A Comprehensive Multicriteria Analysis of Italian Regional Parks: Advancing Environmental Management and Benchmarking

Abstract

1. Introduction

Research Objectives and Questions

- To evaluate the performance of 150 regional parks across Northern, Central, and Southern Italy using a comprehensive set of indicators.

- To identify and analyze regional disparities in park distribution, management tools, and resource allocation.

- To provide actionable insights for policymakers and stakeholders to enhance the sustainability and effectiveness of park management.

- What are the primary factors influencing the performance of Italian regional parks, and how can they be measured using MCDA?

- How do regional differences in park management and resource allocation impact overall performance?

- Which parks serve as best-practice models, and what strategies can be adopted to improve underperforming parks?

2. Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Collection

- Official park websites: Information about park size, visitor statistics, conservation activities, and organizational structure was collected. Official park websites are primary sources of information directly managed by the park authorities, ensuring that the data are up-to-date and accurate. These websites typically provide details about the parks, including their size, visitor statistics, conservation activities, and organizational structure.

- Government reports: Legal frameworks such as the 1991 Protected Areas Law (L.394/1991) were consulted as the foundational legislation governing protected areas in Italy. This law establishes the general principles for the conservation and management of protected areas at the national level. However, in Italy, the management of regional parks is delegated to individual regions, which enact specific regulations for the establishment and protection of these areas. Regional laws vary from one region to another and are periodically updated to address local environmental and territorial needs. Government reports provide authoritative and standardized information on the regulatory environment governing regional parks, including both national and regional legislation. These reports are essential for understanding the legal and policy context in which the parks operate. While the 1991 law remains the cornerstone of protected area governance, it is complemented by more recent regional regulations that reflect evolving environmental priorities and local conditions.

- Direct communication: Direct telephone calls with park staff provided data on the number of personnel employed in the parks. In general, direct communication through emails and telephone interviews allows for the collection of specific, detailed, and sometimes unpublished data that may not be available on official websites or in government reports. This method is particularly useful for obtaining information on staffing levels, specific activities, and operational challenges.

- Literature review: A systematic literature review was conducted to supplement the collected data with historical and comparative information on park management. The review focused on academic papers and government documents published between 2000 and 2024, using keywords such as “regional parks”, “protected areas”, “environmental management”, “multicriteria analysis”, and “sustainability”. The primary purpose of the literature review was to provide a theoretical and historical foundation for this study, contextualizing the findings within the broader body of knowledge on park management and environmental conservation. Specifically, the literature review helped identify key indicators, methodologies, and best practices used in previous studies, which informed the selection of criteria and the development of the dataset and KPIs. The reviewed documents were also used to validate and cross-reference the data collected from official park websites, government reports, and phone calls with park staff.

2.2. Italian Regional Parks’ Dataset and KPIs

- Name of the Regional Park—the official name of the park as recognized by the regional or national authorities.

- Progressive Number—a numerical identifier assigned to each regional park in the dataset.

- Presence in the Official List of Protected Natural Areas (“Elenco Ufficiale delle Aree Naturali Protette”—EUAP)—indicates whether the park is officially recognized and included in Italy’s national registry of protected natural areas.

- Provinces—the administrative provinces in which the park is located. Some parks span multiple provinces.

- Land Area (hectares)—the total surface area of the park, measured in hectares (ha), which helps determine the size and scope of the protected area.

- Number of Inhabitants—the population residing within the park’s boundaries, including those living in towns and villages inside or bordering the park.

- 7.

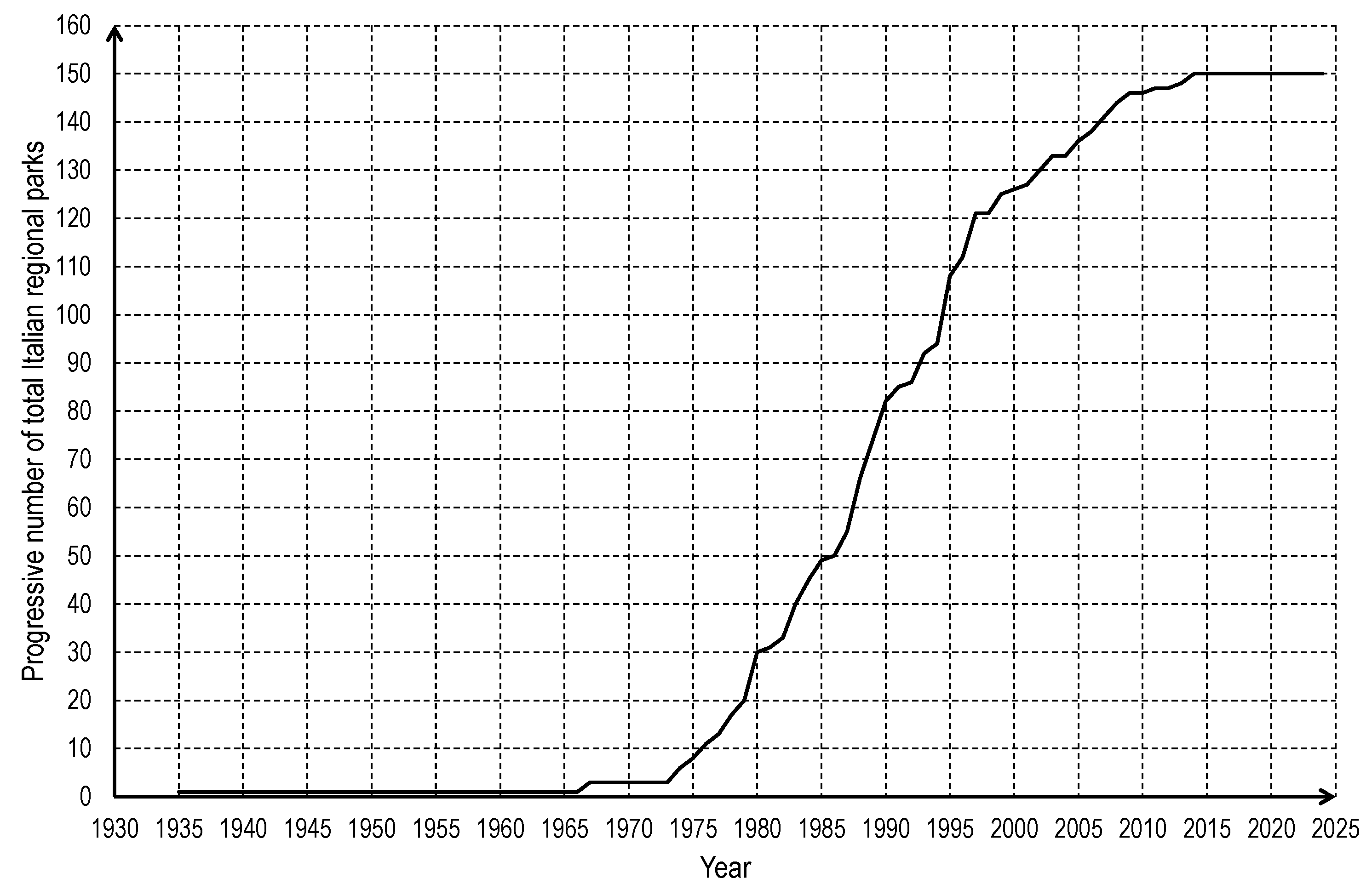

- Park Establishment Year—the year when the park was officially created, often through regional legislation.

- 8.

- Type of Park Regulation—the specific legal framework governing the park, which may include conservation restrictions, permitted activities, and management rules.

- 9.

- Regional Law Establishing the Park—the specific regional law or legislative act that led to the creation of the park, defining its boundaries, purpose, and governance.

- 10.

- Presence of Cartography—indicates whether the park has official maps available, either in print or digital format, showing trails, protected zones, and key locations.

- 11.

- Presence of a Master Plan—indicates whether the park has an official planning document that outlines conservation strategies, land use policies, and development guidelines.

- 12.

- Type of Master Plan—describes the nature of the master plan, such as whether it is primarily focused on conservation, tourism development, or sustainable land use.

- 13.

- Number of Municipalities—the total number of municipalities that are included, partially or fully, within the park’s boundaries.

- 14.

- Number of Employees—the number of people employed by the park authority, including administrative staff, rangers, and environmental experts.

- 15.

- Types of Activities Carried Out in the Park—the different activities permitted or promoted within the park, such as hiking, wildlife conservation, environmental education, scientific research, and tourism.

- 16.

- Number of Activities—the total count of officially recognized or managed activities available within the park.

- 17.

- Presence of Italian Alpine Club (CAI) Routes—specifies whether the park contains official hiking or trekking routes maintained by the Italian Alpine Club (Club Alpino Italiano—CAI), which are often well marked and used for mountain excursions.

- 18.

- Website—the official website of the park, where visitors and researchers can find information about regulations, attractions, and conservation efforts.

- 19.

- Presence of a Park App—specifies whether the park has a dedicated mobile application for visitors, which may provide maps, guides, event information, and regulations.

- Employees/Land Area (number/hectares)—measures the number of park employees per hectare of land. A lower value may indicate a vast park with relatively few staff, while a higher value suggests more intensive management and oversight per unit of land.

- Employees/Inhabitants (number/inhabitants)—represents the number of employees relative to the population living within the park. This helps assess whether staffing levels are adequate to serve local communities and manage conservation efforts in inhabited areas.

- Employees/Municipalities (number/municipality)—indicates the average number of employees per municipality within the park. A higher value may suggest better administrative and operational capacity at the local level.

- Activities/Employees—reflects the number of park activities managed per employee. A higher value may indicate high efficiency or workload, while a lower value could suggest either more specialized roles or fewer organized activities.

2.3. Multicriteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) Procedure

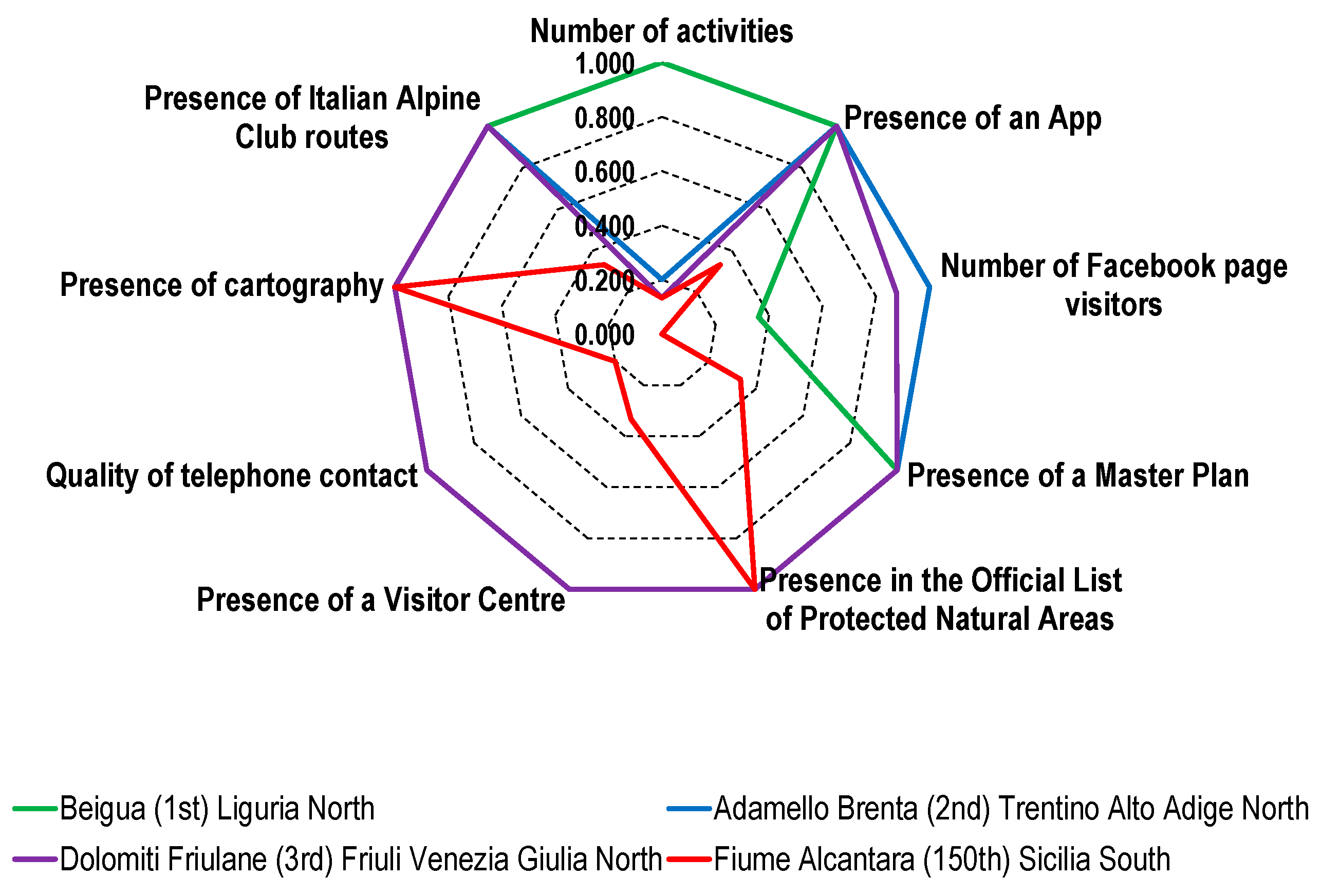

- C1: Number of Activities—a numeric value representing the number of activities offered by the park, to be maximized. The number of activities offered by a park (e.g., hiking, wildlife conservation, environmental education) is a direct indicator of its ability to engage visitors and promote sustainable tourism. Parks with a wide range of activities are likely to attract more visitors and contribute to local economies. This criterion reflects the park’s role in providing recreational and educational opportunities, which are key components of effective park management.

- C2: Presence of an App—a binary (No/Yes) criterion indicating the availability of a mobile application, transformed into a numeric value (Yes > No) to be maximized. The availability of a mobile application indicates the park’s commitment to leveraging digital tools for visitor engagement, information dissemination, and management efficiency. Apps can enhance the visitor experience by providing maps, event information, and real-time updates. In the digital age, the presence of an app is a marker of modern park management and reflects the park’s ability to adapt to technological advancements.

- C3: Number of Facebook Page Visitors—a numeric value reflecting the park’s online engagement, to be maximized. The number of Facebook page visitors serves as a proxy for the park’s online engagement and outreach efforts. A high number of visitors suggests effective use of social media to promote the park and interact with the public. Social media engagement is increasingly important for raising awareness, attracting visitors, and fostering community involvement in park activities.

- C4: Presence of a Master Plan—a binary (No/Yes) criterion indicating whether a long-term development plan exists, transformed into a numeric value (Yes > No) to be maximized. A master plan is a strategic document that outlines long-term goals, conservation strategies, and development guidelines for the park. Parks with a master plan are likely to have a clear vision and structured approach to management. The presence of a master plan indicates a park’s commitment to sustainable development and effective resource management, which are essential for long-term success.

- C5: Presence in the Official List of Protected Natural Areas—a binary (No/Yes) criterion, transformed into a numeric value (Yes > No) to be maximized. Inclusion in the official list of protected natural areas (Elenco Ufficiale delle Aree Naturali Protette, EUAP) signifies that the park is recognized and regulated by national authorities, ensuring compliance with conservation standards. This criterion reflects the park’s formal recognition and legal status, which are important for securing funding, enforcing regulations, and ensuring conservation efforts are aligned with national policies.

- C6: Presence of a Visitor Center—a binary (No/Yes) criterion, transformed into a numeric value (Yes > No) to be maximized. A visitor center serves as a hub for information, education, and visitor services. It enhances the visitor experience by providing resources such as maps, guided tours, and educational exhibits. The presence of a visitor center indicates a park’s investment in visitor services and its commitment to promoting environmental education and awareness.

- C7: Quality of Telephone Contact—a qualitative criterion with three possible values: “They do not answer” (poor service), “They answer but have no information” (limited service), and “They answer and have information” (good service), transformed into numeric values to be maximized. The quality of telephone contact reflects the park’s responsiveness and ability to provide information to visitors. High-quality communication indicates efficient management and good customer service. Effective communication is essential for visitor satisfaction and operational efficiency, making this criterion a key indicator of park management quality.

- C8: Presence of Cartography—a binary (No/Yes) criterion, transformed into a numeric value (Yes > No) to be maximized. Accurate and accessible maps are crucial for visitor navigation, safety, and enjoyment. Parks with high-quality cartography are better equipped to manage visitor flow and protect sensitive areas. Cartography is a fundamental tool for park management, ensuring that visitors can safely and effectively explore the park while minimizing environmental impact.

- C9: Presence of Italian Alpine Club Routes—a binary (No/Yes) criterion, transformed into a numeric value (Yes > No) to be maximized. The presence of routes maintained by the Italian Alpine Club (CAI) indicates the park’s suitability for hiking and outdoor activities. These routes are well marked and maintained, attracting outdoor enthusiasts. CAI routes enhance the park’s appeal to hikers and outdoor adventurers, contributing to its recreational value and visitor numbers.

- C1: Number of Activities (Category 16).

- C2: Presence of an App (Category 19).

- C4: Presence of a Master Plan (Category 11).

- C5: Presence in the Official List of Protected Natural Areas (Category 3).

- C8: Presence of Cartography (Category 10).

- C9: Presence of Italian Alpine Club Routes (Category 17).

- V1 = (1 − 1)/2 + (1/2) (1/2) = 0 + 0.5 0.5 = 0.25 is the numeric value corresponding to the qualitative value “No”;

- V2 = (2 − 1)/2 + (1/2) (1/2) = 0.5 + 0.5 0.5 = 0.75 is the numeric value corresponding to the qualitative value “Yes”.

- V1 = (1 − 1)/3 + (1/3) (1/2) = 0 + 1/6 = 0.1667 is the numeric value corresponding to the qualitative value “They do not answer”;

- V2 = (2 − 1)/3 + (1/3) (1/2) = 1/3 + 1/6 = 3/6 = 1/2 = 0.5 is the numeric value corresponding to the qualitative value “They answer but have no information”;

- V3 = (3 − 1)/3 + (1/3) (1/2) = 2/3 + 1/6 = 5/6 = 0.8333 is the numeric value corresponding to the qualitative value “They answer and have information”.

3. Results

3.1. Italian Regional Parks’ Dataset and KPIs

3.2. Multicriteria Decision Analysis (MCDA)

- High-Performing Parks (Top 25%): These parks, such as Beigua Regional Park and Adamello Brenta Natural Park, serve as best-practice models. Their success can be attributed to a combination of strong management tools, digital engagement, visitor facilities, and staff efficiency. These parks should focus on maintaining and refining their existing strategies while sharing best practices with other parks.

- Moderate-Performing Parks (Middle 50%): Parks in this range exhibit mixed strengths and weaknesses. Some may excel in digital engagement but lack structured conservation plans, while others may have strong staffing levels but low visitor engagement. For these parks, targeted action plans can be designed to address specific gaps, such as improving administrative capacity, increasing conservation activities, or enhancing visitor facilities.

- Low-Performing Parks (Bottom 25%): These parks show the largest percentage distance from the top and require strategic interventions. Their challenges could stem from insufficient staffing, lack of digital engagement, inadequate infrastructure, or minimal visitor activities. Recommendations for these parks should focus on capacity-building, securing additional funding, and adopting best practices from top-ranked parks.

4. Discussion

4.1. Italian Regional Parks’ Dataset and KPIs

4.2. Multicriteria Decision Analysis (MCDA)

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AHP | Analytic Hierarchy Process |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ANP | Analytic Network Process |

| CAI | Club Alpino Italiano (i.e., Italian Alpine Club) |

| COPRAS | Complex Proportional Assessment |

| EUAP | Elenco Ufficiale delle Aree Naturali Protette (i.e., Official List of Protected Natural Areas) |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| KPIs | Key Performance Indicators |

| MCDA | Multicriteria Decision Analysis |

| NPI | Normalized Priority Index |

| PIRFID | Priority IndexRadio-Frequency Identification |

| SWOT | Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats |

| TOPSIS | Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution |

| VIKOR | VlseKriterijumska Optimizacija I Kompromisno Resenje (i.e., multicriteria optimization and compromise solution) |

| WASPAS | Weighted Aggregated Sum Product Assessment |

| WLC | Weighted Linear Combination |

References

- Bassi, I.; Gori, E.; Iseppi, L. Assessing environmental awareness towards protection of the Alps: A case study. Land Use Policy 2019, 87, 104028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervelli, E.; Pindozzi, S.; Sacchi, M.; Capolupo, A.; Cialdea, D.; Rigillo, M.; Boccia, L. Supporting land use change assessment through Ecosystem Services and Wildlife Indexes. Land Use Policy 2017, 65, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comino, E.; Ferretti, V. Indicators-based spatial SWOT analysis: Supporting the strategic planning and management of complex territorial systems. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 60, 1104–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinauskas, M.; Bogdzevič, K.; Gomes, E.; Inácio, M.; Barcelo, D.; Zhao, W.; Pereira, P. Mapping and assessment of recreational cultural ecosystem services supply and demand in Vilnius (Lithuania). Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 855, 158590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmisano, G.O.; Govindan, K.; Loisi, R.V.; Dal Sasso, P.; Roma, R. Greenways for rural sustainable development: An integration between geographic information systems and group analytic hierarchy process. Land Use Policy 2016, 50, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmisano, G.O.; Loisi, R.V.; Ruggiero, G.; Rocchi, L.; Boggia, A.; Roma, R.; Dal Sasso, P. Using Analytic Network Process and Dominance-based Rough Set Approach for sustainable requalification of traditional farm buildings in Southern Italy. Land Use Policy 2016, 59, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, L.A.; van Beynen, P.E.; Parise, M. Interregional comparison of karst disturbance: West-central Florida and southeast Italy. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 1770–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marignani, M.; Bruschi, D.; Garcia, D.A.; Frondoni, R.; Carli, E.; Pinna, M.S.; Cumo, F.; Gugliermetti, F.; Saatkamp, A.; Doxa, A.; et al. Identification and prioritization of areas with high environmental risk in Mediterranean coastal areas: A flexible approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 590–591, 566–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccioli, F.; Fratini, R.; Boncinelli, F.; El Asmar, T.; El Asmar, J.P.; Casini, L. Spatial analysis of selected biodiversity features in protected areas: A case study in Tuscany region. Land Use Policy 2016, 57, 540–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, P.; Pecci, A.; Amadio, V.; Rossi, O.; Soliani, L. Coupling indicators of ecological value and ecological sensitivity with indicators of demographic pressure in the demarcation of new areas to be protected: The case of the Oltrepò Pavese and the Ligurian-Emilian Apennine area (Italy). Landsc. Urban Plan. 2008, 85, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenerelli, P.; Demšar, U.; Luque, S. Crowdsourcing indicators for cultural ecosystem services: A geographically weighted approach for mountain landscapes. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 64, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucca, A.; Sharifi, A.M.; Fabbri, A.G. Application of spatial multi-criteria analysis to site selection for a local park: A case study in the Bergamo Province, Italy. J. Environ. Manag. 2008, 88, 752–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goncalves, G.; Masson, E.; Wei, X. Sustainable Management of Energy Wood Chips Sector: Case Study of the Regional Park “Caps et Marais d’Opale”. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 221, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nin, M.; Soutullo, A.; Rodríguez-Gallego, L.; Di Minin, E. Ecosystem services-based land planning for environmental impact avoidance. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 17, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavadskas, E.K.; Bausys, R.; Mazonaviciute, I. Safety evaluation methodology of urban public parks by multi-criteria decision making. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 189, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocchi, L.; Cortina, C.; Paolotti, L.; Boggia, A. Recreation vs conservation in Natura 2000 sites: A spatial multicriteria approach analysis. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poli, G.; Cuntò, S.; Muccio, E.; Cerreta, M. A spatial decision support system for multi-dimensional sustainability assessment of river basin districts: The case study of Sarno river, Italy. Land Use Policy 2024, 141, 107123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanedo, S.; Juanes, J.A.; Medina, R.; Puente, A.; Fernandez, F.; Olabarrieta, M.; Pombo, C. Oil spill vulnerability assessment integrating physical, biological and socio-economical aspects: Application to the Cantabrian coast (Bay of Biscay, Spain). J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 91, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scorza, F.; Pilogallo, A.; Saganeiti, L.; Murgante, B.; Pontrandolfi, P. Comparing the territorial performances of renewable energy sources’ plants with an integrated ecosystem services loss assessment: A case study from the Basilicata region (Italy). Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 56, 102082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtois, P.; Martinez, C.; Thomas, A. Spatial priorities for invasive alien species control in protected areas. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 878, 162675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Montis, A. Impacts of the European Landscape Convention on national planning systems: A comparative investigation of six case studies. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 124, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramaniam, A.; Voulvoulis, N. The Appropriateness of Multicriteria Analysis in Environmental Decision-Making Problems. Environ. Technol. 2005, 26, 951–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Feo, G.; Galasso, M.; Landi, R.; Donnarumma, A.; De Gisi, S. A comparison of the efficacy of organic and mixed-organic polymers with polyaluminium chloride in chemically assisted primary sedimentation (CAPS). Environ. Technol. 2013, 34, 1297–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Feo, G.; Cerrato, F.; Siano, P.; Torretta, V. Definition of a multi-criteria, web-based approach to managing the illegal dumping of solid waste in Italian villages. Environ. Technol. 2014, 35, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rosa, D.; Takatori, C.; Shimizu, H.; Privitera, R. A planning framework to evaluate demands and preferences by different social groups for accessibility to urban greenspaces. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 36, 346–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizzari, M. Spatial modelling of potential landscape quality. Appl. Geogr. 2011, 31, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmotte, S.; Lopez-Ridaura, S.; Barbier, J.M.; Wery, J. Prospective and participatory integrated assessment of agricultural systems from farm to regional scales: Comparison of three modeling approaches. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 129, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Region | Key Statistics | Number of Parks per Region | Land Area (Hectares) | Number of Inhabitants | Number of Municipalities | Number of Employees | Number of Activities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italy | Min | 1 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Max | 25 | 91,140 | 2,843,962 | 60 | 103 | 15 | |

| Mean | 7.50 | 13,009.11 | 130,648.46 | 9.49 | 18.38 | 2.75 | |

| Standard deviation | 7.20 | 17,647.23 | 323,143.15 | 10.16 | 18.17 | 1.97 | |

| Coefficient of variation | 0.96 | 1.36 | 2.47 | 1.07 | 0.99 | 0.72 | |

| North | Min | 1 | 43 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Max | 25 | 91,140 | 1,809,555 | 60 | 63 | 15 | |

| Mean | 11.25 | 12,320.01 | 114,185.45 | 10.363 | 17.73 | 2.92 | |

| Standard deviation | 9.02 | 16,970.67 | 280,446.23 | 11.349 | 14.04 | 2.17 | |

| Coefficient of variation | 0.80 | 1.38 | 2.46 | 1.095 | 0.79 | 0.74 | |

| Center | Min | 3 | 7 | 1000 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Max | 16 | 29,990 | 2,843,962 | 20 | 75 | 9 | |

| Mean | 7.25 | 8127.57 | 168,874.04 | 5.89 | 25.40 | 3.14 | |

| Standard deviation | 6.13 | 8011.38 | 528,294.56 | 5.27 | 23.27 | 1.94 | |

| Coefficient of variation | 0.85 | 0.99 | 3.13 | 0.89 | 0.92 | 0.62 | |

| South | Min | 1 | 502 | 4616 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Max | 10 | 88,887 | 769,833 | 30 | 103 | 4 | |

| Mean | 3.88 | 19,441.07 | 144,449.03 | 10.19 | 13.79 | 1.90 | |

| Standard deviation | 3.48 | 23,633.42 | 170,611.12 | 9.30 | 25.62 | 0.87 | |

| Coefficient of variation | 0.90 | 1.22 | 1.18 | 0.91 | 1.86 | 0.46 |

| Region | Counting and Percentages | Presence in the Official List of Protected Natural Areas | Presence of a Master Plan | Presence of a Park App | Presence of Cartography | Presence of Italian Alpine Club Routes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italy | Number of ‘Yes’ | 130 | 80 | 82 | 150 | 118 |

| Number of ‘No’ | 20 | 70 | 68 | 0 | 31 | |

| Percentage of ‘Yes’ | 86.7% | 53.3% | 54.7% | 100.0% | 79.2% | |

| Percentage of ‘No’ | 13.3% | 46.7% | 45.3% | 0.0% | 20.8% | |

| North | Number of ‘Yes’ | 76 | 48 | 47 | 91 | 74 |

| Number of ‘No’ | 15 | 43 | 44 | 0 | 17 | |

| Percentage of ‘Yes’ | 83.5% | 52.7% | 51.6% | 100.0% | 81.3% | |

| Percentage of ‘No’ | 16.5% | 47.3% | 48.4% | 0.0% | 18.7% | |

| Center | Number of ‘Yes’ | 26 | 13 | 19 | 28 | 25 |

| Number of ‘No’ | 2 | 15 | 9 | 0 | 3 | |

| Percentage of ‘Yes’ | 92.9% | 46.4% | 67.9% | 100.0% | 89.3% | |

| Percentage of ‘No’ | 7.1% | 53.6% | 32.1% | 0.0% | 10.7% | |

| South | Number of ‘Yes’ | 28 | 19 | 16 | 31 | 19 |

| Number of ‘No’ | 3 | 12 | 15 | 0 | 11 | |

| Percentage of ‘Yes’ | 90.3% | 61.3% | 51.6% | 100.0% | 63.3% | |

| Percentage of ‘No’ | 9.7% | 38.7% | 48.4% | 0.0% | 36.7% |

| Region | Key Statistics | Employees/Land Area (Number/Hectares) | Employees/Inhabitants (Number/Inhabitants) | Employees/Municipalities (Number/Municipality) | Activities/Employees |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italy | Min | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Max | 0.723 | 0.750 | 52.000 | 4.000 | |

| Mean | 0.016 | 0.009 | 4.623 | 0.423 | |

| Standard deviation | 0.072 | 0.070 | 7.791 | 0.633 | |

| Coefficient of variation | 4.526 | 7.529 | 1.685 | 1.495 | |

| North | Min | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.019 |

| Max | 0.723 | 0.750 | 52.000 | 3.000 | |

| Mean | 0.017 | 0.013 | 4.307 | 0.352 | |

| Standard deviation | 0.084 | 0.085 | 7.023 | 0.476 | |

| Coefficient of variation | 4.908 | 6.677 | 1.630 | 1.354 | |

| Center | Min | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.533 | 0.028 |

| Max | 0.192 | 0.045 | 46.000 | 1.000 | |

| Mean | 0.025 | 0.004 | 7.630 | 0.284 | |

| Standard deviation | 0.051 | 0.011 | 10.292 | 0.294 | |

| Coefficient of variation | 2.019 | 2.602 | 1.349 | 1.035 | |

| South | Min | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Max | 0.009 | 0.001 | 33.000 | 4.000 | |

| Mean | 0.001 | 0.000 | 2.807 | 0.892 | |

| Standard deviation | 0.002 | 0.000 | 7.502 | 1.146 | |

| Coefficient of variation | 1.966 | 1.393 | 2.673 | 1.285 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Feo, G.; De Cicco, E.; Bocciero, L. A Comprehensive Multicriteria Analysis of Italian Regional Parks: Advancing Environmental Management and Benchmarking. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2560. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062560

De Feo G, De Cicco E, Bocciero L. A Comprehensive Multicriteria Analysis of Italian Regional Parks: Advancing Environmental Management and Benchmarking. Sustainability. 2025; 17(6):2560. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062560

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Feo, Giovanni, Eleonora De Cicco, and Luisa Bocciero. 2025. "A Comprehensive Multicriteria Analysis of Italian Regional Parks: Advancing Environmental Management and Benchmarking" Sustainability 17, no. 6: 2560. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062560

APA StyleDe Feo, G., De Cicco, E., & Bocciero, L. (2025). A Comprehensive Multicriteria Analysis of Italian Regional Parks: Advancing Environmental Management and Benchmarking. Sustainability, 17(6), 2560. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062560