A Study on Herders’ Satisfaction with the Transfer of Grassland Contracting Rights and Its Influencing Factors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Data Sources

2.2. Basic Characteristics of the Sample

2.3. Research Hypothesis

2.4. Description of Variables

2.5. Model

2.5.1. Logistic Model

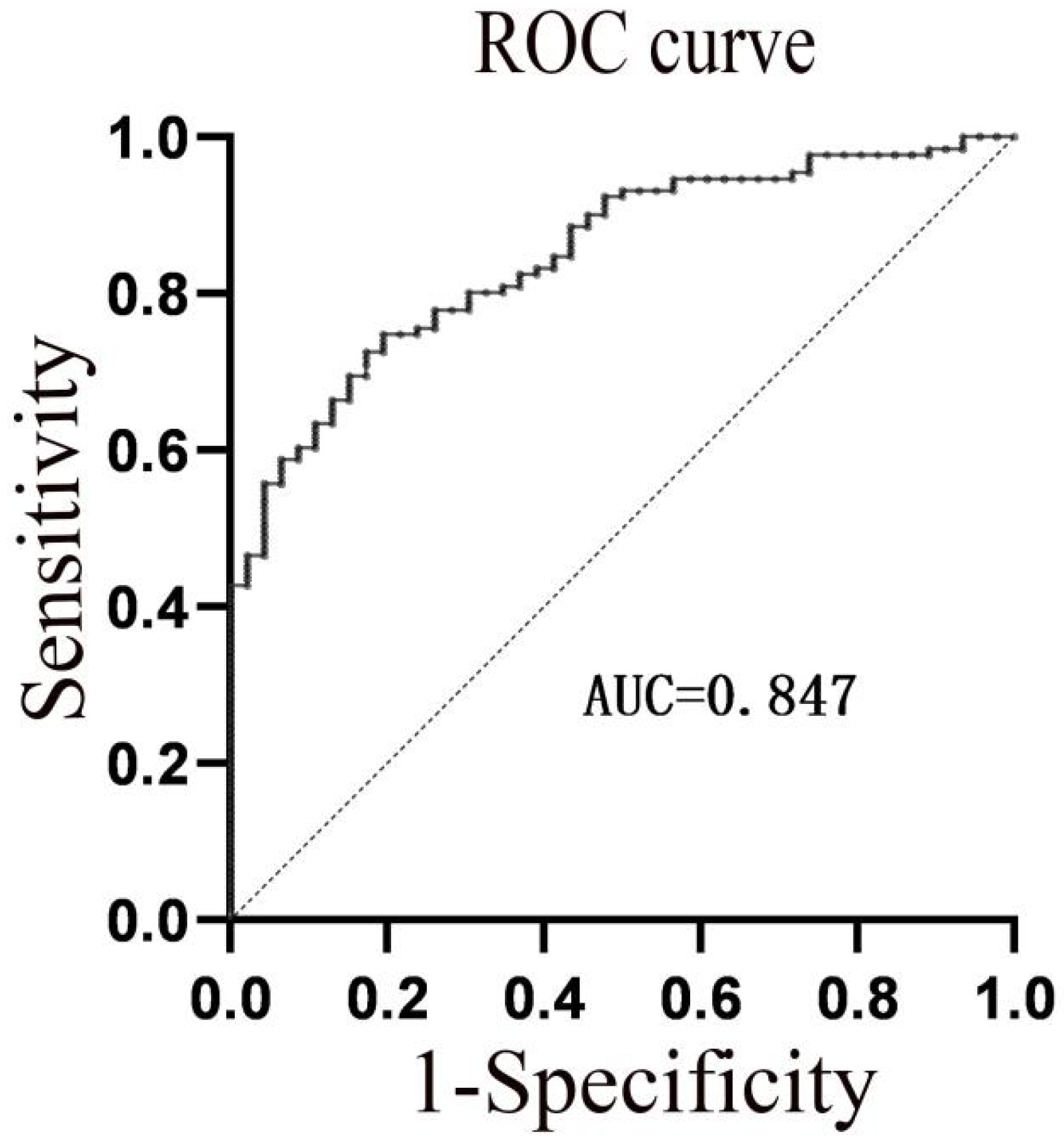

2.5.2. ROC Curve

2.5.3. Combination of Logistic Model and ROC Curve

3. Results

3.1. Redundancy Analysis of Variables

3.2. Influencing Factors of Herder’s Satisfaction

3.3. ROC Curve Analysis and Optimal Threshold Measurement

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Herders’ satisfaction with grassland contract management right transfer is higher overall. In the study area, 85.31 percent of the herders are satisfied with grassland transfer, while 14.69 percent are dissatisfied with grassland transfer. Through the transfer of grassland contract management rights, herders are able to increase their incomes, and some herders can work or do business in towns and cities, broadening the sources of family income, which further increases herders’ satisfaction with the transfer, but there are some problems and challenges for herders in the process of non-herding employment, for example, age, low level of education, lack of labor skills, perception of risk, and so on.

- (2)

- Annual non-herding income is an important factor affecting herders’ satisfaction. Non-herding income can improve the economic stability of herders, so families engaged in non-herding income wanting to obtain higher income must be linked to a wider range of social resources; however, due to the herders’ own reasons for dealing with the job market risk of the ability to resist weakness, if they want to ensure the stability of their non-herding incomes, they must strengthen their employment training to cope with market risks and meet the demands of the employment market so that they can better adapt to changes in the market and thus occupy a favorable position in the employment market.

- (3)

- The ROC curve tests the better prediction effect of the logistic model. By establishing a binary logistic regression model of herders’ satisfaction, the ROC curve was used to diagnose the predictive effect of the model and determine the critical point of the best predictive probability. The herder satisfaction variables were included in the model for judgment and prediction to understand the herder satisfaction status, and improvement measures were proposed based on the analysis results.

6. Policy Recommendations

- (1)

- Expanding the non-herding employment channels of transferring households and promoting flexible employment for herders. Firstly, the “project introduction” approach shouold be used to increase the number of non-herding employment opportunities for transferring households and to facilitate the centralized management of grasslands by transferring households. Secondly, education and training for herders should be provided to improve the quality of the labor force. Lastly, human capital should be raised and the quality of the labor force strengthened.

- (2)

- Further improve the relevant security system for transferring households and reduce herders’ worries. Firstly, the social security bureau should communicate with the local government to set differentiated social security payment standards for grassland-transfer-out households, grassland-transfer-in households, and non-transfer households. Secondly, the combination of grassland transfer and social welfare improves the herders’ happiness index and reduces their dependence on grassland.

- (3)

- Strengthen the publicity of the policy of grassland contract management right transfer and reduce the awareness of herdsmen’s risks. Firstly, publicity will be carried out in different ways and by different means. For example: lectures, meetings, television, posters, and so on. Secondly, play the leading role of the Gacha Committee. Encourage grassroots cadres to set an example and take the lead in learning. Third, strengthen the awareness of herders to participate in grassland transfer. Through guidance, publicity, and regular education, we can eliminate the traditional grassland transfer cognition and promote the formation of herders’ scientific participation in grassland transfer.

- (4)

- Improve the market for the transfer of grassland contractual management rights and regulate and guide the orderly transfer of grasslands. First, cultivate the grassland contract management right transfer market and promote the market competition mechanism. Second, strengthen the supervision and management of grassland transfer. Third, formulate standards for the transfer of rents.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pan, Q.M.; Sun, J.M.; Yang, Y.H.; Liu, W.; Li, A. Problems and countermeasures of grassland restoration and protection in China. Proc. CAS 2021, 36, 666–674. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Dong, X.Y. Institutional Logic of the Three Pastoral Issues: A Study on the Changes of Grassland Management and Property Rights System in China. J. China Agric. Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2013, 30, 94–107. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, Z.H.; Tian, M.J.; Yao, F.T. Digital technology, grassland transfer and grazing intensity-empirical evidence based on pure herding households in Inner Mongolia. J. Grassl. 2023, 31, 1842–1852. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, D.R.; Han, G.D.; Hou, X.Y.; Zhang, Y.J. Innovative Grassland Management Systems for Environmental and Livelihood Benefits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 8369–8374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.T. Current situation of ecological degradation of Inner Mongolian grassland and countermeasures. Econ. Res. Ref. 2011, 2391, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, X.Y. Impact of grassland net fencing on ecological environment development and preventive measures in Inner Mongolia. N. Econ. 2023, 05, 66–68. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Wu, Y. Research on the problem of grassland net fencing and pasture fragmentation in Inner Mongolia--an analysis based on household survey in Xilingol League. Frontier 2022, 4, 118–127. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, W.Z.; Tan, S.H. Evaluation of the effect of grassland ecological reward and subsidy policy—An institutional analysis based on the research of typical pastoral areas in Inner Mongolia. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 34, 196–201. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, G.J.; Liu, Y.G. The implementation effect of grassland ecological reward and subsidy policy—An empirical analysis based on the perspective of political sociology. Arid. Zone Res. 2015, 29, 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Su, L.F.; Qiu, H.G.; Liu, H.F.; Hou, L.L. The effect and mechanism of alternative livelihoods to improve the effectiveness of ecological compensation--a case study of grassland ecological compensation policy. J. Grass Ind. 2024, 33, 29–46. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.L.; Wu, R.L.G. An analysis of the de-pastoralization of herders in border crossing areas—Taking Bayintala Gacha of Xinbalhuzuo Banner as an example. Guizhou. Ethn. Studs. 2022, 43, 120–127. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, R.H. Research on the transfer of grassland contracted management right under the background of “three rights separation”—Taking Xilingol League as an example. Inn. Mong. Sci. Econ. 2019, 23, 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.T.; Qiao, J.; Na, Y.; Liu, Z.M.; Zhi, R.; Li, P. Discussion on Grassland Confirmation and Contracting and Informatization Management in China. J. Grassl. Ind. 2020, 29, 165–171. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.Z.; Gao, F.; Zhou, J. Does Grassland Rights Enforcement Improve Herders’ Perception of Property Rights Security? -An analysis of heterogeneity based on different types of herding households. Arid. Zone Res. Environ. 2022, 36, 61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Du, F.L.; Zhang, Y.X.; Song, L.Y. Comparative study on the production efficiency of grassland animal husbandry management subjects—Based on household survey data of Xilingol League. J. Cent. Univ. Natl. Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2019, 46, 88–96. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, S.H. Impact of pastoral system change on grassland degradation and its path. Agric. Econ. Issues 2020, 41, 115–125. [Google Scholar]

- Song, L.H. Exploration of grassland resource use right transfer system in China. CGJ 2015, 37, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, N.; Zhang, Y.F. Transfer behavior in grassland transfer of herdsmen in East Ujimqin Banner. Grassl. Sci. 2023, 40, 561–570. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.H.; Ding, W.Q.; Bai, R.; Yin, Y.T.; Hou, X.Y. Research on factors influencing the willingness of pastoral households to transfer grassland in Inner Mongolia. J. Livest. Ecol. 2021, 42, 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Meng, M. Analysis of factors influencing the willingness of herders to transfer artificial pastureland in Xinjiang. Arid. Zone Res. Environ. 2017, 31, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Su, C.C.K.; Hai, S.Y.T.; Liu, Z.Y. Analysis of factors affecting herders’ willingness to transfer grassland. Hubei Agric. Sci. 2022, 61, 191–195. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, W.Q.; Yang, Z.R.; Yin, Y.T.; Ma, C.; Hou, X.Y. Impacts of herders’ livelihood strategies on the transfer of grassland contractual management rights. Arid. Zone Res. Environ. 2019, 33, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, C.; Shao, L.Q.; Wang, S.; Zhang, H.; Chen, H.B. The effect of social network on the behavior of herding households’ grassland rental—taking four villages in Menyuan County, Qinghai Province as an example. Res. Sci. 2021, 43, 269–279. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, L.Q.; Zhang, Y.F.; Sa, R.L. Analysis of influencing factors of pasture land transfer in West Ujimqin Banner, Inner Mongolia. China Land Sci. 2014, 28, 20–24+32. [Google Scholar]

- Du, F.L.; Liu, Z.; Oniki, S. Factors Affecting Herdsmen’s Grassland Transfer in Inner Mongolia, China. Jpn. Agric. Res. Q. 2017, 51, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.L.; Fan, W.T.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Li, G.M.; Yang, D.Z.; Tang, Z. Analysis of factors influencing pastoral households’ grassland transfer behavior on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau—A survey based on 495 pastoral households. Chin. J. Grassl. 2019, 41, 128–133. [Google Scholar]

- Su, L.; Tang, J.; Qiu, H. Intended and unintended environmental consequences of grassland rental in pastoral China. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 285, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.Y.; Jiang, R.R. Leverage function of financial support in rural land transfer in China. JH Forum 2015, 07, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, W.F.; Meng, M.; Tang, H.S.; Li, J. Research on the influencing factors of herders’ pasture land transfer behavior in Fuhai County. China Agric. Res. Zone 2016, 37, 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, S.H.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, J.H.; Fang, X.J. Understanding grassland rental markets and their determinants in eastern inner Mongolia, PR China. Land Use Policy 2017, 67, 733–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.Y.; Xu, M.M.; Li, M. A study on the impact of grassland ecological bonus on herdsmen’s grassland transfer behaviour—A case study of Henan Mongolian Autonomous County in Qinghai Province. China Agric. Res. Zone 2023, 44, 191–202. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Bai, L.; Khan, H.S.; Li, H. The influence of the grassland ecological compensation policy on regional Herdsmen’s income and its gap: Evidence from six pastoralist provinces in China. Agriculture 2023, 13, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Guan, S.; Zhao, M.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Fan, Y. Grassland transfer and its income effect: Evidence from pastoral areas of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Land 2022, 11, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.Y.; Ge, W.; Xin, X.P.; Shao, C.L. Analysis of influencing factors of inconsistency between grassland transfer willingness and behavior. Arid. Zone Res. 2019, 33, 60–67. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.Y.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Xin, X.P.; Liu, X.C.; Shao, C.L. Research on pastoralists’ grassland transfer decision-making based on Heckman model. China Agric. Res. Zone 2020, 41, 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, T.; Liu, T.J.; Dong, C.L. Analysis of land transfer policy from the perspective of farmers’ satisfaction. J. Southwest Norm. Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2018, 43, 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, X.; Wang, C.; Wu, G.C. Transfer Characteristics, Risk Perception and Satisfaction with Land Transfer—A Survey Based on 1008 Farm Households in the Yangtze River Delta Region. Agric. Econ. Manag. 2020, 60, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Gan, C.L.; Mei, Y.; Zhang, M. Analysis of factors influencing farmers’ satisfaction with farmland transfer under the framework of CSI theory--an example of a survey in a typical area of Wuhan urban circle. China Land Sci. 2017, 31, 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Ou, M.H.; Guo, J.; Lu, F.; Zhang, X.W. Analysis of factors influencing farmers’ satisfaction with farmland transfer. J. Northwest AF Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2018, 18, 112–120. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.Y.; Lin, Y.F. Analysis of Farmers’ Satisfaction with Land Transfer and Influencing Factors—A Survey Based on 288 Farmers’ Households in Southern Mountainous Areas of Ningxia. Ningxia Soc. Sci. 2015, 190, 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Su, B.; Liu, M. Research Progress on the Theory and Practice of Grassland Eco-Compensation in China. Agriculture 2022, 12, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.J.; Liu, X.Y. A study on herders’ satisfaction with grassland ecological bonus policy in Gansu pastoral areas. J. Grass Ind. 2019, 28, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Deng, H. Construction and Influencing Factors of Voluntary Compensation Subjects for Herders—From the Perspective of Sustainable Utilization of Grassland Resources. Sustainability 2024, 1, 2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.Q.; Sun, P.F.; Zhao, K. Re-evaluation of grassland ecological subsidy policy based on heterogeneous farmers and herdsmen multidimensional satisfaction perspective. Arid. Zone Res. Environ. 2022, 36, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, W.; Jimoh, S.O.; Hou, X.; Shu, X.; Dong, H.; Bolormaa, D.; Wang, D. Grassland Ecological Subsidy Policy and Livestock Reduction Behavior: A Case Study of Herdsmen in Northern China. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 81, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, S.Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, B.B.; Li, L.H. Meta-analysis of factors influencing the satisfaction of grassland ecological reward policy. China G. J. 2019, 41, 134–143. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Yan, J.; Wu, Y. Review on the Socioecological Performance of Grassland Ecological Payment and Award Policy with the Consideration of an Alternate Approach for Nonequilibrium Ecosystems. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 2023, 87, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Hou, Y.; Langford, C.; Bai, H.; Hou, X. Herder stocking rate and household income under the Grassland Ecological Protection Award Policy in northern China. Land Use Policy 2019, 82, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Brown, C.; Qiao, G.; Zhang, B. Effect of Eco-compensation Schemes on Household Income Structures and Herder Satisfaction: Lessons from the Grassland Ecosystem Subsidy and Award Scheme in Inner Mongolia. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 159, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Xia, F.; Chen, Q.; Huang, J.; He, Y.; Rose, N.; Rozelle, S. Grassland ecological compensation policy in China improves grassland quality and increases herders’ income. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 46–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Rao, D.; Liu, M. The Impact of China’s Grassland Ecological Compensation Policy on the Income Gap between Herder Households? A Case Study from a Typical Pilot Area. Land 2021, 10, 1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.T.; Liu, D.; Jin, Y.S. Leshan. Grassland ecological compensation: Ecological performance, income impacts and policy satisfaction. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2016, 26, 165–176. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.Q.; Zhao, K. Grassland ecological subsidy perceptions, income impacts and policy satisfaction of farmers and herdsmen—An empirical comparison based on grazing ban areas and grass-livestock balance areas. Arid. Zone Res. Environ. 2019, 33, 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Q.L.; Qiao, J.; Li, B.L. The effects of cadre efficiency and procedural fairness on herders’ satisfaction with grassland subsidy policy—The case of Tibetan meat sheep farmers. Res. Agric. Mod. 2018, 39, 284–292. [Google Scholar]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. The Framing of Decisions and the Psychology of Choice. Science 1981, 211, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H.A. Rational choice and the structure of the environment. Psychol. Rev. 1956, 63, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Luo, X.; Zhang, C.; Song, J.; Xu, D. Can land transfer alleviate the poverty of the elderly? Evidence from rural China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wang, F. A study of the impact of land transfer decisions on household income in rural China. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, 276–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Zhou, M. Analysis of farmers’land transfer willingness and satisfaction based on SPSS analysis of computer software. Clust. Comput. 2019, 22, 9123–9131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Chen, J. Pastureland transfer as a livelihood adaptation strategy for herdsmen: A case study of Xilingol, Inner Mongolia. Rangel. J. 2017, 39, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.X.; Li, C.Q.; Zhao, M.J. The Effect, Mechanism, and Heterogeneity of Grassland Rental on Herders’ Livestock Production Technical Efficiency: Evidence from Pastoral Areas in Northern China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 14003–14031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, M.; Shi, W.; Lin, X.; Wu, B.; Wu, S. Revealing the spatiotemporal evolution pattern and convergence law of agricultural land transfer in China. PLoS ONE 2024, 9, e0300765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimoh, S.O.; Li, P.; Ding, W.Q.; Hou, X.Y. Socio-Ecological Factors and Risk Perception of Herders Impact Grassland Rent in Inner Mongolia, China. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 75, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wang, R.; Lu, Q. Land Tenure and Cotton Farmers’ Land Improvement: Evidence from State-Owned Farms in Xinjiang, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Peng, J.; Zhang, Y. Research on the impact of rural land transfer on non-farm employment of farm households: Evidence from Hubei Province, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.Q.; Zou, X.J.; Huang, J.W. Analysis of influencing factors on satisfaction of rural land ownership confirmation work: Based on survey data of rural households in Jiangxi Province. Res. World 2016, 09, 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, T.W. Analysis on the Satisfaction degree of land ownership and the influence of land transfer Behavior of ecological migrants. J. Yunnan Agric. Univ. Soc. Sci. 2023, 17, 102–109. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.Y. Introduction and application of ROC curve in the context of big data. Sci. EG 2021, 446, 81–84. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.Z.; Pan, X.P.; Ni, Z.Z. Application of logistic regression model in ROC analysis. China Health Stats. 2007, 24, 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Guo, R.C.; He, P.; Yu, L.Y. Landslide hazard evaluation based on improved mutation theory. Chin. J. Geol. Hazard Control 2023, 34, 121–128. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.Y.; Dong, J.J.; Wei, J.N.; Zhang, L.Z. Empirical study on the impact of grassland transfer on the income of herding households. Arid. Zone Res. Environ. 2019, 33, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.L. Impact of Grassland Transfer on Livestock Production and Herders’ Income on the Tibetan Plateau. Master’s Thesis, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, L.L.; Guo, D.; Ma, Y.; Xiao, H.S. Research on farmers’ land transfer satisfaction and its influencing factors—Taking the example of Shawan County. Tianjin Agric. Sci. 2018, 24, 25–29. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, J.X. Analysis of factors influencing farmland transfer behavior of farmers in the economic zone of the north slope of Tianshan Mountain—Taking Manas County as an example. China Agric. Res. Zone 2013, 34, 43–50+69. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, X.L.; Li, J.T.; Feng, Y.F.; Li, J.G.; Liu, H.H. Research on rural land transfer willingness and transfer behavior in Guangdong Province under the perspective of farmers’ cognition. Res. Sci. 2013, 35, 2082–2093. [Google Scholar]

- Che, L.; Du, H.F. Research on the current situation of employment risk perception of migrant workers near the workplace and its influencing factors. J. Xi’an Jiaotong Univ. Soc. Sci. 2019, 39, 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, H.; Hu, H.; Fu, S. Agricultural land property rights, non-farm employment risk and agricultural technical efficiency. Financ. T. Res. 2016, 27, 75–82. [Google Scholar]

| Research on Soums (Towns) | Survey and Investigate a Monastery | Sample Proportion/% |

|---|---|---|

| Gaorihan | Bayandele; Baoribaolage; Tulaga; Geriletu; Baorihushu | 18.64 |

| Bayanhua | Wulantuga; Bayanhubo; Bayandurige; Hanwula; Sarulabaolage | 19.77 |

| Wulanhalaga | Sarulatuya; Daburitu; Bayannaoer; Erihetuaobao; Arihushu | 12.99 |

| Haoletugaole | Alatangaole; Yarigaitu; Bayanhari; Wuritugaole; Bayanerihetu | 13.56 |

| Bayanhushu | Buridun; Chaidamu; Shutu; Bayanchagan; Hariatu | 18.09 |

| Jirengaole | Xianagayinbaolage; HuhexiliZhagesitai; Bayanhonggeer; Bayantala | 16.95 |

| Main Reasons | Frequency | Relative Frequency/% |

|---|---|---|

| Need money urgently | 58 | 32.77 |

| Lack of labor in the family | 65 | 36.72 |

| Flow with the others. | 1 | 0.56 |

| Migrate to a city for work | 27 | 15.25 |

| Raising livestock is hard work. | 3 | 1.69 |

| else | 68 | 38.42 |

| Variable Classification | Coding | Variable Name | Description of Variables | Maximum Values | Minimum Values | Average Values | Standard Deviation | Intended Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Herders’ personal characteristics | X1 | Gender | 0 = women; 1 = male | 1 | 0 | 0.64 | 0.48 | + |

| X2 | Age (years) | 1 = 18–30 years old; 2 = 31–40 years old; 3 = 41–50 years old; 4 = 51–60 years old; 5 = Age 61 and above | 5 | 1 | 3.1 | 1.05 | − | |

| X3 | Educational attainment | 1 = not attending school; 2 = junior high school; 3 = junior high school; 4 = senior high school; 5 = College or above | 5 | 1 | 2.5 | 1.15 | + | |

| X4 | Whether a member of the Communist Party of China | 0 = NO; 1 = Yes | 1 | 0 | 0.08 | 0.27 | + | |

| family characteristics | X5 | Number of laborers | numeric variable | 4 | 0 | 1.64 | 0.99 | + |

| X6 | Total annual income (ten thousand) | 1 = 1–5; 2 = 6–10; 3 = 11–15; 4 = 16–20; 5 = 21 and above | 5 | 1 | 2.19 | 1.1 | + | |

| X7 | Annual non-herding income (ten thousand) | 1 = 1–5; 2 = 6–10; 3 = 11–15; 4 = 16–20; 5 = 21 and above | 5 | 1 | 1.78 | 0.97 | + | |

| resource endowment | X8 | Grassland quality | 1 = Good; 2 = Average; 3 = Poor | 3 | 1 | 2.47 | 0.76 | + |

| X9 | Whether the grassland is fully transferred | 0 = No; 1 = Yes | 1 | 0 | 0.7 | 0.46 | + | |

| Grassland transfer characteristics | X10 | Rents (CNY) | 1 = 150 and below; 2 = 151–300; 3 = 301–450; 4 = 451–600; 5 = 601 and above | 5 | 1 | 2.31 | 0.81 | + |

| X11 | Fixed number of years | numeric variable | 12 | 1 | 3.78 | 1.48 | + | |

| policy perceptions | X12 | Level of understanding of grassland transfer policies | 1 = don’t know; 2 = know a little; 3 = knowledgeable; 4 = well known | 4 | 1 | 2.54 | 0.94 | + |

| X13 | Satisfactory status of the grassland transfer policy | 1 = very dissatisfied; 2 = not too satisfied; 3 = fairly satisfied; 4 = more satisfied; 5 = very satisfied | 5 | 1 | 3.95 | 0.89 | + | |

| risk expectations | X14 | Is there a fear of overgrazing by the other side after the transfer | 1 = Yes; 2 = Somewhat; 3 = No | 3 | 1 | 2.3 | 0.92 | − |

| X15 | whether they are worried about not being able to find a job after the transfer | 1 = Yes; 2 = Somewhat; 3 = No | 3 | 1 | 2.41 | 0.88 | − |

| The Real Situation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Projected results | Standard practice | Counter-example | Add up the total | |

| Standard practice | TP | FN | TP+FN | |

| Counter-example | FP | TN | FP+TN | |

| Add up the total | TP+FP | FN+TN | TP+FP+FN+TN | |

| X1 | X2 | X3 | X4 | X5 | X6 | X7 | X8 | X9 | X10 | X11 | X12 | X13 | X14 | X15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | 1.0000 | −0.1700 | 0.1700 | 0.0430 | 0.0690 | 0.1800 | 0.1100 | 0.1500 | −0.1000 | 0.1300 | −0.0530 | 0.1800 | 0.0940 | −0.0027 | 0.0780 |

| X2 | −0.1700 | 1.0000 | −0.4100 | 0.1400 | −0.1900 | −0.2700 | −0.1600 | 0.0440 | 0.1500 | −0.1300 | −0.0660 | −0.0820 | −0.0500 | 0.1500 | 0.1200 |

| X3 | 0.1700 | −0.4100 | 1.0000 | 0.1800 | 0.1700 | 0.2400 | 0.3200 | −0.0800 | 0.0490 | 0.0270 | −0.0039 | 0.0550 | 0.0079 | 0.0620 | −0.1200 |

| X4 | 0.0430 | 0.1400 | 0.1800 | 1.0000 | 0.0860 | 0.1900 | 0.1300 | −0.0100 | 0.0088 | −0.0670 | 0.0290 | 0.1400 | 0.0063 | −0.0560 | 0.1200 |

| X5 | 0.0690 | −0.1900 | 0.1700 | 0.0860 | 1.0000 | 0.4400 | 0.3100 | 0.0470 | −0.2500 | 0.1700 | 0.0550 | 0.1000 | 0.0260 | −0.0970 | 0.1500 |

| X6 | 0.1800 | −0.2700 | 0.2400 | 0.1900 | 0.4400 | 1.0000 | 0.6700 | 0.1500 | −0.3200 | 0.3000 | −0.0076 | 0.2200 | −0.0078 | −0.0240 | 0.1800 |

| X7 | 0.1100 | −0.1600 | 0.3200 | 0.1300 | 0.3100 | 0.6700 | 1.0000 | 0.0500 | 0.1200 | 0.1700 | 0.0440 | 0.1500 | −0.0190 | −0.0400 | −0.0420 |

| X8 | 0.1500 | 0.0440 | −0.0800 | −0.0100 | 0.0470 | 0.1500 | 0.0500 | 1.0000 | −0.0670 | 0.1600 | 0.0330 | 0.0930 | 0.0340 | 0.0450 | 0.1100 |

| X9 | −0.1000 | 0.1500 | 0.0490 | 0.0088 | −0.2500 | −0.3200 | 0.1200 | −0.0670 | 1.0000 | −0.1800 | 0.0450 | −0.0570 | 0.0190 | 0.0230 | −0.2800 |

| X10 | 0.1300 | −0.1300 | 0.0270 | −0.0670 | 0.1700 | 0.3000 | 0.1700 | 0.1600 | −0.1800 | 1.0000 | −0.1300 | 0.1800 | 0.1200 | 0.0570 | 0.0820 |

| X11 | −0.0530 | −0.0660 | −0.0039 | 0.0290 | 0.0550 | −0.0076 | 0.0440 | 0.0330 | 0.0450 | −0.1300 | 1.0000 | −0.1400 | −0.1100 | 0.0096 | −0.0990 |

| X12 | 0.1800 | −0.0820 | 0.0550 | 0.1400 | 0.1000 | 0.2200 | 0.1500 | 0.0930 | −0.0570 | 0.1800 | −0.1400 | 1.0000 | 0.3900 | 0.0025 | 0.0930 |

| X13 | 0.0940 | −0.0500 | 0.0079 | 0.0063 | 0.0260 | −0.0078 | −0.0190 | 0.0340 | 0.0190 | 0.1200 | −0.1100 | 0.3900 | 1.0000 | 0.0420 | 0.0870 |

| X14 | −0.0027 | 0.1500 | 0.0620 | −0.0560 | −0.0970 | −0.0240 | −0.0400 | 0.0450 | 0.0230 | 0.0570 | 0.0096 | 0.0025 | 0.0420 | 1.0000 | 0.1500 |

| X15 | 0.0780 | 0.1200 | −0.1200 | 0.1200 | 0.1500 | 0.1800 | −0.0420 | 0.1100 | −0.2800 | 0.0820 | −0.0990 | 0.0930 | 0.0870 | 0.1500 | 1.0000 |

| B | S.E | Wals | Sig | Exp(β) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender * | −0.892 | 0.482 | 3.421 | 0.064 | 0.410 |

| Age | 0.108 | 0.243 | 0.197 | 0.657 | 1.114 |

| Educational attainment | 0.315 | 0.229 | 1.890 | 0.169 | 1.370 |

| Whether a member of the Communist Party of China | 1.177 | 1.256 | 0.878 | 0.349 | 3.243 |

| Number of laborers | −0.291 | 0.242 | 1.445 | 0.229 | 0.748 |

| Total annual income *** | 3.258 | 0.946 | 11.855 | 0.001 | 25.990 |

| Annual non-herding income *** | −2.808 | 0.895 | 9.830 | 0.002 | 0.060 |

| Grassland quality | −0.249 | 0.288 | 0.749 | 0.387 | 0.780 |

| Whether the grassland is fully transferred *** | 1.572 | 0.567 | 7.688 | 0.006 | 4.815 |

| Rents ** | 0.813 | 0.318 | 6.533 | 0.011 | 2.255 |

| Fixed number of years | 0.019 | 0.139 | 0.018 | 0.893 | 1.019 |

| Level of understanding of grassland transfer policies | 0.087 | 0.244 | 0.127 | 0.722 | 1.091 |

| Satisfactory status of the grassland transfer policy ** | 0.645 | 0.265 | 5.936 | 0.015 | 1.905 |

| Is there a fear of overgrazing by the other side after the transfer | −0.006 | 0.240 | 0.001 | 0.982 | 0.995 |

| whether they are worried about not being able to find a job after the transfer ** | 0.516 | 0.243 | 4.490 | 0.034 | 1.675 |

| Constant | −6.667 | 2.059 | 10.483 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Sig 0.000 | <0.05 | Cox&snell R2 | 0.279 | ||

| Chi-square | 57.948 | Nagelkerke R2 | 0.409 | ||

| −2 log likelihood | 144.873a | Total sample | 177 | ||

| AUC | S.Ea | Sigb | Approaching the 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | |||

| 0.847 | 0.030 | 0.000 | 0.789 | 0.905 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bao, N.; Zhang, Y. A Study on Herders’ Satisfaction with the Transfer of Grassland Contracting Rights and Its Influencing Factors. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2158. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052158

Bao N, Zhang Y. A Study on Herders’ Satisfaction with the Transfer of Grassland Contracting Rights and Its Influencing Factors. Sustainability. 2025; 17(5):2158. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052158

Chicago/Turabian StyleBao, Narenmandula, and Yufeng Zhang. 2025. "A Study on Herders’ Satisfaction with the Transfer of Grassland Contracting Rights and Its Influencing Factors" Sustainability 17, no. 5: 2158. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052158

APA StyleBao, N., & Zhang, Y. (2025). A Study on Herders’ Satisfaction with the Transfer of Grassland Contracting Rights and Its Influencing Factors. Sustainability, 17(5), 2158. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052158