1. Introduction

Rapid urbanization on a global scale has led to significant challenges, such as environmental degradation, resource depletion, and social inequality. These challenges underscore the pressing need for settlements that integrate sustainability across ecological, social, and cultural dimensions [

1,

2,

3]. Among various sustainable settlement models—including eco-cities, permaculture communities, and co-housing projects—ecovillages represent a particularly compelling paradigm due to their holistic approach to sustainability [

4,

5,

6].

Ecovillages are intentional or traditional communities designed to achieve long-term sustainability by integrating ecological, social, and cultural resilience. According to the Global Ecovillage Network (GEN), an ecovillage is not merely a location; it is a thoughtfully and collaboratively designed community where individuals unite to create a shared home with a common vision. Ecovillages aim to foster mindful relationships with one another, their immediate environment, and the broader global ecosystem. They strive to weave together environmental stewardship, social harmony, alternative economies, and a regenerative culture into their everyday lives [

7]. Unlike other sustainable settlement types, ecovillages emphasize community-led initiatives, self-sufficiency, and localized solutions to environmental and social challenges [

8,

9]. They align closely with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 11 (SDG 11), which aims to make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable [

10,

11,

12]. These communities serve as experimental hubs for innovative practices, from renewable energy use to sustainable agriculture, offering scalable solutions to broader urban sustainability challenges [

13,

14].

Historically, ecovillages emerged as a response to modern industrial society’s ecological and social crises. The concept gained formal recognition in the 1990s with the establishment of the GEN, providing a platform for connecting and supporting these communities worldwide [

15,

16,

17]. Early examples, such as Solheimar in Iceland and Findhorn in Scotland, demonstrated the feasibility of creating self-sufficient communities based on ecological stewardship and social equity principles [

18,

19]. Subsequent studies have highlighted the role of ecovillages in advancing sustainability by integrating local traditions with innovative practices [

20,

21,

22].

A key distinction between intentional ecovillages and traditional village transformations is that the latter builds upon existing settlements and cultural heritage, adapting local knowledge to modern sustainability practices [

23]. This study focuses on the potential to transform traditional rural villages into ecovillages, rather than establishing entirely new communities from scratch.

1.1. Literature Review and Research Gap

Some studies focus on poverty to transform traditional villages into sustainable communities. Sun et al. [

24] examined relative poverty in urban and rural China using data from 31 provinces and cities, applying the Social Poverty Line (SPL) index. The findings indicate that rural areas face significantly higher poverty rates than urban areas, exceeding 60% in some regions. Using a logit model, the study identified key factors influencing poverty, including education, government support, and financial policies. The results emphasize the need for region-specific poverty reduction strategies that address structural inequalities and promote sustainable economic development. Lee and Wang [

25] investigated how digital inclusive finance influences carbon intensity in 277 Chinese cities (2011–2017) using spatial econometric models. The findings revealed that digital finance reduces carbon intensity by promoting green technology, optimizing industrial structures, and shifting economic activities online. A spillover effect was observed, with the influence extending 350–400 km beyond individual cities. The Green Credit Policy 2013 further strengthened this effect, highlighting the role of financial policies in reducing emissions. The study underscores digital finance as a key tool for sustainable economic growth and low-carbon development.

Previous studies on ecovillage development have largely focused on intentional communities in Western contexts [

6,

26], with limited research on the transformation of traditional villages into sustainable ecovillages, which is particularly lacking in Turkey. Studies in Europe and North America have highlighted the role of intentional community governance [

27], while research in India and Senegal has explored policy-driven ecovillage transitions [

28].

While these studies contribute valuable insights, they often lack critical engagement with competing perspectives on the role of governance, local participation, and adaptability of sustainability frameworks. For example, Lockyer [

26], emphasizes the necessity of strong communal governance, while Singh et al. [

28] argue that state-led initiatives can be more effective in rural transformations. Additionally, some researchers question whether intentional ecovillage models can be successfully replicated in traditional villages without significant socio-economic restructuring [

29]. In addition, by selecting coastal, lowland, and mountain villages, we aimed to make evaluations regarding the differences between village typologies, unlike previous studies. These gaps necessitate a more nuanced examination of the conditions that enable or hinder ecovillage transitions.

Additionally, much of the existing literature focuses on ecological and economic factors, often overlooking social and spiritual dimensions, which play a crucial role in sustainability transitions [

16,

19]. The Community Sustainability Assessment (CSA) framework, developed by the GEN, provides a structured approach to assessing sustainability across ecological, social, and worldview dimensions [

7]. While widely used in intentional ecovillages, its application to existing villages remains mostly underexplored [

15]. The GEN is a network that was established to allow sustainable settlements (mostly ecovillages) worldwide to be informed about each other and exchange green methods. Over time, it also became an educational authority. Ecovillage Design Education (EDE) is the most well-known of this training. The need for a technique for ecovillages to measure their sustainability in terms of various dimensions at certain intervals was discussed, and the CSA began to take its first form. Later, this evaluation method was modified as much as possible to be applied to any village in any part of the world.

The CSA framework is a comprehensive self-assessment tool that enables communities to evaluate their sustainability efforts across three primary dimensions: ecological, social, and worldview.

Ecological Dimension: This aspect assesses environmental stewardship, resource management, renewable energy use, waste reduction strategies, and regenerative land-use practices. It emphasizes sustainable building techniques, local food systems, and biodiversity conservation.

Social Dimension: This category evaluates social cohesion, participatory decision making, inclusivity, education, health, and conflict resolution within a community. It highlights how social structures contribute to resilience and long-term sustainability.

Worldview Dimension: This focuses on cultural identity, values, shared vision, and personal development within the community, recognizing the importance of intangible aspects of sustainability. It includes elements like spirituality, mindfulness, and ethical leadership.

The CSA incorporates 21 themes and 900 indicators within three dimensions to provide a holistic and adaptable evaluation system. It has been widely applied across different regions, offering insights into how communities can transition towards sustainability based on local strengths and weaknesses. Despite its global applicability, there is limited research on its effectiveness in non-Western contexts, making this study an important contribution to its application in Turkey.

Antoh [

30] assessed the sustainability of Skouw Mabo Village in Papua, Indonesia, using the CSA method. Social (341) and spiritual (350) aspects scored higher than ecological aspects (248), indicating strong community cohesion but also environmental challenges. Issues like waste management, poor infrastructure, and inefficient water use highlight the need for sustainable practices. The study suggests integrating agroforestry, eco-tourism, and better governance to enhance sustainability. Strengthening local participation, education, and conservation efforts is essential for the village’s long-term resilience.

Widyarti and Arifin [

31] assessed the Inner Baduy community’s sustainability using the CSA method. With high scores in ecological (432), social (348), and spiritual (414) aspects, the Baduy exemplifies a sustainable lifestyle aligned with the ecovillage concept. Their strict land conservation, sustainable farming, and resource management support environmental preservation, while strong social cohesion and spiritual traditions reinforce cultural resilience. The study highlights the Baduy’s indigenous knowledge as a model for sustainable living and conservation.

Antoh et al. [

32] assessed Wiyantri Village’s sustainability in Papua, Indonesia, using the CSA method. Jalan Teratai 2 (1070) and Jalan Cendana (1025) showed strong sustainability, while Jalan Mawar (575) showed weak sustainability. Ecological sustainability benefits from responsible land use and water management, although some areas need improvement. Socio-cultural aspects, including social cohesion and economic resilience, vary, while the spiritual dimension remains strong. The study highlights the need for integrated environmental management and the preservation of traditional practices for long-term sustainability.

1.2. The Case of Turkey

In Turkey, ecovillage initiatives remain underdeveloped, often misconstrued as eco-tourism ventures focusing on economic returns rather than sustainability. This misalignment underscores the need for a nuanced understanding of the ecovillage concept and its potential to transform traditional rural settlements into sustainable communities [

33,

34]. As noted by Rashed [

4] and Singh et al. [

28], the integration of cultural and ecological dimensions is critical to achieving sustainability in rural contexts, particularly in regions experiencing rapid environmental degradation. Furthermore, Lockyer [

35] and Ulug et al. [

36] suggested that converting existing villages into ecovillages can be a faster solution for healing the world.

Studies on ecovillages in Turkey predominantly focus on literature reviews [

37,

38,

39]. Additionally, there are studies that evaluate certain ecovillages abroad [

40,

41,

42,

43]. Apart from these, Özmen et al. [

44] explores the potential of transforming İkiztaş Village into an eco-tourism destination by preserving its natural, architectural, and cultural heritage. Emphasizing sustainability and local participation, it highlights ecovillages as ideal settings for both tourism and conservation. The study identifies advantages such as small-scale tourism benefits and challenges like environmental risks. It concludes that successful eco-tourism development requires careful planning, infrastructure improvements, and active community involvement to balance cultural preservation and economic sustainability. Banoğlu and Yıldırım [

45] examined Pilarget (Ulukent), a rural settlement in Artvin, in the context of ecovillage principles. The study used Boverket’s 20 principles for ecovillages, a Swedish planning framework, to evaluate Pilarget’s suitability. Çakmak ve Göktuğ [

46] evaluated core villages in Kuşadası and Söke as potential ecovillages using eight main criteria and 92 sub-criteria, assessed through a five-point Likert scale. It identifies strengths such as eco-tourism potential and cultural heritage, while weaknesses include limited renewable energy use and lack of employment opportunities. The study suggests eco-friendly infrastructure, local participation, and economic strategies for sustainable development.

The ecovillage movement is witnessing a growing global presence; yet, Turkey, as a developing nation, has regrettably fallen behind in this paradigm shift towards sustainable living. Historically, there have been efforts, supported by various governmental ministries, aimed at the transformation of certain traditional villages into ecovillages within Turkey.

However, these state-supported ecovillage transformation initiatives have predominantly centered on enhancing the touristic appeal of these villages, thereby primarily addressing the economic dimension of sustainability. This narrow focus neglects the ecological, social, and cultural sustainability principles that are foundational to the true essence of ecovillages. For instance, in the case of the proposed transformation of Eskidoğanbey village in Aydın—a traditional Greek village characterized by its preserved architectural heritage—misguided strategies were implemented. This plan included the construction of a large parking facility for visitors, a motel, and a museum within the village boundaries. Furthermore, Kaşan [

47] reported that to circumvent legal and administrative challenges associated with the conversion of this village, located within the Dilek Peninsula National Park, measures were taken to excise the location from the national park’s jurisdiction.

Significant funding was allocated to the Hasankeyf Üçyol Ecovillage Project, wherein the designated authorities undertook visits to prominent global ecovillages such as Auroville for comparative examination. The project report articulated the geological suitability of the region for the cave-hotel concept, positing that such an approach could substantially increase visitor attraction and facilitate the village’s transformation into an ecovillage [

48]. Nonetheless, it has been noted that since 2015, no continued efforts have been made regarding this initiative.

Ecovillages ought to embody principles such as social solidarity, cultural integration, environmental harmony, and diversified economic activities. Transformations driven solely by economic interests stand in stark contrast to the foundational ethos of the ecovillage concept and consequently contribute to the failure of these projects. The mismanaged strategies observed in Turkey highlight a significant lack of methodological rigor in approaching this subject, which has subsequently served as a catalyst for Zeybek’s doctoral research. In addition, we point out why approaches that consider ecovillages only as an eco-tourism destination cannot be sustained.

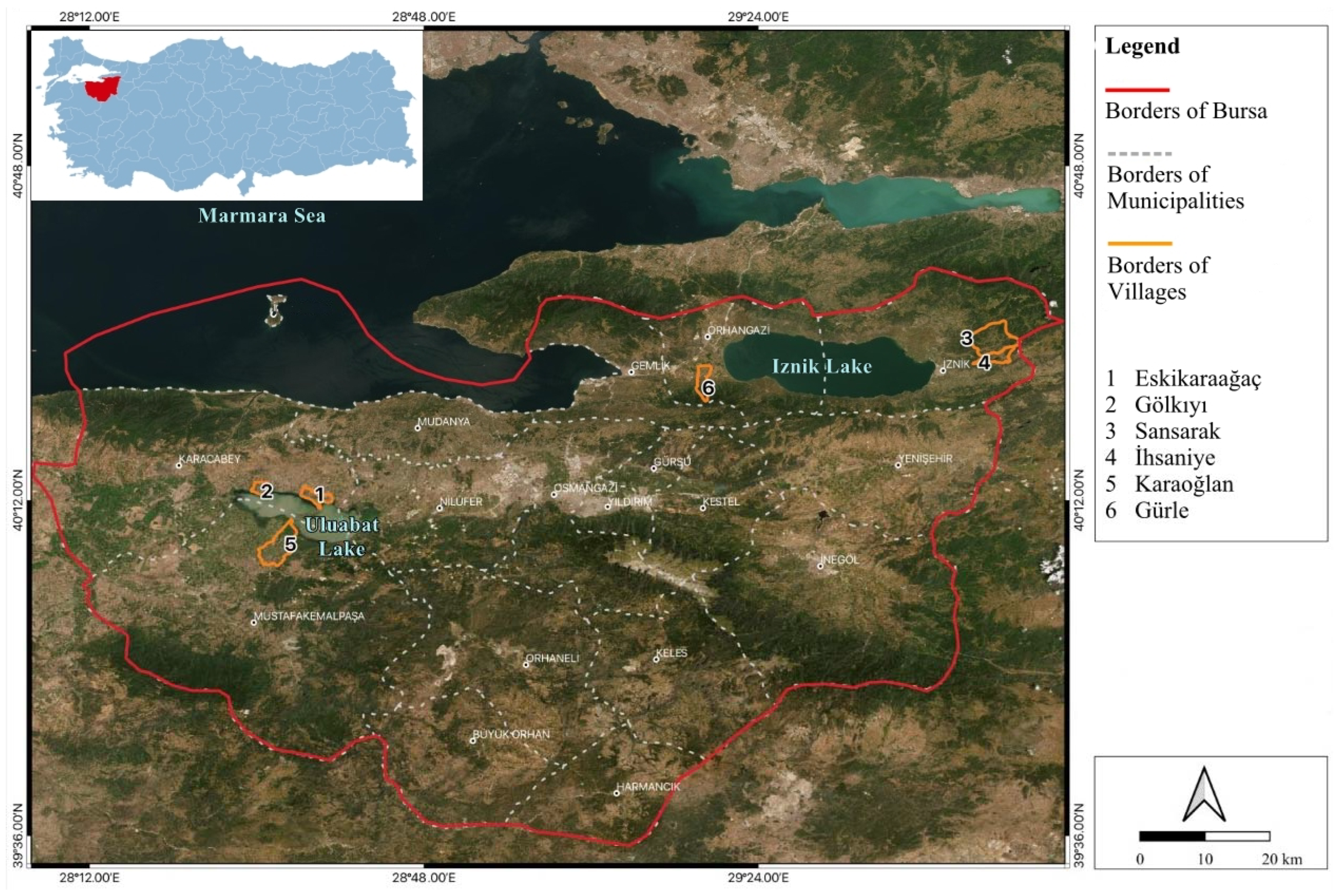

This study uses the CSA framework created by the GEN to assess the feasibility of turning six traditional villages in Bursa into ecovillages. The research attempts to uncover important strengths and shortcomings by evaluating these communities along ecological, social, and worldview aspects, providing helpful information for promoting sustainable rural development. The findings support global sustainability initiatives by showcasing the CSA framework’s versatility and applicability to many cultural and environmental situations. They also give community leaders, planners, and legislators a starting point for creating focused plans to improve Turkish villages’ ecological and socio-economic resilience.

In Turkey, no study has been conducted to assess existing settlements using a scoring system based on various dimensions, such as the CSA, to determine their potential for transformation into ecovillages. Moreover, existing transformation studies tend to perceive ecovillages merely as eco-tourism destinations rather than holistic sustainable settlements. To address this research gap and highlight the significance of sustainable settlements within the context of climate change, this study was designed. Accordingly, the research focuses on villages within Bursa, Turkey’s fourth-largest city, where urbanization and industrial pressures are particularly pronounced.

3. Results

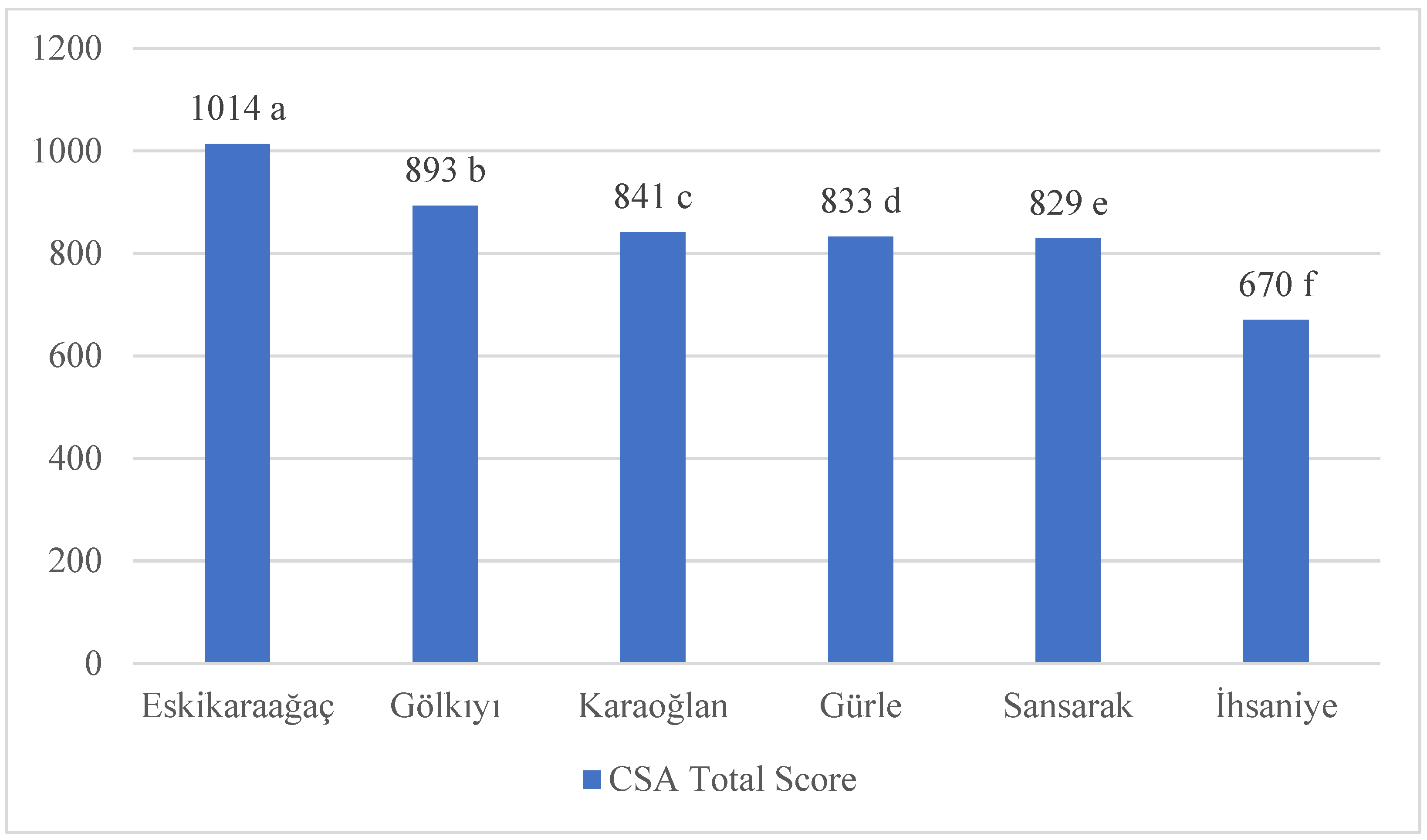

According to the analysis results, the total scores received by the villages within the scope of the Community Sustainability Assessment were significant at the

p ≤ 0.01 level, and the coastal villages received the highest total values. Accordingly, Eskikaraağaç received the highest score of 1014, followed by Gölkıyı, with a score of 893. İhsaniye received the lowest value of 670 (

Figure 2).

According to the Community Sustainability Assessment results, it was determined that different dimensions affect the villages and are level. Accordingly, while Eskikaraağaç village ranks first, with 260, 370, and 384 points in terms of ecological, social, and worldview dimensions, respectively, Sansarak village is almost at the same level as Eskikaraağaç village, especially in the ecological dimension, with 259 points (

Table 3).

Within the framework of the ecological dimension criteria, the comparison of villages revealed statistically significant differences at the

p ≤ 0.01 level. Accordingly, Eskikaraağaç village ranked first in the criterion of E1: Sense of Place—community location and scale; restoration and preservation of nature, with a score of 52. The same village also stood out in E6: Wastewater and water pollution management, with a score of 50, while Sansarak village gained attention for E2: Food Availability, Production and Distribution, also with a score of 50. In contrast, Karaoğlan village was found to have the lowest score, receiving only five points in the criterion of E6: Wastewater and Water Pollution Management. Additionally, Gürle village excelled in several criteria, including E3: Physical Infrastructure, Buildings, and Transportation—materials, methods, and designs, with a score of 46, E5: Water—sources, quality, and use patterns, with a score of 42, and E4: Consumption Patterns and Solid Waste Management, with a score of 41 (

Table 4).

In the comparison of villages within the framework of the social dimension criteria, statistically significant differences were observed at the

p ≤ 0.01 level. Accordingly, Eskikaraağaç village ranked first across several criteria, including S2: Communication—sharing of information and ideas, with a score of 58, S3: Networking Outreach and Services—resource exchange (internal/external), with a score of 48, S4: Social Sustainability—diversity and tolerance, decision making, and conflict resolution, with a score of 74, S6: Healthcare services, with a score of 60, and S7: Sustainable Economics—healthy local economy, with a score of 41. Gürle village stood out in the criterion of S1: Openness, Trust, and Safety; Communal Space, with a score of 60, while Karaoğlan village achieved the highest score of 43 in the criterion of S5: Education (

Table 5).

Significant differences were observed among the villages in terms of the worldview dimension criteria, with the differences being statistically significant at the

p ≤ 0.01 level. Eskikaraağaç village ranked highest in several criteria, including S2: Arts and Leisure, with a score of 30, W4: Community Glue, with 63 points, W5: Community Resilience, with 59 points, W6: A New Holographic and Circulatory Worldview, with 58 points, and W7: Peace and Global Consciousness, with 54 points. On the other hand, Karaoğlan village received the highest score in the criterion of W1: Cultural Sustainability, with 86 points, while Sansarak village scored the highest in W3: Spiritual Sustainability—rituals and celebrations and support for inner development and spiritual practices, with 51 points. Additionally, Gürle village recorded the lowest score, receiving only eight points in the criterion of W2: Arts and Leisure (

Table 6).

The results of this study provide a comprehensive evaluation of the sustainability potential of six selected villages in Bursa, Turkey, based on the CSA framework. The findings highlight variations in sustainability scores across ecological, social, and worldview dimensions, with significant differences between coastal, lowland, and mountain villages. The quantitative analysis of the CSA indicators, combined with qualitative insights from interviews and field observations, offers a nuanced understanding of the challenges and opportunities for ecovillage transformations in the region.

The CSA framework revealed that coastal villages (Eskikaraağaç and Gölkıyı) had the highest scores in overall sustainability, particularly in the ecological and social dimensions. These villages demonstrated strong communal governance, active environmental conservation efforts, and locally managed fisheries, reinforcing their potential for sustainable transformation. In contrast, mountain villages (Sansarak and İhsaniye) exhibited the lowest sustainability scores, mainly due to limited accessibility, infrastructural deficiencies, and economic constraints. The lowland villages (Karaoğlan and Gürle) ranked in between, showing moderate sustainability potential but facing challenges such as urbanization pressures and land-use conflicts.

The ecological assessment examined resource management, biodiversity conservation, and renewable energy use. The coastal villages performed well, benefiting from community-led fishing sustainability initiatives and water resource management. However, mountain villages struggled due to poor waste management systems and deforestation risks. A resident from Sansarak stated, “We have lost many of our traditional water sources due to modern land-use changes, and it is becoming harder to sustain agricultural productivity”. This statement reflects the urgent need for tailored ecological restoration strategies. Conversely, lowland villages experienced soil degradation due to intensive agricultural activities. The field observations revealed a significant lack of renewable energy infrastructure across all village types, with only 12% of surveyed households utilizing solar energy. These findings highlight the importance of integrating renewable energy policies into rural sustainability initiatives.

The social sustainability analysis indicates that coastal villages exhibited stronger community cohesion and governance participation than mountain villages. In addition, 78% of Eskikaraağaç residents actively participated in local governance discussions, compared to only 42% in Karaoğlan. Interviews confirmed that coastal villages had stronger networks for collective decision making, likely due to historical interdependence on fishing and tourism economies. However, this study revealed a lack of structured community organizations in some lowland and mountain villages, which limited their ability to initiate sustainability projects. One local leader from Gürle remarked, “We have no real platform to discuss sustainability; most decisions are still made by a few key families”. This underscores the need for inclusive participatory frameworks that empower residents in decision making.

The worldview dimension explored cultural values, traditional knowledge, and sustainability perceptions. The highest scores were recorded in Eskikaraağaç and Gölkıyı, where residents retained strong connections to traditional practices such as communal fishing, ecological rituals, and shared agricultural responsibilities. However, mountain villages showed lower scores, reflecting the gradual erosion of indigenous knowledge and migration-driven cultural shifts.

A key takeaway from the results is the necessity for localized sustainability strategies that account for geographic, economic, and socio-cultural diversities. The disparities in governance engagement, resource access, and social capital between different village types reinforce the need for customized policy interventions rather than a one-size-fits-all approach.

4. Discussion

Important insights into the elements that can promote successful transitions to ecovillages were obtained by applying the CSA framework to six Bursa villages. In terms of ecological, social, and worldview elements, coastal villages such as Gölkıyı and Eskikaraağaç have continuously emerged as leaders. Strong ties to the community and easy access to natural resources are the sources of their benefits. Eskikaraağaç set itself apart in “Sense of Place” and “Wastewater Management”, demonstrating its dedication to sustainable practices and ecological resilience. On the other hand, mountain communities like İhsaniye had significant difficulties, especially with regard to infrastructure and resource management. Coastal villages exhibit remarkable spiritual and cultural strength, but mountain villages’ ecological and economic viability is hampered by their remote location and poor infrastructure. In order to steer future attempts toward balanced and significant growth, it is imperative that these contrasts be emphasized.

Social cohesion was discovered to have a considerable impact on sustainability potential. Two lowland and coastal settlements that demonstrated strong networks of communication, trust, and resource sharing are Karaoğlan and Eskikaraağaç. However, disparities in access to healthcare and education persisted, especially in mountainous regions where poor infrastructure hampered social development. The worldview component clarified the importance of cultural and spiritual activities that continued in every village. Low levels of engagement in modern arts and leisure activities, however, suggested a possible area for improvement and underscored the need to modernize while maintaining ancient customs.

The findings emphasize the critical role of geographic and cultural factors in shaping sustainability outcomes. Coastal villages excelled due to their ecological advantages and socio-economic opportunities, aligning with global studies that highlight the importance of resource accessibility and community cohesion in sustainability transitions. For example, research on Iceland’s Solheimar Ecovillage underscores similar patterns, where ecological resilience is bolstered by natural resources and strong community ties [

56]. Similarly, studies in rural India and Senegal have shown that geographic proximity to resources such as water bodies significantly influences the success of sustainable development projects [

15,

50].

4.1. Results Enriched with Qualitative Data

This study revealed key sustainability challenges and strengths in each village through in-depth interviews and field observations, drawing on insights from prior research. For example, in Eskikaraağaç (coastal village), villagers highlighted a strong communal culture and traditional fishing practices that promote sustainable food systems. One interviewee noted: “We have always fished responsibly. If we take too much, there won’t be any left for our children”. Eskikaraağaç, declared a European Stork Village by EuroNATUR in 2011 [

57], is a village known for its extremely close ties with storks. A documentary about the life of a stork named Yaren in the village won the best documentary award at the 2019 Prague Film Festival.

Similarly, in Gölkıyı (coastal village), community-led reforestation efforts were documented through interviews, demonstrating a bottom-up approach to environmental stewardship. As one villager remarked: “We plant trees every year because we know our land depends on them”.

Karaoğlan (lowland village), despite being the largest and most vibrant village in this research, has been displaying a negative attitude towards state policies since Lake Uluabat was protected under the Ramsar Convention in 1998 due to its rich wetland assets. Although Karaoğlan is located outside the boundaries of the protected area, many agricultural areas belonging to the dwellers remain within the boundaries of the protected area. The villagers, who drew attention to their highly fertile lands, say, “We were the richest village in Bursa before this convention”. Since the villagers advanced their agricultural activities to the shores of the lake, they were removed from the wetland by the experts. They claim that they became poorer for this reason. It also has been stated that due to the boron mine operating near the village, there has been a decrease in the yield of agricultural products since the mine was opened.

Gürle (lowland village), a significant settlement since the early Ottoman period, is a village that draws attention due to its multi-story wooden houses and is engaged in olive cultivation. The residents of this village, which has two fountains, a bathhouse, and a mosque that are all approximately 700 years old, are rapidly emigrating due to socio-economic reasons. It has been observed that mostly older adults live in the village. For this reason, there is not even a grocery store in the village.

In Sansarak (mountain village), oral histories captured from elderly residents revealed that traditional water conservation practices, such as communal irrigation systems, has been lost over time. This was echoed by a local elder: “In my father’s time, we shared water equally, but now, with modern pumps, some take more than others”.

The smallest and most difficult-to-reach village in winter that was examined within the scope of the research, İhsaniye (mountain village), cannot benefit sufficiently from infrastructure services due to its location on a very steep terrain with the highest altitude in Bursa. Located in a strong wind corridor, the village has been facing a serious erosion problem for years. Despite the village’s magnificent view and well-preserved architectural heritage, the villagers, who mainly engage in animal husbandry, are gradually leaving the village and settling in the city. Even the village chief (muhtar) does not live in the town.

4.2. Evaluation of Turkey’s Position

Cultural and spiritual resilience emerged as strengths across all village types, reflecting Turkey’s rich rural traditions and collective identities. These findings align with research on Scandinavian and Italian ecovillages, where cultural heritage and shared values are crucial to effective sustainability initiatives—however, gaps in ecological infrastructure and modern cultural participation present opportunities for targeted solutions. Enhancing natural systems in mountain and lowland villages and promoting participation in the arts and recreational activities could build on existing strengths while addressing current weaknesses.

This study has wide-ranging policy consequences. Creating a national framework to assist in ecovillage activities in Turkey could provide a systematic method to grow these efforts. This framework can include funding for ecological infrastructure, sustainability training programs, and periodical progress evaluations. Furthermore, incorporating digital technologies and participatory approaches into sustainability assessments may improve data integrity and community involvement, resulting in more inclusive and effective policies.

The CSA framework’s adaptability to multiple cultural and geographic situations makes these discoveries scalable. By including specific criteria, the framework can be applied to villages worldwide, allowing for comparative research and sharing best practices. For example, Senegal’s ambition to convert 14,000 communities into ecovillages indicates the viability of large-scale implementation when backed by firm national policies and international cooperation [

50].

Adapting the CSA framework to reflect the unique cultural and environmental contexts of Turkish villages is vital for accurate and effective sustainability assessments. Incorporating local cultural practices and traditions is a key step in this process. Documenting traditional crafts, festivals, and communal activities can help evaluate cultural vitality, which is critical for fostering community resilience. Indicators assessing participation in these practices can be integrated into the CSA to reflect the socio-cultural dynamics of Turkish villages. The CSA is also an extremely effective inventory assessment for villages where no research has been conducted.

It is also important to highlight neighborhood networks and social cohesion. Metrics that evaluate neighborhood links, family ties, and local governance models—essential to maintaining communal life—can be added to the CSA. Another important element may be traditional ecological knowledge about natural resource use, agriculture, and water management, representing the adaptive techniques honed over generations.

Metrics of economic sustainability should be adjusted to account for the artisanal, agricultural, and animal husbandry-based livelihoods that are common in Turkish villages. To make sure these economic activities are in line with sustainability objectives, the CSA should assess their resilience and diversification. To assess inclusivity and efficacy, the assessment must also take into account governance institutions, such as the functions of councils and village chiefs (muhtars).

On the other hand, the fact that Turkey does not have a national database on ecovillages makes it difficult for individual or communal initiatives to be informed about each other. Developing some pilot projects supported by the government could be an important educational asset for determining what to consider when converting an existing village into an ecovillage.

5. Conclusions

This study illustrates how the CSA framework may turn Bursa’s traditional villages into ecovillages. The findings show notable differences in the sustainability potential of different types of villages, with coastal villages continuously outperforming their counterparts in the lowlands and mountains. These results highlight the importance of social, cultural, and regional elements in determining sustainability outcomes.

The high levels of cultural and spiritual resilience underscore the deep-rooted traditions and strong community ties in Turkish villages, providing a solid foundation for sustainability transitions. However, the shortcomings in ecological infrastructure and limited participation in modern cultural activities, such as the arts and recreation, indicate areas requiring targeted intervention. These insights align with global studies on sustainable rural development, emphasizing the importance of integrating traditional knowledge with contemporary practices for holistic sustainability.

This study underscores the pressing need for a national framework in Turkey to support ecovillage initiatives. Establishing a dedicated directorate for sustainable settlement projects within relevant ministries would enhance the organization of efforts to develop and promote ecovillages. Such a framework would facilitate more efficient resource allocation, strengthen capacity building, and foster the sharing of successful practices. Furthermore, adapting the CSA framework to align with the distinct cultural and environmental characteristics of Turkish villages would enable more accurate evaluations and effective interventions.

The results indicate that while certain villages exhibit strong sustainability potential, others face significant ecological and socio-economic barriers. Key findings emphasize the importance of community-driven governance models, resource management improvements, and targeted sustainability education programs. Future efforts should focus on integrating local knowledge with adaptive sustainability policies and ensuring rural villages can transition toward ecovillages while maintaining their cultural identity and economic resilience.

This study also carries broader significance for global sustainability initiatives. By showcasing the flexibility of the CSA framework, this research contributes to the expanding knowledge of sustainable rural development. It provides a model that can be replicated to evaluate and improve sustainability in various settings. The transformation of traditional villages into ecovillages in Bursa can guide comparable projects worldwide, especially in areas dealing with environmental decline and social issues.

Future research should expand on this study by including a wider variety of villages from different climate zones and ethnic backgrounds, as well as incorporating longer-term analyses to understand the lasting effects of ecovillage transitions. Additionally, investigating how digital technologies and community-driven approaches can be integrated into sustainability assessments might lead to innovative solutions for current challenges.

In summary, this study showcases the potential of ecovillage transitions to address environmental harm, social inequality, and cultural loss. By combining traditional practices with modern sustainability concepts, ecovillages pave the way for resilient and inclusive rural communities, contributing to both local and global sustainability goals.

The potential of a village to become an ecovillage requires a multidisciplinary approach. For example, if a settlement with strong ecological indicators is experiencing emigration, this situation should be evaluated by experts in sociology, anthropology, economics, psychology, and other relevant fields. Therefore, a team integrating experts from different disciplines should be established to develop a method, such as the CSA, for measuring sustainability in a country, region, or area.

Limitations

It is crucial to recognize the limitations of this study, even though it offers insightful information about the possibility of converting Bursa’s traditional villages into ecovillages. This study focused on six towns that represent mountain, lowland, and coastal typologies. While these towns were carefully selected, the small sample size limits the generalizability of the results. Expanding this study to include a wider variety of communities from different geographical regions of Turkey would provide more comprehensive findings.

Bursa has long been an essential center of Anatolia as it was the first capital of the Ottoman Empire. Consequently, the region has villages of different ethnic origins and sects, each with unique cultural characteristics due to its long history. However, the ethnographic and sectarian differences of the villages were not considered within the research scope.

Although the scope of the CSA is broad, specific indicators may fail to capture the dense cultural background of these communities, highlighting the need for further refinement and contextualization. Another limitation is this study’s chronological scope. While data were collected over three years and controlled for seasonal variation, this study did not examine long-term changes in sustainable behaviors or the impact of external factors, such as economic shifts, policy changes, or climate variability. Future studies spanning a longer period are needed to understand how these variables affect sustainability trajectories. Re-implementing the CSA in the same villages five years after this study was completed is among the planned future research.

Additionally, some subjectivity in data collection and interpretation was inevitable, despite efforts to standardize the methods. The variability was introduced through reliance on observations and interviews. Future research could incorporate mechanisms to improve inter-rater reliability, reducing subjectivity and increasing reproducibility.

Lastly, while this study highlights weaknesses in ecological and social infrastructure, it does not thoroughly analyze the technical and economic feasibility of addressing these issues. Feasibility studies and comprehensive cost-benefit analyses will provide practical solutions. Furthermore, the lack of benchmarking against global ecovillage initiatives limits this study’s ability to identify best practices and conduct more thorough comparisons. Addressing these limitations will strengthen future research and enhance the success of ecovillage initiatives in Turkey and beyond.

The educational background of village residents, predominantly primary school graduates, made it challenging to collect reliable data on certain CSA parameters, such as peace and global consciousness. Data were obtained by simplifying these parameters, but future studies should revise these metrics to make them more accessible and indirectly enriched with relevant examples.