Italian Consumers’ Perceptions and Understanding of the Concepts of Food Sustainability, Authenticity and Food Fraud/Risk

Abstract

1. Introduction

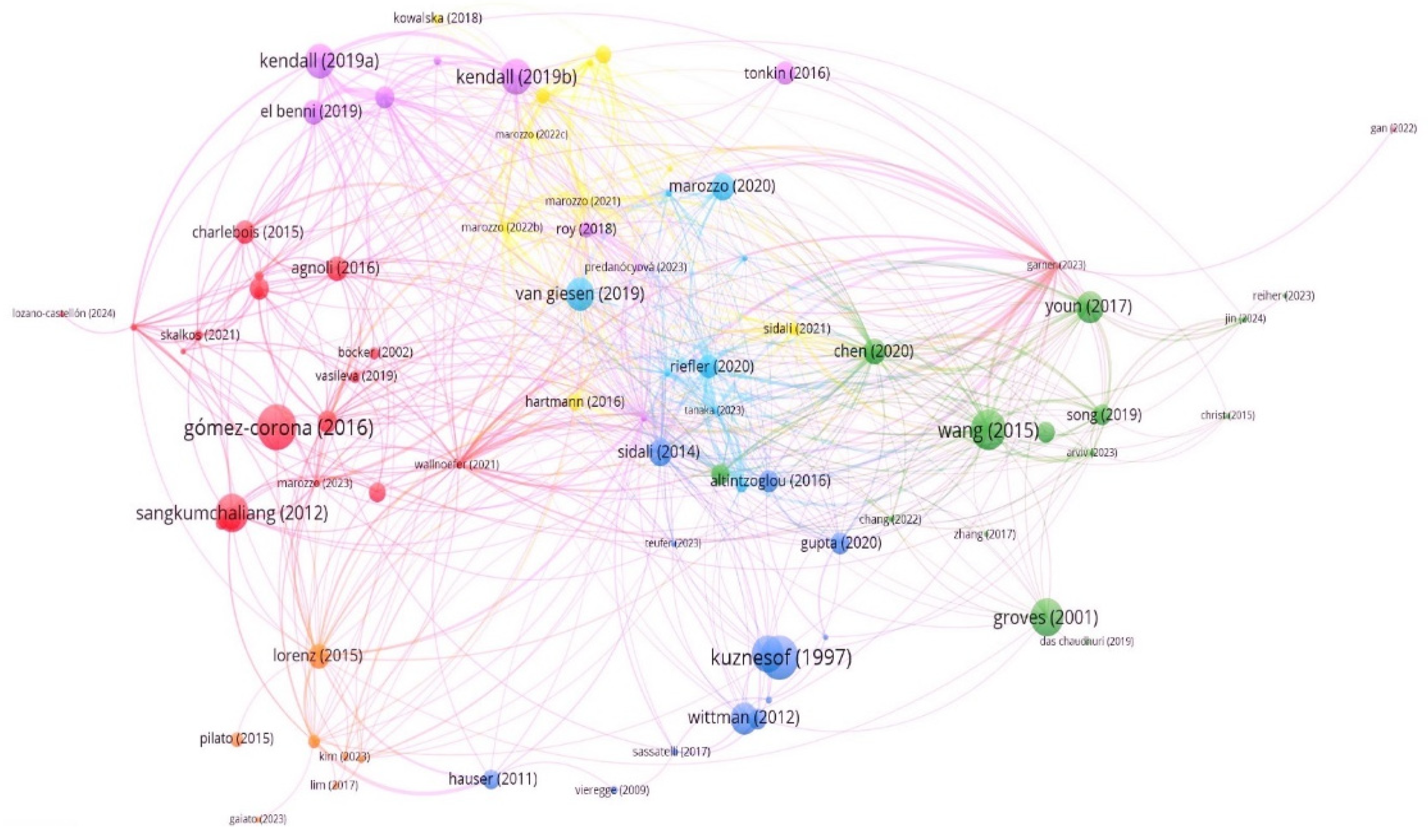

2. Theoretical Framework and Research Questions Formulation

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Questionnaire Design

3.2. Survey

3.3. Methods

4. Results

4.1. Summary Demographics

4.2. Identification of the Important Socio-Demographic Determinants

4.3. Identification of Well-Established “Homogeneous” Consumer Groups

4.3.1. Cluster 1: Young, Single and Uninformed Consumers

4.3.2. Cluster 2: Married and Conscious Consumers

4.3.3. Cluster 3: Educated and Informed Consumers

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contribution

5.2. Practical and Policy Implications

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Théolier, J.; Barrere, V.; Charlebois, S.; Godefroy, S.B. Risk analysis approach applied to consumers’ behaviour toward fraud in food products. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 107, 480–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spink, J.; Moyer, D.C. Defining the public health threat of food fraud. J. Food Sci. 2011, 76, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliot, C. Elliott Review Into the Integrity and Assurance of Food Supply Networks, Final Report. A National Food Crime Prevention Framework; UK Government Publication: London, UK, 2014; pp. 1–145.

- Johnson, R. Food fraud and ‘Economically motivated adulteration’ of food and food ingredients. Congr. Res. Serv. CSR Rep. 2014, 43358, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Soon-Sinclair, J.M.; Ha, T.M.; Vanany, I.; Limon, M.R.; Sirichokchatchawan, W.; Wahab, I.R.A.; Hamdan, R.H.; Jamaludin, M.H. Consumers’ perceptions of food fraud in selected Southeast Asian countries: A cross sectional study. Food Secur. 2024, 16, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, K.; Dean, M.; Haughey, S.; Elliott, C. A comprehensive review of food fraud terminologies and food fraud mitigation guides. Food Control 2021, 120, 107516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Europol. Intellectual Property Crime Threat Assessment. 2022. Available online: https://www.europol.europa.eu/publications-events/publications/intellectual-property-crime-threat-assessment-2022 (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Gossner, C.M.E.; Schlundt, J.; Ben Embarek, P.; Hird, S.; Lo-Fo-Wong, D.; Beltran, J.J.O.; Teoh, K.N.; Tritscher, A. The melamine incident: Implications for international food and feed safety. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009, 117, 1803–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, F. Horsemeat Scandal: The Essential Guide. The Guardian. 2013. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2013/feb/15/horsemeat-scandal-the-essential-guide (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- Jabeur, H.; Zribi, A.; Makni, J.; Rebai, A.; Abdelhedi, R.; Bouaziz, M. Detection of Chemlali extra-virgin olive oil adulteration mixed with soybean oil, corn oil, and sunflower oil by using GC and HPLC. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 4893–4904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, J.C.; Spink, J.; Lipp, M. Development and application of a database of food ingredient fraud and economically motivated adulteration from 1980 to 2010. J. Food Sci. 2012, 77, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.J.; Burns, M.; Burns, D.T. Horse meat in beef products-species substitution. J. Assoc. Public Anal. 2013, 41, 67–106. [Google Scholar]

- De Jonge, J.; Frewer, L.; Van Trijp, H.; Jan Renes, R.; De Wit, W.; Timmers, J. Monitoring consumer confidence in food safety: An exploratory study. Brit. Food J. 2004, 106, 837–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Zhang, A.; van Klinken, R.D.; Schrobback, P.; Muller, J.M. Consumer Trust in Food and the Food System: A Critical Review. Foods 2021, 10, 2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlebois, S.; Juhasz, M.; Foti, L.; Chamberlain, S. Food fraud and risk perception: Awareness in Canada and projected trust on risk-mitigating agents. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2017, 29, 260–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W. The effects of different types of trust on consumer perceptions of food safety: An empirical study of consumers in Beijing Municipality, China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2013, 5, 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omari, R.; Ruivenkamp, G.T.; Tetteh, E.K. Consumers’ trust in government institutions and their perception and concern about safety and healthiness of fast food. J. Trust Res. 2017, 7, 170–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouranta, N.; Psomas, E.; Vouzas, F. The effect of service recovery on customer loyalty: The role of perceived food safety. Int. J. Qual. Sci. 2019, 11, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Books, C.; Parr, L.; Smith, M.J.; Buchanan, D.; Sniock, D.; Hebishy, E. A review of food fraud and food authenticity across the food supply chain, with an examination of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and Brexit on food industry. Food Control 2021, 130, 108171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, C.; Sacchi, G.; Carfora, V. Resilience effects in food consumption behaviour at the time of COVID-19: Perspectives from Italy. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCallum, C.S.; Cerroni, S.; Derbyshire, D.; Hutchinson, W.G.; Nayga, R.M., Jr. Consumers’ responses to food fraud risks: An economic experiment. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2022, 49, 942–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahyono, E.D. Instagram adoption for local food transactions: A research framework. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 187, 122215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baas, J.; Schotten, M.; Plume, A.; Côté, G.; Karimi, R. Scopus as a curated, high-quality bibliometric data source for academic research in quantitative science studies. Quant. Sci. Stud. 2020, 1, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Castellón, J.; Laveriano-Santos, E.P.; Abuhabib, M.M.; Pozzoli, C.; Pérez, M.; Vallverdú-Queralt, A.; Lamuela-Raventós, R. Proven traceability strategies using chemometrics for organic food authenticity. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 147, 104430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, C.R.; Mourão, A.; Mendonça, V.; Correia, R. An ICT Integrated Model for Traceability, Promotion and Valorization of Regional Food Products. In Proceedings of the 2022 17th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (CISTI), Madrid, Spain, 22–25 June 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Castellini, G.; Sesini, G.; Iannello, P.; Lombi, L.; Lozza, E.; Lucini, L.; Graffigna, G. “Omics” technologies for the certification of organic vegetables: Consumers’ orientation in Italy and the main determinants of their acceptance. Food Control 2022, 141, 109209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arviv, B.; Shani, A.; Poria, Y. Delicious–but is it authentic: Consumer perceptions of ethnic food and ethnic restaurants. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2023. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiher, C. Negotiating authenticity: Berlin’s Japanese food producers and the vegan/vegetarian consumer. Food Cult. Soc. 2023, 26, 1056–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.Y.; Hung, S.F.; Tang, S. Seek common ground local culture while reserving difference: Exploring types of souvenir attributes by Ethnic Chinese people. Tour. Stud. 2022, 22, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teufer, B.; Waiguny, M.K.; Grabner-Kräuter, S. Consumer perceptions of sustainability labels for alternative food networks. Balt. J. Manag. 2023, 18, 493–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Sánchez, H.Y.; Espinoza-Ortega, A.; Sánchez-Vega, L.P.; Moctezuma Pérez, S.; Cervantes-Escoto, F. The perceived authenticity in food among sociological generations: The case of cheeses in Mexico. Brit. Food J. 2024, 126, 1325–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marozzo, V.; Meleddu, M.; Abbate, T. Sustainability and authenticity: Are they food risk relievers during the COVID-19 pandemic? Brit. Food J. 2022, 124, 4234–4249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Predanócyová, K.; Šedík, P.; Horská, E. Exploring consumer behavior and attitudes toward healthy food in Slovakia. Brit. Food J. 2023, 125, 2053–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matiringe-Tshiangala, T.; Nhedzi, A. Does the use of cause-related marketing in fast food restaurants lead to different consumer perceptions? Communitas 2022, 27, 85–105. [Google Scholar]

- Gaiato, G.; Ardigó, C.M.; Limberger, P.F. Animal Welfare Certification Seal and the Effect on Brand Equity: Consumer Perspective of Chicken Commodity. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2023, 29, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.J.; Kumar, A. Analyzing the cultural contradictions of authenticity: Theoretical and managerial insights from the market logic of conscious capitalism. J. Mark. 2022, 86, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, B.; Hollenbeck, C.R. The role of natural scarcity in creating impressions of authenticity at the Farmers’ market. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 167, 114171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Luo, J. Stability Extension of Food Culture Space: A Case Study of Consumer Space Practice Before and After COVID-19 Epidemic in Wuhan Food Markets. In COVID-19 and a World of Ad Hoc Geographies; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1563–1588. [Google Scholar]

- Onyeaka, H.; Ukwuru, M.; Anumudu, C.; Anyogu, A. Food fraud in insecure times: Challenges and opportunities for reducing food fraud in Africa. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 125, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, M.J.; García-Díez, J.; de Almeida, J.M.; Saraiva, C. Consumer knowledge about food labeling and fraud. Foods 2021, 10, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djekic, I.; Smigic, N. Consumer Perception of Food Fraud in Serbia and Montenegro. Foods 2023, 13, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guntzburger, Y.; Théolier, J.; Barrere, V.; Peignier, I.; Godefroy, S.; de Marcellis-Warin, N. Food industry perceptions and actions towards food fraud: Insights from a pan-Canadian study. Food Control 2020, 113, 107182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurica, K.; Brčić Karačonji, I.; Lasić, D.; Bursać Kovačević, D.; Putnik, P. Unauthorized food manipulation as a criminal offense: Food authenticity, legal frameworks, analytical tools and cases. Foods 2021, 10, 2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vågsholm, I.; Belluco, S.; Bonardi, S.; Hansen, F.; Elias, T.; Roasto, M.; Blagojevic, B. Health based animal and meat safety cooperative communities. Food Control 2023, 154, 110016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlebois, S.; Schwab, A.; Henn, R.; Huck, C.W. Food fraud: An exploratory study for measuring consumer perception towards mislabelled food products and influence on self-authentication intentions. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayga, R.M., Jr. Nutrition knowledge, gender, and food label use. J. Consum. Aff. 2000, 34, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Panchal, P. Extent of awareness and food adulteration detection in selected food items purchased by home makers. Pak. J. Nutr. 2009, 8, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.J.; Sousa, I.; Moura, A.P.; Teixeira, J.A.; Cunha, L.M. Food Fraud Conceptualization: An exploratory study with Portuguese consumers. J. Food Prot. 2024, 87, 100301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorente-Mento, J.M.; Valverde, J.M.; Serrano, M.; Pretel, M.T. Fresh-Cut Salads: Consumer Acceptance and Quality Parameter Evolution during Storage in Domestic Refrigerators. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaglia, S.; Borra, D.; Peano, C.; Sottile, F.; Merlino, V.M. Consumer preference heterogeneity evaluation in fruit and vegetable purchasing decisions using the best-worst approach. Foods 2019, 8, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Power, T.G.; Johnson, S.L.; Beck, A.D.; Martinez, A.D.; Hughes, S.O. The Food Parenting Inventory: Factor structure, reliability, and validity in a low-income, Latina sample. Appetite 2019, 134, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Tal, S.M.S. Modelling information asymmetry mitigation through food traceability systems using partial least squares. Electron. J. Appl. Stat. 2012, 5, 237–255. [Google Scholar]

- Berner-Rodorede, A.; Bärnighausen, T.; Eyal, N.; Sarker, M.; Hossain, P.; Leshabari, M.; Metta, E.; Mmbaga, E.; Wikler, D.; McMahon, S.A. “Thought provoking’, ‘interactive’, and ‘more like a peer talk’: Testing the deliberative interview style in Germany. SSM Qual. Res. Health 2021, 1, 100007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gram, M.; Hohnen, P.; Pedersen, H.D. You can’t use this, and you mustn’t do that’: A qualitative study of non-consumption practices among Danish pregnant women and new mothers. J. Consum. Cult. 2017, 17, 433–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquier, E.F.; Gatrell, A.; Bingley, A. We don’t snack: Attitudes and perceptions about eating in-between meals amongst caregivers of young children. Appetite 2017, 108, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, B.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Li, Q.; Tang, S.; Xiao, Y.; Wu, J. An updated estimation of the risk of transmission of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCov). Infect. Dis. Model. 2020, 5, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jolliffe, I.T.; Cadima, J. Principal component analysis: A review and recent developments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. Med. 2016, 374, 20150202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izenman, A.J. Modern Multivariate Statistical Techniques; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Noori, R.; Sabahi, M.S.; Karbassi, A.R.; Baghvand, A.; Zadeh, H.T. Multivariate statistical analysis of surface water quality based on correlations and variations in the data set. Desalination 2010, 260, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, J.H. Hierarchical Grouping to Optimize an Objective Function. J. Am. Stat. Ass. 1963, 58, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streiner, D.L. Figuring out factors: The use and misuse of factor analysis. Can. J. Psychiatry 1994, 39, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleine, P. An Easy Guide to Factor Analysis; Taylor and Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- De Irala-Estévez, J.; Groth, M.; Johansson, L.; Oltersdorf, U.; Prättälä, R.; Martínez-González, M.A. A Systematic Review of Socio-Economic Differences in Food Habits in Europe: Consumption of Fruit and Vegetables. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 54, 706–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, K.G.; Aachmann, K. Consumer reactions to the use of EU quality labels on food products: A review of the literature. Food Control 2016, 59, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, L. Trust in food in the age of mad cow disease: A comparative study of consumers’ evaluation of food safety in Belgium, britain and Norway. Appetite 2004, 42, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanelli, R.M.; Romagnoli, L. Annual food waste per capita as influenced by geographical variations. Riv. Studi Sulla Sostenibilità 2019, 1, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieger, J.; Weible, D.; Anders, S. Why some consumers don’t care: Heterogeneity in household responses to a food scandal. Appetite 2017, 113, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, M.; Henson, S. Perceived risk and risk reduction strategies in the choice of beef by Irish consumers. Food Qual. Prefer. 2005, 16, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savelli, E.; Murmura, F.; Liberatore, L.; Casolani, N.; Bravi, L. Food habits and attitudes towards food quality among young students. Int. J. Qual. Sci. 2017, 9, 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhartanto, D.; Dean, D.; Farhani, I. E-grocery service loyalty: Integrating food quality, e-grocery quality and relationship quality (young customers’ experience with local food). J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2024, 16, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament. Draft Report on the Food Crisis, Fraud in the Food Chain and the Control Thereof (2013/2091(INI)). 2013. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/A-7-2013-0434_EN.html (accessed on 25 November 2023).

- Boatemaa, S.; Barney, M.K.; Drimie, S.; Harper, J.; Korstend, L.; Pereira, L. Awakening from the listeriosis crisis: Food safety challenges, practices and governance in the food retail sector in South Africa. Food Control 2019, 104, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Type | Coding |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Registry | (Male = 0; Female = 1) |

| Age group | Registry | (18–24 = 1; 25–45 = 2; 46–60 = 3; >60 = 4) |

| Marital status | Registry | Single = 1; Married = 2 |

| Presence of children | Registry | (No = 0; Yes = 1) |

| Education | Registry | (Primary school = 1; Secondary school = 2; University Degree = 3; Professional qualification = 4) |

| Household members | Register | 1 person = 1; 2 persons = 3; 3 persons = 3; 4 persons = 4; More than 4 = 5 |

| Occupational status | Registry | (Student = 1; Housemaker = 2; Employee = 3; Self-employed = 4; Temporary worker = 5; Freelancer = 6; Pensioner = 7; Inactive = 8; Unemployed = 9) |

| Annual net income (€) | Registry | (No income = 0; 0–5000 = 1 5001–10,000 = 2; 10,001–15,000 = 3 15,000–25,000 = 4; >25,000 = 5) |

| Residence | (Urban = 0; Rural = 1) | |

| (Q1) When you buy food, how do you usually behave? | Consumer choice and preference | (I tend to buy the same products = 1; I usually change = 2; I try to vary the consumption of food, also based on offers = 3) |

| (Q2) When you buy a food product, what do you focus more on? | Consumer choice and preference | (Date of packaging = 1; Expiry date = 2; Ingredient = 3; Place of origin = 4; Weight = 5; Price = 6; Nutritional value = 7) |

| (Q3) Where do you usually buy food? | Consumer choice and preference | (Local store = 1; Supermarket = 2; Discount = 3; Certified organic stores = 3; E-Commerce = 4; Points of sale chosen by parents = 5) |

| (Q4) Did the lockdown (due to the spread of COVID-19) affect the way you purchased food? | Consumer choice and preference | (No = 0; Yes = 1) |

| (Q5) Which of the following certifications do you know? | Food certification and labelling | (PGI = 1; PDO = 2; Biological = 3; DOC = 4; DOCG = 5; UTZ = 6; Fair-trade = 7; I am aware of all the certifications mentioned = 8; I am not aware of the certification acronyms mentioned = 9) |

| (Q6) Do you generally buy certified food? | Food certification and labelling | (No = 1; Yes = 2; Only for some products = 3) |

| (Q7) When buying a food product, do you usually view the labels on the packaging? | Food certification and labelling | (No = 0; Yes = 1) |

| (Q8) Which of the following alternatives gives the exact name “food fraud of a product”? | Knowledge and awareness of agri-food fraud. | (Diversity of origin = 1; Deformity of quality and quantity of products = 3; None of the previous = 3) |

| (Q9) Are you afraid to buy and/or consume, without your knowledge, a fraudulent food product? | Knowledge and awareness of agri-food fraud. | (No = 0; Yes = 1) |

| Characteristics | Absolute Value | % of Respondent |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 127 | 38.7 |

| Female | 201 | 61.3 |

| Age group | ||

| 18–24 | 133 | 40.5 |

| 25–45 | 95 | 29.0 |

| 46–60 | 80 | 24.4 |

| >60 | 20 | 6.1 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 121 | 36.9 |

| Married | 196 | 59.8 |

| Presence of children | ||

| No | 141 | 43.0 |

| Yes | 187 | 57.0 |

| Education | ||

| Primary school | 92 | 28.0 |

| Secondary school | 110 | 33.5 |

| University Degree | 104 | 31.7 |

| Professional qualification | 22 | 6.7 |

| Household members | ||

| 1 person | 132 | 40.2 |

| 2 person | 83 | 25.3 |

| 3 person | 43 | 13.1 |

| 4 person | 55 | 16.8 |

| More than 4 | 15 | 4.6 |

| Occupational status | ||

| Student | 114 | 34.8 |

| Housemaker | 49 | 14.9 |

| Employee | 109 | 33.2 |

| Self-employed | 15 | 4.6 |

| Temporary worker | 8 | 2.4 |

| Freelancer | 2 | 0.6 |

| Pensioner | 19 | 5.8 |

| Inactive | 8 | 2.4 |

| Unemployed | 2 | 0.6 |

| Annual net income (€) | ||

| No income | 146 | 44.5 |

| 0–5000 | 37 | 11.3 |

| 5001–10,000 | 20 | 6.1 |

| 10,001–15,000 | 29 | 8.8 |

| 15,001–25,000 | 49 | 14.9 |

| >25,000 | 47 | 14.3 |

| Residence | ||

| Urban | 195 | 59.5 |

| Rural | 133 | 40.5 |

| Total | 328 | 100 |

| PCs | Eigenvalue | Difference | Variance Proportion | Cumulative Variance Proportion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC1 | 3.94 | 2.65 | 0.22 | 0.22 |

| PC2 | 1.28 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.29 |

| PC3 | 1.25 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.36 |

| PC4 | 1.21 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.43 |

| PC5 | 1.14 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.49 |

| PC6 | 1.10 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.55 |

| PC7 | 1.07 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.61 |

| PC8 | 1.01 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.67 |

| Variables | PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | PC4 | PC5 | PC6 | PC7 | PC8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | −0.04 | −0.18 | 0.44 | −0.07 | 0.19 | 0.42 | 0.18 | 0.03 |

| Age | 0.43 | −0.04 | −0.10 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.04 | −0.02 |

| Marital status | 0.49 | −0.04 | −0.05 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.03 |

| Presence of children | 0.47 | −0.01 | −0.07 | 0.07 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 |

| Education | 0.36 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.07 | −0.24 | −0.05 | −0.04 |

| Household members | 0.42 | −0.08 | −0.05 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.02 | −0.08 |

| Occupation | 0.09 | 0.39 | 0.08 | −0.44 | 0.04 | −0.11 | −0.14 | 0.40 |

| Annual net income | 0.14 | 0.31 | 0.47 | −0.19 | 0.21 | 0.02 | −0.08 | 0.16 |

| Residence | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.35 | 0.12 | 0.29 | 0.39 | 0.44 | 0.29 |

| q1 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.42 | 0.31 | −0.30 | −0.26 | 0.31 | 0.05 |

| q2 | 0.00 | 0.48 | −0.30 | −0.10 | −0.03 | −0.05 | 0.17 | 0.16 |

| q3 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.04 | 0.19 | 0.31 | −0.58 | 0.44 | −0.07 |

| q4 | −0.07 | 0.00 | −0.26 | 0.07 | 0.45 | −0.13 | −0.44 | −0.18 |

| q5 | 0.01 | 0.32 | 0.07 | 0.51 | 0.16 | 0.26 | 0.02 | 0.21 |

| q6 | 0.00 | 0.29 | 0.14 | −0.13 | 0.15 | 0.27 | 0.14 | −0.72 |

| q7 | 0.02 | −0.32 | 0.04 | −0.46 | 0.40 | −0.13 | 0.33 | 0.06 |

| q8 | −0.02 | −0.28 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.36 | −0.01 | −0.32 | 0.26 |

| q9 | 0.06 | −0.33 | −0.11 | −0.20 | −0.33 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.18 |

| Canonical Variates | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canonical correlations | 10.000 | 1.000 | 0.996 | 0.979 | 0.786 | 0.594 | 0.276 | 0.038 |

| Sig. of F | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| q1 | −0.415 | −0.520 | 0.180 | 0.312 | −0.390 | −0.206 | −0.432 | −0.354 |

| q2 | −0.105 | 0.016 | −0.063 | 0.035 | 0.328 | 0.090 | −0.186 | 0.141 |

| q3 | −0.138 | 0.067 | 0.292 | 0.439 | 0.096 | −0.160 | 0.333 | 0.211 |

| q4 | 0.989 | 0.755 | −0.220 | 0.457 | 0.228 | −0.837 | 0.006 | −0.895 |

| q5 | 0.051 | −0.135 | −0.171 | 0.149 | 0.031 | 0.293 | 0.191 | −0.149 |

| q6 | −0.399 | 0.616 | −0.432 | 0.087 | −0.587 | 0.139 | 0.110 | 0.296 |

| q7 | −0.053 | 0.707 | 11.240 | −0.020 | −0.035 | 13.120 | −0.358 | −0.728 |

| q8 | 0.672 | −0.189 | 0.120 | 0.207 | −0.334 | 0.276 | −0.296 | 0.757 |

| q9 | −0.050 | −0.358 | 0.425 | −10.553 | 0.050 | −0.023 | 12.925 | 0.312 |

| Covariate | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| PC1 | −0.040 | −0.028 | 0.008 | −0.059 | −0.002 | 0.088 | 0.113 | 0.477 |

| PC2 | −0.328 | 0.058 | −0.556 | 0.285 | 0.354 | 0.096 | −0.369 | 0.092 |

| PC3 | −0.116 | −0.240 | 0.060 | 0.124 | −0.653 | 0.202 | −0.487 | 0.066 |

| PC4 | 0.168 | −0.490 | −0.275 | 0.518 | −0.134 | −0.124 | 0.423 | −0.023 |

| PC5 | 0.433 | 0.494 | 0.123 | 0.495 | −0.015 | 0.427 | −0.002 | 0.045 |

| PC6 | 0.083 | 0.014 | −0.507 | −0.428 | −0.196 | 0.558 | 0.268 | −0.204 |

| PC7 | −0.683 | −0.016 | 0.356 | 0.217 | 0.050 | 0.380 | 0.335 | −0.186 |

| PC8 | 0.290 | −0.589 | 0.266 | −0.081 | 0.487 | 0.425 | −0.247 | −0.042 |

| Variable | Young and Single Consumers | Married Consumers | Educated Consumers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 35.43 | 17.32 | 47.24 |

| Female | 43.28 | 28.36 | 28.36 |

| Age group | |||

| 18–24 years old | 99.25 | 0.00 | 0.75 |

| 25–45 years old | 0.00 | 40.00 | 60.00 |

| 46–60 years old | 0.00 | 37.50 | 62.50 |

| >60 years old | 0.00 | 55.00 | 45.00 |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 100.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Married | 0.00 | 40.31 | 59.69 |

| Presence of children | |||

| Yes | 0.00 | 40.31 | 59.69 |

| No | 100.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Education | |||

| Primary school | 79.35 | 11.96 | 8.70 |

| Secondary school | 53.64 | 20.91 | 25.45 |

| University Degree | 0.00 | 37.50 | 62.50 |

| Professional qualification | 0.00 | 27.27 | 72.73 |

| Household members | |||

| 1 person | 100.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 2 person | 0.00 | 34.94 | 65.06 |

| 3 person | 0.00 | 51.16 | 48.84 |

| 4 person | 0.00 | 38.18 | 61.82 |

| More than 4 | 0.00 | 46.67 | 53.33 |

| Occupation status | |||

| Student | 58.77 | 29.82 | 11.40 |

| Housemaker | 24.49 | 38.78 | 36.73 |

| Employee | 28.44 | 18.35 | 53.21 |

| Self-employed | 33.33 | 13.33 | 53.33 |

| Temporary worker | 50.00 | 12.50 | 37.50 |

| Freelancer | 0.00 | 0.00 | 100.00 |

| Pensioner | 42.11 | 10.53 | 47.37 |

| Inactive | 37.50 | 12.50 | 50.00 |

| Unemployed | 50.00 | 0.00 | 50.00 |

| Annual net income (EUR) | |||

| No income | 50.68 | 31.51 | 17.81 |

| 0–5000 euro | 40.54 | 18.92 | 40.54 |

| 5.001–10,000 euro | 40.00 | 15.00 | 45.00 |

| 10,001–15,000 euro | 31.03 | 17.24 | 51.72 |

| 15,000–25,000 euro | 22.45 | 22.45 | 55.10 |

| >25,000 euro | 31.91 | 14.89 | 53.19 |

| Residence | |||

| Urban area | 65.81 | 27.35 | 6.84 |

| Rural | 41.35 | 35.34 | 23.31 |

| Uninformed Consumers | Conscious Consumers | Informed Consumers | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Q1) When you buy food, how do you usually behave? | |||

| I tend to buy the same products | 54.55 | 68.35 | 47.86 |

| I usually change | 18.94 | 16.46 | 22.22 |

| I try to vary the consumption of food, also based on offers | 26.52 | 15.19 | 29.91 |

| (Q2) When you buy a food product, what do you focus more on? | |||

| Date of packaging | 16.67 | 20.25 | 14.53 |

| Expiry date | 14.39 | 12.66 | 17.09 |

| Ingredient | 17.42 | 17.72 | 11.11 |

| Place of origin | 7.58 | 11.39 | 6.84 |

| Weight | 9.85 | 13.92 | 13.68 |

| Price | 16.67 | 11.39 | 13.68 |

| Nutritional value | 17.42 | 12.66 | 23.08 |

| (Q3) Where do you usually buy food? | |||

| Local store | 20.45 | 21.52 | 17.09 |

| Supermarket | 19.70 | 26.58 | 23.93 |

| Discount | 34.85 | 43.04 | 23.08 |

| Certified organic stores | 10.61 | 7.59 | 14.53 |

| E-Commerce | 4.55 | 0.00 | 11.11 |

| Points of sale chosen by parents | 9.85 | 1.27 | 10.26 |

| (Q4) Did the lockdown (due to the spread of COVID-19) affect the way you purchased food? | |||

| No | 30.30 | 48.10 | 37.61 |

| Yes | 69.70 | 51.90 | 62.39 |

| (Q5) Which of the following certifications do you know? | |||

| PGI | 38.64 | 31.65 | 23.93 |

| PDO | 21.21 | 26.58 | 19.66 |

| Organic | 10.61 | 20.25 | 19.66 |

| DOC | 10.61 | 13.92 | 16.24 |

| DOCG | 6.82 | 2.53 | 6.84 |

| UTZ | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Fair-trade | 3.03 | 2.53 | 0.00 |

| I am aware of all the certifications mentioned | 5.30 | 0.00 | 9.40 |

| I am not aware of the certification acronyms mentioned | 3.79 | 2.53 | 4.27 |

| (Q6) Do you generally buy certified food? | |||

| No | 42.42 | 41.77 | 37.61 |

| Yes | 18.18 | 20.25 | 27.35 |

| Only for some products | 39.39 | 37.97 | 35.04 |

| (Q7) When buying a food product, do you usually view the labels on the packaging? | |||

| No | 58.33 | 36.71 | 67.52 |

| Yes | 41.67 | 63.29 | 32.48 |

| (Q8) Which of the following alternatives gives the exact name “food fraud of a product”? | |||

| Diversity of origin | 25.00 | 31.65 | 35.04 |

| Deformity of quality and quantity of products | 37.88 | 22.78 | 24.79 |

| None of the previous | 37.12 | 45.57 | 40.17 |

| (Q9) Are you afraid to buy and/or consume, without your knowledge, a fraudulent food product? | |||

| No | 33.33 | 8.86 | 34.19 |

| Yes | 66.67 | 91.14 | 65.81 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fanelli, R.M. Italian Consumers’ Perceptions and Understanding of the Concepts of Food Sustainability, Authenticity and Food Fraud/Risk. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1831. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17051831

Fanelli RM. Italian Consumers’ Perceptions and Understanding of the Concepts of Food Sustainability, Authenticity and Food Fraud/Risk. Sustainability. 2025; 17(5):1831. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17051831

Chicago/Turabian StyleFanelli, Rosa Maria. 2025. "Italian Consumers’ Perceptions and Understanding of the Concepts of Food Sustainability, Authenticity and Food Fraud/Risk" Sustainability 17, no. 5: 1831. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17051831

APA StyleFanelli, R. M. (2025). Italian Consumers’ Perceptions and Understanding of the Concepts of Food Sustainability, Authenticity and Food Fraud/Risk. Sustainability, 17(5), 1831. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17051831