Abstract

Workplace mental health is a critical social issue with significant human and economic costs, making its sustainable management essential for long-term well-being and productivity. Nature-based interventions (NBIs) offer a promising cost-effective approach to enhancing employee creativity and well-being. This paper systematically reviewed NBIs—such as outdoor exercise, green space engagement, and nature-centered activity—and their effects on workplace creativity, subjective well-being, and mental health. Following the PRISMA guidelines, a comprehensive search of PubMed, PsycINFO, Scopus, and Google Scholar yielded 508 studies published from 2017 to 2024. Seven studies met our inclusion criteria, involving real workplace settings, NBIs as primary interventions, and clear comparison groups. Analysis covered study design, sample size, intervention type, and outcomes, focusing on creativity and well-being. Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Bias Risk Tool and the ROBIN-I tool. Results were grouped into five themes: mental health metrics, cognition and creativity, rehabilitation and regeneration, job and life satisfaction, and physiological outcomes. Findings highlighted the positive impact of NBIs on mental health and creativity, though results for other outcomes were mixed. Methodological variability and potential bias limited the strength of conclusions. Future research should prioritize large-scale, methodologically rigorous trials aligned with contemporary theories on workplace environments and creativity.

1. Introduction

The labor market is increasingly complex, dynamic, and global, necessitating a broadened perspective in occupational health psychology (OHP) [1]. Emerging trends in OHP emphasize positive occupational mental health, focusing not only on disease prevention and risk mitigation but also on enhancing psychological well-being at individual and organizational levels. Despite evidence supporting the efficacy of positive psychology interventions in workplace settings, their application remains limited [2]. Most employees spend their careers managing stress rather than actively fostering well-being. Nonetheless, workplaces offer a unique and practical context for implementing preventive and complementary mental health strategies, while fostering sustainability through long-term employee well-being and resource-efficient practices.

Extensive research highlights the benefits of nature exposure, defined as time spent in or observing green and blue spaces, for mental health outcomes [3,4]. A Cochrane review synthesizing 12 studies confirmed associations between nature exposure and reduced all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, as well as improved adult mental health. However, the application of this evidence to workplace settings remains underexplored [5]. Stress Reduction Theory (SRT) and Attention Restoration Theory (ART) provide foundational frameworks emphasizing the role of nature contact in health maintenance [5,6]. ART posits that prolonged engagement in cognitively demanding tasks depletes mental resources, leading to fatigue, frustration, and diminished capacity.

Natural environments, by attracting involuntary attention, allow for the restoration of directed attention, replenishment of mental energy, and reduction of stress [7,8]. Similarly, SRT suggests that natural settings, especially those featuring vegetation and water, evoke positive physiological and psychological responses by mitigating stress-related activities. This connection to nature fosters hedonic well-being (emotional happiness) and eudemonic well-being (optimal functioning), enhancing mental resilience and overall health [9,10]. These theoretical insights support the development of nature-based interventions (NBIs), defined as sustainable activities intentionally designed to improve functioning, well-being, and recovery through exposure to natural or simulated environments. This broad definition encompasses virtual nature experiences and work recovery initiatives [11].

NBIs align with ART and SRT in promoting cognitive restoration and stress reduction. These interventions facilitate psychological detachment from work, enabling individuals to refocus and replenish cognitive resources depleted by occupational demands [5,12]. ART highlights how NBIs mitigate mental fatigue and restore attentional capacity. In parallel, SRT emphasizes the physiological and psychological benefits of natural environments, including reduced stress hormones and improved adaptive readiness [5,12]. Additional mechanisms, such as cleaner air, cooler temperatures, and plant-emitted phytoncides, further amplify these benefits. In workplace settings, NBIs align with the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) Model by replenishing personal resources strained by occupational pressures [13]. By fostering recovery, these interventions enhance employees’ resilience and ability to manage job stress.

The Positive Occupational Health Psychology (POHP) framework, which focuses on optimizing individual and organizational health, can incorporate NBIs effectively [14]. POHP interventions operate at three levels: (i) Primary Prevention, addressing mental health proactively to prevent the emergence of issues; (ii) Secondary Prevention, equipping employees with stress management skills to mitigate escalation; and (iii) Tertiary Prevention, supporting diagnosed employees to minimize functional impairments.

Versatile and adaptable, NBIs can be tailored to suit any of these levels, making them effective tools for enhancing workplace mental health [15,16]. Within POHP, mental health is conceptualized as a continuum, ranging from flourishing (optimal functioning) to languishing (reduced engagement and well-being). NBIs can help individuals shift toward flourishing by addressing job demands and replenishing personal and organizational resources. Effective recovery experiences through nature exposure—characterized by psychological detachment, relaxation, mastery, and control—enhance resilience and support sustainable well-being [13,15,16].

NBIs encompass a range of activities, including horticultural therapy, wilderness therapy, and green exercise, each offering unique benefits while promoting sustainable well-being [17,18]. This diversity necessitates an integrative theoretical framework that draws on (a) Environmental Psychology, including Stress Reduction Theory and Attention Restoration Theory; (b) Organizational Psychology, including the JD-R Model and Conservation-of-Resources Theory; and (c) Positive Psychology, including The Broaden-and-Build Theory of positive emotions.

This multidisciplinary approach positions NBIs as preventive, cost-effective workplace interventions that align with POHP’s goals of fostering long-term well-being rather than merely addressing mental illnesses [19].

Systematic reviews affirm the mental health benefits of NBIs. Annerstedt and Währborg’s review [18] linked nature exposure to improvements in psychological, social, and physical well-being for conditions such as mental fatigue, depression, and attentional disorders. Similarly, Coon et al. [20] reported that green exercise outperformed indoor activities in revitalization, engagement, and emotional health. However, Lahart et al. [21] highlighted methodological inconsistencies in green exercise studies, underscoring the need for rigorous research.

Experimental studies in organizational contexts remain limited due to high costs and the challenges of controlling confounding variables [22]. Much of the existing research has focused on student samples rather than employees, raising questions about external validity and the practical implementation of NBIs in real-world workplaces. Key gaps include determining optimal exposure frequency, identifying the most beneficial aspects of nature, and evaluating economic feasibility.

While research has explored the impact of NBIs on employees, no comprehensive review has synthesized this evidence to date. This systematic review addresses that gap by critically examining empirical studies on NBIs’ effects on workplace mental health, creativity, and well-being. The review focuses exclusively on primary prevention, excluding interventions targeting employees with diagnosed mental health disorders. Specifically, it seeks to answer the following questions:

What nature-based interventions have been implemented in workplace settings?

What are the differential effects of various NBIs on employee mental health and well-being?

How do nature-based activities influence employee creativity?

How does nature exposure impact employees’ subjective well-being?

Are there measurable differences in creativity and well-being between employees who engage in nature-based activities and those who do not?

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review adhered to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses, see Supplementary Materials) guidelines [23]. A comprehensive, structured search was conducted across five major databases: (1) PubMed, (2) Embase, (3) PsycINFO, (4) Scopus, and (5) Google Scholar. The search strategy employed targeted the identification of relevant studies using appropriate keywords, as evidenced in key research works highlighted by the researchers (Table 1).

Table 1.

Database queries using relevant words.

The initial search strategy was developed and subsequently revised. Additional measures included contacting study authors and performing a manual search for recent publications (2017–2024). This manual search focused on specific journals and included a keyword search for “employee” in the BMC Public Health Journal, spanning volumes 13 to 18. The ID 634683 was registered on 6/1/2025 on the PROSPERO platform.

Eligibility criteria were determined using the PICOS framework. The population of interest in this review consisted of employees or workers in any workplace setting. Interventions included any NBIs or activities designed to foster engagement with natural environments. Examples of these interventions ranged from outdoor activities and interactions with green spaces to outdoor team-building exercises. The comparison groups comprised workplaces that did not implement such nature-based interventions or were subjected to other types of well-being interventions for comparison. The primary outcomes measured were changes in creativity, subjective well-being, or mental health, as assessed through validated questionnaires.

The review included interventions specifically designed for workplace settings and targeting employees performing their organizational roles. While interventions could take place outside the workplace, they needed to be facilitated or endorsed by the employer. Studies involving interventions outside the workplace, such as community programs targeting employed individuals, were excluded. Participants had to be adult employees (aged 18 years or older), and studies using non-employee samples, such as students in simulated office environments, were excluded. Furthermore, studies focusing on employees with diagnosed mental health conditions were excluded, as the review aimed to emphasize preventive strategies and the promotion of mental well-being rather than treatment.

Eligible studies featured specific NBIs or activities involving active and intentional contact with natural environments, either in green or blue spaces. Examples of direct exposure included spending time in natural settings, such as parks; incorporating indoor plants; or providing access to window views of nature. Indirect exposure, such as simulated visual or auditory nature scenes, was also eligible. Studies that merely assessed existing environmental features, such as plant density, without implementing an intervention, were excluded.

Outdoor interventions involving physical activity were eligible only if they included natural elements, such as trees or greenery, meeting the criteria for “green exercise”. For the purposes of this review, “nature” encompassed ecosystems with living components (managed or wild), ranging from urban parks to wilderness. “Green space” referred to areas with vegetation (e.g., forests and grass), and “blue space” denoted areas featuring visible water bodies (e.g., lakes, rivers, and coasts) [24,25]. The dimensions of nature contact included the size, proximity, frequency, sensory mode (visual, auditory), activity intensity, and level of individual awareness [26].

Eligible comparison conditions included control groups with no intervention or interventions conducted in non-natural settings, such as urban or indoor environments without views of nature (e.g., urban landscapes). Studies reporting numerical data on mental health or well-being outcomes, including psychological processes or subjective states measured through standardized tools, were prioritized in the review. Although physiological indices (e.g., blood pressure) were occasionally included, they were not primary inclusion criteria.

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), quasi-RCTs, controlled trials (CTs), randomized crossover trials (RXT), quasi-RXTs, and crossover trials (XTs) were included in the review. Observational studies and case–control designs were excluded. Only full-text, peer-reviewed articles were considered, while unpublished sources, such as dissertations, conference proceedings, and research reports, were excluded.

Search results from each database were exported as .ris files and imported into Rayyan, an online tool for systematic review screening [27]. Duplicate records were removed, and titles and abstracts were screened for relevance. Exclusion rates ranged from 88% to 91.8%, ultimately resulting in 26 articles for which inclusion decisions varied. To address discrepancies, a third researcher reviewed and resolved disagreements, leading to the exclusion of two additional studies.

Subsequently, potentially eligible studies were further assessed for relevance. Two independent reviewers evaluated the eligibility of articles, with consensus reached through discussion and consultation with the senior researcher. Additionally, reference lists of included articles were scanned to identify supplementary studies. All review steps adhered to predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for randomized studies and ROBINS-I for non-randomized studies. These tools evaluated key domains, including randomization processes, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement accuracy, and selective reporting [28]. Each domain was categorized as low-risk, some concerns, or high risk based on answering the specific signaling questions, which provided an overall bias rating for each study outcome discussed.

A standardized data extraction template was developed to capture study characteristics, including author names, publication year, country, theoretical orientation, study type, methodology, population characteristics, intervention descriptions (e.g., setting, nature components, and timing), and reported outcomes. Data accuracy was verified by a research assistant to ensure reliability.

Due to the limited number of eligible studies and significant heterogeneity in clinical, methodological, and statistical approaches, a meta-analysis was deemed inappropriate. Instead, a narrative synthesis was conducted following best-practice guidelines. Because of the variation in the data, the authors determined that applying a quantitative approach to meta-analysis would generate artefactual conclusions [29]. Studies were categorized by intervention type and outcomes, alongside risk-of-bias assessments.

3. Results

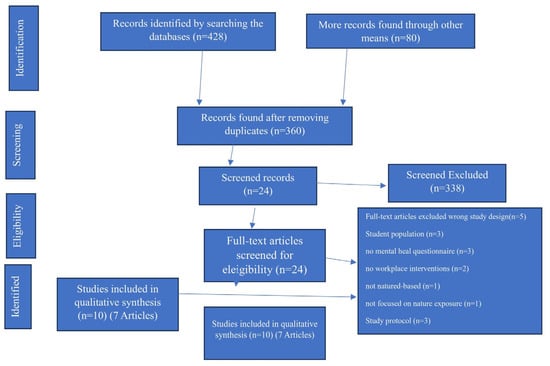

A PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) was constructed to illustrate the study selection process. The initial search identified 508 papers, of which 24 articles remained after screening titles and abstracts. Of the 69 publisher abstracts reviewed, one was flagged as available only in conference abstract form, and the authors could not be reached to obtain a full publication. Additionally, five articles were excluded due to limited information, as they contained only brief descriptions of environmental characteristics associated with natural objects. Consequently, further data were sought for these records. The reference lists of included studies were reviewed, leading to the identification of one additional relevant article. Ultimately, three articles met the inclusion criteria, encompassing 10 NBIs and involving a total of 611 employees.

Figure 1.

A PRISMA flow diagram.

Among the included studies, three articles reported on overlapping NBI trials [30,31,32]. The studies by de Bloom et al. [30] and Sianoja et al. [31] investigated the same NBI, conducted at different times of the year and with distinct participant samples, yielding varying results. Given that de Bloom et al. [30] analyzed each study phase independently, this publication was selected as the primary reference. However, two additional measures reported by Sianoja et al. [31]—perceived stress and concentration—were included to supplement the review, as they provided valuable additional insights. Notably, Sianoja et al. [31] combined data from participants across both phases originally studied by de Bloom et al. [30].

One study by Brossoit et al. [33] indicated that employees residing and working in areas with abundant natural amenities (such as access to water, varied topography, and temperate climates) spent more time outdoors, which correlated with higher work engagement and creativity. Another study by Wu et al. [34] applied the dynamic componential model of creativity to examine the impact of green training, focusing on how green values and intrinsic motivation mediated the relationship between green training and green creativity. Additionally, Shanahan et al. [35] employed a Delphi expert elicitation approach involving 19 experts from seven countries to explore various types of NBIs, their potential health effects, and intended outcomes.

Finally, of the 96 articles reviewed in total, 7 were included in the final analysis. One of these, a study by Largo-Wight et al. [36], assessed the effectiveness of a 10-min Outdoor Booster Break, a daily outdoor work break, compared with an indoor break.

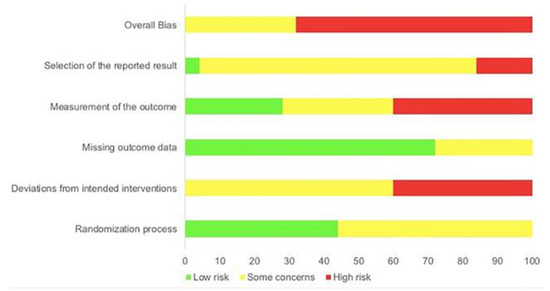

Among the outcome measures assessed across the studies, none demonstrated an overall low risk of bias. On average, moderate bias concerns were observed in 32% of the outcomes, while high risk of bias was identified in the majority of cases (68%). High-risk domains included self-selection bias influencing reported results (16%), outcome measurement bias (40%), and deviations from planned interventions (40%). However, two domains avoided a high-risk rating: missing outcome data and randomization processes. Missing outcome data were rated as low-risk in 72% of cases, with 28% showing some concerns. Similarly, 44% of studies demonstrated a low risk of bias in the randomization process, while 56% raised moderate concerns. Figure 2 provides a summary of the risk assessment results, categorized by outcome type and assessment findings for each specific outcome domain identified in the review.

Figure 2.

Risk assessment summary.

Eight studies examined NBIs through longitudinal randomized controlled trial (RCT) designs spanning several weeks. Of these, three utilized a three-arm parallel-group design [30]. Six studies focused on interventions at the participant level: three targeted individuals, and three were group-level interventions, two of which involved green office space design. The duration of these interventions ranged from two to eight weeks.

One pilot study implemented a brief intervention involving two green exercise sessions over two consecutive weeks, following an earlier exercise promotion workshop. In contrast, the study by Largo-Wight et al. [36] employed a cross-sectional design, with follow-up measurements conducted two- and ten-weeks post-intervention. Another study incorporated an additional follow-up measurement three and a half months after the intervention [35]. One article combined a quantitative cross-sectional survey, assessing participants’ perceptions of NBI feasibility, with an RCT investigating the intervention’s tangible impact [37]. Another study adopted an acute RCT design [32].

The sample sizes of the included studies ranged from 14 to 94 participants, with a mean of 70 participants [31]. A total of 611 employees participated in the seven studies. Participants ranged in age from 28 to 49 years, with a mean age of 45.5 years. The majority was female, with an average female representation of 67% (median 78%). One pilot study, however, reported an equal gender distribution (50% male and 50% female). The gender imbalance observed in other studies may reflect broader trends within specific industries, such as financial and educational sectors, where gender segregation is pronounced.

Ethnicity data were largely absent, with only two studies reporting this information. These studies indicated that, on average, 82% of participants were Caucasian. One study, comprising two separate experiments, provided additional sociodemographic data, highlighting that a significant proportion of participants lived with children, and 24% held a master’s degree as their highest educational qualification.

Four studies were conducted among office workers, including university staff, financial employees, municipal workers, call-center clerks, and consultants. Healthcare workers, such as doctors, nurses, caregivers, and employees in elderly care homes, were the focus of several other studies. Two studies examined employees from diverse occupational environments, encompassing sectors such as media, healthcare, finance, engineering, and service industries.

Out of the 24 studies included in the review, only a subset collected organizational data, such as employment contract type (permanent or temporary), supervisory responsibilities, weekly working hours, employment classification (blue-collar or white-collar), and years of employment within the organization.

The studies reviewed identified and categorized nature-based interventions (NBIs) into three primary types: green exercise, nature savoring, and green office environments. Green exercise refers to any physical activity conducted in natural settings. Nature savoring involves the intentional focus on and emotional regulation in response to positive experiences in nature [38,39]. Lastly, green office environments encompass workplace interventions that enhance the office setting through the incorporation of plants and other natural elements.

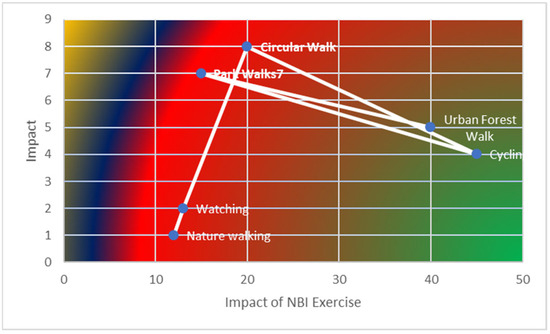

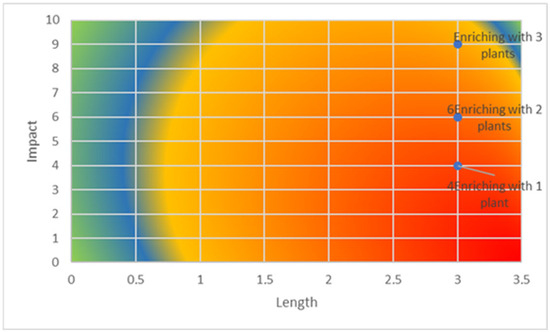

Green exercise programs: Three green exercise interventions were implemented in the studies, each differing slightly in execution [30]. A common feature of these interventions was their scheduling during employees’ lunch breaks. Participants typically followed a circular route of approximately 2 km in a nearby park, proceeding at their own pace and in either individual or group formations. In the studies by de Bloom et al. [30] and Sianoja et al. [31], participants were encouraged to engage in nature savoring during the walks by focusing on their surroundings and avoiding conversations. However, the specific characteristics of the natural environments used—such as details about the “nearest park”—were not always described (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Impact of green exercises on mental health and creativity.

One study also included a cycling component conducted in a forested area, paired with a strength session held in a grassy yard. This was the only study to provide photographic documentation of the natural settings used. Shanahan et al. [35] expanded the scope by examining 27 NBIs categorized into preventive, health-promoting, or illness-focused interventions. These interventions were implemented in various contexts, including living, working, learning, recreational, or care facilities. Examples included converting hospital gardens, repurposing urban parks, or organizing structured nature-based programs or events.

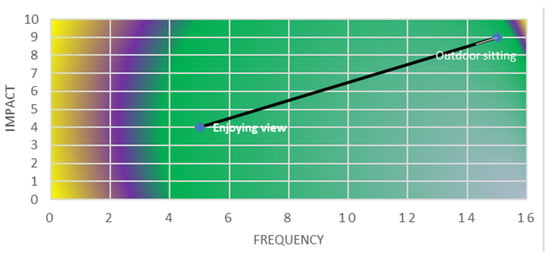

Nature savoring: Two studies explored nature-savoring interventions, each adopting a distinct approach. In the study by Largo-Wight et al. [36], office workers were instructed to take self-directed outdoor breaks for 10–15 min daily over four weeks, focusing their attention on natural elements such as clouds, trees, and water. Environmental conditions for this intervention included sunny weather with an average temperature of 22.8 °C; however, other studies did not report specific weather data (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Impact of nature savoring on mental health and creativity.

In a randomized controlled trial by Torrente et al. [32], 153 knowledge workers from seven companies were assigned to one of three groups: relaxation, park walking, or a control group. This four-week intervention provided further insight into the effects of nature savoring in a structured, organizational context.

Green office environments: The concept of green office interventions was explored in several studies. Brossoit et al. [33] identified six categories of outdoor activities associated with green office spaces through qualitative analysis: leisure activities, relaxation, physical activity, social interactions, task completion, and travel. Wu et al. [34] reported data from 464 participants employed in various public sector organizations in China, collected at two time points. Their findings indicated a positive correlation between green office training and increased green creativity, highlighting the potential organizational benefits of integrating natural elements into the workplace environment (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Impact of green office spaces on mental health and creativity.

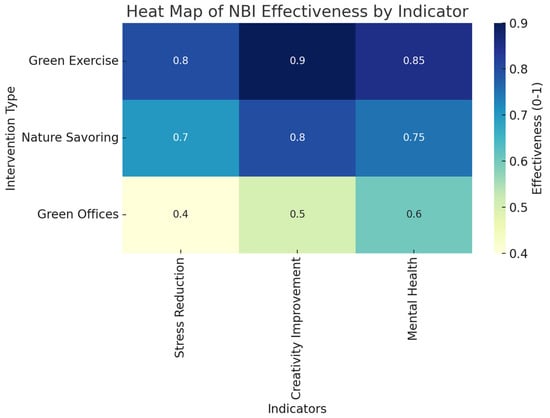

The heatmap of NBI (Figure 6) represented the effectiveness of the three nature-based interventions (NBIs)—green exercise, nature savoring, and green offices—across three indicators: stress reduction, creativity improvement, and mental health. Green exercise was the most effective, particularly for creativity (0.9) and mental health (0.85), followed by nature savoring, which showed moderate effectiveness, with scores ranging from 0.7 to 0.8. In contrast, green offices exhibited the lowest effectiveness, with scores between 0.4 and 0.6, indicating a relatively limited impact. Darker blue shades represented higher effectiveness, while lighter shades indicated lower effectiveness.

Figure 6.

Effectiveness of nature-based interventions across key well-being indicators.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to review quantitative research on NBIs in organizational settings and their effects on employees’ mental health, creativity, and well-being. The seven identified studies exhibited significant heterogeneity in design, types of natural exposure, outcome measures, and assessment methods, precluding a meta-analysis. The measured outcomes were categorized into psychological well-being, creativity and cognition, recovery and restoration, job satisfaction, and work–life balance. NBIs were further classified into three types: green exercise (three studies), nature savoring (two studies), and green office spaces (two studies).

Our review supported the association between NBIs and improved employee mental health, with five out of six studies reporting significant positive effects on self-reported mental health (e.g., [31,36]). However, NBIs demonstrated limited efficacy in improving other outcomes, such as cognitive function, recovery, job satisfaction, and psychophysiological health, with small-to-medium effects reported in cognitive measures.

The present findings could be linked to Attention Restoration Theory (ART) and Stress Reduction Theory (SRT) by examining how different nature-based interventions (NBIs) align with or diverge from these frameworks. ART, which focuses on cognitive restoration through nature engagement, aligns with green exercise interventions like park walks, which enhance vitality and reduce mental fatigue [40,41]. Similarly, nature savoring supports ART by aiding directed attention recovery. SRT, which emphasizes the physiological and psychological benefits of nature exposure, is supported by reductions in stress markers like cortisol and improvements in heart rate variability during park-based interventions [40,41,42]. However, green office interventions, showing inconsistent effects, may diverge from SRT due to limited nature exposure. This connection indicates how ART and SRT could guide more effective NBIs in workplace settings (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies.

The results for recovery and restoration were inconclusive, with one study reporting positive outcomes and another finding no significant effects (e.g., [30]). Similarly, only two of six studies on work–life satisfaction indicated positive impacts, and even these showed marginal improvements. Psychophysiological health indicators varied widely, including anthropometric, hormonal, and cardiovascular measures, with limited consistency across studies.

A significant limitation across the studies was the absence of follow-up assessments, restricting findings to short-term outcomes. Small sample sizes; lack of sample size calculations; and failure to account for confounding variables, like baseline stress and workplace culture, further constrained the reliability of conclusions. The diversity in study designs—ranging from randomized controlled trials to quasi-experimental approaches—and the use of inconsistent outcome measures complicated comparisons. To improve generalizability and accuracy, future research should adopt standardized methodologies, including larger samples, consistent measures, and longer follow-ups. Multi-site studies and cluster randomization could also enhance external validity.

Additional findings highlighted the classification of NBIs into environmental changes (e.g., urban green spaces and hospital gardens) and behavioral interventions (e.g., organized outdoor activities). Recent studies, such as that by Wu et al. [34], demonstrated the effectiveness of “green training” in enhancing creativity in public-sector employees. Among NBI types, nature savoring yielded consistently significant results [36], whereas green exercise and green office spaces produced mixed and less consistent outcomes.

The role of NBIs in workplace sustainability extends beyond individual well-being to broader organizational and environmental impacts. By incorporating green spaces and biophilic designs, organizations may optimize resource efficiency, promote employee engagement in sustainability, and strengthen their corporate social responsibility (CSR) efforts. These interventions not only support urban sustainability, biodiversity, and carbon footprint reduction but also contribute to environmental resilience. Additionally, aligning NBIs with the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—notably SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), SDG 13 (Climate Action), and SDG 15 (Life on Land)—fosters healthier workplaces, while advancing global sustainability targets. To maximize their benefits, NBIs should be embedded into corporate sustainability policies, supported through collaborative partnerships, and evaluated against sustainability reporting frameworks, ensuring a robust contribution to organizational and environmental well-being.

Despite increasing evidence supporting these interventions, significant gaps remain, particularly in their application across industries, intervention types, and contextual factors. This paper identified three main gaps: limited industry-specific research, insufficient exploration of diverse nature-based interventions, and inadequate consideration of contextual influences. Addressing these gaps could inform the effective integration of green spaces into workplace practices, optimizing creativity and well-being outcomes.

While the review was not aimed at influencing policy, the findings have implications for public policy and workplace health strategies, suggesting that decision-makers could use them to promote green spaces as a cost-effective way to enhance creativity and well-being.

- (a)

- Industry-Specific Research Gaps in Nature-Based Interventions

Existing studies on workplace green spaces and nature-based activities predominantly focus on general office environments, neglecting industry-specific nuances. Sectors such as healthcare, manufacturing, and technology feature unique operational structures and stressors, potentially affecting the applicability and effectiveness of nature-based solutions.

Healthcare professionals face unique stressors, including high emotional labor, long working hours, and exposure to traumatic events. These challenges highlight the potential value of tailored nature-based interventions. Evidence suggests that access to green spaces could enhance mental well-being and reduce burnout [5,43]. However, few studies examine how such interventions influence creativity, job satisfaction, and performance within healthcare settings. Targeted research could explore whether incorporating green spaces into hospitals or promoting short nature-based activities alleviates stress and fosters creativity among healthcare workers.

Manufacturing environments are often defined by confined, industrial settings with minimal natural light or greenery. Limited research has examined whether introducing green spaces in such environments impacts creativity or reduces worker fatigue. Given the typically rigid and highly structured physical spaces in manufacturing, it remains unclear how nature-based interventions could be practically implemented or what their potential benefits might be [20,44].

In the technology sector, characterized by fast-paced work environments and extended hours, the focus has traditionally been on designing innovation-driven workspaces that are often devoid of natural elements. While some technology companies incorporate greenery into office designs, few studies have explored the specific impacts of green spaces on creativity and well-being within this sector. Future research could investigate whether exposure to natural environments or virtual nature experiences enhances cognitive refreshment and problem-solving capabilities in high-demand, cognition-intensive roles.

- (b)

- Gaps in Types of Nature-Based Interventions

Urban workplaces increasingly adopt green roofs and vertical gardens to integrate nature into limited spaces. Despite their popularity, research on their psychological and creative benefits for employees remains sparse. Green roofs, for instance, may provide visual access to greenery and opportunities for restorative breaks without requiring extensive horizontal space. Further investigation is needed to determine whether these features offer benefits comparable to traditional green spaces [45].

Technologies such as virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) simulate natural environments and offer an alternative for workplaces in urban areas with limited green space. Although studies suggest virtual nature can reduce stress and improve mood, research on its effects on creativity and long-term workplace satisfaction remains limited. Investigating the viability of VR and AR as cost-effective solutions for enhancing cognitive restoration could address this research gap [46,47].

Outdoor meetings and walking breaks are known to improve mood and cognitive functioning. However, empirical evidence on their impact on creativity and problem-solving remains underdeveloped. Most existing studies focus on general well-being rather than measurable creative outputs or productivity metrics. Research exploring the structured implementation of outdoor meetings—considering variables such as duration, frequency, and physical activity level—could provide valuable insights [48].

- (c)

- Contextual Factors and Methodological Weaknesses

Responses to nature-based activities vary across individuals and are based on factors such as personality, nature connectedness, and baseline stress levels. For instance, employees with a strong affinity for nature may derive more benefits from green spaces compared to those who prefer urban environments. Studies rarely consider these individual differences, which could inform the development of tailored interventions [49].

Most studies are conducted in Western contexts, often overlooking cultural attitudes toward nature that vary globally. In some regions, green spaces are deeply rooted in local traditions, while in others, they may hold less significance. Geographic factors such as urban density and climate also affect the feasibility and impact of nature-based interventions. Further exploration of these variables is essential to create globally applicable recommendations.

The effectiveness of nature-based interventions may depend on job roles and task types. High-concentration roles, such as coding or financial analysis, might benefit from short, frequent nature breaks, while creative roles may respond better to immersive, extended nature experiences. Research should focus on how different workplace contexts influence the efficacy of nature-based interventions [50].

All of the included studies were conducted in natural settings, enhancing ecological validity. However, significant limitations were noted in defining and measuring the natural environment, methodological quality, and the consideration of potential confounding and mediating variables. These issues diminish the clarity, applicability, and overall robustness of the findings.

The heterogeneity in study designs, outcome measures, and intervention types undermined the reliability and generalizability of conclusions. Methodologies varied widely, complicating comparisons and limiting robust findings. To evaluate precision, studies were categorized as high, moderate, or low based on factors like sample size and confounding variable control, with most falling into the moderate category. Many overlooked critical confounders, such as baseline stress or workplace culture. Future research should adopt standardized methods, including validated measures, larger samples, and longer follow-ups. Multi-site studies, cluster randomization, and adherence to guidelines like PRISMA are essential to minimize bias and strengthen the evidence base for workplace health interventions.

One primary limitation lies in the diversity, quality, and extent of the natural environments studied, ranging from wilderness areas to urban parks. While all studies occurred in green environments, ambiguity exists regarding the inclusion of blue spaces, with only Largo-Wight et al. [36] suggesting potential exposure to water-based environments. Evidence from prior research suggests positive mental health outcomes associated with both green and blue spaces, but the specific contributions of blue spaces in these studies remain unclear [51].

Further, the green exercise and nature-savoring studies lacked detailed descriptions of the natural contexts. This may stem from varied sample interventions across different environments within single studies [30,36]. Despite the availability of advanced methodologies for quantifying and characterizing natural settings, such approaches were underutilized, limiting the specificity and transferability of findings.

Methodological shortcomings were evident across the reviewed studies, increasing their susceptibility to bias and confounding. Instrument selection to assess mental health outcomes, such as the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), often lacked alignment with intended applications, raising concerns about validity [52]. Additionally, modern perspectives view mental health as a continuum, necessitating tools that capture this complexity. Only Largo-Wight et al. [36] reported reliability metrics (e.g., Cronbach’s alpha) for their assessments, underlining the need for more rigorous tool selection and reporting standards.

A significant limitation was the absence of follow-up assessments, which restricted findings to short-term outcomes. Small sample sizes (with an average sample size of n = 28) further constrained the studies, with no evidence of sample size calculations to ensure statistical power [53]. This raises questions about whether nonsignificant results or small effect sizes were due to genuine outcomes or inadequate power. De Bloom et al. [30], for instance, reported small, nonsignificant effect sizes, which might reflect these limitations.

Confounding factors, such as individual-level variables (e.g., nature connectedness) and contextual factors (e.g., weather conditions), were insufficiently controlled. Nature connectedness, a strong correlate of psychological well-being, was assessed in only a few studies despite its mediating potential for mental health benefits [54,55]. Climatic factors, although mentioned in some studies, were rarely analyzed in detail. Largo-Wight et al. [36] was an exception, considering weather and temperature in their design.

Other confounding factors, including environmental pressures like air quality, workplace fatigue, and social interactions, were inconsistently addressed. For instance, the social context—whether participants were alone or accompanied during green exercises—was rarely specified, despite its potential influence on outcomes [30]. Additionally, gender biases were evident, with four studies reporting predominantly female samples, while others exhibited uneven gender distributions. Lack of blinding and preregistration of hypotheses further contributed to bias.

Another critical gap was the omission of risks, complications, and safety considerations. None of the reviewed studies provided data on potential adverse effects, a shortcoming also noted by the Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template (CERT) [56]. Moreover, the lack of prospective protocol registration raises concerns about reporting bias, as outcomes may have been selectively analyzed or reported.

This review is the first to comprehensively analyze nature-based interventions (NBIs) specifically targeted at workplace settings, highlighting their potential to enhance workplace sustainability and promote sustainable practices. Its primary strength is the development of a transdisciplinary framework to identify key findings and clarify expected outcomes. Medline, known for its high recall efficacy in occupational health research, was used as a core database to ensure quality [57]. Bias was minimized by involving two researchers in screening and data extraction, supported by a third reviewer.

However, the review’s strength was limited by the scarcity and heterogeneity of available studies. NBIs were categorized into green exercise, nature savoring, and green office space, but these interventions differed significantly in delivery, duration, and intensity. The lack of comprehensive search strategies—exacerbated by deactivating database alerts after November 2018—might have excluded relevant studies. Collaborating with information specialists could have improved search sensitivity and specificity.

The Cochrane Risk of Bias (RoB 2) tool was used for quality assessment, but the authors encountered challenges with terminology inconsistencies and intervention complexity. Algorithmic errors in the Excel platform used for assessments further complicated the process.

NBIs, including green exercise and nature savoring, hold potential for diverse workplace settings. However, practical implementation requires employee participation during planning to foster engagement and ownership, crucial for effective recovery [50]. While NBIs are generally inclusive and cost-effective, they may not suit individuals with severe health conditions or environmental allergies.

The findings highlighted limitations in existing research, particularly methodological issues and bias in the studies. These limitations reduced the scope of the review, with only seven studies included. This emphasized the need for more vigorous research designs to provide stronger, more generalizable evidence on the impact of green spaces in workplaces.

This section offers practical recommendations for integrating nature-based interventions (NBIs) into workplace settings, particularly in high-stress sectors. In healthcare, green spaces within or near hospitals could provide restorative breaks, helping reduce stress and burnout. For sectors where outdoor access is limited, specific intervention strategies include promoting structured green breaks, indoor green solutions (like potted plants or green walls), and virtual nature alternatives in space-constrained workplaces. Implementation should include training for employees and managers; ensuring interventions align with workplace culture; and establishing metrics to evaluate effectiveness in terms of employee well-being, creativity, and stress reduction. These strategies aim to create environments that promote mental health, resilience, and creativity, while aligning with organizational goals.

Future research should address several key gaps. First, there is a need for more detailed descriptions of interventions, including thorough characterization of natural contexts and stimuli, to ensure replicability and facilitate robust comparisons. Additionally, strong study designs should be prioritized, incorporating cluster randomization, validated outcome measures, and standardized metrics to minimize bias and enhance reliability [58]. Long-term assessments are also essential, as they can provide valuable insights into medium- and long-term effects, including resilience and cost–benefit analyses [59,60]. Lastly, integrating contemporary theoretical frameworks, such as those proposed by Frumkin et al. [22] and Bratman et al. [61], can inform hypothesis generation and the design of interventions.

Moreover, examining personal (e.g., nature connectedness) and workplace (e.g., organizational culture) factors would clarify the conditions under which NBIs are most effective. Virtual nature experiences also merit exploration to broaden accessibility, particularly in urban or industrial settings [62].

Nature-based interventions (NBIs) offer substantial promise for improving workplace mental health, although further research is needed to refine their implementation. Future investigations should focus on identifying the most effective components, such as comparing the benefits of green spaces to blue spaces and physical nature to virtual experiences. Additionally, establishing evidence-based guidelines for the ideal frequency and duration of nature exposure is crucial for optimizing effectiveness. Evaluating the economic feasibility of integrating NBIs into workplace wellness programs is also essential to ensure their sustainability in practice. Another key area is developing strategies to tailor NBIs to align with organizational demands, while also addressing the diverse needs of employees. Despite these challenges, NBIs hold great potential to enhance recovery, resilience, and overall well-being among employees, offering meaningful benefits at individual, organizational, and societal levels.

5. Conclusions

The present paper highlighted the potential benefits of NBIs for promoting mental health in workplace settings, while also recognizing the limitations of the current evidence, including mixed findings on effectiveness and sustainability. Although most studies reported positive mental health outcomes, the sustainability of these benefits remains uncertain, and findings on cognitive ability, recovery, and work–life satisfaction were mixed. These uncertainties underlined the need for further research to establish long-term effects and clarify how different workplace contexts may influence outcomes, ultimately enabling more tailored and effective interventions. Methodological weaknesses, including small sample sizes and insufficient follow-up, undermined the reliability of conclusions.

The review also highlighted the positive effects of green spaces on workplace creativity while emphasizing the need for more rigorous methodologies and broader contextual applicability, particularly given the limitations posed by small sample sizes and inconsistent research designs in the current evidence. Addressing these gaps could strengthen the evidence base for scientific and practical advancements in workplace health and design. Strategies such as conducting large-scale longitudinal studies, implementing cluster randomized trials, and using standardized metrics for intervention outcomes could provide more powerful and generalizable findings. Additionally, fostering interdisciplinary collaborations could help integrate diverse perspectives and methodologies, further enhancing the quality of research in this field.

Strengthening the quality of NBI research through theoretical accuracy, detailed intervention protocols, and standardized outcome measures could enhance its applicability and contribute to developing evidence-based guidelines suitable for diverse workplace contexts. These guidelines could inform practical workplace strategies, such as designing nature-inclusive office spaces, implementing structured outdoor breaks, and integrating virtual nature experiences for employees in urban or resource-constrained settings.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su17020390/s1, PRISMA Checklist.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.Z., C.K. and V.C.; methodology, A.Z., C.K., V.C. and I.T. (Ioannis Tsartsapakis); writing—original draft preparation, V.C., C.K. and A.Z.; writing—review and editing, V.C., I.T. (Ioannis Trigonis) and I.T. (Ioannis Tsartsapakis); visualization, A.Z., C.K. and I.T. (Ioannis Trigonis); supervision, C.K. and A.Z.; project administration, C.K. and A.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Goetzel, R.Z.; Roemer, E.C.; Holingue, C.; Fallin, M.D.; McCleary, K.; Eaton, W.; Agnew, J.; Azocar, F.; Ballard, D.; Bartlett, J. Mental Health in the Workplace: A Call to Action Proceedings from the Mental Health in the Workplace—Public Health Summit. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018, 60, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Fabio, A. Positive Healthy Organizations: Promoting Well-Being, Meaningfulness, and Sustainability in Organizations. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capaldi, C.; Passmore, H.-A.; Nisbet, E.; Zelenski, J.; Dopko, R. Flourishing in Nature: A Review of the Benefits of Connecting with Nature and Its Application as a Wellbeing Intervention. Int. J. Wellbeing 2015, 5, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; Khreis, H.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Gascon, M.; Dadvand, P. Fifty Shades of Green. Epidemiology 2017, 28, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gritzka, S.; MacIntyre, T.E.; Dörfel, D.; Baker-Blanc, J.L.; Calogiuri, G. The Effects of Workplace Nature-Based Interventions on the Mental Health and Well-Being of Employees: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, M.P.; DeVille, N.V.; Elliott, E.G.; Schiff, J.E.; Wilt, G.E.; Hart, J.E.; James, P. Associations between Nature Exposure and Health: A Review of the Evidence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpela, K.; De Bloom, J.; Kinnunen, U. From Restorative Environments to Restoration in Work. Intell. Build. Int. 2015, 7, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Bosch, M.; Thompson, C.W.; Grahn, P. Preventing Stress and Promoting Mental Health. In Oxford Textbook of Nature and Public Health; van den Bosch, M., Bird, W., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 108–115. [Google Scholar]

- Berto, R. The Role of Nature in Coping with Psycho-Physiological Stress: A Literature Review on Restorativeness. Behav. Sci. 2014, 4, 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Luo, H.; Wei, Y.; Shin, W.-S. The Influence of Different Forest Landscapes on Physiological and Psychological Recovery. Forests 2024, 15, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calogiuri, G.; Litleskare, S.; Fagerheim, K.A.; Rydgren, T.L.; Brambilla, E.; Thurston, M. Experiencing Nature through Immersive Virtual Environments: Environmental Perceptions, Physical Engagement, and Affective Responses during a Simulated Nature Walk. Front. Psychol. 2018, 8, 10–3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, E.E.; McDonnell, A.S.; LoTemplio, S.B.; Uchino, B.N.; Strayer, D.L. Toward a Unified Model of Stress Recovery and Cognitive Restoration in Nature. Park. Steward. Forum 2021, 37, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job Demands–Resources Theory: Taking Stock and Looking Forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortés-Denia, D.; Lopez-Zafra, E.; Pulido-Martos, M. Physical and Psychological Health Relations to Engagement and Vigor at Work: A PRISMA-Compliant Systematic Review. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 765–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettmann, J.E.; Gillis, H.L.; Speelman, E.A.; Parry, K.J.; Case, J.M. A Meta-Analysis of Wilderness Therapy Outcomes for Private Pay Clients. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2016, 25, 2659–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullinix, K.J.; Leeper, T.J.; Druckman, J.N.; Freese, J. The Generalizability of Survey Experiments. J. Exp. Polit. Sci. 2015, 2, 109–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pálsdóttir, A.M.; Sempik, J.; Bird, W.; van den Bosch, M. Using Nature as a Treatment Option. In Oxford Textbook of Nature and Public Health; van den Bosch, M., Bird, W., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 125–131. [Google Scholar]

- Annerstedt, M.; Währborg, P. Nature-Assisted Therapy: Systematic Review of Controlled and Observational Studies. Scand. J. Public Health 2011, 39, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragg, R.; Atkins, G. A Review of Nature-Based Interventions for Mental Health Care. Nat. Engl. Comm. Rep. 2016, 204, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson Coon, J.; Boddy, K.; Stein, K.; Whear, R.; Barton, J.; Depledge, M.H. Does Participating in Physical Activity in Outdoor Natural Environments Have a Greater Effect on Physical and Mental Wellbeing than Physical Activity Indoors? A Systematic Review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 1761–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahart, I.; Darcy, P.; Gidlow, C.; Calogiuri, G. The Effects of Green Exercise on Physical and Mental Wellbeing: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frumkin, H.; Bratman, G.N.; Breslow, S.J.; Cochran, B.; Kahn Jr, P.H.; Lawler, J.J.; Levin, P.S.; Tandon, P.S.; Varanasi, U.; Wolf, K.L.; et al. Nature Contact and Human Health: A Research Agenda. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125, 75001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar]

- Grellier, J.; White, M.P.; Albin, M.; Bell, S.; Elliott, L.R.; Gascón, M.; Gualdi, S.; Mancini, L.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; Sarigiannis, D.A.; et al. BlueHealth: A Study Programme Protocol for Mapping and Quantifying the Potential Benefits to Public Health and Well-Being from Europe’s Blue Spaces. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e016188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Bosch, M.; Sang, Å.O. Urban Natural Environments as Nature-Based Solutions for Improved Public Health–A Systematic Review of Reviews. Environ. Res. 2017, 158, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Bosch, M.; Bird, W. Oxford Textbook of Nature and Public Health: The Role of Nature in Improving the Health of a Population; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; ISBN 019103875X. [Google Scholar]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A Web and Mobile App for Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igelström, E.; Campbell, M.; Craig, P.; Katikireddi, S.V. Cochrane’s Risk of Bias Tool for Non-Randomized Studies (ROBINS-I) Is Frequently Misapplied: A Methodological Systematic Review. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 140, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murad, M.H.; Mustafa, R.A.; Schünemann, H.J.; Sultan, S.; Santesso, N. Rating the Certainty in Evidence in the Absence of a Single Estimate of Effect. Evid. Based Med. 2017, 22, 85–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bloom, J.; Sianoja, M.; Korpela, K.; Tuomisto, M.; Lilja, A.; Geurts, S.; Kinnunen, U. Effects of Park Walks and Relaxation Exercises during Lunch Breaks on Recovery from Job Stress: Two Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 51, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sianoja, M.; Syrek, C.J.; de Bloom, J.; Korpela, K.; Kinnunen, U. Enhancing Daily Well-Being at Work through Lunchtime Park Walks and Relaxation Exercises: Recovery Experiences as Mediators. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrente, P.; Kinnunen, U.; Sianoja, M.; de Bloom, J.; Korpela, K.; Tuomisto, M.T.; Lindfors, P. The Effects of Relaxation Exercises and Park Walks During Workplace Lunch Breaks on Physiological Recovery. Scand. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2017, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brossoit, R.M.; Crain, T.L.; Leslie, J.J.; Fisher, G.G.; Eakman, A.M. Engaging with Nature and Work: Associations among the Built and Natural Environment, Experiences Outside, and Job Engagement and Creativity. Front. Psychol. 2024, 14, 1268962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Chen, D.; Bian, Z.; Shen, T.; Zhang, W.; Cai, W. How Does Green Training Boost Employee Green Creativity? A Sequential Mediation Process Model. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 759548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanahan, D.F.; Bush, R.; Gaston, K.J.; Lin, B.B.; Dean, J.; Barber, E.; Fuller, R.A. Health Benefits from Nature Experiences Depend on Dose. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Largo-Wight, E.; Wlyudka, P.S.; Merten, J.W.; Cuvelier, E.A. Effectiveness and Feasibility of a 10-Minute Employee Stress Intervention: Outdoor Booster Break. J. Workplace Behav. Health 2017, 32, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, J. Wellbeing Work-Out: Utilisation and Comparison of Green Exercise and Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction as Workplace Interventions for Staff at the University of Essex. Master’s Thesis, University of Essex, Colchester, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Passmore, H.-A.; Holder, M.D. Noticing Nature: Individual and Social Benefits of a Two-Week Intervention. J. Posit. Psychol. 2017, 12, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.L.; Bryant, F.B. The Benefits of Savoring Life. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2016, 84, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.J.F.; Littzen, C.O.R. An Analysis of Theoretical Perspectives in Research on Nature-Based Interventions and Pain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.; Matos, M.; Gonçalves, M. Nature and Human Well-Being: A Systematic Review of Empirical Evidence from Nature-Based Interventions. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2024, 67, 3397–3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkie, S.; Davinson, N. Prevalence and Effectiveness of Nature-Based Interventions to Impact Adult Health-Related Behaviours and Outcomes: A Scoping Review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 214, 104166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, M.H.E.M.; Rigolon, A. School Green Space and Its Impact on Academic Performance: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S. Job-Stress Recovery: Core Findings, Future Research Topics, and Remaining Challenges; Work Science Center Thinking Forward Report Series; Georgia Institute of Technology: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lygum, V.L.; Dupret, K.; Bentsen, P.; Djernis, D.; Grangaard, S.; Ladegaard, Y.; Troije, C.P. Greenspace as Workplace: Benefits, Challenges and Essentialities in the Physical Environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levstek, M.; Papworth, S.; Woods, A.; Archer, L.; Arshad, I.; Dodds, K.; Holdstock, J.S.; Bennett, J.; Dalton, P. Immersive Storytelling for Pro-Environmental Behaviour Change: The Green Planet Augmented Reality Experience. Comput. Human Behav. 2024, 161, 108379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soga, M.; Gaston, K.J.; Yamaura, Y. Gardening Is Beneficial for Health: A Meta-Analysis. Prev. Med. Rep. 2017, 5, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Fagerholm, N.; Skov-Petersen, H.; Beery, T.; Wagner, A.M.; Olafsson, A.S. Shortcuts in Urban Green Spaces: An Analysis of Incidental Nature Experiences Associated with Active Mobility Trips. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 82, 127873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, S.; Clemente, D.B.P.; Desart, S.; Saenen, N.; Sleurs, H.; Nawrot, T.S.; Malina, R.; Plusquin, M. Introducing Nature at the Work Floor: A Nature-Based Intervention to Reduce Stress and Improve Cognitive Performance. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2022, 240, 113884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonnentag, S. The Recovery Paradox: Portraying the Complex Interplay between Job Stressors, Lack of Recovery, and Poor Well-Being. Res. Organ. Behav. 2018, 38, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Mitchell, R.; de Vries, S.; Frumkin, H. Nature and Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson-Koku, G. Beck Depression Inventory. Occup. Med. 2016, 66, 174–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charan, J.; Kaur, R.; Bhardwaj, P.; Singh, K.; Ambwani, S.R.; Misra, S. Sample Size Calculation in Medical Research: A Primer. Ann. Natl. Acad. Med. Sci. 2021, 57, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kals, E.; Nisbet, E.K. Affective Connection to Nature. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard, A.; Richardson, M.; Sheffield, D.; McEwan, K. The Relationship Between Nature Connectedness and Eudaimonic Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis. J. Happiness Stud. 2020, 21, 1145–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, S.C.; Dionne, C.E.; Underwood, M.; Buchbinder, R. Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template (CERT): Explanation and Elaboration Statement. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 1428–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.M.; Jones, R.; Tocchini, K. Shinrin-Yoku (Forest Bathing) and Nature Therapy: A State-of-the-Art Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, R.J.; Moulton, L.H. Cluster Randomised Trials; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; ISBN 131537028X. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, C.; O’Shea, D.; MacIntyre, T.E. The What, How, Where and When of Resilience as a Dynamic, Episodic, Self-Regulating System: A Response to Hill et al. (2018). Sport. Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 2018, 7, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, S.; Koehn, C.; White, M.; Harder, H.; Schultz, I.; Williams-Whitt, K.; Wärje, O.; Dionne, C.; Koehoorn, M.; Pasca, R.; et al. Mental Health Interventions in the Workplace and Work Outcomes: A Best-Evidence Synthesis of SystematicReviews. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2016, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bratman, G.N.; Anderson, C.B.; Berman, M.G.; Cochran, B.; de Vries, S.; Flanders, J.; Folke, C.; Frumkin, H.; Gross, J.J.; Hartig, T.; et al. Nature and Mental Health: An Ecosystem Service Perspective. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaax0903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calogiuri, G.; Litleskare, S.; MacIntyre, T.E. Future-Thinking through Technological Nature. In Physical Activity in Natural Settings; Routledge: Abingdon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 279–298. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).