Non-Wood Forest Product Extractivism: A Case Study of Euterpe oleracea Martius in the Brazilian Amazon

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

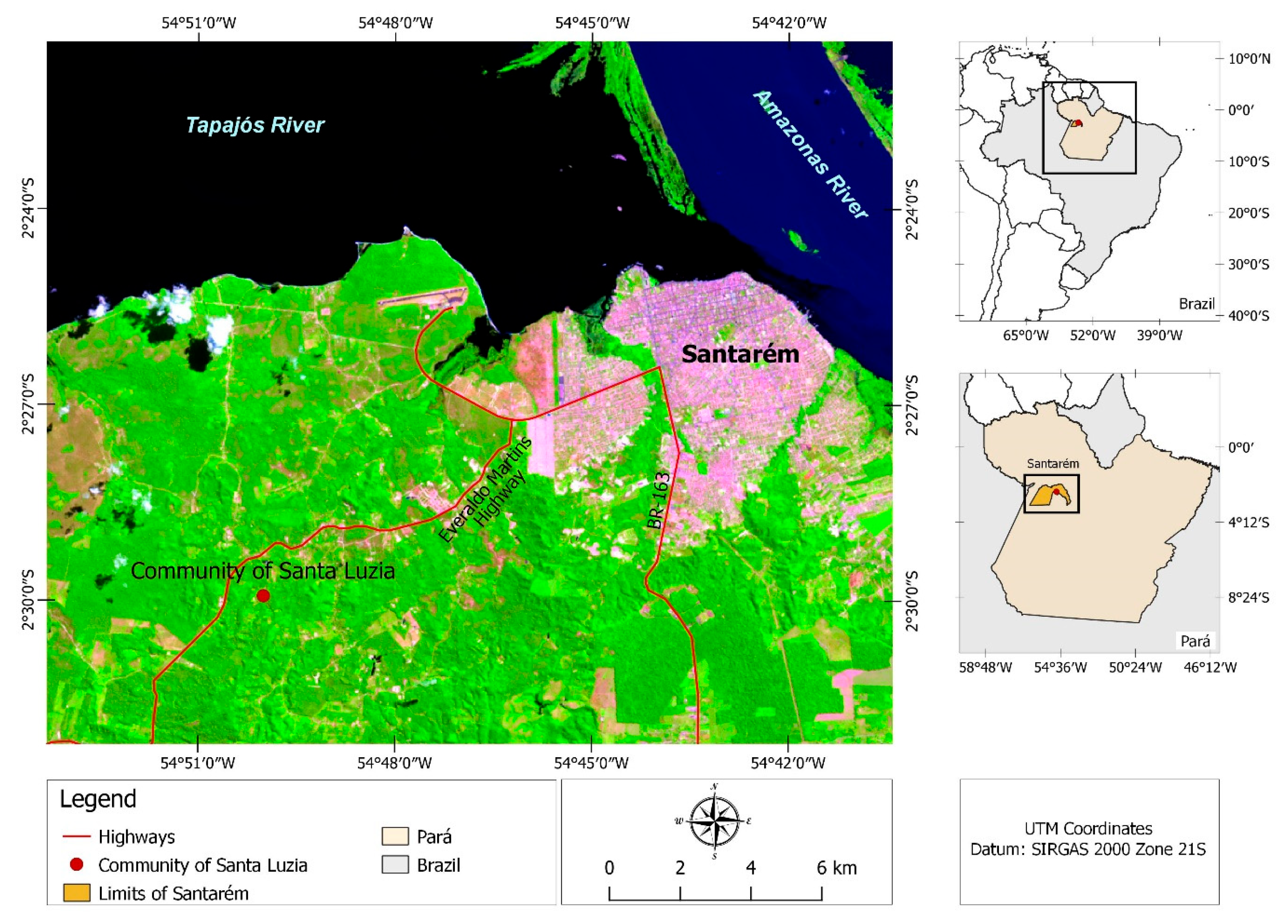

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sampling and Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Interviewee Profile

3.2. Fruit Collection Area

3.3. Characterization of the Harvest and the Production Period

3.4. Characterization of the Production Circuit

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nogueira, O.L.; Homma, A.K.O. Análise Econômica de Sistemas de Manejo de Açaizais Nativos no Estuário Amazônico, 1st ed.; Embrapa CPATU: Belém, Brazil, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- FAO—Food and Agriculture Organization of the United. State of the World’s Forests. Enhancing the Socioeconomic Benefits from Forests. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i3710e (accessed on 10 March 2020).

- Pedrozo, E.A.; Silva, T.N.; Sato, S.A.S.; Oliveira, N.D.A. Produtos florestais não madeiráveis (PFNMS): As filiéres do açaí e da castanha da Amazônia. Rev. Adm. Negócios Amaz. 2011, 3, 88–112. [Google Scholar]

- Calzavara, B.B.G. As possibilidades do açaizeiro no estuário amazônico. In Simpósio Internacional Sobre Plantas de Interesse Econômico de la Flora Amazónica; Faculdade de Ciências Agrárias do Pará: Turrialba, Costa Rica, 1972; Volume 5, pp. 165–207. [Google Scholar]

- Araújo, F.R.; Lopes, M.A. Diversity of use and local knowledge of palms (Arecaceae) in eastern Amazonia. Biodivers. Conserv. 2012, 2, 487–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, T.S.S.d.A.; Macedo, P.C.d.E.; Converti, A.; Lima, A.A.N. The use of Euterpe oleracea Mart. as a new perspective for disease treatment and prevention. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valles, C.M.A. Impactos da Dinâmica da Demanda dos Frutos de açaí nas Relações Socioeconômicas e Composição Florística no Estuário Amazônico. Master’s Thesis, Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém, Brazil, 31 May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Freddo, A.R.L.F. Açaí. In Boletim da Sociobiodiversidade, 1st ed.; Companhia Nacional de Abastecimento: Brasília, Brazil, 2017; Volume 1, pp. 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, J.C.; Sena, S.A.L.; Homma, A.K.O. Viabilidade Econômica do Manejo de Açaizais no Estuário Amazônico: Estudo de caso na Região do Rio Tauerá-açu, Abaetetuba—Estado do Pará. In Anais Agricultura e Desenvolvimento Rural com Sustentabilidade; Sociedade Brasileira de Economia, Administração e Sociologia Rural: Vitória, Brazil, 2012; pp. 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Zanatta, G.V. O Extrativismo de açaí (Euterpe precatoria Mart.) e os Sistemas Produtivos Tradicionais na Terra Indígena Kwata-Laranjal, Amazonas. Master’s Thesis, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia, Manaus, Brazil, 5 October 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Serviço Florestal Brasileiro. Florestas e Recursos Naturais, 1st ed.; Boletim SNIF: Brasília, Brazil, 2019; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Graefe, S.; Dufour, D.; Zonneveld, M.V.; Rodrigues, F.; Gonzales, A. Peach palm (Bactris gasipaes) in tropical Latin America: Implications for biodiversity conservation, natural resource management and human nutrition. Biodivers. Conserv. 2013, 22, 269–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, L.N.B.; Oliveira, E.A.A.Q.; Oliveira, A.L. Extrativismo e manejo do açaí: Atrativo amazônico favorecendo a economia regional. In Encontro Latino Americano de Iniciação Científica e Encontro Latino Americano de Pós-Graduação; Universidade do Vale do Paraíba: São José dos Campos, Brazil, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics—IBGE. Produção da Extração Vegetal e da Silvicultura—PEVS. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/economicas/agricultura-e-pecuaria/9105-producao-da-extracao-vegetal-e-da-silvicultura.html?=&t=destaques (accessed on 9 May 2019).

- Rodrigues, E.C.N.; Ribeiro, S.C.A.; Silva, F.L. Influência da cadeia produtiva do açaí (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) na geração de renda e fortalecimento de unidades familiares de produção, Tomé Açú-PA. Obs. Econ. Latinoam. 2015, 1, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Nogueira, O.L. Regeneração, Manejo e Exploração de Açaizais Nativos de Várzea do Estuário Amazônico. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Federal do Pará, Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária, Belém, Brazil, 23 December 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Barreto, E.L.; Silva, R.C.; Vieira, V.H.G.; Pena, H.W.A. Análise de viabilidade econômica: Um estudo aplicado à estrutura de custo da cultura do açaí no estado do Amazonas. Obs. Econ. Latinoam. 2012, 161, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, V.L.B.; Carvalho, R.S.C. Trabalho extrativista e condições de vida de trabalhadores: Famílias da Ilha do Combú (Pará). Argumentum 2012, 2, 208–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leão, R.F.C.; Oliveira, J.M.G.C. O plano diretor e a cidade de fato: O caso de Santarém-PA. Rev. Geográfica América Cent. 2011, 2, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ximenes, L.C.; Gama, J.R.V.; Vieira, T.A. Consumer profile of açaí in the city of Santarém, Brazilian Amazon. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2015, 36, 60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Colonização e Reforma Agrária. Projeto de Assentamento Promove Festival do Açaí em Santarém (PA). Available online: https://incraoestepara.wordpress.com/tag/santa-luzia/ (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- Instituto Nacional de Colonização e Reforma Agrária. Relação de Projetos de Reforma Agrária. Available online: https://www.gov.br/incra/pt-br (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- Alvares, C.A.; Stape, J.L.; Sentelhas, P.C.; Gonçaves, J.L.M.; Sparovek, G. Köppen's climate classification map for Brazil. Meteorol. Z. 2013, 22, 711–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martorano, L.G.; Pereira, L.C.; Nechet, D. Tipologia climática do estado do Pará. Bol. Geogr. Teorética 1993, 23, 307–312. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, A.S.; Vieira, T.A. Percepção e uso de mata ciliar em um projeto de assentamento, Santarém (PA). Rev. Ibero-Am. Ciências Ambient. 2018, 6, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanou, M.P.; Ros-Tonen, M.; Reed, J.; Moombe, K.; Snderland, T. Integrating local and scientific knowledge: The need for decolonising knowledge for conservation and natural resource management. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryman, A. Integrating quantitative and qualitative research: How is it done? Qual. Res. 2006, 6, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuthego, T.C.; Chanda, R.R. Traditional ecological knowledge and community-based natural resource management: Lessons from a Botswana wildlife management area. J. Appl. Geogr. 2004, 24, 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buthelezi, N.N.; Hughes, J.C.; Modi, A.T. The use of scientific and indigenous knowledge in agricultural land evaluation and soil fertility studies of two villages in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2013, 8, 507–518. [Google Scholar]

- Constant, N.L.; Taylor, P.J. Restoring the forest revives our culture: Ecosystem services and values for ecological restoration across the rural-urban nexus in South Africa. For. Policy Econ 2020, 118, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jevon, T.; Shackleton, C.M. Integrating local knowledge and forest surveys to assess Lantana camara impacts on indigenous species recruitment in Mazeppa Bay, South Africa. Hum. Ecol. 2015, 43, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasali, G. Integrating Indigenous and Scientific Knowledge Systems for Climate Change Adaptation in Zambia; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kaschula, S.A.; Twine, W.E.; Scholes, M.C. Coppice harvesting of fuelwood species on a South African common: Utilizing scientific and indigenous knowledge in community based natural resource management. Hum. Ecol. 2005, 33, 387–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezomba, H.; Mtambanengwe, F.; Tittonell, P.; Mapfumo, P. Practical assessment of soil degradation on smallholder farmers’ fields in Zimbabwe: Integrating local knowledge and scientific diagnostic indicators. Catena 2017, 156, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sichula, N.; Musonda, L.; Wanga, W. Education for sustainable development: Integrating indigenous knowledge in water and sanitation programmes in Shimukuni community of Chibombo district in Zambia. Int. J. Contemp. Appl. Sci. 2016, 3, 114–127. [Google Scholar]

- Albuquerque, U.P.; Lucena, R.F.P.; Lins Neto, E.M.F. Métodos e Técnicas na Pesquisa Etnobiológica e Etnoecológica, 3rd ed.; NUPEEA: Recife, Brazil, 2010; pp. 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hudelson, P.M. Qualitative Research for Health Programmes, 1st ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1994; pp. 1–108. [Google Scholar]

- Neto, J.T.F.; Vasconcelos, M.A.M.; Silva, F.C.F. Cultivo do açaizeiro em terra firme. In Cultivo, Processamento, Padronização e Comercialização do açaí na Amazônia, 1st ed.; Oliveira, M.D.S.P.D., Farias Neto, J.T.D., Eds.; Instituto Frutal: Fortaleza, Brazil, 2010; pp. 8–57. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, A.G.; Santos, H.S.; Araújo, T.M.M. Análise de aspectos ergonômicos na colheita de açaí na ilha do Combu-Belém-Pará. In Proceedings of the XXVIII Encontro Nacional de Engenharia de Produção, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 9–11 October 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, E.K.C.; Ferreira, V.R. O trabalho do “peconheiro” na região amazônica: Uma análise das condições de trabalho na colheita do açaí a partir do conceito de trabalho decente. Rev. Direito Trab. Meio Ambiente Trab. 2020, 1, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinot, J.F.; Pereira, H.S.; Silva, S.C.P. Coletar ou cultivar: As escolhas dos produtores do açaí-da-mata (Euterpe precatoria) do Amazonas. Rev. Econ. Sociol. Rural 2017, 4, 751–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homma, A.K.O. Extrativismo Vegetal na Amazônia: História, Ecologia, Economia e Domesticação, 1st ed.; Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária Amazônia Oriental: Belém, Brazil, 2014; Volume 1, pp. 1–472. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, J.L.P.; Chaves, E.S.; Amanajás, H.W.; Sousa, J.T.R. Caracterização das unidades de processamento domiciliar de polpa de açaí (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) da cidade de Santarém, PA. Rev. Caribeña Cienc. Soc. 2018, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Applied Economic Research. Cadeias de Comercialização de Produtos Florestais não Madeireiros na Região de Integração Rio Capim, Estado do Pará, 1st ed.; Relatório de Pesquisa: Brasília, Brazil, 2016; pp. 1–192. [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento, E.C.; Guerra, G. Multifunctional backyards: The diversity of food and production practices developed by the families of the quilombola community of Baixo Acaraqui, Abaetetuba, Pará. Rev. IDeAS 2014, 2, 7–40. [Google Scholar]

- Empresa de Assistência Técnica e Extensão Rural. Plano de Desenvolvimento do Projeto de Assentamento Agroextrativista do Eixo Forte, 1st ed.; EMATER: Santarém, Brazil, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Colonização e Reforma Agrária. Projetos de Assentamento Agroextrativistas—PAEs, 1st ed.; INCRA: Brasília, Brazil, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bonomo, L.F.; Silva, D.N.; Boasquivis, P.F.; Paiva, F.A.; Guerra, J.F.; Martins, T.A.; Torres, A.G.J.; Paula, I.T.; Caneschi, W.L.; Jacolot, P.; et al. Açaí (Euterpe olearaceae Mart.) modulates oxidative stress resistance in Caenorhabditis elegans by direct and indirect mechanisms. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steward, A. Reconfiguring agrobiodiversity in the Amazon Estuary: Market integration, the acai trade and smallholders’ management practices in Amapá, Brazil. Hum. Ecol. 2013, 6, 827–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, C.T.D.; Navegantes-Alves, L.d.F. Do extrativismo ao cultivo intenso do açaizeiro (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) no estuário amazônico: Sistemas de manejo e suas implicações sobre a diversidade de espécies arbóreas. Rev. Bras. Agroecol. 2015, 10, 12–23. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo, J.R. Sistema de Manejo de Açaizais Nativos Praticados por Ribeirinhos, 1st ed.; EDUFMA: São Luis, Brazil, 2007; pp. 1–100. [Google Scholar]

- Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento. Açaí-de-touçeira (Euterpe oleracea Mart.). In Série boas práticas de manejo sustentável orgânico; Secretaria de Desenvolvimento Agrário e Cooperativismo: Brasília, Brazil, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo, J.R. Tipologia do Sistema de Manejo de Açaizais Nativos Praticados por Ribeirinhos em Belém, Estado do Pará. Master’s Thesis, Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém, Brazil, 18 April 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ximenes, L.C.; Gama, J.R.V.; Vieira, D.S. Descrição dos estabelecimentos que processam açaí em Santarém, Pará. In 14° Semana de Integração das Ciências Agrárias; Universidade Federal do Pará: Altamira, Brazil, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento, W.M.O. Açaí (Euterpe oleracea Mart.). In Informativo Técnico Rede de Sementes da Amazônia, 1st ed.; Embrapa Amazônia Oriental: Belém, Brazil, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, M.A.S.; Chaar, J.S.; Nascimento, L.R.C. Polpa de açaí: O caso da produção do pequeno produtor urbano de Manaus. Rev. Sci. Amazon. 2014, 2, 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes, A.M.; Lopes, M.L.B.; Falesi, L.A.; Filgueiras, G.C. O mercado de açaí no estado do Pará: Uma análise recente. Amaz. Ciência Desenvolv. 2012, 15, 105–119. [Google Scholar]

- Homma, A.K.O.; Muller, A.A.; Muller, C.H.; Pereira, C.A.P.; Figueirêdo, F.J.C.; Viégas, I.J.M.; Neto, J.T.F.; Carvalho, J.E.U.; Cohen, K.O.; Souza, L.A.; et al. Introdução e importância socioeconômica. In Açaí; Nogueira, O.L., Figueiredo, F.J.C., Müller, A.A., Eds.; Embrapa Amazônia Oriental: Belém, Brazil, 2005; Volume 4, pp. 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Pepper, L.G.; Navegantes Alves, L.D.F. Small-scale Açaí in the global market: Adding value to ensure sustained income for forest farmers in the Amazon Estuary. In Integrating Landscapes: Agroforestry for Biodiversity Conservation and Food Sovereignty, 1st ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 12, pp. 211–234. [Google Scholar]

- Brasil. Ministério do Meio Ambiente. Lei nº 9985/2000. Institui o Sistema Nacional de Unidades de Conservação da Natureza e dá Outras Providências. Available online: https://www.jusbrasil.com.br/legislacao/101710/lei-9985-00 (accessed on 21 March 2021).

- Nogueira, A.K.M.; Santana, A.C. Análise de sazonalidade de preços de açaí, cupuaçu e bacaba no estado do Pará. Rev. Estud. Sociais 2009, 21, 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, A.A.; Santos, M.K.V.; Gama, J.R.V.; Noce, R.; Leão, S. Potencial do extrativismo da Castanha-do–Pará na geração de renda em comunidades da mesorregião Baixo Amazonas, Pará. Floram 2013, 4, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Homma, A.K.O.; Nogueira, O.L.; Menezes, A.J.E.A.; Carvalho, J.E.U.; Nicole, C.M.L.; Matos, G.B. Açaí: Novos desafios e tendências. Amaz. Ciência Desenvolv. 2006, 2, 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, M.P.; Riva, F.B.; Silva, T.N.; Paes, D.C.A.S. Organização social baseada na lógica de cadeia-rede para potencializar a exploração do açaí nativo na Amazônia Ocidental. Rev. Univ. Fed. Santa Maria 2013, 6, 281–294. [Google Scholar]

| Harvests | Months of Occurrence |

|---|---|

| Collection period | September to January |

| Summer harvest (greater production) | November to December |

| Winter harvest (lower production) | January |

| Inter-harvest | February to August |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de Oliveira, E.P.; Ximenes, L.C.; Gama, J.R.V.; Vieira, T.A. Non-Wood Forest Product Extractivism: A Case Study of Euterpe oleracea Martius in the Brazilian Amazon. Sustainability 2025, 17, 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17020464

de Oliveira EP, Ximenes LC, Gama JRV, Vieira TA. Non-Wood Forest Product Extractivism: A Case Study of Euterpe oleracea Martius in the Brazilian Amazon. Sustainability. 2025; 17(2):464. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17020464

Chicago/Turabian Stylede Oliveira, Emilly Pinheiro, Lucas Cunha Ximenes, João Ricardo Vasconcellos Gama, and Thiago Almeida Vieira. 2025. "Non-Wood Forest Product Extractivism: A Case Study of Euterpe oleracea Martius in the Brazilian Amazon" Sustainability 17, no. 2: 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17020464

APA Stylede Oliveira, E. P., Ximenes, L. C., Gama, J. R. V., & Vieira, T. A. (2025). Non-Wood Forest Product Extractivism: A Case Study of Euterpe oleracea Martius in the Brazilian Amazon. Sustainability, 17(2), 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17020464