Abstract

Urban horticulture as a segment of urban agriculture can take various forms: home gardens, allotment farming, community gardens, community-supported agriculture, vertical farming, etc. After the COVID-19 pandemic in Croatia and neighboring countries, growing horticultural plants in urban and suburban areas became increasingly popular. The aim of the study was to investigate citizens’ attitudes towards the benefits and support of urban horticulture, its relationship to the environment, and needs and relevance in studies in the cities of Šibenik, Split, Mostar and Skopje. The research methods used for the purpose of this study were theoretical analysis method, survey and analytical descriptive and statistical method. The research was conducted online during the first half of 2024 on a sample of 506 respondents. The main goal of the paper was to examine the views of citizens on urban horticulture. With specific objectives, the views of citizens were examined on the benefits of urban horticulture, the relationship between urban horticulture and the environment, urban horticulture and plant protection, support for urban horticulture, and the needs and trends of urban horticulture. and plant protection, support for urban horticulture, needs and trends of urban horticulture. The results showed that citizens are mostly positive towards growing horticultural plants in urban and suburban areas without pollution. In urban horticulture, respondents prefer using ecological principles and products. Female respondents expressed more positive attitudes towards the fashionability and need for urban horticulture. Respondents from Skopje showed the most positive attitudes towards the benefits of urban horticulture and its relationship to the environment. Also, there is no statistically significant difference in attitudes towards urban horticulture with regard to the location of residence. The research contributes to the trend of development and promotion of urban horticulture with a special emphasis on the importance of environmental preservation. It also contributes to the development of an interdisciplinary method that connects natural and social sciences, and develops an empirical approach that can improve urban culture with the aim of preserving the environment.

1. Introduction

Before industrialization, people living in urban areas met their food needs through planting in urban gardens. Urban horticulture is more flexible for urban areas than livestock farming or grain production. Therefore, the current movement is usually identified as part of the field of urban horticulture [1]. For example, the National Urban Agriculture Program in Cuba was launched in 1993 with the aim of encouraging food production in available urban and peri-urban spaces, utilizing available labor and the immediate proximity of producers and consumers [2].

During the period of industrialization, residents originally from rural areas also continued the trend of urban agriculture, which mainly served as a second income or a supplement to the household budget. This trend persisted not only in Croatia but also in neighboring countries until the 1990s, when the socio-political system changed. It continued afterwards, but with less scope and intensity.

Urban areas have suitable potential for food production through urban horticulture, but there remain questions about the availability of space for its expansion and how to sustainably integrate it into the current urban fabric [3]. International policy makers have recognized the importance of urban and peri-urban vegetable production for improving the supply of vitamins and micronutrients, and have placed it high on the political agenda [4,5,6].

Horticulture is largely represented within research on urban agriculture. The interest is motivated by eco-technical challenges, e.g., improving household nutrition in mega-cities, closing urban waste cycles through agriculture, and exploring “smart” options for low-carbon fruit and vegetable production [7].

In the area of Central Dalmatia (Zadar, Šibenik, Split, etc.), urban horticulture has supplied not only city markets but also the tourism sector since the 1950s, and such products have always been more valued by consumers. In most cases, there was reduced or no use of agrochemicals. The products were recognizable for their seasonal character, excellent taste and aroma, and reasonable price.

Urban horticulture can take various forms (unlike most conventional food production systems). Besides commercial production, it can include: home gardens, allotments, community gardens, community-supported agriculture, vertical plant cultivation [8]. Urban agriculture—which includes urban horticulture—primarily refers to the cultivation of plants and animals for personal needs, and less for sale on the market [9].

Raising livestock for household needs in the city of Šibenik, especially pigs, donkeys, poultry, and rabbits, has been prohibited for several decades. The last decision on the ban on keeping livestock in the city was in 1972–1973. Sporadic and small-scale keeping of poultry and other domestic animals in the wider urban area and city outskirts was somewhat tolerated until the late 1990s.

For a long time, urban horticulture was synonymous with a marginal activity for elderly people, retirees, or as an occasional pastime. In the context of postmodern society, horticulture is increasingly popular and visible, and is used for educational and rehabilitative purposes or simply as a hobby [10]. Urban horticulture is also a recreational activity, and as such, has been the subject of some research; in recent years, it has seen growth. The potential role of urban horticulture in improving food security and the physical and mental health of urban populations became evident after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic [11].

The COVID-19 pandemic deprived citizens of social contact and mobility, so for some, the garden served as a form of relaxation and mental well-being.

Home gardens, community plots, vertical gardens, permaculture gardens, and urban farms all contribute to the vision of vibrant, healthy, and sustainable urban landscapes where food production and ecology are intertwined [12].

Today, the term “edible landscaping” is used, which refers to using vegetables, herbs, fruits, and flowers to perform multiple roles (food, flavor, and decorative appearance) [13]. Gardens in parks offer citizens a connection with nature through various gardening activities with the goal of harvesting produce [14]. Urban landscapes in a sustainable city are viewed through three pillars of benefits: ecological, social, and economic well-being [15,16].

Such landscapes, aside from being innovative and creative, promote biodiversity, which is currently reduced in urban environments; this particularly applies to urban songbirds [17].

It is necessary to take into account that urban food production carries health and environmental risks if not managed properly [18]. As urban horticulture activities grow, understanding the quality of urban horticultural soils becomes increasingly important [19].

Horticultural production in urban and peri-urban areas can recycle waste into productive resources. In some developed countries, municipal plants recycle organic waste and offer it to citizens as compost for gardens. The use of wastewater in horticulture is more problematic because pathogens from vegetables grown with untreated wastewater can cause digestive diseases [20]. Hydroponic technology can be significant in maximizing food production while also reducing the risk of insects. Hydroponics is highly productive, can be automated, and is ideal for areas where conventional agriculture is impossible (lack of water, degraded or contaminated land) [21].

Today, urban horticulture plays an important role in urban planning—not only in the food supply chain but also in enhancing the esthetic value of areas, environmental conditions, landscapes, and the business environment, while reducing fossil fuel use in transportation [22]. Ultimately, the establishment of urban gardens is effective in the regeneration and repurposing of degraded urban areas [23]. Rubić and Zrnić (2018) [24] state that in Croatia, the concept of urban gardens has been considered since 2012. Urban gardens have produced excellent results only where exceptional enthusiasm of individuals driving the idea has been recorded, where they have had the support and understanding of local authorities, and where there is great public interest in using cultivable plots [25].

Urban agriculture/horticulture in Croatia has been in fashion for the last ten years, but it has existed for much longer and its development is not lagging behind urban agriculture in European and world cities. For example, the City Gardens in Zagreb appeared as early as the 1870s, the Bulgarian Gardeners, and the organization of illegal urban gardens began in the 1990s in the Zagreb neighborhood of Travno. They were closed in 2013 for the purpose of revitalization. The biggest obstacle to the spread of such agriculture in the world is the conversion of land into construction zones [25]. In addition to Zagreb, city gardens have been established in Varaždin, Karlovac, Samobor, Rijeka, Osijek, Virovitica, etc.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, agriculture is most developed in rural areas. In cities, the development of urban horticulture relies on enthusiastic citizens and project activities of non-governmental organizations. Thanks to this, a number of initiatives such as “American Friends Committee” (AFSC) where plots for planting plants are secured, Mojmilo urbana agriculture-Establishment of urban gardens in Sarajevo (Novi Grad Municipality), Reconstruction of green areas in the kindergarten “Mladost” in Kakanj and the holding of interactive workshops growing plants, forming flower beds in the Planet Montessori kindergarten in Mostar, etc. [26].

In the area of the city of Mostar, in recent decades, through various associations, citizens educate for work in agriculture. The above is important because we want to help the vulnerable as well groups in the community [9].

The origins of urban horticulture in North Macedonia remain unclear. However, it is evident that with the process of urbanization, urban horticulture has assumed an increasingly significant role. Historically, horticultural activities were more prevalent in peri-urban areas surrounding major cities. At present, traditional forms of urban gardening, such as home gardening and community gardening, continue to exist—although only one community garden has been established so far, located in the capital city, Skopje.

In urban areas in Skopje, there are many houses that have free yard space of 200–400 m2. All horticultural crops can be found in the same spot. Some of the gardens are unplanned, but most follow architectural and horticultural principles [27].

The specific objectives were related to examining statistical differences in attitudes towards the benefits of urban horticulture, the relationship between urban horticulture and the environment, urban horticulture and plant protection, supporting urban horticulture, and the needs and trends of urban horticulture. and plant protection, supporting urban horticulture, the needs and trends of urban horticulture with respect to: gender, age, place of residence, location of residence, and level of education.

The paper is of a theoretical-empirical character and consists of a theoretical part, methodological part and analysis, interpretation, and discussion of research results. In the theoretical part, scientific works related to the topic of harvested horticulture are discussed. The methodological part was based on the definition of methods, techniques, instruments and statistical procedures that were used in the work. Through analysis, interpretation and discussion, the data were tabulated and described using the descriptive-analytical method.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Object

2.1.1. Urban Horticulture in the Area of City Šibenik

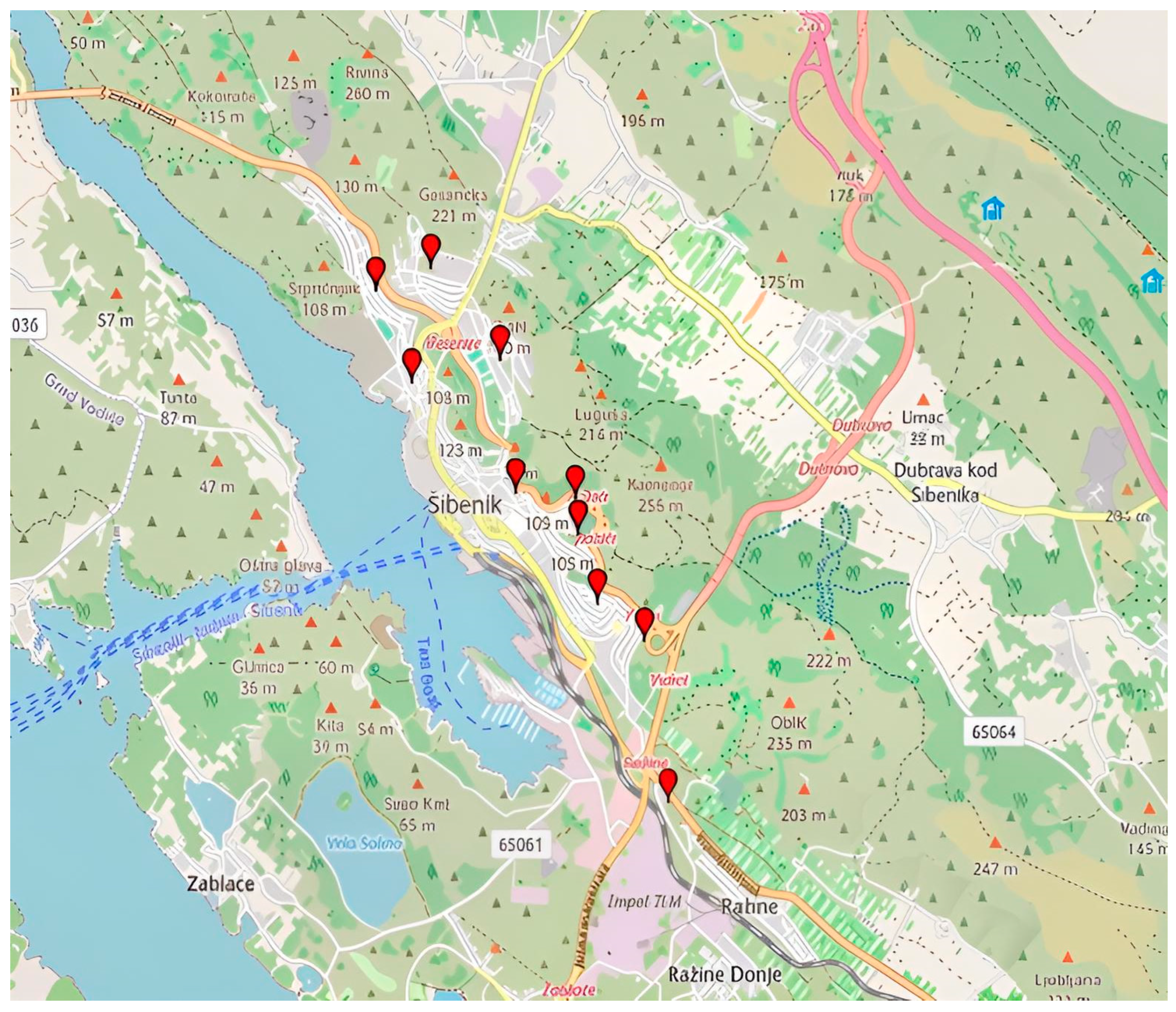

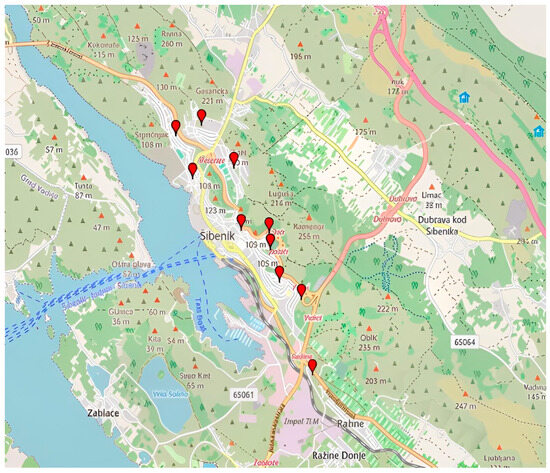

In the city of Šibenik, urban horticulture-plant cultivation is most developed in the areas of Crnica and Njivice, city districts located in the far western part of the city, and the Ražine neighborhood in the eastern part of the city. Before the Homeland War, vegetables and fruits from these parts of the city were quite common at the Šibenik market. Today, the population is more oriented towards cultivation for their own needs. In these parts of the city, small private gardens with vegetable, fruit, and ornamental crops prevail, used to meet household needs. Overall, the gardens do not have high design characteristics. In Šibenik, a larger number of private gardens with vegetable, fruit, and ornamental crops can also be found in the areas of Mažurice, Rokići, Škopinac, Šubićevac, Meterize, Križ, and Vidici, with the yield used by residents for their own needs. Horticultural production should be based on quality, local products and cultivars (e.g., Šibenik tomato, Šibenik melon, etc.), and the sale of produce and processed goods through tourism. The most significant localities under urban horticulture in Šibenik are given in Figure 1. Figure 2 shows family garden in Šibenik—Njivice.

Figure 1.

The most significant localities under urban horticulture in Šibenik (Created by: Pavao Gančević, 2025 in GPS Visualizer). List of marked locations on the map with coordinates: Crnica (43.7423780, 15.8886552), Njivice (43.7487463, 15.8846426), Mažurice (43.7316743, 15.9067762), Rokići (43.7341531, 15.9064651), Škopinac (43.7346533, 15.8998775), Šubićevac (43.7439267, 15.8982682), Vidici (43.7240586, 15.9139538), Ražine (43.7128428, 15.9165502), Križ (43.7268365, 15.9089327).

Figure 2.

Family garden—Šibenik—Njivice (Photo: Boris Dorbić, 2025).

2.1.2. Urban Horticulture in the Area of City Split

The existence of gardens and parks in medieval Split is confirmed by the Statute of the City of Split from that period, which clearly distinguished between terms garden and park (Latin ortum and zardinum) [28]. During the 1980s, significant horticultural production took place in Split area in protected spaces (greenhouses and glasshouses), with around 25,000 tons of vegetables produced annually in off-season production and about 60 million units of cut flowers [29].

In the present period, the City of Split is characterized by a high level of urban development with a lack of green areas, which are mostly arranged as park spaces and similar public areas. The dominant green area is the Marjan forest park, located in the western part of the city. The central part of the city lacks green spaces due to the high degree of urbanization. Development in the eastern part of the city mainly consists of family houses with yards, where horticultural production is still practiced. Since city expansion is planned in this area, it is expected that green spaces in this part of the city will decrease in the future.

The most significant sites with urban horticulture in Split are the following: Meje—the southern side of Marjan forest park, Pazdigrad, Sirobuja, Stobreč, and Mostine (Figure 3). Figure 4. shows urban horticulture in Split—southern side of the Marjan forest park The most significant parks are The City Park (Đardin) and The Emanuel Vidović Park. Additionally, the palm tree avenue along the seafront promenade (Riva) is one of the most recognizable symbols of Split.

Figure 3.

The most significant localities under urban horticulture in Split (Created by: Pavao Gančević, 2025 in GPS Visualizer). List of marked locations on the map with coordinates: Meje (43.5050589, 16.4193892), Pazdigrad (43.5073484, 16.4925814), Sirobuja (43.5051533, 16.5096188), Stobreč (43.5038928, 16.5233088), Mostine (43.5230685, 16.4941907).

Figure 4.

Urban horticulture in Split—southern side of the Marjan forest park (Photo: Josip Gugić, 2025).

2.1.3. Urban Horticulture in the Area of Mostar

From a historical perspective, urban horticulture has undeniably played a significant role in the lives of Mostar’s residents. Private gardens, where horticultural crops were grown, were a common sight in Mostar, and it is interesting to note that the local population has nurtured a tradition of planting indigenous species of fruit, vegetables, as well as herbs and ornamental plants for generations. The old neighborhoods of Mostar known in the 1970s and earlier for their private gardens include Bjelušine, Mahala, Luka, Podhum, Šemovac, Strelčevina, Behlilovac, Mazoljice, and others, with Ilići serving as the center of horticultural production. By tradition, part of the local population continued the production practices of their ancestors, but for their own needs, so garden spaces were always found next to residential buildings.

In addition to this, there were production zones for food products intended for commercial purposes: Jasenica, Rodoč, Cim, Bijelo Polje, Bare, etc. This practice served as an economic benefit for household subsistence. The local population was characterized by a spirit of mutual assistance during planting or harvest time.

In Mostar’s tradition of horticultural cultivation, the main crops were potatoes, onions, peas, beans, cabbage, green lettuce, as well as winter horticultural species such as leeks and garlic, while private yards were used for ornamental and herb gardens. Among the herbs and medicinal plants that adorned private gardens in Mostar’s tradition, notable examples include mint, rosemary, parsley, celery, lemon balm, basil, houseleek, wormwood, sage, elderberry, and roses known as đul behara. Among the fruit crops, the most prominent were fig, pomegranate, peach, apricot, cherry, sour cherry, and persimmon.

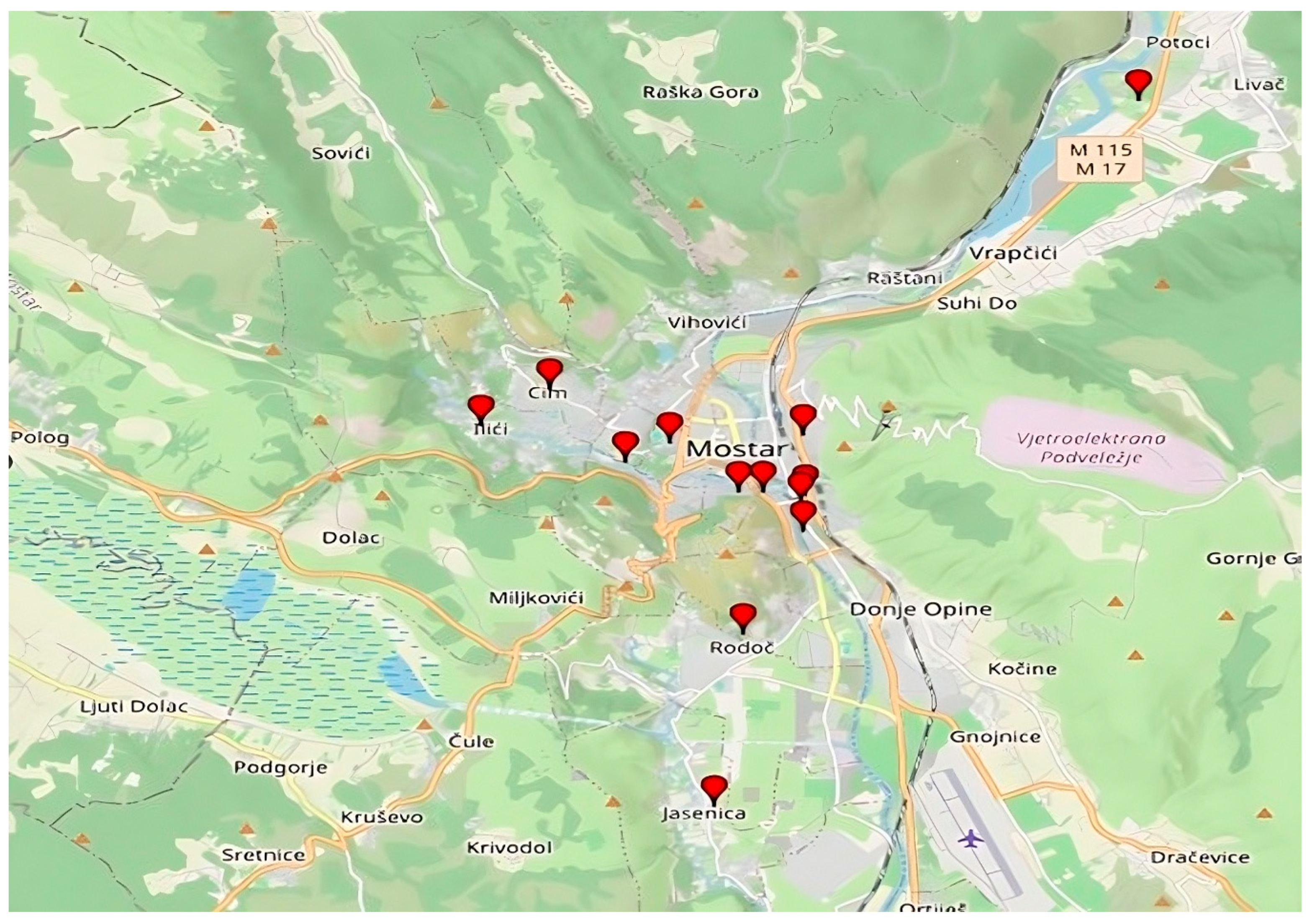

Unfortunately, this is no longer the practice today. From that period to the present day, due to population growth, migration, and urban needs, most agricultural/cultivable land has been covered by infrastructural developments: residential, industrial, and commercial buildings. Well-known locations where private gardens have mostly been converted into parking spaces can also be found, all due to the growth of tourism. However, the strong imprint of tradition, passed down from generation to generation, is still influential, and horticultural production continues, but rarely for subsistence—rather recreationally, alongside regular other sources of income. Many indigenous plant varieties have become extinct or are on the brink of extinction, but the passion of enthusiasts is trying to preserve well-known local varieties: the Mostar apricot, Ilići tomato, Žilavka vine, local peaches, persimmon, and various pomegranate varieties, among which Glavaš and the old Medun stand out, as well as fig varieties such as Petrovača and Tenica. The most significant localities under urban horticulture in Mostar are given in Figure 5. Figure 6 shows Mostar-Mazoljice private gardens.

Figure 5.

The most significant localities under urban horticulture in Mostar (Created by: Esmera Kajtaz, 2025 in GPS Visualizer). List of marked locations on the map with coordinates: Podhum (43.3366384, 17.8076402), Mazoljice (43.3456557, 17.8176408), Šemovac (43.3367323, 17.8116747), Bjelušine (43.3361395, 17.8181129), Bare (43.3413544, 17.7901346), Luka (43.3349018, 17.8172728), Strelčevina (43.3443581, 17.7971894), Donja Mahala (43.3303707, 17.8177753), Cim (43.3528978, 17.7786319), Ilići (43.3470327, 17.7679874), Bijelo Polje (43.3985683, 17.8696553), Rodoč (43.3142273, 17.8085317), Jasenica (43.2870014, 17.8040679).

Figure 6.

Mostar-Mazoljice private gardens (Foto: Esved Kajtaz, 2025).

2.1.4. Urban Horticulture in the Area of Skopje

Urban horticulture in Skopje is practiced in various locations throughout the city, particularly along the banks of the Vardar River. Many residential properties have sufficient yard space, which is commonly utilized for the cultivation of horticultural crops, primarily for household consumption. Some of households produce quantities of food that exceed their own consumption needs and therefore sell the surplus either at local green markets or directly from their homes. This practice intensified during the COVID-19 pandemic, when the necessity of producing household food supplies became evident, both to ensure self-sufficiency and to generate additional income. The productive areas of these gardens are typically situated at the rear of the houses, where a wide range of vegetables—mainly traditional and local cultivars—are grown.

Fruit trees are also commonly found throughout these urban gardens. They are often planted in the backyards, along garden fences, or even in the front yards, where species such as kiwi and grapevines are frequently grown on pergolas. The front areas of homes are usually reserved for ornamental plants and flowers, serving mainly decorative purposes.

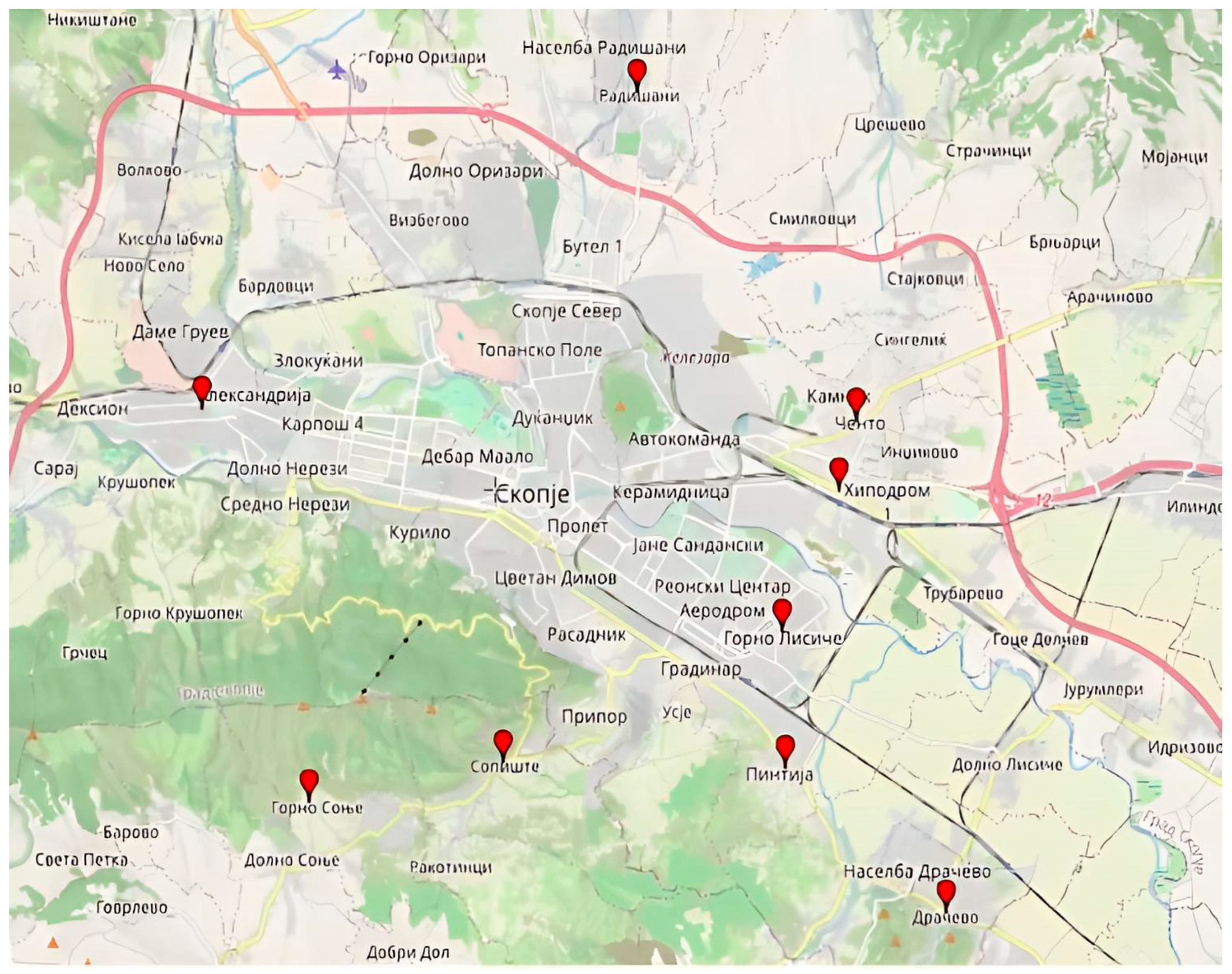

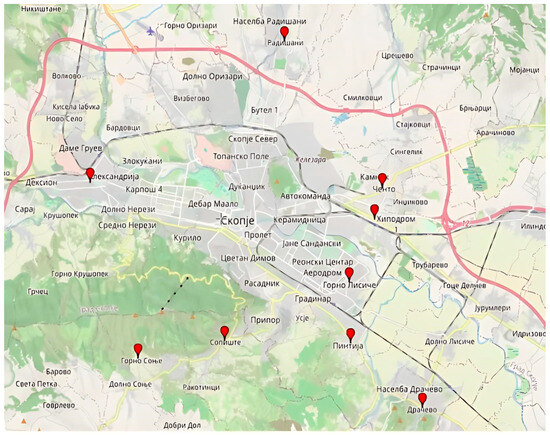

Urban gardens are widespread in several neighborhoods and suburban settlements, including Gjorche Petrov, Radishani, Sopishte, Gorno Sonje, Drachevo, Lisiche, Pintija, Chento, and Madzari (Figure 7). Figure 8 shows urban garden in the settlement Gjorche Petrov. A noteworthy recent development is the establishment of the community garden Bostanie in the Novo Lisiche settlement within the Aerodrom Municipality. This garden operates on the principles of permaculture and is maintained by local residents on a voluntary basis, with a focus on vegetable production.

Figure 7.

The most significant localities under urban horticulture in Skopje (Created by: Esmera Kajtaz, 2025 in GPS Visualizer). List of marked locations on the map with coordinates: Radishani (42.0556607, 21.4544964), Sopishte (41.9551762, 21.4253569), Gorno Sonje (41.9492134, 21.3832569), Pintija (41.9544345, 21.4866829), Madzhari (41.9958906, 21.4984846), Chento (42.0065660, 21.5024757), Drachevo (41.9325502, 21.5218735), Gjorche Petrov (42.0082351, 21.3596535), Gorno Lisiche (41.9746864, 21.4861679).

Figure 8.

Urban garden in the settlement Gjorche Petrov (Photo: Zvezda Bogevska, 2025).

2.2. Survey Research and Research Hypotheses

The research sample related to attitudes towards urban horticulture (n = 506) was heterogeneous and consisted of respondents from Šibenik and Split (n = 155), Skopje (n = 198), and Mostar (n = 153). The gender structure of the respondents was expressed in the ratio of 141 (male respondents) to 365 (female respondents). Due to the wide age range of respondents (from 15 to 84 years), three categories were created. The first age category included respondents aged 15 to 37 (n = 217), the second category aged 38 to 60 (n = 237), and the third category aged 61 to 84 (n = 52). Due to the nature of the research topic, the places of residence were also included: city center (n = 141), wider city area (n = 210), urban periphery (155). Regarding the level of education, respondents could choose one of five categories: unskilled (no schooling, incomplete primary school), primary school, secondary school diploma, higher education diploma, or university degree (undergraduate degree, academy, master’s, doctorate). The following were included in the analysis: unskilled (n = 1), primary school (n = 5), secondary school diploma (n = 112), higher education diploma (n = 56), and university degree, academy, master’s, or doctorate (remaining respondents).

The research methods used in this paper were: theoretical analysis, survey method, and analytical-descriptive and statistical methods.

The research was conducted online during the first half of 2024 using a Google Forms questionnaire consisting of five dimensions and a questionnaire related to sociodemographic data needed for detailed statistical analysis. The dimensions examined in this study were: benefits of urban horticulture (11 items), urban horticulture and the environment (10 items), urban horticulture and plant protection (9 items), support for urban horticulture (11 items), and needs and trends in urban horticulture (10 items). Respondents is in the form of a Likert scale were offered five response options to express their opinion: (1) strongly disagree, (2) mostly disagree, (3) neither agree nor disagree, (4) mostly agree, (5) strongly agree.

The online survey was anonymous, and respondents were informed that the study was for scientific purposes and asked to be as honest and objective as possible in their answers to ensure the accuracy and objectivity of the research results. After the survey was conducted, the collected data were recorded and analyzed in IBM SPSS software, version 26. The analysis used descriptive statistical procedures (frequencies) and non-parametric statistics (Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis tests). The total scores of the mentioned dimensions were analyzed. Higher scores indicate more positive attitudes, while lower scores indicate more negative attitudes.

2.3. Study Hypotheses

H1.

There is a statistically significant difference in attitudes toward the benefits of urban horticulture, the relationship between horticulture and the environment, urban horticulture and plant protection, support for urban horticulture, and the needs and trends of urban horticulture with respect to gender.

H2.

There is a statistically significant difference in attitudes toward the benefits of urban horticulture, the relationship between horticulture and the environment, urban horticulture and plant protection, support for urban horticulture, and the needs and trends of urban horticulture with respect to age.

H3.

There is a statistically significant difference in attitudes toward the benefits of urban horticulture, the relationship between horticulture and the environment, urban horticulture and plant protection, support for urban horticulture, and the needs and trends of urban horticulture with respect to the place of residence.

H4.

There is a statistically significant difference in attitudes toward the benefits of urban horticulture, the relationship between horticulture and the environment, urban horticulture and plant protection, support for urban horticulture, and the needs and trends of urban horticulture with respect to the location of residence.

H5.

There is a statistically significant difference in attitudes toward the benefits of urban horticulture, the relationship between horticulture and the environment, urban horticulture and plant protection, support for urban horticulture, and the needs and trends of urban horticulture with respect to the level of education.

3. Results and Discussion

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics data and shows that for each of the stated variables, the distribution is positively skewed and leptokurtic. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test indicates that the deviation from normal distribution is statistically significant (p < 0.05) for all variables. Since the deviation from the normal distribution is statistically significant for all variables, non-parametric statistical procedures were used for the statistical analysis.

Table 1.

Arithmetic mean, Standard deviation, Skewness, Kurtosis, and Normality test results.

The mean values in Table 1 range between 2.83 and 2.94, indicating that respondents most often chose answers close in value to the modality 3 (neither agree nor disagree). It can also be added that there is a certain level of reservation and slight disagreement, as the results, although close to 3, are still slightly below that value.

Based on the average values in Table 2, it can be observed that respondents generally support: the cultivation of horticultural plants in urban and peri-urban areas under pollution-free conditions, the cultivation of horticultural plants in greenhouses as part of urban horticulture, the cultivation of horticultural plants in cities which positively affects biodiversity, the cultivation of horticultural plants in cities which positively influences the human environment and climate, the use of ecological principles and preparations in urban horticulture, the cultivation of ornamental plants within urban horticulture, the cultivation of vegetables within urban horticulture, the cultivation of fruit within urban horticulture, and the cultivation of medicinal and aromatic herbs within urban horticulture. Respondents also generally agree that pesticides introduced into the soil by human activity reach the plant and, through karst systems, enter drinking water; that urban farmers need the help of agronomy experts specializing in plant protection; and that rooftop gardens for growing horticultural plants are still rare in their area.

Table 2.

Arithmetic mean, Standard deviation, and Topics of urban horticulture.

Today’s urban agriculture movement is an example of ethics in the field of social responsibility, which is essential for the sustainability of agriculture [1]. Urban horticulture is not suitable for every area due to the risk of contamination. Instead of prohibiting or restricting it, it should be seen as an adaptation challenge—adjusting cultivation to given circumstances and taking precautions to ensure food products are safe [30]. Urban horticulture not only contributes to local food production but also improves urban biodiversity, affects air quality, and shapes green spaces [12]. Today, over 200 cities have signed the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact, committing to increasing urban growing areas, and nearly 1.000 cities worldwide have pledged ambitious climate action plans [8].

Some agricultural schools in the region are an excellent example of urban vegetable production. For example, one school in Serbia (students and teachers) produces about 15,000 tomato seedlings and 10,000 pepper seedlings in a greenhouse. This production achieves twice the financial profit compared to the invested amount [31]. Youth gardens can reduce stress, improve attitudes and relationships towards school and peers, enhance cooperation and teamwork, and boost self-efficacy and self-esteem, among other benefits [32].

Opinions with which respondents mostly disagree or remain reserved include: media attention given to urban horticulture, encouragement of urban horticulture by the local community, selling urban horticulture products at the city market, expressing positive opinions about growing vegetables, medicinal and aromatic herbs, and fruit near city roads and industrial plants, and support for the use of agrochemicals in urban horticulture. The statement that growing horticultural plants in cities used to be a matter of trendiness is also mostly disagreed with. Other attitudes are mostly neutral, with respondents neither agreeing nor disagreeing on these issues.

Nowadays, there is a need to integrate IT tools into urban horticulture to maintain a consistent food supply and make agriculture more sustainable. Something similar was implemented through online systems for purchasing fresh fruit and vegetables, which partly addressed this issue during the COVID-19 pandemic [33]. In terms of transportation, in addition to the advantage of quickly delivering fresh products due to proximity, there is also the benefit of short marketing chains with low costs. In Croatia and the surrounding region, vegetable crops are the main crops within urban horticulture. In the study by Narandžić Et Al. (2023) [34], most respondents in Novi Sad grew vegetables (in yards and gardens) in the year before and the year after the COVID-19 pandemic. The main motivation for participating in community urban gardens was growing food for personal use and making charitable contributions.

The study by Bretzel Et Al. (2018) [35] emphasized that urban gardeners were not fully aware of how to protect and improve the fertility and quality of urban soil. The authors of the study suggest that city councils should be responsible for providing accurate information to plot owners to prevent potential misuse of urban soil for food cultivation. The application of compost and biochar can be useful for improving the quality of urban soil used for horticultural purposes [36]. In gardening, permanent soil and substrate correction with zeolite enables reduced use of mineral fertilizers and water, while increasing yields both in quantity and quality [37]. Additionally, using biostimulants will make horticultural plants more resistant to climate change and ensure a more environmentally friendly and sustainable agricultural production [38]. Risks to human health associated with long-term exposure to heavy metals can lead to stunted growth, cancer, damage to the nervous system, lungs, and kidneys, behavioral disorders, and impaired memory [39].

H1.

There is a statistically significant difference in attitudes toward the benefits of urban horticulture, the relationship between horticulture and the environment, urban horticulture and plant protection, support for urban horticulture, and the needs and trends of urban horticulture with respect to gender.

The results in Table 3 show that there is a statistically significant difference only in the attitudes related to whether urban horticulture is a trend or a need, with respect to gender (0.039 < 0.05). On average, female respondents (M = 35.21) expressed more positive attitudes regarding the trendiness and necessity of urban horticulture than male respondents (M = 33.92). Although there is a difference in only one dimension, the hypothesis would not be confirmed due to the lack of differences in the other dimensions.

Table 3.

Test of statistically significant differences in attitudes towards the benefits of urban horticulture, the relationship between horticulture and the environment, urban horticulture and plant protection, support for urban horticulture, and the needs and trends of urban horticulture with respect to gender.

In the Šibenik area and its surroundings during the last century, women farmers were the main gardeners, organizing, partly cultivating, tending, and finally diligently selling their own agricultural products, mainly vegetables. They saved seeds from the best and healthiest plants, thus creating some local cultivars. Alongside gardens, they often kept small livestock, goats, or cattle, which were banned in the 1980s. In addition to vegetable crops, women also planted flowers and seasonal fruit trees. The garden was mainly utilitarian in character but later gained a decorative aspect, which had always been emphasized among the nobility. In India too, women farmers are key stakeholders in the horticultural sector, playing a dominant role on and off the farm. They have been key contributors to the growth of this sector, contributing far more than men [40].

Hovorka Et Al. (2009) emphasize that urban farmers are mostly long-term urban residents, often women, and moderately poor [41].

Regarding the intensity of production and profitability, which is directly related to the aforementioned facts about women farmers, Lyson (2012) divided urban agriculture into three groups: recreational urban agriculture, in free time; urban agricultural production for personal and family needs; and entrepreneurial urban agriculture, which mainly consists of private, profit-oriented enterprises [42].

H2.

There is a statistically significant difference in attitudes toward the benefits of urban horticulture, the relationship between horticulture and the environment, urban horticulture and plant protection, support for urban horticulture, and the needs and trends of urban horticulture with respect to age.

Similarly To the previous table, the results in Table 4. shows a statistically significant difference only in the dimension related to urban horticulture and plant protection (0.000 < 0.05). Respondents in the 38–60 and 61–84 age categories show more positive attitudes compared to respondents in the 15–37 age category. The hypothesis is not confirmed because there are no differences in the other dimensions.

Table 4.

Test of statistically significant differences in attitudes towards the benefits of urban horticulture, the relationship between horticulture and the environment, urban horticulture and plant protection, support for urban horticulture, and the needs and trends of urban horticulture with respect to age.

One possible reason for this could be that citizens of more mature and older age are more interested in urban horticulture. Another reason may be that mature and older age citizens see supporting horticulture and plant protection as an opportunity for physical activity, socializing, and feeling socially useful.

H3.

There is a statistically significant difference in attitudes toward the benefits of urban horticulture, the relationship between horticulture and the environment, urban horticulture and plant protection, support for urban horticulture, and the needs and trends of urban horticulture with respect to the place of residence.

According to the results in Table 5, there is a statistically significant difference in attitudes toward the benefits of urban horticulture (0.000 < 0.05), the relationship between urban horticulture and the environment (0.009 < 0.05), and attitudes toward urban horticulture and plant protection (0.005 < 0.05). On average, respondents from Skopje show the most positive attitudes in these dimensions. Because there is a difference in three out of five dimensions, the hypothesis is considered partially confirmed. One possible explanation for the more positive attitudes of Skopje residents could be that their urban environment, especially the air, is relatively more polluted compared to neighboring cities. The study by Maciel Et Al. (2023) [43] shows that urban horticulture meets social indicators and as an activity contributes to awareness standards for sustainable development and lifestyles in harmony with nature.

Table 5.

Test of statistically significant differences in attitudes towards the benefits of urban horticulture, the relationship between horticulture and the environment, urban horticulture and plant protection, support for urban horticulture, and the needs and trends of urban horticulture with respect to place of residence.

Since private gardens have been a part of typical cities for centuries but were forgotten for decades, more and more urban planners today are considering the design of spaces for horticultural production [3]. The motto for future food production should not be “local at any cost”, but rather “as sustainable as possible” [30].

The relationships between urban horticulture and plant protection are very important. Feldmann & Vogler (2021) [44] identified ten current key challenges for plant protection in cities, each belonging to a specific area of IPM (Integrated Pest Management) in urban horticulture according to Directive 2009/128/EC [45]. These challenges include: appropriate plant selection, microbiome engineering, nutrient recycling, smart digital solutions, vegetation diversification, avoiding pesticide side effects on beneficial organisms, biorational efficacy assessment, effective pest diagnosis, effective epidemic control, and a holistic approach.

Van Veenhuizen (2006) [46,47] lists health risks that may be associated with food produced in urban agriculture/horticulture, such as:

- Contamination of crops with pathogens through irrigation water from polluted streams or poorly treated wastewater, and due to poor hygienic handling of produce during transport, processing and placing on the market of fresh produce

- Spread of disease by mosquitoes and other pests attracted by agricultural activities

- Contamination of crops through long-term and intensive use of agrochemicals

- Contamination of agricultural products and soil with heavy metals from exhaust gases and industrial wastewater

H4.

There is a statistically significant difference in attitudes toward the benefits of urban horticulture, the relationship between horticulture and the environment, urban horticulture and plant protection, support for urban horticulture, and the needs and trends of urban horticulture with respect to the location of residence.

The results in Table 6 show that there is no statistically significant difference in attitudes regarding the benefits of urban horticulture, the relationship between horticulture and the environment, urban horticulture and plant protection, support for urban horticulture, or the needs and trends of urban horticulture with respect to the location of residence. Respondents’ attitudes are approximately the same in all dimensions, so it can be concluded that this hypothesis is not confirmed.

Table 6.

Test of statistically significant differences in attitudes toward the benefits of urban horticulture, the relationship between horticulture and the environment, urban horticulture and plant protection, support for urban horticulture, and the needs and trends of urban horticulture with respect to location of residence.

Weinberger and Lumpkin [48] argue that development agencies need to place greater emphasis on horticultural research and development, particularly in the areas of genetic improvement, safe production systems, commercial seed production, post-harvest facilities, and urban/peri-urban environments. Some initiatives support food production in urban settings by promoting new technologies and practices, known as high-tech urban agriculture (HTUA) [49].

An example of good monitoring of plant cultivation in urban horticulture is the good practice of the Zagreb City Gardens, which are located in an urban environment and have a regular monitoring program established by the Institute of Public Health Dr. Andrija Štampar and the Faculty of Agriculture, University of Zagreb. Soil, water and plant material samples are analyzed and the condition of the soil, pollution intake and the health of the vegetables produced are regularly monitored, the results of which are reported to the users of the garden plots in a timely manner [47].

The municipality of Kakanj in Bosnia and Herzegovina, as an industrial municipality, highlights the importance of environmental protection and the improvement and development of urban agriculture [50]. On a broader scale, peri-urban horticulture in the suburbs of Bogotá serves as an important source of vegetables for Colombia’s capital. The sustainability of this peri-urban horticulture is threatened not only by urban expansion but also by its inefficient energy use [51].

H5.

There is a statistically significant difference in attitudes toward the benefits of urban horticulture, the relationship between horticulture and the environment, urban horticulture and plant protection, support for urban horticulture, and the needs and trends of urban horticulture with respect to the level of education.

The results in Table 7, as with the previous table, show that there is no statistically significant difference in attitudes toward the benefits of urban horticulture, the relationship between horticulture and the environment, urban horticulture and plant protection, support for urban horticulture, or the needs and trends of urban horticulture with respect to education level. Respondents’ attitudes are approximately the same across all dimensions of urban horticulture, so it can be concluded that this hypothesis is not confirmed.

Table 7.

Test of statistically significant differences in attitudes toward the benefits of urban horticulture, the relationship between horticulture and the environment, urban horticulture and plant protection, support for urban horticulture, and the needs and trends of urban horticulture with respect to level of education.

Modern media may have influenced the awareness of urban agriculture regardless of education level. The results may indicate that the differences are manifested in other segments, as can be seen in the previous hypotheses. In addition to modern media, another reason why there is no difference can be reflected in the fact that citizens are not active enough regardless of their level of education, and that there is no systemic strategy that would include citizens in activities that deal with.

The University of Zagreb has recognized the importance of urban agriculture by launching an interdisciplinary postgraduate specialist university study program “Urban Management,” several modules of which are related to certain aspects of urban agriculture [25]. Individual higher education institutions in Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and North Macedonia have already included the subject of urban agriculture/horticulture in their curriculum for some time.

On 14 April 2013, the Mayor of the City of Zagreb, Milan Bandić, issued a Decision on the implementation of the City Gardens project for the arrangement and equipping of arable land owned by the City, with the aim of providing part of the arable land for citizens’ use for growing: vegetables and berries, herbs and flowers for personal needs [47,52].

The COVID-19 pandemic has certainly been an additional impetus for urban horticulture. People faced with food shortages responded by increasing plant cultivation in urban areas. In this way, residents more or less consciously initiated horticultural processes [26].

Despite many positive effects and increased awareness in the last decade, the field of urban agriculture in Croatia is still insufficiently researched and requires cooperation among scientists, project leaders, and municipalities [53].

At the beginning of the 21st century, there is a transformation of urban environments into self-sufficient sustainable systems (economic, social, ecological). Developing urban agriculture/horticulture is one of the major challenges. Urban horticulture is a positive way to utilize currently unused lands, buildings, and rooftops, and it can improve air quality, reduce waste, increase biodiversity, reduce the heat island effect, and the ecological footprint [25].

The limitations of the research can be observed as follows: a smaller number of male respondents in the sample because women are more inclined and interested in ‘natural science topics’ than men, similar to Stevanović Et Al. (2025) [25]; a smaller number of older citizens over the age of 61 who are less inclined to new information and communication technologies and to filling out online questionnaires. This is a relatively new scientific discipline, and the research field is extensive, unexplored, and heterogeneous, so analytical studies in this subject area are still insufficient. The paper provides good A foundation for the continuation of various specialized, interdisciplinary, or multidisciplinary research on this issue.

Finally, based on the obtained research results, we provide guidelines to the state and local governments for the improvement of urban horticulture in the studied cities:

- -

- Adequate identification of land for community gardens and the establishment of community gardens

- -

- Introduction of incentives for products from urban horticulture

- -

- Encouraging the sale of urban horticulture products at local markets

- -

- Creation of an online green marketplace

- -

- Promoting local agriculture through urban horticulture product fairs

- -

- Placement of products in neighboring markets through export

- -

- Monitoring of soil in urban crop cultivation

- -

- Preparation of reports and studies for integrating urban agriculture into the city’s landscape for the purpose of tourism valorization

- -

- Education of garden owners and creation of product brands from urban horticulture based on traditional use, quality, profitability, and good market placement

- -

- Modernization of agricultural producers through information technology, technology, and entrepreneurship

- -

- Education of urban farmers on ecological and sustainable horticulture, especially younger residents

- -

- Education on climate change, biodiversity, environmental protection, and safe use of plant protection products

- -

- Introduction of the subject “Urban Horticulture” in secondary and higher education institutions

- -

- And finally the following should also be taken into account: Based on the research of Pereira et al. (2023), the authors emphasize that Mediterranean countries need to develop innovative irrigation systems that will be able to exploit unconventional, largely unused water resources, and policymakers should launch financial lines and incentives for the above, i.e., to solve the problem of water scarcity and mitigate climate change [54].

4. Conclusions

Based on our research, we found that respondents are generally positive toward growing horticultural plants in urban and peri-urban areas under pollution-free conditions. They prefer the use of ecological principles and preparations in urban horticulture. They are aware of the importance of proper pesticide application and the potential contamination of karst systems. Probably due to concerns about pollution, they are reserved about the promotion of urban horticulture by local authorities and the sale of urban horticulture products at city markets. They believe that the cultivation of horticultural plants in the city during the last century was not a matter of trendiness.

Women expressed more positive attitudes regarding the trendiness and necessity of urban horticulture compared to male respondents. Mature and older citizens are more interested in urban horticulture. On average, respondents from Skopje show the most positive attitudes about the benefits of urban horticulture, its relationship with the environment, and plant protection.

There is no statistically significant difference in attitudes toward the benefits of urban horticulture, its relationship with the environment, urban horticulture and plant protection, support for urban horticulture, or the needs and trends of urban horticulture with respect to place of residence. Modern media, insufficient engagement of citizens, and insufficient investment in the systemic development of urban horticulture have influenced awareness of urban horticulture regardless of education level.

The research conducted is important for the development and promotion of urban horticulture with a special emphasis on the importance of environmental conservation.

Based on the results of the research, guidelines were given to state and local self-government for the improvement of urban horticulture in the researched cities. This primarily refers to education on urban horticulture, agrarian policy, marketing and spatial planning.

By involving citizens through social engagement through public discussions, civic activism, media promotion of urban horticulture, and systemic action of the local community, it is possible to improve the conditions of urban horticulture. Systemic action can be established through the educational process itself, from the period of preschool education to university education. This would be established by creating adequate educational curricula that present urban horticulture as a way of life through which healthy and sustainable lifestyle habits of citizens are promoted.

Implications are also necessary for a policy based on the stimulation of unused agricultural areas and a subsidy for the establishment of more urban gardens. As for managers, the main implication would be related to the development of models based on the management and adequate use of urban areas. Of course, these are suggestions based on the research results of this work, and therefore it is necessary to conduct more frequent and longitudinal research on a wider sample, and in more urban areas of the Balkan countries, in order to find out how to positively influence the sustainability of urban horticulture.

The research conducted is important for the development and promotion of urban horticulture with a special emphasis on the importance of environmental conservation not only for the current citizens, but also for future generations. Scientific papers of this type are rare in the Balkans, and the positive side is that several countries are involved, which is just the beginning and an incentive for future researchers to conduct research of this type.

Author Contributions

B.D., E.K. (Esved Kajtaz), Z.B., J.G. and Ž.Š. designed the study; B.D., J.G., E.K. (Esved Kajtaz), Z.B., M.D., D.M. and E.K. (Esmera Kajtaz) collected data for analysis; E.K. (Esved Kajtaz), B.D., Ž.Š. and D.M. conducted statistical analysis and data interpretation; B.D., E.K. (Esved Kajtaz), J.G., E.K. (Esmera Kajtaz), Z.B. and M.D. wrote the manuscript; J.G., Z.B., J.H.S., M.B. and P.G. revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study is waived for ethical review as the survey was conducted through an anonymous online questionnaire, without the collection of any personal or sensitive data by Institution Committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ikerd, J. The Role of Urban Horticulture in the Sustainable Agri-Food Movement. In Urban Horticulture: Sustainability for the Future; Kumar, P., Aggarwal, A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bon, H.; Holmer, R.J.; Aubry, C. Urban Horticulture. In Cities and Agriculture: Developing Resilient Urban Food Systems; de Zeeuw, H., Drechsel, P., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015; pp. 236–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, J.L.; Cunningham, H.; Densley Tingley, D.O.; Dobson, M.C.; Grafius, D.R.; Leake, J.R.; McHugh, N.; Nickles, J.; Phoenix, G.K.; Ryan, A.J.; et al. The Hidden Potential of Urban Horticulture. Nat. Food 2020, 1, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. World Development Report 1994: Infrastructure for Development; Oxford University Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1994; Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/5977 (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture 1996; FAO Agriculture Series No. 29; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 1996; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/w1358e/w1358e.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Schnitzler, W.H.; Holmer, R. Strategies for Urban Horticulture in Developing Countries. Acta Hortic. 1998, 495, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keech, D.; Redepenning, M. Culturalization and Urban Horticulture in Two World Heritage Cities. Food Cult. Soc. 2020, 23, 315–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congreves, K.A. Urban Horticulture for Sustainable Food Systems. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 974146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begić, L.; Temim, E.; Dorbić, B. Značaj urbane poljoprivrede u hortiterapiji s posebnim osvrtom na grad Mostar (Bosna i Hercegovina). Glas. Zašt. Bilja 2022, 45, 4–16. (In Croatian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betti, S. Cultivating Urban Landscapes: Horticulture. Hum. Evol. 2019, 34, 169–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulyas, B.Z. The Contribution of Urban Horticulture to Food Security, Resilience and Health and Well-Being. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sashika, M.N.; Gammanpila, H.W.; Priyadarshani, S.V.G.N. Exploring the Evolving Landscape: Urban Horticulture Cropping Systems-Trends and Challenges. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 327, 112870. Available online: https://rda.sliit.lk/handle/123456789/3722 (accessed on 26 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Fetouh, M.I. Edible Landscaping in Urban Horticulture. In Urban Horticulture: Sustainability for the Future; Kumar, P., Aggarwal, A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 141–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sia, A.; Tan, P.Y.; Er, K.B. The Contributions of Urban Horticulture to Cities’ Liveability and Resilience: Insights from Singapore. Plants People Planet 2023, 5, 828–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogrin, D. Krajinska Arhitektura; Oddelek za Krajinsko Arhitekturo, Biotehniška Fakulteta, Univerza v Ljubljani: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2010. (In Slovenian) [Google Scholar]

- Pereković, P.; Hrdalo, I.; Tomić Reljić, D.; Kamenečki, M. Ekološki principi u uređenju gradskih krajobraza. Glas. Future 2023, 6, 59–75. (In Croatian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevanović, S.; Dorbić, B.; Španjol, Ž.; Kajtaz, E.; Margaletić, J.; Stevanović, Z.; Ljubojević, M.; Barčić, D. Significance of Songbirds for Park Visitors, the Urban Environment and Biodiversity: Example of the Croatian Coastal Belt. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrichs, C.; Mewis, I. Recent Developments in Urban Horticulture—Facts and Fiction. Acta Hortic. 2015, 1099, 925–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, M.C.; Crispo, M.; Blevins, R.S.; Warren, P.H.; Edmondson, J.L. An Assessment of Urban Horticultural Soil Quality in the United Kingdom and Its Contribution to Carbon Storage. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 777, 146199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutaladio, N.; Burlingame, B.; Crews, J. Horticulture, Biodiversity and Nutrition. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2010, 23, 481–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.R.; Rajan, S. Vertical Hydroponics: A Future Technology for Urban Horticulture. Indian Hortic. 2022, 67, 36–39. Available online: https://epubs.icar.org.in/index.php/IndHort/article/view/123829 (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Nandwani, D. (Ed.) Urban Horticulture; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertani, A.; Bulgari, R.; Larcher, F.; Devecchi, M.; Nicola, S. Urban Horticulture: A Case Study of a Soilless Urban Garden in Turin (Italy). Acta Hortic. 2022, 1345, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubić, T.; Gulin Zrnić, V. Vrtovi našega grada—Studije i zapisi o praksama urbanog vrtlarenja. Stud. Ethnol. Croat. 2015, 27, 481–513. (In Croatian) [Google Scholar]

- Kisić, I. Gradska Poljoprivreda; Sveučilište u Zagrebu, Agronomski fakultet: Zagreb, Croatia, 2018. (In Croatian) [Google Scholar]

- Hadžiabulić, A. Urbana Hortikultura: Izazov Proizvodnje Hrane u Gradovima; Vlastita Naklada: Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2022. (In Bosnian) [Google Scholar]

- Симoнoв, Д.; Ристевски, Б.; Пoпoвски, П. Уредување и кoристење на двoрни пoвршини; Земјoделски факултет: Скoпје, North Macedonia, 2002; p. 13. (In Macedonian) [Google Scholar]

- Grgurević, D. Kultura Vrtova, Perivoja i Parkova na Području Splita Tijekom Povijesti; Književni Krug Split: Split, Croatia, 2002. (In Croatian) [Google Scholar]

- Defilippis, J. Dalmatinsko Selo u Promjenama; Avium: Split, Croatia, 1997. (In Croatian) [Google Scholar]

- Eigenbrod, C.; Gruda, N. Urban Vegetable for Food Security in Cities—A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 35, 483–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rašković, V.; Stepić, V.; Glišić, M.; Tomić, V. Urbana poljoprivreda i povrtarstvo/Urban Agriculture and Vegetable Growing. In Proceedings of the 24st Symposium on Biotechnology with International Participation, Čačak, Serbia, 15–16 March 2019; Volume 1. (In Serbian). [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, M.A. Urban Agriculture as a Tool for Horticultural Education and Youth Development. In Urban Horticulture: Sustainability for the Future; Kumar, P., Aggarwal, A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 211–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.M.; Akram, M.T.; Janke, R.; Qadri, R.W.K.; Al-Sadi, A.M.; Farooque, A.A. Urban Horticulture for Food Secure Cities through and beyond COVID-19. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narandžić, T.; Ružičić, S.; Grubač, M.; Pušić, M.; Ostojić, J.; Šarac, V.; Ljubojević, M. Landscaping with Fruits: Citizens’ Perceptions toward Urban Horticulture and Design of Urban Gardens. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretzel, F.; Caudai, C.; Tassi, E.; Rosellini, I.; Scatena, M.; Pini, R. Culture and Horticulture: Protecting Soil Quality in Urban Gardening. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 644, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medyńska-Juraszek, A.; Marcinkowska, K.; Gruszka, D.; Kluczek, K. The Effects of Rabbit-Manure-Derived Biochar Co-Application with Compost on the Availability and Heavy Metal Uptake by Green Leafy Vegetables. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prisa, D. Zeolites: A Potential Strategy for the Solution of Current Environmental Problems and a Sustainable Application for Crop Improvement and Plant Protection. GSC Adv. Res. Rev. 2023, 17, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisvarga, S.; Farkas, D.; Boronkay, G.; Neményi, A.; Orlóci, L. Effects of Biostimulants in Horticulture, with Emphasis on Ornamental Plant Production. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, P.K.; Lee, S.S.; Zhang, M.; Tsang, Y.F.; Kim, K.-H. Heavy Metals in Food Crops: Health Risks, Fate, Mechanisms, and Management. Environ. Int. 2019, 125, 365–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.K.; Sahu, A.; Das, L. Women in Growth of Horticulture—Contributions and Issues. Prog. Hortic. 2020, 52, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovorka, A.; de Zeeuw, H.; Njenga, M. Women Feeding Cities: Mainstreaming Gender in Urban Agriculture and Food Security; Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lyson, T.A. Civic Agriculture: Reconnecting Farm, Food, and Community; University Press of New England (UPNE): Lebanon, NH, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Maciel, M.D.N.O.; de Lima, H.V.; Pinheiro, D.P. Urban Horticulture: Social Benefits in the UN 2030 Agenda. Rev. Cienc. Agrar. 2023, 46, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldmann, F.; Vogler, U. Towards Sustainable Performance of Urban Horticulture: Ten Challenging Fields of Action for Modern Integrated Pest Management in Cities. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2021, 128, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament and Council. Directive 2009/128/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 October 2009 Establishing a Framework for Community Action to Achieve the Sustainable Use of Pesticides. Off. J. Eur. Union 2009, L309, 71–86. [Google Scholar]

- Van Veenhuizen, R. Cities Farming for the Future: Urban Agriculture for Green and Productive Cities; RUAF Foundation, IDRC, IIRR: Leusden, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 2–17. [Google Scholar]

- Poštek, A. Društvena Uloga i Značaj Gradske Poljoprivrede. Diplomski Rad, Sveučilište u Zagrebu, Agronomski fakultet, Zagreb, Croatia. 2020. Available online: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:204:213238 (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Weinberger, K.; Lumpkin, T.A. Diversification into Horticulture and Poverty Reduction: A Research Agenda. World Dev. 2007, 35, 1464–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhangi, M.H.; Turvani, M.E.; van der Valk, A.; Carsjens, G.J. High-Tech Urban Agriculture in Amsterdam: An Actor Network Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahirović, N.; Trakić, S.; Krstić, P.; Biber, L. Adaptacija postojećih ravnih krovova solitera u zelene krovove na području Općine Kakanj u cilju osnaživanja i promovisanja koncepta urbane poljoprivrede. Rad. Šum. Fak. Univ. Sarajevu 2023, 53, 2. (In Bosnian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojaca, C.R.; Schrevens, E. Energy Assessment of Peri-Urban Horticulture and Its Uncertainty: Case Study for Bogota, Colombia. Energy 2010, 35, 2109–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrakužić, B. Projekt Gradski vrtovi. Epoha Zdr. Glas. Hrvat. Mreže Zdr. Gradov. 2018, 10, 3–6. (In Croatian) [Google Scholar]

- Poštek, A.; Kisić, I.; Cerjak, M.; Brezinščak, L. Društvena uloga gradske poljoprivrede sa primjerima iz Hrvatske. J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 2021, 22, 881–891. (In Croatian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, D.; Leitão, J.C.C.; Gaspar, P.D.; Fael, C.; Falorca, I.; Khairy, W.; Wahid, N.; El Yousfi, H.; Bouazzama, B.; Siering, J.; et al. Exploring Irrigation and Water Supply Technologies for Smallholder Farmers in the Mediterranean Region. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).