The Impact of Environmental Regulation on the Growth of Small and Micro Enterprises: Insights from China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Mechanism Analysis and Research Hypothesis

3.1. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypothesis

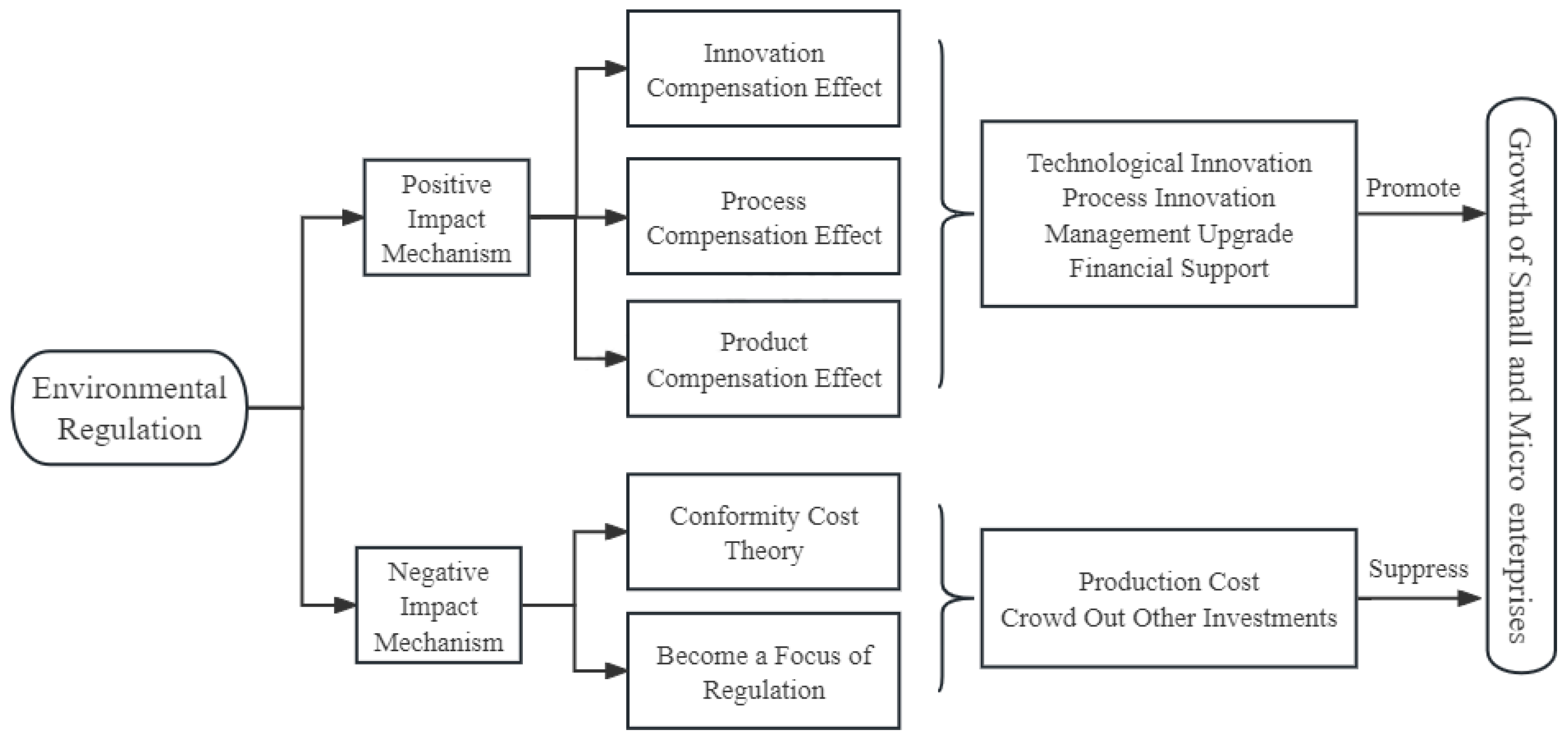

3.1.1. Direct Impact of Environmental Regulation on SMEs’ Growth

3.1.2. Mechanism Analysis of the Influence of Environmental Regulation

3.2. Research Methodology

3.2.1. Model Construction

3.2.2. Indirect Impact Mechanism Testing Model

4. Variable Selection and Data Sources

4.1. Variable Selection

4.2. Data Sources

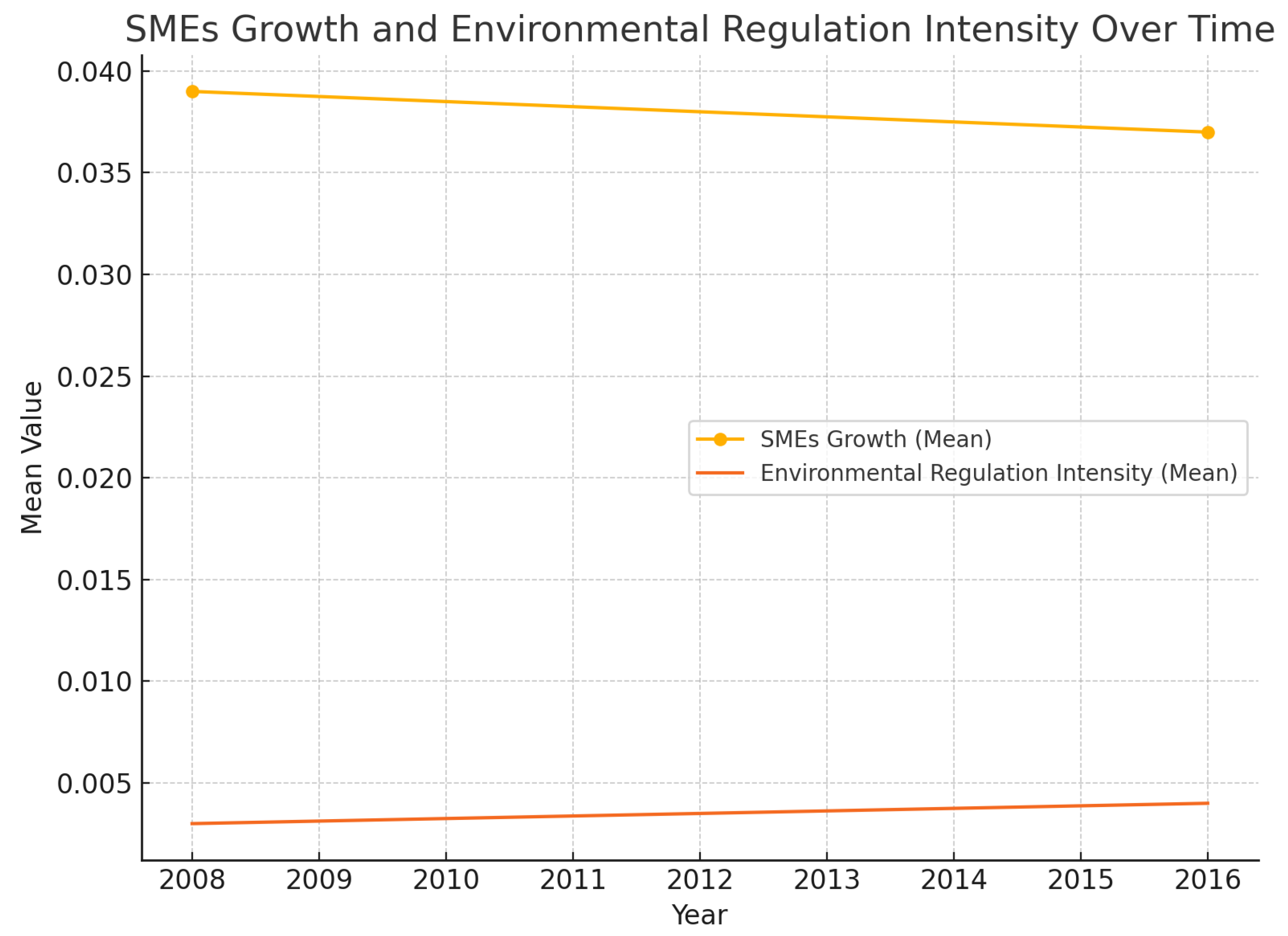

4.3. Descriptive Analysis

5. Results, Analysis, and Discussion

5.1. Identification of the Influence of Environmental Regulation

5.1.1. Inhibitory Effect of Environmental Regulation on SMEs’ Growth

5.1.2. Robustness Tests of Baseline Results

5.1.3. Promoting Innovation and Support Through Regulation

5.2. Heterogeneity Test

5.3. Theoretical Connections

6. Research Conclusions and Policy Implications

6.1. Research Conclusions

6.2. Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Peng, X. Strategic interaction of environmental regulation and green productivity growth in China: Green innovation or pollution refuge? Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 732, 139200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, J.; Xie, R.; Ma, C.; Fu, Y. Market-based environmental regulation and total factor productivity: Evidence from Chinese enterprises. Econ. Model. 2020, 95, 394–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, N.; Liao, H.; Deng, R.; Wang, Q. Different types of environmental regulations and the heterogeneous influence on the environmental total factor productivity: Empirical analysis of China’s industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 211, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. America’s green strategy. Sci. Am. 1991, 264, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, D.; Liu, X.; Xu, Y. Compliance cost theory: Environmental regulation and enterprise innovation. Environ. Econ. Policy Stud. 2024, 1, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Tang, L. Environmental regulation and the growth of the total-factor carbon productivity of China’s industries. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 296, 113078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Wang, Z.; Geng, S. How do environmental regulation and foreign investment behavior affect green productivity growth in the industrial sector? J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 287, 112282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Wang, K.; Zhang, C.; Wei, Y.M. Synergistic effects of environmental regulations on carbon productivity growth in China’s major industrial sectors. Nat. Hazards 2018, 95, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, N.; Wang, Q. Environmental regulation and environmental productivity: The case of China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 62, 758–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Apolito, E.; Galletta, S.; Iannuzzi, A.P.; Labini, S.S. Sustainability and bank credit access: New evidence from Italian SMEs. J. Res. Int. Bus. Finance 2024, 69, 102242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongyun, T.; Sohu, J.M.; Khan, A.U.; Junejo, I.; Shaikh, S.N.; Akhtar, S.; Bilal, M. Navigating the digital landscape: Examining the interdependencies of digital transformation and big data in driving SMEs’ innovation performance. J. Kybernetes. 2025, 54, 1797–1825. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, P.; Li, Y.; Ye, K. Environmental Regulation, Technological Innovation and Green Total Factor Productivity of Industrial Enterprises: An Analysis Based on Chinese Interprovincial Panel Data. Sci. Sci. Manag. S. & T. 2024, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Zhang, Y. Innovation mechanisms under stringent environmental policies. Environ. Policy Res. J. 2016, 18, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.; Li, X. Technological innovation as a moderating factor in environmental regulation. J. Econ. Policy 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Zhao, J. Environmental regulation stringency and firm performance: The role of regional industrial structures. J. Environ. Econ. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Lin, T.; Xiao, Q. The relationship between environmental regulation, green-technology innovation and green total-factor productivity: Evidence from 279 cities in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Du, Y. Spatial effect of environmental regulation on green innovation efficiency: Evidence from prefectural-level cities in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 286, 125032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, H.; Bressers, H.; Buchanan, K. Productivity growth and environmental regulations—Accounting for undesirable outputs: Analysis of China’s thirty provincial regions using the Malmquist–Luenberger index. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 2369–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; He, Y.; Zhou, J. Evaluating the effect of Chinese environmental regulation on corporate sustainability performance: The mediating role of green technology innovation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Xiang, Q. Environmental regulation, industrial innovation and green development of Chinese manufacturing: Based on an extended CDM model. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 176, 895–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosal, V.; Ye, Y. Environmental regulation and firm productivity: A review of recent literature. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2019, 98, 102259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Tang, B. Environmental regulation, industrial structure upgrading, and green economic efficiency in China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 136, 108671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Zhao, X. Low-carbon pilot policies and industrial enterprises’ growth: Evidence from China. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 290, 112592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Huang, J. Environmental regulation, innovation, and firm performance: Evidence from listed companies in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 339, 130662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; He, L. Environmental regulation and the productivity of Chinese firms: New evidence from firm-level data. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2024, 106, 102694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y. Assessing environmental regulation effects: Empirical analysis using system dynamics and firm-level data. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 195, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Qin, W. The moderating role of environmental regulation on green innovation and firm growth. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2024, 180, 121697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, N.; Liao, H. Different types of environmental regulations and their heterogeneous effects on environmental total factor productivity. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 236, 117987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, M.; Bond, S. Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1991, 58, 277–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Xu, X. Inclusive finance, SME growth, and digital technology. Econ. Res. J. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Wang, L. Digital transformation and SME growth in the global market. J. Glob. Bus. Res. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.; Duan, K.; Xu, L. Environmental regulation, innovation, and firm performance: Evidence from Chinese SMEs. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Yang, J. The U-shaped relationship between environmental regulation and green innovation in SMEs: Empirical analysis using firm-level data. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 238, 117920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Liu, X. Environmental regulation and the green innovation performance of Chinese firms: Evidence from SMEs. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 136, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Tang, L. Heterogeneity in firm size and the impact of environmental regulation on SME growth: Evidence from China. J. Econ. Policy 2022, 46, 341–357. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Van der Linde, C. Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, C.; Huang, H. Environmental regulation and firm innovation: Examining the Porter Hypothesis in China’s industries. Ind. Econ. J. 2024, 74, 812–827. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, L.; Chen, S. Compensatory policies for environmental regulation: A pathway to SME growth. Econ. Dev. Q. 2024, 34, 137–155. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Zhou, X. Government subsidies and environmental regulation: Impacts on SME growth and innovation. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2022, 60, 125–142. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Wang, Y. Policy support and green innovation in Chinese SMEs: An empirical analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Geng, Y.; Sarkis, J. Motivating green public procurement in China: An individual level perspective. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 126, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, N.; Wang, Q.; Yang, X. Environmental regulation and its effects on the industrial transformation of China: Empirical evidence from regions. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 119, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, A.B.; Peterson, S.R.; Portney, P.R.; Stavins, R.N. Environmental regulation and the competitiveness of U.S. manufacturing. J. Econ. Lit. 1995, 33, 132–163. [Google Scholar]

- Rubashkina, Y.; Galeotti, M.; Verdolini, E. Environmental regulation and competitiveness: Empirical evidence on the Porter Hypothesis from European manufacturing sectors. Energy Policy 2015, 83, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Mo, X.; Duan, K. Can Green Credit Policy Promote Firms’ Green Innovation? Evidence from China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, M. The Impact of Tax Burden on the Total Factor Productivity of SMEs. Master’s Thesis, Guangdong University of Finance Economics, Guangzhou, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, S. The Impact of Environmental Regulation on the Technological Complexity of Firm Exports under the KCAPC Policy. Master’s Thesis, Jiangxi University of Finance and Economics, Nanchang, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C. How to Use Information Technology to Promote the Upgrade of Comprehensive Budget Management in Enterprises. Contemp. Account. 2021, 7, 171–172. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, D.; Yan, Y. Environmental Regulation, Technological Innovation, and Green Total Factor Productivity in Manufacturing Enterprises. Urban Environ. Res. 2022, 2, 58–79. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Song, Z. A New Method for Measuring Corporate Operating Performance—Economic Value Added (REVA) and Revised Economic Value Added (REVA) Indicators. Account. Res. 1999, 1, 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, B.; Deng, X.; Yi, J. Digital dynamic capability, value co-creation, and digital transformation of small and medium-sized enterprises: The moderating effect of digital technology maturity. Qinghai Soc. Sci. 2022, 6, 012. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, Z.; Du, J.; Kong, Y.; Cui, X. Financial development, environmental regulation, and corporate green technology innovation: Evidence from Chinese listed companies. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 62, 105122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Li, M. Environmental regulatory system reform and corporate ESG ratings: Evidence from China. Econ. Model. 2024, 135, 135106710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Xie, X. Does Market-Based Environmental Regulatory Policy Improve Corporate Environmental Performance? Evidence from Carbon Emission Trading in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.; Li, Z.; Du, M.; Yang, T. Corrigendum to ”Government venture capital and innovation performance in alternative energy production: The moderating role of environmental regulation and capital market activity”. Energy Econ. 2025, 129, 107196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | 2008 | 2016 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | Std Dev | Min | Max | Mean | Std Dev | Min | Max |

| Y | 0.039 | 0.011 | 0.017 | 0.064 | 0.037 | 0.013 | 0.011 | 0.062 |

| Er | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.008 | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.010 |

| N | 3.271 | 4.172 | −56.823 | 81.222 | 1.382 | 3.000 | −46.507 | 54.885 |

| C | 102.342 | 2706.728 | 0.000 | 17.198 | 136.298 | 5751 | 0.000 | 1,500,000 |

| G | 327.963 | 88,789 | 0.000 | 911,598 | 413.890 | 70,457 | 0.000 | 22,100,000 |

| X | 52.990 | 7916 | 0.000 | 1,335,350 | 12.212 | 894 | 0.000 | 256,000 |

| F | 52.945 | 5155 | 0.000 | 39,400,000 | 54.861 | 11,324 | 1,560,000 | 290,000 |

| A | 0.556 | 1.470 | 0.000 | 3,335,300 | 0.333 | 1.230 | 0.000 | 11.553 |

| W | 1.460 | 3.335 | 0.000 | 891,600 | 1.425 | 3.362 | 0.000 | 16.457 |

| S | 1.164 | 66.936 | 0.000 | 14.535 | 8.225 | 858.330 | 0.000 | 223,000 |

| Z | 72.285 | 2406 | −1404 | 20,134 | 133.785 | 8235 | −1736 | 1,630,000 |

| M | 7.268 | 0.910 | 2.614 | 9.585 | 8.107 | 0.867 | 3.624 | 9.829 |

| I | 0.376 | 0.077 | 0.086 | 0.777 | 0.461 | 0.083 | 0.207 | 0.764 |

| J | 0.362 | 1.416 | 0.000 | 13.225 | 0.452 | 1.798 | 0.000 | 11.503 |

| P | 1.444 | 2.649 | 0.000 | 15.041 | 0.897 | 2.236 | 0.000 | 13.817 |

| Variable Type | Variable Name | Symbol | Variable Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Firm Growth | Y | Calculated using the method described in Section 4.1 |

| Independent Variable | Environmental Regulation | Er | Calculated using the method described in Section 4.1 |

| Control Variable | Net Cash Flow | N | Logarithmic value of (Net Cash Flow + 1) |

| Operating Cost | C | Operating Costs ÷ Operating Revenue × 100% | |

| Management Expenses | G | Management Expenses ÷ Operating Revenue × 100% | |

| Sales Expenses | X | Sales Expenses ÷ Operating Revenue × 100% | |

| Financial Expenses | F | Financial Expenses ÷ Operating Revenue × 100% | |

| Advertising Expenses | A | Logarithmic value of (Advertising Expenses + 1) | |

| Export Capacity | W | Logarithmic value of (Export Amount + 1) | |

| Tax Burden | S | Logarithmic value of (Business Taxes and Additional Charges + 1) | |

| Debt-to-Asset Ratio | Z | Initial Debt ÷ Initial Assets × 100% | |

| Market Size | M | Logarithmic value of the GDP of prefecture-level cities | |

| Industrial Structure | I | Value-Added of Tertiary Industry ÷ Regional GDP × 100% | |

| Mechanism Variable | Technological Innovation | J | Logarithmic value of (R&D Expenditures + 1) |

| Policy Support | P | Logarithmic value of (Subsidy Income + Tax Refunds Received + 1) |

| Variable | Y | Y | Y |

|---|---|---|---|

| L2.Y | 0.081 *** (6.93) | 0.067 *** (3.67) | −0.021 (−0.28) |

| Er | −0.339 ** (−2.20) | / | / |

| L2.E | / | −0.142 *** (−3.17) | / |

| L4.Er | / | / | −0.671 (−1.56) |

| N | 0.000 (0.58) | 0.001 (1.47) | 0.001 (0.60) |

| C | 0.005 *** (12.68) | 0.004 *** (7.16) | −0.001 (−0.56) |

| G | 0.000 (0.76) | 0.000 (0.84) | 0.000 * (1.70) |

| X | −0.000 ** (−2.42) | −0.000 *** (−4.10) | 0.000 (0.07) |

| F | −0.000 (−1.09) | −0.000 (−1.18) | −0.000 (−1.39) |

| A | −0.000 (−0.41) | −0.000 (−0.49) | −0.000 (−0.31) |

| W | −0.000 *** (−2.76) | −0.000 ** (−2.64) | −0.000 (−0.49) |

| S | 0.001 (0.46) | 0.002 (0.71) | 0.005 (1.17) |

| Z | 0.000 *** (3.05) | 0.000 *** (3.94) | −0.000 (−0.01) |

| M | 0.012 ** (2.29) | 0.025 *** (7.83) | 0.011 (0.45) |

| I | −0.074 *** (−5.90) | −0.054 *** (−3.68) | 0.112 (1.56) |

| Year Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Province Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| _cons | 10.898 (0.41) | 10.122 (0.49) | −0.306 (−0.11) |

| AR(1) | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.057 |

| AR(2) | 0.077 | 0.397 | 0.489 |

| Sargan | 0.076 | 0.061 | 0.068 |

| Variable | Substituting Independent Variable | Substituting Dependent Variable | Excluding Outliers | Reghdfe | Xtreg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L2.Y | 0.088 *** (5.79) | 0.077 *** (5.09) | 0.081 *** (6.87) | / | / |

| Er | −0.446 *** (−6.48) | −36.890 ** (−1.78) | −0.336 ** (−2.05) | −0.283 *** (−30.07) | −0.139 *** (−21.83) |

| Control Variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Province Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| _cons | 6.055 | 1600 | 10.897 | 59.882 | 0.064 |

| AR(1) | 0.016 | 0.003 | 0.002 | / | / |

| AR(2) | 0.173 | 0.077 | 0.089 | / | / |

| Sargan | 0.000 | 0.203 | 0.096 | / | / |

| Technological Innovation (Equation (2)) | Policy Support (Equation (3)) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sobel Test | ||

| Er × J | 0.0230 *** (0.001) | / |

| Er × P | / | 0.0164 *** (0.0015) |

| Z-Statistic | 19.4 *** (0.0230) | 10.92 *** (0.0164) |

| Classification Variable | Sample Classification | Control Variables | Year Fixed Effects | Province Fixed Effects | Impact Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geographic Location | Eastern SMEs | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0.014 |

| Central SMEs | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0.063 | |

| Western SMEs | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0.264 ** | |

| Economic Environment | Yangtze River Economic Belt | Yes | Yes | Yes | −0.159 |

| Non-Yangtze River Economic Belt | Yes | Yes | Yes | −0.740 ** | |

| Ownership Structure | State-Owned Enterprises | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0.032 |

| Private Enterprises | Yes | Yes | Yes | −0.332 * | |

| Exporting Firms | Exporting SMEs | Yes | Yes | Yes | −0.093 |

| Non-Exporting SMEs | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0.352 ** | |

| Tax-Paying Firms | Large Tax-Paying SMEs | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0.616 |

| Small Tax-Paying SMEs | Yes | Yes | Yes | −0.744 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhong, Y.; Yao, X.; Lin, W. The Impact of Environmental Regulation on the Growth of Small and Micro Enterprises: Insights from China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2118. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052118

Zhong Y, Yao X, Lin W. The Impact of Environmental Regulation on the Growth of Small and Micro Enterprises: Insights from China. Sustainability. 2025; 17(5):2118. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052118

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhong, Yufen, Xingyuan Yao, and Weiming Lin. 2025. "The Impact of Environmental Regulation on the Growth of Small and Micro Enterprises: Insights from China" Sustainability 17, no. 5: 2118. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052118

APA StyleZhong, Y., Yao, X., & Lin, W. (2025). The Impact of Environmental Regulation on the Growth of Small and Micro Enterprises: Insights from China. Sustainability, 17(5), 2118. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052118