In fact, in major urban centers, where significant influxes of quaternary capital enable substantial investments, including real estate, and facilitate public–private partnerships, disused industrial heritage tends to undergo easier reconversion. This is not equally the case in peripheral urban areas, rural regions, or valley floors. It should be noted that in these territories, heavy industry has not entirely disappeared; however, where its spaces have been abandoned, projects for reuse, repurposing, and, ultimately, reterritorialization comparable to those occurring in urban areas have rarely been initiated quickly. Among the many reasons for these phenomena are the reduced availability of public and private capital outside urban areas, the smaller spaces required by the widespread network of contemporary small- and medium-sized enterprises, competition with agricultural land for new construction, and the challenges of remediating some disused sites.

This study focuses on three specific cases, which will be described below. The first case examines the “Make Como” project, which aims to recover and valorize portions of the industrial heritage of the Como region (Lake Como), including the former Cotonificio at Ponte Lambro. The second case concerns the “ex-Breda Industrial Archaeological Park”, which has developed a new identity in locations such as the “Carroponte” and “Spazio Mil”, focusing on the industrial archaeological heritage of Sesto San Giovanni, an important resource whose recovery and valorization policies and projects have long been linked to the broader Milan metropolitan area. The third case study analyzes the “Fiumara” project, which involves the refunctionalization for tertiary uses of a socially complex urban area in Genoa, part of a broader attempt to enhance, also in terms of for tourism flows, the artistic and architectural heritage of the Sampierdarena neighborhood.

5.1. Ponte Lambro

The first project examined is the one carried out in Ponte Lambro, focusing on the vast industrial structures of the former Cotonificio. This site is part of a broader initiative called “Make Como—Saper Fare Far Sapere” (Make Como—Know How and Share Knowledge), financed by Fondazione Cariplo in 2019 (Fondazione Cariplo is a philanthropic organization that leverages its financial and human resources to promote and create opportunities and value for individuals and local communities, supporting cultural, environmental, and scientific initiatives. See:

https://www.fondazionecariplo.it/en/the-foundation/mission/la-misione.html, accessed on 1 December 2024). The project aims to initiate a regeneration process for certain urban and suburban areas characterized by a strong manufacturing tradition but profoundly transformed by industrialization and, subsequently, deindustrialization.

The goal is to recover and valorize the entrepreneurial and industrial archaeological heritage of the Como area, integrating it with the well-known cultural and landscape elements that have contributed to the international reputation of

Lake Como (The collective brand “Lake Como—A Unique World in the World” is a territorial marketing tool developed by the Chamber of Commerce of Como-Lecco and the Province of Como. It aims to promote all the sectors of the Lake Como area and serves as a unifying element for its various excellences: tourism, landscapes, culture, and manufacturing. See: marchiolagodicomo.it). This endeavor seeks to promote an “artificial” beauty complementary to the “natural” beauty of the lake, reflecting both the historical experience of local communities and the economic development that has marked the region: “a potential to be leveraged with a dual purpose: attracting new tourist flows to the area (industrial tourism) and offering the public a cultural and social heritage of great value, which could represent a driving force for current entrepreneurial development in the Como area” (Source:

https://www.makecomo.it/area-diffusa/ accessed on 1 December 2024).

The involved area includes several production districts that, in recent decades, have faced economic crises, closures, relocations, and functional conversions, leading to the abandonment of once-vital spaces. These places now represent the material remnants of an industrial past that helped the process of shaping the local community’s identity and the area’s urban and social development. The loss of industrial activities has left behind an architectural heritage often in decay, in settings now devoid of economic and cultural vitality.

Among historically significant sectors, the textile industry stands out as a longstanding symbol of the region, which has experienced a drastic decline with the closure of the silk and cotton processing plants. These structures, whether repurposed or abandoned, still define the urban landscape. This industrial past, including the intangible heritage of skills, memories, and local community stories (often preserved in the memories of older generations), risks being forgotten unless it is properly remembered, valued, and presented to the public in innovative ways. This is where the ambition to transform these realities into touristic, cultural, educational, and training resources arises, with the objective to serve as inspirational models for new entrepreneurial initiatives in the tertiary sector as well.

An emblematic example of this phenomenon is Ponte Lambro, one of the project’s focal sites. The presence of a significant industrial establishment like the former Cotonificio, first documented in 1840 (the year of its construction), shaped the town’s development and led to rapid population growth over the next 150 years [

43].

The first industrial structure, built along the right bank of the Lambro River and known as “Filatojo Robison” (named after its English owner), was the nucleus of Ponte Lambro’s manufacturing activity. At the time, production was entirely manual, attracting local and neighboring workers, reaching over 400 employees in the years following 1840. In 1860, the factory was purchased by the Prussian entrepreneur Joseph Ohli, who maintained the silk yarn production. Later, under the ownership of Monza-based Rossi Aronne, the plant became a hat factory, employing only 95 workers due to the introduction of machinery. However, this was only a transitional phase, as the Swiss entrepreneurs Carl Ernst and Oscar Rutschmann acquired the facility in May 1891, founding Ponte Lambro’s first true Cotonificio and ushering in a new era of industrial and demographic growth for the little town.

By 1899, the plant boasted 247 mechanical looms, 87 jacquard looms, a steam engine, and a hydraulic engine, each with 80 horsepower. The production areas were illuminated by 240 incandescent lamps, and the site employed over 350 workers. The Cotonificio supported the local community by funding the construction of an aqueduct (still visible today), serving both the factory and the town.

In the early 20th century, the Cotonificio (

Figure 2) participated in major international exhibitions, achieving particular success at the 1900 Paris Universal Exposition. Despite numerous changes in ownership, the company’s growth continued unabated. At its peak during the post-war economic boom of the 1950s, the factory employed around 1500 workers [

44].

However, the factory’s shift from textiles to chemicals led to fluctuating fortunes, culminating in a severe crisis in the 1980s and its eventual closure in 2011 due to bankruptcy. For the history of the Cotonificio, the study relied on the archival research conducted by the local historian Manuel Guzzon (See his testimony at:

https://www.facebook.com/watch?v=618608579927013 accessed on 15 October 2024).

The factory’s closure eroded not only the economic fabric but also the social structure, turning Ponte Lambro into a “bedroom community” with a substantial portion (12.8%) (source:

https://www.tuttitalia.it/lombardia/71-ponte-lambro/statistiche/cittadini-stranieri-2023/ accessed on 1 December 2024) of residents being foreign citizens, primarily from Romania and Pakistan, attracted by lower housing costs compared with the broader Lake Como area.

In line with the objectives of the

Make Como project, this study has not been limited to considering the demographic and production data related to the history of the former Cotonificio, but it broadens its analysis to encompass the tourist flows directed toward Lake Como. This perspective highlights how this tourist district occupies a privileged position in the national and international tourism market, emphasizing the strategic potential of the combination of industrial heritage and scenic attractiveness. Since 2014, the year before the Milan Expo (held in 2015), which was a significant turning point for the provincial and regional tourism system (as highlighted by the Tourism Observatory of Assolombarda:

https://www.assolombarda.it/centro-studi/osservatorio-turismo-2023-1 accessed on 1 December 2024), tourist arrivals and overnight stays have grown significantly, even withstanding the 2019 pandemic. In 2023, Lake Como recorded around five million overnight stays, a 20% increase from 2019, with foreign tourists (mainly from Germany and the USA) predominating (source:

https://www.comolecco.camcom.it/pagina542_turismo.html accessed on 1 December 2024).

These data highlight the opportunity to promote targeted strategies aimed at revitalizing locations that are less known compared with the areas of Lake Como with a higher tourist appeal, but that are nonetheless capable of attracting experiential and authentic tourism [

14,

34]. In fact, the growing development of new tourism experiences in Europe, focused on the authenticity of places and the enhancement of their industrial and productive essence (source:

https://www.coe.int/it/web/cultural-routes/european-route-of-industrial-heritage; https://

www.erih.net/ accessed on 1 December 2024), has led to recognizing Lake Como’s potential to tap into this emerging demand.

In this context, the

Make Como project was launched with the goal of expanding the local tourism by integrating cultural content into the region’s industrial heritage. The project also aims to draw visitors’ attention to less-visited areas of Lake Como, such as Ponte Lambro, which preserve a cultural heritage and productive tradition capable of serving as a significant tourist attraction. For this reason, the initiative is promoted and supported by the Como-Lecco Chamber of Commerce (source:

https://www.comolecco.camcom.it/pagina597_make-como.html accessed on 1 December 2024).

The Make Como itinerary is inspired by the workers’ village of Crespi d’Adda, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and seeks to rediscover the original uses of the buildings that form the town’s urban fabric, most of which have remained largely unchanged over time. The route covers everything from workers’ houses to the owner’s residence at the former Cotonificio, as well as the infrastructure and initiatives launched by the management of the factory to improve working conditions and, more broadly, the daily lives of its employees. The project, which includes a widespread itinerary aimed at showcasing the original architectural heritage inherited from the cotton mill, has involved the execution of minor refurbishment work and the installation of informational panels along the route, each featuring a QR code linking to a promotional website for

Lake Como tourism (The “Expo Green Land Tourism Attraction District” project was born owing to the participation in the Regional “Tourism and Commercial Attraction Districts” tender. Project no. 52574412. Source:

https://www.lakecomogreenlands.com/ponte-lambro/ accessed on 1 December 2024) (

Figure 3).

For the Ponte Lambro site, Make Como has designed an engaging and immersive museum experience centered around cotton, the material that defined the success of both the enterprise and the region. This initiative includes the creation of an interactive and experiential museum dedicated to cotton, from its cultivation to finished products, as well as to the history of the former Cotonificio (source:

https://www.makecomo.it/gli-interventi/ponte-lambro/ accessed on 5 December 2024). The museum is housed in several rooms on the first floor of Villa Guaita, an 18th-century building that once served as the representative villa of the Ponte Lambro cotton mill’s owners. The villa, now owned by the municipality, has been granted for use under the project’s goals. After the visitor center, a flexible, multifunctional space has been set up to host culturally themed meetings and conferences as well as educational and edutainment activities for a younger audience. Two more rooms are dedicated, respectively, to the interactive and virtual museum, which tells the story of the Cotonificio and the workers’ community that grew around it, and to the experiential cotton exhibit. This latter exhibit is enriched with tactile, olfactory, visual, and auditory stimuli to provide a multi-sensory experience. The final area involved in the project is an

Immersive Room designed to add an emotional dimension to the visitor experience. Once completed (the date is currently uncertain), this room will transport visitors into the production dynamics of the past as well as to modern cotton processing techniques. To complement the

Immersive Room, the development of a series of video testimonials aimed at preserving the region’s intangible heritage has been initiated, though it remains in progress. This project aims to collect memories and knowledge passed down by those who experienced the golden age of the cotton mill, with a special focus on the elderly, the true custodians of invaluable lore at risk of being irretrievably lost.

To assess the benefits and challenges posed by the factory’s presence in the local community and surrounding area, as well as the potential role of the Make Como project in preserving historical memory and fostering a sense of belonging to the site, interviews were conducted during the study. Ten residents of Ponte Lambro, a former CEO of the factory, and the town’s mayor were interviewed and invited to describe their relationships with the industrial site, providing direct perspectives on the significance and legacy of the Cotonificio. Simultaneously, the study analyzed the potential impact of the project on the area, focusing specifically on economic and social sustainability, with particular attention to development opportunities linked to the tourism sector.

Most interviewees, three men and four women aged 30 to 50, emphasized the importance of preserving the memory of the former Cotonificio, noting that all local families had at least one relative (grandparents, parents, or uncles/aunts) who was employed at the facility. Two interviewees, a man and a woman aged 65 to 75, shared their experiences as former workers, expressing emotion as they recalled the factory’s role as a source of pride for the community.

The factory not only provided stable employment to many families, including those from neighboring towns, but it also generated significant business volume that enabled exports to numerous foreign countries, enhancing the town’s reputation and prestige. This sentiment was echoed by the retired former CEO, who confirmed the factory’s significant impact and international renown.

A significant aspect that emerged from the interviews concerns the gender dynamics within the former Cotonificio. Some interviewees highlighted the pivotal role of women’s labor in the textile factory. One respondent, in particular, recounted how both her mother and grandmother worked at the factory, while the men in the family were traditionally engaged in agricultural activities. This finding is especially significant within the context of Gender Studies, as it may suggest early forms of social emancipation for women through their participation in industrial work. Similarly, this observation was echoed by the daughter of a factory worker, who confirmed the essential contributions of women both in the labor force and in administrative roles. While specific gender-disaggregated data for the 1500 workers employed at the factory is unavailable, the qualitative insights from the interviews and some photographs displayed in the museum provide compelling evidence of this significant aspect.

A local middle school teacher, on the other hand, pointed out the limited knowledge among younger generations regarding the history of the former Cotonificio, even among those whose families might have had relatives working there, but who have since lost memory of that connection. This phenomenon is particularly pronounced among youth of foreign origin, who lack a specific link to the area’s history, raising new questions and perspectives about the construction of a collective identity for future generations.

The creation of a museum is unanimously regarded by the interviewees as a significant initiative, particularly for promoting school visits and preserving an essential part of the local heritage. However, a shared concern was expressed regarding the unrestored portion of the former factory, which risks becoming an “eco-monstrosity” on the riverbank. This situation could lead not only to the loss of historical memory but also to aesthetic detriment for potential future tourism development. In this regard, the mayor and the municipal administration are working on the development of a pedestrian and cycling trail to connect the former Cotonificio in Ponte Lambro with the historic Co.Ri.Ca.Ma knife factory in Caslino d’Erba, another large abandoned site. While this project operates independently of the Make Como project, it aligns with the same objective of enhancing the area, particularly by emphasizing the historical and symbolic importance of the Lambro River—a natural feature central to the area’s identity. The river is currently characterized as “hidden”, and its potential remains unrealized. The thematic trail aims not only to link key sites of industrial heritage but also to restore the Lambro River’s prominence, highlighting it as both a scenic and cultural resource. At present, the project is in its preliminary design phase, and it has not yet been integrated with other local initiatives. However, the mayor emphasized the geographical significance of the plan, stating: “Ponte Lambro takes its name from the river that runs through it, but curiously, this river is invisible as you pass through the town. It’s hidden!”.

The potential of these initiatives could be further enhanced by the presence of the regional railway line, which connects Ponte Lambro to Erba, from there to Como (reachable in about 30 min by bus), and, more importantly, to Milan, located just around 50 km away. Currently, however, this infrastructure is primarily used by commuters rather than tourists. Despite the advantages offered by this connection, the projects in question have yet to translate into significant tourist activity, partly because the enhancement efforts were only recently completed in May 2024.

As of now, the cotton museum is accessible only during specific events or established occasions, such as the “Ville Aperte” (in English, “Open Villas”) initiative by the Italian Environmental Fund (FAI) or the September bee festival. This limited availability is mainly due to a lack of financial resources, personnel, and a consistent tourist flow to sustain the initiative. However, a deeper issue appears to lie in the territory’s inability to narrate and promote its own history—particularly its legacy of intense industrialization during the last century—due to the absence of a robust territorial marketing strategy. Nonetheless, this historical heritage, which is often overlooked or even hidden because of the negative associations with heavy industrialization, remains alive in the collective memory of the residents, as demonstrated by the testimonies and stories gathered during the interviews. As Richards (2014, p. 11) points out, “Places and destinations also need to use stories to make themselves readable for visitors, and to validate the reasons why people travel to visit them. Storytelling techniques will therefore become increasingly important in the cultural tourism market in the future” [

9].

5.2. Sesto San Giovanni

Strategically located as a vital node of the Milan Metropolitan Area, Sesto San Giovanni, which serves as a crucial hub for regional and extra-regional communications, is the second analysis of this contribution, which focuses on the refunctionalization of one of its former industrial areas. Located 8 km from the Milan Cathedral (known as “Duomo di Milano”), Sesto San Giovanni (from this point forward, Sesto San Giovanni will be referred to as Sesto) is a dynamic urban center in Lombardy. It is the region’s eighth most populated city, with a population of 78,500 [

45].

Sesto shows a polycentric structure; the municipality spans about 11.7 km

2 and includes five sub-municipal districts (The five Sesto sub-municipal districts are (a) Rondò/Torretta; (b) Rondinella/Baraggia/Restellone; (c) Isola del Bosco/Delle Corti; (d) Pelucca/Villaggio Falck; (e) Dei Parchi/Cascina Gatti/Parpagliona). Sesto was an agricultural village until the early 20th century, housing approximately 6000 inhabitants [

46]. The urban landscape began to undergo a radical transformation with the settlement of large-scale industry, marking that era as a crucial moment that shaped the characteristics of subsequent urbanization forever. The city started to become modelled around four major manufacturing conglomerates (Breda mechanical engineering, Falck steelworks, Ercole Marelli electromechanical industry, and Magneti Marelli electrical applications), next to which residential areas emerged, serving as hubs for migration flows. In that time, Sesto was known as Italy’s “Little Manchester” and “City of Factories” (It was also called, in the 20th century, “Little Stalingrad” because of the strong historical presence of the Communist Party and its exceptional legacy of resistance to Fascism) [

47].

Area ex-Breda, a 0.32 km2 site that serves as a compelling case study in industrial heritage revitalization in Northwestern Italy, is located in Rondò/Torretta, one of the five sub-municipal districts, that is home to 19,000 residents and covers approximately 2 km2 bordering the municipality of Milan.

Area ex-Breda had a dense concentration of factories and workshops, employing thousands of workers in steel production, mechanical engineering, metalworking, and aeronautics while contributing significantly to the regional and national economic growth [

48].

Founded in 1903, Breda initially employed 4500 workers, drawn by the strategic advantages of its location near a key railway hub (

Figure 4) [

49].

Over subsequent decades, the company expanded into diverse industries, including mechanical engineering, steel production, and transportation, supported by substantial government contracts. By the 1960s, Breda reached its occupational peak, employing 20,000 workers, solidifying its position as one of the key economic drivers in the region [

46].

The last two decades of the 20th century witnessed a significant decline in manufacturing activities, characterized by plant closures, workforce reductions, and economic hardship. In the 1980s, the group was sold, and its operations ceased by 1996 [

50]. The closure of Breda and the other Sesto factories left a void in the local economy and community, leading to job losses, economic decline, and abandonment of industrial spaces.

This period posed significant challenges for Sesto, which had to face economic instability, environmental damage, and social problems as well as the necessity and urgency to shift toward new, diverse economic models [

51].

The revitalization of several large deindustrialized areas in Sesto, including the Breda, Falck Vulcano, and Marelli sites (Breda, Falck, and Marelli were the largest manufacturing and metallurgical factories in Sesto. Falck Vulcano was a plant belonging to Falck), started in November 1994 with the PRG (General Urban Plan), which established the “Zone di Trasformazione” (in English, transformation areas) with corresponding regulatory frameworks that outlined functional uses, building density, and service requirements.

Between the adoption and approval of the plan, the municipal administration, in response to regional input, also addressed the redevelopment of disused sites, aiming to steer the transformation of these large spaces and minimize land consumption. More than 1.1 km

2 of former Sesto industrial land, yielding a total gross floor area of approximately 0.6 km

2, had been impacted. Only 18% of this was allocated for residential purposes, while 61% was designated for productive activities, and roughly 10% for tertiary functions [

52].

A particularly unique urban transformation took place around the time of the adoption of that PRG in the Area ex-Breda. A defining feature of the urban plan was the use of the area for small–medium enterprises (SMEs) dealing with sectors such as light manufacturing, construction, telecommunications, and distribution.

The redevelopment of the Area ex-Breda unfolded over a relatively short period between 1992 and 1996 and was marked by the signing of the “Accordo di Programma” (in English, program agreement) with the Lombardy Region.

The Area ex-Breda is bisected diagonally from northwest to southeast by Via Luigi Granelli, which belongs to Sesto. The southern portion of this division, though administratively part of the Sesto municipality, exhibits a functional urban continuity with the neighboring city of Milan, where the Hangar Bicocca and Bicocca Village Mall are located. Conversely, the northern section of the division is characterized by the “Parco archeologico industriale ex-Breda”. This site, beyond its green spaces, features three iconic structures representing Breda’s industrial heritage: the Carroponte, Spazio MIL, and the Torre dei Modelli, blending industrial legacy into a cohesive space.

Preserving iconic industrial structures required guidelines that established architectural and spatial standards and ensured new constructions were compatible with the historic environment.

The guidelines for protecting the Sesto’s industrial heritage had their roots in the PRG of 2004. Additionally, following an attempt in 2006 to nominate the territorial features of the “City of Factories” as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the 2009 Territorial Government Plan (

Piano di Governo del Territorio, PGT) further developed this concept. It established a detailed catalogue of the most significant buildings and complexes to outline gradual intervention strategies for their conservation and potential reuse (The application process to become a UNESCO World Heritage Site in the “Organically Evolved Landscape” category began in April 2006; this attempt was unsuccessful, mainly due to administrative issues) [

52].

The building’s industrial character has been maintained while incorporating modern elements to create flexible and inviting spaces, such as “Spazio MIL” (Industry and Labor Museum) and “Carroponte” (In addition, remarkable examples of industrial buildings’ adaptive reuse are also the Giovanni Sacchi Archive, a museum dedicated to the work of a renowned model maker, and “Torre dei Modelli”, a cylindrical tower built in 1947 that once served as a central hub for the storage and transportation of Breda models. Today, it stands as a prominent landmark in Area ex-Breda, symbolizing the city’s post-war revival). Further enhancing the site’s industrial narrative is Michele Festa’s monumental sculpture, strategically placed to visually connect with the Carroponte. Festa’s “Porta” serves as both a symbolic gateway to the Area ex-Breda and a contemporary interpretation of the site’s industrial past. This sculpture establishes a dialogue with the Carroponte, creating a sense of continuity between the past and the present. By doing so, Festa’s work not only pays homage to the site’s history but also enriches its contemporary identity as a cultural and industrial landmark.

In the 1980s, amid deindustrialization, local leaders and community members began advocating for a museum to protect Sesto’s industrial legacy. The ex-Breda site, rich in architectural and historical value, became the designated location for a museum, aiming at capturing and communicating a century of industrial history. Nonetheless, it was not until 1998 that political and financial support aligned, allowing redevelopment plans for specific projects.

The architectural design emphasizes the original materials and structures, with renovations that respect the aesthetic of the original 1930s-era warehouse buildings. The use of open steel structures, brick facades, and large windows ensures that the industrial character of the site remains a focal point, enhancing its value as a preserved landmark in the urban landscape.

Visitors to Area ex-Breda encounter a range of exhibitions and preserved artifacts, including the Carroponte (See Instagram @carroponteofficial and Facebook Carroponte for more information.) and a towering crane built in 1930 that once transported metal scraps to furnaces in the steel plant. This iconic structure has been repurposed into a popular outdoor theatre that hosts local and international artists for concerts, festivals, and cultural events, demonstrating its capacity to draw visitor flows.

The redevelopment of the Carroponte in 2006 not only preserved a significant piece of industrial history but also created a cultural hub that draws large crowds of visitors both from Sesto and other municipalities. The Carroponte (The structure occupies an area of about 30 × 200 m, with a height of about 20 m. The facility is part of the Spazio MIL and is inserted within a wide area of green-equipped urban public space and welcomes, in the space below, the locomotive “Breda 830” of 1906, recently restored.), now a symbol of Sesto’s past and present, represents a monumental element of the “Parco archeologico e industriale ex-Breda” (

Figure 5).

Central to the redevelopment project was also the creation of “Spazio MIL”. Spanning approximately 2000 m

2 within the ex-Breda Spare Parts Warehouse complex, the museum serves as a dedicated space for celebrating the legacy of Sesto workers and industries [

53]. It was designed to retain many of the original architectural features, from the brick facades to the steel beam structures. Spazio MIL has extended its influence beyond Sesto through partnerships with other European industrial heritage sites, including collaborations with sites in France and Belgium. These collaborations culminated in the traveling exhibition, “Decommissioned Industrial Areas: Between Memory and Future”, which addresses how former industrial areas across Europe are being reimagined for modern uses. Through this exhibit, Spazio MIL not only engaged with international audiences but also situated itself within a larger European context of industrial heritage preservation, emphasizing the shared value of industrial landscapes.

Nowadays, the Spazio MIL has evolved and incorporates two functions: firstly, it serves as a conference area; secondly, it hosts a multimedia area, managed by Next Museum Milano (Next Museum is the brainchild of Next Exhibition, a company devoted to immersive technology events. See Instagram @next.museum and Facebook Next Museum for more information). This company specializes in immersive exhibitions and utilizes digital and interactive technology to engage visitors using augmented reality experiences.

In addition, within Spazio MIL still lies the Giovanni Sacchi Archive. At the moment, it is closed to public visits, and it is available only on request for academic purposes. This space is an homage to Sacchi, a master model maker and an influential figure in post-war Italian design. The archive displays Sacchi’s original tools, models, sketches, and photographs, offering a collection for those interested in industrial and design history.

Looking ahead, Spazio MIL and its surrounding spaces are set to evolve further as they continue integrating augmented reality experiences, expanding digital archives, and developing interactive exhibits that will allow the whole Area ex-Breda to reach broader audiences.

Restoration work at Area ex-Breda preserves the original building materials, ensuring that renovations enhance the historic value rather than detract from it, allowing visitors and residents to experience a sense of the past within a modern context. Structures feature robust materials like brick, concrete, and steel, with architectural details that reflect the Sesto’s history. Buildings such as Carroponte and Spazio MIL are safeguarded and have become landmarks in the Area ex-Breda skyline, with their large frames and exposed industrial elements creating a unique architectural contrast with modern developments.

By prioritizing sustainability, redevelopment efforts incorporate energy-efficient design and environmentally friendly practices. Adaptive reuse allows for the repurposing of industrial buildings to serve contemporary functions. This approach not only brings new life to abandoned or underutilized spaces but also helps reduce waste and the environmental impact associated with demolition and new construction.

As part of the study, interviews were conducted to explore the theme of industrial heritage compared with Sesto’s post-industrial present, particularly focusing on the Area ex-Breda.

A municipal official responsible for cultural activities said: “As the city adapts to a post-industrial identity, it has not fully settled into a new form yet, while changing forces, such as the rise of a service-based economy, an aging population, and increasing cultural diversity, present both challenges and opportunities”. According to the interviewee, key challenges include a general lack of awareness about Sesto’s industrial, social, and political legacy among new generations and recent residents (both Italian and with migratory backgrounds). Sesto San Giovanni features a significant multicultural dimension that is reflected in its urban landscape. Currently, registered foreign residents number approximately 13,000, representing about 17% of the city’s population. This share is slightly lower than Milan’s 18% but is higher than the overall Milan Metropolitan Area’s average of 14.7%. These statistics underscore the dynamic and diverse demographic composition of Sesto, which continues to shape its social and urban identity.

Two retired workers, residents of the Rondò-Torretta district, were also interviewed. One of them, a former foreman at the Breda factory, recalled their working experiences with emotion and pride, reminiscing about when Sesto was known as the “City of Factories”. The foreman emphasized the strong culture of social and political engagement during that era and the pivotal role workers played within Breda. However, both retirees lamented the lack of knowledge among younger generations regarding the importance of the factory and its impact on the territory and community of Sesto.

A local teacher shared insights into activities designed to educate middle school students about the area’s industrial past. Until about seven years ago, guided tours of the territory included visits to the Area ex-Breda, where former workers explained the functions of facilities such as the warehouses and the Carroponte as well as life inside the factory. These stories were later explored in depth within the classroom, fostering a connection between students and the area’s industrial history.

However, interviews with two 18-year-olds with a migration background revealed a lack of awareness about the area’s historical significance. For them, the Carroponte was solely associated with its current functions, hosting music events and exhibitions, while the industrial and social past of the Area ex-Breda remained unknown.

Lastly, an interview with the previous exhibition and events manager of Archivio Sacchi provided valuable insights: “The current focus just on isolated cultural and entertainment events alone risks hampering the visibility and recognition of the Area ex-Breda industrial past”. Moreover, he also pointed out that “New residents, whether local or foreign, often fail to develop an appreciation of industrial legacy because they are generally uninformed and insufficiently engaged in ongoing transformation projects and heritage initiatives. This limited participation restricts the integration of these groups into the city’s historical and cultural narrative, potentially weakening the preservation and transmission of Sesto’s special identity”. During the interview, he envisioned a polycentric model for Sesto that promotes integration between the central and peripheral areas, valuing all resources within the sub-municipal districts. This process could establish a bridge between the past and future, fostering connections across generations and neighborhoods.

Raising public awareness and enhancing education in the redevelopment process ensures that the needs and voices of the inhabitants are reflected in the outcomes. An inclusive approach, through initiatives such as interpretive signage, guided tours, and educational programs, contributes to the area’s cultural resilience.

In Area ex-Breda, adaptive reuse has transformed former factories and warehouses into cultural venues, offices, and recreational spaces, all while maintaining the structures’ historic character.

While the number of residents in the neighborhood has remained relatively stable, Area ex-Breda has experienced a significant influx of new users attracted by new amenities and cultural attractions, enriching socialization and fostering a more inclusive environment.

By repurposing abandoned industrial buildings into cultural venues, commercial spaces such as “Centro Sarca”, SME, and urban green spaces, the refunctionalization efforts have significantly revitalized the area and enhanced Area ex-Breda’s skyline and visual identity.

Within the “Parco Archeologico e Industriale ex-Breda”, promoting green space accessibility is vital, particularly in relation to the “Parco Nord Milano”, parts of which fall within the municipal boundaries of Sesto San Giovanni. This park plays a significant role in addressing the challenges of urban areas within a historically industrialized and environmentally complex territory [

54]. However, pedestrian and cycling connections between the “Parco Archeologico e Industriale ex-Breda” and “Parco Nord Milano” remain insufficiently publicized, limiting their potential to foster sustainable mobility and enhance the integration of these vital green spaces. Improved signage, pathway development, and promotional initiatives are necessary to bridge these gaps and maximize the parks’ environmental and social benefits.

Area ex-Breda occupies a strategic location, benefiting from strong external connectivity through public transportation and major roadways. The Sesto Rondò (M1 line) and Bignami (M5 line) underground stations, constructed in 1986 and 2013, respectively, have significantly enhanced mobility to and from the area. These developments have bolstered accessibility to the broader metropolitan region, supporting connections beyond Sesto’s municipal boundaries.

Despite these improvements, challenges persist regarding local accessibility from adjacent neighborhoods in Sesto and Milan. Physical barriers, such as infrastructure and urban layouts (Three wide roads with lanes separated by tree-lined sidewalks and railway tracks, such as Via Carducci, Via Milanese, and Via Granelli, represent fences for the neighboring walkability to Area ex Breda), hinder the seamless integration of Area ex-Breda into the surrounding urban fabric. As a result, the area remains somewhat isolated from the everyday life of nearby districts, limiting its full inclusion in the social and economic dynamics of the city. Addressing these barriers is essential for ensuring that Area ex-Breda becomes a well-connected and integral part of both Sesto and Milan.

The post-industrial renewal of Area ex-Breda within Sesto’s social and urban fabric highlights improvements that merit close attention to ensure the success and sustainability of its transformation.

An emphasis on connectivity, manifested in improving walkability and creating cohesive urban networks, promotes community interaction, enabling residents and visitors to explore the area on foot, discovering industrial landmarks, renewed green areas, and facilities along the way.

While the regeneration process has encompassed various approaches, its outcomes reveal differing levels of success in preserving and promoting the site heritage. The Sarca shopping center, for instance, exemplifies an unexploited opportunity: while the conversion of an industrial space into a commercial center has revitalized the area, the lack of emphasis on the site’s industrial past has resulted in a loss of cultural and historical significance.

In contrast, the Carroponte was repurposed, capitalizing on its industrial heritage and maintaining the original structure. Patrimonialization should not be limited to physical restoration and functional reuse; on the contrary, it must be strengthened through greater awareness in the community and among service users for what concerns the cultural and historical heritage represented, emphasizing the site’s industrial value.

This awareness can be fostered through educational initiatives, interpretive signage, and targeted marketing that connect people with the industrial legacy of the area. By integrating these elements, patrimonialization not only preserves history but also instills a sense of pride and ownership in the community.

The industrial pathway known as “La Città delle Fabbriche”, established in 2002, once played a pivotal role in commemorating Sesto’s industrial legacy. Supported by strategically placed totems providing information about sites like Area Breda, the pathway served as a physical and symbolic thread linking key elements of the town’s industrial heritage. However, following changes in municipal governance in 2017, these totems were removed due to their degraded condition, resulting in the erasure of a vital narrative for visitors and residents alike. Without these markers, the memory of the workers who shaped Sesto’s industrial history has faded, leaving no visible traces for new generations or visitors to engage with the site’s historical significance.

Moreover, the approach to patrimonialization in Area Breda has partially followed the framework of “Authorized Heritage Discourse” (AHD), which prioritizes the material aspects of heritage while marginalizing intangible cultural elements [

23]. This top-down approach has excluded the neighborhood community from meaningful participation in decision-making processes, reducing their role to passive observers. Such practices risk commodifying industrial heritage for economic gain, leading to the disappearance of the workers’ memories and stories that once defined the area’s identity.

It is desirable that Sesto reconsiders and improves its approach for preserving industrial heritage. Revitalizing initiatives like “La Città delle Fabbriche” with modern tools such as QR codes, augmented reality applications, and interactive digital storytelling could effectively bridge the gap between material heritage and its intangible legacy. By involving local communities actively in the patrimonialization process, Sesto can ensure that its industrial past remains an integral part of its identity. Furthermore, engaging in collaborative networks with other cities that share similar industrial heritage experiences can provide valuable insights and promote sustainable urban regeneration. Memory, when preserved and celebrated, not only reconstructs a community’s past but also offers a shared foundation for envisioning its future.

5.3. Sampierdarena

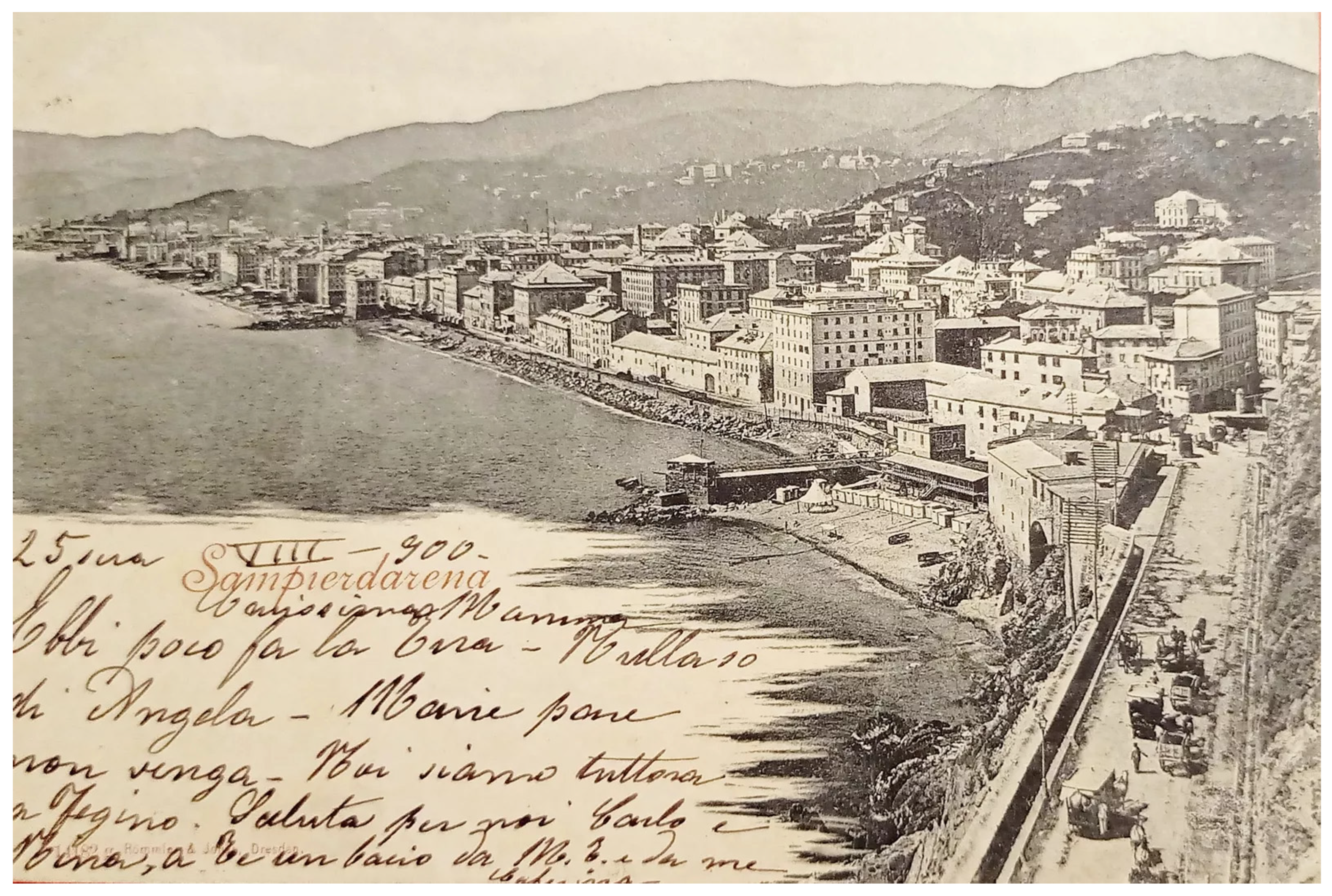

The final area under analysis is the neighborhood of Sampierdarena (which was an independent municipality until 1929; today, it is part of the Municipality of Genoa), located west of Genoa’s historic center and extending to the mouth of the Polcevera River. Until the late 19th century and the significant impact of heavy industry, Sampierdarena was home to a wealthy population living in 16th- and 17th-century villas overlooking the sea (

Figure 6), from which it is now completely separated due to road and port infrastructure (The neighborhood is also separated from the historic center by the ferry and cruise terminal) [

55]. Over time, port activities and heavy industry, followed by deindustrialization and the rise of the service sector, have repeatedly reshaped the socio-territorial fabric, leaving behind clear architectural traces that testify to the area’s heterogeneous past [

56].

In fact, the urban landscape encompasses Renaissance villas, towers, and residential buildings alongside industrial-era factories and port-related infrastructure, creating an intersection of past and present territorial identities. These elements reflect the subsequent urbanization linked to industrialization and have occasionally been repurposed within a contemporary social context that appears “suspended between the fragmentation of past vocations and the difficult search for new territorialities” [

57]. Sampierdarena has now lost its working-class identity, along with nearly a quarter of its population in favor of a multiethnic character (it hosts the largest Ecuadorian community in Europe). The population decreased from about 60,000 inhabitants in the 1960s to about 40,000 in the 2000s. In 2020, there were 42,979 inhabitants, distributed across the approximately 3 km

2 of the neighborhood. Of the residents, 25% were born abroad, while only 52% were born in the Municipality of Genoa (Comune di Genova 2021). Today, the neighborhood’s economic base is primarily in services, often with low-skilled employment, in a territory where the secondary sector has lost much of its importance (The president of the municipality highlighted issues related to unemployment and precarious, low-paying jobs).

This context makes it particularly relevant to analyze the relationships between architectural and landscape heritage, the local community, and new identities. Efforts to enhance Sampierdarena’s diverse heritage have included both Renaissance villas and industrial buildings. The Genoa Municipality’s tourism promotion portal (The portal,

https://www.visitgenoa.it/it/sampierdarena, accessed on 29 November 2024, in its section dedicated to Sampierdarena, mentions historic villas, watchtowers, churches, two theaters, and the Fiumara shopping center. It also mentions the Lanterna (lighthouse) of Genoa, a symbolic monument of the city, which, however, is not connected to the neighborhood and is more easily accessible from the historic center) and the FAI website publicize both the Renaissance villas and historic watchtowers. These sites are also marked on physical maps and digital totems placed throughout the neighborhood. As for industrial heritage, the area of the former Ansaldo railway factory, called “Fiumara”, has been repurposed: while retaining its industrial architectural features, it now houses a commercial area with a multifunctional sports arena, entertainment facilities, office spaces, and residential towers.

The main focus of this work is on the repurposing project known as Progetto Fiumara, developed between the 1990s and 2000s, immediately east of the Polcevera River’s mouth. This initiative aimed to revitalize a neighborhood marked by population decline and urban and architectural decay while preserving the industrial heritage. Interviews were conducted with ten residents of Sampierdarena and the president of the City of Genoa’s “Municipio II” (the political and administrative entity that governs neighborhoods in large Italian cities; municipalities are called “comuni”) to assess the impact of these heritage-making interventions. Questions addressed whether the redevelopment of the former factories contributed to preserving the neighborhood’s working-class memory, its effects on the social and economic fabric, and whether Sampierdarena benefited from the project in terms of tourism or visitors from other parts of the city. Comparisons were also drawn with the neighborhood’s other key heritage assets, the Renaissance villas.

In the intentions of the stakeholders (the municipality, the region, and private investors), the area was chosen for its potential to repurpose an abandoned space and revitalize the neighborhood. This should have been achieved by creating new jobs, attracting new residents (as part of the project, three residential towers were built), and bringing in visitors drawn primarily to leisure activities. These visitors were expected to be attracted by the shopping center, the cinema, and the events fairs hosted at the sports arena, all located in an area easily accessible both by car and by public transport [

58,

59]. At the same time, efforts were made to preserve elements of the neighborhood’s heritage: the shopping center retains the architectural layout of the original industrial buildings, historical images and photographs of the factory are displayed inside (

Figure 7), and one of Italy’s first locomotives, built in Sampierdarena by Ansaldo, stands in the urban park. Additionally, a new urban park surrounding the shopping center was developed on the previously abandoned industrial site and made available to the neighborhood, which, particularly in its southern section, has very few public green spaces.

Initially, the project was welcomed positively, although local press and academic research often highlighted only the perspectives of new residents within the complex, workers, and area users, while neglecting the broader neighborhood context [

60]. However, in subsequent years, social problems emerged, revealing that not only had the project failed to have positive effects on the neighborhood, but unresolved issues (such as decay and petty crime) had spilled over into the repurposed area. Problems of urban decay and petty crime prompted the shopping center management to close the privately owned urban park at night. The president of the municipio clarified that the only substantial collaboration between the shopping center and the municipio concerns security, mainly the installation of cameras integrated with public ones.

The interviews show a fragmented understanding among residents of the links between the neighborhood’s history and its heritage elements. Older residents or those with familial roots in Sampierdarena often recall, with nostalgia, its working-class identity and noble past, and they are able to connect this heritage to the architectural elements. This is not the case for more recent arrivals, particularly new Italian residents. However, some younger people with immigrant backgrounds mentioned that their schools had involved them in projects to explore the territory and its heritage (e.g., internships with the FAI or local cultural associations). These findings are confirmed by the president of the municipio, who highlighted Sampierdarena’s numerous and active associations, many of which are dedicated to preserving and promoting the neighborhood’s heritage and historical memory.

One significant example of this fabric is the “Cercamemoria” (in English, “Memory searchers”) group, which primarily focuses on spreading awareness about the Renaissance villas, and the “Officine Sampierdarenesi”, which address issues of labor, social policy, and environmental concerns in the neighborhood. As their name suggests, the Officine Sampierdarenesi (in English, “Sampierdarena workshops”) draw their roots from Sampierdarena’s industrial and port past. Several associations of this kind are currently opposing a proposed chemical waste storage facility near the neighborhood in the port area and, according to the interviewees, this project contradicts the intentions expressed during the planning of the Fiumara complex regarding the neighborhood’s tourism promotion.

The president of the municipio also emphasized the role of the

Centro Civico Buranello, which attracts a wide range of residents with social, cultural, or leisure activities, regardless of their age or place of origin. However, he also perceives a lack of interest among younger generations and new Sampierdarena residents in the neighborhood’s history and artistic heritage. He noted that it is almost exclusively long-time “historical Sampierdarena residents” who participate in cultural associations and events related to the area’s history and culture. Nonetheless, it should be highlighted that targeted cultural integration efforts to encourage the participation of new residents have never been introduced [

61]. Despite this, both local inhabitants and the president acknowledge the neighborhood’s significant tourism potential, especially given the appeal of its historic villas, as recognized by the FAI, in a region that already attracts flows of visitors heading to Genoa or coastal resorts. Also, it is extremely important to mention the cruise passengers who disembark near Sampierdarena.

However, the reasons behind the lack of actual tourism flows to Sampierdarena can be traced, according to the interviewees, to several factors. These include the limited investment by the municipality (the president of the municipality has complained, particularly in recent years, about budget cuts in financial transfers from the Municipality), the political discourse that frames Sampierdarena as a degraded neighborhood, and two distinct barriers that divide the area. First, Sampierdarena is the only coastal neighborhood in Genoa from which the sea is neither accessible nor visible. Second, there are significant challenges to pedestrian access from the historic center and the nearby ferry terminal. These barriers effectively cancel out what would otherwise be short distances, due to the difficult accessibility and lack of visual continuity in the landscape.

In addition, all interviewees agreed that the people traveling to the Fiumara shopping center do not contribute to the neighborhood’s social or cultural fabric, and many are unaware of the historical and heritage value of the area. On the contrary, they arrive by car or from the nearby railway station (it is served by frequent trains crossing Genoa (and, in some cases, Liguria) from west to east and vice versa), often ignoring the surrounding neighborhood. Moreover, in recent years, the shopping center has unfortunately become the site of violent crimes, including assaults, drug trafficking, and fights, which have worsened the already complex social dynamics of Sampierdarena instead of enhancing the neighborhood, as planned in the project.

Furthermore, the opening of the shopping center in the early 2000s has significantly contributed to the closure of many small local businesses, which offered important services to the residents and were seen as vital community hubs. The closure of these shops is a particularly noticeable loss among the older residents, who have seen Sampierdarena transform over time. The president also views the shuttered storefronts as a loss of social ties within the neighborhood (The president of the municipio estimates a 25% loss in commercial activities since the opening of the shopping center, dropping from about 1000 to about 750). Moreover, even younger people do not view the shopping center as a favored social gathering place, considering it “too dangerous”, highlighting a division that ultimately impedes any process of heritage revitalization that depends on social relations [

14].

In terms of the role that the repurposing of the former Ansaldo factory plays in preserving the industrial and working-class memory of Sampierdarena, the interviews revealed findings that deserve deeper analysis. None of the newer Italian residents interviewed were familiar with the neighborhood’s history. As such, for them, the shopping center does not serve an educational or commemorative function, nor does it carry any meaningful historical significance. On the other hand, among the long-time Sampierdarena residents, there was agreement that the shopping center does not represent the neighborhood’s history and does not serve any commemorative or educational purpose for future generations or for those who are not originally from the area. Nevertheless, the older residents, those who lived through the era when the factory was in operation, see the preservation of the original structure in a positive light.

As for the relationships between the repurposed sites, the residents, and the neighborhood, it is worth noting that while voluntary associations are taking care of the Renaissance villas, the former industrial site’s maintenance is solely in the hands of private investors who repurposed the area for commercial and residential purposes. In fact, the memory of the neighborhood’s industrial past is now entrusted to associations and labor unions that have no direct ties to the Fiumara project, highlighting a significant rift between institutional discourses on heritage (AHD) and the way the local population perceives this heritage (HFB).

While the Renaissance villas and watchtowers are scattered throughout the area, some are entirely abandoned, hidden. For example, a “resident of Sampierdarena for fifty years”, when interviewed, was unaware of the presence of a villa and a watchtower located just a few meters from his home. Moreover, they are often integrated into the subsequent urbanization of the neighborhood: some villas and watchtowers, among those promoted by the municipality and the municipio, are extremely difficult to locate, even using traditional or digital maps, as they are immersed in subsequent urbanization. In addition, the majority of them are privately owned and used for residential purposes, while others, though not attracting large tourist flows (except for certain days during FAI days and a few occasional events), have been restored or are undergoing restoration and are used for civic and educational purposes, hosting schools and exhibitions. These restored sites are considered vital to the community, with local residents frequently visiting them.

These observations suggest that the redevelopment of the former Ansaldo railway factory, contrary to the project’s intentions, has not emerged as a driving force for the neighborhood economically, socially, or in terms of heritage identity. Instead, despite not attracting significant tourist flows and failing to have the desired impact on the local economy, urban development, or real estate market (the commercial value of real estate in the neighborhood of Sampierdarena was and remains extremely low, with no signs of gentrification), the project has exacerbated the social and economic instability of post-industrial Sampierdarena. Furthermore, field research has made it evident that decay and social tensions (or the perception of these issues) have increased, and a clear division has developed between the repurposed site (which is now private property and can be closed off by gates) and its surrounding area, leading to a visible distinction between the new residents in the residential towers and those living in the historic part of the neighborhood.

The analysis of the socioeconomic role of the neighborhood and the residents’ perceptions of the Fiumara project reveals a stark contrast with the Renaissance villas. Despite the lack of a comprehensive strategy to enhance these villas—relying mostly on the underfunded municipality and voluntary associations—and the absence of significant public or private investments, many of these villas have successfully built close relationships with local residents, owing to their civic uses and the associations that promote them. In fact, these villas have become key elements of the community’s heritage, embodying the “external self” [

18] of the community, representing in this way the historical memory and local identity.

From the analysis, it becomes evident that various forces are shaping the present-day identity of Sampierdarena. The official documents regarding heritage revitalization and tourism sustainability of the area portray a narrative of regeneration through heritage, but this narrative rarely aligns with the lived experiences of local residents. This discrepancy highlights a crucial difference between “bottom-up” and “top-down” heritage-making processes, with resulting discrepancies in the functions and values assigned to heritage elements. The urban regeneration of abandoned spaces and the repurposing of industrial relics appear more as strategies to justify private investments and economic interests, with the approval of the municipality and region (through the 1991 PTCP; Comune di Genova 2012), imposing a project that is economically and socially unsustainable for the neighborhood. In fact, there is a noticeable worsening of social tensions and the socioeconomic decline of the area, exacerbated by the closure of many local shops and social spaces (In interviews, older residents frequently mentioned the numerous cinemas once present in the neighborhood, almost in contrast with the new multiplex located in the Fiumara complex). Ultimately, the project is perceived by the neighborhood as an external imposition that does not address its needs, and it is unlikely that it represented the best choice for attracting new tourist flows. This is especially true given that, with far fewer resources, local citizens and institutions have been able to better promote the Renaissance villas.