4.1. Impact of Prediction Duration on Model Performance

This study uses the control variable method for model experimentation, aiming to explore the impact of model input length and prediction length on model performance. By fixing other model parameters, the input length and prediction length are adjusted separately to evaluate their effects on the prediction results. The input length, prediction length, and manually tuned optimal parameter settings for the model are shown in

Table 5.

Multiple control variable experiments were conducted to investigate the impact of input length on the model. In the experiments, the input lengths were set to 24 h, 72 h, 144 h, 192 h, and 240 h, combined with prediction lengths of 4 h, 12 h, 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h. The model accuracy and runtime were compared. As shown in

Table 6, when the input length was 144 h, the model’s overall performance was the best. As the input length increased further, the improvement in model accuracy became more limited, while the training time significantly increased. Therefore, 144 h was chosen as the input length for subsequent experiments.

Through experiments on input length, it was found that when the input length was 144 h, the model exhibited excellent accuracy and runtime performance. To further investigate the impact of prediction length on model performance, a control variable experiment for prediction length was conducted. In the experiment, prediction lengths of 4 h, 12 h, 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h were used, and the results for each prediction length were compared. For the convenience of plotting, the monitoring stations of East Lake Center, Lakeshore, Huanglu, West Lake Center, Xihe Inflow Area, Yuxikou, Zhaohou Inflow Area, and Zhongmiao are represented as Site 1, Site 2, Site 3, Site 4, Site 5, Site 6, Site 7, and Site 8, respectively.

Comprehensive analysis of

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 reveals that the prediction performance of the Informer model for various water quality parameters at different stations decreases with the increase in prediction duration, characterized by an increase in RMSE and a decrease in R

2. The details are as follows:

- (1)

For DO, the average RMSE is 1.105, with a maximum value of 1.822 (Station 6) and a minimum value of 0.606 (Station 1); the average R2 is 0.634, with a maximum value of 0.890 (Station 7) and a minimum value of 0.426 (Station 6). As the prediction duration increases, the prediction performance of DO gradually decreases: RMSE increases from 0.606 to 1.822, with an average increase of 43.46%; R2 decreases from 0.890 to 0.426, with an average decrease of 43.40%.

- (2)

For CODMn, the average RMSE is 0.517, with a maximum value of 0.720 (Station 5) and a minimum value of 0.267 (Station 3); the average R2 is 0.680, with a maximum value of 0.924 (Station 3) and a minimum value of 0.471 (Station 6). With the extension of prediction duration, the prediction performance of CODMn gradually declines: RMSE rises from 0.267 to 0.720, with an average increase of 34.58%; R2 drops from 0.924 to 0.471, with an average decrease of 37.21%.

- (3)

For TP, the average RMSE is 0.016, with a maximum value of 0.033 (Station 5) and a minimum value of 0.005 (Station 3); the average R2 is 0.668, with a maximum value of 0.912 (Station 4) and a minimum value of 0.342 (Station 1). As the prediction duration increases, the prediction performance of TP gradually deteriorates: RMSE increases from 0.005 to 0.033, with an average increase of 49.61%; R2 decreases from 0.912 to 0.342, with an average decrease of 45.76%.

- (4)

For TN, the average RMSE is 0.206, with a maximum value of 0.339 (Station 4) and a minimum value of 0.110 (Station 6); the average R2 is 0.724, with a maximum value of 0.939 (Station 6) and a minimum value of 0.486 (Station 7). With the increase in prediction duration, the prediction performance of TN gradually decreases: RMSE increases from 0.110 to 0.339, with an average increase of 39.07%; R2 decreases from 0.939 to 0.486, with an average decrease of 39.54%.

Overall, in the predictions with durations of 4 h, 12 h, 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h, the model performance declines significantly with the increase in duration, with an average increase of 41.68% in RMSE and an average decrease of 41.48% in R2.

Comprehensive analysis of

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 shows that the model maintains good prediction performance during the 4 h to 12 h period; while in the 24 h to 72 h period, due to the error accumulation effect, its performance gradually declines, with the prediction accuracy at 72 h decaying particularly significantly. At the parameter level, the prediction performance of DO and CODMn remains stable; TP and TN, however, exhibit a prominent increase in long-term prediction errors due to their high environmental sensitivity. At the station level, Stations 8 and 2 show good prediction stability, Station 5 performs the best, while Stations 1 and 3 are relatively poor. Overall, the model’s prediction performance is significantly negatively correlated with the time dimension, declining gradually as the prediction cycle extends, and the decay is more obvious under longer prediction durations. Although manual parameter tuning can slightly improve performance, it has the limitations of heavy workload and limited effectiveness.

4.2. The Impact of Optimized Algorithms on the Model

From the results in

Section 4.1, it can be seen that the prediction performance of the Informer model decreases as the prediction duration increases, with a more significant decline after 48 h. Although manual parameter tuning can slightly improve performance, it has the problems of heavy workload and limited effectiveness. To avoid unreasonable parameter settings limiting model performance, the Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) is introduced to optimize the key hyperparameters of Informer, aiming to find optimal parameter combinations that maximize prediction capability. The parameter settings of WOA are shown in

Table 7.

In

Table 7, hunting_party represents the size of the whale population (i.e., the number of solutions); spiral_param is the spiral parameter that controls the whale’s spiral movement; mu is a parameter related to the reproduction process; min_values and max_values represent the minimum and maximum values of the solution space; iterations refers to the number of iterations. The WOA is used to optimize the parameters of the Informer model, and the function accepts five parameters (X1, X2, X3, X4, X5), which represent the hyperparameters of the Informer model. Their specific roles are as follows: X1 is used to calculate d_model, controlling the model’s dimensionality; X2 is used to set dropout, which is the dropout rate applied during training to prevent overfitting; X3 is used to set d_ff, which is the hidden layer dimensionality of the feed-forward neural network; X4 is used to set e_layers, which represents the number of encoder layers; X5 is used to set d_layers, which represents the number of decoder layers.

After optimizing the hyperparameters of the Informer model using the Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA), the best parameter configuration was obtained. After performing a global automatic search for the optimal combination of X1, X2, X3, X4, and X5 with the WOA, the water quality time-series data was predicted, and the prediction results are as follows.

Through the analysis of

Figure 7 and

Figure 8, the Informer model optimized by the Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) (WOA-Informer) has achieved significant improvements in the RMSE metrics for predicting the water quality parameters DO, CODMn, TP, and TN in Chaohu Lake. The specific performance is as follows:

In DO prediction, compared with the original Informer model, WOA-Informer reduced the RMSE by an average of 11.60% (4 h), 11.76% (12 h), 9.89% (24 h), 8.98% (48 h), and 11.07% (72 h) across Stations 1–7. The maximum reduction at each time point occurred at Station 6 (26.30% at 4 h, 33.72% at 12 h, 42.89% at 24 h, 50.24% at 48 h, 47.26% at 72 h), while the minimum reductions were concentrated at Station 5 (6.18% at 4 h, 3.74% at 12 h, 3.15% at 72 h) and Station 3 (1.77% at 48 h).

For CODMn prediction, the average RMSE reduction rates of WOA-Informer were 7.75% (4 h), 3.21% (12 h), 4.71% (24 h), 7.46% (48 h), and 9.80% (72 h). The maximum reductions were observed at Station 6 (12.68% at 4 h), Station 1 (5.49% at 12 h), and Station 5 (10.96% at 24 h, 50.24% at 48 h, 22.50% at 72 h). The minimum reductions were at Station 7 (1.55% at 4 h), Station 8 (0.66% at 12 h, 2.39% at 48 h), Stations 1–2 (1.95% at 24 h), and Station 4 (3.95% at 72 h).

In TP prediction, the average RMSE reduction rates were 12.44% (4 h), 14.97% (12 h), 10.98% (24 h), 10.01% (48 h), and 14.44% (72 h). The maximum improvements were at Station 3 (20.00% at 4 h, 25.00% at 24 h, 25.00% at 48 h), Station 8 (28.57% at 12 h), and Station 7 (17.65% at 72 h). The minimum reductions were at Stations 4–5 (6.25% at 4 h), Station 5 (4.55% at 12 h, 3.85% at 24 h, 3.45% at 48 h), and Station 6 (10.00% at 72 h).

For TN prediction, the average RMSE reduction rates were 6.01% (4 h), 5.09% (12 h), 5.57% (24 h), 7.71% (48 h), and 11.90% (72 h). The most significant improvements were at Station 1 (10.46% at 4 h) and Station 7 (12.42% at 12 h, 22.93% at 24 h, 15.15% at 48 h, 19.17% at 72 h). The minimum reductions were at Station 8 (1.82% at 4 h), Station 5 (1.54% at 12 h), Station 2 (1.27% at 24 h), Station 6 (4.29% at 48 h), and Station 3 (9.09% at 72 h).

In summary, WOA-Informer significantly improved the prediction performance of water quality parameters across different monitoring stations and prediction durations, fully verifying the effectiveness of the WOA in optimizing the overall prediction capability of the Informer model.

Analysis of

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 reveals that the Informer model optimized by the WOA (WOA-Informer) has significantly improved the prediction performance of Chaohu Lake’s water quality parameters (DO, CODMn, TP, and TN) in terms of the R

2 metric. The performance of each parameter across different stations and prediction durations is as follows:

In DO prediction, the R2 values of WOA-Informer showed an average increase of 4.51%, 8.81%, 14.10%, 16.08%, and 23.52% in the 4 h, 12 h, 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h predictions at Stations 1–7, respectively. Specifically, the R2 (4 h) at Station 1 increased from 0.860 to 0.875, and the R2 (72 h) significantly improved from 0.427 to 0.572; the R2 (72 h) at Stations 2 and 7 increased by 25.96% (0.447→0.563) and 21.6% (0.494→0.601), respectively; the R2 (4 h) at Station 6 rose from 0.822 to 0.924, with the 72 h R2 increasing by 12.42%.

For CODMn prediction, the R2 of WOA-Informer increased by an average of 6.56% (4 h), 7.27% (12 h), 13.17% (24 h), 17.93% (48 h), and 18.22% (72 h) under the same stations and durations. The maximum increase at each duration occurred at Station 6 (15.78% at 4 h, 22.74% at 12 h, 36.83% at 24 h, 37.67% at 48 h, 28.24% at 72 h); the minimum increases were concentrated at Station 3 (0.54% at 4 h), Station 5 (0.009% at 12 h, 1.95% at 24 h, 9.39% at 72 h), and Station 1 (6.40% at 48 h).

In TP prediction, the R2 of WOA-Informer increased by an average of 2.23% (4 h), 5.57% (12 h), 12.91% (24 h), 27.82% (48 h), and 30.12% (72 h). The maximum increases at each duration were observed at Station 6 (8.39% at 4 h, 10.45% at 12 h) and Station 1 (29.58% at 24 h, 57.07% at 48 h, 58.19% at 72 h); the minimum increases were concentrated at Station 4 (0.44% at 4 h, 2.69% at 24 h), Station 2 (0.47% at 12 h), and Station 7 (3.80% at 48 h, 8.52% at 72 h).

For TN prediction, the R2 of WOA-Informer increased by an average of 1.89%, 2.30%, 4.74%, 7.64%, and 21.17% in the 4 h, 12 h, 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h predictions at Stations 1–7, respectively. Specifically, the R2 (72 h) at Station 1 increased from 0.517 to 0.681 (a 31.7% improvement); the R2 (72 h) at Station 3 rose from 0.569 to 0.690 (a 21.3% increase); the R2 at Station 2 showed a steady improvement with extended prediction durations (e.g., from 0.860 to 0.896, an increase of 4.19%); the R2 (4 h) at Station 6 slightly increased to 0.939, with a smaller rise in long-term predictions, which may be related to the stable TN concentration at this station and its low susceptibility to external interference.

In summary, WOA-Informer significantly improved the R2 values in predicting all water quality parameters, and the improvement amplitude generally increased with extended prediction durations, fully verifying the effectiveness of the WOA in optimizing model performance.

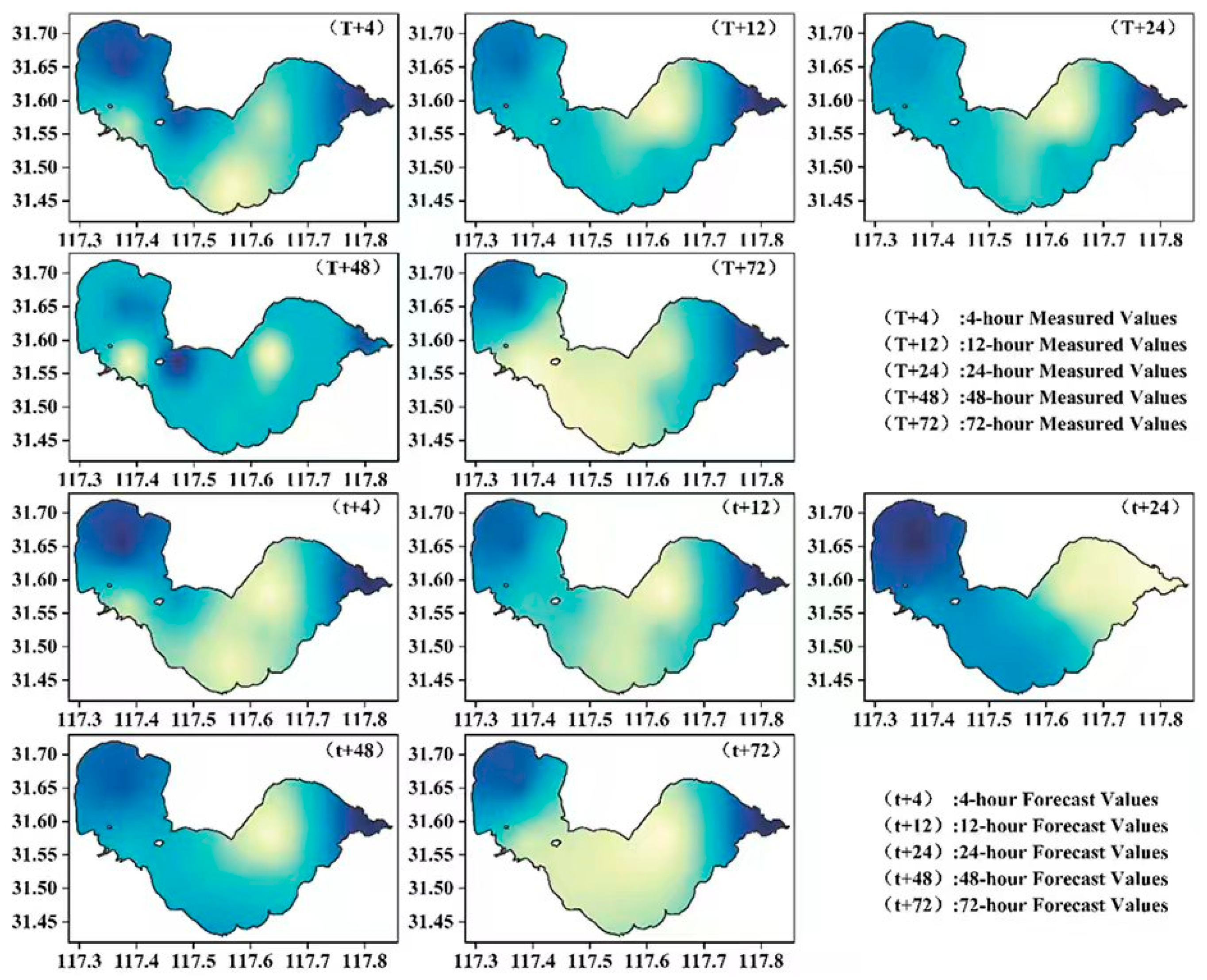

In summary, after optimizing Informer parameters via the Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA), the WOA-Informer model maintains stable performance in short-term time series prediction and achieves significant improvements in long-term time series prediction. The prediction accuracy of dissolved oxygen (DO), permanganate index (CODMn), total phosphorus (TP), and total nitrogen (TN) has been enhanced, among which DO and TP, which exhibit strong time series variability, show the most significant improvements. For the 72 h prediction duration, the model’s R2 metrics have all improved, indicating that WOA can enhance the model’s ability to extract temporal characteristics of water quality and significantly improve the prediction accuracy of long-term water quality evolution trends. Therefore, to study the future evolution trends of Chaohu Lake’s water quality parameters, the trained WOA-Informer model is used to predict the future time series of Chaohu Lake’s water quality, clarify its evolution trends, and provide a basis for formulating targeted rectification measures, controlling the concentrations of water quality parameters, and thereby improving the water quality of Chaohu Lake.