1. Introduction

The Yangtze River Basin, a critical ecological barrier and aquatic gene pool in China, faces severe challenges due to declining fishery resources. Overfishing has triggered a sharp reduction in species diversity and ecosystem imbalance, posing a significant bottleneck to sustainable development in the basin [

1]. To implement the national “Ecological Civilization” strategy, the Chinese government launched a ten-year fishing moratorium in 2020, aiming to restore aquatic biodiversity and ecosystem functions through a comprehensive fishing ban [

2]. However, while generating notable ecological benefits, this policy has induced structural adjustments to fishermen’s livelihood capital [

3]. Statistics indicate that the ban affects 112,000 fishing boats and 231,000 fishermen [

4], necessitating livelihood transitions. As the core stakeholders, fishermen’s cognitive understanding of the policy and their behavioral responses directly determine its effectiveness [

5]. Challenges such as inadequate economic compensation, insufficient social security, and difficulties in occupational transitions highlight the urgency for systemic solutions [

6].

Fishermen’s ecological cognition is multi-dimensional [

7], encompassing sensitivity to environmental changes, interpretation of policy implications, and alignment with sustainable development values. Studies indicate that ecological cognition mediates the interaction between livelihood capital and policy compensation, profoundly shaping behavioral choices [

8], with high-cognition groups prioritizing long-term ecological benefits and low-cognition individuals focusing on short-term economic trade-offs. Although the current compensation framework includes income subsidies, vessel disposal, and social security [

9], mismatches between compensation standards and actual losses (e.g., compensation covering only 60–80% of fishing vessel costs in Poyang Lake [

10]) have trapped some fishermen in “policy dependency” and “survival anxiety.” Such structural contradictions underscore the need for optimized compensation mechanisms—differentiated ecological compensation systems are essential to balance ecological goals with social equity [

11].

Existing studies on the fishing moratorium span multiple dimensions. Domestic research focuses on ecological compensation standards [

12], occupational transition pathways [

4], and livelihood vulnerability assessments [

13], while international studies emphasize market-based governance tools such as fishery quotas [

14] and licensing systems [

15]. Notably, the fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) method has demonstrated unique advantages in analyzing complex policy effects [

16]. By identifying nonlinear relationships through configurational analysis, fsQCA has been widely applied in marine economic resilience [

17] and sustainable fishery transitions [

18]. For instance, fsQCA was employed to study compensation satisfaction among fishermen in the Chishui River Basin (Guizhou Province, China) in the upper Yangtze, yet existing research lacks granular exploration of the influencing factors beyond macro-level livelihood capital [

8].

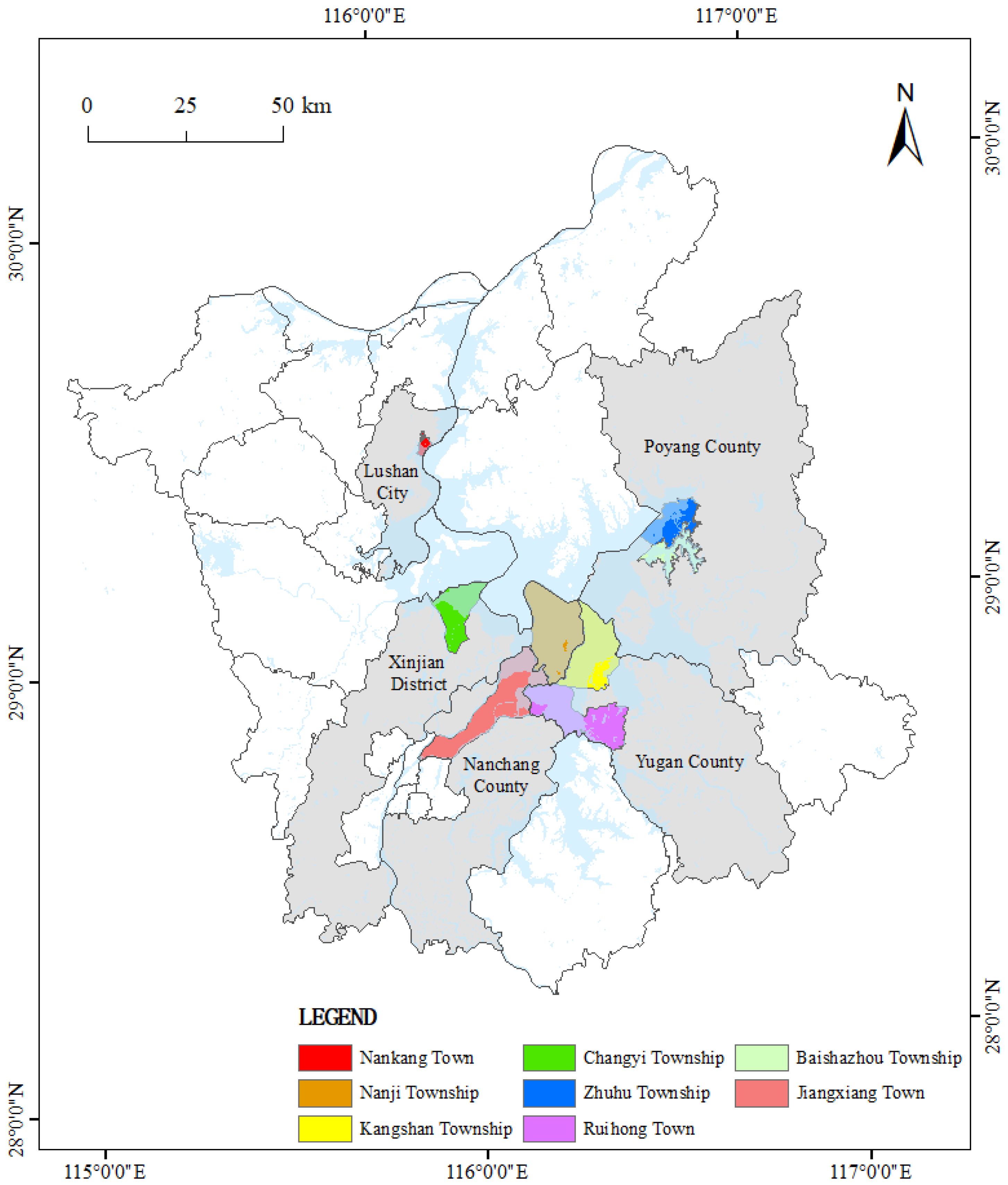

This study takes the Poyang Lake Basin as a typical case to construct an analytical framework of “Livelihood Capital-Ecological Cognition-Policy Response”, integrating questionnaire survey data with the fsQCA model to identify critical conditional configurations for fishermen’s transition, overcoming the limitations of traditional linear regression. The research primarily investigates the following: how differences in livelihood capital endowments affect fishermen’s ecological cognition and their response pathways to policies; how ecological cognition and compensation policies jointly influence behavioral responses. Based on model results, analyzing risk preferences, and decision-making logic during occupational transition processes, this study aims to promote a three-dimensional balance of “ecological restoration-economic compensation-social integration”, providing decision-making references for coordinating ecological protection and livelihood security in the Yangtze River Basin, while contributing Chinese experience to global ecological governance of major river basins.

This study uses a tripartite framework to analyze the Yangtze fishing ban. Firstly, performing a systematic review of the evolution of the Yangtze fishing ban policies and their impact mechanisms on Poyang Lake fishermen’s livelihoods. Secondly, utilizing survey data from 427 fishermen households obtained through stratified sampling, and employing descriptive statistics and fsQCA to analyze the correlation characteristics among livelihood capital, ecological cognition, and behavioral responses. Finally, proposing policy optimization recommendations through multi-case comparative analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of Fishermen in Poyang Lake

According to the survey conducted on the fishermen affected by the fishing ban in Poyang Lake (

Table 3), the gender distribution shows a majority of males, accounting for 65.4%. In terms of age, the age groups of 51–60 and over 60 represent significant proportions, at 35.4% and 33.9%, respectively. Regarding family size, most households consist of 4–6 members, making up 56.8% of the total. In the analysis of family labor force, households with 1–2 family members contributing to labor account for 45.5%, while those with 3–5 members contributing slightly exceed half, at 51.4%. Concerning education levels, 40.1% have received primary education, while 30.4% have never attended school.

3.2. Data Calibration

In the fsQCA method, calibration refers to the process of providing cases to assign set affiliation. This study uses the direct calibration method for variable calibration [

43]. Referring to previous studies [

16], the complete membership, crossover, and complete non-membership points for the condition and outcome variables are set at 95%, 50%, and 5%, respectively. By assigning the index value of the measurement index of the variable in an orderly manner, the comprehensive score of each variable is calculated in the form of the mean value, and the direct calibration method is adopted to use the quantile value of 95%, 50%, and 5% of the comprehensive score (

Table 4). In addition, due to the automatic deletion of condition values of 0.5 during fsQCA analysis [

44], this study replaced the calibrated condition value of 0.5 with 0.501.

3.3. Analysis of Necessary Conditions

Necessary condition analysis tests the necessity of a single condition in the outcome. When the consistency level exceeds 0.9, the condition can be preliminarily judged as a necessary condition for the outcome [

45]. When the consistency level is below 0.9, it can be determined that the condition is not a necessary precondition for the outcome and that further analysis of the preconditions’ configurations is required.

The fsQCA method was used to analyze the “Impact Mechanism of Livelihood Capital on Ecological Cognition” (

Table 5) and the “Impact Mechanism of Ecological Cognition and Policy Compensation on Behavioral Response” (

Table 6). The consistency levels for all conditions are below the necessary condition standard value of 0.9, indicating the absence of necessary antecedent conditions for ecological cognition and behavioral response. Further analysis of the preconditions’ configurations is needed.

3.4. Configural Analysis of Livelihood Capital on Ecological Cognition

Referring to the research of Zhang Ming et al. [

46], this study set the frequency threshold to 2, the consistency threshold to 0.8, and the PRI consistency threshold to 0.7. In the configurational analysis, the solution consistency is 0.89, indicating that 89% of fishermen with high ecological cognition align with the five identified configurational conditions. The coverage is 0.575, suggesting that these five conditions account for 57.5% of the cases exhibiting high ecological cognition. Both the consistency and coverage values exceed the critical threshold, supporting the validity of the analysis results. Configurations with identical core conditions (e.g., 2a and 2b, 3a and 3b) were grouped together, resulting in three distinct combinatory paths (

Table 7).

Configuration 1 demonstrates that natural capital, financial capital, and psychological capital are core conditions for fostering high ecological cognition, with human capital playing a peripheral role. Fishermen with abundant natural capital exhibit heightened sensitivity to ecological changes, making them more aware of environmental shifts. Financial capital provides economic security, allowing them to explore alternative livelihoods or participate in environmental conservation efforts. Psychological capital enhances their awareness and proactive engagement in ecological transformation. Although human capital is not a core factor in this configuration, its absence does not significantly hinder ecological cognition as the combined effects of other capital forms compensate for it. This suggests that fishermen with strong financial and psychological support, alongside rich natural resources, are more likely to recognize ecological changes and respond by adopting sustainable practices.

- 2.

Knowledge Adaptation and Support Path

Configurations 2a and 2b indicate that human capital, financial capital, and psychological capital are the primary drivers of high ecological cognition, with physical capital and social capital acting as peripheral conditions. In this pathway, human capital—including education and skill development—plays a crucial role in enabling fishermen to understand and implement ecological protection measures. Financial capital ensures the necessary resources for livelihood transformation and active participation in environmental initiatives. Psychological capital fosters resilience and adaptability, encouraging fishermen to embrace new livelihood strategies in response to ecological and policy changes. Physical capital (e.g., infrastructure and production tools) and social capital (e.g., network relationships) further support ecological cognition by facilitating access to critical information and resources. This pathway suggests that fishermen with strong educational backgrounds, financial security, and psychological resilience are better equipped to adapt to ecological policies through knowledge-driven adjustments.

- 3.

Comprehensive Collaborative Path

Configurations 3a and 3b highlight physical capital, financial capital, and social capital as core conditions for achieving high ecological cognition, with human capital, natural capital, and psychological capital serving as supplementary factors. In this pathway, physical capital provides essential infrastructure and tools for sustainable practices, while financial capital ensures economic stability during ecological transitions. Social capital facilitates information exchange and resource-sharing through community networks, reinforcing ecological awareness. Psychological capital strengthens fishermen’s positive attitudes and resilience, while human and natural capital further enhance their ability to respond effectively to environmental policies. This configuration underscores the synergy and complementarity of multiple capital forms, indicating that fishermen embedded in strong social networks, with access to financial and physical resources, are more likely to collaborate in ecological initiatives and policy adaptations.

The path of low ecological cognition is mainly influenced by the lack of human, natural, livelihood, and psychological capital. This absence hampers fishermen’s understanding of ecological protection and policy requirements, reduces their sensitivity to ecological changes, and limits their ability to adopt sustainable livelihoods. Additionally, insufficient physical and financial capital further hinders their ecological awareness. Overall, these deficiencies lead to a low awareness of ecological issues among fishermen, making it difficult for them to adapt their livelihoods and respond to policies.

3.5. Configural Analysis of Ecological Cognition and Compensation Policy on Behavioral Response

Through the configuration analysis of ecological cognition and compensation policies on behavioral responses, the solution consistency is 0.921, indicating that 92.1% of fishermen with high ecological cognition align with the four identified configurational conditions. The coverage is 0.579, suggesting that these four conditions account for 57.9% of the cases exhibiting high behavioral responses. Both the solution consistency and coverage exceed the critical threshold, confirming the validity of the analysis results. Configurations with identical core conditions (e.g., 1a and 1b) were grouped together, resulting in three distinct combinatory paths (

Table 8).

Configurations 1a and 1b demonstrate that high behavioral responses among displaced fishermen result from the combined influence of ecological cognition and compensation policies. The core conditions—behavioral attitude, perceived behavioral control, and compensation policy status—directly shape fishermen’s willingness to comply. Fishermen with a strong understanding of ecological protection tend to develop positive attitudes toward compensation policies, reinforcing their acceptance. Additionally, perceived behavioral control, or their confidence in adapting to policy changes, further strengthens their engagement. The effectiveness and transparency of compensation policies enhance participation willingness, while compensation satisfaction serves as motivation for active compliance. Compensation willingness, though supplementary, plays a role when fishermen perceive tangible benefits or when their interests are safeguarded. This path underscores that ecological cognition enhances the acceptance of compensation policies, which in turn drives positive behavioral responses. The findings suggest that improving fishermen’s ecological awareness while ensuring fair and transparent compensation policies can significantly increase policy compliance.

- 2.

Norm-Driven Policy-Cognition Path

Configuration 2 highlights that social norms and policy cognition jointly influence fishermen’s behavioral responses. The core conditions—subjective norms and compensation policy status—demonstrate that external social influences can compensate for weaker ecological cognition or personal compensation willingness. When strong social norms exist, fishermen are more likely to comply with policies due to group expectations, even if they have a weaker personal inclination toward compensation. The fairness and transparency of compensation policies play a crucial role in shaping fishermen’s responses. Policies perceived as just and effective foster greater willingness to participate, even among those with lower ecological awareness. While behavioral attitude and compensation satisfaction contribute to compliance, they play a secondary role in this path. These findings suggest that policy effectiveness and social norms can drive behavioral responses even when ecological cognition is less developed, emphasizing the importance of external influences in policy acceptance.

- 3.

Resonance Path of Social Support and Self-Efficacy

Configuration 3 reveals that the interaction between social support and individual self-efficacy significantly influences behavioral responses, reinforcing the joint impact of ecological cognition and compensation policies. The core conditions—subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, compensation policy status, and compensation satisfaction—demonstrate that both social and individual factors shape compliance. Fishermen develop a consensus to follow displacement policies under the influence of their community, while their confidence in adapting to post-ban livelihood changes strengthens their commitment. Recognizing compensation policies as reasonable and effective enhances their satisfaction, further motivating compliance. Although compensation willingness is a peripheral condition, it still plays a role in shaping responses. This path highlights that a combination of strong social support, high self-efficacy, and effective compensation policies can enhance fishermen’s acceptance and compliance with ecological protection policies. The findings suggest that boosting fishermen’s confidence in policy adaptation and fostering supportive social environments can enhance policy effectiveness, even when initial ecological cognition is weak.

Additionally, through the analysis of the pathways leading to low behavioral response, we find that low behavioral response primarily stems from two pathways. The first is that the lack of a positive attitude towards ecological protection, transparency in compensation policies, and compensation satisfaction leads to a decreased willingness among fishermen to participate in the policies. The second is that the absence of a positive attitude, confidence in the policies, and trust in the compensation policies further weakens fishermen’s willingness to accept compensation. These pathways indicate that enhancing fishermen’s awareness of ecological protection and their trust in compensation policies is crucial for improving policy responsiveness.

4. Discussion

The implementation of the “10-year fishing ban” policy in the Yangtze River Basin has achieved remarkable ecological restoration results. Five years into the ban, Poyang Lake has seen significant improvements in fish populations. Comparative analysis of fish body length structures before and after the ban shows effective mitigation of miniaturization phenomena in most assessed fish species, with increased proportions of larger individuals and sexually mature specimens in populations, indicating an optimized population structure [

47]. Ecopath model-based evaluation further reveals that the Poyang Lake ecosystem has expanded by 8.07%, with total biomass increasing by 35.7%. Energy and material conversion efficiency has risen from 10.7% to 11.3%, recovering to 1998 levels [

19]. These achievements demonstrate the policy’s positive effects in reversing ecosystem degradation.

However, ecological restoration must be balanced with safeguarding fishermen’s livelihoods, particularly in regions like Poyang Lake where economic structures are single-industry oriented and economically vulnerable. The success of the fishing ban depends not only on ecosystem recovery but also on fishermen’s adaptive capacity and policy acceptance. Therefore, policy optimization should integrate ecological protection with socioeconomic development to achieve sustainable ecological governance objectives.

- 2.

Challenges and Strategies for Livelihood Transition of Fishermen

Amid rapid socioeconomic development, young people in the Poyang Lake region have generally migrated to neighboring provincial capitals in search of opportunities, leaving the local fishing community dominated by middle-aged and elderly men with relatively low education levels. Long-term engagement in physically demanding labor has led to chronic health issues among some fishermen [

48], exacerbating livelihood transition challenges post-ban. Notably, 34.6% of affected fishermen are women, historically confined to auxiliary roles such as fish processing and sales [

49]. Their marginalization during the policy transition highlights the need for gender-sensitive policy frameworks.

Analysis of the relationship between livelihood capital and ecologic cognition reveals that the abundance of natural, financial, and psychological capital significantly enhances fishermen’s ecological consciousness. Financial capital plays a particularly critical role as when economic pressures are alleviated, fishermen exhibit markedly improved ecologic cognition and policy responsiveness. Psychological capital (including optimism and resilience) also proves vital during ecological transitions [

50], while social support bolsters self-efficacy and confidence in future livelihoods [

51]. These findings align with studies on farmers in the Hanjiang Plain [

52]. Additionally, human capital—primarily through education and skill development—shapes ecologic cognition, though its impact can sometimes be substituted by other forms of capital. For instance, research in the Dongting Lake region found no significant correlation between education levels and ecologic cognition [

53]. Material and social capital provide foundational support via infrastructure and community networks, as exemplified by sustainable livelihood strategies in Vietnam’s Hà Giang Province [

54].

Fishermen’s responses to ecological policies vary based on their livelihood capital endowments. Studies show that those with abundant natural and financial capital tend to adopt ecologically driven transition approaches, while those with higher human capital and financial stability prefer knowledge-based adaptation. Meanwhile, fishermen reliant on physical, financial, and social capital often enhance ecologic cognition and policy compliance through collaborative efforts. Thus, policymakers should tailor strategies to diverse capital configurations to optimize fishermen’s ecological adaptation pathways.

- 3.

Ecologic Cognition, Compensation Policies, and Behavioral Responses

Fishermen’s willingness to participate in ecological conservation is shaped by a combination of factors, including ecologic cognition, compensation policies, and social norms [

55]. Research indicates that behavioral attitudes, perceived behavioral control, and the status of compensation policies are key determinants of their policy responsiveness. For example, studies on farmers’ behaviors in returning farmland to forests [

56] ranked the influence of ecologic cognition as perceived behavioral control (0.354) first, then behavioral attitude (0.342), and then subjective norms (0.252)—this is a finding that aligns with this study’s perspective. Research on the improvement of rural living environments also shows that farmers’ recognition of policies and their skill levels significantly influence their behavioral responses, suggesting that both cognitive and policy-related factors drive farmers’ actions [

52]. Subjective norms, as a key element of ecological cognition, significantly affect fishermen’s willingness to transition away from fishing in Poyang Lake [

12], especially when compensation incentives are weak. Strong social expectations can compel fishermen to adhere to group norms, even if individual motivations are low [

57]. Consequently, increasing the penalties for violating fishing bans has proven effective in ensuring compliance.

To enhance ecological cognition and policy responsiveness, a dual strategy is recommended: strengthening intrinsic motivation through ecological education and ensuring fairness and transparency in compensation policies to reinforce extrinsic incentives. Additionally, efforts should focus on enhancing behavioral attitudes and perceived control when cognitive and policy frameworks are underdeveloped. Strengthening the support and promotion of compensation policies is also essential to boost participation and responsiveness among farmers and fishermen. This comprehensive approach can effectively promote responsive behaviors and foster ecological conservation.

- 4.

International Comparisons and Optimization Recommendations for Ecological Protection Policies

Global resource conservation policies—such as China’s Yangtze fishing ban, the EU’s Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) [

58], and the Amazon logging ban [

59]—share a core objective of balancing ecological recovery with economic development. However, their implementation universally faces three major challenges: firstly, the tension between long-term ecological benefits and urgent livelihood needs; secondly, conflicts between rigid policy frameworks and localized flexibility; and thirdly, gaps between technical regulatory capacity and the costs of noncompliance. For instance, China’s Yangtze fishing ban and Brazil’s deforestation ban adopted a “shock therapy” approach to swiftly curb ecological collapse, but insufficient compensation for displaced fishermen/farmers triggered social backlash. In contrast, the EU’s quota system and the U.S. Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) [

60] mitigated conflicts through gradual subsidies, yet inequitable distribution has undermined policy fairness [

50].

To better balance ecological restoration and fishermen’s livelihoods in the Yangtze Basin, policy optimization should focus on the following dimensions. Firstly, building on findings about livelihood capital disparities, a diversified compensation system should replace one-size-fits-all approaches. This would focus on differentiated compensation mechanisms. Transparent and equitable compensation should reflect fishermen’s actual income losses, prioritizing those in economically vulnerable regions. Secondly, occupational transition support should be provided through tailored vocational training and education programs which should address challenges faced by middle-aged, elderly, and female fishermen. Gender-sensitive frameworks must ensure women’s inclusion in transition plans, moving beyond historical marginalization in auxiliary roles. Thirdly, leveraging the proven link between ecologic cognition and policy responsiveness, governments should strengthen ecological education to foster intrinsic motivation and improve compliance through enhancing ecologic cognition. Fourthly, policy flexibility and community engagement should be used to strengthen community organizations, integrate traditional fishing culture into conservation efforts, and allow regulated harvesting of non-endangered fish in specific zones/times to support small-scale fishermen. Finally, they should embrace technological oversight and transparency by adopting blockchain technology to enhance regulatory transparency, curb rent-seeking, and optimize management using satellite data. These tools will improve policy fairness and efficacy.

Through these integrated measures, policymakers can better reconcile ecological recovery with livelihood security, advance sustainable development in the Yangtze Basin, and contribute Chinese insights to global river basin governance.

5. Conclusions

This study focuses on fishermen who have ceased fishing in the Poyang Lake Basin, constructing an analytical framework of “livelihood capital–ecological cognition–behavioral response” and employing the fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) method to systematically explore the formation pathways of fishermen’s ecological cognition and its impact on behavioral responses under the Yangtze River fishing ban policy. The main conclusions are as follows:

The multidimensional configuration of livelihood capital significantly influences ecological cognition. The heterogeneous configuration of fishermen’s livelihood capital shapes their ecological cognition through the “ecological transition-driven pathway”, the “knowledge adaptation support pathway”, and the “comprehensive synergy pathway”. The study confirms that financial capital and psychological capital are the core conditions for enhancing ecological cognition, while the substitution effect of human capital and the complementarity of physical capital provide theoretical support for differentiated policy design.

The interaction between ecological cognition and compensation policies drives behavioral responses. Fishermen’s behavioral responses to the fishing ban policy are influenced by both ecological cognition and compensation policies, specifically through the “ecological-driven policy recognition pathway”, the “norm-driven policy cognition pathway”, and the “social support–self-efficacy resonance pathway”. The study reveals that the fairness and transparency of compensation policies are key moderating variables for behavioral responses, while the mobilization capacity of social networks provides non-economic incentives for policy implementation.

This study has certain limitations that need to be addressed in future research. First, the research focuses on the Poyang Lake Basin, which, although representative, differs significantly from other sections of the Yangtze River Basin in terms of socioeconomic conditions and ecological characteristics. The generalizability of the findings requires further validation through cross-regional comparative analysis. Second, due to time and funding constraints, the sample size is relatively small (N = 257), which may affect the robustness of statistical results. Future research can improve validity by expanding the sample size and incorporating more heterogeneous groups (e.g., different ages, genders, and livelihood models). Additionally, while the fsQCA method effectively identifies causal patterns in condition combinations, it involves subjectivity in variable calibration and condition selection and struggles to capture linear relationships between variables. Future studies could integrate structural equation modeling (SEM) or mixed methods to deepen the analysis of underlying mechanisms.

By revealing the nonlinear mechanisms of livelihood capital, ecological cognition, and policy responses, this study overcomes the limitations of traditional linear analysis and provides theoretical support and practical pathways for the coordinated governance of ecological protection and livelihood security in the Yangtze River Basin. Furthermore, it contributes a more universally applicable “Chinese solution” to global large river basin ecological governance.