Abstract

Change management plays a key role in enhancing sustainable organizational performance in a dynamic global business environment. This study investigates the dimensions of change management (i.e., readiness of change, climate for change, and change processes) in boosting the sustainable performance of higher education institutions (HEIs) through knowledge management and transformational leaderships as mediators. This study employed an explanatory, quantitative, and cross-sectional approach for collecting data from the top management of private HEIs in Malaysia. Structural equation modeling using SmartPLS 4.0 is carried out for data analysis. We find that two dimensions of change management (i.e., climate for change and change processes) have a significantly positive impact on knowledge management, and only climate for change has a significantly positive relation with transformational leadership. The results highlighted that knowledge management mediate between climate for change and change processes and HEI sustainable performance. However, transformational leadership acts as a mediator between the climate for change and HEIs’ sustainable performance. No moderating effect of green teams was found between the mediators and HEI sustainable performance. The research findings have several implications for adopting the change management elements for the enhanced sustainable performance of HEIs and guiding the top management of HEIs, policymakers, and related governmental institutes.

1. Introduction

The United Nations General Assembly set seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015, to achieve them by 2030. The purpose of these seventeen goals is to “ensure a sustainable, peaceful, prosperous, and equitable life on Earth for all now and in the future” [1]. The report of the Open Working Group Proposal for Sustainable Development Goals highlights four “critical shifts” that distinguished the fifteen years of the Millennium Development Goals from the current period of the SDGs: (i) a drastically increased human impact on the physical Earth; (ii) rapid technological change; (iii) increasing inequality; and (iv) a growing diffusion and complexity of governance” [2]. UNESCO states that education is the “key instrument” in achieving the SDGs by increasing knowledge, skills, values, attitudes, critical thinking, competencies, systemic thinking, responsibility, and empowering future generations to make the necessary transformational change in our world [3,4,5].

Education sustainability is geographically unequal, and more efforts are needed to reduce disparities around the world [6,7,8]. The United Nations Decade of Education for Sustainable Development was declared in December 2002 to emphasize the importance of education in increasing global sustainability from 2005 to 2014 [9]. The overall goal was to “integrate the principles, values, and practices of sustainable development into all aspects of education and learning”, as well as to create “a more sustainable future in terms of environmental integrity, economic viability, and just society for present and future generations”. This initiative was critical in promoting global sustainability education at all levels. Several significant advances were made because of this strategy, including the convergence of education and sustainability agendas, the inclusion of sustainability issues in education systems, the engagement of many stakeholders, the expansion of legal commitments, the inclusion of sustainability issues in the entire learning environment, the promotion of critical thinking, participatory and problem-based learning, and the integration of education for sustainability.

Organizational change involves the process of altering an organization’s structure, strategy, operational techniques, technology, or organizational culture to achieve change inside the organization and the subsequent consequences of these changes [10]. Organizational change can occur in a continuous or discontinuous manner [11]. To adopt organizational change effectively, transformational leaders of an organization play a pivotal role as change agents. As a result, a leader’s efforts to bring about change will help a company succeed in a changing environment to achieve sustainable performance. The fact that the environment is constantly undergoing significant changes makes it imperative for firms to maintain a leader who can manage change successfully. The researchers have studied transformational leadership as an antecedent of organizational change [12,13,14,15], yet no prior study has been found that has investigated the impact of organizational change on transformational leadership. The present study builds the arguments on the institutional theory and resource-based view theory that situational factors (organizational change) force the management of an organization to adopt a leadership style (i.e., transformational) that facilitates the situational factor (organizational change).

Change is inevitable when an organization needs to survive for the sustainability of the organization in the future [16,17]. Organizations with transformational leadership will be more competitive in anticipating a changing environment. Transformational leadership provides support for the sustainable performance of the organization. Thus, managers can use the leadership approach of transformational leadership to encourage organizational improvement in sustainability performance. Several researchers have explored the significant effect of transformational leadership on sustainable performance [18,19,20,21,22]. Yet, no study has explored the relationship in the Malaysian HEI context. This study investigates the relationship between the variables under the lens of institutional theory and resource-based view theory.

The focus of research has been on sustainability in HEIs [23,24], education for sustainability in HEIs [25], and sustainable development goals in HEIs [26]. To the best of our knowledge, very few research studies have focused on the sustainable performance of HEIs as business entities. The current study will explore the impact of organizational change on the sustainable performance of HEIs in the private sector of Malaysia. The research has investigated the impact of sustainability and SDGs in Western and high-income countries. However, there has been less research in Asian countries, specifically in Malaysia to explore the relationship between organizational change and sustainable performance through the mediation of transformational leadership in HEIs.

Transformational leadership has been studied as a mediating variable between innovative work behavior and healthcare organizations’ performance [27], green intellectual capital and green supply chain integration [28], new ways of working and intrapreneurial behavior [29], and cultural intelligence and employee voice behavior [30]. To the best of our knowledge, no prior study has explored the mediating effect of transformational leadership between organizational change and sustainable performance in HEIs in Malaysia.

To understand the underlying mechanism of organizational change, knowledge management, transformational leadership, and sustainable performance, it has been recommended to further add the moderating effects of different variables. The current study employed green teams as moderators to understand fully the mechanism through which adopting organizational change can help achieve high levels of sustainable performance. In the Malaysian context, previous studies have investigated the sustainability practices at higher education institutions [31], achieving learning outcomes of emergency remote learning to sustain higher education during crises [32], the sustainability of a community of inquiry in online course satisfaction in virtual learning environments in higher education [33], and a crucial aspect of higher education’s individual and collective engagement with the SDGs [34]. Based on our research, there is no prior research exploring the impact of organizational change on sustainable performance through the mediation of knowledge management and transformational leadership and the moderation of green teams.

2. Literature Review

The present study has employed institutional theory to explain the relationship among variables in HEIs. Underpinning theories are intended to answer the “how” and “why” questions in research. The best framework for this research is the institutional theory, which explores the dynamic relationships between different elements of an organization and its environment. This approach can help to understand the complex interplay between organizational readiness for change, sustainability performance, green teams, and knowledge management in private HEIs. Additionally, the institutional theory can be used to examine the external influences on HEI sustainability and its response to those pressures. Finally, the resource-based view (RBV) can help to understand how organizational resources such as green teams and knowledge management contribute to the sustainable performance of HEIs.

2.1. Institutional Theory

The term “institutional theory” typically encompasses various perspectives that analyze the interplay between institutions and human behavior [35]. These perspectives posit that institutions are not only shaped by human actions such as behavior, perceptions, power dynamics, policy preferences, and decision-making processes, but they also exert influence on these very aspects of human behavior [36]. Institutionalism, as a theoretical perspective, emphasizes the imperative for organizations to effectively respond and adjust to their institutional surroundings. These surroundings include established norms, regulations, and shared understandings regarding acceptable and customary behaviors, which are typically resistant to immediate or effortless alteration [37,38]. The argument posits that organizations tend to unquestioningly accept rules and norms due to their perceived self-evident or inherent nature. Noncompliance with established norms and expectations can result in the emergence of conflict and the erosion of legitimacy. The institutional landscape of higher education (HE) is undergoing changes that are believed to impose growing limitations on HEIs [38]. In light of the aforementioned, it is becoming increasingly pertinent to examine the evolution of institutionalist theories and their application within the higher education domain.

HEIs are subject to pressures from governments, accreditation bodies, and global sustainability agendas (e.g., the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, or SDGs). These pressures compel HEIs to adopt practices that align with societal expectations, such as sustainability initiatives. Many HEIs implement sustainability programs not solely for operational efficiency but to align with external expectations and gain credibility. To adapt to these external changes, HEIs respond by increasing emphasis on environmental sustainability and social responsibility.

2.2. Resource-Based View Theory

Resources cover a wide range of assets, capabilities, traits, and knowledge that organizations may utilize to enhance their performance across many settings [39]. The resource-based view (RBV) theory posits that these resources are valuable as they enable organizations to effectively respond to market opportunities and threats. The authors also emphasize that a resource may not exhibit apparent worth in isolation but rather, via the interplay between assets and capabilities, the potential for the latter to reshape the former emerges [40]. The focus of the theory is on the internal resources and capabilities of organizations, arguing that these are the primary determinants of competitive advantage and performance. In the context of the present study, these intangible resources include knowledge management, transformational leadership, and green teams. The RBV theory has served as a theoretical foundation in several research studies conducted within higher education contexts. Researchers employ the resource-based view framework to examine how university resources are strategically organized to enhance their institutional reputation for effectively attracting both national and international students [41]. The existing literature in the field of higher education demonstrates a reliance on the resource-based view as a theoretical framework [42,43]. Most firms or organizations focus on only tangible aspects for performance measurements due to their ease in interpretation, while only a few firms have focused on intangible aspects as well despite their complexity of measurement and quantification. The RBV theory with the ability to consider both tangible and intangible aspects for performance measurement provides a suitable theoretical framework for elucidating the factors contributing to sustainable performance in higher education institutions.

The integration of institutional theory and RBV theory provides a comprehensive framework for understanding how HEIs navigate the dual imperatives of external legitimacy and internal efficiency. Institutional theory explains why HEIs adopt sustainability practices to comply with external norms and gain legitimacy, while RBV theory explains how these practices are effectively implemented through the mobilization of internal resources, knowledge management, transformational leadership, and green teams. HEIs must balance external pressures (institutional theory) with internal resource optimization (RBV). Institutional theory highlights the role of external pressures in driving organizational change, such as the adoption of sustainability practices. RBV theory, on the other hand, focuses on the internal mechanisms, such as transformational leadership, knowledge management, and team dynamics that enable HEIs to manage and sustain these changes effectively.

2.3. Change Management

Change is unavoidable in organizations [44], and employees are reluctant to support change in an organization since the future is unpredictable [45] and might have a negative influence on their talents, competences, worth, and value [46]. The concept of change management is operationalized in this study by following the work of [46] who have defined three-dimensional constructs as the circumstances under which change embarks (i.e., climate for change or internal context), the way a specific change is implemented (i.e., process), and the level of readiness at the individual level. Change climate refers to the “what” element of change, change process is best understood as the “how”, and readiness for change is “who” adapts these changes [44].

2.3.1. Readiness for Organizational Change

Organizational change is adopted through a process in which organizations are allowed to modify the strategic decisions or behaviors of employees or how the organization operates its business to accomplish the objectives [44,45]. Readiness for change is measured at the individual level, and common individual factors that might influence readiness are individuals’ general disposition toward change and their skills or abilities. Finally, readiness influences intentions and reactions. Intentions and reactions represent the attitudinal outcomes or actual behaviors that individuals may engage in to show their acceptance or rejection of the change initiative. Organizational-level change is successfully adopted through readiness for change, the climate for change, and the process of change [46]. Readiness for change is visible through the acceptance of change in the environment, structure, and behavior of employees in the organization to accept change at all levels. Although all components of change contribute to the efficiency and effectiveness of the implementation of change, readiness for change is one of the most critical components [47]. The top management team, board of directors, human resource management professionals and consultants for business development are the change agents responsible for preparing the organization for a change. Readiness for change is restrained through the gap between the expected effort of change agents and what their subordinates or other employees expect from them. Change resistance is significantly visible in case of any discrepancy between expected effort and expectation of employees and that would be an alarming situation for implementing change successfully in an organization. Therefore, it is concluded that the evaluation of an organization’s readiness for change may serve as an itinerary for formulating a strategy to execute organizational changes.

2.3.2. Climate for Change

However, organizational climate has been defined by several researchers, and there is a consensus on the definition of organizational climate. Yet, the definition of climate is not established fully. The climate for change was first defined by researchers as the perception of employees about the change that is expected, supported, and rewarded in an organization [48]. Establishing a positive attitude toward change is facilitated by organizational climates that have encouraging and adaptable structures. The research concluded that there was less resistance to change in the supportive and flexible organizational environment. Furthermore, the psychological climate (trust, participation, and support) helps to enhance the climate for change. The concept of “climate for change” is defined in this research in terms of general features of the environment that promote transformation. Employees’ perceptions of the internal conditions giving rise to change are what this term alludes to. The more ephemeral component of the change process pertains to the method by which a particular change project is handled. Among several factors contributing to readiness for change, the context and process of change in an organization are the most prominent ones [44].

2.3.3. Change Processes

For implementing effective change in an organization, it is necessary to have a deeper familiarity with the numerous processes of organizational change, including its levels and contexts as well as the decisions made before, during, and after the change [49]. There was an agreement among the researchers that the organizational change process is a difficult and challenging scenario for organizations that are managing change [50]. In the contemporary, global, and continuously evolving business environment, organizations are more involved in managing and embracing change. However, research shows that organizational change is a complex and multilevel process, yet there is little research focused on inquiring and examining the process of change in planning and implementing change in HEIs [51]. Several researchers have identified steps in the change process, including developing a clear change vision, integrating the vision at the level of teams and groups, embracing change at individual levels, maintaining the change implementation throughout the process of change, and putting change into practice [52]. A cohesive multilevel process of change is measured in various contexts and at different levels. There are three dimensions of the change process used in the measurement scale: (i) involvement in the change process, (ii) the ability of management to lead the change, and (iii) the attitude of top management toward the change project [46].

2.4. Knowledge Management

Knowledge is regarded as a performance-enhancing strategy for organizations. A sustainable organization, according to McCann and Holt [53], is a knowledge-based and knowledge-creating unit. Effectively managing knowledge is highly important for an organization to progress and flourish in the global competitive environment, and leadership plays a central role in creating knowledge, as well as its implementation and integration into the existing processes [54]. Knowledge, when viewed as a process, involves numerous actors and necessitates cross-sector collaboration. This method enables the collection, sharing, and creation of new knowledge, which will then be transformed into innovative, socially focused solutions.

Knowledge management refers to a set of systematic procedures designed to transform raw data into knowledge or valuable information that can be utilized to enhance the functioning of a company [55]. The aforementioned processes encompass the activities of creating, obtaining, retaining, disseminating, and utilizing knowledge [56,57]. Moreover, the acquisition and cultivation of knowledge by people inside an organization contribute to the creation of a competitive advantage [58,59]. Knowledge repositories, both physical and digital, play a key role in storing and sharing knowledge, while “expert networks” help direct specific queries to specialized experts within or outside the organization [60]. However, employees in need of assistance may hesitate to seek help due to fears of being perceived as inadequate. To address this, incentives can be introduced to encourage participation and readiness for change. The relationship between change management, knowledge management, and sustainable performance is deeply interconnected. Change management ensures that organizations can adapt to evolving circumstances by effectively implementing new processes, technologies, or strategies. Knowledge management supports this by providing the necessary information and insights to guide decision making and innovation during transitions. Together, they create a framework for continuous improvement and adaptability, which are critical for achieving sustainable performance. Sustainable performance relies on the ability to balance short-term goals with long-term viability, and this is only possible when organizations effectively manage change and leverage their knowledge resources. By integrating change management and knowledge management, organizations can enhance their resilience, foster innovation, and maintain competitive advantage, ultimately driving sustainable growth and success.

2.5. Transformational Leadership

Organizational change, which can alter the scope of management and the basis for departmentalization as well as the creation and changes in work schedules, can have an impact on virtually every aspect of an organization, including new technological developments and creating new work schedules [61]. Failure to implement the change explains why it is necessary to manage it successfully, and, if not, it might have serious implications. Employees, who are perhaps the least commonly consulted about change efforts, are intrinsically engaged and capable of assessing the efficacy of change processes [15]. Because of this, the researcher thinks that this study will help employees, especially those with minimal or no experience of change and change management, better grasp change and change management. Additionally, some individuals excel at observing and formulating their conclusions on what constitutes the industry’s best practices [62]. Employees will be better equipped to engage in change processes as a result of this in-depth study of both change and sustainability.

Transformational leadership (TL) has gained significant recognition in the field of management literature.

This concept pertains to leaders who prioritize clear communication regarding organizational objectives, serve as the driving force within the organization, actively engage in coaching, foster the development of new skills among their followers, and consistently pursue opportunities for organizational growth [63,64]. Transformational leaders place significant emphasis on people as valuable assets inside the organization, and they prioritize the role of emotions, values, and leadership that fosters positive and innovative behaviors [65]. Transformational leaders possess the ability to effectively engage and inspire personnel, thereby encouraging them to surpass anticipated performance levels and realize their maximum capabilities within an organizational context [66]. The concept of transformational leadership (TL) has gained significant scholarly attention and has emerged as one of the prominent leadership theories in academic discourse [67,68,69]. The examination of the impacts of technology leadership on organizational change capacity is of paramount importance in identifying an optimal approach to enhancing an organization’s ability to adapt and transform.

Transformational leadership (TL) has been recognized as a critical factor in facilitating successful organizational change [62,70]. Transformational leaders can achieve organizational change successfully by recognizing employees as a valuable resource, by fostering emotional and ethical connections with employees, and by motivating them towards higher values [62,70]. This approach allows leaders to effectively address the human aspects of change and overcome resistance to change among employees. Numerous prior studies have demonstrated that transformational leaders occupy a pivotal position in both the initiation and execution of change processes [12,14,71].

2.6. Green Team Resilience

The concept of a “team” pertains to a group of individuals possessing diverse expertise, working together towards shared aims and objectives, hence ensuring the cohesion of the group [72,73]. Rothenberg asserts that the majority of green projects necessitate a diverse range of individual competencies [74]. Hence, the establishment of a cross-functional team is deemed suitable for tackling intricate and interdisciplinary environmental challenges such as waste mitigation [75]. The collaborative approaches to address different facets of environmental management have gained traction among enterprises operating in contexts characterized by production dynamics, competitive pressures, and advanced technologies, necessitating increased cooperation among shop floor employees in addressing environmental concerns 78]. Environmental management teams, sometimes referred to as green teams, can be characterized as collectives of employees that are established, either through voluntary or involuntary means, with the purpose of addressing environmental issues or executing initiatives aimed at enhancing environmental efficacy [75,76]. According to Dangelico [77], green teams can be described as groups of employees who collaborate to design and execute targeted enhancements aimed at promoting environmental sustainability within their organization’s operations. The author emphasized that, although there are variations in the organizational frameworks of green teams, which manifest the divergences across companies, there exist certain shared characteristics among them: Green teams comprise employees who willingly dedicate several hours per month to participate in environmental activities. These employees come from various company functions and possess differing levels of seniority. Typically, green teams originate from a grassroots initiative and initially operate in a loosely organized manner. As they expand, they gain official recognition and support from management [78]. While green teams often prioritize local initiatives, they may also collaborate with other green teams operating in different locations within the organization.

There are two groups of green teams. The first group consists of functional green teams, composed of members from the same organizational unit, with a primary objective of enhancing environmental performance within that specific unit [72,79]. The second group comprises cross-functional green teams, consisting of members from different units, and their main focus is on making more comprehensive decisions related to corporate environmental management. Furthermore, Strachan’s [78] research posits the existence of three distinct categories of green teams. Firstly, there are top administrators’ green teams, which hold the responsibility of formulating an organization’s environmental policy. Secondly, action-oriented green teams are tasked with analyzing opportunities for enhancing environmental performance. They propose and oversee pollution prevention programs that align with the organization’s environmental policy. Lastly, there are teams dedicated to improving the environmental impact of specific productive processes. These teams analyze said processes and put forth recommendations for more stringent environmental enhancements.

2.7. Sustainability Performance of HEIs

The concept of sustainability entails the delicate equilibrium between the present generation’s requirements and those of future generations, with the ultimate goal of enabling the latter to fulfill their own demands in the future. This term incorporates both present and future perspectives. Sustainability encompasses the notion of the “Triple Bottom Line”, which posits the need for a suitable congruence among three dimensions: Environmental Performance (EP), Social Performance (SP), and Financial Performance (FP), in order to attain organizational sustainability [80]. From a business perspective, Sustainability Performance (SP) refers to the capacity of an organization to fulfill the current requirements of its business operations and stakeholders while simultaneously preserving and improving the natural and human resources necessary for future sustainability [81]. A sustainable organization refers to an entity that engages in sustainable development by effectively addressing three key elements simultaneously: social equality, financial efficiency, and environmental performance within its operational processes. The focus on sustainability performance has emerged as a significant priority for numerous firms on a global scale. This emphasis offers prospects for sustained growth and advancement, financial sustainability, and competitive benefits [82].

Development that “meets the current generation’s requirements without jeopardizing future generations’ ability to fulfil their own” has been classified as sustainable by the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED—World Commission on Environment and Development 1987). There are a number of different sorts of organizations that play a role in establishing a sustainable future, including higher education institutions (HEIs) [83]. Educators and researchers may make a positive impact on the future of sustainable development by sharing their expertise with others and collaborating with the private sector [82,84]. It is through their efforts that the next generation of policymakers, leaders, and decision-makers in the field of sustainable development will be formed. By integrating sustainable development goals into their curriculum, universities have a multiplier effect on the dissemination of these goals [85]. However, several studies have indicated that firms have had little success in implementing sustainability programs because of the attitudes and behaviors of their executives [86]. A “structural adjustment” is needed to “guarantee educational institutions make sustainability a fundamental priority in their mission statement” [87]. Organizational leadership and innovation are two areas that must be transformed if we aim to achieve long-term sustainability [83].

Sustainability is a difficult topic to grasp because it combines three high-level considerations: people, the planet, and profit. As sustainability models, higher education institutions must have a strong organizational culture in place. To do this, major adjustments in the direction of establishing new values and behaviors are required [88]. Adopting sustainability in HEIs is only explored to some level in academic institutions, and there are significant variances between educational fields [89].

Numerous problems and impediments at various levels jeopardize higher education’s successful contribution to the creation of a sustainable future. In general, without significant and profound change in the academic world, universities risk losing their critical role in research and knowledge. The SDGs are pressuring higher education institutions to adapt to a world in crisis. There is a need for a shift in attitude and ethical standards to address the most pressing issues of our time. Researchers have explored how the employees work effectively during organizational changes without ignoring their responsibilities in corporate, delivering excellent educational services to their customers. Researchers should also look into change agents and management as mechanisms to understand the drivers for sustainability implementation in the organization.

3. Hypothesis Development

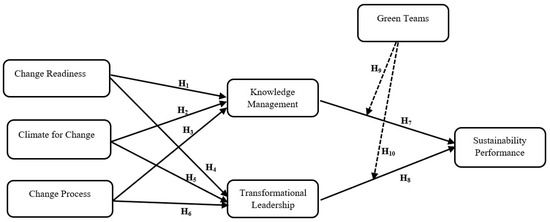

The conceptual framework used in the present study is provided in Figure 1, showing the relationship between latent constructs. The following hypotheses have been developed to examine the conceptual framework.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

3.1. Change Management and Knowledge Management

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought about profound and far-reaching transformations across industries worldwide, fundamentally altering the way businesses operate and adapt to new realities [90,91]. Higher education institutions (HEIs), as integral components of the global education sector, have not been immune to these sweeping changes. The education industry, in particular, has experienced significant shifts in its organizational structures and processes, driven by the need to respond to rapidly evolving market demands and societal expectations [91]. These changes have been further compounded by the critical role of technological advancements, which have not only reshaped the tools and methods of delivering education but have also influenced the way knowledge is disseminated and managed within organizations [92]. As the business world continues to evolve at an unprecedented pace, the urgency for organizations to embrace and implement change has grown exponentially, becoming a central focus for leaders and decision-makers [93].

While past research has consistently highlighted the importance of organizational change as a strategic imperative, the current landscape has introduced new complexities and heightened pressures. The dynamic interplay of technological, economic, and social factors has created an environment where change is not only inevitable but also more challenging to navigate than ever before [94,95]. For top management, the task of managing and implementing change has become increasingly perplexing, requiring a delicate balance of strategic vision, operational agility, and stakeholder engagement. Despite the growing recognition of the need for change, studies reveal a stark reality: approximately 75% of organizational change initiatives fail to achieve their intended outcomes. This high rate of failure is often attributed to inadequate management of the change process, insufficient readiness for change among employees, and a lack of a supportive climate for change within the organization [96].

Given these challenges, it is evident that the ability to effectively manage change is a critical determinant of organizational success in the current era. The interplay between readiness for change, the organizational climate, and the strategies employed to implement change has emerged as a key area of focus for researchers and practitioners alike. Building on these insights, this study proposes the development of a hypothesis that seeks to explore the factors influencing the success of organizational change initiatives within the context of higher education institutions. This hypothesis aims to provide a deeper understanding of how HEIs can navigate the complexities of change management in an increasingly volatile and uncertain environment, ultimately contributing to more effective and sustainable transformation efforts.

H1:

Readiness for change has a positive impact on knowledge management.

H2:

Climate for change has a positive impact on knowledge management.

H3:

Change process has a positive impact on knowledge management.

3.2. Change Management and Transformational Leadership

According to the research conducted by [97], the integration of transformational leadership behaviors is beneficial for managers and directors in the effective and successful implementation of organizational change. According to Cao and Le [15], it has been argued that transformational leadership (TL) may be the most relevant leadership style for efficiently overseeing the process of change. The empirical results confirmed that TL had both positive and substantial effects on organizational change capability (OCC). According to Busari et al. [14], it is emphasized that transformational leaders play a crucial role in driving change by actively stimulating and modifying the motivations, beliefs, and attitudes of employees, elevating them from a lower state to a higher level of arousal. In addition, businesses undergoing a higher frequency of change under transformational leadership can be more successful [97].

Transformational leadership (TL) has been recognized as a critical factor in facilitating successful organizational change [15,71]. Transformational leaders can achieve organizational change successfully by recognizing employees as valuable resources, fostering emotional and ethical connections with employees and motivating them towards higher values [15,69]. This approach allows leaders to effectively address the human aspects of change and overcome resistance to change among employees. Numerous prior studies have demonstrated that transformational leaders occupy a pivotal position in both the initiation and execution of change processes [12,14,69]. The results of this study indicated that businesses that undergo more frequent changes are likely to achieve greater success when they are led by transformational leaders.

H4:

Readiness for change has a positive impact on transformational leadership.

H5:

Climate for change has a positive impact on transformational leadership.

H6:

Change process has a positive impact on transformational leadership.

3.3. Knowledge Management and Sustainability Performance of HEIs

Knowledge management serves as a critical source of competitive advantage for organizations, enabling them to identify, organize, and utilize their knowledge resources effectively to achieve long-term strategic goals [58,98]. In recent years, there has been a growing emphasis on integrating sustainability into organizational practices, with knowledge creation and acquisition playing a pivotal role in this transformation. Organizations are increasingly recognizing that sustainability is not just an ethical imperative but also a strategic one, as it contributes to long-term resilience and success. Top management teams are now prioritizing sustainability performance as a key component of their agendas, leveraging knowledge management to drive innovation, efficiency, and competitive advantage [99].

In the context of higher education institutions (HEIs) in Israel, for instance, effective change management has been facilitated through collaborative mechanisms where leaders from various institutions actively participate in disseminating knowledge within their communities [92]. This approach not only strengthens institutional capabilities but also fosters a culture of shared learning and adaptation. Knowledge management, when implemented effectively, optimizes organizational performance by streamlining processes, enhancing decision making, and fostering innovation [99].

Several research studies have explored the relationship between knowledge management and organizational performance, highlighting its significant impact. For example, one study investigated the role of knowledge management enablers—such as knowledge creation and organizational creativity—and their influence on organizational performance, demonstrating a strong positive correlation [100]. Similarly, another study found that knowledge management significantly enhances innovation performance, particularly in dynamic industries like hospitality [101]. Additionally, research focusing on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in Indonesia revealed that knowledge management practices have a substantial effect on improving organizational performance, underscoring its relevance across diverse sectors and scales [102].

Given the compelling evidence and arguments presented, it is clear that knowledge management is a vital driver of organizational success, sustainability, and innovation. Building on these insights, the following hypothesis is proposed to further explore the relationship between knowledge management, change management, and sustainable performance in organizational contexts. This hypothesis aims to provide a deeper understanding of how organizations can harness knowledge management to navigate change effectively and achieve long-term sustainability.

H7:

Knowledge management has a positive impact on the sustainability performance of HEIs.

H7a:

Knowledge management mediates the relationship between change readiness and sustainability performance of HEIs.

H7b:

Knowledge management mediates the relationship between climate for change and the sustainability performance of HEIs.

H7c:

Knowledge management mediates the relationship between change process and the sustainability performance of HEIs.

3.4. Transformational Leadership and Sustainability Performance of HEIs

Nevertheless, the process of establishing and maintaining operations can present challenges and necessitates the agreement and collaborative endeavor of all parties involved to achieve success, as found in the study of [83]. The researcher of the study further argued that the leaders of an organization hold a significant position for its stakeholders as they bear the responsibility of formulating and executing suitable strategies, procuring and utilizing appropriate resources and inspiring their employees to collaborate in the pursuit of sustainable goals, desired objectives, and collective outcomes. To enhance sustainability performance and gain a competitive advantage, the leader of a firm must exhibit sustainable ideas that effectively stimulate employees’ behavioral intentions towards environmental conservation [102,103]. To augment the organizational capacity and ability to achieve environmental, financial, and social performance, the implementation of a leadership style possessing appropriate features can facilitate learning and build values, norms, and voluntary environmental behavior [104,105].

The leadership component is an essential prerequisite for effectively steering and overseeing the organization’s operations for achieving sustainable performance. Effective leadership necessitates a clear vision and the ability to inspire personnel to consistently and responsibly demonstrate their achievements [104]. Therefore, the implementation of organizational strategic planning necessitates a leader who is dedicated to undertaking these specified actions. A leader in an organization is responsible for consistently elevating the employees’ awareness and motivating them to improve their performance to attain the company’s goals [82]. According to Waldman and Siegel, it is argued that the intellectual stimulation efficiency of TLs is suitable for sustainable organizational strategy. The achievement of sustained employee and organizational performance necessitates the implementation of employee training and development [105]. Transformational leadership with its effective and meaningful communication between a transformation leader and its followers and its potential for achieving sustainability performance of an organization is considered a suitable tool [106].

While it is widely acknowledged that leadership styles significantly influence all elements of organizational performance, there is a lack of empirical research examining the specific impact of leadership styles on sustainable performance. Within the limited body of research available, the majority of studies have concentrated on responsible leadership [107], sustainable leadership [83], ethical transformational leadership [108], vision-based leadership [109], and their influence on the organizational sustainable performance. However, a few studies regarding the role of transformational leadership on the enhancement of sustainable performance are available in the literature. To fill the research gap, we have developed the following hypotheses:

H8:

Transformational leadership has a positive impact on the sustainability performance of HEIs.

H8a:

Transformational leadership mediates the relationship between change readiness and sustainability performance of HEIs.

H8b:

Transformational leadership mediates the relationship between climate for change and the sustainability performance of HEIs.

H8c:

Transformational leadership mediates the relationship between change process and the sustainability performance of HEIs.

3.5. Green Team Resilience as Moderator

The concept of resilience in an organization or management refers to the ability of an organization or a team in an organization to effectively cope with adverse circumstances faced as a result of significant turmoil or due to the aggregation of various negligible inferences [73,88]. The concept of resilience in an organization or management refers to the ability of an organization or a team in an organization to effectively cope with adverse circumstances faced as a result of significant turmoil or due to the aggregation of various negligible inferences [56,88]. Transformational leaders endorse green vision and green norms to engage their followers through resource allocation. Transformational leaders inspire their team to mitigate challenges and promote “task-engaging” behavior [73]. Although well-established and integrated relationships are crucial for team resilience, green team resilience has been a neglected area of research. Researchers consider green transformational leaders as a “social support system” because of their ability to understand and promptly respond in complex situations [110]. Relationships are crucial for a team’s resilience to environmental challenges. Transformational leadership fosters relationships and high resilience among team members [73]. Measures of intellectual stimulation, personality, influence, and empathy positively correlate with team resilience.

Green teams’ spectrum is broadened with time to build abilities and resources. There is a positive relationship between the culture of learning and an effective communication and knowledge-sharing structure [111]. The research also revealed a positive moderating effect of green or environmental teams between the relationship of board attributes and performance. Team support for innovation has a positive moderating effect on the relationship between participative safety and team-level adaptivity [112]. Thus, it is proposed here that green team resilience has a positive moderating effect on transformational leadership, knowledge management, and sustainability performance in the context of HEIs:

H9:

Green team resilience positively moderate the relationship between knowledge management and sustainability performance.

H10:

Green team resilience positively moderate the relationship between transformational leadership and sustainability performance.

4. Methodology

The present study’s philosophical and ontological basis is the realism view, which follows a deductive approach to understand the causal relationship among constructs of this positivist and quantitative study. Deductive reasoning refers to the approach to developing a hypothesis [113] and study framework on the existing and established literature. The quantitative data were collected using a survey questionnaire adapted from past researchers. A questionnaire was developed with three sections. The first section explains the introduction of this research, confidentiality and anonymity of data, and assurance for using data only for research purposes, followed by marking a tick for the I agree option to record the consent of respondents. In the second section, demographic variables including age, gender, education, and tenure were included. In the last section, items from research instruments of each construct are presented on a 5-point Likert scale. The population of this study is top management in 437 private HEIs of Malaysia, and the sample was drawn using simple random sampling. The list of private HEIs located in Klang Valley was retrieved from the MOHE website, and the Vice Chancellor, Director, and Head of Academia were approached to fill face-to-face paper-based surveys. In colleges or universities where top management was not available through appointment, surveys were submitted to the research department. A follow-up message on WhatsApp and email was sent, and, after confirmation, researchers visited the college or university again to collect questionnaires. The data collection started in June 2024 and ended in December 2024. A total of 300 surveys were distributed, and 168 surveys were received, which shows a 49% response rate. After handling missing data and outliers, 152 valid responses were left for statistical analysis. Similar studies used a sample size of 64 leaders in HEIs in Pakistan [114]. The total number of private HEIs in Malaysia is 437, and the population of this study is top management, including Vice-Chancellor, Director, and Head of Academia, which means only 2–3 respondents were chosen from each institute. This implies that the total population of this study is 437 × 3 = 1311. Therefore, a sample size of 152 was considered good enough. According to the G*power test, the minimum required sample size is 100, and a larger sample size was taken in this study to generalize the results.

4.1. Measurement Tools

The instruments used in this study were adapted from earlier researchers. To measure climate for change, change process, and readiness for change, scale was adapted from Bouckenooghe et al. [46], and the sample item includes “I want to devote myself to the process of change”. Knowledge management was measured by adopting items from the scale developed by the authors of [91] with a sample item as “we look for opportunities to experiment and learn more about products and services”. The instrument for transformational leadership was adopted from a study conducted by Chen and Chang [115] with a sample item “I inspire subordinates with environmental plan”. The questionnaire to measure green teams was adopted with a sample item as follows: “The team perceives sustainable activities experience; even though it is stressful, they still find a positive angle and move forward” [73]. Sustainable performance was measured with fifteen items adapted from the research work of [104] with a sample item “In my university, initiatives are taken to implement long-term environmental policies”.

4.2. Reliability of Scales

There is no issue of common method bias found in the data as the value for Harman’s single-factor test was 42.65%, which lies under the threshold value of 50% (see Table 1). To confirm this, variance inflation factors (VIFs) were calculated, and results show that all values are below 3.30, which is a threshold value for VIFs [116].

Table 1.

Full collinearity test.

4.3. Reliability and Validity

Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliabilities are parameters used in this study to confirm the reliability of the constructs in Table 2. The threshold value for composite reliability (ρc) lies in the threshold value range, i.e., 0.70–0.90 for all [117]. The composite reliability (ρa) values must be within the range as recommended by the former researcher. Cronbach’s alpha is used as the lower boundary, and composite reliability (ρc) is used as the upper boundary. The values in Table 2 show that there is a high level of internal consistency reliability within the constructs.

Table 2.

Reliability and validity.

Loadings, cross-loadings, and Fornell and Lacker’s criterion is presented in Table 3. Heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT ratio) falls in the recommended threshold value, which is less than 0.90 [118]. There is an issue of discriminant validity if any value in the diagonal is greater than 0.90 see Table 4. HTMT matrix confirms that all values are less than the threshold value, which shows that the discriminant validity is at a satisfactory level.

Table 3.

Loading, cross-loading and Fornell–Larcker criterion.

Table 4.

HTMT ratio.

5. Data Analysis and Results

Smart PLS 4.1.0.3 was used for analysis of the data. The choice of “Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM)” over alternative approaches like covariance-based SEM (CB-SEM) or regression analysis is justified by several methodological and contextual factors. PLS-SEM is particularly suited for the complex model of this study, which includes multiple constructs (e.g., climate for change, readiness for change, change processes, knowledge management, transformational leadership, and green teams) and examines the mediation and moderation effect. Unlike CB-SEM, PLS-SEM does not require large sample sizes or assume multivariate normality, making it ideal for the small sample size of 152 responses and potential non-normal data distribution. Additionally, PLS-SEM is well suited for exploratory research, allowing the testing of emergent theories and the identification of key drivers of sustainability performance in HEIs, an area with limited prior research. Its ability to handle both formative and reflective constructs ensures the accurate modeling of conceptually distinct variables, such as green teams. Furthermore, PLS-SEM’s focus on maximizing explained variance (R²) and its integration with “bootstrapping techniques” (5000 subsamples) provide robust estimates of path coefficients and hypothesis testing. In contrast, regression analysis is limited in handling multiple dependent variables and complex mediation/moderation relationships, while CB-SEM is less flexible with formative constructs and requires larger samples. Thus, PLS-SEM’s adaptability, robustness, and focus on prediction and explanation make it the preferred method for this study.

5.1. Demographic Variables

The descriptive analysis was performed to show the frequencies of demographic variables. Respondents were asked to mention their age within a specific group, education level, tenure, and gender as listed in Table 5. Out of 152 respondents, 59% were aged between 31 and 40 years, 22% were between 41 and 50 years, 13% were between 51 and 60 years, and only 5% were above 60 years. Most of the respondents have a Master’s/equivalent degree as 71% of records were found for this category. Only 2% of the respondents have reported their education level as MS/Mphill, 21% have a qualification of PhD, and 8% have graduated DBA. The responses show that the tenure of respondents is 1–3 years, 4–6 years, and above 10 years is 27, 21, and 22, respectively. The data are divided in half in terms of gender as 46% of respondents were females, and 54% were males.

Table 5.

Demographic variables.

5.2. Hypothesis Testing

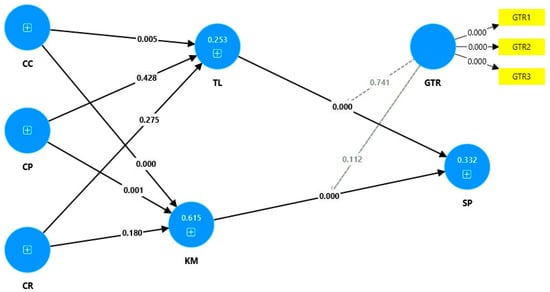

The results of structural equation modeling shown in Figure 2 demonstrates that climate for change and change process have a positive significant direct effect on knowledge management with t-values of 3.870 and 3.236, respectively, and p-values of 0.000 and 0.001, respectively (see Table 6). There is no positive direct effect of readiness for change and knowledge management when the p-value is greater than 0.05 (t-value = 1.340 and p-value = 0.180). The relationship between climate for change and transformational leadership is positively significant with a t-value of 2.823 and a p-value = 0.005. However, change process and readiness for change have no significant effect on transformational leadership with p-values greater than 0.05. A t-value of 2.342 and p-value 0.019 show a positive significant effect between green teams and the sustainable performance of HEIs. There is a highly significant positive effect between knowledge management, transformational leadership, and sustainable performance when the p-value equals 0.000. Knowledge management has a positive significant mediating effect between climate for change (t-value = 3.261) and process for change (t-value = 2.915) and sustainable performance where p-value is 0.001 and 0.004, respectively. There is no mediation of knowledge management between change for readiness and sustainable performance when the p-value is greater than 0.05. The model has confirmed a positive significant mediation of transformational leadership between climate for change and the sustainable performance of HEIs (t-value = 2.556 and p-value = 0.011). Transformational leadership fails to exert a mediation effect on change process, readiness for change, and the sustainable performance of HEIs. However, green teams fail to moderate the relationship between transformational leadership, knowledge management, and the sustainable performance of HEIs when the p-value = 0.741 and 0.112, which is greater than the significance level of 0.05.

Figure 2.

Structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM 4.0).

Table 6.

Hypothesis testing.

6. Test for Heteroskedasticity Test

To confirm the robustness of the regression model, a modified Breusch–Pagan test for heteroskedasticity was performed in SPSS version 29. The results for climate for change and predictors show a significance value of 0.066, which is non-significant, confirming that there is no linear functional relationship between predictors and residuals of variances see Table 7.

Table 7.

Modified Breusch–Pagan test for heteroskedasticity.

7. Discussion

The extant literature provides an appreciable number of research studies exploring the relationship between readiness for change and knowledge management within the fields of services and manufacturing firms [119]. However, the relationship between the constructs in the context of HEIs is in infancy stage, and there is dire need to have an in-depth exploration of the relationship for promoting sustainable performance in HEIs. The research studies have explored the relationship between readiness for change and knowledge management in different services and manufacturing companies. However, in the context of HEIs, examining the relationship between the abovementioned constructs has recently gained attention, and research is still in the early stages. This study aims to investigate the relationship between readiness for change and the sustainable performance of HEIs in Malaysia. Other researchers have confirmed that readiness for change directly affects sustainable development in organizations [119]. Arshad and Sabeen found that readiness for change has a significant effect on employee performance in HEIs in Pakistan [120]. There is a positive relationship between change management and employee productivity [94]. Based on these grounds from past research, the relationship between change management and knowledge management has been confirmed and thus strengthened the foundations of institutional theory and RBV theory.

There is a positive relationship between readiness for change and knowledge management as reflected through the findings of the current study. Researchers of a previous study found a positive effect of readiness for change and knowledge management on the effectiveness of private organizations [121]. A case study at Universidad Politécnica de Madrid confirmed that readiness for change was a contributing factor for acquiring knowledge management strategies and implementing SDGs successfully in HEIs [122]. Also, another study found a positive effect of university teachers’ readiness for change on sustainable development curricula [123]. The findings confirm that change management significantly enhances knowledge management practices, which in turn positively impacts sustainable performance. This indicates that HEIs that are prepared to embrace organizational changes are better equipped to implement effective knowledge management strategies, ultimately leading to improved long-term sustainability.

The findings of this study confirmed the positive relationship between knowledge management and corporate sustainability performance [97], which are aligned with the results of the present study. Our findings that knowledge management has a positive impact on the sustainability performance of HEIs have managerial implications for academia aiming to improve long-term success and sustainability. Knowledge management plays a key role in the effective use of knowledge and dissemination of knowledge that can lead to enhanced decision-making capabilities [124], innovative technological advancements [125], and enhanced organizational performance [126].

Knowledge management provides HEIs with the ability to systematically grasp, store, and utilize valuable knowledge from both internal and external sources. Investing in knowledge management processes and systems by HEIs enables them to have innovative and creative ideas to have a competitive advantage and to contribute to sustainable performance. In addition, the learning environment, upbringing, and training of students under the supervision of teaching faculty focusing on research for sustainability knowledge and technology have long-term impacts on institutions, organizations, and industries where the students are engaged in their professional life later on.

Notably, this study also explores the role of green teams as a potential moderator between knowledge management and sustainable performance. However, the results show that green teams do not significantly influence the relationship between these variables. This suggests that, while green teams may play a role in environmental management, their contribution to enhancing knowledge management for sustainable performance in HEIs may be limited or require additional factors to be effective. Numerous advantages of employee involvement and green teams have been emphasized in the existing body of literature on environmental management [54]. Nevertheless, the aforementioned research primarily possesses a theoretical orientation or relies on a restricted set of case studies. The implementation of employee engagement teams can yield positive outcomes in terms of mitigating toxicity and minimizing waste [101]. This study highlights the importance of fostering organizational readiness for change, as it directly contributes to the better management of knowledge, which is essential for achieving sustainability goals. The lack of significant moderation by green teams also invites further investigation into the conditions under which such teams could be more effective in supporting sustainable initiatives in educational settings. The discussion emphasizes the need for institutions to focus on readiness for change and effective knowledge management as key components of their sustainability strategies, especially in response to global challenges and competitive pressures.

The role of knowledge management as a mediator between readiness for change and sustainable performance of higher education institutions (HEIs) is a significant finding in this study. These results are in line with the findings of a previous study that found a positive mediation of knowledge management between corporate culture and sustainability performance [98]. The positive mediation effect of knowledge management indicates that change management alone is not sufficient to drive sustainable performance. Instead, HEIs can manage and leverage knowledge effectively that enhances the link between an institution’s readiness to embrace change and its ability to sustain performance over the long term. Knowledge management acts as a catalyst by transforming readiness for change into actionable insights and strategies. When an institution is ready for change, the processes and behaviors necessary for implementing that change become more efficient through effective knowledge management practices. This is consistent with the previous literature, which emphasizes that managing knowledge—through its acquisition, dissemination, and application—enables organizations to adapt better to new strategies and technologies and to respond to changing external environments. In the context of HEIs, knowledge management ensures that the collective experience and expertise within the organization are utilized to support sustainable practices, whether in environmental, financial, or social dimensions.

Leadership within HEIs will play a crucial role in embedding these values into the organizational culture, ensuring that knowledge management is actively used to enhance performance and sustainability outcomes. Transformational leadership plays a pivotal role in driving organizational change and fostering sustainable performance in HEIs. Leaders who exhibit transformational qualities such as visionary communication, inspirational motivation, and emotional connection are better equipped to inspire faculty and staff to embrace sustainability initiatives. By articulating a clear vision for sustainability and aligning it with institutional goals, transformational leaders reduce resistance to change and create a culture of innovation and adaptability. For instance, studies highlighted how transformational leaders empower employees to go beyond their self-interests and contribute to collective sustainability goals [21,70]. In the context of HEIs, this leadership style is particularly effective in mobilizing diverse stakeholders, from faculty to students, to adopt green practices and integrate sustainability into curricula and operations.

The findings of this study underscore the mediating role of transformational leadership in the relationship between organizational change management and sustainable performance. Transformational leaders act as bridges, translating change initiatives—such as readiness for change and climate for change—into actionable sustainability strategies. For example, leaders who foster a supportive climate for change encourage employees to experiment with innovative sustainability practices, such as energy-efficient technologies or waste-reduction programs. This aligns with prior research [15,127], which demonstrates that transformational leadership enhances organizational change capability by building trust and commitment among employees. In HEIs, this mediation is critical, as leaders must navigate complex institutional structures and diverse stakeholder interests to achieve long-term sustainability outcomes.

Additionally, the findings suggest that institutions with strong knowledge management frameworks and transformational leaders are better equipped to implement changes that lead to sustainable performance. Knowledge management not only supports the organization in navigating through change but also plays a vital role in maintaining competitive advantages and achieving continuous improvement. As the research shows, the effective mediation of knowledge management and transformational leadership between change management and sustainable performance reinforces the need for HEIs to invest in knowledge infrastructure, the training of transformational leaders, and systems that facilitate knowledge flow across all levels of the organization.

8. Practical Implications

The findings of this study have significant implications for employees, policymakers, and higher education institutions (HEIs) in Malaysia, especially concerning their ability to adapt to change and enhance sustainable performance through effective knowledge management.

For employees, this study emphasizes the need to be more adaptable and proactive in embracing organizational changes. With readiness for change playing a pivotal role in enhancing knowledge management and sustainable performance, employees must focus on developing their ability to adjust to new strategies, technologies, and organizational processes. Furthermore, employees are encouraged to engage in continuous learning and knowledge sharing, as these practices contribute to institutional sustainability. In a knowledge-driven environment, collaboration between employees across departments and functions will be essential to fostering an open culture where information flows freely, allowing the institution to make informed and innovative decisions. Additionally, the emphasis on knowledge management provides opportunities for employees to take on leadership roles, particularly those who are proactive in managing and sharing knowledge within their organizations.

For the Malaysian government, these findings suggest the importance of developing policies and frameworks that support HEIs in their efforts to embrace organizational change and improve sustainability. The government, particularly the Ministry of Education, can play a crucial role in incentivizing HEIs to adopt knowledge management practices and sustainability-focused initiatives. This could include offering grants, funding, or recognition to institutions that successfully implement these strategies. Furthermore, the government may need to establish monitoring and evaluation mechanisms to assess HEIs’ progress toward sustainability goals, ensuring that their efforts align with national educational policies and global sustainability objectives such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Through policy development and oversight, the government can help HEIs strengthen their role as drivers of sustainable development in Malaysia.

For HEIs themselves, this study highlights the importance of integrating knowledge management as a strategic asset in their pursuit of sustainable performance. HEIs need to prioritize investments in systems and infrastructure that facilitate the capture, sharing, and application of knowledge across their institutions. By doing so, they ensure that the organizational readiness for change is effectively translated into sustainable practices that contribute to long-term institutional success. Additionally, HEIs must foster a culture that embraces change, encouraging innovation, continuous learning, and cross-departmental collaboration. Leadership within HEIs will play a crucial role in embedding these values into the organizational culture, ensuring that knowledge management is actively used to enhance performance and sustainability outcomes.

Moreover, HEIs that excel in managing knowledge and sustainability initiatives will gain a competitive edge in the global education market. Institutions that demonstrate a commitment to sustainability are likely to attract students, faculty, and research funding, thereby enhancing their reputation both domestically and internationally. In the broader context, these institutions can also position themselves as leaders in sustainability education, contributing to Malaysia’s role in global discussions on sustainable development. Therefore, the findings of this study provide a strategic roadmap for HEIs to enhance their sustainability efforts while achieving a competitive advantage in the education sector.

9. Conclusions

This study highlights the critical role of organizational change management, transformational leadership, and knowledge management in driving sustainable performance in HEIs. The findings reveal that readiness for change and climate for change significantly influence sustainability outcomes, with transformational leadership and knowledge management acting as key mediators. Transformational leaders inspire and align stakeholders toward sustainability goals, while effective knowledge management fosters innovation, collaboration, and data-driven decision making. However, the moderating role of green teams was not significant, suggesting the need for further exploration of their impact. This study contributes to the literature by integrating institutional theory, and the RBV theory provides a holistic framework for HEIs to navigate external pressures and leverage internal resources for sustainability. Future research should explore longitudinal designs and additional moderators to deepen understanding. These insights provide actionable strategies for HEIs to enhance their sustainability performance and contribute to global sustainability goals.

10. Limitations and Future Recommendations

The business research has certain limitations as the data measure human behavior using questionnaires. The present study is a cross-sectional study that provides data only at a specific time; however, longitudinal studies help to decipher the mechanism of change readiness and sustainable performance in HEIs. The present study is conducted in private HEIs in Malaysia, so the results are not generalizable to other industries and in other countries. Therefore, it is recommended to adopt the latter approach in future research. There is always room for social desirability bias in survey-based research, and, despite assurance to respondents about the privacy and anonymity of data, this study has also faced social desirability bias to a small extent.

The same framework can have different results in different industries and different countries. Secondly, further studies can use different constructs, for instance, transformational leadership, green employee commitment, GHRM practices, and perceived organizational support to analyze the mechanism through which change management can impact the sustainable performance of HEIs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B.U., J.A. and K.A.M.A.; writing, methodology, and statistical analysis, J.A.; writing—review and editing, S.B.U. and M.A.B.M.B.; supervision, K.A.M.A. and W.M.H.W.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research study was conducted under the guidelines provided by UKM Research Ethics Secretariat and approved by the committee reference no. UKM/PP/111/8.

Informed Consent Statement

An informed consent was shared with participants of this study. After they agreed to participate in the present study, a survey questionnaire was filled by the respondents after confirming that the data will be used only for research purposes and that the privacy and confidentiality of data will not be violated at any given time. Additionally, it was affirmed by the researcher that she will discard the data properly after using them for research purposes.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest among authors in publishing this article.

References

- Arora, P. Life below land: The need for a new sustainable development goal. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1215282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Open Working Group Proposal for Sustainable Development Goals. 2015. Available online: https://undocs.org/A/68/970 (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Savolainen, K. Education as a Means to World Peace: The Case of the 1974 UNESCO Recommendation. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Jyväskylä, Jyväskyläc, Finland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bautista-Puig, N.; Lozano, R.; Barreiro-Gen, M. Developing a sustainability implementation framework: Insights from academic research on tools, initiatives and approaches. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 11011–11031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.; Halverson, R. Rethinking Education in the Age of Technology: The Digital Revolution and Schooling in America, 2nd ed.; Teachers College Press, Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hesselbarth, C.; Schaltegger, S. Educating change agents for sustainability–learnings from the first sustainability management master of business administration. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 62, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagendra, H.; Bai, X.; Brondízio, E.; Lwasa, S. The urban south and the predicament of global sustainability. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigier, M.; Ouellet-Plamondon, C.; Spiliotopoulou, M.; Moore, J.; Rees, W. To what extent is sustainability addressed on an urban scale and how aligned is it with Earth’s productive capacity? Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 96, 104655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wals, A. Sustainability in higher education in the context of the UN DESD: A review of learning and institutionalization processes. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 62, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikel-Hong, K.; Li, N.; Yu, J.; Chen, X. Resistance to change: Unraveling the roles of change strategists, agents, and recipients. J. Manag. 2024, 50, 1984–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent, J.D.; Lovelace, K.J. Employee Engagement, Positive Organizational Culture, and Individual Adaptability. Horizon 2018, 26, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adandani, T.; Asiami, N. The Role of Transformational Leadership in Facing the Challenges of Organizational Change. J. Fokus Manaj. 2023, 3, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channuwong, S.; Wongsutthirat, K.; Snongtaweeporn, T.; Patcharapitiyanon, D.; Sawangwong, B.; Suebchaiwang, P.; Niamsri, P.; Benjawatanapon, W.; Roung-Onnam, R. The role of leadership for modern organizational change. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2023, 11, 919–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busari, A.H.; Khan, S.N.; Abdullah, S.M.; Mughal, Y.H. Transformational leadership style, followership, and factors of employees’ reactions towards organizational change. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 2019, 14, 181–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.T.; Le, P.B. Impacts of transformational leadership on organizational change capability: A two-path mediating role of trust in leadership. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2024, 33, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, B.; Linski, C.M. Shifting the paradigm: Reevaluating resistance to organizational change. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2016, 29, 963–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, C.; Hind, P.; Magala, S. Sustainability and the need for change: Organisational change and transformational vision. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2012, 25, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burawat, P. The relationships among transformational leadership, sustainable leadership, lean manufacturing and sustainability performance in Thai SMEs manufacturing industry. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2019, 36, 1014–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, P.; Feng, M.; Wang, J. Differentiated transformational leadership, conflict and team creativity: An experimental study in China. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2022, 17, 1679–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mungkung, R.; Sorakon, K.; Sitthikitpanya, S.; Gheewala, S. Analysis of Green Product Procurement and Ecolabels towards Sustainable Consumption and Production in Thailand. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 28, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]