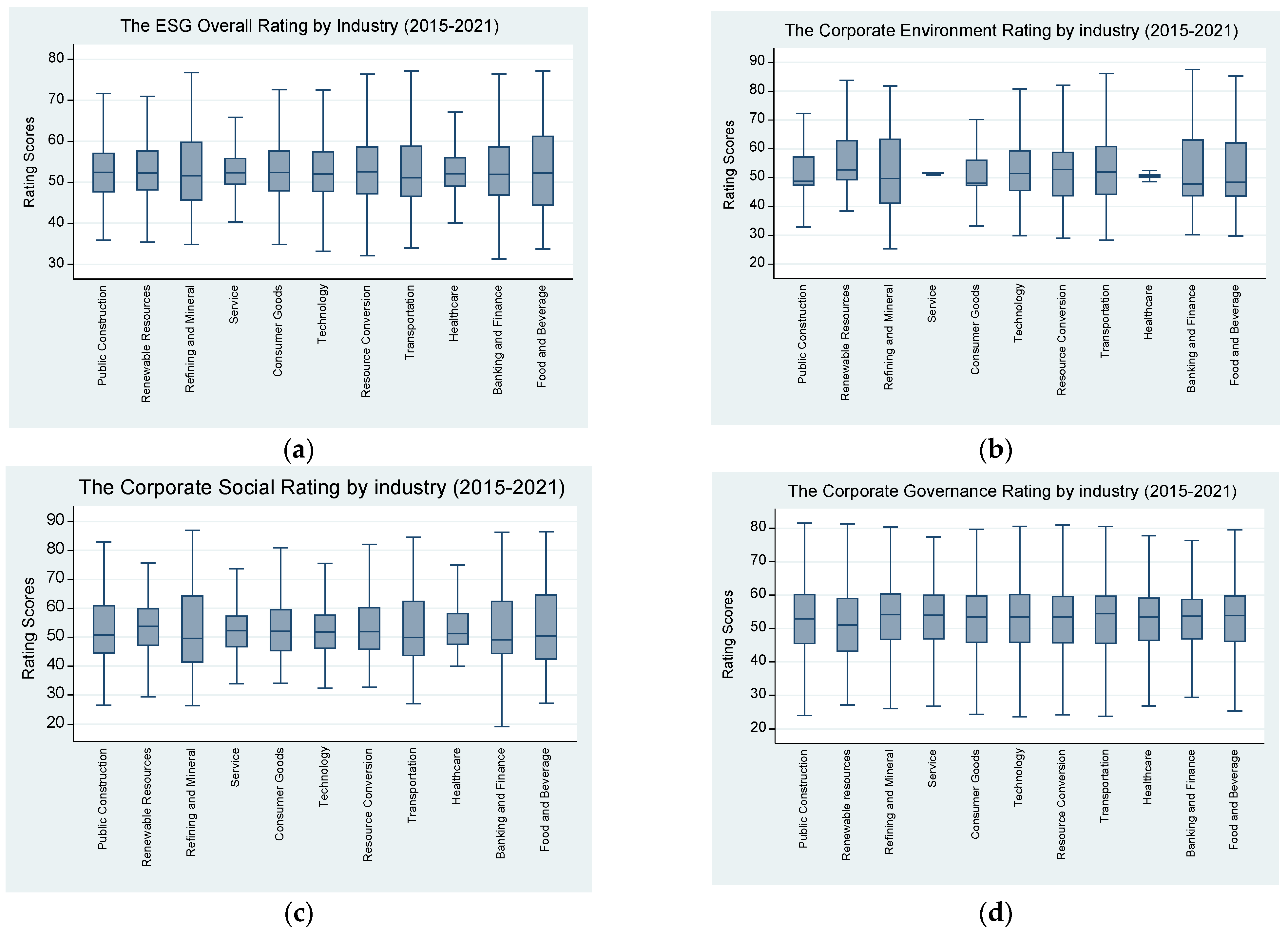

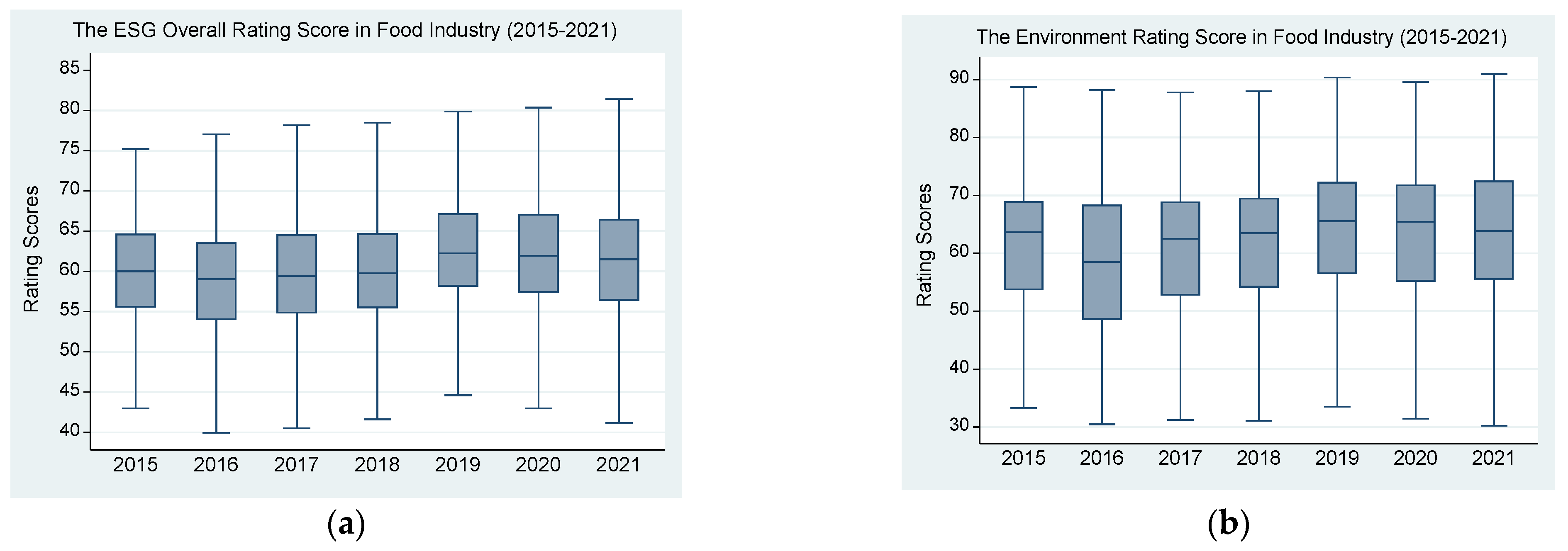

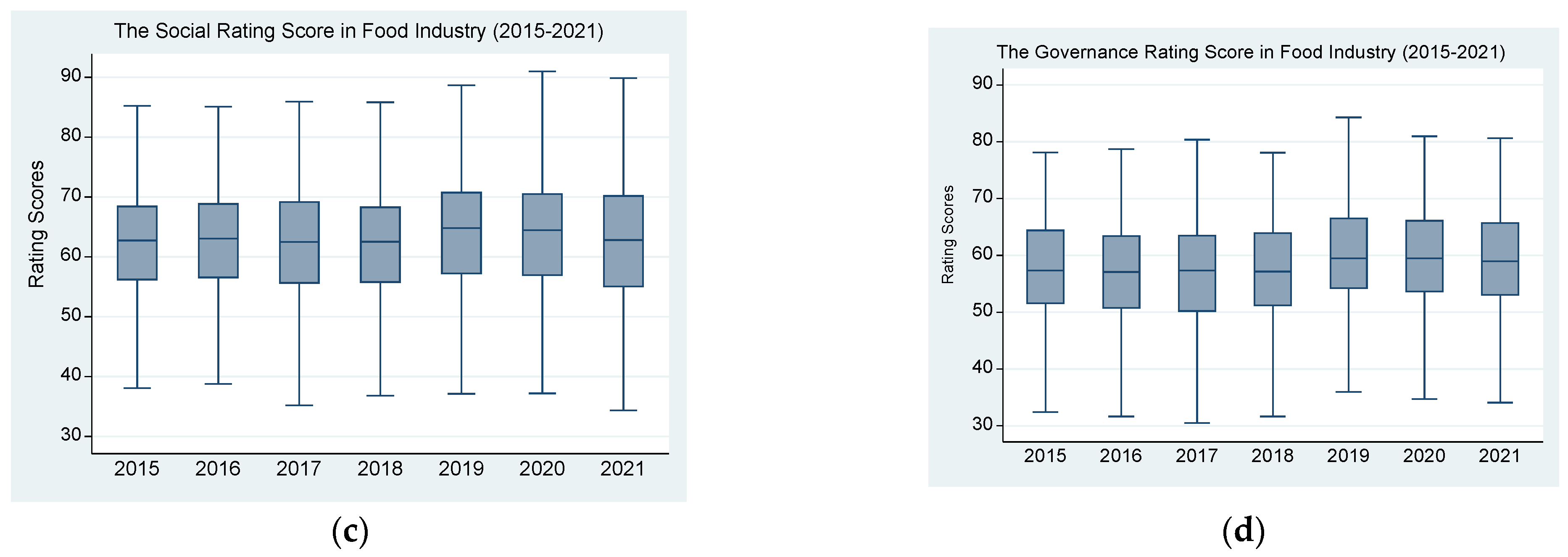

4.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

4.2. Fundamental Analysis

4.2.1. Time Trend and Distribution on ESG Rating Scores in the Food Industry

4.2.2. Time Trend and Distribution on International Diversification of Food Manufacturers

4.3. The Joint Impact of International Diversification and ESG on Firm’s Performance

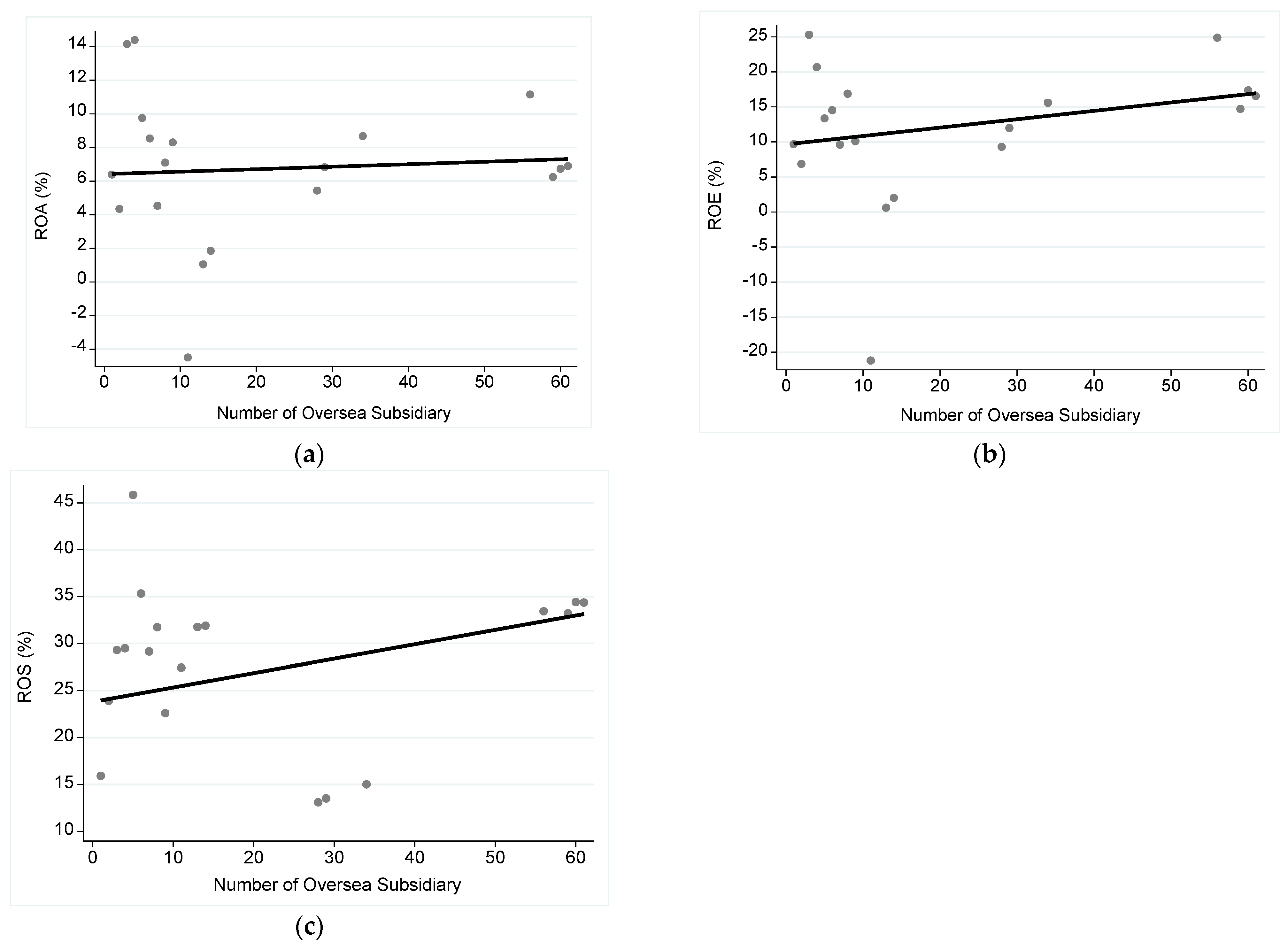

4.3.1. The Direct Impact of International Diversification on the Financial Performance

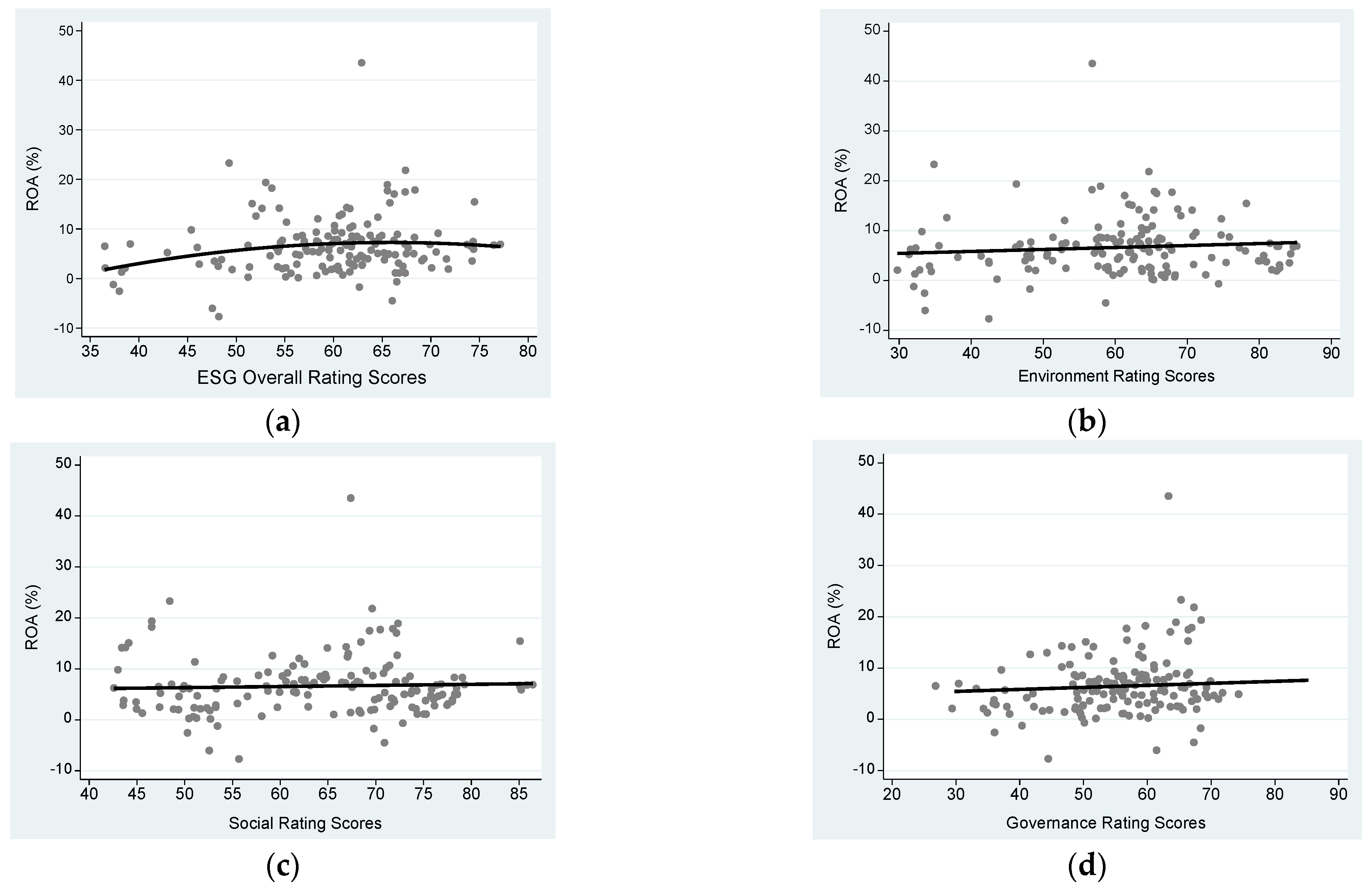

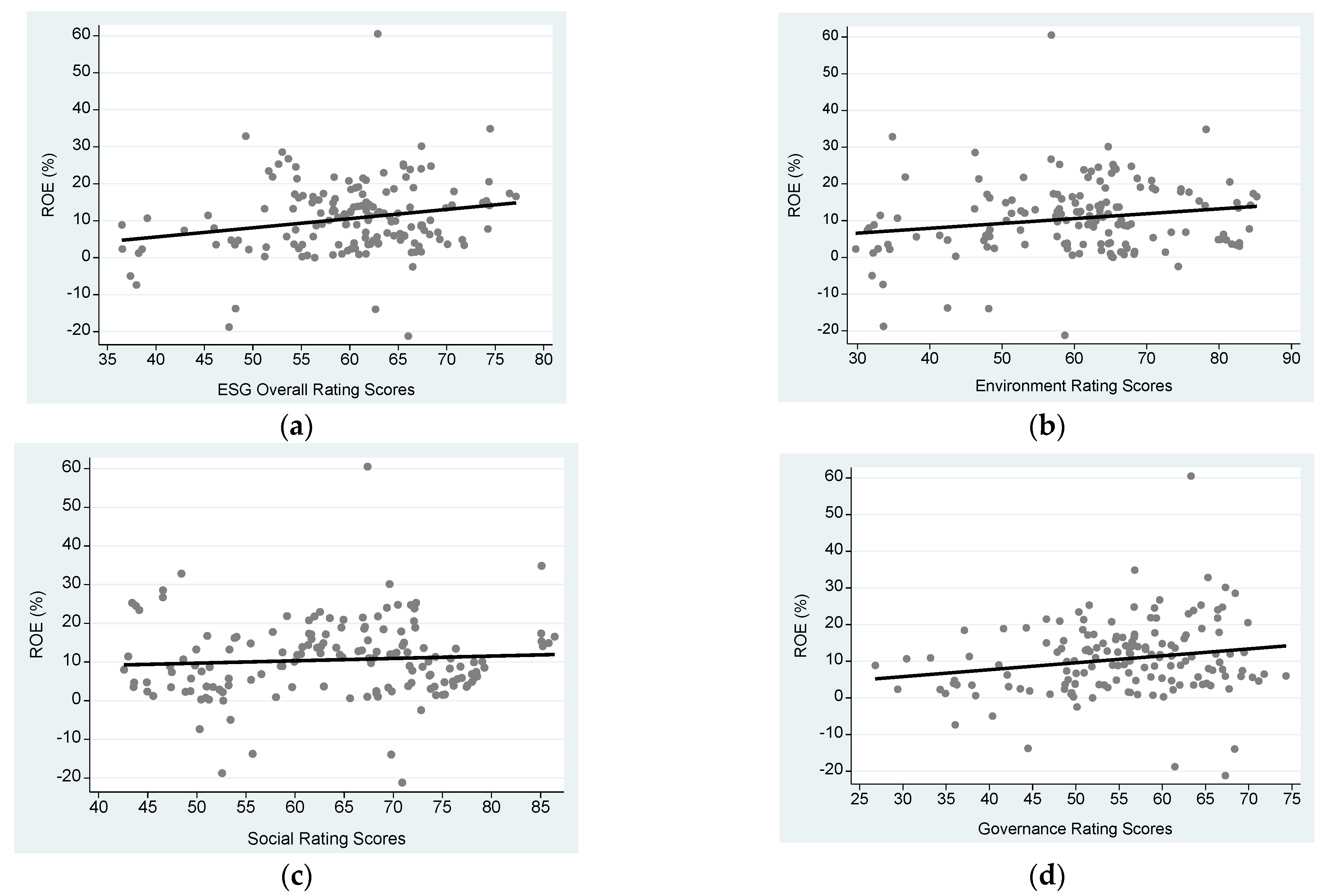

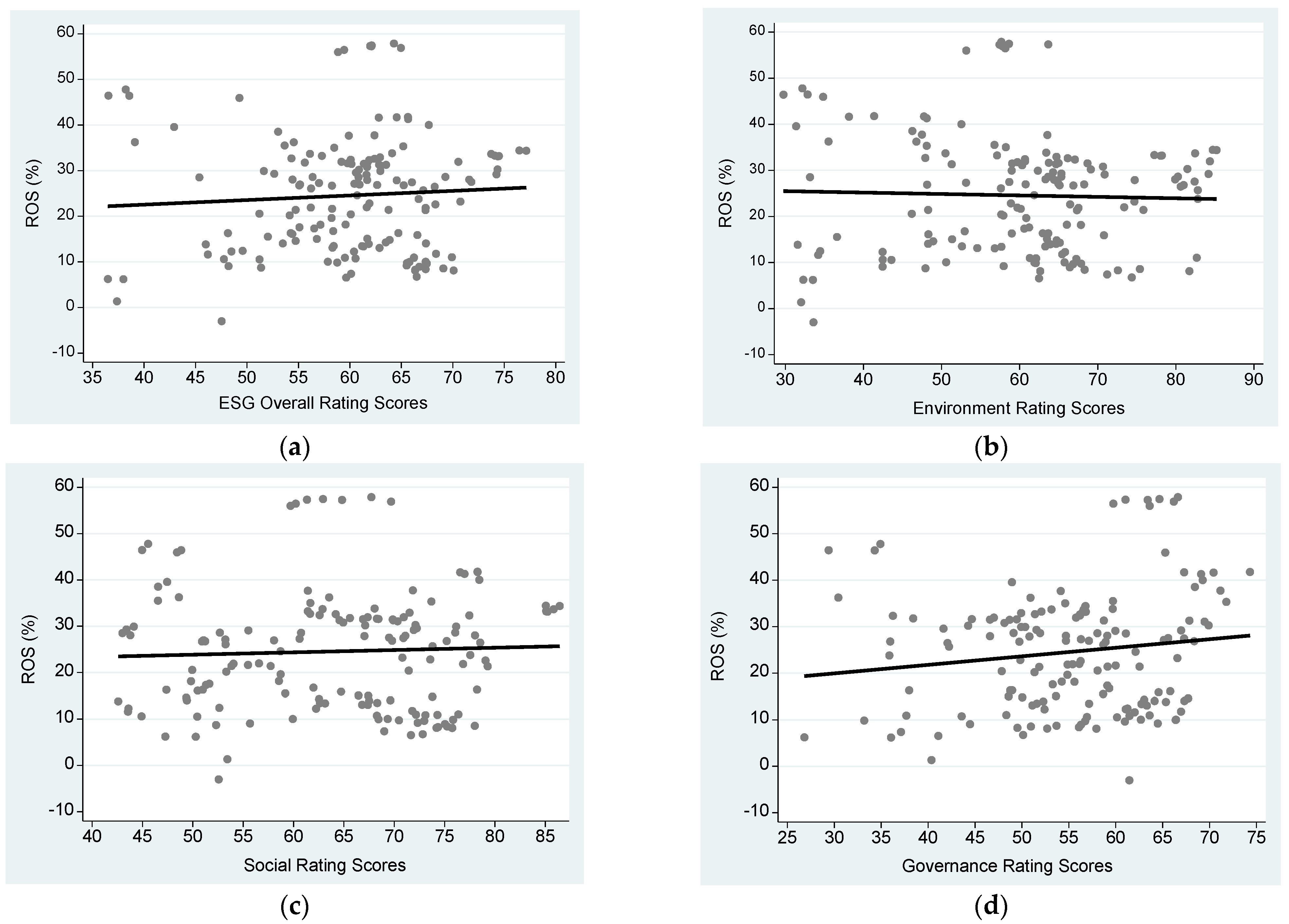

4.3.2. The Direct Impact of ESG Rating Scores on the Financial Performance

4.3.3. The Joint Impact of International Diversification and ESG Performance on the Financial Performance

4.4. Endogeneity Tests: Instrumental Variable Method

5. Managerial and Policy Implications

5.1. Managerial Implications

5.2. Policy Implications

6. Conclusions, Limitation and Future Research

6.1. Concluding Remarks

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gallo, A.; Operato, L.; Masoero, G.; Panzeri, A.; Rondoni, N. The integrated ESG approach to assess sustainability: An application in the food and beverage sector. In Proceedings of the Changeable, Agile, Reconfigurable and Virtual Production Conference and the World Mass Customization & Personalization Conference, Bologna, Italy, 20–23 June 2023; pp. 423–431. [Google Scholar]

- Pinedo-Lopez, J.; Baena-Navarro, R.E.; Carriazo-Regino, Y.; Urrea-Ortiz, A.C.; Reyes-Guevara, D.L. Sustainability strategies: A proposal for food sector SMEs, based on the integration of life cycle assessment and ESG strategies. J. Infrastruct. Policy Dev. 2024, 8, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizovskaya, V.V.; Moldovan, A.A. CSR and ESG Transformation of Russian Brands: Cases of Food Industry Companies. In Finance, Economics, and Industry for Sustainable Development, Proceedings of the ECOOP ’87: European Conference on Object-Oriented Programming, Paris, France, 15–17 June 1987; Rumyantseva, A., Anyigba, H., Sintsova, E., Vasilenko, N.V., Eds.; Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Porechenkova, V.; Wang, Y. CSR Reporting Practices: A Cross-Time Comparison of the Food & Beverage and Energy Industries in the US Through Topic Modeling. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2024, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Paridhi; Ritika. Impact of ESG Disclosures on Corporate Financial Performance: An Industry-Specific Analysis of Indian Firms. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2025, 8, e70055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O.; Brotherton, M.C.; Talbot, D.; Guillaumie, L. Assessing and managing environmental, social, and governance risks in agri-food companies. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 5690–5708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatraman, N.; Ramanujam, V. Measurement of business performance in strategy research: A comparison of approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1986, 11, 801–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M. The Situation of Taiwan’s Agricultural Trade and Export Strategy; FFTC Agricultural Policy Platform: Taipei, Taiwan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Muhamad, N.; Adham, K.A.; Said, M.F.; Nasir, N.M. Exploring internationalization of Halal Taiwan: Analysis of Taiwan’s halal food products in Malaysia. Geogr. Malays. J. Soc. Space 2020, 16, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.Y.; Huatuco, L.H. Agri-Food Supply Chain for Mitigation of Volatilities in the Role of Intermediary: A Case Study of a Mushroom Trading Company in Taiwan. In Sustainable Design and Manufacturing; Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics; Springer: Crete, Greece, 2016; pp. 447–454. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.C.; Li, S.P.; Lai, J.C.; Chan, Y.K.; Hsieh, M.Y. Research on the international sustainable practice of the Taiwanese food and agricultural education law under the current global food security challenges. Foods 2023, 12, 2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, J.; Wiedersheim-Paul, F. Internationalization of the firm-Four Swedish cases. J. Manag. 1975, 12, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah Shayan, N.; Mohabbati-Kalejahi, N.; Alavi, S.; Zahed, M.A. Sustainable development goals (SDGs) as a framework for corporate social responsibility (CSR). Sustainability 2022, 14, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y. Effects of CSR motives on authenticity and attitude in the food and beverage franchise sectors. Korean J. Franch. Manag. 2023, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y. ESG Implementation, Investor Confidence and Listed Companies’ Performance. J. Environ. Econ. 2021, 6, 22–39. [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg, H.; Alnoor, A.; Tiberius, V. Environmental, social, and governance ratings and financial performance: Evidence from the European food industry. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 2471–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, L.S.; Luostarinen, R. Internationalization: Evolution of a concept. J. Gen. Manag. 1988, 14, 34–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, J.; Wiedersheim-Paul, F. The Internationalization of the Firm—Four Swedish Cases 1. In International Business; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; pp. 127–144. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, R.M. Multinationality and performance among British manufacturing companies. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1987, 18, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hymer, S.H. The International Operations of National Firms, a Study of Direct Foreign Investment; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Kogut, B. Designing global strategies: Comparative and competitive value-added chains. Sloan Manag. Rev. 1985, 26, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, H.P.; Baker, H.K.; Powell, G.E. Globalization and diversification strategy: A managerial perspective. Scand. J. Manag. 2015, 31, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filatotchev, I.; Piesse, J. R&D, internationalization and growth of newly listed firms: European evidence. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2009, 40, 1260–1276. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.W.; Beamish, P.W. International diversification and firm performance: The S-curve hypothesis. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 598–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knickerbocker, F.T. Oligopolistic reaction and multinational enterprise. Int. Exec. 1973, 15, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O. The Economic Institutions of Capitalism; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, P.; Casson, M. The Future of the Multinational Enterprise; Homes & Meier: London, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, L.; Pantzalis, C. Valuation of the operating flexibility of multinational corporations. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1996, 27, 633–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobillo, A.M.; López-Iturriaga, F.; Tejerina-Gaite, F. Firm performance and international diversification: The internal and external competitive advantages. Int. Bus. Rev. 2010, 19, 607–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantzalis, C. Does location matter? An empirical analysis of geographic scope and MNC market valuation. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2001, 32, 133–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gande, A.; Schenzler, C.; Senbet, L.W. Valuation effects of global diversification. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2009, 40, 1515–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, D. Measuring the degree of internationalization of a firm. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1994, 25, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, L.; Ramaswamy, K. An empirical examination of the form of the relationship between multinationality and performance. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1999, 30, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falavigna, G.; Giannini, V.; Ippoliti, R. Internationalization and financial constraints: Opportunities, obstacles, and strategies. Int. Econ. 2024, 179, 100510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhu, N. The Effect of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Performance on Corporate Financial Performance in China: Based on the Perspective of Innovation and Financial Constraints. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwens, C.; Zapkau, F.B.; Bierwerth, M.; Isidor, R.; Knight, G.; Kabst, R. International entrepreneurship: A meta-analysis on the internationalization and performance relationship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2018, 42, 734–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q.T.K.; Kim, S. The multinationality and performance relationship: Revisiting the literature and exploring the implications. Int. Bus. Rev. 2020, 29, 101670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M.; Li, S.; Al-Omush, A.; Al-Nimer, M. SMEs’ internationalization: Mapping the field through finance, ITC, and social ties. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, T.; Klein, F.; Schmidt, S. The effect of internationalization on firm capital structure: A meta-analysis and exploration of institutional contingencies. Int. Bus. Rev. 2018, 27, 1239–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmuck, A.; Lagerström, K.; Sallis, J.E. Patterns of inconsistency: A literature review of empirical studies on the multinationality–performance relationship. Crit. Perspect. Int. Bus. 2022, 18, 123–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Kotabe, M.; Zhang, F.; Hao, A.; Paul, J.; Wang, C. The determinants and performance of early internationalizing firms: A literature review and research agenda. Int. Bus. Rev. 2020, 29, 101662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zonta, T.C.; Amal, M. Internationalization and innovation: The case of a born global from Brazil. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2018, 13, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calheiros-Lobo, N.; Vasconcelos Ferreira, J.; Au-Yong-Oliveira, M. SME internationalization and export performance: A systematic review with bibliometric analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.C.; Hung, M.; Wang, Y. The effect of mandatory CSR disclosure on firm profitability and social externalities: Evidence from China. J. Account. Econ. 2018, 65, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Keefe, M.O.C. Rookie directors and firm performance: Evidence from China. J. Corp. Financ. 2020, 60, 101511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, C.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, W. Need for speed: High-speed rail and firm performance. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 66, 101830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wei, Z.; Xie, F. Do women directorsimprove firm performance in China. J. Corp. Financ. 2014, 28, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Zou, G. Political connection, CEO gender, and firm performance. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 71, 101918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuer, M.; DeHaan, E.D. Using and interpreting fixed effects models. J. Account. Res. 2024, 62, 1183–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, W.H. Econometric Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, R.B.; Almeida, H.; Ferreira, D. Understanding the relationship between founder-CEOs and firm performance. J. Financ. Econ. 2009, 92, 197–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Liu, Y.; Qian, Y. Corporate social responsibility and firm value: A comparative study of U.S. and European firms. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 136, 687–707. [Google Scholar]

| Pillars | Environment (S) | Society (S) | Governance (G) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Topics (16 items) | Greenhouse Gas Emissions | Human Rights and Community Relations | Business Model and Level of Innovation |

| Energy Management | Data Security | Leadership Management | |

| Water and Wastewater Management | Product Quality and Safety | Control and Seats | |

| Waste and Toxic Substances Management | Employee Information Statistics | The Equitable Treatment of Shareholders | |

| Ecological Impact | Employee Health and Safety | Information Transparency of Corporate Governance | |

| Employee Diversity |

| Variables | Observations | Mean | Standard Deviation | 10% Percentile | Median | 90% Percentile | Relative Importance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Company operating performance | |||||||

| Return on total assets (ROA) (%) | 154 | 6.618 | 5.902 | 1.130 | 6.025 | 14.150 | 132 |

| Return on total equity (ROE) (%) | 154 | 10.564 | 9.874 | 1.220 | 10.085 | 21.870 | 211 |

| Total return on sales (ROS) (%) | 154 | 24.564 | 12.810 | 9.210 | 26.285 | 40.020 | 491 |

| Panel B: International diversification | |||||||

| Number of overseas subsidiaries | 154 | 7.344 | 12.931 | 1.000 | 2.000 | 14.000 | 147 |

| Panel C: Firm’s ESG rating performance | |||||||

| ESG overall scores | 154 | 60.009 | 8.279 | 48.490 | 61.065 | 69.080 | 1200 |

| Environmental scores | 154 | 59.944 | 13.423 | 38.150 | 61.970 | 78.200 | 1199 |

| Social scores | 154 | 64.112 | 11.202 | 48.430 | 66.630 | 77.550 | 1282 |

| Corporate governance scores | 154 | 55.164 | 9.753 | 41.090 | 56.275 | 66.970 | 1103 |

| Panel D: Firm’s level controlling variables | |||||||

| Research and development expense rate (%) | 154 | 0.587 | 0.693 | 0.000 | 0.315 | 1.660 | 12 |

| Debt ratio (%) | 154 | 40.890 | 16.532 | 19.150 | 40.495 | 63.540 | 818 |

| Ln (total assets) | 154 | 8.678 | 0.823 | 7.575 | 8.572 | 9.570 | 174 |

| Panel E: ANOVA testing | |||||||

| Variables | ESG-ranked groups | ANOVA | |||||

| Low (30%) | Medium (40%) | High (30%) | F-statstics | (p-value) | |||

| ESG < 58.3 | 58.3 < = ESG < 63.51 | ESG < = 63.51 | |||||

| Return on total assets (ROA) (%) | 5.615 | 7.098 | 7.159 | 1.140 | (0.323) | ||

| Return on total equity (ROE) (%) | 9.079 | 11.277 | 11.362 | 0.890 | (0.414) | ||

| Total return on sales (ROS) (%) | 22.664 | 27.332 | 23.800 | 1.850 | (0.161) | ||

| Number of overseas subsidiaries | 3.673 | 7.660 | 10.712 | 4.030 ** | (0.020) | ||

| Research and development expense rate (%) | 0.664 | 0.525 | 0.570 | 0.530 | (0.588) | ||

| Debt ratio (%) | 40.809 | 42.165 | 39.746 | 0.270 | (0.763) | ||

| Ln (total assets) | 8.348 | 8.533 | 9.146 | 16.000 *** | (0.000) | ||

| Company | ESG Overall Scores | Environment Scores | Social Scores | Governance Scores |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jiage | 61.767 | 69.321 | 66.557 | 47.739 |

| Nanqiao | 56.697 | 54.526 | 60.831 | 53.566 |

| CP Group | 60.481 | 58.893 | 62.346 | 59.697 |

| Tairoun | 49.673 | 42.177 | 46.696 | 61.289 |

| Wei Chuan | 67.947 | 66.641 | 70.637 | 67.919 |

| Ve Wong | 61.139 | 61.931 | 62.779 | 58.177 |

| Greatwall | 59.351 | 57.686 | 66.387 | 51.924 |

| TTET | 66.600 | 63.550 | 70.594 | 64.559 |

| Oceanic | 46.663 | 38.367 | 52.056 | 53.063 |

| Ten Ren | 61.960 | 58.073 | 63.776 | 63.613 |

| Hunya | 58.267 | 66.021 | 53.243 | 56.789 |

| AGV | 60.327 | 61.689 | 69.599 | 46.866 |

| Taisun | 57.671 | 62.427 | 55.487 | 55.593 |

| Fwusow | 68.003 | 74.493 | 75.150 | 52.001 |

| FOPCO | 62.583 | 64.201 | 73.234 | 47.066 |

| UNI | 74.404 | 81.463 | 83.381 | 56.53 |

| LHIHC | 64.797 | 63.647 | 76.030 | 51.38 |

| Lian Hwa Foods | 58.437 | 60.391 | 56.451 | 59.006 |

| Taiyen | 64.844 | 46.214 | 76.296 | 70.479 |

| Shin Tai Industry | 40.000 | 36.141 | 47.153 | 34.684 |

| Sunjuice | 51.437 | 51.714 | 45.124 | 59.357 |

| HeySong | 67.149 | 79.207 | 76.664 | 42.313 |

| Mean | 60.009 * | 59.944 * | 64.112 * | 55.164 * |

| p-value (1%) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) |

| Overseas Subsidiary Countries | Number | Percentage (%) | Overseas Subsidiary Countries | Number | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brunei | 6 | 0.40 | Philippines | 30 | 2.01 |

| Switzerland | 7 | 0.47 | Malaysia | 30 | 2.01 |

| Myanmar | 7 | 0.47 | USA | 39 | 2.62 |

| Spain | 7 | 0.47 | Singapore | 57 | 3.83 |

| India | 9 | 0.60 | Thailand | 68 | 4.56 |

| South Korea | 11 | 0.74 | Vietnam | 96 | 6.44 |

| Panama | 11 | 0.74 | Samoa | 101 | 6.78 |

| Cambodia | 13 | 0.87 | cayman islands | 208 | 13.96 |

| Japan | 20 | 1.34 | British Virgin Islands | 348 | 23.4 |

| Indonesia | 25 | 1.68 | Hong Kong | 397 | 26.6 |

| Variables | Firm’s Financial Performance Measures | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ROA (%) | ROE (%) | ROS (%) | |

| Number of overseas subsidiaries | 0.070 *** | 0.166 *** | 0.221 *** |

| (3.332) | (3.955) | (6.024) | |

| Research and development expense rate (%) | 0.878 | 2.023 * | 7.204 *** |

| (1.618) | (1.911) | (15.288) | |

| Debt ratio (%) | −0.077 *** | −0.008 | −0.155 *** |

| (−3.849) | (−0.210) | (−7.317) | |

| Ln (total assets) | 1.783 *** | 3.271 *** | −6.942 *** |

| (4.651) | (5.765) | (−12.700) | |

| Constant | −6.962 ** | −20.082 *** | 85.692 *** |

| (−2.052) | (−3.926) | (16.644) | |

| Firm Fixed Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year Fixed Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 154 | 154 | 154 |

| χ2 | 36.826 *** | 44.893 *** | 1047.229 *** |

| Variables | Firm’s Financial Performance Measures | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ROA (%) | ROE (%) | ROA (%) | |

| Panel A: Firm’s ESG overall scores | |||

| ESG overall scores | 0.074 ** | 0.164 *** | 0.496 *** |

| (2.035) | (2.704) | (11.043) | |

| Research and development expense rate (%) | 0.280 | 1.017 | 6.735 *** |

| (0.554) | (0.998) | (20.321) | |

| Debt ratio (%) | −0.048 ** | 0.056 | −0.123 *** |

| (−2.569) | (1.552) | (−7.354) | |

| Ln (total assets) | 1.289 *** | 2.038 *** | −9.609 *** |

| (3.075) | (3.269) | (−16.959) | |

| constant | −7.214 ** | −19.490 *** | 79.395 *** |

| (−2.104) | (−3.714) | (14.781) | |

| Firm Fixed Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year Fixed Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 154 | 154 | 154 |

| χ2 | 29.595 *** | 34.238 *** | 1421.277 *** |

| Panel B: Firm’s Environment rating scores | |||

| Environment rating scores | 0.042 * | 0.109 *** | 0.188 *** |

| (1.737) | (2.596) | (5.883) | |

| Research and development expense rate (%) | 0.430 | 1.454 | 7.248 *** |

| (0.848) | (1.495) | (13.681) | |

| Debt ratio (%) | −0.052 *** | 0.043 | −0.112 *** |

| (−2.767) | (1.188) | (−5.206) | |

| Ln (total assets) | 1.384 *** | 2.055 *** | −8.876 *** |

| (3.378) | (3.369) | (−16.405) | |

| constant | −6.079 * | −16.176 *** | 90.547 *** |

| (−1.769) | (−3.091) | (17.038) | |

| Firm Fixed Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year Fixed Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 154 | 154 | 154 |

| χ2 | 27.801 *** | 31.089 *** | 772.180 *** |

| Panel C: Firm’s Social rating scores | |||

| Social rating scores | −0.022 | −0.017 | 0.336 *** |

| (−0.722) | (−0.312) | (11.317) | |

| Research and development expense rate (%) | 0.296 | 1.133 | 5.905 *** |

| (0.604) | (1.161) | (15.888) | |

| Debt ratio (%) | −0.048 *** | 0.063 * | −0.108 *** |

| (−2.734) | (1.836) | (−6.555) | |

| Ln (total assets) | 1.918 *** | 3.140 *** | −9.837 *** |

| (4.320) | (4.526) | (−20.324) | |

| constant | −6.843 ** | −18.751 *** | 89.456 *** |

| (−1.965) | (−3.498) | (21.049) | |

| Firm Fixed Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year Fixed Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 154 | 154 | 154 |

| χ2 | 31.075 *** | 29.935 *** | 1524.893 *** |

| Panel D: Firm’s Governance rating scores | |||

| Governance rating scores | 0.115 *** | 0.182 *** | 0.077 ** |

| (3.888) | (3.838) | (2.088) | |

| Research and development expense rate (%) | 0.065 | 0.639 | 7.407 *** |

| (0.130) | (0.637) | (15.943) | |

| Debt ratio (%) | −0.053 *** | 0.056 * | −0.105 *** |

| (−2.999) | (1.714) | (−5.601) | |

| Ln (total assets) | 1.564 *** | 2.721 *** | −8.333 *** |

| (4.304) | (4.962) | (−14.550) | |

| constant | −10.957 *** | −25.090 *** | 92.642 *** |

| (−3.171) | (−4.717) | (17.478) | |

| Firm Fixed Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year Fixed Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 154 | 154 | 154 |

| χ2 | 46.210 *** | 46.423 *** | 1090.562 *** |

| Variables | Firm’s Financial Performance Measures | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ROA (%) | ROE (%) | ROA (%) | |

| Panel A: Firm’s ESG overall scores | |||

| Number of overseas subsidiaries * ESG overall scores | 0.093 *** | 0.236 *** | 0.317 *** |

| (3.125) | (3.898) | (7.988) | |

| Research and development expense rate (%) | 0.806 | 1.932 * | 7.327 *** |

| (1.486) | (1.825) | (15.689) | |

| Debt ratio (%) | −0.075 *** | −0.005 | −0.158 *** |

| (−3.724) | (−0.137) | (−7.517) | |

| Ln (total assets) | 1.746 *** | 3.195 *** | −7.062 *** |

| (4.570) | (5.655) | (−13.309) | |

| Constant | −6.621 * | −19.359 *** | 86.942 *** |

| (−1.959) | (−3.800) | (17.272) | |

| Firm Fixed Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year Fixed Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 154 | 154 | 154 |

| χ2 | 35.790 *** | 44.489 *** | 1058.401 *** |

| Panel B: Firm’s Environment rating scores | |||

| Number of overseas subsidiaries * Environment rating scores | 0.080 *** | 0.211 *** | 0.294 *** |

| (2.826) | (3.599) | (9.538) | |

| Research and development expense rate (%) | 0.761 | 1.883 * | 7.387 *** |

| (1.403) | (1.780) | (15.753) | |

| Debt ratio (%) | −0.072 *** | −0.001 | −0.160 *** |

| (−3.624) | (−0.023) | (−7.599) | |

| Ln (total assets) | 1.726 *** | 3.144 *** | −7.106 *** |

| (4.517) | (5.566) | (−13.514) | |

| Constant | −6.457 * | −18.958 *** | 87.426 *** |

| (−1.909) | (−3.722) | (17.479) | |

| Firm Fixed Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year Fixed Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 154 | 154 | 154 |

| χ2 | 34.488 *** | 42.274 *** | 1067.359 *** |

| Panel C: Firm’s Social rating scores | |||

| Number of overseas subsidiaries * Social rating scores | 0.082 *** | 0.208 *** | 0.277 *** |

| (3.162) | (3.907) | (7.446) | |

| Research and development expense rate (%) | 0.800 | 1.929 * | 7.309 *** |

| (1.482) | (1.823) | (15.709) | |

| Debt ratio (%) | −0.073 *** | −0.002 | −0.157 *** |

| (−3.686) | (−0.065) | (−7.448) | |

| Ln (total assets) | 1.747 *** | 3.192 *** | −7.067 *** |

| (4.568) | (5.641) | (−13.258) | |

| Constant | −6.659 ** | −19.402 *** | 86.957 *** |

| (−1.968) | (−3.803) | (17.216) | |

| Year Fixed Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 154 | 154 | 154 |

| χ2 | 35.834 *** | 44.809 *** | 1054.973 *** |

| Panel D: Firm’s Governance rating scores | |||

| Number of overseas subsidiaries * Governance rating scores | 0.130 *** | 0.312 *** | 0.419 *** |

| (3.416) | (4.143) | (7.141) | |

| Research and development expense rate (%) | 0.863 | 1.966 * | 7.276 *** |

| (1.588) | (1.855) | (15.551) | |

| Debt ratio (%) | −0.079 *** | −0.013 | −0.158 *** |

| (−3.905) | (−0.345) | (−7.473) | |

| Ln (total assets) | 1.777 *** | 3.267 *** | −7.039 *** |

| (4.657) | (5.788) | (−13.207) | |

| Constant | −6.839 ** | −19.848 *** | 86.649 *** |

| (−2.027) | (−3.900) | (17.166) | |

| Firm Fixed Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year Fixed Effect | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 154 | 154 | 154 |

| χ2 | 37.488 *** | 46.044 *** | 1055.602 *** |

| Panel A. Direct impact of internationalization and ESG rating scores on financial performance of food company using Instrumental variable method | |||||||||||||||||||

| Variables | Financial Performance Measures | Financial Performance Measures | Financial Performance Measures | Financial Performance Measures | Financial Performance Measures | ||||||||||||||

| ROA | ROE | ROS | ROA | ROE | ROS | ROA | ROE | ROS | ROA | ROE | ROS | ROA | ROE | ROS | |||||

| Model (1) | Model (2) | Model (3) | Model (1) | Model (2) | Model (3) | Model (1) | Model (2) | Model (3) | Model (1) | Model (2) | Model (3) | Model (1) | Model (2) | Model (3) | |||||

| Constant | −39.600 *** | −65.085 *** | 95.947 *** | −18.827 *** | −39.883 *** | 85.438 *** | −16.021 *** | −32.316 *** | 106.310 *** | −20.966 *** | −55.631 *** | 101.953 *** | −47.450 ** | −101.398 ** | 48.329 | ||||

| (−2.674) | (−2.975) | (8.808) | (−2.935) | (−3.504) | (9.333) | (−2.924) | (−3.136) | (7.242) | (−2.632) | (−2.741) | (12.000) | (−2.129) | (−2.157) | (1.168) | |||||

| Number of overseas subsidiaries | 0.881 *** | 1.503 *** | 0.434 ** | ||||||||||||||||

| (2.837) | (3.637) | (2.295) | |||||||||||||||||

| ESG overall scores | 0.290 ** | 0.715 *** | 0.810 *** | ||||||||||||||||

| (2.075) | (2.876) | (4.052) | |||||||||||||||||

| Environmental scores | 0.263 *** | 0.591 *** | 0.469 ** | ||||||||||||||||

| (3.121) | (3.725) | (1.978) | |||||||||||||||||

| Social scores | 0.388 *** | 1.021 *** | 0.243 ** | ||||||||||||||||

| (2.885) | (2.918) | (2.286) | |||||||||||||||||

| Corporate governance scores | 0.604 * | 1.142 * | 1.233 * | ||||||||||||||||

| (1.826) | (1.772) | (1.685) | |||||||||||||||||

| Research and development expense rate (%) | 2.859 ** | 4.831 ** | 6.441 *** | 1.134 | 1.850 | 5.936 *** | −0.225 | 0.528 | 4.401 ** | −1.731 | −2.516 | 5.628 *** | 0.060 | 1.246 | 1.303 | ||||

| (2.241) | (2.207) | (5.266) | (1.649) | (1.499) | (6.036) | (−0.273) | (0.342) | (2.234) | (−1.501) | (−1.016) | (5.519) | (0.035) | (0.360) | (0.496) | |||||

| debt_ratio | −0.248 *** | −0.371 *** | −0.223 *** | −0.110 *** | −0.076 | −0.186 *** | −0.112 *** | −0.097 | −0.179 *** | −0.132 *** | −0.221 *** | −0.149 *** | −0.114 * | −0.158 | −0.026 | ||||

| (−4.287) | (−3.601) | (−3.731) | (−3.717) | (−1.412) | (−4.378) | (−3.506) | (−1.623) | (−3.098) | (−3.895) | (−3.190) | (−3.582) | (−1.892) | (−1.298) | (−0.252) | |||||

| Ln (Total assets) | 5.554 *** | 8.865 *** | −7.980 *** | 1.366 * | 1.099 | −12.139 *** | 1.267 * | 1.182 | −12.130 *** | 0.947 | 1.101 | −10.393 *** | 2.888 * | 6.258 * | −10.541 *** | ||||

| (3.508) | (3.728) | (−6.665) | (1.753) | (0.794) | (−10.909) | (1.874) | (0.930) | (−5.887) | (0.941) | (0.463) | (−9.984) | (1.880) | (1.866) | (−4.592) | |||||

| Firm fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Year fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Observations | 154 | 154 | 154 | 154 | 154 | 154 | 154 | 154 | 154 | 154 | 154 | 154 | 154 | 154 | 154 | ||||

| Adjuested R2 | 0.068 | 0.088 | 0.491 | 0.143 | 0.071 | 0.613 | 0.125 | 0.077 | 0.510 | 0.139 | 0.060 | 0.606 | 0.133 | 0.075 | 0.269 | ||||

| F-statistics | 6.978 *** | 5.744 *** | 30.299 *** | 8.893 *** | 5.854 *** | 52.185 *** | 9.503 *** | 6.641 *** | 12.248 *** | 9.504 *** | 7.074 *** | 42.118 *** | 5.970 *** | 5.048 *** | 7.519 *** | ||||

| (p-value) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | ||||

| Panel B. The joint impact of internationalization and ESG rating scores on financial performance of food company using Instrumental variable method | |||||||||||||||||||

| Variables | Financial Performance Measures | Financial Performance Measures | Financial Performance Measures | Financial Performance Measures | |||||||||||||||

| ROA | ROE | ROS | ROA | ROE | ROS | ROA | ROE | ROS | ROA | ROE | ROS | ||||||||

| Model (1) | Model (2) | Model (3) | Model (1) | Model (2) | Model (3) | Model (1) | Model (2) | Model (3) | Model (1) | Model (2) | Model (3) | ||||||||

| Constant | −39.248 ** | −64.090 *** | 96.835 *** | −36.404 ** | −62.976 ** | 96.558 *** | −30.408 *** | −50.832 *** | 99.328 *** | −26.041 *** | −49.058 *** | 98.616 *** | |||||||

| (−2.514) | (−2.751) | (8.717) | (−2.269) | (−2.488) | (7.678) | (−2.693) | (−2.954) | (11.478) | (−3.198) | (−3.412) | (11.357) | ||||||||

| Number of overseas subsidiaries × ESG overall scores | 1.308 *** | 2.237 *** | 0.666 ** | ||||||||||||||||

| (2.639) | (3.387) | (2.355) | |||||||||||||||||

| Number of overseas subsidiaries × Environmental scores | 1.270 ** | 2.248 *** | 0.786 ** | ||||||||||||||||

| (2.444) | (3.090) | (2.429) | |||||||||||||||||

| Number of overseas subsidiaries × Social scores | 0.930 *** | 1.612 *** | 0.387 ** | ||||||||||||||||

| (3.455) | (4.265) | (2.165) | |||||||||||||||||

| Number of overseas subsidiaries × Corporate governance scores | 1.111 *** | 2.061 *** | 0.532 ** | ||||||||||||||||

| (4.801) | (5.043) | (2.156) | |||||||||||||||||

| Research and development expense rate (%) | 2.905 ** | 4.816 ** | 6.276 *** | 3.042 ** | 4.914 ** | 5.867 *** | 2.934 ** | 5.269 ** | 7.210 *** | 2.804 *** | 5.103 *** | 7.158 *** | |||||||

| (2.200) | (2.107) | (5.037) | (2.191) | (2.022) | (4.376) | (2.438) | (2.574) | (6.463) | (2.732) | (2.816) | (6.540) | ||||||||

| Debt ratio (%) | −0.244 *** | −0.373 *** | −0.224 *** | −0.246 *** | −0.383 *** | −0.232 *** | −0.246 *** | −0.345 *** | −0.212 *** | −0.251 *** | −0.330 *** | −0.213 *** | |||||||

| (−4.203) | (−3.566) | (−3.766) | (−4.097) | (−3.537) | (−3.746) | (−4.371) | (−3.457) | (−3.774) | (−4.762) | (−3.540) | (−3.774) | ||||||||

| Ln (total assets) | 5.515 *** | 8.794 *** | −8.066 *** | 5.182 *** | 8.657 *** | −8.053 *** | 4.659 *** | 7.358 *** | −8.339 *** | 4.241 *** | 7.122 *** | −8.264 *** | |||||||

| (3.309) | (3.478) | (−6.612) | (3.023) | (3.163) | (−5.864) | (3.773) | (3.877) | (−8.688) | (4.688) | (4.458) | (−8.565) | ||||||||

| Firm fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||

| Year fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||

| Observations | 154 | 154 | 154 | 154 | 154 | 154 | 154 | 154 | 154 | 154 | 154 | 154 | |||||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.060 | 0.084 | 0.487 | 0.052 | 0.079 | 0.434 | 0.075 | 0.089 | 0.543 | 0.102 | 0.100 | 0.545 | |||||||

| F-statistics | 6.785 *** | 5.451 *** | 28.017 *** | 6.525 *** | 5.147 *** | 21.695 *** | 7.291 *** | 6.473 *** | 43.789 *** | 9.485 *** | 8.286 *** | 44.738 *** | |||||||

| (p-value) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, S.-H.; Hsu, H.-C.; Lin, S.-T. The Joint Effects of Firm’s Globalization and ESG Rating on Financial Performance: Evidence from Food Industry in Taiwan. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2580. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062580

Chen S-H, Hsu H-C, Lin S-T. The Joint Effects of Firm’s Globalization and ESG Rating on Financial Performance: Evidence from Food Industry in Taiwan. Sustainability. 2025; 17(6):2580. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062580

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Sheng-Hung, Hao-Cheng Hsu, and Shih-Ting Lin. 2025. "The Joint Effects of Firm’s Globalization and ESG Rating on Financial Performance: Evidence from Food Industry in Taiwan" Sustainability 17, no. 6: 2580. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062580

APA StyleChen, S.-H., Hsu, H.-C., & Lin, S.-T. (2025). The Joint Effects of Firm’s Globalization and ESG Rating on Financial Performance: Evidence from Food Industry in Taiwan. Sustainability, 17(6), 2580. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062580