The Intersection Between Food Literacy and Sustainability: A Systematic Quantitative Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Food and Sustainable Development

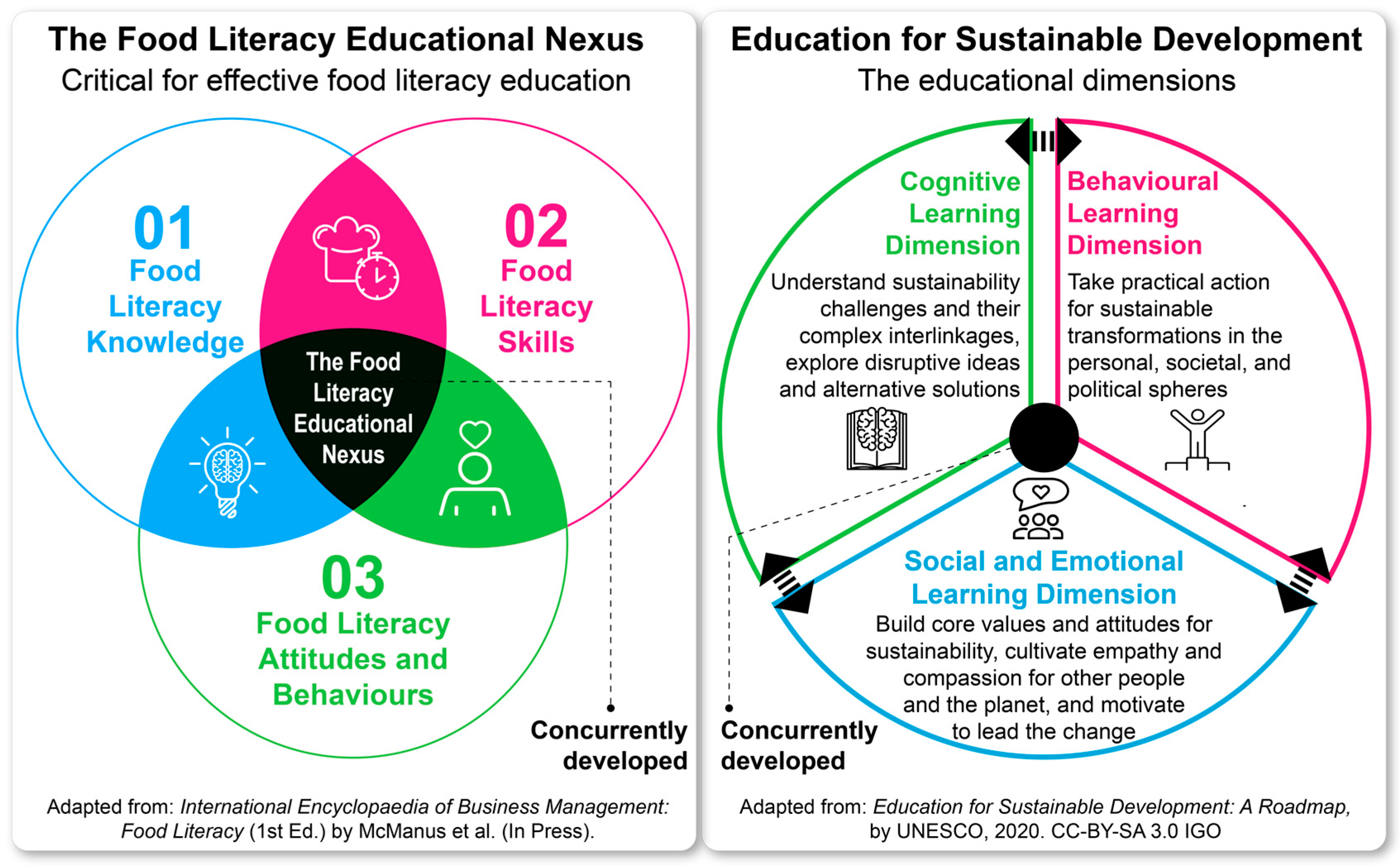

1.2. Food Literacy

1.3. Education for Sustainable Development

1.4. Study Aim

- What methodologies, research areas, data types, demographics, and research growth patterns are associated with sustainable food literacy research?

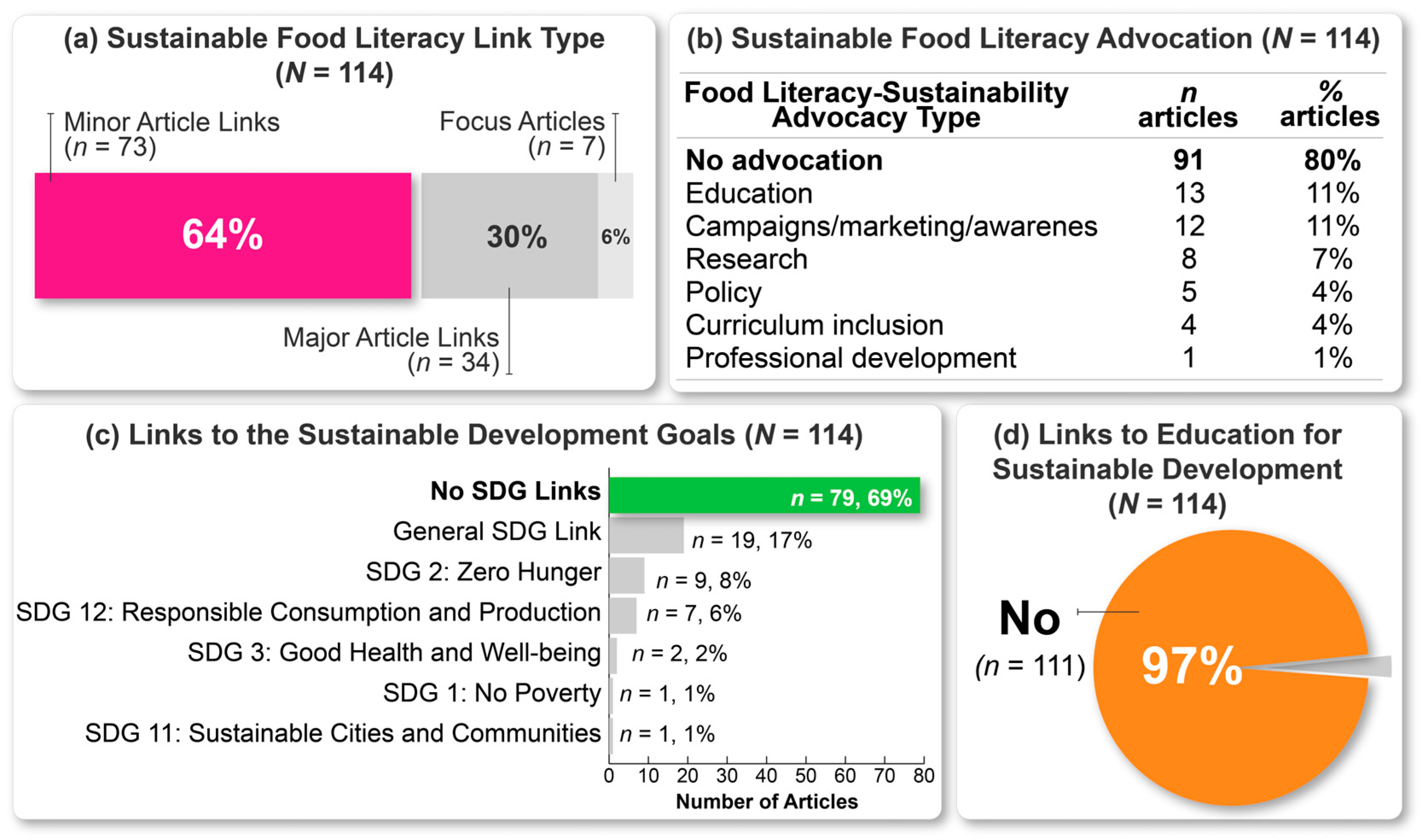

- What proportion of research makes minor, major, or focus article links between food literacy and sustainability?

- How comprehensive are the SDG, ESD, and advocation representation in sustainable food literacy research?

- 4.

- How can the research topics and their embedded nuances within sustainable food literacy research be conceptualised within the knowledge [cognitive], skill [behaviour], and attitude/behaviour [social/emotional] dimensions?

- 5.

- What are the emerging research lenses within sustainable food literacy research?

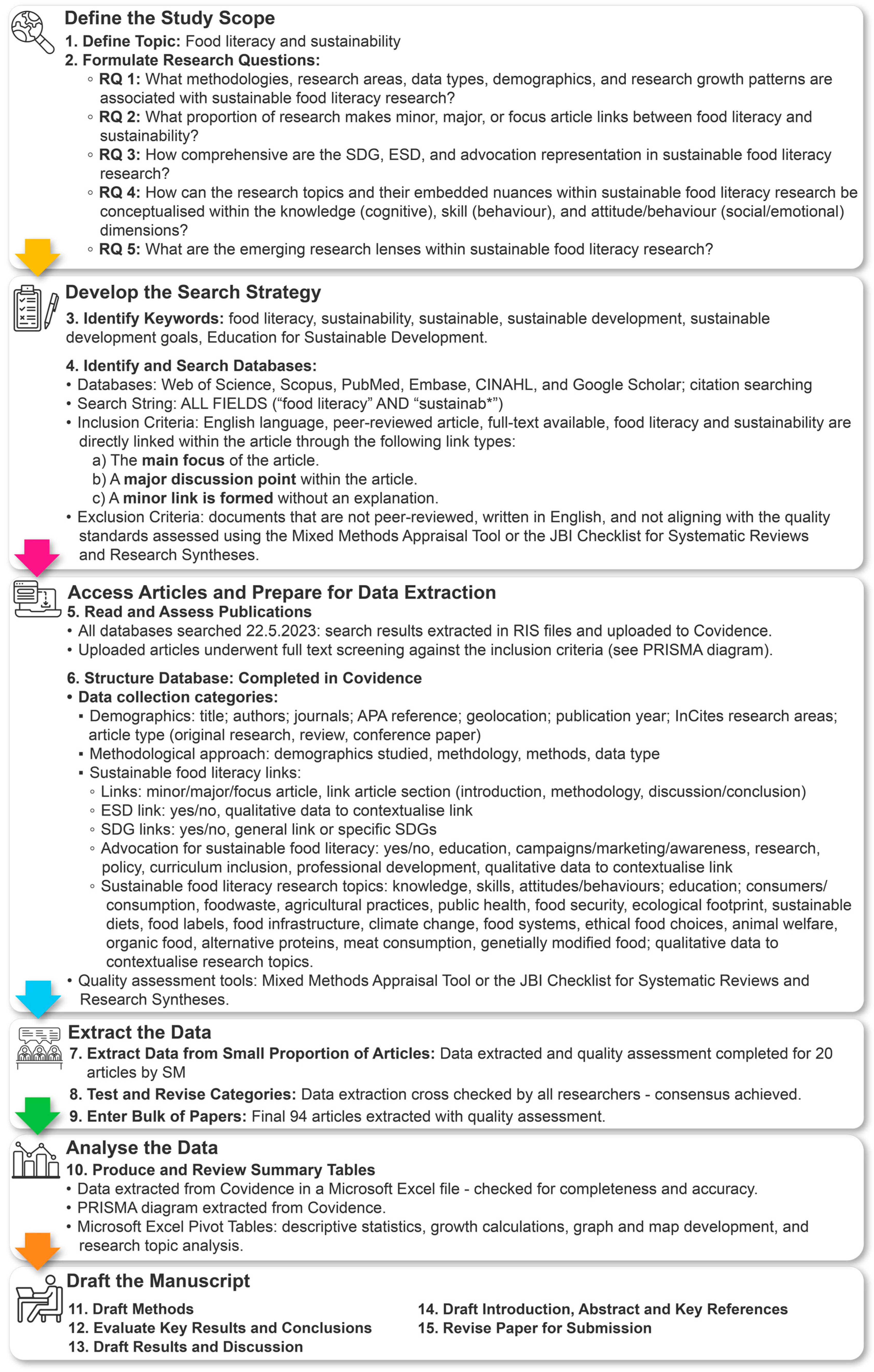

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The SQLR Methodology

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- Minor article link: a brief link, for example, a sentence or small paragraph, but was not the article’s primary focus;

- Major article links: the link formed a major point within the article but was not the main focus;

- Focus articles: the article focused on sustainable food literacy research.

2.3. Information Sources

2.4. Search Strategy

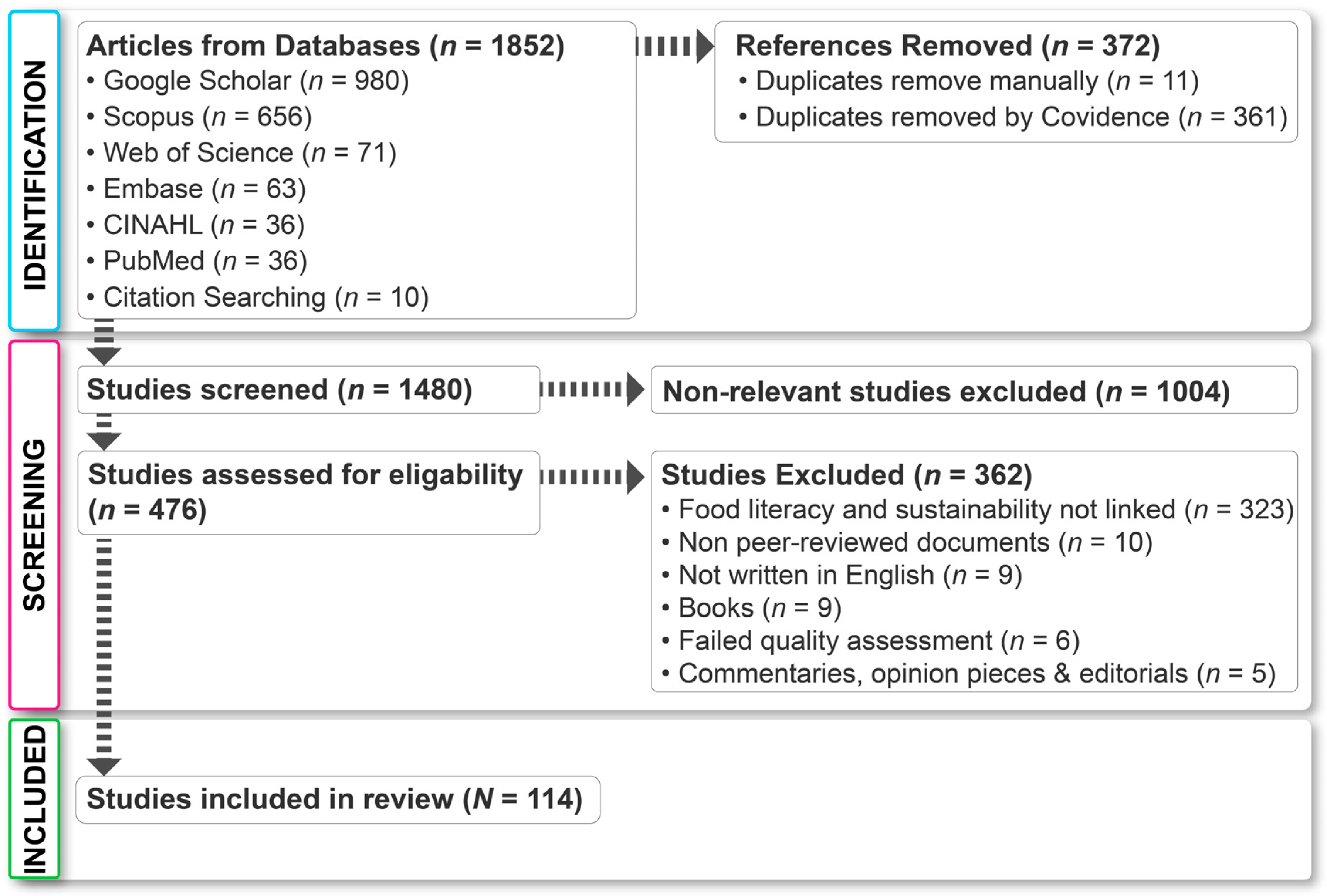

2.5. Selection Process

2.6. Data Collection Process

2.7. Study Risk of Bias Assessment

2.8. Effect Measures

2.9. Synthesis Methods

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Links to Sustainable Food Literacy

3.3. Sustainable Food Literacy Research Topics

3.3.1. Knowledge, Skills, Attitudes/Behaviours

3.3.2. Research Topic: Education

3.3.3. Food Systems

3.3.4. Consumers and Consumption

3.3.5. Sustainable Diets

3.3.6. Food Waste

3.3.7. Agricultural Practices

3.3.8. Research Topic: Public Health

3.3.9. Climate Change

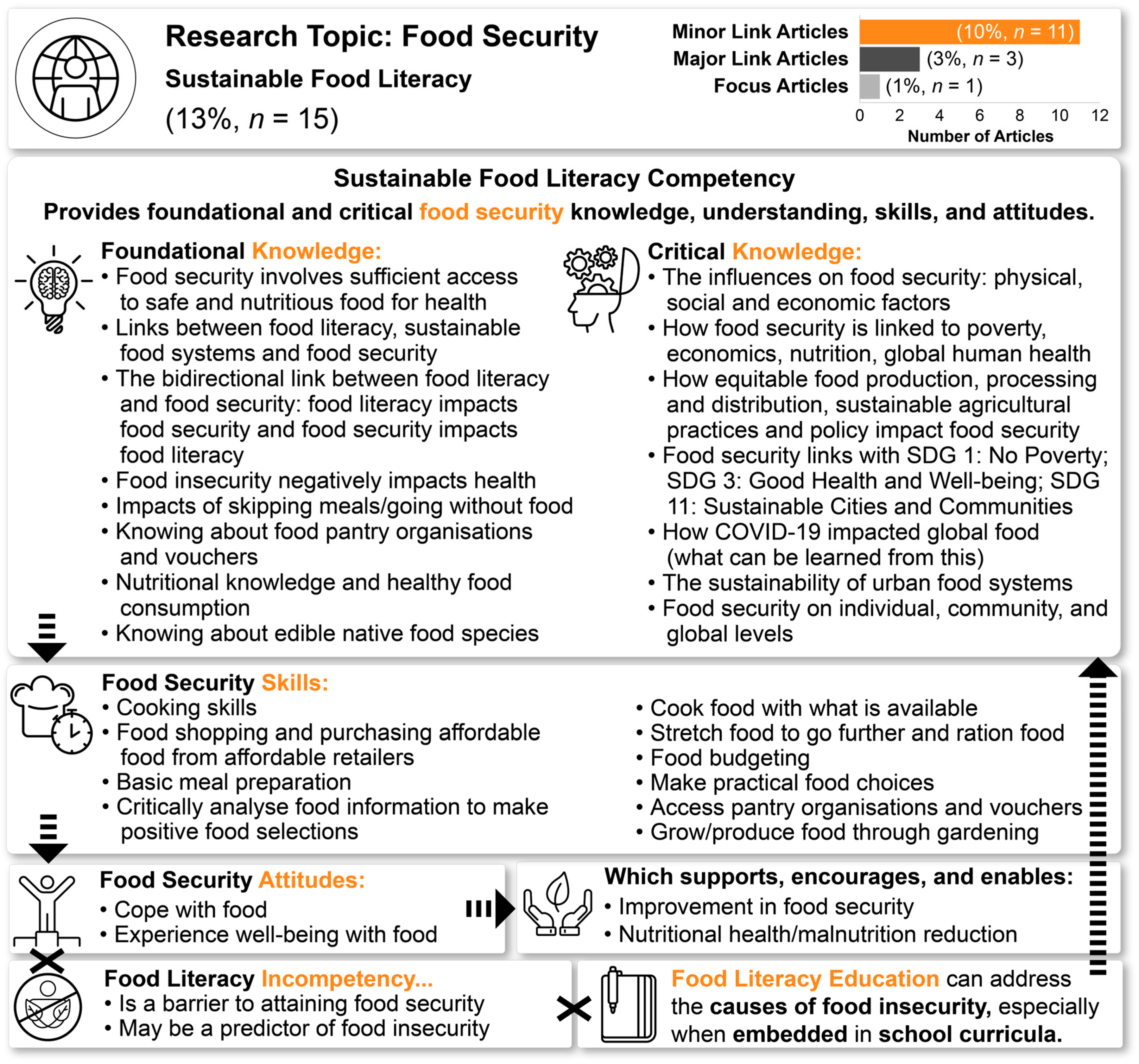

3.3.10. Food Security

3.3.11. Food Infrastructure

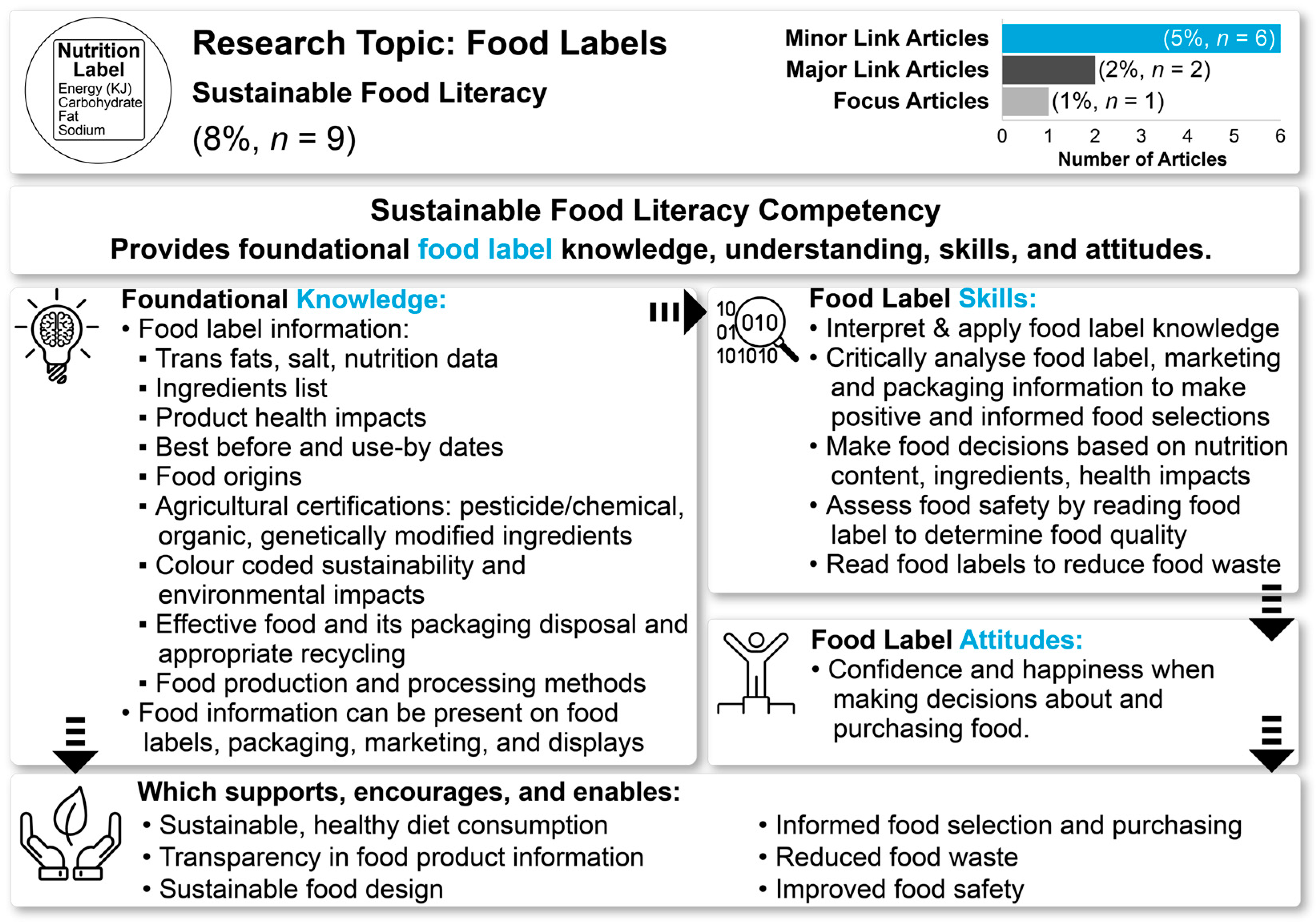

3.3.12. Food Labels

3.3.13. Ecological Footprint

4. Discussion

4.1. Methodological Influences in Sustainable Food Literacy Research (Phase One, RQ1)

4.2. The Representation of Sustainable Food Literacy Research (Phase One, RQ2 and RQ3)

4.3. The Conceptualisation of Sustainable Food Literacy Research (Phase Two, RQ4)

4.4. Implications for Future Research (Phase Three, RQ5)

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/food-safety (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available online: https://www.fao.org/hunger/en/ (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Food and Agriculture Organization for the United Nations. Available online: https://doi.org/10.4060/cb4476en (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/dental-oral-health/oral-health-and-dental-care-in-australia/contents/summary (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/salt-reduction (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- The World Bank. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/700061468334490682/pdf/95768-REVISED-WP-PUBLIC-Box391467B-Ending-Poverty-and-Hunger-by-2030-FINAL.pd (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- United Nations. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/science/causes-effects-climate-change (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- United Nations. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/observances/end-food-waste-day (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- United Nations. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- United Nations. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/food-systems-summit (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- United Nations. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/29858SG_SDG_Progress_Report_2022.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- United Nations. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2024/ (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- United Nations. Available online: https://www.unfoodsystemshub.org/fs-stocktaking-moment/en (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Vidgen, H.; Gallegos, D. Defining food literacy and its components. Appetite 2014, 76, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cullen, T.; Hatch, J.; Martin, W.; Higgins, J.W.; Sheppard, R. Food literacy: Definition and framework for action. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2015, 76, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McManus, S.; Pendergast, D.; Kanasa, H.; Ratten, V. (Eds.) Food Literacy. In International Encyclopedia of Business Management, 1st ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; submitted; accepted; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Lewison, M.; Flint, A.S.; van Sluys, K. Taking on Critical Literacy: The Journey of Newcomers and Novices. Lang. Arts 2002, 79, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, L.; Robinson, D. Making Visible the People Who Feed Us: Educating for Critical Food Literacy Through Multicultural Texts. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2016, 6, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, J. Is cooking dead? The state of Home Economics Food and Nutrition education in a Canadian province. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2013, 37, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, J.; Falkenberg, T.; Rutherford, J.; Colatruglio, S. Food literacy competencies: A conceptual framework for youth transitioning to adulthood. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2018, 42, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, S.; Pendergast, D.; Kanasa, H. Mapping the intellectual structure and knowledge base of food literacy research: A bibliometric analysis. Br. Food J. 2024, 125, 2249–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlebois, S.; Music, J.; Faires, S. The impact of COVID-19 on Canada’s food literacy: Results of a cross-national survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, L.; Ensaff, H. COVID-19 and the National Lockdown: How Food Choice and Dietary Habits Changed for Families in the United Kingdom. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 847547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backer, C.; de Teunissen, L.; Cuykx, I.; Decorte, P.; Pabian, S.; Gerritsen, S.; van den Bulck, H. An Evaluation of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Perceived Social Distancing Policies in Relation to Planning, Selecting, and Preparing Healthy Meals: An Observational Study in 38 Countries Worldwide. Front. Nutr. 2021, 7, 621726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronto, R.; Nanayakkara, J.; Worsley, A.; Rathi, N. COVID-19 and culinary behaviours of Australian household food gatekeepers: A qualitative study. Appetite 2021, 167, 105598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horikawa, C.; Murayama, N.; Sampei, M.; Kojima, Y.; Tanaka, H.; Morisaki, N. Japanese school children’s intake of selected food groups and meal quality due to differences in guardian’s literacy of meal preparation for children during the COVID-19 pandemic. Appetite 2023, 180, 106186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sastre, L.R.; Stroud, B.J. Fresh Start: A Comprehensive Pilot Produce Prescription Program to Improve Food Literacy and Glycemic Control in Rural, Uninsured Patients. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2023, 0, 15598276231195776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonneau, E.; Lamarche, B.; Provencher, V.; Desroches, S.; Robitaille, J.; Vohl, M.C.; Lemieux, S. Associations between nutrition knowledge and overall diet quality: The moderating role of sociodemographic characteristics—Results from the PREDISE study. Am. J. Public Health 2021, 35, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronto, R.; Ball, L.; Pendergast, D.; Harris, N.D. Food Literacy at Secondary Schools in Australia. J. Sch. Health 2016, 86, 823–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowder, S.L.; Beckie, T.; Stern, M. A review of food insecurity and chronic cardiovascular disease: Implications during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2021, 60, 596–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persoskie, A.; Hennessy, E.; Nelson, W.L. US Consumers’ Understanding of Nutrition Labels in 2013: The Importance of Health Literacy. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2017, 14, E86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydin, A.E.; Yildirim, P. Understanding food waste behavior: The role of morals, habits and knowledge. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 124250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, N.L.; Reguant-Closa, A.; Nemecek, T. Sustainable diets for athletes. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2020, 9, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanayakkara, J.; Margerison, C.; Worsley, A. Teachers’ perspectives of a new food literacy curriculum in Australia. Health Educ. 2017, 118, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, S.; Pendergast, D.; Kanasa, H. Teaching food literacy in Australian secondary schools: Skills and theory to influence adolescent food behaviours. JHEER 2022, 12, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, J. Food Literacy: A Critical Tool in a Complex Foodscape. J. Fam. Consum. Sci. 2017, 109, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendergast, D.; Garvis, S.; Kanasa, H. Insight from the Public on Home Economics and Formal Food Literacy. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2011, 39, 415–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendergast, D.; Dewhurst, Y. Home economics and food literacy: An international investigation. IJHE 2012, 5, 245–263. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein, A.; Ludwig, D. Bring back home economics education. JAMA 2010, 303, 1857–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, C.; Smith, T.G.; Jewell, J.; Wardle, J.; Hammond, R.A.; Friel, S.; Thow, A.M.; Kain, J. Smart food policies for obesity prevention. Lancet 2015, 385, 2410–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronto, R.; Ball, L.; Pendergast, D.; Harris, N. Adolescents’ perspectives on food literacy and its impact on their dietary behaviours. Appetite 2016, 107, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374802.locale=en (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Rosas, R.; Pimenta, F.; Leal, I.; Schwarzer, R. FOODLIT-PRO: Food Literacy Domains, Influential Factors and Determinants—A Qualitative Study. Nutrients 2019, 12, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosas, R.; Pimenta, F.; Leal, I.; Schwarzer, R. FOODLIT-PRO: Conceptual and empirical development of the food literacy wheel. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 72, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, E.A.; Thomas, H.; Samra, H.R.; Edmonstone, S.; Davidson, L.; Faulkner, A.; Petermann, L.; Manafò, E.; Kirkpatrick, S.I. Identifying attributes of food literacy: A scoping review. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 2406–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, C.; Byrne, J. The benefits of publishing systematic quantitative literature reviews for PhD candidates and other early-career researchers. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2014, 33, 534–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaro, M.; Dumay, J.; Guthrie, J. On the shoulders of giants: Undertaking a structured literature review in accounting. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2016, 29, 767–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, C.; Grignon, J.; Steven, R.; Guitar, D.; Byrne, J. Publishing not perishing: How research students transition from novice to knowledgeable using systematic quantitative literature reviews. High. Educ. Stud. 2015, 40, 1756–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuy, P.M.; Boutro, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) Version 2018: User guide. Available online: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/ (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Hong, Q.N.; Gonzalez-Reyes, A.; Pluye, P. Improving the usefulness of a tool for appraising the quality of qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies, the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT). J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2018, 24, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. Improving the content validity of the mixed methods appraisal tool: A modified e-Delphi study. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2019, 111, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aromataris, E.; Fernandez, R.; Godfrey, C.M.; Holly, C.; Khalil, H.; Tungpunkom, P. Summarizing systematic reviews: Methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. JBI Evid. Implement. 2015, 13, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johanna Briggs Institute Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses. Available online: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed on 28 November 2024).

- Covidence. Available online: https://www.covidence.org (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Microsoft Excel Computer Software. Available online: https://www.microsoft.com/en-au/microsoft-365/excel (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Microsoft GROWTH Function. Available online: https://support.microsoft.com/en-au/office/growth-function-541a91dc-3d5e-437d-b156-21324e68b80d (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- McManus, S.; Pendergast, D.; Kanasa, H. Teachers’ understanding of food literacy: A comparison between in-field and out-of-field home economics teachers. J. HEIA 2022, 27, 26–40. [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelsen, B.E. Fighting food waste: Good old boys or young minds solutions? Insights from the Young Foodwaste Fighters Club. Youth 2023, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derler, H.; Berner, S.; Grach, D.; Posch, A.; Seebacher, U. Project-based learning in a transinstitutional research setting: Case study on the development of sustainable food products. Sustainability 2019, 12, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, H.; Falkenberg, T. The role and status of food and nutrition literacy in Canadian school curricula. Alta. J. Educ. Res. 2016, 62, 87–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, L.; Callaghan, E.; Broman, G. How can dietitians leverage change for sustainable food systems in Canada? Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2019, 80, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosas, R.; Pimenta, F.; Leal, I.; Schwarzer, R. FOODLIT-Trial: Protocol of a randomised controlled digital intervention to promote food literacy and sustainability behaviours in adults using the health action process approach and the behaviour change techniques taxonomy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.; Choi, M.K.; Park, Y.K.; Park, C.Y.; Shin, M.J. Higher food literacy scores are associated with healthier diet quality in children and adolescents: The development and validation of a two-dimensional food literacy measurement tool for children and adolescents. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2022, 16, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, A.; Martin, D.; Ghartey-Tagoe, G. Is the college farm sustainable? A reflective essay from Davidson College. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2020, 10, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendergast, D. SDGs and home economics: Global priorities, local solutions. Adv. Social Sci. Educ. Human Res. 2017, 112, 234–240. [Google Scholar]

- Renwick, K.; Powell, L.J.; Edwards, G. ‘We are all in this together’: Investigating alignments in intersectoral partnerships dedicated to K-12 food literacy education. Health Educ. J. 2021, 80, 699–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, M.; Rangan, A.; Grech, A. Enablers and barriers of harnessing food waste to address food insecurity: A scoping review. Nutr. Rev. 2022, 80, 1836–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everitt, T.; Engler-Stringerb, R.; Martin, W. Operationalizing sustainable food systems through food programs in elementary schools. Can. Food Stud. 2022, 9, 124–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, N.; Reguant-Closa, A. ‘Eat as if you could save the planet and win!’ Sustainability integration into nutrition for exercise and sport. Nutrients 2017, 9, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bach-Faig, A.; Wickramasinghe, K.; Panadero, N.; Fàbregues, S.; Rippin, H.; Halloran, A.; Fresán, U.; Pattison, M.; Breda, J. Consensus-building around the conceptualisation and implementation of sustainable healthy diets: A foundation for policymakers. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.; Wells, R.; Hawkes, C. How primary school curriculums in 11 countries around the world deliver food education and address food literacy: A policy analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, L.; Callaghan, E.; Broman, G. Assessing community contributions to sustainable food systems: Dietitians leverage practice, process and paradigms. Syst. Pract. Action Res. 2021, 34, 575–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaconu, A.; Mercille, G.; Batal, M. The agroecological farmer’s pathways from agriculture to nutrition: A practice-based case from Ecuador’s highlands. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2019, 58, 142–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soma, T.; Li, B.; Maclaren, V. Food waste reduction: A test of three consumer awareness interventions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.; Ruge, D.; Jones, V. How educational staff in European schools reform school food systems through ‘everyday practices’. Environ. Educ. Res. 2022, 28, 545–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, K.; Smith, M.G. The political action of food literacy: A scoping review. J. Fam. Consum. Sci. 2020, 112, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.; Park, Y.K.; Park, C.Y.; Choi, M.K.; Skin, M.J. Development of a comprehensive food literacy measurement tool integrating the food system and sustainability. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, A.S. ‘A new understanding and appreciation for the marvel of growing things’: Exploring the college farm’s contribution to transformative learning. Food Cult. Soc. 2021, 24, 481–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cunha, M.A.; Paraguassú, L.A.A.; de Aquino Assis, J.G.; de Paula Carvalho Silva, A.B.; de Cassia Vieira Cardoso, R. Urban gardening and neglected and underutilized species in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomedicine 2020, 16, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, N.; Kluge, M.A.; Svette, S.; Shrader, A.; Vanderwoude, A.; Fieler, B. Food next door: From food literacy to citizenship on a college campus. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vettori, V.; Lorini, C.; Milani, C.; Bonaccorsi, G. Towards the implementation of a conceptual framework of food and nutrition literacy: Providing healthy eating for the population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 5041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Kamran, Q. The influence of sustainable design on food well-being. Br. Food J. 2022, 125, 1824–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Yeatman, H.; Russell, J.; MacPhail, C. Food pedagogy—Key elements for urban health and sustainability: A scoping review. Appetite 2022, 168, 105672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C.C.; Chih, C. Sustainable food literacy: A measure to promote sustainable diet practices. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 30, 776–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.; Jo, E.; Lee, H.; Park, S. Development of a food literacy assessment tool for healthy, joyful, and sustainable diet in South Korea. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheah, I.; Shimul, A.S.; Liang, J.; Phau, I. Drivers and barriers toward reducing meat consumption. Appetite 2020, 149, 104636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohsen, H.; Sacre, Y.; Hanna-Wakim, L.; Hoteit, M. Nutrition and food literacy in the MENA region: A review to inform nutrition research and policy makers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronto, R.; Saberi, G.; Carins, J.; Papier, K.; Fox, E. Exploring young Australians’ understanding of sustainable and healthy diets: A qualitative study. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 2957–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, C.; Prichard, I.; Drummond, C.; Drummond, M. Australian adolescents’ beliefs and perceptions towards healthy eating from a symbolic and moral perspective: A qualitative study. Appetite 2022, 171, 105913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas, R.; Pimenta, F.; Leal, I.; Schwarzer, R. FOODLIT-tool: Development and validation of the adaptable food literacy tool towards global sustainability within food systems. Appetite 2022, 168, 105658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, T.; Jung, H. Effects of university students’ perceived food literacy on ecological eating behavior towards sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, A. The shift of food value through food banks: A case study in Kyoto, Japan. Evol. Institutional Econ. Rev. 2020, 17, 243–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, R.; Asa, H.; Dogan, O.; Michalek, C.R.; Akkan, O.K.; Bulut, Z.A. Designing and implementing the MySusCof App—A mobile app to support food waste reduction. Foods 2022, 11, 2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, A.; Feuer, H. Institutional food literacy in Japan’s Children’s Canteens: Leveraging food system skills to reduce food waste and food insecurity via new food distribution network. Int. J. Sociol. Agric. Food 2021, 27, 55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Farr-Wharton, G.; Foth, M.; Choi, J.H.J. Identifying factors that promote consumer behaviours causing expired domestic food waste. J. Consum. Behav. 2014, 13, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poonia, A.; Sindhu, S.; Arya, V.; Panghal, A. Analysis of drivers for anti-food waste behaviour—TISM and MICMAC approach. J. Indian Bus. Res. 2021, 14, 186–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esau, M.; Lawo, D.; Neifer, T.; Stevens, G.; Boden, A. Trust your guts: Fostering embodied knowledge and sustainable practices through voice interaction. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2022, 27, 415–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, K.; Engler-Stringer, R.; Kirk, S.; Wittman, H.; McNicholl, S. The case for a Canadian national school food program. Can. Food Stud. 2018, 5, 208–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusa, M.; Falcão, L.; De Jesus, J.; Biolatti, C.; Blondeel, L.; Bracken, F.S.A.; Devriese, L.; Garcés-Pastor, S.; Minoudi, S.; Gubili, C.; et al. Fish out of water: Consumers’ unfamiliarity with the appearance of commercial fish species. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 1313–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubb, M.; Vogl, C.R. Understanding food literacy in urban gardeners: A case study of the Twin Cities, Minnesota. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soma, T.; Nuckchady, B. Communicating the benefits and risks of digital agriculture technologies: Perspectives on the future of digital agricultural education and training. Front. Commun. 2021, 6, 762201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Murcia, L.; de la Vega, I.G.; Perdomo- Ortíz, J.; Rodríguez-Pinilla, J.P. Towards sustainable food consumption: Emerging tensions behind the plate in a Colombian university community. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 46, 758–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, J. Reading the world: Food literacy and the potential for food system transformation. Stud. Educ. Adults 2015, 47, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vittuari, M.; Masotti, M.; Iori, E.; Falasconi, L.; Toschi, T.G.; Segrè, A. Does the COVID-19 external shock matter on household food waste? The impact of social distancing measures during the lockdown. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 174, 105815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topcu, B.; Dias, G.M.; Mollaei, S. Ten-year changes in global warming potential of dietary patterns based on food consumption in Ontario, Canada. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, L.I.; Constantinides, S.V.; Bhandari, S.; Frongillo, E.A.; Schreinemachers, P.; Wertheim-Hack, S.; Walls, H.; Holdswort, M.; Laar, A.; Nguyen, T.; et al. Actions in global nutrition initiatives to promote sustainable healthy diets. Glob. Food Secur. 2021, 31, 100585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safdar, B.; Zhou, H.; Li, H.; Cao, J.; Zhang, T.; Ying, Z.; Liu, X. Prospects for plant-based meat: Current standing, consumer perceptions, and shifting trends. Foods 2022, 11, 3770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zareimanesh, B.; Namdar, R. Analysis of food literacy dimensions and indicators: A case study of rural households. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 1019124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedin, B.; Grönborg, L.; Johansson, G. Food carbon literacy: A definition and framework exemplified by designing and evaluating a digital grocery list for increasing food carbon literacy and changing behavior. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niankara, I. Education’s effect on food and monetary security in Burkina Faso: A joint semi-parametric and spatial analysis. Afr. J. Sci. Innov. Dev. 2022, 14, 1690–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, A.; Parks, C.; McKay, F.H.; van der Pligt, P.; Yaroch, A.; McNaughton, S.A.; Lindberg, R. Development of a comprehensive household food security tool for families with young children and/or pregnant women in high income countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, N.; Lawless, T. Exploring food charity managers perceived barriers to food security for vulnerable women in the Australian Capital Territory Region: A qualitative study. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2023, 18, 272–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, B.; Azevedo, J.; Rodrigues, I.; Rainho, C.; Gonçalves, C. Food insecurity levels among university students: A cross-sectional study. Societies 2022, 12, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, L.J.; Wittman, H. Farm to school in British Columbia: Mobilizing food literacy for food sovereignty. Agric. Hum. Values 2018, 35, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagenais, B.; Marquez, A.; Lavoie, J.; Hunter, B.; Mercille, G. Adopting sustainable menu practices in healthcare institutions: Perceived barriers and facilitators. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2022, 83, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, B.; Lewis, N. Urban food forestry networks and Urban Living Labs articulations. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2021, 14, 337–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzocco, L.; Alongi, M.; Sillani, S.; Nicoli, M.C. Technological and consumer strategies to tackle food wasting. Food Eng. Rev. 2016, 8, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araújo, P.D.; Araújo, W.M.C.; Patarata, L.; Fraqueza, M.J. Understanding the main factors that influence consumer quality perception and attitude towards meat and processed meat products. Meat Sci. 2022, 193, 108952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priyadarshini, P.; Abhilash, P.C. Agri-food systems in India: Concerns and policy recommendations for building resilience in post COVID-19 pandemic times. Glob. Food Secur. 2021, 29, 100537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.; Adams, J.; Gallegos, H. Are we closer to international consensus on the term ‘food literacy’? A systematic scoping review of its use in the academic literature (1998–2019). Nutrients 2021, 13, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, S.; Pendergast, D.; Kanasa, H. Teaching food literacy in Queensland secondary schools: The influence of curriculum. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2023, 51, 196–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McManus, S.; Pendergast, D.; Kanasa, H. The Intersection Between Food Literacy and Sustainability: A Systematic Quantitative Literature Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 459. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17020459

McManus S, Pendergast D, Kanasa H. The Intersection Between Food Literacy and Sustainability: A Systematic Quantitative Literature Review. Sustainability. 2025; 17(2):459. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17020459

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcManus, Sarah, Donna Pendergast, and Harry Kanasa. 2025. "The Intersection Between Food Literacy and Sustainability: A Systematic Quantitative Literature Review" Sustainability 17, no. 2: 459. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17020459

APA StyleMcManus, S., Pendergast, D., & Kanasa, H. (2025). The Intersection Between Food Literacy and Sustainability: A Systematic Quantitative Literature Review. Sustainability, 17(2), 459. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17020459